Abstract

Objective:

To assess the message preferences of individuals affected by depression as part of a project that will evaluate interventions to encourage at-risk patients to talk to their physicians about depression.

Methods:

Adaptive Conjoint Analysis (ACA) of 32 messages defined by 10 message attributes. Messages were developed based on input from three focus groups comprised of individuals with a personal and/or family history of depression, then tested using volunteers from an internet health community. In an online conjoint survey, 249 respondents with depression rated their liking of the messages constructed for each attribute. They were then presented with two message sets and rated their preferences. Preference utilities were generated using hierarchical Bayes estimation.

Results:

The optimal communication approach described both psychological and physical symptoms of depression, recognized multiple treatment options, offered lifetime prevalence data, noted that depression can affect anyone, and acknowledged that finding an effective treatment can take time.

Conclusion:

Individuals with depression respond differently to depression care messages, underscoring the need for careful message development and evaluation.

Practice Implications:

ACA, used in conjunction with focus groups, is a promising approach for developing and testing messages in the formative research stage of intervention development.

Keywords: focus groups, adaptive conjoint analysis, depression, communication, messages, care-seeking, help-seeking

1. Introduction

Major depression is both common and undertreated [1-6]. Many individuals with depression do not seek care because they do not recognize their symptoms as signs of depression [7]. Others realize that they are depressed but resist seeking care due to stigma and other concerns [8]. This is unfortunate because depression can usually be treated effectively [9-12]. Several strategies have been employed to encourage care-seeking. Education campaigns targeting the public and physicians, for example, can increase awareness of depression [13-16], promote help-seeking [17, 18], reduce stigma [19], and lower suicide rates [20, 21].

Our objective is to develop and test two interventions that will be implemented in office practice. The first will consist of videos shown in primary care physicians' offices that are targeted on the basis of patient characteristics. The second will use computer kiosks to generate a tailored persuasive message encouraging care-seeking for each patient based on unique personal information. As many as 20% of primary care patients present with symptoms of depression [22], and a plurality of patients with common mental health conditions are treated exclusively in primary care settings [23-24]. Activating individuals during their office visits allows their situation to be addressed immediately by their personal physician.

This paper reports the results of mixed methods formative research that tests messages that could be incorporated into these interventions. We had two primary objectives. First, we sought to identify through focus groups key ideas that need to be incorporated into any intervention that strives to motivate care-seeking among individuals with depression. Second, we tested specific messages that could be used to convey these key ideas using Adaptive Conjoint Analysis (ACA). Conjoint analysis is an established method in market research for measuring consumer preferences for different variations of products and services [25]. These variations are defined by a set of attributes, each having two or more variations. These variations are referred to as the attribute's levels. To use a healthcare example, patients' preferences for medications are presumably shaped by such attributes as cost, side effects, and effectiveness that could each be described in a myriad of ways. Conjoint analysis has gained popularity in health services research in recent years [26, 27]. For example, it has been used to study patient preferences for congestive heart failure therapy [28], adherence to highly active antiretroviral therapy for HIV [29], and willingness to accept daily subcutaneous injections for osteoporosis [30]. In the context of depression care, Dwight-Johnson and colleagues used conjoint analysis to assess factors that influence the depression treatment preferences of low SES Latino patients [31]. No prior studies have used conjoint analysis for the specific task of testing messages concerning depression or any other medical issue. As such, this article serves as a demonstration of the use of conjoint analysis for message creation in intervention development.

2. Methods

All study procedures for the focus groups were approved by the IRBs at the University of California, Davis; University of Rochester; and the University of Texas at Austin. Conjoint survey procedures were approved by the IRB at UC Davis. The research was carried out in four steps that will be discussed in turn.

2.1. Step 1: Identification of message attributes through focus groups

Attribute identification was based primarily on three focus groups conducted in June 2008, one at each of three sites: Sacramento, California; Rochester, New York; and Austin, Texas. The three groups of participants came from a purposefully selected subset of participants from 15 earlier focus groups, 5 at each site. Interested participants responded to online postings at craigslist.com, county clinic and physician office flyers, and neighborhood zip code targeting strategies to ensure race/ethnicity and income diversity. Participants (n=116) responding to our recruiting efforts who were 25-64 years of age, had a self-reported personal and/or family history of depression, and who spoke and understood English were assigned by gender to a neighborhood-specific income group (low- versus mid-income). The low income group consisted of individuals at the 15th percentile or less for their community and the mid-income group was composed of individuals near the 50th percentile. Each focus group discussion was guided by a set of questions about participants' depression and symptom history, how they came to recognize depression and its symptoms, and what factors would prompt them to talk with others, including their primary care provider, about depression. All participants were asked to describe the messages that did or possibly could prompt them to discuss depression with their doctor.

