Abstract

DNA ligases are essential guardians of genome integrity by virtue of their ability to recognize and seal 3′-OH/5′-phosphate nicks in duplex DNA. The substrate binding and three chemical steps of the ligation pathway are coupled to global and local changes in ligase structure, involving both massive protein domain movements and subtle remodeling of atomic contacts in the active site. Here we applied solution NMR spectroscopy to study the conformational dynamics of the Chlorella virus DNA ligase (ChVLig), a minimized eukaryal ATP-dependent ligase consisting of nucleotidyltransferase, OB, and latch domains. Our analysis of backbone 15N spin-relaxation and 15N,1H residual dipolar couplings of the covalent ChVLig-AMP intermediate revealed conformational sampling on fast (ps-ns) and slow (μs-ms) timescales, indicative of inter- and intra-domain flexibility. We identified local and global changes in ChVLig-AMP structure and dynamics induced by phosphate. In particular, the chemical shift perturbations elicited by phosphate were clustered in the peptide motifs that comprise the active site. We hypothesize that phosphate anion mimics some of the conformational transitions that occur when ligase–adenylate interacts with the nick 5′-phosphate.

Introduction

DNA ligases1; 2; 3 seal 3′-OH/5′-phosphate nicks in duplex DNA; they are ubiquitous in prokaryal, eukaryal and archaeal proteomes and in those of many DNA viruses. DNA ligases are responsible for Okazaki fragment joining during DNA replication and they participate in nucleotide excision repair, base excision repair, homologous recombination and non-homologous end joining pathways. As such, they are central to the maintenance of genomic integrity. Ligases are also promising targets for antibacterial and anticancer drug discovery4; 5.

The DNA nick-sealing pathway consists of three distinct chemical steps1; 2; 3. First, AMP is transferred from ATP or NAD+ to a lysine residue on the enzyme to generate a covalent ligase-(lysyl-Nζ)-AMP intermediate and release either inorganic pyrophosphate (from ATP) or NMN (from NAD+). In the second step, ligase transfers the AMP to the 5′-phosphate of the nick to form a DNA-adenylate intermediate with an “activated” phosphoanhydride terminus, A(5′)pp(5′)N. In the third step, the nick 3′-OH attacks the DNA-adenylate to generate a 3′-5′ phosphodiester bond and release AMP. All three steps require a divalent cation and are microscopically reversible under appropriate reaction conditions. RNA ligases catalyze the same three chemical steps during RNA strand joining reactions. The first two steps of the ligase pathway, namely covalent nucleotidylation of a conserved lysine and transfer of the NMP to a polynucleotide 5′ terminus, are shared with eukaryal RNA capping enzymes6, which together with DNA/RNA ligases, comprise a covalent nucleotidyltransferase superfamily.

All known DNA ligases share a core structure composed of a nucleotidyltransferase (NTase) domain fused to an OB-fold domain1; 2; 3. The NTase domain contains an adenylate-binding pocket composed of six peptide motifs (I, Ia, III, IIIa, IV and V) that define the covalent nucleotidyl transferase superfamily. Motif I (KxDGxR) harbors the lysine nucleophile to which AMP is covalently linked. Many amino acids in the six motifs contact AMP directly and are essential for one or more steps of the nick-sealing pathway. The OB domain, that is a critical component of the DNA binding surface of all DNA ligases, consists of a 5-stranded antiparallel β-barrel with a flanking α-helix. It engages the DNA across the minor groove on the face of the duplex behind the nick. The OB domain of the ATP-dependent DNA ligase subfamily includes an additional nucleotidyltransferase motif (motif VI, located near the C-terminus) that is posited to promote the step 1 adenylylation reaction by orienting the pyrophosphate leaving group of ATP apical to the attacking motif I lysine.

DNA ligases differ with respect to the number, size, and variety of accessory domains that are appended to the core NTase-OB architecture. Eukaryal cellular DNA ligases, archaeal DNA ligases, and vaccinia virus DNA ligase7 (all ATP-dependent) have a large (≥200-amino acid) all α-helical DNA-binding domain (DBD) fused proximal to the NTase domain; the DBD forms part of the C-shaped protein clamp that envelops the nicked DNA duplex during steps 2 and 3 of the ligation pathway. Bacterial NAD+-dependent DNA ligases have a suite of distinctive and independently folded structural modules attached upstream or downstream of the NTase-OB unit; the flanking domains confer NAD+ specificity and comprise part of the ligase clamp around nicked duplex DNA1; 2; 3. Even the most minimized DNA ligase, the 298-amino acid enzyme encoded by Paramecium bursaria Chlorella virus I (henceforth referred to as Chlorella virus ligase, or ChVLig)8, has a small (23-amino acid) latch module inserted within the OB domain that is critical for ligase clamping around the nicked DNA9. It appears that encirclement of damaged DNA by a protein clamp is a shared feature of DNA ligases, notwithstanding that ligase subfamilies differ with respect to the domain topology and domain composition of the clamp2.

Crystal structures of DNA and RNA ligases and RNA capping enzymes from diverse sources belonging to all three of life’s domains provide snapshots of covalent nucleotidyltransferase family members at different points along their reaction pathways9; 10; 11; 12; 13; 14; 15; 16; 17; 18; 19; 20; 21; 22; 23. The overarching lesson from structural comparisons and comprehensive mutational analyses is that the substrate binding and chemical steps of the ligation and capping reactions are coupled to global and local changes in enzyme structure. The global changes entail massive protein domain movements (on the order of 50 to 90 Å) that, in the case of DNA ligases, transit between “open”, “closed”, and “DNA-clamped” conformations. The local changes entail remodeling of the atomic contacts in the active site and conformational changes in the adenosine nucleoside.

The DNA-clamped protein conformation is exemplified in the crystal structures of E. coli LigA•AppDNA15, human Lig1•AppDNA20, and ChVLig-AMP•pDNA complexes9. These clamped structures are stabilized by a network of ionic and hydrogen bonding contacts between the enzyme and the DNA backbone phosphates flanking the nick. The clamped structures undoubtedly correspond to bona fide reaction intermediates, insofar as the ChVLig-AMP•pDNA complex was shown to catalyze nick sealing in crystallo when provided with a divalent cation cofactor9. Although there is no crystal structure available for a true step 1 Michaelis complex of a DNA ligase bound to ATP, the structure of Chlorella virus capping enzyme (ChVCE) bound to GTP exemplifies the closed conformation of the Michaelis complex, in which the OB domain covers the nucleotide-binding pocket in the NTase domain and engages the pyrophosphate leaving group24. The crystal structure of a Sulfolobus solfataricus DNA ligase•ATP complex closely mimics the expected Michaelis complex, albeit with the OB domain of a neighboring ligase protomer closing in trans over the ATP-bound NTase domain21.

The OB domain must move away from the NTase domain after the ligase-AMP intermediate is formed, so as to expose a nick-binding surface immediately above the AMP phosphate (where step 2 chemistry occurs). This open domain arrangement is seen in two different crystal structures of the free ChVLig-AMP intermediate18; 19. Comparison to the structure of ChVLig-AMP bound to nicked DNA9 reveals that nick recognition triggers rotation and movement of the OB domain and a disorder-to-order transition of the latch module that forms the protein clamp.

Whereas the step 1 Michaelis complex and the DNA-clamped ligase-adenylate are conformationally fixed by virtue of contacts to substrate phosphate groups, the free ligase-adenylate and the ligase apoenzyme have fewer conformational constraints, as evinced by the broad spectrum of domain arrangements adopted in crystal structures of ligases and ligase-AMP intermediates. These arrangements vary from tightly closed (i.e., with the OB domain sitting over the NMP pocket of the NTase domain)13 to wide open (with the OB domain splayed away from the NTase domain)18. Although static crystal structures underscore the conformational flexibility of DNA ligases, they have a number of shortcomings. The domain arrangement seen in any particular crystal structure is likely to be biased by crystal packing constraints and lattice contacts, making it impossible to judge to what extent that crystallographic conformation applies to the enzyme in solution. Moreover, the crystal structures provide little information about conformational dynamics.

Here we apply solution NMR spectroscopy to address this knowledge gap and complement the extensive structural and functional data available for Chlorella virus DNA ligase. ChVLig has pluripotent biological activity18 and its size (34 kDa; 298-amino acids) makes it an attractive model for NMR studies of the ATP-dependent ligase family. We recently obtained complete assignments of main chain and side chain Cβ resonances of the covalent ChVLig-AMP intermediate25. In the present study we investigate the conformational dynamics of ChVLig-AMP in solution via an analysis of backbone 15N spin-relaxation and 15N,1HN residual dipolar couplings. We find extensive conformational sampling by ChVLig-AMP on multiple timescales representing both inter- and intra-domain flexibility. In addition, we characterize local and global changes in structure and dynamics in ChVLig-AMP induced by phosphate, a putative mimetic of the nick 5′-phosphate.

Results and Discussion

Chemical shift perturbations in ChVLig-AMP triggered by phosphate anions

Atomic contacts to phosphate anions underlie all facets of ChVLig-AMP function. The enzyme interacts with the β and γ phosphates of ATP during the ligase-adenylylation reaction, with the nick 5′-phosphate as a sensor of DNA damage, and with multiple DNA backbone phosphates on the broken and continuous DNA strands flanking the nick during formation of the ligase clamp around the DNA duplex9. To gain insights to the interactions of ChVLig-AMP with phosphate anions in solution, we monitored chemical shift changes for backbone 15N and 1HN in a series of 15N,1H TROSY spectra recorded with increasing concentrations of phosphate. The chemical shift perturbations caused by phosphate were large (Δδmax = 0.47 ppm for 50 mM phosphate, see Eq. 3) and localized to the NTase domain (Fig. 1). A significant chemical shift perturbation (defined asΔδ > 0.1 ppm) was observed for 21 residues (T4, L7, L8, K27, I28, D29, G30, R32, E67, I68, Y96, D99, Y100, L137, V140, E161, M164, I165, R166, L184 and K186), most of which are located in the active site. By contrast, only two residues (L8 and I28) displayed Δδ values > 0.1 ppm in response to raising the NaCl concentration from 150 mM to 500 mM. The rest of the perturbations detected in high salt were of small magnitude and distributed evenly across the primary structure. Thus, we surmise that the structural changes triggered by phosphate anions are specific and relevant to the ligase mechanism, as discussed below.

