Abstract

In the kidney, hypoxia contributes to tubulointerstitial fibrosis, but little is known about its implications for glomerular damage and glomerulosclerosis. Chronic hypoxia was hypothesized to be involved in nephrosclerosis (NSC) or “hypertensive nephropathy.” In the present study genome-wide expression data from microdissected glomeruli were studied to examine the role of hypoxia in glomerulosclerosis of human NSC. Functional annotation analysis revealed prominent regulation of hypoxia-associated biological processes in NSC, including angiogenesis, fibrosis, and inflammation. Glomerular expression levels of a majority of genes regulated by the hypoxia-inducible factors (HIFs) were significantly altered in NSC. Among these HIF targets, chemokine C-X-C motif receptor 4 (CXCR4) was prominently induced. Glomerular CXCR4 mRNA induction was confirmed by quantitative RT-PCR in an independent cohort with NSC but not in those with other glomerulopathies. By immunohistological analysis, CXCR4 showed enhanced positivity in podocytes in NSC biopsy specimens. This CXCR4 positivity was associated with nuclear localization of HIF1α only in podocytes of NSC, indicating transcriptional activity of HIF. As the CXCR4 ligand CXCL12/SDF-1 is constitutively expressed in podocytes, autocrine signaling may contribute to NSC. In addition, a blocking CXCR4 antibody caused significant inhibition of wound closure by podocytes in an in vitro scratch assay. These data support a role for CXCR4/CXCL12 in human NSC and indicate that hypoxia not only is involved in tubulointerstitial fibrosis but also contributes to glomerular damage in NSC.

Hypoxia is considered a pivotal factor contributing to tubular atrophy and interstitial fibrosis, which are factors for the progression of renal disease.1 The evidence in support of this hypothesis derives mostly from experimental animal studies.2,3,4,5 Most of these have focused on the tubulointerstitial space with little attention being paid to the glomerulus. The cellular response to hypoxia is largely mediated by heterodimeric transcription factors, the hypoxia-inducible factors (HIFs).2 The cellular levels of the HIF1α and HIF2α subunits (HIFα) of HIF (gene symbols HIF1A and HIF2A) are controlled mainly by post-translational protein modification. Under normoxia HIFα is degraded by the von Hippel-Lindau tumor suppressor protein. This process is regulated by oxygen-dependent hydroxylation of HIFα through specific prolyl hydroxylases. Under hypoxic conditions degradation of HIFα ceases and the stabilized protein can function as a transcription factor.2 In the renal glomerulus, a functional role of HIF1α6,7,8 and HIF2α9 has been documented in podocytes of rodents. Recently, glomerular podocyte-specific deletion of von Hippel-Lindau tumor suppressor protein was achieved in mice, resulting in podocyte-specific overactivity of HIF with induction of HIF target genes.6,8 Podocyte-specific HIF activation led to overexpression of chemokine (C-X-C motif) receptor 4 (CXCR4) in podocytes.8 This was associated with progressive glomerular damage and crescent formation, raising the question of whether hypoxia may also play a prominent role in glomerular pathology.8

The aim of the present study was to investigate the potential role of hypoxia in common glomerulopathies such as nephrosclerosis (NSC). NSC constitutes the second most common cause for end-stage renal disease in the Western world, next to diabetic nephropathy.10 NSC is also known under different synonyms such as hypertensive nephropathy or “benign” nephrosclerosis. The diagnosis of NSC is based on histological criteria including segmental hyalinosis mainly within the walls of afferent arterioles and subendothelial fibrosis of interlobular arteries, as well as focal and segmental glomerulosclerosis and glomerular collapse.11,12,13 The exclusion of other known causes of renal disease, such as long-standing diabetes mellitus, autoimmune disease, or exposure to nephrotoxins is part of the diagnostic work-up.14,15 Arterial hypertension is an important contributory factor but is not a conditio sine qua non.13,14,16 Genetic susceptibility factors may modulate development and progression of glomerular sclerosis. Recently, genetic variants such as single nucleotide polymorphisms in the gene MYH9, which encodes nonmuscle myosin heavy chain type II isoform A, were found to be associated with nondiabetic end-stage renal disease in African Americans, probably including a considerable number with NSC.17,18,19 Although the pathogenesis of NSC remains to be clearly defined, it has been hypothesized that a prominent pathomechanism in NSC may be glomerular ischemia due to luminal narrowing of the preglomerular arteriole.20,21

This situation prompted us to perform systematic analyses on gene expression data sets from microdissected human renal biopsy specimens from patients with NSC. We hypothesized that local hypoxia leading to transcriptional activity of HIF may play a key role in the development and progression of NSC. This activation of HIF target genes may influence, among others, three major processes involved in the progression of renal disease, ie, angiogenesis, fibrosis, and inflammation.1 This hypothesis is supported by the reported gene expression data, as a large number of known HIF target genes, including CXCR4, are induced in glomeruli from patients with NSC. HIF1α was selected as a marker of hypoxia-associated transcriptional activation and was demonstrated in nuclei of NSC podocytes by immunohistological analysis. These data and supporting in vitro studies provide considerable evidence that local hypoxia contributes to the progression of glomerulosclerosis in NSC.

Materials and Methods

Renal Biopsy Specimens for mRNA Analysis

Human renal biopsy specimens were procured in an international multicenter study, the European Renal cDNA Bank-Kröner-Fresenius biopsy bank (see Acknowledgments for participating centers).22 Biopsy specimens were obtained from patients after informed consent and with approval of local ethics committees. Affymetrix HG-U133A microarrays were hybridized with glomerular cDNA procured from 14 patients with NSC. Specific attention was paid to the clinical and histological criteria of NSC mentioned in the Introduction.11,12,13,14,15 For diagnosis of NSC, light microscopic and immunofluorescence examination was performed on all samples, and electron microscopic examination was performed on all but three biopsy specimens (NSC1, NSC2, and NSC18). Tumor-free kidney specimens from patients undergoing tumor nephrectomy (TN) served as control tissues. Confirmatory real-time RT-PCR analyses were performed on microdissected glomeruli from biopsy specimens from an independent cohort of patients with NSC (n = 13), primary focal segmental glomerulosclerosis (FSGS) (n = 18), IgA nephropathy (IgAN) n = 15), and minimal change disease (MCD) (n = 12). Pretransplant kidney biopsy specimens from living renal allograft donors (LDs) (n = 6) served as controls. Clinical and histological characteristics of the patients and biopsy specimens are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1.

Clinical and Histological Characteristics of Biopsy Specimens from Patients with NSC, FSGS, IgAN, and MCD and Controls

| Biopsy group | Number (method) | Sex | Age (years) | BP systolic (mmHg) | BP diastolic (mmHg) | Creatinine (mg/dl) | eGFR (ml/min) | Proteinuria (g/day) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nephrosclerosis | ||||||||

| NSC | NSC1 (A) | M | 47 | 145 | 90 | 2.58 | 29 | 2.30 |

| NSC | NSC2 (A) | M | 49 | 146 | 95 | 2.66 | 27 | NA |

| NSC | NSC4 (A) | M | 49 | 120 | 80 | 1.60 | 49 | 1.80 |

| NSC | NSC5 (A) | M | 57 | NA | NA | 2.40 | 30 | 0.10 |

| NSC | NSC6 (A) | M | 44 | 140 | 80 | 2.00 | 39 | 0.90 |

| NSC | NSC7 (A) | M | 63 | 120 | 80 | 2.00 | 36 | 0.20 |

| NSC | NSC8 (A) | M | 64 | 125 | 77 | 2.10 | 34 | 4.90 |

| NSC | NSC11 (A) | M | 77 | NA | NA | 7.46 | 8 | NA |

| NSC | NSC12 (A) | F | 55 | 150 | 90 | 0.74 | 87 | 0.20 |

| NSC | NSC13 (A) | F | 76 | 150 | 60 | 2.20 | 23 | 0.50 |

| NSC | NSC14 (A) | M | 47 | 175 | 105 | 3.60 | 19 | 3.39 |

| NSC | NSC15 (A) | M | 47 | 160 | 80 | 1.10 | 76 | NA |

| NSC | NSC16 (A) | M | 55 | 160 | 105 | 1.53 | 50 | NA |

| NSC | NSC18 (A) | F | 78 | 125 | 85 | 0.73 | 82 | NA |

| Mean ± SD | 58 ± 12 | 2.3 ± 1.7 | 42 ± 24 | 1.6 ± 1.7 | ||||

| Controls | ||||||||

| TN | TN1b (A) | F | 59 | NA | NA | 1 | 60 | no |

| TN | TN2b (A) | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| TN | TN3b (A) | F | 71 | NA | NA | 1 | 58 | no |

| TN | TN4b (A) | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| Mean ± SD | 65 ± 9 | 1.0 ± 0 | 59 ± 1 | no | ||||

