Abstract

We hypothesized that cells bearing a single inherited “hit” in a tumor suppressor gene express an altered mRNA repertoire that may identify targets for measures that could delay or even prevent progression to carcinoma. We report here on the transcriptomes of primary breast and ovarian epithelial cells cultured from BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutation-carriers and controls. Our comparison analyses identified multiple changes in gene expression, in both tissues for both mutations, that were validated independently validated by real-time RT-PCR analysis. Several of the differentially expressed genes had been previously proposed as cancer markers, including mammaglobin in breast cancer and serum amyloid in ovarian cancer. These findings demonstrate that heterozygosity for a mutant tumor suppressor gene can alter the expression profiles of phenotypically normal epithelial cells in a gene-specific manner; these detectable effects of “one-hit” represent early molecular changes in tumorigenesis that may serve as novel biomarkers of cancer risk and as targets for chemoprevention.

Keywords: Breast cancer, Gynecological cancers: ovarian, BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutation, Tumor suppressor gene, Single-hit mutation, Transcriptome, Biomarkers

Introduction

The notion of multistep carcinogenesis posits that rate-limiting mutations accumulate in a single cell and its progeny, marking recognizable histopathological transitions in the target tissues (1, 2). The time required for this accumulation affords the opportunity to test whether pharmacological and/or dietary interventions can delay or prevent the transition to malignancy (3). Early targeted intervention would be optimally performed on persons with a very high risk of developing a specific cancer, as with those individuals who carry a germline mutation in a gene known to impose such a risk. Rationale for such an intervention is provided by early studies that demonstrated that cells heterozygous for a cancer-predisposing mutation could show abnormalities in tissue cultures; “one-hit” effects in heterozygous cells were seen in morphologically normal cultured fibroblasts and in epithelial cells derived from Familial Adenomatous Polyposis (FAP) patients (4-6). Furthermore, we have recently reported specific changes in protein expression in colonic epithelial cells from FAP patients (7). Support for the significance of these early changes comes from observations of similar aberrations in corresponding cancer cells, (7, 8, 9). Such changes may play a role in progression to malignancy and therefore constitute targets for strategies to delay or prevent such progression in FAP and in other genetic predispositions to cancer.

With this rationale in mind we have undertaken an investigation of two of the most common predisposing genes, BRCA1 (10, 11) and BRCA2 (12, 13, and references therein) in two important target tissues, breast and ovary. We note that previous reports on benign cells associated with breast cancer already suggest the possibility of such heterozygous effects.

We have compared the transcriptomes of primary breast and ovarian epithelial cultures from patients predisposed to cancer, bearing monoallelic BRCA1 or BRCA2 mutations, with corresponding cultures from control individuals. We demonstrate that the morphologically normal epithelial cells from mutation carriers exhibit abnormalities in a gene-specific and tissue-specific manner, consistent with detectable single-hit effects. These alterations constitute possible molecular targets for intervention on the path to cancer.

Materials and Methods

Subject accrual and biopsy specimens

All subjects were recruited with the approval of the FCCC Institutional Review Board, irrespective of gender, race and age. Individuals with a personal history of cancer and subjects treated previously with either chemotherapy or radiation were ineligible. Eligible cases included unaffected at-risk women in the Fox Chase Family Risk Assessment Program who were shown to be carriers of BRCA1 or BRCA2 mutations. In particular, six BRCA1, six BRCA2 mutation carriers, and six healthy controls were accrued for breast specimens and an equal number for ovary specimens. Normal breast and ovary specimens were obtained by prophylactic oophorectomy or mastectomy or breast reduction surgery.

Cell culture establishment

Surgical breast specimens were placed in transport medium (serum-free Ham's F-12), containing 100 U/ml penicillin, 100 μg/ml of streptomycin, 10 μg/ml ciprofloxacin, 10 μg/ml gentamicin, 2.5 μg/ml of Amphotericin B and 100 U/ml of Nystatin. The tissue was finely minced using sterile disposable scalpels and transferred to a tube containing 25 ml of 200 U/ml solution of collagenase (Sigma) prepared in DMEM with 2 g/l of NaHCO3, supplemented with 160 U/ml of Hyaluronidase, 0.5 μg/ml hydrocortisone, 10 μg/ml insulin, 10 ml of Antibiotic/Antimycotic (Gibco) and 10% horse serum. The tissue was digested overnight at 37°C in a rotating water bath and then centrifuged at 2200 rpm for 10 minutes. The supernatant was carefully decanted to a sterile tube. The tissue was rinsed four times with transport medium, resuspended in culture medium, and centrifuged one last time. The tissue was then plated in a swine skin gelatin (Sigma)-coated T-25 flask. Cells were cultured for 24 hours in High Calcium Medium and then refed with Low Calcium Medium 24 hours later. High Calcium Medium consists of DMEM/F12 1:1 without calcium (Gibco), supplemented with 5% chelated horse serum, 20 ng/ml EGF, 100 ng/ml cholera toxin, 10 μg/ml insulin, 0.5 μg/ml hydrocortisone, 1.05 mM calcium chloride, 100 U/ml penicillin, 100 μg/ml streptomycin, 10 μg/ml ciprofloxacin, and 0.25 μg/ml Amphotericin B. Low Calcium Medium was the same recipe supplemented with 0.04 mM calcium chloride (14). Cells were cultured four to six weeks until the flask was confluent.

Oophorectomy specimens were collected under aseptic conditions and placed in transport medium (M199:MCDB105, 1:1) supplemented with 100 U/ml penicillin, 100 μg/ml streptomycin and 2 mM L-glutamine. The ovaries were processed to establish epithelial cell cultures by gently scraping the ovarian surface with a rubber policeman. Cells were centrifuged and resuspended in fresh medium (M199:MCDB105, 1:1), supplemented with 5% FBS, penicillin, streptomycin, glutamine and 0.3 U/ml insulin, and transferred to tissue culture flasks coated with skin gelatin; they were refed every four days and passaged once they reached confluency.

All the breast and ovarian samples were treated with the same tissue-specific culture conditions, including timing for passaging and harvesting. Importantly, all the samples were de-identified, including notation on carrier or control status, and no significant difference in growth or apoptosis among them was noted. At harvest, all cultures were in log phase.

RNA extraction and amplification

Total RNA was prepared from cultured cells by extraction in guanidinium isothiocyanate-based buffer containing β-mercaptoethanol and acid phenol. RNA integrity was evaluated on the Agilent 2100 Bioanalyzer. All samples showed distinct peaks corresponding to intact 28S and 18S ribosomal RNAs and therefore were included in the analysis. Amplification of total RNAs was achieved using the one-cycle Ovation™ biotin system (NuGEN Technologies, Inc., San Carlos, CA) as previously described (15).

Hybridization and microarray analysis

For each sample a total of 2.2 μg of ssDNA, labeled and fragmented with the NuGEN kit, was hybridized to Affymetrix arrays (Human U133 plus 2.0), following the manufacturer's instructions as previously described (15). After washing and staining with biotinylated antibody and streptavidin phycoerythrin, the arrays were scanned with the Affymetrix GeneChip Scanner 3000 for data acquisition.

Real-time reverse transcriptase-PCR (RT-PCR) validation of microarray data

Validation of microarray findings was conducted by real-time RT-PCR, using TaqMan Low Density Arrays (LDA, microfluidic cards from Applied Biosystems). A 48-gene custom made array (44 candidate biomarkers + 4 housekeeping genes) was designed and prepared by Applied Biosystems. The entire panel of 48 genes was tested across breast and ovarian samples. All samples were tested in quadruplicate to ensure accuracy and reproducibility.

