Abstract

Despite the potential importance of the human regulator of calcineurin 1 (RCAN-1) gene in the modulation of cell survival under stress, little is known about its role in death-inducing signal pathways. In this study, we addressed the effects of RCAN1.4 knockdown on cellular susceptibility to apoptosis and the activation of death pathway proteins. Transfection of siRNAs against RCAN1.4 resulted in enhanced Fas- and etoposide-induced apoptosis, which was associated with increased expression and translocation of Bax to mitochondria. Our results suggest that enhanced expression and activation of p53 was responsible for the upregulation of Bax and the increased sensitivity to apoptosis, which could be reversed by p53 knockdown. To explain the observed upregulation of p53, we propose a downregulation of the ubiquitin ligase HDM2, probably translationally. These findings show the importance of appropriate RCAN1.4 expression in the modulation of cell survival and reveal a link between RCAN1.4 and p53.

Keywords: RCAN1, Apoptosis, p53, Bax, HDM2

INTRODUCTION

The human regulator of calcineurin 1 (RCAN-1) gene (also known as Down syndrome candidate region-1, Adapt78, calcipressin1, or modulatory calcineurin-interacting protein 1) was first isolated near the portion of the Down Syndrome Critical Region on chromosome 21, which was purported to contain genes responsible for many features of Down syndrome (Fuentes et al., 1995). The RCAN-1 gene consists of seven exons, and exons 1~4 can be alternatively spliced to yield four transcripts (RCAN1.1 through RCAN1.4). Among these, only RCAN1.1 and RCAN1.4 have been detected in various tissues and cells (Fuentes et al., 1997). Expression of each isoform is differently regulated. RCAN1.4 transcription is inducible by diverse stimuli including growth factors, cytokines, and oxidative stress, whereas RCAN1.1 expression is likely to be constitutive (Harris et al., 2005).

Abnormal expression of RCAN-1 has now been associated with Alzheimer's disease (Ermak et al., 2001) and Down syndrome (Fuentes et al., 2000), which are commonly characterized by neurodegeneration. However, whether elevated expression of this gene is causally implicated in the pathological changes of these disorders remains unclear (Harris et al., 2005; Head et al., 2007). Forced induction of RCAN1.1 protects neuronal cells against potentially lethal calcium and oxidant challenges (Ermak et al., 2002). Consistently, upregulation of RCAN-1 expression has been associated with protection against thapsigargin-induced apoptosis (Zhao et al., 2008). In the same context, T helper type 1 cells from RCAN-1-/- mice showed enhanced apoptosis (Ryeom et al., 2003; Sanna et al., 2006). Similarly, targeted deletion of both RCAN1.1 and RCAN1.4 induces apoptosis of endothelial cells rather than proliferation by the stimulation of vascular endothelial cell growth factor (Ryeom et al., 2008). These findings suggest a positive role for RCAN-1 in cell survival under certain conditions.

In contrast to these reports, primary neurons obtained from RCAN-1-/- mice display an increased resistance to cell death under oxidative stress. Moreover, RCAN-1 overexpression in these cells increases susceptibility to oxidative stress, which has been suggested as a potential pathogenic mechanism in neurodegeneration of Alzheimer's disease and Down syndrome (Porta et al., 2007). Taken together, these conflicting reports suggest a complex role for dosages of this gene in cell survival or death under stress conditions.

The tumor suppressor p53 is a transcription factor with a central role in the regulation of apoptosis, particularly under stress conditions. More than 100 genes are known to be directly activated by p53, many of which promote apoptosis (Vousden and Lu, 2002). One key negative regulator of p53 is the mouse double minute 2 (Mdm2) protein (Kubbutat et al., 1997; Kubbutat et al., 1998). MDM2 and p53 regulate each other through an autoregulatory feedback loop that maintains low p53 activity in nonstressed cells (Wu et al., 1993). The p53 operates in transcription of the MDM2 gene and, in turn, the MDM2 protein inhibits many of the biochemical activities of p53 (Prives, 1998): MDM2 binds to the p53 transactivation domain and directly inhibits its transcriptional activity, exports p53 out of the nucleus, and promotes proteasome-mediated degradation of p53 by functioning as an E3 ubiquitin ligase. Thus the balance between MDM2 and p53 is determinative to cell survival under stress condition.

