SUMMARY

Mice lacking the proneural transcription factor Math1 (Atoh1) lack multiple neurons of the proprioceptive and arousal systems and die shortly after birth from an apparent inability to initiate respiration. We sought to determine whether Math1 was necessary for the development of hindbrain nuclei involved in respiratory rhythm generation, such as the parafacial respiratory group/retrotrapezoid nucleus (pFRG/RTN), defects in which are associated with Congenital Central Hypoventilation Syndrome (CCHS). Using a new Math1-GFP fusion allele, we traced the development of Math1-expressing pFRG/RTN and paratrigeminal neurons and found that loss of Math1 did indeed disrupt their migration and differentiation. We also identified new Math1-dependent neurons and their projections in the pre-Bötzinger complex, a structure critical for respiratory rhythmogenesis, and found that glutamatergic modulation reestablished a rhythm in the absence of Math1. This study identifies Math1-dependent neurons that are critical for perinatal breathing that may link proprioception and arousal with respiration.

INTRODUCTION

Respiration requires the coordinated effort of rhythm-generating neurons in the hindbrain, modulatory inputs, sensory feedback, and multiple muscle groups. Disruption of this network likely underlies respiratory disorders such as congenital central hypoventilation syndrome (CCHS, Ondine’s Curse) and sudden infant death syndrome (SIDS), the leading cause of post-neonatal infant mortality in the U.S. In CCHS, patients fail to increase respiration or arouse from sleep in response to increasing blood CO2 levels (Severinghaus and Mitchell, 1962). Similarly, infants who have died of SIDS appear to have been unable to arouse from sleep in response to hypoxia (Kato et al., 2003). A more complete understanding of the respiratory network in the hindbrain could provide insight into the pathogenesis of these disorders.

Respiratory rhythm-generating neurons reside within the ventral respiratory column (VRC) of the medulla. The pre-Bötzinger complex (preBötC) generates the inspiratory rhythm (Smith et al., 1991) and receives modulatory input from adjacent nuclei, including a region located around the facial motor nucleus just rostral to the preBötC. Different investigators refer to neurons in this region either as the parafacial respiratory group (pFRG) or as the retrotrapezoid nucleus (RTN). Neurons in the pFRG have been proposed to function as a pre-inspiratory or expiratory-modulating nucleus in newborns (Janczewski and Feldman, 2006; Onimaru and Homma, 2003); the RTN contains chemosensitive neurons that respond to changing CO2 levels in adults (Pearce et al., 1989; Smith et al., 1989). While it remains unclear if the pFRG and RTN neurons are the same, recent genetic studies have indicated some overlap and we will refer to them as the pFRG/RTN.

Recent studies have shown that pFRG/RTN neurons express the transcription factors paired-like homeobox 2b (Phox2b) and ladybird homeobox homolog 1 (Lbx1) (Dubreuil et al., 2008; Onimaru et al., 2008; Pagliardini et al., 2008). Mutations in Phox2b have been associated with CCHS (Amiel et al., 2003). In addition, mice with mutations in Phox2b and Lbx1, as well as in the hindbrain segmentation gene Egr2 (Krox20), show disruption of the pFRG/RTN and respiratory rhythm impairment (Dubreuil et al., 2008; Jacquin et al., 1996; Pagliardini et al., 2008; Thoby-Brisson et al., 2009). Another important gene expressed by both pFRG/RTN and some rhythmogenic preBötC neurons is the substance P receptor NK1R (Gray et al., 1999; Nattie and Li, 2002). The NK1R neurons in both nuclei are glutamatergic, expressing vesicular glutamate transporter 2 (Vglut2) (Guyenet et al., 2002; Weston et al., 2004). Excitatory glutamatergic modulation appears critical for respiratory rhythmogenesis (Greer et al., 1991; Pace et al., 2007), but the full impact of glutamatergic neurons outside the preBötC remains unclear.

The respiratory rhythm receives additional modulation from nuclei in the pons. These nuclei include the parabrachial/Kölliker-Fuse (PB/KF) nucleus and the pedunculopontine tegmental nucleus (PPTg) of the reticular activating system, which together integrate visceral and somatic sensory information to regulate arousal and sleep states (Chamberlin and Saper, 1994; Kubin and Fenik, 2004). Failure of arousal mechanisms appears to contribute to both CCHS and SIDS, and one key component of arousal involves proprioceptive stimuli. Stretching and yawning movements generate proprioceptive sensory input to help stimulate the reticular activating system and arouse the cortex (McNamara et al., 1998). Proprioception involves the cerebellum, which shows abnormalities in some children who die from SIDS, suggesting that deficits in both proprioception and arousal may contribute to respiratory dysfunction in these patients (Kato et al., 2003; Lavezzi et al., 2006).

One key player in hindbrain development is the proneural transcription factor mouse atonal homolog 1 (Math1, Atoh1). Mice lacking Math1 lose multiple components of the auditory, proprioceptive, interoceptive, and arousal systems, including many glutamatergic neurons (Ben-Arie et al., 2000; Machold and Fishell, 2005; Rose et al., 2009; Wang et al., 2005), and die shortly after birth from an apparent inability to initiate respiration. The lungs, airways, and peripheral nerves appear normal in Math1-null mice, suggesting that the problem lies in some unidentified defect in the central nervous system (Ben-Arie et al., 1997). Pinpointing the mechanism underlying their respiratory failure might shed light on the vital connections between respiration, proprioception, and arousal.

We generated a Math1-GFP fusion allele (Math1M1GFP) to identify and track hindbrain lineages displaying novel Math1 expression outside the neuroepithelium, and used a hormonally inducible Math1Cre*PR allele (Rose et al., 2009) in combination with Cre-reporters to trace the projections of Math1-dependent lineages within the hindbrain respiratory network. In conjunction with these fate-mapping approaches, we characterized the respiratory physiology in the perinatal Math1-null hindbrain to ascertain which neuromodulators affect the respiratory rhythm. We discovered that proper development of the pFRG/RTN neurons requires Math1 and determined that modulating the glutamatergic system reestablishes a respiratory rhythm in Math1-null preparations. In addition, these studies identify new candidate neurons that should be evaluated in respiratory disorders such as CCHS and SIDS.

RESULTS

Perinatal Death of Math1-Null Mice due to a Slowed Central Respiratory Rhythm

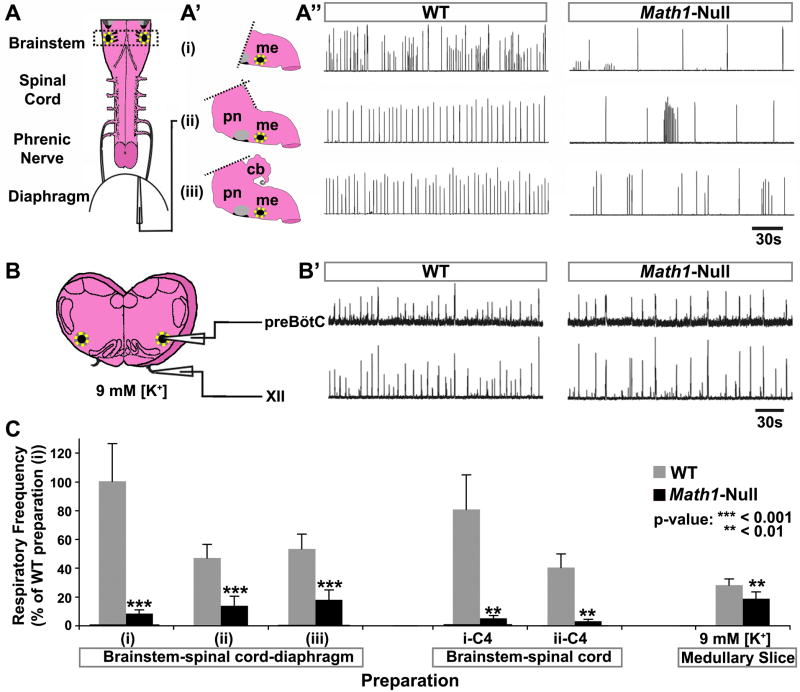

Math1-null mice take only occasional gasps without yawning or stretching, never establish patterned respiration, and become unresponsive by 30–45 minutes after delivery. To assess the centrally generated respiratory rhythmogenesis in Math1-null mice, we analyzed the respiratory rhythm via diaphragmatic electromyography (EMG) from in vitro preparations that contained the brainstem and spinal cord connected to the diaphragm via the phrenic nerve (Figure 1A, dotted yellow circle indicates the preBötC, and black region ventral to the gray facial motor nucleus indicates the pFRG/RTN). Since Math1-dependent lineages are found in the cerebellum, pons, and medulla, we compared EMG from three preparations to help define the region containing Math1 populations vital for respiration: (i) medulla alone (standard preparation), (ii) pons-medulla, and (iii) cerebellum-pons-medulla. These three preparations are depicted by the three distinct hindbrain models (Figure 1A′; see Table S1 for frequency, sample size, and coefficients of variation). Compared to WT, all three Math1-null preparations (i–iii, right column) generated slower and more variable respiratory rhythms, retaining primarily large-amplitude discharges with long periods of inactivity interrupted by short bursts (Figure 1A″ and quantified in Figure 1C).

Figure 1. Math1-Null Mice Die after Birth because of Too-Slow Central Respiratory Rhythm.

(A) Schematic of the standard brainstem-spinal cord-diaphragm (BSD) preparation used for respiratory physiology (includes only the medullary portion of the brainstem). (A′) Schematics depicting three variations of the BSD preparation in which different portions of the brainstem were included: (i) medulla only, (ii) pons and medulla, and (iii) cerebellum, pons, and medulla. (A″) Rectified and integrated suction electrode recordings from the diaphragm muscle EMG in the three BSD preparations from E18.5 WT mice (left column) and Math1-null mice (right column). The rhythm was significantly slower and more irregular in all Math1-null preparations. Yellow dotted circle on each schematic indicates the preBötC, while the black region ventral to the facial nucleus (gray circle) represents the pFRG/RTN.

(B) Schematic of medullary slice preparation containing the preBötC (from the region indicated by the dashed rectangle in (A)). (B′) Rectified and integrated suction electrode recordings from the preBötC (top) and XII motoneuron pool (bottom) of WT (left) and Math1-null (right) slice preparations (in 9mM [K+]). The frequency was again slower in Math1-null preparations but was more stable than in the BSD preparations.

