Abstract

During DNA synthesis, most DNA polymerases and reverse transcriptases select against ribonucleotides via a steric clash between the ribose 2′-hydroxyl group and the bulky side chain of an active site residue. Here, we demonstrated that human DNA polymerase λ used a novel sugar selection mechanism to discriminate against ribonucleotides, whereby the ribose 2′-hydroxyl group was excluded mostly by a backbone segment and slightly by the side chain of Y505. Such a steric clash was further demonstrated to be dependent on the size and orientation of the substituent covalently attached at the ribonucleotide C2′ position.

Keywords: DNA polymerase λ, sugar selection, pre-steady state kinetics, nucleotide analogs, steric gate

INTRODUCTION

DNA polymerases are classified into one of six families: A, B, C, D, X, or Y. In addition, the closely-related reverse transcriptases (RT), which catalyze DNA synthesis using both DNA and RNA templates, comprise a distinct family: the RT family. Most DNA polymerases and RTs are endowed with a stringent nucleotide recognition mechanism which prevents the aberrant incorporation of ribonucleotides (rNTP), the building block of RNA. Sugar specificity at the 2′ position occurs through a steric exclusion model, whereby a bulky side chain residue clashes with the 2′-hydroxyl of an incoming ribonucleotide. Depending upon the polymerase family, this residue has been identified as a Glu for the A-family1 and a Tyr/Phe for the B-, Y- and/or RT-families.2; 3; 4; 5; 6; 7 A wide range of discrimination factors have been measured using kinetic methodologies. Most polymerases and RTs exhibit sugar selectivity greater than 1000-fold.1; 3; 4; 5; 6 However, two X-family members, DNA polymerase μ (Polμ) and terminal deoxynucleotidyltransferase (TdT), select deoxyribonucleotides (dNTPs) over ribonucleotides by a maximum of 11-fold.8; 9; 10 Interestingly, both of these enzymes possess a Gly (Figure 1A) at the predicted ‘steric gate’ position, thereby providing a structural basis for their relaxed sugar specificities. In contrast, DNA polymerase λ (Polλ) and DNA polymerase β (Polβ), both of which belong to the X-family, have Tyr and Phe residues at and nearby the predicted ‘steric gate’ position (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Sequence alignment of human X-family DNA polymerases and the active site of Polλ.

(A) Sequence alignment of the α-helix M in the thumb domain of each human X-family DNA polymerase. Residue numbers correspond to positions with respect to the N-terminal methionines. The black background indicates which residues are conserved among the family members and the arrow head denotes the potential “steric gate” residue. (B) A close-up view of potential steric interactions with the C2′ position of an incoming ddTTP are depicted in the active site of Polλ (PDB 1XSN). Distances are listed in the table for the Y505 side chain and peptide backbone residues Y505-G508 (purple) near the C2′ position.

Polλ, which shares 33% sequence identity with Polβ, is postulated to function in DNA repair pathways such as base excision repair (BER) and non-homologous end joining (NHEJ).11; 12; 13; 14; 15; 16; 17 The cellular concentration of ribonucleotide pools has been found to be 10- to 200-fold greater than deoxyribonucleotide pools, and the level of rNTPs remains relatively high throughout the cell cycle.18; 19 Since DNA repair occurs when dNTP pools are low (e.g. NHEJ occurs during the G1 phase20 and BER during G0-G1 checkpoint21), it would be imperative that Polλ displays high sugar selectivity in order to maintain genomic integrity. Using pre-steady state kinetic methods, protein engineering techniques, and rCTP analogs, we measured the sugar selectivity of Polλ and elucidated a novel sugar selection mechanism utilized by Polλ.

