Abstract

Objectives

To assess the rate of intrafamilial transmission of Helicobacter pylori infection in the general population and the role of a family’s social background.

Design

Population survey.

Setting

Campogalliano, a town in northern Italy with about 5000 residents.

Participants

3289 residents, accounting for 416 families.

Main outcome measures

Prevalence of H pylori infection assessed by presence of IgG antibodies to H pylori.

Results

The overall prevalence of H pylori infection was 58%. Children belonging to families with both parents infected had a significantly higher prevalence of H pylori infection (44%) than children from families with only one (30%) or no parents (21%) infected (P<0.001). Multivariate analyses confirmed that children with both parents positive had double the risk of being infected by H pylori than those from families in which both parents were negative. Family social status was independently related to infection in children, with those from blue collar or farming families showing an increased risk of infection compared with children of white collars workers (odds ratio 2.02, 95% confidence interval 1.16 to 3.49).

Conclusions

H pylori infection clusters within families belonging to the same population. Social status may also be a risk factor. This suggests either a person to person transmission or a common source of exposure for H pylori infection.

Key messages

The route of transmission of H pylori is still unknown and most studies have been on selected groups

In this population based study the prevalence of H pylori infection in children was related to parents’ infection

Children whose fathers were blue collar workers or farmers’ families had a significantly increased risk of H pylori infection compared with children of white collar workers.

These findings support person to person transmission of H pylori infection

Further research is needed to assess the role of housing, dietary habits, and other lifestyle factors

Introduction

Helicobacter pylori is considered the main aetiological agent of the most common form of chronic gastritis in the adult population—type B gastritis. Type B gastritis is localised in the antrum and pylorus, whereas type A gastritis, the classic autoimmune gastritis, mainly occurs in the fundus.1–3 H pylori positive chronic gastritis of the antrum has been found to be closely related to duodenal ulcer4–7 and can lead to gastric atrophy, a precursor of gastric cancer.8

Environmental factors, such as socioeconomic and educational state, seem to affect the prevalence of H pylori infection. Infection is consistently higher in Hispanic and black people than in white people and is inversely related to educational level.9

The prevalence of H pylori infection is higher in close communities10,11 and in members of family groups12–25 than in the general population. This may be due to relapses or reinfections between members of the same family.13 Furthermore, the route of transmission of H pylori remains unknown, although most of the evidence supports person to person transmission with colonisation occurring primarily in childhood. Under natural circumstances transmission could be by the oro-oral or faecal-oral routes, but no strong evidence exists to support either route as the primary one, and both may be relevant depending on other factors.26

Most studies of transmission of H pylori infection within families have been conducted on parents and siblings of children referred for symptoms and not on the general population. To avoid this potential selection bias, we studied part of the population of the Dionysos cohort study27 to assess whether children of H pylori infected parents had a higher infection rate then those from families with uninfected parents.

Participants and methods

Family units were identified within the framework of the Dionysos cohort study, which aimed at assessing the prevalence of chronic liver disease in the general population.27 All the subjects enrolled into the study gave written formal consent to participate.

For the H pylori investigation we studied residents aged 12-65 in Campogalliano, Italy (population 4767), one of two towns in the original Dionysos study. In all, 3289 residents (69%) agreed to participate. Agreement was higher among women (71% v 67% of men, NS) and lower among young people, especially those aged 17-35, but not significantly so. Details of the estimation of possible bias in patient accession and the validations of the study have been described.27

We obtained a serum sample for evaluation of IgG antibodies to H pylori from each participant. Serum samples were stored at −20°C until assessment by enzyme linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) (Eurohospital Kit, Trieste, Italy). A cut off antibody titre of 10 μg/ml was used to classify subjects as positive or negative, as recommended by the manufacturer (sensitivity 96%, specificity 93%).28 The same IgG antibody assay has been recently used in another multicentre Italian study and showed a sensitivity of 98% and specificity of 78% when compared with a single Giemsa stained histology specimen.29 To test assay reliability we analysed about 1 in 40 samples twice, with the laboratory blinded to the previous result. Selection for repeat assay was weighted in order to overrepresent samples close to the 10 μg/ml threshold.