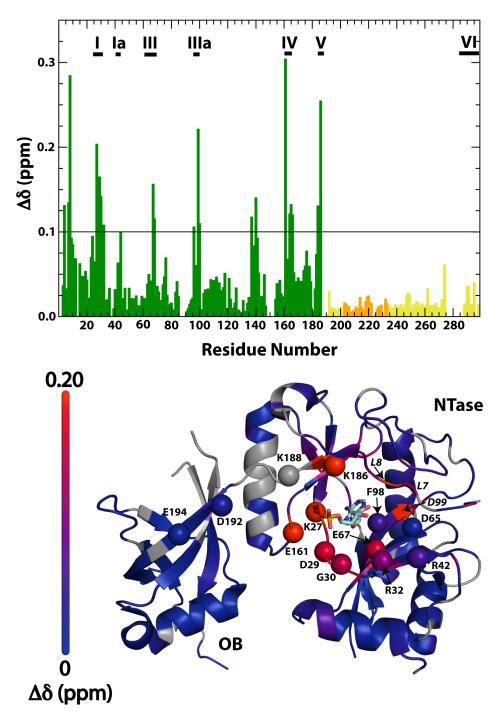

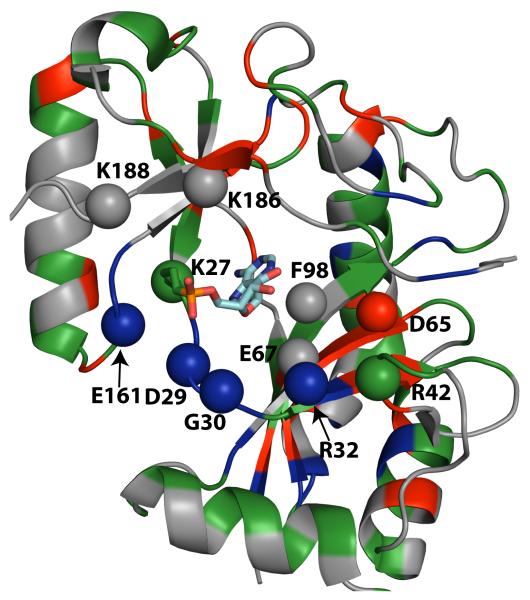

Fig. 1.

Chemical shift changes induced in ChVLig-AMP in the presence of increased phosphate concentration. Chemical shift changes seen in the presence of 50 mM phosphate are plotted against residue number (top). Scaled chemical shift differences were calculated using Eq. (3). The conserved nucleotidyltransferase motifs are denoted by horizontal bars and labeled. The grey horizontal line indicates the Δδ significance threshold. Δδ values representing the NTase, OB and latch domains are colored green, yellow and orange respectively. Variations in Δδ values are mapped onto the structure of ChVLig-AMP (bottom). Residues at the active site deemed crucial for function (mutation of these residues reduced activity to less than 7% of wild-type enzyme)(Shuman, unpublished) are represented by balls. Other residues undergoing large chemical shift perturbation are italicized. Residues for which data that could not be analyzed due to resonance overlap or missing assignments are shaded grey.

The large chemical shift changes induced by 50 mM phosphate were clustered in nucleotidyl transferase motifs I (27K[AMP]IDGIR32;, Δδ = 0.20, 0.15, 0.17, 0.14 and 0.11 ppm for K27-AMP, I28, D29, G30 and R32, respectively), III (63GSDGEIS69; Δδ = 0.16 and 0.12 ppm for E67 and I68), IIIa (95YYWFDY100; Δδ = 0.11, 0.22 and 0.11 ppm for Y96, D99 and Y100), IV (161EGVMIR166; Δδ = 0.31, 0.12, 0.13 and 0.12 ppm for E161, M164, I165 and R166) and V (184LLKMK188; Δδ = 0.13 and 0.26 ppm for L184 and K186) that comprise the adenylate binding pocket. It is likely that the structural changes elicited by phosphate in solution reflect adoption of an active site conformation that mimics the state of ChVLig-AMP crystallized with a sulfate anion bound in the active site19. The sulfate anion is located adjacent to the AMP phosphate in a position that mimics the nick 5′-phosphate in the ligase-AMP•DNA complex9.

There is evidence from static crystal structures that the atomic contacts in the ligase active site are remodeled during sequential steps of the reaction pathway in tandem with conformational changes in the adenylate nucleotide, e.g., entailing rotations about the adenosine glycosidic bond during the step 1 transition from ligase•ATP to ligase-AMP19; 23. There is less known about the conformation dynamics of ligase-AMP itself. The NMR data bear on this issue by pinpointing specific local changes in ChVLig-AMP in solution in response to phosphate, that could plausibly mimic what happens when the nick 5′ phosphate enters the active site to initiate step 2 of the sealing pathway (or when pyrophosphate re-enters the active site in the case of the reverse step 1 reaction). The results extend and fortify the relevance of the subtle differences in active site conformation noted in comparing structures of ChVLig-AMP crystallized in the presence and absence of sulfate18; 19. The positions and/or contacts of the ribose sugar, K27-AMP, R32, E161, and K186 side chains and part of the motif I main chain were shifted in the presence of sulfate anion; changes in these same protein constituents feature prominently in the NMR data obtained presently.

For example, R32 controls the ribose orientation in the sulfate-bound ChVLig-AMP by hydrogen bonding with the O2′ atom. R32 is itself held in place by a salt bridge to D65 and a hydrogen bond to the L7 main chain carbonyl. Here we find that upon phosphate binding, R32 (Δδ = 0.11 ppm), L7 (Δδ = 0.14 ppm) and L8 (Δδ = 0.29 ppm) underwent significant chemical shift changes. The L8 amide experienced a downfield shift of 1.4 ppm in the 15N dimension, consistent with the modification of the hydrogen bond strength involving the preceding carbonyl group. Taken together these observations point towards a direct involvement of the R32 side chain in the structural modification induced by phosphate.

Inspection of the chemical shift changes as a function of phosphate concentration revealed the following features. Steady changes in Δδ values were seen until a plateau was reached at 1-2 mM phosphate, although no major reductions in peak intensity were detectable. Further changes in Δδ values and obvious peak doublings were noted as phosphate was increased from 10 to 60 mM (see Fig. 2 for representative spectra for K27-AMP and E161, with peak doublings indicated by arrows). The peak doublings at high phosphate concentrations were observed for all of the residues that displayed large chemical shift perturbations in the presence of phosphate. This behavior is consistent with a mechanism in which the initial binding of phosphate in a fast exchange regime is followed by a slow conformational change involving the phosphate-bound ligase. This scenario is very well illustrated by the simulations of Kovrigin and corresponds to his U-RL model (Evgenii Kovrigin, Keystone Symposium on Protein Dynamics, Allostery and Function, June 2009).

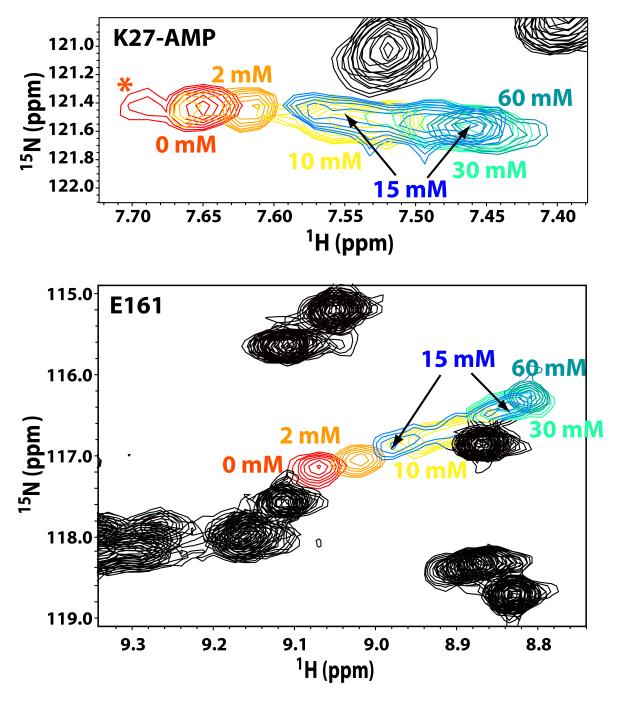

Fig. 2.

The conformational exchange processes occurring at the catalytic site of ChVLig-AMP in the presence of increased amounts of phosphate. Resonance doubling was seen for most residues that display large chemical shift changes (see Fig. 1) at the catalytic site for phosphate concentrations around 15 mM. Representative examples (K27, top and E161, bottom) are shown. A shoulder (indicated by the “*”) was seen for the resonance corresponding to the adenylated K27 residue, reflecting the presence of a minor species in solution in the absence of phosphate.

A comparison of the crystal structures of ChVLig-AMP with and without a sulfate bound in the active site reveals an anti conformation for the adenosine nucleoside in the presence of sulfate that is shifted partially towards a syn conformation when sulfate in absent18. The adenosine remains in an anti conformation in the structure of ChVLig-AMP bound at a DNA nick9. In light of the observation that all of the large chemical shift perturbations involved residues that interact with the AMP moiety rather those that directly coordinate phosphate (or sulfate as in the crystal structure - R42 and R176 that coordinate sulfate did not reveal large shift changes) and the fact that large changes were observed in the chemical shifts of E67 and R32 (implicated in ribose interactions before and after execution of step 1, respectively), it is tempting to speculate that the peak doubling at high phosphate concentration was due to the slow isomerization of the AMP moiety from a halfway syn-like to a fully anti conformation rather than the presence of a second phosphate binding site on ChVLig-AMP. In the crystal structure of T7 ligase in complex with ATP23, representing the state of the system prior to the ligase adenylylation step, the AMP moiety is in a fully syn conformation. In principle, kinetic parameters of phosphate binding and isomerization of the AMP moiety may be extracted using the chemical shift perturbation data obtained here when combined with the measurement of relaxation dispersion26 and zz-exchange27 and subsequent fits to a three-site exchange model as illustrated by Sugase et. al.28. We defer this detailed analysis for a future study.

The local changes in active site conformation induced by 50 mM phosphate act as foil to the absence of significant chemical shift perturbation (see Fig. 1) at any of the residues in the OB domain, latch module, and elsewhere in the NTase domain that engage in atomic contacts to the DNA phosphodiester backbone when ChVLig-AMP is clamped around a duplex nick. We surmise that free phosphate anion does not mimic the interactions of ligase with the DNA phosphates flanking the nick. Nonetheless, we will report below that phosphate can affect domain dynamics, locally and globally.

