Abstract

Photon absorption by photoreceptors activates hydrolysis of cGMP, which shuts down cGMP-gated channels and decreases free Ca2+ concentrations in outer segment. Suppression of Ca2+ influx through the cGMP channel by light activates retinal guanylyl cyclase through guanylyl cyclase activating proteins (GCAPs) and thus expedites photoreceptors recovery from excitation and restores their light sensitivity. GCAP1 and GCAP2, two ubiquitous among vertebrate species isoforms of GCAPs that activate retGC during rod response to light, are myristoylated Ca2+/Mg2+-binding proteins of the EF-hand superfamily. They consist of one non-metal binding EF-hand-like domain and three other EF-hands, each capable of binding Ca2+ and Mg2+. In the metal binding EF-hands of GCAP1, different point mutations can selectively block binding of Ca2+ or both Ca2+ and Mg2+ altogether. Activation of retGC at low Ca2+ (light adaptation) or its inhibition at high Ca2+ (dark adaptation) follows a cycle of Ca2+/Mg2+ exchange in GCAPs, rather than release of Ca2+ and its binding by apo-GCAPs. The Mg2+ binding in two of the EF-hands controls docking of GCAP1 with retGC1 in the conditions of light adaptation and is essential for activation of retGC. Mg2+ binding in a C-terminal EF-hand contributes to neither retGC1 docking with the cyclase nor its subsequent activation in the light, but is specifically required for switching the cyclase off in the conditions of dark adaptation by binding Ca2+. The Mg2+/Ca2+ exchange in GCAP1 and 2 operates within different range of intracellular Ca2+ concentrations and provides a two-step activation of the cyclase during rod recovery.

Keywords: Photoreceptor, Guanylyl cyclase, Retina, Ca2+, Mg2+, GCAP, Calcium-binding proteins

GCAPs and guanylyl cyclase activation in photoreceptor recovery

In visual phototransduction in vertebrate rods and cones, photon absorption by rhodopsin or cone visual pigments triggers hydrolysis of cGMP by activating a transducinphosphodiesterase 6 (PDE6) cascade, which results in closure of the cGMP-gated cation channels (CNG) in the plasma membrane and membrane hyperpolarization (Fig. 1, reviewed in [1-3]). In order to reset the sensitivity of photoreceptor, cGMP levels are quickly restored in photo-bleached rods [4-7] by retina-specific guanylyl cyclase (retGC), a membrane enzyme present in rod and cone outer segments [8-10]. Whereas other members of membrane guanylyl cyclase family are regulated by their extracellular ligands, such as peptide hormones (reviewed in [11, 12]), in the photoreceptor cyclase its extracellular segment (most of which is likely to be exposed into the intradiskal space of the photoreceptor disks) does not reveal the ability to bind extracellular peptide hormones. Instead, retGC is a Ca2+-regulated enzyme whose activity is controlled via the intracellular domains [13-15], conferred by soluble EF-hand sensor proteins, called guanylyl cyclase activating proteins (GCAPs) [7, 8, 16-19].

Fig. 1.

Ca2+ feedback and cGMP synthesis in photoreceptors. Explanations are provided in the text

The feedback triggering activation of cGMP resynthesis results from a steep decline in free Ca2+ levels in photoreceptors between dark and light (Fig. 1). Photoexcitation, via closure of CNG channels and Ca2+ removal by Ca2+/Na+ exchanger, decreases the free intracellular Ca2+ in rods and cones nearly 10-fold [20, 21], in mouse rods—from ~250 nM in the dark to ~25 nM in the light [22, 23]. Catalytic activity of retGC in the dark is negatively controlled by Ca2+-bound GCAPs [4, 24-26] and requires the release of Ca2+ from GCAPs in the light to convert GCAPs in the form that stimulates retGC instead of inhibiting it [4, 8, 16-18, 24, 27]. Activity of cGMP production in rods stimulated by GCAPs in the light increases 10–12-fold [4, 5] and is the most important reaction controlled by the Ca2+ feedback during a single-photon response [2, 4]. Activation of retGC by GCAPs restrains the amplitude of a single-photon response and therefore begins during the rising phase of the photoresponse, virtually as soon as Ca2+ starts to fall in response to illumination [4, 27].