| Nephrosclerosis | ||||||||

| NSC | NSC1 (P) | M | 40 | 120 | 80 | 1.00 | 88 | 1.50 |

| NSC | NSC2 (P) | M | 61 | 120 | 80 | 2.50 | 28 | 0.20 |

| NSC | NSC3 (P) | M | 43 | 150 | 100 | 2.20 | 35 | NA |

| NSC | NSC4 (P) | F | 47 | 150 | 90 | 1.50 | 40 | 3.30 |

| NSC | NSC5 (P) | M | 51 | 140 | 80 | 2.50 | 29 | 0.50 |

| NSC | NSC6 (P) | NA | NA | NA | NA | 5.00 | NA | 8.20 |

| NSC | NSC7 (P) | NA | NA | NA | NA | 1.10 | NA | 0.40 |

| NSC | NSC8 (P) | NA | NA | 170 | 80 | 1.40 | NA | NA |

| NSC | NSC9 (P) | M | 75 | 160 | 80 | 12.90 | 4 | NA |

| NSC | NSC10 (P) | M | 56 | 190 | 105 | 1.10 | 74 | NA |

| NSC | NSC11 (P) | M | 52 | 90 | 40 | 3.80 | 18 | 0.00 |

| NSC | NSC12 (P) | F | 52 | NA | NA | 0.80 | 80 | NA |

| NSC | NSC13 (P) | M | 59 | 133 | 79 | 4.60 | 14 | 0.00 |

| Mean ± SD | 54 ± 10 | 3.1 ± 3.3 | 41 ± 29 | 1.8 ± 2.8 | ||||

| Focal segmental glomerulosclerosis | ||||||||

| FSGS | FSGS1 (P) | M | 22 | 120 | 80 | 0.80 | 128 | 3.90 |

| FSGS | FSGS2 (P) | F | 55 | NA | NA | 0.80 | 79 | 8.40 |

| FSGS | FSGS3 (P) | F | 21 | 130 | 70 | 0.70 | 112 | 0.60 |

| FSGS | FSGS4 (P) | M | 32 | 125 | 70 | 0.80 | 119 | 5.50 |

| FSGS | FSGS5 (P) | F | 39 | 160 | 105 | 2.70 | 21 | 2.50 |

| FSGS | FSGS6 (P) | M | 37 | 145 | 95 | 2.00 | 40 | 8.80 |

| FSGS | FSGS7 (P) | M | 44 | 140 | 100 | 1.38 | 59 | 1.30 |

| FSGS | FSGS8 (P) | F | 63 | 160 | 85 | 1.30 | 44 | 3.99 |

| FSGS | FSGS9 (P) | F | 51 | 120 | 80 | 0.79 | 82 | 2.00 |

| FSGS | FSGS10 (P) | F | 55 | 130 | 80 | 0.60 | 110 | 1.90 |

| FSGS | FSGS11 (P) | M | 26 | 130 | 80 | 0.96 | 101 | 1.65 |

| FSGS | FSGS12 (P) | F | 32 | 120 | 75 | 0.69 | 105 | 0.66 |

| FSGS | FSGS13 (P) | M | 40 | 170 | 100 | 0.90 | 99 | 4.50 |

| FSGS | FSGS14 (P) | M | 53 | 120 | 80 | 1.20 | 67 | 7.00 |

| FSGS | FSGS15 (P) | F | 66 | NA | NA | 1.30 | 44 | 3.00 |

| FSGS | FSGS16 (P) | F | 31 | 160 | 93 | 1.00 | 69 | 6.00 |

| FSGS | FSGS17 (P) | F | 67 | 115 | 57 | 0.77 | 79 | 13.00 |

| FSGS | FSGS18 (P) | M | 23 | 110 | 81 | 0.97 | 102 | 3.00 |

| Mean ± SD | 42 ± 15 | 1.1 ± 0.5 | 81 ± 31 | 4.3 ± 3.3 | ||||

| Minimal change disease | ||||||||

| MCD | MCD1 (P) | M | 25 | 100 | 60 | 0.60 | 174 | 0.10 |

| MCD | MCD2 (P) | M | 20 | NA | NA | 1.60 | 59 | 2.00 |

| MCD | MCD3 (P) | F | 54 | 130 | 70 | 2.40 | 22 | 4.90 |

| MCD | MCD4 (P) | M | 46 | 137 | 82 | 1.38 | 59 | NA |

| MCD | MCD5 (P) | F | 52 | 118 | 69 | 0.60 | 112 | 6.50 |

| MCD | MCD6 (P) | M | 36 | 125 | 75 | 0.80 | 116 | 13.50 |

| MCD | MCD7 (P) | F | 19 | NA | NA | 0.68 | 118 | NA |

| MCD | MCD8 (P) | F | 45 | NA | NA | 0.54 | 130 | 14.80 |

| MCD | MCD9 (P) | F | 32 | 125 | 85 | 0.70 | 103 | 3.00 |

| MCD | MCD10 (P) | M | 16 | 135 | 100 | 1.20 | 84 | 5.40 |

| MCD | MCD11 (P) | F | 20 | 110 | 70 | 0.50 | 167 | 6.00 |

| MCD | MCD12 (P) | M | 32 | 150 | 90 | 1.30 | 68 | 11.00 |

| Mean ± SD | 33 ± 14 | 1.0 ± 0.6 | 101 ± 45 | 6.7 ± 4.9 | ||||

| IgA nephropathy | ||||||||

| IgAN | IgAN1 (P) | M | 35 | 130 | 80 | 1.40 | 61 | 0.30 |

| IgAN | IgAN2 (P) | F | 35 | 120 | 70 | 0.72 | 98 | 0.28 |

| IgAN | IgAN3 (P) | F | 22 | 120 | 70 | 0.90 | 83 | 0.70 |

| IgAN | IgAN4 (P) | F | 24 | 130 | 70 | 0.60 | 131 | 0.70 |

| IgAN | IgAN5 (P) | M | 51 | 120 | 75 | 0.80 | 108 | NA |

| IgAN | IgAN6 (P) | M | 35 | NA | NA | 1.31 | 66 | NA |

| IgAN | IgAN7 (P) | M | 31 | 150 | 100 | 1.10 | 83 | 3.00 |

| IgAN | IgAN8 (P) | M | 15 | 120 | 60 | 0.90 | 117 | 0.80 |

| IgAN | IgAN9 (P) | F | 33 | 120 | 80 | 1.50 | 43 | 0.49 |

| IgAN | IgAN10 (P) | M | 39 | NA | NA | 1.47 | 57 | 1.00 |

| IgAN | IgAN11 (P) | M | 19 | 140 | 70 | 0.79 | 134 | 4.00 |

| IgAN | IgAN12 (P) | M | 37 | 130 | 90 | 1.00 | 89 | 1.30 |

| IgAN | IgAN13 (P) | F | 50 | 160 | 90 | 0.90 | 70 | 1.92 |

| IgAN | IgAN14 (P) | M | 36 | 150 | 80 | 4.50 | 16 | 3.80 |

| IgAN | IgAN15 (P) | M | 49 | 160 | 90 | 0.90 | 95 | 10.00 |

| Mean ± SD | 34 ± 11 | 1.3 ± 0.9 | 83 ± 33 | 2.2 ± 2.7 | ||||

| Controls | ||||||||

| LD | LD1 (P) | F | 35 | NA | NA | <1.0 | >60 | no |

| LD | LD2 (P) | F | 56 | NA | NA | <1.0 | >60 | no |

| LD | LD3 (P) | M | 41 | NA | NA | <1.0 | >60 | no |

| LD | LD4 (P) | M | 62 | NA | NA | <1.0 | >60 | no |

| LD | LD5 (P) | M | 27 | NA | NA | <1.0 | >60 | no |

| LD | LD6 (P) | NA | NA | NA | NA | <1.0 | >60 | no |

| Mean ± SD | 44 ± 15 | <1.0 | >60 | no |

As controls we used tumor-free tissue from tumor nephrectomy specimens (TN) for the microarray experiments and biopsy specimens from living donor kidneys (LD) for the confirmational real-time RT-PCR experiments. Patients were analyzed by oligonucleotide array (A)-based gene expression profiling [NSC (A): n = 14, controls (TN): n = 4] and real-time RT-PCR (P) [NSC (P): n = 13, FSGS (P): n = 18, IgAN (P): n = 15, MCD (P): n = 12, controls (LD): n = 6]. The patients’ sex is given as male (M) or female (F). BP, blood pressure; eGFR, glomerular filtration rate (estimated according to the Modification of Diet in Renal Disease formula); NA, not available.

RNA Isolation, Preparation, and Microarray Experiments

After renal biopsy, the tissue was transferred to an RNase inhibitor and microdissected into glomerular and tubular specimens. Total RNA was isolated from microdissected glomeruli, reverse-transcribed, and linearly amplified according to a protocol reported previously.23 Fragmentation, hybridization, staining, and imaging were performed according to the Affymetrix Expression Analysis Technical Manual for HG-U133A. Before microarray analysis Robust Multichip Average was applied. To exclude highly variable nonexpressed or low-expressed probe sets we defined a filter cutoff using the highest signal value obtained from a nonhuman Affymetrix control probe set multiplied by a factor of 1.2, corresponding in the current data set to a log2-based value of 6.81.24 The expression data are made available online at http://www.nephromine.org. Subsequently we analyzed the differential expression with significance analysis of microarrays.25 The main results were also confirmed in a probe set-independent analysis (ChipInspector, Genomatix, Munich, Germany).26 In a further step, the probe sets of a group of selected genes above cutoff were hierarchically clustered using dChip software.27 The Euclidean distance metric was chosen, and clusters were merged using average linkage. Gene lists derived from the literature were mapped to the default Affymetrix annotation using Human Genome Organization gene symbols.

Analysis of Biological Processes

Database for Annotation, Visualization and Integrated Discovery (DAVID, version 2007) is a web- and literature-based functional annotation tool, which allows systematic grouping of biologically related genes from user-classified gene lists, thereby highlighting the most relevant Gene Ontology (GO) terms associated with a given gene list. The significance determination of GO terms in DAVID is based on the Expression Analysis Systematic Explorer, a variant of one-tailed Fisher exact probability.28 For DAVID analyses, a P value of 0.05 was used as standard cutoff level.

Immunohistological Analysis

HIF1α staining was performed on biopsy specimens from an independent group of 9 patients with NSC and 5 controls (healthy tissue from TN), and CXCR4 staining was performed on biopsy specimens from an independent group of 15 patients with NSC and 5 controls (TN). Costaining was done on biopsy samples from 2 patients with NSC (3 and 11 glomeruli), 2 controls (TN, >20 glomeruli), and 4 patients with FSGS (10 to 34 glomeruli), one of these with a documented NPHS2 mutation. The following antibodies were used: a rabbit polyclonal antibody to CXCR4 (ab2074, Abcam, Eching, Germany) and monoclonal IgG2b against HIF1α (NB 100-105, Novus Biologicals, Littleton, CO). For costaining, HIF was documented with the tyramide signal amplification system (TSATM Fluorescence System, NEN Life Science Products, Boston, MA). CXCR4 was then visualized by indirect immunofluorescence with an anti-rabbit antibody (AF488, 1:200, Invitrogen, Paisley, UK). Nuclei were stained by the DNA interactive agent DRAQ5TM (Alexis-Axxora, Lörrach, Germany). The staining shown is from a representative sample. The findings for CXCR4 and HIF1α staining in glomerular podocytes that we report were globally present but showed focal accentuation.

For chemokine (C-X-C motif) ligand 12 (CXCL12; also called SDF-1), immunohistochemical analysis was performed as described previously.29 The primary antibody was a mouse anti-human CXCL12 (clone 79018, R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN). Immunohistochemical analysis was performed on normal areas collected from TNs (n = 3) and biopsy specimens from patients with NSC (n = 3). Replacement of the primary antibody by diluent served as a negative control.

Cell Culture Experiments with Hypoxia

We used established cell lines of immortalized murine (K5P530) and human podocytes (A [h63]31 and B [AB81]32). K5P5, h63, and AB81 cells were cultured as given in the respective references. Normoxia was defined as 20% O2 in the gas phase, and hypoxia constituted 2.0 and 0.2% O2, respectively. For oxygen titration, cell cultures were distributed into incubators (Binder, Tuttlingen, Germany) with different oxygen concentrations (2.0 and 20% O2) or were placed in a hypoxia incubator (In Vivo2 Hypoxia Workstation 400, Ruskinn Technology, Guiseley, UK, flushed with gas [0.2% O2, 5% CO2, and 94.8% N2]) and simultaneously cultured for the indicated time periods. Cells were analyzed at 4 hours for HIF1α, at 24 hours for HIF2α Western blot analysis, and at 24 hours for mRNA expression analysis, respectively. Total cellular RNA was extracted using the Qiagen RNeasy kit (Qiagen, Hombrechtikon, Switzerland). The mRNA expression was analyzed by real-time RT-PCR.