Analysis of 15N,1HN residual dipolar couplings – evidence of domain motion

In the absence of stabilizing interdomain contacts, the relative orientation of the constituent domains of multidomain proteins is strongly influenced by crystal packing forces and may differ substantially from that in solution29; 30. In spite of the availability of two crystal structures of ChVLig-AMP in the absence of DNA18; 19, both of which have open domain arrangements with the NTase and OB domains splayed apart, we cannot discount the influence of crystal packing interactions that influence or bias the interdomain orientation. Therefore we interrogated ChVLig-AMP domain orientations in solution by measuring and analyzing the backbone 15N,1HN residual dipolar couplings (RDCs).

RDCs31 have been utilized extensively to assess the time-averaged orientation of weakly interacting constituent domains in solution32; 33. A variety of media have been employed in order to obtain the required weak alignment of the protein of interest with the external magnetic field31. In our initial screen for suitable orienting media, we found that ChVLig-AMP was unstable at high concentrations in DMPC/DHPC bicelles34 and in polyethyleneglycol-based systems35. Spectra in suspensions of Pf1 filamentous phage36 displayed large chemical shift changes and extensive line broadening suggesting significant interactions with the orienting medium. By contrast, excellent sample stability and spectral quality was achieved using uniformly stretched polyacrylamide gels37 that provide a more inert environment. 15N,1H HSQC and TROSY experiments collected in an interleaved manner38 utilizing 6% (w/v) acrylamide gels yielded RDCs in the ± 20 Hz range with an experimental precision of ±2 Hz. This approach provided greater precision than the inphase/antiphase (IPAP) scheme39, which was complicated by unfavorable line-width in the anti-TROSY component.

The analyzed data comprised 111 1-bond 15N,1HN RDC values belonging to ordered parts of the protein (77 from the NTase domain and 34 from the OB domain; see Table 1). Using the experimental RDCs and the crystal coordinates of ChVLig-AMP at 2.0 Å resolution from the PDB:IFVI19, the Saupe order tensor was obtained using single value decomposition (SVD)40 and then used to derive a set of “theoretical” RDCs. Excellent correlation between experimental and calculated data was found when data for the individual domains were analyzed separately. The values of the correlation coefficients (R) were 0.95 and 0.97 for the NTase and OB domains respectively and the corresponding quality factors were 0.24 and 0.22 (see Table 1). However, when the entire two-domain crystal structure of ChVLig was used to fit the RDCs, extremely poor agreement was obtained between the calculated and measured RDCs as reflected in the corresponding R and Q values (Table 2). Even when the measured RDC values with the largest experimental errors were arbitrarily disregarded, R and Q values could not be improved beyond 0.86 and 0.45 respectively, suggesting that whereas the structures of the individual NTase and OB domains were quite similar in crystallo and in solution, the domain orientation was not.

Table 1.

Saupe order tensor parameters determined from 15N,1HN residual dipolar couplings for ChvLig-AMP measured in 6 % polyacrylamide gel.

| 150 mM NaCl | 300 mM NaCl | 150 mM NaCl + 50 mM PO4 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NTase | OB | NTase | OB | NTase | OB | |

| Sxx (×104) | −2.24 ± 0.33 | 3.83 ± 0.54 | −2.71 ± 0.39 | 4.47 ± 0.84 | −0.44 ± 0.21 | 2.13 ± 0.36 |

| Syy (×104) | −6.13 ± 0.33 | 8.35 ± 0.47 | −9.38 ± 0.38 | 11.65 ± 0.77 | −4.41 ± 0.20 | 6.89 ± 0.31 |

| Szz (×104) | 8.36 ± 0.25 | −12.18 ± 0.54 | 12.10 ± 0.35 | −16.12 ± 0.77 | 4.85 ± 0.16 | −9.03 ± 0.27 |

| GDO (×104) | 8.66 ± 0.33 | 12.47 ± 0.54 | 12.69 ± 0.39 | 16.66 ± 0.84 | 5.37 ± 0.21 | 9.44 ± 0.36 |

| Da (Hz) | 9.02 ± 0.27 | −13.15 ± 0.59 | 13.04 ± 0.39 | −17.39 ± 0.83 | 5.24 ± 0.17 | −9.74 ± 0.29 |

| 0.47 ± 0.08 | 0.38 ± 0.08 | 0.56 ± 0.06 | 0.45 ± 0.09 | 0.83 ± 0.09 | 0.53 ± 0.08 | |

| N | 77 | 34 | 84 | 39 | 80 | 34 |

| RMS (± Hz) | 3.32 | 4.14 | 4.61 | 6.78 | 2.23 | 2.20 |

| R | 0.95 | 0.97 | 0.95 | 0.95 | 0.95 | 0.99 |

| Q | 0.24 | 0.22 | 0.23 | 0.27 | 0.27 | 0.16 |

| P | −0.15 | 0.20 | −0.31 | |||

| Θ (°) | 98.6 | 78.5 | 108.1 | |||

N denotes the number of 15N,1HN RDCs analyzed.

Table 2.

Comparison of fitting parameters for aligned models and the crystal structure of ChVLig-AMP

| 150 mM NaCl | 300 mM NaCl | 150 mM NaCl + 50 mM Phosphate |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model | 1FVI | Model | 1FVI | Model | 1FVI | |

| N | 111 | 111 | 123 | 123 | 114 | 114 |

| RMS (± Hz) | 4.89 | 8.11 | 6.73 | 10.63 | 3.38 | 6.57 |

| R | 0.92 | 0.77 | 0.92 | 0.80 | 0.93 | 0.71 |

| Q | 0.32 | 0.62 | 0.31 | 0.56 | 0.29 | 0.62 |

An inspection of the orientation of the order tensor axes for the individual domains revealed that the direction of highest order (orientation of Szz where |Szz|≥|Syy|≥|Sxx) for the two domains were not coincident. The normalized scalar product (P, see Table 1), as defined by Sass et. al.41 for the alignment tensors of the two domains were close to zero, indicating that the direction of highest order of the two tensors was essentially orthogonal to each other. Also, the temporal averaging characteristics of the individual domains in solution, as reflected in the nature of the principal components of their individual alignment tensors (see Table 1), were quite different. The NTase domain was best described by a prolate orientation tensor (Szz > 0), whereas the OB domain was best represented by an oblate tensor (Szz < 0). This analysis suggested that ChVLig-AMP did not behave as a single rigid body in solution and possessed a substantial amount of interdomain mobility. In the absence of domain motions, the principal components of the individual alignment tensors would be the same in both sign and magnitude.

A simple way to assess the extent of interdomain motion, is to compare the generalized degree of order (GDO, see Table 3)42 for the two domains. The GDO reflects the overall degree of alignment of the individual domains in the aligning medium, and would be expected to be the same for both domains in the absence of interdomain motion. The ratio43, GDOint=GDONTase/GDOOB is 0.69 ± 0.04, which translates to Lipari-Szabo order parameter (S2) value of 0.48. This value could result from isotropic wobbling in a cone of semi-angle 39 ± 3° or be obtained from a simple anisotropic motional model such as rotational jumps of 57 ± 5° between two-states of equal population44. However, simple motional models would most likely be misleading in the absence of further evidence of the nature and timescale of motion. Given that the spin-spin relaxation rates (R2, see below) of the individual domains were similar, we would expect this motion to occur on the μs-ms timescale. Additional evidence that hinted towards motion of this nature was the fact we were unable to assign resonances corresponding to many of the residues that form the interface between the NTase and OB domains – including the interdomain linker, part of helix 5 in the NTase domain, and part of β-strand 5 in the OB domain – most likely due to extensive line broadening resulting from rigid body motion of the two domains with respect to each other on the slow timescale25. Another factor in addition to interdomain motion that could impact the differences in the overall nature of the order tensors of the individual domains (prolate for the NTase and oblate for the OB domain) is that the flexible 30-amino acid latch module might modify the hydrodynamic and hence alignment properties of the OB domain.

Table 3.

Summary of 15N relaxation data for ChVLig-AMP under different buffer conditionsa

| 150 mM NaCl | 300 mM NaCl | 150 mM NaCl + 50mM phosphate |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 600MHz | 800 MHz | 600 MHz | 800 MHz | |

| R1 (sec−1) | 0.72 ± 0.2 (0.66 ± 0.06) |

0.57 ± 0.3 (0.49 ± 0.07) |

0.65 ± 0.3 (0.59 ± 0.1) |

0.55 ± 0.2 (0.48 ± 0.06) |

| R2 (sec−1) | 27.6 ± 8.4 (28.9 ± 3.7) |

35.6 ± 11.6 (36.9 ± 5.6) |

27.9 ± 10.7 (28.1 ± 6.8) |

35.0 ± 10.6 (36.3 ± 4.3) |

| {1H}-15N NOE | 0.68 ± 0.2 (0.71 ± 0.1) |

0.77 ± 0.2 (0.80 ± 0.1) |

0.71 ± 0.2 (0.74 ± 0.1) |

0.78 ± 0.2 (0.80 ± 0.1) |

10% trimmed averages in brackets.

Relative orientation of the NTase and OB domains in solution

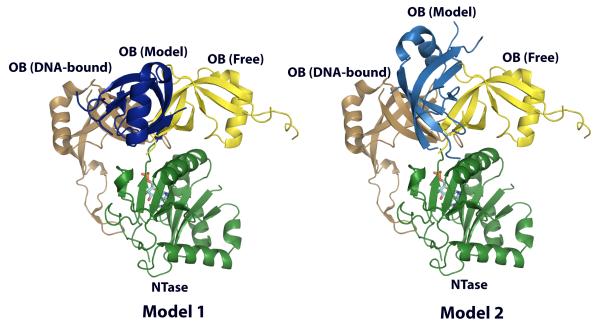

In order to determine the time-averaged orientation of the NTase and OB domains in solution, we aligned the individual alignment tensor axes by matching the orientations of tensor components with similar sign and magnitude32 – the Szz, Sxx and Syy axis of the NTase domain were matched with the Syy, Sxx, Szz axis of the OB domain in that order. This was achieved in three steps – (1) rotation of NTase and OB domains from the crystallographic frame into the principal axis frame of the NTase domain, (2) rotation of the OB domain into its own principal axis frame while keeping the NTase domain fixed, and (3) rotation of the OB domain by 90° about the x-axis of the new frame. However, this procedure leads to 4 degenerate solutions for the interdomain orientation coordinate corresponding to 180° rotations of the OB domain around two orthogonal axes30; 33. Of these four possible structural models, two could easily be eliminated based on steric and chemical-bonding considerations. The interdomain arrangement seen in the two valid models (Fig. 3) derived from the RDC analysis was significantly different from that observed in ChVLig-AMP crystal structures18; 19. The degree of closure between the two domains in solution was intermediate between that seen in the crystal structures of ChVLig-AMP with or without nicked DNA9; 18; 19. This raises the possibility that the conformational dynamics discussed above could be the result of sampling of minor population of bound-like conformers in solution even in the absence of DNA. DNA binding would then be expected to cause a shift in population towards the bound-like forms that would then constitute the major population. Evidence of population shift upon binding has been found in other systems45.