RESULTS

Ribonucleotide incorporation catalyzed by human DNA polymerase λ

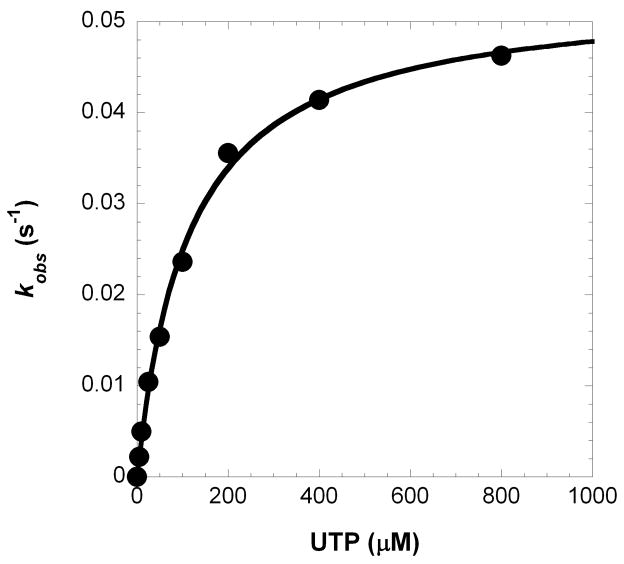

Previously, we used pre-steady state kinetic techniques to define the catalytic efficiency and fidelity of all 16 possible dNTP:dN base pair combinations catalyzed by the full-length human Polλ.22 To measure the sugar selectivity of Polλ, we employed the same kinetic methodology. The maximum rate of incorporation (kp) and the equilibrium dissociation constant (Kd) of a matched incoming ribonucleotide was measured by mixing a pre-incubated solution of Polλ and single-nucleotide gapped D-1 DNA (Figure 2A) with increasing concentrations of a ribonucleotide, UTP (see Materials and Methods). At discrete times, aliquots of this reaction mixture were quenched using EDTA and subsequently resolved using denaturing polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis. A plot of product concentration versus time (Figure 2B) was fit to a single-exponential equation (Equation 1) to extract the observed rate constant (kobs). Then, these kobs values were plotted as a function of UTP concentration (Figure 2C) and fit to a hyperbolic equation (Equation 2) which yielded a kp of 0.053 ± 0.001 s−1 and a Kd of 114 ± 8 μM (Table 1). The pre-steady state kinetic parameters were determined for the remaining, matched rNTPs and were used to calculate the catalytic efficiency, fidelity, and sugar selectivity as defined in Table 1. Polλ displayed a high sugar selectivity range (3,000 to 50,000) and a moderate fidelity (10−4 to 10−5) for all four matched rNTPs. Thus, during gap-filling DNA synthesis, the probability of Polλ inserting a matched rNTP is relatively low.

Figure 2. Concentration dependence on the pre-steady state rate constant of matched ribonucleotide incorporation.

(A) Each D-DNA substrate is composed of a 5′-radiolabeled 21-mer, a 5′-phosphorylated 19-mer, and a 41-mer template where ‘X’ represents A for D-1, C for D-8, G for D-6 and D-6T, and T for D-7. The underlined C:G base pair is A:T for D-6T. (B) A pre-incubated solution of Polλ (120 nM) and 5′-[32P]-labeled D-1 (30 nM) was rapidly mixed with increasing concentrations of UTP·Mg2+ (5 μM, ●; 10 μM, ○; 25 μM, ■; 50 μM, □; 100 μM, ▲; 200 μM, △; 400 μM, ◆ and 800 μM, ◇) for various time intervals. The solid lines are the best fits to a single-exponential equation which determined the observed rate constants, kobs. (C) The kobs values were plotted as a function of UTP concentration. The data (●) were then fit to a hyperbolic equation, yielding a kp of 0.053 ± 0.001 s−1 and a Kd of 114 ± 8 μM.

Table 1.

Kinetic parameters of matched rNTP incorporation into single-nucleotide gapped DNA catalyzed by Polλ at 37 °C.

| rNTP | DNA Template Base | kp (s−1) | Kd (μM) | kp/Kd (μM−1 s−1) | Fidelitya,b | Sugar Selectivityb,c |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| UTP | dA (D-1) | 0.053 ± 0.001 | 114 ± 8 | 4.6 × 10−4 | 3.1 × 10−4 | 3,000 |

| rCTP | dG (D-6) | 0.020 ± 0.001 | 52 ± 8 | 3.8 × 10−4 | 2.1 × 10−4 | 4,000 |

| rATP | dT (D-7) | 0.0045 ± 0.0002 | 140 ± 20 | 3.2 × 10−5 | 1.9 × 10−5 | 50,000 |

| rGTP | dC (D-8) | 0.00311 ± 0.00007 | 36 ± 3 | 8.6 × 10−5 | 1.6 × 10−5 | 14,000 |

Calculated as (kp/Kd)matched rNTP/[(kp/Kd)correct dNTP + (kp/Kd)matched rNTP].

Kinetic parameters of (kp/Kd)correct dNTP are from reference.22

Calculated as (kp/Kd)correct dNTP/(kp/Kd)matched rNTP.

We also examined the possibility of Polλ inserting a mismatched rNTP opposite a DNA template. The kinetic parameters (Supplementary Table 1) were determined for rCTP and rGTP incorporation into D-1 DNA (Figure 2A); no incorporation was observed for rATP. Surprisingly, there was only a 13- and 21-fold decrease in the catalytic efficiency of Polλ incorporating a mismatched rGTP or rCTP versus a matched UTP, therefore, the fidelity of Polλ was higher (10−5 to 10−6) for the incorporation of mismatched rNTPs over matched rNTPs. These differences in substrate specificity between matched (UTP) and mismatched rNTP incorporation originated mostly from a reduced kp (5- and 8-fold) for rCTP and rGTP, although, the binding affinity (1/Kd) was weakened slightly by 2.6-fold.

Kinetic analysis of Polλ mutants

Next, our objective was to determine the mechanistic basis of Polλ’s high sugar selectivity. Polλ possesses two bulky amino acid residues, Y505 and F506 (Figure 1A), which are in close proximity (~3–8 Å) to the C2′-position of an incoming ddTTP (Figure 1B). To determine if these side chains clash with the 2′-hydroxyl of an incoming rNTP, we created three single-point Polλ mutants: Y505G, Y505A, and F506A. Although Gly is considered a risky substitution due to its conformational flexibility, we chose this amino acid residue because the other two X-family polymerases with low sugar selectivity, i.e. Polμ and TdT, encode a Gly residue at this position (Figure 1A). First, we used circular dichroism (CD) spectroscopy to determine if the fold of these mutants was significantly different compared to wild-type Polλ (see Materials and Methods). The CD spectra were resolved and overlaid for Y505A, F506A, and wild-type Polλ (Supplementary Figure 1). The spectra indicated that these mutants were folded similar to wild-type Polλ.