Activation and inhibition of the photoreceptor guanylyl cyclase between light and dark is a result of Mg2+/Ca2+ exchange in GCAPs

Several GCAP variants have been identified in vertebrate retinas [8, 17, 28, 29], and two of these homologs, GCAP1 and GCAP2, are found in all tested vertebrate species. GCAPs, related to a group of recoverin-like proteins, are N-fatty acylated and contain one non-metal binding EF-hand-like domain (EF1) and three metal binding EF-hands (EF2-4) (Fig. 2) capable of binding Ca2+ or Mg2+ [26]. Since Ca2+ and Mg2+ coordination involves slightly different polar groups from the amino acid residues in the EF-hand loop, we used mutations that either block Ca2+ binding without blocking Mg2+ binding or block Mg2+ binding as well (Fig. 3a) to determine the role of these cations in retGC regulation by GCAP1 [26, 30]. Inactivation of Ca2+ binding in EF-hand loops by point mutations makes GCAP1 and −2 into constitutive activators of RetGC, capable of accelerating RetGC and insensitive to the inhibition by Ca2+ [24, 26, 30, 31] (Fig. 3). In contrast to that, mutations that disable not only Ca2+ but also Mg2+ binding [30] eliminate the GCAP ability to stimulate RetGC (Fig. 3a, b). It is therefore binding of Mg2+ to the apo-form of GCAP1 what makes it into a RetGC activator state, and not only dissociation of Ca2+ but also its replacement by Mg2+ is required to convert GCAP into a RetGC activator in the light. Mg2+ binding makes GCAP1 conformation drastically different from its apo form, as revealed by Trp fluorescence, microcalorimetry, and NMR analyses [26, 30, 32]. Trp fluorescence spectrum of GCAP1 also changes differently in response to Mg2+ versus Ca2+ binding, by lacking a component that correlates with the transition of GCAP1 into a Ca2+ bound, inhibitory state [30, 33]. It is important to emphasize that blocking of Mg2+ binding in any individual EF-hand by point mutations does not cause a non-specific misfolding of GCAP1 as a result of those mutations, but rather specifically prevents the mutated EF-hand from assuming its proper cation-bound conformation, because: (i) different combinations of point mutations that block Mg2+ binding in the same EF-hand affect GCAP properties in a similar fashion, (ii) mutating any particular EF-hand does not eliminate conformational changes in GCAP1 as a result of cation binding in other parts of the molecule detected by Trp fluorescence, and (iii) mutating an EF-hand in one semi-globule of GCAP1 does not eliminate either Ca2+ or Mg2+ binding in EF-hands located in the opposite, non-mutated half of the molecule [26, 30, 32].

Fig. 2.

Three-dimensional structure of GCAP1 [41] and GCAP2 [40]. GCAPs comprise two semi-globular halves formed by two pairs of EF-hand structures (EF-1+EF-2 and EF-3+EF-4), numbered beginning from the N-terminus in primary structure. Spheres represent divalent cation bound in EF-hand loops. The loop in the first EF-hand domain lacks some key consensus side chain residues required for coordinating the metal ions. The arrows indicate the positions of two mutations associated with congenital blindness, Y99C and E155G. Other explanations are given in the text

Fig. 3.

Mg2+ binding makes GCAP1 into RetGC activator in the conditions of light adaptation whereas Ca2+ binding is required to decelerate the cyclase at high Ca2+ concentrations typical for dark-adapted rods (from [26, 30]). a Mutations in 12-amino acid EF-had loops of each of EF-hands 2, 3, and 4 that can disable either Ca2+ or both Ca2+ and Mg2+ binding [26] in EF-hand loops of bovine GCAP1. b Activation of recombinant RetGC1 by mutant forms GCAP1 was assayed in vitro at different free Ca2+ concentrations in the presence of Ca/Mg/EGTA buffer maintaining Mg2+ at near 5 mM level. Wild-type GCAP1 (open circle) produces maximal retGC activity below 200 nM free Ca2+ but decelerates it as Ca2+ rises; inactivation of only Ca2+ binding turns GCAP1 into a Ca2+-insensitive Mg2+-bound activator of RetGC (filled square), whereas mutations preventing both Ca2+ and Mg2+ binding turn GCAP1 into an apo-form and completely block activation of RetGC (filled triangle). c Cation binding cycle in GCAP1 as it undergoes transitions between the RetGC activator and inhibitor states, driven by light versus dark exposure of photoreceptors. Other explanations are given in the text

