Abstract

A total synthesis of phostriecin (2) previously known as sultriecin (1), its structural reassignment as a phosphate versus sulfate monoester, and the assignment of its relative and absolute stereochemistry are disclosed herein. Key elements of the work, which provided first the originally assigned sulfate monoester 1 and then the reassigned and renamed phosphate monoester 2, relied on diagnostic 1H NMR spectroscopic properties of the natural product for the assignment of relative and absolute stereochemistry as well as the subsequent structural reassignment, and a convergent asymmetric total synthesis to provide the unequivocal authentic materials. Key steps of the synthetic approach include a Brown allylation for diastereoselective introduction of the C9 stereochemistry, an asymmetric CBS reduction to establish the lactone C5-stereochemistry, diastereoselective oxidative ring expansion of an α-hydroxyfuran to access the pyran lactone precursor, and single-step installation of the sensitive Z,Z,E-triene unit through a chelation-controlled cuprate addition with installation of the C11 stereochemistry. The approach allows ready access to analogues that can now be used to probe important structural features required for PP2A inhibition, the mechanism of action defined herein.

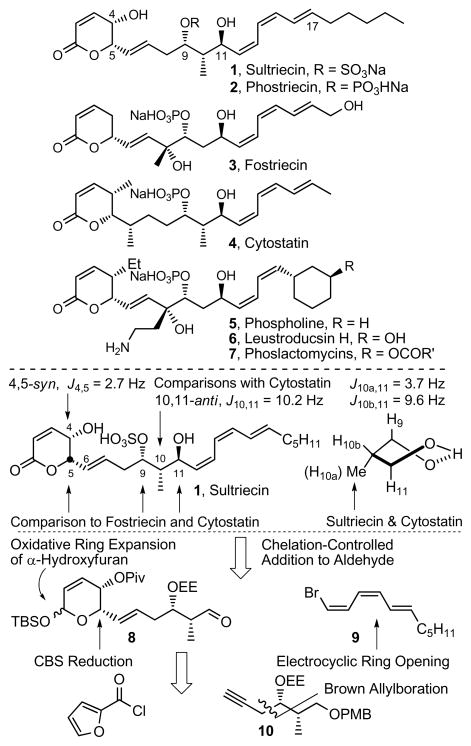

Sultriecin (1)1 was identified as an antitumor antibiotic isolated from Streptomyces roseiscleroticus No. L827-7 and was an early member of a growing family of related natural products2 that now include fostriecin (3),3,4,5 cytostatin (4),6 phospholine (5, phoslactomycin B),7 the leustroducsins (6),8 and the phoslactomycins (7) (Figure 1).9 Sultriecin shares several features with other family members including the characteristic electrophilc α,β-unsaturated lactone and hydrophobic Z,Z,E-triene capping the ends of an extended structure that contains a central, functionalized 1,3-diol. Unique to 1 and in contrast to other family members that contain phosphate monoesters, sultriecin was assigned as a C9 sulfate ester at the time of its disclosure in 1992.

Figure 1.

Top: Natural product structures. Bottom: Assignment of relative and absolute stereochemistry and key retrosynthetic disconnections for sultriecin (1).

In efforts on the synthesis and evaluation of members of this class of antitumor agents that have since been shown to act as protein phosphatase 2A (PP2A) inhibitors, we reported total syntheses of 33c and 4,6c the establishment of their relative and absolute configuration,4,6 and the preparation of a series of analogues used to define structural features that are key to their potent and unusually selective inhibition of PP2A.5,6 Based on its functional biological activity and structural similarity to 3 and 4, we anticipated that 1 would also be a selective PP2A inhibitor, albeit via a sulfate versus phosphate interaction with the enzymatic bimetallic catalytic core. Herein, we report the first total synthesis and stereochemical determination of 1, an unanticipated and requisite structural reassignment of the natural product as phosphate ester 2 (renamed phostriecin), and the establishment that it does in fact represent an effective inhibitor of PP2A.