Western Blot

For HIF1α detection, cultured glomerular epithelial cells30,32 were harvested with lysis buffer (10 mmol/L Tris-HCl [pH 8.0], 0.1% Nonidet P-40, 400 mmol/L NaCl, 1 mmol/L EDTA [pH 8.0], 1 mmol/L dithiothreitol, 1 mmol/L phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride, and Complete Protease Inhibitor Cocktail [Roche, Mannheim, Germany]). For HIF2α detection, glomerular epithelial cells30,32 were harvested with a lysis buffer containing 8 M urea (10 mmol/L Tris-HCl [pH 6.8], 1% SDS, 5 mmol/L dithiothreitol, 10% glycerol, 8 M urea, 0.5 mmol/L phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride, and Complete Protease Inhibitor Cocktail). The protein concentrations were determined by the Bradford method (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Hercules, CA). Extracted proteins were boiled in loading buffer for 5 minutes, resolved by 10% SDS-polyacrylamide gel electrophoreses under reducing conditions, and transferred to an Immobilon-P membrane (Millipore, Eschborn, Germany). Equal loading and transfer efficiencies were verified by staining with 2% Ponceau S. Membranes were blocked overnight with Tris-buffered saline/5% fat-free skim milk and then incubated with a monoclonal mouse antibody raised against human HIF1α (BD Transduction Laboratories, Lexington, KY) diluted 1:1000 overnight at 4°C and rinsed with Tris-buffered saline containing 0.1% Tween 20. Immunoblotting for HIF1α in murine podocytes was performed using polyclonal rabbit anti-HIF1α antibody (1:200, overnight at 4°C, Novus Biologicals). HIF2α was detected using a polyclonal rabbit anti-HIF2α antibody (1:200, overnight at 4°C, Novus Biologicals).

For detection, a horseradish peroxidase-linked anti-mouse IgG antibody (1:2000, 1 hour at room temperature, DAKO, Glostrup, Denmark) and enhanced chemiluminescence substrate (PerkinElmer Life and Analytical Sciences, Waltham, MA) were used. Membranes were also probed with anti-β-actin antibody (A 5316, 1:5000, Sigma-Aldrich, Munich, Germany) as an internal loading control.

In Vitro “Wound Healing” Assay

In confluent cell monolayers on collagen-coated six-well plates, a scratch (“wound”) was created with a sterile pipette tip. Cells were then incubated for 22 hours with either blocking rabbit anti-rat CXCR4 antibody (5 μg/ml, Torrey Pines Biolabs, East Orange, NJ), which has been shown to be effective in mice,8 or rabbit immunoglobulin IgG (5 μg/ml, R&D Systems). At 0 hours and after 22 hours, the width of the scratch was measured at the same 10 to 12 points per well in a blinded fashion (n = 12 for each condition). The extent of wound healing is given as a percentage of the original width (1 − mean of measured distances at 22 hours/mean of measured distances at 0 hours).

Quantitative Real-Time RT-PCR

For studies using biopsy samples, reverse transcription and real-time RT-PCR were performed as reported earlier.33 Predeveloped TaqMan reagents were used for human fibronectin 1 (FN1, NM_002026), human lysyl oxidase-like 2 (LOXL2, NM_002318.2), and the housekeeper genes 18S rRNA, GAPDH, and β-actin (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA). The following oligonucleotide primers (300 nmol/L) and probe (100 nmol/L) were used for human CXCR4 (NM_003467.2), sense primer 5′-GGCCGACCTCCTCTTTGTC-3′, antisense primer 5′-CAAAGTACCAGTTTGCCACGG-3′, and fluorescence labeled probe (FAM) 5′-ACGCTTCCCTTCTGGGCAGTTGATG-3′; and for CXCL12 (NM_199168), sense primer 5′-ACCGCGCTCTGCCTCA-3′, antisense primer 5′-CATGGCTTTCGAAGAATCGG-3′, and fluorescence labeled probe (FAM) 5′-TCAGCCTGAGCTACAGATGCCCATGC-3′. The expression of candidate genes was normalized to three reference genes, 18S rRNA, hGAPDH, and β-actin, giving similar results. Data shown are normalized to 18S rRNA, and target gene expression in the control cohort is set as 1. The mRNA expression was analyzed by standard curve quantification.

For in vitro studies, reverse transcription was performed as described above. Predeveloped TaqMan reagents were used for human CXCR4 (NM_003467.2) and for the reference gene 18S rRNA (Applied Biosystems). For human and murine vascular endothelial growth factor A (VEGFA and Vegfa, respectively) and murine Cxcr4, the following oligonucleotide primers (300 nmol/L) and probes (100 nmol/L) were used: for human VEGFA (NM_003376), sense primer 5′-GCCTTGCTGCTCTACCTCCAC-3′, antisense primer 5′-ATGATTCTGCCCTCCTCCTTCT-3′, and fluorescence labeled probe (FAM) 5′-AAGTGGTCCCAGGCTGCACCCAT-3′; for murine Vegfa (NM_001025250.3), sense primer 5′-GCTGTGCAGGCTGCTGTAAC-3′, antisense primer 5′-TGATGTTGCTCTCTGACGTGG-3′, and fluorescence labeled probe (FAM) 5′-ATGAAGCCCTGGAGTGCGTGCC-3′; and for murine Cxcr4 (NM_009911.3), sense primer 5′-TGGAACCGATCAGTGTGAGTATATA-3′, antisense primer 5′-GGTGGGCAGGAAGATCCTATT-3′, and fluorescence labeled probe (FAM) 5′-CTGCTTCCGGGATGAAAACGTCCATT-3′. The expression of candidate genes was normalized to 18S rRNA and analyzed by the ΔΔCt method.

Statistics

Experimental data are given as mean ± SD. Statistical analysis was performed using the Mann-Whitney U test and the Welch and Games-Howell test (SPSS 14.0, SPSS, Chicago, IL). P and q values <0.05 were considered to indicate statistically significant differences.

Results

Glomerular Expression of Hypoxia-Regulated Genes Is Altered in NSC

Gene expression profiling was performed on isolated glomeruli to study alterations in gene transcript expression in NSC. In choosing the cohort to be examined, specific attention was paid to the histological criteria of NSC and clinical features.11,12,13,14,15 The clinical characteristics of the patients are provided in Table 1. Glomerular gene expression profiles yielded 14,762 probe sets with expression intensities above cutoff (see Materials and Methods). We used unsupervised clustering to visualize the probe sets in a dendrogram. Cluster dendrograms sort samples with the most similar gene expression profiles together with the shortest branches. Clustering all 14,762 probe sets above cutoff resulted in clear segregation of NSC from TN (Supplemental Figure S1, see http://ajp.amjpathol.org). The comparison between controls and NSC resulted in 7,381 significantly altered probe sets (Supplemental Table S1, see http://ajp.amjpathol.org). These corresponded to roughly 5,711 genes, taking the limitations of the default Affymetrix probe set annotation into account.34

To test whether hypoxia-related biological processes previously reported to contribute to deterioration of renal function may be involved in NSC, the data were grouped according to their GO classification.1 The glomerular gene expression data demonstrated significant overrepresentation of GO terms of two biological processes potentially involved in hypoxia-related kidney damage: angiogenesis (eg, the GO terms “angiogenesis” [GO:0001525] and “vasculature development” [GO:0001944]) (Supplemental Table S2, see http://ajp.amjpathol.org) and inflammation (eg, GO terms “immune response” [GO:0006955] and “inflammatory response” [GO:0006954]) (Supplemental Table S3, see http://ajp.amjpathol.org). A third process, renal fibrosis, has recently been discussed as being controlled by HIF.1,3 Because a corresponding GO term does not exist, we used a literature-based list of genes potentially involved in renal fibrosis.35,36,37,38 Of 84 fibrosis-related genes derived from the literature, 83 were represented on the HG-U133A array. Of these, 73 genes showed mRNA expression above the cutoff in the expression array analysis of the glomeruli from NSC biopsy specimens. Of these, 42 (58%) were found to be significantly altered in NSC compared with controls (Supplemental Table S4, see http://ajp.amjpathol.org). In summary, GO analyses of the microarray data from glomeruli with NSC support the idea of hypoxia-associated processes being involved in the development of renal disease.

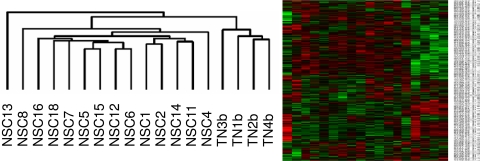

These initial results prompted us to further evaluate the potential role of hypoxia-regulated gene expression in glomeruli from NSC biopsy specimens. A literature-based list of previously reported HIF target genes was generated.39,40 From a total of 554 HIF target genes, 542 were represented on the HG-U133A array and 476 showed mRNA expression above cutoff. Expression of 290 (61%) of these genes was significantly altered in glomeruli with NSC compared with controls (Supplemental Table S5, see http://ajp.amjpathol.org). This number is higher than that observed in patients with FSGS, in whom expression of only 23% of the HIF target genes was found to be changed (n = 13, unpublished data). Because HIFα subunits are regulated mainly at the post-translational level, it was not surprising that HIF1A mRNA itself was not significantly altered in glomeruli with NSC (HIF1A, probe set 200989_at, fold change 0.96, NS). HIF2A mRNA was significantly increased (EPAS1, probe set 200879_s_at, fold change 1.25, q = 0.05 and 200878_at, fold change 1.57, q < 0.01). To further evaluate our hypothesis that hypoxia may play a significant pathophysiological role in NSC, we examined whether expression of HIF-regulated genes might segregate glomerular gene expression in NSC biopsy specimens from that in controls. We used unsupervised clustering to visualize the 476 HIF target genes above cutoff in a dendrogram. This cluster dendrogram of HIF target genes segregated NSC from controls with two distinct branches being identified: one corresponding to the NSC group and the other one to the TN control group (Figure 1). No association of HIF target gene expression with clinical parameters (renal function or proteinuria) or antihypertensive treatment with or without blockade of the renin angiotensin system was observed nor was there a correlation with the histological degree of glomerular scarring on this limited number of patients. Of 25 HIF targets with relevance to renal function, reported by Haase et al,5 20 genes showed mRNA expression above cutoff. Expression of 16 (80%) of these was significantly changed in glomeruli with NSC compared with controls (Table 2). Among the HIF targets, which were significantly more abundant in glomeruli with NSC (Table 2 and Supplemental Table S5, see http://ajp.amjpathol.org), we found genes representing prominent hypoxia-modulated biological processes such as angiogenesis, fibrosis, and inflammation. VEGFA and its receptor FMS-like tyrosine kinase 1 (FLT1), both with significantly increased transcript levels in glomeruli with NSC, are examples of genes involved in the first process. For early as well as late stages of fibrosis the following genes are prominent indicators: TIMP1 (tissue inhibitor of metalloproteinase 1), SERPINE1 (serpin peptidase inhibitor, clade E, member 1, also called plasminogen activator inhibitor type 1),4 LOX (lysyl oxidase), and LOXL2 (lysyl oxidase-like 2).3 Fibronectin (FN1) mRNA, also shown to be up-regulated under hypoxic conditions,41,42 was strongly increased in glomeruli with NSC. Furthermore, mRNA expression for several collagen α-chains was increased in NSC glomeruli, including the reportedly hypoxia-inducible genes COL1A2, COL4A1, and COL4A2.4,39 Interestingly, only the embryonic (COL4A1 and COL4A2) and not the mature isoforms of collagen type 4 (COL4A3, COL4A4, and COL4A5) were found to be significantly altered in NSC glomeruli (Supplemental Table S4, see http://ajp.amjpathol.org).43 Finally, among the above processes inflammation emerged as a prominent one in NSC (Supplemental Table S3, see http://ajp.amjpathol.org). In line with this finding, the chemokine receptor CXCR4 was one of the most strongly increased HIF target genes in NSC glomeruli.

