Abstract

i) Importance of the field

Emerging evidence demonstrates that several nuclear receptor (NR) family members regulate drug-inducible expression and activity of several important carboxylesterase (CES) enzymes in mammalian liver and intestine. Numerous clinically prescribed anticancer prodrugs, carbamate and pyrethroid insecticides, environmental toxicants, and procarcinogens are substrates for CES enzymes. Moreover, a key strategy employed in rational drug design frequently utilizes an ester linkage methodology to selectively target a prodrug, or to improve the water solubility of a novel compound.

ii) Areas covered in this review

This review will summarize the current state of knowledge regarding NR-mediated regulation of CES enzymes in mammals, and highlight their importance in drug metabolism, drug-drug interactions, and toxicology.

iii) What the reader will gain

New knowledge regarding the transcriptional regulation of CES enzymes by NR proteins pregnane x receptor (PXR, NR1I2) and constitutive androstane receptor (CAR, NR1I3) has recently come to light through the use of knockout and transgenic mouse models. Novel insights regarding the species-specific cross-regulation of glucocorticoid receptor (GR, NR3C1) and peroxisome proliferator activated receptor alpha (PPARα, NR1C1) signaling and CES gene expression is discussed.

iv) Take home message

Elucidation of the role of NR-mediated regulation of CES enzymes in liver and intestine will have a significant impact on rational drug design and the development of novel prodrugs, especially for patients on combination therapy.

Keywords: carboxylesterase, drug metabolism, nuclear receptor, pregnane X receptor, constitutive androstane receptor, xenobiotic response

Introduction

1.1 Classification of Carboxylesterase

In 1953, Aldridge classified esterase enzymes in rabbit, rat, and horse serum based upon the nature of their interaction with organophosphates [1]. Esterases that were unaffected by organophosphates and degraded the compounds were classified as A-esterases, whereas esterases that were inhibited by organophosphates were classified as B-esterases. Studies by Bergmann et al. revealed the presence of a third group of esterases (the C-esterases) that did not interact with organophosphates at all [2]. Using this classification scheme, the superfamily of carboxylesterase (CES) enzymes belong to the B-esterase group. Several attempts have been made to classify the CES enzymes. Walker and Mentlein et al., attempted to classify CES enzymes on the basis of their substrate specificity [3, 4]. However, this classification scheme was ambiguous because of the broad and overlapping substrate specificity of CES enzymes. In 1998, Satoh and Hosokawa originally proposed a novel classification scheme of CES enzymes across species that was based upon the extent of amino acid homology and substrate selectivity [5]. This scheme classified the known CES enzymes into four main groups (CES 1–4), and several additional subgroups. More recently, the same authors have used this same scheme to show that there are five groups of CES enzymes (CES 1–5), and revealed that the majority of identified CES enzymes belong to either the CES 1 or CES 2 sub-family [6]. Importantly, it is now known that the CES-1 and CES-2 sub-families are the major source of carboxylesterase enzymatic activity in liver and intestine tissues that participate in the hydrolysis of drugs and xenobiotics in mammals [6].

1.2 Function of Carboxylesterase Enzymes

The CES family of enzymes is a key participant in the phase-I drug metabolism process, catalyzing the hydrolysis of a wide range of ester- and amide-containing compounds. Of particular clinical relevance, these enzymes participate in the biotransformation of numerous drugs and prodrugs including the anti-platelet drugs aspirin and clopidogrel [7], the angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors delapril, imidapril, and temocapril [8], the anti-tumor drugs irinotecan and pentyl PABC-doxaz [9, 10], the narcotics cocaine and heroin [11], and the anti-influenza prodrug oseltamivir [12, 13]. The CES family of enzymes is involved in the detoxification of environmental toxicants, such as pyrethoids, a major class of insecticides used world wide and extensively in the United States [14]. CES enzymes also play a role in the conversion of pro-carcinogens into carcinogens. For example, vinyl acetate, which is used in the paint, adhesive, and paper-board industry, is metabolized by CES enzymes into acetaldehyde in the liver. Acetaldehyde subsequently binds to DNA and proteins eventually leading to nasal tumor formation in rodents [15]. Numerous endogenous compounds are substrates for CES enzymes including palmitoyl-coenzyme A, short- and long-chain acyl-glycerols, as well as medium- and long-chain acylcarnitines [5, 16]. Because a large number of clinically used drugs and prodrugs are metabolized by CES enzymes, it is important to clarify the structure, substrate selectivity, tissue distribution, and species specificity of CES enzymes.

1.3 Structure of CES Enzymes

The crystal structure of human carboxylesterase 1 (hCE-1) was determined in 2003. The enzyme is comprised of three structural domains: a central catalytic domain, an α/β domain, and a regulatory domain. The central catalytic domain contains the serine hydrolase catalytic triad at the base of the active site gorge, whereas the regulatory domain contains the low-affinity surface ligand-binding Z-site [17, 18]. The CES enzymes are localized in the endoplasmic reticulum and cytosol of many tissues, but are highly enriched in liver and intestine [6, 23] It has been determined that an 18-amino acid N-terminal hydrophobic signal peptide is responsible for the localization of these proteins to the endoplasmic reticulum [19], whereas enzymatic activity is lost by removing the N-terminal domain. The His-X-Glu-Leu (HXEL) sequence present at the C-terminal, which can bind with KDEL receptor, is essential for retention of the protein in the luminal site of the endoplasmic reticulum.

