Case one

A 28-year-old Aboriginal woman was admitted to hospital after presenting to the emergency department with a three-day history of fever, chills, difficulty swallowing because of a sore throat, and cough with production of sputum. The patient’s history included juvenile rheumatoid arthritis that was in remission. She reported that she used cocaine on a daily basis. On examination, the patient’s blood pressure was 120/80, her heart rate was 145 beats/min, her respiratory rate was 20 breaths per minute, and her temperature was 39.1° C. A chest radiograph showed an infiltrate in the lower lobe of her right lung. Initial blood tests showed severe neutropenia with an absolute neutrophil count of less than 100 cells/mm3. A subsequent urine test was positive for levamisole. On further questioning, the patient mentioned that she had changed to a different cocaine dealer two days before the onset of her symptoms.

The patient was given antibiotics for pneumonia. Filgrastim (recombinant human granulocyte colony-stimulating factor) was given at 300 μg per day. During her hospital stay, the patient’s neutrophil count gradually normalized. Against medical advice, she left hospital on day five. On day 20, she was seen at a walk-in clinic for recurrent respiratory symptoms, which were treated with oral penicillin. On day 30, she presented again to the emergency department and was found to have an absolute neutrophil count of 300 cells/mm3. The patient was admitted to hospital and broad-spectrum antibiotic therapy was started. She was also given acyclovir for oral ulcers suspected to be herpetic in origin.

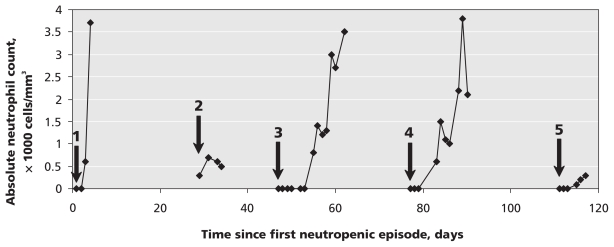

A urinalysis confirmed the presence of levamisole, and further testing showed the presence of human leukocyte antigen (HLA) B27 and rheumatoid factor. On day six, after a partial recovery of her neutrophil count to 800 cells/mm3, the patient again left against medical advice. Over the next 80 days (i.e., to date), the patient presented three more times to the emergency department with febrile neutropenia, each time responding to broad-spectrum antibiotics and, likely, the discontinuation of her cocaine use. Her use of cocaine that was probably contaminated with levamisole continued between each of these visits and presumably continued to induce her neutropenia (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Chronological depiction of five neutropenic episodes over a 120-day period in a 28-year-old woman. Arrows show admissions to hospital. An absolute neutrophil count of 0 indicates 100 (normal 2000–8000) cells/mm3.

Case two

A 60-year-old white man was admitted to hospital after presenting to the emergency department with a one-day history of fever, sore throat and malaise. A complete blood count showed an absolute neutrophil count of less than 100 cells/mm3. The patient reported that he had used cocaine about 24 hours before presenting. He had been admitted six months previously for febrile neutropenia, but a cause had not been identified at that time. The previous episode had also occurred within 24 hours after exposure to cocaine.

A urine sample was sent for a levamisole assay, and a sample of the patient’s cocaine was submitted to the laboratory of the drug analysis service to be tested for levamisole. Both tests were positive. Blood cultures remained negative throughout the patient’s stay in hospital.

The patient was given broad-spectrum antibiotics on admission. His fever resolved within 24 hours, and he remained afebrile for the remainder of his hospital stay. He did not receive granulocyte colony-stimulating factor. When discharged on day six, the patient was prescribed oral antibiotics and instructed to take them until his neutrophil count rose above 1000 cells/mm3, which occurred on day 11. Genetic analysis of a sample of the patient’s sputum was negative for the presence of HLA-B27.

Discussion

Illicit drug use continues to cause adverse drug-related events among substance abusers worldwide. Levamisole is among the many contaminants that have been found in seized cocaine. An antimicrobial belonging to the class of imidazothiazole derivatives, this agent has been reported recently in a high proportion of seized cocaine throughout North America and Europe.

