Abstract

We report the investigation of a novel microfluidic mixing device to achieve submillisecond mixing. The micromixer combines two fluid streams of several microliters per second into a mixing compartment integrated with two T- type premixers and 4 butterfly-shaped in-channel mixing elements. We have employed three dimensional fluidic simulations to evaluate the mixing efficiency, and have constructed physical devices utilizing conventional microfabrication techniques. The simulation indicated thorough mixing at flow rate as low as 6 µL/s. The corresponding mean residence time is 0.44 ms for 90% of the particles simulated, or 0.49 ms for 95% of the particles simulated, respectively. The mixing efficiency of the physical device was also evaluated using fluorescein dye solutions and FluoSphere-red nanoparticles suspensions. The constructed micromixers achieved thorough mixing at the same flow rate of 6 µL/s, with the mixing indices of 96% ± 1%, and 98% ± 1% for the dye and the nanoparticle, respectively. The experimental results are consistent with the simulation data. The device demonstrated promising capabilities for time resolved studies for macromolecular dynamics of biological macromolecules.

Keywords: Microfluidics, micromixer, sub-millisecond mixing, CFD Simulation, Bio macromolecular Kinetics

Introduction

It is known that the function of biological macromolecules, such as proteins and nucleic acids, are defined by their specific structures, conformations, and dynamics [1–2,5]. Acquiring detailed structural information of macromolecular intermediates is essential to fully understand their mechanisms of action and dysfunction that can result in pathophysiology. These intermediate states often exist in the millisecond to second time scale, and can be characterized by biophysical techniques such as electron paramagnetic resonance, nuclear magnetic resonance, X-ray scattering, infrared and Raman spectroscopy, and cryo-electron microscopy [3–6,9]. A major challenge of these studies is to achieve a controllable homogeneous mixing of microliter or nanoliter amounts of macromolecular reactants in millisecond or submillisecond time frames before significant interaction or reaction occurs. Microfluidic mixers, with fast mixing capability, will be a promising and essential technology to achieve this objective efficiently [6–11].

Micromixers can be classified into two types: active [11–15] and passive [16–31]. The operation principles of the passive-type mixers are mainly based on fluid stretch, folding, breakup, and molecular diffusion. Simple fabrication, absence of moving components, and no requirement for an external power source make passive mixers more attractive than active mixers. With channels of micrometer-size dimension, the flow in the micromixer is predominately laminar [16–19], and mixing is usually achieved by molecular diffusion, which is generally slow, especially for macromolecules. Therefore, for micromixers based purely on diffusion to achieve fast mixing, the molecular diffusion distance (channel cross dimensions) has to be reduced drastically [17]. However, the small channel dimensions introduce significant pressure drops and increase the difficulty for the fabrication as well. Hydrodynamic focusing of fluids into nanoscale, submerged jets has been reported to achieve efficient mixing of nanoliters in microseconds [18]. However, it has disadvantages for macromolecules with low diffusivity, for which the mixing time can still easily reach milliseconds or even longer at the same experimental conditions. Thus, the channel length can be prohibitively long for fabrication on a silicon chip. It is also difficult to use this method for kinetics studies requiring long reaction (incubation) times (i.e. up to hundreds of milliseconds). These problems can be countered by application of chaotic advection strategies [20–30]. Extensive chaotic micromixer studies have mainly focused on achieving efficient mixing at low Reynolds numbers [21–24], but insufficient consideration has been given to mixing times, particle residence time distributions, or rates of sample consumption, all of which are important parameters for time-resolved studies of bio-macromolecular reactions.

Recently, numerous studies have explored the performance of continuous- or stopped- flow microfluidic mixing system for biological kinetic studies [6–10]. Several mixers employed lamination [6] and channel downsizing [7] to reduce molecular diffusion time. Generally, the mixing time based on this strategy was in the range of several to tens of milliseconds. Micromixers utilizing chaotic advection were capable of reducing the mixing time to the submillisecond time scale. To achieve the rapid mixing, the micromixers are usually operated at relatively large Reynolds number flow regions. Several studies engaged T-mixers to generate chaotic and turbulent flows for the rapid mixing [8–10], with the average mixing time in the range of dozens or hundreds of microseconds. However, In these studies either only numerical simulations were conducted [8], or detailed characterizations of the micromixers were not provided [9,10]. Moreover, for the majority of the mixing devices tested, the sample consumption, 20–500µL/s, was excessive for many biological applications, where quantities of valuable samples are limited.

In this paper, a novel in-plane passive micromixer was designed and evaluated to achieve submillisecond mixing. The designed mixers comprise mixing structures combining T-shaped premixers and in-channel butterfly mixing elements. The premixers split the two fluids into four streams before they flow into the butterfly elements, thus doubling the initial fluid interface area. The In-plane butterfly-shaped elements were designed to stir the fluid streams and achieve rapid mixing. Each element includes two sections containing sharp-folded channels to stir fluids, and to split/converge the fluids as well. Computational Fluidic Dynamics (CFD) simulations were employed to study the mixing efficiency and the particle residence time distribution inside the mixer. Based on the simulation results, physical micromixers were fabricated. Mixing experiments were conducted using fluorescent dye solutions and nanoparticle suspensions to confirm the simulation results and to examine the performance of the mixer at the submillisecond time scale. Silicon and glass substrates were used, along with other conventional microfabrication techniques, to prepare the devices. In comparison to other rapid micromixers mentioned above, its mixing efficiency is high for flows of relatively low Reynolds numbers while still achieving submillisecond mixing times at low rates of the sample consumption (several microliters per second).