(C) Population data of respiratory frequency from WT (gray) and Math1-null (black) mice for each BSD preparation (i–iii) depicted in (A), for recordings directly from C4 in these preparations after removal of the diaphragm (i-C4: medulla only, ii-C4: pons and medulla), and for the medullary slice preparations. Data was normalized to that of WT preparation (i) for ease of comparison. P-values indicate a significant difference between Math1-null and WT tissue within each preparation. See Table S1 for frequency, sample size, and statistical analyses. Abbreviations: cerebellum (cb), hypoglossal motor nucleus (XII), medulla (me), pons (pn), pre-Bötzinger complex (preBötC).

The Math1-null rhythm remained significantly depressed when recorded directly from either the C4 spinal cord or hypoglossal cranial roots (i.e. brainstem-spinal cord preparation without diaphragm), indicating that the deficit is not at the neuromuscular junction (Figure 1C). Medullary slice preparations containing the preBötC rhythmogenesis center (depicted in Figure 1B) also showed a slower rhythm in the Math1-null preparation (Figure 1B′). These results establish that Math1-null mice die from severe central apnea and suggest that the limiting deficit in respiratory rhythmogenesis lies within the medulla.

Novel Paramotor Math1 Expression Identifies the Developing pFRG/RTN Neurons

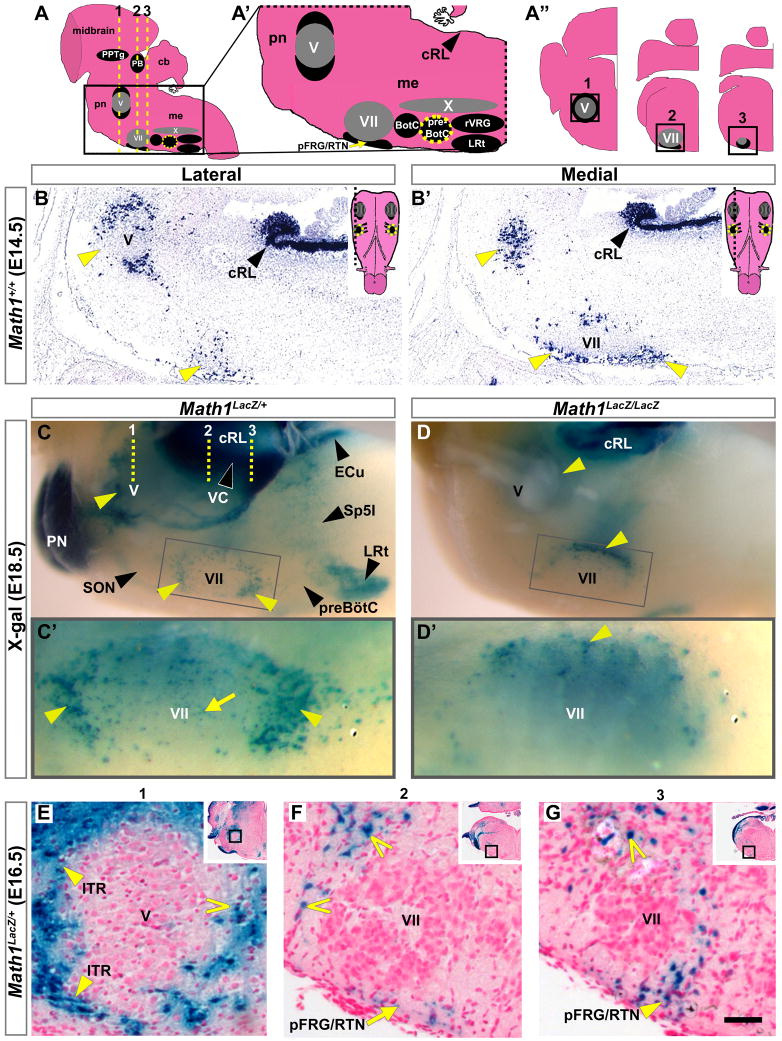

We next sought to identify the cellular basis for the respiratory deficit in Math1-null mice. Math1 is expressed during development in the rhombic lip, the dorsal-most hindbrain neuroepithelium, from which Math1-dependent neurons migrate to populate various hindbrain nuclei (Machold and Fishell, 2005; Rose et al., 2009;Wang et al., 2005). Only one other region is known to express Math1 in the developing hindbrain: the external granule layer (EGL) of the cerebellum, which is contiguous with the rhombic lip (Ben-Arie et al., 1997). It is unknown whether Math1 expression outside the rhombic lip and EGL plays a role in neuronal development. Analysis of Math1 mRNA on E14.5 sagittal sections (region depicted in Figure 2A) uncovered novel expression domains around the trigeminal (V) and facial (VII) motor nuclei (Figures 2B and 2B′, yellow arrowheads). This paramotor Math1 mRNA expression was present by E11.5 and disappeared by birth (data not shown).

Figure 2. Math1 Expression in Paramotor Regions.

(A–A″) Sagittal model of the hindbrain, with midbrain visible at top, showing the PB and PPTg in the rostral pons, the motor nuclei V, VII, and X (all gray), and the ventral respiratory nuclei in the medulla (black). (A′) Enlarged model of the caudal pons and medulla, from boxed region in (A). (A″) Model of serial coronal hemisections from the levels of the V and VII motor nuclei, corresponding to dashed yellow lines (1–3) in (A). Yellow dotted circle indicates the preBötC. (B,B′) Novel Math1 mRNA expression surrounding (B) V and (B′) VII on adjacent sagittal sections from the region depicted in (A′) from WT E14.5 hindbrain (yellow arrowheads). Insets show models of the ventral surface of the hindbrain with dashed lines indicating the section levels of the corresponding lateral and medial sections.

(C–D′) Whole mount LacZ expression at E18.5 in the medulla and caudal pons in (C) Math1LacZ/+ and (D) Math1LacZ/LacZ null mice shown in side views. Yellow arrowheads indicate Math1LacZ populations around V and VII that approximated the novel Math1 expression in (B,B′) and persisted in the Math1-null hindbrain, though in different distributions. Gray boxes indicate the region of the ventral medullary surface magnified below: (C′) parafacial LacZ expression clustered at the poles (yellow arrowheads) and along the ventral surface of VII (yellow arrow) in Math1LacZ/+ mice, and (D′) primarily restricted to the lateral edge (up) of VII in the Math1LacZ/LacZ null hindbrain (yellow arrowhead). The dotted yellow lines (1–3) on (C) correspond to those depicted on the schematic in (A).

(E–G) Coronal sections from an E16.5 Math1LacZ/+ hindbrain at the approximate levels indicated by dotted yellow lines (1–3) in (C), showing novel populations surrounding V (including the lateral ITR, yellow arrowheads on E), and along the ventral surface (yellow arrow on F) and caudal pole (yellow arrowhead on G) of VII in the pFRG/RTN region, as well as dorsolateral to VII (open arrowheads on F and G). Positions of the depicted regions are indicated by boxes on both the insets in each panel and on corresponding models in A″.

Rostral is to the left in (A,A′) and (B–D′), and lateral is to the left in (A″) and (E–G). Abbreviations: caudal rhombic lip (cRL), cerebellum (cb), medulla (me), pons (pn), and the ambiguus (X), Bötzinger complex (BötC), external cuneate (ECu), facial motor (VII), interpolar division of the spinal trigeminal (Sp5I), intertrigeminal region (ITR), lateral reticular (LRt), parabrachial (PB), parafacial respiratory group/retrotrapezoid (pFRG/RTN), pontine (PN), pedunculopontine tegmental (PPTg), pre-Bötzinger complex (preBötC), rostral ventral respiratory group (rVRG), trigeminal motor (V), and ventral cochlear (VC) nuclei. Scale bar, 275 μm (B,B′), 350 μm (C,D), 100 μm (C′,D′), 45 μm (E–G), 800 μm (insets, E–G).

In Math1LacZ/LacZ null hindbrains, in which Math1 is replaced by LacZ (Ben-Arie et al., 2000), rhombic lip-derived populations were lost as previously reported (Ben-Arie et al., 1997; Rose et al., 2009; Wang et al., 2005), but LacZ expression persisted around V and VII, similar to the rhombic lip (compare Figures 2C and 2D, yellow arrowheads). While the Math1LacZ/+ medulla showed clusters of LacZ cells at the rostral and caudal poles of VII and scattered along its ventral surface, labeled cells in the Math1LacZ/LacZ medulla were predominantly at the lateral edge of VII (compare Figures 2C′ and 2D′, magnifications). Coronal sections through an E16.5 Math1LacZ/+ hindbrain (approximate levels 1–3 on Figures 2A and 2C) revealed that some of these LacZ populations resided in the intertrigeminal region (Figure 2E, yellow arrowheads) and pFRG/RTN (Figures 2F, yellow arrow, and 2G, yellow arrowhead) and were contiguous with additional labeled cells around each motor nucleus (open yellow arrowheads). These observations describe the first persistent Math1 hindbrain expression observed outside the rhombic lip and EGL and identify a distinct population of cells that do not require Math1 to exit the neuroepithelium.

