Abstract

Vaccination against influenza averts cardiovascular events and is recommended for all patients with coronary heart disease. Because data were unavailable regarding vaccination rates among such patients' household contacts, we sought to estimate the rate of influenza vaccination in persons with cardiovascular disease and their contacts.

In 2004, we conducted a random, nationwide telephone survey of 1,202 adults (age, ≥18 yr) to ascertain knowledge, attitudes, and behaviors regarding influenza vaccination. Of the interviewees, 134 (11.1%) had histories of heart disease or stroke. Of these 134, 57% were men, and 45% were ≥65 years of age. Overall, 57% were inoculated against influenza in 2003–2004, and 68% intended the same during 2004–2005. Vaccination rates increased with age: 48% (ages, 18–49 yr), 68% (ages, 50–64 yr), and 75% (age, ≥65 yr). Forty of 69 respondents (58%) reported that their spouses were vaccinated, and 7 of 21 (33%) reported the inoculation of children ≤17 years old in their household. Only 65% of the 134 patients considered themselves to be of high-risk status. Chief reasons for remaining unvaccinated were disbelief in being at risk and fear of contracting influenza from the vaccine.

Although seasonal influenza vaccination is recommended for all coronary heart disease patients and their household contacts, the practice is less prevalent than is optimal. Intensified approaches are needed to increase vaccination rates. These findings suggest a need to increase vaccination efforts in high-risk subjects, particularly amidst the emerging H1N1 pandemic.

Key words: Advisory committees/statistics & numerical data/trends; age factors; cardiovascular diseases/etiology/prevention & control/virology; cost of illness; health care surveys; health policy; infectious disease transmission; influenza vaccines/administration & dosage/economics/supply & distribution/therapeutic use; influenza, human/complications/epidemiology/immunology/mortality/prevention & control/transmission; risk factors; United States/epidemiology; vaccination/economics/standards/statistics & numerical data/utilization

Coronary heart disease (CHD) is the leading cause of death in the Western world. It claims more than 700,000 American lives each year and accounts for 29% of all deaths in the United States, costing the nation $193.8 billion per year.1 Influenza, the 7th leading cause of death, was responsible for 64,684 deaths in 1999 and an average of 36,000 deaths per year in the United States during the 1990s.2 Annual estimates of influenza-associated deaths have increased substantially over the last 2 decades. Influenza is associated with preventable hospitalizations (especially in the elderly population) and with increased healthcare costs that amount to millions of dollars.3 Outbreaks of variable extent and severity, which occur nearly every winter, result in substantial morbidity in the general population and in increased mortality rates among certain high-risk patients, chiefly from cardiovascular and pulmonary complications.4 As we have shown earlier, a considerable number of coronary events are triggered by influenza infection.5–7 Moreover, physicians tend to underreport influenza cases, especially when the illness is complicated by myocardial infarction (MI). Therefore, the true incidence in the United States may exceed 36,000 deaths per year.7

Vaccination—currently the most effective action against influenza—reduces the occurrence of the illness by 70% to 90% in healthy adults younger than 65 years of age8,9 and reduces the all-cause mortality rate by 50% to 68% in healthy persons of age 65 and older.10,11 Vaccination is also efficacious in reducing healthcare costs and the losses in productivity that are associated with influenza illness.12

Inoculation against influenza has been shown to prevent the occurrence of cardiovascular events in high-risk patients.7 We have previously shown that, in patients with chronic CHD, vaccination reduces the risk of developing recurrent MI during the peak influenza season13 of September through February. Other researchers have confirmed our findings by showing a post-vaccination decrease in hospitalization for primary cardiac arrest14,15; death and ischemic events after MI and angioplasty16; the composite endpoint of cardiovascular death, MI, or unplanned revascularization or hospitalization for ischemia17; and stroke and transient ischemic attacks.18,19 One study determined no benefit.20

