Abstract

The effects of ligand activation of PPARβ/δ were examined in the mouse mammary tumor cell line (C20). Expression of PPARβ/δ was markedly lower in C20 cells as compared to the human non-tumorigenic mammary gland derived cell line (MCF10A) and mouse keratinocytes. Ligand activation of PPARβ/δ in C20 cells caused upregulation of the PPARβ/δ target gene angiopoietin-like 4 (Angptl4). Inhibition of C20 cell proliferation and clonogenicity was observed following treatment with GW0742 or GW501516, two highly specific PPARβ/δ ligands. In addition, an increase in apoptosis was observed in C20 cells cultured with 10 µM GW501516 that preceded the observed inhibition of cell proliferation. Results from this study show that proliferation of the C20 mouse mammary gland cancer cell line is inhibited by ligand activation of PPARβ/δ due in part to increased apoptosis.

Keywords: peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-β/δ, mammary gland cancer, cell proliferation, apoptosis

1. Introduction

Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptors (PPARs) are ligand activated transcription factors and members of the nuclear hormone receptor superfamily that include three isoforms: PPARα, PPARγ, and PPARβ/δ [1]. Given that PPARs are critical in the regulation of lipid homeostasis and that their activation modulates diseases including obesity, diabetes, and cancer [1], the development of synthetic ligands targeting these receptors has great therapeutic potential. Indeed, fibrate drugs are PPARα ligands that effectively lower triglycerides [2; 3], and thiazolidinediones are PPARγ agonists used to treat type II diabetes [4; 5]. High affinity PPARβ/δ agonists such as GW501516 are under development to treat metabolic syndrome [6], however the use of these agonists in humans has been subject to controversy regarding the role of PPARβ/δ in tumorigenesis [7; 8; 9; 10].

Ligand activation of PPARβ/δ can modulate lipid and glucose homeostasis. For example, in obese non-human primates administration of GW501516 increases serum high-density lipoproteins (HDL) levels and lowers serum triglyceride levels [11]. In addition, ligand activation of PPARβ/δ upregulates fatty acid metabolizing enzymes promoting fatty acid catabolism in skeletal muscle [12]. There are also multiple reports demonstrating that PPARβ/δ has potent anti-inflammatory activities in a variety of model systems [13]. Combined, these observations indicate that PPARβ/δ should be a promising target for treating various metabolic diseases.

There is strong evidence indicating that ligand activation of PPARβ/δ induces terminal differentiation of epithelium and other cells [7; 9]. Induction of terminal differentiation is typically associated with concomitant increased apoptotic signaling and/or decreased cell proliferation. Consistent with these facts, there is evidence that PPARβ/δ induces apoptosis in keratinocytes [14; 15] and inhibits cell proliferation of colonocytes, keratinocytes, cardiomyocytes, fibroblasts and endothelial cells [7; 9; 10; 16]. The role of PPARβ/δ in cancer cell growth remains more controversial as there are reports showing that ligand activation of this receptor either potentiates, has no effect, or attenuates cell proliferation [7; 9; 10; 16]. For example, ligand activation of PPARβ/δ has no effect on the proliferation of estrogen receptor-negative human breast cancer cell lines but increases proliferation of estrogen receptor-positive human breast cancer cell lines in preconfluent cultures grown in medium containing charcoal-stripped fetal calf serum [17]. In contrast, the induction of differentiation by sodium butyrate is associated with increased expression of PPARβ/δ in the MCF7 human breast cancer cell line [18] and ligand activation of PPARβ/δ inhibits cell proliferation of MCF7 cells cultured in medium with and without fetal calf serum [19]. In vivo analysis in mouse models suggests that PPARβ/δ promotes mammary gland cancer [20; 21], although these studies have limitations including small sample size, no dose response analysis and no quantification of tumor multiplicity. Since some of the described disparities for PPARβ/δ in modulating mammary gland cancer cell proliferation could be due to species differences, the present study examined the direct effects of activating PPARβ/δ in a mammary gland cancer cell line [22] derived from MMTV-cyclooxygenase-2 (MMTV-Cox2) transgenic mice (C20).

2. Materials and methods

2.1 Cell culture and cell proliferation analysis

Control MCF10A cells were obtained from American Type Culture Collection (ATCC; Manassas, VA). The C20 cells used for these studies were derived from an MMTV-Cox2 transgenic mouse line and have been previously described [22]. The MCF10A cells were cultured in Mammary Epithelium Basal Medium with added supplements, 50 mg/L cholera toxin and 10% fetal calf serum (FCS). C20 cells were cultured in Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle Medium (DMEM) with 10% FCS. For analysis of cell proliferation, cells were plated on 12 well dishes at a density of ~20,000 cells per well 24 h prior to determining plating efficiency with a Z1 Coulter particle counter® at time 0 (Beckman Counter, Hialeah, FL). After plating efficiency was determined, cells were cultured in medium containing GW0742 or GW501516 (0–10 µM) in the presence or absence of serum. For some analysis, charcoal-stripped serum was used. Cell number was quantified every 24 h with a Z1 coulter particle counter® (Beckman Counter, Hialeah, FL). Triplicate samples for each treatment were examined at each time point and each replicate was counted three times.