Under single-turnover conditions, the kinetic parameters were measured for dTTP and UTP incorporation into D-1 DNA catalyzed by Y505G and F506A (Table 2). Since Polλ exhibited the lowest sugar selectivity with UTP, the dTTP/UTP substrate pair was chosen as the sugar selectivity probe so that fluctuations, whether it is higher or lower, in the sugar selectivity of the mutants could be measured accurately. The efficiency of dTTP incorporation catalyzed by Y505G and F506A was on par with wild-type Polλ. Interestingly, the sugar selectivity was 700 and 3,000 for Y505G and F506A, respectively. Relative to the wild-type Polλ, Y505G had 4-fold lower sugar selectivity while mutating F506A did not affect the sugar selection. The most notable kinetic change was a 3-fold rate enhancement for F506A inserting UTP, but the other kinetic parameters displayed a ~2-fold difference from wild-type Polλ. Based on the sugar selectivity values in Table 2, the side chain of F506 did not act as a steric gate while the side chain of Y505 played a role in excluding ribonucleotides by Polλ. However, the flexibility of Gly at position 505 may either allow residues near the Y505G-G508 segment to reposition so that another residue (e.g. L504 and F506) can act as a weak steric gate or increase the flexibility of the backbone segment. Therefore, we determined the kinetic parameters for dTTP and UTP incorporation into D-1 DNA catalyzed by Y505A (Table 2). This single amino acid substitution was predicted to have a minimal effect on the position and structure of the Y505A-G508 segment. The sugar selectivity for Y505A was 360 which is 9- and 2-fold less selective than wild-type Polλ and the Y505G mutant, respectively. Most notably, the binding of UTP to the Y505A·D-1 complex was 16- and 7-fold tighter than wild-type Polλ and the Y505G mutant, respectively. The UTP binding affinity difference suggested that our abovementioned concern in regards to the Y505G mutation may be problematic in assessing its role in rNTP selection. However, the tighter UTP binding did not lead to a rate enhancement of UTP incorporation catalyzed by Y505A. Collectively, these kinetic data revealed that the side chain and positioning of Y505 contribute to Polλ’s sugar selectivity, although, the reduced side chain volume of Polλ Y505G and Y505A did not relax the sugar selectivity to a similar level as Polμ and TdT.8; 9 These relatively high sugar selectivity values suggested that Polλ does not exclusively use the side chain of Y505 to discriminate against ribonucleotides. Based on the ternary crystal structure of truncated Polλ·gapped DNA·matched ddNTP23, Polλ may also utilize the backbone segment of the peptide Y505-G508 to maintain high sugar selectivity (Figure 1B). To examine this possibility, we created two Polλ deletion mutants: Y505d and Y505d-T507d. By removing these 1 or 3 amino acid residues, the objective was to create a larger space that would eliminate the steric clash between the 2′-OH of an rNTP and the side chain or backbone segment of Y505-T507 within the active site of Polλ. The Y505d mutant could not be expressed in E. coli as a soluble and active enzyme, however, a small amount of the Y505-T507d mutant was purified despite a low level of expression. Since the CD spectra in Supplementary Figure 1 suggested that the overall protein fold of Y505-T507d was similar to wild-type Polλ, we further assayed the sugar selectivity of this triple deletion mutant. A pre-incubated solution of Y505-T507d (120 nM) and 5′-radiolabeled D-8 (30 nM, Figure 2A) was reacted with either correct dGTP (64 μM) or matched rGTP (64 μM) for various times before quenching the polymerization reaction. After fitting the two time courses of product concentration to Equation 1 (Materials and Methods), the nucleotide incorporation rates were determined to be 2.0 × 10−4 s−1 (dGTP) and 2.0 × 10−5 s−1 (rGTP) (data not shown). Based on the incorporation rate ratio (kdGTP/krGTP) under the same reaction conditions, the sugar selectivity of Y505-T507d was estimated to be 10, which is much lower than 14,000 of wild-type Polλ (Table 1) and 360 of Y505A (Table 2). These results suggest that the backbone segment of Y505-G508 may function as a steric gate. However, further structural and biochemical studies are needed to validate this conclusion since the deletion of three residues caused a dramatic drop in polymerase efficiency which may either significantly attenuate the sugar selectivity or make it difficult to be measured. Based on a 12,500-fold decrease in polymerase activity, the deletion may have repositioned other residues in the helix-loop-helix segment or have caused other subtle to mild structural perturbations at the active site which could not be revealed using CD spectroscopy (Supplementary Figure 1).

Table 2.

Kinetic parameters of dTTP or UTP incorporation into single-nucleotide gapped D-1 DNA catalyzed by Polλ at 37 °C.

| Polλ Mutants | Nucleotide | kp (s−1) | Kd (μM) | kp/Kd (μM−1 s−1) | Sugar Selectivitya |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Wild type | dTTPb | 3.9 ± 0.2 | 2.6 ± 0.4 | 1.5 | |

| UTP | 0.053 ± 0.001 | 114 ± 8 | 4.6 × 10−4 | 3,000 | |

| Y505G | dTTP | 0.85 ± 0.02 | 0.81 ± 0.09 | 1.0 | |

| UTP | 0.067 ± 0.005 | 47 ± 11 | 1.4 × 10−3 | 700 | |

| Y505A | dTTP | 1.30 ± 0.03 | 1.0 ± 0.1 | 1.3 | |

| UTP | 0.0251 ± 0.0006 | 7.0 ± 0.7 | 1.4 × 10−3 | 360 | |

| F506A | dTTP | 7.1 ± 0.2 | 2.8 ± 0.4 | 2.5 | |

| UTP | 0.183 ± 0.007 | 218 ± 28 | 8.4 × 10−4 | 3,000 |

Calculated as (kp/Kd)dTTP/(kp/Kd)UTP.