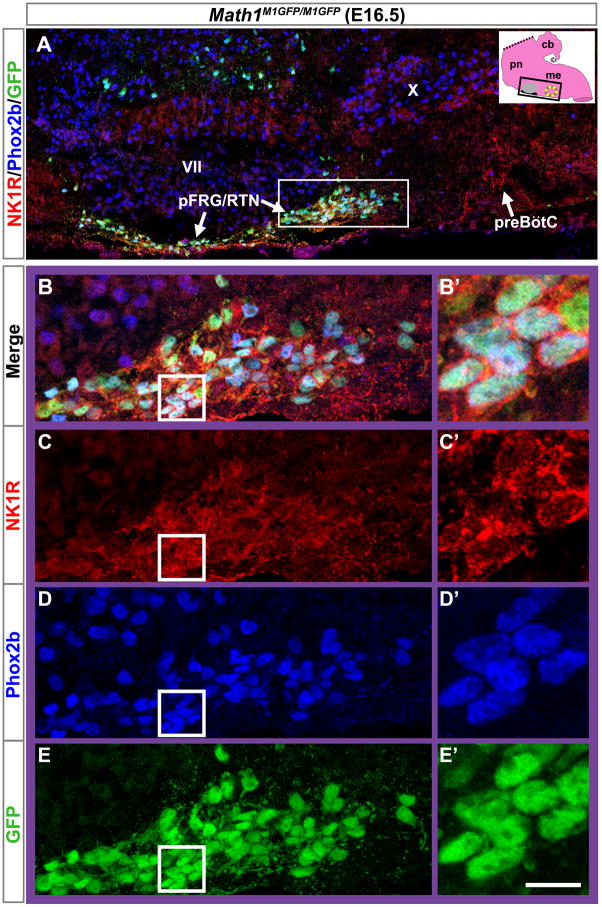

Because LacZ persists longer than the Math1 protein, it cannot distinguish between cells actively expressing Math1 and those that recently stopped (Wang et al., 2005). We therefore targeted a Math1-EGFP fusion allele (M1GFP) into the Math1 genomic locus to generate homozygous viable Math1M1GFP/M1GFP mice (Figure 3). The resulting Math1EGFP fusion protein could then be identified with antibodies to GFP. Using the Math1M1GFP allele, we assessed whether parafacial Math1 expression labeled pFRG/RTN neurons, which are known to express Phox2b, Lbx1, and NK1R. At E16.5, Math1 co-labeled with Phox2b and NK1R in the pFRG/RTN (Figures 4A–4E), but not with tyrosine hydroxylase (data not shown), consistent with previous studies of the pFRG/RTN.

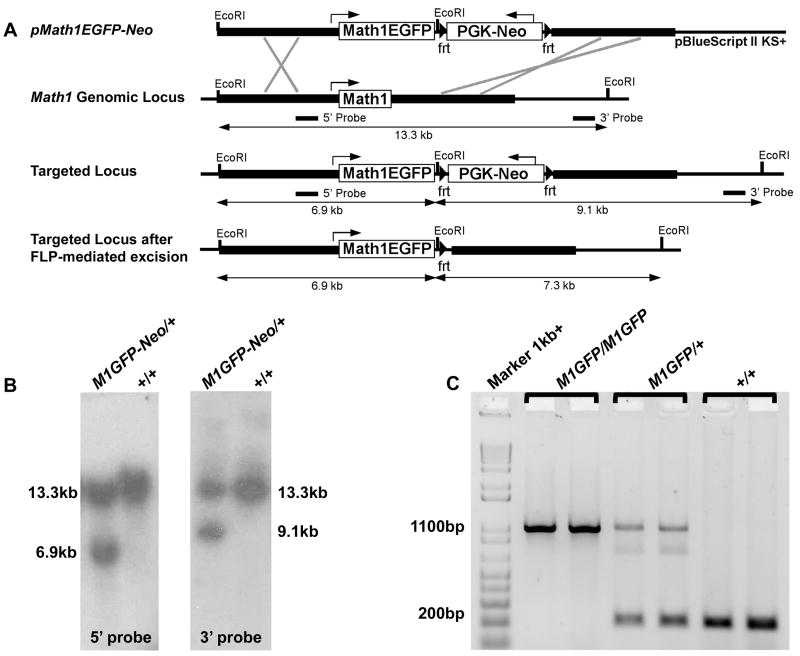

Figure 3. Generation of a Targeted Math1-EGFP Fusion Allele.

(A) Targeting schematic. The EGFP coding sequence was fused to the 3′ end of the Math1 coding sequence with a short linker representing the peptide -DILDPPVAT-, and together with an frt-bounded PGK-Neo selection cassette, was placed between intact Math1 5′ and 3′ homology arms (thick lines) (pMath1EGFP-Neo). This construct was targeted to the Math1 genomic locus, followed by in vivo removal of the PGK-Neo as depicted.

(B) EcoRI digested genomic DNA from mice carrying the targeted allele showed the expected band sizes for the Math1EGFP-Neo fusion allele (Math1M1GFP-Neo) when probed with 5′ (6.9 kb) and 3′ (9.1 kb) probes.

(C) The final Math1M1EGFP allele was generated by crossing the Math1M1EGFP-Neo mice to ROSAFlp/Flp mice for in vivo Flp-mediated excision of PGK-Neo. PCR genotyping of viable homozygous Math1M1GFP/M1GFP (1.1 kb), Math1M1GFP/+ (1.1kb+200bp), and WT (200 bp) mice is shown.

Figure 4. Parafacial Math1 Neurons Contribute to the pFRG/RTN.

(A) Magnification of the ventral respiratory column from an E16.5 Math1M1GFP/M1GFP hindbrain, as indicated by the black rectangle on the inset model of the hindbrain (black ventral region is pFRG/RTN while yellow circle indicates preBötC), showing NK1R (red), Phox2b (blue), and Math1EGFP (green) expression. NK1R labeled both the pFRG/RTN and preBötC neurons. (B–E) Magnified pFRG/RTN neurons from the caudal pole of VII (solid white rectangle in (A)) showing co-localization of Math1EGFP with Phox2b and NK1R. (B) shows the 3 markers merged while (C–E) shows them separately. Further magnification from the white boxes in (B–E) is shown to the right of each panel in (B′–E′). NK1R labeled cell membranes while Phox2b localized to the nucleus and Math1EGFP showed both nuclear and cytoplasmic staining (labeling processes in addition to the cell somas).

Rostral is to the left in all panels.

Abbreviations: pre-Bötinger complex (preBötC), facial motor (VII), ambiguus (X), and parafacial respiratory group/retrotrapezoid (pFRG/RTN) nuclei. Scale bar, 120 μm (A), 35 μm (B–E), 10 μm (B′–E′).

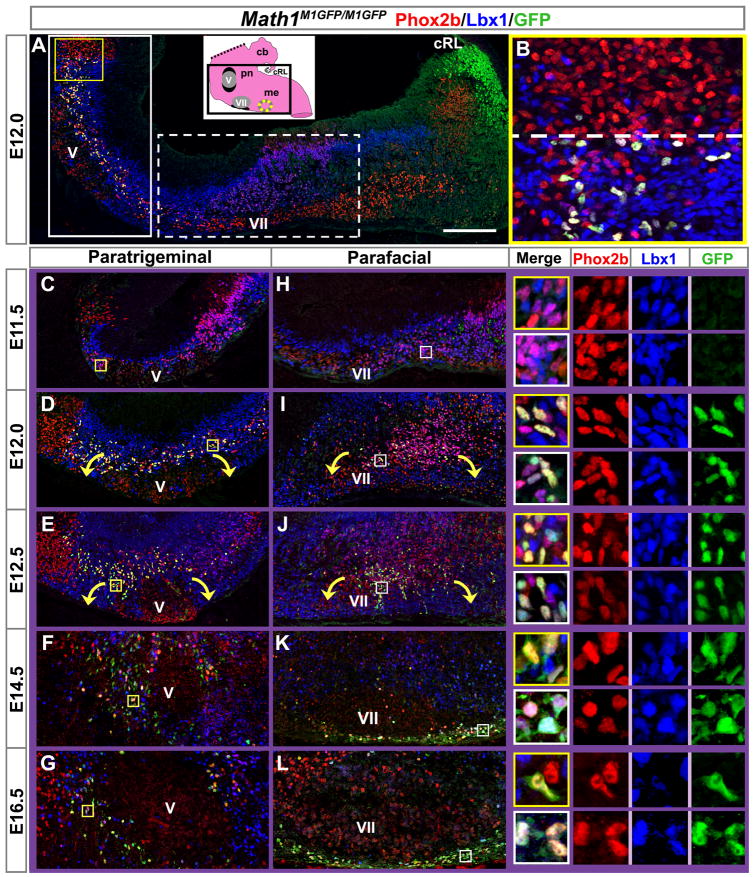

We next sought to characterize the early development of pFRG/RTN neurons. Paramotor expression of Math1 protein was first detected at E12.0 in cells co-expressing both Phox2b and Lbx1 (Figure 5A, yellow/white cells), whereas Math1 lineages exiting the caudal rhombic lip (cRL) expressed neither of these genes (Figure 5A, green cells). The rostral extent of Math1 paramotor expression coincided with that of Lbx1 in the pons (Figure 5B, dotted line). Twelve hours earlier, at E11.5, no paramotor Math1 protein expression was detected, although many cells co-expressed Phox2b/Lbx1 (Figures 5C and 5H, purple cells in corresponding yellow and white boxed magnifications shown at right). From E12.0 to E16.5, a subset of the paramotor Phox2b/Lbx1 neurons co-expressed Math1 and appeared to migrate around the motor nuclei, creating paratrigeminal and parafacial arrangements of triple-labeled neurons (Figures 5D–5G and 5I–5L). (Note: images of paratrigeminal regions were rotated ninety degrees to align the ventral surfaces of the developing pons and medulla.)

Figure 5. Development of the Paramotor Math1-Expressing Neurons.

(A) Sagittal section from an E12.5 Math1M1GFP/M1GFP hindbrain (approximately corresponding to the boxed region on the inset model of a P0 hindbrain), showing co-expression of Phox2b (red) and Lbx1 (blue) with Math1EGFP (green). Triple expression is seen around the trigeminal motor nucleus (yellow/white cells), while Math1EGFP by itself is present in the cRL (green cells). (B) Magnification of rostral-most Math1EGFP expression (from yellow box in A), demonstrating correlation with the rostral extent of Lbx1 expression (dashed line).

(C–G) Paratrigeminal and (H–L) parafacial regions magnified from Math1M1GFP/M1GFP sagittal sections as indicated by solid and dotted white boxes in (A), respectively, from E11.5 to E16.5, similarly stained for Phox2b, Lbx1, and Math1EGFP. Paratrigeminal regions are rotated 90° counterclockwise due to the bend in the hindbrain such that the true ventral surface of the pons is facing down, parallel to the ventral surface of the medulla. Magnifications of co-labeling at each time point are shown at the right, from corresponding yellow and white boxes on (C–L), with the upper yellow box at each time point showing paratrigeminal cells and the lower white box showing parafacial cells. The three markers are shown both overlaid (in the outlined boxes) and individually to the right of each merged image.

Rostral is to the left in A, B, and H–L. Dorsal is to the left in (C–G).

Abbreviations: caudal rhombic lip (cRL), cerebellum (cb), medulla (me), pons (pn), and the trigeminal motor (V) and facial motor (VII) nuclei. Scale bar, 160 μm (A), 37 μm (B), 150 μm (C–L), 30 μm (C–L insets).