1.4 Substrate Selectivity of CES Enzymes

Amino acid sequence homology between human carboxylesterase 1 (hCE-1), a member of CES 1 family, and human carboxylesterase 2 (hCE-2), which belongs to CES 2 family is 48% [10]. However, the substrate selectivity of these two enzymes is different. The hCE-1 enzyme mainly hydrolyzes substrates with small alcohol groups and large acyl groups, such as cocaine (methyl ester), meperidine, and delapril. In contrast to hCE-1, the hCE-2 enzyme efficiently hydrolyzes compounds with large alcohol groups and relatively smaller carboxylate groups, such as 4-methylumbelliferyl acetate, heroin, and 6-acetylmorphine [20].

1.5 Tissue Distribution of CES Enzymes

The expression of CES enzymes is ubiquitous in mammals. Among various tissues of mammals, the highest hydrolase activity is present in liver [21]. In addition to liver, CES enzymes are also detected in small intestine, kidney, and lung [6]. The hCE-1 enzyme is highly expressed in the liver, and also detected in macrophages, human lung epithelia, heart, and testis [22]. The hCE-2 enzyme is found in the small intestine, colon, kidney, liver, heart, brain, and testis [23, 24]. Although these two enzymes are present in various tissues, hCE-1 and hCE-2 contribute predominantly to the hydrolase activity of liver and small intestine, respectively. It has also been shown that CES enzymes exhibit species differences. For example, Li et al demonstrated that human plasma contains no CES enzyme activity, in contrast, the mouse, rat, rabbit, horse, cat, and tiger all have high levels of plasma CES enzymes [25]. However, in humans it is likely that serum butyrylcholinesterase and paraoxonase enzymes perform analogous functions to the CES enzymes found in serum from these other species.

2. PXR and CAR, Two Xenobiotic-Sensing NRs

As CES enzymes play very important roles in drug metabolism, their expression levels are tightly controlled by the NR proteins pregnane X receptor (PXR, NR1I2) and constitutive androstane receptor (CAR, NR1I3). NR proteins comprise a large superfamily of ligand-activated transcription factors that are involved in diverse physiological, developmental, and metabolic processes. They are characterized by a conserved N-terminal zinc-finger type DNA-binding domain and a C-terminal ligand-binding domain [26]. The PXR and CAR proteins are two closely related members of this superfamily. Both of these proteins function as ligand-activated transcription factors by interacting with the retinoid-x-receptor-alpha (RXRα, NR2B1) on response elements located in the control regions of specific genes that they regulate.

PXR functions as a master-regulator of xenobiotic- and drug-inducible cytochrome P450 (CYP) gene expression in liver and it is now well established that PXR regulates the drug-inducible expression and activity of numerous genes that encode key members of the CYP3A, CYP2B and CYP2C subfamily of drug-metabolizing enzymes in humans and rodents [27, 28]. PXR also regulates the drug-inducible expression of other genes whose gene products are involved in the metabolism of xenobiotic compounds including glutathione S-transferase, sulfotransferase, and UDP-glucuronosyltransferase enzymes in liver [29-32]. Moreover, additional PXR-target genes encode key hepatic drug transporter proteins such as organic anion transporting polypeptide 2, multidrug resistance 1/P-glycoprotein, and multidrug resistance proteins 2 and 3 [33-35].

Similar to PXR, the NR superfamily member CAR is also recognized as a xenobiotic-sensing NR mainly expressed in hepatic tissue. It was originally demonstrated to regulate the phenobarbital-inducible expression of several genes encoding important members of the CYP2B subfamily of enzymes [36]. CAR has since been shown to regulate the expression and activity of a number of phase-I and phase-II metabolic enzymes, as well as the expression and activity of numerous important membrane transporter proteins involved in the metabolism and elimination of xenobiotics [37]. It has been demonstrated that PXR and CAR share distinct but overlapping sets of target genes involved in drug and xenobiotic metabolism, often through shared NR-response elements. For instance, PXR can regulate CYP2B genes through recognition of the Phenobarbital-response element (PBREM), whereas CAR is also found to activate gene expression through the xenobiotic response element (XREM) in the upstream promoter of the CYP3A4 gene in humans [29, 38, 39]. Because PXR and CAR are activated by a myriad of xenobiotic compounds and regulate the expression of numerous genes involved in drug and xenobiotic metabolism, the activation of these two receptors serves as a principal defense mechanism defending the body from toxic insult. In this way, activation of PXR and CAR by xenobiotic compounds and drugs coordinately regulates the expression and activity of functionally linked metabolic enzymes and membrane-bound transporter proteins to increase the elimination of potentially toxic compounds from the body [27, 32, 39-41]. Additionally, these two transcription factors form the molecular basis of an important class of drug-drug interactions in the clinical setting. PXR and CAR-mediated gene activation by one drug increases the metabolism and elimination of a myriad of other co-administered drugs from the body.

