Abstract

Sulfite oxidase (SO) is a vitally important molybdenum enzyme that catalyzes the oxidation of toxic sulfite to sulfate. The proposed catalytic mechanism of vertebrate SO involves two intramolecular one-electron transfer (IET) steps from the molybdenum cofactor to the iron of the integral b-type heme and two intermolecular one-electron steps to exogenous cytochrome c. In the crystal structure of chicken SO (Kisker et al., Cell, 1997, 91, 973–983), which is highly homologous to human SO (HSO), the heme iron and molybdenum centers are separated by 32 Å, and the domains containing these centers are linked by a flexible polypeptide tether. Conformational changes that bring these two centers into closer proximity have been proposed (Feng et al., Biochemistry, 2003, 41, 5816–21) to explain the relatively rapid IET kinetics, which are much faster than theoretically predicted from the crystal structure. In order to explore the proposed role(s) of the tether in facilitating this conformational change, both its length and flexibility were altered in HSO by site-specific mutagenesis and the reactivities of the resulting variants have been studied using laser flash photolysis and steady-state kinetics assays. Increasing the flexibility of the tether by mutating several conserved proline residues to alanines did not produce a discernable systematic trend in the kinetic parameters, although mutation of one residue (P105) to alanine produced a three-fold decrease in the IET rate constant. Deletions of non-conserved amino acids in the 14-residue tether, thereby shortening its length, resulted in more drastically reduced IET rate constants. Thus, the deletion of five amino acid residues decreased IET by 70-fold, so that it was rate-limiting in the overall reaction. The steady-state kinetic parameters were also significantly affected by these mutations, with the P111A mutation causing a five-fold increase in the sulfite Km value, perhaps reflecting a decrease in the ability to bind sulfite. The electron paramagnetic resonance spectra of these Proline to Alanine and deletion mutants are identical to those of wild type HSO, indicating no significant change in the Mo active site geometry.

Sulfite oxidase (SO) catalyzes the oxidation of sulfite to sulfate, using oxidized ferricytochrome c (cyt cox) as the physiological electron acceptor (eq. 1) (1–4). This reaction is biologically essential, serving as the final step in the catabolism of sulfur containing amino acids, methionine and cysteine, and as a detoxification mechanism for sulfite.

| (1) |

In animals SO is located in the mitochondrial intermembrane space (5, 6), and the kinetics of chicken (7–9), rat (10) and human SO (11–15) have been extensively studied. The only crystal structure for an intact animal SO is that of the chicken liver enzyme (16). The structure confirms that the protein is a homodimer. Each ~51.5 kDa subunit contains a b5-type cytochrome heme domain (~10 kDa) at the N-terminus. The larger C-terminal domain contains the molybdopterin cofactor (Moco). These two domains are bridged by a flexible polypeptide tether (Figure 1) which is poorly resolved in the crystal structure (16). The distance between the Mo and Fe atoms in the crystal conformation is 32 Å, but the apparent disorder of the tether suggests that it has high flexibility and may mediate conformational changes that alter the distance between the Fe and Mo centers (17).

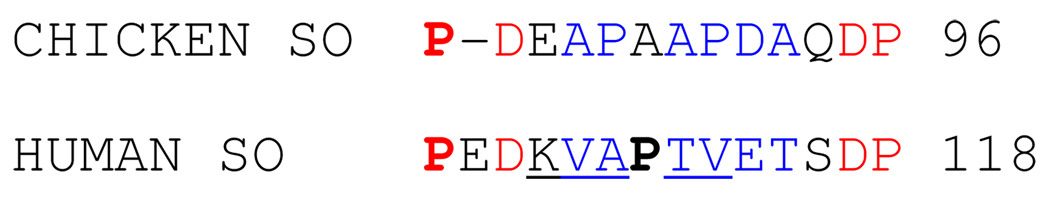

Figure 1.

Sequence alignment of the flexible tether regions of cSO and HSO. Amino acids highlighted in red are conserved between the two species, while those in blue are similar. Mutations discussed in this work are indicated in the HSO sequence: proline residues mutated to alanines are in bold type, and deleted residues are underlined.

The proposed catalytic mechanism of vertebrate SO involves two intramolecular one-electron transfer (IET) steps from the molybdenum cofactor to the heme iron, and two intermolecular one-electron steps to exogenous cytochrome c (cyt c) (1). Extensive investigations of the IET kinetics in cSO (7–9) and HSO (11–15) using laser flash photolysis have been reported. The observed IET rates are much faster than expected for electron tunneling processes (18, 19) based upon previous studies of electron tunneling kinetics in model systems and in proteins (19–41). For example, Gray and co-workers have correlated intramolecular electron tunneling rates with the donor-acceptor distance in protein solutions and structurally characterized crystals for more than 30 metalloproteins with a wide range of thermodynamic driving force (i.e. redox potential differences) (32, 36). However, if these tunneling timescales are applied to the crystal structure of cSO, then IET through the 32 Å distance between the Mo and Fe centers should proceed on a timescale of seconds, rather than the millisecond times that are found experimentally (17, 44). Thus, the results for SO imply that the distance between the Fe and Mo centers during IET is much less than the 32 Å separation found in the crystal structure (16).

Feng et al. (17) showed that the IET rate constant in cSO decreased with increasing solvent viscosity. They proposed that interdomain motion that decreases the Mo to Fe distance is essential for rapid IET and that the flexible tether linking the two domains of SO facilitates this motion. Steady-state kinetics and electron paramagnetic resonance (EPR) measurements on SO were also consistent with this hypothesis (17).

Kawatsu and Beratan have used a computational model to explore the mechanisms of IET in proteins such as SO, where domains containing two cofactors are linked by a flexible tether (45). They found that the constrained conformational flexibility of the tether introduces an entropic component to the effective donor–acceptor interaction potential that produces a kinetic regime intermediate between “unimolecular” and “bimolecular”. Their calculations predicted that for SO the tether length may control the transition between the electron tunneling and diffusion-limited regimes.

Figure 1 shows the tether sequences for chicken and human SO. To date, there have been no investigations of the role of specific amino acids in the tether on the reactivity and spectroscopic properties of SO. Here, we have used mutagenesis of the tether of HSO to increase its conformational flexibility (P105A and P111A) and to decrease its length (deletion of the non-conserved amino acids, K108, V109, A110, T112 and V113). The effects of these modifications of the tether on the IET and steady-state kinetics, as well as on the EPR spectra of HSO are described below.