Fig. 3.

The two solutions for the relative orientation between the NTase and OB domains in ChVLig-AMP consistent with the experimental one-bond 15N-1H residual dipolar couplings and chemical bonding constraints. The NTase domains (green) of the models determined from solution NMR data and those from the crystal structures of free ChVLig-AMP (1FVI) and that bound at a nick (2Q2T) are overlaid. The OB domains of the models are in shown in dark (model 1, left) and light (model 2, right) blue along with those of the free (yellow) and DNA-bound (gold) forms of the enzyme. Both models display a domain orientation that is intermediate between the free and DNA bound forms. The AMP moiety is shown in stick representation.

Next we analyzed the data for the NTase and OB domains simultaneously, using each of the two models obtained above. This analysis produced far better agreement between experimental and calculated RDCs compared to the intact crystal structure (R = 0.92, Q = 0.31, see Table 2).

In order to further test the reliability of these two solutions, the measured RDC values were converted into orientation restraints and introduced into a simulated annealing protocol (see Materials and Methods section) whereby the structures of the individual domains were fixed using a large number of distance restraints (pseudo-NOEs calculated from the crystal structure) while the interdomain linker and those regions for which no electron density was seen in the crystal structure were left unconstrained. These simulations confirmed that the two solutions obtained by manual rotations, as described above, corresponded to the minima of the orientational energy functions whose boundaries were now more clearly visible upon sampling of the accessible conformational space by the molecular dynamics protocol. No other structural minima were detected irrespective of the nature of the starting interdomain orientation, and the system quickly converged towards the two previously described solutions.

Influence of phosphate on domain orientation

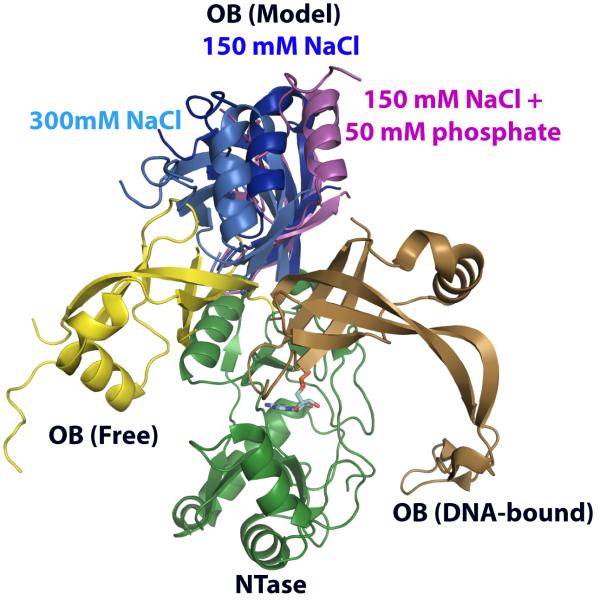

Two additional sets of 15N,1HN RDCs were measured in NMR buffer containing either 150 mM NaCl plus 50 mM phosphate or 300 mM NaCl, and the data were compared to those obtained in 150 mM NaCl. No significant changes in the overall nature of the Saupe order tensors for the NTase or OB domains were noted with increased salt (see Table 1) though slight changes in the orientations of the tensors for the individual domains led to a marginally more open structure (Fig. 4). However, in the presence of phosphate, significant changes were noted in the nature of the order tensor of the NTase domain. The degree of anisotropy (η) of the alignment tensor of the NTase domain approached its maximal value of 1 (see Table 1) since the most positive (Szz) and the most negative (Syy) components of the alignment tensor were almost equal in magnitude. This modification in alignment properties is not due simply to ionic strength effects and is concordant with our findings that all the significant phosphate-induced chemical shift changes were localized to the NTase domain. Phosphate also resulted in a more closed structure, as depicted in Fig. 4. This behavior is in line with that seen in the structures of ChVLig-AMP crystallized with or without a sulfate in the active site. The sulfate-bound structure adopted a more closed form resulting from a 9.5 Å movement of the OB domain18.

Fig. 4.

Effects of salt and phosphate on interdomain orientation in ChVLig-AMP. Positions of the OB domain in the presence of 150 mM NaCl (dark blue), 300 mM NaCl (light blue) and 150 mM NaCl + 50 mM phosphate (pink). Also shown are the positions of the OB domain in the free (yellow) and DNA-bound (gold) forms of ChVLig-AMP. The NTase domains (green) of the various structures have been overlaid. A slightly more open structure, closer to the free form is obtained on simply increasing the ionic strength. In contrast, a more closed structure, closer in conformation to the DNA-bound form is obtained in the presence of phosphate, suggesting increased sampling of a “closed-like” conformation.

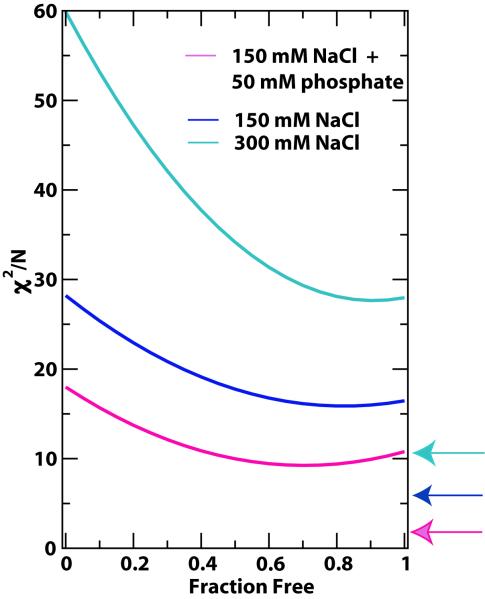

As mentioned previously, the phosphate anion is a likely mimetic of the nick 5′-phosphate and the phosphate-free ChvLig-AMP may be considered to represent the state of the enzyme prior to nick recognition18. Thus it is plausible that the remodeling of the active site and the movement of the AMP triggered by phosphate/sulfate-binding or nick recognition is accompanied by a population shift towards a more closed domain orientation. In order to test this population shift hypothesis, we used a “weighted χ2” approach (see Materials and Methods section) designed to evaluate the possible contributions of closed conformers similar to the DNA bound forms in the solution ensemble of ChVLig-AMP in the absence of DNA. The minimum χ2 function corresponds to almost pure DNA-free open form (PDB ID: 1FVI) of the enzyme (> 0.9 both at 150 mM and 300 mM NaCl), though a shift of the minimum (to 0.7) of the function is seen in the presence of phosphate towards the more closed, DNA-bound like (PDB ID: 2Q2T) form (Fig. 5). Additional evidence for increased interdomain mobility was obtained from the reduced GDOint value of 0.57 ± 0.03 in the presence of phosphate. This would correspond to an increase in the jump amplitude from 57 ± 5° (see above) to 71 ± 5°.

Fig. 5.

Results of the weighted χ2 approach. Variation in the difference between the experimental and calculated RDCs (χ2/N determined using Eq. 2) upon including increased amounts of the DNA-bound conformation. Data for 150 mM NaCl (blue), 300 mM NaCl (cyan) and 150 mM NaCl + 50 mM phosphate (pink) are shown. The data indicate increased sampling of a “bound-like” conformation in the presence of phosphate. The overall χ2/N values were still significantly higher that that obtained when considering the NTase and OB domains individually (average χ2/N values indicated by the arrows using the same color scheme as the curves), indicating that the model considered – two-state switching of the domain orientation between rigid free (1FVI) and rigid bound conformation (2Q2T) was an oversimplification of the nature of dynamics seen at the domain interface.

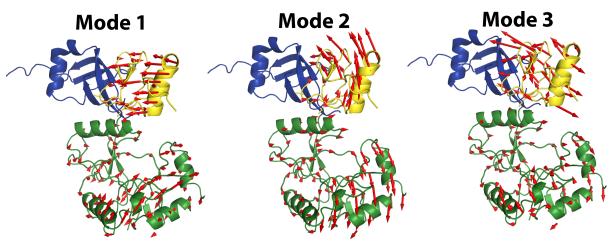

The results of the RDC analysis suggested domain motion on the μs-ms timescale and increased sampling of DNA-bound like closed states in the presence of phosphate. We performed a normal modes analysis (NMA) of ChVLig-AMP using the elNémo server (http://www.igs.cnrs-mrs.fr/elnemo/)46 to investigate whether the directionality of the lowest frequency normal modes was compatible with such motion. Three of the lowest frequency normal modes (normalized frequencies of 1.0, 1.11 and 1.35, the corresponding frequency for the next normal mode was 2.46), shown in Fig. 6, revealed the opening/closing and twisting motions accessible to the domains. Mode 1 depicted in Fig. 6 would indeed be compatible with a transition from the open form in the absence of DNA to the closed DNA-bound form.

Fig. 6.

Three lowest frequency normal modes for ChVLig. Vector field diagrams representing three of the lowest frequency normal modes (the global modes representing the translational and rotational degrees of freedom have been excluded) with normalized frequencies of 1.00, 1.11 and 1.35 respectively, are shown. These modes represent highly correlated motions with collectivity values63 of 0.61, 0.53 and 0.48 respectively. Normal modes were calculated using the elNémo server (http://www.igs.cnrs-mrs.fr/elnemo/).