Data were obtained in the form of threshold-cycle number (Ct) for each candidate biomarker identified and the housekeeping gene HPRT1 for each genotype (BRCA1, BRCA2, WT). For each gene, the Ct values were normalized to the housekeeping gene and the corresponding ΔCt values obtained for each genotype. Relative quantitation was computed using the Comparative Ct method (Applied Biosystems Reference Manual, User Bulletin #2) between BRCA1 mutants and WT primary cell RNAs. The relative quantitation is the ratio of the normalized amounts of target for BRCA1 mutant for WT RNAs, and is computed as 2ˆ(-ΔCt) where ΔCt is the difference between the mean ΔCt values for BRCA1 mutant and the mean ΔCt values for WT RNAs. We repeated the relative quantitation analyses for BRCA2 mutant and WT RNA samples.

Statistical analysis

We considered breast and ovarian samples for each of the three genotypes: BRCA1, BRCA2 and mutation negative or wild type (WT). There were 6 biological replicates in each experimental condition resulting in a total of 18 samples for each target organ. For each sample, we obtained probe-level data in the form of raw signal intensities for 54675 probe sets from Affymetrix.CEL files. Raw data for each target organ were preprocessed separately using the Robust Multi-chip Average (RMA) method proposed by Irizarry et al. (16, 17).

We applied the variance-stabilizing and normalizing logarithmic transformation to the data before analysis, and used the Local Pooled Error (LPE) method (18) for class comparisons. LPE is based on pooling errors within genes, and between replicate arrays for genes whose expression values are similar. All comparisons were two-sided. The Benjamini-Hochberg step-up method (19) was applied to control the False Discovery Rate (FDR). Genes were defined as differentially expressed, based on statistical significance as well as biological significance. Genes showing an FDR of less than the desired cut-off were considered statistically significant. We accepted an FDR cutoff of 0.20 for breast and 0.10 for ovary. These cut-offs were selected in order to obtain similar numbers of genes. Biological significance was measured as fold change; i.e., the ratio of the mean expression profiles between two conditions. Genes showing more than 2-fold change in either direction (up or down regulated) were considered biologically significant. Differentially expressed genes from each of the above filters were combined, and a list of common genes showing statistical and biological significance was identified. These genes were subsequently validated using RT-PCR. The analytical tools available in the R/BioConductor package (http://www.r-project.org, http://www.bioconductor.org), bioNMF (20) and TMev (http://www.tm4.org) were utilized in these computations.

Data mining analysis

Pathway and association analyses were conducted to obtain additional insight into the functional relevance of the changes observed. Up and down regulated genes for these exploratory analyses were selected as described above, but using a more relaxed p-value cutoff of 0.001. Gene ontology (GO) functional categories enriched in differentially expressed genes were identified using conditional hyper-geometric tests in the GOstats package (R/BioConductor). A p-value cut off of 0.01 was used in selecting GO terms. Furthermore, gene networks were generated using Ingenuity Pathways Analysis version 6.5 (Ingenuity® Systems, www.ingenuity.com). Gene Set Enrichment Analysis (GSEA) (21) was performed against the lists of differentially expressed genes for BRCA1-WT and BRCA2-WT comparisons. Gene sets from MSigDB (21), including positional, curated, motif and computational sets, were tested. Default parameters were chosen, except that the maximum intensity of probes was only selected while collapsing probe sets for a single gene.

Next we compiled and analyzed publicly available microarray gene expression data from the following: i) a study of mammary gland side population cells (22); ii) a study of two different human breast epithelial cell types, BPEC (breast primary epithelial cells) and HMEC (human mammary epithelial cells), compared to their transformed counterparts (23); iii) a molecular characterization of cancer stem cells in MMTV-Wnt1 murine breast tumors (24); iv) profiles of hereditary breast cancer (25) and v) a set of annotated genes involved in DNA damage repair. The data from these studies were analyzed (a description of the methods is given in supplementary materials). The differentially expressed genes between BRCA1, BRCA2 and WT from our study were compared against the above mentioned gene sets using GSEA.

Results

Genome-wide transcriptome analysis of single-hit BRCA1 and BRCA2 and mutation-negative breast and ovarian epithelial cell cultures

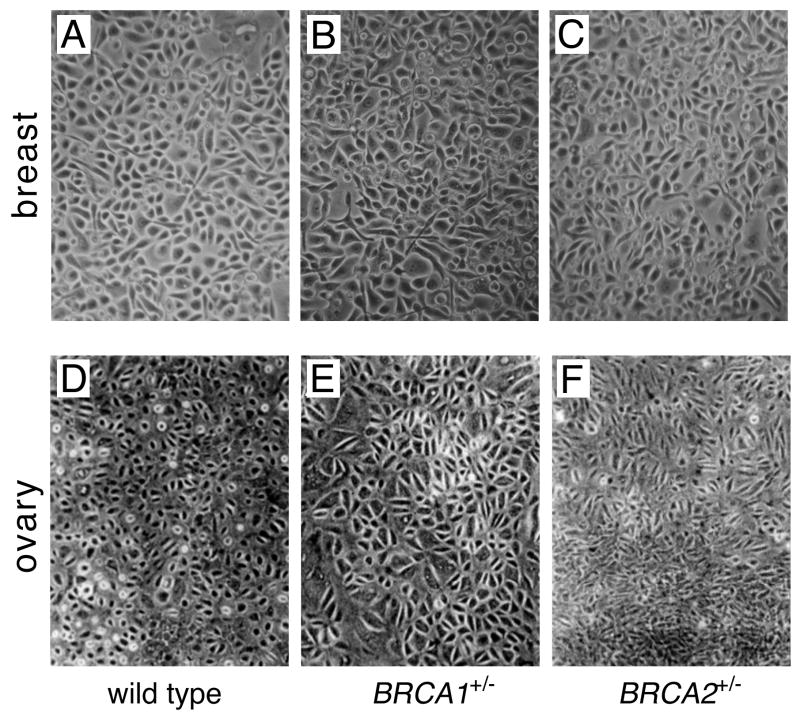

We are interested in the growth behavior of cells that are precursors of cancer; therefore, we chose to study primary cells multiplying in culture. Morphologically normal primary breast and ovarian epithelial cells were established from BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutation carriers and mutation-negative individuals (Fig. 1). Demographic and mutation data of mutation carriers and control individuals are shown in Table 1. The Table shows that our population is mostly Caucasian, and that carriers and controls are well matched for age, race, parity, menopausal status and body mass index, with the only exception being the group of BRCA1 carriers donating ovarian epithelial cells in which there is a predominance of pre-menopausal women. This is due to the fact that carriers of highly penetrant BRCA1 mutations were advised to undergo prophylactic oophorectomy. We conducted microarray studies of these primary epithelial cultures in order to identify differentially expressed genes between BRCA1 mutant and BRCA2 mutant single-hit cells and WT cells, for each target organ.

Figure 1.

Primary cultures of normal breast (A-C) and ovarian (D-F) epithelial cells from control individuals (A, D), BRCA1 mutation carriers (B, E) and BRCA2 mutation carriers (C, F). For each tissue of origin, cellular morphology is similar, irrespective of genotype.

