Abstract

Heme is an essential molecule in aerobic organisms. Heme consists of protoporphyrin IX and a ferrous (Fe2+) iron atom, which has high affinity for oxygen (O2). Hemoglobin, the major oxygen-carrying protein in blood, is the most abundant heme-protein in animals and humans. Hemoglobin consists of four globin subunits (α2β2), with each subunit carrying a heme group. Ferrous (Fe2+) hemoglobin is easily oxidized in circulation to ferric (Fe3+) hemoglobin, which readily releases free hemin. Hemin is hydrophobic and intercalates into cell membranes. Hydrogen peroxide can split the heme ring and release “free” redox-active iron, which catalytically amplifies the production of reactive oxygen species. These oxidants can oxidize lipids, proteins, and DNA; activate cell-signaling pathways and oxidant-sensitive, proinflammatory transcription factors; alter protein expression; perturb membrane channels; and induce apoptosis and cell death. Heme-derived oxidants induce recruitment of leukocytes, platelets, and red blood cells to the vessel wall; oxidize low-density lipoproteins; and consume nitric oxide. Heme metabolism, extracellular and intracellular defenses against heme, and cellular cytoprotective adaptations are emphasized. Sickle cell disease, an archetypal example of hemolysis, heme-induced oxidative stress, and cytoprotective adaptation, is reviewed. Antioxid. Redox Signal. 12, 233–248.

Introduction

Iron-derived reactive oxygen species (ROS) are involved in the pathogenesis of numerous vascular disorders. The most abundant source of redox-active iron is heme, which is inherently dangerous when it escapes from its physiologic sites (118). Heme-derived iron plays an instrumental role in the pathology of hemolysis, trauma, and reperfusion after ischemia. Erythrocytes package 20 mM hemoglobin in an environment full of antioxidants to prevent excessive oxidation (23). Severe hemolysis can lead to the release of up to 20 μM plasma hemoglobin (79). When erythrocytes are lysed, extracellular hemoglobin is easily oxidized from ferrous (Fe2+) to ferric (Fe3+) hemoglobin (methemoglobin), which, in turn, readily releases heme (65). The extreme hydrophobicity of free heme permits it to intercalate into cell membranes, creating increased cellular susceptibility to oxidant-mediated killing as well as generation of ROS (22). Once heme is in the cell membrane, hydrogen peroxide from sources such as activated leukocytes can split the heme ring and release “free” redox-active iron, which can catalytically amplify the production of ROS inside the cell (54). Amplification of ROS production by redox-active iron can directly lead to additional lipid, protein, and DNA damage and ultimately to cell death (79). Heme-derived redox-active iron also can indirectly cause cell death by promoting the oxidation of low-density lipoproteins (LDLs), leading to foam cell formation and apoptosis in the vessel wall (19, 23, 24, 67, 103).

Intravascular hemolytic diseases include malaria, sickle cell anemia, thalassemia, disseminated intravascular coagulation (DIC), and paroxysmal nocturnal hemoglobinuria (PNH). Heme also is released during blood clotting. Similarly, rhabdomyolysis, caused by the rapid breakdown of skeletal muscle tissue, leads to the release of heme-containing myoglobin into circulation and ultimately to renal injury. All hemolytic diseases share several identifying features, which include escape of hemoglobin/myoglobin from inside the cell, heme-iron–induced oxidative stress (21), vascular inflammation (24), and recruitment of leukocytes to the site of vascular injury (21). Exposure of cells to sublethal oxidative stress results in an adaptive, cytoprotective modulation of various cell-signaling pathways (18, 21, 22). ROS can activate and inactivate transcription factors, membrane channels, and metabolic enzymes, and regulate signaling pathways (49, 62, 86, 97, 107, 141, 156). Oxidation of protein thiols is a major mechanism by which ROS integrate into cellular signal-transduction pathways (108). Oxidative stress triggers vascular inflammation by activating oxidant-sensitive cellular pathways that include transcription factors nuclear factor-kappa B (NF-κB), activator protein-1 (AP-1), and others (62, 86, 97, 107, 141). When activated, these regulatory oxidant-sensitive transcription factors markedly change the pattern of gene expression and orchestrate crucial cytoprotective adaptations. One of these adaptations is the recruitment of leukocytes and platelets and blood cell–endothelial cell interactions in the microcirculation (93). The adhesion of circulating blood cells to vascular endothelium is a key element of the proinflammatory and prothrombogenic phenotype assumed by the vasculature in hemolytic diseases and other disease states associated with oxidative stress (30, 56, 71, 142, 149). It is critical to understand how cells and tissues defend from or adapt to excessive oxidative stress, resulting from hemolysis and the release of hemoglobin, heme, and iron into the vasculature. Understanding these adaptations underpins the basis for potential therapies to prevent or treat vasculopathy and organ injury in hemolytic diseases.

Extracellular Defense Against Hemoglobin

In response to an oxidative and inflammatory onslaught of heme, animals have evolved multiple mechanisms for protection. The first line of defense after the release of hemoglobin into the vasculature is the plasma protein haptoglobin. Haptoglobin is an acute-phase protein that scavenges hemoglobin in the event of intravascular or extravascular hemolysis. The protein exists in humans as three main phenotypes, Hp1-1, Hp2-2, and Hp2-1 (53). Hemoglobin in plasma is instantly bound with high affinity to haptoglobin–an interaction leading to the recognition of the complex by the HbSR/CD163 scavenger receptor and endocytosis in macrophages (78). This specific receptor–ligand interaction removes haptoglobin–hemoglobin complexes from plasma, but not free haptoglobin, which explains the depletion of circulating haptoglobin in individuals with increased intravascular hemolysis (78). The HbSR/CD163 scavenging system for hemoglobin protects against the toxic effects of hemoglobin in circulation. Hemoglobin is a low-affinity ligand for CD163, even in the absence of haptoglobin (36, 122). CD163 is a highly expressed macrophage membrane protein belonging to the scavenger-receptor cysteine-rich domain family (122). CD163 expression is induced by interleukin-6, interleukin-10, and glucocorticoids (121). CD163-mediated endocytosis of the haptoglobin–hemoglobin complex represents a major pathway for uptake of iron into tissue macrophages and the induction of heme oxygenase-1 (HO-1) (35). Hemoglobin induces antioxidant and antiinflammatory genes in macrophages, including HO-1 (120). The hemoglobin–CD163–HO-1 pathway induces ferritin-1 expression, which is linked to heme breakdown by HO-1. Schaer and colleagues (120) reported that this response is not related to hemoglobin-mediated depletion of reduced glutathione, and no protein phosphorylation-dependent CD163 signaling exists in the protective macrophage response to hemoglobin.

Extracellular Defense Against Heme: Hemopexin

Hemopexin is a heme-binding plasma glycoprotein that forms the second line of defense against hemoglobin-mediated oxidative damage during intravascular hemolysis. Hemopexin is synthesized in the liver and serves as an acute-phase reactant with the highest binding affinity to heme among plasma proteins (46, 101, 140). Hemopexin is formed by two four-bladed β-propeller domains at 90-degree angles with the heme bound between the two β-propeller domains near an interdomain linker peptide (114, 140). Heme–hemopexin complexes bind to CD91 receptors [also known as the low-density lipoprotein–related protein-1 (LRP1) and α2-macroglobulin receptor on hepatic parenchymal cells] and are removed by receptor-mediated endocytosis. Once hemopexin releases heme inside the endosome, it is unclear whether unbound hemopexin is recycled back to the circulation or degraded (60, 116, 127). During severe hemolysis, hemopexin is depleted from plasma, which suggests that incomplete recycling of hemopexin may occur (101). Please refer to the review by Tolosano et al., “Heme Scavenging and Other Facets of Hemopexin” in this issue.

Heme transported to the liver by hemopexin is degraded by microsomal HO-1, and the released iron is rapidly bound by ferritin (39). Thus, haptoglobin and hemopexin have significant antioxidant properties by binding plasma hemoglobin and free heme and preventing heme release of redox-active iron. In addition, CD91–heme–hemopexin receptor complexes are able to induce intra- and extracellular antioxidant activities (99). HO-1, transferrin, transferrin receptor, and ferritin are all regulated to some degree by the binding of heme–hemopexin complexes to the CD91 receptor (144). Other genes activated by receptor-bound heme–hemopexin include proteins important for cellular defenses against oxidative stress, such as metallothioneins and redox-sensitive transcription factors, including c-Jun, RelA/NF-κB and metal-regulatory transcription factor 1 (MTF-1) (126).

Other Extracellular Defenses Against Heme

Ferric heme can exchange between hemoglobin and albumin, although the affinity of human albumin for ferric heme is only ∼1/15th that of globin (37). Heme exchange between hemoglobin and albumin is blocked by the binding of hemoglobin to haptoglobin (101). Heme bound to albumin can readily exchange onto hemopexin, suggesting that albumin may serve as a heme reservoir during periods of acute hemolysis and heme overload (37, 45).

Serum high- and low-density lipoproteins (HDLs and LDLs) also can bind plasma heme and participate in its clearance from circulation (19, 45, 52, 66, 67). In the presence of hydrogen peroxide from activated leukocytes, heme iron can oxidize LDL, which can be removed by macrophage scavenger receptors, leading to cholesterol-rich foam cell formation and apoptosis (19, 66). The dissociation rate constants for ferric heme decrease in the following order: LDL>HDL>albumin>hemopexin, suggesting that hemopexin is the chief heme-binding protein in plasma (19, 22, 24, 25).