As mentioned earlier, phosphate could also be considered a mimic for the pyrophosphate generated after transfer of AMP from ATP to K27 during step 1. Although there is no structure available of the ATP-bound ChVLig, the structure of GTP-bound Chlorella virus RNA capping enzyme is the best approximation of the step 1 Michaelis complex of DNA ligase bound to ATP24. Its key features include a ~180° rotation of the OB domain and closure of the OB domain over the NMP-binding pocket so that nucleotidyl transferase motif VI at the C-terminus of the OB domain engages the NTP β and γ phosphates and orients the pyrophosphate leaving group apical to the attacking motif I lysine. Motif VI is essential for the ChVLig adenylylation reaction47, but is not close to the catalytic site in any of the available crystal structures of ChVLig-AMP. However, in one of the two models that are obtained from our RDC analysis (model 2 in Fig. 3), motif VI is on the same face as the catalytic site and domain closure would allow it to access the catalytic cleft from this position. Mode 2 illustrated in Fig. 6 is compatible with such a rearrangement. It is therefore conceivable that a closed domain orientation similar to that of the step 1 product complex (ChVLig-AMP•pyrophosphate) is also sampled in the solution state ensemble of ChVLig-AMP, especially in the presence of phosphate.

Intradomain dynamics

While the analysis above provided information on large scale dynamics at the domain level, we relied on the analysis of backbone 15N relaxation data to obtain information on local and semi-local dynamics on the fast (ps-ns) and slow (μs-ms) timescale. Complete sets of TROSY-based 15N R1, R248 and {1H}-15N NOE data49 were collected for ChVLig-AMP in 150 mM NaCl (600, 800 MHz), 300 mM NaCl (600 MHz) and 150 mM NaCl plus 50 mM phosphate (800 MHz). These results are summarized in Table 3. The relaxation data immediately confirmed that the latch comprising residues L203 to V232 and the C-terminal motif VI peptide were highly dynamic, displaying fast motions on the ps-ns time scale. The latch is disordered in the free ligase, but becomes ordered in the presence of nicked DNA and makes multiple contacts with the DNA phosphates across the major groove on the face of the helix opposite the nick9.

An analysis of the relaxation data to characterize the nature of the rotational diffusion tensors for the individual domains30 confirmed that their respective rotational correlation times were essentially undistinguishable (~22 ± 2 ns). Both domains behaved like axially symmetric rotors with relatively low rotational anisotropy (~1.2, data not shown). It has been noted that large, unstructured elements (as in the latch emanating from the OB domain) add a hydrodynamic drag and lead to a larger effective correlation time50. In order to query whether the similarity of the rotational correlation times obtained for the two domains (despite their size difference) might be fortuitously due to the increased hydrodynamic drag on the OB domain (and not due to their hydrodynamic coupling), we performed separate hydrodynamic calculations on the intact NTase and an OB domain structural ensemble (see Materials and Methods) using the HYDRONMR program51. A rotational correlation time of 12.8 ns was obtained for the NTase domain and the corresponding value for the OB domain ensemble was 7.9 ± 0.4 ns. This confirmed that the two domains did not tumble independently and were hydrodynamically coupled given that the correlation time for the intact protein obtained experimentally was 22 ns. A point to be made here is that, in our analysis, we assumed that the dynamics of the latch occurred on a timescale slower than the overall tumbling i.e. each structure in the OB domain ensemble was rigid. This is certainly not true (based on the {1H}-15N NOE values the latch moves on the sub-ns timescale) and our present approximation leads to an overestimation of the values of the estimated correlation times52, and therefore reinforces our point that the hydrodynamic drag alone cannot explain the increased correlation time of the OB domain.

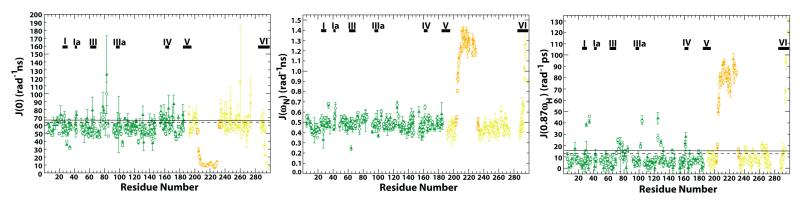

As discussed above, the ensemble of ChVLig-AMP solution structures may be considered to consist of several slowly interconverting conformers of different shapes. In the absence of structural knowledge for all the conformers and their relative populations (determined by the exchange timescale), we decided to rely on the reduced spectral density function approach30; 53 to analyze our relaxation data in terms of fast (ps-ns) and slow (μs-ms) microdynamics instead of the Lipari-Szabo 54; 55 model-free approach commonly employed for single domain systems. The values of the reduced spectral density functions at 0, ωN and 0.87ωH frequencies are plotted against residue number in Fig. 7. Because the values of J(ωN) have a complicated dependence on the global tumbling as well as local dynamics, their direct interpretation is difficult. This is in contrast to J(0) and J(0.87ωH), the former being dominated by the effects of overall rotational diffusion (and chemical exchange on the slow timescale, where present) and the latter by those of very fast local motions. Thus, we comment only on the J(0) and J(0.87ωH) (referred to as J(ωH) from hereon forward) values below.

Fig. 7.

Reduced spectral density functions for ChVLig-AMP. Reduced spectral density functions J(0), J(ωN) and J(0.87ωH) calculated from R1, R2 and {1H}-15N steady-state NOE values measured at 800 MHz in the absence (closed symbols) and presence (open symbols) of 50 mM phosphate are plotted as a function of residue number. The conserved nucleotidyltransferase motifs are denoted by horizontal bars. The thresholds (see text) used for J(0) and J(0.87ωH) without (solid line) and with phosphate (dashed line) are indicated. These thresholds are: J(0): without phosphate, 66.4 ns/rad; with phosphate, 63.8 ns/rad. J(0.87ωH): without phosphate, 15.5 ps/rad; with phosphate, 12.9 ps/rad.

In order to discern the residues that were dynamic on the sub-ns timescale we selected those that displayed elevated J(ωH) values, defined as twice the standard deviation above the 20% trimmed mean (8.3 ± 3.6 ps/rad, threshold taken to be 15.5 ps/rad). Not surprisingly, most of the residues undergoing fast motions as manifested in their greatly elevated J(ωH) values (and reduced J(0) values, see Fig. 7) belonged to the latch region (average 75.2 ± 24.8 ps/rad). In addition, some loop residues also displayed high J(ωH) values (though smaller in magnitude than those in the latch region). In general, excluding the latch region, a majority of the residues undergoing fast motions were located in the NTase domain. It was noteworthy that G30, the main chain amide of which directly coordinates the 5′-PO4 of the nick9, was dynamic (38.4 ± 1.5) on the fast timescale.

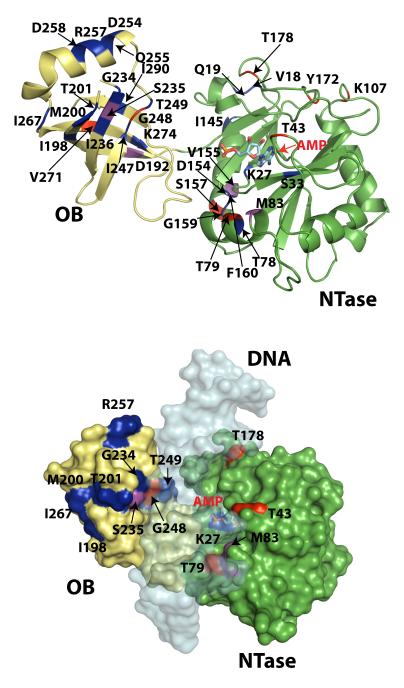

Most of the residues that displayed significantly enhanced J(0) indicative of chemical exchange (see Fig. 8, defined as in the case of J(ωH) above, 20% trimmed mean 57.7 ± 4.3 ns/rad, threshold 66.4 ns/rad) were, like the J(ωH) values, also located on the NTase domain, implying that the NTase domain was dynamic both on the fast and the slow timescales. These residues were located in loops and in regions that contribute to the DNA binding surface, including helix 3. High J(0) values were also identified on, or close to, helix 5 (145ITELLQYERDVLS157) that, in the crystal structure of free ChVLig-AMP, is part of the interface between the NTase and OB domains; these included V155 and S157. As mentioned earlier, resonances corresponding to the 149LQYER153 peptide of this helix could not be assigned, most likely due to chemical exchange. The other residues that displayed elevated J(0) values included T43 that plays a role in clamp closing, completing the encirclement of DNA by ChVLig-AMP99; T79 and M83 that form part of a helix (75FQDTTSAVMTG85) that inserts into the minor groove of DNA, and T178 that sits at the outer boundary of the contact surface of the NTase domain with nicked DNA9. All the residues with elevated J(0) values in the OB domain (D192, S235, G248 and V271) either contact DNA, or are in close proximity to residues that are involved in DNA recognition.

Fig. 8.

Slow dynamics in ChVLig-AMP with and without phosphate represented on the structure of ChVLig-AMP bound to nicked DNA. Residues that displayed μs-ms timescale dynamics as reflected in elevated J(0) values (see main text and legend to Fig. 7) in the absence of (red) and in the presence of (blue) phosphate, are shown on the top panel. J(0) values in pink were indicative of slow dynamics both in the presence and absence of phosphate. Surface plot (bottom panel) of residues that displayed elevated J(0) values as in the top panel. Also shown as a semi-transparent surface, is the bound nicked DNA duplex. For clarity, the latch region (L203-V232) has been removed. Most of the residues that displayed elevated J(0) values in the presence of phosphate on the OB domain were located on the face responsible for DNA binding.

Addition of phosphate lead to changes in the dynamics of ChVLig-AMP on both the fast (ps-ns), and the slow (μs-ms) timescales, with distinct effects on the NTase and OB domains. By contrast, no substantial alterations in dynamics were seen in the presence of high NaCl concentration beyond that expected in response to increased solvent viscosity at high salt. The phosphate-induced changes in the J(ωH) values implied a significant alteration in the dynamics on the fast, ps-ns timescale. For the NTase domain, the motif I residues D29, G30, R32 and the motif IV residues E161 and G162 that form the proximal boundary of the catalytic pocket (see Fig. 9) and make contacts with, or are in proximity to, the AMP moiety all displayed ΔJ(ωH) < 0 (ranging from −5.0 to −24.3 ps/rad), becoming more rigid in the presence of phosphate. It therefore appears that remodeling of the active site by phosphate leads to a rigid (on the fast timescale), better defined orientation of the AMP and active site geometry maintained by the network of interactions with the AMP. This ordering could facilitate the AMP transfer to nicked DNA. However, several residues in or near the nucleotidyltransferase motifs I (S33 and V34), III (S64, D65 and G66) and IV (I165) displayed enhanced dynamics (ΔJ(ωH) > 0) on the fast timescale in the presence of phosphate. These residues were sequentially or spatially proximal to those that underwent phosphate induced ordering. This most likely indicates a redistribution of conformational entropy at and around the catalytic site. Several examples of similar entropy compensation have been provided in the literature50; 56.