The structure of sultriecin was disclosed without a definition of its relative or absolute stereochemistry requiring its assignment prior to initiating synthetic efforts (Figure 1). Earlier, we defined the (5S,9S,11S)-stereochemistry for both fostriecin4 and cytostatin,6c and this assignment was extended to sultriecin. As a result of an intramolecular H-bond between the C9-phosphate and C11-OH of fostriecin and cytostatin, the resulting cyclic structure adopts a twist-boat conformation that gives rise to distinct 1H–1H coupling constants between H11 and H10a (syn) or H10b (anti) (J = 3.7 vs 9.6 Hz)4 with only the latter capable of being observed with cytostatin (J = 9.4 Hz)6 and similarly reported for sultriecin (J = 10.2 Hz).1 Thus, we reasoned that sultriecin, like cytostatin and fostriecin, adopts a rigid H-bonded sulfate conformation exhibiting a H11–H10 coupling constant diagnostic of the 10,11-anti configuration establishing the relative stereochemistry of the C10 methyl substituent and confirming the 9,11-anti configuration. Additionally, the H4–H5 coupling constant reported for sultriecin (J = 2.5 Hz) is diagnostic of the cis-C4/C5 (J = 2–3 Hz) versus trans-C4/C5 (J = 8–9 Hz) substitution on the half chair conformation of the lactone10 and is identical to that observed with cytostatin (H4–H5 J = 2.7 Hz).6 Thus, the resulting (4S,5S,9S,10S,11S)-diastereomer of 1 was targeted for synthesis. A convergent route to sultriecin was designed that not only provides ready access to analogues, but also could be adjusted to allow the preparation of any diastereomer in the event that the initial stereochemical assignment proved incorrect. The approach relies on a late-stage single-step installation of the sensitive Z,Z,E-triene via chelation-controlled addition of the cuprate derived from 9 to aldehyde 8. In turn, the protected lactol of 8 was envisioned to arise from an oxidative ring expansion of an α-hydroxyfuran, that could be accessed through the coupling of alkyne 10 with 2-furoyl chloride followed by asymmetric (R)-CBS ketone reduction and stereoselective alkyne reduction (Figure 1).