α1-Microglobulin, a member of the lipocalin family, is a 26-kDa plasma and tissue glycoprotein (2). α1-Microglobulin is an evolutionarily conserved immunomodulatory plasma protein (91). In all species studied, α1-microglobulin is synthesized by hepatocytes and catabolized in the renal proximal tubular cells (91). α1-Microglobulin is found in blood in free form and is tightly bound to IgA via a cystine–cystine bond (31). In addition, α1-microglobulin can bind heme, has catalytic reductase activity, and can reduce methemoglobin (8, 9). α1-Microglobulin, when exposed to the cytosolic side of erythrocyte membranes or to purified oxyhemoglobin, can be truncated at the C-terminus (8). When bound to heme, the truncated protein shows a time-dependent spectral rearrangement, suggestive of degradation of heme concomitant with formation of a heterogeneous yellow–brown chromophore associated with the protein (8). The processed α1-microglobulin is found in normal and pathologic human urine, indicating that the cleavage occurs in vivo (8). The results suggest that truncated α1-microglobulin is involved in extracellular heme catabolism, especially when red blood cells are hemolyzed. The heme-binding and putative heme-cleavage properties of α1-microglobulin likely provide an additional physiologic protection mechanism against extracellular heme.

The kidney is the main site of hemoglobin clearance and degradation in conditions of severe hemolysis. Two epithelial endocytic receptors, megalin and cubilin, located in the brush borders of the renal proximal tubules, mediate hemoglobin uptake in the kidney (48). Studies using knockout mice demonstrated that megalin is responsible for physiologic clearance of hemoglobin under normal conditions, but cubilin may assist during conditions of hemoglobinuria. The clearance of hemoglobin and α1-microglobulin–heme complexes by renal proximal tubular cells probably explains why renal tubuli are dependent on intrinsic HO-1 production for their survival under oxidative stresses and why HO-1 deficiency is characterized by advanced tubulointerstitial injury (154).

Intracellular Defense Against Heme: Heme Oxygenase-1 (HO-1)

Once heme gets into a cell, whether by haptoglobin, hemopexin, albumin, lipoproteins, α1-microglobulin, megalin/cubilin, or hydrophobic intercalation into the cell membrane, the heme and its concomitant oxidative stress induce the cytoprotective and rate-limiting enzyme in the catabolism of heme, HO-1. HO-1 is a microsomal/mitochondrial (128) enzyme that oxidizes protoheme to biliverdin IXα in a three-step process that requires oxygen and reducing equivalents from NADPH (Fig. 1) (57). Electrons used in the HO-1 reaction are provided by NADPH-cytochrome P450 reductase. In the process, HO-1 releases three enzymatic byproducts: carbon monoxide (CO); biliverdin, which is converted by biliverdin reductase to bilirubin; and iron, which stimulates ferritin synthesis. These byproducts of HO-1–mediated heme catabolism have established antioxidant and antiinflammatory properties. Three isoforms (HO-1, HO-2, and HO-3) that catalyze heme catabolism have been identified (95). HO-1 is a 32-kDa protein that is inducible by numerous stimuli, including heme, but also non-heme stimuli, such as UV irradiation, heavy metals, hormones, endotoxin, cytokines, oxidants, and heat shock (95). In most tissues, HO-1 is either expressed at low levels or is not expressed at all, whereas HO-2 is constitutively expressed. Although the expression of HO-1 can be induced in response to a range of stimuli, HO-2 responds to few regulatory factors (95). HO-1 is present in a variety of tissues, with the highest basal levels in tissues responsible for the degradation of senescent RBCs and heme, including the spleen, reticulo-endothelial cells of the liver, vascular endothelial cells, and bone marrow (117).

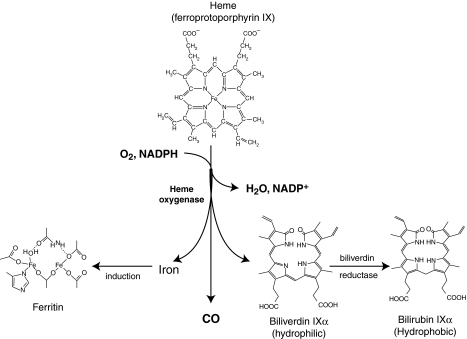

FIG. 1.

Heme degradation by heme oxygenase. The catabolism of heme (ferroprotoporphyrin IX) via heme oxygenase requires the participation of NADPH and O2. Heme is broken and oxidized at the α-methene bridge, producing equimolar amounts of CO, ferrous iron, and biliverdin. From Wu and Wang ref. 150.

Not surprisingly, human patients and mouse models have elevated HO-1 in response to prolonged hemolysis (27, 104, 145). Of all sites in the body, the endothelium may be at greatest risk of exposure to heme. Exposure of endothelial cells to hemoglobin increases the expression of HO-1. In cell culture, heme greatly potentiates endothelial cell killing mediated by leukocytes and other sources of ROS (20). As a defense against heme, endothelial cells upregulate HO-1 and ferritin. If cultured endothelial cells are briefly pulsed with heme and are then allowed to incubate for a prolonged period (16 h), the cells become highly resistant to oxidant-mediated injury and to the accumulation of endothelial lipid-peroxidation products. This protection is associated with the induction within 4 h of mRNA for HO-1 (18). After 16 h, HO-1 and ferritin protein have increased ∼50- and 10-fold, respectively. In animal models, increased expression of HO-1 has been shown to protect tissues and cells against ischemia/reperfusion injury, oxidative stress, inflammation, transplant rejection, apoptosis, and cell proliferation (110, 147). Conversely, HO-1–null mice (hmox-1−/−) and human patients deficient in HO-1 are especially prone to oxidative stress and inflammation (72, 146, 151). The central importance of this protective system was recently highlighted in a child diagnosed with HO-1 deficiency, who exhibited extensive endothelial damage (151).

Regulation of HO-1 Expression

The HO-1 gene (hmox-1)-promoter region contains two inducible enhancer regions, E1 and E2, which contain multiple Maf recognition elements (MARE) (74, 112). Hmox-1 transcription is initiated when the basic leucine zipper (bZIP) transcription factor NF-E2–related factor 2 (Nrf2) binds to the MARE regions to form heterodimers with Maf proteins (74). Bach1 is another member of the bZIP transcription factor family, which serves as a potent repressor of hmox-1 transcription through its ability to bind MARE regions, preventing Nrf2-Maf heterodimers from forming (111). Bach1 has a higher binding affinity for the MARE regions than has Nrf2, making it a key regulator of hmox-1 (107, 129, 132, 153).

Bach1 has multiple cysteine-proline (CP) motifs that serve as heme-binding regions (107). The DNA-binding action of Bach1 is inhibited when heme, or another heavy metal such as cadmium, is bound to these CP motifs. Release of Bach1 from the DNA leads to its exportation out of the nucleus (129, 130). It is suggested that exportation of Bach1 allows Maf/Nrf2 heterodimer formation on the MARE sites, leading to transcriptional upregulation of hmox-1 (107, 112, 129). Studies with Bach1−/−-knockout mice support this hypothesis by demonstrating a reduction of reperfusion injuries and decreased apoptosis in cardiomyocytes (153). This cytoprotective effect was abolished by pretreating the mice with a potent HO-1 inhibitor, zinc protoporphyrin, indicating that the observed cytoprotection is in part mediated through an increase in HO-1 protein expression and activity in the Bach1−/− mice (153).

Moreover, Bach1 small interfering RNA (siRNA) significantly increased HO-1 mRNA levels in Huh-7 hepatocytes in a dose- and time-dependent fashion (125). The upregulation of HO-1 in both of these studies could not be attributed to Bach1 alone, leaving room for the alternative hypothesis of heme-mediated Nrf2 stabilization, which was proposed by Alam and associates (6, 125). They suggest that hmox-1 is activated when heme increases the stability of the Nrf2 protein, leading to accumulation of Nrf2/Maf heterodimers at the enhancer region.

The Bach1/Maf/Nrf2 system is a potential therapeutic target for ameliorating heme-induced inflammation. Complex overlapping intracellular signaling cascades of kinases and redox-sensitive transcription factors further regulate the expression of HO-1 in response to external stimuli. These additional transcription factors include AP-1 (81, 92, 124), AP-2 (84), hypoxia-inducible factor-1-α (HIF-1α) (55, 85, 131, 152), and NF-κB (82, 86). These transcription factors are in part regulated by multiple overlapping protein kinases, including mitogen-activated protein kinases (MAPKs), extracellular-regulated kinase (ERK) and p38, phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase (PI3K), cAMP-dependent protein kinase or protein kinase A (PKA)(61), and protein kinase C (PKC) (126, 136), but not c-jun N-terminal kinase (JNK) (7, 40).

The expression of HO-1 is triggered by its substrate heme and diverse stress stimuli, including ultraviolet radiation (143), hypoxia (43, 85, 102), inflammation (1, 64, 148), heavy metals (3, 90, 105, 134, 135), hydrogen peroxide (73, 106), and nitric oxide (NO) (47, 133, 101). According to a study by Alam and Den (5), the phorbol ester 12-O-tetradecanoylphorbol-13-acetate–mediated HO-1 induction in mice required AP-1 binding to the 5′-flanking region of the target gene. Other studies have demonstrated the induction of HO-1 by other oxidative stimuli [such as heme (124), sodium arsenite, cobalt chloride (92), bacterial lipopolysaccharide (82) and cobalt protoporphyrin (124)] is mediated by AP-1 activation. Because AP-1–mediated HO-1 induction can be attenuated by the antioxidant N-acetylcysteine (4, 47), it is likely that oxidant-sensitive thiols play a critical role in the initiation of the signal-transduction pathways leading to HO-1 gene transcription.