In this study, we showed that knockdown of RCAN1.4 increases cellular susceptibility to apoptosis induced by Fas ligand or genotoxic stress caused by etoposide, which was coincident with upregulation of p53 and downregulation of MDM2 expression.

METHODS

Chemicals and antibodies

Etoposide was purchased from Calbiochem (San Diego, CA). An activating anti-Fas antibody (clone CH11) was purchased from Millipore (Temecula, CA). Antibodies for caspase-3, -8 (1C12), and -9, cytochrome c (136F3), PARP-1 (46D11), Bax, Bad, p53, phospho-p53 (Ser-15), and phosphor-ATM (Ser-1981) were purchased from Cell Signaling Biotechnology (Beverly, MA). An anti-HDM2 (human ortholog of MDM2) antibody was obtained from Santa Cruz Biotechnologies (Santa Cruz, CA).

Cell culture

U87MG cells (human glioblastoma cells; American Type Culture Collection) were maintained in minimum essential medium supplemented with 0.1 mM nonessential amino acids, 1.0 mM sodium pyruvate, and 10% fetal bovine serum under an atmosphere of 5% CO2 at 37℃.

Plasmid construction

A full-length human homologue of MDM2 (wt-HDM2) and its deletion mutant encoding amino acids 1~440 (HDM2440Δ) were amplified from a cDNA purchased from KRIBB (Daejeon, Korea) and subcloned into pcDNA3.1 using the Directional TOPO Expression Kit (Invitrogen). We engineered a Cys-to-Ala substitution at the zinc-coordinating residue C464 in wt-HDM2 (HDM2C464A) using the QuikChange Site-Directed Mutagenesis Kit (Stratagene). These mutant proteins are stabilized because of a lack of self-ubiquitination and degradation (Fang et al., 2000). The insert sequences of all constructs were confirmed by sequencing. Plasmid transfection was performed using FuGENE6HD (Roche) according to the manufacturer's instructions.

RNA interference

Small interfering RNAs targeting sequences on exon 4 (siDSCR1259) and 3' UTR (siDSCR11348) regions of RCAN1 mRNA are 5'-CUGUGUGGCAAACAGUGAUdTdT-3', and 5'-GUAUCACCUUUCCCAGAUUdTdT-3', respectively. An siRNA targeting p53 mRNA was purchased from Santa Cruz Biotechnologies (Santa Cruz, CA). Cells (3×105/well in a 6-well culture dish) were transfected with the siRNA (40 pmol/well in a 6-well plate) using Lipofectamine RNAiMAX (Invitrogen) according to the manufacturer's instructions.

Real-time quantitative RT-PCR analysis

The mRNA from the cells was prepared using the RNeasy Plus Mini Kit (Qiagen, Germany) according to the manufacturer's instructions. Transcriptional levels of p53 and HDM2 were determined by a one-step quantitative RT-PCR protocol using the FullVelocity SYBR® Green QRT-PCR Master Mix (Stratagene) and an iQ5 Real-Time PCR Detection System (Bio-Rad). Primers for p53, MDM2, and GAPDH were as follows: p53 sense, 5'-TCAACAAGATGTTTTGCCAACTG-3', and antisense, 5'-ATGTGCTGTGACTGCTTGTAGATG-3'; MDM2 sense, 5'-GGAGCAGGCAAATGTGCAATACCA-3', and antisense, 5'-ATGGCTTTGGTCTAACCAGGGTCT-3'; and GAPDH sense, 5'-TGATGACATCAAGAAGGTGG-3', and antisense, 5'-GGCCTCCAAGGAGTAAGAAA-3'.