2.2 RNA analysis and real-time quantitative polymerase chain reaction

C20 cells were cultured until they were approximately 80% and were then treated with either GW0742 or GW501516 (0–10 µM). After 8 hours of treatment, total mRNA was isolated from the cells using TRIZOL and following the manufacturer’s recommended protocol (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA). The mRNA encoding angiopoietin-like 4 (Angptl4) and glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase (Gapdh) was quantified using quantitative realtime polymerase chain reaction (qPCR) analysis. The cDNA was generated using 2.5 µg total RNA with MultiScribe Reverse Transcriptase kit (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA). Primers were designed for qPCR using the Primer Express software (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA). The sequence and GenBank accession number for the forward and reverse primers used to quantify mRNA for Angptl4 (NM_020581) was: forward, 5’- TTCTCGCCTACCAGAGAAGTTGGG -3’ and reverse, 5’- CATCCACAGCACCTACAACAGCAC -3’. The mRNA for Angptl4 was normalized to Gapdh (BC083149) mRNA using the following primers: forward, 5’-GGTGGAGCCAAAAGGGTCAT-3’ and reverse, 5’-GGTTCACACCCATCACAAACAT-3’. Real-time PCR reactions were carried out using SYBR green PCR master mix (Finnzymes, Espoo, Finland) in the iCycler and detected using the MyiQ Real-Time PCR Detection System (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Hercules, CA). The following conditions were used for PCR: 95 C for 15 s, 94 C for 10 s, 60 C for 30 s and 72 C for 30 s and repeated for 45 cycles. The PCR included a no template reaction to control for contamination and/or genomic amplification. All reactions had >95% efficiency.

2.3 Quantitative western blot analysis

MCF10A and C20 cells were cultured on 100 mm dishes. Soluble protein was isolated from treated cells using MENG buffer (25 mM MOPS, 2 mM EDTA, 0.02% NaN3, and 10% glycerol, pH 7.5) containing 500 mM NaCl, 20 mM NaMo, 1% Nonidet P-40, and protease inhibitors. A total of 50 µg of protein per sample was resolved using SDS-polyacrylamide gels. The samples were transferred onto polyvinylidene fluoride membrane using an electroblotting method. The membranes were blocked with 5% dried milk in Tris-buffered saline/Tween-20 and incubated at 4°C overnight with primary antibodies. The following antibodies were used: anti-LDH (Rockland, Gilbertsville, PA), anti-PPARβ/δ (K-20; Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA and anti-PPARβ/δ [23]), and anti-α-smooth muscle actin (αSMA; Chemicon International, Temecula, CA). After treatment with the primary antibody, membranes were washed and then incubated with biotinylated secondary antibody (Jackson ImmunoResearch Laboratories, West Grove, PA), and immunoreactive proteins were detected with 125I-labeled streptavidin using phosphorimaging analysis. Hybridization signals for the proteins of interest were normalized to the hybridization signal of the housekeeping gene lactate dehydrogenase (LDH). A minimum of three independent samples were analyzed for each cell line.

2.4 Flow cytometry

C20 cells were plated on six-well plates with DMEM and 10% FCS. Twenty-four h post plating, cells were treated with GW501516 (0, 1.0 µM or 10 µM) for 24–72 h. A minimum of three independent samples for each treatment group were examined for each time point.

Examination of bromodeoxyuridine (BrdU) labeling was performed as previously described [24]. Briefly, during the last hour of cell culture, cells were pulsed with 10 µg/mL of BrdU for 1 hour. The cells were then trypsinized, washed in cold-phosphate buffered saline (PBS), and pelleted. Cells were then fixed in ice-cold 70% ethanol, incubated with wash buffer (PBS + 0.5% Tween-20), and pelleted. The cells were then incubated in denaturing solution (2M HCl/0.5% Triton X-100) for 20 minutes at room temperature. After incubating in wash buffer and pelleting, the cell pellet was resuspended in 0.1 M sodium borate. The cells were washed again and pelleted. The cells were then resuspended with a 1:100 dilution of FITC-labeled anti-BrdU antibody (Phoenix Flow Systems, San Diego, CA) in dilution buffer (PBS + 0.5% Tween−20 + 0.5% BSA) for 20 minutes in dark. Cells were then washed again and counterstained with 10 µg/mL propidium iodide (PI) solution (PBS + 0.1% Triton X-100) and analyzed by flow cytometry to detect both fluorescein and PI using a FC500 flow cytometer (Beckman Coulter, Miami Lakes, FL).

For annexin V analysis of apoptosis, cells were trypsinized, washed in cold phosphate-buffered saline, and pelleted. The cells were then resuspended in 100 µL of annexin V buffer (10 mM HEPES, pH 7.4, 140 mM NaCl, and 2.5 mM CaCl2), and 5 µL of FITC-annexin V buffer (450 µl) was added to the cells with 2 µg of PI, and the cells were analyzed by flow cytometry. Approximately 10,000 cells/sample were analyzed using an EPICS-XL-MCL flow cytometer (Beckman Coulter, Miami Lakes, FL) fitted with a single 15-mW argon ion laser providing excitation at 488 nm. Cells stained with FITC were monitored through a 525-nm bandpass filter. Early apoptosis was defined as the percentage of cells that were annexin V-positive and PI-negative, and late apoptosis/necrosis was defined as the percentage of cells that were annexin V-negative and PI-positive.

2.5 Colony formation assay

C20 cells were cultured as described above, trypsinized, quantified with a Z1 Coulter particle counter after dilution in DMEM with 10% FCS, and plated onto six-well plates with either 200 or 400 cells per well. After allowing the cells to adhere for 2 h, cells were treated with medium containing either: 0 (DMSO control), 0.1, 1.0 or 10 µM GW0742. Culture medium was changed periodically during the 10 d culture period at which time cell colonies were fixed with 6% (v/v) glutaraldehyde and stained with 0.5% (w/v) crystal violet. Colonies were counted with a stereomicroscope. Colony number and size were quantified using Image J software (version 1.37, National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD). Plating efficiency and surviving fractions were calculated as previously described [25] from six independent samples per treatment group.