Materials and Methods

Site-directed Mutagenesis

Expression plasmids of HSO mutants were constructed using the pTG918 plasmid via the Quick Change Site-Directed Mutagenesis protocol (Stratagene) and the primers are listed in the (Supporting Information Table S1). The mutations were verified by sequence analysis performed at the Sequetech Corporation DNA Analysis facility in Mountain View, California. Recombinant ΔK108V109A110 (ΔKVA), ΔK108V109A110T112 (ΔKVAT) and ΔK108V109A110T112V113 (ΔKVATV) HSO are mutant proteins in which the specific amino acids named were deleted from the tether.

Protein Overexpression and Purification

Recombinant P105A, P111A, P105A/P111A, and ΔKVA, ΔKVAT and ΔKVATV deletion HSO mutants were purified as previously described (46, 47) with the following modifications. After the Phenyl Sepharose column (GE Healthcare), fractions exhibiting an A413/A280 ratio of 0.80 or greater were pooled and further purified using a Superdex 200 column (GE Healthcare). Fractions exhibiting an A413/A280 ratio of 0.96 or greater were then pooled and used in the experiments described in this study. The molybdenum content of purified SO proteins was determined using an IRIS Advantage Inductively Coupled Plasma Emission Spectrometer from the Jarrell Ash Corporation (see Supporting Information). Enzyme concentrations were determined by using a molar extinction coefficient of 113, 000 M−1 cm−1 at 413 nm for oxidized human SO (14).

Laser Flash Photolysis

Laser flash photolysis experiments were performed anaerobically on 0.30 mL solutions containing ~90 µM 5-deazariboflavin (dRF) and 0.5 mM freshly prepared semicarbazide as a sacrificial reductant. The methodologies used to obtain rate and equilibrium constants for IET in SO have been described previously (48) and are summarized below. The laser flash photolysis apparatus system has been extensively described (49) as has been the basic photochemical process by which 5-deazariboflavin semiquinone (dRFH•) is generated by reaction between triplet state dRF and the sacrificial reductant and used to reduce redox-active proteins (eqs. 2–5) (50–52).

| (2) |

| (3) |

| (4) |

| (5) |

The IET rate constant can be calculated by fitting the heme reoxidation curve with an exponential function (eq. 6) where the IET rate constant is the sum of the forward and the reverse electron transfer rate constants (kf and kr, respectively, in eq. 7).

| (6) |

| (7) |

The equilibrium constant can then be calculated using the parameters a and b, which are determined from the kinetic traces. A0 is the absorbance extrapolated to t = 0, assuming that the photochemically-induced reduction of SO is instantaneous.

| (8) |

| (9) |

| (10) |

The forward and reverse rate constants (kf and kr, respectively) of IET can then be calculated from the equilibrium constant (eq. 10), thereby providing quantitative information about interdomain electron transfer in the enzyme. Note that kf in these flash photolysis experiments is actually the reverse of the net physiological IET direction.

Steady State Assays

Steady-state kinetic studies were performed aerobically in a Varian Cary-300 spectrophotometer. Initial velocities were determined by following the reduction of a freshly prepared oxidized cyt c (horse heart, Sigma) solution at 550 nm, using an extinction coefficient change of 19, 630 M−1 cm−1 (8). SO was routinely assayed at 25°C in 20 mM Tris pH 8.0, titrated with acetic acid. The steady-state kinetic pH profile study was conducted using a saturating concentration of cyt c , 400 µM (10-fold greater than Km) and varying the concentration of sulfite, between 2 µM and 200 µM. Also, the steady-state kinetic profile to obtain the Km for cyt c was studied using saturating concentrations of sulfite, varying cyt c between 3 µM and 200 µM.

Spectroelectrochemistry

Wild type (wt) HSO and ΔKVATV HSO were used at enzyme concentrations ranging from 350 to 370 µM. Methods for spectroelectrochemical measurements of the heme reduction potential utilized the same instrumentation and the same type of reference electrode (Ag/AgCl, Em = −205 mV vs. SHE) as described previously (53, 54). Protein solutions for electrochemical studies were prepared in 100 mM phosphate buffer at pH 7.5 containing 15 electrochemical mediators selected to cover a wide potential titration range; 40 µM each of N,N-dimethyl-1,4-phenylenediamine, N,N-diethyl-2-methyl-1,4-phenylenediamine, 1,1’-dimethylferrocene, tetrachlorobenzoquinone, tetramethyl-p-phenylenediamine, 2,6-dichlorophenolindophenol, 1,2-naphthoquinone, trimethylhydroquinone, Hexaammineruthenium chloride, 2-methyl-1,4-naphthalenedione, 2-hydroxy-1,4-naphthoquinone, anthraquinone-2-sulfonate, neutral red, benzyl viologen, and methyl viologen (all purchased from Aldrich) were used (55). To minimize the final sample volume used in each experiment the void volume between the reference electrode and the optical window was filled with 100 mM phosphate buffer at pH 7.5 containing 5% high strength agarose (Bio-Rad). Since the ratio of oxidized to reduced forms of each redox species is directly related to the absorbances of the optical spectra via Beer’s law (assuming the extinction coefficients of the reduced and oxidized species are different at the chosen wavelength), the change in absorbance with respect to applied potential can be fit to the Nernst equation (eq. 11) using the nonlinear-leastsquares fitting algorithm in the software Origin©.

| (11) |

where Eapp is the applied potential, E0 is the midpoint potential determined from these data, and [Ox] and [Red] are, respectively, the concentrations of the Fe(III) and Fe(II) states of the b5 heme of HSO.

Mo EPR spectroscopy experiments

EPR samples of wt, ΔKVA, ΔKVAT and ΔKVATV (0.5–0.7 mM HSO) at pH 5.8 were prepared in 100 mM Bis-Tris buffer containing 100 mM NaCl (56). For high-pH (pH 9.0) samples 100 M Bis-Tris Propane buffer was employed. The enzyme samples were reduced with a 20-fold excess of sodium sulfite and immediately frozen in liquid nitrogen. The continuous wave (CW) X-band EPR spectra were obtained on a Bruker ESP-300 spectrometer at 77 K.

