Abstract

Objectives

We sought to examine the relationship between depressive symptoms and subjective memory problems. We hypothesized that the relationship between depressive symptoms and poor subjective memory functioning is mediated by negative cognitive bias that is associated with hopelessness, a wish to die and low self-esteem.

Methods

Complete data were available for 299 older adults with and without significant depressive symptoms who were screened in primary care offices and invited to participate, completed a baseline in-home assessment. Subjective memory functioning and psychological status was assessed with commonly used, validated standard questionnaires.

Results

In regression models that included terms for age, gender and cognitive measures, depressive symptoms were significantly inversely associated with the global self-assessment of memory (β = −0.019; p = 0.006). When components of negative cognitive bias were included in the model (hopelessness, low self-esteem, a wish to die), the relationship of depressive symptoms with subjective memory problems was attenuated, consistent with mediation.

Conclusions

Our results suggest that assessment and successful interventions for memory complaints in non-demented older adults need to account for negative cognitive bias as well as depressive symptoms. Longitudinal research is needed to confirm our findings before a mediator relationship can be presumed.

Introduction

Subjective memory disturbances or complaints are common in older adults (Larrabee & Crook, 1994). Frequently older adults present to the primary care setting with a chief complaint of memory problems, which may show little relation to objective memory performance. Older adults with intact memory who self-report memory problems often have higher rates of depression (Turvey, Schultz, Arndt, Wallace, & Herzog, 2000). Subjective memory complaints may be the presentation of depression or may co-exist with depressive symptoms (Small et al., 2001) more often than with true cognitive decline (Derouesne et al., 1999; Jungwirth et al., 2004; Pearman & Storandt, 2004). However, the processes underlying the relationship between reports of memory loss and depressive symptoms are poorly understood.

Previous research has found depressive symptoms to be associated with self-perceived memory loss (La Rue et al., 1996), hopelessness (Alford, Lester, Patel, Buchanan, & Giunta, 1995; Beevers & Miller, 2004), death thoughts (Draper, MacCuspie-Moore, & Brodaty, 1998; Forsell, Jorm, & Winblad, 1997; Jorm et al., 1995; Scocco, Meneghel, Caon, Dello Buono, & De Leo, 2001) and low self-esteem (Andrews & Brown, 1995; Brown, Andrews, Harris, Adler, & Bridge, 1986; Brown, Bifulco, & Andrews, 1990a; Brown, Bifulco, Veiel, & Andrews, 1990b). Beck's theory of depression described depressed persons as having distorted negative perceptions of themselves, their world and their future (Beck, Rush, Shaw, & Emery, 1979; Blackburn & Eunson, 1989). Specifically, depressed individuals often have distorted cognitions that include hopelessness (Beck, Weissman, Lester, & Trexler, 1974), low self-esteem (Brown et al., 1990a; 1990b) and a wish to die or suicidal ideation (Beck, Steer, & Brown, 1993; Beevers & Miller, 2004). Blackburn and Eunson (1989) reported that a negative view of self and a negative view of the world are valid indicators of depression. Because older adults complaining of memory problems may not present with depression in a stereotypical fashion (e.g. symptoms that do not meet the standard criteria for major depression), understanding the role of negative cognitive bias may help elucidate the relationship between reports of memory loss and depressive symptoms.

The association between depressive symptoms and subjective memory has been well established (Jungwirth et al., 2004; La Rue et al., 1996; Pearman & Storandt, 2004; Wang et al., 2004). Components of negative cognitive bias such as hopelessness and low self-esteem and have also been linked to subjective memory (Comijs, Deeg, Dik, Twisk, & Jonker, 2002; McDougall, 2004). Turvey et al. (2000) proposed that memory complaints could result from the negative cognitive style or even a pathophysiologic process unique to depression that impairs an individual's ability to self-assess memory function. The study of potentially important mediators between reports of memory loss and depressive symptoms can pave the way to a better understanding of how depressive symptoms relates to subjective memory and what might be done for older primary care patients presenting with reports of memory loss. The intermediate processes in the relationship between reports of memory loss and depressive symptoms have yet to be empirically tested.