Kinetic parameters were obtained from reference.22

Incorporation of rCTP-based analogs catalyzed by Polλ

To better understand the steric interactions between Polλ and an incoming ribonucleotide, we assayed wild-type Polλ in the presence of several rCTP analogs which have various chemical groups at the 2′-positions (Supplementary Figure 2). rCTP was selected due to the physiological relevance of commercially available analogs. As the size and number of functional groups at the 2′-position increased, the binding affinity (1/Kd), the incorporation rate (kp), and the substrate specificity decreased while the sugar selectivity increased. For example, the presence of one (2′-F-CTP) versus two (GemCTP) fluorine atoms increased the sugar selectivity by 6- and 23-fold, respectively. Moreover, the orientation of the 2′-hydroxyl was another important factor, since araCTP, which is a steric isomer of rCTP with a 2′-hydroxyl group directed above the ribose ring (OH↑), was incorporated 1,800-fold faster than rCTP with a 2′-OH pointing down (OH↓), and its substrate specificity was only 2-fold lower than dCTP. Polλ showed high sugar discrimination when an amine or methoxy group was at the 2′ position, for the sugar selectivity was respectively 37,000 and 1,000,000 for 2′-NH2-CTP and 2′-OCH3-CTP which is almost 10- and 250-fold greater than rCTP. These data suggested that the larger size of an amine and methoxy over a hydroxyl group created more steric hindrance during incorporation. Overall, the sugar selectivity was correlated with the size and orientation of the 2′-group: araCTP (OH↑) < 2′-F-CTP (F) < GemCTP (F2) < rCTP (OH↓) < 2′-NH2-CTP (NH2) < 2′-OCH3-CTP (OCH3).

DISCUSSION

Human DNA polymerase λ exhibited high sugar selectivity

Polλ is an enzyme proposed to participate in DNA repair pathways which may occur when cellular dNTP pools are low and rNTP pools are high. Therefore, using pre-steady state kinetic techniques, we measured the sugar selectivity of Polλ to assess the potential of Polλ aberrantly inserting an rNTP into a single-nucleotide gapped DNA substrate. These data revealed that Polλ exhibited a relatively high sugar selectivity (3,000 – 50,000), although, it depended on the base identity of the rNTP (Table 1). The order of sugar selectivity was UTP < rCTP < rGTP < rATP. In comparison to a correct dNTP, Polλ displayed a weaker binding affinity (53-fold on average) and a slower rate of incorporation (117-fold on average) with matched rNTPs (Table 1).22 Furthermore, the fidelity (10−4 to 10−5) of matched rNTP incorporation was comparable to a mismatched dNTP incorporation22, thereby suggesting the insertion of matched rNTPs would be more likely than dNTP misinsertions during DNA repair in vivo due to higher cellular concentrations of rNTPs than dNTPs. DNA repair pathways (e.g. NHEJ occurs during the G1 phase20 and BER during G0-G1 checkpoint21) proceed outside of S phase when dNTP pools are low but rNTP pools are high. In regards to mismatched rNTP incorporation into DNA, the sugar selectivity was 9- to 20-fold higher compared to matched rNTP insertion (Table 1 and Supplementary Table 1). Overall, Polλ displayed almost 460-fold less discrimination for matched versus mismatched rNTP (16-fold on average) compared to dNTP (7,100 on average) incorporations into D-1 DNA.22

For other DNA polymerase and RT families, the sugar selectivity, as measured using kinetic techniques, spans from 1 to over 1,000,000. The sugar selectivity of Polλ is similar to A-, B-, X-, and Y-family DNA polymerases such as the Klenow fragment of Escherichia coli DNA polymerase I (3,400 to 1,700,000)1, the exonuclease-deficient RB69 DNA polymerase (64,000)5, Polβ (2,000 to 6,000)8, and the DinB homolog DNA polymerase from Sulfolobus solfataricus (3,400).6 In contrast, Polμ (1 to 11)8 and TdT (3 to 9)8 have extremely low sugar selectivity values with gapped DNA. Although most DNA polymerases can incorporate rNTPs, some of them are inhibited by an RNA-terminated primer.1; 3; 9; 10 However, a previous study showed that Polλ can efficiently extend an RNA/DNA substrate, although, extension using RNA/RNA and DNA/RNA substrates was less efficient.24

