Abstract

Objectives

To evaluate two different methods of improving adherence to antidepressant drugs.

Design

Factorial randomised controlled single blind trial of treatment leaflet, drug counselling, both, or treatment as usual.

Setting

Primary care in Wessex

Participants

250 patients starting treatment with tricyclic antidepressants.

Main outcome measures

Adherence to drug treatment (by confidential self report and electronic monitor); depressive symptoms and health status.

Results

66 (63%) patients continued with drugs to 12 weeks in the counselled group compared with 42 (39%) of those who did not receiving counselling (odds ratio 2.7, 95% confidence interval 1.6 to 4.8; number needed to treat=4). Treatment leaflets had no significant effect on adherence. No differences in depressive symptoms were found between treatment groups overall, although a significant improvement was found in patients with major depressive disorder receiving drug doses of at least 75 mg (depression score 4 (SD 3.7) counselling v 5.9 (SD 5.0) no counselling, P=0.038).

Conclusions

Counselling about drug treatment significantly improved adherence, but clinical benefit was seen only in patients with major depressive disorder receiving doses ⩾75 mg. Further research is required to evaluate the effect of this approach in combination with appropriate targeting of treatment and advice about dosage.

Key messages

Non-adherence is a serious problem in the treatment of depression by general practitioners

In this study a brief psychosocial intervention delivered by a nurse greatly improved adherence

Clinical benefit was apparent only in patients with major depressive episodes on higher doses of drugs

Counselling should be targeted at patients with symptoms of at least moderate severity and combined with therapeutic drug doses

Introduction

Depressive illness is an important public health problem.1–2 In Britain most patients are managed in primary care, with depression accounting for about 10% of consultations for new illness episodes.3 Antidepressants account for 7% of primary care pharmaceutical expenditure (N Hardy, personal communication). Although antidepressants are effective in patients with “major depression,”4 effectiveness is reduced by non-adherence. Estimates of discontinuation at one month range from 30% to 68%.5–9 Non-adherence is difficult to measure10: methods such as self reporting or counting pills have serious limitations. The development of electromechanical medication monitors represents an important advance.

A systematic review of interventions to improve adherence called for further research in clinical populations with appropriate designs, incorporating assessment of both adherence and outcomes.11 “Compliance therapy” is effective in improving adherence and outcome for patients with schizophrenia.12 The feasibility of using practice nurses to improve care of depressed patients has also been shown.13 We therefore developed a brief intervention for patients receiving antidepressants (antidepressant drug counselling) for administration by practice nurses. We conducted a randomised trial in primary care to compare the counselling programme with a prescription information leaflet14 and treatment as usual.

Participants and methods

Study group

General practitioners in Wessex were asked to notify the research team of patients aged 18 or over who were starting new courses of treatment with dothiepin or amitriptyline. Forty three practices agreed; 28 entered patients. Inclusion was based on clinical diagnosis of depressive illness; research diagnostic criteria for major depressive disorder were applied only to permit subgroup analysis. Patients were excluded if they had received either drug within 3 months, had a contraindication (allergy, heart disease, glaucoma, or pregnancy), or were receiving other incompatible drugs. The research interviewer assessed suicide risk, and any patient at high risk was excluded.

We sent general practitioners a questionnaire after the end of recruitment to assess referral bias. Two steps were taken to minimise bias. Firstly, the study was explained as an evaluation of treatment satisfaction: the principal purpose of assessing adherence was concealed. Secondly, we recruited an “attention control” group, which received only a 12 week interview, to assess the effect of closer monitoring by the research team on adherence.

Assignment and blinding

Immediately after referral, patients were individually randomised in blocks of eight to one of four treatment groups (treatment as usual, leaflet, drug counselling, or both interventions) by prearranged random number sequence, stratified by drug type, in a factorial design. To maintain blinding the randomisation key was concealed from interviewers. Leaflets were included in an opaque sealed envelope with study information. Patients were unaware of their allocation at first interview and asked not to reveal drug counselling sessions to the interviewer subsequently. A formal test of blindness was not conducted. All local research ethics committees granted ethical approval.