While GCAPs bind Ca2+ within submicromolar range (KdCa ~ 0.06–0.2 μM), they also efficiently bind Mg2+ within submillimolar range (KdMg ~ 0.2 mM for GCAP1) [26, 30, 32, 33] and, therefore, can be turned into Mg2+-bound form at the physiological intracellular Mg2+ concentrations in vertebrate rods and cones (~0.9 mM; [34]). Despite its much lower intracellular concentrations, Ca2+ binds with much higher affinity to GCAPs, and in the dark its concentration is high enough to efficiently compete with Mg2+ and replace it in EF-hands. However, because the free Ca2+ concentrations sharply fall after illumination and those of Mg2+ remain near 1 mM [34], Mg2+ becomes able to replace Ca2+ in EF-hands in the light and thus create the state of GCAP required for stimulation of RetGC activity [26, 30, 33]. At the physiological concentrations of Mg2+ and Ca2+, GCAP1 in photoreceptors simply cannot stably exist as an apo-protein [33]. Therefore, as photoreceptors repeatedly respond to the decrease and increase of illumination by opening and closing their cGMP-gated channels, which is translated into the rise and fall in their free Ca2+ concentrations, GCAPs must correspondingly undergo cyclic changes between their Ca2+-bound (retGC inhibitor) and Mg2+ -bound (retGC activator) states (Fig. 3c) resulted from the competition between Mg2+ and Ca2+ for the same binding centers in GCAP molecule.

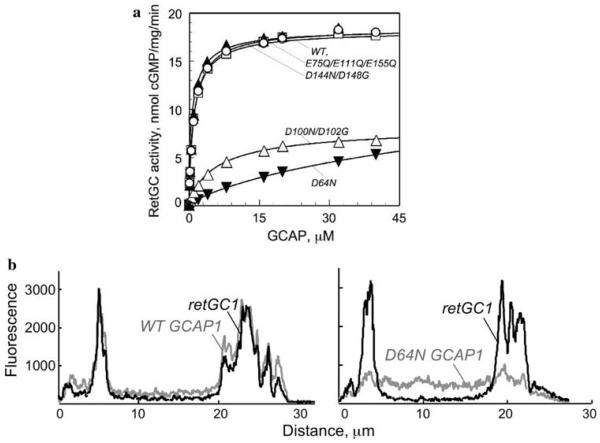

Recent observations directly indicate that cation binding in EF-hands is critical for proper docking of GCAP1 with RetGC, such that if GCAP1 did not have the ability to bind Mg2+, a dissociation of Ca2+ would merely render GCAP1 inactive in the light, rather than allow it to maintain a complex with the cyclase as its activator. There are two lines of evidence in support of this model: (i) the apparent affinity of RetGC for GCAP1 drops when the Mg2+ binding is blocked in EF-hand 3 and especially EF-hand 2 [26] and (ii) when Mg2+ binding is blocked in EF-hand 2, GCAP1 is unable to efficiently co-localize with RetGC1 when both proteins are co-expressed in transfected HEK293 cells (Fig. 4) [35].

Fig. 4.

Effects of Mg2+ binding prevention in individual EF-hands (reproduced from [35] with minor modifications). a Inactivation of Mg2+ binding in EF-hands 2 and 3, but not in EF-hand 4 inhibits RetGC1 activation by GCAP1. Mutations blocking only Ca2+ binding in all three EF-hands (open circle) or inactivation of both Ca2+ and Mg2+ binding in EF-hand 4 (filled triangle) do not alter RetGC activation by GCAP1 (wt, open square). Mutation blocking both Ca2+ and Mg2+ binding in EF-hand 3 (open triangle) and especially EF-hand 2 (filled inverted triangle) suppress activation of RetGC1; measured at constant 5 mM free Mg2+ and <20 nM free Ca2+. For other details see reference [35]. b Inactivation of Mg2+ binding in EF-hand 2 suppresses docking of GCAP1-GFP with RetGC1 in cultured cells (modified from [35]). RetGC1 was co-expressed in transfected HEK293 cells with GFP-tagged GCAP1, either wild type (left) or its D64N mutant (right), incapable of binding Mg2+ in EF-hand 2. Distribution of the GFP tag green fluorescence and anti-RetGC1 red immunofluorescence was recorded across each cell. For other details see [35]

Binding of Mg2+ versus Ca2+ causes a characteristic change in the intrinsic Trp fluorescence of GCAP1 [33, 36, 37] corresponding to its activator versus inhibitor states [26, 30]. This change includes shifting between more polar versus non-polar environment of a conserved Trp residue located in the non-metal binding EF-hand 1 of GCAPs [26, 30]. Based on its Trp fluorescence alterations between apo form of GCAP1 and its Mg2+ bound form, in GCAP1 the conformation of EF1 domain is directly sensitive to Mg2+ binding in EF-hand 2 [26, 30]. Interestingly, the EF-hand 1 domain has been implicated as an element of GCAP structure required for its interaction with RetGC [38, 39]. Since cation binding in EF-hand 2 is both necessary for efficient docking of GCAP1 with retGC and strongly affects the conformation of EF-hand 1 as its neighboring domain, it seems reasonable to suggest that both EF-hand domains together create the “docking” structure in GCAP1 required for its primary binding with RetGC1 [35].