2.6 Statistical analysis

Data were analyzed for statistical significance using analysis of variance and the Bonferroni post test (Prism 5.0, GraphPad Software Inc., La Jolla, CA).

3. Results

3.1 Expression and function of PPARβ/δ in C20 cells

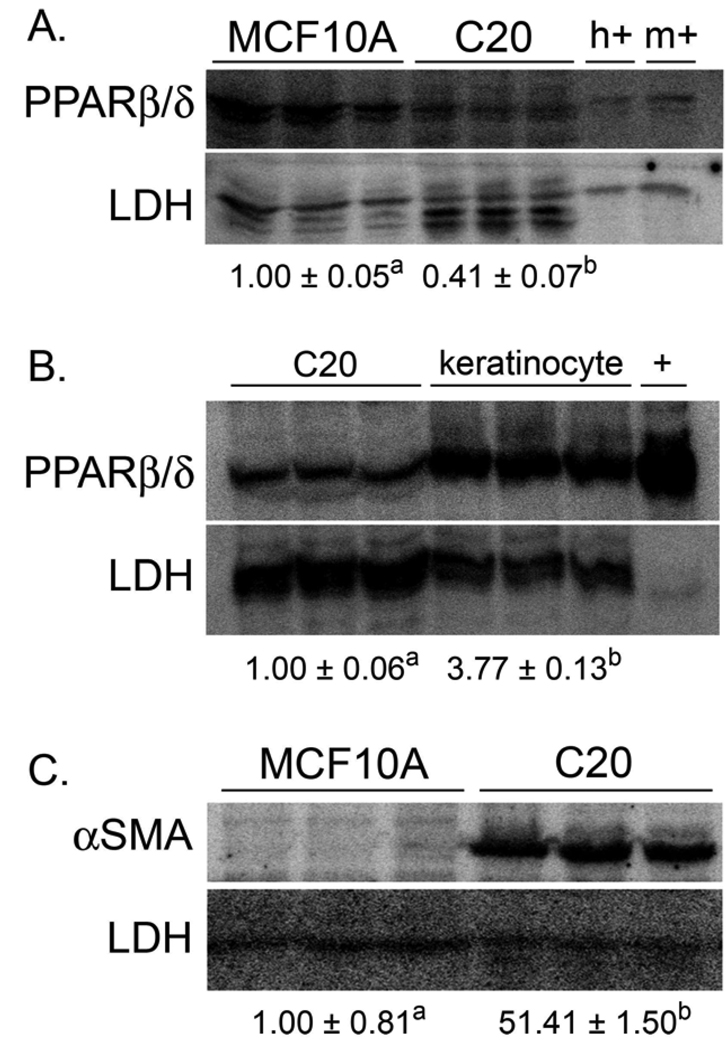

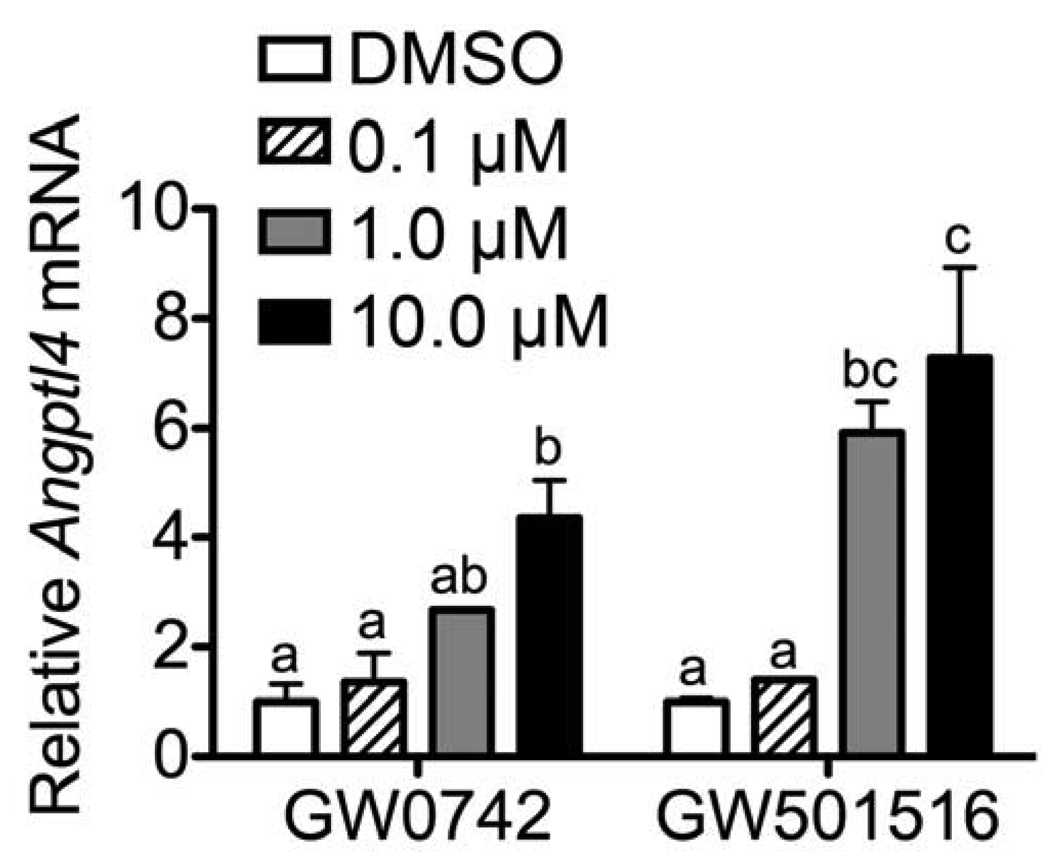

Expression of PPARβ/δ protein was examined in the mouse C20 cancer cell line and compared to the human non-cancerous breast tissue cell line, MCF10A. Expression of PPARβ/δ in the C20 cell line was less than 50% that found in the MCF10A cell line (Fig. 1A). Similarly, expression of PPARβ/δ was substantively lower in the C20 cell line as compared to normal mouse keratinocytes (Fig. 1B), cells that express relatively high levels of PPARβ/δ protein [23]. To verify that the C20 cells maintained their tumorigenic phenotype, a quantitative western blot was performed for αSMA, a marker of myofibroblast activity. Expression of αSMA positive myofibroblasts is used as an indicator of cancer progression [26]. Consistent with past findings [27], expression of αSMA was markedly higher in the C20 cell line as compared to the control MCF10A cells (Fig. 1C). To confirm that PPARβ/δ is functional in C20 cells, expression of a known PPARβ/δ target gene Angptl4 was examined. Angptl4 mRNA was increased in a dose-dependent manner by both GW0742 and GW501516 in C20 cells (Fig. 2).

Fig. 1.

Expression of PPARβ/δ and evidence of myofibroblast activity in C20 cells. Quantitative western blot were performed to quantify expression of PPARβ/δ and αSMA as described in Materials and methods. (A) Expression of PPARβ/δ is lower in the mouse C20 cancer cell line as compared to the human MCF10A control cell line. Lysates from COS1 cells transfected with human PPARβ/δ (h+) or mouse PPARβ/δ (m+) were used as positive controls. (B) Expression of PPARβ/δ is lower in the mouse C20 cancer cell line as compared to mouse keratinocytes. Lysate from COS1 cells transfected with mouse PPARβ/δ (+) was used as a positive control. (C) Expression