The development of efficient cyclization methods for five-membered ring formation constitutes a continuing challenge in natural and designed molecule construction. Among these methods, the cycloisomerization of 1,6-enynes to form cyclopentane rings has evolved into a powerful technology in chemical synthesis in the past few years. A number of transition metal complexes, such as those of Pd,[1] Ru,[2] Rh[3] and Fe,[4] have proven to be effective catalysts in this transformation. Rh-Based catalytic systems have attracted particular attention as they demonstrated excellent reactivity and enantioselectivity when applied to internal alkyne substrates.[3] However, in some instances an exocyclic methylene group (as opposed to a substituted olefinic bond) is needed on the resulting intermediates for direct elaboration to more advanced products, a condition that requires terminal alkynes as substrates. Although “capped” alkynes with disposable groups have been utilized in this regard, their removal can be laborious and inefficient. Herein we report a Rh-catalyzed asymmetric enyne cycloisomerization reaction using terminal alkynes as substrates and its application to a formal total synthesis of (−)-platensimycin.

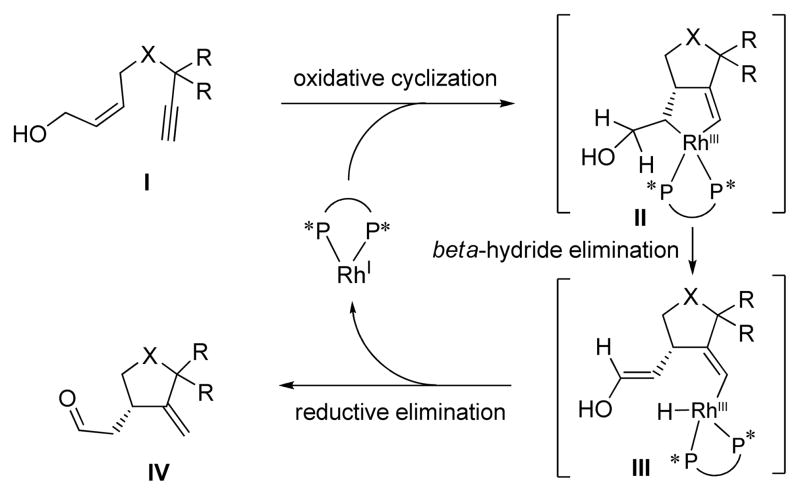

Scheme 1 shows the proposed mechanism for the Rh-catalyzed cycloisomerization of terminal acetylene (I) to a cyclopentane derivative (IV) through transient species II and III.

Scheme 1.

Proposed mechanism of Rh-catalyzed asymmetric cycloisomerization of terminal enynes.

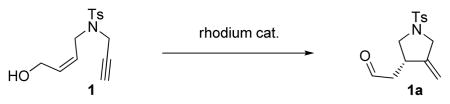

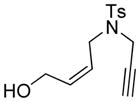

Employing 1,6-enyne 1 as a substrate we examined a number of Rh-based complexes in order to find the optimum catalytic system; our results are summarized in Table 1. Thus, while the reactivity of [Rh(cod)(MeCN)2]BF4 in the presence of (S)-BINAP was rather modest (36 % yield of product 1a, after 12 h at 23 °C), the product was obtained in promising ee (90 %, Table 1, entry 1). The complex generated in situ by mixing [Rh(cod)Cl]2 and AgOTf in the presence of (S)-BINAP led to a 60 % yield and a comparable ee (91 %, Table 1, entry 2), whereas the combination of [Rh(cod)Cl]2, AgSbF6, and (S)-BINAP employed by Zhang et al. with internal alkynes[3] gave 1a in 65 % yield and 95 % ee (Table 1, entry 3). Finally, it was found that the preformed rhodium catalyst [Rh((S)-BINAP)]SbF6[5] gave the best results, furnishing product 1a in 86 % yield and > 99 % ee (Table 1, entry 4).

Table 1.

Catalyst screening.a

| |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Catalyst | Yield of 1a [%] | ee [%]b | |

| 1 | [Rh(cod)(MeCN)2]BF4,(S)-BINAP | 36 | 90 |

| 2 | [Rh(cod)Cl]2, (S)-BINAP, AgOTf | 60 | 91 |

| 3 | [Rh(cod)Cl]2, (S)-BINAP, AgSbF6 | 65 | 95 |

| 4 | [Rh((S)-BINAP)]SbF6 | 86 | >99 |

Reactions were run in DCE (0.4 M) in the presence of 5–10 mol % catalyst at 23°C for 12–16 h.

