Abstract

Steroid hormones are essential in normal physiology whereas disruptions in hormonal homeostasis represent an important etiological factor for many human diseases. Steroid hormones exert most of their functions through the binding and activation of nuclear hormone receptors (NRs or NHRs), a superfamily of DNA-binding and often ligand-dependent transcription factors. In recent years, accumulating evidence has suggested that NRs can also regulate the biosynthesis and metabolism of steroid hormones. This review will focus on the recent progress in our understanding of the regulatory role of NRs in hormonal homeostasis and the implications of this regulation in physiology and diseases.

This article summarizes our understanding of the regulatory role of NRs in hormonal homeostasis and the implications of this regulation in physiology and diseases.

Small lipophilic molecules, such as steroids, thyroid hormones, and active forms of vitamin A (retinoids) and vitamin D, play an important role in the growth, differentiation, metabolism, reproduction, and morphogenesis of higher organisms and humans (1,2). Most cellular actions of these lipophilic molecules are mediated through their binding to nuclear receptors (NRs). Most NRs have a conserved N-terminal DNA binding domain that can recognize single or double sequence (AGGTCA) in direct, everted, or inverted repeats (3). In the presence of ligands that bind to the C-terminal ligand-binding domain of the receptors, NRs bind to their cognate sequences as monomers, homodimers, or heterodimers to activate or repress their target gene expression. Nearly 50 vertebrate NRs have been cloned. Among them, about 40 were cloned before knowing their ligands and physiological functions; for this reason, they were termed “orphan receptors.” Since their initial cloning, the endogenous or synthetic ligands have been identified for many of these orphan receptors, converting them to adopted orphans (4).

Whereas steroid hormones exert their effects through NRs, accumulating evidence has suggested that NRs can also regulate both the production and elimination of steroid hormones. This review will focus on the recent progress in our understanding of the regulatory role of NRs in hormonal homeostasis and the implications of this regulation in physiology and diseases.

Liver X Receptor (LXR) in Glucocorticoid, Estrogen, and Androgen Homeostasis

LXR in glucocorticoid homeostasis

The synthesis and release of adrenal glucocorticoids are tightly regulated by the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis. CRH, produced in the hypothalamus, signals on the pituitary to regulate the production of ACTH (5). ACTH acts on the adrenal gland to increase the expression of a cascade of enzymes required for the conversion of cholesterol to glucocorticoids. The initial and rate-limiting step in this cascade is mediated by the steroidogenic acute regulatory protein (StAR), which transfers cholesterol from the outer to the inner mitochondrial membrane (6,7). Inside the mitochondria, cytochrome P450 11A1 (CYP11A1) cleaves the cholesterol side chain to form pregnenolone (8), which can be further converted by a series of enzymes, including 3β-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase (3β-HSD), P45011β (CYP11b1), and P450aldo (CYP11b2), to steroid hormones.

It has been reported that LXRs can regulate adrenal cholesterol balance and glucocorticoid steroidogenesis. LXRs, including the α- and β-isoforms, were defined as sterol sensors (9). Activation of LXRs can regulate cholesterol metabolism by controlling the expression of ABC transporters (ABCA1, ABCG5, ABCG8, and ABCG1) (10,11,12), as well as hepatic cytochrome P450 7A1 (CYP7A1), which converts cholesterol to bile acids (13). The adrenal gland expresses both LXRα and LXRβ (14). Several groups have recently reported that LXRs can regulate adrenal steroidogenesis (7,15,16,17,18).

Cummins et al. (7) reported that activation of LXRs increased glucocorticoid secretion by regulating cholesterol metabolism in the adrenal gland. The level of cholesterol esters in the adrenal cells of LXRα−/− mice increased substantially compared with those of wild-type mice (7,19), consistent with the loss of LXR-mediated cholesterol efflux pathway. As a result of increased cholesterol accumulation, LXRα−/− mice had doubled basal conversion of cholesterol to corticosterone in vivo. Surprisingly, treatment of wild-type mice with the synthetic LXR agonist T0901317 resulted in a stimulated corticosterone synthesis, comparable to the elevated synthesis in LXRα−/− mice (7,19). In an effort to explain this anomaly, the authors found that several key steroidogenic genes, including StAR, CYP11A1, and 3β-HSD, were highly induced by LXRα. Remarkably, the expression of each of these genes was elevated in adrenal cells derived from both T0901317-treated wild-type mice and LXRα−/− mice (7,19). In the same study, the StAR gene was identified as a target gene of LXRα (7). It was proposed that, in the absence of an exogenously added ligand, LXRα repressed the basal expression of StAR, perhaps through the recruitment of corepressors (7). Thus, loss of LXRα resulted in the activation of StAR gene expression. As such, both loss and activation of LXRα could result in the same outcome of StAR gene activation.

Interestingly, results from two subsequent studies suggested that activation of LXRs may increase the glucocorticoid level by elevating the serum concentration of ACTH through two distinct mechanisms (16,18). Nilsson et al. (18) reported that treatment of the human adrenal H295R cell line with the synthetic LXR agonist GW3965 suppressed the steroid hormone production, which was opposite to the previous report (7). Instead, the authors found that the ACTH level was increased both in pituitary cell lines and in LXR ligand-treated mice (18). Treatment with the LXR agonist also suppressed the expression of 11β-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase type 1 (11β-HSD1) both in pituitary gland and pituitary cell line. 11β-HSD1 converts inactive glucocorticoids to active glucocorticoids in the pituitary gland, fulfilling an important role in the feedback suppression of glucocorticoidogenesis (20). The down-regulation of pituitary 11β-HSD1 expression might reduce the negative feedback of adrenal glucocorticoidogenesis, thereby enhancing pituitary ACTH production (18). Based on these results, Nilsson et al. (18) concluded that LXRs indirectly regulated the ACTH expression by down-regulating the negative feedback. In an independent study, Matsumoto et al. (16) reported that pituitary proopiomelanocortin (POMC), the precursor of ACTH, is a target gene of LXRs. Treatment with T0901317 increased the mRNA expression of POMC gene both in vivo and in vitro. Treatment with T0901317 also activated the rat POMC gene promoter in pituitary cell lines, and this effect was abolished when LXRα was knocked down. These results suggest that LXRs may elevate the glucocorticoid level by directly activating the ACTH gene expression. It remains to be determined whether the discrepancies among these studies resulted from the use of different experimental systems and whether the LXR effect on glucocorticoid homeostasis has species specificity.

LXR in estrogen homeostasis

Circulating estrogens are primarily produced in the ovary in premenopausal women. After menopause, the ovary ceases to produce estrogens, but estrogens continue to be synthesized in extraovarian tissues, including the breast tissue, through the aromatization of circulating androgens to estrogens (21). The conversion of androgens to estrogens is catalyzed by the aromatase (21,22). Estrogens play an important role in normal physiology (23,24). However, estrogens also represent a risk factor for breast cancer. As such, antiestrogen therapies are effective for breast cancers. A critical metabolic pathway to deactivate estrogens is through the estrogen sulfotransferase (EST, also called SULT1E1)-mediated sulfation (25). Sulfonated estrogens cannot bind to and activate the estrogen receptor (ER), and thus lose their hormonal activities (26). EST/SULT1E1 is believed to be the primary SULT isoform responsible for estrogen’s sulfonation at physiological concentration due to the high affinity of this enzyme to estrogens (27).