Table 1. Demographic and mutation data of the patients enrolled in this study.

| Sample ID | Epithelial culture | BRCA | Mutation | Age | Race | Parity | Menopause status | Weight (pounds) | Height (inches) | Body mass index |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 218 | Breast | B1 | 2800delAA; BRCA1 c.2681_2682del | 45 | C | 2 | Post | 165 | 70 | 23.7 |

| 256 | Breast | B1 | R1835X; BRCA1 c5503C>T (p.R1835X) | 50 | C | 2 | Post | 137 | 62 | 25.1 |

| 288 | Breast | B1 | 185delAG; BRCA1 c.68_69delAG | 70 | C | 2 | Post | 116 | NA | NA |

| 349 | Breast | B1 | 1997insTAGT; BRCA1 c.1878_1879insTAGT | 28 | C | 0 | Pre | 127 | 64 | 22.5 |

| 425 | Breast | B1 | T1194I, BRCA1 c.3581C>T (pT119I)* | 45 | C | 5 | Pre | 126 | 64 | 22.3 |

| 479 | Breast | B1 | R1751X; BRCA1 c.5251C>T (p.R1751X) | 48 | C | 3 | Post | 211 | 64 | 37.4 |

| 182 | Breast | B2 | 6174delT; BRCA2 c.5945delT | 44 | C | 0 | Pre | 115 | 66 | 19.1 |

| 197 | Breast | B2 | 2912delC; BRCA2 c.2683delC | 47 | C | 4 | Pre | 138 | 62 | 25.2 |

| 285 | Breast | B2 | R2394X; BRCA2 c.7181A>T | 37 | AA | 3 | Pre | 234 | 63 | 41.4 |

| 300 | Breast | B2 | UN | 45 | C | 2 | Pre | 131 | 64 | 23.2 |

| 304 | Breast | B2 | K745E; BRCA2 c.2233A>G (p.K745E)* | 61 | AA | 2 | Post | 204 | 64 | 36.1 |

| 308 | Breast | B2 | UN | 51 | C | 0 | Post | NA | NA | NA |

| 158 | Breast | WT | — | 59 | C | 2 | Post | 170 | NA | NA |

| 162 | Breast | WT | — | 74 | C | NA | Post | 130 | NA | NA |

| 161 | Breast | WT | — | 69 | C | 3 | Post | 125 | NA | NA |

| 169 | Breast | WT | — | 49 | C | 3 | Per | NA | NA | NA |

| 187 | Breast | WT | — | 31 | C | 0 | Pre | 161 | 65 | 27.6 |

| 181 | Breast | WT | — | 39 | C | 0 | Post | 102 | NA | NA |

| 166 | Ovary | B1 | IVS16-581del1014; BRCA1-c.4986-581del1014 | 28 | C | 2 | Pre | NA | NA | 18.3 |

| 183 | Ovary | B1 | IVS12-1632del3835; BRCA1-c.4185-1632del3855 | 43 | C | 2 | Pre | NA | NA | NA |

| 193 | Ovary | B1 | IVS16-581del1014; BRCA1-c.4986-581del1014 | 37 | C | 0 | Pre | NA | NA | 20.8 |

| 194 | Ovary | B1 | 1632del5-ter503; BRCA1 c.1513del5 (p.503X) | 43 | C | 2 | Pre | NA | NA | NA |

| 201 | Ovary | B1 | IVS12-1632del3835; BRCA1-c.4185-1632del3855 | 44 | C | 3 | Pre | NA | NA | 29.4 |

| 217 | Ovary | B1 | UN | 46 | C | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| 302 | Ovary | B2 | 9663delGT; BRCA1 c9434_9435del | 44 | C | 3 | Pre | 184 | 66 | 28.2 |

| 206 | Ovary | B2 | 9132delC-ter2975; BRCA2 c.8903delC (p.2975X) | 39 | C | 2 | Pre | 110 | 64 | 18.9 |

| 328 | Ovary | B2 | UN | 38 | C | 3 | Pre | 189 | NA | NA |

| 431 | Ovary | B2 | 6174delT; BRCA2 c.5945delT | 54 | C | 0 | Post | 137 | 64 | 24.3 |

| 470 | Ovary | B2 | UN | 57 | C | 1 | Post | 123 | 60 | 24 |

| 612 | Ovary | B2 | UN | 42 | C | 3 | Pre | 145 | 66 | 23.4 |

| 178 | Ovary | WT | — | 60 | C | 0 | Post | 286 | 65 | 47.6 |

| 211 | Ovary | WT | — | 40 | C | 3 | Pre | 121 | NA | NA |

| 276 | Ovary | WT | — | 38 | C | 4 | Pre | 188 | 65 | 31.3 |

| 207 | Ovary | WT | — | 45 | C | 0 | Post | 130 | 61 | 24.6 |

| 121 | Ovary | WT | — | 33 | C | 0 | Post | 200 | 65 | 33.3 |

| 600 | Ovary | WT | — | 45 | C | 2 | Pre | 155 | 64 | 26.6 |

Abbreviations: WT, individual tested negative for a BRCA1 and BRCA2 alteration; UN, patient self reported prior to surgery but declined to share the specific mutation

Missense mutation, unique to Breast Cancer Information Core (http://research.nhgri.nih.gov/bic/index.shtml), segregates with disease, suspected deleterious C, Caucasian; AA, African American

NA, information was not available

Class comparison analyses (BRCA1 vs. wild type, and BRCA2 vs. wild type) revealed notable changes in gene expression, indicating that heterozygous mutations in BRCA1 and BRCA2 do indeed affect the expression profiles of cultured primary epithelial cells from the relevant target organs, breast and ovary.

Breast Epithelial Cells

Table 2 summarizes selected gene expression fold-changes on a linear scale in breast cells versus controls. The secretoglobin family of genes (SCGB2A1, SCGB2A2 and SCGB1D2), of unknown function, is highly up-regulated in BRCA1 mutant breast cells. The genes have been recently described as novel serum markers of breast cancer with significant prognostic value (26, 27); approximately 80% of all breast cancers overexpress this complex (26). In BRCA1 cells, we observed 3-fold up-regulation of mammaglobin (SCGB2A2, FDR:0.06, P value:4×10-10) and 12-fold increase of lipophilin B and C (SCGB1D2 and SCGB2A, FDR:0.06, P value:2×10-8 and FDR:0.16, P value:0.0002, respectively). We also detected in BRCA1 cells a 3-fold up-regulation of the chitinase 3-like 1 gene (FDR:0.06, P value:1.2×10-7), that has proliferative effects on stromal fibroblasts and chemotactic effects on endothelial cells. It can promote angiogenesis, and high serum levels of this protein have been found in patients with glioblastoma (28). IGFBP5 was 10-fold up-regulated in BRCA2 breast cells (FDR: 0.04, P value:1.9×10-7). It is involved in the stimulation of growth and binding to extracellular matrix, independently of IGF, and is highly overexpressed in breast cancer tissues (29).

Table 2.

Comparison between microarray and low density array (LDA) data for the candidate breast biomarkers; fold changes are shown for BRCA1 vs. WT and for BRCA2 vs. WT comparisons

| A. BRCA1 vs. WT comparison | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gene Symbol | Gene Name | Affymetrix | LDA | Taq Man Assay |

| SCGB1D2 | Secretoglobin, family 1D, member 2 | 12 | 5.2 | Hs00255208_m1 |

| SCGB2A1 | Secretoglobin, family 2A, member 1 | 12 | 2.68 | Hs00267180_m1 |

| SCGB2A2 | Secretoglobin, family 2A, member 2 | 3 | 3.8 | Hs00267190_m1 |

| CHI3L1 | Chitinase 3-like 1 | 3 | 2.24 | Hs00609691_m1 |

| MCM6 | minichromosome maintenance complex component 6 | 2.8 | 1.37 | Hs00195504_m1 |

| MUC1 | Mucin 1, cell surface associated | 0.5 | 0.25 | Hs00159357_m1 |

| LGALS1 | Lectin, galactoside-binding, soluble, 1 | 0.5 | 0.33 | Hs00169327_m1 |

| KLK10 | Kallikrein-related peptidase 10 | 0.5 | 0.15 | Hs00173611_m1 |

| ANXA8 | Annexin A8 | 0.4 | 0.14 | Hs00179940_m1 |

| TNS4 | Tensin 4 | 0.3 | 0.08 | Hs00262662_m1 |

| MUC16 | Mucin 16, cell surface associated | 0.3 | 0.17 | Hs00226715_m1 |

| GJB2 | Gap junction protein, beta 2, 26kDa | 0.2 | 0.12 | Hs00269615_s1 |

| B. BRCA2 vs. WT comparison | ||||

| Gene Symbol | Gene Name | Affymetrix | LDA | Taq Man Assay |

| IGFBP5 | Insulin-like growth factor binding protein 5 | 10 | 10.99 | Hs00181213_m1 |