of αSMA is markedly higher in the mouse C20 cancer cell line as compared to the human MCF10A control cell line, indicative of a myofibroblast phenotype. Values are the average-fold change between the groups and represent the mean ± S.E.M. Values with different letters are significantly different, P ≤ 0.05.

Fig. 2.

Ligand activation of PPARβ/δ target genes. Expression of mRNA encoding the known PPARβ/δ target gene Angptl4 was quantified in C20 cells. Values are the average-fold change compared with control treatment and represent the mean ± S.E.M. Values with different letters are significantly different, P ≤ 0.05.

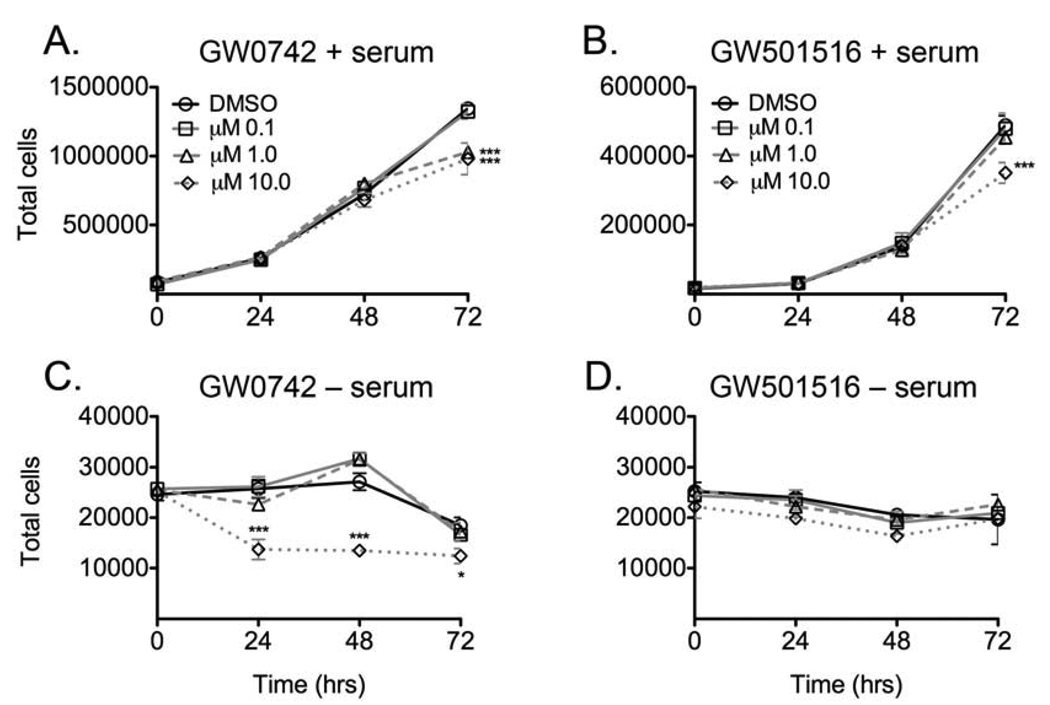

3.2 Ligand activation of PPARβ/δ inhibits cell growth of mouse C20 mammary gland cancer cell line

Proliferation of the C20 cell line was examined following exposure to either GW0742 or GW501516 in the presence or absence of FCS. This was performed because previous work by others suggested that the presence of hormones or growth factors in serum could mask any potential stimulatory effect of the PPARβ/δ ligands [17]. Inhibition of cell proliferation was observed in the C20 cell line in response to either 1.0 or 10 µM GW0742 (Fig. 3A) and 10 µM GW501516 (Fig. 3B) in the presence of culture medium FCS. Cells cultured in medium lacking FCS exhibited a significant decrease in proliferation but only in response to 10 µM GW0742 (Fig. 3C). Results similar to those observed with culture medium in the absence of FCS were found when cell proliferation was examined in medium containing GW501516 using 1% and 2% charcoal stripped FCS (data not shown). An increase in cell proliferation was not observed under any of these culture conditions in the presence of PPARβ/δ ligands. While the EC50 for PPARβ/δ transactivation in a cell-based in vitro model is ~ 1 nM [28], these results show that inhibition of C20 cell growth occurs at concentrations that are relatively high as compared to the in vitro EC50, but still within the range known to specifically activate PPARβ/δ [29].