Fig. 9.

Changes in high-frequency dynamics reflected by the values of J(0.87ωH) in the NTase domain in the presence of phosphate. Residues that showed no significant changes in high-frequency dynamics are colored green, those for which relaxation data could not be analyzed due to missing assignments, spectral overlap or poor statistics in peak fitting are shaded grey. Residues that showed an increase or decrease in J(0.87ωH) values (beyond the statistical error) are shaded red and blue respectively.

Among the notable changes in fast dynamics induced by phosphate in the OB domain, the residue D192 and the C-terminal motif VI residues I292 and H294 became more rigid in the presence of phosphate. D192 and motif VI play an important role in the ligase adenylylation reaction47. It is possible that the dynamics changes in the OB domain in response to phosphate reflect its mimicry of the pyrophosphate product of step 1.

On the slow timescale, patterns of μs-ms dynamics as manifested in elevated J(0) values (20% trimmed mean 55.9 ± 4.0 ns/rad, threshold 63.8 ns/rad) (see Fig. 8), were also altered in the presence of phosphate. In the NTase domain, elevated J(0) values persisted for the DNA-binding helix residue M83 and appeared for the spatially proximal T78. Elevated J(0) values also appeared for K27-AMP and S33. Whereas the importance of K27-AMP is obvious, it is noteworthy here that S33 lies next to R32, which coordinates the ribose O2′ or O3′ when the AMP is in the anti or syn conformations respectively18. The slow transformation from the anti to the syn conformations for the adenosine moiety in the presence of phosphate has been discussed at length above in the context of phosphate-induced chemical shift changes. It is possible that the slow dynamics being sampled by K27-AMP and its surroundings could be due to the persistence of syn-like conformations that constitute the minor conformer in the presence of phosphate. As in the case of the static chemical shift perturbations, these transient processes involve an aromatic adenine ring system, and exchange contributions to the spin-spin relaxation rate (R2) can be substantial. Modifications in the μs-ms timescale motions were also seen at the domain interface represented by helix 5 – while elevated J(0) values remained for V155, additional high values appeared for I145 (at the N-terminus of helix 5), D154 and in the loop following helix 5 (G159 and F160).

In comparison to the NTase domain, the changes of dynamics on the slow timescale for the OB domain were far more pronounced (see Fig. 8) and elevated J(0) values appeared throughout the DNA-binding face of the OB domain. Several residues that were shown to participate in the formation of intermolecular hydrogen-bonds with DNA through their side chains9, including S235 (also G234 and I236), T249 and K274, themselves displayed elevated J(0) values. S246 and A253 form intermolecular hydrogen bonds with DNA through their main chain amides9, Whereas these residues did not display enhanced J(0) values, the surrounding residues did – I247, D254, Q255, R257, R258. Elevated J(0) values also appeared at I198, M200, T201, and I267, which along with G234, S235 and I236 (discussed above) form a continuous surface on the face that contacts DNA (see Fig. 8).

Overall, it appears that a majority of the residues that displayed elevated J(0) values, indicative of slow dynamics, were in regions involved in making contact with the extended DNA backbone (as opposed to specific recognition of the nick). While several of these residues displayed elevated J(0) values in the absence of phosphate, their number was greatly increased, mostly on the OB domain, upon interaction with phosphate anions. The detailed nature of the dynamically coupled network can only become clear upon a comprehensive analysis of the dynamics of both main chain and side chain nuclei. However, even with limited data, we speculate that these motions represent conformation searches for the rest of the DNA backbone after nick sensing. Recognition occurs in a non-specific way with low affinity suggesting a rugged binding free energy landscape57. Constructs of ChVLig that lack the OB domain are compromised in their ability to bind DNA47. In addition, it is also clear that majority of the binding free energy of ChVLig-AMP towards nicked DNA results from nick recognition, insofar as the enzyme has little affinity towards gapped DNA or an un-nicked continuous duplex 8.

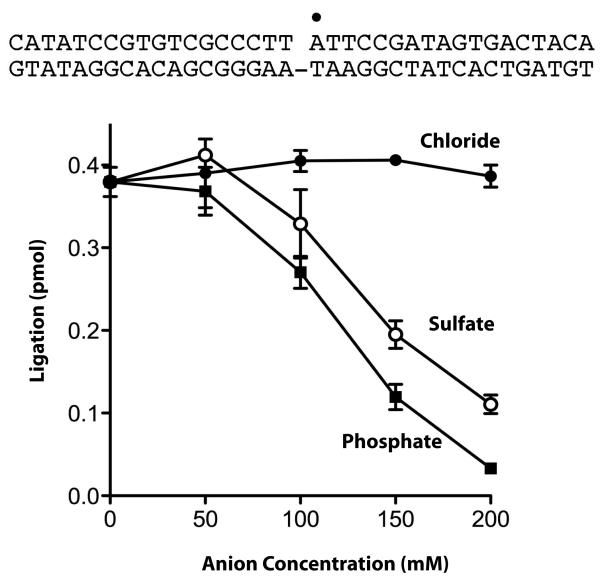

In the studies performed here, we have used phosphate ions as structural mimics of the 5′-PO4 of the nick and proposed that the phosphate-saturated species represents the state of the system immediately after nick-recognition and prior to recognition of the rest of the DNA duplex. Next, we tested whether inorganic phosphate could also be considered a functional mimic of the 5′-PO4 of the nick by assaying its ability to inhibit ligase activity. We found that phosphate anion inhibited nick sealing in a concentration-dependent manner between 50 and 200 mM (Fig. 10). Sulfate was also inhibitory in this concentration range, whereas chloride had no effect up to 200 mM (Fig. 10). These results provide a functional relevance to our NMR studies of the phosphate bound form of ChVLig-AMP.

Fig. 10.

Inhibition of ligase activity by phosphate and sulfate anions. The extent of formation of a sealed 36-mer ligation product from a 36-bp DNA substrate bearing a single 5′-PO4 nick in the presence of increasing concentrations of chloride, sulfate or phosphate. The position of the nick 5′ 32P label is denoted by the “●”. Each datum is the average of ligation values from three anion titration experiments ± the standard error.

In summary, our solution NMR studies highlight the dynamic character of ChVLig-AMP on the global domain level and locally at the catalytic site. We have shown how binding of inorganic phosphate (at the nick 5′-phosphate recognition site) induces both short and long range structural and motional remodeling of the protein. At the active site, most of this reorganization involves amino acids that coordinate the AMP moiety attached to K27. Our data indicate that AMP undergoes a slow conformational transition in the presence of phosphate, resulting in a more rigid geometry on the fast, sub-ns timescale. A more defined orientation of the AMP might facilitate its transfer to the nick 5′-phosphate to form the DNA adenylate intermediate. We find evidence of sampling of closed domain orientations in solution that increases in the presence of phosphate anion, a putative nick 5′-phosphate mimetic. Our results raise the prospect that nick sensing entails a DNA-induced shift in conformation equilibria rather than a pure induced fit model for protein clamp formation.

Materials and Methods

ChVLig preparation

BL21(DE3) cells were transformed with pET-HisSmt3-ChVLig, a T7-based vector encoding full length ChVLig fused to an N-terminal His10Smt3 tag. Recombinant ChVLig proteins produced for NMR analysis were 15N and 2H enriched, or 15N, 13C and 2H enriched, as follows. After an initial overnight growth in unlabeled M9 minimal media, the bacteria were first adapted at 37° C to increasing concentrations of D2O. (The initial H2O growth was used to prepare a 20 mL M9 culture containing 10% D2O with an OD600 of 0.2; when the OD600 reached 0.6, it was used to prepare a new culture in 50% D2O with an OD600 of 0.2. By repeating these steps, cultures containing 83% and 96% D2O were generated). The D2O adapted cells were then used to prepare a new 20 mL overnight culture in 100% D2O and used to induce a 1 L M9 culture prepared in 100% D2O, containing 1 g/L 15N-NH4Cl. For samples isotopically enriched with 13C, 4 g/L 1H-13C glucose was added to the growth medium, otherwise 8 g/L of unlabeled dextrose was employed. At an A600 of 0.8 (0.6 for 13C labeled media), the cultures were placed on ice for 30 min, adjusted to 0.4 mM IPTG, and then incubated for 36 h at 17° C with constant shaking (24 h for 13C labeled media). All growth media contained 50 mg/L of kanamycin. The cells were harvested by centrifugation at 7000 g and resuspended in lysis buffer (50 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.5, 1 M NaCl, 10% glycerol, 10 mM MgCl2 and 500 mM ATP). All subsequent steps were performed at 4°C. The cells were lysed with a French press and insoluble material was removed by centrifugation at 75000 g. The soluble lysate was then loaded on a Co+2 resin (Clontech TALON), which was washed extensively with buffer containing 50 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.5, 300 mM NaCl, 10 mM MgCl2, 500 mM ATP, 5 mM imidazole. The bound recombinant His10Smt3-ChVLig was eluted with buffer containing 300 mM imidazole and then dialyzed against 20 mM Tris-HCl, pH 8.5, 350 mM NaCl, 1 mM β-mercaptoethanol in the presence of the Smt3-specific protease Ulp1 (at a Ulp1: His10Smt3-ChVLig ratio of 1:500). The dialysate containing tag-less ChVLig and the cleaved His10Smt3 tag was subjected to a second round of Co+2- affinity chromatography, in which ChVLig was recovered in the flow-through fraction. ChVLig-AMP was purified further by gel filtration through a HiPrep 16/60 Sepacryl S-100 column (GE Healthcare), equilibrated with 20 mM MES buffer (pH 6.5), 300 mM NaCl, 150 mM NaCl, 2mM DTT, 500 mM EDTA. The protein was concentrated and the buffer composition modified as needed by centrifugal ultrafiltration using Amicon Ultra −4 or −15 (10 k) devices.