Historically, the primary therapeutic uses of levamisole have been as treatment for rheumatoid arthritis and various cancers, and as an antihelminthic agent in both humans and animals. The drug is currently not licensed for human use in Canada. In British Columbia, 20% of about 8000 cocaine samples analyzed at the drug analysis laboratory of Health Canada tested positive for the presence of levamisole (or its optical isomer). To date in 2009, about 46% of cocaine samples have tested positive, suggesting a possible increase in the prevalence of levamisole in cocaine in British Columbia (Richard Laing, Manager, Drug Analysis Service Laboratory of Health Canada, Burnaby (BC): unpublished data, 2009). However, this statistic may not reflect the true prevalence of levamisole-contaminated cocaine on the street, because these results were not derived from a random sampling. Levamisole has also been detected in cocaine seizures in other jurisdictions, with similarly high rates of prevalence in some instances.1,2

Reports of severe agranulocytosis, possibly related to levamisole, began to surface in 2008 in Northern Alberta and various regions of British Columbia, including the Fraser Valley.3,4 Since then, several reports have been released from New Mexico and Colorado confirming the findings in Western Canada.5 Given the various social and health-related issues facing most patients who use cocaine, this toxic reaction is likely occurring on a largely unreported and undiagnosed basis. In our small 100-bed community hospital in British Columbia, we identified five patients (comprising 11 different admissions to hospital) over the course of just eight months who had febrile neutropenia that was likely secondary to use of cocaine contaminated with levamisole.

Although the reason for the addition of levamisole to cocaine is unknown, it may be that levamisole promotes the effects of cocaine by inhibition of uptake 1 (i.e., presynaptically), resulting in diminished catecholamine reuptake in the synapse.6

Risk factors for agranulocytosis

Little is known about why levamisole induces agranulocytosis in some people and not others. Other imidazothiazole derivatives have not been reported to cause a similar reaction. No reports of agranulocytosis were published when levamisole was first used in humans as an antihelminthic agent during the early 1970s. Instances of the reaction emerged with the use of levamisole as a treatment for rheumatoid arthritis in the late 1970s and early 1980s, providing clues to a possible cause and genetic predisposition. The incidence of agranulocytosis among patients with rheumatoid arthritis was determined to be as high as 20%, although reports varied.7 Several small studies involving patients with rheumatoid arthritis and related disorders reported a strong association between the development of agranulocytosis and the presence of HLA-B27.8–10

A case series involving six patients with levamisole-induced agranulocytosis found that the patients had either induced leukocyte-agglutinating antibodies or lymphocyto-toxic antibodies, or both. The mechanism by which levamisole causes these antibodies to occur is not well understood.10 Notably, tests for HLA-B27 in three of four of our affected patients were positive — a finding that was consistent with data reported in the literature on rheumatoid arthritis. In all but one of these patients, the presence of levamisole was confirmed either by tests of samples of the cocaine used before a neutropenic episode or by urine assay.

To date, no prospective research has been conducted to further elucidate the epidemiology (both genetic and non-genetic) of levamisole toxicity among cocaine users. Current observation of instances reported to the Centre for Disease Control in British Columbia suggests that the reaction occurs more commonly in women than men (as seen in case reports in the 1970s and 1980s) and is more common in the Aboriginal population.3 Smokers of crack cocaine appear to be at increased risk.

Clinical management

The length of time between exposure to levamisole and onset of neutropenia varies. In one patient, flu-like symptoms began within 12 hours after exposure, and documented neutropenia within 24 hours. (The patient’s most recent exposure before this instance had been about six months previously). In another patient, both symptomatic illness and neutropenia were seen about three weeks after the last cocaine exposure. In all patients at our institution, the diagnosis of levamisole-induced neutropenia was not initially considered, mainly because we lacked awareness of this common contaminant and its potential to induce profound neutropenia.

