Abstract

Summary: DNA copy number alterations (CNA) frequently underlie gene expression changes by increasing or decreasing gene dosage. However, only a subset of genes with altered dosage exhibit concordant changes in gene expression. This subset is likely to be enriched for oncogenes and tumor suppressor genes, and can be identified by integrating these two layers of genome-scale data. We introduce DNA/RNA-Integrator (DR-Integrator), a statistical software tool to perform integrative analyses on paired DNA copy number and gene expression data. DR-Integrator identifies genes with significant correlations between DNA copy number and gene expression, and implements a supervised analysis that captures genes with significant alterations in both DNA copy number and gene expression between two sample classes.

Availability: DR-Integrator is freely available for non-commercial use from the Pollack Lab at http://pollacklab.stanford.edu/ and can be downloaded as a plug-in application to Microsoft Excel and as a package for the R statistical computing environment. The R package is available under the name ‘DRI’ at http://cran.r-project.org/. An example analysis using DR-Integrator is included as supplemental material.

Contact: ksalari@stanford.edu; pollack1@stanford.edu

Supplementary information: Supplementary data are available at Bioinformatics online.

1 INTRODUCTION

DNA microarray technology has been leveraged to make genome-scale measurements across multiple layers of cellular molecules, e.g. gene expression (Schena et al., 1995), DNA copy number (Pinkel et al., 1998; Pollack et al., 1999), protein expression (Haab et al., 2001) and microRNA expression (Calin et al., 2004), among others. While each data type alone provides a unique snapshot of a cell's state, an integrative analysis of two or more complementary data types can reveal much more than the sum of its parts. DNA copy number alterations (CNAs) represent one data layer extensively measured among many tumor types using array-based comparative genomic hybridization (array CGH). CNAs lead to the amplification and deletion of oncogenes and tumor-suppressor genes (TSGs), respectively, and thereby play a critical role in tumorigenesis. While delineating CNAs across many samples facilitates the identification of oncogenes (in regions of recurrent amplification) and TSGs (in regions of recurrent deletion), cumulatively such genetic changes often span a substantial proportion of the genome, thereby obfuscating the distinction between ‘driver’ cancer genes selected for by a genetic event and nearby ‘passenger’ genes incidentally co-amplified or deleted. Similarly, when comparing cancer cells to normal cells, thousands of genes are often differentially expressed, rendering discrimination of the most salient, primary changes from correlated, downstream changes difficult.

One useful approach to aid cancer gene discovery is to integrate DNA copy number and gene expression profiles (Adler et al., 2006; Garraway et al., 2005; Hyman et al., 2002; Pollack et al., 2002). Tumors often harbor CNAs altering the gene dosage of hundreds or thousands of genes. However, due to tissue-specific expression or feedback regulation, among other mechanisms, expression levels of many of these genes may remain unaltered. Because the effects of CNAs are mediated by changes in gene expression, the subset of genes exhibiting concordant changes in both DNA copy number and gene expression (e.g. amplified and over-expressed genes) are likely to be enriched for candidate oncogenes and TSGs.

While several software tools and statistical methods have been developed to analyze DNA copy number data (Beroukhim et al., 2007; Olshen et al., 2004; Tibshirani and Wang, 2008) or gene expression data (Reich et al., 2006; Subramanian et al., 2005; Tusher et al., 2001) separately, few methods have been developed for their integration (Berger et al., 2006; Carrasco et al., 2006; Hautaniemi et al., 2004). In particular, to our knowledge there is no widely available software tool that facilitates multiple integrative analyses with a user-friendly interface. Here, we describe our development of DR-Integrator, a broadly useful package of tools to integrate array CGH and gene expression microarray data for the nomination of candidate cancer genes.

2 FEATURES

The DR-Integrator software package contains two analysis tools: DR-Correlate and DR-SAM.

2.1 Correlation analysis

DR-Correlate aims to identify genes with expression changes explained by underlying CNAs. To that end, this tool performs an analysis to identify all genes with statistically significant correlations between their DNA copy number and gene expression levels. Three options for the statistic to measure correlation are implemented: (i) Pearson's correlation; (ii) Spearman's rank correlation; and (iii) an ‘extremes’ t-test. For Pearson's and Spearman's correlations, the respective correlation coefficient is computed for each gene. For the extremes t-test, a modified Student's t-test (Tusher et al., 2001) is computed for each gene, comparing gene expression levels of samples comprising the lowest and the highest quantiles with respect to DNA copy number. In other words, for each gene the samples are rank-ordered by DNA copy number and samples below the lowest quantile and above the highest quantile form two groups whose gene expression is compared with a modified t-test. The percentile cutoff defining the two quantile groups is user-adjustable.

2.2 Two-class supervised learning analysis

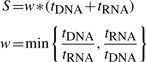

DNA/RNA-Significance Analysis of Microarrays (DR-SAM) performs a supervised analysis to identify genes with statistically significant differences in both DNA copy number and gene expression between different classes (e.g. tumor subtype-A versus tumor subtype-B). The goal of this analysis is to identify genetic differences (CNAs) that mediate gene expression differences between two groups of interest. DR-SAM implements a modified Student's t-test to generate for each gene two t-scores assessing differences in DNA copy number (tDNA) and differences in gene expression (tRNA). A final score (S) is computed by first summing the copy number t-score and gene expression t-score, and then weighting the sum by the ratio of the two t-scores (0 ≤ w ≤ 1). The weight is applied to favor genes with strong differences in both DNA copy number and gene expression between the two classes. That is, a gene with statistically equal differences in copy number and in gene expression (i.e. tDNA = tRNA) will have a weight of 1, while genes with unbalanced contributions from copy number and expression will have a weight less than 1, resulting in a lower score:

|

(1) |

2.3 False discovery rate estimation

To account for multiple hypothesis testing, both DR-Correlate and DR-SAM calculate a measure of statistical significance called the q-value, which is based on the false discovery rate (FDR). This is achieved by randomly permuting the sample labels a large number of times (user-defined; default: 1000 times) to disrupt the correlations between the paired DNA copy number and gene expression measurements. For each random permutation of the data, a test score is computed for every gene. To calculate a gene-specific q-value, each observed score is compared to the distribution of random scores and the FDR is estimated as previously described (Storey and Tibshirani, 2003).

