It is a common view that emergency admissions are increasing at up to 5% per year in the United Kingdom,1 and that this unsustainable rise “threatens the future of the NHS.”2 The perceived rise in emergency admissions is invoked to explain those recurrent and well publicised crises that in turn support the view that there is a fundamental mismatch between demand and supply in health care,3 as the reported trend is held to represent a real and substantial increase in demand for hospital care.

Subjects, methods, and results

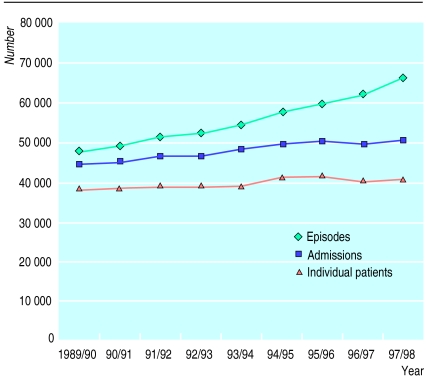

The data presented here reflect all emergency admissions in all medical and surgical specialties from 1989-90 to 1997-8 in an urban and rural population of 850 000 served by Avon Health Authority. Three trends are described: numbers of people receiving hospital treatment each year; numbers of admissions each year, where readmissions are additional events (admissions are here provider spell admissions, where transfer between hospitals within a trust remains a single admission); and episodes, or more correctly, finished consultant episodes, which constitute a continuous period under an individual consultant’s care.

Episodes of emergency treatment have risen 4.4% a year over the period, but the number of admissions has increased by only 2.0% a year (figure). The number of people receiving emergency treatment has increased only slightly, at an annual rate of 1.4%, of which an increase of some 0.6% could be expected from the increase in the numbers of older people in the population during this period. A rise of some 0.8% in emergency admission therefore remains unexplained.

Though the ratio of episodes to admissions increased from 1.06 to 1.32 over the period, the overall readmission rate, as summarised by the ratio of admissions to individuals, has remained relatively constant, rising from 1.17 to 1.22. During the period the average length of stay per emergency admission fell from 10.2 days to 8.7 days (the median fell from 3.6 to 3.1 days). The number of emergency bed days at the beginning of the period (456 382) is similar to that at the end (453 290).

Comment

This study shows that, whatever else is causing a real or perceived crisis in the NHS, an increase in the number of people requiring or demanding emergency treatment is not the explanation. The supposed rise in emergency admissions is almost entirely attributable to the increased reporting of internal transfers of patients after admission. For example, if someone with a stroke is transferred from an assessment ward to the care of a neurologist, then referred for computed tomography, and subsequently moved to a geriatric rehabilitation ward, this single admission may be recorded as three or even four episodes. Costs are attributed according to episodes, not admissions. The cost of emergency care has thus risen dramatically during a period when capacity and demand have changed little.

The main evidence to support the view that the current rise in emergency admissions may be a genuine reflection of population changes comes from the analysis of linked Scottish data for the period 1981-94.4 Our study shows how extrapolation from that period may be seriously misleading for the interpretation of more recent trends in other geographical areas. There is no doubt that many individual patients and their carers have deeply unsatisfactory experiences when seeking access to emergency care. It will be important to replicate this study in other localities to decide whether the problem in emergency care is really one of changing demand, or more a matter of the quality and accessibility of the capacity that is currently available.5

Figure.

Numbers of episodes, admissions, and individual patients, 1989-90 to 1977-8, all specialties and all ages, Avon Health Authority (population 850 000)

Paper p 155

Footnotes

Funding: None.

Competing interests: None declared.

References

- 1.Capewell S. The continuing rise in emergency admissions. BMJ. 1996;312:991–992. doi: 10.1136/bmj.312.7037.991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Blatchford O, Capewell S. Emergency medical admissions: taking stock and planning for winter. BMJ. 1997;315:1322–1323. doi: 10.1136/bmj.315.7119.1322. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Frankel SJ. Health needs, health care requirements, and the myth of infinite demand. Lancet. 1991;337:1588–1589. doi: 10.1016/0140-6736(91)93276-f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kendrick S. The pattern of increase in emergency hospital admissions in Scotland. Health Bulletin. 1996;54:169–183. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Coast J, Inglis A, Morgan K, Gray S, Kammerling M, Frankel SJ. The hospital admissions study: are there alternatives to emergency hospital admission? J Epidemiol Community Health. 1995;49:194–199. doi: 10.1136/jech.49.2.194. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]