Group participants provided informed consent prior to participation, received a $35 stipend for their time, and completed a questionnaire consisting of demographic and health variables. To facilitate discussions, participants were shown public service announcements used in past depression awareness public information campaigns, as well as print and television direct-to-consumer advertisements for depression. Groups explored what they liked and disliked about these messages and considered what might work in future videos created to encourage patients with depression symptoms to talk with their doctors. They also discussed barriers that might prevent a person from seeking help. Relevant themes for coding were identified based on review of discussion transcripts, summaries of recurrent data, and consensus by discussion in multidisciplinary team meetings.

Ten recurring themes (referred hereafter as “attributes”), numbered sequentially below, emerged from analysis of the data from the focus groups. First, participants felt that a misunderstanding of the nature of depression deters care-seeking. Two ideas pertain to this barrier: (1) misunderstanding of the symptoms of depression, which can suppress recognition of the condition; and (2) the belief that depression is rare, leading affected individuals to feel that they probably do not have it. A second set of barriers pertain to problems communicating with one's physician about depression This set is composed of 5 specific issues: (3) depression is not a real medical condition and thus should not or does not need to be shared with one's medical doctor; (4) anticipation of shame from disclosing one's symptoms to the doctor; (5) the belief that depression is self-resolving and thus does not need to be brought to the doctor's attention; (6) lack of knowledge about how to introduce the topic of depression with the doctor; and (7) the notion that depression is a private matter that should be kept to oneself. The third set of barriers, low acceptability of treatment, was reflected in these issues: (8) the belief that if one asks for help, one will just be given medication; (9) the concern that treatment would entail the use of risky medications with unpleasant side effects; and (10) doubts about the effectiveness of antidepressants.

2.2. Step 2: Development of test messages

In the second stage of our analysis, the investigators generated two to four potential messages per attribute that could be used to convey these ideas. In some instances, the focus groups offered very specific language to express the attribute. In other instances, the focus groups offered the core idea but no specific language or argument for a corresponding message. In these instances, our team drew upon its expertise to develop test messages for the attribute. Table 1 displays messages developed and tested in the conjoint survey for each of the 10 attributes.

Table 1.

Barriers to help-seeking and test messages.

| Barriers (Label) | Test Messages (Label) |

|---|---|

|

Problems of Understanding | |

| Misunderstanding of the symptoms of depression. (SYMPTOMS) |

|

| Depression is rare (so I probably don't have it). (RARE) |

|

|

Problems of Communicating With One's Physician | |

| Depression is not a real medical condition, and thus does not need to be brought to my doctor's attention. (MEDICAL) |

|

| I am shamed by my depression. (SHAME) |

|

| My depression will eventually go away on its own (and thus does not need to be treated). (PERSIST) |

|

| I don't know how to raise the issue of my depression with my doctor. (TOPIC) |

|

| My depression is a private matter and should be kept to myself. (PRIVATE) |

|

|

Problems of Treatment Acceptance | |

| If I ask for help, my doctor will just want to give me drugs. (TREATMENTS) |

|

| If I ask for help, I may be given medications that have risky side effects. (RISKS) |

|

| If I ask for help, I may be given medications that don't work. (EFFECTIVE) |

|

2.3. Step 3: Administration of the conjoint survey

Message preferences were assessed using an online conjoint survey. A convenience sample for the survey was recruited from the membership of a health-related Internet community during the Fall of 2008. The website for this community offers moderated forums organized around specific issues on which members interact anonymously. The site's medical director announced the study in her blog, described the survey, encouraged individuals 18 years or older with a history of depression to participate, and provided a link to the survey.

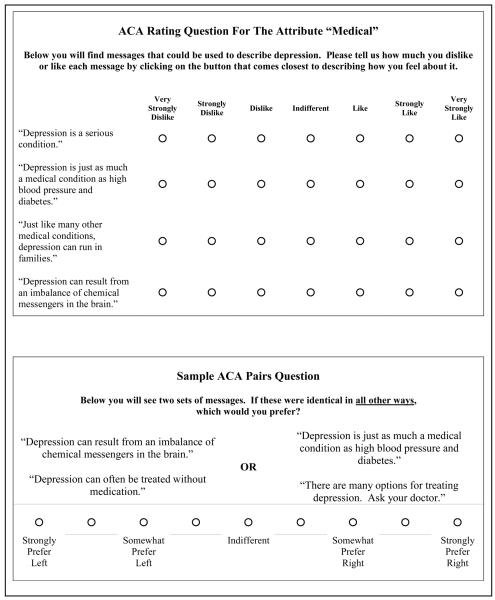

The survey, which took approximately 15 minutes to complete, was administered using Sawtooth Software's SSI Web platform and ACA module for adaptive conjoint analysis [32]. On the first page of the questionnaire, respondents were assured that their responses were confidential and given an overview of the survey. The remainder of the questionnaire was organized into three sections. In the first section, called ACA Ratings, the respondent was presented with rating scales for each level (i.e., each test message) of the 10 attributes. Examples of rating questions are shown in the upper section of Figure 1. The order of presentation of both attributes and message levels was randomized across respondents. In the second section, called ACA Pairs, the respondent was presented with 20 pair questions, an example of which is shown in the lower section of Figure 1. The pair questions presented to the respondent were generated interactively on the basis of the respondent's answers to the ACA ratings questions. These questions are sometimes called “trade off questions” because they force the respondent to decide what is most important as they consider their preference when presented with two competing sets of messages, each attractive to the respondent on at least one level of an attribute. This combined use of a priori ratings and pair questions in ACA has proven to be useful in modeling and predicting preferences, outcomes and behavior in studies of consumers and patients [33-35]. The third section of the questionnaire included standard demographic and health questions.