Interventions

The information leaflet was developed according to published principles and European Union directives.15,16 It contained information about the drug, unwanted effects, and what to do in the event of missing a dose. Patients were given drug counselling by a nurse at weeks 2 and 8, according to a written protocol. Four nurses acted as therapists: all had general nursing qualifications, had worked for at least 10 years since qualification, and had primary care experience; none had specialist mental health experience or training. Training for antidepressant drug counselling (conducted by RP) took 4 hours. Sessions included assessment of daily routine and lifestyle, attitudes to treatment, and understanding of the reasons for treatment. Education was given about depressive illness and related problems, self help, and local resources. The importance of drug treatment was emphasised, and side effects and their management discussed. Advice was given about the use of reminders and cues, the need to continue treatment for up to 6 months, and what to do in the event of forgetting a dose. The feasibility of involving family or friends with medicine taking was explored.

Outcome measures

At entry we obtained demographic information and medical and psychiatric history from patients and applied diagnostic criteria for major depressive disorder (DSM-IIIR).17 Depressive symptoms were measured by the hospital anxiety and depression scale,18 and functional status was measured by the SF-36 health survey.19 Interviews were conducted at baseline, 6 weeks, and when drugs were discontinued or at 12 weeks, whichever was sooner. A postal questionnaire was sent at 12 weeks to all those who discontinued. At 6 weeks, self reported adherence, depressive symptoms, and unwanted effects of treatment were assessed. At the final visit, reported adherence, satisfaction with treatment, and unwanted effects were reassessed and the depression scale and SF-36 repeated.

To check reliability of self reported adherence we monitored adherence in a subgroup using an electromechanical monitor (MEMS, Ardex). Patients were seen at 3 weeks to resupply drugs and pills were surreptitiously counted. At 6 weeks, the container was collected and the cap data downloaded.

Statistical analysis

The principal outcome variable was self reported adherence at 6 and 12 weeks, and the trial was analysed on an intention to treat basis. We investigated time to stopping drugs using survival analysis. Assuming that the intervention would increase the proportion of patients continuing drugs at 6 weeks from 35% to 50%, a proportional odds power calculation dictated a sample size of 376 for a power of 90% to detect an effect at 5% (two sided) significance.20

Results

Participant flow and follow up

Of 266 patients referred, eight were excluded (three glaucoma, one recent myocardial infarction, one recent dothiepin treatment, one too confused to consent, two left area immediately after referral) and eight declined to participate, leaving 250 eligible subjects (94%). Thirty seven were allocated to the attention control group, and 213 were randomised (table 1). Eighty eight patients had their adherence monitored; 84 container lids were evaluable.

Table 1.

Flow of patients entered into randomisation

| No intervention |

Leaflet only | Drug counselling only | Leaflet and counselling | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Allocated treatment | 55 | 53 | 52 | 53 | 213 |

| Adherence monitored | 23 | 20 | 23 | 22 | 88 |

| First education visit | — | — | 43 | 46 | 89 |

| Interview 2 (6 weeks) | 53 | 52 | 48 | 53 | 206 |

| Second education visit | — | — | 34 | 39 | 73 |

| Interview 3 (end of main study) | 52 | 51 | 48 | 53 | 204 |

| Full 12 week data (including questionnaire) | 48 | 46 | 46 | 50 | 190 |

The response rate to the bias questionnaire was 77%: six general practitioners (13%) had retired or left the area, and five (10%) did not respond. The commonest reason given for not entering patients was that the general practitioner was “too busy” or “forgot about the study.” General practitioners reported entering fewer patients with chronic depression (54%), comorbid physical illness (51%), postnatal depression (39%), and older patients (25%).

Table 2 shows the characteristics of patients. Half met criteria for major depressive episode within the past month. Almost two thirds had had previous treatment for depression, usually drugs from their general practitioner.

Table 2.