Fig. 3.

Effect of GW0742 and GW501516 on cell proliferation in the mouse C20 mammary gland cancer cell line, in the presence or absence of culture medium FCS. Cells were treated with the indicated concentration of ligand at day zero and cell number was quantified every day for 3 days as described in Materials and methods. Values represent the mean ± S.E.M. *Significantly different from the DMSO control, P ≤ 0.05.

3.3 Ligand activation of PPARβ/δ increases apoptosis

The PPARβ/δ ligand dependent decrease in cell proliferation (Fig. 3) could be due to modulation of apoptosis and/or inhibition of cell cycle progression. Flow cytometric analysis using annexin V was performed to determine whether the inhibition of cell proliferation was due to induced apoptosis as a result of ligand activation of PPARβ/δ. A small increase in cells undergoing early apoptosis was observed in C20 cells after 24 h of treatment with 1 µM GW501516 which was not significant (Table 1). However, a significant increase in early apoptosis was observed in C20 cells following 24 h treatment with 10 µM GW501516 dose (Table 1). No changes in early apoptosis, late apoptosis or necrosis were observed 48 h post-GW501516 treatment (Table 1). Flow cytometric analysis of BrdU-labeled C20 cells showed no differences in relative BrdU-positive/PI-negative cells following treatment with either 1 or 10 µM GW501516 for 24 (data not shown) or 48 h (Table 2). Similarly, no differences in cell cycle progression were found following treatment with either 1 or 10 µM GW501516 for 24 (data not shown) or 48 h (Table 2). No changes in cell cycle progression were found in C20 cells following treatment with either 1 or 10 µM GW0742 (data not shown).

Table 1.

Flow cytometry analysis of annexin V/PI-labeled C20 cells after treatment with GW501516.

| Hours | Treatment | Early Apoptosis | Late Apoptosis | Necrosis |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 24 | DMSO | 3.0 ± 0.3 | 2.7 ± 0.6 | 0.2 ± 0.0 |

| 24 | 1 µM GW501516 | 3.4 ± 0.3 | 2.1 ± 0.1 | 0.2 ± 0.0 |

| 24 | 10 µM GW501516 | 5.9 ± 0.5* | 2.2 ± 0.2 | 0.2 ± 0.0 |

| 48 | DMSO | 6.6 ± 0.9 | 1.2 ± 0.1 | 0.2 ± 0.1 |

| 48 | 1 µM GW501516 | 7.0 ± 0.9 | 1.1 ± 0.0 | 0.1 ± 0.0 |

| 48 | 10 µM GW501516 | 6.5 ± 1.0 | 1.1 ± 0.1 | 0.1 ± 0.0 |

C20 cells were treated in triplicate for the indicated time and concentration of GW501516 and labeled with a FITC-labeled anti-annexin V antibody and PI as described in the Materials and methods. Values represent the mean ± S.E.M.

Significantly different from the DMSO control, P ≤ 0.05.

Table 2.

Flow cytometry analysis of BrdU/PI-labeled C20 cells after treatment with GW501516.

| Hours | Treatment | %G1 | %S | %G2 | %BrdU |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 48 | DMSO | 31.7 ± 2.2 | 32.6 ± 0.7 | 35.6 ± 1.5 | 31.7 ± 0.4 |

| 48 | 1 µM GW501516 | 35.3 ± 1.6 | 37.1 ± 2.4 | 27.5 ± 4.2 | 31.7 ± 0.4 |

| 48 | 10 µM GW501516 | 34.9 ± 1.0 | 31.8 ± 2.6 | 33.4 ± 1.7 | 30.2 ± 0.8 |

C20 cells were treated in triplicate for the indicated time and concentration of W501516, labeled with a FITC-labeled anti-BrdU antibody and propidium iodide, and examined for cell cycle progression as described in the Materials and methods. Values represent the mean ± S.E.M. %BrdU = the average percentage of cells that were BrdU-positive.