In summary, the new Math1M1GFP allele provided the first clear antibody labeling of Math1 protein in the developing mouse hindbrain. This immunolabeling identified the pFRG/RTN neurons and a distinct group of paratrigeminal cells, and allowed us to track the development of these lineages.

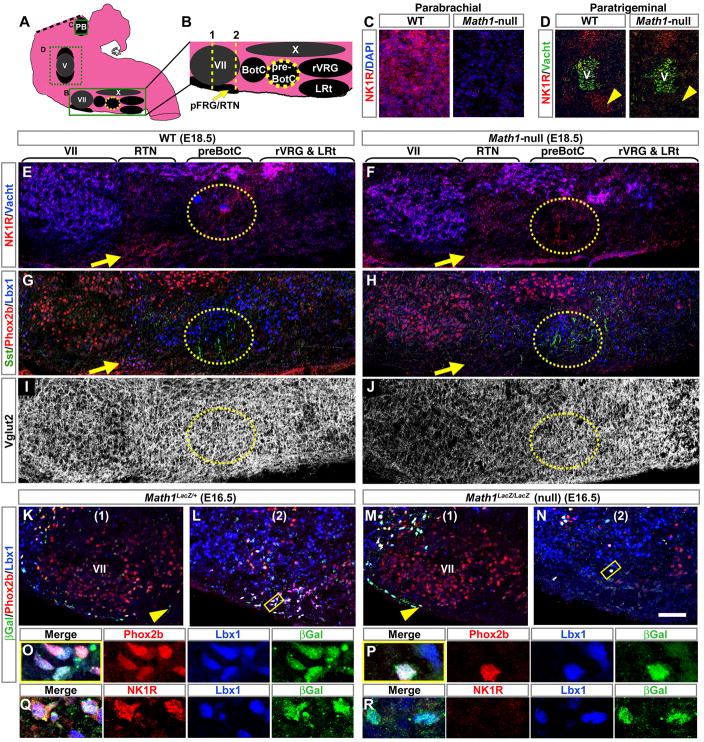

NK1R Neurons of the pFRG/RTN, Paratrigeminal, and Parabrachial Nuclei Require Math1

In addition to the pFRG/RTN, NK1R labels the preBötC, paratrigeminal region, and parabrachial nucleus, all important for breathing (positions noted in Figures 6A and 6B). To assess whether Math1 is required for proper development of these nuclei, we compared the NK1R expression in WT and Math1-null hindbrains at E18.5 and noted loss of NK1R in the parabrachial (Figure 6C), ventral paratrigeminal (Figure 6D), and pFRG/RTN nuclei (Figures 6E and 6F, yellow arrow). The majority of pFRG/RTN Phox2b and Lbx1 expression was similarly lost (Figures 6G and 6H, yellow arrow). In contrast, the preBötC continued to express NK1R (Figures 6E and 6F, yellow circle), as well as somatostatin, another marker of preBötC neurons (Figures 6G and 6H, yellow circle). Math1-null mice also had decreased Vglut2 glutamatergic projections through much of the rostral medulla and pons, including the parafacial region, but retained extensive Vglut2 projections in the preBötC and the rostral ventral respiratory group (rVRG), which projects rhythm output to phrenic motor neurons in the spinal cord (Figures 6I and 6J). These remaining Vglut2 processes may arise in part from the spared preBötC neurons, some of which are known to be synaptically coupled and glutamatergic (Guyenet et al., 2002; Pace and Del Negro, 2008). Vglut1 projections were also lost just rostral to VII in a region primarily devoted to hearing (data not shown). Thus, although several respiratory rhythm-modulating neurons are disrupted in the Math1-null hindbrain, the preBötC rhythmogenic neurons are preserved and retain many excitatory glutamatergic processes in their vicinity.

Figure 6. NK1R-Expressing Neurons of the Parafacial Respiratory Group/Retrotrapezoid, Paratrigeminal, and Parabrachial Nuclei Require Math1.

(A) Sagittal model of the hindbrain showing the PB, motor nuclei V, VII, and X (all gray), and the ventral respiratory nuclei (black).

(B) Sagittal model of ventral medullary nuclei magnified from rectangle in (A).

(C–D) Magnified regions from E18.5 WT and Math1-null hindbrains corresponding to the upper and middle dashed boxes in (A), and showing loss of NK1R (red) in the (C) parabrachial nucleus and (D) ventral paratrigeminal region in the Math1-null hindbrain (V is labeled by Vacht, green).

(E–J) Magnified regions from E18.5 (E–I) WT and (F–J) Math1-null hindbrains corresponding to the model in (B) and labeled with (E,F) Vacht (blue) and NK1R (red), (G,H) Sst (green), Phox2b (red), and Lbx1 (blue), and (I,J) Vglut2 (white). Horizontal brackets indicate approximate rostral-caudal extent of nuclei such as the RTN (yellow arrows) and preBötC (yellow dotted ovals). NK1R and Phox2b were lost from the RTN in the Math1-null while NK1R and Sst were retained in the preBötC (compare (E) to (F) and (G) to (H)). Vglut2 was decreased in the Math1-null (compare (I) to (J)).

(K–N) Coronal sections through the facial nucleus of E16.5 Math1LacZ/+ and Math1LacZ/LacZ null hindbrains at approximate levels 1 and 2 indicated in (B), showing expression of Phox2b (red), Lbx1 (blue), and βgal (LacZ protein, green). Ventral gal cells (yellow arrowheads) were more laterally restricted in the Math1-null hindbrain (compare (K) to (M)) and almost absent from the caudal pFRG/RTN (compare (L) to (N)).

(O,P) Magnifications from the yellow boxed regions in (L) and (N) show co-expression of gal with Phox2b and Lbx1 in both the (O) Math1LacZ/+ and (P) Math1LacZ/LacZ null hindbrains.

(Q,R) Magnifications from adjacent sections to (O,P) showing loss of NK1R (red) co-expression in the misplaced pFRG/RTN neurons of the Math1-null hindbrain (compare Q to R).

Rostral is to the left in (A–J) and lateral is to the left in (K–R). Note that unlike GFP, gal forms aggregates, which appear as green puncta in (K–R).

Abbreviations: ambiguus (X), Bötzinger complex (BötC), facial motor (VII), lateral reticular (LRt), parafacial respiratory group/retrotrapezoid (pFRG/RTN), pre-Bötzinger complex (preBötC), rostral ventral respiratory group (rVRG), and the trigeminal motor (V) nuclei. Scale bar, 130 μm (C), 330 μm (D), 180 μm (E–J), 45 μm (K–N), 8 μm (O–R).

We used the Math1LacZ null allele to assess the fate of pFRG/RTN neurons, labeled by LacZ protein (βGal), in Math1-null mice. Comparison of E16.5 Math1LacZ/+ and Math1LacZ/LacZ hindbrains at positions (1) and (2) indicated in Figure 6B reveals that in the absence of Math1, Gal cells extended only partway along the ventral surface of VII (Figures 6K and 6M, yellow arrowhead), clustering more dorsolateral to VII, and were virtually absent from the caudal pole of VII (Figures 6L and 6N). Although the misplaced pFRG/RTN neurons continued to express Phox2b and Lbx1 in Math-null mice (Figures 6O and 6P), they no longer expressed NK1R (Figures 6Q and 6R). Math1 is thus required for both proper migration and NK1R expression in developing pFRG/RTN neurons.

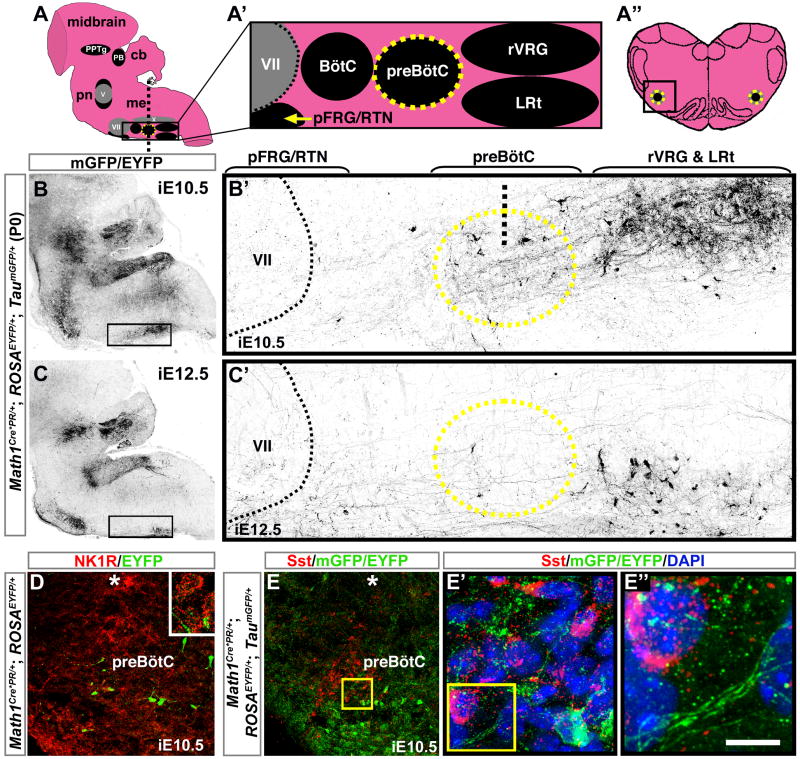

Early Math1-Dependent Lineages Project within the PreBötC

We recently identified multiple Math1-dependent rhombic lip-derived populations in the medulla, including neurons near the pFRG/RTN, preBötC, and rVRG in the ventral respiratory column (VRC) (Rose et al., 2009). Unlike the paramotor lineages, these neurons did not co-express Phox2b (data not shown). To trace the projections of these neurons, we crossed hormone-inducible Math1Cre*PR/+ mice (Rose et al., 2009) to TaumGFP Cre-reporter mice (Hippenmeyer et al., 2005) in which myristylated GFP (mGFP) labels neuronal projections. We used the ROSAEYFP Cre-reporter allele to simultaneously visualize cell somas via EYFP expression. Since rhombic lip lineages express Math1 only briefly, induction of Math1Cre*PR on different embryonic days (by injection with the drug RU486) labels temporally-distinct Math1 populations with whichever Cre-reporter alleles are present.