Characteristics of participants at baseline. Values are numbers (percentages) unless stated otherwise

| No intervention (n=55) | Leaflet only (n=53) | Drug counselling only (n=52) | Leaflet and counselling (n=53) | Total (n=213) | Controls (n=37) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years): | ||||||

| Mean | 43.9 | 46.2 | 43.8 | 47.3 | 45.3 | 47.4 |

| Range | (21–78) | (21–81) | (21–83) | (22–83) | (21–83) | (23–72) |

| No of women | 34 (62) | 41 (77) | 42 (81) | 40 (75) | 157 (74) | 25 (68) |

| Social class: | ||||||

| I-IIInm | 26 (47) | 33 (62) | 30 (58) | 31 (58) | 120 (56) | 21 (57) |

| IIIm-V/other | 29 (53) | 20 (38) | 22 (42) | 22 (42) | 93 (44) | 16 (43) |

| Major depression: | ||||||

| Past month | 24 (44) | 25 (47) | 24 (46) | 31 (58) | 104 (49) | — |

| Past 3 months | 27 (49) | 25 (47) | 28 (54) | 32 (60) | 112 (53) | — |

| Mean (SD) hospital anxiety and depression scores: | ||||||

| Anxiety | 12.5 (3.6) | 12.3 (5.0) | 12.5 (4.6) | 13.0 (4.6) | 12.6 (4.4) | — |

| Depression | 9.9 (3.8) | 10.4 (4.9) | 9.7 (4.0) | 10.8 (4.4) | 10.2 (4.3) | — |

| Previous treatment: | ||||||

| Any previous treatment | 29 (53) | 38 (72) | 32 (62) | 34 (64) | 133 (62) | 22 (59) |

| General practitoner prescription | 22 (40) | 31 (58) | 25 (48) | 27 (51) | 105 (49) | 16 (43) |

| Outpatient psychiatry | 4 (7) | 2 (4) | 6 (12) | 5 (9) | 17 (8) | 3 (8) |

| Inpatient psychiatry | 3 (5) | 5 (9) | 1 (2) | 2 (4) | 11 (5) | 3 (8) |

| Tricyclic antidepressants | 8 (15) | 11 (21) | 8 (15) | 7 (13) | 34 (16) | 7 (19) |

| Initial treatment: | ||||||

| Once daily | 52 (95) | 52 (98) | 51 (98) | 53 (100) | 208 (98) | 31 (84 ) |

| Mean (SE) dose (mg) | 53.9 (3.2) | 52.1 (3.6) | 44.9 (3.3) | 47.9 (3.7) | 49.8 (1.7) | 59.6 (7.0) |

Delivery of interventions

Of 105 patients allocated to drug counselling, 89 (85%) received a first visit, and 73 (70%) received both (table 1). Visits were cancelled if drug treatment had been discontinued. At 2 weeks, 11 patients (10%) had discontinued drugs and five patients (5%) refused the visit. At 8 weeks, 20 patients (19%) had stopped drugs and eight (8%) refused. The mean durations of the two visits were 45 (SD 15) min and 33 (SD 13) min.

Patients allocated to receive a leaflet were asked whether they recalled receiving it: 82 (78%) did. Ten patients received more than one leaflet, and 18 not allocated to receive a leaflet reported receiving one from elsewhere (doctor or pharmacist).

Adherence

Table 3 shows self reported adherence to drug treatment. The proportion of controls continuing treatment at week 12 was 19/37 (51%). In logistic regression, allocation to counselling was a significant predictor of self reported adherence (6 weeks: odds ratio 2.1, 95% confidence interval 1.1 to 4.0; 12 weeks: 2.7, 1.6 to 4.8; number needed to treat =4) but allocation to receive a leaflet was not (6 weeks: 1.0, 0.55 to 1.9; 12 weeks: 1.1, 0.64 to 2.0). There was no significant interaction between treatments. Sex, previous treatment, initial depression severity, and drug dose did not materially influence the findings. Subgroup analysis of patients meeting criteria for major depressive episode showed that drug counselling had a significant effect on adherence (χ2= 6.33, df =1, P=0.012) but the leaflet did not.

Table 3.

Proportion of patients reporting continuing treatment at 6 and 12 weeks

| No intervention (n=55) | Leaflet only (n=53) | Drug counselling only (n=52) | Leaflet and counselling (n=53) | Total (n=213) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 6 weeks | 33 (60) | 33 (62) | 41 (79) | 38 (72) | 145 (68) |

| 12 weeks: | |||||

| All patients | 20 (36) | 22 (42) | 34 (65) | 32 (60) | 108 (51) |

| Patients with major depressive episode at outset | 8/24 (33) | 12/25 (48) | 20/24 (83) | 16/31 (52) | 56/107 (52) |