| SPP1 | Secreted phosphoprotein 1(Osteopontin) | 3 | 2.3 | Hs00167093_m1 |

| RRM2 | Ribonucleotide reductase M2 polypeptide | 0.58 | 0.39 | Hs00357247_g1 |

| TNS4 | Tensin 4 | 0.5 | 0.45 | Hs00262662_m1 |

| TNFSF13 | Tumor necrosis factor superfamily, member 13 | 0.5 | 0.56 | Hs00601664_g1 |

| SFN | Stratifin | 0.5 | 0.34 | Hs00356613_m1 |

| KRT14 | Keratin 14 | 0.5 | 0.07 | Hs00559328_m1 |

| CENPA | Centromere protein A | 0.5 | 0.57 | Hs00156455_m1 |

| BIRC5 | Baculoviral IAP repeat-containing 5 | 0.5 | 0.43 | Hs00153353_m1 |

| MUC16 | Mucin 16, cell surface associated | 0.25 | 0.2 | Hs00226715_m1 |

| PAX8 | Paired box gene 8 | 0.2 | 0.61 | Hs00247586_m1 |

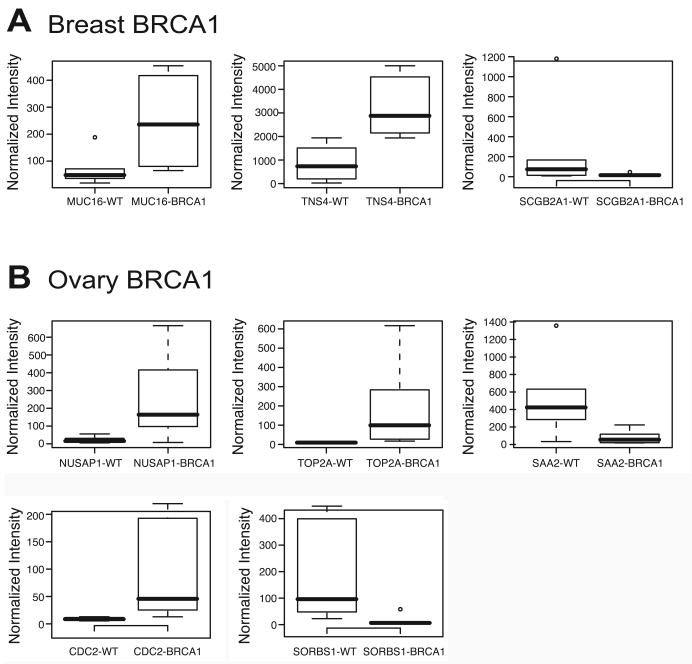

Several cell-to-cell interactions and cell-to-matrix adhesion genes were found to be downregulated in breast cells, including those that code for tensin 4 (TNS4, fold change: 0.26, FDR:0.06, P value:2.2×10-7 in BRCA1 and fold change: 0.5, FDR:0.03, P value:3.7×10-6), mucin 16 (MUC16, fold change: 027, FDR:0.08, P value:3×10-5 in BRCA1 and fold change: 024, FDR:0.03, P value:2×10-6 in BRCA1) (in both BRCA1 and BRCA2) and for keratin 14 (KRT14, fold change: 0.5, FDR:0.12, P value:0.0001 in BRCA1 and fold change: 0.5, FDR:0.03, P value:2.2×10-10 in BRCA2) (in BRCA2). Lack of tensin 4 expression has been reported in prostate and breast cancers (30), suggesting that the down-regulation of tensin expression is a functional marker of cell transformation. Also, loss of keratins, which are necessary for proper structure and function of desmosomes, can cause an increase in cell flexibility and deformability, and may enable a tumor cell to detach from its epithelial layer, and metastasize. Finally, mucin 1 (MUC1 or CA15-3), known to be over-expressed in breast cancer (31), is down-regulated in ‘single-hit’ BRCA1 cells (fold change: 0.5, FDR:0.99, P value:0.02). Overrepresentation of even one glycoprotein may affect cell surface protein distribution, with effects on other membrane proteins, such as the downregulation of genes encoding mucin 16 and mucin 1 that we have detected in mutant breast cells. A box plot representation of the top differentially expressed genes for breast epithelial cells is shown in Fig. 2A.

Figure 2. Gene expression differences in BRCA1 and BRCA2 heterozygous epithelial cells.

Box plots are shown for the top differentially expressed genes for breast BRCA1 and ovary. Values are normalized expression values (intensity produced by RMA analysis).

Ovarian epithelial cells

Table 3 summarizes expression changes for selected genes in ovarian epithelial cultures. For example, 5-fold down-regulation of the cyclin B1/cdc2 complex (CDC2, FDR:0.04, P value:7×10-5), a key regulator controlling the G2M checkpoint, was observed in BRCA1 mutant ovarian cells. Multiple genes implicated in the mitotic spindle checkpoint, such as nucleolar and spindle-associated protein 1 (NUSAP-1, fold change: 0.08, FDR:0.02, P value:9×10-9 in BRCA1) were down-regulated. NUSAP-1 plays a crucial role in spindle microtubule organization, whereas CENP-A, which is down-regulated in BRCA2 mutants of breast cells (fold change: 0.5, FDR:0.03, P value:9×10-6), is essential for centromere structure, function and kinetochore assembly. Since BRCA1 and BRCA2, in addition to their role in DNA repair, are also involved in checkpoint pathways, we suggest that inappropriate expression of these proteins could induce abnormal kinetochore function and chromosome mis-segregation, a potential cause of aneuploidy and a critical contributor to oncogenesis. Among up-regulated genes in BRCA1 heterozygous ovarian epithelial cells is SAA2, an acute phase component of the innate immune system (fold change: 6.4, FDR:0.02, P value:2×10-7), a candidate marker of epithelial ovarian cancer (32, 33 and references therein). Among the differentially expressed genes in BRCA2 mutant ovarian epithelial cells, matrix metalloproteinase 3 (MMP3) was upregulated 9- to 12-fold (FDR:0.1, P value:2×10-7); the same tendency has been reported for MMP1 and MMP2 in ovarian cancers (34, 35). Our data also show upregulation of COX1 (cyclooxygenase 1, PTGS1, fold change: 6.6, FDR:0.1, P value:8×10-9) in BRCA2 ovarian epithelial cells, a finding that is consistent with the reported up-regulation of COX1, but not COX2, in ovarian cancer (36, 37). A box plot representation of the top differentially expressed genes for ovarian epithelial cells is shown in Fig. 2B.

Table 3.

