Abstract

Timelapse video microscopy has been used to record the motility and dynamic interactions between an H-2Db-restricted murine cytotoxic T lymphocyte clone (F5) and Db-transfected L929 mouse fibroblasts (LDb) presenting normal or variant antigenic peptides from human influenza nucleoprotein. F5 cells will kill LDb target cells presenting specific antigen (peptide NP68: ASNENMDAM) after “browsing” their surfaces for between 8 min and many hours. Cell death is characterized by abrupt cellular rounding followed by zeiosis (vigorous “boiling” of the cytoplasm and blebbing of the plasma membrane) for 10–20 min, with subsequent cessation of all activity. Departure of cytotoxic T lymphocytes from unkilled target cells is rare, whereas serial killing is sometimes observed. In the absence of antigenic peptide, cytotoxic T lymphocytes browse target cells for much shorter periods, and readily leave to encounter other targets, while never causing target cell death. Two variant antigenic peptides, differing in nonamer position 7 or 8, also act as antigens, albeit with lower efficiency. A third variant peptide NP34 (ASNENMETM), which differs from NP68 in both positions and yet still binds Db, does not stimulate F5 cytotoxicity. Nevertheless, timelapse video analysis shows that NP34 leads to a significant modification of cell behavior, by up-regulating F5–LDb adhesive interactions. These data extend recent studies showing that partial agonists may elicit a subset of the T cell responses associated with full antigen stimulation, by demonstrating that TCR interaction with variant peptide antigens can trigger target cell adhesion and surface exploration without activating the signaling pathway that results in cytotoxicity.

There is increasing evidence that the interaction of antigenic peptides bound to molecules of the major histocompatibility complex (MHC) on the surface of an antigen presenting cell (APC) with T cell antigen receptors (TCRs) on a T lymphocyte, previously thought of as a simple specific binding event leading to full T cell activation, is in fact subtly graded, capable of eliciting a variety of responses according to the specificity of peptide binding and the dissociation rate of the TCR from the peptide–MHC complex (pMHC) (1–5). Studies with cytotoxic T cells have shown that variant peptides may elicit cytotoxicity without inducing TCR down-regulation, cytokine production and proliferation (6), or alternatively may antagonize those responses elicited by the true antigen (7–9).

True antigens bound to the appropriate class I MHCs elicit cytotoxicity of the APCs by cytotoxic T lymphocytes (CTLs). For example, the Db-restricted CTL clone F5 will kill target cells presenting a nonamer antigenic peptide from human influenza virus nucleoprotein (NP) of the 1968 strain A/HK/8/68 (residues 366–374: ASNENMDAM; peptide NP68), while being unable to kill the same target cells presenting the homologous peptide from the 1934 strain A/PR/8/34 (ASNENMETM; peptide NP34), although both peptides are bound to Db with similar affinities (10–13).

After antigen recognition, the CTL undergoes extensive morphological and physiological changes that facilitate killing of the target cell, including membrane and cytoskeletal remodeling, and flattening against the target cell to form a temporary synapse across which the cytotoxic interactions are mediated (14–17). Sanderson (14), using timelapse cinematography, was among the first to observe that target cell death occurred a variable time after initial CTL contact, but that when it did occur it was rapid, being characterized by a vigorous “boiling” of the cytoplasm and blebbing of the entire plasma membrane, a phenomenon termed zeiosis (from ζɛω (zeio), meaning “I boil or seethe”) (18), which today we associate with apoptotic death.

In this study we have sought, by direct cellular observation using timelapse video microscopy, to determine the behavioral effects on F5 CTLs of sequence variations of antigenic peptides presented by fibroblast target cells. Specifically, we have analyzed and quantified the nature and duration of cell–cell interactions resulting when F5 cells encounter fibroblasts presenting either NP68 or NP34 peptides. We find that NP34, although unable to elicit a cytotoxic response, is nevertheless able to elicit recognition by the F5 TCRs, as evidenced by prolonged but nonlethal CTL–APC associations.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cells and Peptides.

LDb cells (L929 fibroblasts (H-2Kk), stably transfected with H-2Db and neo), were cultured at 37°C with 5% CO2 in RPMI 1640 medium containing 10% fetal calf serum, 2 mM glutamine, 50 units/ml penicillin, and 50 μg/ml streptomycin (R10 medium), whereas the Db-restricted mouse CTL clone F5 was cultured in upright 25 cm2 flasks at 37°C with 5% CO2 in R10 supplemented with 50 μM 2-mercaptoethanol and 10 units/ml human recombinant IL-2, as described (10, 11). CTLs were used for cytotoxicity assays and video microscopy 4–6 d after stimulation with antigen-primed irradiated splenocytes. The nonamer peptides NP68 and NP34, and the two intermediate sequences NP372E (ASNENMEAM) and NP373T (ASNENMDTM), were custom synthesized and purified by RP-HPLC.

Chromium Release Assays of Cytotoxicity.