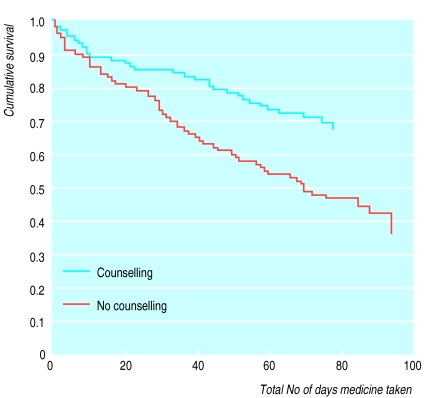

The figure shows the survival analysis. The analysis confirmed that allocation to counselling had a significant effect compared with usual treatment (mean treatment duration 87 (SE 4) v 63 (4) days, log rank test 10.83, df=1, P=0.001; hazard ratio=2.1, 95% confidence interval 1.3 to 3.2); allocation to leaflet had no effect (hazard ratio=1.1, 0.72 to 1.6).

Adherence was monitored in a subgroup of patients to check the validity of self reported adherence. There was no difference in self reported adherence between monitored patients and other patients. Self reported and monitored adherence were significantly related (mean duration of monitored treatment 41.7 (SD 5.8) days in patients reporting continuation compared with 26.1 (SD 15.9) days in those reporting cessation, t=6.6, df=82, P<0.001). In the monitored group there was a trend towards higher adherence among those who had drug counselling (Mann-Whitney z =1.72, P=0.08).

Clinical outcomes

Although counselling increased both self reported and monitored adherence, we found no overall effect on outcome of depression. All patients showed considerable improvement at 12 weeks (depression score 4.6 (SD 4.5) in counselled patients v 5.5 (SD 3.6) in those with no intervention, t=1.55, df=199, P=0.124). However, change in depression score and number of days of treatment were significantly correlated (ρ=0.264, P<0.0001), and patients who had met criteria for major depression at the outset and received doses above the median value of 75 mg had a significant difference in depression score (4.0 (SD 3.7) v 5.9 (SD 5.0), t=2.18, P=0.032).

No overall differences in SF-36 subscales were found, but among patients receiving doses of at least 75 mg drug counselling had a significant effect on scores on the mental health subscale (68.4 (SD 15.8) v 60.8 (SD 22.6), t=1.98, df =97, P=0.05). In subjects who had major depression and received doses of 75 mg or more this difference reached significance (64.9 (SD 14.5) v 54.0 (SD 23.5), t=2.1, df=53, P=0.038). Counselling had no significant effect on the number of general practitioner visits, hospital admissions, or time off work.

Discussion

We assessed adherence to drug treatment in a large representative primary care sample of depressed patients and validated reported adherence by electromechanical monitoring. The overall pattern of adherence was consistent with that reported in previous studies,5,8,9 with 40-50% of patients continuing treatment at 12 weeks. It was practicable for nurses to administer an educational and behavioural intervention in primary care, and this was acceptable to most patients. The nurse intervention raised the proportion of patients continuing treatment at 12 weeks to two thirds.

Leaflets had no effect on adherence, either on their own or in combination with counselling. Although recruitment was slower than demanded by the power calculation, the result was significant because the effect on adherence was greater than predicted. Nurse training took 4 hours but could be reduced with the help of a training manual for private study. No special therapeutic or psychological skills were required.

The methods used reflect the fact that the study was designed to be as naturalistic as possible, yielding background rates of non-adherence in usual clinical practice against which to assess the interventions. The main weakness of this design is that it is impossible to know whether there was significant bias in patient selection by general practitioners. Our attempt to evaluate bias retrospectively suggests that patients with chronic depression, concurrent physical illness, or postnatal depression may have been under-represented. Inclusion of the control group showed that the extra attention given to patients in the main study did not itself improve adherence.

The improvement in adherence produced by counselling was not matched by a significant improvement in clinical outcome or use of service for all patients, but there was evidence that symptoms and health did improve in patients with more severe symptoms receiving higher doses of drugs. Only half the sample met the criteria for major depressive disorder, and over half were receiving drug doses which are believed to be of doubtful efficacy. Further studies are therefore needed to test whether drug counselling would be more beneficial if it included advice about dose of antidepressants and when targeted at patients with at least moderately severe symptoms.

Figure 1.