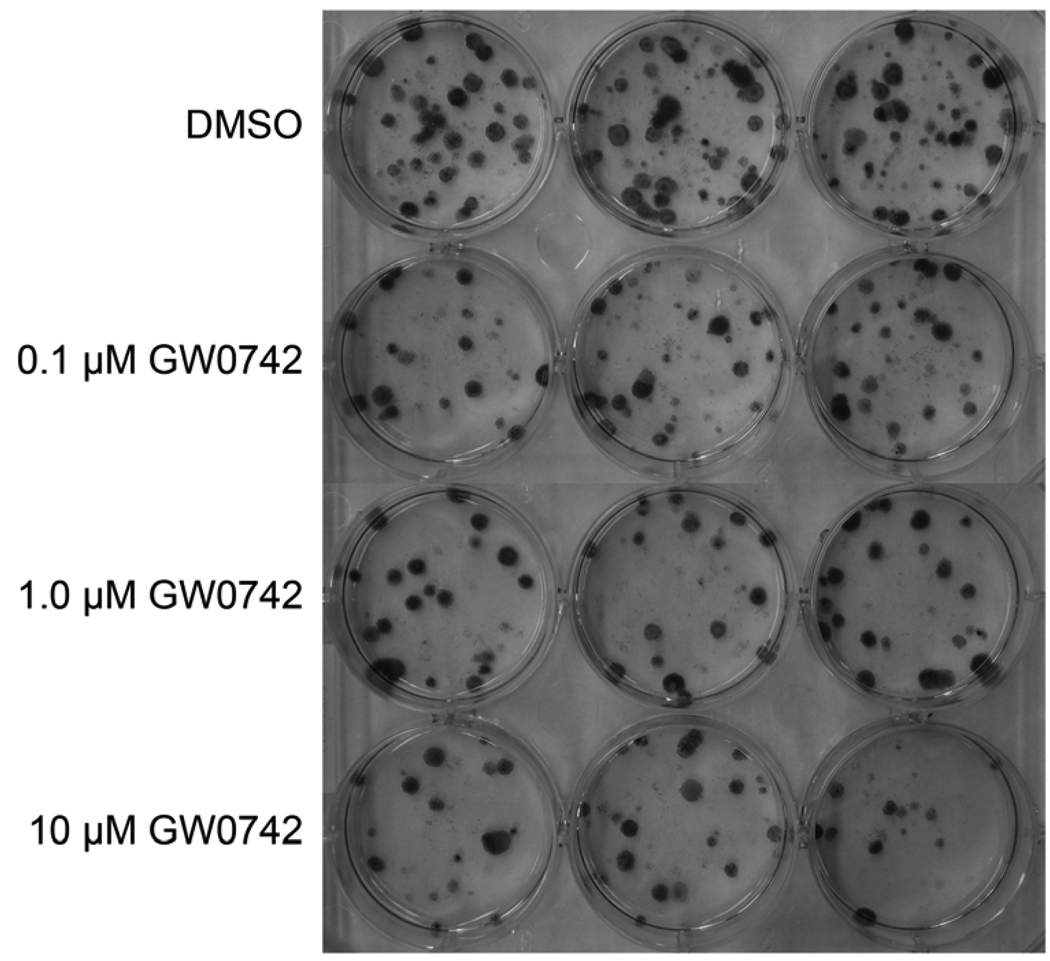

3.4 Ligand activation of PPARβ/δ inhibits colon formation

Since a good in vitro correlate of in vivo tumorigenesis is clonogenicity, a colony formation assay was performed. Consistent with the observed inhibition of cell growth observed in vitro (Fig. 3), the clonogenicity of C20 cells was significantly reduced in response to ligand activation of PPARβ/δ with GW0742 (Fig. 4). The plating efficiency [(number of colonies/total cells plated) X 100] of control cells was 9.3 ± 0.5. The surviving fraction [(percentage of colonies after treatment/(total cells plated X plating efficiency)) X 100] was 65 ± 6, 53 ± 5 and 44 ± 6 for the cells treated with 0.1, 1.0 or 10 µM GW0742, respectively.

Fig. 4.

Effect of GW0742 on colony formation in the mouse C20 mammary gland cancer cell line. A clonogenic assay was performed using C20 cells treated with the indicated concentration of ligand for 10 days as described in Materials and methods. Representative photographs of colonies from C20 cells plated at a concentration of 400 cells/well at the beginning of the experiment: control (DMSO), 0.1, 1.0 or 10 µM GW0742.

4. Discussion

Results from the present study provide new evidence demonstrating a functional role for PPARβ/δ in cell cycle control in a mouse mammary gland cancer line. Expression of PPARβ/δ is notably lower in C20 cells as compared to both a control human mammary epithelial cell line and mouse keratinocytes. Since mouse keratinocytes are known to express relatively high levels of PPARβ/δ [23], this demonstrates that the relative expression of PPARβ/δ is lower in a transformed mouse cell line. This is of interest because it is currently uncertain whether PPARβ/δ expression is increased, decreased or unchanged in tumor cells as compared to normal cells [9; 30]. It was previously hypothesized that PPARβ/δ was directly up-regulated by the APC/β-CATENIN/TCF4 transcriptional network [31], but recent findings suggest that this may not be the case [9; 30]. Results from the present study support other reports suggesting that PPARβ/δ may in fact be down-regulated in tumors. Despite the relatively lower expression levels of PPARβ/δ in the C20 mammary gland cancer cells as compared to normal cells, it is clearly functional in C20 cells since expression of the known target gene Angptl4 is up-regulated following treatment with a PPARβ/δ ligand.