Method 1 of Townsend et al. (11) was followed, with 2 × 104 F5 cells cosedimented with 104 51Cr-loaded target cells per well. Peptides were included at the final concentrations shown in Fig. 1. Cell mixtures were incubated for 5 h, centrifuged, and the supernatants counted. After background correction and averaging of duplicate assays, the percentage of specific cytotoxicity was calculated as: 100 × (immune release − nonimmune release)/(total release − nonimmune release). The low effector cell to target cell ratio used (E/T 2:1), similar to that used in the video experiments, resulted in relatively low but reproducible maximum cytotoxicity. Both spontaneous and nonimmune release was <15% of total release.

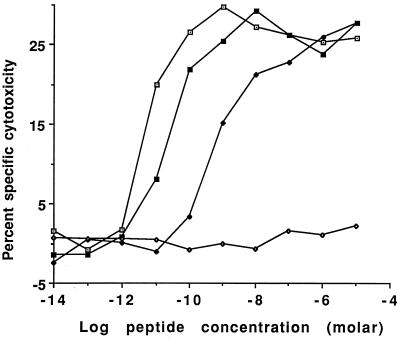

Figure 1.

Cytotoxicity of LDb target cells by F5 CTLs after 5 hr in the presence of varying concentrations of the normal or variant antigenic peptides. Percentage of specific cytotoxicity was determined by 51Cr release assay. Peptides NP68 (□), peptide NP373T (■) and peptide NP372E (♦) all acted as antigens, achieving maximal cytotoxicity at ≈10−10 M, 10−8 M, and 10−6 M, respectively. In contrast, peptide NP34 (⋄) induced no specific cytotoxicity, even when present at a concentration of 10−5 M.

Video Microscopy of Browse Times and Cytotoxicity.

Prepulsed target cells were prepared by overnight culture in R10 medium containing 100 nM NP68 or NP34, washed five times to remove all unbound peptide, and then allowed to adhere to 25-mm diameter glass coverslips for at least 4 hr at 37°C before use, at ≈20% confluence. One coverslip was then inverted onto 350 μl of R10 medium buffered with 10 mM Hepes, pH 7.4 (R10H medium) containing ≈105 CTLs (E/T ratio ≈1:1), forming the upper window of a Leiden microscope observation chamber 1 mm deep (19). Alternatively, if target cells were not prepulsed with antigenic peptide, 10 nM NP68 or 300 nM NP34 was included in the R10H medium during the experiment.

Each experiment was started when the assembled Leiden chamber, thermostatically maintained at 37°C, was inverted onto the stage of a Zeiss IM35 inverted microscope, permitting the CTL to sediment slowly onto the lower coverslip bearing the target cells. Continuous timelapse recording of the same area throughout each experiment from the time of inversion permitted determination of the initial positions of the target cells devoid of CTLs, timing of CTL arrivals, and observation of their subsequent behavior. Experiments were typically of 6- or 12-hr duration. To avoid phototoxicity, individual differential interference contrast (Nomarski) images were captured every 6.4 sec by using a Photometrics (Tucson, AZ) CC200 cooled CCD camera with an exposure time of 0.1 sec, during brief illumination of the cells with 546 nm light by means of a computer-controlled shutter, and were recorded onto S-VHS videotape at 1/160 real time.

Timelapse recordings were scored and analyzed for effects of NP68 and NP34 on CTL motility and cytotoxicity. Only recordings that met strict criteria were subjected to quantitative analysis: All three recordings for each experiment (of cells pulsed with NP68, of cells pulsed with NP34, and of control cells free of exogenous peptide) had to be made in immediate succession by using the same batch of F5 cells between 4 and 6 days after stimulation (because of variation in F5 killing efficiency from batch to batch), and all three had to be technically excellent, showing appropriate cell numbers, good contrast, even illumination, stable focus, etc. In approximately three-quarters of the experiments conducted, only two of the three recordings met these criteria. These were not analyzed quantitatively, although visual examination showed them to be comparable with those presented here. The order of the recordings was randomized between experiments, although no effects attributable to the time interval after stimulation were noticed. Cell health during recordings was indicated by the maintenance of CTL motility, target cell lamellipodial ruffling, and occasional target cell mitosis. Spontaneous cell deaths were never observed.

Each recorded field of view ideally contained 12–16 target cells at ≈20% confluence and a comparable number of motile CTL. The time and duration of each CTL contact with a target cell (termed a “browse”), of each mitosis, and of each target cell death, were determined by strict application of the following rules: (i) Only unobscured target cells wholly within the field of view were recorded. (ii) Only definite cell–cell adhesions with identifiable starts were scored as browses. (iii) Simultaneous browses of more than one target cell by a single CTL were recorded as separate events, as were the simultaneous browses of two CTLs on one target cell. (iv) Browses prematurely terminated by target cell entry into mitosis were not scored, but those that continued throughout mitosis on one of the daughter cells were counted as single browses. (v) Browses were deemed to end with the departure of the CTL, the onset of death, or the termination of the recording. These rules, necessary to avoid ambiguities in the analyses, led to slight underestimates of the number of browses that actually occurred, and of the durations of those browses still under way at the end of the recordings.