The inoculation of all persons who have chronic cardiovascular conditions, and of anyone in close contact with these persons, is recommended by the Centers for Disease Control (CDC).21 Close contacts include household members (spouses and children) and in-home healthcare workers. Despite the recommendations, it was found that only 38.8% of persons with CHD in the 18-to 49-year age group and 83.1% in the 50-to 64-year age group with CHD had received the influenza vaccine in 2001.22 Another study reported similar findings.23 Moreover, a lack of data concerning the vaccination rates in household contacts of CHD patients potentially forebodes greater challenges in attaining the CDC-recommended goals regarding vaccination against influenza. Children are the primary source for transmitting influenza infection to adults: previous studies have shown that inoculating children reduces all-cause death in the elderly and influenza-related illnesses in all adults.24,25

In light of these factors, we commissioned a nationwide telephone survey in order to investigate the rate of influenza vaccination among CHD patients and their household contacts. Our aim was to identify patients with cardiovascular disease (CVD) and evaluate why large numbers of them fail to avail themselves of vaccination against influenza.

Subjects and Methods

The survey was conducted in collaboration with Zogby International (http://www.zogby.com), a private polling and marketing-research organization. In mid-December 2004, we conducted a random, nationwide telephone interview survey of 1,202 U.S. households, in order to ascertain people's knowledge, attitudes, and behaviors regarding vaccination against influenza. A randomly selected adult in each sampled household was asked to answer our survey questionnaire. The interview was conducted by Zogby International's general interviewers, who were constantly monitored by their supervisors in order to evaluate their adherence to surveying standards. Zogby International strives to attain a 12:1 ratio of interviewers to supervisors. In order to monitor the interviewers' performance, quality-control checks were conducted on 10% of all the telephone calls.

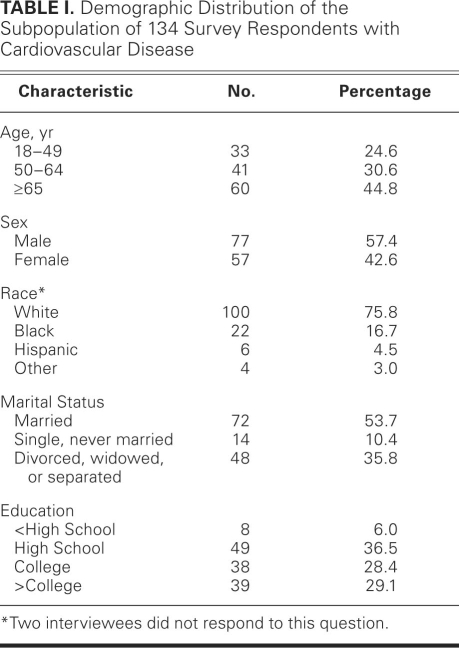

We chose to consider only the answers of the 134 patients who reported a history of CHD or stroke (CVD) (Table I). Table II shows the survey questions and responses. The presence of CVD was defined as an affirmative answer to the question, “Has a doctor ever told you that you have had a stroke, or have coronary heart disease (also called heart attack, angina, atherosclerosis, hardening of the arteries, or blockages)?”

TABLE I. Demographic Distribution of the Subpopulation of 134 Survey Respondents with Cardiovascular Disease

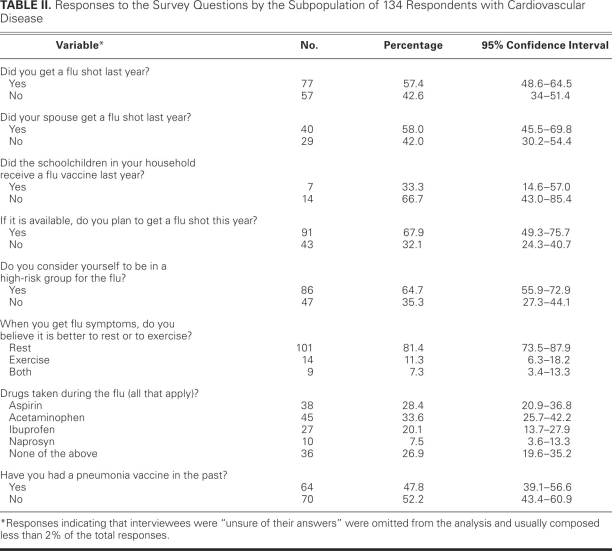

TABLE II. Responses to the Survey Questions by the Subpopulation of 134 Respondents with Cardiovascular Disease