Figure 1.

Cluster of HIF target genes in NSC. Unbiased and unsupervised clustering was used to visualize the expressed HIF target genes in a dendrogram. Cluster dendrograms group the patients with the most similar gene expression profiles. The length of the branches represents the dissimilarity. Probe set abundance is displayed on a red-green color scale, with red indicating expression above and green below the mean. This cluster dendrogram uses the HIF target genes to segregate NSC from the healthy controls. Two distinct branches could be identified: one corresponding to the NSC group and the other one to the TN group.

Table 2.

Regulation of HIF Target Genes with Relevance to Renal Function

| Probe set | Gene symbol (HUGO) | Gene name (from Affymetrix HG-U133A-20080318) | Fold change | q value (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 200966_x_at | ALDOA | Aldolase A, fructose-bisphosphate | 1.12 | 4.87 |

| 214687_x_at | ALDOA | Aldolase A, fructose-bisphosphate | 1.13 | 2.27 |

| 201849_at | BNIP3 | BCL2/adenovirus E1B 19kDa interacting protein 3 | 0.74 | 0.73 |

| 201848_s_at | BNIP3 | BCL2/adenovirus E1B 19kDa interacting protein 3 | 0.80 | 4.87 |

| 205199_at | CA9 | Carbonic anhydrase IX | 0.83 | 0.88 |

| 211919_s_at | CXCR4 | Chemokine (C-X-C motif) receptor 4 | 2.37 | 0.08 |

| 209201_x_at | CXCR4 | Chemokine (C-X-C motif) receptor 4 | 2.41 | 0.03 |

| 217028_at | CXCR4 | Chemokine (C-X-C motif) receptor 4 | 4.23 | 0.03 |

| 209101_at | CTGF | Connective tissue growth factor | 0.88 | 18.58 |

| 218995_s_at | EDN1 | Endothelin 1 | 0.94 | 22.72 |

| 201231_s_at | ENO1 | Enolase 1, (alpha) | 0.89 | 19.75 |

| 217294_s_at | ENO1 | Enolase 1, (alpha) | 1.21 | 4.87 |

| 217254_s_at | EPO | Erythropoietin | BC | BC |

| 207257_at | EPO | Erythropoietin | BC | BC |

| 222033_s_at | FLT1 | Fms-related tyrosine kinase 1 | 1.74 | 0.03 |

| 210287_s_at | FLT1 | Fms-related tyrosine kinase 1 | BC | BC |

| 204406_at | FLT1 | Fms-related tyrosine kinase 1 | BC | BC |

| 203665_at | HMOX1 | Heme oxygenase (decycling) 1 | 0.57 | 0.73 |

| 202934_at | HK2 | Hexokinase 2 | 1.33 | 4.87 |

| 222305_at | HK2 | Hexokinase 2 | BC | BC |

| 205302_at | IGFBP1 | Insulin-like growth factor binding protein 1 | BC | BC |

| 200650_s_at | LDHA | Lactate dehydrogenase A | BC | BC |

| 203510_at | MET | Met proto-oncogene | 0.62 | 0.73 |

| 211599_x_at | MET | Met proto-oncogene | 0.84 | 1.58 |

| 213807_x_at | MET | Met proto-oncogene | 0.84 | 0.73 |

| 213816_s_at | MET | Met proto-oncogene | BC | BC |

| 209957_s_at | NPPA | Natriuretic peptide precursor A | 0.78 | 0.06 |

| 210037_s_at | NOS2A | Nitric oxide synthase 2A | BC | BC |

| 205581_s_at | NOS3 | Nitric oxide synthase 3 | BC | BC |

| 200738_s_at | PGK1 | Phosphoglycerate kinase 1 | 1.03 | 19.75 |

| 200737_at | PGK1 | Phosphoglycerate kinase 1 | 1.18 | 4.87 |

| 217383_at | PGK1 | Phosphoglycerate kinase 1 | 1.24 | 4.87 |

| 217356_s_at | PGK1 | Phosphoglycerate kinase 1 | BC | BC |

| 200725_x_at | RPL10 | Ribosomal protein L10 | 1.05 | 10.75 |

| 200724_at | RPL10 | Ribosomal protein L10 | 1.09 | 10.75 |

| 221989_at | RPL10 | Ribosomal protein L10 | 1.33 | 1.58 |

| 217680_x_at | RPL10 | Ribosomal protein L10 | BC | BC |

| 202628_s_at | SERPINE1 | Serpin peptidase inhibitor | 1.20 | 8.92 |

| 202627_s_at | SERPINE1 | Serpin peptidase inhibitor, clade E | 1.26 | 1.14 |

| 201250_s_at | SLC2A1 | Solute carrier family 2, member 1 | 0.76 | 0.07 |

| 201249_at | SLC2A1 | Solute carrier family 2, member 1 | BC | BC |

| 201666_at | TIMP1 | TIMP metallopeptidase inhibitor 1 | 1.65 | 0.10 |

| 214064_at | TF | Transferrin | BC | BC |

| 214063_s_at | TF | Transferrin | BC | BC |

| 203400_s_at | TF | Transferrin | BC | BC |

| 220109_at | TF | Transferrin | BC | BC |

| 208691_at | TFRC | Transferrin receptor /// transferrin receptor | 0.81 | 10.75 |

| 207332_s_at | TFRC | Transferrin receptor /// transferrin receptor | 0.85 | 12.73 |

| 210512_s_at | VEGFA | Vascular endothelial growth factor | 1.06 | 17.38 |

| 212171_x_at | VEGFA | Vascular endothelial growth factor | 1.11 | 14.49 |

| 211527_x_at | VEGFA | Vascular endothelial growth factor | 1.31 | 4.87 |

| 210513_s_at | VEGFA | Vascular endothelial growth factor | 1.38 | 0.06 |

Twenty-five of 25 selected HIF targets with relevance to renal function derived from the literature were represented on the HG-U133A array. Twenty of these genes showed mRNA expression above cutoff on the arrays. Of these 20 expressed mRNAs, 16 (80%) were significantly regulated in glomeruli from NSC biopsy samples compared with controls (TN).5 The fold change indicates the expression of each gene in nephrosclerosis (NSC) glomeruli compared with controls, ie, a fold change of 1.75 refers to an induction of 75% in NSC. BC, below cutoff, see Materials and Methods for further detail.

Glomerular Induction of CXCR4 mRNA Is Found in NSC, but Not in Other Common Glomerulopathies

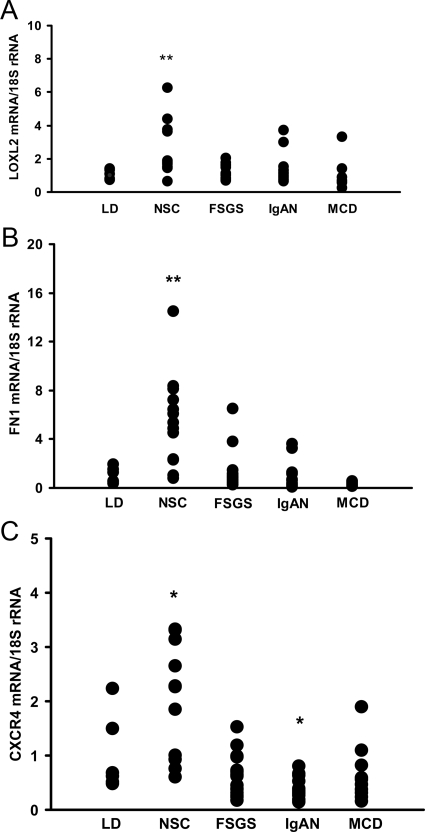

From the above-mentioned significantly altered HIF target genes we selected LOXL2, FN1, and CXCR4 for further confirmatory analysis. The glomerular mRNA expression was determined by real-time RT-PCR in an independent cohort of patients with NSC and patients with other glomerulopathies such as FSGS, IgAN, and MCD. Pretransplant allograft biopsy specimens from LDs served as healthy controls (Table 1). A significant induction of LOXL2 mRNA (2.6 ± 1.7-fold, P < 0.01) and FN1 mRNA (5.5 ± 3.7-fold, P < 0.01) was found in glomeruli with NSC compared with controls. LOXL2 and FN1 mRNA were not found to be consistently induced in glomeruli from patients with FSGS, IgAN, and MCD (LOXL2: FSGS 1.1 ± 0.4, NS, IgAN 1.4 ± 0.9, NS, and MCD 0.9 ± 1.0, NS, compared with controls; FN1: FSGS 1.2 ± 1.6, NS, IgAN 0.9 ± 1.1, MS, and MCD 0.3 ± 0.2, NS, compared with controls) (Figure 2, A and B). The mRNA for CXCR4, one of the most strongly altered HIF target templates in our microarray data set, was also found to be induced in glomeruli of an independent cohort of patients with NSC, but not in those with FSGS, MCD, or IgAN (NSC 2.0 ± 1.1, P < 0.05; FSGS 0.6 ± 0.4, NS; IgAN 0.4 ± 0.2, P < 0.05; and MCD 0.6 ± 0.5, NS, compared with controls) (Figure 2C). Expression of the known ligand of CXCR4, ie, CXCL12, was not found to be significantly altered in the glomerular microarray data. This result was again confirmed by real-time RT-PCR, which demonstrated only a nonsignificant trend for CXCL12 mRNA induction in NSC (NSC 3.9 ± 4.8, NS; FSGS 1.4 ± 1.5, NS; IgAN 0.9 ± 0.9, NS; and MCD 1.8 ± 1.9, NS). In summary, the real-time RT-PCR studies on independent patient cohorts supported the microarray data and confirmed the glomerular induction of LOXL2, FN1, and CXCR4 mRNA seen on the microarray as potential contributors to hypoxia-induced pathomechanisms in NSC.

Figure 2.

Confirmation of LOXL2, FN1, and CXCR4 mRNA expression in glomeruli with NSC and controls. A: LOXL2 mRNA measured by RT-PCR is induced in glomeruli from NSC biopsy specimens. LOXL2 mRNA showed increased expression by quantitative RT-PCR in glomeruli from an independent group of NSC biopsy specimens (n = 13). Values were normalized to pretransplant LD control biopsy specimens (n = 6) and the housekeeper gene 18S rRNA. In FSGS, IgAN, and MCD, LOXL2 mRNA was not significantly different compared with that in living donor (LD) controls. **P < 0.01 compared with controls. B: FN1 mRNA is overexpressed in glomeruli from NSC biopsy specimens. Same biopsy cohorts as mentioned in A. **P < 0.01 compared with controls (LD). C: CXCR4 mRNA expression levels are higher in glomeruli from NSC biopsy specimens. Same biopsy cohorts as mentioned in A. *P < 0.05 compared with controls (LD). FSGS, focal segmental glomerusclerosis; IgAN, IgA nephropathy; MCD, minimal change disease.