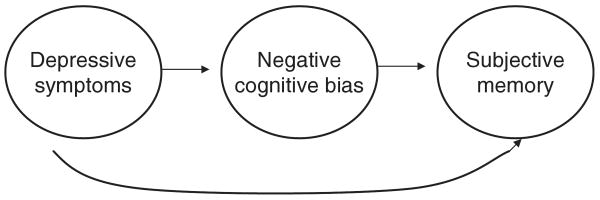

We hypothesized that the association of depressive symptoms with subjective memory problems may be mediated through the association of depressive symptoms with negative cognitive bias. A characteristic is a mediator if it accounts for the variation between a predictor and an outcome. While moderators indicate when effects might be seen, mediators specify how or why (Baron & Kenny, 1986). The conceptual model in Figure 1 represents a set of testable hypotheses about how the constructs representing reports of memory loss and depressive symptoms may be related to one another through their association with negative cognitive bias. Our conceptual model is tested in three stages as: (1) the association between depressive symptoms and negative cognitive bias components (hopelessness, wish to die, self-esteem); (2) the association between subjective memory and depressive symptoms and separately between subjective memory and negative cognitive bias; and (3) the association between subjective memory with depressive symptoms with terms representing negative cognitive bias in the model. Although longitudinal research is needed to confirm a mediator relationship, if negative cognitive bias attenuates the association between depressive symptoms and subjective memory this would be evidence for mediation.

Figure 1.

Conceptual model of the potential relationship of depressive symptoms, the negative cognitive bias and subjective memory.

Our investigation differs from other studies examining the association of depressive symptoms and subjective memory problems in several ways. Our study sample consisted of non-demented community-dwelling older adults. In addition, our conceptual model incorporates negative cognitive components into the constructs of depressive symptoms and subjective memory. Previously published research has not attempted to test the multiple relationships among depressive symptoms, cognitive bias and subjective memory. Our study allows for examination of interrelationships to better understand the contribution each predictor makes to subjective memory.

Methods

Participants

The objective of the Spectrum Survey was to describe depressive symptoms in older adults that do not meet standard criteria. Primary care practices recruited from the community provided the venue for sampling older patients. Trained lay interviewers were instructed in screening and study interviews by the study investigators working with Battelle Memorial Institute's Center for Public Health Research and Evaluation, Baltimore, Maryland. Specifically, we invited the screened patients with the following sampling probabilities: (1) 100% who scored above a threshold of 17 or above on the Centers for Epidemiologic Studies Depression (CES-D) scale (described below); (2) 50% who scored below threshold but were currently taking medications for sleep, pain or an emotional problem; and (3) 10% who scored below threshold and were not currently taking medications for sleep, pain or an emotional problem. The rationale for the different sampling probabilities was to develop a sample of older adults that was enriched with patients with depressive symptoms and with patients who may not currently be depressed but who may nonetheless be at risk for depression or whose depression may be in remission. Participants who agreed to be part of the study were scheduled for an in-home interview, which consisted of a 90-minute survey questionnaire. In-home interviews were obtained for 357 people, but two persons broke off the interview before it was completed, leaving a sample of 355 persons. Details of the study design of the Spectrum Study are available elsewhere (Bogner et al., 2005; Gallo, Bogner, Morales, & Ford, 2005). The study protocols were approved by the Institutional Review Board of the University of Pennsylvania School of Medicine.

Measurement strategy

We used standard questions to obtain information from the respondents on age, gender, marital status, self-reported ethnicity and education.

Functional status

The Medical Outcomes Study Short Form (SF-36) has been employed in studies of outcomes of patient care (Gallo et al., 2005; McHorney, 1996; Stewart & Ware, 1993; Stewart, Hays, & Ware, 1988; Stewart et al., 1989) and appears to be reliable and valid even in frail elders (Stadnykm, Calder, & Rockwood, 1998). We employed the scales representing physical functioning, role disability due to physical health problems, bodily pain, general health perceptions, social functioning and role disability due to emotional problems. The scale for each dimension ranges from 0–100, with higher numbers representing better health.

Cognitive status

The Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE) is a brief global measure of cognition that has been employed for clinical and research purposes (Crum, Anthony, Bassett, & Folstein, 1993; Folstein, Folstein, & McHugh, 1975; Tombaugh & McIntyre, 1992). The Controlled Oral Word Association Test (FAS) serves as a test of verbal production and access to semantic knowledge and language (Benton & Hamsher, 1983). The respondent is asked to generate as many words as possible that begin with a certain letter (F, A and S) in one minute. The score is the sum of all words produced in the three one-minute trials. The Hopkins Verbal Learning Task (HVLT) evaluates new verbal learning and memory. On each of three trials participants listened to an audio-taped list of 12 words (four from each of three different semantic categories), read at 2-second intervals and were asked to recall as many words as possible (Brandt, 1991). Scores were recorded as the total number of words correctly recalled over three learning trials and analyzed as a continuous variable (Hogervorst et al., 2002). The Controlled Oral Word Association Test and HVLT improve assessment of tasks not well mapped by the MMSE alone (namely, executive function and memory).