Induction in Math1Cre*PR/+; ROSAEYFP/+; TaumGFP/+ mice at E10.5 and E12.5 produced distinct patterns of labeled projections and somas when analyzed at P0 (Figures 7B and 7C, corresponding to the model in Figure 7A). Within the VRC (depicted in Figure 7A′), induction at E10.5 labeled somas and projections in the preBötC and rVRG, but not in the adjacent lateral reticular nucleus (LRt) of the proprioceptive system (Figure 7B′). In contrast, induction at E12.5 labeled LRt somas and projections, but not the rVRG (Figure 7C′). A few parafacial cells were also labeled. Induction at E9.5 and E14.5 labeled very few projections within the VRC (data not shown). The E10.5-labeled neurons in the preBötC did not express NK1R or somatostatin, shown here on coronal sections (Figures 7D–7E′) corresponding to the boxed region in Figure 7A″. However, these cells did send processes near the NK1R- and somatostatin-expressing neurons (Figures 7D, inset and 7E″). These Math1-dependent neurons represent a previously undescribed preBötC population that may modulate the respiratory rhythmogenic neurons. In addition, analysis of nearby sections revealed processes from several additional Math1-dependent nuclei that could contribute to the E10.5-labeled projections within the VRC, including the parabrachial, dorsal column, spinal trigeminal, and medullary reticular nuclei (Figure S1).

Figure 7. Early Math1 Lineages Project to the Pre-Bötzinger Complex and the Rostral Ventral Respiratory Group.

(A) Sagittal model of the hindbrain, with midbrain visible at top, showing the PB and PPTg in the rostral pons, the motor nuclei V, VII, and X (all gray), and the ventral respiratory nuclei (black). (A′) Sagittal model of nuclei in the ventral respiratory column, magnified from boxed region in (A). (A″) Model of a coronal section through the medulla at the level of the preBotC (yellow circle), indicated by the vertical dotted line on (A).

(B,C) Sagittal sections from P0 Math1Cre*PR/+;ROSAEYFP/+;TaumGFP/+ hindbrains induced at either (B) E10.5 or (C) E12.5, showing antibody labeling of mGFP projections and EYFP cell somas (both black) of lineages expressing Math1 at those respective time points. (B′,C′) show magnifications of boxed regions in (B,C). Upper brackets indicate approximate rostral-caudal extent of nuclei and black dotted line marks caudal edge of VII. Labeled projections and cell somas were observed in the preBötC (yellow circle) with induction at (B′) E10.5 and to a lesser degree at (C′) E12.5. The rVRG is dorsal to the LRt and contained projections and cell somas when induced at E10.5, whereas LRt cell somas were labeled at E12.5. Vertical black dotted line in (B′) indicates approximate section level in (D–E″).

(D,E) Correspond to the boxed region in (A″). (D) Coronal section through the preBotC of a Math1Cre*PR/+; ROSAEYFP/+ medulla induced at E10.5 showing that EYFP cell somas (Math1 lineages, green) did not co-label with NK1R (red), although EYFP processes appeared near the NK1R neurons (inset). (E) Coronal section through the preBötC of a Math1Cre*PR/+; ROSAEYFP/+; TaumGFP/+ medulla induced at E10.5 showing that EYFP cell somas (green) also did not co-label with somatostatin (red). (E′) is a magnification of the yellow box in (E) showing the close proximity of Math1 lineages and somatostatin neurons in the preBötC. (E″) shows mGFP-labeled projections from Math1 lineages juxtaposed to the somatostatin neurons, magnified from the yellow box in (E′). Asterisks indicate motor nucleus X. Rostral is to the left in A–C′ and lateral is to the left in D–E″.

Abbreviations: cerebellum (cb), medulla (me), pons (pn), and the ambiguus (X), Bötzinger complex (BötC), facial motor (VII), lateral reticular (LRt), parabrachial (PB), parafacial respiratory group/retrotrapezoid (pFRG/RTN), pedunculopontine tegmental (PPTg), pre-Bötzinger complex (preBötC), and rostral ventral respiratory group (rVRG) nuclei. Scale bar, 1450 μm (B,C), 140 μm (B′,C′), 40 μm (D,E), 8 μm (E′), 3 μm (E″).

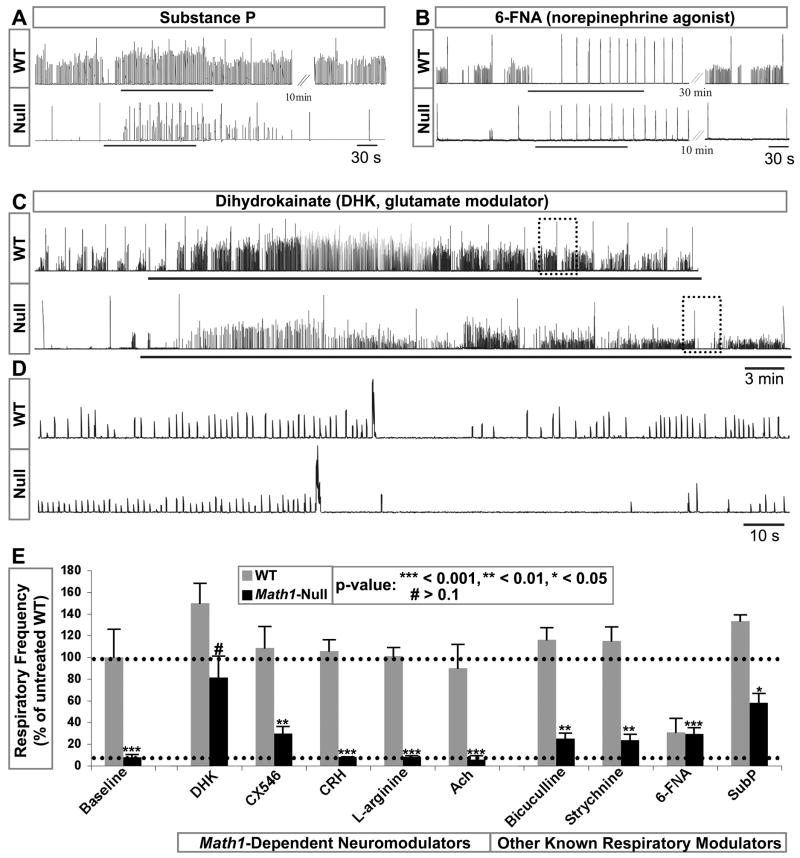

Glutamate Modulation Re-Establishes a Respiratory Rhythm in Math1-Null Preparations

Since the known preBötC rhythmogenic neurons are preserved in Math1-null mice, we examined their responses to neuromodulation and sought to determine whether specific modulators could re-establish a respiratory rhythm in Math1-null preparations. We again used diaphragmatic EMG in brainstem-spinal cord preparations (medulla-only, see Figure 1A). (Selective recordings and quantification are shown in Figure 8. See Table S1 for a complete list of neuromodulators tested, frequency, sample size, statistical analysis, and coefficient of variation).

Figure 8. Glutamate Modulation Re-establishes a Respiratory Rhythm in the Math1-Null Brainstem.

Data from integrated, rectified diaphragm recordings from WT and Math1-null mouse brainstem-spinal cord preparations.

(A,B) The very slow rhythms generated in the Math1-null mouse were increased by substance P (SubP), whereas modulation with the 1 norepinephrine receptor agonist 6-FNA equalized the WT and Math1-null rhythms at a slow and regular frequency.

(C,D) The Math1-null respiratory frequency was increased tenfold after bath application of the glutamate reuptake inhibitor DHK. The Math1-null respiratory pattern also showed some WT attributes, including short apneic periods following high-amplitude bursts, best visualized on expanded time scales (D, from dotted boxes in (C)).

(E) Population data as a percent of baseline untreated WT rhythm: Corticotropin releasing hormone and L-Arginine (a nitric oxide synthase substrate) had no effect. Likewise, Ach had no effect while CX546 provided some stimulation. (Ach and CX546 only are from integrated, rectified C4 recordings-without diaphragm). Bicuculline and Strychnine showed some improvement in frequency. However, DHK was the only condition in which the treatment increased the Math1-null frequency to the level of the untreated wild-type. See Table S1 for complete list of modulators tested, sample sizes, frequencies, and coefficients of variation for the burst intervals.

Abbreviations: 6-fluoronoradrenaline (6-FNA), acetylcholine (Ach), ampakine (CX546), cervical spinal cord nerve roots (C4), dihydrokainate (DHK), serotonin (5-HT), substance P (SubP), thyrotropin releasing hormone (TRH).

Substance P rapidly increased the respiratory rhythm in Math1-null preparations, indicating the presence of functional NK1R rhythm-generating neurons, but did not restore the Math1-null rhythm to the WT frequency or pattern (Figure 8A; quantified in Figure 8E). Norepinephrine, another known respiratory rhythm modulator, equalized the WT and Math1-null rhythms to a slow, regular pace, as if superimposing a distinct rhythm on both preparations, potentially bypassing the Math1-null deficit (Figures 8B, 8E). Bicuculline and strychnine, which block the inhibitory effects of GABAA and glycine receptors, respectively, only modestly increased burst frequency in Math1-null preparations (Figure 8E).

By comparison, the glutamate reuptake inhibitor dihydrokainic acid (DHK), which elevates the levels of endogenous glutamate in the synaptic cleft, raised the frequency in the Math1-null preparations to near-WT levels (p-value of 0.129 indicated lack of significant frequency difference compared to untreated WT) (Figures 8C–8E). DHK also reestablished a rhythmic pattern in the Math1-null preparation that approximated aspects of the WT rhythm: a series of low-amplitude bursts followed by a single large-amplitude burst was in turn followed by a pause before resuming low-amplitude bursts (shown on the expanded time-scale in Figure 8D). Additional glutamate modulation with ampakine (CX546), which accentuates endogenous glutamatergic signaling, also increased the respiratory frequency (Figure 8E). Other Math1-dependent neuromodulators including acetylcholine, corticotropin releasing hormone (CRH), and nitric oxide (using L-arginine as a substrate of nitric oxide synthase) (Rose et al., 2009), all failed to stimulate the Math1-null rhythm (Figure 8E). Thus, among the Math1-dependent neuromodulators, only glutamatergic modulation significantly changed the Math1-null rhythm to resemble the baseline WT preparation (Table S1).