Results and Discussion

Laser Flash Photolysis Kinetics of Proline to Alanine Mutants

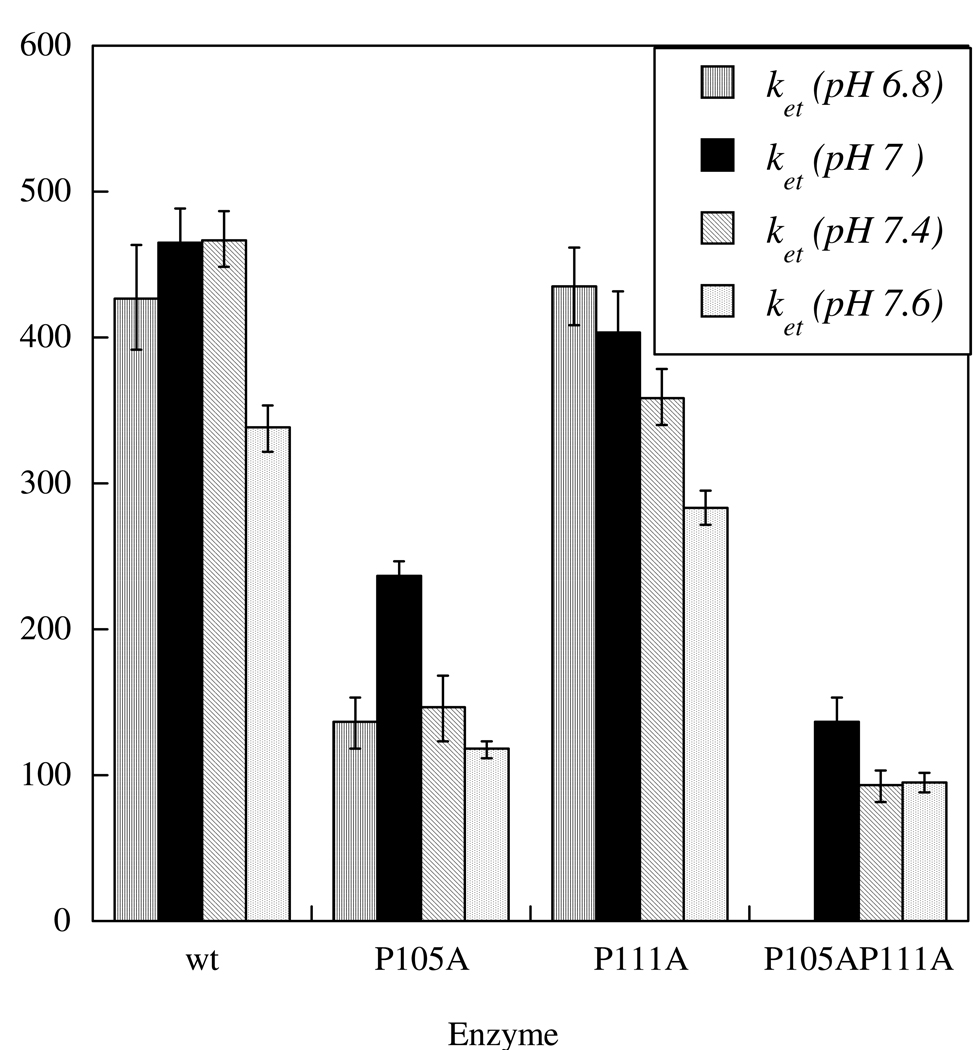

The tether of cSO has a very different sequence from that of HSO (Figure 1). Furthermore, previous laser flash photolysis studies have shown that cSO has an IET rate constant (ket) twice that of HSO (11). This result could be due to greater flexibility of the tether in cSO, which has four alanine residues compared to one for HSO (although cSO has one more proline residue). To test this hypothesis, we mutated two of the more rigid proline residues (P105 and P111) to alanines in the tether of HSO to study the effects of increased flexibility on the IET kinetics. We also made the double mutant, P105A/P111A. The P105 residue is found at the N-terminal end of the tether, next to the heme, and P111 is found at the center of the tether. While P105 is conserved within cSO and HSO, P111 is not. However, P111 is conserved within other mammalian forms. Figure 2 illustrates the dependence of ket on pH and mutation. The data show that the P105A mutation decreases ket by approximately 3-fold (467 ± 19 s−1 at 7.4 for wt vs. 146 ± 23 s−1 for P105A). In contrast, the P111A mutation has only a minimal effect on ket. The IET rate constants for the P105A/P111A double mutant are similar to those for P105A, suggesting that the P105A change is the primary cause of the decrease in IET that is observed in this mutant.

Figure 2.

IET Rate Constants for the Proline to Alanine Tether Mutants

The equilibrium constants (Keq) for these mutants at various pH values are given in Table 1. For wt HSO, Keq increases with increasing pH. This trend is also observed for the P111A mutant, but not for the P105A and P105A/P111A mutants. However, the pH dependence of Keq for the P105A and P105A/P111A mutants is similar. From the kinetic analysis of IET in these P to A mutants, we infer that mutation of P111, which is in the middle of the tether and not conserved across species, has little effect on the IET kinetics. However, the large decrease in IET kinetics for P105A suggest that this conserved proline, which is adjacent to the heme domain, promotes a tether conformation that results in optimal IET.

Table 1.

Laser Flash Photolysis Equilibrium Constants for Proline to Alanine Tether Mutants

| pH 6.8 | pH 7.0 | pH 7.4 | pH 7.61 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| wt HSO | 0.26 ± 0.01 | 0.35 ± 0.01 | 0.46 ± 0.02 | 0.45 ± 0.02 |

| P105A | 0.22 ± 0.01 | 0.38 ± 0.02 | 0.19 ± 0.02 | 0.44 ± 0.03 |

| P111A | 0.28 ± 0.02 | 0.36 ± 0.01 | 0.43 ± 0.01 | 0.44 ± 0.02 |

| P105A/P111A | *ND | 0.19 ± 0.01 | 0.33 ± 0.02 | 0.34 ± 0.01 |

no heme reoxidation was observed.

Steady-state kinetics of Proline to Alanine Mutations

The steady-state oxidation of sulfite to sulfate as catalyzed by HSO using cyt c as the electron acceptor yields plots of initial velocity versus substrate concentration that display typical saturation kinetics (not shown). The standard Michaelis-Menten parameters at pH 8.0 are given in Table 2. The largest effect observed is on the Michaelis-Menten constants (Km) for P111A and P105A/P111A, which are approximately five-fold higher than for wt. This increase in Km also affects the catalytic efficiency (kcat/Km) of the enzyme, causing a 30% decrease in this parameter. From these results we conclude that the P111A mutation may affect the binding of sulfite to the enzyme. Also, the steady-state data reveal that the kcat values for each of these mutations are much smaller than ket. Therefore, the IET process is not rate-limiting in catalysis, as is also true of the wt enzyme.

Table 2.

