Abstract

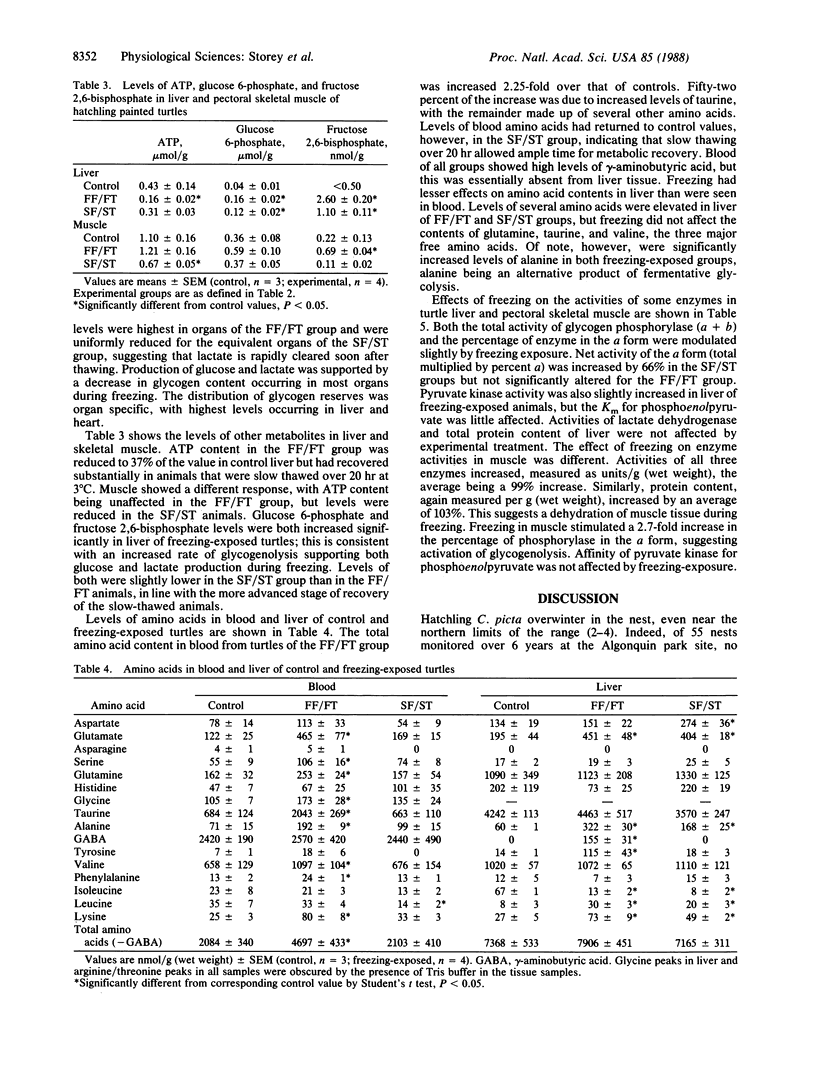

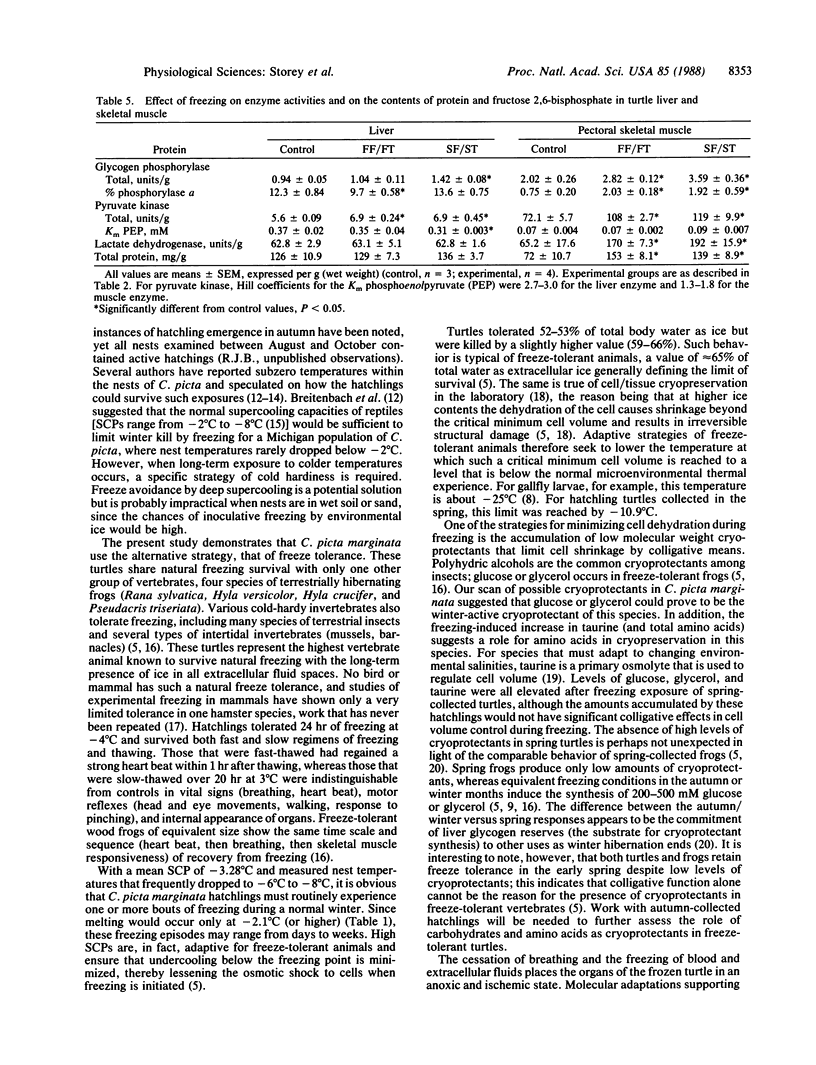

Hatchlings of the painted turtle (Chrysemys picta marginata) are unique as the only reptile and highest vertebrate life form known to tolerate the natural freezing of extracellular body fluids during winter hibernation. Turtles survived frequent exposures to temperatures as low as -6 degrees C to -8 degrees C in their shallow terrestrial nests over the 1987-1988 winter. Hatchlings collected in April 1988 had a mean supercooling point of -3.28 +/- 0.24 degrees C and survived 24 hr of freezing at -4 degrees C with 53.4% +/- 1.98% of total body water as ice. Recovery appeared complete after 20 hr of thawing at 3 degrees C. However, freezing at -10.9 degrees C, resulting in 67% ice, was lethal. A survey of possible cryoprotectants revealed a 2- to 3-fold increase in glucose content of liver and blood and a 3-fold increase in blood glycerol in response to freezing. Although quantitatively low, these responses by spring turtles strongly indicate that these may be the winter-active cryoprotectants. The total amino acid pool of blood also increased 2.25-fold in freezing-exposed turtles, and taurine accounted for 52% of the increase. Most organs accumulated high concentrations of lactate during freezing, a response to the ischemic state imposed by extracellular freezing. Changes in glycogen phosphorylase activity and levels of glucose 6-phosphate and fructose 2,6-bisphosphate