Mechanism of sugar selectivity employed by Polλ

The mechanism of sugar selectivity has been examined for several DNA polymerases and reverse transcriptases. From these works, a general mechanism for nucleotide selection emerged: the 2′-hydroxyl of a rNTP clashes with a bulky side chain of an active site residue (i.e. Glu, Phe, or Tyr) which has been termed the ‘steric gate’.25 Although Polλ encodes potential ‘steric gate’ residues based on the sequence alignment analysis (Figure 1A), this enzyme displays high sugar discrimination (Table 1), and the side chains do not appear to provide a structural basis for sugar selectivity, as the backbone segment Y505-G508 is in closer proximity to C2′ (Figure 1B).23; 26 As presented herein, Polλ mutants Y505G, Y505A, and F506A maintained relatively high sugar selectivity (360 to 3,000) compared to wild-type Polλ (3,000) (Table 2). These data suggested that the side chains of Y505 and F506 respectively contributed ~9-fold and none to Polλ’s sugar selectivity. This was in stark contrast to other DNA polymerases and RTs, whereby mutating the ‘steric gate’ residues (i.e. Glu, Tyr, or Phe) to Ala or Val resulted in mutants with sugar selectivity values that were reduced from 765 to 50,000-fold based upon kinetic measurements.1; 4; 5; 6 Thus, if the Y505 side chain of Polλ served as the predominant ‘steric gate’, then the sugar selectivity of Y505A and Y505G should have been approximately 20- to 100-fold less than the measured values of 360 and 700. Therefore, other structural component(s) played a major role as the ‘steric gate’ in controlling the sugar selectivity of Polλ.

Our pre-steady state kinetic studies showed that the sugar selectivity of Polλ is 3,000 to 50,000 for a matched rNTP (Table 1) while McElhinny and Ramsden have shown that the sugar selectivity of Polβ is 2,000 to 6,000.8 Based on the ternary crystal structure of Polβ26, Pelletier et al. proposed that the backbone segment, Y271-G274, is the structural basis for this enzyme’s sugar selectivity. Their hypothesis prompted us to propose the following mechanism for the sugar selectivity of Polλ: the ribose 2′-hydroxyl clashes with both the side chain of Y505 (9-fold) and a backbone segment of the peptide Y505-G508 (360-fold). Please note, the exact contribution of the Y505 side chain and the backbone segment likely depends on the base identity of the rNTP (Table 1). To provide insight into the major ‘steric gate’ role of the Y505-G508 backbone segment, we generated a triple deletion mutant by removing the Y505-T507 tripeptide segment in order to create more space to accommodate the ribose 2′-hydroxyl group and to decrease the sugar selectivity of Polλ. Fortunately, we purified a small amount of the triple-deletion mutant. Although about 12,500-fold less active than wild-type Polλ, the triple-deletion mutant exhibited a low sugar selectivity of 10 (see Results). Thus, these kinetic data indicated that residues Y505-T507, especially Y505, were critical for catalytic activity and sugar selectivity. Interestingly, the G433Y mutant of human Polμ displays decreased polymerization activity.9 Although Polλ and Polμ respectively encode Tyr and Gly at this position, both of these residues contribute significantly to catalysis.

To illustrate how the backbone segment of Y505-G508 played the major ‘steric gate’ role, we modeled ATP into the active site of Polλ bound to a gapped DNA substrate (Figure 3). To create this model, the structure of ATP, which was bound by HIV-1 RT (PDB 2IAJ), was superimposed with the ddTTP substrate in complex with Polλ and gapped DNA (PDB 1XSN).23; 27 When a 2′-hydroxyl group was attached to a ribose in the C3′-endo conformation, there was an unfavorable steric clash between the hydroxyl and the backbone segment of Y505-G508, especially the carboxyl group of Y505 (1.88 Å). If this model is correct in solution, then Polλ employs an effective mechanism of sugar selection, whereby the backbone segment of Y505-G508 and the side chain of Y505 respectively play a major and minor role in steric exclusion of the ribose 2′-hydroxyl group. When comparing the kinetic data for the incorporation of UTP and dTTP catalyzed by Y505A (Table 2), the backbone segment contributed to the nucleotide incorporation rate and affinity by 52- and 7-fold, respectively. Thus, the steric exclusion by the backbone segment of Y505-G508 affected both the kp and Kd. In contrast, comparison of the kinetic data for UTP incorporation catalyzed by wild-type Polλ and the Y505A mutant indicated that the side chain of Y505 led to a 16-fold tighter ribonucleotide binding affinity (Table 2). Thus, the mobility of the side chain of Y505 is more dynamic than what has been extrapolated from the superimposed binary and ternary crystal structures of truncated Polλ23, especially when the side chain of Y505 is predicted to be >5 Å from the 2′-hydroxyl (Figure 3). Together, our kinetic and modeling studies indicated that Y505 of Polλ dynamically interacts with an incoming nucleotide during catalysis.

Figure 3. Model of a ribonucleotide bound at the active site of Polλ.

Using the ternary complex Polλ·gapped DNA·ddTTP (PDB 1XSN), the 2′- and 3′-hydroxyl groups were modeled onto the ribose of the ddTTP substrate. The hydroxyl groups were extracted from the ATP substrate in complex with a reverse transcriptase (PDB 2IAJ). The model presented here showed a steric clash between the 2′-hydroxyl of a dTTP analog (rTTP) and the backbone carboxyl group of Y505.