Comparison between microarray and low density array (LDA) data for the candidate ovarian biomarkers; fold changes are shown for the BRCA1 vs. WT comparison and BRCA2 vs. WT comparisons

| A. BRCA1 vs. WT comparison | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gene Symbol | Gene Name | Affymetrix | LDA | Taq Man Assay |

| SORBS1 | Sorbin and SH3 domain containing 1 | 7 | 1.78 | Hs00908953_m1 |

| SAA2 | Serum amyloid A2 | 5 | 9.18 | Hs00763479_s1 |

| SAA1;SAA2 | Serum amyloid A1 and A2 | 5 | 17.47 | Hs00761940_s1 |

| CD24 | CD24 | 5 | 49.89 | Hs00273561_s1 |

| MFI2 | Antigen p97 | 3.5 | 7.47 | Hs00195551_m1 |

| SPON1 | Spondin 1 | 2.5 | 8.22 | Hs00391824_m1 |

| THBS1 | Thrombospondin 1 | 2 | 3.96 | Hs00170236_m1 |

| GAS6 | Growth arrest-specific 6 | 2 | 5.91 | Hs00181323_m1 |

| CSPG4 | Chondroitin sulfate proteoglycan 4 | 0.3 | 0.6 | Hs00426981_m1 |

| CCNB1 | Cyclin B1 | 0.2 | 0.55 | Hs00259126_m1 |

| TOP2A | Topoisomerase (DNA) II alpha | 0.1 | 0.07 | Hs00172214_m1 |

| NUSAP1 | Nucleolar and spindle associated protein 1 | 0.1 | 0.22 | Hs00251213_m1 |

| CDC2 | Cell division cycle 2, G1 to S and G2 to M | 0.1 | 0.09 | Hs00364293_m1 |

| B. BRCA2 vs. WT comparison | ||||

| Gene Symbol | Gene Name | Affymetrix | LDA | Taq Man Assay |

| MMP3 | Matrix metallopeptidase 3 | 12.14 | 6.37 | Hs00233962_m1 |

| PTGS1 | Prostaglandin-endoperoxide synthase 1 | 6.60 | 6.56 | Hs00326564_s1 |

| MMP1 | Matrix metallopeptidase 1 | 2.05 | 24.16 | Hs00233958_m1 |

| KRT18 | Keratin 18 | 0.35 | 0.18 | Hs01920599_gH |

Real-time reverse transcriptase-PCR (RT-PCR) validation of microarray data

A validation study on select genes for breast and ovary was performed with total RNA using quantitative, real-time RT-PCR on low-density arrays (LDA). We selected 44 candidate biomarker genes and 4 housekeeping genes, and the entire panel of 48 genes was tested by the Comparative C1 method across all breast and ovarian samples in quadruplicate using a custom-made array, to ensure accuracy and reproducibility. The real-time RT-PCR validation results and the comparisons with the original Affymetrix data are shown in Tables 2 and 3, for breast and ovary, respectively. There was a good correlation (Spearman's ρ) between microarray and LDA data for fold changes of candidate biomarkers in breast and ovarian cultures heterozygous for BRCA1 (0.94 in each case). For candidate biomarkers originally identified in breast and ovarian cultures for one genotype (BRCA1 or BRCA2), there was also a moderate to good correlation between microarray and LDA data for the other genotype (BRCA2 or BRCA1). This is described in more detail in the Supplemental Section and the results are presented in Supplemental Table S1.

Functional Mining of Microarray Data

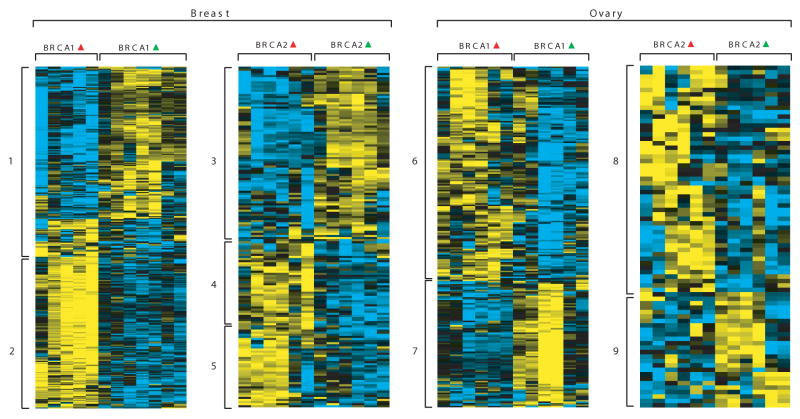

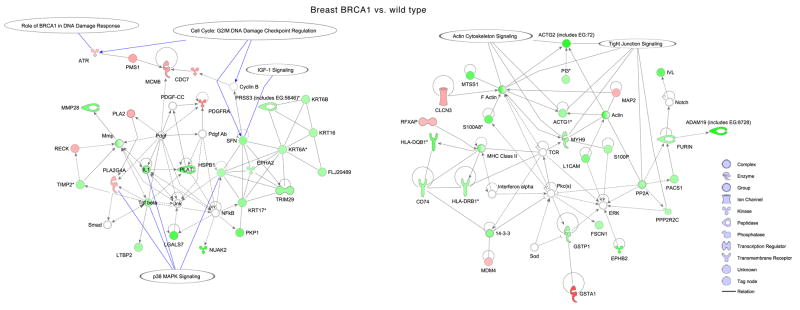

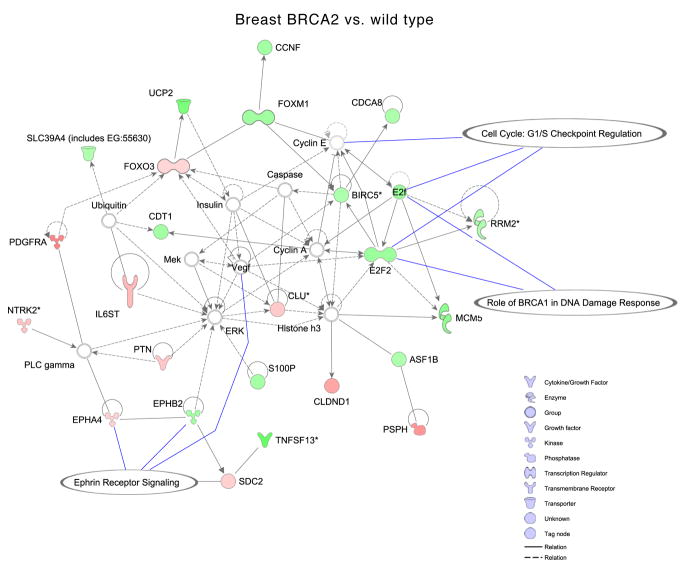

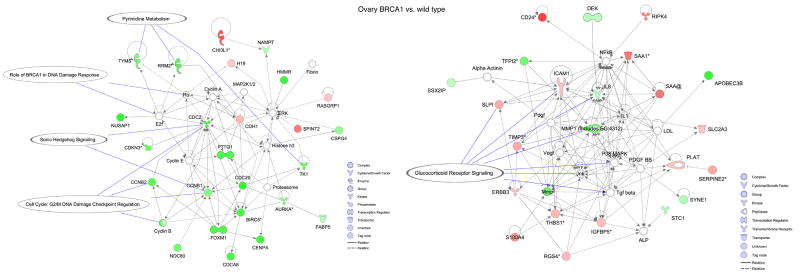

In order to define the biological underpinnings of the observed gene expression differences, we conducted additional mining of the microarray data using gene ontology, pathway and association analyses. Gene ontology analysis revealed overrepresentation of several biological processes in BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutant cells (Fig. 3) (see supplementary information). Next, using differentially expressed genes as input to Ingenuity pathway analysis software, we generated networks and overlaid pathways onto genes to understand their interactions and functional importance. In the case of breast BRCA1 cells, two gene networks had many down-regulated genes involved in G2/M DNA damage checkpoint regulation, DNA damage response, p38 MAPK signaling and tight junction signaling. Genes such as ATR, PMS1 and MCM6 that are involved in BRCA1-related DNA damage response were up-regulated in BRCA1 heterozygous cells (Fig. 4A). Similarly, in breast BRCA2 cells, one significant network was identified that contained genes involved in G1/S checkpoint regulation and ephrin receptor signaling (Fig. 4B). In BRCA1 ovarian cells, two significant networks, involved in cell cycle control (G2/M DNA damage checkpoint regulation) and pyrimidine metabolism, and in glucocorticoid receptor signaling, contained down-regulated genes (Fig. 4C). We did not find any significant networks for genes differentially expressed in ovarian BRCA2 heterozygous cells.

Figure 3. Gene expression patterns between BRCA1, BRCA2 heterozygous and WT cells for breast and ovary.