Previous reports suggest that ligand activation of PPARβ/δ either inhibits [19], has no effect [17], or potentiates proliferation [17] of human breast cancer cell lines. In vivo analysis in mice suggests that ligand activation of PPARβ/δ promotes mammary gland cancer [20; 21], however these studies have limitations that preclude definitive demonstration of this tumor promoting effect. To directly characterize the effect of ligand activation of PPARβ/δ on cell proliferation and apoptosis in the C20 mammary gland cancer cell line, three approaches were pursued: direct counting, flow cytometry and a colony formation assay. Results from these analyses indicate that activating PPARβ/δ in C20 cells causes inhibition of cell proliferation in response to GW0742 or GW501516. This effect appears to be mediated by increased apoptosis as shown by flow cytometry since the change in the percentage of apoptotic cell preceded the observed inhibition of cell proliferation. These findings clearly demonstrate that ligand activation of PPARβ/δ, in a mouse mammary gland cancer cell line that retains its myofibroblast phenotype (e.g. increased expression of αSMA), causes inhibition of cell proliferation and clonogenicity. This is consistent with a past report showing inhibition of proliferation in the human MCF7 breast cancer cell line [19]. In contrast, it was recently shown that administration of GW501516 caused an increase in the percentage of mice with mammary adenosquamous or squamous cell carcinomas as compared to controls, but tumor multiplicity or tumor size was not reported in this study [21]. Interestingly, expression of Cyclin D1 mRNA was also lower as determined by microarray analysis in tumors from GW501516-treated mice as compared to tumors from control mice [21]. It was also recently shown that mammary tumor incidence is decreased in MMTV-Cox2 transgenic mice that lack expression of PPARβ/δ [20]. In this study, expression of CYCLIN D1 was lower in MMTV-Cox2/Pparβ/δ-null mice as compared to controls but this immunohistochemical analysis was not quantified [20]. It is also worth noting that tumor multiplicity or tumor size was not reported in this study and the genetic background of mice examined was mixed (FVB X C57BL/6). This is important since MMTV-Cox2 transgenic mice are less susceptible to mammary tumorigenesis on a C57BL/6 genetic background as compared to MMTV-Cox2 transgenic mice on an FVB genetic background [32]. Additionally, since tumor multiplicity and tumor size was not quantified, it is uncertain whether ligand activation of PPARβ/δ in these in vivo models would influence these endpoints similar to the effects observed in the present study. The reason why the present study showing that ligand activation of PPARβ/δ directly inhibits cell proliferation and clonogenicity of a mouse mammary gland cancer cell line while in vivo analysis suggests that ligand activation of PPARβ/δ promotes mammary gland tumor growth cannot be determined from the present study. There is evidence that the effect of activating PPARβ/δ in tumor stromal cells versus tumor cells could explain this difference [33]. Further studies are necessary to examine the specific mechanisms underlying the effects of ligand activation of PPARβ/δ in mammary gland cancer models and should include dose response analysis and more quantitative measures of cell proliferation.

Acknowledgements

The authors gratefully acknowledge Drs. Timothy Hla and Mallika Ghosh for providing the C20 cell line, Drs. Andrew Billin and Timothy Willson for providing GW0742 and Elaine Kunze, Susan Magargee, and Nicole Bem from the Center for Quantitative Cell Analysis at the Huck Institutes of Life Sciences of The Pennsylvania State University for their technical support with flow cytometry and data analysis. This work supported in part by CA124533 (J.M.P.).

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Conflict of interest statement

All the authors have no financial and personal relationships with other people or organizations that could inappropriately influence this work.