Gong et al. (28) showed that LXR controls estrogen homeostasis by regulating the basal and inducible hepatic expression of EST/SULT1E1. Genetic (using the constitutively activated viral protein 16-LXRα transgene) or pharmacological (using LXR agonists) activation of LXR resulted in EST/SULT1E1 induction, which, in turn, inhibited estrogen-dependent uterine epithelial proliferation and gene expression, as well as human breast cancer growth in a xenograft model. The authors further established that EST/SULT1E1 is a transcriptional target of LXR, and deletion of the EST/SULT1E1 gene in mice abolished the LXR effect on estrogen deprivation. Interestingly, EST/SULT1E1 regulation by LXR appeared to be liver-specific, further underscoring the role of liver in estrogen metabolism. Activation of LXR failed to induce other major estrogen-metabolizing enzymes, suggesting that the LXR effect on estrogen metabolism is achieved by EST/SULT1E1 regulation. These results have revealed a novel mechanism controlling estrogen homeostasis in vivo and may have implications for drug development in the treatment of breast cancer and other estrogen-related cancerous endocrine disorders.

LXR in androgen homeostasis

Androgens, including testosterone and dihydrotestosterone, are essential for the regulation of breeding in males. Many other physiological, morphological, and behavioral traits related to reproduction are also androgen dependent (29). The prostate is one of the major androgen-responsive tissues (30). Through binding to and activating the androgen receptor, androgens play critical roles in prostate development, growth, and pathogenesis of benign prostate hyperplasia and prostate cancer (30,31). As such, androgen deprivation is the cornerstone treatment of hormone-dependent prostate cancer. Other than castration and the use of antiandrogens, an important pathway to metabolically deactivate androgens is through the sulfotransferase (SULT)-mediated sulfonation, because sulfonated androgens cannot bind to and activate androgen receptor. The primary SULT isoform responsible for androgen sulfonation at physiological concentration is believed to be the hydroxysteroid sulfotransferase SULT2A1 (32,33). In addition to SULT2A1, the steroid sulfatase (STS) also plays a role in androgen homeostasis. Sulfonated androgens can be desulfonated within target tissues, such as the prostate, and converted to active androgens. Indeed, STS inhibitors have been explored as antiprostate cancer drugs (34).

Uppal et al. (35) have previously reported that SULT2A1 is a LXR target gene. Activation of LXR in mice conferred resistance, whereas loss of LXRs sensitized mice to cholestasis. These results are consistent with the notion that SULT2A1 plays an important role in the sulfation and detoxification of bile acids (36). Knowing that another major function of SULT2A1 is to sulfonate and deactivate androgens, Lee et al. (37) went on to determine whether activation of LXR can deprive androgens through the activation of SULT2A1 gene expression. It was in this study that the authors uncovered a novel LXR-mediated mechanism of androgen deprivation. Lee et al. showed that activation of LXR in vivo lowered androgenic activity by inducing SULT2A1. Activation of LXR also inhibited the expression of STS in the prostate, which may have helped to prevent the local conversion of sulfonated androgens back to active metabolites. At the physiological level, activation of LXR inhibited androgen-dependent prostate regeneration. The retarded prostate regeneration was accompanied by a decrease in prostate epithelial proliferation and decreased circulating concentrations of androgens. The inhibitory effect of LXR agonists on androgen-dependent prostate regeneration was intact in EST/SULT1E1 knockout mice, suggesting that the androgen deprivation effect of LXR was independent of EST/SULT1E1. Treatment with LXR agonists inhibited androgen-dependent proliferation of human prostate cancer cells in an LXR- and SULT2A1-dependent manner. Moreover, forced expression of SULT2A1 was sufficient to deactivate androgens. Together, these results suggest that LXR may represent a novel therapeutic target for androgen deprivation and may aid in the treatment and prevention of hormone-dependent prostate cancer.

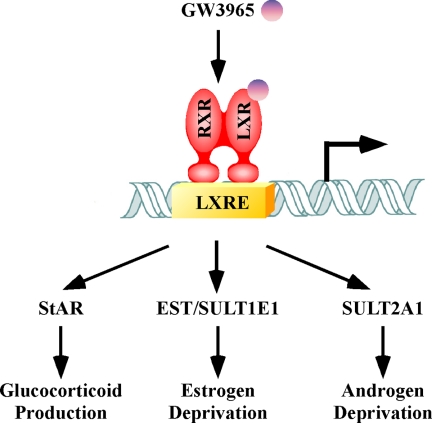

As summarized in Fig. 1, it is interesting to note that the previously known sterol sensor, LXR, has extensive roles in the homeostasis of multiple steroid hormones through the regulation of distinct target genes.

Figure 1.

The pleotropic effect of LXR on steroid hormone homeostasis. Activation of LXR, such as by the synthetic agonist GW3965, can impact the glucocorticoidogenesis and metabolic deprivation of estrogens and androgens. The pleotropic effect of LXR is likely mediated by the regulation of distinct target genes by this receptor. (RXR, retinoid X receptor; LXRE, LXR response element; EST/SULT1E1, sulfotransferase; SULT2A1, hydroxysteroid sulfotransferase).

Pregnane X Receptor (PXR) in Glucocorticoid, Mineralocorticoid, and Androgen Homeostasis

PXR in glucocorticoid and mineralocorticoid homeostasis

PXR has a well-established role as a xenobiotic receptor regulating the expression of drug-metabolizing enzymes and transporters, which is implicated in drug metabolism and drug-drug interactions (38,39,40). In addition to its effects on drug metabolism, PXR-mediated gene regulation has also been implicated in the homeostasis of numerous endogenous chemicals, including the steroid hormones (41,42). The endobiotic function of PXR is consistent with the notion that many of the PXR target drug-metabolizing enzymes and transporters are also responsible for the metabolism of endogenous chemicals.

Zhai et al. (42) showed that PXR played an important role in adrenal steroid homeostasis. Activation of PXR by genetic (transgene for an activated PXR) or pharmacological (PXR ligand) means markedly increased plasma concentrations of corticosterone and aldosterone, the respective primary glucocorticoid and mineralocorticoid in rodents. The increased levels of corticosterone and aldosterone were associated with activation of adrenal steroidogenic enzymes, including CYP11a1, CYP11b1, CYP11b2, and 3β-HSD. The PXR-activating transgenic mice also exhibited hypertrophy of the adrenal cortex, loss of glucocorticoid circadian rhythm, and lack of glucocorticoid response to psychogenic stress. In the PXR transgenic model, because neither the endogenous PXR nor the transgene is expressed in the adrenal gland, the adrenal steroidogenic effect of PXR is likely secondary to the PXR activation in the liver of the transgenic mice. Interestingly, the transgenic mice had normal pituitary secretion of ACTH, and the corticosterone-suppressing effect of dexamethasone (DEX) was intact, suggesting a functional hypothalamus-pituitary-adrenal axis despite a severe disruption of adrenal steroid homeostasis. The ACTH-independent hypercortisolism in transgenic mice is reminiscent of the pseudo-Cushing’s syndrome in patients. The glucocorticoid effect appeared to be PXR specific, because the activation of constitutive androstane receptor in transgenic mice had little effect. The effect of PXR on glucocorticoid output is also consistent with the clinical observation that rifampicin, a human (h)PXR agonist, increased urinary steroid secretion and may have led to the misdiagnosis of Cushing’s syndrome in some patients (43,44). The physiological implication of PXR-responsive changes in mineralocorticoid homeostasis remains to be established. Together, these results suggest that PXR is a potential endocrine-disrupting factor that may have broad implications in steroid homeostasis and drug-hormone interactions (42).