Psychological status

Depressive symptoms were measured with the CES-D scale, developed by the Center for Epidemiologic Studies at the National Institute of Mental Health for use in studies of depression in community samples (Comstock & Helsing, 1976; Eaton & Kessler, 1981; Radloff, 1977) and has been employed in studies of older adults (Gatz, Johansson, Pedersen, Berg, & Reynolds, 1993; Newmann, Engel, & Jensen, 1991). The CES-D contains 20-items. The Beck Hopelessness Scale (BHS) consists of 20 true-false statements that are rated by the respondent and is designed to assess the extent of positive and negative beliefs about the future. Evidence for the construct validity of the BHS comes from studies that relate scores on the BHS to depression (Nekanda-Trepka, Bishop, & Blackburn, 1983; Prezant & Neimeyer, 1988). The wish to die or death ideation was based on positive responses to two questions from the Composite International Diagnostic Interview (CIDI) Depression Section (Comstock & Helsing, 1976): ‘did you think a lot about death?’ and ‘did you feel like you wanted to die?’ The CIDI is a lay-administered interview for the assessment of mental disturbances according to the International Classification of Diseases (ICD) and the American Psychiatric Association's Diagnostic and Statistical Manual. The negative evaluation of self (worthlessness or low self-esteem) was measured by two yes/no questions: ‘did you feel that you were not as good as other people’ and ‘did you have so little self-confidence that you wouldn't try to have your say about anything?’ The questions are from the CIDI Depression section (Comstock & Helsing, 1976).

Subjective memory

Self-rating of memory performance was assessed with ten questions from the Memory Functioning Questionnaire (MFQ), a widely used instrument developed to evaluate self-perception of everyday memory functioning (Gilewski & Zelinski, 1988; Gilewski, Zelinski, & Schaie, 1990). For this study we used an abbreviated version of the MFQ for the general memory scale and the frequency of forgetting scale, both of which were previously validated and used for the Advanced Cognitive Training for Independent and Vital Elderly (ACTIVE) Study (Gallo et al., 2003; Jobe et al., 2001). Participants were asked to rate their general memory performance: ‘how would you rate your memory in terms of the kinds of problems that you have?’ Participants rated their memory on a 7-point scale (ranging from 1 = major problems to 7 = no problems).

Analytic strategy

Of the 355 patients in the study sample, analyses were restricted to participants who had complete data on all the variables under study (n = 299). Descriptive statistics (means with standard deviations and proportions) were used to characterize the patients' baseline characteristics. We determined that the data were Gaussian by visual inspection.

Data analysis proceeded in three phases with multiple regression as the primary analytic method, in which the covariates were entered as continuous variables (or dichotomous as necessary) without transformation. Consistent with the outline for testing mediation of Baron and Kenny (1986), stepped multiple regression analyses were carried out in three stages: (1) regression of depressive symptoms on the negative cognitive bias; (2) regression of the subjective memory problems on depressive symptoms and the negative cognitive bias separately; and (3) regression of subjective memory on depressive symptoms with terms representing the negative cognitive bias in the model. If any significant association of depressive symptoms and subjective memory problems becomes attenuated or null with terms representing the negative cognitive bias in the model, this would be preliminary evidence for mediation. All multivariate models were adjusted for age, gender, ethnicity, education, function and cognitive status. Data analysis was performed using SPSS version 12 (SPSS Corporations, College Station, Texas).

Results

Sociodemographics and clinical characteristics

In Table I we report the sociodemographics and clinical characteristics of the sample of 299 persons for whom complete data were available. There were no statistically significant differences in the means or proportions between the group used for analysis and the entire study sample of 355. Continuous variables were normally distributed.

Table I.