3. Regulation of CES Enzymes by PXR and CAR

3.1 Regulation by PXR

Studies by Zhu et al. show the involvement of PXR and the glucocorticoid receptor (GR, NR3C1) in regulating the species-specific expression and activity of the homologous enzymes in both rat and human model systems [42]. The hCE-1 and hCE-2 genes encode the two major forms of human liver microsomal carboxylesterase enzymes. Exposure of primary cultures of human hepatocytes to micromolar concentrations of dexamethasone induces hCE-1 and hCE-2 protein expression in a concentration-dependent manner. In contrast, exposure of rat hepatocytes to nanomolar concentrations of dexamethasone represses the expression of carboxylesterase genes [43]. The GR serves as a master-regulator of glucocorticoid-regulated gene expression in response to nanomolar concentrations of glucocorticoids. It is interesting to note that the promoter sequences of hydrolase B and S that contribute to the repression of CES enzymes lack any canonical GR-response elements. This suggests that the GR-mediated suppression of CES gene expression in rats is achieved via a non-classical mechanism. In contrast to rats, treatment of human hepatocytes with ten micromolar rifampicin, the prototypical human PXR-activating compound, causes moderate induction of hCE-1 and hCE-2 gene expression [43]. Interestingly, treatment of cultured human hepatocytes with 8-methoxypsoralen, which is a prototypical photochemotherapeutic drug, increases hCE-2 gene expression [13]. Moreover, knockdown of PXR using si-RNA technology decreases hCE-2 mRNA levels, whereas over-expression of the PXR protein significantly increases hCE-2 expression at both the messenger RNA and protein levels.

PXR also exerts a positive effect on liver-enriched expression of CES enzymes in rodents. In rats, the best characterized carboxylesterase enzymes include hydrolase A, B and S (HA, HB, HS). Co-transfection of PXR stimulates the promoter activity of HB and HS in response to dexamethasone at micromolar concentrations [43]. Tully et al. characterized the effects of triazole fungicides in SD rats using microarray analysis [31]. Gene expression profiling of liver shows induction of Ces2 is produced by four triazole fungicides, and is likely dependent on PXR/CAR-mediated gene activation pathways. A similar study by Goetz et al., utilized gene expression profiling of the liver of CD-1 mice treated with four triazole fungicides. Expression of the Ces2 gene is induced by three triazole fungicides, suggesting involvement of PXR/CAR-regulated pathways in triazole metabolism and perhaps toxicity [44]. Earlier research by Rosenfeld et al., indicates that over-expression of a constitutively active form of human PXR in mouse liver has a positive effect on the expression of mouse genes encoding Ces2 and Ces3 enzymes in liver [45].

The mouse Ces6 gene was first identified in 2004 and encodes a protein of 558 amino acid residues in length that functions to hydrolyze select pyrethroid compounds [46]. Recently, our lab has demonstrated that the Ces6 gene represents a likely PXR-target gene in mouse liver and small intestine [47]. By exploiting the PXR knockout mouse model, we reveal that induction of Ces6 messenger RNA and protein by pregnenalone 16α-carbonitrile (PCN), a well known rodent PXR activator, is PXR-dependent in both mouse liver and intestine.

3.2 Regulation by CAR

Compared to PXR, relatively little is known about the regulation of drug-inducible CES gene expression by CAR activation in any species or tissue. Historical reports indicate that treatment of rats with phenobarbital (PB) increases CES expression in liver tissue [48]. Studies from Xu et al. show that Ces6 represents a CAR-target gene in mouse liver and small intestine [47]. It is interesting to note that in small intestine, the expression of Ces6 is exclusively regulated by 1,4-Bis[2-(3,5-dichloropyridyloxy)]benzene (TCPOBOP) but not by PB, both of which are CAR activators. These data suggest that there may be differences in the bioavailability of PB and TCPOBOP, or perhaps the differences in the mode of CAR activation by these two ligands in small intestine are responsible for the absence of Ces6 gene activation by PB. Moreover, TCPOBOP is a much more potent and efficacious activator of rodent CAR, thus is a much more effective chemical to use in rodent studies.