Each panel shows gene expression patterns represented as a heat map. Red and green deltas represent mutated and WT phenotype respectively. Rows are genes with their expression represented in yellow-blue color scale. Yellow and blue represent high to low respectively. The blocks marked with numbers to left side of each panel represent the enriched biological processes. The Gene Ontology (GO) biological processes enriched for ‘up’ (Yellow') and ‘down’ (‘Blue’) genes (numbers 1-9) are listed in Table S2.

Figure 4. Ingenuity Pathway Analysis showing functional networks in one-hit cells.

Selected significant canonical pathways are shown in relation to genes that are differentially expressed for: A, breast BRCA1; B, breast BRCA2; and C, ovarian BRCA1 heterozygous cells.

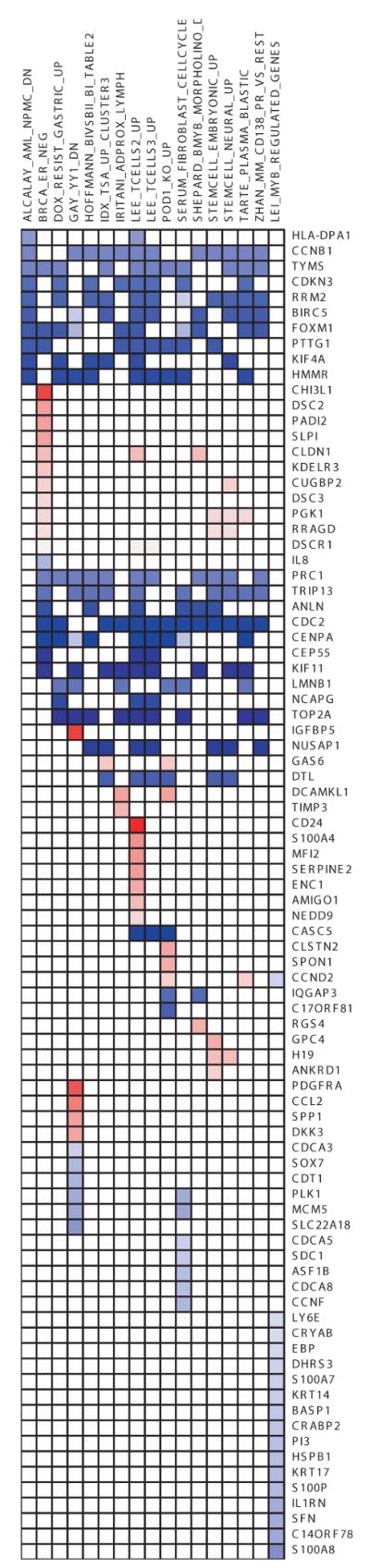

In order to identify unifying biological themes central to mutant breast and ovarian cells in comparison to WT cells, we used GSEA for the detection of complex relationships among co-regulated genes. GSEA is an analytical methodology that allows the evaluation of lists of differentially expressed genes of interest against known biological modules, such as gene sets specific to pathways, processes and profiles, of previous profiling experiments (21). To determine whether any specific pathway or profile is enriched in the four different gene lists, we tested 1,892 curated gene sets obtained through MsigDB which is a constituent database of gene sets available through GSEA. Table S3 shows the gene sets from MsigDb that are enriched in breast and ovarian samples. Fig. 5A is a heatmap of differentially expressed genes in both breast and ovary showing various gene sets that were identified to be enriched. We did not find any significant enrichment for canonical pathways. However, we found a variety of gene sets that are listed in Table S3. Among these, we found two stem cell-related gene sets.

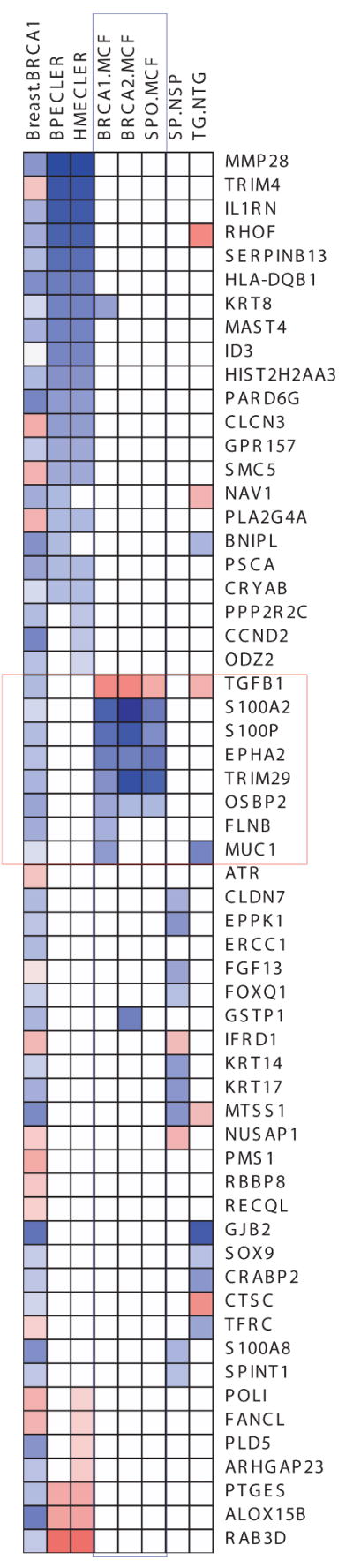

Figure 5. Association heat maps showing union of gene sets enriched for both BRCA1 and BRCA2 in breast and ovary heterozygous cells.

Each row represents a gene whereas columns are gene sets enriched. Blue color indicates that the genes are down-regulated and red color indicates up-regulation. A, Association heatmap of genes in common between the indicated datasets (listed in Table S3) and primary breast BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutant cells. B, Association heatmap of genes in common between transformed human mammary epithelial cells (HMECs) and primary breast BRCA1 and BRCA2 heterozygous cells. In this figure HMEC refers to genes differentially expressed between HMEC-transformed (HMLER) vs. parental HMEC cells. Blue color indicates the down-regulation and red color indicates up-regulation. Breast.BRCA1 column indicates genes differentially expressed in BRCA1 heterozygous cells from breast. SP.NSP indicates differentially expressed genes between mouse mammary side population and non-side population cells (22). TG.NTG column indicate genes differentially expressed between mouse cancer stem cells and non cancerous stem cells (24). Columns in blue box (BRCA1.MCF, BRCA2.MCF and SPO.MCF) are differentially expressed gene sets from Hedenfalk et.al. Genes in red box indicate the genes common to Hedenfalk and Breast.BRCA1.

Since the gene expression profiles in BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutant cells have similarities to those of stem and progenitor cells, we tested the four gene lists from this study against a cohort of gene sets obtained from various studies including breast stem cells from both human and mouse and DNA repair genes (22-24). Breast BRCA1 and BRCA2 cells show significant enrichment with the differentially expressed gene sets of transformed human mammary epithelial cells (HMEC) vs. control HMEC cells and breast primary epithelial cells (BPEC) vs. control BPEC population (Fig. 5B). We observed that down-regulated genes from breast BRCA1 heterozygous cells show significant association with transformed HMEC and BPEC cells suggesting that BRCA1 ‘single-hit’ cells and transformed breast primary cells share a common fingerprint.