In a striking contrast to EF-hands 2 and 3, whose inactivation affects GCAP1 interaction with RetGC1, prevention of Mg2+ binding in EF-hand 4 has no detectable effect on RetGC activation. When Ca2+ binding is inactivated in EF-hand 4, GCAP1 becomes a constitutive activator of RetGC, regardless of whether or not EF-4 binds Mg2+ [26, 30] (Fig. 4a). Therefore, only EF-hands 2 and 3 are likely required to maintain their cation-bound state in the light to preserve the GCAP complex with RetGC, while Mg2+ binding in the EF-hand 4 is unlikely to have any structural role in the cyclase activation. What is then the function of the metal binding in EF-hand 4? Evidently, Ca2+ binding in this EF-hand is critical for deceleration of RetGC in the dark, when the Ca2+ concentrations rise. Inactivation of Ca2+ binding in EF-hand 2 does not produce any major effect on RetGC regulation as long as Mg2+ binding is permitted in that EF-hand, but the Ca2+-dependent RetGC turn-off in the dark does require that both EF-hands 3 and 4 assume their Ca2+-bound conformations [26, 30, 31]. An important property of GCAPs is that the two halves of the protein molecule are each formed by two pairs of EF-hands connected by a flexible hinge region (Fig. 2) [40-43]. In GCAP1, EF-hand 3 and 4 operate together as a single Ca2+ binding semi-globule “module” converting GCAP1 into its inhibitor conformation, such that binding of Ca2+ in EF-3 domain promotes the subsequent Ca2+ binding in the neighboring EF-hand 4, but not vice versa [30, 32]. Mutations suppressing Ca2+ binding in EF-3 and EF-4 domains of GCAP1 even associate with congenital cone degenerations in humans and result in photoreceptor death in transgenic mice expressing mutant GCAP1 through the abnormal elevation of cGMP and free Ca2+ in photoreceptors in the dark [25, 44-48] (the position for the first two such mutations in GCAP1 that were found in human patients, Y99C and E155G [44, 45], are shown by arrows in Fig. 2). Even though Mg2+ binding in EF-4 of GCAP1 in the light is not required for creating the proper “RetGC activator” conformation per se, it nevertheless could be physiologically significant, because Mg2+ binding would accelerate the transition of the inhibitor state into the activator state in the light by competing with Ca2+ in this EF-hand and thus expediting the release of GCAP1 from its inhibitor conformation.

The sensitivity of Ca2+/Mg2+ exchange in two different GCAP isoforms

There are two homologous isozymes of RetGC in the retina, RetGC1 and RetGC2 [9], also known as GC-E and GC-F [10] or ROS-GC1 and ROS-GC2 [49]. RetGC1, the first identified GCAP-regulated isozyme [8], seems to provide most of cGMP synthetic activity in cones and is critical for their survival [50]. The exact contribution of RetGC1 versus RetGC2 in rods remains to be determined. Both RetGC1 and 2 are present in outer segments [8, 51, 52] and both accelerate rod recovery from light exposure [52]. In addition to that there are several isoforms of GCAPs [29] in photoreceptors, of which GCAP1 and GCAP2 are ubiquitously present among vertebrates. Some explanations for such a complexity can be drawn from the Ca2+/Mg2+ exchange sensitivity in different GCAPs (Fig. 5). Competition between Mg2+ and Ca2+ ions for the same binding sites in EF-hands has a strong effect on the regulatory properties of GCAP1 and 2, and the efficiency of the Ca2+/Mg2+ exchange in different isoforms may explain the need in multiple sensor proteins being involved in fine RetGC regulation in photoreceptors to provide the proper recovery kinetics and light adaptation. GCAP1 has lower and GCAP2 higher apparent affinity for Ca2+ in vitro and in vivo [25, 47, 53, 54], and they both decrease proportionally with the increase in Mg2+ concentrations [33] (Fig. 5). As a result, under physiologically relevant free intracellular Mg2+ (~1 mM; [34]), GCAP1 can more and GCAP2 less readily exchange bound Ca2+ for Mg2+ in response to small decrease in free Ca2+ concentrations (Fig. 5). The difference in metal sensitivity between the two sensor proteins creates a possibility of the cyclase regulation being a sequential process where each of the two GCAPs is responsible for a different stage of boosting the cGMP synthesis during photoresponse [27, 53, 54] (Fig. 6a): GCAP1 would turn into a RetGC activator earlier in the course of photoresponse, as soon as the free Ca2+ concentrations start to fall after rod CNG channel closure, while GCAP2 would require deeper fall in free Ca2+ levels in order to bind Mg2+, which may occur at later stage of the photoresponse and/or at brighter illumination levels. This hypothesis was recently directly addressed in vivo using disruption of the GCAP2 gene in mouse [54]. The Ca2+-sensitive RetGC activity measured in rods lacking GCAP2 was reduced, and its Ca2+-sensitivity was shifted toward higher than normal range of Ca2+ concentrations, and both response kinetics and light sensitivity observed in those rods in single-cell recordings were generally consistent with the predictions from the model. GCAP2−/− rods displayed slowed recovery kinetics, increased light sensitivity, and faster saturation by background light, but the GCAP2 knockout did not substantially affect the amplitude of a single-photon response, which is all what one would expect if GCAP2 only contributed to RetGC activation at lower Ca2+ concentrations developed later in the excitation phase (Fig. 6). When the entire tail-to-tail pair of genes coding for GCAP1 and 2 [55] is disrupted with a single (GCAP1?GCAP2) knockout construct, there is drastic increase in the rod single-photon response amplitude [4, 27]. Virtually no increase of the amplitude was observed in the individual GCAP2 knockout rods, despite a delay in their recovery phase [50], therefore, it is reasonable to expect that it is a function of GCAP1 rather than GCAP2 to restrain the single-photon response amplitude by accelerating cGMP production earlier in the course of the response. In order to verify this suggestion, it would require testing a genetic model lacking individual GCAP1.