Steric hindrance confers high sugar selectivity

Since Polλ utilized a novel sugar selection mechanism, we were interested in understanding how various factors (e.g. size and stereochemistry) may influence the sugar selectivity of Polλ. These factors were examined using rCTP analogs (Supplementary Figure 2) containing different chemical moieties at ribose 2′-positions. With the exception of rCTP, 2′-NH2-CTP, and 2′-OCH3-CTP, Polλ bound tightly to these substrates, like all dNTPs22, despite the altered ribose structure. The size of the 2′-atom(s) was correlated with substrate specificity, for polymerization catalyzed by Polλ was more efficient when the substituent at the 2′-position was small (Table 3). Based on structural studies23 and our model (Figure 3), the sugar selectivity of Polλ remained low for 2′-F-CTP and GemCTP because the small hydrogen and fluorine atoms did not clash with the Y505-G508 backbone segment nor the Y505 side chain (Figure 1B). Moreover, altering the stereochemistry of the 2′-hydroxyl group dramatically relaxed the sugar selectivity of Polλ. This result supported our model which showed that there is space to accommodate the 2′-hydroxyl directed above the ribose. Additionally, a similar kinetic finding has also been observed for RB69 DNA polymerase with araCTP.5 Surprisingly, an amine group, which is slightly larger than the hydroxyl, led to a higher sugar selectivity value due to the ~190-fold slower rate of incorporation and 230-fold weaker binding affinity (Table 3). Collectively, these different rCTP analogs showed how the steric bulkiness of the ribose 2′-substituent influenced the degree of sugar selection by Polλ.

Table 3.

Kinetic parameters of rCTP analogs incorporated into single-nucleotide gapped D-6 DNA catalyzed by Polλ at 37 °C.

| rCTP Analog | kp (s−1) | Kd (μM) | kp/Kd (μM−1 s−1) | Sugar Selectivitya |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| dCTPb | 1.57 ± 0.04 | 0.9 ± 0.1 | 1.7 | |

| rCTP | 0.020 ± 0.001 | 52 ± 8 | 3.8 × 10−4 | 4,000 |

| araCTP | 1.28 ± 0.04 | 1.8 ± 0.2 | 0.71 | 2.4 |

| 2′-F-CTP | 0.83 ± 0.02 | 3.4 ± 0.3 | 0.24 | 6.3 |

| GemCTP | 0.30 ± 0.02 | 4 ± 1 | 0.075 | 23 |

| 2′-NH2-CTP | 0.0084 ± 0.0003 | 206 ± 22 | 4.1 × 10−5 | 37,000 |

| 2′-OCH3-CTP | (1.6 ± 0.1) × 10−6 | 1,000,000 |

Calculated as (kp/Kd)dCTP/(kp/Kd)CTP analog.

Kinetic parameters obtained from reference.22

In summary, Polλ can incorporate ribonucleotides, albeit with greatly reduced catalytic efficiency compared to dNTPs. More importantly, this work demonstrated that Polλ utilized primarily a backbone segment, especially the carboxyl group of Y505, and secondarily the bulky and dynamic side chain of Y505 to discriminate between dNTPs and rNTPs unlike other DNA polymerases and RTs examined to date.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Materials

These chemicals were purchased from the following companies: [γ-32P]ATP, MP Biomedicals; deoxyribonucleotide-5′-triphosphates, GE Healthcare; ribonucleotide-5′-triphosphates, MBI Fermentas; 2′-aracytidine-5′-triphosphate (araCTP), 2′-deoxy-2′,2′-difluorocytidine-5′-triphosphate (GemCTP), 2′-fluoro-2′-deoxycytidine-5′-triphosphate (2′-F-CTP), and 2′-amino-2′-deoxycytidine-5′-triphosphate (2′-NH2-CTP), and 2′-O-methylcytidine-5′-triphosphate (2′-OCH3-CTP), TriLink Biotechnologies; Biospin columns, Bio-Rad Laboratories; OptiKinase™, USB Corporation; Microcon centrifugal filter devices, Millipore; synthetic oligodeoxyribonucleotides 21-mer, 5′-phosphorylated 19-mer, and 41-mers, Integrated DNA Technologies. The structural model was completed using software created by Swiss PDB and PyMol.

Mutagenesis, expression and purification of wild-type and mutant forms of Polλ

Mutations and deletions were introduced into the pET28b-Polλ plasmid encoding full-length human DNA polymerase λ using a QuikChange XL site-directed mutagenesis kit (Stratagene). The mutated or deleted regions of the Polλ gene were confirmed via DNA sequencing (Plant-Microbe Genomics Facility at The Ohio State University). The expression and purification of wild-type Polλ and its variants was performed as previously described.22

Circular dichroism spectroscopic studies

Each Polλ variant (11.3 μM) was added to a degassed buffer (25 mM sodium phosphate at pH 7.5, 50 mM NaCl, 5 mM MgCl2, and 10% glycerol) by performing a series of buffer exchanges. The CD spectra were collected in a 1-mm path-length cuvette at 37 °C using an AVIV CD spectrometer model 62A DS (Lakewood, NJ, USA). Data points were recorded at 1-nm intervals from 270 to 200 nm. Spectra of the buffer were subtracted from the sample spectra and the molar ellipticity (degree cm2 dmol−1) was plotted as a function of wavelength.

Single-nucleotide gapped DNA substrates

Commercially-synthesized oligomers in Figure 2A were purified using polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis. The 21-mer primer was radiolabeled with [γ-32P]ATP and OptiKinase™ as previously described.22; 28 The single-nucleotide gapped DNA substrates were prepared by mixing the 5′-[32P]-radiolabeled 21-mer, the appropriate non-radiolabeled downstream strand 19-mer, and the appropriate 41-mer template at a 1:1.25:1.15 molar ratio, respectively. Then, the annealing mixture was denatured at 95 °C for 6 minutes and slowly cooled to room temperature over several hours.