HIF1α Shows Nuclear Localization in CXCR4-Positive Podocytes of NSC Biopsy Specimens

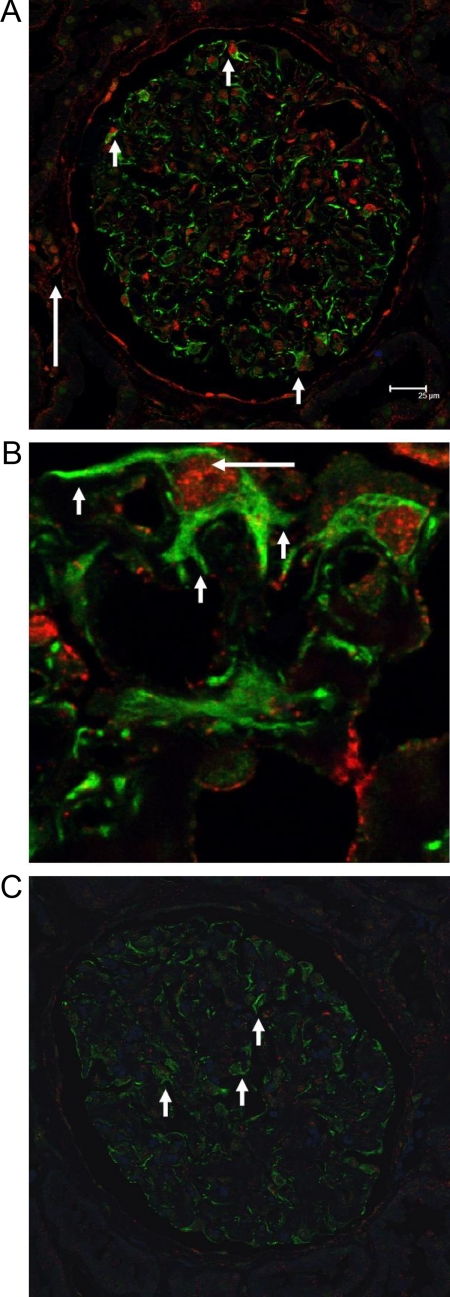

To demonstrate the glomerular cell type expressing CXCR4 in NSC, immunohistological analysis was performed on additional biopsy specimens to further study the expression of CXCR4. In NSC biopsy specimens, the CXCR4 protein could be localized to glomerular epithelial cells in all glomeruli with a prominent increase in fluorescence intensity compared with the faint staining for CXCR4 in control kidneys (Figure 3, A–C). As was expected, interstitial mononuclear cells also stained positive for CXCR4 (not shown).

Figure 3.

CXCR4 and HIF1α staining in NSC and controls. A: CXCR4 and HIF1α staining in glomeruli with NSC. CXCR4 (green staining) and HIF1α (red staining) showed robust expression in podocytes of NSC (short arrows). As expected some tubular epithelial cells stained positive for HIF1α (long arrow). Interstitial mononuclear cells also stained positive for CXCR4 (not shown). B: High magnification of CXCR4 and HIF1α staining in NSC. Higher magnification of glomerular epithelial cells with surface staining for CXCR4 (short arrows) and nuclear staining for HIF1α (long arrow). C: CXCR4 and HIF1α staining in glomeruli from controls. Healthy tissue from TN served as a control, with podocytes showing a faint green CXCR4 background staining (arrows) without any HIF1α positivity.

To evaluate whether the CXCR4 protein expression in podocytes of NSC biopsy specimens was associated with HIF1α activation as a general marker of hypoxia-associated transcriptional activation, double staining for both molecules was performed. A faint cytoplasmic staining for HIF1α was occasionally seen in cells of control biopsy specimens. In marked contrast, a robust nuclear HIF1α staining was apparent in podocytes from NSC biopsy specimens and colocalized with staining for CXCR4 (Figure 3, A and B). Because HIF1α is translocated from the cytosol to the nucleus on activation, the localization may indicate transcriptional activity of HIF in these cells.5 Occasionally tubular epithelial cells showed also a nuclear staining pattern for HIF1α. These cells demonstrated no concomitant CXCR4 staining. In biopsy specimens from patients with the main diagnosis of FSGS, glomerular epithelial cells stained also positive for CXCR4 but with a restrained and heterogeneous nuclear HIF1α positivity. This result is in line with the microarray data reported above, which indicate a more pronounced hypoxia-associated gene regulation in NSC glomeruli than in FSGS glomeruli.

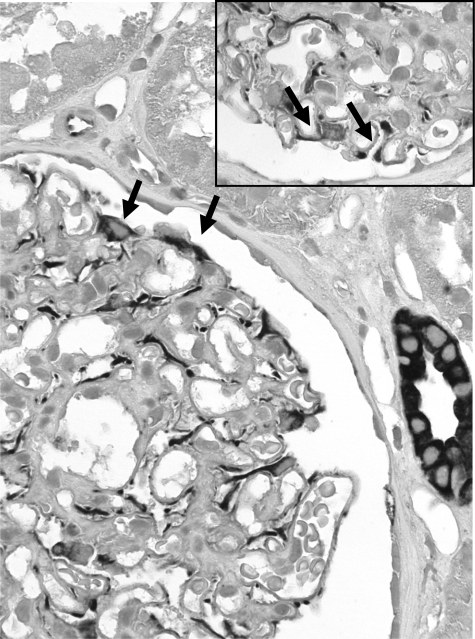

CXCL12, the corresponding ligand of CXCR4, was also found to be expressed in podocytes of NSC biopsy specimens as well as in control tissue (Figure 4). In addition, CXCL12 expression was seen on some tubular epithelial cells and on endothelial cells of larger veins and arteries. The constitutive expression was consistent with the mRNA expression data, indicating no CXCL12 mRNA induction in NSC.

Figure 4.

CXCL12 staining in glomeruli with NSC. CXCL12 was localized by immunohistochemical analysis in biopsy specimens from patients with NSC and controls. A prominent CXCL12 expression was found, in a pattern consistent with podocytes. Note the staining of cells on the outer surface of the glomerular basement membrane (arrows). Original magnification, ×400. Inset: Higher magnification of CXCL12 staining of glomeruli with NSC confirmed expression by podocytes (arrows). Original magnification, ×1000.

Hypoxia Induces HIFα Protein and CXCR4 mRNA in Podocytes in Vitro

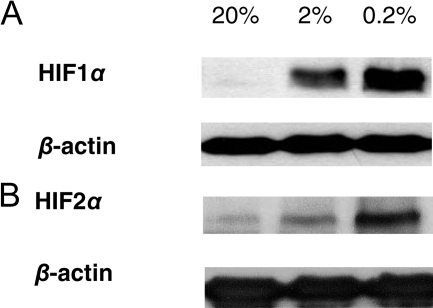

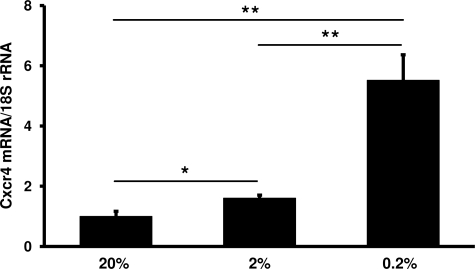

CXCR4 and nuclear HIF1α colocalized to podocytes in double immunofluorescence staining. We therefore studied podocytes in vitro to define whether this might represent a functional association. We exposed podocyte cell lines30,31,32 to hypoxic culture conditions. By Western blot, we were able to demonstrate higher HIF1α and HIF2α protein levels under graded hypoxic conditions compared with normoxic controls (see Figure 5, A and B,32 for human podocytes; murine podocytes not shown). Hypoxic incubation conditions (0.2% and 2% oxygen) resulted in a significant increase in CXCR4/Cxcr4 mRNA in all podocyte cell lines tested compared with 20% oxygen concentration (Figure 6, Table 3). VEGFA/Vegfa mRNA served as a positive control for a hypoxia-induced genes and also showed an induction under hypoxic conditions (Table 3).

Figure 5.

Hypoxia induces HIF1α and HIF2α protein in cultured podocytes. A: By Western blot a dose-dependent induction of HIF1α under graded hypoxic conditions (0.2 and 2% O2) was demonstrated in human podocytes32 compared with normoxic time controls (20% O2, at 4 hours). B: In addition, HIF2α was found to be stabilized in human podocytes at 0.2 and 2% O2 compared with 20% O2 (at 24 hours). β-Actin was used as loading control.

Figure 6.

Hypoxia induces Cxcr4 mRNA in podocytes in vitro. In cultured murine podocytes, expression of Cxcr4 mRNA was increased after 24 hours at 0.2% O2 compared with podocytes incubated at 2% O2 after 24 hours and normoxic (20% O2) controls (n = 4 each). *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, significant differences compared with 20% O2. **P < 0.01, significant difference comparing 0.2 with 2% O2. For expression data of CXCR4 and VEGFA in human podocyte cell lines exposed to hypoxia, see Table 3.

Table 3.

Cxcr4/CXCR4 and Vegfa/VEGFA mRNA Expression under Hypoxic Conditions

| 20% O2 | 2% O2 | 0.2% O2 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| VegFa/VEGFA | |||

| Murine podocytes | 1.00 ± 0.04 | 1.22 ± 0.08* | 2.21 ± 0.41*‡ |

| Human podocytes A | 1.00 ± 0.36 | 3.35 ± 1.70 (NS) | 11.97 ± 1.35‡§ |

| Human podocytes B | 1.00 ± 0.11 | 1.36 ± 0.31* | 2.23 ± 0.67†‡ |

| Cxcr4/CXCR4 | |||

| Murine podocytes | 1.00 ± 0.17 | 1.60 ± 0.10* | 5.52 ± 0.85‡§ |

| Human podocytes A | 1.00 ± 0.17 | 9.98 ± 3.29* | 19.16 ± 3.56†‡ |

| Human podocytes B | 1.00 ± 0.30 | 1.29 ± 0.35 (NS) | 4.41 ± 1.67‡§ |

Expression of Cxcr4/CXCR4 and Vegfa/VEGFA mRNA in cultured murine (K5P5) and human podocytes (podocytes A [h63] and podocytes B [AB81]) after incubation for 24 hours at 0.2 and 2% O2 compared with 20% O2 (n = 4 each for K5P5 and h63 and n = 8 for AB81).

P < 0.05, significant difference compared with 20% O2.

P < 0.05, significant difference comparing 0.2 with 2% O2.

P < 0.01, significant difference compared with 20% O2.

P < 0.01, significant difference comparing 0.2 with 2% O2.

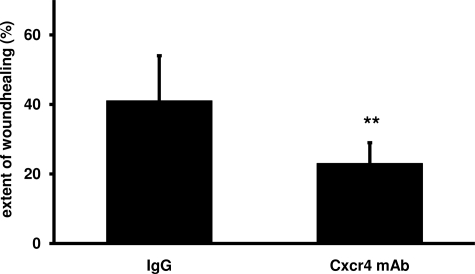

As CXCR4 and CXCL12 were both found to be expressed by podocytes, we set out to study a functional role of this receptor/ligand system. Because CXCR4 is known to play a role in guidance of cell migration, we applied an in vitro scratch assay on cultured podocytes. In line with a functional relevance of CXCR4/CXCL12 in podocyte biology, a blocking CXCR4 antibody significantly impaired the extent of wound closure in these cells compared with control IgG (23 ± 6% versus 41 ± 13%, P < 0.01, n = 12 each) (Figure 7).

Figure 7.