Assignment of NMR resonances

The assignment of a His-tagged construct of ChVLig-AMP has been described in detail elsewhere25. The available assignments were transferred to corresponding resonances of the non-tagged construct with the aid of a TROSY-HNCACB spectrum58 collected at 25° C on a Bruker 900 MHz instrument equipped with a cryogenic triple resonance gradient probe using a 300 mM [U 2H-13C-15N] sample contained in a 4 mm H2O-susceptibility matched tube (Shigemi Inc.) (buffer conditions: 20 mM MES, 300 mM NaCl, 1 mM EDTA, 2 mM DTT, 10% 2H2O at pH 6.5). All NMR data were processed using NMRPipe59 and processed using Sparky.

Measurement of residual dipolar couplings

Weak alignment of [U-2H-15N] ChVLig-AMP was achieved by incubating 9 mm 6 % (weight/volume) acrylamide gel with 500 mL of a 500 μM protein solution at 4° C for periods longer than two days. The gels had been pre-incubated with the buffer of choice. The buffers employed were: 20 mM MES, 2 mM DTT, 1mM EDTA, 10 % 2H2O at pH 6.5 containing either 150 mM NaCl, or 300 mM NaCl, or 150 mM NaCl and 50 mM phosphate. After washing, the gels were inserted into open-ended NMR tubes using the apparatus described by Chou et. al.60. Interleaved 15N,1H HSQC and 15N,1H TROSY experiments (1024 and 256 points acquired in the direct and indirect dimensions respectively, using 12.5 and 35 ppm for spectral windows, and employing a recycle delay of 1.5 s) were collected at 25° C on Bruker spectrometers equipped with cryogenic triple resonance gradient probes operating at 800 MHz and 900 MHz for the reference (isotropic) and partially aligned samples.

Analysis of residual dipolar couplings

The 15N,1HN RDCs were analyzed using the PALES software61. Singular value decomposition (SVD)40 was used to calculate the Saupe order tensor31 using the measured RDCs and the crystal coordinates of ChVLig-AMP in the absence (1FVI, 1P8L)18; 19 or presence of nicked dsDNA9. Amide protons were added using the program MOLMOL without any further minimization. The accuracy of the alignment tensor was evaluated using the “structural noise Monte-Carlo method” module, where noise was introduced into the atomic co-ordinates by reorienting the amide bond randomly until the noise amplitude yielded a match between the root-mean-squared deviation between experimental and calculated RDCs; followed by the SVD procedure to obtain the tensor parameters. The procedure was repeated for 1000 cycles.

The relative orientation of the NTase and OB domains of ChVLig-AMP were first determined by manual alignment of the tensor axes of the Saupe order tensors determined from the RDC data of individual domains by matching principal components of like value32. Additionally, the interdomain orientation was also determined by introducing the experimental RDCs as orientational restraints into an in vacuo 500 ps molecular dynamics (MD) simulation using the GROMACS package62. A 0.1 fs integration time was employed, electrostatic interactions were disregarded, and temperature coupling was introduced with a time constant of 0.01 ps. The system was gradually annealed from 300 to 380 K in 3 ps and then cooled back to 300 K in 220 ps. The structures of the individual domains were maintained by introduction of a large number (11,521) of interatomic distance restraints (pseudo-NOEs calculated from the crystal structure) with a force constant of 3000 kJ mol−1 nm−2, while a 350 kJ mol−1 force constant was used for the orientation restraints. Bond-lengths were constrained using the SHAKE algorithm in the usual way and the overall rotational and translational motion (of the center-of-mass) were removed prior to detailed analysis.

The possibility that the RDCs measured in solution could be explained by a two-state switching between the free-like (1FVI) and DNA bound-like (2Q2T) forms of ChVLig-AMP was tested using the following approach: the experimental RDCs and the structures observed in the free (1FVI) and DNA-bound (2Q2T) were used as inputs for a SVD calculation, from which “theoretical” RDCs for the free (1DNH,free) and DNA-bound forms (1DNH,bound) were extracted for each residue i (1 ≤ i ≤ N). Next, a population-weighted RDC (1DNH,av,i) for a given population p was defined as

| (1) |

where 0 ≤ p ≤ 1. The values of p were incremented from 0 (100 % bound-like, 2Q2T) to 1 (100 % free-like, 1FVI) in steps of 0.1 and the minimum of the following function was determined as a function of p

| (2) |

σi was the experimental error in the measured RDC value.

Salt and phosphate effects on chemical shifts

The non-specific effects of increased concentration of salt concentration and specific effects of phosphate ions in the NMR buffer on the chemical shifts of ChVLig-AMP were evaluated on 200 μM [U 2H-15N] protein samples in 20 mM MES (pH 6.5), 2 mM DTT, 1 mM EDTA containing NaCl or phosphate as follows: Series A – effects of salt concentration: 150 mM NaCl, 300 mM NaCl and 500 mM NaCl. Series B – effects of phosphate: all buffers contained 150 mM NaCl and were supplemented with 0.05, 0.15, 0.5, 1, 2, 5 10, 15, 30, 45 or 50 mM sodium phosphate. Chemical shift changes were monitored by 15N, 1H TROSY experiments at 25° C on a 600 MHz Varian Inova equipped with a cryogenic triple resonance gradient probe. A scaled chemical shift perturbation was defined as

| (3) |

where ΔωH,N were the chemical shifts changes in the proton and nitrogen dimensions upon addition of salts.

Relaxation experiments

All datasets were collected at 25° C on 300 μM [U 2H-15N] ChVLig-AMP samples in NMR buffer (see above) containing 150 mM NaCl or 300 mM NaCl; or 150 mM NaCl and 50 mM phosphate, on Bruker spectrometers operating at 600 MHz and 800 MHz, and on a Varian Inova spectrometer operating at 600 MHz. All instruments were equipped with triple-resonance cryogenic probes capable of applying pulsed field gradients along the z-axis.

The R1 and R2 relaxation data were collected in an interleaved fashion utilizing TROSY-based pulse sequences48 using the following delays: 0.05, 0.1 (×2), 0.3, 0.6, 0.9, 1.5 and 2.0 seconds (R1, 800), 0.02, 0.1 (x2), 0.3, 0,6, 0,9, 1.5, 2.0 seconds (R1, 600), 0, 0.01632 (×2), 0.03264, 0.04896 and 0.06528 seconds (R2, 800) and 0, 0.01 (x2), 0.03, 0.05 (x2), 0.07, 0.09 (R2, 600). Steady state {1H}-15N NOEs were measured by recording two interleaved spectra with a without proton saturation of 4.5 s period (6.5 s for the overall recycling delay) using a TROSY-based pulse sequence49. For all the experiments 1024 × 256 points were acquired in the direct and indirect dimension, respectively, while 12.5 × 35 ppm spectral windows were employed. Recycle delays of 1.5 s were used for the R1 and R2 data.

Relaxation data analysis

The relaxation rates were fitted to a single exponential function by introducing the peak intensities obtained by Sparky into the CURVEFIT fitting program (Dr. Arthur G. Palmer, III, Columbia University). The routine “sparky2rate” (Dr. J. Patrick Loria, Yale University) was used for data conversion. Further relaxation analyses were carried out only on peaks that could be fitted individually (peaks defined by a single unambiguously defined maximum) under all buffer conditions.

The error on the steady state {1H}-15N NOE data was calculated using the following equation:

| (4) |

where Isat and Iunsat represent the peak intensities measured in the presence and absence of proton saturation, respectively.

Estimates of the protein rotational correlation times were obtained using the program DIFTENS2.030. Reduced spectral density functions were determined using in-house programs using the following equations

| (5) |

and the modified relaxation rates are given by

| (6) |

with ; . All other symbols have their usual meaning30.

Normal modes analysis

For normal modes analysis, all the amino acids belonging to the fragment encompassing residues 203-232 were edited out from the 1FVI PDB file. The resulting structure was submitted to the Web interface elNémo (www.igs.cnrs-mrs.fr/elnemo)46, which computes elastic network modes using Cα coordinates and a cutoff of 8 Å. Minimum (DQMIN) and maximum (DQMAX) perturbations of −100 and 100 respectively, were used with a step-size (DQSTEP) of 20. Vector field diagrams describing fluctuations for the individual modes were generated using PyMOL (www.pymol.org).

Calculation of hydrodynamic properties

The expected correlation time for the individual domains was estimated using the bead model implementation of the HYDRONMR program51. The effective radius of the atomic elements was set to 3.2 Å. The minibead solvent shell radius was calculated automatically by the software, the temperature was set to 298.15 K and the viscosity to 9.11 centipoise. For the NTase domain the coordinates from the ChVLig-AMP structure (1FVI) were used as input the program. For the OB domain, 51 snapshots extracted at uniform intervals from the MD calculation described above were used instead. During the MD calculation the overall structure of the OB domain was maintained, as described above, only the latch was free (203-233) to fluctuate and sample different orientations. Each of 51 snapshots was used as input for individual HYDRONMR calculations.