Statistical Analysis

Sample weights were added to the data to produce frequencies whereby demographic variables (age, sex, race, religion, and region) were adjusted to their proportions in the populations that were sampled. The overall margin of error was ±2.9%. Using these survey data, the prevalence of CVD (CHD or stroke) among the sampled population was calculated. Responses indicating that interviewees were “unsure of their answers” were omitted from the analysis and usually composed less than 2% of the total responses. The 2% was chosen so that the omitted data did not affect the rest of the analysis.

We used SPSS 11.0 (SPSS Inc.; Chicago, Ill) and Stata® 9.0 (StataCorp LP; College Station, Tex) statistical packages to perform the statistical analyses. We applied c2 statistics to categorical variables. A P value of less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant. The data conformed to each test that was used to analyze them.

Results

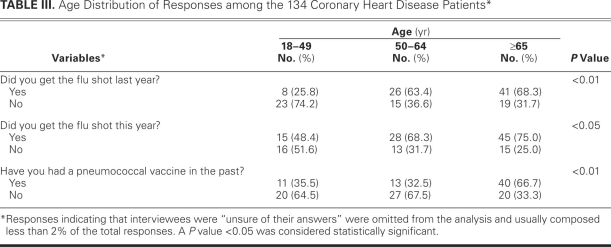

Of the 1,202 subjects who completed the survey (48% men, 52% women), 134 reported having CVD (11.1%). Of those 134, 45% were age 65 years or older and 57% were men (Table I). Fifty-eight percent had been administered the influenza vaccine during the prior influenza season (2003–2004), and 68% had been or intended to be inoculated during the 2004–2005 season (the survey time). Half had been administered pneumococcal vaccine in the past. Receipt of either vaccine increased with age (Table III).

TABLE III. Age Distribution of Responses among the 134 Coronary Heart Disease Patients*

During the then-ongoing influenza season of 2004–2005, 58% (40 of 69 respondents) reported the vaccination of their spouse, and 33% (7 of 21) reported that children ≤17 years of age in their household had been inoculated.

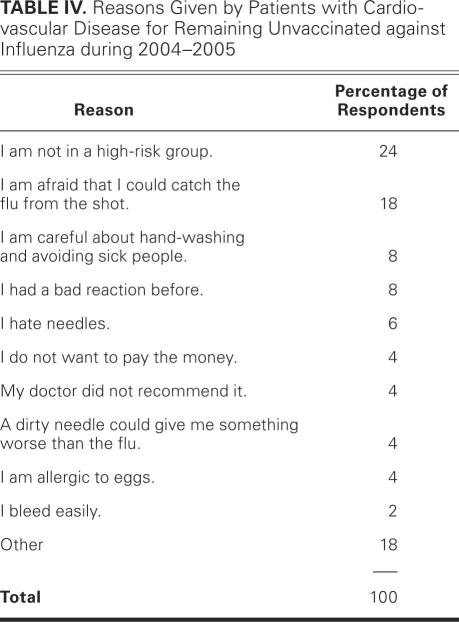

When CVD patients were asked whether they considered themselves to be in a high-risk group and therefore at greater need of vaccination against influenza, 65% answered yes and 35% answered no (Table II). The belief of not being at high risk was a major reason for not undergoing inoculation (Table IV).