The following information was available for each of the 3289 participants: age, sex, family status (father, mother, child, other), and occupation. A family unit was defined as a husband and a wife with at least one child, all living in the same household.

The number of families was 416, representing 1433 of the 3289 cases analysed (43.6%). The median number of members for each family was 3 (range 3-6). Families were divided into three groups according to parents’ H pylori test results: group 1 included families in which both parents were positive; group 2 families in which either the father or mother was positive; and group 3 those with neither parent positive. In addition, families were grouped into three categories according to father’s occupation: “white collar” (when occupation was represented by any type of intellectual work), “blue collar” (including factory employees, shop assistant, and domestic workers), and farmers.

Statistical analysis

We assessed the extent to which differences in proportions were due to chance alone using the χ2 test, and P values below 0.05 were considered significant. We used two approaches to explore the relative weight of specific covariates on a child’s likelihood of being H pylori positive. Firstly, we used a multivariate logistic model with children as the unit of analysis and their own characteristics (age and sex) as well as those of their families (census, infection of their relatives) as the dependent variables.30 The associations between children’s H pylori test result (positive v negative) and individual covariates were expressed as odds ratios with 95% confidence intervals. However, the weakness of such an approach is that individual children may belong to same family, thus violating the assumption of independence of observations.

Therefore, we also used a model with individual families as the unit of analysis. In this model, the effect of parents’ serological state was assessed within families with the same number of children, comparing the number of children positive according to the presence of one, two, or no parents positive for H pylori. Statistical analyses were performed with the spss/pc statistical package.

Results

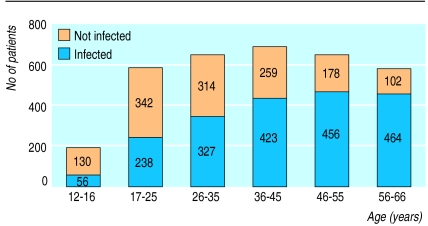

The overall prevalence of H pylori infection in the town of Campogalliano was 59.7%, increasing with age (from 30% in those aged 12-16 to 82% in those aged 56-66) with a typical cohort effect (figure). The prevalence of H pylori infection was similar among families with less than four people (60%, 800/1337) and those with more than four people living in the same household (57%, 55/96). The prevalence of H pylori infection in the 1433 participants belonging to the 416 families analysed, accounting for 186 children, was 51.2% (734), with 41% of families having both parents infected and 44% one parent (table 1). The prevalence of H pylori infection in children increased with increasing numbers of parents infected (table 2).

Table 1.

Distribution of families investigated according to parents’ infection with H pylori

| Parental infection | No (%) of families | No of children |

|---|---|---|

| Group 1 (both parents infected) | 170 (41) | 265 |

| Group 2 (one parent infected) | 185 (44) | 256 |

| Father infected | 94 (23) | 133 |

| Mother infected | 91 (22) | 123 |

| Group 3 (neither parent infected) | 61 (15) | 80 |

| Total | 416 (100) | 601 |

Table 2.

Proportion of children infected with H pylori according to infection of parents

| Parental infection | No (%) of children infected* | 95% CI |

|---|---|---|

| Group 1 (both parents infected) | 116/265 (44) | 37.9 to 50.1 |

| Group 2 (one parent infected) | 75/256 (30) | 24.8 to 36 |

| Father infected | 34/133 (25) | 17.5 to 32.5 |

| Mother infected | 41/123 (33) | 24.5 to 41.5 |

| Group 3 (neither parent infected) | 17/80 (21) | 11.9 to 30.1 |

Significant trend (χ2 test, P<0.001).