Characteristics of 299 participants with complete data.

| Patient characteristics Demographics | Mean (SD) or number (%) |

|---|---|

| Age in years, mean (SD) | 75.3 (6.1) |

| Women, n (%) | 228 (76) |

| White n (%) | 201 (67) |

| Education in years, mean (SD) | 120 (40) |

| Subjective memory | |

| Self rated memory (global) (SD) | 4.2 (1.4) |

| Psychological variables | |

| CES-D-R, mean (SD) | 14.2 (11.1) |

| Beck Hopelessness Scale, mean (SD) | 4.8 (4.3) |

| Wish to die, n (%) | 39 (13) |

| Negative evaluation of self (self-esteem), n (%) | 50 (17) |

| Cognition | |

| MMSE, mean (SD) | 27.2 (2.5) |

| FAS, mean (SD) | 27.3 (13.9) |

| HVLT, mean (SD) | 18.3 (5.8) |

| Functional status | |

| Physical functioning, mean (SD) | 59.8 (29.3) |

SD = standard deviation; CES-D = Center for Epidemiological Studies Depression Scale; MMSE = Mini-Mental State Examination; FAS = Controlled Oral Word Association Test; HVLT = Hopkins Verbal Learning Test.

Depressive symptoms and negative cognitive bias

The regression coefficients of depressive symptoms as measured by the CES-D on negative cognitive bias variables are presented in Table II. Depressive symptoms were statistically significantly associated with the components of hopelessness and self-esteem in the adjusted and unadjusted models. Depressive symptoms were not significantly related to the wish to die in the unadjusted model, however this relationship was significant in the regression models that included terms for age, gender, self-reported ethnicity, education, function, and cognitive status.

Table II.

Regression of depressive symptoms as measured by the CES-D on potentially mediating variables.

| Unadjusted model 1 | Adjusted model 2 | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| β | p-value | β | p-value | |

| Negative cognitive bias | ||||

| Beck Hopelessness Scale | −0.087 | <0.001 | 0.25 | <0.001 |

| Wish to die | −0.807 | 0.001 | 0.11 | 0.04 |

| Low self-esteem | −0.23 | 0.100 | 0.22 | <0.001 |

Model 1 is unadjusted.

Model 2 is adjusted for age, gender, self-reported ethnicity, function and cognitive variables (MMSE, FAS, HVLT).

CES-D = Center for Epidemiological Studies Depression Scale; MMSE = Mini-mental State Examination; FAS = Controlled Oral Word Association Test; HVLT = Hopkins Verbal Learning Test.

Depressive symptoms and subjective memory

The regression coefficients of subjective memory on depressive symptoms as well as for negative bias components are presented in Table III. In the unadjusted model, depressive symptoms were significantly related to subjective memory. The individual components of hopelessness, self-esteem, and the wish to die were related to subjective memory in both the unadjusted and adjusted models.

Table III.

Regression of metamemory as measured by the self-report of memory problems on potentially mediating variables.

| Unadjusted model 1 | Adjusted model 2 | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| β | p-value | β | p-value | |

| CES-D | −0.019 | 0.006 | −0.02 | 0.81 |

| Negative cognitive bias | ||||

| Beck Hopelessness Scale | −0.087 | <0.001 | −0.18 | 0.01 |

| Wish to die | −0.807 | 0.001 | −0.07 | 0.24 |

| Low self-esteem | −0.23 | <0.001 | −0.13 | 0.03 |

Model 1 is unadjusted.

Model 2 is adjusted for negative cognitive bias (Beck Hopelessness Scale, the wish to die and low self-esteem) in addition to the demographic, function, and cognitive variables (MMSE, FAS, HVLT).

CES-D = Center for Epidemiological Studies Depression Scale = MMSE: Mini-mental State Examination; FAS = Controlled Oral Word Association Test; HVLT = Hopkins Verbal Learning Test.

Depressive symptoms, negative cognitive bias, and subjective memory

We introduced the terms for depressive symptoms, negative cognitive bias (hopelessness, self-esteem, the wish to die) sequentially with subjective memory as the dependent variable. The association of depressive symptoms with subjective memory diminished to the null value with negative cognitive bias components in the model (first row of Table III).

Discussion

The purpose of this study was to examine the extent to which the relationship of depressive symptoms to subjective memory problems might be mediated by negative cognitive bias components such as hopelessness, self-esteem and a wish to die in primary care older adults. We hypothesized that negative cognitive bias components of hopelessness, a wish to die and low self-esteem would account for the relationship between depressive symptoms and subjective memory problems. We found that depressive symptoms were independently associated with the negative cognitive bias components as well as with subjective memory. However, we found evidence for mediation in that the association of depressive symptoms with subjective memory was accounted for by the relationship of the negative cognitive bias variables with depressive symptoms. The findings require confirmation in other samples and with a longitudinal design to clarify the directionality of the relationship postulated in the conceptual model. Nevertheless, we have been able to link reports of memory loss and depressive symptoms through the association of depressive symptoms with negative cognitive bias.