TABLE IV. Reasons Given by Patients with Cardiovascular Disease for Remaining Unvaccinated against Influenza during 2004–2005

When CVD patients were asked what they would do if they were to contract influenza, approximately 81% believed in resting, whereas 11% believed in exercising (Table II). Regarding drugs that are used to treat influenza-like symptoms, a plurality of patients mentioned the use of acetaminophen (34%); others named aspirin (28%) or ibuprofen (20%). Most who had not received the pneumococcal vaccine (92%) did not intend to avail themselves of it in 2004–2005. When interviewees were asked if they believed that “influenza can trigger heart attacks, stroke, or sudden death,” 44% responded affirmatively.

Table IV shows the reasons why CVD participants planned to remain unvaccinated against influenza. Most common among these involved ignorance or repudiation of their high-risk status and fearfulness of contracting influenza from the vaccine.

Discussion

From this nationwide survey of U.S. adults, we found rates of inoculation against influenza in patients with CVD to be much lower than has been recommended by several medical societies. The coverage rate was even lower among the respondents' household contacts. Many CVD patients were unaware or dismissive of their high-risk status and of the consequent advisability of immunization. A considerable number of the survey respondents, especially the young, exercised when experiencing flu-like symptoms. Fewer than one third of the respondents took aspirin when they had such symptoms.

Vaccination Rates in Cardiovascular Patients

For all persons with any chronic heart disease, vaccination against influenza is advocated by the CDC, the American Heart Association (AHA), and the American College of Cardiology (ACC).26,27 However, many patients in our survey were unaware of this recommendation, and some healthcare providers have neglected its active pursuit. The influenza vaccine is safely administered and is cost-effective as a protective approach, and its administration has been associated with a reduced risk of various cardiovascular events.7 However, this preventive path is not widely exploited by CVD patients. Singleton and colleagues22 studied the data from the 1997-through-2001 National Health Interview Surveys (NHIS) and reported that the proportion of persons with heart disease who reported having been vaccinated against influenza remained relatively stable from the 1996–1997 through 2000–2001 influenza seasons. During the 1999–2000 season, 49.2% of CVD patients 50 to 64 years of age and only 22.7% of CVD patients 18 to 49 years of age were inoculated.22 Another study,23 which subsequently used the NHIS database, reported a comparably low rate of vaccination in CVD patients during the 2002–2003 season: 22% of persons with CVD who were younger than age 50 had received the influenza vaccine, and the coverage of vaccine in all CVD patients was 32.7% after adjustment for age. The vaccination rate was 37% in patients with congestive heart failure, 31.4% in stroke patients, 40.5% in CVD patients who were 50 to 64 years of age, and 69.9% in CVD patients of age 65 or older.23 In our study, the vaccination rate in CVD patients similarly increased with their age.

Effect of Vaccine Shortages on Vaccination Rates

According to the NHIS, in the 2003–2004 influenza season, the vaccination rate was 65.6% for adults ≥65 years of age (66% in men and 65.2% in women) and 34.1% for adults 18 to 64 years of age who had a high-risk condition.28 In 2003–2004, among persons 50 to 64 years of age, vaccination coverage was 46.3% for persons with high-risk conditions and 32.7% for persons without, in comparison with 49.2% among individuals 50 to 64 years of age and 22.7% among those 18 to 49 years of age during the 1999–2000 influenza season.22 Although the vaccination rates for adults ≥65 years of age surpassed the Healthy People 2000 goal of 60% coverage,29–31 the Healthy People 2010 goal of 90% coverage seems unattainable without further action.29,30 Although numerous approaches have been implemented in order to increase the rate of vaccination, they have not yielded the targeted results. Additional complications have included delays in distribution and shortages of vaccine supplies, especially during the 2000–2001 and 2004–2005 influenza seasons. The shortage during the 2004–2005 season impelled the CDC to ration vaccine and to republish the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices' influenza-vaccine recommendations, with emphasis on first providing vaccines to persons ≥65 years of age, adults and children who have chronic disorders of the pulmonary or cardiovascular systems, and other high-risk individuals.30