Based on fathers’ occupation, 66 families could be defined as white collar (91 children), 237 as blue collar (331 children), and 87 as farmers (128 children). Among parents, H pylori prevalence was related to occupation, the proportion of fathers testing positive being 55% (36) among white collar workers, 60% (142) in blue collar workers, and 74%64in farmers (χ2 for trend 6.44, P=0.01) with no significant difference with sex. The trend with husband’s occupation was not significant for women (prevalences 58%38, 62% (147), and 75%65 respectively; χ2 for trend 3.59, P=0.059). White collar families had a significantly lower (21%) proportion of infected children compared with the other two groups (table 3).

Table 3.

Infection with H pylori among children according to father’s job

| Father’s job | No of families | No (%) of children infected with H pylori | 95% CI |

|---|---|---|---|

| White collar worker | 66 | 19/91 (21)* | 12.5 to 29.5 |

| Blue collar worker | 237 | 124/331 (37) | 31.7 to 42.3 |

| Farmer | 87 | 52/128 (41) | 32.3 to 49.7 |

| Total | 390† | 195/550 (35) | — |

P <0.005 compared with other groups.

Father’s job not available for 26 families.

Table 4 shows the multivariate analysis assessing the relation between infection in parents and that in children (after children’s age, sex, and family social status were corrected for). Children from families in which both parents were H pylori positive had over twice the risk of being H pylori positive (odds ratio 2.48, 95% confidence interval 1.35 to 4.52) compared with those from families in which neither parent was positive. The risk was also higher for children belonging to families with one positive parent, although the difference was not significant (P=0.27). Children with fathers who were blue collar workers or farmers showed a significant increase in the risk of being H pylori positive compared with those from white collar families (P<0.05).

Table 4.

Results of logistic regression analysis assessing relation between infection of parents and likelihood of children being positive for H pylori adjusted for children’s age, sex, and family social environment

| Variable | Odds ratio | 95% CI | P value |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 parent infected v no parent | 1.47 | 0.81 to 2.70 | 0.27 |

| 2 parents infected v no parent | 2.48 | 1.35 to 4.52 | 0.016 |

| Blue collar workers and farmers v white collar workers | 2.02 | 1.16 to 3.50 | 0.02 |

| Age (continuous variable) | 1.06 | 1.02 to 1.09 | 0.001 |

| Sex (male reference category) | 0.76 | 0.53 to 1.09 | 0.18 |

These findings were confirmed when families were used as the unit of analysis (table 5). The number of positive children increased according to the number of positive parents consistently within families with the same number of children. Overall, after number of children was adjusted for, families in which one or both of the parents was positive had a significant increase in the risk of having at least one positive child (2.07, 1.32 to 3.24 for one parent; 2.71, 1.39 to 5.26 for two parents) compared with those with both parents negative.

Table 5.

H pylori infection in children according to parents’ infection and number of children in family

| No of children in family | No (%) of infected children

|

Total | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 1 | 2 | >2 | ||

| 1: | |||||

| Both parents negative | 32 (74) | 11 (26) | 43 | ||

| 1 parent positive | 96 (77) | 29 (23) | 125 | ||

| Both parents positive | 53 (60) | 36 (40) | 89 | ||

| 2: | |||||

| Both parents negative | 12 (71) | 4 (24) | 1 (6) | 17 | |

| 1 parent positive | 26 (51) | 18 (35) | 7 (14) | 51 | |

| Both parents positive | 27 (37) | 28 (38) | 18 (25) | 73 | |

| >2: | |||||

| Both parents negative | 1 (100) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| 1 parent positive | 2 (22) | 3 (33) | 1 (11) | 3 (33) | 9 |

| Both parents positive | 0 | 3 (38) | 2 (25) | 3 (38) | 8 |

| Total | 249 | 132 | 29 | 6 | 416 |

Discussion

Our large epidemiological study of the distribution of H pylori prevalence among families used a different approach from that used in other studies addressing the same topic. It was designed as a population study, and all the consenting residents of a small town were involved, thus avoiding the biases that previous studies on selected series could have had. We studied all the consenting families in one community, representing a valuable sample (66%) of the entire population. Infection of children could be related directly to parents’ positivity and family’s social background.