A potential role of PXR in androgen homeostasis

SULT2A1 is also a primary target gene of PXR (36). Having demonstrated that the LXR-mediated SULT2A1 gene activation is responsible for the androgen deprivation effect of LXR, it is reasonable to speculate that PXR may also have a role in regulating androgen homeostasis. The human CYP3A4 gene and its mouse homology CYP3A11 are also PXR target genes (45,46,47). A signature reaction catalyzed by CYP3A4/CYP3A11 is the 6β-hydroxylation of testosterone. It is believed that 6β-hydroxytestosterone is hormonally inactive (48). Therefore, the androgen deprivation effect of PXR, if it exists, likely results from the activation of both SULT2A1 and CYP3As by this receptor. It was recently reported that the human prostate cancer cells express functional PXR (49). It is tempting to speculate that activation of PXR in the liver and/or prostate may represent a new strategy with which to manage the local and/or systemic androgen activity.

Glucocorticoid Receptor (GR)-Mediated Estrogen Antagonism by Glucocorticoids

Glucocorticoids exert most of their functions by binding to GR. Upon ligand binding, GR is dissociated from heat shock protein hsp90 and translocated into the nucleus, where it activates gene expression by binding to glucocorticoid-responsive elements located in the target gene promoters (50,51,52).

Glucocorticoids have been shown to inhibit estrogen-stimulated uterine response (53,54). The synthetic glucocorticoid DEX blocked the growth-stimulatory effect of estrogen in MCF-7 cells (55). However, the mechanism by which glucocorticoids attenuate estrogen responses has remained elusive until recently. Gong and colleagues (56) showed that activation of GR by DEX induced the hepatic expression and activity of estrogen sulfotransferase EST/SULT1E1. EST/SULT1E1 induction by DEX was completely abolished in GR−/− mice. Interestingly, the DEX effect on EST/SULT1E1 expression appeared to be tissue specific, because DEX had little effect on EST/SULT1E1 expression in the testis, a tissue known to express GR. This is reminiscent of the tissue-specific regulation of EST/SULT1E1 by LXR (28). Treatment of female mice with DEX lowered circulating estrogens, compromised uterine estrogen responses, and inhibited estrogen-dependent breast cancer growth in vitro and in a MCF-7 xenograft model. The authors further demonstrated that the mouse and human EST/SULT1E1 genes are transcriptional targets of GR, and deletion of EST/SULT1E1 in mice abolished the DEX effect on estrogen responses. The DEX/GR-mediated EST/SULT1E1 induction was also consistent with the observation that the hypercorticosteronemia in db/db C57BL/KsJ mice was associated with a marked increase in EST/SULT1E1 gene expression in the liver (57). Together, these findings have revealed a novel GR-mediated and metabolism-based mechanism of estrogen deprivation, which may have implications in therapeutic development for breast cancers. Because glucocorticoids and estrogens are widely prescribed drugs, our results also urge caution in avoiding glucocorticoid-estrogen interactions in patients.

As discussed earlier, the expression of EST/SULT1E1 is also under the transcriptional control of LXR. The regulation of EST/SULT1E1 by GR and LXR in the mouse liver appeared to be independent from each other. Combined treatment with DEX and the LXR agonist T0901317 had an additive effect in activating EST/SULT1E1 gene expression. There are several notable differences between GR and LXR in their regulation of EST/SULT1E1. First, the DEX effect on EST/SULT1E1 expression can be seen in both the liver and MCF-7 cells whereas the LXR effect was limited to the liver (28). Second, the DEX effect can be seen in both mouse and human cells, including human hepatocytes and breast cancer cells whereas the LXR effect appeared to be mouse specific (28), reminiscent of the rodent-specific regulation of Cyp7a1 by LXR (58).

Vitamin D Receptor (VDR) in Estrogen Homeostasis

In addition to its classical role in calcium homeostasis, bone metabolism, and cell differentiation and proliferation, VDR has also been implicated in the regulation of estrogen biosyntheses (59). Several studies have shown that vitamin D can regulate the expression and activity of key enzymes involved in the biosynthesis of estrogens. Activation of VDR by 1α, 25(OH)2D3 up-regulated aromatase expression in human cell lines, whereas decreased expression of aromatase was associated with the loss of VDR in vivo (60,61,62). The expression and activity of STS and 17β-HSD were also induced in human cell lines after 1α, 25(OH)2D3 treatment (63). STS is a key enzyme in the biosynthesis of bioactive estrogens and androgens from the inactive sulfonated steroid precursors that are highly abundant in the circulation. 17β-HSD can convert estrone to the more potent estradiol. Thus, the STS/17β-HSD pathway provides an alternative pathway for the production of bioactive estrogens. Consistent with the notion that VDR-mediated nuclear signaling has a role in estrogen production, VDR−/− mice showed uterine hypoplasia, impaired folliculogenesis, and incomplete spermatogenesis, which can be reversed by exogenous estrogens (62,64).

Steroidogenic Factor 1 (SF-1) in Steroidogenesis

SF-1, highly expressed in steroidogenic tissues including adrenals and gonads, plays a key role in the regulation of adrenal and gonadal development, reproduction, and steroidogenesis (65). The expression of SF-1 has also been detected in the pituitary, ventromedial hypothalamus, skin, and spleen (66,67,68,69). SF-1 was initially identified as a transcriptional regulator of several steroidogenic P450 enzymes, including P450SCC, CYP11B1, CYP21, CYP17, and CYP19, by directly activating the promoters of these genes (70,71). SF-1 was later shown to regulate the transcription of genes encoding 3β-HSD, StAR, and SULT2A1 (72,73,74,75,76,77). 3β-HSD catalyzes the dehydrogenation and isomerization of Δ5–3β-hydroxysteroids, converting pregnenolone to progesterone. StAR plays a critical role in the movement of cholesterol from the outer to the inner mitochondrial membrane, which is a rate-limiting step in steroidogenesis from cholesterol. These studies together have implicated SF-1 in the production of essentially all steroids in the adrenal cortex and gonads (78).

Consistent with its broad and essential function in endocrine pathways, SF-1−/− mice exhibited remarkable endocrine phenotypes. The corticosterone concentration was reported to be very low, and the plasma level of ACTH was elevated in SF-1−/− mice. Indeed, acute deficiency of glucocorticoids and mineralocorticoids may have caused SF-1−/− mice to die by 8 d after birth, whereas injections of corticosteroid allowed SF-1−/− mice to survive longer (79,80). SF-1−/− mice also showed a complete lack of adrenals and gonads, as well as the male-to-female sex reversal of the internal and external genitalia (79,81). The SF-1 function appeared to be conserved in humans. At least three SF-1 mutations that were associated with abnormalities in adrenals and gonads have been reported in patients, including adrenal insufficiency or agenesis, and sex reversal (82,83,84).