Luciferase assay

A p53 promoter-luciferase reporter plasmid (p53-Luc) was obtained from Stratagene (La Jolla, CA) and a Renilla luciferase reporter plasmid (pTK-Luc) from Promega (Madison, WI). Cells (5×104/well in a 24-well plate) were transfected with 10 pmol of siRNA using Lipofectamine RNAiMAX. After 24 h, the cells were transfected with 0.4 µg of p53-Luc, and 0.1 µg of pTK-Luc using FuGENE6HD (Roche). Twenty-four hours after the final transfection, luciferase activity was measured with a MiniLumat luminometer (Berthold Technologies GmbH, Bad Wildbad, Germany) using a Dual-Luciferase reporter assay system (Promega) according to the manufacturer's instructions.

Caspase activity

The cytosolic enzymatic activity of caspase-3, -8, and -9 was measured essentially as described in the manufacturer's protocol (Caspase-Glo Assay, Promega). Cells were transfected with siRCANs or a negative control siRNA. Forty-eight hours after the transfection, cells were treated with activating anti-Fas antibody for 6 h or etoposide for 16 h under serum-free conditions. Subsequently, cells were incubated for 30 min at room temperature with an equal volume of caspase-specific substrates (Ac-DEVD-pNA for caspase-3, Ac-LETD-pNA for caspase-8, and Ac-LEHD-pNA for caspase-9) in the buffer provided. The amount of light emitted was measured using a Victor3 (PerkinElmer, USA).

Cell apoptosis assay

Cells were suspended using 0.05% trypsin-EDTA and washed with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) by centrifugation at 3,000 g for 5 min. The cells were then resuspended in the binding buffer (10 mM HEPES, pH 7.4, 140 mM NaCl, and 2.5 mM CaCl2) and incubated with FITC-conjugated Annexin V and propidium iodide (PI) (Annexin V-FITC Kit; Roche Applied Science), according to the manufacturer's protocol. The numbers of apoptotic cells were monitored with a FACSCalibur flow cytometer (BD, USA).

Mitochondria isolation

Mitochondria were isolated using a mitochondria isolation kit (MITO-ISO1; Sigma) following the manufacturer's recommended conditions. Briefly, cells were collected and homogenized by passage 5 times through a 26-gauge needle in extraction buffer (50 mM HEPES, pH 7.5, 1 M mannitol, 350 mM sucrose, and 5 mM EGTA). The homogenate was centrifuged at 600 g for 5 min at 4℃ to separate out the nuclear pellet. Then, the supernatant was centrifuged at 11,000 g for 10 min at 4℃ for separation of the mitochondrial pellet from the cytosolic fraction. The pellet was resuspended and spun again at 11,000 g for 10 min. Cox IV was used to confirm the identity of the mitochondrial fraction. α-tubulin was used to show the absence of cytosol contamination.

Western blot analysis

Immediately after the treatments were completed, cultures were lysed in an appropriate volume of lysis buffer (50 mM Tris pH 7.5, 150 mM NaCl, 1% Triton X-100, 5 mM sodium fluoride, 1 mM sodium orthovanadate, and protease inhibitor mixture). After insoluble material had been removed by centrifugation, the supernatants were mixed with 3× Laemmli sample buffer and denatured for 5 min at 90℃. The proteins were separated by SDS-PAGE (7% or 12%) and transferred to nitrocellulose membranes. The membranes were blocked for 1 h at room temperature in 1% (w/v) Hammersten-grade casein in PBS containing 0.05% Tween 20 followed by immunoblotting with appropriate antibodies in 0.5% casein in PBS. The blots were incubated with horseradish peroxidase-conjugated anti-IgG secondary antibody (Sigma), washed three times with PBS containing 0.05% Tween 20, and then visualized using the SuperSignal West Dura chemiluminescence substrate (Pierce). The band intensity was analyzed using an LAS-3000 image analyzer (Fujifilm, Tokyo, Japan).