DISCUSSION

In this study, we combined physiological, histological, and genetic fate-mapping approaches to determine the cause of the breathing defect in Math1-null mice. Physiological analysis of perinatal Math1-null mice revealed a profoundly slow respiratory rhythm at the level of the medulla. Using a Math1-EGFP fusion allele, we identified developing Math1-dependent hindbrain cells with novel non-rhombic lip Math1 expression that ultimately formed the Phox2b/Lbx1/NK1R/Math1-expressing neurons of the parafacial respiratory group/retrotrapezoid nucleus (pFRG/RTN). Using an inducible Math1Cre*PR targeted allele, we also found that several early Math1-dependent lineages project within the ventral respiratory column (VRC), including the preBötC. Finally, of the neuromodulators lost in Math1-null mice, only glutamatergic modulation reestablished a respiratory rhythm in Math1-null preparations. These findings indicate that respiratory failure in Math1-null mice most likely results from compromised glutamatergic excitatory drive, and they establish a genetic link between Math1 and neurons disrupted in congenital central hypoventilation syndrome (CCHS).

Math1-Dependent Neurons Provide Excitatory Drive Critical for Respiratory Rhythmogenesis

Previous studies have found that excitatory glutamatergic input is vital for maintaining the activity of preBötC respiratory rhythm-generating neurons (Greer et al., 1991; Pace et al., 2007). The source of this glutamatergic drive, however, has not been fully determined, and further characterization is important to better understand respiratory disorders like CCHS and sudden infant death syndrome (SIDS). The partial rescue of the respiratory rhythm in Math1-null tissue preparations by glutamatergic modulation is consistent with compromised glutamatergic drive in these mice. Such a deficit could be caused by a variety of mechanisms, some of which have been seen in previous mouse models, including those with disruptions of the NK1R or somatostatin rhythmogenic neurons in the preBötC (Gray et al., 1999; Tan et al., 2008), or an imbalance of excitatory or inhibitory hindbrain neurons such as occurs in Lbx1 and Tlx3(Rnx)-deficient mice (Pagliardini et al., 2008; Shirasawa et al., 2000). In contrast, we see neither a fate-switch nor an increase in inhibitory GABAergic or glycinergic neurons in Math1-null mice (Rose et al., 2009), and antagonists of these neurotransmitters only modestly stimulate the Math1-null rhythm, arguing against a simple imbalance in excitatory/inhibitory inputs. Likewise, the Math1-null mice retain NK1R and somatostatin preBötC neurons, and the brainstem preparations generate a fast rhythm upon stimulation by substance P, demonstrating that these neurons are functional. Some neurons within the preBötC are synaptically coupled and glutamatergic (Guyenet et al., 2002; Pace and Del Negro, 2008), thereby providing a potential source of glutamate within the Math1-null preBötC that can be amplified, as we found, to reestablish a respiratory rhythm. However, these glutamatergic neurons are not sufficient to generate the respiratory rhythm on their own.

Rather, it appears that Math1 is essential for neurons that provide excitatory conditioning drive to the preBötC. This modulation could arise from Math1-dependent glutamatergic neurons projecting either directly into the preBötC or into other hindbrain respiratory centers, from non-glutamatergic Math1-dependent neurons that amplify glutamatergic signaling, or from a combination of modalities. In addition to losing specific glutamatergic neurons, Math1-null mice lose most nitric oxide (NO) and corticotropin releasing hormone (CRH) neurons in the VRC, as well as all cholinergic neurons (ACh) of the reticular activating system (Rose et al., 2009). All three neuromodulators (NO, CRH, and ACh) appear to enhance excitatory glutamatergic signals and stimulate respiration perinatally (Bennet et al., 1990; Hirsch et al., 1993; Pierrefiche et al., 2002; Shao and Feldman, 2005) and so could represent indirect mechanisms for Math1-dependent glutamatergic drive. Nevertheless, Math1-null hindbrain preparations showed very little response to any of these modulators. So although Math1-dependent NO, CRH, and ACh neurons may have roles in respiration, their loss is not the critical deficit. Rather, Math1-dependent glutamatergic neurons appear more likely to provide the vital excitatory drive to the respiratory rhythm that is lost in Math1-null mice.

Math1-Expression Identifies the Developing pFRG/RTN

The pFRG/RTN has been proposed as one source of glutamatergic excitatory drive to the preBötC and contains CO2 chemosensitive neurons co-expressing Phox2b, Lbx1, NK1R, and Vglut2 (Nattie and Li, 2002; Onimaru et al., 2008; Pagliardini et al., 2008; Stornetta et al., 2006; Weston et al., 2004). Mutations in Phox2b are associated with CCHS (Ondine’s curse), in which patients fail to increase respiration in response to rising blood CO2 levels (Amiel et al., 2003), and Phox2b-mutant mice show loss of pFRG/RTN neurons and fatal respiratory depression (Dubreuil et al., 2008). We show that Math1 is also required for the proper development of the Phox2b/Lbx1/NK1R-expressing neurons of the pFRG/RTN, demonstrating a novel link between Math1 and CCHS and indicating a potential source of Math1-dependent glutamatergic drive to the respiratory rhythm. Unlike Phox2b mutant mice in which pFRG/RTN neurons are lost after migrating to the ventral medullary surface, the pFRG/RTN neurons in Math1-null mice fail to reach their destinations and do not express NK1R. Mutations in HATH1 (the Math1 human homologue) and its transcriptional targets could thus represent a distinct mechanism of disease in disorders of respiratory control.

Using the new Math1M1GFP allele, we were able to observe pFRG/RTN neurons earlier in development than previously possible. Math1 expression uncovered developmental and genetic similarities between the pFRG/RTN and a group of paratrigeminal neurons, some of which reside in the intertrigeminal region that is associated with apneic reflexes and jaw opening (Chamberlin and Saper, 1998; Luo et al., 2001). The developing pFRG/RTN and paratrigeminal neurons appear to migrate in parallel around the facial and trigeminal motor nuclei towards the ventral surface of the medulla and pons, respectively. In addition, these paramotor neurons are the only Math1 cells to co-express Phox2b and Lbx1, and represent the first known instance of persistent Math1 hindbrain expression outside the rhombic lip and the external granule layer of the developing cerebellum. Because Phox2b and Lbx1 appear prior to Math1 in these regions and remain in the absence of Math1, they are not Math1-dependent, unlike NK1R. Interestingly, many surrounding Phox2b and Lbx1 lineages form noradrenergic, cholinergic, or inhibitory GABAergic neurons, whereas Math1-expressing lineages frequently express glutamatergic markers. It is possible that co-expression of Math1 with Phox2b/Lbx1 helps determine glutamatergic fate in pFRG/RTN neurons. These studies demonstrate that the pFRG/RTN is part of a broader developmental pattern of neurons surrounding both the facial and trigeminal motor nuclei, suggesting that these neurons could share other traits such as specific functions and/or susceptibility in disease.

The Math1-Dependent Hindbrain Network Links Proprioception, Hearing, and Arousal with Breathing

Failure to stimulate respiration and/or arouse from sleep during hypoxia/hypercapnia have been proposed to underlie both CCHS and SIDS (Kato et al., 2003; Nattie and Li, 2002; Phillipson and Sullivan, 1978). Disruptions of sensory systems involved in arousal, such as the proprioceptive, interoceptive, and auditory systems, could thus be involved in congenital respiratory disorders. Perinatal Math1-null mice do not yawn or stretch, unlike WT mice in which those movements are integral to their first breaths. Yawning and stretching stimulate the somatic proprioceptive system via movement of the jaw and limb joints, and this information travels to the reticular activating system to stimulate arousal (McNamara et al., 1998). Previous studies have identified multiple Math1-dependent neurons in the proprioceptive and arousal systems (Ben-Arie et al., 1997; Ben-Arie et al., 2000; Machold and Fishell, 2005; Rose et al., 2009; Wang et al., 2005). Similarly, bladder distension, a form of interoception, activates the Math1-dependent Barrington’s nucleus and can likewise arouse individuals from sleep (Rose et al., 2009) (Rouzade-Dominguez et al., 2003). The auditory startle response also stimulates arousal from sleep and requires multiple nuclei that lose neurons in Math1-null mice (Reese et al., 1995; Rose et al., 2009; Wang et al., 2005). We now describe network connections between early-born Math1-dependent lineages and the ventral respiratory column, including neurons within the pFRG/RTN and preBötC themselves and possibly from more distant sources in the pons. These results point to a network of proprioceptive and arousal neurons that might ultimately contribute excitatory modulation to the respiratory system.

Neuropathological studies have shown that some infants with SIDS display histological changes in the external granule layer and deep nuclei of the cerebellum that function in proprioception, as well as in the parabrachial and pedunculopontine tegmental nuclei important for interoception and arousal (Lavezzi et al., 2006; Sawaguchi et al., 2002), all of which contain Math1-dependent neurons. Given these observations and the new role of Math1 in the development of respiratory nuclei such as the pFRG/RTN, we propose it will be valuable to look for changes in other Math1-dependent lineages in SIDS patients.