Measurement of the kp and Kd for single nucleotide incorporation

Kinetic assays were completed using optimized buffer L (50 mM Tris-Cl, pH 8.4 at 37 °C, 5 mM MgCl2, 100 mM NaCl, 0.1 mM EDTA, 5 mM DTT, 10% glycerol, and 0.1 mg/ml BSA) as previously described.28 All kinetic experiments described herein were performed at 37 °C and the reported concentrations were final after mixing all the components. A pre-incubated solution containing wild-type Polλ (120 nM) or a Polλ mutant (300 nM) and a single-nucleotide gapped DNA substrate (30 nM) was mixed with increasing concentrations (0.25–1000 μM) of nucleotide in buffer L at 37 °C. Aliquots of the reaction mixtures were quenched at various times using 0.37 M EDTA. A rapid chemical-quench flow apparatus (KinTek) was utilized for fast nucleotide incorporations. Reaction products were resolved using sequencing gel electrophoresis (17% acrylamide, 8 M urea) and quantitated with a Typhoon TRIO (GE Healthcare). The time course of product formation at each nucleotide concentration was fit to a single-exponential equation (Equation 1) using a nonlinear regression program KaleidaGraph (Synergy Software) to yield an observed rate constant of nucleotide incorporation (kobs). The kobs values were then plotted as a function of nucleotide concentration and fit using the hyperbolic equation (Equation 2) which resolved the kp and Kd values for nucleotide incorporation catalyzed by wild-type Polλ or a mutant. When nucleotide binding was too weak to reach saturation, the plot of kobs versus nucleotide concentration was fit to equation 3 which extracted the substrate specificity constant, kp/Kd.

| Equation 1 |

| Equation 2 |

| Equation 3 |

Supplementary Material

Abbreviations

- 2′-F-CTP

2′-fluoro-2′-deoxycytidine-5′-triphosphate

- 2′-NH2-CTP

2′-amino-2′-deoxycytidine-5′-triphosphate

- 2′-OCH3-CTP

2′-O-methylcytidine-5′-triphosphate

- araCTP

2′-aracytidine-5′-triphosphate

- BER

base excision repair

- CD

circular dichroism

- ddNTP

2′,3′-dideoxyribonucleotide-5′-triphosphate

- dNTP

deoxyribonucleotide-5′-triphosphate

- FDA

Food and Drug Administration

- GemCTP

2′-deoxy-2′,2′-difluorocytidine-5′-triphosphate

- HIV-1

human immunodeficiency virus type I

- NHEJ

non-homologous end joining

- Polβ

DNA polymerase β

- Polλ

DNA polymerase λ

- Polμ

DNA polymerase μ

- rNTP

ribonucleotide-5′-triphosphate

- RT

reverse transcriptase

- TdT

terminal deoxynucleotidyltransferase

Footnotes

This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health Grant GM079403 to Z.S. J.A.B. was supported by an American Heart Association Pre-doctoral Fellowship (Grant 0815382D) and an International P.E.O. Scholar Award. K.A.F. was supported by the American Heart Association Pre-doctoral Fellowship (Grant 0415129B) and the Presidential Fellowship from The Ohio State University. J.D.F. was supported by an American Heart Association Pre-doctoral Fellowship (Grant 0615091B). S.M.S. was supported by the National Institutes of Health Chemistry and Biology Interface Program at The Ohio State University (Grant T32-GM008512-13). S.A.N. was supported by an REU supplemental grant from the National Science Foundation Career Award to Z.S. (Grant MCB-0447899).