Materials & Methods

Device Design

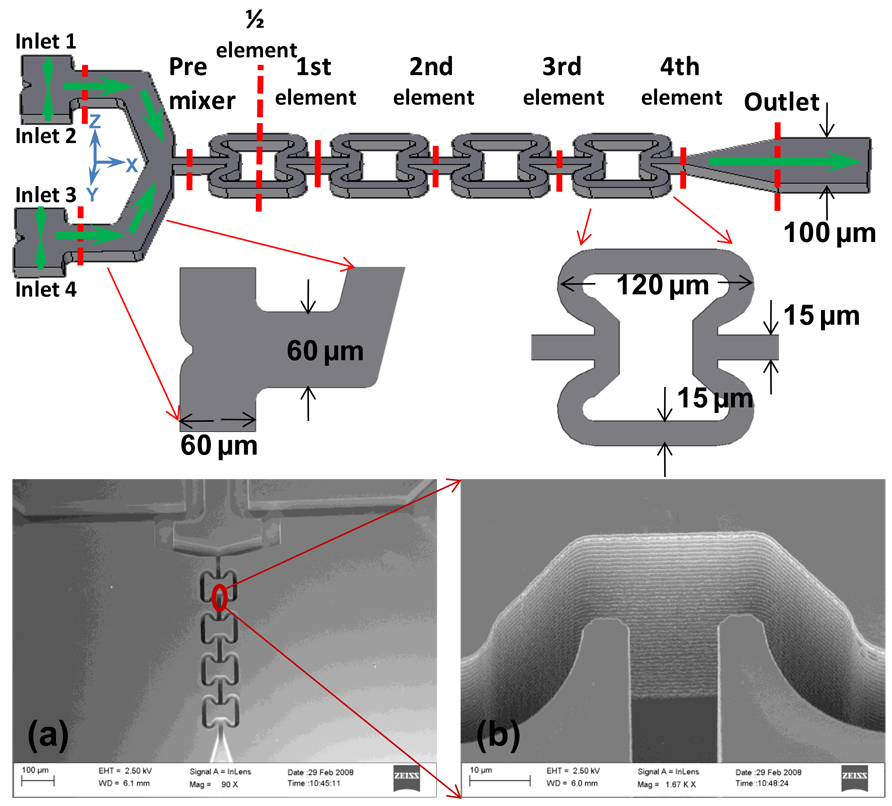

The micromixer has a mixing compartment that contains two T-shaped premixers and four butterfly-shaped in-channel mixing elements. The details of the mixing compartment configuration are shown in Figure 1. These mixers have four inlets immediately before the mixing compartment: inlets one and four are for one fluid and inlets two and three are for another fluid. Thus, two fluids were split and premixed in the premixers and then converged and further mixed in the channels with the butterfly elements. The flow directions and the corresponding coordinates are also shown in Figure 1 for reference. The four mixer inlets are 60 µm wide. The width of the premixer flow path is varied from 25 to 60 µm, and the width of the flow path inside butterfly elements is 15 µm. AS shown in Figure 1, the mixing compartment outlet is 100 µm wide, which is designed for the convenience of experimental mixing efficiency evaluation. The butterfly element is of dimension 120 µm by 120 µm. The channels of the tested mixer are 40 µm deep. Hemicircular pillars with 50 µm diameter and 10–20 µm gaps were fabricated in the fluid channels prior to the mixing compartment to serve as in-channel microfilters to prevent large agglomerates from blocking the mixing compartment. Details on the dimensions of the micromixer are shown in Figure 1, along with SEM images showing the details of half of one butterfly mixing element. The swept volume of the mixing compartment is ca. 2.5 nL.

Figure 1. Configuration of the Micromixer, with the Detailed Dimensions Labeled.

SEM images on the bottom show (a) the mixing channel as fabricated using DRIE etching technology, and (b) the details of half of the butterfly mixing unit

Computational Fluidic Dynamics (CFD) Simulation

Three-dimensional (3D) Navier-Stokes equations governing the fluid behaviors were employed in this study to simulate two aqueous fluids mixing in the designed micromixer. The simulation is conducted at steady-state conditions. The equation system includes mass, momentum, species conservation, and molecular diffusion equations as shown below [32]:

| (1) |

| (2) |

| (3) |

Where ρ is the fluid density, υ⃗ is the fluid velocity, p is the static pressure, τ̿ is the stress tensor, μ is the molecular viscosity, I is the unit tensor, Yi is the mass fraction of species i, J⃗i is the diffusion flux of species i, and Di,m is the diffusion coefficient for species i.

The Computational Fluid Dynamics (CFD) software package, FLUENT 6.0 (ANSYS, INC., Lebanon, NH), was used to simulate mixing by employing the finite volume analysis method. A three-dimensional mixer model was first constructed using AutoCAD (AUTODESK Inc. San Rafael, CA) software. The mixer structure was imported into GAMBIT (ANSYS, INC.) preprocessor to generate structured meshes using the Hex:Cooper meshing algorithm. The model was meshed with hexahedral elements of 0.5–2 µm size for the premixers, 0.5–1.0 µm size for the butterfly elements, and 0.5–4.0 µm size for the outlet channel. Cell sizes larger than 1.25 µm for meshing the butterfly mixing element resulted in significant numerical diffusion effects. Outlet channel length is extended to 5 times the outlet channel width to avoid outlet boundary effects. Four layers of boundary-layer meshes were attached to the walls to ensure that the fluidic region close to the channel walls is properly resolved. The accuracy of the simulation results was checked by decreasing the cell size and repeating the computation (see the supplementary figure for details). The final mesh volume applied is about 6.5 million cells. FLUENT served as the fluidic solver to carry out the simulation work.

The Species Transportation model was used to estimate the species mass fraction distributions in the mixer. The aqueous fluids that were simulated are assumed incompressible and their general physical properties are identical to water. The laminar flow model was applied, and the species transport model was solved along with mass and momentum equations. Specifically, one fluid is assumptive aqueous solution, which contained the simulated solutes. It was introduced into the inlets two and three of the mixers with velocities of 0.1–0.625 m/s and its direction normal to the inlets; the other fluid is assumptive pure water, and was introduced into inlets one and four with the same fluidic condition. The initial mass fraction of the solute as assigned as 1×10−4, with the diffusion coefficient of 1×10−12 m2/s, chosen to simulate large globular macromolecules (e.g., a prokaryotic ribosomal subunits. The boundary condition of the mixer walls was assumed to be zero mass flux with no-slip flow condition. The SIMPLE algorithm for pressure-velocity coupling and second order upwind discretization was applied for the simulation. The calculated species mass fraction distributions across the channels were displayed for various planes normal to the flow path indicating the degree of mixing.