The statistical significance of the variations in browse times observed in the different experimental treatments was determined by the Mann–Whitney test (20), by using minitab software (Minitab, State College, PA). The nonparametric Mann–Whitney test of similarity among data groups, unlike the more familiar ANOVA test, does not require the data to be normally distributed. It was chosen because the browse times observed clearly did not show normal distributions (Fig. 4).

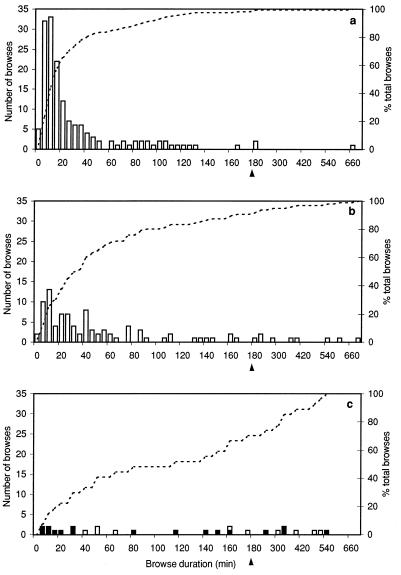

Figure 4.

Histograms of the browse times recorded for F5 cells on LDb target cells in the absence of exogenous peptide (a), on washed NP34-pulsed targets (b), and on washed NP68-pulsed targets (c), for which the summary statistics are given in Table 2. The arrowheads at 180 min denote a change in histogram-binning interval from 5 min to 30 min. The number of browses in each time interval is shown by the histogram bars (left axis), whereas the cumulative percentage of total browses up to that duration is shown by the dotted line (right axis), giving curves with distinctly different shapes for the three treatments. In c, those browses resulting in death of the target cell are shown by filled bars, being on average briefer than those that do not. Each browse time data set differs in a highly significant manner from the other two, as determined by the nonparametric Mann–Whitney test (20): P (No peptide v NP34) < 0.005; P (no peptide v NP68) < 0.005; P (NP34 v NP68) = 0.005.

Video Microscopy of Cell Motility.

In separate experiments, the effects of NP68 and NP34 on the intrinsic motility of F5 cells were studied in the absence of target cells. F5 cells (7 × 105 cells in 800 μl R10H) were allowed to pre-adhere to a coverslip for 2–4 hr at 37°C, mounted in a Leiden chamber, and maintained for 1 hr at 37°C in fresh R10H with or without 10 nM NP68 or 10 nM NP34 during timelapse video recording. Video images were digitized by using a Power Macintosh 7100/66AV computer (Apple Computers, Cupertino, CA), and imported into NIH image version 1.56. Cells that remained identifiable throughout the recording were numbered and analyzed, their linear displacements after a 20-min period being calculated from their spatial coordinates.

RESULTS

Chromium Release Assays of Cytotoxicity.

In assays of F5 cytotoxicity against LDb target cells (Fig. 1), NP68 was an effective antigen, giving one-half maximal killing at ≈5 pM, whereas NP373T and NP372E gave one-half maximal killing at ≈20 pM and ≈600 pM, respectively. All three antigens were saturable, reaching maximum killing between 1 nm (NP68) and 1 μM (NP372E). In contrast, NP34 gave no discernable killing even at 10 μM; it thus does not function as an antigen. In separate experiments, using the methods of Klenerman (8), NP34 also failed to antagonize F5 killing of NP68-pulsed target cells, although it competed successfully with NP68 for Db binding in mixed peptide chromium release cytotoxicity assays (data not shown).

F5 CTL Browsing and Cytotoxicity of NP68-Presenting Target Cells.

In the presence of NP68, F5 cells were observed to make long-lasting and highly dynamic contacts with target fibroblasts. Typically, as we found for another CTL clone (21), initial contact between F5 and target cells was rapidly followed by F5 flattening against the larger target cells, increasing the contact surface areas. The F5 cells then browsed the target cells by crawling actively and continuously on their surfaces, in what appeared to be an exploratory manner. Occasionally, a CTL abandoned its target cell and migrated away, perhaps to another target cell. More typically, after a browse time varying between 8 min and several hours, during which the target cell appeared perfectly healthy, the target cell would abruptly contract and undergo zeiotic death within a period of ≈10–20 min, exhibiting vigorous blebbing of the plasma membrane (Fig. 2). At the end of zeiosis, these blebs were usually resorbed, and the target cell corpse slowly became quiescent and compact, often detaching completely from the substratum, and showing no further signs of life. After killing one target cell, an F5 cell might then encounter and kill a second target cell (serial killing).