Finally, we compared our breast BRCA1 dataset to three datasets of Hedenfalk et al. on sporadic breast cancers as well as breast cancers in families with BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutations (25). The GSEA comparison revealed that our breast epithelial BRCA1 dataset is most similar to the BRCA1 tumors with matching hits corresponding to the following genes: KRT8, TGFB1, S100A2, S100P, EPHA2, TRIM29, OSBP2, FLNB and MUC1. Fig. 5B shows genes from BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutant and sporadic tumors associated with breast BRCA1 heterozygous cells. These genes have already been implicated in breast cancer. For instance, decreased levels of KRT8 in cytoplasm are detected in breast cancer cells (38). TGFB1 is highly expressed in sporadic breast tumors or tumors from BRCA1 and BRCA2 kindreds, whereas in heterozygous BRCA1 breast cells it is downregulated. Calcium binding proteins A2 and P are downregulated across all tissues. Aberrant expression of S100A2 has been implicated in breast cancer. In all genes that are common to three tumor types (BRCA1, BRCA2 and sporadic) and heterozygous BRCA1 cells, expression of TGFB1 is observed to be different. This finding confirms our hypothesis of the earliest significant molecular changes in “one-hit” cells and their relationship with transformed breast cells.

Discussion

Our study demonstrates that mRNA expression profiles are altered in morphologically normal breast and ovarian epithelial cells heterozygous for mutation in BRCA1 or BRCA2, and include functionally critical genes. Remarkably, these single-hit cells bear significant transcriptomic changes that share features of the profiles of the corresponding cancer cells. It is well known that BRCA1- and BRCA2-mutant breast cancers exhibit distinct expression profiles (25), and the same is true for ovarian cancer (39). In the case of our single-hit breast and ovarian epithelial cell cultures, gene expression differences related to a given genotype clearly emerge when supervised methods are used (Tables 2 and 3), and they are reflected in separate clusters (Fig. 3). On the other hand, genome-wide unsupervised analyses using hierarchical clustering and non-negative matrix factorization revealed clusters that differentiate tissue of origin but not genotype (see supplemental material, Fig. S2).

Although these specific molecular changes are yet to be placed in the context of cancer initiation and progression, it should be noted that both BRCA proteins have clear functional links to transcription. Indeed, both are mediators of the cellular response to DNA damage that includes a transcriptional component (40, 41). Of course, damage does occur in normal cells as a consequence of physiological DNA replication processes, although it is repaired with high efficiency (42), and BRCA1 and BRCA2 are part of a protein complex with RNA polymerase II and the CBP and p300 histone acetyltransferases that is involved in chromatin remodeling and transcription (43). Because of these links to transcription (44), alterations in the levels of BRCA1 and BRCA2 proteins in single-hit cells might be expected to lead to multiple gene expression differences.

Intriguingly, some of the gene expression profiles enriched in breast BRCA1 one-hit cells are similar to those detected in stem and progenitor cells (Fig. 5A). This does not appear to be true for one-hit BRCA2 breast epithelial cells. Indeed, recent findings from the Wicha laboratory indicate that the BRCA1 gene is involved in regulating stemness and differentiation of breast progenitor cells (45). Also, more recently, human mammary epithelial cells from BRCA1-mutation carriers were found to form progenitor cell colonies on semisolid medium with higher plating efficiency as compared to mammary epithelial cells from reduction mammoplasty controls (46).

In general, we found more expression changes in BRCA1 vs. WT cells than with BRCA2 vs. WT cells (Table 2), which may reflect the fact that BRCA2 is primarily involved in double-strand break repair, whereas BRCA1 may also bridge double-strand break repair and signal transduction pathways. Thus, BRCA1 may act both as a sensor of DNA damage and as a repair factor, whereas BRCA2 is thought to be involved primarily in actual repair. Even small alterations in levels of the sensor (BRCA1) may have phenotypic consequences in terms of differentially expressed genes. This is reminiscent of animal models with hypomorphic alleles of the mismatch repair protein MSH2 (part of the damage sensor) that are proficient for mismatch repair per se but defective for activation of the cellular DNA damage response (47).

An additional important finding from this study is that some of the molecular changes detected correspond to candidate biomarkers described previously for breast and ovarian cancer, such as mammaglobin and serum amyloid protein for breast and ovarian cancer, respectively (Tables 2 and 3). Furthermore, GSEA analysis reveals that the dataset of breast epithelial BRCA1 one-hit cells shows similarities to that of hereditary breast carcinomas associated with BRCA1 mutations (Fig. 5B).

In conclusion, the findings from this study are largely consistent with what is known about the pathophysiology of BRCA1 and BRCA2 and sporadic cancers. However, there are genes with abnormal patterns of expression that seem unrelated. Both their number and their unrelatedness are unexplainable based on what is known about BRCA1 and BRCA2 cancers, but they may be early changes associated indirectly with cancer initiation (7, 8). For example, heterozygosity may trigger a phenomenon such as induction of expression of siRNAs, each of which might affect the expression of multiple genes

In principle, therefore, the genetic approach used in this study may serve as a model for the identification of biomarkers for epithelial malignancies in general, and for the use of such markers as targets for chemoprevention measures that would decrease the probability of a second “hit” or greatly reduce its occurrence.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Jeff Boyd for critical reading of the manuscript and R. Sonlin for expert secretarial assistance. We thank the Fannie E. Rippel Biotechnology Facility, the Biomarker and Genotyping Facility, the Cell Culture Facility, and the Biosample Repository at the Fox Chase Cancer Center for technical support.

Grant support: This study was supported by NIH contracts N01 CN-95037, N01-CN-43309, the Ovarian Cancer SPORE at FCCC (P50 CA083638), NIH grant P30 CA06927, an appropriation from the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania to the Fox Chase Cancer Center, and the Eileen Stein Jacoby Fund.