Steady-State Kinetics Data for Proline to Alanine Tether Mutantsa

| Enzyme | kcat (s−1) |

Kmsulfite (µM) |

kcat /Kmsulfite (M−1s−1) |

|---|---|---|---|

| wt HSOb | 26.9 ± 0.5 | 11.1 ± 0.4 | 2.4 × 106 |

| P105A | 39 ± 2 | 6 ± 1 | 6.1 × 106 |

| P111A | 50 ± 3 | 33 ± 5 | 1.5 × 106 |

| P105A / P111A | 46 ± 2 | 32 ± 3 | 1.5 × 106 |

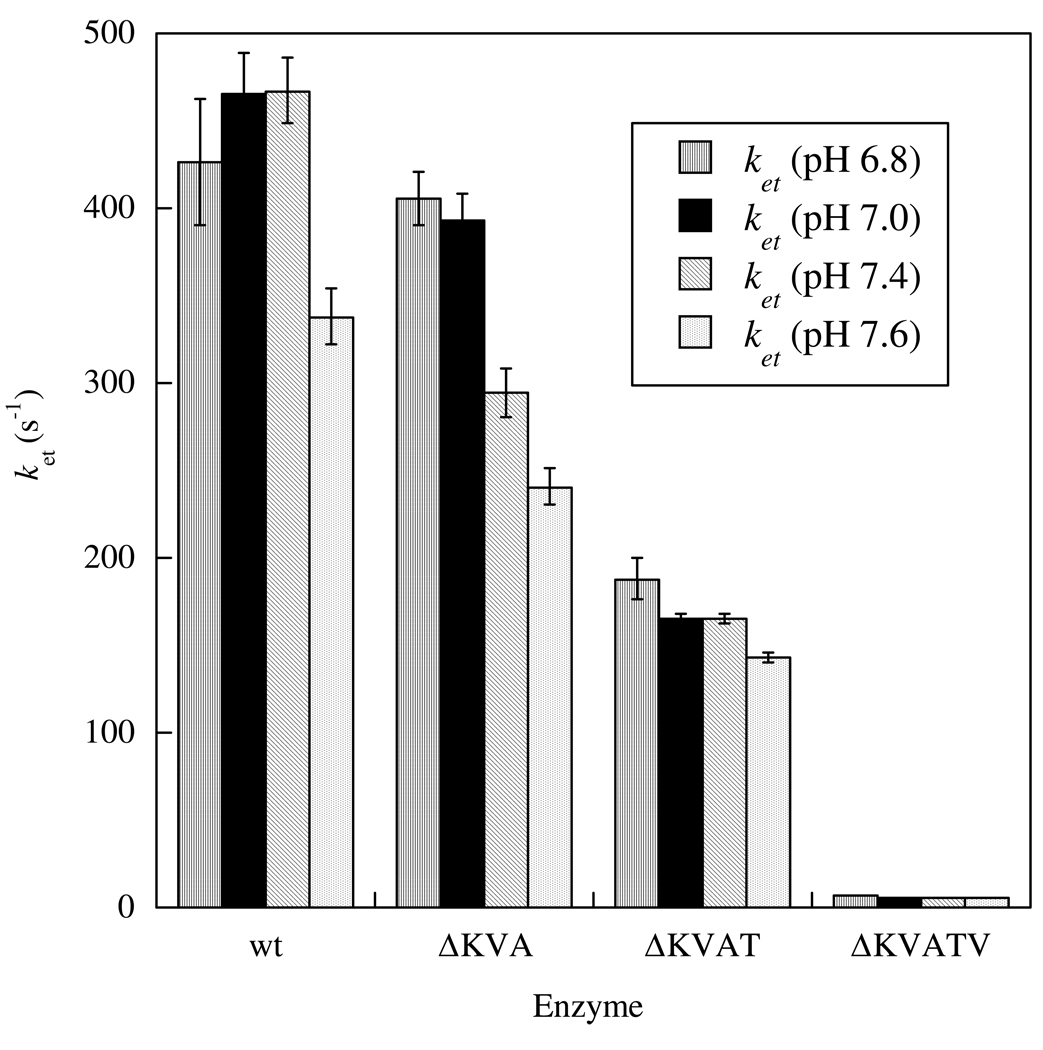

Laser Flash Photolysis Kinetics of Deletion Mutants

Deletions of non-conserved amino acids from the tether result in steadily decreasing IET rate constants, from 467 ± 19 s−1 in wt HSO down to 5.59 ± 0.03 s−1 in ΔKVATV HSO (see Methods and Materials for abbreviations of deletion mutants) at pH 7.4 (Figure 3). Interestingly, the largest decrease occurs on deletion of the fifth residue. Additionally, all three deletion mutants show decreasing IET rates with increasing pH from 6.8 to 7.6. Keq is significantly larger for ΔKVATV HSO (0.91 ± 0.03; Table 3) in comparison to the wt HSO value (0.46 ± 0.02) and the other tether deletion mutants, but all the enzymes seem to have a maximal Keq around pH 7.4. The large increase in Keq for ΔKVATV could be the result of changes in the potential of the molybdenum or heme centers. To test this possibility, we have also performed spectroelectrochemistry studies on wt and ΔKVATV HSO (see below).

Figure 3.

IET Rate Constants for Tether Deletion Mutants.

Table 3.

Laser Flash Photolysis Equilibrium Constants for Tether Deletion Mutants

| pH 6.8 | pH 7.0 | pH 7.4 | pH 7.61 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| wt HSO | 0.26 ± 0.01 | 0.35 ± 0.01 | 0.46 ± 0.02 | 0.45 ± 0.02 |

| ΔKVA | 0.36 ± 0.01 | 0.35 ± 0.01 | 0.50 ± 0.02 | 0.54 ± 0.02 |

| ΔKVAT | 0.41 ± 0.02 | 0.35 ± 0.03 | 0.56 ± 0.01 | 0.53 ± 0.03 |

| ΔKVATV | 0.59 ± 0.01 | 0.63 ± 0.02 | 0.91 ± 0.03 | 0.87 ± 0.03 |

Steady-state kinetics of Deletion Mutations

Table 4 gives the steady-state data for the deletion mutants. Whereas the catalytic turnover numbers for the first two deletion mutants, ΔKVA and ΔKVAT HSO, are slightly increased in comparison to the wt enzyme, the turnover number for ΔKVATV HSO (10.6 ± 0.3 s−1) is approximately one-third that of wt (26.9 ± 0.5) at pH 8.0. Kmsulfite follows a similar trend, although it increases 4-fold for ΔKVA HSO in comparison to wt, and it decreases dramatically in ΔKVATV. In addition, KMcyt c is larger for all of the deletion mutants. Note that the turnover number for the ΔKVATV mutant is about the same as the IET rate constant for this mutant (see above). This suggests that for ΔKVATV, IET has become rate-limiting for catalysis.

Table 4.