To estimate the residence time distributions of the species inside the mixer, the Lagrangian Discrete Phase model was utilized. The fluid velocity field was first calculated, and 19,200 particle tracers, initially evenly distributed at the inlets, were used to simulate macromolecular particles. At time zero, particles were injected at the inlets two and three into the system with the same inlet velocity. The particle size was assigned to be 20 nm. The density of the particle tracer is assigned to 1.35 g/cm3, to mimic the protein particles. The Runge-Kutta particle tracking scheme was used to generate the particle traces [28,29]. The simulation tracked the positions of all the particle tracers flowing through the mixer with the time step of 2.5×10−5 second, and recorded their residence times when they pass through certain planes normal to the flow path and at the outlet.

Device Fabrication

The mixers were fabricated using conventional microfabrication technology. A chrome mask was generated containing the mixer channel patterns. The patterns were then transferred to a 4-inch-diameter silicon wafer coated with a ca. 1.0 µm thick positive 1813 photoresist layer. A Karl Suss UV-light mask aligner was used to transfer the pattern. The wafer with the patterned photoresist layer was then dry etched using an Alcatel AMS100 DRIE etcher utilizing the Bosch etching process. 40.0 ± 2.0 µm deep channels were generated by the etching. The wafer was then cleaned using Piranha etching to remove organic residue. In the next step the backside of the wafer was aligned and patterned to form mixer inlet and outlet holes. The photoresist used here was SU-8 2010 with the thickness of ca. 20 µm. A protective layer of 0.5 µm SiO2 was deposited on the front side of the wafer. The wafer was then dry etched again from the back side through the whole wafer to form the device inlets and outlets. The SU-8 layer served as an etching mask. The etched wafer was anodically bonded to a 4 inch 480 µm thick Pyrex 7740 glass wafer to seal the mixer channels. In the final step, the bonded wafers were first diced to obtain individual mixers, and then bonded with tubing fittings (polyetheretherketone (PEEK) nanoports, Upchurch Scientific Inc.) at 165°C for one hour. The mixer was connected through 1/16” PEEK capillary tubing with 250 µm inner diameter to fluid-delivering pumps.

Mixing Visualization

The mixing tests were conducted by visualization of fluorescent dyes and nanoparticles inside the mixers, and the results obtained were examined for consistency with the simulation results. The fluorescent dye, sodium fluorescein (FITC, MW 376.27), was purchased from Sigma-Aldrich, and 24 nm -diameter FluoSphere-red fluorescent nanoparticles in suspension were purchased from Molecular Probes (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA). All the chemicals were used without further treatment. The dye solutions were prepared by dissolving measured amounts of dye in deionized (Millipore) water. The nanoparticle suspensions were diluted from a 2% (w/v) stock suspension. The concentrations of the dyes used in this study were 0.02 mg/mL, and the final nanoparticle suspension concentration was 0.1%. All the solutions were prefiltered through a syringe filter with pore size of 0.2 µm to remove large particulates.

The device was connected through 2.0 µm PEEK microfilters to a Cole Parmer dual syringe pump. The transparent glass wafer allowed observation of species mixing in the device via fluorescence optical microscopy. Two 2500 µL glass syringes were loaded with either FITC solution or FluoSphere-red suspension. The flow rates of the two syringes were equal and experiments were performed at flow rates of 1.0 – 6.0 µL/second.

A Nikon TE2000 fluorescence microscopy system was used in the study, employing objective lenses of 4X and 10X magnification. The fluorescence intensity distributions in the channel were captured by the Image Pro Plus 6.0 software package (Media Cybernetics Inc.) via a CCD camera. The emission wavelengths of 522 (green fluorescence) and 603 nm (red fluorescence) were selected for the fluorescence image collection. The exposure time was 25 milliseconds for both wavelengths. The captured fluorescent images (12 bit grayscale images with the resolution of 1392×1040) were analyzed using Image Pro Plus. Two dimensional fluorescence intensity profiles across mixing channels at selected positions normal to the flow path (X-axis) of the mixer were extracted for the mixing efficiency evaluation.

Enzyme Activity Test

Biological macromolecules are usually sensitive to the environment. Harsh conditions can easily damage the molecules, resulting in loss of enzymatic activity. In a micromixer application, possible causes for deactivating a protein include shear force effect, especially in a flow field with relatively high velocity gradients. To evaluate the current mixer on this issue, the enzyme malate dehydrogenase (MW 70,000) was pumped through the mixer at flow rates of 2.0 –10.0 µL/s. The enzyme solution had a concentration of 500nM in 50mM Tris HCl, 10mM MgCl2, and 1mM DTT at pH 7.5. The solution that passed through the mixer was collected in a centrifuge tube, and the enzyme activity was determined by measuring NADH concentration using a Perkin-Elmer DU-640 spectrophotometer based on the following reaction:

The results were compared to the control sample that had not passed through the mixer.

Results and Discussion

CFD Simulation

FLUENT simulation results obtained at different inlet flow velocities were the basis for evaluating the mixer design for mixing efficiency. Figure 2 shows simulation results for a micromixer that contained four butterfly elements (illustrated in Figure 1). Mass fraction profiles are illustrated at certain mixing planes normal to the flow path, such as at the exits of each butterfly elements (positions are shown in Fig. 1). The red color represents totally unmixed solution; the blue color represents pure water. The color gradient between red and blue indicates the degree of mixing, and a uniform mass fraction contour across the mixer outlet indicated thorough mixing, which shows as green.

Figure 2. Simulated Species Mass Fraction Contours at Different Mixing Planes Normal to the X-axis Direction Across the Mixing Channel.