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Astatke M, Ng K, Grindley ND, Joyce CM. A single side chain prevents Escherichia coli DNA polymerase I (Klenow fragment) from incorporating ribonucleotides. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1998;95:3402–7. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.7.3402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gardner AF, Jack WE. Determinants of nucleotide sugar recognition in an archaeon DNA polymerase. Nucleic Acids Res. 1999;27:2545–53. doi: 10.1093/nar/27.12.2545. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bonnin A, Lazaro JM, Blanco L, Salas M. A single tyrosine prevents insertion of ribonucleotides in the eukaryotic-type phi29 DNA polymerase. J Mol Biol. 1999;290:241–51. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1999.2900. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cases-Gonzalez CE, Gutierrez-Rivas M, Menendez-Arias L. Coupling ribose selection to fidelity of DNA synthesis. The role of Tyr-115 of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 reverse transcriptase. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:19759–67. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M910361199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Yang G, Franklin M, Li J, Lin TC, Konigsberg W. A conserved Tyr residue is required for sugar selectivity in a Pol alpha DNA polymerase. Biochemistry. 2002;41:10256–61. doi: 10.1021/bi0202171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.DeLucia AM, Grindley ND, Joyce CM. An error-prone family Y DNA polymerase (DinB homolog from Sulfolobus solfataricus) uses a ‘steric gate’ residue for discrimination against ribonucleotides. Nucleic Acids Res. 2003;31:4129–37. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkg417. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gao G, Orlova M, Georgiadis MM, Hendrickson WA, Goff SP. Conferring RNA polymerase activity to a DNA polymerase: a single residue in reverse transcriptase controls substrate selection. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1997;94:407–11. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.2.407. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Nick McElhinny SA, Ramsden DA. Polymerase mu is a DNA-directed DNA/RNA polymerase. Mol Cell Biol. 2003;23:2309–15. doi: 10.1128/MCB.23.7.2309-2315.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ruiz JF, Juarez R, Garcia-Diaz M, Terrados G, Picher AJ, Gonzalez-Barrera S, Fernandez de Henestrosa AR, Blanco L. Lack of sugar discrimination by human Pol mu requires a single glycine residue. Nucleic Acids Res. 2003;31:4441–9. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkg637. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Boule JB, Rougeon F, Papanicolaou C. Terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase indiscriminately incorporates ribonucleotides and deoxyribonucleotides. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:31388–93. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M105272200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Garcia-Diaz M, Bebenek K, Kunkel TA, Blanco L. Identification of an intrinsic 5′-deoxyribose-5-phosphate lyase activity in human DNA polymerase lambda: a possible role in base excision repair. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:34659–63. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M106336200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Braithwaite EK, Kedar PS, Lan L, Polosina YY, Asagoshi K, Poltoratsky VP, Horton JK, Miller H, Teebor GW, Yasui A, Wilson SH. DNA polymerase lambda protects mouse fibroblasts against oxidative DNA damage and is recruited to sites of DNA damage/repair. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:31641–7. doi: 10.1074/jbc.C500256200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Braithwaite EK, Prasad R, Shock DD, Hou EW, Beard WA, Wilson SH. DNA polymerase lambda mediates a back-up base excision repair activity in extracts of mouse embryonic fibroblasts. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:18469–75. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M411864200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fan W, Wu X. DNA polymerase lambda can elongate on DNA substrates mimicking non-homologous end joining and interact with XRCC4-ligase IV complex. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2004;323:1328–33. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2004.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lee JW, Blanco L, Zhou T, Garcia-Diaz M, Bebenek K, Kunkel TA, Wang Z, Povirk LF. Implication of DNA polymerase lambda in alignment-based gap filling for nonhomologous DNA end joining in human nuclear extracts. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:805–11. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M307913200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Capp JP, Boudsocq F, Bertrand P, Laroche-Clary A, Pourquier P, Lopez BS, Cazaux C, Hoffmann JS, Canitrot Y. The DNA polymerase lambda is required for the repair of non-compatible DNA double strand breaks by NHEJ in mammalian cells. Nucleic Acids Res. 2006;34:2998–3007. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkl380. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ma Y, Lu H, Tippin B, Goodman MF, Shimazaki N, Koiwai O, Hsieh CL, Schwarz K, Lieber MR. A biochemically defined system for mammalian nonhomologous DNA end joining. Mol Cell. 2004;16:701–13. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2004.11.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Traut TW. Physiological concentrations of purines and pyrimidines. Mol Cell Biochem. 1994;140:1–22. doi: 10.1007/BF00928361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kornberg A, Baker TA. DNA replication. 2. W.H. Freeman; New York: 1992. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Branzei D, Foiani M. Regulation of DNA repair throughout the cell cycle. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2008;9:297–308. doi: 10.1038/nrm2351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Offer H, Zurer I, Banfalvi G, Reha’k M, Falcovitz A, Milyavsky M, Goldfinger N, Rotter V. p53 modulates base excision repair activity in a cell cycle-specific manner after genotoxic stress. Cancer Res. 2001;61:88–96. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Fiala KA, Duym WW, Zhang J, Suo Z. Up-regulation of the fidelity of human DNA polymerase lambda by its non-enzymatic proline-rich domain. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:19038–44. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M601178200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Garcia-Diaz M, Bebenek K, Krahn JM, Kunkel TA, Pedersen LC. A closed conformation for the Pol lambda catalytic cycle. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2005;12:97–98. doi: 10.1038/nsmb876. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ramadan K, Maga G, Shevelev IV, Villani G, Blanco L, Hubscher U. Human DNA polymerase lambda possesses terminal deoxyribonucleotidyl transferase activity and can elongate RNA primers: implications for novel functions. J Mol Biol. 2003;328:63–72. doi: 10.1016/s0022-2836(03)00265-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Joyce CM. Choosing the right sugar: how polymerases select a nucleotide substrate. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1997;94:1619–22. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.5.1619. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Pelletier H, Sawaya MR, Kumar A, Wilson SH, Kraut J. Structures of ternary complexes of rat DNA polymerase beta, a DNA template-primer, and ddCTP. Science. 1994;264:1891–903. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Das K, Sarafianos SG, Clark AD, Jr, Boyer PL, Hughes SH, Arnold E. Crystal structures of clinically relevant Lys103Asn/Tyr181Cys double mutant HIV-1 reverse transcriptase in complexes with ATP and non-nucleoside inhibitor HBY 097. J Mol Biol. 2007;365:77–89. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2006.08.097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Fiala KA, Abdel-Gawad W, Suo Z. Pre-steady-state kinetic studies of the fidelity and mechanism of polymerization catalyzed by truncated human DNA polymerase lambda. Biochemistry. 2004;43:6751–62. doi: 10.1021/bi049975c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.