Survival analysis of adherence to antidepressant treatment in patients allocated to drug counselling and no counselling

Acknowledgments

We thank all the general practitioners who referred patients to the trial. The research nurses were Sabine Heiliger, Cathy Douglas-Wallis, Sandy Staff, and Lynn Timms. Professor Renwick helped with blood level analyses. The study administrators were Jackie Threapleton and Lorna Campbell. Pharmacy assistance was provided by Elizabeth Bere.

Footnotes

Funding: Medical Research Council (grant G9322875). Dothiepin for electromechanically monitored patients was donated by Knoll pharmaceuticals.

Competing interests: None declared.

References

- 1.Robins LN, Helzer JE, Weismann MM, Orvaschel H, Gruenberg E, Burke JD, Regier DA. Lifetime prevalence of specific psychiatric disorders in three sites. Arch Gen Psychiat. 1984;41:949–958. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1984.01790210031005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Murray CJL, Lopez AD. The global burden of disease: a comprehensive assessment of mortality and disability from diseases, injuries and risk factors in 1990 and projected to 2020. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Goldberg DP, Bridges K. Invited review: somatic presentations of psychiatric illness in primary care setting. J Psychosom Res. 1988;32:137–144. doi: 10.1016/0022-3999(88)90048-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hollyman JA, Freeling P, Paykel ES. Double blind placebo controlled trial of amitriptyline among depressed patients in general practice. J R Coll Gen Pract. 1988;38:393–397. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Johnson DAW. Treatment of depression in general practice. BMJ. 1973;266:18–20. doi: 10.1136/bmj.2.5857.18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Johnson DAW. A study of the use of antidepressant medication in general practice. Br J Psychiat. 1974;125:186–192. doi: 10.1192/bjp.125.2.186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Katon W, Von Korff M, Lin E, Bush T, Ormel J. Adequacy and duration of antidepressant treatment in primary care. Med Care. 1992;30:67–76. doi: 10.1097/00005650-199201000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lin EHB, Von Korff M, Katon W, Bush T, Simon GE, Walker E, Robinson P. The role of the primary care physician in patients’ adherence to antidepressant therapy. Med Care. 1995;33:67–74. doi: 10.1097/00005650-199501000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Maddox JC, Levi M, Thompson C. The compliance with antidepressants in general practice. J Psychopharm. 1994;8:48–53. doi: 10.1177/026988119400800108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cramer JA, Spilker B. Patient compliance in medical practice and clinical trials. New York: Raven Press; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Haynes RB, McKibbon KA, Kanani R, Brouwers C, Oliver T. Cochrane Collaboration: Cochrane Library. Oxford: Update Software; 1998. Interventions to assist patients to follow prescriptions for medications. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kemp R, Hayward P, Applewhaite G, Everitt B, David A. Compliance therapy in psychotic patients: a randomised controlled trial. BMJ. 1996;312:345–349. doi: 10.1136/bmj.312.7027.345. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wilkinson G, Allen P, Marshall E, Walker J, Browne W, Mann AH. The role of the practice nurse in the management of depression in general practice: treatment adherence to antidepressant medication. Psychol Med. 1993;23:229–237. doi: 10.1017/s0033291700039027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gibbs S, Waters WE, George CF. The benefits of prescription information leaflets. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 1989;27:723–739. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2125.1989.tb03434.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gibbs S, Waters WE, George CF. The design of prescription information leaflets and feasibility of their use in general practice. Pharm Med. 1987;2:23–34. [Google Scholar]

- 16.European Economic Community. Council directive 92/27/EEC on the labelling of medicinal products for human use and on package leaflets. Official Journal of the European Communitites. 1992;1(113):8–12. [Google Scholar]

- 17.American Psychiatric Association. DSM-III-R. Washington, DC: APA; 1987. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zigmond A, Snaith R. The hospital anxiety and depression scale. Acta Psychiat Scand. 1983;67:361–370. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.1983.tb09716.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ware JE. Measuring patients’ views: the optimum outcome measure. BMJ. 1993;306:1429–1430. doi: 10.1136/bmj.306.6890.1429. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Campbell MJ, Julious SA, Altman DG. Sample sizes for binary, ordered categorical, and continuous outcome in two group comparisons. BMJ. 1995;311:1145–1148. doi: 10.1136/bmj.311.7013.1145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]