Intracellular Defense Against Heme Iron: Ferritin

Redox-active iron can be effectively controlled by ferritin through iron sequestration and ferroxidase activity, which oxidizes iron from Fe2+ to Fe3+ for safe storage inside of ferritin. Within most cells, the major depot of nonmetabolic iron is ferritin, a high-molecular-mass (450 kDa), multimeric (24-subunit) protein (heavy or H chain Mr, 21,000 kDa, light- or L-chain Mr, 20,700 kDa) with a very high capacity for storing iron (4,500 mol of iron/mol of ferritin) (137). The H chain is involved in ferroxidase activity necessary for iron uptake and oxidation of ferrous iron, whereas the L chain is involved in nucleation of the iron core. Hydrogen peroxide is a byproduct of the ferroxidase reaction (155). Ferritin appears to have an antioxidant role inside the cell; it inhibits cell proliferation and confers resistance to oxidative damage and apoptosis (18, 89). The expression of ferritin is regulated at both the transcriptional and posttranscriptional levels by iron, cytokines, and ROS (11). In the ferritin shell, the proportion of H and L subunits depends on the iron status of the cell or tissue and varies between organs and species (137). Under certain chemical circumstances, ferritin can release catalytically active iron (138), which can actually foster peroxidation of lipids (139). However, such release is slight under more physiologic circumstances, with fewer than two of 4,500 potential iron atoms released per ferritin molecule (33). Alternatively, ferritin can beneficially sequester intracellular iron, limiting the prooxidant hazard posed by this reactive metal; moreover, the fact that the H chain of ferritin manifests ferroxidase activity (17, 88) implies that ferritin-stored iron might resist cyclical reduction/oxidation reactions, which tend to propagate and amplify oxidative damage.

Ferritin is found primarily in the cytosol; however, a novel ferritin type, specifically targeted to mitochondria, has been found in humans, rats, and mice (87). It is structurally and functionally similar to cytosolic ferritin. Mitochondrial ferritin has properties similar to those of heavy-chain ferritin, but its expression is limited to the testis, neuronal cells, and islets of Langerhans. However, it also is found in iron-rich mitochondria of erythroblasts from patients with sideroblastic anemia. Recombinant mitochondrial ferritin can protect mitochondria from redox-active iron.

Sickle Cell Disease: An Archetypal Example of Hemolysis, Heme-Induced Oxidative Stress, and Cytoprotective Adaptation

Sickle cell disease is a devastating hemolytic disease caused by a single base pair mutation in the β-globin chain of hemoglobin. It is characterized by recurring episodes of painful vasoocclusion, leading to ischemia/reperfusion injury and organ damage. Recently, the critical roles of oxidative stress, nitric oxide (NO) consumption, endothelial cell activation, and inflammation in vasoocclusion have been recognized, in part because of the development of transgenic murine models of sickle cell disease. Two mouse models of human sickle cell disease, S + S-Antilles and BERK sickle mice, have intravascular hemolysis, as demonstrated by increased plasma hemoglobin, decreased plasma haptoglobin, and increased plasma bilirubin (Table 1). The BERK sickle mice have more-severe organ pathology and a shorter lifespan than do the S + S-Antilles sickle mice. This is likely related to the increased rate of hemolysis in the BERK model. S + S-Antilles sickle mice are minimally anemic, and BERK sickle mice are severely anemic compared with normal control mice (Table 1). The S + S-Antilles mice express small amounts of mouse hemoglobin that can inhibit sickling, resulting in less hemolysis and a less-severe phenotype than BERK mice. Low plasma haptoglobin and high plasma hemoglobin indicate that the extracellular plasma defenses against plasma hemoglobin are overwhelmed in both models (Table 1). Reticulocyte counts, expressed as a percentage of red blood cells, are elevated in S + S-Antilles and BERK sickle mice compared with normal controls (Table 1).

Table 1.

Sickle Mice Have Intravascular Hemolysis

| Mouse model | Hematocrit (%) | Reticulocytes (% of RBC) | Plasma hemoglobin (mg/dL) | Plasma methemoglobin (mg/dL) | Plasma haptoglobin (% of Normal) | Plasma bilirubin (mg/dL) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Normal | 42.9 ± 1.5 | 3.1 ± 0.9 | 0.59 ± 0.04 | <0.1 | 100.0 ± 46.1 | 0.92 ± 0.13 |

| S + S-Antilles | 40.1 ± 3.0* | 11.2 ± 2.4* | 2.36 ± 0.92* | 1.0 ± 0.2 | 39.6 ± 13.1* | 1.71 ± 0.53* |

| BERK | 21.6 ± 3.3* | 31.6 ± 2.9* | 5.5 ± 2.0* | 2.3 ± 0.8 | 42.9 ± 6.1* | 5.95 ± 1.78* |

Heparinized whole blood was collected in capillary tubes for manual measurement of hematocrits (Hct) by packed red blood cell (RBC) volume and for reticulocyte staining and counting in methylene blue. Reticulocytes, identified by their DNA staining, were expressed as a percentage of RBC. Plasma hemoglobin was measured by Drabkins reagent. Plasma haptoglobin was measured by Western blotting and is expressed as a percent of normal C57BL/6 plasma haptoglobin, and total plasma bilirubin was measured colorimetrically by the diazo bilirubin method (96).

n = 4–10 mice/group except metHb (n = 2); *p < 0.05 normal vs. sickle.

Table modified from ref. 27.

S + S-Antilles and BERK mice also have elevated levels of methemoglobin in their blood compared with normal mice (Table 1). Ferric (Fe3+) heme (hemin) can rapidly dissociate from methemoglobin (65, 66) and potentially provide a ready source of heme to the vasculature. One way in which methemoglobin can form in plasma is by reaction of ferrous (Fe2+) hemoglobin with NO, resulting in a decrease in NO and heme bioavailability (59, 98). NO is produced from the substrate l-arginine by endothelial nitric oxide synthase (eNOS) and mediates vasorelaxation as well as having antioxidant, antiadhesive, and antithrombotic properties. In sickle cell disease, the increase in plasma hemoglobin contributes to the increased ability of both deoxy- and oxyhemoglobin-S to participate in scavenging reactions with NO, which reduce NO bioavailability. NO binds very rapidly with deoxygenated hemoglobin to form stable ferrous (Fe2+) hemoglobin–NO complexes. Oxygenated hemoglobin reacts with NO to produce methemoglobin and nitrate (14). Cell-free plasma hemoglobin in the ferrous (Fe2+) valence state, is readily available to participate in Fenton-based redox reactions. In addition, hemolysis further impairs NO bioavailability through the release of arginase from the erythrocyte, which competes with NO synthase (NOS) for the substrate arginine (75). Combined, these factors contribute to the overall reduced bioavailability of NO in hemolytic diseases such as sickle cell disease, which contributes to pulmonary hypertension and other comorbidities (69).

Model Linking Hemolysis, Oxidative Stress, Inflammation and Vaso-occlusion in Sickle Cell Disease

Sickle cell patients, even during steady state, have markers of inflammation, including leukocytosis, elevated C-reactive protein, and other acute-phase reactants. They often have elevated levels of endothelial perturbants (e.g., thrombin), proximate inflammatory mediators (e.g., IL-6), cell activators (e.g., platelet-activating factor), powerful effector molecules (e.g., CD40 ligand), and markers of endothelial activation (e.g., soluble VCAM-1) (4–9). The etiology of this proinflammatory state in sickle cell disease could be the result of vascular injury and response of the immune system to organ infarctions. However, studies in murine models of sickle cell disease have demonstrated that, rather than just being a response to vasoocclusion, inflammation actively participates in vasoocclusion. The pathophysiology of sickle cell disease can be modeled as a vicious cycle propelled by hemolysis, oxidative stress, vascular inflammation, blood cell adhesion to the endothelium, and vasoocclusion (Fig. 2A). Because of hemolysis, the vessel wall is exposed to higher levels of ROS catalyzed by redox-active iron (24). Activated leukocytes are another source of ROS in sickle cell disease (30, 44, 58, 83). Brief incubation of human neutrophils with micromolar concentrations of hemin (1–20 μM) trigger the oxidative burst, and the production of ROS is directly proportional to the concentration of hemin added to the cells (50). Moreover, circulating neutrophils are significantly elevated in sickle cell disease, making them a rich source of oxidants (10, 12, 38). Finally, antioxidants are depleted in the tissues of sickle patients and mice, enhancing sensitivity to oxidative stress in sickle cell disease (16, 29). Excessive ROS production activates redox-sensitive transcription factors such as NF-κB and AP-1 (Fig. 2B) (84). These transcription factors promote increased expression of adhesion molecules on the vascular endothelium (Fig. 2C–E) (28, 42, 70, 71, 94, 123, 142). Adhesion of sickle red blood cells and leukocytes to the endothelium and to each other (41, 71, 123, 142, 145, 149) can then lead to vasoocclusion in smaller venules (Fig. 2F) (68) and tissue ischemia in downstream areas deprived of oxygen. These venules can subsequently reestablish flow in a matter of hours, leading to reperfusion of ischemic tissues (109). Reperfusion-injury physiology promotes elevated xanthine oxidase levels, as seen in the plasma of sickle cell disease patients and sickle mice (13, 15). Oxidants produced by xanthine oxidase at the vessel wall continue to fuel the vicious cycle (Fig. 2A), which ultimately leads to tissue injury.

FIG. 2.