Other NRs that May Impact Steroid Homeostasis

Farnesoid X receptor (FXR)

FXR was originally characterized as a bile acid receptor involved in the regulation of bile acids synthesis and cholesterol metabolism (85,86,87). More recently, FXR has been shown to play roles in lipid and carbohydrate homeostasis (88,89,90,91). FXR was initially shown to be highly expressed in the liver, kidney, and intestine. Several recent studies suggest that FXR is also expressed in human breast tissue and may play a role in the regulation of aromatase/CYP19, a key enzyme to produce estrogens from androgens (92). Aromatase inhibitors have been used successfully in clinic to manage hormone-dependent breast cancer. Swales et al. (93) reported that activation of FXR decreased aromatase gene expression and increased apoptosis in breast cancer MCF-7 and MDA-MB-468 cells, probably through a small heterodimer partner-mediated inhibition of liver receptor homolog-1 (LRH-1). These results suggest that FXR could function as a negative regulator of aromatase gene expression and may be explored as a therapeutic target for breast cancer. However, FXR activation was also shown to induce the proliferation of MCF-7 cells, which was thought be mediated by the FXR-ER interaction (94). Moreover, FXR expression was significantly correlated with the proliferation markers in postmenopausal patients with ER-positive breast tumors (95). The discrepancies between these two cell culture studies are yet to be understood.

FXR may also impact androgen homeostasis through the regulation of Phase II enzymes. It has been reported that activation of FXR inhibited the expression of androgen-glucuronidating UGT2B15 and UGT2B17 in human prostate cancer LNCaP cells (96), suggesting that FXR may help to maintain androgen activity by inhibiting glucuronidation-mediated deprivation. In contrast, the rodent SULT2A1 has been shown to be activated by FXR (97). As discussed earlier, SULT2A1 is the hydroxysteroid sulfotransferase that promotes androgen deprivation. The in vivo role of FXR in estrogen and androgen homeostasis remains to be established.

LRH-1

LRH-1 was initially found to express in the liver, pancreas, and intestine. LRH-1 plays an important role in the regulation of cholesterol metabolism and bile acid synthesis (98,99,100). More recently, LRH-1 was shown to express in the ovary and testis. LRH-1 has been suggested to play a role in steroid hormone biosynthesis through the regulation of aromatase/CYP19, an enzyme that catalyzes the biosynthesis of estrogens from androgens (101,102,103). Specifically, LRH-1 was found to be a preadipocyte-specific nuclear receptor that regulates aromatase gene expression in breast adipose tissue (104). LRH-1 bound to and activated the aromatase gene promoter II. Moreover, aromatase expression is high in breast cancers where LRH-1 is expressed (104). Therefore, LRH-1 could have a considerable effect on local estrogen production and breast cancer development by regulating aromatase. LRH-1 has also been shown to regulate the expression of 3β-HSD, which converts pregnenolone to progesterone in the corpus luteum (105). A severe ovarian phenotype associated with female infertility was observed in TATA box-binding protein -associated-factor II105 knockout mice, which was associated with an attenuated ovarian expression of LRH-1 (106). The use of conditional LRH-1 knockout mice may help to elucidate the function of this receptor in hormonal homeostasis, because of the embryonic lethality of the classical germline mutation (98).

Indeed, using intestinal epithelium-specific LRH-1 knockout mice, Coste et al. (107) recently showed that LRH-1 plays a role in local glucocorticoid synthesis in the intestine. The intestinal LRH-1 knockout mice exhibited more pronounced colonic inflammation than the wild-type mice when subjected to the 2,4,6-trinitrobenzene sulfonic acid model of inflammatory bowel disease. This aggravated colitis was associated with a lower level of corticosterone and decreased expression of glucocorticoid synthesis enzymes CYP11A1 and CYP11B1 in the colon. In a follow-up study, Atanasov et al. (108) reported that the regulation of glucocorticoid synthesis by LRH-1 appeared to be cell cycle specific. The expression of steroidogenic enzymes is preferentially induced in the G1/S stage. LRH-1 controls cell cycle progression in intestinal epithelial cells and thereby regulates the expression of CYP11A1 and CYP11B.

Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptors (PPARs)

The PPAR family is composed of three isotypes: α, β/δ, and γ (109,110). PPARα is known for its function in the regulation of lipid and fatty acid metabolism. PPARγ has an important role in adipogenesis and glucose homeostasis. PPARβ/δ plays diverse roles in cell differentiation and survival, and fatty acid metabolism. In addition to their roles in metabolic regulation, PPARs have also been implicated in endocrine functions. All three PPARs are expressed in the ovary and testis. PPARγ is also detected in the pituitary gland and hypothalamus (111,112,113). The synthetic PPARγ ligands thiazolidinediones (TZDs) can stimulate or inhibit the production of progesterone and estradiol in granulose cells, depending on the species and the status of the granulose cell differentiation (113,114,115). The endocrine action of TZDs may have resulted from their effect on the expression and/or activities of steroidogenic enzymes. Troglitazone, a TZD drug, has been reported to be a chemical inhibitor of 3β-HSD, causing a marked increase in pregnenolone secretion in porcine granulose cells (116). Troglitazone, especially together with the retinoid X receptor ligand LG100268, inhibited aromatase activity in human granulose cells (115,117). Among other potential impact of PPARs on hormonal homeostasis, PPARα has been shown to activate the expression of SULT2A1 (118). PPARα and -γ could interact with environmental endocrine disruptors, resulting in the inhibition of aromatase and decreased estradiol production in granulose cells (119). It is noted that the current knowledge on the endocrine function of PPARs is mostly derived from cell culture studies; the in vivo significance of PPARs in hormonal homeostasis remains to be established.

Estrogen-related receptors (ERRs)

ERRs, including α-, β-, and γ-isoforms, are closely related to the ERs. Because ERRs share certain target genes, coregulatory proteins, ligands, and sites of action with ERs, it was proposed that ERRs may influence the estrogenic responses (120). More recently, it has been reported that the expression of androgen-responsive genes can be down-regulated by the ERRα-specific inverse agonist in prostate LNCaP cells. In contrast, overexpression of ERRα stimulated the activity of androgen-responsive elements and other steroid-response elements-containing promoters, suggesting that ERRs may also interfere with the signaling of steroids other than the estrogens (121). Among other potential impacts of ERRs on hormonal homeostasis, ERRα has been reported to activate SULT2A1 gene expression in the adrenal gland (122) and regulate the expression of aromatase (123). More recently, ERRα and hepatocyte nuclear factor-4α were shown to be required for PPAR coactivator-1α-mediated induction of CYP17A1, a rate-limiting enzyme for the conversion of cholesterol to pregnenolone (124).

Conclusions

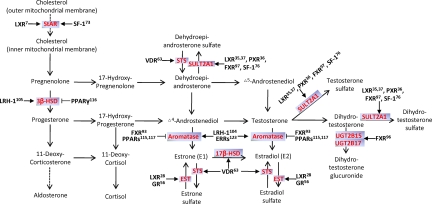

Steroid hormones are broadly implicated in metabolism, growth and maturation, sexuality and reproduction, and other important bodily functions. In addition to their physiological function, steroid hormones also play a crucial role in many pathological processes, including endocrine, cancerous, and metabolic diseases. As summarized in Fig. 2, it has become clear that NRs actively and extensively participate in the regulation of biosynthesis and metabolism of steroid hormones. It should be cautioned that in some cases, although the animal results are convincing, the human relevance of the regulation remains to be determined. Nevertheless, the emerging roles of NRs in the transcriptional regulation of hormonal homeostasis have significantly expanded the physiological and pathophysiological functions of NRs. Although functional agonists or antagonists for some of these NRs remain to be identified or developed, NRs represent excellent pharmacological targets to achieve endocrine benefits and/or to correct endocrine disorders in patients.

Figure 2.

The steroidogenic and hormone-metabolizing pathways and NRs implicated in hormonal homeostasis. The steroidogenic and hormone-metabolizing enzymes are highlighted in red. → and ⊣, Positive and gene-negative regulation, respectively. The reference numbers are labeled.