The overall prevalence of H pylori infection differed according to age, and within children aged 12-16 years the prevalence of infection was similar to that found in a population based study performed in San Marino,31 an area not far from Campogalliano, but different from other reported values. The prevalence of H pylori infection in children was, for example, 40% in Saudi Arabia,32 60% in India,33 and only 10-15% in the United States.34 This is probably related both to the different age groups considered (5-10 years, 3-10 years, and 3-5 years, in the three countries), and to the different conditions that the children live in.

In our study the prevalence of H pylori infection in children was higher if the social conditions were lower. H pylori prevalence was significantly higher (P<0.005) among children of farmers than among children of blue and white collar families. Moreover, children living in white collar families had a lower risk of being positive for H pylori. These findings confirm the results of a study by Malaty and Graham which showed a strong inverse correlation between childhood social class and H pylori infection.35 However, we found no correlation between occupancy rates and H pylori infection, and this is consistent with the fact that the hygiene conditions of families belonging to the same community should be similar.

Finally, we found that children living in families in which both parents were infected had a significantly higher rate of infection than children with only one or no parents infected. These findings suggest close personal contact of family members living in the same households and support an oro-oral or faecal-oral route of transmission for H pylori, as shown by other authors.36,37

Although the prevalence of H pylori infection in children with two positive parents was lower than that reported by Drumm et al (probably because they studied a selected series),9 it was similar to that found in two other studies.24,38 Malaty et al studied family clustering of H pylori infections in families of healthy asymptomatic volunteers and showed that H pylori infection was higher among children with a positive parent (mother or father) than among those whose parents were negative (50% v 5% respectively).24 Offspring of infected index cases were more likely to be infected than those of uninfected index cases, regardless of whether the infected case was the mother or father. The second study evaluated mothers, fathers, and siblings of index children separately and concluded that mothers of H pylori infected children were more likely to be positive.38

The strong association between infection in mothers and their children may be explained by a greater chance of person to person contact between them within a family. We also found that the prevalence of H pylori infection among children was higher when the mother, rather then the father, was infected (33% v 25%).

In conclusion, our findings confirm, in an open population, a relation between H pylori infection in children and parents and that social environment has a role in spreading the infection. Although the association between parental and children’s infection supports the hypothesis of a person to person, probably oro-oral, transmission of infection, the effect of social environment raises the need for further research to assess whether aspects of lifestyle (housing, dietary habits, etc) could have a role.

Figure.

Infection with H pylori according to age

Footnotes

Funding: This study was supported by grants from Fondo per lo Studio delle Malattie del Fegato (no profit foundation) and Bracco spa.

Competing interests: None declared.