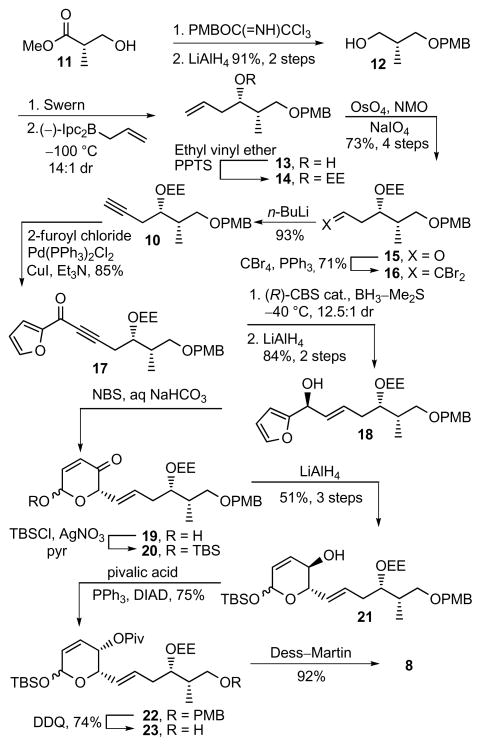

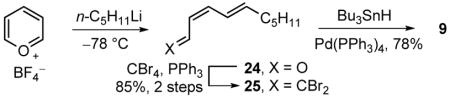

Synthesis of alkyne 10 was initiated with protection of methyl (S)-3-hydroxy-2-methylpropionate (11) as a PMB ether followed by reduction to alcohol 12 (PMBOC(=NH)CCl3, camphorsulfonic acid, CH2Cl2, 25 °C, 12 h; LiAlH4, Et2O, 0–25 °C, 12 h, 91%, 2 steps) (Scheme 1). After oxidation of 12 to the corresponding aldehyde (DMSO, oxalyl chloride, Et3N, CH2Cl2, −78 to 0 °C, 2 h), asymmetric allylboration (allyldiisopinocampheylborane, −100 °C, 4 h; NaOH, H2O2, 25 °C, 16 h, 14:1 dr)11 gave alcohol 13 that was protected as the ethoxyethyl acetal (14) (ethyl vinyl ether, PPTS, CH2Cl2, 25 °C, 2 h). The ethoxyethyl acetal (EE), despite the complicating diastereomeric mixture it introduces, was chosen to direct a subsequent chelation-controlled aldehyde addition and represents a uniquely effective protecting group that is capable of selective removal under mild acidic conditions in the presence of the labile triene and sensitive allylic alcohol. Oxidative cleavage of olefin 14 (OsO4, NaIO4, NMO, THF/H2O, 25 °C, 18 h, 73% for 4 steps) gave aldehyde 15 that was subjected to Corey–Fuchs homologation (CBr4, PPh3, CH2Cl2, 0 °C, 10 min, 71%; n-BuLi, THF, −78 to 25 °C, 16 h, 93%)12 to give alkyne 10. Coupling of 10 with 2-furoyl chloride (Pd(PPh3)2Cl2, CuI, Et3N, 25 °C, 24 h, 85%)13 provided ketone 17 that was subjected to asymmetric reduction (methyl-(R)-CBS-oxazaborolidine,14 BH3–Me2S, THF, −40 °C, 3 h, 12.5:1 dr) setting the C5 stereochemistry and was followed by stereoselective reduction15 of the alkyne (LiAlH4, THF, 0 to 25 °C, 24 h, 84%, 2 steps) to the trans olefin 18. The analogous asymmetric CBS reduction of the corresponding α,β-unsaturated ketone with the trans double bond already installed to provide 18 directly was much less diastereoselective (ca. 2.5:1 dr). Intermediate 21 was obtained as a mixture of anomers following oxidative ring expansion of 18 (NBS, NaHCO3/NaOAc, THF/H2O, 0 °C, 1 h),16 TBS protection of resultant lactol 19 (TBSCl, AgNO3, pyr, CH2Cl2, 25 °C, 15 min),17 and diastereoselective reduction of ketone 20 (LiAlH4, Et2O, −60 °C, 2.5 h, 51–64% for 3 steps). The stereochemistry of the resulting C4 alcohol was necessarily inverted and directly protected as its pivalate ester using the Mitsunobu reaction (DIAD/Ph3P, pivalic acid, THF, 0 to 25 °C, 75%).18 Aldehyde 8 was obtained following PMB removal (DDQ, CH2Cl2/H2O, 25 °C, 1 h, 74%) and oxidation of alcohol 23 (DMP, CH2Cl2, 25 °C, 1 h, 92%).19 Following an approach developed by Taylor and adopted in our total synthesis of cytostatin,20 pyrilium tetrafluoroborate was treated with n-pentyllithium (THF, −78 °C, 4 h) giving, after room temperature electrocyclic ring opening of the adduct, the Z,E-aldehyde 24 as a single isomer (Equation 1). Aldehyde 24 was converted to 9 via dibromoolefination (CBr4, PPh3, Et3N, CH2Cl2, 0 °C, 15 min, 85% for 2 steps)12 and selective E-bromide reduction (Bu3SnH, Pd(PPh3)4, Et2O, 0 °C, 45 min, 78%).21

Scheme 1.

Synthesis of 8.

