Abstract

Objectives

To estimate the incidences of caesarean sections in Latin American countries and correlate these with socioeconomic, demographic, and healthcare variables.

Design

Descriptive and ecological study.

Setting

19 Latin American countries.

Main outcome measures

National estimates of caesarean section rates in each country.

Results

Seven countries had caesarean section rates below 15%. The remaining 12 countries had rates above 15% (range 16.8% to 40.0%). These 12 countries account for 81% of the deliveries in the region. A positive and significant correlation was observed between the gross national product per capita and rate of caesarean section (rs=0.746), and higher rates were observed in private hospitals than in public ones. Taking 15% as a medically justified accepted rate, over 850 000 unnecessary caesarean sections are performed each year in the region.

Conclusions

The reported figures represent an unnecessary increased risk for young women and their babies. From the economic perspective, this is a burden to health systems that work with limited budgets.

Key messages

12 of the 19 Latin American countries studied had caesarean section rates above 15%, ranging from 16.8% to 40%

These12 countries account for 81% of the deliveries in the region

Better socioeconomic conditions were associated with higher caesarean section rates

Over 850 000 unnecessary caesarean sections are performed each year in Latin America

Reduction of caesarean section rates will need concerted action from public health authorities, medical associations, medical schools, health professionals, the general population, and the media

Introduction

Caesarean sections increase the health risks for mothers and babies as well as the costs of health care compared with normal deliveries.1–5 Concern has been expressed at the growing rates of caesarean section in some countries of Latin America over the past few years.6,7 Some developed countries have apparently controlled the increase in caesarean section, although the rates may still be high.8–10 However, in other developed countries, caesarean section rates are still increasing and are a matter of concern.11,12

Information on rates of caesarean section is not easily obtained for most Latin American countries because of a lack of good national records. We estimated the recent incidence of caesarean section in several Latin American countries using different sources of information and correlated these rates with the socioeconomic, demographic, and health variables.

Methods

We studied the Spanish, Portuguese, and French speaking American developing countries. Belize, Surinam, Guyana, and the English and Dutch speaking Caribbean countries were not included. Assistance with deliveries in all Latin American countries is provided by at least two types of hospital: public and private. Public hospitals are free of charge for anyone whereas private hospitals charge patients for their assistance directly or indirectly through private health insurance. Some countries (such as Guatemala, Colombia, and Mexico) also have social security hospitals, which are free of charge but open only to people with jobs affiliated to the social security system and their families.

Sources of data

We contacted various institutions in the countries, such as ministries of health, statistical departments, scientific organisations, social security systems, and hospitals, through representatives of the Pan American Health Organisation. We requested figures for caesarean section at national, regional, or institutional levels. The information obtained came from reports of government health offices derived from routine statistical surveillance or national surveys (Argentina, Bolivia, Brazil, Ecuador, Venezuela, Mexico, Uruguay, Paraguay, El Salvador, Guatemala), the social security system(Costa Rica, Argentina, El Salvador), committees for promotion of maternal health (Mexico), private hospitals (Paraguay), and private health insurance companies (Argentina).

Data from the Demographic and Health Surveys Program were retrieved for surveys made in Latin American countries since 1990.13 The demographic and health surveys collect information on fertility and family planning, maternal and child health, child survival, AIDS and sexually transmitted infections, and other reproductive health topics. Surveys are implemented by institutions in the host country, usually government statistical offices, and 4000 to 8000 women of childbearing age are interviewed in a standard survey. Data from the last surveys made in Bolivia, Colombia, Haiti, Peru, and Dominican Republic were used.

We also used data from the Latin American caesarean section study (Latin American Centre for Perinatology, Université Libre de Bruxelles, European Community). This is an ongoing cluster randomised controlled trial in Argentina, Brazil, Cuba, Colombia, Guatemala, and Mexico testing whether obtaining a second opinion before a caesarean section reduces the rate. To participate in the trial, the hospitals had to provide data on caesarean section rates for 1996 and 1997, and we used data for Colombian and Cuban hospitals. Information for Panama's hospitals was provided by a collaborative study of the incidence and causes of caesarean section in hospitals of 18 Latin American countries.14 Finally, we performed a Medline search using the term “cesarean section/statistics and numerical data” or “cesarean section/trends” since 1990. Articles that reported incidence of caesarean section in Latin American countries at national, regional, or institutional level were selected. Reference lists of articles retrieved were also checked.