CXCR4 blockade reduces podocyte migration in vitro in a wound-healing assay. To assess potential functions of CXCR4 in podocyte migration, a wound-healing assay was performed. Confluent murine podocytes (K5P5) were treated with either blocking anti-CXCR4 antibody or immunoglobulin IgG as control. At 0 hours and after 22 hours, the width of each scratch inflicted at 0 hours was measured in a blinded fashion. The CXCR4 antibody significantly impaired the extent of wound closure compared with controls (23 ± 6 versus 41 ± 13%, **P < 0.01, n = 12 each). mAb, monoclonal antibody.

Discussion

The growing evidence for hypoxia as a modulator of progression of renal disease prompted us to examine its potential role in human NSC.1 NSC represents an entity with a poorly understood pathogenesis, even though it is reported to be the second most common cause for end-stage renal disease in the Western world.10 We found hypoxia-related genes to be clearly induced in glomeruli from patients with NSC. CXCR4, a known target of HIF, was significantly induced in NSC and could be localized to podocytes together with positive nuclear staining for HIF1α as a general indicator for hypoxia-associated transcriptional activity.

The hypothesis-driven analysis of the gene expression data was focused on genes known to be regulated by HIF.5,39,40 Consistent with the hypothesis that hypoxia is an important factor in NSC, the majority of known HIF target genes were significantly altered in glomeruli from NSC biopsy specimens and segregated them from controls in the unsupervised cluster analysis. Prominent biological processes modulated by hypoxia are angiogenesis, fibrosis, and inflammation. In angiogenesis, VEGFA and its receptor FLT1, both significantly increased in NSC, play a central role (Table 2). VEGFA is an important growth, survival, and repair factor for glomerular capillaries. The induction of VEGFA in the glomeruli of the NSC cohort is consistent with previously reported expression of VEGF mRNA in podocytes in NSC44 and induction of VEGFA mRNA in cultured podocytes under hypoxia (Table 3). The finding of glomerular VEGFA and FLT1 induction in NSC biopsy specimens is in contrast to the reduced expression of VEGFA recently reported in human diabetic nephropathy both in glomeruli and in the tubulointerstitial compartment, indicating a different pathophysiological mechanism for glomerulosclerosis in NSC and diabetic nephropathy.33,45 HIF target genes involved in the accumulation of extracellular matrix and fibrosis were also found to be induced in glomeruli with NSC. This finding was confirmed by RT-PCR for FN1, for which HIF-independent regulatory mechanisms are also described,46 and for LOXL2. LOX, and LOXL2 are documented examples of genes involved in matrix remodeling by cross-linking of collagen fibers. They were recently reported to be induced in a murine model of hypoxia-induced tubulointerstitial fibrosis.3 Tubulointerstitial LOXL2 mRNA was also found to be induced in various progressive human renal diseases including NSC.3 Our present data showing increased LOXL2 expression in glomeruli with NSC but not other glomerulopathies may indicate that this hypoxia-inducible enzyme is not only involved in progressive interstitial fibrosis but may also play a role in glomerulosclerosis in NSC. Besides these collagen-associated molecules increased mRNA expression for several collagen α-chains, the known HIF target genes COL1A2, COL4A1, and COL4A2, was prominent in the NSC data set.39 We observed significant increases only for the fetal isoforms of collagen type 4, ie, COL4A1 and COL4A2, whereas the mature isoforms COL4A3, COL4A4, and COL4A5 were not found to be significantly regulated (Supplemental Table S4, see http://ajp.amjpathol.org). The expression of these fetal collagen isoforms resembles that seen in Alport syndrome, in which it has been related to a potentially more vulnerable glomerular basement membrane composition ultimately leading to glomerulosclerosis.43,47 Such re-expression of fetal collagen genes in glomeruli from adult patients with NSC may be part of an increased cellular plasticity (see below).

Inflammation is another biological process closely linked to hypoxia and to progression of renal disease.1,48 The complex interplay between hypoxia and the immune system is nicely illustrated by the example of nuclear factor-κB, a master switch in the inflammatory response: HIF1α has been shown to activate nuclear factor-κB and nuclear factor-κB itself is a transcriptional activator of HIF1α.48,49 Indeed, inflammatory gene signatures were significantly altered in NSC glomeruli (Supplemental Table S3, see http://ajp.amjpathol.org) including major histocompatibility class I and II genes, interleukins, and chemokines. Although glomerular inflammatory cell infiltrates have been observed in NSC,50 they are not a prominent feature of glomerular NSC.11,12 In addition, it should be noted that the expression of “inflammatory” genes cannot be directly equated with inflammatory infiltrates, as some of these genes could be regulated on intrinsic glomerular cells, for which our observations with CXCR4 on podocytes may serve as example.

Among the HIF target genes involved in inflammation, the chemokine receptor CXCR4 was found to be prominently induced in NSC glomeruli. Interestingly, induction of CXCR4 mRNA was not seen by RT-PCR in other glomerulopathies such as FSGS, IgAN, or MCD. For IgAN and membranous nephropathy, the absence of prominent CXCR4 expression in glomeruli had been reported previously.8,51 Although FSGS is characterized by glomerular sclerosis similar to NSC, CXCR4 mRNA was not consistently induced in glomeruli from biopsy specimens of patients with primary FSGS. Although immunohistological analysis also revealed CXCR4 positivity of podocytes in FSGS biopsy specimens, the nuclear HIF1α staining in these biopsy specimens seemed restrained and heterogeneous. In this context, it should be noted that CXCR4 transcriptional regulation also includes HIF- and hypoxia-independent mechanisms.52,53,54 In FSGS, the primary pathology may be of direct glomerular origin whereas narrowing of the afferent blood vessels with consecutive glomerular hypoxia may be a central mechanism in NSC. Nuclear HIF1α in podocytes of NSC biopsy specimens can be seen as a biological indicator for hypoxia-associated transcriptional processes. Because nuclear HIF1α was associated with CXCR4 expression in podocytes of NSC biopsy specimens, we went on to study CXCR4 expression in podocytes in vitro. In cultured human and murine podocytes, we found a low but constitutive expression of CXCR4/Cxcr4, as was also reported by Huber et al.51 Hypoxia in vitro stabilized HIF1α and HIF2α protein and induced CXCR4/Cxcr4 mRNA expression in podocytes. In our experiments we used HIF1α as a global biological marker of hypoxia. However, HIF2α has been shown to be of specific functional relevance in podocytes.9 Although providing clear evidence for an activation of hypoxia-associated transcriptional programs in podocytes, our descriptive data do not elucidate which HIFα subunit or mechanism is mainly regulating CXCR4 in podocytes. However, induction of CXCR4 by hypoxia has been reported for several cell types, such as monocytes, macrophages, endothelial cells, cancer cells, and stem/progenitor cells.52,55,56,57 Von Hippel-Lindau tumor suppressor protein/HIF-dependent regulation of Cxcr4 on podocytes in vivo was elegantly demonstrated in a study by Ding et al8 in mice with genetically engineered deletion of von Hippel-Lindau tumor suppressor protein in podocytes, leading to glomerular epithelial cell proliferation and extracapillary crescent formation. In this model, interference with CXCR4 signaling prevented the proliferation of the epithelial cells and markedly improved the course of the experimental disease.8

Recently, CXCR4 expression on some glomerular parietal epithelial cells of Bowman’s capsule has been reported. These parietal cells also express markers for progenitor cells as well as for podocytes.58,59,60 In general, CXCR4 is expressed on stem cells and is involved in their recruitment to sites of tissue regeneration.61,62,63 Potentially, such podocyte precursors of glomerular parietal epithelial cell origin may be involved in the repopulation of the glomerular tuft during podocyte injury.58,59,60,64 CXCR4/CXCL12 guide cell migration in a number of systems (eg, renal morphogenesis (tubulogenesis), neuron/axon development, and tumor metastasis65,66,67,68). Using an in vitro wound healing assay to evaluate CXCR4-dependent migration, we could demonstrate that treatment of cultured podocytes with a blocking CXCR4 antibody significantly impaired in vitro wound healing and hence CXCR4-dependent cell migration. Potentially, these in vitro data indicate that in vivo CXCR4 is involved in the migration of podocytes during hypoxic injury such as that occurring in NSC. Supporting this observation, we found CXCL12 to be expressed in podocytes in adults, as has been recently reported in the developing murine kidney.8,69 CXCL12 was also reported to be expressed by mesangial cells in the developing human70 and murine glomerulus.8 Future studies on the expression of CXCL12 and CXCR4 during glomerular development and disease should provide further insight into the respective roles and interplay of both molecules in the glomerulus.

Finally, the neo-expression of CXCR4 on podocytes in NSC could reflect a change of differentiation of these epithelial cells re-expressing developmental genes. Although considerable controversy exists in the literature, cellular plasticity has been reported for renal cells.71 Tubular cells may change their differentiation during hypoxia,3,72 and podocytes have also been reported to be capable of undergoing changes of differentiation in vitro.73,74 We found potential markers for a change of differentiation in the microarray gene expression analysis of glomeruli from NSC, eg, down-regulation of the epithelial marker keratin 1 (q < 0.01) and up-regulation of the mesenchymal markers S100 calcium binding protein A4 (q < 0.01) and smooth muscle actin, α2 (q < 0.01) (Supplemental Table S1, see http://ajp.amjpathol.org). These observations could point to a role of hypoxia for potential plasticity in podocyte differentiation.

In summary, our data provide evidence for prominent hypoxia-regulated gene expression in glomeruli from human renal biopsy specimens from patients with NSC. This includes biological processes known to be involved in renal damage such as fibrosis and inflammation. Furthermore, our data indicate a reactivation of developmental processes, pointing to considerable plasticity of podocytes during hypoxic glomerular damage. Our observations expand evidence for the contribution of hypoxia from the previously documented role in interstitial fibrosis and tubular damage to that of glomerular sclerosis in NSC.

Acknowledgments

We thank Claudia Schmidt, Stefanie Gaiser, and Sylke Rohrer for excellent technical assistance. We are indebted to Anissa Boucherot, Almut Nitsche, Bodo Brunner (Sanofi-Aventis Deutschland GmbH, Frankfurt, Germany), and Anna Henger (University of Michigan).

We thank all participating centers of the European Renal cDNA Bank-Kroener-Fresenius biopsy bank and their patients for their cooperation. Active members at the time of the study were Clemens David Cohen, Holger Schmid, Michael Fischereder, Lutz Weber, Matthias Kretzler, and Detlef Schlöndorff, Munich/Zurich/Ann Arbor/New York; Jean Daniel Sraer and Pierre Ronco, Paris; Maria Pia Rastaldi and Giuseppe D’Amico, Milan; Peter Doran and Hugh Brady, Dublin; Detlev Mönks and Christoph Wanner, Würzburg; Andrew Rees, Aberdeen; Frank Strutz and Gerhard Anton Müller, Göttingen; Peter Mertens and Jürgen Floege, Aachen; Norbert Braun and Teut Risler, Tübingen; Loreto Gesualdo and Francesco Paolo Schena, Bari; Jens Gerth and Gunter Wolf, Jena; Rainer Oberbauer and Dontscho Kerjaschki, Vienna; Bernhard Banas and Bernhard Krämer, Regensburg; Moin Saleem, Bristol; Rudolf Wüthrich, Zurich; Walter Samtleben, Munich; Harm Peters and Hans-Hellmut Neumayer, Berlin; Mohamed Daha, Leiden; Katrin Ivens and Bernd Grabensee, Düsseldorf; Francisco Mampaso (deceased), Madrid; Jun Oh, Franz Schaefer, Martin Zeier, and Hermann-Joseph Gröne, Heidelberg; Peter Gross, Dresden; Giancarlo Tonolo, Sassari; Vladimir Tesar, Prague; Harald Rupprecht, Bayreuth; and Hans-Peter Marti, Bern.