Hemolysis, oxidative stress, inflammation, and adhesion lead to vasoocclusion and ischemia/reperfusion injury in sickle cell disease. (A) The vicious cycle of oxidative stress, inflammation, and vasoocclusion in sickle cell disease is initiated and perpetuated through many mechanisms. Sickle red blood cells (RBCs) themselves can generate ROS, and through hemolysis, release hemoglobin and heme into plasma, which can provide iron that catalyzes further ROS production. In turn, activated leukocytes, when exposed to heme, can produce ROS and proinflammatory cytokines and promote endothelium-derived oxidants. These ROS activate NF-κB in the endothelium, which in turn promotes endothelial cell adhesion molecule (ECAM) expression on the microvasculature. Adhesion molecules such as vascular cell adhesion molecule-1 (VCAM-1), intracellular cell adhesion molecule-1 (ICAM-1), P-selectin, and others promote sickle RBCs and leukocyte adhesion, which alters vascular tone and promotes vasoocclusion and subsequent tissue ischemia. These vessels can subsequently reopen, and reperfusion leads to the conversion of xanthine dehydrogenase to xanthine oxidase, promoting more ROS production. Image from ref. 94. (B) Electrophoretic mobility shift assay (EMSA) demonstrates that NF-κB is upregulated in the lungs of transgenic New York sickle mice (NY-S) mice and LPS-treated normal mice [18 h after lipopolysaccharide (LPS) injection] compared with normal lung controls. The summary bar graph plots the mean ± SD lung NF-κB expression for each mouse group as a percentage of normal control mice (n = 3 for NY-S and normal control, n = 2 for LPS-treated control). *p < 0.05; **p < 0.01. (C–E) Western blots confirm upregulated adhesion molecule expression in the lungs of transgenic sickle mice and LPS-treated normal mice (18 h after LPS injection) compared with normal lung controls. Lung homogenates were prepared from three mice in each group. Homogenate proteins, representing 1 μg lung DNA per lane, were separated with SDS-PAGE, transferred electrophoretically to PVDF membranes, and immunoblotted with anti-VCAM, anti-ICAM, or anti-PECAM IgG. Sites of primary antibody binding were visualized with alkaline phosphatase–conjugated donkey anti-goat IgG. The final detection of immunoreactive bands was performed by using a chemifluorescent detection substrate. Protein bands corresponding to each adhesion molecule were quantified with fluorescence densitometry. The figure shows the adhesion-molecule bands from one representative lung from each model and a summary bar graph. The bar graph plots the mean ± SD adhesion-molecule expression for each mouse model as a percentage of normal control mice (n = 3). *p < 0.05; **p < 0.01; and ***p < 0.001. (B–E) were originally published in ref. 26. (F) Histology of venule in the dorsal skin of transgenic sickle mice after 1 h of hypoxia and 1 h of reoxygenation. Dorsal skin samples were taken for histologic analysis after the sickle mice were exposed to 1 h of hypoxia and 1 h of reoxygenation when ∼12% of the venules were static. Skin samples were fixed overnight in formalin, cut into 5-mm sections, embedded in paraffin, mounted on slides, and stained with hematoxylin and eosin before microscopic examination. The figure shows a venule with a suspected vascular obstruction. White arrowheads, leukocytes that appear to be adherent to the vascular endothelium; white arrows, misshapen RBCs inside the venule. Figure is adapted from ref. 68.

Intravital microscopy studies in murine models of sickle cell disease have demonstrated the critical role of adhesion molecules for the interaction of sickle red blood cells and leukocytes with the vessel wall of venules (28, 42, 70, 71, 94, 123). P-selectin, vascular cell-adhesion molecule-1 (VCAM-1), and intracellular adhesion molecule-1 (ICAM-1) on the endothelium are required; blockade or knockout of any one of these adhesion molecules prevents either cytokine- or hypoxia-induced stasis (28, 42, 71, 142).

Antiinflammatory agents such as glucocorticosteroids and antioxidants ameliorate hypoxia/reoxygenation-induced abnormalities in venular blood flow (28, 71, 94). High doses of glucocorticosteroids reduced the duration of hospitalization in children with painful crises and modulated severe acute chest syndrome (32, 51). Because of side effects, immunosuppressive impact, and rebound attacks, glucocorticosteroids have not been widely used in patients with sickle cell disease. The oxidative nature of sickle cell disease can be illustrated by the inhibitory effects of antioxidants on inflammation, adhesion, and vasoocclusion. Antioxidant therapy (allopurinol, superoxide dismutase, and catalase) can ameliorate leukocyte adhesion and microvascular flow abnormalities in transgenic sickle mice in response to hypoxia/reoxygenation (71). N-Acetylcysteine, a sulfhydryl-containing antioxidant, caused a fivefold decrease in vasoocclusive episodes in sickle patients in a phase II clinical trial (113). Polynitroxyl albumin (PNA), an injectable vascular nitroxide free-radical therapeutic, is being developed as an early treatment for painful vasoocclusive crisis in sickle cell disease. PNA acts as a mimic of SOD (76, 115, 119) and can facilitate heme-mediated catalase-like activity (77). PNA can interrupt the cycle of oxidative stress, inflammation, and vasoocclusion by catalytically removing ROS from the vasculature, thereby inhibiting NF-κB activation, adhesion molecule expression, and hypoxia-induced stasis in a dorsal skin-fold chamber model of vasoocclusion (94).

Cytoprotective Adaptation in Sickle Cell Disease: Heme Oxygenase-1 (HO-1)

The sickle patient and sickle mouse defend or adapt to excessive oxidative stress resulting from red blood cell hemolysis and the release of hemoglobin, heme, and iron into the vasculature, in part, by increasing the physiologic defenses against heme. Sickle cell disease is a prime example of an adaptive upregulation of HO-1 in response to hemolysis. HO-1 expression is significantly increased in the lungs, livers, and spleens of S + S-Antilles and BERK sickle mice compared with normal control mice (Fig. 3). Treatment of sickle mice with hemin (40 μmoles/kg IP/d × 3 d) further increases HO-1 expression and activity (Fig. 4A and B) and inhibits NF-κB, VCAM-1, and ICAM-1 expression (Fig. 5A and B), leukocyte–endothelium interactions (Fig. 6), and hypoxia/reoxygenation-induced stasis (Fig. 7A and B). Heme oxygenase inhibition by tin protoporphyrin exacerbates stasis in sickle mice (Fig. 8A). Furthermore, treatment of sickle mice with the HO-1 enzymatic products, CO (250 parts per million in air for 1 h × 3 d) or biliverdin (50 μmol/kg IP × 2 at 16 and 2 h) inhibits NF-κB (Fig. 8B), VCAM-1 and ICAM-1 expression, and stasis (Fig. 9). Local administration of HO-1-adenovirus to subcutaneous skin increases HO-1 (Fig. 10A) and inhibits hypoxia/reoxygenation-induced stasis in the skin of sickle mice (Fig. 10B).

FIG. 3.

HO-1 expression is increased in the organs of sickle mice. Western blots for HO-1 were performed on organ homogenates (1 μg of organ DNA per lane) from lungs, livers, and spleens of untreated normal, S + S-Antilles, and BERK mice. (A) The 32-kDa HO-1 bands are shown for each organ and each mouse. (B) The mean HO-1 band intensities (n = 4) ± SD are expressed as a percentage of those in normal control mice. *p < 0.05, normal versus sickle. Figure is taken from ref. 27.

FIG. 4.

Hemin injections further increase HO-1 expression in sickle mice. (A) HO-1 expression can be further upregulated in the organs of sickle mice with hemin treatment. S + S-Antilles mice were either untreated or injected with hemin (40 μmol/kg/d, IP) for 3 days. Twenty-four hours after the third injection, the organs were harvested, and Western blots for HO-1 were performed on lung, liver, and spleen homogenates (1 μg of organ homogenate DNA per lane). The mean HO-1 band intensities (n = 3) ± SD are expressed as a percentage of those in untreated S + S-Antilles mice (100%). Below each bar is a representative HO-1 band from the Western blot. *p < 0.05, untreated versus hemin. (B) HO-1 activity in normal and S + S-Antilles livers. HO-1 activity was measured in microsomes isolated from another group of normal and S + S-Antilles sickle mice. Mice were untreated, injected with hemin (40 μmol/kg/d, IP) for 3 days, or injected with hemin plus SnPP (40 μmol/kg/d of each porphyrin, IP) for 3 days. The results in triplicate are expressed as mean ± SEM picomoles of bilirubin generated per milligram microsomal protein per hour. *p < 0.05, normal versus sickle. (A, B) are taken from ref. 27.

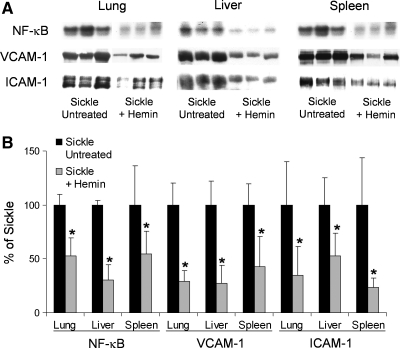

FIG. 5.

Further upregulation of HO-1 by hemin inhibits NF-κB activation and VCAM-1 and ICAM-1 overexpression in the organs of sickle mice. S + S-Antilles mice were either untreated or injected with hemin (40 μmol/kg/d, IP) for 3 days. Twenty-four hours after the third injection, the organs were harvested from mice in ambient air. NF-κB activation was measured with EMSA, and VCAM-1 and ICAM-1 expression was measured with Western blotting in organ homogenates of the lungs, liver, and spleen of sickle mice. (A) The NF-κB, VCAM-1, and ICAM-1 bands are shown for each organ and each sickle mouse. (B) The bar graph shows the mean band intensity (n = 3 mice per group) ± SD for each organ treatment group. *p < 0.05, untreated versus hemin. Figure is taken from ref. 27.

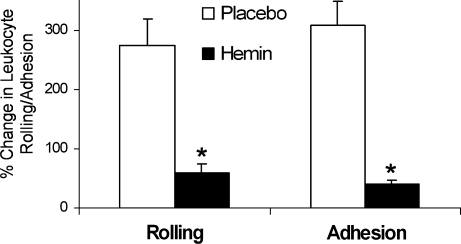

FIG. 6.