In summary, we have uncovered Math1-null neuronal deficits in multiple hindbrain respiratory nuclei that work in concert to stimulate respiration at birth. We show that proper development of the parafacial respiratory group/retrotrapezoid nucleus requires Math1, thereby providing a link between Math1 and neurons disrupted in CCHS. In addition, the requirement of Math1 for many neurons of the proprioceptive and arousal systems suggests that deficits in these systems may also contribute to the Math1-null respiratory dysfunction. Although the Math1-null mice lose multiple neuronal subtypes, only glutamatergic modulation can reestablish a rapid and patterned respiratory rhythm, suggesting that loss of glutamatergic drive is likely a critical limiting deficit in respiratory rhythmogenesis in Math1-null mice. Overall, this study broadens the set of neurons and neurotransmitter systems that should be investigated in individuals with CCHS, SIDS, and other congenital respiratory disorders.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Generation of Math1-EGFP Fusion (Math1M1GFP) Mice

The EGFP sequence from pEGFPN1 was ligated to the 3′ end of the Math1 coding sequence with a short linking peptide (5′-AspIleLeuAspProProValAlaThr-3′; 5′-GATATCCTGGATCCACCGGTCGCCACC-3′, which incudes EcoRV and BamHI sites) and then ligated with Math1 5′ and 3′ targeting arms such that the Math1 transcription start site was preserved (5′ SphI and 3′ SalI insertion sites), identical to the approach used to target Cre*PR to the Math1 locus (Rose et al., 2009). An frt-bounded PGK-Neo selectable marker (Meyers et al., 1998) and an additional EcoRI restriction site for Southern genotyping were inserted immediately 3′ to the Math1EGFP open reading frame in a pBlueScript II KS+ plasmid (pMath1EGFP_Neo). The construct was electroporated into AB2.2 ES cells and selected under G418 (Gibco, Gaithersburg, MD) for 10 days. Resistant clones were screened for correct recombination by Southern blot using internal 5′ and external 3′ probes, and then injected into blastocysts to generate chimeras. Mice heterozygous for Math1M1GFP_Neo were crossed to ROSAFLPe mice (FLPeR) (Farley et al., 2000) to remove PGK-Neo and generate the final Math1M1GFP/+ line. The line was then intercrossed to generate homozygous viable Math1M1GFP/M1GFP mice. (See Figure 3 for genomic targeting diagram, confirmation of insertion locus by Southern blot, and example PCR genotyping.)

Mouse Strains, Staging, and Genotyping

This study used two null alleles of Math1 which contain either LacZ (Math1LacZ) (Ben-Arie et al., 2000), or Cre*PR (Math1Cre*PR) (Rose et al., 2009) in place of the Math1 open reading frame. Two Cre reporter lines were used: ROSAEYFP, and TaumGFP (Hippenmeyer et al., 2005; Srinivas et al., 2001). For staging, noon on the day that the vaginal plug was observed was counted as embryonic day 0.5 (E0.5). Yolk sacs or tails were collected for PCR genotyping as described previously (Wang et al., 2005). PCR genotyping of the new Math1M1GFP line used Math1EGFP forward (GCGATGATGGCACAGAAGG) and reverse (GAAGGGCATTTGGTTGTCTCAG) primers (WT: 200 bp; Math1EGFP: 1.1kb). All animals were housed in a pathogen-free mouse colony in compliance with the guidelines of the Center of Comparative Medicine of Baylor College of Medicine.

Induction of Cre*PR Activity in Math1Cre*PR Mice

Induction of Cre*PR activity in Math1Cre*PR mice was performed at specific embryonic times: E9.5, E10.5, E12.5, and E14.5 (Rose et al., 2009).

X-gal Staining and Immunohistochemistry

For X-gal studies, Math1LacZ embryos were collected at E16.5 and E18.5. Hindbrains were examined as whole-mounts and by serial coronal sectioning. β-galactosidase (β-gal) activity was assayed by staining tissues with X-gal (1 mg/ml) followed by paraffin embedding. Ten-micron paraffin sections were counterstained with nuclear fast red (Wang et al., 2005). Specimens were examined on a Zeiss Axioplan light microscope and images were collected with a Zeiss AxioCam.

For immunolabeling, embryos of Math1M1GFP/M1GFP, Math1LacZ/+, Math1LacZ/LacZ, and Math1Cre*PR/+ crossed to ROSAEYFP and/or TaumGFP mice were collected at various stages (E10.5-P0). The brain was isolated from E16.5 and older embryos, while the whole embryo was collected for younger stages. Specimens were fixed in 4% PFA at 4°C for 4–10 hours (E14.5-P0) or 0.5–2 hours (E10.5–12.5). Frozen sections were cut at either 25 μm (E12.5 and older), 16 μm (E12.0 and younger), or 50 μm (for projection analyses). Primary and secondary antibody staining was performed as previously described (Wang et al., 2005). The antibodies and their dilutions used in this study were as follows: rabbit anti-β-gal (1:2000, Rockland), GFP (1:1000, Abcam), NK1R (1:500, Advanced Targeting Systems), Sst-28 (1:1000, ImmunoStar); chicken anti- GFP (1:2000, Abcam), tyrosine hydroxylase (1:1000, Abcam); goat anti- β-gal (1:1000, Serotec), Vacht (1:1000, Millipore), Phox2b (1:500, Santa Cruz); guinea pig anti- Lbx1 (1:10000, gift from C. Birchmeier), Vglut1 (1:2000, Chemicon), Vglut2 (1:2000, Chemicon); and secondaries goat and donkey Alexa Fluor 488 and 555 (1:2000, Molecular Probes), donkey Cy 3 and Cy5 (1:2000, Jackson Immuno Research) and DAPI nuclear counter stain (1:10000, Roche). Primary labeling was performed for 12 hours at 4°C, followed by secondary labeling for 6 hours at 4°C. Slides were mounted in Prolong Gold (Molecular Probes) and fluorescent staining was examined by confocal microscopy (Zeiss Axiovert LSM 510 and Leica TCS SP5 systems). Image brightness and contrast were normalized using Adobe Photoshop.

Physiological Analyses

Physiological analysis is derived from 30 Math1+/+, 55 Math1lacZ/+ and 40 Math1lacZ/lacZ embryos (E18.5). The physiology of Math1+/+ and Math1+/lacZ mice was indistinguishable and was pooled for analysis.

Brain stem-spinal cord preparations

Fetal mice (E18.5) were delivered from timed-pregnant mice anaesthetized with halothane (1.8% delivered in 95%O2 and 5%CO2) and maintained at 37°C by radiant heat. Fetuses were decerebrated and recordings were done from the brain stem-spinal cord with or without the ribcage and diaphragm muscle attached (Greer et al., 1992; Smith et al., 1990). The neuraxis was continuously perfused at 28±1°C with artificial cerebral spinal fluid that contained (mM): 128 NaCl, 3.0 KCl, 1.5 CaCl2, 1.0 MgSO4, 24 NaHCO3, 0.5 NaH2PO4, and 30 D-glucose equilibrated with 95%O2 - 5%CO2 (perfusion rate 5 ml/minute, chamber volume of 3 ml for diaphragm EMG, and 1.5 ml for direct C4 ventral root recordings).

Medullary slice preparations

Details of the preparation have been previously described (Smith et al., 1991). Briefly, the brain stem-spinal cords isolated from fetal mice were pinned down, ventral surface upward, on a paraffin-coated block. The block was mounted in the vise of a vibratome bath (LeicaVT1000S). The brain stem was sectioned serially in the transverse plane starting from the rostral medulla to within ~100 μm of the rostral boundary of the pre-Bötzinger complex (preBötC), as judged by the appearance of the inferior olive. A single transverse slice containing the preBötC and more caudal reticular formation regions was then cut (~500 μm thick), transferred to a recording chamber and pinned down onto a Sylgard elastomer. The medullary slice was continuously perfused in physiological solution similar to that used for the brain stem-spinal cord preparation except for the potassium concentration, which was increased to 9 mM to stimulate the spontaneous rhythmic respiratory motor discharge in the medullary slice (Smith et al., 1991).

Neuromodulation

Multiple neuromodulators were added to the bath solution to assess the responses in WT and Math1-null brainstem-spinal cord preparations: CRH (0.1 μM), L-arginine (1000 μM), acetylcholine (30 μM), ampakine CX546 (400 μM), dihydrokainate (150 μM), naloxone (1 μM), bicuculline (10 μM), strychnine (1 μM), clonidine (30 μM), norepinephrine (10 μM), 6-FNA (10 μM), serotonin (20 μM), TRH (0.5 μM), SubP (0.5 μM) (Table S1).