Primary treatment of neutropenia caused by levamisole should be supportive, with administration of broad-spectrum antimicrobials, including vancomycin for patients at risk of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus. The use of filgrastim, in our experience, did not appear to provide significantly greater benefit over watchful waiting. All affected patients experienced recovery of their neutrophil counts within five to ten days, regardless of whether they received filgrastrim therapy.

The implications for public health of levamisole-adulterated cocaine are not trivial, and efforts should be made to increase awareness of its potential danger among health care providers and the general public. Research aimed at clarifying the most significant risk factors for levamisole-induced neutropenia among cocaine users is also needed.

Key points

Levamisole-induced neutropenia should be considered in patients presenting with neutropenia and a history of cocaine use.

Primary treatment of neutropenia caused by levamisole should be supportive, with administration of broad-spectrum antimicrobials.

Granulocyte colony-stimulating factor is not usually necessary because neutrophil count generally recovers within 5–10 days after discontinuation of cocaine use.

The section Cases presents brief case reports that convey clear, practical lessons. Preference is given to common presentations of important rare conditions, and important unusual presentations of common problems. Articles start with a case presentation (500 words maximum), and a discussion of the underlying condition follows (1000 words maximum). Generally, up to five references are permitted and visual elements (e.g., tables of the differential diagnosis, clinical features or diagnostic approach) are encouraged. Written consent from patients for publication of their story is a necessity and should accompany submissions. See information for authors at www.cmaj.ca.

Acknowledgment

The authors thank Richard Laing, manager of the Health Canada Drug Analysis Laboratory, for testing several samples of cocaine from cases we identified.

Footnotes

Competing interests: None declared.

Previously published at www.cmaj.ca

This article has been peer reviewed.

REFERENCES

- 1.Zhu NY, Legatt DF, Turner AR. Agranulocytosis after consumption of cocaine adulterated with levamisole. Ann Intern Med. 2009;150:287–9. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-150-4-200902170-00102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fucci N. Unusual adulterants in cocaine seized on italian clandestine market. Forensic Sci Int. 2007;172:e1. doi: 10.1016/j.forsciint.2007.05.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Buxton J. Agranulocytosis (neutropenia) associated with levamisole in cocaine. Vancouver (BC): BC Centre for Disease Control; 2009. [(accessed 2009 Nov. 24)]. Available: www.bccdc.org/downloads/Agranulocytosis%20%28neutropenia%29%20associated%20with%20levamisole%20in%20cocaine.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Haggarty S. Public health advisory — street drug use. Edmonton (AB): Alberta Health and Wellness; 2008. [(accessed 2009 Oct. 29)]. Available: www.alberta.ca/acn/200811/24852E488A7D1-D56E-ECB6-041A8A479736C2BE.html. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Department of Health investigates unusual condition that harms immune system: potential cocaine contamination could be cause. Santa Fe (NM): New Mexico Department of Health; 2009. [(accessed 2009 Nov. 24)]. Available: www.health.state.nm.us/documents/agranulocytosis1-16-09.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gulati OD, Hemavathi KG, Joshi DP. Interactions of levamisole with some autonomic drugs on guinea-pig vas deferens. J Auton Pharmacol. 1985;5:19–23. doi: 10.1111/j.1474-8673.1985.tb00561.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Williams GT, Johnson SAN, Dieppe PA, et al. Neutropenia during treatment of rheumatoid arthritis with levamisole. Ann Rheum Dis. 1978;37:366–9. doi: 10.1136/ard.37.4.366. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Schmidt KL, Mueller-Eckhardt C. Agranulocytosis, levamisole, and HLA-B27. Lancet. 1977;2:85. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(77)90082-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mielants H, Veys EM. B27 and agranulocytosis in rheumatoid arthritis patients treated with levamisole. Acta Rhumatol. 1979;3:104–7. discussion 107–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hodinka L, Geher P, Meretey K, et al. Levamisole-induced neutropenia and agran-ulocytosis: Association with HLA B27 leukocyte agglutinating and lymphocytotoxic antibodies. Int Arch Allergy Appl Immunol. 1981;65:460–4. doi: 10.1159/000232788. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]