We found that the 2004–2005 influenza season's vaccine shortage and the consequent media publicity helped to educate CVD patients of their high-risk status and increased their motivation to be inoculated. (It has not been specifically determined whether the increase was due chiefly to the patients' motivation, to physicians' increased aggressiveness in recommending vaccination, or to a combination of those factors.) An opportunity arose to inform the public about the importance of basic hygiene in influenza control (for example, frequent hand-washing). Although the U.S. vaccine supply was 50% of the usual, we found that the proportion of CVD patients who received the vaccine was comparable with that of previous years. Focusing the administration of the scarce vaccine toward persons at high risk helped to maintain that group's level of immunization: the CDC Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System reported that 62.7% of Americans ≥65 years of age underwent inoculation from September 2004 through January 2005. This coverage was comparable with the rate for the same age group in previous years, but it was at the expense of a lower rate in younger persons (34.2% of adults of age 18–64 yr with high-risk conditions, and 8.8% of healthy individuals in that age range).

Awareness of High Risk

Among all 134 survey respondents who had CVD and who did not receive the vaccine in 2004–2005, the chief reasons were “I am not in a high-risk group” (24%), “I am afraid that I could catch the flu from the shot” (18%), “I am careful about hand-washing and avoiding sick people” (8%), and “I had a bad reaction before” (8%). Adding these answers to data from other surveys and articles, we conclude that the biggest impediments to increasing vaccine coverage are patients' ignorance or repudiation of their high-risk status and their lack of knowledge regarding the cardioprotective effects of the vaccine. The impediments arise from suboptimal awareness by patients of the advisability of vaccination and from the ongoing need to remind doctors and nurses of the importance of vaccinating CVD patients. Clinicians could further educate their patients about that importance.

Practice Guidelines

Inoculation against influenza is officially advocated by the CDC for all patients with any cardiac disease,21 and these patients are among those who are targeted to receive the influenza vaccine as a priority, even in times of influenza-vaccine shortage.30 The American Diabetes Association also officially endorses influenza vaccination in diabetic patients and has included influenza vaccine in its clinical-practice guidelines.31 On the basis of studies by our group and others, influenza vaccination was added to the AHA/ACC secondary-prevention guidelines in 2006.26,27

Adults Who Take Aspirin after Contracting Influenza

Influenza infection is associated with the release of procoagulant factors and an increased risk of thrombosis.32 Therefore, adults who have contracted influenza are prudent to take aspirin instead of other nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, which lack antiplatelet effects. The risk of Reye's disease in children who take aspirin during influenza infection has led to decreased use of aspirin in all persons who contract influenza. However, given the low risk of Reye's disease in adults, the taking of aspirin is recommended, especially by those who may experience cardiovascular events.

Exercising When Ill with Influenza

Although regular, moderate exercise can protect individuals from coronary events over the long term, strenuous physical activity can trigger heart attacks, particularly among persons who exercise infrequently.33 This risk is magnified when a CHD patient contracts influenza, which is an illness that can trigger MI on its own. Over 11% of our 134 survey respondents claimed that they exercised while they were ill with influenza, in order to “sweat out the flu.” Persons who have or are at risk of CHD should be discouraged from this behavior in favor of resting while ill with influenza.

How Vaccinating Children Affects Adult Health

Influenza infection rates in children are generally the highest of any age group, averaging 25% to 43%,34 and children are a distinct conduit for the transmission of influenza, especially within households.35,36 Correlation has been found between vaccinating children and reducing all-cause death in susceptible individuals. Regarding secondary cases of influenza that are caused by exposure to a sick child in the household, Viboud and associates35 estimated that vaccinating children against influenza would prevent 32% to 38%, and that prophylaxis with neuraminidase inhibitors would prevent 21% to 41%. Weycker and colleagues37 estimated that vaccinating 20% of children would reduce the total number of influenza cases in the U.S. by 46%, and that 80% coverage would result in a 91% reduction.