Footnotes

Address reprint requests to Clemens D. Cohen, M.D., Institute of Physiology and Division of Nephrology, University and University Hospital of Zurich, Winterthurerstr. 190 (23-J-74), 8057 Zurich, Switzerland. E-mail: clemens.cohen@access.uzh.ch.

Supported by the Else Kröner-Fresenius Foundation (A62/04 to C.D.C.) and the Swiss National Science Foundation (32-122439/1 to C.D.C.) and in part by the National Institutes of Health (National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases R01-DK081420-01 to D.S.) and the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (SFB405-B10 to H.-J.G.).

M.A.N., M.T.L., and A.G.M., contributed equally to this work.

Supplemental material for this article can be found on http://ajp.amjpathol.org.

References

- Fine LG, Norman JT. Chronic hypoxia as a mechanism of progression of chronic kidney diseases: from hypothesis to novel therapeutics. Kidney Int. 2008;74:867–872. doi: 10.1038/ki.2008.350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haase VH. The VHL/HIF oxygen-sensing pathway and its relevance to kidney disease. Kidney Int. 2006;69:1302–1307. doi: 10.1038/sj.ki.5000221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Higgins DF, Kimura K, Bernhardt WM, Shrimanker N, Akai Y, Hohenstein B, Saito Y, Johnson RS, Kretzler M, Cohen CD, Eckardt KU, Iwano M, Haase VH. Hypoxia promotes fibrogenesis in vivo via HIF-1 stimulation of epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition. J Clin Invest. 2007;117:3810–3820. doi: 10.1172/JCI30487. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Higgins DF, Kimura K, Iwano M, Haase VH. Hypoxia-inducible factor signaling in the development of tissue fibrosis. Cell Cycle. 2008;7:1128–1132. doi: 10.4161/cc.7.9.5804. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haase VH. Hypoxia-inducible factors in the kidney. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2006;291:F271–F281. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00071.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brukamp K, Jim B, Moeller MJ, Haase VH. Hypoxia and podocyte-specific Vhlh deletion confer risk of glomerular disease. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2007;293:F1397–F1407. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00133.2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freeburg PB, Robert B, St John PL, Abrahamson DR. Podocyte expression of hypoxia-inducible factor (HIF)-1 and HIF-2 during glomerular development. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2003;14:927–938. doi: 10.1097/01.asn.0000059308.82322.4f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ding M, Cui S, Li C, Jothy S, Haase V, Steer BM, Marsden PA, Pippin J, Shankland S, Rastaldi MP, Cohen CD, Kretzler M, Quaggin SE. Loss of the tumor suppressor Vhlh leads to upregulation of Cxcr4 and rapidly progressive glomerulonephritis in mice. Nat Med. 2006;12:1081–1087. doi: 10.1038/nm1460. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosenberger C, Mandriota S, Jurgensen JS, Wiesener MS, Horstrup JH, Frei U, Ratcliffe PJ, Maxwell PH, Bachmann S, Eckardt KU. Expression of hypoxia-inducible factor-1α and -2α in hypoxic and ischemic rat kidneys. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2002;13:1721–1732. doi: 10.1097/01.asn.0000017223.49823.2a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Renal Data System Bethesda, MD: National Institutes of Health, National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases; USRDS 2008 Annual Data ReportAtlas of Chronic Kidney Disease and End-Stage Renal Disease in the United States. 2008 [Google Scholar]

- Tisher CC, Brenner BM. Benign and malignant nephrosclerosis and renovascular disease. Philadelphia: Lippincott,; 1994:pp 1202–1203. [Google Scholar]

- Churg J, Sobin LH. Renal Disease: Benign nephrosclerosis. Tokyo: Igaku-Shoin,; Classification and Atlas of Glomerular Diseases. 1982:pp 211–224. [Google Scholar]