3.3 Coordinate Regulation of Gene Expression by PXR and CAR

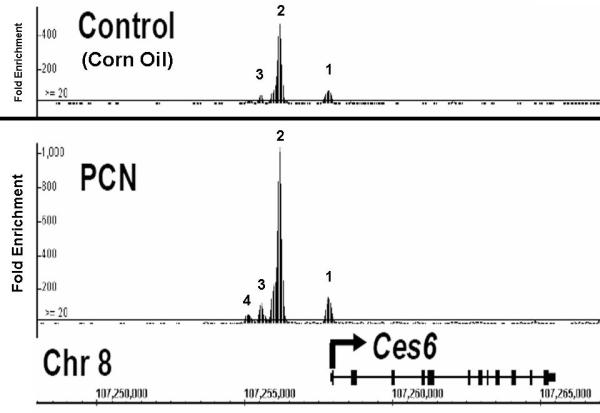

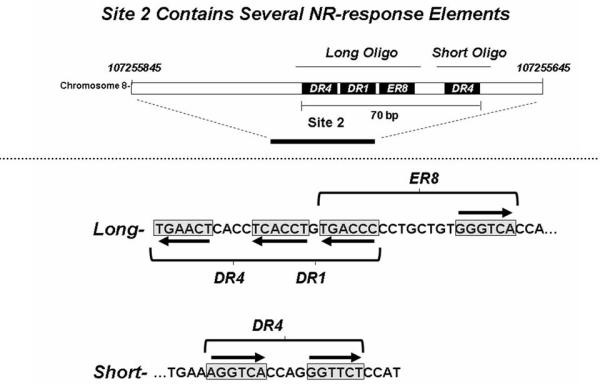

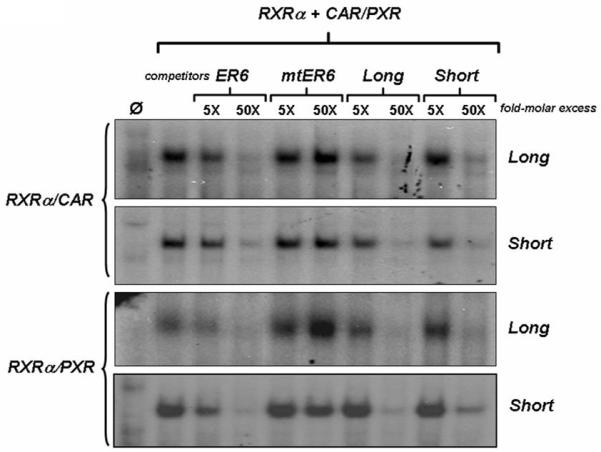

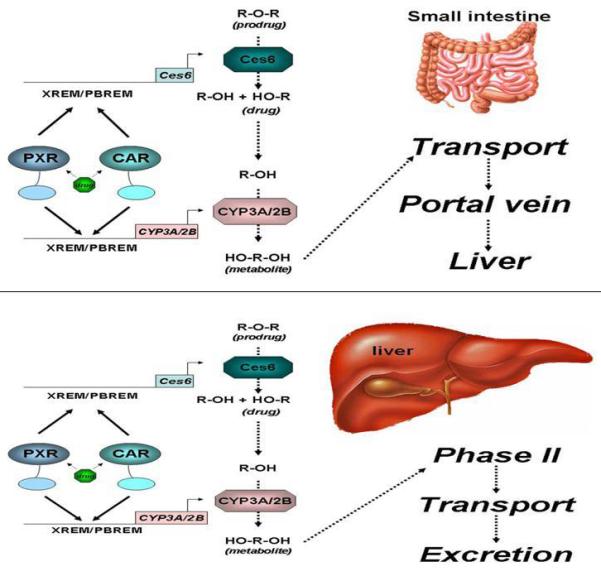

Using ChIP-seqeuencing analysis of control and PCN-treated mouse livers, we observed constitutive PXR-binding to three enhancer elements located in the upstream region of the mouse Ces6 gene under physiological conditions (figure 1, top panel), which are approximately 84bp (site 1), 1796bp (site 2), and 2340bp (site 3) upstream of the transcription start site of Ces6. Most interestingly, treatment with the mouse PXR agonist PCN produces an approximately 2-fold overall increase in PXR binding to all the three sites, particularly to the second site (site 2), which binds to PXR with the highest affinity. In addition, a new PXR binding site occurs further upstream (−2772bp) with moderate fold-enrichment (average value = 40) (figure 1, bottom panel). Close examination of the DNA sequences that constitute site 2 reveals a cluster of likely NR-response elements located within 70 base pairs of each other and these are depicted in figure 2. Using two oligonucleotides, designated as ‘long’ and ‘short’, derived from this DNA sequence we performed electrophoretic mobility-shift analysis and show that both CAR/RXRα and PXR/RXRα protein complexes bind directly to these putative response elements (figure 3). Importantly, competition-binding using an oligonucleotide that comprises the prototypical shared PXR/CAR response element, an everted repeat spaced by 6 nucleotides (ER6) derived from the well-characterized promoter of the CYP3A4 gene, shows that binding to the putative Ces6 response elements is specific. Conversely, a mutant form of the same oligonucleotide (mtER6) did not compete for binding, whereas the homologous oligonucleotides comprising the ‘long’ and ‘short’ experimental oligonucleotides compete well for binding of both the CAR/RXRα and PXR/RXRα protein complexes. Hence, the PXR and CAR NR superfamily members play direct and competitive roles in regulating the drug-inducible expression and activity of an important liver- and intestine-enriched mouse CES enzyme. Together with numerous other drug-metabolizing enzymes and drug transporter proteins in liver and intestine, PXR and CAR regulate the expression and activity of key CES enzymes that coordinately determine the pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic properties of numerous clinically prescribed and xenobiotic compounds in vivo in liver and intestine. Taken together, the data lead to a model in which drug-inducible activation of intestinal CES activity in intestine would be expected to increase the conversion of prodrugs to the active form of the drug, thereby increasing transport to portal vein and liver (figure 4). In the liver, high levels of cytochrome P450 and CES activity would be expected to further increase metabolism of co-administered drugs, thereby leading to increased prospects for drug-drug interaction in patients on combination therapy. Moreover, activation of these pathways by PXR and CAR would be expected to increase the conversion of pro-carcinogens into carcinogenic compounds in these tissues.

Figure 1.

Figure 2.

Figure 3.

Figure 4.

4. Other NRs Regulate CES Enzymes

In addition to PXR and CAR, CES enzymes are also regulated by other NR proteins, such as hepatocyte nuclear factor-4α (HNF-4α, NR2A1), peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor α (PPARα, NR1C1), and glucocorticoid receptor (GR, NR3C1). HNF-4α is mainly expressed in liver, intestine, pancreas and kidney, and is critical for transcriptional regulation of many genes in liver, such as Cyp7a1, CAR, and genes involved in the control of lipid homeostasis, glucose transport and glycolysis [49-52]. HNF-4α has also been implicated in the regulation of mouse Ces2 gene transcription. In the same study, bile acids are shown to repress expression of mCES2 by inhibiting the HNF-4α-mediated transactivation of the mCES2 gene promoter [53].

Proxisome proliferator-activated receptors (PPARs) are mainly involved in lipid and glucose homeostasis, control of inflammation and wound healing, and regulation of food intake and body weight [54, 55]. However, there appears to be a connection between PPARs and hepatic CES gene expression in rodents as well. The PPARα protein, one of the three subtypes of PPARs, is predominantly expressed in tissues with a high oxidative capacity such as heart and liver. Research by Poole et al. showed that exposure to peroxisome proliferators, strong activators of PPARα in liver, leads to down-regulation of the expression of CES family members. The alteration in CES expression is dependent on the PPARα protein in mouse [56].