Before discussing our findings, the results must be considered in the context of some potential study limitations. First, we obtained our results only from primary care sites in Maryland whose patients may not be representative of most primary care practices. These practices were not academically affiliated and are probably similar to other primary care practices in the country. Second, we must be careful in our conclusions since the results are based on cross-sectional analyses (Kraemer, Wilson, Fairburn, & Agras, 2002). For that reason, we cannot be sure the extent to which our measures of association of depressive symptoms to the negative cognitive bias components or subjective memory occurred because persons with a negative cognitive bias or subjective memory complaints are more likely to express depressive symptoms. However, we were able to relate depressive symptoms and subjective memory through the association of depressive symptoms with negative cognitive bias. Finally, we realize that even standardized measures are fallible and may tap constructs that were not intended by the developers or implied by the labels given them. Depressive symptoms as assessed by the CES-D do not correspond to diagnostic criteria for major depression (American Psychiatric Association, 1994). However, we would argue that depressive symptoms are appropriate as a focus of our investigation of older adults for reasons we have discussed elsewhere (Gallo & Lebowitz, 1999).

Despite limitations, our study warrants attention because we attempted to further address the relationship between depressive symptoms, negative cognitive bias and subjective memory while adjusting our estimates of association for demographic factors, function and cognition. Because we examined a community-based primary care sample, the results may be generalizable to older adults in primary care settings, which may help facilitate assessment and consequent interventions.

Depression and negative cognitive bias

Consistent with previous research, depressive symptoms and negative cognitive bias were strongly correlated in older adults (Alford et al., 1995; Andrews & Brown, 1995; Beevers & Miller, 2004; Draper et al., 1998; Forsell et al., 1997; Jorm et al., 1995; Jungwirth et al., 2004; La Rue et al., 1996; Pearman & Storandt, 2004; Scocco et al., 2001). Extensive research has found strong associations between depressive symptoms and hopelessness (Alford et al., 1995; Beevers & Miller, 2004), death thoughts (Draper et al., 1998; Forsell et al., 1997; Jorm et al., 1995; Scocco et al., 2001) and low self-esteem (Andrews & Brown, 1995; Brown et al., 1986; 1990; Brown, Bifulco, & Andrews, 1990) both individually and as part of Beck's negative cognitive triad. Hopelessness is intimately linked to late-life depressive symptoms (Adams, Matto, & Sanders, 2004). Theoretically, for depressed individuals, negative cognitions associated with hopelessness and low self-esteem may lead to thoughts of death or thoughts that life is not worth living and death ideation. This negative thinking style may then progress to suicidal ideation (Heisel & Flett, 2005; O'Connell, Chin, Cunningham, & Lawlor, 2004). Several studies have offered some preliminary support of our model. For example, death ideation (or a wish to die) in older adults has been strongly linked to major depression (Jorm et al., 1995). Wetzel and Reich (1989) found that both low self-esteem and hopelessness were correlated highly with suicidal ideation in depressed patients.

Associations with subjective memory

The association between depressive symptoms and subjective memory complaints has been widely reported (Beck et al., 1974; 1993; Blackburn & Eunson, 1989; Derouesne et al., 1999; Small et al., 2001; Turvey et al., 2000). A number of components influence subjective memory complaints. Researchers generally agree that memory complaints are more frequent in those who are depressed (Jorm et al., 1994; Jungwirth et al., 2004; O'Connor, Pollitt, Roth, Brook, & Reiss, 1990). Although there have been many studies that have investigated the association between depressive symptoms and subjective memory complaints, there is a paucity of studies that have evaluated the association between negative cognitive bias and subjective memory.

Negative cognitive bias as a mediator

Our findings support our hypothesis that negative cognitive bias mediates the relationship between depressive symptoms and subjective memory. We found that negative cognitive bias was most closely associated with memory complaints. Prior work is limited by the use of a model of depression that does not address maladaptive thinking that can lead to memory complaints (Baron & Kenny, 1986; Comijs et al., 2002; McDougall, 2004). There is limited research that has evaluated the construct of negative cognitive bias as a mediator between depressive symptoms and subjective memory.