RESULTS

RCAN1.4 knockdown enhances anti-Fas antibody- or etoposide-mediated apoptosis of U87MG cells

Because the level of RCAN-1 is associated with cell death under stressful conditions, we examined the effect of suppressing its expression on cell response to apoptosis-inducing stimuli. For this, we designed siRNAs targeted to two different RCAN1.4 mRNA sites (siRCAN259 and siRCAN1348). Transfection of siRCAN259 or siRCAN1348 into U87-MG cells resulted in an approximately 80% and 90% reduction in RCAN1.4 mRNA levels, respectively, as reported previously (Lee et al., 2009). Treatment with anti-Fas antibody (clone CH-11) for 5 h induced apoptosis, and early apoptotic cells were quantified by FACS analysis of Annexin V- and PI-stained cells. Among control siRNA- and siRCAN1348-transfected cells, 11.6% and 20.2%, respectively, were Annexin V positive, suggesting an enhanced Fas-mediated apoptosis by RCAN1.4 knockdown (Fig. 1A). Similarly, RCAN1.4 knocked-down cells exhibited increased cleavage of caspase-3, -8, and -9 to active products, and PARP-1 to an 85-kDa fragment in an siRNA dose-dependent manner after treatment with anti-Fas antibody (Fig. 1B). Genotoxic stress caused by treatment with etoposide yielded similar results (data not shown). In addition, enhanced activation of caspase-3, -8, and -9 was detected in the in vitro assay using cell lysates from RCAN1.4 knocked-down cells after Fas antibody or etoposide treatments (Fig. 1C).

Fig. 1.

RCAN1.4 knockdown enhances Fas-antibody- or etoposide-mediated apoptosis in U87MG cells. (A) Cells were transfected with siRNA against RCAN1.4 (siRCAN259) or negative control siRNA (siCon). After 48 h, cells were treated with an activating anti-Fas antibody (CH11) for 5 h to induce apoptosis. Cells were then washed, stained with Annexin V, and analyzed by FACS. (B) Cells transfected with two doses of siRCAN259 (20 and 40 pmol/well in a 6-well plate) were treated with activating anti-Fas antibody and then subjected to immunoblot analysis for the indicated proteins. (C) Cells transfected with the indicated siRNAs were treated with activating anti-Fas antibody for 6 h or etoposide for 16 h. The cells were then subjected to a caspase activity assay (Promega) according to the manufacturer's instructions.

RCAN1.4 knockdown enhances mitochondria-mediated apoptosis

In a further attempt to investigate the molecular mechanism underlying RCAN1.4 knockdown-mediated enhancement of apoptosis, we examined the involvement of the mitochondria-related apoptosis molecules, cytochrome c and Smac. Western blot analysis showed that siRCANs strongly enhanced the release of these molecules from mitochondria to cytosol after anti-Fas antibody or etoposide treatments (Fig. 2A). To further confirm the importance of mitochondria in the induction of apoptosis, we examined the involvement of Bad and Bax, the best-characterized Bcl-2 family proteins involved in the regulation of apoptotic cell death. Translocation of these proteins from cytosol to mitochondria increases outer mitochondrial membrane permeabilization, allowing the apoptotic effectors cytochrome c and Smac to leak from the mitochondria (Hsu et al., 1997; Wolter et al., 1997). As Fig. 2B shows, translocation of Bax to mitochondria was enhanced in RCAN-1.4 knocked-down cells compared with control cells, while translocation of Bad did not differ between the two groups.

Fig. 2.

RCAN1.4 knockdown enhances mitochondria-mediated apoptosis. Forty-eight hours after transfection with siRCAN259, siRCAN1348, or siCon, cells were treated with activating anti-Fas antibody for 6 h or etoposide for 16 h. After cells were disrupted as indicated in the methods section, the cytosol fractions (A) or the mitochondrial fractions (B) were subjected to immunoblot analysis for the indicated proteins.