Measured by chiral HPLC (OD-H column) after derivatization to the corresponding p-bromobenzoate ester. BINAP = 2,2′-bis(diphenylphosphino)-1,1′-binaphthalene, cod = 1,5-cyclooctadiene, DCE = 1,2-dichloroethane.

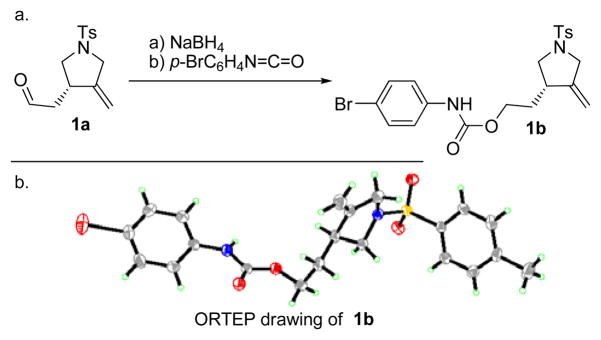

The absolute configuration of product 1a was determined by X-ray crystallographic analysis of its p-bromophenyl carbamate derivative[6] (1b, m.p. 99–101 °C, EtOAc/hexanes 1:1) prepared from 1a through sequential NaBH4 reduction and treatment with p-bromophenyl isocyanate in the presence of Et3N, as shown in Scheme 2.

Scheme 2.

Preparation and X-ray crystallographic analysis of p-bromophenyl carbamate 1b. Reagents and conditions: a) NaBH4 (1.5 equiv), EtOH, 0 °C, 15 min; b) p-bromophenyl isocyanate (1.05 equiv), Et3N (1.05 equiv), 0 °C, 1 h, 72 % over two steps. Non-hydrogen atoms are shown as 30 % ellipsoids.

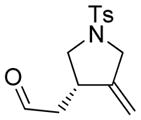

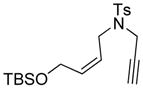

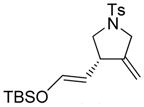

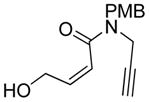

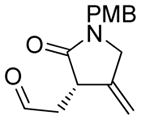

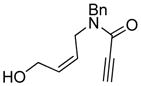

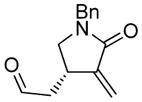

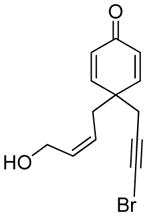

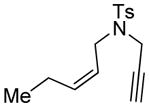

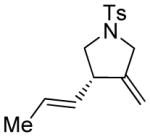

The generality and scope of the developed asymmetric reaction are demonstrated by the results shown in Table 2. In general, most substrates examined led to good yields and excellent ee’s. The cycloisomerization reaction works well not only with free cis allylic alcohols as demonstrated by most examples in Table 2 (entries 1, 3–11), but also with TBS-protected allylic alcohols, in which case the product with a TBS enol ether moiety is obtained[7] as opposed to the aldehyde (Table 2, entry 2). However, the corresponding trans allylic alcohols are poor substrates as shown with allylic alcohol 3 (Table 2, entry 3). The reaction tolerates a variety of structural motifs, including sulfonamides (Table 2, entries 1–4), lactams (Table 2, entries 5 and 6[8]), 1,1-diesters and sulfones (Table 2, entries 7–9), bis-aromatic moieties (Table 2, entry 10), and dienones (i.e. Table 2, entry 11). Notably, electron withdrawing conjugation is tolerated in either π-system of the substrate (Table 2, entries 5 and 6). The latter example featuring a bromo-acetylene expands considerably the scope of this method due to the fertile chemistry of the stereodefined resulting vinyl bromides (Table 2, entry 11).

Table 2.