Steady-State Kinetics Data for Tether Deletion Mutantsa

| Enzyme |

kcat (s−1) |

Kmsulfite (µM) |

kcat/Kmsulfite (M−1s−1) |

|---|---|---|---|

| wt HSOb | 27 ± 1 | 11.1 ± 0.4 | 2.4 × 106 |

| ΔKVA HSO | 40 ± 2 | 42 ± 4 | 9.5 × 105 |

| ΔKVAT HSO | 35 ± 2 | 26 ± 2 | 1.4 × 106 |

| ΔKVATV HSO | 10.6 ± 0.3 | 2.6 ± 0.4 | 4.1 × 106 |

Electrochemistry

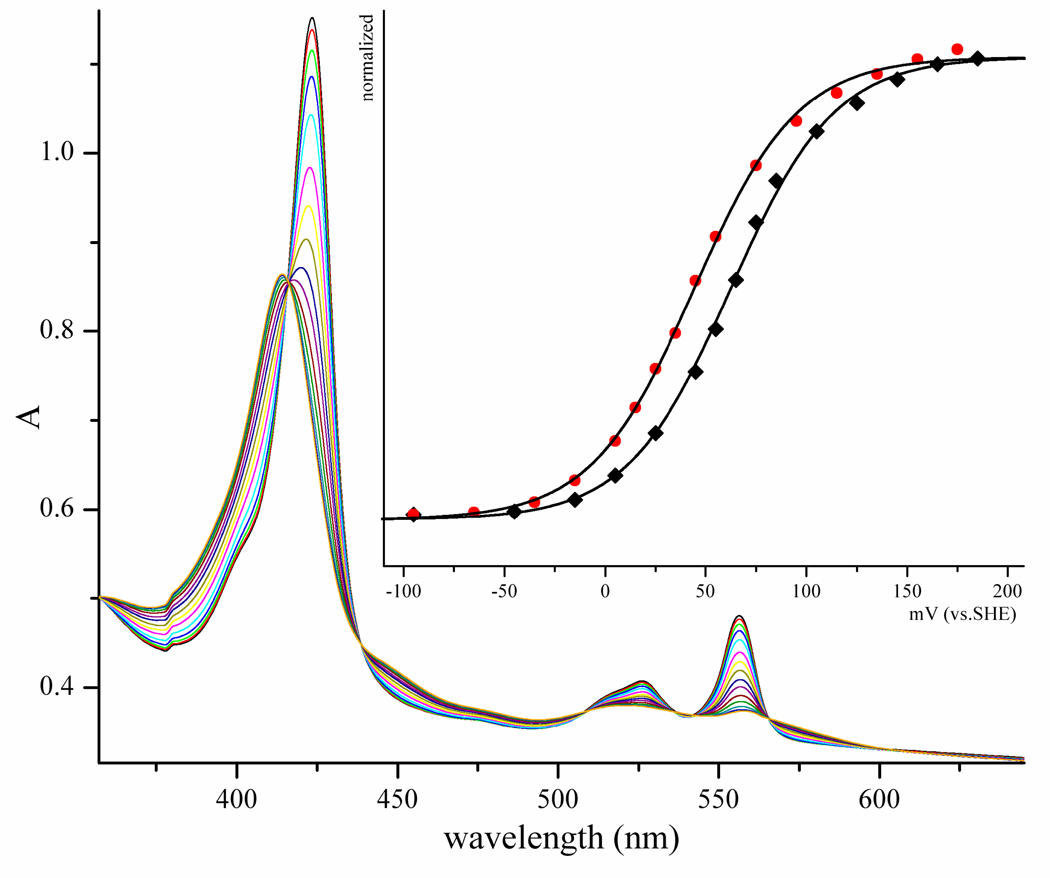

As noted above, the laser flash photolysis data for ΔKVATV resulted in Keq values that were approximately 0.91, compared to 0.46 for the wt. Consequently, the midpoint potential difference between the heme and molybdenum must have changed in this mutant. To confirm this, we have performed spectroelectrochemistry studies to determine the Fe(III/II) potentials for wt and ΔKVATV HSO. The corresponding midpoint potentials vs. SHE are +62 ± 2 mV for wt HSO and +44 ± 2 mV for ΔKVATV HSO (Figure 4, Table 5). Thus, the Fe(III/II) potential for ΔKVATV HSO is 18 ± 3 mV more negative than wt, supporting the laser flash photolysis kinetic data and favoring the Fe(III)/Mo(V) species in eq. 5. Using the Keq value from the laser flash photolysis data and the heme potential, the potential of the molybdenum center can be calculated as well. The calculated potentials of the Mo(VI)/Mo(V) couple for ΔKVATV and wt HSO are +41 ± 2 and +42 ± 2 mV, respectively (Table 5). Therefore, we conclude that the change in Keq for ΔKVATV is primarily due to a change in the potential of the heme. Perhaps the deletion of five amino acids from the tether changes the exposure of the heme to solvent, thereby causing a shift in the potential and in Keq.

Figure 4.

Spectroelectrochemical titration of the b5 heme of wild-type HSO at pH 7.5 and 27°C. The inset shows the fit of the data to eq. 11 at 413 nm (53); black = wt; red = ΔKVATV mutation.

Table 5.

Electrochemical Midpoint Potentials of HSO cofactorsa

We have also used spectroelectrochemistry to measure the Fe(III/II) potential of the P105A mutant which shows much slower rates of IET compared to wt, but similar Keq values (Figure 2, Table 1). Table 5 shows that the Fe(III/II) potential for P105A is essentially identical to wt, as is the calculated Mo(VI/V) potential. Thus, the P105A mutation does not change the thermodynamic driving force for IET (as seen from Keq) or the individual potentials of the two redox centers. Therefore, we conclude that the 2–4 fold decrease in ket for P105A compared to wt (Figure 2) reflects differences in their IET pathways.

Electron Paramagnetic Resonance Spectra

The CW EPR spectra of the all of the tether variants of HSO were essentially identical to wt HSO. Together with the similarity in potentials of the Mo centers (see above), the EPR spectra indicate that no changes in the Mo environment were caused by the tether deletions or P → A mutations. Specifically, at pH 5.8 in the presence of 100 mM chloride the low-pH (lpH) form of the Mo(V) center was generated, characterized by the principal g-values of 2.004, 1.973 and 1.966 with proton hyperfine splittings of 0.8, 0.6 and 1.2 mT at the EPR turning points (60, 61). At pH 9 the so-called high-pH (hpH) form of the Mo(V) center was obtained, characterized by the principal g-values of 1.988, 1.964 and 1.953 (60, 61).