|

(1) |

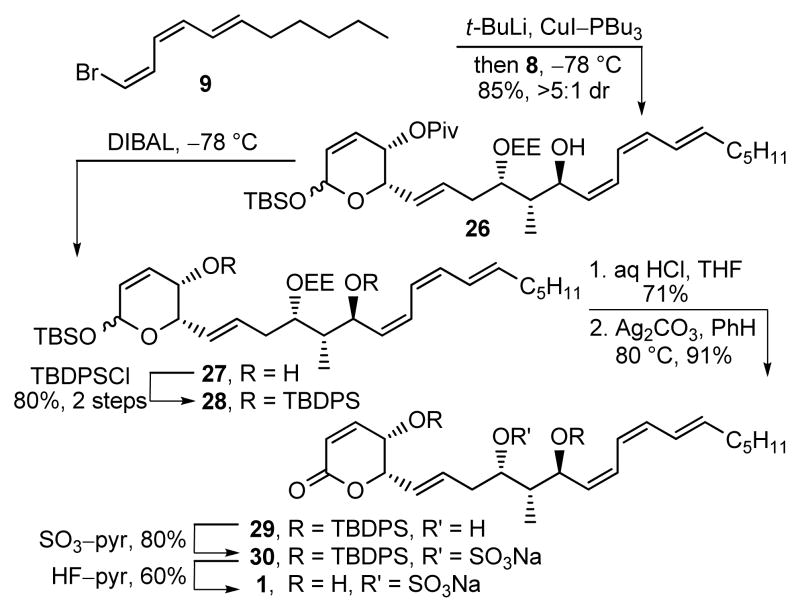

Incorporation of the sensitive Z,Z,E-triene tail commenced with conversion of 9 to the corresponding cuprate (t-BuLi, Et2O, −78 °C, 1 h; CuI–PBu3, Et2O, −78 °C, 15 min) followed by slow addition of aldehyde 8 (Et2O, −78 °C, 1 h, 85%, >5:1 dr), providing 26 derived from chelation-controlled addition to the aldehyde (Scheme 2).6c,22 Removal of the pivalate ester (DIBAL, CH2Cl2, −78 °C, 2 h) followed by silylation of the secondary alcohols of 27 (TBDPSCl, AgNO3, pyr/CH2Cl2, 25 °C, 16 h, 80%, 2 steps) afforded 28 that was treated with dilute HCl (THF/H2O, 25 °C, 12 h, 71%) to simultaneously and selectively remove the EE and TBS protecting groups. The resulting lactol was selectively oxidized to give lactone 29 (Ag2CO3–Celite, benzene, 80 °C, 1.5 h, 91%). Sulfate ester introduction (SO3–pyr, THF, 25 °C, 80%) followed by desilylation (HF–pyr, pyr/THF, 25 °C, 60%) gave 1, which did not match the spectroscopic (1H NMR, 13C NMR, IR) or physical characteristics (TLC, [α]D, solubility, stability to silica gel) reported for the natural product.

Scheme 2.

Synthesis of 1 (sultriecin).

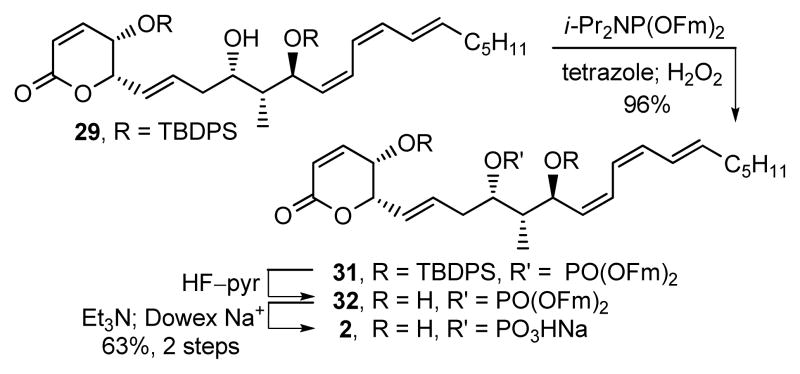

Although several possibilities for this non-correlation with the natural product could be envisioned including the accuracy of our stereochemical assignments as well as spectroscopic perturbations derived from the protonation state or salt form of the sulfate, the only real distinctive difference observed in the 1H NMR of synthetic 1 and the natural product was the chemical shift (CD3OD, δ 4.82 vs 4.64) and multiplicity (ddd, J = 8.4, 6.0, 1.8 Hz vs dddd, J = 9.6, 7.8, 7.2, 1.8 Hz) of C9-H adjacent to the putative sulfate ester. Diagnostic of what proved to be a required structural reassignment, the C9-H of the natural product exhibited an additional long range coupling (JP-H9 = 7.8 Hz) characteristic of a phosphate (monoisotopic mass = 492.1889) versus sulfate ester (monoisotopic mass = 492.1794).23 Consequently, phosphate ester 2 was targeted for synthesis (Scheme 3). Alcohol 29 was phosphorylated (i-Pr2NP(OFm)2, tetrazole, CH2Cl2/CH3CN, 25 °C, 1 h; H2O2, 15 min, 96%)6 to give 31 that was desilylated (HF–pyr, pyr/THF, 25 °C, 4 d). Removal of the fluorenylmethyl groups in 32 (Et3N, CH3CN, 25 °C, 16 h; Dowex Na+, 63% for 2 steps) unmasked the phosphate giving 2 (phostriecin), that proved identical to the reported properties of 1 as well as a sample24 of natural “sultriecin” (1H NMR, 31P NMR, [α]D, TLC, HPLC, HRMS), the latter of which displayed a 31P NMR signal like that found with synthetic 2 (δ 3.4, CD3OD).

Scheme 3.

Synthesis of 2 (phostriecin).

Thus, the total syntheses of 1 and 2 led to an unequivocal reassignment of the structural composition and established the relative and absolute stereochemical configuration of the natural product (renamed phostriecin) heretofore known as sultriecin. Key steps include a Brown allylation with controlled introduction of the C9 stereochemistry, a CBS reduction to establish the lactone C5-stereochemistry, diastereoselective oxidative ring expansion of an α-hydroxyfuran to access the pyran lactone precursor, and single-step installation of the sensitive triene unit through a chelation-controlled cuprate addition with installation of the C11 stereochemistry. This approach also allows ready access to analogues that can now be used to probe important structural features required for PP2A inhibition, the mechanism of action defined herein.25 These and related studies will be reported in due course.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We gratefully acknowledge the financial support of the National Institutes of Health (CA042056). We wish to thank Danielle R. Soenen for initiating the studies on sultriecin, Dr. Ernest Lacey (Bioaustralis) for helpful discussions, and Professor Richard E. Honkanen for the PP2A inhibition studies. NH was a Skaggs Fellow.