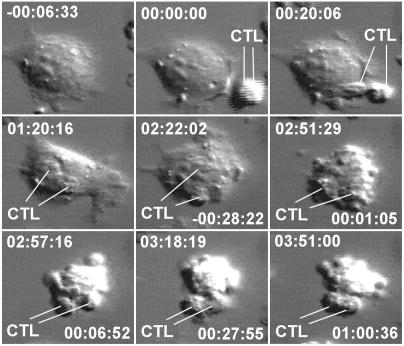

Figure 2.

Nine timepoints during the killing of a NP68-presenting LDb target cell by two F5 cells (CTL) during a timelapse video recording made in the presence of 10 nM P68. The times shown (hh:mm:ss) in the upper part of each image are relative to the moment of first contact between the CTLs and the target cell, whereas those in the lower part are relative to the first cytoplasmic contraction of the target cell at the onset of zeiotic death. During the long (almost 3 hr) browse that preceded death, the target cell appeared normal and healthy, with lamellipodial ruffling, and the CTLs moved actively over its surface. The target cell then contracted, rounded up, and exhibited zeiotic blebbing, actively for the first 15 min, and then with decreasing vigor for a further 20 min, by which time the target cell corpse had completely detached from the substratum and exhibited no further activity. The field of view is ≈40 μm wide.

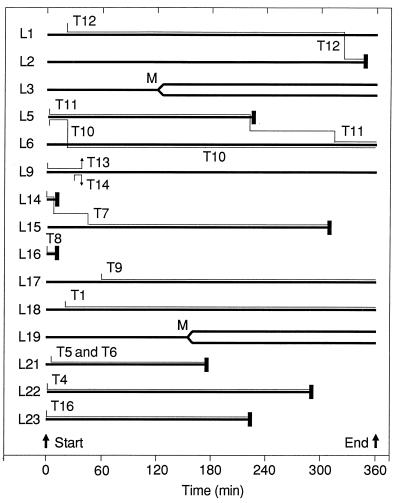

Fig. 3 summarizes the interactions observed between F5 cells and LDb target cells in one preliminary experiment conducted with 10 nM NP68 in the culture medium. During the course of the experiment, 13 of the 17 F5 cells made contact with 13 of the 23 target cells in the field of view. All the browsing phenomena described above are represented in the diagram, particularly the great variability in observed browse times (median browse time 170 min; mean browse time 163 min ± 130 min SD). As a result of these interactions, eight of the contacted target cells (62%) died, two being serially killed by a single F5 cell (T7) after browse times of 10 min and 4.5 h, respectively.

Figure 3.

Timelines showing all interactions made between the 17 F5 cells (T1–T17; thin lines) and 25 LDb target cells (L1–L25; thick lines) that were fully contained within the field of view during a timelapse video recording made in the presence of 10 nm NP68. Browses are indicated by adjacent F5 and LDb lines, and onset of zeiotic target cell deaths by heavy vertical bars. Subsequent fates of F5 cells are shown only if they resulted in a second browse. Four of the F5 cells failed to engage target cells, and 12 of the 25 target cells received no CTL contacts during the experiment. Timelines for those cells not forming contacts are omitted from the figure, except for those of L3 and L19, which both underwent mitosis (M) during the third hour. Three cells (L6, L17, and L18) were still being browsed when the experiment was terminated after a 6-hr recording.

Influence of Soluble Antigenic Peptide on F5 Motility.

The restriction of motility of F5 cells in the presence of soluble NP68 was quantified in the absence of target cells. In peptide-free medium or in the presence of 10 nM NP34, F5 migrated actively and continuously (mean linear displacements during 20-min observation periods: 60.3 μm and 62.9 μm, respectively; Table 1). In striking contrast, when 10 nM NP68 was present, the mean linear displacement of F5 cells was significantly reduced to 8.9 μm/20 min, and, at high density, the cells tended to form small clusters of 2–3 cells. Because of the marked effect that soluble antigenic peptide was found to have on CTL motility, great care was taken in all subsequent experiments to ensure that no soluble peptide remained to interfere with CTL motility and thus confound the quantitation of CTL browse times on target cells.

Table 1.

Motility data for F5 cells moving on glass coverslips in the presence or absence of 10 nM soluble antigenic or variant peptide

| Displacement, μm/20 min | Medium only, no peptide | Medium + NP34 variant peptide | Medium + NP68 antigenic peptide |

|---|---|---|---|

| Median | 66.9 | 60.3 | 4.6 |

| Mean ± SD | 60.3 ± 33.0 | 62.9 ± 39.5 | 8.9 ± 8.9 |

| Minimum | 4.2 | 5.9 | 1.9 |

| Maximum | 106.7 | 135.6 | 35.3 |

| Cells scored, n | 17 | 20 | 18 |

F5 Browse Times and Cytotoxicity on LDb Target Cells Pulsed with NP68 or NP34.