Reichert and co-authors25 reported that inoculating Japanese schoolchildren against influenza led to a significant decrease in the rates of all-cause death and pneumonia–influenza death in the elderly. Vaccination of about 80% of schoolchildren in a community has been reported to decrease respiratory illnesses in adults.25,38 In an open-label, nonrandomized, community-based trial, Piedra and colleagues24 reported in 2005 that vaccinating 20% to 25% of children (age, 1.5–18 yr) with trivalent cold-adapted influenza vaccine (CAIV-T) resulted in an indirect protection of 8% to 18% against medically attended acute respiratory illness in adults ≥35 years of age. Accordingly, vaccinating the young household contacts of CVD patients can reduce the occurrence of cardiovascular events through a herd-immunity mechanism.

Limitations of the Study

Our study is subject to all limitations that apply to survey studies that are conducted by telephone. Our data are based upon self-reported avail of vaccines and on self-reported histories of CVD—both of which factors are known to be subject to a certain level of bias in survey studies. It was not possible for us to collect data on the characteristics of nonrespondents. Therefore, it is unknown whether the nonrespondents experienced a higher or lower influenza vaccination rate and whether they exhibited different health-related behavior.

Recommendations

Research is needed in order to identify additional efforts by which to increase influenza-vaccination rates among patients who have CVD. Cardiologists and cardiac patients alike should be targeted in coordinated educational programs. We are optimistic that the decisions of the AHA and ACC to recommend influenza vaccination in their secondary-prevention guidelines will lead to higher vaccination coverage among U.S. cardiovascular patients and that other cardiology societies will advocate influenza vaccination in their practice guidelines. The impact of the updated AHA/ACC guidelines can be evaluated in future surveys. Other potential approaches to increasing compliance include possibly requiring a high overall level of vaccination of patients for hospital accreditation or for physician licensure. Other cardiology societies could emulate the AHA and ACC and issue specific recommendations in light of the evident and specific cardioprotective effects of influenza vaccine. The impact of the 2009–2010 H1N1 “swine flu” pandemic on cardiovascular events should be taken into account during the formulation of pandemic-preparation plans.

Previously, we and others have shown that vaccination against influenza can reduce the risk of cardiovascular events. The present study reveals several factors that are involved in the underexploitation of influenza vaccination in a high-risk group. In light of realistic speculation that past patterns of suboptimal inoculation have continued beyond the date of our survey, we believe that educational programs should confront the known obstacles so that optimal vaccination rates in CVD patients can be attained.

Footnotes

Address for reprints: Mohammad Madjid, MD, MSc, Texas Heart Institute at St. Luke's Episcopal Hospital, 6770 Bertner Ave., MC 2–255, Houston, TX 77030

E-mail: mmadjid@gmail.com

An abstract of this research was presented in September 2006 at the World Congress of Cardiology in Barcelona, Spain.

Source of support: This study was supported in part by U.S. Department of Defense grant #W81XWH-04-2-0035.

References

- 1.Lloyd-Jones D, Adams R, Carnethon M, De Simone G, Ferguson TB, Flegal K, et al. Heart disease and stroke statistics–2009 update: a report from the American Heart Association Statistics Committee and Stroke Statistics Subcommittee [published erratum appears in Circulation 2009;119(3):e182]. Circulation 2009;119(3):e21–181. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 2.Thompson WW, Shay DK, Weintraub E, Brammer L, Cox N, Anderson LJ, Fukuda K. Mortality associated with influenza and respiratory syncytial virus in the United States. JAMA 2003;289(2):179–86. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 3.Barker WH. Excess pneumonia and influenza associated hospitalization during influenza epidemics in the United States, 1970–78. Am J Public Health 1986;76(7):761–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 4.Dolin R. Influenza. In: Braunwald E, Fauci AS, Kasper DL, Hauser SL, Longo DL, Jameson JL, editors. Harrisons' principles of internal medicine. 15th ed. New York: McGraw-Hill; 2001. p. 1125–30.