Total population and annual mean number of births were extracted from Pan American Health Organisation 1997 data.15 Gross national product per capita, proportion of institutional or skilled attendant deliveries, proportion of urban population, number of doctors per head, and maternal and infant mortality were extracted from 1998 data.16 Data about perinatal mortality were extracted from the Safe Motherhood website.17

Estimates of national caesarean section rates

We estimated the rates of caesarean section for all Latin American countries except Nicaragua, where recent figures were unavailable. National figures were obtained by different approaches according to the type and source of the retrieved data. Consequently, we formed three groups of countries: those where national figures were available through periodic surveillance (Chile, Costa Rica, Cuba, Ecuador, Guatemala, Uruguay, and Venezuela); those where national figures were available through special surveys (Bolivia, Colombia, Honduras, Haiti, Dominican Republic, and Peru); and those where national figures were not available and had to be estimated from institutional rates and proportion of institutional deliveries (Argentina, Brazil, El Salvador, Mexico, Panama, and Paraguay).

For Brazil, the total number of caesarean sections performed in one year was available and for Paraguay a probable estimate of the number of caesarean sections in one year. These figures were divided by the annual mean number of births to estimate national caesarean section rates. For Argentina and Mexico, only caesarean section rates for deliveries conducted in public and private sectors and the contributions of these sectors to the total hospital deliveries were available. These data were used to estimate the total number of caesarean sections in one year; the annual mean number of births was divided by this figure to give national caesarean section rates. For El Salvador and Panama, data were available only for public hospitals. National caesarean section rates were therefore estimated from caesarean section rates in public hospitals and the proportion of hospital deliveries. Sources and type of data and ways of estimating the national caesarean section rate (when applicable) for each country are available on the BMJ's website.

Estimates of excess caesarean sections

We adopted 15% as the highest acceptable limit for national caesarean section rates. This figure was proposed by the World Health Organisation in 1985 based on the caesarean section rates of some countries with the lowest perinatal mortality in the world.18 In 1991, the figure was adopted as a goal for the year 2000 by the United States Department of Health and Human Services.19 Estimations were made for each country, calculating the hypothetical number of caesarean sections if the rate was 15% and subtracting it from the actual number of caesarean sections.

Analysis of data

We calculated Spearman's rank correlation coefficient to measure the association between the countries' gross national product per capita, the number of doctors per 10 000 population, and the proportion of urban population and caesarean section rates. Since information about gross national product was not available, Cuba was not included in this analysis.

Results

Table 1 gives information about population, annual births, institutional deliveries, urban population, doctors per 10 000 population, mortality, and caesarean section rates of the countries. Seven countries had caesarean section rates below 15%. The range for the remaining 12 countries was 16.8% to 40.0%. These 12 countries represent 81% of the deliveries in the region. Information about rates of caesarean section in different types of hospitals were available for Argentina, Brazil, Chile, Colombia, Mexico, and Paraguay. In all of them, the proportion of caesarean section in women in private hospitals was much higher than that of women in public hospitals. Three countries had caesarean section rates over 50% in private hospitals (table 1). Countries with caesarean section rates below 15% also showed lower proportions of hospital deliveries or births assisted by skilled attendants (28% to 67%) than countries with caesarean section rates above 15% (59% to 100%).

Table 1.

Population, annual mean number of births, doctors per 10 000 population, urban population, institutional or skilled attendant deliveries, mortality, and caesarean section rates for Latin American countries

| Country | Population (1000s) 1997 | Annual mean No of births (1000s) 1995-2000 | No of doctors per 10 000 population 1997 | Urban population 1998 (%) | Institutional or skilled attendant deliveries 1996 (%) | Mortality

|

Caesarean section rates (%)

|

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Maternal, 1992-7 (per 100 000 live births) |