Conclusion

Although our conclusions are confined by limitations, we believe the findings warrant attention in the study of how depressive symptoms are linked to memory complaints. Because memory complaints may be the presentation of depression or may co-exist with depressive symptoms, it is vital to understand the implications of subjective memory problems. If the mediation of the association of depressive symptoms with subjective memory by negative cognitive bias were confirmed by further studies, the findings suggest that negative cognitive bias components need to be considered in assessment and consequent interventions for older adults with memory complaints. Clinicians should consider evaluating negative cognitive bias including low self-esteem, hopelessness and the wish to die in older adults complaining of memory problems.

Acknowledgments

Dr. Crane was supported by HRSA, Bureau of Health Professions (Grant 1 DO1 HP 00019-01 0). The Spectrum Study was supported by grants MH62210-01, MH62210-01S1, and MH67077 from the National Institute of Mental Health. Dr. Bogner was supported by a NIMH Mentored Patient-Oriented Research Career Development Award (MH67671-01) and the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation Generalist Physician Faculty Scholars Program (2004–2008).

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: Copyright of Aging & Mental Health is the property of Routledge and its content may not be copied or emailed to multiple sites or posted to a listserv without the copyright holder's express written permission. However, users may print, download, or email articles for individual use.

Presented at the 18th NIMH Mental Health Services Research Meeting, Bethesda, MD, 19 July, 2005.

References

- Adams KB, Matto HC, Sanders S. Confirmatory factor analysis of the geriatric depression scale. Gerontologist. 2004;44:818–826. doi: 10.1093/geront/44.6.818. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alford BA, Lester JM, Patel RJ, Buchanan JP, Giunta LC. Hopelessness predicts future depressive symptoms: A prospective analysis of cognitive vulnerability and cognitive content specificity. Journal of Clinical Psychology. 1995;51:331–339. doi: 10.1002/1097-4679(199505)51:3<331::aid-jclp2270510303>3.0.co;2-t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- American Psychiatric Association, editor. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, DSM-IV. 4th. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Andrews B, Brown GW. Stability and change in low self-esteem: The role of psychosocial factors. Psychological Medicine. 1995;25:23–31. doi: 10.1017/s0033291700028051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baron RM, Kenny DA. The moderator-mediator variable distinction in social psychological research: Conceptual, strategic, and statistical considerations. Journal of Personal and Social Psychology. 1986;51:1173–1182. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.51.6.1173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beck AT, Rush AJ, Shaw BF, Emery G. Cognitive therapy of depression. New York: Guilford; 1979. [Google Scholar]

- Beck AT, Steer RA, Brown G. Dysfunctional attitudes and suicidal ideation in psychiatric outpatients. Suicide and Life-Threatening Behavior. 1993;23:11–20. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beck AT, Weissman A, Lester D, Trexler L. The measurement of pessimism: The hopelessness scale. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1974;42:861–865. doi: 10.1037/h0037562. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beevers CG, Miller IW. Perfectionism, cognitive bias and hopelessness as prospective predictors of suicidal ideation. Suicide and Life-Threatening Behavior. 2004;34:126–137. doi: 10.1521/suli.34.2.126.32791. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benton AL, Hamsher K. Multilingual aphasia examination. Iowa City, IA: AJA Associates; 1983. [Google Scholar]

- Blackburn IM, Eunson KM. A content analysis of thoughts and emotions elicited from depressed patients during cognitive therapy. British Journal of Medical Psychology. 1989;62(Part 1):23–33. doi: 10.1111/j.2044-8341.1989.tb02807.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bogner HR, Cary MS, Bruce ML, Reynolds CF, Mulsant B, Ten-Have T, et al. The role of medical comorbidity on outcomes of major depression in primary care: The PROSPECT Study. American Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry. 2005;13:861–868. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajgp.13.10.861. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brandt J. The hopkins verbal learning test: Development of a new memory test with six equivalent forms. Clinical Neuropsychologist. 1991;5:125–142. [Google Scholar]