2.4 Additional features

DR-Integrator performs several preprocessing steps including smoothing of copy number data, calling significant copy number alterations with the Fused Lasso method (Tibshirani and Wang, 2008), and merging DNA/RNA datasets from different platforms to allow for integrative analyses. DR-Integrator also allows the user to specify the FDR cutoff for an analysis and generate DNA/RNA ‘heatmaps’ for genes achieving statistical significance. Automatic imputation of missing expression data, using the nearest neighbor algorithm, is also performed. Finally, we note that DR-Integrator is not limited to the analysis of DNA copy number and gene expression data, but can be used to integrate any paired data types where a 1-to-1 mapping between measured elements can be made. An example analysis is shown on a dataset of DNA copy number and gene expression profiles of 50 breast cancer cell lines (Supplementary Figure S1).

3 IMPLEMENTATION

DR-Integrator has been developed in R and Microsoft Visual Basic v6.5, and runs as a plug-in to Microsoft Excel under the Windows operating system (2000/XP/Vista). With the use of Windows emulators, DR-Integrator can also be run on Mac OS X, Linux and Unix-based operating systems. The statistical methods can also be applied natively in the R interpreter on any of the above platforms.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors would like to thank members of the Pollack Lab for helpful discussions, and Adrienne Pollack for the DR-Integrator logo art.

Funding: National Institutes of Health (CA97139 and CA112016 to J.R.P.); Paul & Daisy Soros Foundation (to K.S.); Medical Scientist Training Program (to K.S.).

Conflict of Interest: none declared.

REFERENCES

- Adler AS, et al. Genetic regulators of large-scale transcriptional signatures in cancer. Nat. Genet. 2006;38:421–430. doi: 10.1038/ng1752. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berger JA, et al. Jointly analyzing gene expression and copy number data in breast cancer using data reduction models. IEEE/ACM Trans. Comput. Biol. Bioinform. 2006;3:2–16. doi: 10.1109/TCBB.2006.10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beroukhim R, et al. Assessing the significance of chromosomal aberrations in cancer: methodology and application to glioma. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2007;104:20007–20012. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0710052104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calin GA, et al. MicroRNA profiling reveals distinct signatures in B cell chronic lymphocytic leukemias. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2004;101:11755–11760. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0404432101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carrasco DR, et al. High-resolution genomic profiles define distinct clinico-pathogenetic subgroups of multiple myeloma patients. Cancer Cell. 2006;9:313–325. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2006.03.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garraway LA, et al. Integrative genomic analyses identify MITF as a lineage survival oncogene amplified in malignant melanoma. Nature. 2005;436:117–122. doi: 10.1038/nature03664. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haab BB, et al. Protein microarrays for highly parallel detection and quantitation of specific proteins and antibodies in complex solutions. Genome Biol. 2001;2 doi: 10.1186/gb-2001-2-2-research0004. RESEARCH0004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hautaniemi S, et al. A strategy for identifying putative causes of gene expression variation in human cancers. J. Franklin Inst. 2004;341:77–88. [Google Scholar]

- Hyman E, et al. Impact of DNA amplification on gene expression patterns in breast cancer. Cancer Res. 2002;62:6240–6245. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olshen AB, et al. Circular binary segmentation for the analysis of array-based DNA copy number data. Biostatistics. 2004;5:557–572. doi: 10.1093/biostatistics/kxh008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pinkel D, et al. High resolution analysis of DNA copy number variation using comparative genomic hybridization to microarrays. Nat. Genet. 1998;20:207–211. doi: 10.1038/2524. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pollack JR, et al. Genome-wide analysis of DNA copy-number changes using cDNA microarrays. Nat. Genet. 1999;23:41–46. doi: 10.1038/12640. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pollack JR, et al. Microarray analysis reveals a major direct role of DNA copy number alteration in the transcriptional program of human breast tumors. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2002;99:12963–12968. doi: 10.1073/pnas.162471999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reich M, et al. GenePattern 2.0. Nat. Genet. 2006;38:500–501. doi: 10.1038/ng0506-500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schena M, et al. Quantitative monitoring of gene expression patterns with a complementary DNA microarray. Science. 1995;270:467–470. doi: 10.1126/science.270.5235.467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Storey JD, Tibshirani R. Statistical significance for genomewide studies. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2003;100:9440–9445. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1530509100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Subramanian A, et al. Gene set enrichment analysis: a knowledge-based approach for interpreting genome-wide expression profiles. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2005;102:15545–15550. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0506580102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tibshirani R, Wang P. Spatial smoothing and hot spot detection for CGH data using the fused lasso. Biostatistics. 2008;9:18–29. doi: 10.1093/biostatistics/kxm013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tusher VG, et al. Significance analysis of microarrays applied to the ionizing radiation response. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2001;98:5116–5121. doi: 10.1073/pnas.091062498. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.