Fig. 1.

Sample ACA questions.

2.4. Step 4: Analysis

In total, 374 individuals completed the survey. Given our emphasis on unipolar depression in primary care, we dropped 125 individuals who did not have a history of depression or who reported a prior diagnosis of schizophrenia or manic-depressive disorder. This left us with data from 249 individuals with a past diagnosis of unipolar depression.

ACA responses were analyzed using the Sawtooth Software's ACA/HB and SMRT market simulation modules [36]. The ACA/HB module was used to generate utility estimates for each individual via hierarchical Bayes (HB) estimation. These utilities are essentially regression coefficients for each attribute level [36]. For each respondent, the sum of his or her utilities across the levels of any given attribute is 0. The utilities reflect the respondent's liking of the attribute level, relative to the other levels for the attribute. The SMRT module was used to generate attribute importance values for each respondent based on the utilities. An attribute's importance reflects the size of the difference between the highest- and lowest utility value for the levels of that attribute; importance values are scaled to sum to 100%. For example, if for any given respondent the utilities for the levels of an attribute were identical, this would indicate that the attribute did not influence the respondent's preference ratings, resulting in an attribute importance value of 0%. In contrast, an attribute having levels that differ substantially in their corresponding utilities for any given respondent is presumed to have exerted a greater influence on the respondent's preference judgments.

Each respondent's utilities and attribute importance scores were merged with their responses to the demographic and health questions into a single database that was analyzed with Stata (version 9.0). These analyses consisted primarily of basic descriptive statistics (e.g., averaged utilities and importance values across respondents). We also compared attribute importance values for respondents over varying demographic and health status groups via multivariate analysis of variance (MANOVA). Since the importance values for k attributes in a conjoint analysis sum to 100%, the dependent variables in such an analysis are k-1 attributes. Specifically, since our analyses were based on 10 attributes, MANOVA was based on the first nine attributes. This process was repeated when testing for significant differences in the utilities for the levels of each specific attribute. Thus, when asking if the utilities for a specific attribute with k levels differed by gender, income, etc., a MANOVA was carried out on the first k-1 set of utilities for that attribute. When an attribute had just two levels, ANOVA was carried out on one level to test for differences.

3. Results

3.1. Sample characteristics

Table 2 provides a profile of the conjoint survey respondents. Most participants were white women from the U.S.; more diversity was found on the dimensions of age, education, and income. Approximately one-half of the respondents were experiencing depression symptoms, as measured on the PHQ-2. More than one-third reported their health to be only fair or poor. Nearly 70% were being treated by a primary care physician and/or a psychiatrist for depression at the time of the survey, approximately two-thirds were taking antidepressants, and more than two-fifths were receiving counseling.

Table 2.

Sample characteristics.