References

- 1.Dooley C. Background and historical consideration of Helicobacter pylori. Gastroenterol Clin N Am. 1993;22:1–3. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Dooley CP, Cohen H, Fitzgibbons PL, Bauer M, Appleman MD, Perez-Perez GI, et al. Prevalence of Helicobacter pylori infection and histologic gastritis in asymptomatic persons. N Engl J Med. 1989;321:1526–1536. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198912073212302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Langenberg ML, Tytgat GNJ, Schipper MEI, Rietra PJGM, Zanen HC. Campylobacter-like organism in the stomach of patients and healthy individuals. Lancet. 1984;i:1348. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Carrick J, Lee A, Hazell S, Ralston M, Daskalopoulos G. Campylobacter pylori, duodenal ulcer, and gastric metaplasia: possible role of functional heterotopic tissue in ulcerogenesis. Gut. 1989;30:790–797. doi: 10.1136/gut.30.6.790. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Daskalopoulos G, Carrick J, Borody T, Hazell S, Ralston M. Do Campylobacter pyloridis and gastric metaplasia have a role in duodenal ulceration? Gastroenterology. 1987;92:1363. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Johnston BJ, Reed PI, Ali MH. Campylobacter-like organism in duodenal and antral endoscopic biopsies: relationship to inflammation. Gut. 1986;27:1132–1137. doi: 10.1136/gut.27.10.1132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Whitehead R, Truelove SC, Gear MWR. The histological diagnosis of chronic gastritis in fiberoptic gastroscope biopsy specimen. J Clin Pathol. 1972;25:1–11. doi: 10.1136/jcp.25.1.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fox JG, Correa P, Taylor NS, Zavala D, Fontham E, Janney F, et al. Campylobacter pylori-associated gastritis and immune response in a population at increased risk of gastric carcinoma. Am J Gastroenterol. 1989;84:775–781. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Malaty HM, Evans DG, Evans DJ, Graham DY. Helicobacter pylori in Hispanics: comparison with blacks and whites of similar age and socioeconomic class. Gastroenterology. 1992;103:813–816. doi: 10.1016/0016-5085(92)90011-m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Katelaris PH, Zoli G, Norbu P, Tippett G, Lowe D, Farthing MTG. An evaluation of factors affecting Helicobacter pylori prevalence in a defined population from a developing country. Ital J Gastroenterol. 1991;23(suppl. 2):12–18. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mitchel HM, Li YY, Hu PJ, Liu Q, Chen M, Du GG, et al. Epidemiology of Helicobacter pylori in southern China: identification of early childhood as the critical period for acquisition. J Infect Dis. 1992;166:149–153. doi: 10.1093/infdis/166.1.149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Drumm B, Guillermo I, Perez-Perez GI, Blaser MJ, Sherman PM. Intrafamilial clustering of Helicobacter pylori infection. N Engl J Med. 1990;322:359–363. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199002083220603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mendall M, Goggin PM, Molineaux N, Levy J, Toosy T, Strachan D, et al. Childhood living conditions and Helicobacter pylori seropositivity in adult life. Lancet. 1992;339:896–897. doi: 10.1016/0140-6736(92)90931-r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mitchell JD, Mitchell HM, Tobias V. Acute Helicobacter pylori in an infant, associated with gastric ulceration and serological evidence of intra-familial transmission. Am J Gastroenterol. 1992;87:382–386. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Alfonso V, Gonzales-Granda D, Alonso C, Ponce J, Bixquert M, Oltra C, et al. Los pacientes con ulcera duodenal transmiten el Helicobacter pylori a sus familiares? Rev Esp Enf Dig. 1995;87(2):109–113. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Best LM, Veldhuyzen van Zanten SJ, Sherman PM, Bezanson GS. Serological detection of Helicobacter pylori antibodies in children and their parents. J Clin Microbiol. 1994;2:1193–1196. doi: 10.1128/jcm.32.5.1193-1196.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Conti-Nibali S, Cadranel S, Van Trich L, Verhas M. C14 urea breath test (UBT) in famiglie di bambini con gastrite da Campylobacter pylori. Riv Ital Ped. 1988;14 (suppl 1):87. [Google Scholar]