Further upregulation of HO-1 by hemin inhibits hypoxia/reoxygenation–induced increases in leukocyte–endothelium interactions. S + S-Antilles mice with an implanted dorsal skin-fold chamber (DSFC) were treated with either placebo (saline) or hemin injections (40 μmol/kg/d, IP) for 3 days. Twenty-four hours after the third injection, leukocyte rolling and adhesion were measured in the subcutaneous venules at baseline in ambient air and again in the same venules after exposure of the mice to 1 h of hypoxia (7% O2/93% N2) and 1 h of reoxygenation in room air. Results are expressed as mean ± SEM percentage change in leukocyte rolling and adhesion after hypoxia/reoxygenation; n = 2 mice and a minimum of 20 venules per group. *p < 0.05, placebo versus hemin. Figure is taken from ref. 27.

FIG. 7.

Further upregulation of HO-1 by hemin inhibits stasis, and HO-1 inhibition by tin protoporphyrin IX (SnPP) exacerbates stasis in sickle mice. S + S-Antilles (A) and BERK (B) mice with an implanted DSFC were untreated, injected with hemin (40 μmol/kg/d, IP) for 3 days, or injected with SnPP (40 μmol/kg/d, IP) for 3 days. Twenty-four hours after the third injection, stasis was measured after 1 h of hypoxia (7% O2/93% N2) and 1 and 4 h of reoxygenation in room air; n = 3–10 mice and a minimum of 20 venules per mouse. *p < 0.05, untreated versus hemin or SnPP. The proportions of venules exhibiting stasis at each time point were compared by using a z test. Figure is taken from ref. 27.

FIG. 8.

Biliverdin or CO treatment inhibits NF-κB activation in the lungs of sickle mice. S + S-Antilles mice were untreated, treated with biliverdin injections (50 μmol/kg, IP, twice, at 16 and 2 h), or treated with inhaled CO (250 ppm in air for 1 h per day for 3 days). Two hours after the second biliverdin injection or 24 h after the third CO treatment, mice were exposed to 3 h of hypoxia (7% O2/93% N2) and 2 h of reoxygenation in room air. After 2 h of reoxygenation, the lungs were harvested, and NF-κB activation was measured in organ homogenates with EMSA; n = 3 mice per group. Below each bar is a representative NF-κB band from the EMSA. *p < 0.05, untreated versus biliverdin or CO. Figure is taken from ref. 27.

FIG. 9.

CO and biliverdin inhibit stasis in sickle mice. S + S-Antilles mice with an implanted DSFC were either untreated or treated with inhaled CO (250 ppm CO in air) for 1 h per day for 3 days or biliverdin injections (50 μmol/kg, IP, twice), at 16 and 2 h, before hypoxia. Twenty-four hours after the third CO treatment or 2 h after the second biliverdin injection, stasis was measured after 1 h of hypoxia (7% O2/93% N2) and 1 h of reoxygenation in room air; n = 3–10 mice and a minimum of 20 venules per mouse. *p < 0.05, untreated versus CO or biliverdin. The proportions of venules exhibiting stasis at each time point were compared by using a z test. Figure is taken from ref. 27.

FIG. 10.

HO-1-ADV increases HO-1 expression and inhibits stasis. Local administration of HO-1-ADV increases HO-1 expression (A) and inhibits hypoxia/reoxygenation–induced stasis (B) in the skin. S + S-Antilles sickle mice with an implanted DSFC were treated with either a rat HO-1-ADV construct (n = 3 mice and 84 venules) or an empty Control-ADV construct (n = 4 mice and 64 venules). The adenovirus constructs (2 × 107 MOI) in sterile saline were dripped onto the subcutaneous skin inside the DSFC. Forty-eight hours after adenovirus treatment, hypoxia/reoxygenation–induced stasis was measured (B). After measurement of stasis, the skin inside the DSFC window was harvested, and HO-1 expression was measured in the skin homogenates with Western blotting (A). Below each bar is a representative HO-1 band from the Western blot. *p < 0.05, Control-ADV versus HO-1-ADV. Figure is taken from ref. 27.

HO-1 plays an essential role in the inhibition and resolution of vasoocclusion in sickle cell disease. HO-1 and its products, carbon monoxide, biliverdin/bilirubin, and its linkage to the iron chelator ferritin, modulate vasoocclusion through multiple mechanisms, including reducing oxidative stress, inhibiting NF-κB, downregulating endothelial cell-adhesion molecules, decreasing red blood cell hemolysis, and altering vascular tone. However, sickle cell patients often have adaptive increases in HO-1 activity insufficient to handle completely the excessive heme burden, particularly during acute bouts of hemolysis. Increases in HO-1 activity or its downstream products or both, in excess of the adaptive upregulation seen in tissues of sickle cell mice and patients, may be important strategies for innovative new therapies to prevent and treat hemolysis, oxidative stress, inflammation, vasoocclusion, and the accompanying pathologies found in sickle cell disease. HO-1 gene therapy, by using Sleeping Beauty–mediated transposition of an HO-1 transgene, is a promising nonviral approach to enhance HO-1 expression significantly in sickle cell disease (34). To transfer the rat HO-1 gene into sickle mice, our laboratory has cloned the rat hmox-1 gene into a Sleeping Beauty transposase (SB-Tn) system. The SB-Tn system was developed by resurrecting nonfunctional remnants of an ancient vertebrate transposable element from salmonid fish (63). SB-Tn has features that make it particularly attractive as a vector for gene therapy. It can accommodate a much larger transgene than can viral vectors; it is nonviral; it does not induce an immune inflammatory response in rodent models; and it mediates efficient stable transgene integration that exhibits persistent expression. SB-Tn-mediated HO-1 gene delivery to S + S-Antilles sickle mice leads to long-term (+8 weeks) HO-1 transgene expression in liver, a decrease in markers of vascular inflammation and inhibition of vasoocclusion (unpublished data). The cytoprotective effects of the HO-1 transgene are not recapitulated in transgenic sickle mice expressing a truncated HO-1 transgene with limited or no enzymatic activity. Thus, HO-1 is a critical enzyme in the ameliorating the pathophysiology of sickle cell disease.

Conclusions

Despite the importance of heme for aerobic life, the body does all that it can to defend itself against heme that has escaped its normal cellular compartments. Multiple extracellular and intracellular defenses have evolved to protect the body from heme, including haptoglobin, hemopexin, albumin, α1-microglobulin, HO-1, and ferritin. Sickle cell disease is an archetypal example of a cytoprotective adaptation to heme-induced oxidative stress. The sickle patient and sickle mouse defend or adapt to excessive oxidative stress resulting from red blood cell hemolysis and the release of hemoglobin, heme, and iron into the vasculature by increasing the expression of HO-1. HO-1 activity is pivotal in orchestrating the body's cytoprotective responses to heme-induced oxidative stress. The cells' adaptation to excess heme activates a cascade of signal-transduction pathways and oxidant-sensitive transcription factors that turn on multiple cytoprotective genes. Induction of HO-1 and release of heme degradation products (CO, biliverdin/bilirubin, and iron with its linkage to the iron chelator ferritin) modulate vasoocclusion through multiple mechanisms, including reducing oxidative stress, inhibiting NF-κB, downregulating endothelial cell adhesion molecules, decreasing red blood cell hemolysis, and altering vascular tone. Pharmacologic and genetic regulation of HO-1 gene expression is a promising avenue of therapeutic research for all diseases of oxidative stress and inflammation.

Abbreviations Used

- ADV

adenovirus

- AP-1

activator protein-1

- bZIP

basic leucine zipper

- CO

carbon monoxide

- CP

cysteine-proline

- DIC

disseminated intravascular coagulation

- DSFC

dorsal skin-fold chamber

- EMSA

electrophoretic mobility-shift assay

- ERK

extracellular-regulated kinase

- Fe2+

ferrous iron

- Fe3+

ferric iron

- H

heavy chain

- HDL

high-density lipoprotein

- HIF-1α

hypoxia-inducible factor-1-alpha

- hmox-1

heme-oxygenase-1 gene

- HO

heme oxygenase

- ICAM-1

intracellular adhesion molecule-1

- JNK

c-jun N-terminal kinase

- L

light chain

- LDL

low-density lipoprotein

- LRP-1

low-density lipoprotein–related protein-1

- MAPKs

mitogen-activated protein kinases

- MARE

Maf recognition elements

- MTF-1

metal regulatory transcription factor 1

- NF-κB

nuclear factor-kappa B

- NO

nitric oxide

- NOS

nitric oxide synthase

- Nrf2

NF-E2–related factor 2

- O2

oxygen

- PI3K

phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase

- PKA

cAMP-dependent protein kinase or protein kinase A

- PKC

protein kinase C

- PNA

polynitroxyl albumin

- PNH

paroxysmal nocturnal hemoglobinuria

- ROS

reactive oxygen species

- SnPP

tin protoporphyrin IX

- VCAM-1

vascular cell adhesion molecule-1

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge former members of the laboratory group, Hemchandra Mahaseth and Thomas E. Welch, and current collaborator Robert P. Hebbel for their help with prior publications by our group. The authors received funding for this research from the National Heart Lung and Blood Institute: NHLBI R01 HL67367 and P01HL055552.

Author Disclosure Statement

Drs. Belcher and Vercellotti received research funding from Lundbeck Research USA, Inc. (Paramus, NJ), formerly Ovation Pharmaceuticals, Inc., for the study of panhematin toxicity in sickle mice. The other authors have no disclosures.