| Respondent Characteristic | % | N |

|---|---|---|

| DEMOGRAPHICS | ||

| Female | 86.7 | 216 |

| Age | ||

| 18-29 | 18.5 | 46 |

| 30-39 | 16.1 | 40 |

| 40-49 | 34.1 | 85 |

| 50-59 | 25.7 | 64 |

| ≥60 | 5.6 | 14 |

| White Race | 94.0 | 234 |

| Culturally or Ethnically Hispanic | 4.0 | 10 |

| Education | ||

| H.S. or Less | 16.1 | 40 |

| Some College (No Degree) | 32.5 | 81 |

| Associate Degree | 18.5 | 46 |

| Bachelor Degree | 22.9 | 57 |

| Graduate Degree | 10.0 | 25 |

| Household Income | ||

| Under $20,000 | 20.5 | 51 |

| $20,001 – $40,000 | 18.1 | 45 |

| $40,001 – $60,000 | 16.9 | 42 |

| $60,001 – $80,000 | 10.8 | 27 |

| $80,001 – $100,000 | 10.8 | 27 |

| >$100,000 | 7.6 | 19 |

| Declined To Answer | 15.3 | 38 |

| Relational Status | ||

| Married | 37.8 | 94 |

| Not Married But Partnered | 7.6 | 19 |

| Separated or Divorced | 27.3 | 68 |

| Widow/Widower | 2.8 | 7 |

| Never Married | 24.5 | 61 |

| Nationality | ||

| United States | 79.1 | 197 |

| Australia | 4.0 | 10 |

| Canada | 6.8 | 17 |

| United Kingdom | 7.6 | 19 |

| Other | 2.4 | 6 |

| HEALTH SITUATION | ||

| Diagnoses | ||

| Major Depressive Disorder | 100.0 | 249 |

| Manic Depressive Disordera | 0.0 | 0 |

| Schizophreniaa | 0.0 | 0 |

| Seasonal Affective Disorder | 14.1 | 35 |

| Post Partum Depression (Women Only) | 7.9 | 17 |

| PHQ-2 Score | ||

| 0 | 10.4 | 26 |

| 1 | 4.4 | 11 |

| 2 | 28.9 | 72 |

| 3 | 11.6 | 29 |

| 4 | 16.1 | 40 |

| 5 | 7.6 | 19 |

| 6 | 20.9 | 52 |

| General Health Perception | ||

| Excellent | 4.8 | 12 |

| Very Good | 16.5 | 41 |

| Good | 40.2 | 100 |

| Fair | 32.1 | 80 |

| Poor | 6.4 | 16 |

| Treating Provider | ||

| Not Currently Under Physician's Care | 30.9 | 77 |

| Under Care Of PCP | 30.5 | 76 |

| Under Care Of Psychiatrist | 26.5 | 66 |

| Under Care of PCP and Psychiatrist | 12.0 | 30 |

| Currently Taking Antidepressant Medication | 68.3 | 170 |

| Currently Receiving Counseling for Depression | 42.6 | 106 |

Total Sample Size, N=249.

Respondents with manic depressive disorder or schizophrenia were excluded from the analysis.

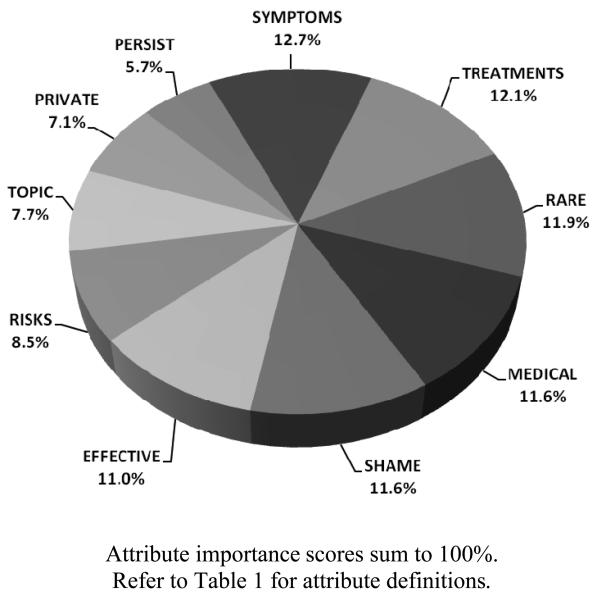

3.2. Attribute Importance

Attribute importance values are reported in Figure 2. The values across the 10 attributes sum to 100% and reflect the relative importance of each attribute on respondents' preferences. In order of importance, preferences were driven most by variations in messages addressing the signs of depression (SYMPTOMS), the range of treatments available (TREATMENTS), the prevalence of depression in the population (RARE), depression's status as a medical condition (MEDICAL), embarrassment stemming from asking for care (SHAME), and treatment effectiveness (EFFECTIVE). Preferences were influenced less by message variations for the attributes pertaining to the side effects of antidepressant medications (RISKS), approaches to raising the topic of depression with the doctor (TOPIC), the potential influence of depression one one's social network (PRIVATE), and the persistence of untreated depression (PERSIST). Using MANOVA, we considered whether the set of attribute importance values differed for any of the demographic or health variables reported in Table 2. No significant differences were identified (P<.05 criterion).

Fig. 2.

Attribute importance.

3.3. Message Preferences

Averaged utilities for the test messages are reported in Table 3. When discussing the symptoms of depression respondents strongly preferred message SYM2 (refer to Table 1 for exact wording), which describes both classical psychological and somatic symptoms of depression and includes an explicit statement that depression can affect people differently. The prevalence of depression was felt to be best conveyed with lifetime prevalence data (RARE4). The status of depression as a medical condition requiring medical treatment was best framed by comparing depression to other chronic medical conditions (MED2). Stigma was best confronted with a simple statement about depression being something that could happen to anyone (SHAM3). When addressing the belief that depression will simply go away on its own, respondents again preferred a comparison of depression with other chronic conditions (PER2). Preferences for the alternative messages for the attribute TOPIC varied very little, but the favored message for broaching the topic of depression with one's doctor was “ask your doctor if medication or therapy might help” (TOP2). A message telling individuals that their depression seriously affects both their lives and the lives of their love ones (PRI2) was the preferred approach for addressing the belief that depression should be kept to oneself. The favored message for dealing with concerns about being treated with medications was one in which depression is said to be treatable “with medication, counseling, or both” (TRE1). There was little variation in utilities for the three messages pertaining to medication side effects, but the preferred message was one that offered assurance that side effects often go away with continued use (RISK2). Doubts about medication effectiveness were best handled by stating that the treatment process is a matter of finding for each patient the right medication (EFF3), which was preferred over quantified claims of drug effectiveness.