In Table 2 and Fig. 4, we present quantitative data derived from an experiment to determine the interactions of F5 cells with LDb target cells pulsed either with NP68, with NP34, or with neither peptide. The latter cells, presenting a variety of self peptides, served as matched controls. In all three situations, the F5 cells showed comparable rapid motility over regions of the coverslip devoid of target cells, bringing them swiftly into contact with the dispersed target cells, and confirming cell health and the adequacy of the washing protocol in removing soluble peptide that might interfere with cell motility. Although in principle it would have been desirable to use a second CTL line of differing antigenic specificity as an additional control, the fact that different CTL clones vary greatly in their inherent motility and killing efficiency unfortunately precluded such a comparison from being meaningful.

Table 2.

Browse time data for F5 cells making spontaneous contacts with washed LDb target cells previously pulsed with antigenic or variant peptide

| Measurement | LDb target cells with no peptide | LDb cells pulsed with 100 nM NP34 | LDb cells pulsed with 100 nM NP68

|

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total | Not resulting in target cell death | Resulting in target cell death | |||

| CTL browses* | |||||

| Number | 158 | 95 | 27 | 10 | 17 |

| Median duration (min) | 16 | 35 | 116 | 169 | 81 |

| Mean duration ± SD (min) | 35 ± 62 | 78 ± 124 | 170 ± 173 | 229 ± 170 | 135 ± 158 |

| Minimum duration (min) | 2 | 3 | 8 | 40 | 8 |

| Maximum duration (min) | 671 | 712 | 563 | 529 | 563 |

| Target cells | |||||

| Number of cells at start | 12 | 16 | 12 | ||

| Number of cells killed by CTL | 0 | 0 | 9 | ||

| Number of mitoses | 8 | 0 | 0 | ||

| Cells dropped from scoring | 1 | 1 | 0 | ||

| Number of cells after 12 h | 19 | 15 | 3 | ||

The three data sets from which these summary statistics are derived are significantly different from one another (see Fig. 4 legend). The video recording with NP34 was made on day 4, that with NP68 on day 5, and that with no peptide on day 6 after stimulation.

With target cells in the absence of exogenously added peptide, the CTLs made many APC contacts of highly variable duration (Fig. 4a), the majority of which were brief (Table 2: n = 158; median browse duration 16 min), only 7 (4.4%) lasting longer that 2 h, and none resulting in target cell death.

By contrast, washed LDb targets previously pulsed with 100 nM NP68 induced contacts that were on average much more long-lasting (Fig. 4c) and that were thus much fewer in total number (Table 2: n = 27; median browse duration 116 min), nearly one-half (13) of these browses lasting longer than 2 h. Seventeen of the browses (63%) resulted in death of the target cell. Because browses were deemed to end upon target cell death, these were on average shorter (mean duration 81 min) than the 10 that did not result in target cell death (mean duration 169 min). In total, nine of the 12 browsed target cells in the field of view (75%) were killed. Similar proportions of dead target cells were observed in other nonilluminated areas of the coverslip after the end of the timelapse videorecording.

Target cells pulsed with 100 nM of the variant peptide NP34 induced F5 browse numbers and times that differed significantly from, and were intermediate between, those on the control cells and those on targets pulsed with the antigenic peptide NP68 (Fig. 4b). Browses on NP34-pulsed cells showed enhanced persistence relative to the controls (n = 95; median browse duration 35 min), with 15 (16%) lasting >2 hours, but they were on average significantly briefer than on NP68-pulsed targets. Consistent with the 51Cr-release studies (Fig. 1), NP34 elicited no F5-mediated target cell death during these video experiments (Table 2).

Statistical analysis of the original browse time data from which Table 2 and Fig. 4 were prepared, using the Mann–Whitney test, showed that despite the large variations in browse times exhibited in each experimental situations, the results from the three treatments were significantly different from one another (P ≤ 0.005 in all cases). Thus the altered peptide ligand NP34 is indeed acting as a partial agonist, increasing CTL–target cell contact duration without inducing cytotoxicity.

DISCUSSION

One benefit of video microscopy is that it can be used to study interactions between individual living cells, providing a more detailed picture of cellular behavior than is obtained in bulk assays such as chromium release, which determine only the average behavior of cell populations. Using this technique, we have revealed effects of antigen sequence variation on the behavior of individual CTL that cannot easily be determined by alternative assay methods. Our observation that F5 cells alone, in the presence of soluble antigen NP68, exhibit much reduced motility suggests that F5 can detect peptide antigen autonomously, without requiring class I presentation by another cell type, as a result of self-engagement of the TCR by pMHCs on the same F5 cell. Additionally, one F5 cell can recognize Db-antigen complexes on another F5 cell, explaining the cell clustering that we, and others before us (22, 23), have observed.