- 5.Madjid M, Miller CC, Zarubaev VV, Marinich IG, Kiselev OI, Lobzin YV, et al. Influenza epidemics and acute respiratory disease activity are associated with a surge in autopsy-confirmed coronary heart disease death: results from 8 years of autopsies in 34,892 subjects. Eur Heart J 2007;28(10):1205–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 6.Madjid M, Casscells SW. Of birds and men: cardiologists' role in influenza pandemics. Lancet 2004;364(9442):1309. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 7.Madjid M, Naghavi M, Litovsky S, Casscells SW. Influenza and cardiovascular disease: a new opportunity for prevention and the need for further studies. Circulation 2003;108(22): 2730–6. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 8.Bridges CB, Thompson WW, Meltzer MI, Reeve GR, Talamonti WJ, Cox NJ, et al. Effectiveness and cost-benefit of influenza vaccination of healthy working adults: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA 2000;284(13):1655–63. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 9.Wilde JA, McMillan JA, Serwint J, Butta J, O'Riordan MA, Steinhoff MC. Effectiveness of influenza vaccine in health care professionals: a randomized trial. JAMA 1999;281(10):908–13. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 10.Nichol KL, Wuorenma J, von Sternberg T. Benefits of influenza vaccination for low-, intermediate-, and high-risk senior citizens. Arch Intern Med 1998;158(16):1769–76. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 11.Gross PA, Hermogenes AW, Sacks HS, Lau J, Levandowski RA. The efficacy of influenza vaccine in elderly persons. A meta-analysis and review of the literature. Ann Intern Med 1995;123(7):518–27. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 12.Nichol KL, Margolis KL, Wuorenma J, Von Sternberg T. The efficacy and cost effectiveness of vaccination against influenza among elderly persons living in the community. N Engl J Med 1994;331(12):778–84. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 13.Naghavi M, Barlas Z, Siadaty S, Naguib S, Madjid M, Casscells W. Association of influenza vaccination and reduced risk of recurrent myocardial infarction. Circulation 2000;102(25): 3039–45. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 14.Siscovick DS, Raghunathan TE, Lin D, Weinmann S, Arbogast P, Lemaitre RN, et al. Influenza vaccination and the risk of primary cardiac arrest. Am J Epidemiol 2000;152(7):674–7. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 15.Nichol KL, Nordin J, Mullooly J, Lask R, Fillbrandt K, Iwane M. Influenza vaccination and reduction in hospitalizations for cardiac disease and stroke among the elderly. N Engl J Med 2003;348(14):1322–32. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 16.Gurfinkel EP, de la Fuente RL, Mendiz O, Mautner B. Influenza vaccine pilot study in acute coronary syndromes and planned percutaneous coronary interventions: the FLU Vaccination Acute Coronary Syndromes (FLUVACS) Study. Circulation 2002;105(18):2143–7. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 17.Ciszewski A, Bilinska ZT, Brydak LB, Kepka C, Kruk M, Romanowska M, et al. Influenza vaccination in secondary prevention from coronary ischaemic events in coronary artery disease: FLUCAD study. Eur Heart J 2008;29(11):1350–8. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 18.Lavallee P, Perchaud V, Gautier-Bertrand M, Grabli D, Amarenco P. Association between influenza vaccination and reduced risk of brain infarction [published erratum appears in Stroke 2002;33(4):1171]. Stroke 2002;33(2):513–8. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 19.Grau AJ, Fischer B, Barth C, Ling P, Lichy C, Buggle F. Influenza vaccination is associated with a reduced risk of stroke. Stroke 2005;36(7):1501–6. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 20.Jackson LA, Yu O, Heckbert SR, Psaty BM, Malais D, Barlow WE, Thompson WW. Influenza vaccination is not associated with a reduction in the risk of recurrent coronary events. Am J Epidemiol 2002;156(7):634–40. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 21.Harper SA, Fukuda K, Uyeki TM, Cox NJ, Bridges CB; Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP). Prevention and control of influenza: recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP) [published erratum appears in MMWR Recomm Rep 2004;53(32):743]. MMWR Recomm Rep 2004;53(RR-6):1–40. [PubMed]