Table 3.

Utilities sorted from most to least preferred for each attribute. Refer to Table 1 for complete message text.

| Attribute | Levels | Utilities | SE of Mean |

|---|---|---|---|

| SYMPTOMS | 2. Depression affects people differently… (SYM2) | 1.10 | .05 |

| 3. For some people, depression feels like… (SYM3) | 0.23 | .04 | |

| 1. The major…lasting at least 2 weeks. (SYM1) | −1.33 | .04 | |

| RARE | 4. Approximately 1 in 5 Americans… (RARE4) | 0.87 | .05 |

| 3. At any given time, at least 5% to 10% … (RARE3) | −0.24 | .05 | |

| 1. Depression is very common. (RARE1) | −0.27 | .07 | |

| 2. About 1 in 10 patients you see in a typical…(RARE2) | −0.36 | .05 | |

| MEDICAL | 2. Depression is just as much…diabetes. (MED2) | 0.61 | .06 |

| 4. Depression…chemical messengers in the brain. (MED4) | 0.02 | .05 | |

| 3. Just like …depression can run in families. (MED3) | −0.09 | .05 | |

| 1. Depression is a serious condition. (MED1) | −0.54 | .06 | |

| SHAME | 3. Depression can happen to anyone… (SHAM3) | 0.71 | .04 |

| 2. Having depression is not your fault. (SHAM2) | 0.00 | .05 | |

| 1. Having depression is nothing to be ashamed of. (SHAM1) | −0.28 | .05 | |

| 4. Depression treatment is between you, your family. (SHAM4) |

−0.43 | .08 | |

| PERSIST | 2. You would not expect high blood pressure… (PER2) | 0.44 | .04 |

| 1. Depression does not usually just go … (PER1) | −0.44 | .04 | |

| TOPIC | 2. If you think…ask your doctor… (TOP2) | 0.09 | .05 |

| 3. If you are not feeling… “Could I have depression?” (TOP3) | 0.01 | .05 | |

| 1. If you think you have depression, tell your doctor. (TOP1) | −0.10 | .04 | |

| PRIVATE | 2. Having depression can…lives of loved ones. (PRI2) | 0.23 | .03 |

| 3. When someone… family and friends suffer too. (PRI3) | 0.05 | .05 | |

| 1. Having depression can seriously affect your life. (PRI1) | −0.28 | .05 | |

| TREATMENTS | 1. Depression…medication, counseling, or both. (TRE1) | 0.58 | .06 |

| 2. There are many options… Ask your doctor. (TRE2) | 0.30 | .05 | |

| 3. Depression can often…without medication. (TRE3) | −0.88 | .07 | |

| RISKS | 2. Side effects…usually go away with continued use. (RISK2) |

0.19 | .04 |

| 3. The newer antidepressants have fewer side effects. (RISK3) |

−0.06 | .06 | |

| 1. All medications can have…generally well tolerated. (RISK1) |

−0.13 | .05 | |

| EFFECT | 3. Finding the right antidepressant can take time… (EFF3) | 0.89 | .05 |

| 1. Medications for depression help most patients. (EFF1) | −0.44 | .05 | |

| 2. Medications …help 70% of patients…(EFF2) | −0.45 | .05 |

We examined differences in message preferences as a function of the demographic and health variables described in Table 2. Differences will be noted when (a) there was a significant difference (P<.05) for the attribute in question and (b) the groups compared differed in their preferred message for that attribute. (Groups with the same preferred message on an attribute can differ significantly in their preference utilities for that attribute if they hold their preferences with different degrees of intensity or if they disagree in their evaluations of the remaining messages for the attribute.)

With regard to the demographic variables, men and women differed in their message preferences on 2 of the 10 attributes, TOPIC (P=.03) and RISKS (P=.04). For TOPIC, women preferred the message “…ask your doctor if medication or therapy might help” (TOP2) whereas men preferred the more direct message, “If you think you have depression tell your doctor” (TOP1). When addressing the risks of antidepressants, women favored the claim that side effects can go away with continued use; men preferred the reassurance that the newer medications have fewer side effects. There was a significant difference among age groups on the attribute MEDICAL (P=.001). Every age category preferred the message comparing depression with other chronic diseases except one; the 60 and older group, comprised of just 14 respondents, had a slight preference the “chemical messengers in the brain” message. No significant effects were found for race (white versus all others), education, income, or relationship status (married/partnered versus not). U.S. respondents differed from their international counterparts in their preferred message on only one attribute, RISKS. Specifically, U.S. respondents had a slight preference for the message that side effects tend to go away with use (RISK2) whereas respondents from other countries had a slight preference for the argument that newer antidepressants have fewer side effects (RISK3).