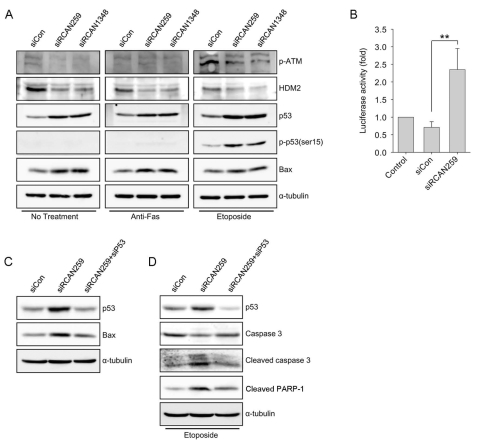

An elevated p53-Bax axis is responsible for the enhanced response to apoptosis

Western blot analysis of whole cell lysates revealed that transfection with siRCANs upregulated expression of Bax and p53, while HDM2 expression was downregulated in a steady state and after anti-Fas antibody or etoposide treatments (Fig. 3A). Furthermore, the RCAN1.4 knockdown enhanced etoposide-mediated phosphorylation at serine 15 of p53, which is associated with functional activation of p53 in DNA-damaged cells, suggesting increased activation of p53 by RCAN1.4 knockdown. To confirm this, we carried out a promoter assay to evaluate whether knockdown of RCAN1.4 increased the transcriptional activity of p53. As Fig. 3B shows, the luciferase activity in siRCAN259-transfected cells was elevated 3-fold compared to control. Because p53 transcriptionally regulates Bax expression (Miyashita et al., 1994), we next tested whether increased p53 activation was responsible for Bax expression upregulation in RCAN1.4 knocked-down cells. Cotransfection of siRNA against p53 blocked the increased Bax expression (Fig. 3C). In addition, p53 knockdown attenuated etoposide-induced cleavage of caspase-3 and PARP-1 after treatment with etoposide (Fig. 3D). These results suggest that elevated expression of p53 in RCAN1.4 knocked-down cells is responsible for the enhanced apoptosis.

Fig. 3.

RCAN1.4 knockdown upregulates Bax and p53 expression. (A) Forty-eight hours after transfection with the indicated siRNAs, cells were treated with activating anti-Fas antibody for 6 h or etoposide for 16 h. Whole lysates from the cells were subjected to immunoblot analysis for the indicated proteins. (B) Twenty-four hours after transfection with the indicated siRNAs, cells were transfected with a vector containing p53-Luc. Twenty-four hours after the final transfection, luciferase activities were measured. The results are presented as the average±SD (Student's t test; **p<0.001). (C) Forty-eight hours after transfection with the indicated siRNAs, whole lysates from the cells were subjected to immunoblot analysis for the indicated proteins. (D) Forty-eight hours after transfection with the indicated siRNAs, cells were treated with etoposide for 16 h. Whole lysates from the cells were subjected to immunoblot analysis for the indicated proteins.

Notably, RCAN1.4 knocked-down cells showed attenuated etoposide-mediated phosphorylation of ATM (Fig. 3A), which acts as an upstream kinase for serine 15 of p53 in response to DNA damage (Banin et al., 1998; Canman et al., 1998). This result suggests that the accentuated phosphorylation of p53 in RCAN1.4 knocked-down cells is not attributable to increased DNA damage compared to control cells after etoposide treatment.

RCAN1.4 knockdown decreases HDM2 expression

We next confirmed that transfection of siRCAN259 increased p53 expression while decreasing HDM2 levels in a dose-dependent manner (Fig. 4A). To test how knockdown of RCAN1.4 affects p53 and HDM2 expression at the transcriptional step, we examined mRNA levels of these proteins using real-time PCR analysis. In contrast to protein levels, HDM2 mRNA levels were elevated by knockdown of RCAN1.4, while p53 mRNA levels remained unchanged (Fig. 4B and 4C). Because HDM2 negatively regulates the protein stability of p53, we addressed the mechanism responsible for the low HDM2 protein level in spite of its high transcription. Expression vectors carrying metabolically stable mutants of HDM2 were transfected into U87-MG cells. The protein expression of these mutants was higher than in the wt-HDM2. However, RCAN1 knockdown attenuated all protein expression to a similar extent (Fig. 4D), suggesting that the low expression of HDM2 is not attributable to its protein instability.