References

- 1.Agarwal A. Kim Y. Matas A. Alam J. Nath K. Gas-generation systems in acute renal allograft rejection in the rat: co-Induction of heme oxygenase and nitric oxide synthase. Transplantation. 1996;61:93–98. doi: 10.1097/00007890-199601150-00019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Akerström B. Tissue distribution of guinea pig alpha 1-microglobulin. Cell Mol Biol. 1983;29:489–495. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Alam J. Multiple elements within the 5′ distal enhancer of the mouse heme oxygenase-1 gene mediate induction by heavy metals. J Biol Chem. 1994;269:25049–25056. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Alam J. Camhi S. Choi AMK. Identification of a second region upstream of the mouse heme oxygenase-1 gene that functions as a basal level and inducer-dependent transcription enhancer. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:11977–11984. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.20.11977. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Alam J. Den Z. Distal AP-1 binding sites mediate basal level enhancement and TPA induction of the mouse heme oxygenase-1 gene. J Biol Chem. 1992;267:21894–21900. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Alam J. Killeen E. Gong P. Naquin R. Hu B. Stewart D. Ingelfinger JR. Nath KA. Heme activates the heme oxygenase-1 gene in renal epithelial cells by stabilizing Nrf2. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2003;284:F743–F752. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00376.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Alam J. Wicks C. Stewart D. Gong P. Touchard C. Otterbein S. Choi AMK. Burow ME. Tou J-S. Mechanism of heme oxygenase-1 gene activation by cadmium in MCF-7 mammary epithelial cells: role of p38 kinase and Nrf2 transcription factor. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:27694–27702. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M004729200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Allhorn M. Berggard T. Nordberg J. Olsson ML. Akerstrom B. Processing of the lipocalin alpha 1-microglobulin by hemoglobin induces heme-binding and heme-degradation properties. Blood. 2002;99:1894–1901. doi: 10.1182/blood.v99.6.1894. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Allhorn M. Klapyta A. Åkerström B. Redox properties of the lipocalin [alpha]1-microglobulin: reduction of cytochrome c, hemoglobin, and free iron. Free Radic Biol Med. 2005;38:557–567. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2004.12.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Amer J. Ghoti H. Rachmilewitz E. Koren A. Levin C. Fibach E. Red blood cells, platelets and polymorphonuclear neutrophils of patients with sickle cell disease exhibit oxidative stress that can be ameliorated by antioxidants. Br J Haematol. 2006;132:108–113. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2141.2005.05834.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Arosio P. Levi S. Ferritin, iron homeostasis, and oxidative damage. Free Radic Biol Med. 2002;33:457–463. doi: 10.1016/s0891-5849(02)00842-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Aslan M. Canatan D. Modulation of redox pathways in neutrophils from sickle cell disease patients. Exp Hematol. 2008;36:1535–1544. doi: 10.1016/j.exphem.2008.07.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Aslan M. Freeman BA. Oxidant-mediated impairment of nitric oxide signaling in sickle cell disease: mechanisms and consequences. Cell Mol Biol (Noisy-le-Grand) 2004;50:95–105. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Aslan M. Freeman BA. Redox-dependent impairment of vascular function in sickle cell disease. Free Radic Biol Med. 2007;43:1469–1483. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2007.08.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Aslan M. Ryan TM. Adler B. Townes TM. Parks DA. Thompson JA. Tousson A. Gladwin MT. Patel RP. Tarpey MM. Batinic-Haberle I. White CR. Freeman BA. Oxygen radical inhibition of nitric oxide-dependent vascular function in sickle cell disease. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2001;98:15215–15220. doi: 10.1073/pnas.221292098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Aslan M. Thornley-Brown D. Freeman BA. Reactive species in sickle cell disease. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2000;899:375–391. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2000.tb06201.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bakker GR. Boyer RF. Iron incorporation into apoferritin: the role of apoferritin as a ferroxidase. J Biol Chem. 1986;261:13182–13185. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Balla G. Jacob HS. Balla J. Rosenberg M. Nath K. Apple F. Eaton JW. Vercellotti GM. Ferritin: a cytoprotective antioxidant strategem of endothelium. J Biol Chem. 1992;267:18148–18153. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Balla G. Jacob HS. Eaton JW. Belcher JD. Vercellotti GM. Hemin: a possible physiological mediator of low density lipoprotein oxidation and endothelial injury. Arterioscler Thromb. 1991;11:1700–1711. doi: 10.1161/01.atv.11.6.1700. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Balla G. Vercellotti G. Muller-Eberhard U. Eaton JW. Jacob HS. Exposure of endothelial cells to free heme potentiates damage mediated by granulocytes and toxic oxygen species. Lab Invest. 1991;64:648–655. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Balla G. Vercellotti GM. Eaton JW. Jacob HS. Iron loading of endothelial cells augments oxidant damage. J Lab Clin Med. 1990;116:546–554. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Balla J. Jacob HS. Balla G. Nath K. Eaton JW. Vercellotti GM. Endothelial-cell heme uptake from heme proteins: induction of sensitization and desensitization to oxidant damage. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1993;90:9285–9289. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.20.9285. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Balla J. Vercellotti GM. Jeney V. Yachie A. Varga Z. Jacob HS. Eaton JW. Balla G. Heme, heme oxygenase, and ferritin: how the vascular endothelium survives (and dies) in an iron-rich environment. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2007;9:1–19. doi: 10.1089/ars.2007.1787. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Balla J. Vercellotti GM. Nath K. Yachie A. Nagy E. Eaton JW. Balla G. Haem, haem oxygenase and ferritin in vascular endothelial cell injury. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2003;18:v8–v12. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfg1034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bamm VV. Tsemakhovich VA. Shaklai M. Shaklai N. Haptoglobin phenotypes differ in their ability to inhibit heme transfer from hemoglobin to LDL. Biochemistry. 2004;43:3899–3906. doi: 10.1021/bi0362626. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Belcher JD. Bryant CJ. Nguyen J. Bowlin PR. Kielbik MC. Bischof JC. Hebbel RP. Vercellotti GM. Transgenic sickle mice have vascular inflammation. Blood. 2003;101:3953–3959. doi: 10.1182/blood-2002-10-3313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Belcher JD. Mahaseth H. Welch TE. Otterbein LE. Hebbel RP. Vercellotti GM. Heme oxygenase-1 is a modulator of inflammation and vaso-occlusion in transgenic sickle mice. J Clin Invest. 2006;116:808–816. doi: 10.1172/JCI26857. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Belcher JD. Mahaseth H. Welch TE. Vilback AE. Sonbol KM. Kalambur VS. Bowlin PR. Bischof JC. Hebbel RP. Vercellotti GM. Critical role of endothelial cell activation in hypoxia-induced vasoocclusion in transgenic sickle mice. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2005;288:H2715–H2725. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00986.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Belcher JD. Marker PH. Geiger P. Girotti AW. Steinberg MH. Hebbel RP. Vercellotti GM. Low-density lipoprotein susceptibility to oxidation and cytotoxicity to endothelium in sickle cell anemia. J Lab Clin Med. 1999;133:605–612. doi: 10.1016/s0022-2143(99)90191-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Belcher JD. Marker PH. Weber JP. Hebbel RP. Vercellotti GM. Activated monocytes in sickle cell disease: potential role in the activation of vascular endothelium and vaso-occlusion. Blood. 2000;96:2451–2459. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Berggard T. Thelin N. Falkenberg C. Enghild JJ. Akerstrom B. Prothrombin, albumin and immunoglobulin A form covalent complexes with α1-microglobulin in human plasma. Eur J Biochem. 1997;245:676–683. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1997.00676.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bernini JC. Rogers ZR. Sandler ES. Reisch JS. Quinn CT. Buchanan GR. Beneficial effect of intravenous dexamethasone in children with mild to moderately severe acute chest syndrome complicating sickle cell disease. Blood. 1998;92:3082–3089. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bolann B. Ulvik R. On the limited ability of superoxide to release iron from ferritin. Eur J Biochem. 1990;193:899–904. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1990.tb19415.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bruzzone CM. Belcher JD. Schuld NJ. Newman KA. Vineyard J. Nguyen J. Chen C. Beckman JD. Steer CJ. Vercellotti GM. Quantitative real-time polymerase chain reaction (qRT-PCR) restriction fragment length polymorphism (RFLP) method for monitoring highly conserved transgene expression during gene therapy. Translat Res. 2008;152:290–297. doi: 10.1016/j.trsl.2008.10.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Buehler PW. Abraham B. Vallelian F. Linnemayr C. Pereira CP. Cipollo JF. Jia Y. Mikolajczyk M. Boretti FS. Schoedon G. Alayash AI. Schaer DJ. Haptoglobin preserves the CD163 hemoglobin scavenger pathway by shielding hemoglobin from peroxidative modification. Blood. 2009;113:2578–2586. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-08-174466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Buehler PW. Vallelian F. Mikolajczyk MG. Schoedon G. Schweizer T. Alayash AI. Schaer DJ. Structural stabilization in tetrameric or polymeric hemoglobin determines its interaction with endogenous antioxidant scavenger pathways. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2008;10:1449–1462. doi: 10.1089/ars.2008.2028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Bunn HF. Jandl JH. Exchange of heme among hemoglobins and between hemoglobin and albumin. J Biol Chem. 1968;243:465–475. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Conran N. Saad S. Costa F. Ikuta T. Leukocyte numbers correlate with plasma levels of granulocyte–macrophage colony-stimulating factor in sickle cell disease. Ann Hematol. 2007;86:255–261. doi: 10.1007/s00277-006-0246-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Davies DM. Smith A. Muller-Eberhard U. Morgan WT. Hepatic subcellular metabolism of heme from heme-hemopexin: incorporation of iron into ferritin. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1979;91:1504–1511. doi: 10.1016/0006-291x(79)91235-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Elbirt KK. Whitmarsh AJ. Davis RJ. Bonkovsky HL. Mechanism of sodium arsenite-mediated induction of heme oxygenase-1 in hepatoma cells: role of mitogen-activated protein N kinases. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:8922–8931. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.15.8922. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Elion JE. Brun M. Odie'vre M-H. Lapoume' roulie CL. Krishnamoorthy R. Vaso-occlusion in sickle cell anemia: role of interactions between blood cells and endothelium. Hematol J. 2004;5:S195–S198. doi: 10.1038/sj.thj.6200452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Embury SH. Matsui NM. Ramanujam S. Mayadas TN. Noguchi CT. Diwan BA. Mohandas N. Cheung AT. The contribution of endothelial cell P-selectin to the microvascular flow of mouse sickle erythrocytes in vivo. Blood. 2004;104:3378–3385. doi: 10.1182/blood-2004-02-0713. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Eyssen-Hernandez R. Ladoux A. Frelin C. Differential regulation of cardiac heme oxygenase-1 and vascular endothelial growth factor mRNA expressions by hemin, heavy metals, heat shock and anoxia. FEBS Lett. 1996;382:229–233. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(96)00127-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Fadlon E. Vordermeier S. Pearson TC. Mire-Sluis AR. Dumonde DC. Phillips J. Fishlock K. Brown KA. Blood polymorphonuclear leukocytes from the majority of sickle cell patients in the crisis phase of the disease show enhanced adhesion to vascular endothelium and increased expression of CD64. Blood. 1998;91:266–274. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Fasano M. Mattu M. Coletta M. Ascenzi P. The heme-iron geometry of ferrous nitrosylated heme-serum lipoproteins, hemopexin, and albumin: a comparative EPR study. J Inorgan Biochem. 2002;91:487–490. doi: 10.1016/s0162-0134(02)00473-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Foidart M. Liem HH. Adornato BT. Engel WK. Muller-Eberhard U. Hemopexin metabolism in patients with altered serum levels. J Lab Clin Med. 1983;102:838–846. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Foresti R. Clark JE. Green CJ. Motterlini R. Thiol compounds interact with nitric oxide in regulating heme oxygenase-1 induction in endothelial cells. involvement of superoxide and peroxynitrite anions. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:18411–18417. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.29.18411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Gburek J. Verroust PJ. Willnow TE. Fyfe JC. Nowacki W. Jacobsen C. Moestrup SK. Christensen EI. Megalin and cubilin are endocytic receptors involved in renal clearance of hemoglobin. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2002;13:423–430. doi: 10.1681/ASN.V132423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Genestra M. Oxyl radicals, redox-sensitive signalling cascades and antioxidants. Cell Signal. 2007;19:1807–1819. doi: 10.1016/j.cellsig.2007.04.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Graca-Souza AV. Arruda MAB. de Freitas MS. Barja-Fidalgo C. Oliveira PL. Neutrophil activation by heme: implications for inflammatory processes. Blood. 2002;99:4160–4165. doi: 10.1182/blood.v99.11.4160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Griffin TC. McIntire D. Buchanan GR. High-dose intravenous methylprednisolone therapy for pain in children and adolescents with sickle cell disease. N Engl J Med. 1994;330:733–737. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199403173301101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Grinshtein N. Bamm VV. Tsemakhovich VA. Shaklai N. Mechanism of low-density lipoprotein oxidation by hemoglobin-derived iron. Biochemistry. 2003;42:6977–6985. doi: 10.1021/bi020647r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Guaeye PM. Glasser N. Faerard G. Lessinger J-M. Influence of human haptoglobin polymorphism on oxidative stress induced by free hemoglobin on red blood cells. Clin Chem Lab Med. 2006;44:542–547. doi: 10.1515/CCLM.2006.095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Halliwell B. Gutteridge JM. Oxygen toxicity, oxygen radicals, transition metals and disease. Biochem J. 1984;219:1–14. doi: 10.1042/bj2190001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Hartsfield CL. Alam J. Choi AMK. Differential signaling pathways of HO-1 gene expression in pulmonary and systemic vascular cells. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 1999;277:L1133–L1141. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.1999.277.6.L1133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Hebbel RP. Vercellotti GM. The endothelial biology of sickle cell disease. J Lab Clin Med. 1997;129:288–293. doi: 10.1016/s0022-2143(97)90176-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Higashimoto Y. Sato H. Sakamoto H. Takahashi K. Palmer G. Noguchi M. The reactions of heme- and verdoheme-heme oxygenase-1 complexes with FMN-depleted NADPH-cytochrome P450 reductase: electrons required for verdoheme oxidation can be transferred through a pathway not involving FMN. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:31659–31667. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M606163200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Hofstra TC. Kalra VK. Meiselman HJ. Coates TD. Sickle erythrocytes adhere to polymorphonuclear neutrophils and activate the neutrophil respiratory burst. Blood. 1996;87:4440–4447. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Huang K-T. Han TH. Hyduke DR. Vaughn MW. Van Herle H. Hein TW. Zhang C. Kuo L. Liao JC. Modulation of nitric oxide bioavailability by erythrocytes. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2001;98:11771–11776. doi: 10.1073/pnas.201276698. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Hvidberg V. Maniecki MB. Jacobsen C. Hojrup P. Moller HJ. Moestrup SK. Identification of the receptor scavenging hemopexin-heme complexes. Blood. 2005;106:2572–2579. doi: 10.1182/blood-2005-03-1185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Immenschuh S. Kietzmann T. Hinke V. Wiederhold M. Katz N. Muller-Eberhard U. The rat heme oxygenase-1 gene is transcriptionally induced via the protein kinase a signaling pathway in rat hepatocyte cultures. Mol Pharmacol. 1998;53:483–491. doi: 10.1124/mol.53.3.483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Ishikawa M. Numazawa S. Yoshida T. Redox regulation of the transcriptional repressor Bach1. Free Radic Biol Med. 2005;38:1344–1352. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2005.01.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Ivics Z. Hackett PB. Plasterk RH. Izsvak Z. Molecular reconstruction of Sleeping Beauty, a Tc1-like transposon from fish, and its transposition in human cells. Cell. 1997;91:501–510. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80436-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Janssen Y. Van Houten B. Borm P. Mossman B. Cell and tissue responses to oxidative damage. Lab Invest. 1993;69:261–274. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Jay U. Methemoglobin: it's not just blue: a concise review. Am J Hematol. 2007;82:134–144. doi: 10.1002/ajh.20738. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Jeney V. Balla J. Yachie A. Varga Z. Vercellotti GM. Eaton JW. Balla G. Pro-oxidant and cytotoxic effects of circulating heme. Blood. 2002;100:879–887. doi: 10.1182/blood.v100.3.879. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Juckett MB. Balla J. Balla G. Jessurun J. Jacob HS. Vercellotti GM. Ferritin protects endothelial cells from oxidized low density lipoprotein in vitro. Am J Pathol. 1995;147:782–789. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Kalambur VS. Mahaseth H. Bischof JC. Kielbik MC. Welch TE. Vilback A. Swanlund DJ. Hebbel RP. Belcher JD. Vercellotti GM. Microvascular blood flow and stasis in transgenic sickle mice: utility of a dorsal skin fold chamber for intravital microscopy. Am J Hematol. 2004;77:117–125. doi: 10.1002/ajh.20143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Kato GJ. Gladwin MT. Evolution of novel small-molecule therapeutics targeting sickle cell vasculopathy. JAMA. 2008;300:2638–2646. doi: 10.1001/jama.2008.598. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Kaul DK. Hebbel RP. Hypoxia/reoxygenation causes inflammatory response in transgenic sickle mice but not in normal mice. J Clin Invest. 2000;106:411–420. doi: 10.1172/JCI9225. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Kaul DK. Liu XD. Choong S. Belcher JD. Vercellotti GM. Hebbel RP. Anti-inflammatory therapy ameliorates leukocyte adhesion and microvascular flow abnormalities in transgenic sickle mice. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2004;287:H293–H301. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.01150.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Kawashima A. Oda Y. Yachie A. Koizumi S. Nakanishi I. Heme oxygenase-1 deficiency: the first autopsy case. Hum Pathol. 2002;33:125–130. doi: 10.1053/hupa.2002.30217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Keyse SM. Tyrrell RM. Heme oxygenase is the major 32-kDa stress protein induced in human skin fibroblasts by UVA radiation, hydrogen peroxide, and sodium arsenite. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1989;86:99–103. doi: 10.1073/pnas.86.1.99. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Kitamuro T. Takahashi K. Ogawa K. Udono-Fujimori R. Takeda K. Furuyama K. Nakayama M. Sun J. Fujita H. Hida W. Hattori T. Shirato K. Igarashi K. Shibahara S. Bach1 functions as a hypoxia-inducible repressor for the heme oxygenase-1 gene in human cells. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:9125–9133. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M209939200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Krajewski ML. Hsu LL. Gladwin MT. The proverbial chicken or the egg? dissection of the role of cell-free hemoglobin versus reactive oxygen species in sickle cell pathophysiology. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2008;295:H4–H7. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00499.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Krishna MC. Grahame DA. Samuni A. Mitchell JB. Russo A. Oxoammonium cation intermediate in the nitroxide-catalyzed dismutation of superoxide. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1992;89:5537–5541. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.12.5537. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Krishna MC. Samuni A. Taira J. Goldstein S. Mitchell JB. Russo A. Stimulation by nitroxides of catalase-like activity of hemeproteins: kinetics and mechanism. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:26018–26025. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.42.26018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Kristiansen M. Graversen JH. Jacobsen C. Sonne O. Hoffman H-J. Law SKA. Moestrup SK. Identification of the haemoglobin scavenger receptor. Nature. 