Footnotes

Supporting Information Available: Full experimental details are provided. This material is available free of charge via the Internet at http://pubs.acs.org.

References

- 1.Ohkuma H, Naruse N, Nishiyama Y, Tsuno T, Hoshino Y, Sawada Y, Konishi M, Oki T. J Antibiot. 1992;45:1239. doi: 10.7164/antibiotics.45.1239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lewy DS, Gauss CM, Soenen DR, Boger DL. Curr Med Chem. 2002;9:2005. doi: 10.2174/0929867023368809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Isolation: Tunac JB, Graham BD, Dobson WE. J Antibiot. 1983;36:1595. doi: 10.7164/antibiotics.36.1595.Stampwala SS, Bunge RH, Hurley TR, Willmer NE, Brankiewicz AJ, Steinman CE, Smitka TA, French JC. J Antibiot. 1983;36:1601. doi: 10.7164/antibiotics.36.1601.. Total syntheses: Boger DL, Ichikawa S, Zhong W. J Am Chem Soc. 2001;123:4161. doi: 10.1021/ja010195q.Chavez DE, Jacobsen EN. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2001;40:3667. doi: 10.1002/1521-3773(20011001)40:19<3667::aid-anie3667>3.0.co;2-6.Reddy YK, Falck JR. Org Lett. 2002;4:969. doi: 10.1021/ol025537r.Miyashita K, Ikejiri M, Kawasaki H, Maemura S, Imanishi T. Chem Commun. 2002:742. doi: 10.1039/b201302a.Miyashita K, Ikejiri M, Kawasaki H, Maemura S, Imanishi T. J Am Chem Soc. 2003;125:8238. doi: 10.1021/ja030133v.Esumi T, Okamoto N, Hatakeyama S. Chem Commun. 2002:3042. doi: 10.1039/b209742g.Fujii K, Maki K, Kanai M, Shibasaki M. Org Lett. 2003;5:733. doi: 10.1021/ol027528o.Trost BM, Frederiksen MU, Papillon JP, Harrington PE, Shin S, Shireman BT. J Am Chem Soc. 2005;127:3666. doi: 10.1021/ja042435i.Maki K, Motoki R, Fujii K, Kanai M, Kobayashi T, Tamura S, Shibasaki M. J Am Chem Soc. 2005;127:17111. doi: 10.1021/ja0562043.Yadav JS, Prathap I, Tadi BP. Tetrahedron Lett. 2006;47:3773.Hayashi Y, Yamaguchi H, Toyoshima M, Okado K, Toyo T, Shoji M. Org Lett. 2008;10:1405. doi: 10.1021/ol800195g.Sarkar SM, Wanzala EN, Shibahara S, Takahashi K, Ishihara J, Hatakeyama S. Chem Comm. 2009:5907. doi: 10.1039/b912267b.Robles O, McDonald FE. Org Lett. 2009;11:5498. doi: 10.1021/ol902365n.

- 4.(a) Boger DL, Hikota M, Lewis BM. J Org Chem. 1997;62:1748. [Google Scholar]; (b) Hokanson GC, French JC. J Org Chem. 1985;50:462. [Google Scholar]

- 5.(a) Buck SB, Hardouin C, Ichikawa S, Soenen DR, Gauss CM, Hwang I, Swingle MR, Bonness KM, Honkanen RE, Boger DL. J Am Chem Soc. 2003;125:15694. doi: 10.1021/ja038672n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Swingle MB, Amable L, Lawhorn BG, Buck SB, Burke CP, Ratti P, Fisher KL, Boger DL, Honkanen RE. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2009;331:45. doi: 10.1124/jpet.109.155630. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Isolation: Amemiya M, Someno T, Sawa R, Naganawa H, Ishizuka M, Takeuchi T. J Antibiot. 1994;47:541. doi: 10.7164/antibiotics.47.541.Amemiya M, Ueno M, Osono M, Masuda T, Kinoshita N, Nishida C, Hamada M, Ishizuka M, Takeuchi T. J Antibiot. 1994;47:536. doi: 10.7164/antibiotics.47.536.. Total syntheses: Lawhorn BG, Boga SB, Wolkenberg SE, Colby DA, Gauss CM, Swingle MR, Amable L, Honkanen RE, Boger DL. J Am Chem Soc. 2006;128:16720. doi: 10.1021/ja066477d.Lawhorn BG, Boga SB, Wolkenberg SE, Boger DL. Heterocycles. 2006;70:65.Bialy L, Waldmann H. Chem Eur J. 2004;10:2759. doi: 10.1002/chem.200305543.Bialy L, Waldmann H. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2002;41:1748. doi: 10.1002/1521-3773(20020517)41:10<1748::aid-anie1748>3.0.co;2-x.Jung WH, Guyenne S, Riesco-Fagundo C, Mancuso J, Nakamura S, Curran DP. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2008;47:1130. doi: 10.1002/anie.200704893.