Turning our attention to the health variables, no differences in message preferences were found based on depression or general health perception scores. A significant difference in preferences was found for RISKS when we examined the kind of provider (if any) from whom respondents were receiving care (P=.004). Respondents who were not under the care of a physician preferred the message that newer drugs have fewer side effects (RISK3), but respondents under the care of a primary care physician or psychiatrist preferred the message that side effects will go away with continued use (RISK2). Message preferences did not differ between individuals receiving counseling for depression at the time of the survey and those not undergoing counseling. A significant difference was also found for RISKS when we compared respondents taking antidepressant medications at the time of the survey with respondents not on medications (P=.048). Individuals on antidepressants preferred the message that side effects usually go away with continued use, whereas individuals not on medication for depression favored the claim that newer drugs have fewer side effects.

4. Discussion and conclusion

4.1. Discussion

To our knowledge, this study represents the first time conjoint analysis has been used in health research, in conjunction with focus groups, to test the acceptability of different message options in the formative stage of intervention development. The focus group analyses identified three broad barriers to care-seeking: misunderstandings about depression, problems communicating with one's physician, and concerns about antidepressants. The conjoint analysis results suggest that misunderstandings about depression are best addressed by conveying the idea that depression presents in a variety of ways and can include both psychological symptoms, such as sadness, and somatic symptoms, such as physical pain or fatigue. The survey results further indicate that the high rate of depression in the general population should be communicated to patients in the form of lifetime prevalence statistics.

Focus group participants' suggestions for addressing barriers to care-seeking for depression were strongly supported by the results of the conjoint survey. The focus groups felt that depression should be framed as a chronic disease requiring ongoing medical treatment, a suggestion consistent with contemporary medical thought [37]. The test message casting depression as a chronic medical condition was indeed strongly preferred by conjoint survey respondents. Survey respondents also felt that patient embarrassment about talking to a doctor about depression were best handled by reminding patients that depression can happen to anyone, an approach favored over exculpating messages that explicitly address feelings of fault or shame. The belief that depression is a private matter can prevent patients from raising the topic with their doctor. The focus group participants and survey respondents converged in their recommendation that this barrier be challenged by reminding the patient that depression affects not just the afflicted individual but the entire family. As for raising the topic of depression, women preferred the approach of asking the doctor if currently experienced feelings and symptoms might be the result of depression, whereas men preferred the more direct “tell your doctor” message.

The third set of barriers emerging from the focus group analysis pertains to low acceptability of treatments. Focus group participants believed that patients with depression symptoms are often reticent about seeking help because they fear the doctor's first response will be to give them antidepressant medications with undesirable side effects and questionable effectiveness. The results from the conjoint survey suggest that the most suitable way to address these concerns is by presenting a menu of treatment options including both counseling and medication, by noting that the side effects of antidepressant medications are usually temporary, and by depicting antidepressant therapy as an uncertain journey that may require a degree of trial and error to identify the most effective medication for an individual patient [38].

Message preferences were largely stable across groups of differing demographic and health profiles. In fact, no difference in favored message was found on 7 of 10 attributes for any of the 14 demographic and health variables examined. Indeed, most of the differences identified were for the attribute RISKS, with some survey sample segments preferring the message that side effects often go away with continued use and others preferring the claim that newer antidepressants have fewer side effects.

This study has limitations. Most notably, the focus groups and survey sample were comprised of individuals with extensive personal and/or family experiences with depression. Furthermore, conjoint analysis survey participants, having been recruited from a depression forum, are individuals for whom “depressed” is probably a fundamental part of their identity. We believe that this sample is worthy of investigation, for these are people who have made the transition from untreated individuals living with depression to individuals under treatment. However, the ideal sample would have been one that also included people who, like our target audience, have symptoms of depression but have not yet sought care.

The primary limitation of our conjoint survey is that we relied upon a convenience sample of individuals who self-selected into the depression forum community from which our sample was taken and who were willing to participate in our conjoint survey. One effect is that our sample was heavily skewed toward women and Caucasians. Although the conjoint survey results largely confirmed the observations of our more diverse focus group participants, the generalizeability of the survey results to men and minorities is weakened. It is also likely that survey respondents differ from typical primary care clinic patients in terms of symptom duration, disease severity, and perhaps propensity to communicate assertively in medical settings. Furthermore, our sample was composed of fairly educated women, 84% of whom had at least some college experience. It would be valuable in future research to examine how other individual factors, including literacy, race, culture, and personality, impact message preferences.

4.2. Conclusion

This study demonstrates the value of a mixed methods approach for developing educational materials for office-based interventions. The qualitative focus group data proved invaluable in identifying barriers to patient care-seeking and generating candidate messages for overcoming those barriers. Conjoint analysis was an effective method for testing the relative acceptability of these messages and quantifying preferences. Further research is needed to evaluate the stability of the results across populations and settings, and ultimately, to assess the personal and public health outcomes of message campaigns informed by this approach.