Various flow rate rates simulated, the red color indicated unmixed species, the blue color indicates water, the color gradient between red and blue indicates degree of mixing

Flow velocities of 0.1–0.625 m/s (1.0–6.0 µL/s), were applied at the four mixer inlets. The corresponding Reynolds numbers range from 8.0 to 48.1, specifically, 8.0, 16.0, 24.1, 32.0,40.0, and 48.1 for the flow rates 1.0, 2.0, 3.0, 4.0,5.0, and 6.0 µL/s, respectively. Inside butterfly mixing regions, the corresponding maximum Reynolds number are estimated at 40.8, 81.5, 122.2, 163.0, 203.7, and 244.4. Here, the Reynolds number [30], which characterizes the flow regions, was defined as Re = ρυL/μ, in terms of the liquid density ρ, mean flow velocity υ, liquid viscosity μ, and the hydraulic length of the channel L. For flow at low Reynolds number (e.g., at the flow rate of 1.0 µL/s), the fluid interface distortion is minimal when the fluids pass each mixing element, and not much fluid stretching and folding can be observed in this case, as shown in Figure 2. A clear fluid interface can still be seen at the mixer outlet, which indicates that the fluid mixing is still dominated by viscous forces. When the fluid velocity was increased to 2.0 µL/s, with the inlet Reynolds number at ca. 16.0, the fluid interface starts to show obvious distortion and stretching inside the butterfly elements, as indicated by the mass fraction contour at the various planes. The transverse motion of the fluid becomes significant, especially at the top and bottom portions of the channel close to the walls. As the flow velocity was continuously increased (> 3.0 µL/s), the interfaces stretched and folded further, and helical rotations started to form. As the fluid flows sequentially through the butterfly elements, this transverse flow stirred the solutions rapidly, increased the interfacial area of the two fluids, and reduced the diffusion distance in the transverse direction. Thus, mixing was largely enhanced. With the higher flow rates, the inertia force overwhelms viscous force and dominated the flows in the microchannels. At a flow velocity of 6.0 µL/s, the mass fraction contours of the simulated species becomes uniform through the cross section of the mixer outlet, indicating complete mixing. In this situation, the maximum Reynolds number inside the mixer was ca. 244.

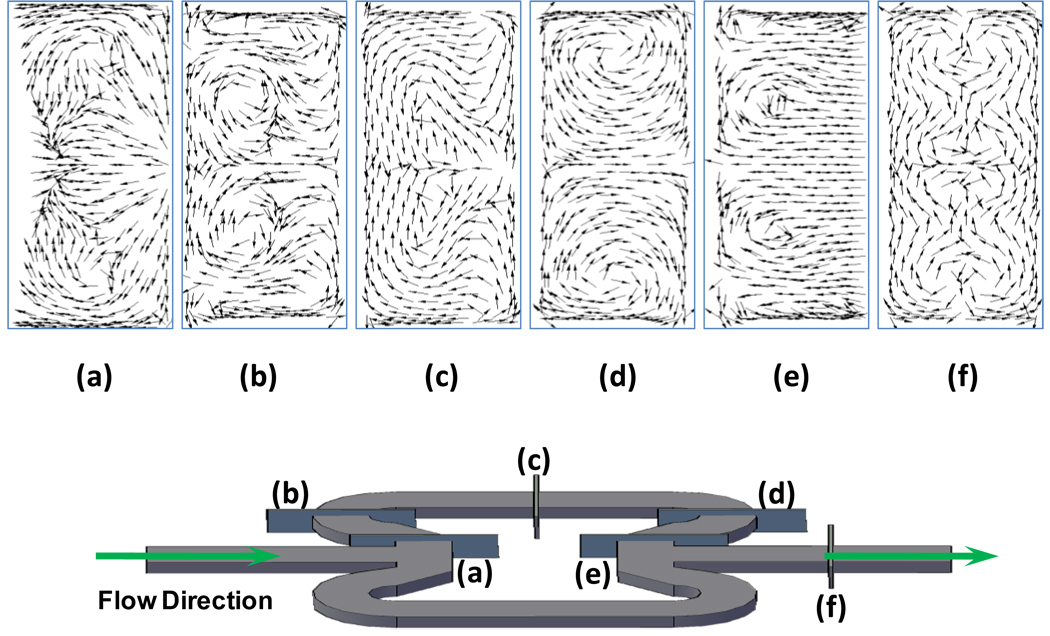

Figure 3 shows the in-plane velocity vectors at specific planes normal to the flow path of the first butterfly element. The entrance flow velocity is set at 6.0 µL/s. The arrows indicate the direction of velocity of secondary flows. When the fluids enter the first half of each butterfly element, the fluid suddenly encounters a wall that is normal to the flow path, and undergoes a sharp bending with an angle of ca 150°. A boundary layer separation occurs at the end of the entrance channel, and simultaneously, secondary flows start to form due to the centrifugal force acting on the fluids [24,26–27]. As shown in Figure 3(a), the flows on the top and bottom walls of the channel bend more inwards than the center portion of the flow, and rotate to the center across the channel. Thus two counter-rotation vortices are generated that wrap and fold the fluids. As the fluid passes the hemicircular channel following the sharp bend, the two vortices moved towards the center of the channel, and there are two weaker and flatter vertices formed closed to the top and bottom walls as the result of the further directional change of the flow path, as shown in Figure 3(b). Figure 3(c) shows that in the straight portion of the butterfly element, mainly two counter-rotation vortices exist. The second half of the element further enhances the vortices again inside the mixing channel, as shown in Figure 3(d,e). The convergence of the two split fluids into the exit channel of the first element results in the evolution of more vortices: four close to the top and bottom walls, and the other four close to the center of the channel (Fig. 3(f)). The two portions of the butterfly element containing abrupt flow path shifts are the contributors to the vortex formation, which is the main source for fluid stirring and effective mixing. When slower velocities were modeled, the vortices were much weaker (data not shown), and less stretching occurred, which resulted in less mixing. Previous simulations were also carried out on non-butterfly-shape mixing structures [34]: for example, mixing elements having a semicircular cross-sectional shape were much inferior to the butterfly elements in promoting effective mixing.

Figure 3. Velocity Vectors at Different Planes Normal to the Flow Path of the First Butterfly Mixing Element (from plane (a) to plane (f)).