Asymmetric cycloisomerization reactions.a

| Entry | Substrate | Product | Yield[%] | ee [%] |

|---|---|---|---|---|

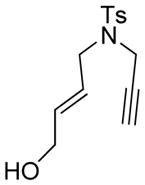

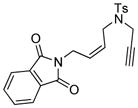

| 1 |

1 |

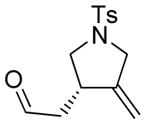

1a |

86 | >99b |

| 2 |

2 |

2a |

90 | 97b |

| 3 |

3 |

3a |

45 | 29c |

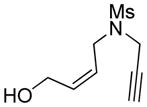

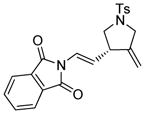

| 4 |

4 |

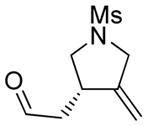

4a |

85 | >98c |

| 5 |

5 |

5a |

75 | 98c |

| 6d |

6 |

6a |

89 | 93b |

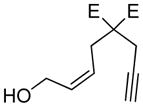

| 7 |

7:E=CooMe |

7a |

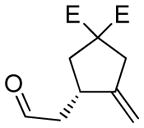

78 | 97c |

| 8d | 8:E=Cooipr | 8a | 84 | >98c |

| 9d | 9:E=So2ph | 9a | 92 | 87c |

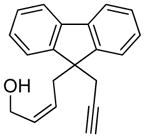

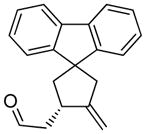

| 10 |

10 |

10a |

85 | >98c |

| 11 |

11 |

11a |

92 | >99b |

| 12d |

12 |

12a |

93 | >98e |

| 13d |

13 |

13a |

83 | 94f |

Reactions were run in DCE (0.4 M) in the presence of 10 mol % [Rh((S)-BINAP)]SbF6 at 23 °C for 12–16 h.

Measured by chiral HPLC (OD-H column) after derivatization to the corresponding p-bromobenzoate ester or ethylene glycol acetal.

Measured by 1H and 19F NMR spectroscopic analysis of the corresponding Mosher ester.

Reactions were run in acetone as solvent.

Measured by 1H NMR spectroscopic analysis of the corresponding Mosher ester prepared through sequential dihydroxylation-cleavage, reduction, and esterification.

Measured by chiral HPLC (OD-H column) after sequential acid hydrolysis, reduction, and derivatization to the corresponding p-bromobenzoate ester.

In order to explore the feasibility of this asymmetric cycloisomerization reaction with olefinic side-chains containing other than oxygen substituents, we examined substrates 12 and 13 (Table 2, entries 12 and 13) carrying carbon and nitrogen groups, respectively. Indeed, the reaction performs well in both instances and under similar conditions, leading to cycloisomerized products 12a (Table 2, entry 12, 93 % yield, > 98 % ee)[8] and 13a (Table 2, entry 13, 83 % yield, 94 % ee).