References

- 1.Fearon ER, Vogelstein B. A genetic model for colorectal tumorigenesis. Cell. 1990;61:759–67. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(90)90186-i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Armitage P, Doll R. The age distribution of cancer and a multistage theory of carcinogenesis. Br J Cancer. 1954;8:1–12. doi: 10.1038/bjc.1954.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Erickson LC. The role of O-6 methylguanine DNA methyltransferase (MGMT) in drug resistance and strategies for its inhibition. Semin Cancer Biol. 1991;2:257–65. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Danes BS. Increased in vitro tetraploidy: tissue specific within the heritable colorectal cancer syndromes with polyposis coli. Cancer. 1978;41:2330–4. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(197806)41:6<2330::aid-cncr2820410635>3.0.co;2-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kopelovich L. Phenotypic markers in human skin fibroblasts as possible diagnostic indices of hereditary adenomatosis of the colon and rectum. Cancer. 1977;40:2534–41. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(197711)40:5+<2534::aid-cncr2820400921>3.0.co;2-f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kopelovich L. Heritable colorectal cancer and cancer genes: systemic expressions. Mol Carcinog. 1993;8:3–6. doi: 10.1002/mc.2940080104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Yeung AT, Patel BB, Li XM, et al. One-hit effects in cancer: altered proteome of morphologically normal colon crypts in familial adenomatous polyposis. Cancer Res. 2008;68:7579–86. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-0856. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kopelovich L. Genetic predisposition to cancer in man: in vitro studies. Int Rev Cytol. 1982;77:63–88. doi: 10.1016/s0074-7696(08)62464-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Stoyanova R, Clapper ML, Bellacosa A, et al. Altered gene expression in phenotypically normal renal cells from carriers of tumor suppressor gene mutations. Cancer Biol Ther. 2004;3:1313–21. doi: 10.4161/cbt.3.12.1459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Futreal PA, Liu Q, Shattuck-Eidens D, et al. BRCA1 mutations in primary breast and ovarian carcinomas. Science. 1994;266:120–2. doi: 10.1126/science.7939630. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Miki Y, Swensen J, Shattuck-Eidens D, et al. A strong candidate for the breast and ovarian cancer susceptibility gene BRCA1. Science. 1994;266:66–71. doi: 10.1126/science.7545954. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tavtigian SV, Simard J, Rommens J, et al. The complete BRCA2 gene and mutations in chromosome 13q-linked kindreds. Nat Genet. 1996;12:333–7. doi: 10.1038/ng0396-333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wooster R, Bignell G, Lancaster J, et al. Identification of the breast cancer susceptibility gene BRCA2. Nature. 1995;378:789–92. doi: 10.1038/378789a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Soule HD, Maloney TM, Wolman SR, et al. Isolation and characterization of a spontaneously immortalized human breast epithelial cell line, MCF-10. Cancer Res. 1990;50:6075–86. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Caretti E, Devarajan K, Coudry R, et al. Comparison of RNA amplification methods and chip platforms for microarray analysis of samples processed by laser capture microdissection. J Cell Biochem. 2008;103:556–63. doi: 10.1002/jcb.21426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Irizarry RA, Bolstad BM, Collin F, Cope LM, Hobbs B, Speed TP. Summaries of Affymetrix GeneChip probe level data. Nucleic Acids Res. 2003;31:e15. doi: 10.1093/nar/gng015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Irizarry RA, Hobbs B, Collin F, et al. Exploration, normalization, and summaries of high density oligonucleotide array probe level data. Biostatistics. 2003;4:249–64. doi: 10.1093/biostatistics/4.2.249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jain N, Thatte J, Braciale T, Ley K, O'Connell M, Lee JK. Local-pooled-error test for identifying differentially expressed genes with a small number of replicated microarrays. Bioinformatics. 2003;19:1945–51. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btg264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Benjamini Y, Hochberg Y. Controlling the false discovery rate: A practical and powerful approach to multiple testing. J Royal Stat Soc B. 1995;57:289–300. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Pascual-Montano A, Carmona-Saez P, Chagoyen M, Tirado F, Carazo JM, Pascual-Marqui RD. bioNMF: a versatile tool for non-negative matrix factorization in biology. BMC Bioinformatics. 2006;7:366–74. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-7-366. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Subramanian A, Tamayo P, Mootha VK, et al. Gene set enrichment analysis: a knowledge-based approach for interpreting genome-wide expression profiles. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102:15545–50. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0506580102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Behbod F, Xian W, Shaw CA, Hilsenbeck SG, Tsimelzon A, Rosen JM. Transcriptional profiling of mammary gland side population cells. Stem Cells. 2006;24:1065–74. doi: 10.1634/stemcells.2005-0375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ince TA, Richardson AL, Bell GW, et al. Transformation of different human breast epithelial cell types leads to distinct tumor phenotypes. Cancer Cell. 2007;12:160–70. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2007.06.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Cho RW, Wang X, Diehn M, et al. Isolation and molecular characterization of cancer stem cells in MMTV-Wnt-1 murine breast tumors. Stem Cells. 2008;26:364–71. doi: 10.1634/stemcells.2007-0440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hedenfalk I, Duggan D, Chen Y, et al. Gene-expression profiles in hereditary breast cancer. N Engl J Med. 2001;344:539–48. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200102223440801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bernstein JL, Godbold JH, Raptis G, et al. Identification of mammaglobin as a novel serum marker for breast cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2005;11:6528–35. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-05-0415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ntoulia M, Stathopoulou A, Ignatiadis M, et al. Detection of Mammaglobin A-mRNA-positive circulating tumor cells in peripheral blood of patients with operable breast cancer with nested RT-PCR. Clin Biochem. 2006;39:879–87. doi: 10.1016/j.clinbiochem.2006.06.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Junker N, Johansen JS, Hansen LT, Lund EL, Kristjansen PE. Regulation of YKL-40 expression during genotoxic or microenvironmental stress in human glioblastoma cells. Cancer Sci. 2005;96:183–90. doi: 10.1111/j.1349-7006.2005.00026.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Li X, Cao X, Zhang W, Feng Y. Expression level of insulin-like growth factor binding protein 5 mRNA is a prognostic factor for breast cancer. Cancer Sci. 2007;98:1592–6. doi: 10.1111/j.1349-7006.2007.00565.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lo SH, Lo TB. Cten, a COOH-terminal tensin-like protein with prostate restricted expression, is down-regulated in prostate cancer. Cancer Res. 2002;62:4217–21. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.von Mensdorff-Pouilly S, Snijdewint FG, Verstraeten AA, Verheijen RH, Kenemans P. Human MUC1 mucin: a multifaceted glycoprotein. Int J Biol Markers. 2000;15:343–56. doi: 10.1177/172460080001500413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Khan N, Cromer CJ, Campa M, Patz EF., Jr Clinical utility of serum amyloid A and macrophage migration inhibitory factor as serum biomarkers for the detection of nonsmall cell lung carcinoma. Cancer. 2004;101:379–84. doi: 10.1002/cncr.20377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Moshkovskii SA, Serebryakova MV, Kuteykin-Teplyakov KB, et al. Ovarian cancer marker of 11.7 kDa detected by proteomics is a serum amyloid A1. Proteomics. 2005;5:3790–7. doi: 10.1002/pmic.200401205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wenham RM, Calingaert B, Ali S, et al. Matrix metalloproteinase-1 gene promoter polymorphism and risk of ovarian cancer. J Soc Gynecol Investig. 2003;10:381–7. doi: 10.1016/s1071-5576(03)00141-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kenny HA, Kaur S, Coussens LM, Lengyel E. The initial steps of ovarian cancer cell metastasis are mediated by MMP-2 cleavage of vitronectin and fibronectin. J Clin Invest. 2008;118:1367–79. doi: 10.1172/JCI33775. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Daikoku T, Wang D, Tranguch S, et al. Cyclooxygenase-1 is a potential target for prevention and treatment of ovarian epithelial cancer. Cancer Res. 2005;65:3735–44. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-3814. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Gupta RA, Tejada LV, Tong BJ, et al. Cyclooxygenase-1 is overexpressed and promotes angiogenic growth factor production in ovarian cancer. Cancer Res. 2003;63:906–11. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Iwaya K, Ogawa H, Mukai Y, Iwamatsu A, Mukai K. Ubiquitin-immunoreactive degradation products of cytokeratin 8/18 correlate with aggressive breast cancer. Cancer Sci. 2003;94:864–70. doi: 10.1111/j.1349-7006.2003.tb01368.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Jazaeri AA, Yee CJ, Sotiriou C, Brantley KR, Boyd J, Liu ET. Gene expression profiles of BRCA1-linked, BRCA2-linked, and sporadic ovarian cancers. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2002;94:990–1000. doi: 10.1093/jnci/94.13.990. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Harper JW, Elledge SJ. The DNA damage response: ten years after. Mol Cell. 2007;28:739–45. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2007.11.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Zhou BB, Elledge SJ. The DNA damage response: putting checkpoints in perspective. Nature. 2000;408:433–9. doi: 10.1038/35044005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Vilenchik MM, Knudson AG. Endogenous DNA double-strand breaks: production, fidelity of repair, and induction of cancer. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2003;100:12871–6. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2135498100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Welcsh PL, Owens KN, King MC. Insights into the functions of BRCA1 and BRCA2. Trends Genet. 2000;16:69–74. doi: 10.1016/s0168-9525(99)01930-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Yoshida K, Miki Y. Role of BRCA1 and BRCA2 as regulators of DNA repair, transcription, and cell cycle in response to DNA damage. Cancer Sci. 2004;95:866–71. doi: 10.1111/j.1349-7006.2004.tb02195.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Liu S, Ginestier C, Charafe-Jauffret E, et al. BRCA1 regulates human mammary stem/progenitor cell fate. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105:1680–5. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0711613105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Burga LN, Tung NM, Troyan SL, et al. Altered proliferation and differentiation properties of primary mammary epithelial cells from BRCA1 mutation carriers. Cancer Res. 2009;69:1273–8. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-2954. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Claij N, Te Riele H. Methylation tolerance in mismatch repair proficient cells with low MSH2 protein level. Oncogene. 2002;21:2873–9. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1205395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.