We have confirmed the observations of Sanderson and subsequent researchers (14, 24, 25) that CTL cytotoxicity is characterized by the rapid zeiotic death of the target cells after highly variable browse times, which can be as short as 8 min or in excess of 9 hr (Table 2). Although it is known that CTL-triggered apoptotic death involves a complex multi-component enzyme cascade (26), this variability of browse times remains puzzling.

Whereas peptides NP372E and NP373T, each varying by a single residue from the natural antigen NP68, can both act as effective antigens, peptide NP34, differing from NP68 in both mutation positions, is completely unable to elicit cytotoxicity by F5. However, Db-NP34 complexes are indeed recognized by F5 cells, in the absence of cytotoxicity, as evidenced by the significantly enhanced browse times of F5 cells on NP34-pulsed target cells compared with unpulsed targets presenting a variety of Db-bound self-peptides, which thus act as ideal matched controls. These findings confirm that the TCR does not simply act as an on/off switch for CTL activation, but that it is sensitive to small structural changes in the MHC–peptide ligand complex, so that subtly variant peptides may induce qualitatively different cellular responses. Although target cells were pulsed with saturating concentrations of antigen, the subsequent rigorous washing and ≥ 4 hour recovery incubation will have resulted in dissociation of many of the initially bound peptides. Although all the target cells should still have displayed Db–antigen complexes in excess of the threshold of ≈200 copies (or less) reckoned to be required for cytotoxicity (27, 28), the number displayed is likely to be so low that the effects observed can only be attributed to specific TCR interactions, rather than some nonspecific effect of MHC occupancy.

Activation of a resting T cell can be divided into a hierarchical series of molecular events separated by distinct thresholds and checkpoints, controlling initial TCR engagement and adhesion, and the subsequent signal transduction events that result in cytotoxicity, cytokine secretion, and proliferation (29–33). In recent years, studies of the effects of altered peptide ligands (APLs) have shown that, among this hierarchy of early T cell signaling steps, partial agonists elicits some of the T cell physiological responses associated with full antigen stimulation, while blocking the completion of others, inducing a pattern of signal transduction events that is qualitatively different from that induced by the correct antigen at any concentration (1–3). Thus T-helper cells have been shown to respond to APL differing in a single residue by synthesizing cytokines but failing to proliferate (34, 35). Antagonist and partial agonist peptides presented by class II MHCs have been shown to induce abnormal tyrosine phosphorylation of the CD3 ζ chain, one of the earliest substrates in this signaling cascade, while failing to induce binding and activation of the associated ZAP-70 kinase, an enzyme believed to trigger downstream signaling events controlling gene expression (36, 37).

In CTLs, APLs may elicit cytotoxicity without down-regulating TCR molecules from the cell surface (6) or may antagonize normal responses to antigen (7–9). These data strongly suggest that the aberrant signaling induced by APLs is at the level of the TCR itself. Support for this view is given by Rosato et al. (38), who found that inhibition of tyrosine kinases blocked T cell cytotoxicity in a dose-dependent manner, by inhibiting phosphatidyl inositol turnover and granule exocytosis, but failed to abrogate conjugate formation between the inhibited CTLs and target cells.

How TCRs detect the small structural differences in pMHC between partial and true agonists remains unclear. Two explanations have been advanced, which are not mutually exclusive. The first is that the TCR adopts distinctly different conformations or aggregation states in response to the binding of APL (2, 39–41). The other explanation is that there is kinetic discrimination between ligands. Thus, McKeithan (4) has proposed a kinetic proofreading model of TCR signal transduction, in which, because it takes a finite time to complete certain energy-utilizing stages of T cell activation sequence, only the prolonged engagement of true antigen pMHCs by TCRs can elicit the whole panoply of activation events, whereas APLs may elicit an early subset of these, leading to a difference cellular response. Valitutti et al. (5, 6, 42) have given recent support to this explanation, showing by computer modeling that such differences may be explained by differing off-rates of TCR molecules after binding to APLs. In this scheme, TCR molecules, which are known to have relatively weak association constants for pMHCs, bind MHC molecules bearing true antigens for just sufficient time to permit full transmembrane activation of the tyrosine kinase enzyme cascade associated with the cytoplasmic domains of the TCR–CD3 complex, while having sufficiently fast off-rates to permit each pMHC to activate many (up to 200) TCR–CD3 complexes serially, thus giving a large and sustained CTL response to the presence of relatively few pMHCs. APLs, although binding MHCs with similar avidity as true antigens (39), have higher off-rates for the TCR, and hence associate for shorter periods, sufficient only to induce incomplete activation of the CTL signaling pathways, while antagonists with even faster off-rates result in TCR binding for periods too short to activate any cellular responses normally. A CTL encountering a target cell presenting either true antigen or APL would thus be expected in the first instance to engage and browse the cell, up-regulating intracellular adhesion as necessary, to allow the identity of the ligand to be ascertained and an appropriate response to be mounted.