Fig. 4.

RCAN1.4 knockdown increases p53 expression while decreasing HDM2 expression. (A) Forty-eight hours after transfection with three doses of siRCAN259 (5, 20, or 40 pmol/well in a 6-well plate), whole lysates from the cells were subjected to immunoblot analysis for the indicated proteins. (B, C) Forty-eight hours after transfection with siRCAN259, p53 and HDM2 transcript levels were measured by real-time RT-PCR. (D) Twenty-four hours after transfection with siRCAN259 or siCon, cells were transfected with a vector containing wild-type (wt-HDM2) or mutants (C464A and 440Δ) of HDM2. Twenty-four hours after the final transfection, whole lysates from the cells were subjected to immunoblot analysis with an antibody specific to HDM2.

DISCUSSION

Although RCAN1 expression levels have been associated with cell survival under stress, the functional role of this protein in death-inducing signaling remains unclear. In this study, we demonstrated that RCAN1.4 knockdown increases susceptibility of U87-MG cells to anti-Fas antibody- and etoposide-induced apoptosis. This finding is in accordance with those of previous reports observing increased apoptosis in CD4+ T cells from RCAN1-null mice after CD3 stimulation (Ryeom et al., 2003). McKeon and colleagues suggested that the elevated expression of Fas ligand underlies a mechanism for the cell death seen in the RCAN1-deficient T cells (Ryeom et al., 2003). However, this idea is not applicable in our case because enhanced apoptosis was also observed under genotoxic stress caused by etoposide. On the other hand, Bad activation resulting from enhanced dephosphorylation by hyperactivated calcineurin has been proposed as a mechanism for the apoptosis observed in vascular endothelial cells from RCAN1-deficient mice (Ryeom et al., 2008). Because RCAN1 is known as an endogenous inhibitor of calcineurin (Fuentes et al., 2000; Rothermel et al., 2000), this explanation is plausible for our case. However, we observed no increase in Bad translocation to mitochondria in RCAN1.4 knocked-down cells.

On the other hand, our results showed increased expression of the pro-apoptotic Bcl-2 protein Bax and its translocation to mitochondria, resulting in the more pronounced leaking of apoptotic effectors in RCAN1.4 knocked-down cells. Increased Bax expression was the result of increased activation of p53, a positive transcriptional regulator of Bax. Although we detected upregulation of p53 protein expression, mRNA levels were not elevated in RCAN1.4 knocked-down cells compared with control cells. Thus, we did not completely solve the mechanism by which RCAN1.4 knock-down increases p53 protein levels in this study, but our results indicate downregulated HDM2 levels as a possible explanation for stabilization of the p53 protein.

HDM2 mRNA levels were higher by about 2-fold in RCAN1.4 knocked-down cells compared with control cells. Increased p53 activation may be responsible for this increase because HDM2 is a transcriptional target of p53 (Barak et al., 1993). In studies to test the protein stability of HDM2, we found no enhanced degradation of HDM2 protein (data not shown). In addition, RCAN1.4 knockdown also downregulated expression of metabolically stabilized mutants of HDM2. Thus, low HDM2 levels were not the result of inhibition of its transcription.

Recently, we reported that knockdown of RCAN1.4 results in downregulation of global translation (Lee et al., 2009) when translation of some susceptible mRNAs is preferentially inhibited. In this context, HDM2 mRNA is considered as a "weak" mRNA that is outcompeted by "strong" mRNAs when the rate of translation initiation is reduced (De Benedetti and Graff, 2004).