Recording and analysis

Recordings of hypoglossal (XII) cranial nerve roots, cervical (C4) ventral roots and diaphragm EMG were made with suction electrodes. Further, suction electrodes were placed into the XII nuclei and the preBötC to record extracellular neuronal population discharge from medullary slice preparations. Signals were amplified, rectified, low-passed filtered and recorded on computer using an analog-digital converter (Digidata 1200, Axon Instruments) and data acquisition software (Axoscope, Axon Instruments). Mean values relative to control for the period and peak integrated amplitude of respiratory motoneuron discharge were calculated. Values given are means, standard deviation of the mean (S.D.) and coefficient of variation (standard deviation/mean). Statistical significance was tested using either paired or unpaired Student’s t test; significance was accepted at P values lower than 0.05 (Table S1).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank R. Atkinson, A. Liang, B. Antalffy, N. Ao, and Y. Liu (Baylor College of Medicine, BCM) for assistance with histological preparations, C. Birchmeier for kindly providing the Lbx1 antibody, and B. Jusiak (BCM) for comments on the manuscript. This work was supported by National Research Service Award Kirschstein Predoctoral Fellowships from NINDS (M.F.R., 5F31-NS051046) and NIMH (H.T.C., 1F31-MH078678), a Pediatric Scientist Development Program Award from NICHD (K.A.A., K12-HD000850), Baylor Research Advocates for Student Scientists Scholarships (M.F.R. and H.T.C.), a McNair Fellowship (H.T.C.), and the Gene Expression and Microscopy Cores of the Baylor IDDRC (HD024064). H.Y.Z. is an Investigator of the Howard Hughes Medical Institute.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Amiel J, Laudier B, Attie-Bitach T, Trang H, de Pontual L, Gener B, Trochet D, Etchevers H, Ray P, Simonneau M, et al. Polyalanine expansion and frameshift mutations of the paired-like homeobox gene PHOX2B in congenital central hypoventilation syndrome. Nat Genet. 2003;33:459–461. doi: 10.1038/ng1130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ben-Arie N, Bellen HJ, Armstrong DL, McCall AE, Gordadze PR, Guo Q, Matzuk MM, Zoghbi HY. Math1 is essential for genesis of cerebellar granule neurons. Nature. 1997;390:169–172. doi: 10.1038/36579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ben-Arie N, Hassan BA, Bermingham NA, Malicki DM, Armstrong D, Matzuk M, Bellen HJ, Zoghbi HY. Functional conservation of atonal and Math1 in the CNS and PNS. Development. 2000;127:1039–1048. doi: 10.1242/dev.127.5.1039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bennet L, Johnston BM, Vale WW, Gluckman PD. The effects of corticotrophin-releasing factor and two antagonists on breathing movements in fetal sheep. J Physiol. 1990;421:1–11. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1990.sp017930. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chamberlin NL, Saper CB. Topographic organization of respiratory responses to glutamate microstimulation of the parabrachial nucleus in the rat. J Neurosci. 1994;14:6500–6510. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.14-11-06500.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chamberlin NL, Saper CB. A brainstem network mediating apneic reflexes in the rat. J Neurosci. 1998;18:6048–6056. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.18-15-06048.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dubreuil V, Ramanantsoa N, Trochet D, Vaubourg V, Amiel J, Gallego J, Brunet JF, Goridis C. A human mutation in Phox2b causes lack of CO2 chemosensitivity, fatal central apnea, and specific loss of parafacial neurons. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105:1067–1072. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0709115105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farley FW, Soriano P, Steffen LS, Dymecki SM. Widespread recombinase expression using FLPeR (flipper) mice. Genesis. 2000;28:106–110. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gray PA, Rekling JC, Bocchiaro CM, Feldman JL. Modulation of respiratory frequency by peptidergic input to rhythmogenic neurons in the preBotzinger complex. Science. 1999;286:1566–1568. doi: 10.1126/science.286.5444.1566. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greer JJ, Smith JC, Feldman JL. Role of excitatory amino acids in the generation and transmission of respiratory drive in neonatal rat. J Physiol. 1991;437:727–749. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1991.sp018622. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greer JJ, Smith JC, Feldman JL. Respiratory and locomotor patterns generated in the fetal rat brain stem-spinal cord in vitro. J Neurophysiol. 1992;67:996–999. doi: 10.1152/jn.1992.67.4.996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guyenet PG, Sevigny CP, Weston MC, Stornetta RL. Neurokinin-1 receptor-expressing cells of the ventral respiratory group are functionally heterogeneous and predominantly glutamatergic. J Neurosci. 2002;22:3806–3816. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.22-09-03806.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hippenmeyer S, Vrieseling E, Sigrist M, Portmann T, Laengle C, Ladle DR, Arber S. A developmental switch in the response of DRG neurons to ETS transcription factor signaling. PLoS Biol. 2005;3:e159. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0030159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirsch DB, Steiner JP, Dawson TM, Mammen A, Hayek E, Snyder SH. Neurotransmitter release regulated by nitric oxide in PC-12 cells and brain synaptosomes. Curr Biol. 1993;3:749–754. doi: 10.1016/0960-9822(93)90022-g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacquin TD, Borday V, Schneider-Maunoury S, Topilko P, Ghilini G, Kato F, Charnay P, Champagnat J. Reorganization of pontine rhythmogenic neuronal networks in Krox-20 knockout mice. Neuron. 1996;17:747–758. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80206-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Janczewski WA, Feldman JL. Distinct rhythm generators for inspiration and expiration in the juvenile rat. J Physiol. 2006;570:407–420. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2005.098848. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kato I, Franco P, Groswasser J, Scaillet S, Kelmanson I, Togari H, Kahn A. Incomplete arousal processes in infants who were victims of sudden death. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2003;168:1298–1303. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200301-134OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kubin L, Fenik V. Pontine cholinergic mechanisms and their impact on respiratory regulation. Respir Physiol Neurobiol. 2004;143:235–249. doi: 10.1016/j.resp.2004.04.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lavezzi AM, Ottaviani G, Mauri M, Matturri L. Alterations of biological features of the cerebellum in sudden perinatal and infant death. Curr Mol Med. 2006;6:429–435. doi: 10.2174/156652406777435381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luo P, Moritani M, Dessem D. Jaw-muscle spindle afferent pathways to the trigeminal motor nucleus in the rat. J Comp Neurol. 2001;435:341–353. doi: 10.1002/cne.1034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Machold R, Fishell G. Math1 is expressed in temporally discrete pools of cerebellar rhombic-lip neural progenitors. Neuron. 2005;48:17–24. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2005.08.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McNamara F, Wulbrand H, Thach BT. Characteristics of the infant arousal response. J Appl Physiol. 1998;85:2314–2321. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1998.85.6.2314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meyers EN, Lewandoski M, Martin GR. An Fgf8 mutant allelic series generated by Cre- and Flp-mediated recombination. Nat Genet. 1998;18:136–141. doi: 10.1038/ng0298-136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nattie EE, Li A. Substance P-saporin lesion of neurons with NK1 receptors in one chemoreceptor site in rats decreases ventilation and chemosensitivity. J Physiol. 2002;544:603–616. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2002.020032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Onimaru H, Homma I. A novel functional neuron group for respiratory rhythm generation in the ventral medulla. J Neurosci. 2003;23:1478–1486. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.23-04-01478.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Onimaru H, Ikeda K, Kawakami K. CO2-sensitive preinspiratory neurons of the parafacial respiratory group express Phox2b in the neonatal rat. J Neurosci. 2008;28:12845–12850. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3625-08.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pace RW, Del Negro CA. AMPA and metabotropic glutamate receptors cooperatively generate inspiratory-like depolarization in mouse respiratory neurons in vitro. Eur J Neurosci. 2008;28:2434–2442. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2008.06540.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pace RW, Mackay DD, Feldman JL, Del Negro CA. Inspiratory bursts in the preBotzinger complex depend on a calcium-activated non-specific cation current linked to glutamate receptors in neonatal mice. J Physiol. 2007;582:113–125. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2007.133660. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pagliardini S, Ren J, Gray PA, Vandunk C, Gross M, Goulding M, Greer JJ. Central respiratory rhythmogenesis is abnormal in lbx1- deficient mice. J Neurosci. 2008;28:11030–11041. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1648-08.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pearce RA, Stornetta RL, Guyenet PG. Retrotrapezoid nucleus in the rat. Neurosci Lett. 1989;101:138–142. doi: 10.1016/0304-3940(89)90520-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phillipson EA, Sullivan CE. Arousal: the forgotten response to respiratory stimuli. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1978;118:807–809. doi: 10.1164/arrd.1978.118.5.807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pierrefiche O, Maniak F, Larnicol N. Rhythmic activity from transverse brainstem slice of neonatal rat is modulated by nitric oxide. Neuropharmacology. 2002;43:85–94. doi: 10.1016/s0028-3908(02)00073-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reese NB, Garcia-Rill E, Skinner RD. The pedunculopontine nucleus--auditory input, arousal and pathophysiology. Prog Neurobiol. 1995;47:105–133. doi: 10.1016/0301-0082(95)00023-o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rose MF, Ahmad KA, Thaller C, Zoghbi HY. Excitatory neurons of the proprioceptive, interoceptive, and arousal hindbrain networks share a developmental requirement for Math1. PNAS. 2009 doi: 10.1073/pnas.0911579106. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rouzade-Dominguez ML, Pernar L, Beck S, Valentino RJ. Convergent responses of Barrington’s nucleus neurons to pelvic visceral stimuli in the rat: a juxtacellular labelling study. Eur J Neurosci. 2003;18:3325–3334. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2003.03072.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sawaguchi T, Franco P, Kato I, Shimizu S, Kadhim H, Groswasser J, Sottiaux M, Togari H, Kobayashi M, Takashima S, et al. From epidemiology to physiology and pathology: apnea and arousal deficient theories in sudden infant death syndrome (SIDS)--with particular reference to hypoxic brainstem gliosis. Forensic Sci Int. 2002;130(Suppl):S21–29. doi: 10.1016/s0379-0738(02)00135-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Severinghaus JW, Mitchell RA. Ondine’s curse failure of respiratory center automatically while awake (abstract) Clin Res. 1962;10:122. [Google Scholar]

- Shao XM, Feldman JL. Cholinergic neurotransmission in the preBotzinger Complex modulates excitability of inspiratory neurons and regulates respiratory rhythm. Neuroscience. 2005;130:1069–1081. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2004.10.028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shirasawa S, Arata A, Onimaru H, Roth KA, Brown GA, Horning S, Arata S, Okumura K, Sasazuki T, Korsmeyer SJ. Rnx deficiency results in congenital central hypoventilation. Nat Genet. 2000;24:287–290. doi: 10.1038/73516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith JC, Ellenberger HH, Ballanyi K, Richter DW, Feldman JL. Pre-Botzinger complex: a brainstem region that may generate respiratory rhythm in mammals. Science. 1991;254:726–729. doi: 10.1126/science.1683005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith JC, Greer JJ, Liu GS, Feldman JL. Neural mechanisms generating respiratory pattern in mammalian brain stem-spinal cord in vitro. I. Spatiotemporal patterns of motor and medullary neuron activity. J Neurophysiol. 1990;64:1149–1169. doi: 10.1152/jn.1990.64.4.1149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith JC, Morrison DE, Ellenberger HH, Otto MR, Feldman JL. Brainstem projections to the major respiratory neuron populations in the medulla of the cat. J Comp Neurol. 1989;281:69–96. doi: 10.1002/cne.902810107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Srinivas S, Watanabe T, Lin CS, William CM, Tanabe Y, Jessell TM, Costantini F. Cre reporter strains produced by targeted insertion of EYFP and ECFP into the ROSA26 locus. BMC Dev Biol. 2001;1:4. doi: 10.1186/1471-213X-1-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stornetta RL, Moreira TS, Takakura AC, Kang BJ, Chang DA, West GH, Brunet JF, Mulkey DK, Bayliss DA, Guyenet PG. Expression of Phox2b by brainstem neurons involved in chemosensory integration in the adult rat. J Neurosci. 2006;26:10305–10314. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2917-06.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tan W, Janczewski WA, Yang P, Shao XM, Callaway EM, Feldman JL. Silencing preBotzinger complex somatostatin-expressing neurons induces persistent apnea in awake rat. Nat Neurosci. 2008;11:538–540. doi: 10.1038/nn.2104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thoby-Brisson M, Karlen M, Wu N, Charnay P, Champagnat J, Fortin G. Genetic identification of an embryonic parafacial oscillator coupling to the preBotzinger complex. Nat Neurosci. 2009;12:1028–1035. doi: 10.1038/nn.2354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang VY, Rose MF, Zoghbi HY. Math1 expression redefines the rhombic lip derivatives and reveals novel lineages within the brainstem and cerebellum. Neuron. 2005;48:31–43. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2005.08.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weston MC, Stornetta RL, Guyenet PG. Glutamatergic neuronal projections from the marginal layer of the rostral ventral medulla to the respiratory centers in rats. J Comp Neurol. 2004;473:73–85. doi: 10.1002/cne.20076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.