5. Conclusions

NRs are key regulators of many drug metabolizing enzymes that play diverse roles in xenobiotic and endobiotic metabolism. This review summarizes the evidence that several key NR proteins, including PXR, CAR, HNF-4α, PPARα, and GR, are involved in the regulation of CES enzymes. Because CES enzymes are one of the major determinants of the metabolism and disposition of numerous prodrugs through their actions in liver and small intestine, elucidating the mechanism governing the regulation of CES enzyme expression and activity by NR proteins will have a significant impact on rational drug design and the future development of prodrugs.

6. Expert Opinion

It is well known that activation of NRs, such as PXR and CAR, coordinately regulates the expression and activity of numerous drug-metabolizing enzymes as well as multiple drug transporter proteins. Not only can this coordinated regulation protect cells from toxic insult, but it also represents the molecular basis for an important class of drug-drug interactions in clinical settings. For example in multi-drug therapy, if one drug activates PXR and/or CAR, and the other is administered as a prodrug that is metabolized and eliminated by PXR/CAR-target genes, the resulting increased biotransformation of the prodrug into an active drug would probably lead to markedly discrepant pharmacological activities and pharmacokinetic behavior, or even serious and toxic side effects. As is the case with several anticancer drugs, there is an emerging role for PXR and CAR in regulating CES enzymes that exert an important effect on the hydrolytic biotransformation of a number of clinically used drugs and prodrugs. Additional evidence is emerging which points to a key role for PXR in regulating blood-brain barrier permeability in response to drug treatment [57, 58], and also in modulation of multi-drug resistance and estrogen sensitivity in certain breast cancers [59, 60]. Further elucidation of the role of the PXR protein in these clinically significant areas will likely produce important information that could be exploited as novel targets for cancer treatments.

Numerous classes of xenobiotic compounds activate either PXR or CAR including numerous clinically prescribed drugs, active compounds in popular herbal remedies, several prodrugs that are anti-cancer agents, drug metabolites, and the list is growing. Activation of these receptors by anti-cancer drugs would be expected to have profound impact on the pharmacokinetics of drug metabolism in patients taking prodrugs activated by CES and eliminated by the action of the CYP3A4 enzyme in liver. Moreover, both PXR and CAR activities appear to be modulated through alterations in post-translational modifications such as phosphorylation [61, 62, 63, 64]. It is likely that these and other key signaling pathways are altered in patients experiencing disease states such as inflammation or diabetes. There is increasing recognition that key drug metabolism pathways are under metabolic control, and are altered in patients who are administered drugs while fasting or are cachectic. Because the activity of PXR and CAR proteins also appear to be under metabolic control [62, 64], these two transcription factors are likely to be, in part, responsible for such alterations. If true, this would have enormous implications in the field of drug-drug interactions in the most ill cancer patients that are undergoing polytherapy with simultaneous pharmacological interventions who are experiencing cachexia. More research needs to be conducted into the possible metabolic control of PXR and CAR activity.

The observation that treatment with GR and PPARα agonists produces repression of CES gene expression in rodent models could also have a significant impact on patient care. If the same is true for humans, it would be expected that the numerous clinically prescribed medications and newly discovered drug candidates that work through GR and PPARα would suppress the biotransformation of the anticancer prodrugs that are targeted for biotransformation by CES enzymes. Obviously, more research is necessary to clearly elucidate differences in the regulation of drug-inducible expression and activity of CES enzymes in liver and intestine across species. This is particularly important because of the use of rodent models to determine drug efficacy and drug toxicity screening by the pharmaceutical industry. Thus, continued research using knockout mice, “humanized” mouse models, and human cell-based model systems will undoubtedly contribute significant knowledge that will elucidate the molecular mechanisms governing the regulation of CES enzyme expression and drug metabolism activity by these important metabolic enzymes. This thrust of research highlights the importance of monitoring the ratio and efficacy of the conversion of prodrug into active drug in patients receiving novel combination therapies.

Acknowledgements

We apologize for many valuable publications that cannot be included in this review due to space limitations. Funding provided by NIH grant DK068443 to J.L.S.

Footnotes

Declaration of interest

The authors state no conflicts of interest and have received no payment in the preparation of this manuscript.

Bibliography

Papers of special note have been highlighted as either of interest (•) or of considerable interest (••) to readers.

- 1.Aldridge WN. Serum esterases. I. Two types of esterase (A and B) hydrolysing p-nitrophenyl acetate, propionate and butyrate, and a method for their determination. Biochem J. 1953;53:110–7. doi: 10.1042/bj0530110. (•) One of the first reports on classification of esterases.

- 2.Bergmann F, Segal R, Rimon S. A new type of esterase in hog-kidney extract. Biochem J. 1957;67:481–6. doi: 10.1042/bj0670481. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Walker CH, Mackness MI. Esterases: problems of identification and classification. Biochem Pharmacol. 1983;32:3265–9. doi: 10.1016/0006-2952(83)90349-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mentlein R, Suttorp M, Heymann E. Specificity of purified monoacylglycerol lipase, palmitoyl-CoA hydrolase, palmitoyl-carnitine hydrolase, and nonspecific carboxylesterase from rat liver microsomes. Arch Biochem Biophys. 1984;228:230–46. doi: 10.1016/0003-9861(84)90064-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Satoh T, Hosokawa M. The mammalian carboxylesterases: from molecules to functions. Annu Rev Pharmacol Toxicol. 1998;38:257–88. doi: 10.1146/annurev.pharmtox.38.1.257. (••) An excellent review with great details on biology of carboxylesterases.