Assay of Ligase Activity

Reaction mixtures (10 μl) containing 50 mM Tris (pH 7.5), 5 mM DTT, 10 mM MgCl2, 1 mM ATP, 0.5 pmol of a singly nicked 36-bp DNA substrate 5′ 32P-labeled at the nick, 1 ng of ChVLig, and 0, 50, 100, 150, or 200 mM NaCl, Na2SO4 or Na2HPO4 were incubated at 22°C for 10 min. The radiolabeled 18-mer substrate strand and the 36-mer ligation product were resolved by electrophoresis through an 18% polyacrylamide gel containing 7 M urea. The extents of product formation were quantified by scanning the gel with a Fujix BAS2500 imager and plotted as a function of anion concentration.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

We thank Drs. Hsin Wang (CCNY) and Kaushik Dutta (NSYBC) for technical support. This work has been supported by the following grants: NIH GM084278 (RG) and NSF DBI 0619224 (RG, for the 600 MHz cryogenic probe at CCNY); NIH GM63611 (SS); NIH 5G12 RR03060 (partial support of the core facilities at CCNY) and NIH P41 GM66354 (partial support of NMR facilities at NYSBC). SS is an American Cancer Society Research Professor.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Tomkinson AE, Vijayakumar S, Pascal JM, Ellenberger T. DNA ligases: structure, reaction mechanism, and function. Chem. Rev. 2006;106:687–99. doi: 10.1021/cr040498d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ellenberger T, Tomkinson AE. Eukaryotic DNA ligases: structural and functional insights. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 2008;77:313–38. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.77.061306.123941. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Shuman S. DNA ligases: Progress and prospects. J. Biol. Chem. 2009;284:17365–17369. doi: 10.1074/jbc.R900017200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Brotz-Oesterhelt H, Knezevic I, Bartel S, Lampe T, Warnecke-Eberz U, Ziegelbauer K, Habich D, Labischinski H. Specific and potent inhibition of NAD+-dependent DNA ligase by pyridochromanones. J. Biol. Chem. 2003;278:39435–42. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M306479200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chen X, Zhong S, Zhu X, Dziegielewska B, Ellenberger T, Wilson GM, MacKerell AD, Jr., Tomkinson AE. Rational design of human DNA ligase inhibitors that target cellular DNA replication and repair. Cancer Res. 2008;68:3169–77. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-6636. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Shuman S, Lima CD. The polynucleotide ligase and RNA capping enzyme superfamily of covalent nucleotidyltransferases. Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol. 2004;14:757–64. doi: 10.1016/j.sbi.2004.10.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sekiguchi J, Shuman S. Domain structure of vaccinia DNA ligase. Nucleic Acids Res. 1997;25:727–34. doi: 10.1093/nar/25.4.727. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ho CK, Van Etten JL, Shuman S. Characterization of an ATP-dependent DNA ligase encoded by Chlorella virus PBCV-1. J. Virol. 1997;71:1931–7. doi: 10.1128/jvi.71.3.1931-1937.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Nair PA, Nandakumar J, Smith P, Odell M, Lima CD, Shuman S. Structural Basis for Nick Recognition by a Minimal Pluripotent DNA Ligase. Nature Struct. Biol. 2007;14:770–778. doi: 10.1038/nsmb1266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Akey D, Martins A, Aniukwu J, Glickman MS, Shuman S, Berger JM. Crystal structure and nonhomologous end-joining function of the ligase component of Mycobacterium DNA ligase D. J. Biol. Chem. 2006;281:13412–23. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M513550200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cotner-Gohara E, Kim IK, Tomkinson AE, Ellenberger T. Two DNA-binding and nick recognition modules in human DNA ligase III. J. Biol. Chem. 2008;283:10764–72. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M708175200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gajiwala KS, Pinko C. Structural rearrangement accompanying NAD+ synthesis within a bacterial DNA ligase crystal. Structure. 2004;12:1449–59. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2004.05.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kim do J, Kim O, Kim HW, Kim HS, Lee SJ, Suh SW. ATP-dependent DNA ligase from Archaeoglobus fulgidus displays a tightly closed conformation. Acta Crystallogr. Sect. F Struct. Biol. Cryst. Commun. 2009;65:544–50. doi: 10.1107/S1744309109017485. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lee JY, Chang C, Song HK, Moon J, Yang JK, Kim HK, Kwon ST, Suh SW. Crystal structure of NAD(+)-dependent DNA ligase: modular architecture and functional implications. EMBO J. 2000;19:1119–29. doi: 10.1093/emboj/19.5.1119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Nandakumar J, Nair PA, Shuman S. Last stop on the road to repair: structure of E. coli DNA ligase bound to nicked DNA-adenylate. Mol. Cell. 2007;26:257–71. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2007.02.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Nandakumar J, Shuman S, Lima CD. RNA ligase structures reveal the basis for RNA specificity and conformational changes that drive ligation forward. Cell. 2006;127:71–84. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.08.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Nishida H, Kiyonari S, Ishino Y, Morikawa K. The closed structure of an archaeal DNA ligase from Pyrococcus furiosus. J. Mol. Biol. 2006;360:956–67. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2006.05.062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Odell M, Malinina L, Sriskanda V, Teplova M, Shuman S. Analysis of the DNA joining repertoire of Chlorella virus DNA ligase and a new crystal structure of the ligase-adenylate intermediate. Nucleic Acids Res. 2003;31:5090–100. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkg665. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Odell M, Sriskanda V, Shuman S, Nikolov DB. Crystal structure of eukaryotic DNA ligase-adenylate illuminates the mechanism of nick sensing and strand joining. Mol. Cell. 2000;6:1183–93. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(00)00115-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Pascal JM, O’Brien PJ, Tomkinson AE, Ellenberger T. Human DNA ligase I completely encircles and partially unwinds nicked DNA. Nature. 2004;432:473–8. doi: 10.1038/nature03082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Pascal JM, Tsodikov OV, Hura GL, Song W, Cotner EA, Classen S, Tomkinson AE, Tainer JA, Ellenberger T. A flexible interface between DNA ligase and PCNA supports conformational switching and efficient ligation of DNA. Mol Cell. 2006;24:279–91. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2006.08.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Singleton MR, Hakansson K, Timson DJ, Wigley DB. Structure of the adenylation domain of an NAD+-dependent DNA ligase. Structure. 1999;7:35–42. doi: 10.1016/s0969-2126(99)80007-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Subramanya HS, Doherty AJ, Ashford SR, Wigley DB. Crystal structure of an ATP-dependent DNA ligase from bacteriophage T7. Cell. 1996;85:607–15. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81260-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hakansson K, Wigley DB. Structure of a complex between a cap analogue and mRNA guanylyl transferase demonstrates the structural chemistry of RNA capping. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1998;95:1505–10. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.4.1505. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Piserchio A, Nair PA, Shuman S, Ghose R. Sequence-specific 1HN, 13C and 15N backbone resonance assignments of the 34 kDa Paramecium bursaria Chlorella virus 1 (PBCV1) DNA ligase. Biomol. NMR Assign. 2009;3:77–80. doi: 10.1007/s12104-009-9145-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Tollinger M, Skrynnikov NR, Mulder FA, Forman-Kay JD, Kay LE. Slow dynamics in folded and unfolded states of an SH3 domain. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2001;123:11341–52. doi: 10.1021/ja011300z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Farrow NA, Zhang O, Forman-Kay JD, Kay LE. A heteronuclear correlation experiment for simultaneous determination of 15N longitudinal decay and chemical exchange rates of systems in slow equilibrium. J. Biomol. NMR. 1994;4:727–34. doi: 10.1007/BF00404280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sugase K, Dyson HJ, Wright PE. Mechanism of coupled folding and binding of an intrinsically disordered protein. Nature. 2007;447:1021–5. doi: 10.1038/nature05858. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Fushman D, Xu R, Cowburn D. Direct determination of changes of interdomain orientation on ligation: use of the orientational dependence of 15N NMR relaxation in Abl SH(32) Biochemistry. 1999;38:10225–30. doi: 10.1021/bi990897g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ghose R, Fushman D, Cowburn D. Determination of the rotational diffusion tensor of macromolecules in solution from NMR relaxation data with a combination of exact and approximate methods - application to the determination of interdomain orientation in multidomain proteins. J. Magn. Reson. 2001;149:204–217. doi: 10.1006/jmre.2001.2295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Prestegard JH, Bougault CM, Kishore AI. Residual dipolar couplings in structure determination of biomolecules. Chem. Rev. 2004;104:3519–40. doi: 10.1021/cr030419i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Fischer MWF, Losonczi JA, Weaver LJ, Prestegard JH. Domain orientation and dynamics in multidomain proteins from residual dipolar couplings. Biochemistry. 1999;38:9013–22. doi: 10.1021/bi9905213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Skrynnikov N, Goto N, Yang D, Choy W, Tolman J, Mueller G, Kay L. Orienting domains in proteins using dipolar couplings measured by liquid-state NMR: differences in solution and crystal forms of maltodextrin binding protein loaded with beta-cyclodextrin. J. Mol. Biol. 2000;295:1265–73. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1999.3430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Tjandra N, Bax A. Direct measurement of distances and angles in biomolecules by NMR in a dilute liquid crystalline medium. Science. 1997;278:1111–4. doi: 10.1126/science.278.5340.1111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ruckert M, Otting G. Alignment of biological macromolecules in novel nonionic liquid crystalline media for NMR experiments. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2000;122:7793–7797. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Zweckstetter M, Bax A. Characterization of molecular alignment in aqueous suspensions of Pf1 bacteriophage. J. Biomol. NMR. 2001;20:365–77. doi: 10.1023/a:1011263920003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Tycko R, Blanco FJ, Ishii Y. Alignment of biopolymers in strained gels: a new way to create detectable dipole-dipole couplings in high-resolution biomolecular NMR. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2000;122:9340–9341. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kontaxis G, Clore GM, Bax A. Evaluation of cross-correlation effects and measurement of one-bond couplings in proteins with short transverse relaxation times. J. Magn. Reson. 2000;143:184–96. doi: 10.1006/jmre.1999.1979. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ottiger M, Delaglio F, Bax A. Measurement of J and dipolar couplings from simplified two-dimensional NMR spectra. J. Magn. Reson. 1998;131:373–8. doi: 10.1006/jmre.1998.1361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Losonczi JA, Andrec M, Fischer MW, Prestegard JH. Order matrix analysis of residual dipolar couplings using singular value decomposition. J. Magn. Reson. 1999;138:334–42. doi: 10.1006/jmre.1999.1754. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Sass J, Cordier F, Hoffmann A, Rogowski M, Cousin A, Omichinski JG, Löwen H, Grzesiek S. Purple membrane induced alignment of biological macromolecules in the magnetic field. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1999;121:2047–55. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Tolman JR, Al-Hashimi HM, Kay LE, Prestegard JH. Structural and dynamic analysis of residual dipolar coupling data for proteins. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2001;123:1416–24. doi: 10.1021/ja002500y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Getz MM, Andrews AJ, Fierke CA, Al-Hashimi HM. Structural plasticity and Mg2+ binding properties of RNase P P4 from combined analysis of NMR residual dipolar couplings and motionally decoupled spin relaxation. RNA. 2007;13:251–66. doi: 10.1261/rna.264207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Deschamps M, Campbell ID, Boyd J. Residual dipolar couplings and some specific models for motional averaging. J. Magn. Reson. 2005;172:118–32. doi: 10.1016/j.jmr.2004.09.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Henzler-Wildman K, Kern D. Dynamic personalities of proteins. Nature. 2007;450:964–72. doi: 10.1038/nature06522. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]