- 7.Isolation: Ozasa T, Tanaka K, Sasamata M, Kaniwa H, Shimizu M, Matsumoto H, Iwanami M. J Antibiot. 1989;42:1339. doi: 10.7164/antibiotics.42.1339.. Total syntheses: Wang YG, Takeyama R, Kobayashi Y. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2006;45:3320. doi: 10.1002/anie.200600458.Shibahara S, Fujino M, Tashiro Y, Takahashi K, Ishihara J, Hatakeyama S. Org Lett. 2008;10:2139. doi: 10.1021/ol8004672.

- 8.Isolation: Kohama T, Enokita R, Okazaki T, Miyaoka H, Torikata A, Inukai M, Kaneko I, Kagasaki T, Sakaida Y, Satoh A, Shiraishi A. J Antibiot. 1993;46:1503. doi: 10.7164/antibiotics.46.1503.Kohama T, Nakamura T, Kinoshita T, Kaneko I, Shiraishi A. J Antibiot. 1993;46:1512. doi: 10.7164/antibiotics.46.1512.. Total syntheses: Matsuhashi H, Shimada K. Tetrahedron. 2002;58:5619.Shimada K, Kaburagi Y, Fukuyama T. J Am Chem Soc. 2003;125:4048. doi: 10.1021/ja0340679.Miyashita K, Tsunemi T, Hosokawa T, Ikejiri M, Imanishi T. J Org Chem. 2008;73:5360. doi: 10.1021/jo8005599.

- 9.Isolation: Fushimi S, Nishikawa S, Shimazu A, Seto H. J Antibiot. 1989;42:1019. doi: 10.7164/antibiotics.42.1019.. Total synthesis: König CM, Gebhardt B, Schleth C, Dauber M, Koert U. Org Lett. 2009;11:2728. doi: 10.1021/ol900757k.

- 10.Yang ZC, Jiang XB, Wang ZM, Zhou WS. J Chem Soc, Perkin Trans 1. 1997:317. [Google Scholar]

- 11.(a) Racherla US, Brown HC. J Org Chem. 1991;56:401. [Google Scholar]; (b) Nicolaou KC, Patron AP, Ajito K, Richter PK, Khatuya H, Bertinato P, Miller RA, Tomaszewski MJ. Chem Eur J. 1996;2:847. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Corey EJ, Fuchs PL. Tetrahedron Lett. 1972;13:3769. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tohda Y, Sonogashira K, Hagihara N. Synthesis. 1977:777. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Corey EJ, Bakshi RK, Shibata S. J Am Chem Soc. 1987;109:5551. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Corey EJ, Katzenellenbogen JA, Posner GH. J Am Chem Soc. 1967;89:4245. [Google Scholar]

- 16.(a) Georgiadis MP, Couladouros EA. J Org Chem. 1986;51:2725. [Google Scholar]; (b) Babu RS, Zhou M, O’Doherty GA. J Am Chem Soc. 2004;126:3428. doi: 10.1021/ja039400n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hakimelahi GH, Proba ZA, Ogilvie KK. Tetrahedron Lett. 1981;22:4775. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mitsunobu O. Synthesis. 1981:1. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Dess DB, Martin JC. J Am Chem Soc. 1991;113:7277. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Belosludtsev YY, Borer BC, Taylor RJK. Synthesis. 1991:320. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Uenishi J, Kawahama R, Yonemitsu O, Tsuji J. J Org Chem. 1998;63:8965. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Still WC, Schneider JA. Tetrahedron Lett. 1980;21:1035. [Google Scholar]

- 23.It also explains the observation (ref. 6c) that the corresponding sulfate of cytostatin (sulfocytostatin) was found to be inactive against PP2A.

- 24.Commercially available from Bioaustralis.

- 25.PP2A inhibition (IC50): 1 (>100 >M), 2 (0.72 μM).

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.