Conclusion

This work presents the first experimental investigation of the kinetic effects of altering the nature of the tether connecting the heme and molybdenum domains of HSO. Changing the flexibility of the tether has been explored by replacing two Prolines by Alanines. The P105A substitution, which is adjacent to the heme domain and presumably would increase tether flexibility, leads to a marked decrease in IET rates, whereas the P111A substitution in the center of the tether has little effect on the IET kinetics. These observations suggest that no generalizations can be made regarding the kinetic effect of flexibility, and that the rigidity of P105 may favor a tether conformation that results in more facile IET. Presumably this is a consequence of a more favorable orientation between the heme and the Mo centers during the electron transfer process. We conclude that these results do not provide support for a role of tether flexibility in causing the faster IET rate in chicken vs. human SO.

Deletion of amino acids from the tether resulted in pronounced decreases in IET rates. For the ΔKVATV deletion IET became rate limiting. Decreasing the length of the tether can influence the docking of the heme domain onto the molybdenum domain, thereby changing the distance and relative orientation of the two redox centers. This is the probable reason for the decrease in ket. In addition, shortening the tether by five amino acids decreased the Fe(III/II) potential of the b5-heme center by 20 mV without affecting the molybdenum potential (Table 5). The similarity of the EPR spectra of all of the variants to that of wt HSO further indicates that the geometry of molybdenum active site remains unchanged. The small change in the Fe(III/II) potential could be due to increased exposure of the heme to solvent in this variant, and translates to a decrease in the driving force (ΔG0) for reaction (5) of only ~2 kJ/mol. It seems unlikely that such a relatively small change in the driving force could account for the 70-fold decrease in ket observed in the ΔKVATV deletion mutant. The reorganization energy of this mutant is expected to differ little from wt, and previous studies of the relationship between ket and ΔG0 in the amicyanin-cytochrome c551i mutant system showed that a 145-fold decrease of ket involved a decrease in driving force of 19 kJ/mol (62), ten times larger than that found in this work.

We conclude that the results presented here point to a critical role of the tether in facilitating the IET reaction between the heme and molybdenum centers. This supports the contention that a conformational transition is required to bring these two centers into a suitable mutual orientation (17). While “simple docking” within a narrow range of orientations is a reasonable conclusion for SO, the new “dynamic docking” paradigm for protein-protein complexes proposed by Hoffman and coworkers from recent studies on Zn-myoglobin and cytochrome b5 must also be considered (63). A key feature of this paradigm is the presence of numerous weakly bound conformations, some of which greatly facilitate electron transfer (63). Thus, for SO it is possible that ket is the result of many averaged conformations of SO, as well as the overall driving force and reorganization energy (62). Finally, this study provides experimental data for testing computational models for electron transfer in a two domain enzyme (45). However, such calculations are beyond the scope of the present work.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

We are indebted to Professor K. V. Rajagopalan for providing the pTG918 plasmid containing the HSO gene for preparing recombinant human sulfite oxidase and the protocols for purifying the enzyme. We are grateful to Professor F. Ann Walker for the use of equipment and for helpful discussions. We thank Drs. Heather Wilson, John Yang and Arnold Raitsimring for helpful discussions.

Abbreviations

- SO

sulfite oxidase

- dRF

5-deazariboflavin

- cSO

chicken sulfite oxidase

- HSO

human sulfite oxidase

- cyt c

cytochrome c

- IET

intramolecular electron transfer

- ket

electron transfer rate constant

- Keq

equilibrium constant for intramolecular electron transfer

- kf and kr

microscopic rate constants for the forward and reverse directions, respectively, of intramolecular electron transfer

- Moco

molybdopterin cofactor

- wt

wild type

Footnotes

This research was supported by NIH Grant GM-037773 (to JHE); Ruth L. Kirchstein-NIH Fellowship 1F32GM082136-01 (to KJW)

Supporting Information Available: Primer design; iron to molybdenum ratios determined using inductively coupled plasma; and laser flash photolysis results for proline to alanine and deletion mutants. This material is available free of charge via the Internet at http://pubs.acs.org.

References

- 1.Hille R. The Mononuclear Molybdenum Enzymes. Chem. Rev. 1996;96:2757–2816. doi: 10.1021/cr950061t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rajagopalan KV, Johnson JL. Sulfite Oxidase. In: Creighton TE, editor. Wiley Encyclopedia of Molecular Medicine. New York: Wiley; 2002. pp. 3048–3051. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kisker C. Sulfite Oxidase. In: Messerschmidt A, Huber R, Poulos T, Wieghardt K, editors. Handbook of Metalloproteins. New York: John Wiley and Sons, Ltd; 2001. pp. 1121–1135. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Schindelin H, Kisker C, Rajagopalan KV. Molybdopterin from Molybdenum and Tungsten Enzymes. Adv. Protein Chem. 2001;58:47–94. doi: 10.1016/s0065-3233(01)58002-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cohen HJ, Betcher-Lange S, Kessler DL, Rajagopalan KV. Hepatic Sulfite Oxidase. Congruency in Mitochondria of Prosthetic Groups and Activity. J. Biol. Chem. 1972;247:7759–7766. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kessler DL, Johnson JL, Cohen HJ, Rajagopalan KV. Visualization of Hepatic Sulfite Oxidase in Crude Tissue Preparations by Electron Paramagnetic Resonance Spectroscopy. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 1974;334:86–96. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sullivan EP, Jr, Hazzard JT, Tollin G, Enemark JH. Electron Transfer in Sulfite Oxidase: Effects of pH and Anions on Transient Kinetics. Biochemistry. 1993;32:12465–12470. doi: 10.1021/bi00097a026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Brody MS, Hille R. The Kinetic Behavior of Chicken Liver Sulfite Oxidase. Biochemistry. 1999;38:6668–6677. doi: 10.1021/bi9902539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kessler DL, Rajagopalan KV. Purification and Properties of Sulfite Oxidase from Chicken Liver. Presence of Molybdenum in Sulfite Oxidase from Diverse Sources. J. Biol. Chem. 1972;247:6566–6573. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Garrett RM, Rajagopalan KV. Molecular Cloning of Rat Liver Sulfite Oxidase. Expression of a Eukaryotic Mo-Pterin-Containing Enzyme in Escherichia coli. J. Biol. Chem. 1994;269:272–276. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Feng C, Wilson HL, Hurley JK, Hazzard JT, Tollin G, Rajagopalan KV, Enemark JH. Role of Conserved Tyrosine 343 in Intramolecular Electron Transfer in Human Sulfite Oxidase. J. Biol. Chem. 2003;278:2913–2920. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M210374200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Feng C, Wilson HL, Hurley JK, Hazzard JT, Tollin G, Rajagopalan KV, Enemark JH. Essential Role of Conserved Arginine 160 in Intramolecular Electron Transfer in Human Sulfite Oxidase. Biochemistry. 2003;42:12235–12242. doi: 10.1021/bi0350194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Feng C, Wilson HL, Tollin G, Astashkin AV, Hazzard JT, Rajagopalan KV, Enemark JH. The Pathogenic Human Sulfite Oxidase Mutants G473D and A208D are Defective in Intramolecular Electron Transfer. Biochemistry. 2005;44:13734–13743. doi: 10.1021/bi050907f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wilson HL, Rajagopalan KV. The Role of Tyrosine 343 in Substrate Binding and Catalysis by Human Sulfite Oxidase. J. Biol. Chem. 2004;279:15105–15113. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M314288200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wilson HL, Wilkinson SR, Rajagopalan KV. The G473D Mutation Impairs Dimerization and Catalysis in Human Sulfite Oxidase. Biochemistry. 2006;45:2149–2160. doi: 10.1021/bi051609l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kisker C, Schindelin H, Pacheco A, Wehbi WA, Garrett RM, Rajagopalan KV, Enemark JH, Rees DC. Molecular Basis of Sulfite Oxidase Deficiency from the Structure of Sulfite Oxidase. Cell. 1997;91:973–983. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80488-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Feng C, Kedia RV, Hazzard JT, Hurley JK, Tollin G, Enemark JH. Effect of Solution Viscosity on Intramolecular Electron Transfer in Sulfite Oxidase. Biochemistry. 2002;41:5816–5821. doi: 10.1021/bi016059f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Winkler JR, Nocera DG, Yocom KM, Bordignon E, Gray HB. Electron - Transfer Kinetics of Pentaammineruthenium(III)(histidine-33)-ferricytochrome c. Measurement of the Rate of Intramolecular Electron Transfer Between Redox Centers Separated by 15 Å in a Protein. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1982;104:5798–5800. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Moser CC, Keske JM, Warncke K, Farid RS, Dutton PL. Nature of Biological Electron Transfer. Nature. 1992;355:796–802. doi: 10.1038/355796a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Pasman P, Koper NW, Verhoeven JW. Photoinduced Long-Range Electron Transfer in Rigid Bichromophoric Molecules. Rec Trav Chim. 1982;101:363–364. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Calcaterra LT, Closs GL, Miller JR. Intramolecular Electron Transfer in Radical Ions Over Long Distances Across Rigid Saturated Hydrocarbon Spacers. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1983;105:670–671. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Freed KF. Role of Intramolecular Vibrational Relaxation on Electron Transfer Rates-Application to Pentaammineruthenium (III) (histidine-33)-ferrcytochrome c. Chem. Phys. Lett. 1983;97:489–493. [Google Scholar]