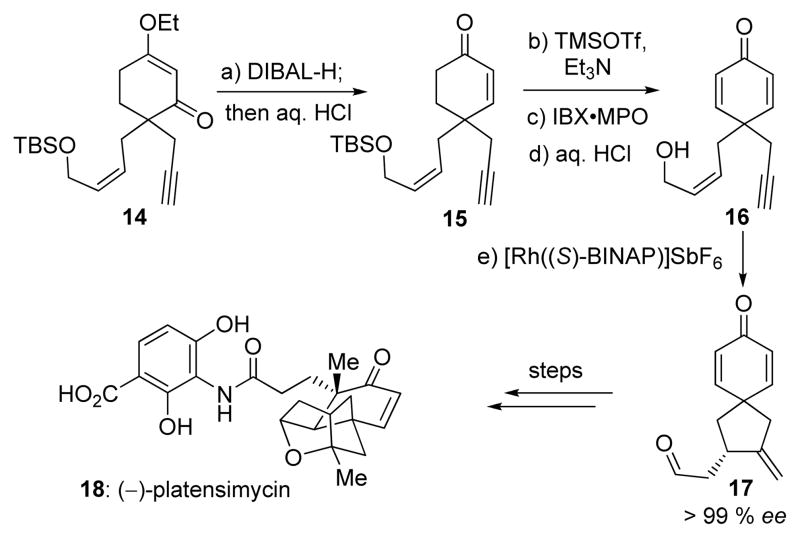

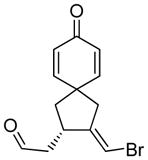

The power of the present technology was demonstrated by a formal total synthesis of (−)-platensimycin (18, Scheme 3) from 14, an intermediate previously employed in our synthesis of (±)-platensimycin.[9a] Thus, reduction of 14 with DIBAL-H at −78 °C followed by exposure to aq. HCl at 0 °C led to enone 15 in 88 % overall yield. Conversion of the latter to the corresponding TMS enol ether followed by oxidation with IBX•MPO[10] and desilylation (aq. HCl) furnished bis-enone hydroxy enyne 16 in 68 % overall yield. Delightfully, substrate 16 entered the asymmetric cycloisomerization with 5 mol % catalyst ([Rh((S)-BINAP)]SbF6) to afford the desired spiro dienone aldehyde (−)-17 in 86 % yield and > 99% ee. Notably, the use of the in situ generated catalyst (from [Rh(cod)Cl]2, AgSbF6 and (S)-BINAP) gave erratic results with 10–25 % yield of the desired product. Since (±)-17 and (−)-17 have previously been converted to (±)- and (−)-platensimycin,[9] respectively, this streamlined and highly efficient sequence constitutes a formal total synthesis of (−)-platensimycin (18).

Scheme 3.

Formal total synthesis of (−)-platensimycin. Reagents and conditions: a) DIBAL-H (1.0 M in hexanes, 1.2 equiv), THF, −78 → −20 °C, 1 h; then 2 N aq. HCl, 0 °C, 30 min, 88 %; b) TMSOTf (1.2 equiv), Et3N (1.5 equiv), CH2Cl2, 0 °C, 30 min; c) IBX (1.2 equiv), MPO (1.2 equiv), DMSO, 23 °C, 3 h; d) 1 N aq. HCl, THF, 0 °C, 1 h, 68 % over three steps; e) [Rh((S)-BINAP)]SbF6 (0.05 equiv), DCE, 23 °C, 12 h, 86 %, > 99 % ee. DIBAL-H = diisobutylaluminum hydride, DMSO = dimethyl sulfoxide, IBX = o-iodoxybenzoic acid, MPO = 4-methoxypyridine-N-oxide.

The described catalytic asymmetric synthesis complements and expands the scope of the cycloisomerization of 1,6-enynes by offering efficient and direct entries into enantiopure intermediates for complex natural or designed target molecules of biological and medical interest.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

We thank Drs. D. H. Huang, R. Chadha, and G. Siuzdak for NMR spectroscopic, X-ray crystallographic and mass spectrometric assistance, respectively. We also gratefully acknowledge A. Nold for assistance with chiral HPLC, and Dr. J. S. Chen for helpful discussions. Financial support was provided by a grant from the Skaggs Institute for Research, and graduate fellowships from Bristol-Myers Squibb and Eli Lilly (to A. L.), and Novartis (to S. P. E.)

Supporting information for this article is available on the WWW under http://www.angewandte.org or from the author.

References

- 1.a) Trost BM. Acc Chem Res. 1990;23:34–42. [Google Scholar]; b) Trost BM, Lautens M, Chan C, Jebaratnam DJ, Mueller T. J Am Chem Soc. 1991;113:636–644. [Google Scholar]; c) Hatano M, Mikami K. J Am Chem Soc. 2003;125:4704–4705. doi: 10.1021/ja0292748. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; d) Kressierer CJ, Müller TJJ. Angew Chem. 2004;116:6123–6127. [Google Scholar]; Angew Chem Int Ed. 2004;43:5997–6000. doi: 10.1002/anie.200461134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.a) Trost BM. Acc Chem Res. 2002;35:695–705. doi: 10.1021/ar010068z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Trost BM, Frederiksen MU, Rudd MT. Angew Chem. 2005;117:6788–6825. doi: 10.1002/anie.200500136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Angew Chem Int Ed. 2005;44:6630–6666. doi: 10.1002/anie.200500136. and references therein. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.a) Cao P, Wang B, Zhang X. J Am Chem Soc. 2000;122:6490–6491. [Google Scholar]; b) Cao P, Zhang X. Angew Chem. 2000;112:4270–4272. [Google Scholar]; Angew Chem Int Ed. 2000;39:4104–4106. doi: 10.1002/1521-3773(20001117)39:22<4104::aid-anie4104>3.0.co;2-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c) Lei A, He M, Wu S, Zhang X. Angew Chem. 2002;114:3607–3610. [Google Scholar]; Angew Chem Int Ed. 2002;41:3457–3460. doi: 10.1002/1521-3773(20020916)41:18<3457::AID-ANIE3457>3.0.CO;2-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; d) Lei A, Waldkirch JP, He M, Zhang X. Angew Chem. 2002;114:4708–4711. [Google Scholar]; Angew Chem Int Ed. 2002;41:4526–4529. doi: 10.1002/1521-3773(20021202)41:23<4526::AID-ANIE4526>3.0.CO;2-K. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; e) Lei A, He M, Zhang X. J Am Chem Soc. 2002;124:8198–8199. doi: 10.1021/ja020052j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; f) Lei A, He M, Zhang X. J Am Chem Soc. 2003;125:11472–11473. doi: 10.1021/ja0351950. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; g) Liu F, Liu Q, He M, Zhang X, Lei A. Org Bio Chem. 2007;5:3531–3534. doi: 10.1039/b712396e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.a) Fürstner A, Martin R, Majima K. J Am Chem Soc. 2005;127:12236–12237. doi: 10.1021/ja0532739. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Fürstner A, Majima K, Martin R, Krause H, Kattnig E, Goddard R, Lehmann CW. J Am Chem Soc. 2008;130:1992–2004. doi: 10.1021/ja0777180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wender PA, Haustedt LJ, Love JA, Williams TJ, Yoon JY. J Am Chem Soc. 2006;128:6302–6303. doi: 10.1021/ja058590u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.CCDC-723086 contains the supplementary crystallographic data of compound 1b. These data can be obtained free of charge at www.ccdc.cam.ac.uk/conts/retrieving.html (or from the Cambridge Crystallographic Data Centre, 12 Union Road, Cambridge CB2EZ, UK; fax: (+44) 1223–336–033; or deposit@ccdc.cam.ac.uk).