Flow rate was set at 6.0 µL/s, the velocity vectors showed the evolution of the secondary flow patterns (vortices) inside the mixer channel

To quantify the mixing performance at various flow rates, the mixing indices were calculated at the mixer inlet, outlet, and at the exits to the premixers and each butterfly element. The mixing index was defined using the standard deviation of the mass fraction at the cross section of the specific plane compared to the mass fraction standard deviation at the inlets. The formula used is as follows [21]:

| (4) |

where σ is the standard deviation of the mass fraction across the cross section at certain planes normal to the flow path, and σmax is the maximum standard deviation with fluids unmixed at the inlets. An mixing index value ranges bewteen minimum 0% and maximum 100% with the two extremum values indicating completely segregated or thorough mixed fluids. Larger mixing index values indicate better mixing. The mixing indices were calculated and are plotted in Figure 4. The mixing index does not change much when the fluids exit the premixers for all the flow rates that were simulated, mainly because of the lack of flow stirring. When low flow rates were applied, the mixing index increased linearly as the fluids passed through each butterfly mixing element, and reached 26% and 79% for the flow rate of 1.0 and 2.0 µL/s, respectively. With the flow rate increased to above 3.0 µL/s, the mixing index increase fast and obeys a exponential law along the flow paths of the butterfly mixing elements. The mixing index increases the most at the first and second butterfly elements, and tends to saturate after the fluids pass through the third or fourth elements, which indicates that the high velocity extensively stretches, folds, and increases the interface area of the two fluids, minimizes the diffusion distance, and thereby induces fast mixing. The mixing index reaches values of 97% and 99% for the flow rates of 5.0 and 6.0 µL/s, and thorough mixing is considered to be achieved in these conditions.

Figure 4. Mixing Index of Simulation Results Along the Mixer Channel at Various Flow Rates.

The mixing index increases rapidly in a logarithmic relationship along the channel, at the flow rates above 3.0 µL/s. The mixing indices at the outlet reached 99% for the flow rates of 6.0 µL/s.

Another important fluidic dimensionless number is the Péclet number [16,20], which characterizes the fluid mass transport ratio of the rates of flow advection and molecular diffusion. It is defined as Pe = υL/D, where υ is the mean flow velocity, L is the hydraulic length of the channel, and D is the diffusivity of molecules. The estimated Péclet numbers in this study are in the range of 1×106 – 108, for the flow rate of 6.0 µL/s, based on the macromolecular diffusion coefficient of 1×10−11 – 10−12 m2/s. For uniaxial flows, the axial distance required for complete mixing is [20,28]:

| (5) |

Based on the above equation, for pure diffusion mixing duct flows at the flow rate of 6.0 µL/s, with the channel dimensions comparable to our micromixer, the Δym required to achieve complete mixing will be in the range of hundreds to thousands of meters. For our mixer, the estimated fluid flow path length is ca. 1.5 mm from the inlet to the outlet for the mixing, indicating that the mixer effectively reduced the mixing length.

The particle residence time distribution (RTD) is another important factor that characterizes the micromixer, and is especially relevant for reaction dynamics studies. Figure 5 plots the particle residence time distribution E(t) and the cumulative distribution F(t) for the particles eluted from the outlet of the mixer over 0.025-millisecond time slots. For the pulse tracer input method, the RTD function E(t) is given by [38]:

| (6) |

where c(t) is the tracer concentration at the outlet as a function of time. In this work, it is the particle number eluted from the outlet as a function of time. The cumulative distribution function F(t) is defined by [38]:

| (7) |

As indicated in Figure 5, at the flow rates where thorough mixing is obtained, submillisecond mean residence time was achieved. For the flow rate of 5.0 µL/s, The simulated mean residence time of the particles inside the mixer are 0.54 ms and 0.61 ms for 90% and 95% of particles, which is comparable to the calculated mean residence time of 0.55 ms derived from the volumetric flow rate. There are particles close to the channel walls, where the flow velocity is small, and even close to zero [29]. It will take excessive long time to calculate the residence times for those particles. So those particles (~5% in total) were excluded in our calculation. For the flow rate of 6.0 µL/s, the above values are 0.44 and 0.49 ms for 90% and 95% particles, respectively, while the calculated number is 0.46 ms. The simulated mean residence time involving 95% particles or more is generally longer than the calculated value. This could be explained by the vortices generated inside the mixer, which lead to contra-flows in the system. The contra-flows may retard or even trap some nanoparticles, and thus increases the mean residence time. Another possibility is the inadequately resolved slow velocity gradients at the near wall region due to insufficient numerical meshes at this region, which would require excessive numerical computation to improve the accuracy[33]. However, for potential dynamics studies, the residence time distribution for the majority of the nanoparticles is usually the main concern. In this study, for the flow rate of 5.0 µL/s, 80% of the particles that were tracked exit the outlet within the time slot of 0.25 to 0.85 milliseconds, while 90% of the particles exit in less than 1.48 milliseconds. For the flow rate of 6.0 µL/s, 80% of the particles exit within the time slot of 0.23 to 0.70 milliseconds, and 90% exit within 1.20 milliseconds.

Figure 5. Simulated Particle Residence Time Distribution E(t) and F(t) at the Mixer Outlet.

Submillisecond mean residence time was achieved at high flow rates, such as 5.0 & 6.0 µL/s.

Device Test using Dye and Nanoparticles

Fluorescent dyes or other color indicators are commonly utilized for visualization of mixing in microchannels [20,23–24]. In this study, experiments to evaluate the mixing efficiency and verify the simulation results were conducted using FITC fluorescent dye solutions and 24 nm FluoSphere-Red nanoparticle suspension combinations. The latter selection of fluorescent nanoparticles for the visualization is to mimic macromolecules with low diffusion coefficients.

FITC solution was fed to inlets two and three, while FluoSphere-Red suspension was fed into inlets one and four simultaneously. The flow rates were the same for both fluids. Figure 6 shows the red-green color composite images constructed from grayscale images captured using 522 and 603 nm fluorescence emission wavelengths. At low flow rates, i.e., 1.0 µL/s, the image exhibits sharp red-green bands with a clear fluid interface at the mixer outlet, indicating little mixing occurred in this condition. With the increase of the flow rate, fluid interfaces become vague, broadened, with reduced striations, indicating that mixing has occurred. With further increase of the flow rates, the fluorescence intensities characteristic of either of the two species are reduced significantly and a more uniformly distributed intensity as expected for a mixture of the two fluorescent species is observed across the channels, signifying good mixing inside the microchannels. Figure 6 also summarizes the fluorescence intensity line profiles of the two species at the outlet, at the various flow rates applied. The data in Figure 6 clearly show the evolution of the fluorescence intensity distribution across the outlet channel: at low flow rates significant variations of the fluorescence intensities are present, manifested by the large humps and grooves. The large variations vanish with increasing flow rate, and finally transform into flat curves at the highest flow rate of 6.0 µL/min, which indicates thorough mixing.