Fig. 5.

Ca2+ and Mg2+ sensitivity of RetGC regulation by GCAP1 and GCAP2 in rod outer segment (ROS) membranes (reproduced from [33]). a, b ROS membranes were depleted from the endogenous GCAPs by multiple hypotonic extractions, reconstituted with recombinant GCAP1 (a) or GCAP2 (b), and total RetGC activity in ROS was assayed as a function of free Ca2+ in the presence of 0.5 mM (open square), 1 mM (filled triangle), 2 mM (filled circle), and 5 mM (inverted filled triangle) free Mg2+; basal RetGC activity is shown at 0.5, 1, 2, and 5 mM Mg2+ (filled square, filled diamond, open circle, and open diamond, respectively) in the ROS membranes without GCAPs added. c The [Ca]1/2 values for RetGC inhibition by GCAP1 and GCAP2 increase proportionally with the free Mg2+ concentration, but their relative difference remains unchanged

Fig. 6.

Two-step activation model of retGC by GCAP1 and GCAP2 (reproduced from [54]). a Neither GCAP1 nor GCAP2 activate retGC in the dark when the Ca2+ concentration in rods is high. After illumination, as soon as Ca2+ starts to fall, GCAP1, which has the lower affinity for Ca2+ of the two GCAPs, converts into a Mg2+-bound state and activates retGC. This activation alone is not fully sufficient to achieve the normal, physiological kinetics of photoresponse recovery and light adaptation. Any fall in Ca2+ below 100 nM stimulates Ca2+/Mg2+ exchange to occur in GCAP2, which then provides additional activation of retGC. At present, it remains unclear whether or not each GCAP acts through a particular retGC isozyme or whether both GCAPs can directly or via an allosteric mechanisms compete for the same isozyme(s). b Slowed recovery of the GCAP2−/− single-photon response. The mean, fractional single-photon response from the knockout rods (gray trace) was similar in size to that from the wild-type rods (black trace), but the recovery was slower. The divergence of the two traces late in the rising phase suggests that GCAP2 normally activates retGC at this time. See [54], for the details

Conclusion

GCAPs have long been regarded as merely Ca2+ binding proteins, but evidence accumulated during recent years demonstrate that GCAPs are Ca2+/Mg2+ binding proteins, whose physiological function is controlled by the exchange of their bound Ca2+ for Mg2+ in the light versus dark, rather than merely release and binding of Ca2+. Both Ca2+-and Mg2+-bound states of GCAPs have distinct conformational and functional features and both are required for normal regulation of retinal guanylyl cyclase in photoreceptors upon changes between light and dark.

Acknowledgment

This work was supported in part by EY11522 grant from NIH. A.M. Dizhoor is the Martin and Florence Hafter Chair Professor of Pharmacology.