- 22.Singleton JA, Wortley P, Lu PJ. Influenza vaccination of persons with cardiovascular disease in the United States. Tex Heart Inst J 2004;31(1):22–7. [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 23.Ajani UA, Ford ES, Mokdad AH. Examining the coverage of influenza vaccination among people with cardiovascular disease in the United States. Am Heart J 2005;149(2):254–9. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 24.Piedra PA, Gaglani MJ, Kozinetz CA, Herschler G, Riggs M, Griffith M, et al. Herd immunity in adults against influenza-related illnesses with use of the trivalent-live attenuated influenza vaccine (CAIV-T) in children. Vaccine 2005;23(13): 1540–8. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 25.Reichert TA, Sugaya N, Fedson DS, Glezen WP, Simonsen L, Tashiro M. The Japanese experience with vaccinating schoolchildren against influenza. N Engl J Med 2001;344(12):889–96. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 26.Smith SC Jr, Allen J, Blair SN, Bonow RO, Brass LM, Fonarow GC, et al. AHA/ACC guidelines for secondary prevention for patients with coronary and other atherosclerotic vascular disease: 2006 update: endorsed by the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute [published erratum appears in Circulation 2006;113(22):e847]. Circulation 2006;113(19):2363–72. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 27.Davis MM, Taubert K, Benin AL, Brown DW, Mensah GA, Baddour LM, et al. Influenza vaccination as secondary prevention for cardiovascular disease: a science advisory from the American Heart Association/American College of Cardiology [published erratum appears in Circulation 2006;114(22): e616]. Circulation 2006;114(14):1549–53. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 28.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Influenza vaccination levels among persons aged > or =65 years and among persons aged 18–64 years with high-risk conditions–United States, 2003. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2005; 54(41):1045–9. [PubMed]

- 29.U.S. Department of Health & Human Services. Healthy People 2010: understanding and improving health. 2nd ed. Washington, DC: U.S. Government Printing Office; 2000 November.

- 30.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Update: influenza vaccine supply and recommendations for prioritization during the 2005–06 influenza season. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2005;54(34):850. [PubMed]

- 31.Smith SA, Poland GA. Influenza and pneumococcal immunization in diabetes. Diabetes Care 2004;27 Suppl 1:S111-3. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 32.Madjid M, Aboshady I, Awan I, Litovsky S, Casscells SW. Influenza and cardiovascular disease: is there a causal relationship? Tex Heart Inst J 2004;31(1):4–13. [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 33.Willich SN, Lewis M, Lowel H, Arntz HR, Schubert F, Schroder R. Physical exertion as a trigger of acute myocardial infarction. Triggers and Mechanisms of Myocardial Infarction Study Group. N Engl J Med 1993;329(23):1684–90. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 34.Glezen WP. Emerging infections: pandemic influenza. Epidemiol Rev 1996;18(1):64–76. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 35.Viboud C, Boelle PY, Cauchemez S, Lavenu A, Valleron AJ, Flahault A, Carrat F. Risk factors of influenza transmission in households. Br J Gen Pract 2004;54(506):684–9. [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 36.Badger GF, Dingle JH, Feller AE, Hodges RG, Jordan WS Jr, Rammelkamp CH Jr. A study of illness in a group of Cleveland families. V. Introductions and secondary attack rates as indices of exposure to common respiratory diseases in the community. Am J Hyg 1953;58(2):179–82. [PubMed]

- 37.Weycker D, Edelsberg J, Halloran ME, Longini IM Jr, Nizam A, Ciuryla V, Oster G. Population-wide benefits of routine vaccination of children against influenza. Vaccine 2005;23 (10):1284–93. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 38.Monto AS, Davenport FM, Napier JA, Francis T Jr. Modification of an outbreak of influenza in Tecumseh, Michigan by vaccination of schoolchildren. J Infect Dis 1970;122(1):16–25. [DOI] [PubMed]