- 6.Satoh T, Hosokawa M. Structure, function and regulation of carboxylesterases. Chem Biol Interact. 2006;162:195–211. doi: 10.1016/j.cbi.2006.07.001. (••) Another excellent review with newer details on biology of carboxylesterases.

- 7.Tang M, Mukundan M, Yang J, Charpentier N, LeCluyse EL, Black C, et al. Antiplatelet agents aspirin and clopidogrel are hydrolyzed by distinct carboxylesterases, and clopidogrel is transesterificated in the presence of ethyl alcohol. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2006;319:1467–76. doi: 10.1124/jpet.106.110577. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Takai S, Matsuda A, Usami Y, Adachi T, Sugiyama T, Katagiri Y, et al. Hydrolytic profile for ester- or amide-linkage by carboxylesterases pI 5.3 and 4.5 from human liver. Biol Pharm Bull. 1997;20:869–73. doi: 10.1248/bpb.20.869. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Barthel BL, Torres RC, Hyatt JL, Edwards CC, Hatfield MJ, Potter PM, et al. Identification of human intestinal carboxylesterase as the primary enzyme for activation of a doxazolidine carbamate prodrug. J Med Chem. 2008;51:298–304. doi: 10.1021/jm7011479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Humerickhouse R, Lohrbach K, Li L, Bosron WF, Dolan ME. Characterization of CPT-11 hydrolysis by human liver carboxylesterase isoforms hCE-1 and hCE-2. Cancer Res. 2000;60:1189–92. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pindel EV, Kedishvili NY, Abraham TL, Brzezinski MR, Zhang J, Dean RA, et al. Purification and cloning of a broad substrate specificity human liver carboxylesterase that catalyzes the hydrolysis of cocaine and heroin. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:14769–75. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.23.14769. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Shi D, Yang J, Yang D, LeCluyse EL, Black C, You L, et al. Anti-influenza prodrug oseltamivir is activated by carboxylesterase human carboxylesterase 1, and the activation is inhibited by antiplatelet agent clopidogrel. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2006;319:1477–84. doi: 10.1124/jpet.106.111807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Yang D, Pearce RE, Wang X, Gaedigk R, Wan YJ, Yan B. Human carboxylesterases HCE1 and HCE2: ontogenic expression, inter-individual variability and differential hydrolysis of oseltamivir, aspirin, deltamethrin and permethrin. Biochem Pharmacol. 2009;77:238–47. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2008.10.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Nishi K, Huang H, Kamita SG, Kim IH, Morisseau C, Hammock BD. Characterization of pyrethroid hydrolysis by the human liver carboxylesterases hCE-1 and hCE-2. Arch Biochem Biophys. 2006;445:115–23. doi: 10.1016/j.abb.2005.11.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kuykendall JR, Taylor ML, Bogdanffy MS. Cytotoxicity and DNA-protein crosslink formation in rat nasal tissues exposed to vinyl acetate are carboxylesterase-mediated. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol. 1993;123:283–92. doi: 10.1006/taap.1993.1247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Furihata T, Hosokawa M, Nakata F, Satoh T, Chiba K. Purification, molecular cloning, and functional expression of inducible liver acylcarnitine hydrolase in C57BL/6 mouse, belonging to the carboxylesterase multigene family. Arch Biochem Biophys. 2003;416:101–9. doi: 10.1016/s0003-9861(03)00286-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bencharit S, Morton CL, Hyatt JL, Kuhn P, Danks MK, Potter PM, et al. Crystal structure of human carboxylesterase 1 complexed with the Alzheimer’s drug tacrine: from binding promiscuity to selective inhibition. Chem Biol. 2003;10:341–9. doi: 10.1016/s1074-5521(03)00071-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bencharit S, Morton CL, Xue Y, Potter PM, Redinbo MR. Structural basis of heroin and cocaine metabolism by a promiscuous human drug-processing enzyme. Nat Struct Biol. 2003;10:349–56. doi: 10.1038/nsb919. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Potter PM, Wolverton JS, Morton CL, Wierdl M, Danks MK. Cellular localization domains of a rabbit and a human carboxylesterase: influence on irinotecan (CPT-11) metabolism by the rabbit enzyme. Cancer Res. 1998;58:3627–32. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Satoh T, Taylor P, Bosron WF, Sanghani SP, Hosokawa M, La Du BN. Current progress on esterases: from molecular structure to function. Drug Metab Dispos. 2002;30:488–93. doi: 10.1124/dmd.30.5.488. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hosokawa M, Suzuki K, Takahashi D, Mori M, Satoh T, Chiba K. Purification, molecular cloning, and functional expression of dog liver microsomal acyl-CoA hydrolase: a member of the carboxylesterase multigene family. Arch Biochem Biophys. 2001;389:245–53. doi: 10.1006/abbi.2001.2346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Munger JS, Shi GP, Mark EA, Chin DT, Gerard C, Chapman HA. A serine esterase released by human alveolar macrophages is closely related to liver microsomal carboxylesterases. J Biol Chem. 1991;266:18832–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Schwer H, Langmann T, Daig R, Becker A, Aslanidis C, Schmitz G. Molecular cloning and characterization of a novel putative carboxylesterase, present in human intestine and liver. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1997;233:117–20. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1997.6413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Xu G, Zhang W, Ma MK, McLeod HL. Human carboxylesterase 2 is commonly expressed in tumor tissue and is correlated with activation of irinotecan. Clin Cancer Res. 2002;8:2605–11. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Li B, Sedlacek M, Manoharan I, Boopathy R, Duysen EG, Masson P, et al. Butyrylcholinesterase, paraoxonase, and albumin esterase, but not carboxylesterase, are present in human plasma. Biochem Pharmacol. 2005;70:1673–84. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2005.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mangelsdorf DJ, Thummel C, Beato M, Herrlich P, Schutz G, Umesono K, et al. The nuclear receptor superfamily: the second decade. Cell. 1995;83:835–9. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90199-x. (••) An excellent review on nuclear receptors.