4.3. Practice Implications

Practitioners have many potential messages to draw upon when developing interventions to encourage patients with depressive symptoms to talk with their doctors. This study suggests that people affected by depression evaluate potential messages very differently, necessitating a careful formulation of a communication strategy for motivating care-seeking and treatment acceptance. Because patient activation will lead to better care only if the patient's physician recognizes the patient's call for help and responds positively [39], activation interventions may need to be supplemented with physician training [40, 41].

Acknowledgements

The authors gratefully acknowledge the assistance of Jennifer D. Becker, Camille Capri, Tracy Carver, Joshua DeFord, and Lindsay Willeford.

Role of Funding Source

This project was supported by a grant from the National Institute of Mental Health (1R01MH079387-01). The sponsor was not involved in data collection, analysis, interpretation, writing of the report, or decision to submit the paper for publication.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Conflict of Interest

Dr. Epstein has given two talks on patient-physician communication sponsored by Merck, in which they had no role in content, and no products were discussed. Dr. Kravitz has received research grant funding from Pfizer unrelated to depression care. The remaining authors have no potential conflicts of interest to disclose.

References

- 1.Layard R. The case for psychological treatment centres. Br Med J. 2006;332:1030–32. doi: 10.1136/bmj.332.7548.1030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Singleton N, Bumpstead R, O'Brien M, Lee A, Meltzer H. Psychiatric morbidity among adults living in private households, 2000. Int Rev Psychiatry. 2003;15:65–73. doi: 10.1080/0954026021000045967. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Weich S, Morgan L, King M, Nazareth I. Attitudes to depression and its treatment in primary care. Psychol Med. 2007;37:1239–48. doi: 10.1017/S0033291707000931. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Frayne SM, Freund KM, Skinner KM, Ash AS, Moskowitz MA. Depression management in medical clinics: does healthcare sector make a difference? Am J Med Qual. 2004;19:28–36. doi: 10.1177/106286060401900106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Freund KM, Moskowitz MA, Lin TH, McKinlay JB. Early antidepressant therapy for elderly patients. Am J Med. 2003;114:15–19. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9343(02)01420-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lecrubier Y. Widespread underrecognition and undertreatment of anxiety and mood disorders: Results from 3 European studies. J Clin Psychiatry. 2007;68(suppl 2):36–42. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tylee A, Gandhi MRC. The importance of somatic symptoms in depression in primary care. Prim Care Companion J Clin Psychiatry. 2005;7:167–76. doi: 10.4088/pcc.v07n0405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cassano P, Fava M. Depression and public health: an overview. Journal of Psychosomatic Research. 2002;53:849–57. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3999(02)00304-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Coulehan JL, Schulberg HC, Block MR, Madonia MJ, Rodriguez E. Treating depressed primary care patients improves their physical, mental and social functioning. Arch Intern Med. 1997;157:1113–20. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Williams JW, Jr, Mulrow CD, Chiquette E, Noël PH, Aguilar C, Cornell J. A systematic review of newer pharmacotherapies for depression in adults: evidence report summary. Ann Intern Med. 2000 May 2;132(9):743–56. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-132-9-200005020-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bortolotti B, Menchetti M, Bellini F, Montaguti MB, Berardi D. Psychological interventions for major depression in primary care: a meta-analytic review of randomized controlled trials. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2008;30:293–302. doi: 10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2008.04.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Howland RH. Somatic therapies for seasonal affective disorder. J Psychosoc Nurs Ment Health Serv. 2009;47:17–20. doi: 10.3928/02793695-20090101-07. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wright A, McGorry PD, Harris MG, Jorm AF, Pennell K. Development and evaluation of a youth mental health community awareness campaign – the Compass Strategy. BMC public Health. 2006;6:215. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-6-215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jorm AF, Christensen H, Griffiths KM. The impact of BeyondBlue: the national depression initiative on the Australian public's recognition of depression and beliefs about treatments. Aust N Z J Psychiatry. 2005;39:248–54. doi: 10.1080/j.1440-1614.2005.01561.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Merritt RK, Price JR, Mollison J, Geddes JR. A cluster randomized controlled trial to assess the effectiveness of an intervention to educate students about depression. Psychol Med. 2007;37:363–72. doi: 10.1017/S0033291706009056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rochlen AB, McKelley RA, Pituch KA. A preliminary examination of the “Real Men. Real Depression” campaign. Psychology of Men & Masculinity. 2006;7:1–13. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Beaudoin CE. Assessment of a media campaign and related crisis help line following Hurricane Katrina. Public Health Rep. 2008;123:646–51. doi: 10.1177/003335490812300515. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Frank RG, Pindyck T, Donahue SA, Pease EA, Foster MJ, Felton CJ, Essock SM. Impact of a media campaign for disaster mental health counseling in post-September 11 New York. Psychiatr Serv. 2006;57:1304–8. doi: 10.1176/ps.2006.57.9.1304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Paykel ES, Hart D, Priest RG. Changes in public attitudes to depression during the Defeat Depression Campaign. Br J Psychiatry. 1998;173:519–522. doi: 10.1192/bjp.173.6.519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hegerl U, Althaus D, Schmidtke A, Niklewski G. The alliance against depression: 2-year evaluation of a community-based intervention to reduce suicidality. Psychol Med. 2006;36:1225–33. doi: 10.1017/S003329170600780X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Paton J, Jenkins R, Scott J. Collective approaches for the control of depression in England. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2001;36:423–8. doi: 10.1007/s001270170019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zung WW, Broadhead WE, Roth ME. Prevalence of depressive symptoms in primary care. J Fam Pract. 1993;37:337–44. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Norquist GS, Regier DA. The epidemiology of psychiatric disorders and the de facto mental health care system. Annu Rev Med. 1996;47:473–9. doi: 10.1146/annurev.med.47.1.473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wang PS, Lane M, Olfson M, Pincus HA, Wells KB, Kessler RC. Twelve-month use of mental health services in the United States: results from the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2005;62:629–40. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.62.6.629. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gustafsson A, Herrmann A, Huber F. Conjoint measurement: methods and applications. 4th ed. Springer; New York: 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ryan M, Scott DA, Reeves C, Bate A, van Teijlingen ER, Russell EM, Napper M, Robb CM. Eliciting public preferences for healthcare: a systematic review of techniques. Health Technol Assess. 2001;5(5):1–186. doi: 10.3310/hta5050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mele NL. Conjoint analysis: using a market based research model for healthcare decision making. Nurs Res. 2008;57:220–4. doi: 10.1097/01.NNR.0000319499.52122.d2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Stanek EJ, Oates MB, McGhan WF, Denofrio D, Loh E. Preferences for treatment outcomes in patients with heart failure: symptoms versus survival. J Card Fail. 2000;6:225–232. doi: 10.1054/jcaf.2000.9503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Albus C, Schmeisser N, Salzberger B, Fätkenheuer G. Preferences regarding medical and psychosocial support in HIV-infected patients. Patient Educ Couns. 2005;56:16–20. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2003.11.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Fraenkel L, Bulanski B, Wittink D. Patient willingness to take teriparatide. Patient Educ Couns. 2007;65:237–44. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2006.08.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Dwight-Johnson M, Lagomasino IT, Aisenberg E, Hay J. Using conjoint analysis to assess depression treatment preferences among low-income Latinos. Psychiatr Serv. 2004;55:934–36. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.55.8.934. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sawtoothsoftware.com [homepage on the Internet] Sawtooth Software, Inc.; Sequim, WA: 2008. Available from: http://www.sawtoothsoftware.com/ [Google Scholar]