- 23.McGourty JL, Blough NV, Hoffman BM. Electron Transfer at Crystallographically Known Long Distances (25 Å) in [Zn(II), Fe(III)] Hybrid Hemoglobin. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1983;105:4470–4472. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Overfield RE, Scherz A, Kaufmann KJ, Wasielewski MR. Photoinduced Electron-Transfer Reactions in a Chlorophyllide-pheophorbide cyclophane. A Model for Photosynthetic Reaction centers. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1983;105:5747–5752. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Simolo KP, McLendon GL, Mauk MR, Mauk AG. Photoinduced Electron Transfer Within a Protein-Protein Complex Formed Between Physiological Redox Partners-Reduction of Ferricytochrome b5 by the Hemoglobin Derivative α2Zn-α2FeIII(CN) J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1984;106:5012–5013. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gunner MR, Robertson DE, Dutton PL. Kinetic Studies on the Reaction Center Protein from Rhodopseudomonas sphaeroides- the Temperature and Free-energy Dependence of Electron Transfer Between Various Quinones in the QA Site and the Oxidized Bacteriochlorophyll Dimer. J. Phys. Chem. 1986;90:3783–3795. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Heitele H, Michel-Beyerle ME, Finckh P. Electron Transfer Through Intramolecular Bridges in Donor/acceptor Systems. Chem. Phys. Lett. 1987;134:273–278. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Closs GL, Miller JR. Intramolecular Long-Distance Electron Transfer in Organic Molecules. Science. 1988;240:440–447. doi: 10.1126/science.240.4851.440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kuki A, Wolynes PG. Electron Tunneling Paths in Proteins. Science. 1987;236:1647–1652. doi: 10.1126/science.3603005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lawson JM, Craig DC, Paddon-Row MN, Kroon J, Verhoeven JW. Through-bond Modulation of Intramolecular Electron Transfer in Rigidly Linked Donor-Acceptor Systems. Chem. Phys. Lett. 1989;164:120–125. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Evenson JW, Karplus M. Effective Coupling in Biological Electron Transfer: Exponential or Complex Distance Dependence. Science. 1993;262:1247–1249. doi: 10.1126/science.8235654. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Gray HB, Winkler JR. Electron Transfer in Proteins. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 1996;65:537–561. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bi.65.070196.002541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kuzetsov AM, Ulstrup J. Electron Transfer in Chemistry and Biology: An Introduction to the Theory. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley and Sons, Inc.; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Skourtis SS, Beratan DN. Electron Transfer Mechanisms. Curr. Opin. Chem. Biol. 1998;2:235–243. doi: 10.1016/s1367-5931(98)80065-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Verhoeven JW. From Close Contact to Long-Range Intramolecular Electron Transfer. AdChP. 1999;106:603–644. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Winkler JR. Electron Tunneling Pathways in Proteins. Curr. Opin. Chem. Biol. 2000;4:192–198. doi: 10.1016/s1367-5931(99)00074-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Gray HB, Winkler JR, editors. The Porphyrin Handbook-Bioinorganic and Bioorganic Chemistry. Vol. 11. San Diego, CA: Academic Press; 2003. Heme Protein Dynamics: Electron Tunneling and Redox Triggered Folding. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Gray HB, Winkler JR. Electron Transfer in Biological Systems. In: Balzani V, editor. Electron Transfer in Chemistry. vol. III. Weinheim: Wiley-VCH; 2001. pp. 1–175. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Paddon-Row MN. Superexchange-mediated Charge Separation and Charge Recombination in Covalently Linked Donor-bridge-acceptor Systems. Aust. J. Chem. 2003;56:729–748. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hopfield JJ. Electron Transfer Between Biological Molecules by Thermally Activated Tunneling. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 1974;71:3640–3644. doi: 10.1073/pnas.71.9.3640. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Beratan DN, Betts JN, Onuchic JN. Protein Electron Transfer Rates Set by the Bridging Secondary and Tertiary Structure. Science. 1991;252:1285–1288. doi: 10.1126/science.1656523. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Gray HB, Winkler JR. Electron Tunneling Through Proteins. Quart Rev. Biophys. 2003;36:341–372. doi: 10.1017/s0033583503003913. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Winkler JR, Wittung-Stafshede p, Lekner J, Malmstrom BG, Gray HB. Effects of Folding on Metalloprotein Active Sites. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 1997;94:4246–4249. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.9.4246. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Feng C, Tollin G, Enemark JH. Sulfite Oxidizing Enzymes. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 2007;1774:527–539. doi: 10.1016/j.bbapap.2007.03.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kawatsu T, Beratan DN. Electron Transfer Between Cofactors in Protein Domains Linked by a Flexible Tether. Chem. Phys. 2006;326:259–269. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Temple CA, Graf TN, Rajagopalan KV. Optimization of Expression of Human Sulfite Oxidase and its Molybdenum Domain. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 2000;383:281–287. doi: 10.1006/abbi.2000.2089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Garrett RM, Rajagopalan KV. Site-directed Mutagenesis of Recombinant Sulfite Oxidase: Identification of Cysteine 207 as a Ligand of Molybdenum. J. Biol. Chem. 1996;271:7387–7391. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Pacheco A, Hazzard JT, Tollin G, Enemark JH. The pH Dependence of Intramolecular Electron Transfer Rates in Sulfite Oxidase at High and Low Anion Concentrations. J. Biol. Inorg. Chem. 1999;4:390–401. doi: 10.1007/s007750050325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Hurley JK, Weber-Main AM, Stankovich MT, Benning MM, Thoden JB, Vanhooke JL, Holden HM, Chae YK, Xia B, Cheng H, Markley JL, Martinez-Julvez M, Gomez-Moreno C, Schmetis JL, Tollin G. Structure–Function Relationships in Anabaena Ferredoxin: Correlations between X-ray Crystal Structures, Reduction Potentials, and Rate Constants of Electron Transfer to Ferredoxin:NADP+ Reductase for Site-Specific Ferredoxin Mutants. Biochemistry. 1997;36:11100–11117. doi: 10.1021/bi9709001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Tollin G, Hurley JK, Hazzard JT, Meyer TE. Use of Laser Flash Photolysis Time-Resolved Spectrophotometry to Investigate Interprotein and Intraprotein Electron Transfer Mechanisms. Biophys. Chem. 1993;48:259–279. doi: 10.1016/0301-4622(93)85014-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Tollin G. Use of Flavin Photochemistry to Probe Intraprotein and Interprotein Electron Transfer Mechanisms. J. Bioenerg. Biomembr. 1995;27:303–309. doi: 10.1007/BF02110100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Tollin G. Interprotein and Intraprotein Electron Transfer Mechanisms. In: Balzani V, editor. Electron Transfer in Chemistry. Vol. IV. Weinheim: Wiley-VCH; 2001. pp. 202–231. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Ding XD, Weichsel A, Andersen JF, Shokhireva TKh, Balfour C, Pierik AJ, Averill BA, Montfort WR, Walker FA. Nitric Oxide Binding to the Ferri- and Ferroheme States of Nitrophorin 1, A Reversible NO-Binding Heme Protein from the Saliva of the Blood-Sucking Insect, Rhodnius prolixus. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1999;121:128–138. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Berry RE, Shokhireva TKh, Filippov I, Shokhirev MN, Zhang H, Walker FA. Effect of the N-Terminus on Heme Cavity Structure, Ligand Equilibrium, Rate Constants, and Reduction Potentials of Nitrophorin 2 from Rhodnius prolixus. Biochemistry. 2007;46:6830–6843. doi: 10.1021/bi7002263. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Hellwig P, Bwhr J, Ostermeier C, Oliver-Matthias HR, Pfitzner U, Odenwald A, Ludwig B, Hartmut M, Mantele W. Involvement of Glutamic Acid 278 in the Redox Reaction of the Cytochrome c Oxidase from Paracoccus denitrificans Investigated by FTIR Spectroscopy. Biochemistry. 1998;37:7390–7399. doi: 10.1021/bi9725576. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Klein EL, Astashkin AV, Ganyushin D, Riplinger C, Johnson-Winters K, Neese F, Enemark JH. Direct Detection and Characterization of Chloride in the Active Site of the Low-pH Form of Sulfite Oxidase Using Electron Spin Echo Envelope Modulation Spectroscopy, Isotopic Labeling, and Density Functional Theory Calculations. Inorg. Chem. 2009;48:4743–4752. doi: 10.1021/ic801787s. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Astashkin AV, Johnson-Winters K, Klein EL, Byrne RS, Hille R, Raitsimring AM, Enemark JH. Direct Demonstration of the Presence of Coordinated Sulfate in the Reaction Pathway of Arabidopsis thaliana Sulfite Oxidase Using 33S Labeling and ESEEM Spectroscopy. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2007;129:14800–14810. doi: 10.1021/ja0704885. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Astashkin AV, Johnson-Winters K, Klein EL, Feng C, Wilson HL, Rajagopalan KV, Raitsimring AM, Enemark JH. Structural Studies of the Molybdenum Center of the Pathogenic R160Q Mutant of Human Sulfite Oxidase by Pulsed EPR Spectroscopy and 17O and 33S Labeling. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2008;130:8471–8480. doi: 10.1021/ja801406f. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Astashkin AV, Hood BL, Feng C, Hille R, Mendel RR, Raitsimring AM, Enemark JH. Structures of the Mo(V) Forms of Sulfite Oxidase from Arabidopsis thaliana by Pulsed EPR Spectroscopy. Biochemistry. 2005;44:13274–13281. doi: 10.1021/bi051220y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Lamy MT, Gutteridge S, Bray RC. Electron-paramagnetic-resonance Parameters of Molybdenum(V) in Sulphite Oxidase from Chicken Liver. Biochem. J. 1980;185:397–403. doi: 10.1042/bj1850397. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Enemark JH, Astashkin AV, Raitsimring AM. Investigation of the Coordination Structures of the Molybdenum(V) Sites of Sulfite Oxidizing Enzymes by Pulsed EPR Spectroscopy. Dalton Trans. 2006:3501–3514. doi: 10.1039/b602919a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Davidson VL. Protein Control of True, Gated, and Coupled Electron Transfer Reactions. Acc. Chem. Res. 2008;41:730–738. doi: 10.1021/ar700252c. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Liang Z, Nocek JM, Huang K, Hayes RT, Kurnikov IV, Beratan DN, Hoffman BM. Dynamic Docking and Electron Transfer between Zn-myoglobin and Cytochrome b5. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2002;124:6849–6859. doi: 10.1021/ja0127032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.