were also consistent with a dependence on anaerobic glycolysis during freezing. Studies of the molecular mechanisms of natural freeze tolerance in these turtles may identify protective strategies that can be used in mammalian organ cryopreservation technology.

Full text

PDF

Selected References

These references are in PubMed. This may not be the complete list of references from this article.

- Lowe C. H., Lardner P. J., Halpern E. A. Supercooling in reptiles and other vertebrates. Comp Biochem Physiol A Comp Physiol. 1971 May 1;39(1):125–135. doi: 10.1016/0300-9629(71)90352-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mazur P. Freezing of living cells: mechanisms and implications. Am J Physiol. 1984 Sep;247(3 Pt 1):C125–C142. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.1984.247.3.C125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Storey K. B. Regulation of liver metabolism by enzyme phosphorylation during mammalian hibernation. J Biol Chem. 1987 Feb 5;262(4):1670–1673. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Storey K. B., Storey J. M. Freeze tolerance in animals. Physiol Rev. 1988 Jan;68(1):27–84. doi: 10.1152/physrev.1988.68.1.27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vislie T. Cell volume regulation in fish heart ventricles with special reference to taurine. Comp Biochem Physiol A Comp Physiol. 1983;76(3):507–514. doi: 10.1016/0300-9629(83)90453-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]