Figure 6. Fluorescence Microscopy Images of Fluorescein and Fluosphere-red in the Fabricated Mixer at Various Flow Rates.

Upper four panels show fluorescence micrographs at the indicated flow rates. Lower panels show fluorescence distribution profiles at mixer outlet for fluorescein (a) and fluosphere-red (b). The decrease in variation with the increasing flow rate signifies more even mixing across the channel. The flat curves for the dye and nanoparticles at the flow rate of 6.0 µL/min indicate thorough mixing

To quantify the mixing performance, the 12 bit grayscale images of two wavelengths were analyzed. Pixel data (0.65 µm × 0.65 µm) of two dimensional fluorescence intensity profiles were extracted from specific planes, which were normal to the flow path and across the microchannels. The gray levels of each individual pixel are linearly proportional to the fluorescence intensity of the species, and the collected data set can be used to estimate the mass fraction distributions of those species when they pass through the mixer. It has been reported that the capability of the optical microscope to focus on different channel depths allows detection of the presence of horizontal stratified layers. This is a way of ensuring the good mixing observed in the mixing channel is not just an artifact resulting from the horizontal stratified layers of unmixed liquids [30]. Thus sequential images along the Z-axis were taken for analysis, as shown in Figure 1. The standard deviations of the fluorescence intensities were calculated for certain planes normal to the flow path (X-axis direction) by combining data from the sequential Z-axis data at that plane. In this way, the vertical intensity variation was taken into consideration as well. The mixing index was determined using the same formula employed in the simulation section. To determine the point of complete mixing, reference images were taken at the corresponding positions by feeding premixed fluids (with 1:1 volumetric mixing ratio) into the mixer. The reference image capturing conditions (flow rates, exposure time, and objective lens) were set the same. The standard deviation of the fluorescence intensity profiles was corrected by subtracting it from the standard deviation of the reference intensity profile, thereby normalizing for errors caused by the imaging process. Due to the optical effect of the channel walls [17,27], it is difficult to analyze the data for mixing index calculations in the narrow channels at the exit of each butterfly mixing element, and so only data at the mixer outlet were collected for the mixing index estimation. For the same reason, i.e., optical effects at channel walls, the portion of the intensity profiles within a distance of 8 µm to the channel walls was excluded from the mixing index calculation as well.

The calculated mixing index at the mixer outlet for the two species is plotted in Figure 7, along with the simulated results for comparison. The results show that the experimental results are generally consistent with simulation data, for both species studied. At lower flow rates (<2.0 µL/s), there is large deviation for the experimental mixing indices from the simulation results. This is because the optical microscopy tends to result in better mixing index values at lower flow rates compared to the results from confocal microscopy, due to the pixel intensity averaging along the depth of the channel [39]. However, it has been reported that, at high flow rates (≥ 250 µL/min), when good mixings were approaching in the microchannels, the two imaging methods provides similar differences between the premixed and the mixed standard deviation values indicating that both methods can be used to measure mixing efficiency [39]. In our work, with the flow rate at 5.0 µL/s, the mixing index for the dye is calculated as 93% ± 2%, and for the nanoparticles is 95% ± 3%, respectively. For the flow rate of 6.0 µL/s, the mixing indices are 96% ± 1%, and 98% ± 1% for the dye and the nanoparticles. The average deviation of the experimental results from the simulated results at the flow rate of 6.0 µL/s is about 2%.

Figure 7. Calculated Mixing Index of Experiments at Mixer Outlet Compared to The Simulation.

The results show that the experimental results are comparable to the simulation data, for both species studied. For flow rate of 6.0 µL/s, at which mixing is considered complete, the mixing indices are 96% ± 1%, and 98% ± 1% for the dye and the nanoparticle, respectively. The average deviation of the experimental results from the simulation calculation is about 2%.

Enzyme Activity Test

Figure 8 presents enzymatic activity measurements for malate dehydrogenase, which was passed through the mixer at various flow rates up to 10 µL/s. Full activity, assessed by comparison to enzyme that had not gone through the mixer, was retained at all flow rates tested. Note that the highest applied flow rate (10.0 µL/s) is higher than the any of the flow rates used in the previous experiments. These results are a good indicator that the device will not deactivate the biological macromolecules at the experimental conditions that were tested, and will be useful for biophysical characterization of the dynamics of functioning and/or assembling macromolecular complexes.

Figure 8. Enzyme Activity Test Using Malate Dehydrogenase.

The results indicate that the enzyme retained full activity at all the flow rates used.

Conclusion

In this study, 3D CFD simulations were conducted to evaluate mixing performance of a novel micromixer design that combined two T-shaped premixers with four butterfly-shaped in-channel mixing elements. The simulation results showed that the mixing structures in the mixer efficiently stirred the fluids, formed secondary vortex flows in the microchannels and improved drastically the mixing efficiency. At the flow rate of 5.0 µL/s, the calculated mixing index is 97%. At the flow rate of 6.0 µL/s, the mixer thoroughly mixed the two fluids with a mixing index of 99%. The corresponding mean residence time is 0.44 ms for 90% of the particles and 0.49 ms for 95% of the particles simulated. Physical micromixers with the same design were fabricated and tested to verify the mixing performance. The results indicated that the mixer performance is comparable to the simulation results. By increasing the number of the butterfly mixing elements, complete mixing at even lower flow rates can be predicted, with slightly longer mean residence time. This can further reduce the sample consumption, when this is a primary concern for certain dynamics studies of biological molecules.