- 7.The 1H NMR spectrum of 2a revealed the presence of a minor component (ca. 14 %) which appeared to be the Z-enol ether isomer of 2a. 1H NMR (CDCl3, 600 MHz): 2a (E-isomer), δ = 6.28 (d, J = 12.0 Hz, 1 H), 4.63 (dd, J = 11.9, 9.3 Hz, 1 H); 2a' (Z-isomer), δ = 6.32 (dd, J = 5.7, 0.9 Hz, 1 H), 4.19 (dd, J = 8.4, 5.8 Hz, 1 H).

- 8.A closely related terminal alkynyl-ene substrate was reported in ref. 4d to undergo a rapid cyclization (< 5 min, 100% conversion) in the presence of a catalytic system generated in situ by sequential mixing of [Rh(cod)Cl]2, (S)-BINAP, substrate (1 min), and AgSbF6 in DCE at room temperature to afford a related product in poor enantioselectivity (i.e. 6.5 % ee, see experimental and footnote 14c in ref 4d). The key to the success of our protocol is the use of preformed, more well-defined catalyst [Rh ((S)-BINAP)]SbF6. The precise mechanistic differences between the two catalytic systems, however, remain to be elucidated, although the undefined nature of the catalytic species in ref. 4d and the slower reaction rates (12 – 16 h reaction times at room temperature) under our conditions may be important factors.

- 9.Nicolaou KC, Li A, Edmonds DJ. Angew Chem. 2006;118:7244–7248.Angew Chem Int Ed. 2006;45:7086–7090. doi: 10.1002/anie.200603892.Nicolaou KC, Edmonds DJ, Li A, Tria GS. Angew Chem. 2007;119:4016–4019. doi: 10.1002/anie.200700586.Angew Chem Int Ed. 2007;46:3942–3945. doi: 10.1002/anie.200700586.c) For reviews on the synthesis of platensimycin and related antibiotics, see: Nicolaou KC, Chen JS, Edmonds DJ, Estrada AA. Angew Chem. 2009;121:670–732. doi: 10.1002/anie.200801695.Angew Chem Int Ed. 2009;48:660–719. doi: 10.1002/anie.200801695.Tiefenbacher K, Mulzer J. Angew Chem. 2008;120:2582–2590.Angew Chem Int Ed. 2008;47:2548–2555. doi: 10.1002/anie.200705303.

- 10.Nicolaou KC, Gray DLF, Montagnon T, Harrison ST. Angew Chem. 2002;114:1038–1042. doi: 10.1002/1521-3773(20020315)41:6<996::aid-anie996>3.0.co;2-i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Angew Chem Int Ed. 2002;41:996–1000. doi: 10.1002/1521-3773(20020315)41:6<996::aid-anie996>3.0.co;2-i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.