Using timelapse video microscopy, we have been able to push the analysis of the complex stages involved in CTL activation one step closer to this initial cell surface recognition event, by showing how variant antigenic peptide can induce a behavioral response in the CTL, manifested as a prolonged association with the APC, without eliciting cytotoxicity. In a recent study, Dustin et al. (43) demonstrated that cells of a class I-restricted transgenic T cell line, migrating on an artificial planar lipid bilayer, stop moving when they encounter immobilized pMHCs, although they continue to ruffle and reoriented their microtubule organizing centers to central positions just above the substrate, in a manner analogous to the microtubule organizing center repositioning seen on T cell–APC complex formation in both CTLs and T helper cells (17, 44–46). However, it should be stressed from our own observations that when pMHCs are encountered by a CTL on the surface of a living target cell, the engaged CTL does not stop, but rather remains highly motile, although its excursions are spatially restricted to the surface of the cell on which it is actively browsing. Further studies are necessary to reveal whether this difference is due to differences in cell physiology, or to biophysical differences between the real membranes of our target cells and the model bilayer used by Dustin et al. (43), and to determine whether these early recognition events involve TCR-induced enzymic changes that directly result in enhanced cellular association, such as conversion of LFA-1 to its high-affinity form. However, the fact that browse times can be significantly increased by the minute amounts of NP34 remaining bound to the surfaces of washed target cells, previously pulsed with 100 nM NP34, leads us to favor activation of such an intracellular signaling pathway, whereas the fact that CTL-target cell interactions in the presence of saturating concentrations (10 μM) of soluble NP34 are completely unable to stimulate cytotoxicity indicates that this signaling pathway must be, at least in part, distinct from that leading to the delivery of a cytotoxic lethal hit.

Acknowledgments

We thank Alain Townsend and colleagues (Institute for Molecular Medicine, University of Oxford, U.K.) for cells and peptides and generous advice; Cetus Corp. for IL-2; and Hans Tanke, Hans de Bont, and Fred Nagelkerke (Sylvius Lab, University of Leiden, The Netherlands) for observation chambers and CCD camera timelapse software. We acknowledge with gratitude financial support for equipment from the U.K. Science and Engineering Research Council (now Biotechnology and Biological Sciences Research Council) and the Cancer Research Campaign, and for research expenses and a predoctoral fellowship (to A.A.) from the Howard Hughes Medical Institute.

ABBREVIATIONS

- APC

antigen presenting cell

- CTL

cytotoxic T lymphocyte

- APL

altered peptide ligand

- F5

an H-2Db-restricted murine cytotoxic T lymphocyte clone specific for NP68

- LDb

L929 fibroblasts (H-2Kk), stably transfected with H-2Db and neo

- MHC

major histocompatibility complex

- NP34

nonamer peptide ASNENMETM (residues 366–374 of the nucleoprotein of human influenza virus, 1934 strain A/PR/8/34)

- NP68

nonamer peptide ASNENMDAM (residues 366–374 of the human influenza virus nucleoprotein, 1968 strain A/HK/8/68)

- pMHC

peptide MHC complex

- R10

RPMI 1640 cell culture medium containing 10% FCS, 2 mM glutamine, 50 units/ml penicillin, and 50 μg/ml streptomycin

- R10H

R10 containing 10 mM Hepes buffer, pH 7.4

- TCR

T cell receptor

Footnotes

This paper was submitted directly (Track II) to the Proceedings Office.