The range of potential applications of the micromixer to time-resolved dynamics study of macromolecular complexes is vast, but largely unexplored [35–37]. Our goal is to make such studies much easier to undertake than is currently the case, and the development of micro-mixers such as those described here represents a significant step in achieving this objective.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgement

This work is supported by the Wadsworth Center’s Resource for Visualization of Biological Complexity (NIH Biotechnology Resource Grant RR01219). We acknowledge the Micro and Nano Fabrication Clean Room (MNCR) at Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute and the Michigan Nanofabrication Facility (MNF) at the University of Michigan for their help on device fabrication. We also thank Richard Cole and the Wadsworth Center’s Advanced Light Microscopy and Image Analysis Core for support on fluorescence visualization.

Biographies

Zonghuan Lu’s Biography

Zonghuan Lu is currently a research associate in Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute. He received his Bachelor of Science degree in Chemical Engineering from Dalian University of Technology, China. He obtained his Master degree in chemistry and Ph.D. degree in Chemical Engineering from Louisiana Tech University. After finished his study, he became a postdoctoral fellow in the Institute for Micromanufacturing in Louisiana Tech University, developing self-assembled micro-/nano- systems for bio applications. His current interests include lab-on-a-chip microfluidic systems for bio molecular kinetics studies.

J. Jay McMahon's Biography

J. Jay McMahon is currently working as a microfabrication engineer in the General Electric Global Research Center in Niskayuna New York. He received the B.S. and M.S. in Physics from Rochester Institute of Technology, and the University of Akron respectively. He received his Ph.D. in Electrical Engineering from Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute in Troy New York, after which he worked as a lead 3D integration engineer at SEMATECH in Albany NY. Research interests include varied MEMS and semiconductor fabrication techniques with a focus on integration at the wafer-level for new systems.

Hisham Mohamed’s Biography

Hisham Mohamed is currently a Research Scientist at the Wadsworth Center, New York State Department of Health (NYSDOH), Albany, NY. He received the B.S. degree in electrical engineering from Ain Shams University, Cairo, Egypt, in 1993, and the M.S. and the Ph.D. degrees in biomedical engineering from the University of Minnesota, Minneapolis, MN, in 1997 and 2000 respectively. His research interests are in the development of microdevices and in the implementation of Micro-Electro-Mechanical Systems (MEMS) for biomedical applications. His ongoing projects are in the area of rare-cell fractionation, on-chip filtration, rapid prototyping for microfluidics, and the use of carbon nanotubes for bio and energy applications.

David Barnard’S Biography

Is a Physicist – Engineer with Wadsworth Labs of New York State Dept. Health Albany, NY since 1978. His interests are in electron optics, optics, mechanical goniometers, and micro spray cryo-electron microscopy. He also has interests in electro mechanical control systems, electronics, fluid mechanics, vacuum, optical, small airplane pilot, windmill aerodynamics and energy conversion.

Tanvir Shaikh’s Biography

Tanvir Shaikh received his undergraduate degree in biochemistry & biophysics from Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute, and received his PhD from Brandeis University. From 2002 to the present, he has been at the Wadsworth Center. His interests are in structural biology, particularly time-resolved sample preparation and image-processing methodologies in electron microscopy

Carmen A. Mannella, Biography

Dr. Carmen A. Mannella is Director of the Resource for Visualization of Biological Complexity and Associate Director for Research Technology at the Wadsworth Center. He received his bachelor’s degree in physics from Canisius College and his doctorate in biophysics from the University of Pennsylvania. His primary research interest is the application of three-dimensional cryo-transmission electron microscopy to cellular organization and bioenergetics, with a focus on the internal organization of the mitochondrion and its associations with other organelles.

Terence Wagenknecht’s Biography

Terence Wagenknecht is a Senior Research Scientist at the Wadsworth Center of the New York State Department of Health. His research interests include applications of cryo-electron transmission electron microscopy and three-dimensional reconstruction to the protein assemblies that carry out excitation-contraction coupling in skeletal and cardiac muscle.