- 33.Green P, Krieger A, Wind J. Thirty years of conjoint analysis: reflections and prospects. Interfaces. 2001;31(3):S56–S73. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Tumbusch JJ. Validation of adaptive conjoint analysis (ACA) versus standard concept testing. Sawtooth Software, Inc; Sequim, WA: 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ryan M, McIntosh E, Shackley P. Using conjoint analysis to elicit the views of health service users: an application to the patient health card. Health Expect. 1998;1:117–129. doi: 10.1046/j.1369-6513.1998.00024.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sawtooth Software . The ACA/Hierarchical Bayes v3.0 technical paper. Sawtooth Software, Inc.; Sequim, WA: 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Scott J. Depression should be managed like a chronic disease. Br Med J. 2006;332:985–6. doi: 10.1136/bmj.332.7548.985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Warden D, Rush AJ, Trivedi MH, Fava M, Wisniewski SR. The STAR*D Project results: a comprehensive review of findings. Curr Psychiatry Rep. 2007;9:449–59. doi: 10.1007/s11920-007-0061-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Christensen H, Griffiths KM, Gulliver A, Clack D, Kljakovic M, Wells L. Models in the delivery of depression care: a systematic review of randomised and controlled intervention trials. BMC Fam Pract. 2008;9:25. doi: 10.1186/1471-2296-9-25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Clayton JM, Butow PN, Tattersall MH, Devine RJ, Simpson JM, Aggarwal G, Clark KJ, Currow DC, Elliott LM, Lacey J, Lee PG, Noel MA. Randomized controlled trial of a prompt list to help advanced cancer patients and their caregivers to ask questions about prognosis and end-of-life care. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25:715–23. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.06.7827. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Rix S, Paykel ES, Lelliott P, Tylee A, Freeling P, Gask L, Hart D. Impact of a national campaign on GP education: an evaluation of the Defeat Depression campaign. Br J Gen Pract. 1999;49(439):99–102. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]