- Marcantoni C, Fogo AB. A perspective on arterionephrosclerosis: from pathology to potential pathogenesis. J Nephrol. 2007;20:518–524. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fogo A, Breyer JA, Smith MC, Cleveland WH, Agodoa L, Kirk KA, Glassock R. Accuracy of the diagnosis of hypertensive nephrosclerosis in African Americans: a report from the African American Study of Kidney Disease (AASK) Trial. AASK Pilot Study Investigators. Kidney Int. 1997;51:244–252. doi: 10.1038/ki.1997.29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schlessinger SD, Tankersley MR, Curtis JJ. Clinical documentation of end-stage renal disease due to hypertension. Am J Kidney Dis. 1994;23:655–660. doi: 10.1016/s0272-6386(12)70275-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marcantoni C, Ma LJ, Federspiel C, Fogo AB. Hypertensive nephrosclerosis in African Americans versus Caucasians. Kidney Int. 2002;62:172–180. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1755.2002.00420.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freedman BI, Sedor JR. Hypertension-associated kidney disease: perhaps no more. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2008;19:2047–2051. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2008060621. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kopp JB, Smith MW, Nelson GW, Johnson RC, Freedman BI, Bowden DW, Oleksyk T, McKenzie LM, Kajiyama H, Ahuja TS, Berns JS, Briggs W, Cho ME, Dart RA, Kimmel PL, Korbet SM, Michel DM, Mokrzycki MH, Schelling JR, Simon E, Trachtman H, Vlahov D, Winkler CA. MYH9 is a major-effect risk gene for focal segmental glomerulosclerosis. Nat Genet. 2008;40:1175–1184. doi: 10.1038/ng.226. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kao WH, Klag MJ, Meoni LA, Reich D, Berthier-Schaad Y, Li M, Coresh J, Patterson N, Tandon A, Powe NR, Fink NE, Sadler JH, Weir MR, Abboud HE, Adler SG, Divers J, Iyengar SK, Freedman BI, Kimmel PL, Knowler WC, Kohn OF, Kramp K, Leehey DJ, Nicholas SB, Pahl MV, Schelling JR, Sedor JR, Thornley-Brown D, Winkler CA, Smith MW, Parekh RS. MYH9 is associated with nondiabetic end-stage renal disease in African Americans. Nat Genet. 2008;40:1185–1192. doi: 10.1038/ng.232. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freedman BI, Iskandar SS, Appel RG. The link between hypertension and nephrosclerosis. Am J Kidney Dis. 1995;25:207–221. doi: 10.1016/0272-6386(95)90001-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang PX, Sanders PW. Mechanism of hypertensive nephropathy in the Dahl/Rapp rat: a primary disorder of vascular smooth muscle. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2005;288:F236–F242. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00213.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen CD, Frach K, Schlondorff D, Kretzler M. Quantitative gene expression analysis in renal biopsies: a novel protocol for a high-throughput multicenter application. Kidney Int. 2002;61:133–140. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1755.2002.00113.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen CD, Klingenhoff A, Boucherot A, Nitsche A, Henger A, Brunner B, Schmid H, Merkle M, Saleem MA, Koller KP, Werner T, Grone HJ, Nelson PJ, Kretzler M. Comparative promoter analysis allows de novo identification of specialized cell junction-associated proteins. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2006;103:5682–5687. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0511257103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmid H, Boucherot A, Yasuda Y, Henger A, Brunner B, Eichinger F, Nitsche A, Kiss E, Bleich M, Grone HJ, Nelson PJ, Schlondorff D, Cohen CD, Kretzler M. Modular activation of nuclear factor-κB transcriptional programs in human diabetic nephropathy. Diabetes. 2006;55:2993–3003. doi: 10.2337/db06-0477. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tusher VG, Tibshirani R, Chu G. Significance analysis of microarrays applied to the ionizing radiation response. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2001;98:5116–5121. doi: 10.1073/pnas.091062498. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen CD, Lindenmeyer MT, Eichinger F, Hahn A, Seifert M, Moll AG, Schmid H, Kiss E, Grone E, Grone HJ, Kretzler M, Werner T, Nelson PJ. Improved elucidation of biological processes linked to diabetic nephropathy by single probe-based microarray data analysis. PLoS One. 2008;3:e2937. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0002937. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li C, Wong WH. Model-based analysis of oligonucleotide arrays: expression index computation and outlier detection. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2001;98:31–36. doi: 10.1073/pnas.011404098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hosack DA, Dennis G, Jr, Sherman BT, Lane HC, Lempicki RA. Identifying biological themes within lists of genes with EASE. Genome Biol. 2003;4:R70. doi: 10.1186/gb-2003-4-10-r70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Segerer S, Heller F, Lindenmeyer MT, Schmid H, Cohen CD, Draganovici D, Mandelbaum J, Nelson PJ, Grone HJ, Grone EF, Figel AM, Nossner E, Schlondorff D. Compartment specific expression of dendritic cell markers in human glomerulonephritis. Kidney Int. 2008;74:37–46. doi: 10.1038/ki.2008.99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mundel P, Reiser J, Zuniga Mejia, Borja A, Pavenstadt H, Davidson GR, Kriz W, Zeller R. Rearrangements of the cytoskeleton and cell contacts induce process formation during differentiation of conditionally immortalized mouse podocyte cell lines. Exp Cell Res. 1997;236:248–258. doi: 10.1006/excr.1997.3739. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Delarue F, Virone A, Hagege J, Lacave R, Peraldi MN, Adida C, Rondeau E, Feunteun J, Sraer JD. Stable cell line of T-SV40 immortalized human glomerular visceral epithelial cells. Kidney Int. 1991;40:906–912. doi: 10.1038/ki.1991.292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saleem MA, O'Hare MJ, Reiser J, Coward RJ, Inward CD, Farren T, Xing CY, Ni L, Mathieson PW, Mundel P. A conditionally immortalized human podocyte cell line demonstrating nephrin and podocin expression. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2002;13:630–638. doi: 10.1681/ASN.V133630. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lindenmeyer MT, Kretzler M, Boucherot A, Berra S, Yasuda Y, Henger A, Eichinger F, Gaiser S, Schmid H, Rastaldi MP, Schrier RW, Schlondorff D, Cohen CD. Interstitial vascular rarefaction and reduced VEGF-A expression in human diabetic nephropathy. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2007;18:1765–1776. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2006121304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moll AG, Lindenmeyer MT, Kretzler M, Nelson PJ, Zimmer R, Cohen CD. Transcript-specific expression profiles derived from sequence-based analysis of standard microarrays. PLoS One. 2009;4:e4702. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0004702. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Catania JM, Chen G, Parrish AR. Role of matrix metalloproteinases in renal pathophysiologies. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2007;292:F905–F911. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00421.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eddy AA. Molecular basis of renal fibrosis. Pediatr Nephrol. 2000;15:290–301. doi: 10.1007/s004670000461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eikmans M, Baelde JJ, de Heer E, Bruijn JA. ECM homeostasis in renal diseases: a genomic approach. J Pathol. 2003;200:526–536. doi: 10.1002/path.1417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zeisberg M, Strutz F, Muller GA. Renal fibrosis: an update. Curr Opin Nephrol Hypertens. 2001;10:315–320. doi: 10.1097/00041552-200105000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manalo DJ, Rowan A, Lavoie T, Natarajan L, Kelly BD, Ye SQ, Garcia JG, Semenza GL. Transcriptional regulation of vascular endothelial cell responses to hypoxia by HIF-1. Blood. 2005;105:659–669. doi: 10.1182/blood-2004-07-2958. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wenger RH, Stiehl DP, Camenisch G. Integration of oxygen signaling at the consensus HRE. Sci STKE. 2005;2005:re12. doi: 10.1126/stke.3062005re12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Milner R, Hung S, Erokwu B, Dore-Duffy P, LaManna JC, del Zoppo GJ. Increased expression of fibronectin and the α5β1 integrin in angiogenic cerebral blood vessels of mice subject to hypobaric hypoxia. Mol Cell Neurosci. 2008;38:43–52. doi: 10.1016/j.mcn.2008.01.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Distler JH, Jungel A, Pileckyte M, Zwerina J, Michel BA, Gay RE, Kowal-Bielecka O, Matucci-Cerinic M, Schett G, Marti HH, Gay S, Distler O. Hypoxia-induced increase in the production of extracellular matrix proteins in systemic sclerosis. Arthritis Rheum. 2007;56:4203–4215. doi: 10.1002/art.23074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hudson BG, Tryggvason K, Sundaramoorthy M, Neilson EG. Alport’s syndrome. Goodpasture’s syndrome, and type IV collagen, N Engl J Med. 2003;348:2543–2556. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra022296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gröne HJ, Simon M, Gröne EF. Expression of vascular endothelial growth factor in renal vascular disease and renal allografts. J Pathol. 1995;177:259–267. doi: 10.1002/path.1711770308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baelde HJ, Eikmans M, Lappin DW, Doran PP, Hohenadel D, Brinkkoetter PT, van der Woude FJ, Waldherr R, Rabelink TJ, de Heer E, Bruijn JA. Reduction of VEGF-A and CTGF expression in diabetic nephropathy is associated with podocyte loss. Kidney Int. 2007;71:637–645. doi: 10.1038/sj.ki.5002101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bluyssen HA, Lolkema MP, van Beest M, Boone M, Snijckers CM, Los M, Gebbink MF, Braam B, Holstege FC, Giles RH, Voest EE. Fibronectin is a hypoxia-independent target of the tumor suppressor VHL. FEBS Lett. 2004;556:137–142. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(03)01392-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gubler MC. Inherited diseases of the glomerular basement membrane. Nat Clin Pract Nephrol. 2008;4:24–37. doi: 10.1038/ncpneph0671. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rius J, Guma M, Schachtrup C, Akassoglou K, Zinkernagel AS, Nizet V, Johnson RS, Haddad GG, Karin M. NF-κB links innate immunity to the hypoxic response through transcriptional regulation of HIF-1α. Nature. 2008;453:807–811. doi: 10.1038/nature06905. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walmsley SR, Print C, Farahi N, Peyssonnaux C, Johnson RS, Cramer T, Sobolewski A, Condliffe AM, Cowburn AS, Johnson N, Chilvers ER. Hypoxia-induced neutrophil survival is mediated by HIF-1α-dependent NF-κB activity. J Exp Med. 2005;201:105–115. doi: 10.1084/jem.20040624. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Imakiire T, Kikuchi Y, Yamada M, Kushiyama T, Higashi K, Hyodo N, Yamamoto K, Oda T, Suzuki S, Miura S. Effects of renin-angiotensin system blockade on macrophage infiltration in patients with hypertensive nephrosclerosis. Hypertens Res. 2007;30:635–642. doi: 10.1291/hypres.30.635. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huber TB, Reinhardt HC, Exner M, Burger JA, Kerjaschki D, Saleem MA, Pavenstadt H. Expression of functional CCR and CXCR chemokine receptors in podocytes. J Immunol. 2002;168:6244–6252. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.168.12.6244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Staller P, Sulitkova J, Lisztwan J, Moch H, Oakeley EJ, Krek W. Chemokine receptor CXCR4 downregulated by von Hippel-Lindau tumour suppressor pVHL. Nature. 2003;425:307–311. doi: 10.1038/nature01874. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mori T, Kim J, Yamano T, Takeuchi H, Huang S, Umetani N, Koyanagi K, Hoon DS. Epigenetic up-regulation of C-C chemokine receptor 7 and C-X-C chemokine receptor 4 expression in melanoma cells. Cancer Res. 2005;65:1800–1807. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-3531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mehta SA, Christopherson KW, Bhat-Nakshatri P, Goulet RJ, Jr, Broxmeyer HE, Kopelovich L, Nakshatri H. Negative regulation of chemokine receptor CXCR4 by tumor suppressor p53 in breast cancer cells: implications of p53 mutation or isoform expression on breast cancer cell invasion. Oncogene. 2007;26:3329–3337. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1210120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schioppa T, Uranchimeg B, Saccani A, Biswas SK, Doni A, Rapisarda A, Bernasconi S, Saccani S, Nebuloni M, Vago L, Mantovani A, Melillo G, Sica A. Regulation of the chemokine receptor CXCR4 by hypoxia. J Exp Med. 2003;198:1391–1402. doi: 10.1084/jem.20030267. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zagzag D, Krishnamachary B, Yee H, Okuyama H, Chiriboga L, Ali MA, Melamed J, Semenza GL. Stromal cell-derived factor-1α and CXCR4 expression in hemangioblastoma and clear cell-renal cell carcinoma: von Hippel-Lindau loss-of-function induces expression of a ligand and its receptor. Cancer Res. 2005;65:6178–6188. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-4406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hung SC, Pochampally RR, Hsu SC, Sanchez C, Chen SC, Spees J, Prockop DJ. Short-term exposure of multipotent stromal cells to low oxygen increases their expression of CX3CR1 and CXCR4 and their engraftment in vivo. PLoS ONE. 2007;2:e416. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0000416. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sagrinati C, Netti GS, Mazzinghi B, Lazzeri E, Liotta F, Frosali F, Ronconi E, Meini C, Gacci M, Squecco R, Carini M, Gesualdo L, Francini F, Maggi E, Annunziato F, Lasagni L, Serio M, Romagnani S, Romagnani P. Isolation and characterization of multipotent progenitor cells from the Bowman’s capsule of adult human kidneys. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2006;17:2443–2456. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2006010089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ronconi E, Sagrinati C, Angelotti ML, Lazzeri E, Mazzinghi B, Ballerini L, Parente E, Becherucci F, Gacci M, Carini M, Maggi E, Serio M, Vannelli GB, Lasagni L, Romagnani S, Romagnani P. Regeneration of glomerular podocytes by human renal progenitors. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2009;20:322–332. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2008070709. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mazzinghi B, Ronconi E, Lazzeri E, Sagrinati C, Ballerini L, Angelotti ML, Parente E, Mancina R, Netti GS, Becherucci F, Gacci M, Carini M, Gesualdo L, Rotondi M, Maggi E, Lasagni L, Serio M, Romagnani S, Romagnani P. Essential but differential role for CXCR4 and CXCR7 in the therapeutic homing of human renal progenitor cells. J Exp Med. 2008;205:479–490. doi: 10.1084/jem.20071903. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ceradini DJ, Kulkarni AR, Callaghan MJ, Tepper OM, Bastidas N, Kleinman ME, Capla JM, Galiano RD, Levine JP, Gurtner GC. Progenitor cell trafficking is regulated by hypoxic gradients through HIF-1 induction of SDF-1. Nat Med. 2004;10:858–864. doi: 10.1038/nm1075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lapidot T, Kollet O. The essential roles of the chemokine SDF-1 and its receptor CXCR4 in human stem cell homing and repopulation of transplanted immune-deficient NOD/SCID and NOD/SCID/B2mnull mice. Leukemia. 2002;16:1992–2003. doi: 10.1038/sj.leu.2402684. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ceradini DJ, Gurtner GC. Homing to hypoxia: hIF-1 as a mediator of progenitor cell recruitment to injured tissue. Trends Cardiovasc Med. 2005;15:57–63. doi: 10.1016/j.tcm.2005.02.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Appel D, Kershaw DB, Smeets B, Yuan G, Fuss A, Frye B, Elger M, Kriz W, Floege J, Moeller MJ. Recruitment of podocytes from glomerular parietal epithelial cells. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2009;20:333–343. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2008070795. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ueland J, Yuan A, Marlier A, Gallagher AR, Karihaloo A. A novel role for the chemokine receptor Cxcr4 in kidney morphogenesis: an in vitro study. Dev Dyn. 2009;238:1083–1091. doi: 10.1002/dvdy.21943. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baudouin SJ, Pujol F, Nicot A, Kitabgi P, Boudin H. Dendrite-selective redistribution of the chemokine receptor CXCR4 following agonist stimulation. Mol Cell Neurosci. 2006;33:160–169. doi: 10.1016/j.mcn.2006.07.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Onoue T, Uchida D, Begum NM, Tomizuka Y, Yoshida H, Sato M. Epithelial-mesenchymal transition induced by the stromal cell-derived factor-1/CXCR4 system in oral squamous cell carcinoma cells. Int J Oncol. 2006;29:1133–1138. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pujol F, Kitabgi P, Boudin H. The chemokine SDF-1 differentially regulates axonal elongation and branching in hippocampal neurons. J Cell Sci. 2005;118:1071–1080. doi: 10.1242/jcs.01694. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takabatake Y, Sugiyama T, Kohara H, Matsusaka T, Kurihara H, Koni PA, Nagasawa Y, Hamano T, Matsui I, Kawada N, Imai E, Nagasawa T, Rakugi H, Isaka Y. The CXCL12 (SDF-1)/CXCR4 axis is essential for the development of renal vasculature. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2009;20:1714–1723. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2008060640. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gröne HJ, Cohen CD, Gröne E, Schmidt C, Kretzler M, Schlondorff D, Nelson PJ. Spatial and temporally restricted expression of chemokines and chemokine receptors in the developing human kidney. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2002;13:957–967. doi: 10.1681/ASN.V134957. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaissling B, Le Hir M. The renal cortical interstitium: morphological and functional aspects. Histochem Cell Biol. 2008;130:247–262. doi: 10.1007/s00418-008-0452-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neilson EG. Mechanisms of disease: fibroblasts—a new look at an old problem. Nat Clin Pract Nephrol. 2006;2:101–108. doi: 10.1038/ncpneph0093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Y, Kang YS, Dai C, Kiss LP, Wen X, Liu Y. Epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition is a potential pathway leading to podocyte dysfunction and proteinuria. Am J Pathol. 2008;172:299–308. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2008.070057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sam R, Wanna L, Gudehithlu KP, Garber SL, Dunea G, Arruda JA, Singh AK. Glomerular epithelial cells transform to myofibroblasts: early but not late removal of TGF-β1 reverses transformation. Transl Res. 2006;148:142–148. doi: 10.1016/j.trsl.2006.04.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]