Toh-Ming Lu’s Biography

Dr. Toh-Ming Lu earned his BSc degree in Physics from The National Cheng Kung University (Taiwan) in 1968, MSc degree from Worcester Polytechnic Institute (USA) in 1970, and PhD degree from The University of Wisconsin, Madison (USA), in 1976. He has been a faculty at Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute since 1982. He was the Chair of the Physics Department from 1992 to 1997. Currently he is the Associate Director of the Center for Integrated Electronics. He is author or co-author over 400 papers and six books.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Creighton TE. Protein Folding. Biochem. J. 1990;270:1–16. doi: 10.1042/bj2700001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Boehr DD, Dyson HJ, Wright PE. An NMR Perspective on Enzyme Dynamics. Chem. Rev. 2006;106:3055–3079. doi: 10.1021/cr050312q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pollack L, Tate MW, Darnton NC, Knight JB, Gruner SM, Eaton WA, Austin RH. Compactness of the Denatured State of a Fast-Folding Protein Measured by Submillisecond Small-Angle X-ray Scattering. PNAS. 1999;96:10115–10117. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.18.10115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Federik PM, Sommerdijk N. “Spatial and Temporal Resolution in Cryo-electron Microscopy—A Scope for Nano-Chemistry“. Current Opinion in Colloid & Interface Science. 2005;10:245–249. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kakuta M, Jayawickrama DA, Wolters AM, Manz A, Sweedler JV. Micromixer-Based Time-Resolved NMR: Applications to Ubiquitin Protein Conformation. Anal. Chem. 2003;75:956–960. doi: 10.1021/ac026076q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kakuta M, Hinsmann P, Manz A, Lendl Bd. Time-resolved Fourier Transform Infrared Spectrometry Using a Microfabricated Continuous Flow Mixer: Application to Protein Conformation Study Using the Example of Ubiquitin. Lab on a Chip. 2003;3:82–85. doi: 10.1039/b302295a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wilson DJ, Konermann L. A Capillary Mixer with Adjustable Reaction Chamber Volume for Millisecond Time-Resolved Studies by Electrospray Mass Spectrometry. Anal. Chem. 2003;75:6408–6414. doi: 10.1021/ac0346757. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wong SH, Bryant P, Ward M, Wharton C. Investigation of Mixing in A Cross-Shaped Micromixer with Static Mixing Elements for Reaction Kinetics Studies. Sensors and Actuators B. 2003;95:414–424. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lin Y, Gerfen GJ, Rousseau DL, Yeh S. Ultrafast Microfluidic Mixer and Freeze-Quenching Device. Anal. Chem. 2003;75:5381–5386. doi: 10.1021/ac0346205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bökenkamp D, Desai A, Yang X, Tai Y, Marzluff EM, Mayo SL. Microfabricated Silicon Mixers for Submillisecond Quench-Flow Analysis. Anal. Chem. 1998;70:232–236. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Yang Z, Matsumoto S, Goto H, Matsumoto M, Maeda R. Ultrasonic Micromixer for Microfluidic Systems. Sensors and Actuators A. 2001;93:266–272. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bau HH, Zhong J, Yi M. A Minute Magneto Hydro Dynamic (MHD) Mixer. Sensors and Actuators B. 2001;79:207–215. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lin J, Lee K, Lee G. Active Mixing inside Microchannels Utilizing Dynamic Variation of Gradient Zeta Potentials. Electrophoresis. 2005;26:4605–4615. doi: 10.1002/elps.200500402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tsouris C, Culbertson CT, DePaoli DW, Jacobson SC, de Almeida VF, Ramsey JM. Electrohydrodynamic Mixing in Microchannels. AIChE Journal. 2003;49:2181–2186. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fu L, Yang R, Lin C, Chien Y. A Novel Microfluidic Mixer Utilizing Electrokinetic Driving Forces under Low Switching Frequency. Electrophoresis. 2005;5:1814–1824. doi: 10.1002/elps.200410222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hessel V, Hardt S, Löwe H, Schönfeld F. Laminar Mixing in Different Interdigital Micromixers: I. Experimental Characterization. AICHE Journal. 2003;49:566–677. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sullivan SP, Akpa BS, Matthews SM, Fisher AC, Gladden LF, Johns ML. Simulation of Miscible Diffusive Mixing in Microchannels. Sensors and Actuators B. 2007;123:1142–1152. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Knight JB, Vishwanath A, Brody JP, Austin RH. Hydrodynamic Focusing on a Silicon Chip: Mixing Nanoliters in Microseconds. Physical Review Letters. 1998;80:3863–3866. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bessoth FG, deMello AJ, Manz A. Microstructure for Efficient Continuous Flow Mixing. Anal. Commun. 1999;36:213–215. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Stroock AD, Dertinger SKW, Ajdari A, Mezić I, Stone HA, Whitesides GM. Chaotic Mixer for Microchannels. Science. 2002;295:647–651. doi: 10.1126/science.1066238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wang L, Yang J, Lyu P. An Overlapping Crisscross Micromixer. Chemical Engineering Science. 2007;62:711–720. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hassell DG, Zimmerman WB. Investigation of the Convective Motion through A Staggered Herringbone Micromixer at Low Reynolds Number Flow. Chemical Engineering Science. 2006;61:2977–2985. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Fu X, Liu S, Ruan X, Yang H. Research on Staggered Oriented Ridges Static Micromixers. Sensors and Actuators B. 2006;114:618–624. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sato H, Ito S, Tajima K, Orimoto N, Shoji S. PDMS Microchannels with Slanted Frooves Embedded in Three Walls to Realize Efficient Spiral Flow. Sensors and Actuators A. 2005;119:365–371. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hong C, Choi J, Ahn CH. A Novel in-Plane Passive Microfluidic Mixer with Modified Tesla Structures. Lab-on-a-Chip. 2004;4:109–113. doi: 10.1039/b305892a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Liu Y, Kim BJ, Sung HJ. Two-Fluid Mixing in a Microchannel. International Journal of Heat and Fluid Flow. 2004;25:986–995. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Goullet A, Glasgow I, Aubry N. Effects of Microchannel Geometry on Pulsed Flow Mixing. Mechanics Research Communications. 2006;33:739–746. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Park S, Kim JK, Park J, Chung S, Chung C, Chang JK. Rapid Three-Dimensional Passive Rotation Micromixer using the Breakup Process. J. Micromech. Microeng. 2004;14:6–14. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Jiang F, Drese KS, Hardt S, Küpper M, Schönfeld F. Helical Flows and Chaotic Mixing in Curved Micro Channels. AICHE Journal. 2004;50:2297–2305. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wong SH, Ward MCL, Wharton CW. Micro T-mixer as a Rapid Mixing Micromixer. Sensors and Actuators B. 2004;100:359–379. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Chen H, Meiners J-C. Topologic Mixing on a Microfluidic Chip. Applied Physics Letters. 2004;84:2193–2195. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Fluent 6.0 User’s Manual. 2006 [Google Scholar]

- 33.Heim M, wengeler R, Nirschl H, Kasper G. Particle Deposition from Aerosol Flow Inside a T-Shaped Micro-Mixer. Journal of Micromechanics and Microengineering. 2006;16:70–76. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lu Z, McMahon J, Mohamed H, Barnard D, Shaikh TR, Wagenknecht T, Lu TM. Microfluidic Mixing System for Time Resolved Cryo-Electron Microscopy. Microscopy and Microanalysis. 2008;14:1598–1599. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Noller HF. RNA Structure: Reading the Ribosome. Science. 2005;309:1508–1514. doi: 10.1126/science.1111771. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Unwin N. Acetylcholine Receptor Channel Imaged in the Open State. Nature. 1995;373:37–43. doi: 10.1038/373037a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Fuller SD, Berriman JA, Butcher SJ, Gowen BE. Low pH Induces Swiveling of the Glycoprotein Heterodimers in the Semliki Forest Virus Spike Complex. Cell. 1995;81:715–725. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90533-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Adeosun JT, Lawal A. Mass Transfer Enhancement in Microchannel Reactors by Reorientation of Fluid Interfaces and Stretching. Sensors and Actuators B. 2005;110:101–111. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kane AS, Hoffmann A, Baumgärtel P, Seckler R, Reichardt G, Horsley DA, Schuler B, Bakajin O. Microfluidic Mixer for the Investigation of Rapid Protein Folding Kinetics Using Synchrotron Radiation Circular Dichroism Spectroscopy. Analytical Chemistry. 2008;80:9534–9541. doi: 10.1021/ac801764r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.