References

- 1.Lee CH, Olson P, Evans RM. Minireview: lipid metabolism, metabolic diseases, and peroxisome proliferator-activated receptors. Endocrinology. 2003;144:2201–2207. doi: 10.1210/en.2003-0288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Goldenberg I, Benderly M, Goldbourt U. Update on the use of fibrates: focus on bezafibrate. Vascular health and risk management. 2008;4:131–141. doi: 10.2147/vhrm.2008.04.01.131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Peters JM, Cheung C, Gonzalez FJ. Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-alpha and liver cancer: where do we stand? J Mol Med. 2005;83:774–785. doi: 10.1007/s00109-005-0678-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chiarelli F, Di Marzio F. Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-gamma agonists and diabetes: current evidence and future perspectives. Vascular health and risk management. 2008;4:297–304. doi: 10.2147/vhrm.s993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Willson TM, Brown PJ, Sternbach DD, Henke BR. The PPARs: from orphan receptors to drug discovery. J Med Chem. 2000;43:527–550. doi: 10.1021/jm990554g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Pelton P. GW-501516 GlaxoSmithKline/Ligand. Curr Opin Investig Drugs. 2006;7:360–370. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Burdick AD, Kim DJ, Peraza MA, Gonzalez FJ, Peters JM. The role of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-β/δ in epithelial cell growth and differentiation. Cell Signal. 2006;18:9–20. doi: 10.1016/j.cellsig.2005.07.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Muller R, Rieck M, Muller-Brusselbach S. Regulation of Cell Proliferation and Differentiation by PPARβ/δ. PPAR research. 2008;2008:614852. doi: 10.1155/2008/614852. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Peters JM, Hollingshead HE, Gonzalez FJ. Role of peroxisome-proliferator-activated receptor β/δ (PPARβ/δ) in gastrointestinal tract function and disease. Clin Sci (Lond) 2008;115:107–127. doi: 10.1042/CS20080022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Peters JM, Gonzales FJ. Sorting out the functional role(s) of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-β/δ (PPARβ/δ) in cell proliferation and cancer. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2009 doi: 10.1016/j.bbcan.2009.06.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Oliver WR, Jr, Shenk JL, Snaith MR, Russell CS, Plunket KD, Bodkin NL, Lewis MC, Winegar DA, Sznaidman ML, Lambert MH, Xu HE, Sternbach DD, Kliewer SA, Hansen BC, Willson TM. A selective peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor delta agonist promotes reverse cholesterol transport. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2001;98:5306–5311. doi: 10.1073/pnas.091021198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Luquet S, Lopez-Soriano J, Holst D, Gaudel C, Jehl-Pietri C, Fredenrich A, Grimaldi PA. Roles of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor δ (PPARδ) in the control of fatty acid catabolism. A new target for the treatment of metabolic syndrome. Biochimie. 2004;86:833–837. doi: 10.1016/j.biochi.2004.09.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kilgore KS, Billin AN. PPARβ/δ ligands as modulators of the inflammatory response. Curr Opin Investig Drugs. 2008;9:463–469. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Borland MG, Foreman JE, Girroir EE, Zolfaghari R, Sharma AK, Amin SM, Gonzalez FJ, Ross AC, Peters JM. Ligand Activation of Peroxisome Proliferator-Activated Receptor-β/δ (PPARβ/δ) Inhibits Cell Proliferation in Human HaCaT Keratinocytes. Mol Pharmacol. 2008;74:1429–1442. doi: 10.1124/mol.108.050609. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kim DJ, Murray IA, Burns AM, Gonzalez FJ, Perdew GH, Peters JM. Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-β/δ (PPARβ/δ) inhibits epidermal cell proliferation by down-regulation of kinase activity. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:9519–9527. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M413808200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Peraza MA, Burdick AD, Marin HE, Gonzalez FJ, Peters JM. The toxicology of ligands for peroxisome proliferator-activated receptors (PPAR) Toxicol Sci. 2006;90:269–295. doi: 10.1093/toxsci/kfj062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Stephen RL, Gustafsson MC, Jarvis M, Tatoud R, Marshall BR, Knight D, Ehrenborg E, Harris AL, Wolf CR, Palmer CN. Activation of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor delta stimulates the proliferation of human breast and prostate cancer cell lines. Cancer Res. 2004;64:3162–3170. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.can-03-2760. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Aung CS, Faddy HM, Lister EJ, Monteith GR, Roberts-Thomson SJ. Isoform specific changes in PPARα and β in colon and breast cancer with differentiation. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2006;340:656–660. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2005.12.061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Girroir EE, Hollingshead HE, Billin AN, Willson TM, Robertson GP, Sharma AK, Amin S, Gonzalez FJ, Peters JM. Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-β/δ (PPARβ/δ) ligands inhibit growth of UACC903 and MCF7 human cancer cell lines. Toxicology. 2008;243:236–243. doi: 10.1016/j.tox.2007.10.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ghosh M, Ai Y, Narko K, Wang Z, Peters JM, Hla T. PPARδ is pro-tumorigenic in a mouse model of COX-2-induced mammary cancer. Prostaglandins Other Lipid Mediat. 2009;88:97–100. doi: 10.1016/j.prostaglandins.2008.11.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Yin Y, Russell RG, Dettin LE, Bai R, Wei ZL, Kozikowski AP, Kopleovich L, Glazer RI. Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor delta and gamma agonists differentially alter tumor differentiation and progression during mammary carcinogenesis. Cancer Res. 2005;65:3950–3957. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-3990. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Chang SH, Liu CH, Wu MT, Hla T. Regulation of vascular endothelial cell growth factor expression in mouse mammary tumor cells by the EP2 subtype of the prostaglandin E2 receptor. Prostaglandins Other Lipid Mediat. 2005;76:48–58. doi: 10.1016/j.prostaglandins.2004.12.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Girroir EE, Hollingshead HE, He P, Zhu B, Perdew GH, Peters JM. Quantitative expression patterns of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-β/δ (PPARβ/δ) protein in mice. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2008;371:456–461. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2008.04.086. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.He P, Borland MG, Zhu B, Sharma AK, Amin S, El-Bayoumy K, Gonzalez FJ, Peters JM. Effect of ligand activation of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-β/δ (PPARβ/δ) in human lung cancer cell lines. Toxicology. 2008;254:112–117. doi: 10.1016/j.tox.2008.09.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Franken NA, Rodermond HM, Stap J, Haveman J, van Bree C. Clonogenic assay of cells in vitro. Nature protocols. 2006;1:2315–2319. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2006.339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.De Wever O, Mareel M. Role of tissue stroma in cancer cell invasion. The Journal of pathology. 2003;200:429–447. doi: 10.1002/path.1398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Chang SH, Liu CH, Conway R, Han DK, Nithipatikom K, Trifan OC, Lane TF, Hla T. Role of prostaglandin E2-dependent angiogenic switch in cyclooxygenase 2-induced breast cancer progression. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004;101:591–596. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2535911100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sznaidman ML, Haffner CD, Maloney PR, Fivush A, Chao E, Goreham D, Sierra ML, LeGrumelec C, Xu HE, Montana VG, Lambert MH, Willson TM, Oliver WR, Sternbach DD. Novel selective small molecule agonists for peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor δ (PPARδ)-synthesis and biological activity. Bioorg Med Chem Lett. 2003;13:1517–1521. doi: 10.1016/s0960-894x(03)00207-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kim DJ, Bility MT, Billin AN, Willson TM, Gonzalez FJ, Peters JM. PPARβ/δ selectively induces differentiation and inhibits cell proliferation. Cell Death Differ. 2006;13:53–60. doi: 10.1038/sj.cdd.4401713. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Foreman JE, Sorg JM, McGinnis KS, Rigas B, Williams JL, Clapper ML, Gonzales FJ, Peters JM. Regulation of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-β/δ by the APC/β-CATENIN pathway and nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs. Molecular Carcinogenesis. 2009 doi: 10.1002/mc.20546. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.He TC, Chan TA, Vogelstein B, Kinzler KW. PPARδ is an APC-regulated target of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs. Cell. 1999;99:335–345. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81664-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Narko K, Zweifel B, Trifan O, Ristimaki A, Lane TF, Hla T. COX-2 inhibitors and genetic background reduce mammary tumorigenesis in cyclooxygenase-2 transgenic mice. Prostaglandins Other Lipid Mediat. 2005;76:86–94. doi: 10.1016/j.prostaglandins.2005.01.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Müller-Brüsselbach S, Kömhoff M, Rieck M, Meissner W, Kaddatz K, Adamkiewicz J, Keil B, Klose KJ, Moll R, Burdick AD, Peters JM, Müller R. Deregulation of tumor angiogenesis and blockade of tumor growth in PPARβ-deficient mice. Embo J. 2007;26:3686–3698. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7601803. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]