- Brown GW, Bifulco A, Andrews B. Self-esteem and depression: III. Aetiological issues. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology. 1990;25:235–243. doi: 10.1007/BF00788644. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown GW, Bifulco A, Veiel HO, Andrews B. Self-esteem and depression. II. Social correlates of self-esteem. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology. 1990;25:225–234. doi: 10.1007/BF00788643. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown GW, Andrews B, Harris T, Adler Z, Bridge L. Social support, self-esteem and depression. Psychological Medicine. 1986;16:813–831. doi: 10.1017/s0033291700011831. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Comijs HC, Deeg DJ, Dik MG, Twisk JW, Jonker C. Memory complaints: The association with psycho-affective and health problems and the role of personality characteristics. A 6-year follow-up study. Journal of Affective Disorders. 2002;72:157–165. doi: 10.1016/s0165-0327(01)00453-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Comstock GW, Helsing KJ. Symptoms of depression in two communities. Psychological Medicine. 1976;6:551–563. doi: 10.1017/s0033291700018171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crum RM, Anthony JC, Bassett SS, Folstein MF. Population-based norms for the Mini-Mental State Examination by age and educational level. Journal of the American Medical Association. 1993;269:2386–2391. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Derouesne C, Thibault S, Lagha-Pierucci S, Baudouin-Madec V, Ancri D, Lacomblez L. Decreased awareness of cognitive deficits in patients with mild dementia of the Alzheimer type. International Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry. 1999;14:1019–1030. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Draper B, MacCuspie-Moore C, Brodaty H. Suicidal ideation and the ‘wish to die’ in dementia patients: The role of depression. Age and Ageing. 1998;27:503–507. doi: 10.1093/ageing/27.4.503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eaton WW, Kessler LG. Rates of symptoms of depression in a national sample. American Journal of Epidemiology. 1981;114:528–538. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a113218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Folstein MF, Folstein SE, McHugh PR. Mini-Mental State: A practical method for grading the cognitive state of patients for the clinician. Journal of Psychiatric Research. 1975;12:189–198. doi: 10.1016/0022-3956(75)90026-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Forsell Y, Jorm AF, Winblad B. Suicidal thoughts and associated factors in an elderly population. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavia. 1997;95:108–111. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.1997.tb00382.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gallo JJ, Lebowitz BD. The epidemiology of common late-life mental disorders in the community: Themes for the new century. Psychiatric Services. 1999;50:1158–1168. doi: 10.1176/ps.50.9.1158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gallo JJ, Bogner HR, Morales KH, Ford DE. Patient ethnicity and the identification and active management of depression in late life. Archives of Internal Medicine. 2005;165:1962–1968. doi: 10.1001/archinte.165.17.1962. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gallo JJ, Rebok GW, Tennsted S, Wadley VG, Horgas A, Advanced Cognitive Training for Independent and Vital Elderly (Active) Study Investigators Linking depressive symptoms and functional disability in late life. Aging & Mental Health. 2003;7:469–480. doi: 10.1080/13607860310001594736. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gatz M, Johansson B, Pedersen N, Berg S, Reynolds C. A cross-national self-report measure of depressive symptomatology. International Psychogeriatrics. 1993;5:147–156. doi: 10.1017/s1041610293001486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilewski MJ, Zelinski EM. Memory Functioning Questionnaire (MFQ) Psychopharmacology Bulletin. 1988;24:665–670. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilewski MJ, Zelinski EM, Schaie KW. The Memory Functioning Questionnaire for assessment of memory complaints in adulthood and old age. Psychology and Aging. 1990;5:482–490. doi: 10.1037//0882-7974.5.4.482. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heisel MJ, Flett GL. A psychometric analysis of the Geriatric Hopelessness Scale (GHS): Towards improving assessment of the construct. Journal of Affective Disorders. 2005;87:211–220. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2005.03.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hogervorst E, Combrinck M, Lapuerta P, Rue J, Swales K, Budge M, et al. The Hopkins Verbal Learning Test and screening for dementia. Dementia and Geriatric Cognitive Disorders. 2002;13:13–20. doi: 10.1159/000048628. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jobe JB, Smith DM, Ball K, Tennstedt SL, Marsiske M, Willis SL, et al. ACTIVE: A cognitive intervention trial to promote indepedence in older adults. Controlled Clinical Trials. 2001;22:453–479. doi: 10.1016/s0197-2456(01)00139-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jorm AF, Christensen H, Henderson AS, Korten AE, MacKinnon AJ, Scott R. Complaints of cognitive decline in the elderly: A comparison of reports by subjects and informants in a community survey. Psychological Medicine. 1994;24:365–374. doi: 10.1017/s0033291700027343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jorm AF, Henderson AS, Scott R, Korten AE, Christensen H, MacKinnon AJ. Factors associated with the wish to die in elderly people. Age and Ageing. 1995;24:389–392. doi: 10.1093/ageing/24.5.389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jungwirth S, Fischer P, Weissgram S, Kirchmeyr W, Bauer P, Tragl KH. Subjective memory complaints and objective memory impairment in the Vienna-Transdanube aging community. Journal of the American Geriatric Society. 2004;52:263–268. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2004.52066.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kraemer H, Wilson T, Fairburn C, Agras W. Mediators and moderators of treatment effects in randomized clinical trials. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2002;59:877–883. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.59.10.877. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- La Rue A, Small G, McPherson S, Komo S, Matsuyama S, Jarvik LF. Subjective memory loss in age-associated memory impairment: Family history and neuropsychological correlates. Aging Neuropsychology & Cognition. 1996;3:132–140. [Google Scholar]