2001;409:198. doi: 10.1038/35051594. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Kumar S. Bandyopadhyay U. Free heme toxicity and its detoxification systems in human. Toxicol Lett. 2005;157:175–188. doi: 10.1016/j.toxlet.2005.03.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Kurata S. Matsumoto M. Nakajima H. Transcriptional control of the heme oxygenase gene in mouse M1 cells during their TPA-induced differentiation into macrophages. J Cell Biochem. 1996;62:314–324. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-4644(199609)62:3%3C314::AID-JCB2%3E3.0.CO;2-U. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Kurata S-C. Matsumoto M. Hoshi M. Nakajima H. Transcriptional control of the heme oxygenase gene during mouse spermatogenesis. Eur J Biochem. 1993;217:633–638. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1993.tb18286.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Kurata S-I. Matsumoto M. Tsuji Y. Nakajima H. Lipopolysaccharide activates transcription of the heme oxygenase gene in mouse M1 cells through oxidative activation of nuclear factor κB. Eur J Biochem. 1996;239:566–571. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1996.0566u.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Lard LR. Mul FP. de Haas M. Roos D. Duits AJ. Neutrophil activation in sickle cell disease. J Leukoc Biol. 1999;66:411–415. doi: 10.1002/jlb.66.3.411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Lavrovsky Y. Schwartzman ML. Levere RD. Kappas A. Abraham NG. Identification of binding sites for transcription factors NF-{kappa}B and AP-2 in the promoter region of the human heme oxygenase 1 gene. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1994;91:5987–5991. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.13.5987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Lee PJ. Jiang B-H. Chin BY. Iyer NV. Alam J. Semenza GL. Choi AMK. Hypoxia-inducible factor-1 mediates transcriptional activation of the heme oxygenase-1 gene in response to hypoxia. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:5375–5381. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Leonard SS. Harris GK. Shi X. Metal-induced oxidative stress and signal transduction. Free Radic Biol Med. 2004;37:1921–1942. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2004.09.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Levi S. Arosio P. Mitochondrial ferritin. Int J Biochem Cell Biol. 2004;36:1887–1889. doi: 10.1016/j.biocel.2003.10.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Levi S. Luzzago A. Cesareni G. Cozzi A. Franceschinelli F. Albertini A. Arosio P. Mechanism of ferritin iron uptake: activity of the H-chain and deletion mapping of the ferro-oxidase site: a study of iron uptake and ferro-oxidase activity of human liver, recombinant H-chain ferritins, and of two H-chain deletion mutants. J Biol Chem. 1988;263:18086–18092. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Lin F. Girotti AW. Elevated ferritin production, iron containment, and oxidant resistance in hemin-treated leukemia cells. Arch Biochem Biophys. 1997;346:131–141. doi: 10.1006/abbi.1997.0300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Lin JHC. Villalon P. Martasek P. Abraham NG. Regulation of heme oxygenase gene expression by cobalt in rat liver and kidney. Eur J Biochem. 1990;192:577–582. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1990.tb19263.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Logdberg LE. Akerstrom B. Badve S. Tissue distribution of the lipocalin alpha-1 microglobulin in the developing human fetus. J Histochem Cytochem. 2000;48:1545–1552. doi: 10.1177/002215540004801111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Lu TH. Shan Y. Pepe J. Lambrecht RW. Bonkovsky HL. Upstream regulatory elements in chick heme oxygenase-1 promoter: a study in primary cultures of chick embryo liver cells. Mol Cell Biochem. 2000;209:17–27. doi: 10.1023/a:1007025505842. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Lum H. Roebuck KA. Oxidant stress and endothelial cell dysfunction. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2001;280:C719–C741. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.2001.280.4.C719. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Mahaseth H. Vercellotti GM. Welch TE. Bowlin PR. Sonbol KM. Hsia CJ. Li M. Bischof JC. Hebbel RP. Belcher JD. Polynitroxyl albumin inhibits inflammation and vasoocclusion in transgenic sickle mice. J Lab Clin Med. 2005;145:204–211. doi: 10.1016/j.lab.2005.02.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Maines MD. The heme oxygenase system: a regulator of second messenger gases. Annu Rev Pharmacol Toxicol. 1997;37:517–554. doi: 10.1146/annurev.pharmtox.37.1.517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Martinek RG. Improved micro-method for determination of serum bilirubin. Clin Chim Acta. 1966;13:161–170. doi: 10.1016/0009-8981(66)90290-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Mense SM. Zhang L. Heme: a versatile signaling molecule controlling the activities of diverse regulators ranging from transcription factors to MAP kinases. Cell Res. 2006;16:681–692. doi: 10.1038/sj.cr.7310086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Minneci PC. Deans KJ. Zhi H. Yuen PS. Star RA. Banks SM. Schechter AN. Natanson C. Gladwin MT. Solomon SB. Hemolysis-associated endothelial dysfunction mediated by accelerated NO inactivation by decompartmentalized oxyhemoglobin. J Clin Invest. 2005;115:3409–3417. doi: 10.1172/JCI25040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Misra UK. Sharma T. Pizzo SV. Ligation of cell surface-associated glucose-regulated protein 78 by receptor-recognized forms of {alpha}2-macroglobulin: activation of p21-activated protein kinase-2-dependent signaling in murine peritoneal macrophages. J Immunol. 2005;175:2525–2533. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.175.4.2525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Motterlini R. Foresti R. Intaglietta M. Winslow RM. NO-mediated activation of heme oxygenase: endogenous cytoprotection against oxidative stress to endothelium. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 1996;270:H107–H114. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1996.270.1.H107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Muller-Eberhard U. Javid J. Liem HH. Hanstein A. Hanna M. Brief report: plasma concentrations of hemopexin, haptoglobin and heme in patients with various hemolytic diseases. Blood. 1968;32:811–815. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Murphy B. Laderoute K. Short S. Sutherland R. The identification of heme oxygenase as a major hypoxic stress protein in Chinese hamster ovary cells. Br J Cancer. 1991;64:69–73. doi: 10.1038/bjc.1991.241. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Nagy E. Jeney V. Yachie A. Szabo RP. Wagner O. Vercellotti GM. Eaton JW. Balla G. Balla J. Oxidation of hemoglobin by lipid hydroperoxide associated with LDL and increased cytotoxic effect by LDL oxidation in heme oxygenase-1 deficiency. Cell Mol Bio (Noisy-le-grand) 2005;51:377–385. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Nath KA. Grande JP. Haggard JJ. Croatt AJ. Katusic ZS. Solovey A. Hebbel RP. Oxidative stress and induction of heme oxygenase-1 in the kidney in sickle cell disease. Am J Pathol. 2001;158:893–903. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)64037-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Neil T. Abraham N. Levere R. Kappas A. Differential heme oxygenase induction by stannous and stannic ions in the heart. J Cell Biochem. 1995;57:409–414. doi: 10.1002/jcb.240570306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Nose K. Shibanuma M. Kikuchi K. Kageyama H. Sakiyama S. Kuroki T. Transcriptional activation of early-response genes by hydrogen peroxide in a mouse osteoblastic cell line. Eur J Biochem. 1991;201:99–106. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1991.tb16261.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Ogawa K. Sun J. Taketani S. Nakajima O. Nishitani C. Sassa S. Hayashi N. Yamamoto M. Shibahara S. Fujita H. Igarashi K. Heme mediates derepression of Maf recognition element through direct binding to transcription repressor Bach1. EMBO J. 2001;20:2835–2843. doi: 10.1093/emboj/20.11.2835. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Omura T. Heme-thiolate proteins. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2005;338:404–409. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2005.08.267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Osarogiagbon UR. Choong S. Belcher JD. Vercellotti GM. Paller MS. Hebbel RP. Reperfusion injury pathophysiology in sickle transgenic mice. Blood. 2000;96:314–320. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Otterbein LE. Soares MP. Yamashita K. Bach FH. Heme oxygenase-1: unleashing the protective properties of heme. Trends Immunol. 2003;24:449–455. doi: 10.1016/s1471-4906(03)00181-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Oyake T. Itoh K. Motohashi H. Hayashi N. Hoshino H. Nishizawa M. Yamamoto M. Igarashi K. Bach proteins belong to a novel family of BTB-basic leucine zipper transcription factors that interact with MafK and regulate transcription through the NF-E2 site. Mol Cell Biol. 1996;16:6083–6095. doi: 10.1128/mcb.16.11.6083. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Ozono R. New biotechnological methods to reduce oxidative stress in the cardiovascular system: focusing on the bach1/heme oxygenase-1 pathway. Curr Pharm Biotechnol. 2006;7:87–93. doi: 10.2174/138920106776597630. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Pace B. Shartava A. Pack-Mabien A. Mulekar M. Ardia A. Goodman S. Effects of N-acetylcysteine on dense cell formation in sickle cell disease. Am J Hematol. 2003;73:26–32. doi: 10.1002/ajh.10321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Paoli M. Anderson BF. Baker HM. Morgan WT. Smith A. Baker EN. Crystal structure of hemopexin reveals a novel high-affinity heme site formed between two [beta]-propeller domains. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 1999;6:926–931. doi: 10.1038/13294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Park JH. Ma L. Oshima T. Carter P. Coe L. Ma JW. Specian R. Grisham MB. Trimble CE. Hsia CJC. Liu JE. Alexander JS. Polynitroxylated starch/TPL attenuates cachexia and increased epithelial permeability associated with TNBS colitis. Inflammation. 2002;26:1–11. doi: 10.1023/a:1014420327417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Potter D. Chroneos ZC. Baynes JW. Sinclair PR. Gorman N. Liem HH. Muller-Eberhard U. Thorpe SR. In vivo fate of hemopexin and heme-hemopexin complexes in the rat. Arch Biochem Biophys. 1993;300:98–104. doi: 10.1006/abbi.1993.1014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Ryter SW. Alam J. Choi AMK. Heme oxygenase-1/carbon monoxide: from basic science to therapeutic applications. Physiol Rev. 2006;86:583–650. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00011.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]