References

- 1.Kersh G J, Allen P M. Nature (London) 1996;380:495–498. doi: 10.1038/380495a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sloan-Lancaster J, Allen P M. Annu Rev Immunol. 1996;14:1–27. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.14.1.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rabinowitz J D, Beeson C, Wulfing C, Tate K, Allen P M, Davis M M, McConnell H M. Immunity. 1996;5:125–135. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(00)80489-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.McKeithan T W. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1995;92:5042–5046. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.11.5042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Valitutti S, Lanzavecchia A. Immunol Today. 1997;18:299–304. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Valitutti S, Muller S, Dessing M, Lanzavecchia A. J Exp Med. 1996;183:1917–1921. doi: 10.1084/jem.183.4.1917. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jameson S C, Carbone F R, Bevan M J. J Exp Med. 1993;177:1541–1550. doi: 10.1084/jem.177.6.1541. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Klenerman P, Rowland-Jones S, McAdam S, Edwards J, Daenke S, Lalloo D, Koppe B, Rosenberg W, Boyd D, Edwards A, et al. Nature (London) 1994;369:403–407. doi: 10.1038/369403a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bertoletti A, Sette A, Chisari F V, Penna A, Levrero M, De Carli M, Fiaccadori F, Ferrari C. Nature (London) 1994;369:407–410. doi: 10.1038/369407a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Townsend A R, McMichael A J, Carter N P, Huddleston J A, Brownlee G G. Cell. 1984;39:13–25. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(84)90187-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Townsend A R, Rothbard J, Gotch F M, Bahadur G, Wraith D, McMichael A J. Cell. 1986;44:959–968. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(86)90019-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cerundolo V, Elliott T, Elvin J, Bastin J, Rammensee H G, Townsend A. Eur J Immunol. 1991;21:2069–2075. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830210915. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Elliott T, Smith M, Driscoll P, McMichael A. Curr Biol. 1993;3:854–866. doi: 10.1016/0960-9822(93)90219-e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sanderson C J. Proc R Soc London Ser B. 1976;192:241–255. doi: 10.1098/rspb.1976.0011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Geiger B, Rosen D, Berke G. J Cell Biol. 1982;95:137–143. doi: 10.1083/jcb.95.1.137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kupfer A, Singer S J. Annu Rev Immunol. 1989;7:309–337. doi: 10.1146/annurev.iy.07.040189.001521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kupfer A, Singer S J. J Exp Med. 1989;170:1697–1713. doi: 10.1084/jem.170.5.1697. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Costero I, Pomerat C M. Am J Anat. 1951;89:405–414. doi: 10.1002/aja.1000890304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ploem J S. In: Mononuclear Phagocytes in Immunity, Infection and Pathology. van Furth R, editor. Oxford: Blackwell Scientific; 1975. pp. 405–421. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Samuels M L. Statistics for the Life Sciences. San Francisco: Dellen; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Shotton D M. Histochem Cell Biol. 1995;104:97–137. doi: 10.1007/BF01451571. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Walden P R, Eisen H N. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1990;87:9015–9019. doi: 10.1073/pnas.87.22.9015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Su M W, Walden P R, Eisen H N, Golan D E. J Immunol. 1993;151:658–667. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Yannelli J R, Sullivan J A, Mandell G L, Engelhard V H. J Immunol. 1986;136:377–382. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hahn K, DeBiasio R, Tishon A, Lewicki H, Gairin J E, LaRocca G, Taylor D L, Oldstone M. Virology. 1994;201:330–340. doi: 10.1006/viro.1994.1298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Froelich C J, Dixit V M, Yang X. Immunol Today. 1998;19:30–36. doi: 10.1016/s0167-5699(97)01184-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Christinck E R, Luscher M A, Barber B H, Williams D B. Nature (London) 1991;352:67–70. doi: 10.1038/352067a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sykulev Y, Joo M, Vturina I, Tsomides T J, Eisen H N. Immunity. 1996;4:565–571. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(00)80483-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Dustin M L, Springer T A. Nature (London) 1989;341:619–624. doi: 10.1038/341619a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Dustin M L, Springer T A. Annu Rev Immunol. 1991;9:27–66. doi: 10.1146/annurev.iy.09.040191.000331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Moingeon P E, Lucich J L, Stebbins C C, Recny M A, Wallner B P, Koyasu S, Reinherz E L. Eur J Immunol. 1991;21:605–610. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830210311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bachmann M F, McKall-Faienza K, Schmits R, Bouchard D, Beach J, Speiser D E, Mak T W, Ohashi P S. Immunity. 1997;7:549–557. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(00)80376-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Shaw A S, Dustin M L. Immunity. 1997;6:361–369. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(00)80279-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Evavold B D, Allen P M. Science. 1991;252:1308–1310. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Evavold B D, Sloan Lancaster J, Allen P M. Immunol Today. 1993;14:602–609. doi: 10.1016/0167-5699(93)90200-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sloan-Lancaster J, Shaw A S, Rothbard J B, Allen P M. Cell. 1994;79:913–922. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(94)90080-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Madrenas J, Wange R L, Wang J L, Isakov N, Samelson L E, Germain R N. Science. 1995;267:515–518. doi: 10.1126/science.7824949. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Rosato A, Zambon A, Mandruzzato S, Bronte V, Macino B, Calderazzo F, Collavo D, Zanovello P. Cell Immunol. 1994;159:294–305. doi: 10.1006/cimm.1994.1315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Janeway C A., Jr Immunol Today. 1995;16:223–225. doi: 10.1016/0167-5699(95)80163-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Janeway C A, Jr, Bottomly K. Semin Immunol. 1996;8:108–115. doi: 10.1006/smim.1996.0013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Racioppi L, Germain R N. Chem Immunol. 1995;60:79–99. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Valitutti S, Müller S, Cella M, Padovan E, Lanzavecchia A. Nature (London) 1995;375:148–151. doi: 10.1038/375148a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Dustin M L, Bromley S K, Kan Z, Peterson D A, Unanue E R. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1997;94:3909–3913. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.8.3909. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kupfer A, Swain S L, Janeway C J, Singer S J. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1986;83:6080–6083. doi: 10.1073/pnas.83.16.6080. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kupfer A, Singer S J, Dennert G. J Exp Med. 1986;163:489–498. doi: 10.1084/jem.163.3.489. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Singer S J, Kupfer A. Ann Rev Cell Biol. 1986;2:337–365. doi: 10.1146/annurev.cb.02.110186.002005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]