Footnotes

Our original research described in this article was supported in part by National Institutes of Health Grants ES012479, ES014626, and DK076962.

Disclosure Summary: The authors have nothing to disclose.

First Published Online September 17, 2009

Abbreviations: CYP, Cytochrome P450; DEX, dexamethasone; ER, estrogen receptor; ERR, estrogen-related receptor; EST, estrogen sulfotransferase; FXR, farnesoid X receptor; GR, glucocorticoid receptor; HSD, hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase; LRH-1, liver receptor homolog-1; LXR, liver X receptor; NR, nuclear receptor; POMC, proopiomelanocortin; PPAR, peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor; PXR, pregnane X receptor; SF-1, steroidogenic factor 1; StAR, steroidogenic acute regulatory protein; STS, steroid sulfatase; SULT, sulfotransferase; TZD, thiazolidinedione; VDR, vitamin D receptor.

References

- Mangelsdorf DJ, Thummel C, Beato M, Herrlich P, Schütz G, Umesono K, Blumberg B, Kastner P, Mark M, Chambon P, Evans RM 1995 The nuclear receptor superfamily: the second decade. Cell 83:835–839 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O'Malley B 1990 The steroid receptor superfamily: more excitement predicted for the future. Mol Endocrinol 4:363–369 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Umesono K, Murakami KK, Thompson CC, Evans RM 1991 Direct repeats as selective response elements for the thyroid hormone, retinoic acid, and vitamin D3 receptors. Cell 65:1255–1266 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evans RM 2005 The nuclear receptor superfamily: a rosetta stone for physiology. Mol Endocrinol 19:1429–1438 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aguilera G, Rabadan-Diehl C, Nikodemova M 2001 Regulation of pituitary corticotropin releasing hormone receptors. Peptides 22:769–774 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Christenson LK, Strauss 3rd JF 2000 Steroidogenic acute regulatory protein (StAR) and the intramitochondrial translocation of cholesterol. Biochim Biophys Acta 1529:175–187 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cummins CL, Volle DH, Zhang Y, McDonald JG, Sion B, Lefrançcois-Martinez AM, Caira F, Veyssière G, Mangelsdorf DJ, Lobaccaro JM 2006 Liver X receptors regulate adrenal cholesterol balance. J Clin Invest 116:1902–1912 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burstein S, Gut M 1976 Intermediates in the conversion of cholesterol to pregnenolone: kinetics and mechanism. Steroids 28:115–131 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Janowski BA, Willy PJ, Devi TR, Falck JR, Mangelsdorf DJ 1996 An oxysterol signalling pathway mediated by the nuclear receptor LXR α. Nature 383:728–731 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kennedy MA, Venkateswaran A, Tarr PT, Xenarios I, Kudoh J, Shimizu N, Edwards PA 2001 Characterization of the human ABCG1 gene: liver X receptor activates an internal promoter that produces a novel transcript encoding an alternative form of the protein. J Biol Chem 276:39438–39447 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Costet P, Luo Y, Wang N, Tall AR 2000 Sterol-dependent transactivation of the ABC1 promoter by the liver X receptor/retinoid X receptor. J Biol Chem 275:28240–28245 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Repa JJ, Berge KE, Pomajzl C, Richardson JA, Hobbs H, Mangelsdorf DJ 2002 Regulation of ATP-binding cassette sterol transporters ABCG5 and ABCG8 by the liver X receptors α and β. J Biol Chem 277:18793–18800 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peet DJ, Turley SD, Ma W, Janowski BA, Lobaccaro JM, Hammer RE, Mangelsdorf DJ 1998 Cholesterol and bile acid metabolism are impaired in mice lacking the nuclear oxysterol receptor LXR α. Cell 93:693–704 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Repa JJ, Mangelsdorf DJ 2000 The role of orphan nuclear receptors in the regulation of cholesterol homeostasis. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol 16:459–481 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steffensen KR, Neo SY, Stulnig TM, Vega VB, Rahman SS, Schuster GU, Gustafsson JA, Liu ET 2004 Genome-wide expression profiling; a panel of mouse tissues discloses novel biological functions of liver X receptors in adrenals. J Mol Endocrinol 33:609–622 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsumoto S, Hashimoto K, Yamada M, Satoh T, Hirato J, Mori M 2009 Liver X receptor-α regulates proopiomelanocortin (POMC) gene transcription in the pituitary. Mol Endocrinol 23:47–60 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stulnig TM, Oppermann U, Steffensen KR, Schuster GU, Gustafsson JA 2002 Liver X receptors downregulate 11β-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase type 1 expression and activity. Diabetes 51:2426–2433 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nilsson M, Stulnig TM, Lin CY, Yeo AL, Nowotny P, Liu ET, Steffensen KR 2007 Liver X receptors regulate adrenal steroidogenesis and hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal feedback. Mol Endocrinol 21:126–137 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jefcoate CR 2006 Liver X receptor opens a new gateway to StAR and to steroid hormones. J Clin Invest 116:1832–1835 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harris HJ, Kotelevtsev Y, Mullins JJ, Seckl JR, Holmes MC 2001 Intracellular regeneration of glucocorticoids by 11β-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase (11β-HSD)-1 plays a key role in regulation of the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis: analysis of 11β-HSD-1-deficient mice. Endocrinology 142:114–120 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Macedo LF, Sabnis G, Brodie A 2009 Aromatase inhibitors and breast cancer. Ann NY Acad Sci 1155:162–173 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Townsley JD, Rubin EJ, Crystle CD 1973 Evaluation of placental steroid 3-sulfatase and aromatase activities as regulators of estrogen production in human pregnancy. Am J Obstet Gynecol 117:345–350 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yager JD, Davidson NE 2006 Estrogen carcinogenesis in breast cancer. N Engl J Med 354:270–282 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nilsson S, Gustafsson JA 2002 Biological role of estrogen and estrogen receptors. Crit Rev Biochem Mol Biol 37:1–28 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pasqualini JR 2009 Estrogen sulfotransferases in breast and endometrial cancers. Ann NY Acad Sci 1155:88–98 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Song WC 2001 Biochemistry and reproductive endocrinology of estrogen sulfotransferase. Ann NY Acad Sci 948:43–50 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kakuta Y, Pedersen LC, Chae K, Song WC, Leblanc D, London R, Carter CW, Negishi M 1998 Mouse steroid sulfotransferases: substrate specificity and preliminary X-ray crystallographic analysis. Biochem Pharmacol 55:313–317 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gong H, Guo P, Zhai Y, Zhou J, Uppal H, Jarzynka MJ, Song WC, Cheng SY, Xie W 2007 Estrogen deprivation and inhibition of breast cancer growth in vivo through activation of the orphan nuclear receptor liver X receptor. Mol Endocrinol 21:1781–1790 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kempenaers B, Peters A, Foerster K 2008 Sources of individual variation in plasma testosterone levels. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci 363:1711–1723 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chatterjee B 2003 The role of the androgen receptor in the development of prostatic hyperplasia and prostate cancer. Mol Cell Biochem 253:89–101 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu YS, Imperato-McGinley JL 2009 5α-Reductase isozymes and androgen actions in the prostate. Ann NY Acad Sci 1155:43–56 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strott CA 2002 Sulfonation and molecular action. Endocr Rev 23:703–732 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meloche CA, Sharma V, Swedmark S, Andersson P, Falany CN 2002 Sulfation of budesonide by human cytosolic sulfotransferase, dehydroepiandrosterone-sulfotransferase (DHEA-ST). Drug Metab Dispos 30:582–585 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reed MJ, Purohit A, Woo LW, Newman SP, Potter BV 2005 Steroid sulfatase: molecular biology, regulation, and inhibition. Endocr Rev 26:171–202 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uppal H, Saini SP, Moschetta A, Mu Y, Zhou J, Gong H, Zhai Y, Ren S, Michalopoulos GK, Mangelsdorf DJ, Xie W 2007 Activation of LXRs prevents bile acid toxicity and cholestasis in female mice. Hepatology 45:422–432 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sonoda J, Xie W, Rosenfeld JM, Barwick JL, Guzelian PS, Evans RM 2002 Regulation of a xenobiotic sulfonation cascade by nuclear pregnane X receptor (PXR). Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 99:13801–13806 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee JH, Gong H, Khadem S, Lu Y, Gao X, Li S, Zhang J, Xie W 2008 Androgen deprivation by activating the liver X receptor. Endocrinology 149:3778–3788 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang B, Xie W, Krasowski MD 2008 PXR: a xenobiotic receptor of diverse function implicated in pharmacogenetics. Pharmacogenomics 9:1695–1709 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xie W, Uppal H, Saini SP, Mu Y, Little JM, Radominska-Pandya A, Zemaitis MA 2004 Orphan nuclear receptor-mediated xenobiotic regulation in drug metabolism. Drug Discov Today 9:442–449 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kliewer SA, Goodwin B, Willson TM 2002 The nuclear pregnane X receptor: a key regulator of xenobiotic metabolism. Endocr Rev 23:687–702 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xie W, Yeuh MF, Radominska-Pandya A, Saini SP, Negishi Y, Bottroff BS, Cabrera GY, Tukey RH, Evans RM 2003 Control of steroid, heme, and carcinogen metabolism by nuclear pregnane X receptor and constitutive androstane receptor. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 100:4150–4155 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhai Y, Pai HV, Zhou J, Amico JA, Vollmer RR, Xie W 2007 Activation of pregnane X receptor disrupts glucocorticoid and mineralocorticoid homeostasis. Mol Endocrinol 21:138–147 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Terzolo M, Borretta G, Alì A, Cesario F, Magro G, Boccuzzi A, Reimondo G, Angeli A 1995 Misdiagnosis of Cushing’s syndrome in a patient receiving rifampicin therapy for tuberculosis. Horm Metab Res 27:148–150 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zawawi TH, al-Hadramy MS, Abdelwahab SM 1996 The effects of therapy with rifampicin and isoniazid on basic investigations for Cushing’s syndrome. Ir J Med Sci 165:300–302 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xie W, Barwick JL, Downes M, Blumberg B, Simon CM, Nelson MC, Neuschwander-Tetri BA, Brunt EM, Guzelian PS, Evans RM 2000 Humanized xenobiotic response in mice expressing nuclear receptor SXR. Nature 406:435–439 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kliewer SA, Moore JT, Wade L, Staudinger JL, Watson MA, Jones SA, McKee DD, Oliver BB, Willson TM, Zetterström RH, Perlmann T, Lehmann JM 1998 An orphan nuclear receptor activated by pregnanes defines a novel steroid signaling pathway. Cell 92:73–82 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blumberg B, Sabbagh Jr W, Juguilon H, Bolado Jr J, van Meter CM, Ong ES, Evans RM 1998 SXR, a novel steroid and xenobiotic-sensing nuclear receptor. Genes Dev 12:3195–3205 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keshava C, McCanlies EC, Weston A 2004 CYP3A4 polymorphisms—potential risk factors for breast and prostate cancer: a HuGE review. Am J Epidemiol 160:825–841 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen Y, Tang Y, Wang MT, Zeng S, Nie D 2007 Human pregnane X receptor and resistance to chemotherapy in prostate cancer. Cancer Res 67:10361–10367 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dahlman-Wright K, Siltala-Roos H, Carlstedt-Duke J, Gustafsson JA 1990 Protein-protein interactions facilitate DNA binding by the glucocorticoid receptor DNA-binding domain. J Biol Chem 265:14030–14035 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oakley RH, Webster JC, Jewell CM, Sar M, Cidlowski JA 1999 Immunocytochemical analysis of the glucocorticoid receptor α isoform (GRα) using GRα-specific antibody. Steroids 64:742–751 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang JC, Derynck MK, Nonaka DF, Khodabakhsh DB, Haqq C, Yamamoto KR 2004 Chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP) scanning identifies primary glucocorticoid receptor target genes. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 101:15603–15608 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bitman J, Cecil HC 1967 Differential inhibition by cortisol of estrogen-stimulated uterine responses. Endocrinology 80:423–429 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bever AT, Hisaw FL, Velardo JT 1956 Inhibitory action of desoxycorticosterone acetate, cortisone acetate, and testosterone on uterine growth induced by estradiol-17β. Endocrinology 59:165–169 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou F, Bouillard B, Pharaboz-Joly MO, André J 1989 Non-classical antiestrogenic actions of dexamethasone in variant MCF-7 human breast cancer cells in culture. Mol Cell Endocrinol 66:189–197 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gong H, Jarzynka MJ, Cole TJ, Lee JH, Wada T, Zhang B, Gao J, Song WC, DeFranco DB, Cheng SY, Xie W 2008 Glucocorticoids antagonize estrogens by glucocorticoid receptor-mediated activation of estrogen sulfotransferase. Cancer Res 68:7386–7393 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leiter EH, Chapman HD 1994 Obesity-induced diabetes (diabesity) in C57BL/KsJ mice produces aberrant trans-regulation of sex steroid sulfotransferase genes. J Clin Invest 93:2007–2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chiang JY, Kimmel R, Stroup D 2001 Regulation of cholesterol 7α-hydroxylase gene (CYP7A1) transcription by the liver orphan receptor (LXRα). Gene 262:257–265 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bouillon R, Okamura WH, Norman AW 1995 Structure-function relationships in the vitamin D endocrine system. Endocr Rev 16:200–257 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Enjuanes A, Garcia-Giralt N, Supervia A, Nogués X, Mellibovsky L, Carbonell J, Grinberg D, Balcells S, Diez-Pérez A 2003 Regulation of CYP19 gene expression in primary human osteoblasts: effects of vitamin D and other treatments. Eur J Endocrinol 148:519–526 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jakob F, Homann D, Adamski J 1995 Expression and regulation of aromatase and 17β-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase type 4 in human THP 1 leukemia cells. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol 55:555–563 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kinuta K, Tanaka H, Moriwake T, Aya K, Kato S, Seino Y 2000 Vitamin D is an important factor in estrogen biosynthesis of both female and male gonads. Endocrinology 141:1317–1324 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hughes PJ, Twist LE, Durham J, Choudhry MA, Drayson M, Chandraratna R, Michell RH, Kirk CJ, Brown G 2001 Up-regulation of steroid sulphatase activity in HL60 promyelocytic cells by retinoids and 1α,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3. Biochem J 355:361–371 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoshizawa T, Handa Y, Uematsu Y, Takeda S, Sekine K, Yoshihara Y, Kawakami T, Arioka K, Sato H, Uchiyama Y, Masushige S, Fukamizu A, Matsumoto T, Kato S 1997 Mice lacking the vitamin D receptor exhibit impaired bone formation, uterine hypoplasia and growth retardation after weaning. Nat Genet 16:391–396 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramayya MS, Zhou J, Kino T, Segars JH, Bondy CA, Chrousos GP 1997 Steroidogenic factor 1 messenger ribonucleic acid expression in steroidogenic and nonsteroidogenic human tissues: Northern blot and in situ hybridization studies. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 82:1799–1806 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ingraham HA, Lala DS, Ikeda Y, Luo X, Shen WH, Nachtigal MW, Abbud R, Nilson JH, Parker KL 1994 The nuclear receptor steroidogenic factor 1 acts at multiple levels of the reproductive axis. Genes Dev 8:2302–2312 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morohashi K, Tsuboi-Asai H, Matsushita S, Suda M, Nakashima M, Sasano H, Hataba Y, Li CL, Fukata J, Irie J, Watanabe T, Nagura H, Li E 1999 Structural and functional abnormalities in the spleen of an mFtz-F1 gene-disrupted mouse. Blood 93:1586–1594 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patel MV, McKay IA, Burrin JM 2001 Transcriptional regulators of steroidogenesis, DAX-1 and SF-1, are expressed in human skin. J Invest Dermatol 117:1559–1565 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shinoda K, Lei H, Yoshii H, Nomura M, Nagano M, Shiba H, Sasaki H, Osawa Y, Ninomiya Y, Niwa O, Morohashi KI, Li E 1995 Developmental defects of the ventromedial hypothalamic nucleus and pituitary gonadotroph in the Ftz-F1 disrupted mice. Dev Dyn 204:22–29 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rice DA, Mouw AR, Bogerd AM, Parker KL 1991 A shared promoter element regulates the expression of three steroidogenic enzymes. Mol Endocrinol 5:1552–1561 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morohashi K, Honda S, Inomata Y, Handa H, Omura T 1992 A common trans-acting factor, Ad4-binding protein, to the promoters of steroidogenic P-450s. J Biol Chem 267:17913–17919 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leers-Sucheta S, Morohashi K, Mason JI, Melner MH 1997 Synergistic activation of the human type II 3β-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase/δ5-δ4 isomerase promoter by the transcription factor steroidogenic factor-1/adrenal 4-binding protein and phorbol ester. J Biol Chem 272:7960–7967 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sugawara T, Kiriakidou M, McAllister JM, Holt JA, Arakane F, Strauss III JF 1997 Regulation of expression of the steroidogenic acute regulatory protein (StAR) gene: a central role for steroidogenic factor 1. Steroids 62:5–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parker KL, Rice DA, Lala DS, Ikeda Y, Luo X, Wong M, Bakke M, Zhao L, Frigeri C, Hanley NA, Stallings N, Schimmer BP 2002 Steroidogenic factor 1: an essential mediator of endocrine development. Recent Prog Horm Res 57:19–36 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parker KL, Schimmer BP 1997 Steroidogenic factor 1: a key determinant of endocrine development and function. Endocr Rev 18:361–377 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saner KJ, Suzuki T, Sasano H, Pizzey J, Ho C, Strauss 3rd JF, Carr BR, Rainey WE 2005 Steroid sulfotransferase 2A1 gene transcription is regulated by steroidogenic factor 1 and GATA-6 in the human adrenal. Mol Endocrinol 19:184–197 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sugawara T, Holt JA, Kiriakidou M, Strauss III JF 1996 Steroidogenic factor 1-dependent promoter activity of the human steroidogenic acute regulatory protein (StAR) gene. Biochemistry 35:9052–9059 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Val P, Lefrançcois-Martinez AM, Veyssière G, Martinez A 2003 SF-1 a key player in the development and differentiation of steroidogenic tissues. Nucl Recept 1:8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luo X, Ikeda Y, Parker KL 1994 A cell-specific nuclear receptor is essential for adrenal and gonadal development and sexual differentiation. Cell 77:481–490 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luo X, Ikeda Y, Schlosser DA, Parker KL 1995 Steroidogenic factor 1 is the essential transcript of the mouse Ftz-F1 gene. Mol Endocrinol 9:1233–1239 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sadovsky Y, Crawford PA, Woodson KG, Polish JA, Clements MA, Tourtellotte LM, Simburger K, Milbrandt J 1995 Mice deficient in the orphan receptor steroidogenic factor 1 lack adrenal glands and gonads but express P450 side-chain-cleavage enzyme in the placenta and have normal embryonic serum levels of corticosteroids. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 92:10939–10943 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Achermann JC, Ito M, Ito M, Hindmarsh PC, Jameson JL 1999 A mutation in the gene encoding steroidogenic factor-1 causes XY sex reversal and adrenal failure in humans. Nat Genet 22:125–126 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Achermann JC, Ozisik G, Ito M, Orun UA, Harmanci K, Gurakan B, Jameson JL 2002 Gonadal determination and adrenal development are regulated by the orphan nuclear receptor steroidogenic factor-1, in a dose-dependent manner. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 87:1829–1833 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Biason-Lauber A, Schoenle EJ 2000 Apparently normal ovarian differentiation in a prepubertal girl with transcriptionally inactive steroidogenic factor 1 (NR5A1/SF-1) and adrenocortical insufficiency. Am J Hum Genet 67:1563–1568 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Makishima M, Okamoto AY, Repa JJ, Tu H, Learned RM, Luk A, Hull MV, Lustig KD, Mangelsdorf DJ, Shan B 1999 Identification of a nuclear receptor for bile acids. Science 284:1362–1365 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parks DJ, Blanchard SG, Bledsoe RK, Chandra G, Consler TG, Kliewer SA, Stimmel JB, Willson TM, Zavacki AM, Moore DD, Lehmann JM 1999 Bile acids: natural ligands for an orphan nuclear receptor. Science 284:1365–1368 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang H, Chen J, Hollister K, Sowers LC, Forman BM 1999 Endogenous bile acids are ligands for the nuclear receptor FXR/BAR. Mol Cell 3:543–553 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duran-Sandoval D, Cariou B, Percevault F, Hennuyer N, Grefhorst A, van Dijk TH, Gonzalez FJ, Fruchart JC, Kuipers F, Staels B 2005 The farnesoid X receptor modulates hepatic carbohydrate metabolism during the fasting-refeeding transition. J Biol Chem 280:29971–29979 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma K, Saha PK, Chan L, Moore DD 2006 Farnesoid X receptor is essential for normal glucose homeostasis. J Clin Invest 116:1102–1109 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stayrook KR, Bramlett KS, Savkur RS, Ficorilli J, Cook T, Christe ME, Michael LF, Burris TP 2005 Regulation of carbohydrate metabolism by the farnesoid X receptor. Endocrinology 146:984–991 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Y, Lee FY, Barrera G, Lee H, Vales C, Gonzalez FJ, Willson TM, Edwards PA 2006 Activation of the nuclear receptor FXR improves hyperglycemia and hyperlipidemia in diabetic mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 103:1006–1011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fisher CR, Graves KH, Parlow AF, Simpson ER 1998 Characterization of mice deficient in aromatase (ArKO) because of targeted disruption of the cyp19 gene. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 95:6965–6970 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swales KE, Korbonits M, Carpenter R, Walsh DT, Warner TD, Bishop-Bailey D 2006 The farnesoid X receptor is expressed in breast cancer and regulates apoptosis and aromatase expression. Cancer Res 66:10120–10126 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Journe F, Laurent G, Chaboteaux C, Nonclercq D, Durbecq V, Larsimont D, Body JJ 2008 Farnesol, a mevalonate pathway intermediate, stimulates MCF-7 breast cancer cell growth through farnesoid-X-receptor-mediated estrogen receptor activation. Breast Cancer Res Treat 107:49–61 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Journe F, Durbecq V, Chaboteaux C, Rouas G, Laurent G, Nonclercq D, Sotiriou C, Body JJ, Larsimont D 2009 Association between farnesoid X receptor expression and cell proliferation in estrogen receptor-positive luminal-like breast cancer from postmenopausal patients. Breast Cancer Res Treat 115:523–535 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaeding J, Bouchaert E, Bélanger J, Caron P, Chouinard S, Verreault M, Larouche O, Pelletier G, Staels B, Bélanger A, Barbier O 2008 Activators of the farnesoid X receptor negatively regulate androgen glucuronidation in human prostate cancer LNCAP cells. Biochem J 410:245–253 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Song CS, Echchgadda I, Baek BS, Ahn SC, Oh T, Roy AK, Chatterjee B 2001 Dehydroepiandrosterone sulfotransferase gene induction by bile acid activated farnesoid X receptor. J Biol Chem 276:42549–42556 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fayard E, Auwerx J, Schoonjans K 2004 LRH-1: an orphan nuclear receptor involved in development, metabolism and steroidogenesis. Trends Cell Biol 14:250–260 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu TT, Makishima M, Repa JJ, Schoonjans K, Kerr TA, Auwerx J, Mangelsdorf DJ 2000 Molecular basis for feedback regulation of bile acid synthesis by nuclear receptors. Mol Cell 6:507–515 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu TT, Repa JJ, Mangelsdorf DJ 2001 Orphan nuclear receptors as eLiXiRs and FiXeRs of sterol metabolism. J Biol Chem 276:37735–37738 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hinshelwood MM, Repa JJ, Shelton JM, Richardson JA, Mangelsdorf DJ, Mendelson CR 2003 Expression of LRH-1 and SF-1 in the mouse ovary: localization in different cell types correlates with differing function. Mol Cell Endocrinol 207:39–45 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu DL, Liu WZ, Li QL, Wang HM, Qian D, Treuter E, Zhu C 2003 Expression and functional analysis of liver receptor homologue 1 as a potential steroidogenic factor in rat ovary. Biol Reprod 69:508–517 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pezzi V, Sirianni R, Chimento A, Maggiolini M, Bourguiba S, Delalande C, Carreau S, Andò S, Simpson ER, Clyne CD 2004 Differential expression of steroidogenic factor-1/adrenal 4 binding protein and liver receptor homolog-1 (LRH-1)/fetoprotein transcription factor in the rat testis: LRH-1 as a potential regulator of testicular aromatase expression. Endocrinology 145:2186–2196 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clyne CD, Speed CJ, Zhou J, Simpson ER 2002 Liver receptor homologue-1 (LRH-1) regulates expression of aromatase in preadipocytes. J Biol Chem 277:20591–20597 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peng N, Kim JW, Rainey WE, Carr BR, Attia GR 2003 The role of the orphan nuclear receptor, liver receptor homologue-1, in the regulation of human corpus luteum 3β-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase type II. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 88:6020–6028 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freiman RN, Albright SR, Zheng S, Sha WC, Hammer RE, Tjian R 2001 Requirement of tissue-selective TBP-associated factor TAFII105 in ovarian development. Science 293:2084–2087 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coste A, Dubuquoy L, Barnouin R, Annicotte JS, Magnier B, Notti M, Corazza N, Antal MC, Metzger D, Desreumaux P, Brunner T, Auwerx J, Schoonjans K 2007 LRH-1-mediated glucocorticoid synthesis in enterocytes protects against inflammatory bowel disease. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 104:13098–13103 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Atanasov AG, Leiser D, Roesselet C, Noti M, Corazza N, Schoonjans K, Brunner T 2008 Cell cycle-dependent regulation of extra-adrenal glucocorticoid synthesis in murine intestinal epithelial cells. FASEB J 22:4117–4125 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee CH, Olson P, Evans RM 2003 Minireview: lipid metabolism, metabolic diseases, and peroxisome proliferator-activated receptors. Endocrinology 144:2201–2207 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee CH, Evans RM 2002 Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-γ in macrophage lipid homeostasis. Trends Endocrinol Metab 13:331–335 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Froment P, Gizard F, Defever D, Staels B, Dupont J, Monget P 2006 Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptors in reproductive tissues: from gametogenesis to parturition. J Endocrinol 189:199–209 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heaney AP, Fernando M, Melmed S 2003 PPAR-γ receptor ligands: novel therapy for pituitary adenomas. J Clin Invest 111:1381–1388 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Komar CM, Braissant O, Wahli W, Curry Jr TE 2001 Expression and localization of PPARs in the rat ovary during follicular development and the periovulatory period. Endocrinology 142:4831–4838 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gasic S, Bodenburg Y, Nagamani M, Green A, Urban RJ 1998 Troglitazone inhibits progesterone production in porcine granulosa cells. Endocrinology 139:4962–4966 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mu YM, Yanase T, Nishi Y, Waseda N, Oda T, Tanaka A, Takayanagi R, Nawata H 2000 Insulin sensitizer, troglitazone, directly inhibits aromatase activity in human ovarian granulosa cells. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 271:710–713 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gasic S, Nagamani M, Green A, Urban RJ 2001 Troglitazone is a competitive inhibitor of 3beta-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase enzyme in the ovary. Am J Obstet Gynecol 184:575–579 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fan W, Yanase T, Morinaga H, Mu YM, Nomura M, Okabe T, Goto K, Harada N, Nawata H 2005 Activation of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-γ and retinoid X receptor inhibits aromatase transcription via nuclear factor-κB. Endocrinology 146:85–92 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fang HL, Strom SC, Cai H, Falany CN, Kocarek TA, Runge-Morris M 2005 Regulation of human hepatic hydroxysteroid sulfotransferase gene expression by the peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor α transcription factor. Mol Pharmacol 67:1257–1267 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lovekamp-Swan T, Jetten AM, Davis BJ 2003 Dual activation of PPARα and PPARγ by mono-(2-ethylhexyl) phthalate in rat ovarian granulosa cells. Mol Cell Endocrinol 201:133–141 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giguère V 2002 To ERR in the estrogen pathway. Trends Endocrinol Metab 13:220–225 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Teyssier C, Bianco S, Lanvin O, Vanacker JM 2008 The orphan receptor ERRα interferes with steroid signaling. Nucleic Acids Res 36:5350–5361 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seely J, Amigh KS, Suzuki T, Mayhew B, Sasano H, Giguere V, Laganière J, Carr BR, Rainey WE 2005 Transcriptional regulation of dehydroepiandrosterone sulfotransferase (SULT2A1) by estrogen-related receptor α. Endocrinology 146:3605–3613 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang C, Zhou D, Chen S 1998 Modulation of aromatase expression in the breast tissue by ERR α-1 orphan receptor. Cancer Res 58:5695–5700 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grasfeder LL, Gaillard S, Hammes SR, Ilkayeva O, Newgard CB, Hochberg RB, Dwyer MA, Chang CY, McDonnell DP 2009 Fasting-induced hepatic production of DHEA is regulated by PGC-1α, ERRα, and HNF4α. Mol Endocrinol 23:1171–1182 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]