References

- 1.Pugh EN, Jr, Duda T, Sitaramayya A, Sharma RK. Photoreceptor guanylate cyclases: a review. Biosci Rep. 1997;17:429–473. doi: 10.1023/a:1027365520442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Pugh EN, Jr, Nikonov S, Lamb TD. Molecular mechanisms of vertebrate photoreceptor light adaptation. Curr Opin Neurobiol. 1999;9:410–418. doi: 10.1016/S0959-4388(99)80062-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Nakatani K, Chen C, Yau KW, Koutalos Y. Calcium and phototransduction. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2002;514:1–20. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4615-0121-3_1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Burns ME, Mendez A, Chen J, Baylor DA. Dynamics of cyclic GMP synthesis in retinal rods. Neuron. 2002;36:81–91. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(02)00911-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hodgkin AL, Nunn BJ. Control of light-sensitive current in salamander rods. J Physiol. 1988;403:439–471. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1988.sp017258. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Koch KW, Stryer L. Highly cooperative feedback control of retinal rod guanylate cyclase by calcium ions. Nature. 1988;334:64–66. doi: 10.1038/334064a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Koutalos Y, Nakatani K, Tamura T, Yau KW. Characterization of guanylate cyclase activity in single retinal rod outer segments. J Gen Physiol. 1995;106:863–890. doi: 10.1085/jgp.106.5.863. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dizhoor AM, Lowe DG, Olshevskaya EV, Laura RP, Hurley JB. The human photoreceptor membrane guanylyl cyclase, RetGC, is present in outer segments and is regulated by calcium and a soluble activator. Neuron. 1994;12:1345–1352. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(94)90449-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lowe DG, Dizhoor AM, Liu K, Gu Q, Spencer M, Laura R, Lu L, Hurley JB. Cloning and expression of a second photoreceptor-specific membrane retina guanylyl cyclase (RetGC), RetGC-2. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1995;92:5535–5539. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.12.5535. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Yang RB, Foster DC, Garbers DL, Fulle HJ. Two membrane forms of guanylyl cyclase found in the eye. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1995;92:602–606. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.2.602. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Garbers DL. The guanylyl cyclase receptors. Methods. 1999;19:477–484. doi: 10.1006/meth.1999.0890. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sharma RK. Evolution of the membrane guanylate cyclase transduction system. Mol Cell Biochem. 2002;230:3–30. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Laura RP, Dizhoor AM, Hurley JB. The membrane guanylyl cyclase, retinal guanylyl cyclase-1, is activated through its intracellular domain. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:11646–11651. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.20.11646. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Laura RP, Hurley JB. The kinase homology domain of retinal guanylyl cyclases 1 and 2 specifies the affinity and cooperativity of interaction with guanylyl cyclase activating protein-2. Biochemistry. 1998;37:11264–11271. doi: 10.1021/bi9809674. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Duda T, Fik-Rymarkiewicz E, Venkataraman V, Krishnan R, Koch KW, Sharma RK. The calcium-sensor guanylate cyclase activating protein type 2 specific site in rod outer segment membrane guanylate cyclase type 1. Biochemistry. 2005;44:7336–7345. doi: 10.1021/bi050068x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gorczyca WA, Van Hooser JP, Palczewski K. Nucleotide inhibitors and activators of retinal guanylyl cyclase. Biochemistry. 1994;33:3217–3222. doi: 10.1021/bi00177a011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dizhoor AM, Olshevskaya EV, Henzel WJ, Wong SC, Stults JT, Ankoudinova I, Hurley JB. Cloning, sequencing, and expression of a 24-kDa Ca(2+)-binding protein activating photoreceptor guanylyl cyclase. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:25200–25206. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.42.25200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gorczyca WA, Polans AS, Surgucheva IG, Subbaraya I, Baehr W, Palczewski K. Guanylyl cyclase activating protein. A calcium-sensitive regulator of phototransduction. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:22029–22036. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.37.22029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Haeseleer F, Sokal I, Li N, Pettenati M, Rao N, Bronson D, Wechter R, Baehr W, Palczewski K. Molecular characterization of a third member of the guanylyl cyclase-activating protein subfamily. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:6526–6535. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.10.6526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gray-Keller MP, Detwiler PB. The calcium feedback signal in the phototransduction cascade of vertebrate rods. Neuron. 1994;13:849–861. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(94)90251-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sampath AP, Matthews HR, Cornwall MC, Bandarchi J, Fain GL. Light-dependent changes in outer segment free-Ca2+ concentration in salamander cone photoreceptors. J Gen Physiol. 1999;113:267–277. doi: 10.1085/jgp.113.2.267. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Woodruff ML, Sampath AP, Matthews HR, Krasnoperova NV, Lem J, Fain GL. Measurement of cytoplasmic calcium concentration in the rods of wild-type and transducin knock-out mice. J Physiol. 2002;542:843–854. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2001.013987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Woodruff ML, Wang Z, Chung HY, Redmond TM, Fain GL, Lem J. Spontaneous activity of opsin apoprotein is a cause of Leber congenital amaurosis. Nat Genet. 2003;35:158–164. doi: 10.1038/ng1246. [Epub 2003 Sep 2021] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Dizhoor AM, Hurley JB. Inactivation of EF-hands makes GCAP-2 (p24) a constitutive activator of photoreceptor guanylyl cyclase by preventing a Ca2+-induced “activator-to-inhibitor” transition. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:19346–19350. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.32.19346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Dizhoor AM, Boikov SG, Olshevskaya EV. Constitutive activation of photoreceptor guanylate cyclase by Y99C mutant of GCAP-1. Possible role in causing human autosomal dominant cone degeneration. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:17311–17314. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.28.17311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Peshenko IV, Dizhoor AM. Activation and inhibition of photoreceptor guanylyl cyclase by guanylyl cyclase activating protein 1 (GCAP-1): the functional role of Mg2+/Ca2+ exchange in EF-hand domains. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:21645–21652. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M702368200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mendez A, Burns ME, Sokal I, Dizhoor AM, Baehr W, Palczewski K, Baylor DA, Chen J. Role of guanylate cyclase-activating proteins (GCAPs) in setting the flash sensitivity of rod photoreceptors. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2001;98:9948–9953. doi: 10.1073/pnas.171308998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Palczewski K, Subbaraya I, Gorczyca WA, Helekar BS, Ruiz CC, Ohguro H, Huang J, Zhao X, Crabb JW, Johnson RS, Walsh KA, Gray-Keller MP, Detwiller PB, Baehr W. Molecular cloning and characterization of retinal photoreceptor guanylyl cyclase-activating protein. Neuron. 1994;13:395–404. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(94)90355-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Imanishi Y, Yang L, Sokal I, Filipek S, Palczewski K, Baehr W. Diversity of guanylate cyclase-activating proteins (GCAPs) in teleost fish: characterization of three novel GCAPs (GCAP4, GCAP5, GCAP7) from zebrafish (Danio rerio) and prediction of eight GCAPs (GCAP1–8) in pufferfish (Fugu rubripes) J Mol Evol. 2004;59:204–217. doi: 10.1007/s00239-004-2614-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Peshenko IV, Dizhoor AM. Ca2+ and Mg2+ binding properties of GCAP-1. Evidence that Mg2+-bound form is the physiological activator of photoreceptor guanylyl cyclase. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:23830–23841. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M600257200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Rudnicka-Nawrot M, Surgucheva I, Hulmes JD, Haeseleer F, Sokal I, Crabb JW, Baehr W, Palczewski K. Changes in biological activity and folding of guanylate cyclase-activating protein 1 as a function of calcium. Biochemistry. 1998;37:248–257. doi: 10.1021/bi972306x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lim S, Peshenko I, Dizhoor A, Ames JB. Effects of Ca2+, Mg2+, and myristoylation on guanylyl cyclase activating protein 1 structure and stability. Biochemistry. 2009;48:850–862. doi: 10.1021/bi801897p. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Peshenko IV, Dizhoor AM. Guanylyl cyclase-activating proteins (GCAPs) are Ca2+/Mg2+ sensors: implications for photoreceptor guanylyl cyclase (RetGC) regulation in mammalian photoreceptors. J. Biol. Chem. 2004;279:16903–16906. doi: 10.1074/jbc.C400065200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Chen C, Nakatani K, Koutalos Y. Free magnesium concentration in salamander photoreceptor outer segments. J Physiol. 2003;553:125–135. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2003.053280. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Peshenko IV, Olshevskaya EV, Dizhoor AM. Binding of guanylyl cyclase activating protein 1 (GCAP1) to retinal guanylyl cyclase (RetGC1). The role of individual EF-hands. J Biol Chem. 2008;283:21747–21757. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M801899200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sokal I, Li N, Klug CS, Filipek S, Hubbell WL, Baehr W, Palczewski K. Calcium-sensitive regions of GCAP1 as observed by chemical modifications, fluorescence, and EPR spectroscopies. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:43361–43373. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M103614200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sokal I, Otto-Bruc AE, Surgucheva I, Verlinde CL, Wang CK, Baehr W, Palczewski K. Conformational changes in guanylyl cyclase-activating protein 1 (GCAP1) and its tryptophan mutants as a function of calcium concentration. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:19829–19837. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.28.19829. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ermilov AN, Olshevskaya EV, Dizhoor AM. Instead of binding calcium, one of the EF-hand structures in guanylyl cyclase activating protein-2 is required for targeting photoreceptor guanylyl cyclase. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:48143–48148. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M107539200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hwang JY, Schlesinger R, Koch KW. Irregular dimerization of guanylate cyclase-activating protein 1 mutants causes loss of target activation. Eur J Biochem. 2004;271:3785–3793. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.2004.04320.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ames JB, Dizhoor AM, Ikura M, Palczewski K, Stryer L. Three-dimensional structure of guanylyl cyclase activating protein-2, a calcium-sensitive modulator of photoreceptor guanylyl cyclases. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:19329–19337. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.27.19329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Stephen R, Bereta G, Golczak M, Palczewski K, Sousa MC. Stabilizing function for myristoyl group revealed by the crystal structure of a neuronal calcium sensor, guanylate cyclase-activating protein 1. Structure. 2007;15:1392–1402. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2007.09.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Stephen R, Filipek S, Palczewski K, Sousa MC. Ca2+-dependent regulation of phototransduction. Photochem Photobiol. 2008;84:903–910. doi: 10.1111/j.1751-1097.2008.00323.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Stephen R, Palczewski K, Sousa MC. The crystal structure of GCAP3 suggests molecular mechanism of GCAP-linked cone dystrophies. J Mol Biol. 2006;359:266–275. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2006.03.042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Payne AM, Downes SM, Bessant DA, Taylor R, Holder GE, Warren MJ, Bird AC, Bhattacharya SS. A mutation in guanylate cyclase activator 1A (GUCA1A) in an autosomal dominant cone dystrophy pedigree mapping to a new locus on chromosome 6p21.1. Hum Mol Genet. 1998;7:273–277. doi: 10.1093/hmg/7.2.273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Wilkie SE, Li Y, Deery EC, Newbold RJ, Garibaldi D, Bateman JB, Zhang H, Lin W, Zack DJ, Bhattacharya SS, Warren MJ, Hunt DM, Zhang K. Identification and functional consequences of a new mutation (E155G) in the gene for GCAP1 that causes autosomal dominant cone dystrophy. Am J Hum Genet. 2001;69:471–480. doi: 10.1086/323265. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Sokal I, Li N, Surgucheva I, Warren MJ, Payne AM, Bhattacharya SS, Baehr W, Palczewski K. GCAP1 (Y99C) mutant is constitutively active in autosomal dominant cone dystrophy. Mol Cell. 1998;2:129–133. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(00)80121-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Olshevskaya EV, Calvert PD, Woodruff ML, Peshenko IV, Savchenko AB, Makino CL, Ho YS, Fain GL, Dizhoor AM. The Y99C mutation in guanylyl cyclase-activating protein 1 increases intracellular Ca2+ and causes photoreceptor degeneration in transgenic mice. J Neurosci. 2004;24:6078–6085. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0963-04.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Woodruff ML, Olshevskaya EV, Savchenko AB, Peshenko IV, Barrett R, Bush RA, Sieving PA, Fain GL, Dizhoor AM. Constitutive excitation by Gly90Asp rhodopsin rescues rods from degeneration caused by elevated production of cGMP in the dark. J Neurosci. 2007;27:8805–8815. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2751-07.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Duda T, Goraczniak R, Surgucheva I, Rudnicka-Nawrot M, Gorczyca WA, Palczewski K, Sitaramayya A, Baehr W, Sharma RK. Calcium modulation of bovine photoreceptor guanylate cyclase. Biochemistry. 1996;35:8478–8482. doi: 10.1021/bi960752z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Yang RB, Robinson SW, Xiong WH, Yau KW, Birch DG, Garbers DL. Disruption of a retinal guanylyl cyclase gene leads to cone-specific dystrophy and paradoxical rod behavior. J Neurosci. 1999;19:5889–5897. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.19-14-05889.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Hwang JY, Lange C, Helten A, Hoppner-Heitmann D, Duda T, Sharma RK, Koch KW. Regulatory modes of rod outer segment membrane guanylate cyclase differ in catalytic efficiency and Ca2+-sensitivity. Eur J Biochem. 2003;270:3814–3821. doi: 10.1046/j.1432-1033.2003.03770.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Baehr W, Karan S, Maeda T, Luo DG, Li S, Bronson JD, Watt CB, Yau KW, Frederick JM, Palczewski K. The function of guanylate cyclase 1 and guanylate cyclase 2 in rod and cone photoreceptors. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:8837–8847. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M610369200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Hwang JY, Koch KW. Calcium- and myristoyl-dependent properties of guanylate cyclase-activating protein-1 and protein-2. Biochemistry. 2002;41:13021–13028. doi: 10.1021/bi026618y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Makino CL, Peshenko IV, Wen XH, Olshevskaya EV, Barrett R, Dizhoor AM. A role for GCAP2 in regulating the photoresponse. Guanylyl cyclase activation and rod electrophysiology in GUCA1B knock-out mice. J Biol Chem. 2008;283:29135–29143. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M804445200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Howes K, Bronson JD, Dang YL, Li N, Zhang K, Ruiz C, Helekar B, Lee M, Subbaraya I, Kolb H, Chen J, Baehr W. Gene array and expression of mouse retina guanylate cyclase activating proteins 1 and 2. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 1998;39:867–875. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]