- 27.Goodwin B, Redinbo MR, Kliewer SA. Regulation of cyp3a gene transcription by the pregnane x receptor. Annu Rev Pharmacol Toxicol. 2002;42:1–23. doi: 10.1146/annurev.pharmtox.42.111901.111051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kliewer SA, Goodwin B, Willson TM. The nuclear pregnane X receptor: a key regulator of xenobiotic metabolism. Endocr Rev. 2002;23:687–702. doi: 10.1210/er.2001-0038. (••) An excellent review on the role of PXR in regulating xenobiotic metabolism.

- 29.Maglich JM, Stoltz CM, Goodwin B, Hawkins-Brown D, Moore JT, Kliewer SA. Nuclear pregnane x receptor and constitutive androstane receptor regulate overlapping but distinct sets of genes involved in xenobiotic detoxification. Mol Pharmacol. 2002;62:638–46. doi: 10.1124/mol.62.3.638. (•) One of the first reports showing PXR and CAR share overlapping but distinct target genes.

- 30.Sonoda J, Xie W, Rosenfeld JM, Barwick JL, Guzelian PS, Evans RM. Regulation of a xenobiotic sulfonation cascade by nuclear pregnane X receptor (PXR) Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2002;99:13801–6. doi: 10.1073/pnas.212494599. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Tully DB, Bao W, Goetz AK, Blystone CR, Ren H, Schmid JE, et al. Gene expression profiling in liver and testis of rats to characterize the toxicity of triazole fungicides. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol. 2006;215:260–73. doi: 10.1016/j.taap.2006.02.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wei P, Zhang J, Dowhan DH, Han Y, Moore DD. Specific and overlapping functions of the nuclear hormone receptors CAR and PXR in xenobiotic response. Pharmacogenomics J. 2002;2:117–26. doi: 10.1038/sj.tpj.6500087. (•) One of the first reports showing PXR and CAR share overlapping but distinct target genes.

- 33.Geick A, Eichelbaum M, Burk O. Nuclear receptor response elements mediate induction of intestinal MDR1 by rifampin. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:14581–7. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M010173200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kast HR, Goodwin B, Tarr PT, Jones SA, Anisfeld AM, Stoltz CM, et al. Regulation of multidrug resistance-associated protein 2 (ABCC2) by the nuclear receptors pregnane X receptor, farnesoid X-activated receptor, and constitutive androstane receptor. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:2908–15. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109326200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Staudinger JL, Madan A, Carol KM, Parkinson A. Regulation of drug transporter gene expression by nuclear receptors. Drug Metab Dispos. 2003;31:523–7. doi: 10.1124/dmd.31.5.523. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Honkakoski P, Zelko I, Sueyoshi T, Negishi M. The nuclear orphan receptor CAR-retinoid X receptor heterodimer activates the phenobarbital-responsive enhancer module of the CYP2B gene. Mol Cell Biol. 1998;18:5652–8. doi: 10.1128/mcb.18.10.5652. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ueda A, Hamadeh HK, Webb HK, Yamamoto Y, Sueyoshi T, Afshari CA, et al. Diverse roles of the nuclear orphan receptor CAR in regulating hepatic genes in response to phenobarbital. Mol Pharmacol. 2002;61:1–6. doi: 10.1124/mol.61.1.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Goodwin B, Moore LB, Stoltz CM, McKee DD, Kliewer SA. Regulation of the human CYP2B6 gene by the nuclear pregnane X receptor. Mol Pharmacol. 2001;60:427–31. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Xie W, Barwick JL, Simon CM, Pierce AM, Safe S, Blumberg B, et al. Reciprocal activation of xenobiotic response genes by nuclear receptors SXR/PXR and CAR. Genes Dev. 2000;14:3014–23. doi: 10.1101/gad.846800. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Moore LB, Maglich JM, McKee DD, Wisely B, Willson TM, Kliewer SA, et al. Pregnane X receptor (PXR), constitutive androstane receptor (CAR), and benzoate X receptor (BXR) define three pharmacologically distinct classes of nuclear receptors. Mol Endocrinol. 2002;16:977–86. doi: 10.1210/mend.16.5.0828. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Moore LB, Parks DJ, Jones SA, Bledsoe RK, Consler TG, Stimmel JB, et al. Orphan nuclear receptors constitutive androstane receptor and pregnane X receptor share xenobiotic and steroid ligands. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:15122–7. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M001215200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Zhu W, Song L, Zhang H, Matoney L, LeCluyse E, Yan B. Dexamethasone differentially regulates expression of carboxylesterase genes in humans and rats. Drug Metab Dispos. 2000;28:186–91. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Shi D, Yang J, Yang D, Yan B. Dexamethasone suppresses the expression of multiple rat carboxylesterases through transcriptional repression: evidence for an involvement of the glucocorticoid receptor. Toxicology. 2008;254:97–105. doi: 10.1016/j.tox.2008.09.019. (•) This study shows evidence for an involvement of GR in regulating carboxylesterase.