This hypothesis and other possible mechanisms for stabilization of p53 protein, including acetylation, methylation, and phosphorylation, remain to be studied. In summary, the results we have presented here establish the importance of proper expression of RCAN1.4 in cell survival under apoptosis-inducing conditions and reveal a link between RCAN1 and p53.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This research was supported by R13-2002-005-04002-0 from MRC for the Cell Death Disease Research Center funded by the Korea Science and Engineering Foundation (KOSEF), and by the Catholic Medical Center Research Foundation made in program year 2007.

ABBREVIATIONS

- RCAN-1

regulator of calcineurin 1

- MDM2

mouse double minute 2

- Smac

second mitochondria-derived activator of caspase

- Cox IV

cytochrome oxidase subunit IV

- Bad

Bcl-2-associated death promoter

- Bax

Bcl-2-associated X protein

- ATM

ataxia telangiectasia mutated kinase

References

- 1.Banin S, Moyal L, Shieh S, Taya Y, Anderson CW, Chessa L, Smorodinsky NI, Prives C, Reiss Y, Shiloh Y, Ziv Y. Enhanced phosphorylation of p53 by ATM in response to DNA damage. Science. 1998;281:1674–1677. doi: 10.1126/science.281.5383.1674. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Barak Y, Juven T, Haffner R, Oren M. Mdm2 expression is induced by wild type p53 activity. EMBO J. 1993;12:461–468. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1993.tb05678.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Canman CE, Lim DS, Cimprich KA, Taya Y, Tamai K, Sakaguchi K, Appella E, Kastan MB, Siliciano JD. Activation of the ATM kinase by ionizing radiation and phosphorylation of p53. Science. 1998;281:1677–1679. doi: 10.1126/science.281.5383.1677. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.De Benedetti A, Graff JR. eIF-4E expression and its role in malignancies and metastases. Oncogene. 2004;23:3189–3199. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1207545. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ermak G, Harris CD, Davies KJ. The DSCR1 (Adapt78) isoform 1 protein calcipressin 1 inhibits calcineurin and protects against acute calcium-mediated stress damage, including transient oxidative stress. FASEB J. 2002;16:814–824. doi: 10.1096/fj.01-0846com. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ermak G, Morgan TE, Davies KJ. Chronic overexpression of the calcineurin inhibitory gene DSCR1 (Adapt78) is associated with Alzheimer's disease. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:38787–38794. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M102829200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fang S, Jensen JP, Ludwig RL, Vousden KH, Weissman AM. Mdm2 is a RING finger-dependent ubiquitin protein ligase for itself and p53. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:8945–8951. doi: 10.1074/jbc.275.12.8945. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fuentes JJ, Genesca L, Kingsbury TJ, Cunningham KW, Perez-Riba M, Estivill X, de la Luna S. DSCR1, overexpressed in Down syndrome, is an inhibitor of calcineurin-mediated signaling pathways. Hum Mol Genet. 2000;9:1681–1690. doi: 10.1093/hmg/9.11.1681. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fuentes JJ, Pritchard MA, Estivill X. Genomic organization, alternative splicing, and expression patterns of the DSCR1 (Down syndrome candidate region 1) gene. Genomics. 1997;44:358–361. doi: 10.1006/geno.1997.4866. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fuentes JJ, Pritchard MA, Planas AM, Bosch A, Ferrer I, Estivill X. A new human gene from the Down syndrome critical region encodes a proline-rich protein highly expressed in fetal brain and heart. Hum Mol Genet. 1995;4:1935–1944. doi: 10.1093/hmg/4.10.1935. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Harris CD, Ermak G, Davies KJ. Multiple roles of the DSCR1 (Adapt78 or RCAN1) gene and its protein product calcipressin 1 (or RCAN1) in disease. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2005;62:2477–2486. doi: 10.1007/s00018-005-5085-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Head E, Lott IT, Patterson D, Doran E, Haier RJ. Possible compensatory events in adult Down syndrome brain prior to the development of Alzheimer disease neuropathology: targets for nonpharmacological intervention. J Alzheimers Dis. 2007;11:61–76. doi: 10.3233/jad-2007-11110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hsu YT, Wolter KG, Youle RJ. Cytosol-to-membrane redistribution of Bax and Bcl-X(L) during apoptosis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1997;94:3668–3672. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.8.3668. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kubbutat MH, Jones SN, Vousden KH. Regulation of p53 stability by Mdm2. Nature. 1997;387:299–303. doi: 10.1038/387299a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kubbutat MH, Ludwig RL, Ashcroft M, Vousden KH. Regulation of Mdm2-directed degradation by the C terminus of p53. Mol Cell Biol. 1998;18:5690–5698. doi: 10.1128/mcb.18.10.5690. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lee HJ, Kim YS, Sato Y, Cho YJ. RCAN1-4 knockdown attenuates cell growth through the inhibition of Ras signaling. FEBS Lett. 2009;583:2557–2564. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2009.07.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Miyashita T, Krajewski S, Krajewska M, Wang HG, Lin HK, Liebermann DA, Hoffman B, Reed JC. Tumor suppressor p53 is a regulator of bcl-2 and bax gene expression in vitro and in vivo. Oncogene. 1994;9:1799–1805. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Porta S, Serra SA, Huch M, Valverde MA, Llorens F, Estivill X, Arbones ML, Marti E. RCAN1 (DSCR1) increases neuronal susceptibility to oxidative stress: a potential pathogenic process in neurodegeneration. Hum Mol Genet. 2007;16:1039–1050. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddm049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Prives C. Signaling to p53: breaking the MDM2-p53 circuit. Cell. 1998;95:5–8. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81774-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rothermel B, Vega RB, Yang J, Wu H, Bassel-Duby R, Williams RS. A protein encoded within the Down syndrome critical region is enriched in striated muscles and inhibits calcineurin signaling. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:8719–8725. doi: 10.1074/jbc.275.12.8719. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ryeom S, Baek KH, Rioth MJ, Lynch RC, Zaslavsky A, Birsner A, Yoon SS, McKeon F. Targeted deletion of the calcineurin inhibitor DSCR1 suppresses tumor growth. Cancer Cell. 2008;13:420–431. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2008.02.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ryeom S, Greenwald RJ, Sharpe AH, McKeon F. The threshold pattern of calcineurin-dependent gene expression is altered by loss of the endogenous inhibitor calcipressin. Nat Immunol. 2003;4:874–881. doi: 10.1038/ni966. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sanna B, Brandt EB, Kaiser RA, Pfluger P, Witt SA, Kimball TR, van Rooij E, De Windt LJ, Rothenberg ME, Tschop MH, Benoit SC, Molkentin JD. Modulatory calcineurin-interacting proteins 1 and 2 function as calcineurin facilitators in vivo. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103:7327–7332. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0509340103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Vousden KH, Lu X. Live or let die: the cell's response to p53. Nat Rev Cancer. 2002;2:594–604. doi: 10.1038/nrc864. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wolter KG, Hsu YT, Smith CL, Nechushtan A, Xi XG, Youle RJ. Movement of Bax from the cytosol to mitochondria during apoptosis. J Cell Biol. 1997;139:1281–1292. doi: 10.1083/jcb.139.5.1281. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wu X, Bayle JH, Olson D, Levine AJ. The p53-mdm-2 autoregulatory feedback loop. Genes Dev. 1993;7:1126–1132. doi: 10.1101/gad.7.7a.1126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zhao P, Xiao X, Kim AS, Leite MF, Xu J, Zhu X, Ren J, Li J. c-Jun inhibits thapsigargin-induced ER stress through up-regulation of DSCR1/Adapt78. Exp Biol Med (Maywood) 2008;233:1289–1300. doi: 10.3181/0803-RM-84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]