- 18.De Giacomo C, Lisato L, Negrini R, Licardi G, Maggiore G. Serum immune responseto Helicobacter pylori in children: epidemiologic and clinical application. J Pediatr. 1991;119:205–210. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3476(05)80728-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.De Giacomo C, Pergo M, Bawa P, Perotti P, Daturi R, Giacobone E, et al. Intrafamilial diffusion of Helicobacter pylori infection. Acta Gastroenterol Belgica. 1993;suppl:87. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jones DM, Eldridge J, Whorwell PJ. Antibodies to Campylobacter pyloridis in household contacts of infected patients. BMJ. 1987;249:615. doi: 10.1136/bmj.294.6572.615-a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lin SK, Lambert JR, Hardikar W, Nicholson L, Schembri MA. Helicobacter pylori infection in families: evidence for person-to-person transmission. Ital J Gastroenterol. 1991;23(suppl. 2):10. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mitchell HM, Bohane TD, Berkowicz J, Hazel SL, Lee A. Antibody to Campylobacter pylori in families of index children with gastrointestinal illness due to Campylobacter pylori. Lancet. 1987;ii:681–682. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(87)92459-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Nwokolo CU, Bickley J, Owen RJ, Costas M, Fraser AI. Evidence of clonal variants of Helicobacter pylori in three generations of a duodenal ulcer disease family. Gut. 1992;33:1323–1327. doi: 10.1136/gut.33.10.1323. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Oderda G, Vaira D, Holton J, Ainley C, Altare F, Boero M, et al. Helicobacter pylori in children with peptic ulcer and their families. Dig Dis Sc. 1991;36:572–576. doi: 10.1007/BF01297021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Malaty HM, Graham DY, Klein PD, Evans DG, Adam E, Evans DJ. Transmission of Helicobacter pylori infection. Studies in families of healthy individuals. Scand J Gastroenterol. 1991;26:927–932. doi: 10.3109/00365529108996244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mendall MA. Transmission of Helicobacter pylori. Semin Gastrointest Dis. 1997;8:113–123. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bellentani S, Tiribelli C, Saccoccio G, Sodde M, Fratti N, De Martin C, et al. for the Dionysos Study Group. Prevalence of chronic liver disease in the general population of northern Italy: the Dionysos study Hepatology 19942061442–1449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Talley NJ, Newell DG, Ormand JE, Carpenter HE, Wilson WE, Zinsmeister AR, et al. Serodiagnosis of Helicobacter pylori: comparison of enzyme linked immunosorbent assays. J Clin Microbiol. 1991;29:1635–1639. doi: 10.1128/jcm.29.8.1635-1639.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Palli D, Vaira D, Menegatti M, Saieva C. A serologic survey of Helicobacter pylori infection in 3281 Italian patients endoscoped for upper gastrointestinal symptoms. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 1997;11:719–728. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2036.1997.00215.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hosmer DW, Lemeshow S. Applied logistic regression. New York: John Wiley; 1983. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gasbarrini G, Pretolani S, Bonvicini F, Gatto MRA, Tonelli E, Megraud F, et al. A population based study of Helicobacter pylori infection in a European country: the San Marino study. Relations with gastrointestinal diseases. Gut. 1995;36:838–844. doi: 10.1136/gut.36.6.838. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Al Moagel MA, Evans DG, Abdulghani ME, Adam E, Evans DJ, Jr, Malaty HM, et al. Prevalence of Helicobacter (formerly Campylobacter) pylori infection in Saudi Arabia, and comparison of those with and without upper gastrointestinal symptoms. Am J Gastroenterol. 1990;85:944–948. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Graham DY, Adam E, Reddy GT, Agarwal JP, Agarwal R, Evans DJ, Jr, et al. Seroepidemiology of Helicobacter pylori infection in India. Comparison of developing and developed countries. Dig Dis Sci. 1991;36:1084–1088. doi: 10.1007/BF01297451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Fiedorek SC, Malaty HM, Evans DG, Pumphrey CL, Casteel HB, Evans DJ, Jr, et al. Factors influencing the epidemiology of Helicobacter pylori infection in children. Pediatrics. 1991;88:578–582. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Malaty HM, Graham DY. Importance of childhood socioeconomic status on the current prevalence of Helicobacter pylori infection. Gut. 1994;35:742–745. doi: 10.1136/gut.35.6.742. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Mapstone NP, Lynch DA, Lewis FA, Axon AT, Tompkins DS, Dixon MF, et al. Identification of Helicobacter pylori DNA in the mouths and stomachs of patients with gastritis using PCR. J Clin Pathol. 1993;46:540–543. doi: 10.1136/jcp.46.6.540. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Thomas JE, Gibson GR, Darbee MK, Dale A, Weaver LT. Isolation of Helicobacter pylori from human faeces. Lancet. 1992;340:1194–1195. doi: 10.1016/0140-6736(92)92894-l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Bonamico M, Monti S, Luzzi I, Magliocca FM, Cipolletta E, Calvani L, et al. Helicobacter pylori infection in families of Helicobacter pylori positive children. Ital J Gastroenterol. 1996;28:512–517. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]