- 44.Goetz AK, Bao W, Ren H, Schmid JE, Tully DB, Wood C, et al. Gene expression profiling in the liver of CD-1 mice to characterize the hepatotoxicity of triazole fungicides. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol. 2006;215:274–84. doi: 10.1016/j.taap.2006.02.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Rosenfeld JM, Vargas R, Jr., Xie W, Evans RM. Genetic profiling defines the xenobiotic gene network controlled by the nuclear receptor pregnane X receptor. Mol Endocrinol. 2003;17:1268–82. doi: 10.1210/me.2002-0421. (•) This paper was the first to analyze PXR target genes globally by gene chips.

- 46.Stok JE, Huang H, Jones PD, Wheelock CE, Morisseau C, Hammock BD. Identification, expression, and purification of a pyrethroid-hydrolyzing carboxylesterase from mouse liver microsomes. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:29863–9. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M403673200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Xu C, Wang X, Staudinger JL. Regulation of tissue-specific carboxylesterase expression by pregnane x receptor and constitutive androstane receptor. Drug Metab Dispos. 2009;37:1539–47. doi: 10.1124/dmd.109.026989. (•) This paper was the first to show that carboxylesterase can be regulated by PXR and CAR in vivo.

- 48.Hosokawa M, Maki T, Satoh T. Multiplicity and regulation of hepatic microsomal carboxylesterases in rats. Mol Pharmacol. 1987;31:579–84. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Ding X, Lichti K, Kim I, Gonzalez FJ, Staudinger JL. Regulation of constitutive androstane receptor and its target genes by fasting, cAMP, hepatocyte nuclear factor alpha, and the coactivator peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma coactivator-1alpha. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:26540–51. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M600931200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Hayhurst GP, Lee YH, Lambert G, Ward JM, Gonzalez FJ. Hepatocyte nuclear factor 4alpha (nuclear receptor 2A1) is essential for maintenance of hepatic gene expression and lipid homeostasis. Mol Cell Biol. 2001;21:1393–403. doi: 10.1128/MCB.21.4.1393-1403.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Stoffel M, Duncan SA. The maturity-onset diabetes of the young (MODY1) transcription factor HNF4alpha regulates expression of genes required for glucose transport and metabolism. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1997;94:13209–14. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.24.13209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Stroup D, Chiang JY. HNF4 and COUP-TFII interact to modulate transcription of the cholesterol 7alpha-hydroxylase gene (CYP7A1) J Lipid Res. 2000;41:1–11. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Furihata T, Hosokawa M, Masuda M, Satoh T, Chiba K. Hepatocyte nuclear factor-4alpha plays pivotal roles in the regulation of mouse carboxylesterase 2 gene transcription in mouse liver. Arch Biochem Biophys. 2006;447:107–17. doi: 10.1016/j.abb.2006.01.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Desvergne B, Wahli W. Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptors: nuclear control of metabolism. Endocr Rev. 1999;20:649–88. doi: 10.1210/edrv.20.5.0380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Escher P, Wahli W. Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptors: insight into multiple cellular functions. Mutat Res. 2000;448:121–38. doi: 10.1016/s0027-5107(99)00231-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Poole M, Bridgers K, Alexson SE, Corton JC. Altered expression of the carboxylesterases ES-4 and ES-10 by peroxisome proliferator chemicals. Toxicology. 2001;165:109–19. doi: 10.1016/s0300-483x(01)00416-4. (•) This report shows that exposure to activators for PPARα regulates expression of carboxylesterase.

- 57.Ott M, Fricker G, Bauer B. Pregnane X receptor (PXR) regulates P-glycoprotein at the blood-brain barrier: functional similarities between pig and human PXR. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2009;329:141–9. doi: 10.1124/jpet.108.149690. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Bauer B, Hartz AM, Lucking JR, Yang X, Pollack GM, Miller DS. Coordinated nuclear receptor regulation of the efflux transporter, Mrp2, and the phase-II metabolizing enzyme, GSTpi, at the blood-brain barrier. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2008;28:1222–34. doi: 10.1038/jcbfm.2008.16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Abbas S, Brauch H, Chang-Claude J, Dunnebier T, Flesch-Janys D, Hamann U, et al. Polymorphisms in genes of the steroid receptor superfamily modify postmenopausal breast cancer risk associated with menopausal hormone therapy. Int J Cancer. 2009 doi: 10.1002/ijc.24892. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Meyer zu Schwabedissen HE, Tirona RG, Yip CS, Ho RH, Kim RB. Interplay between the nuclear receptor pregnane X receptor and the uptake transporter organic anion transporter polypeptide 1A2 selectively enhances estrogen effects in breast cancer. Cancer Res. 2008;68:9338–47. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-0265. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Lichti-Kaiser K, Brobst D, Xu C, Staudinger JL. A systematic analysis of predicted phosphorylation sites within the human pregnane X receptor protein. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2009;331:65–76. doi: 10.1124/jpet.109.157180. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Lichti-Kaiser K, Xu C, Staudinger JL. Cyclic AMP-dependent protein kinase signaling modulates pregnane x receptor activity in a species-specific manner. J Biol Chem. 2009;284:6639–49. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M807426200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Hosseinpour F, Moore R, Negishi M, Sueyoshi T. Serine 202 regulates the nuclear translocation of constitutive active/androstane receptor. Mol Pharmacol. 2006;69:1095–102. doi: 10.1124/mol.105.019505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Wada T, Gao J, Xie W. PXR and CAR in energy metabolism. Trends Endocrinol Metab. 2009;20:273–9. doi: 10.1016/j.tem.2009.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]