- Larrabee GJ, Crook TH. Estimated prevalence of age-associated memory impairment derived from standardized tests of memory function. International Psychogeriatrics. 1994;6:95–104. doi: 10.1017/s1041610294001663. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McDougall GJ. Memory self-efficacy and memory performance among black and white elders. Nursing Research. 2004;53:323–331. doi: 10.1097/00006199-200409000-00007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McHorney CA. Measuring and monitoring general health status in elderly persons: Practical and methodological issues in using the SF-36 health survey. Gerontologist. 1996;36:571–583. doi: 10.1093/geront/36.5.571. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nekanda-Trepka CJS, Bishop S, Blackburn IM. Hopelessness and depression. British Journal of Clinical Psychology. 1983;22:49–60. doi: 10.1111/j.2044-8260.1983.tb00578.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Newmann JP, Engel RJ, Jensen J. Age differences in depressive symptom experiences. Journals of Gerontology: Psychological Sciences. 1991;46:224–235. doi: 10.1093/geronj/46.5.p224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O'Connell H, Chin A, Cunningham C, Lawlor B. Recent developments: Suicide in older people. British Medical Journal. 2004;329:895–899. doi: 10.1136/bmj.329.7471.895. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O'Connor DW, Pollitt PA, Roth M, Brook PB, Reiss BB. Memory complaints and impairment in normal, depressed and demented elderly persons identified in a community survey. Archives of General Psychiatry. 1990;47:224–227. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1990.01810150024005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pearman A, Storandt M. Predictors of subjective memory in older adults. Journals of Gerontology Series B—Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences. 2004;59:4–6. doi: 10.1093/geronb/59.1.p4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prezant DW, Neimeyer RA. Cognitive predictors of depression and suicide ideation. Suicide and Life-Threatening Behavior. 1988;18:259–265. doi: 10.1111/j.1943-278x.1988.tb00161.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Radloff LS. The CES-D Scale: A self-report depression scale for research in the general population. Applied Psychological Measurement. 1977;1:385–401. [Google Scholar]

- Scocco P, Meneghel G, Caon F, Dello Buono M, De Leo D. Death ideation and its correlates: Survey of an over-65-year-old population. Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease. 2001;189:210–218. doi: 10.1097/00005053-200104000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Small GW, Chen ST, Komo S, Ercoli L, Miller K, Siddarth P, et al. Memory self-appraisal and depressive symptoms in people at genetic risk for Alzheimer's disease. International Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry. 2001;16:1071–1077. doi: 10.1002/gps.481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stadnyk K, Calder J, Rockwood K. Testing the measurement properties of the Short Form-36 health survey in a frail elderly population. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology. 1998;51:827–835. doi: 10.1016/s0895-4356(98)00061-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stewart AL, Ware JE, editors. Measuring functioning and well-being. Durham, NC: Duke University Press; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Stewart AL, Greenfield S, Hays RD, Wells K, Rogers WH, Berry SD, et al. Functional status and well-being of patients with chronic conditions: Results from the Medical Outcomes Study. Journal of the American Medical Association. 1989;262:907–913. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stewart AL, Hays RD, Ware JE. The MOS Short-form General Health Survey: Reliability and validity in a patient population. Medical Care. 1988;26:724–735. doi: 10.1097/00005650-198807000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tombaugh TN, McIntyre NJ. The Mini-Mental State Examination: A comprehensive review. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society. 1992;40:922–935. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.1992.tb01992.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turvey CL, Schultz S, Arndt S, Wallace RB, Herzog R. Memory complaint in a community sample aged 70 and older. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society. 2000;48:1435–1441. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2000.tb02634.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang L, van Belle G, Crane P, Kukull WA, Bowen JD, McCormick WC, et al. Subjective memory deterioration and future dementia in people aged 65 and older. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society. 2004;52:2045–2051. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2004.52568.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wetzel RD, Reich T. The cognitive triad and suicide intent in depressed in-patients. Psychological Reports. 1989;65(Pt 1):1027–1032. doi: 10.2466/pr0.1989.65.3.1027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]