Perinatal, 1990-7 (per 1000 births) | Infant, 1997 (per 1000 live births) | National | Institutional or skilled attendant deliveries

|

Year* | |||||||||

| All hospitals | Public and social security hospitals | Private hospitals | ||||||||||||

| Haiti | 7 359 | 255 | 2.5 | 33.7 | 46 | 457 | 95 | 74 | 1.6 | — | 8.2 | — | 1995 | |

| Guatemala | 11 241 | 405 | 9.3 | 39.8 | 35 | 190 | 45 | 38 | 4.9 | — | — | — | 1997 | |

| Bolivia | 7 774 | 262 | 5.8 | 63.1 | 28 | 390 | 55 | 59 | 4.9 | 15.8 | — | — | 1994 1997 | |

| Peru | 24 367 | 613 | 10.3 | 72.0 | 56 | 265 | 35 | 43 | 8.7 | — | 12 | — | 1996, 1997 | |

| Paraguay | 5 088 | 162 | 4.9 | 54.6 | 36 | 123 | 40 | 36 | 8.7† | 20.7 | 17 | 41 | 1997 | |

| Honduras | 5 981 | 203 | 8.3 | 45.7 | 54 | 148 | 40 | 42 | 12.1 | — | — | — | 1996 | |

| El Salvador | 5 928 | 167 | 4.9 | 46.0 | 67 | 60 | 35 | 40 | 14.8† | 22.1 | 20-22.9 | — | 1996 | |

| Colombia | 37 068 | 873 | 9.3 | 74.0 | 96 | 87 | 25 | 24 | 16.8 | — | 32.5 | 58.6 | 1995, 1997 | |

| Panama | 2 722 | 62 | 12.1 | 56.9 | 89 | 84 | 25 | 16 | 18.2† | 20.5 | 20-21.1 | — | 1996 | |

| Ecuador | 11 937 | 309 | 13.2 | 61.0 | 59 | 159 | 45 | 39 | 18.5 | 26.3 | 18.5 | — | 1996 | |

| Costa Rica | 3 575 | 87 | 14.1 | 50.9 | 97 | 29 | 20 | 12 | 20.8 | 20.8 | 20.8 | — | 1993 | |

| Venezuela | 22 777 | 572 | 24.2 | 86.8 | 95 | 56 | 25 | 22 | 21.0 | 21.0 | — | — | 1995 | |

| Uruguay | 3 221 | 54 | 37.0 | 90.9 | 99 | 19 | 25 | 17 | 21.9 | 21.9 | — | — | 1996 | |

| Cuba | 11 068 | 145 | 53.0 | 77.1 | 100 | 33 | 15 | 8 | 23.0 | 23.0 | 27.4 | — | 1997 | |

| Mexico | 94 281 | 2338 | 15.6 | 74.0 | 84 | 48 | 40 | 23 | 24.1† | 31.3 | 27.4 | 51.8 | 1996, 1995 | |

| Argentina | 35 671 | 714 | 26.8 | 88.9 | 95 | 44 | 30 | 21 | 25.4† | 25.4 | 15.4-20.9 | 35.8-45 | 1996, 1997 | |

| Dominican Republic | 8 097 | 197 | 10.2 | 63.9 | 95 | 110 | 35 | 45 | 25.9 | 25.9 | — | — | 1996 | |

| Brazil | 163 032 | 3210 | 12.7 | 80.1 | 92 | 114 | 45 | 40 | 27.1† | 32.0 | 20.2 | 35.9 | 1996, 1994 | |

| Chile | 14 625 | 292 | 11.0 | 84.3 | 100 | 25 | 15 | 13 | 40.0 | 40 | 28.8 | 59 | 1997, 1994 | |

When two years are given, the first one corresponds to the national rate and the second one to institutional rates.

Estimated rates based on institutional rates and % of institutional deliveries.

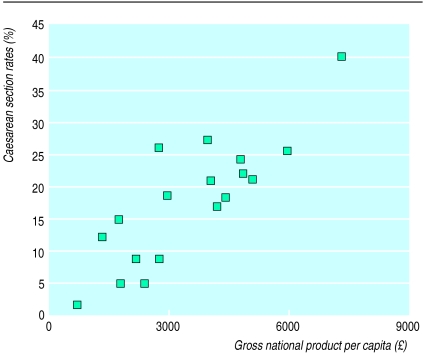

A positive and significant correlation was observed between rates of caesarean section and the gross national product per capita (rs=0.746, n=18, P<0.0001; figure), the proportion of urban population (rs=0.730, n=19, P<0.0001), and the number of doctors per 10 000 population (rs=0.690, n=19, P=0.001). All but one of the countries with gross national product per capita below £2800 showed caesarean section rates below 15%, while all but one of the countries with gross national product per capita above £2800 had caesarean section rates above 15%. The exception is Dominican Republic, with a gross national product per capita of £2740 and a caesarean section rate of 25.9%.

In the 12 countries with caesarean section figures above 15%, around 2.2 million caesarean sections were performed each year. Taking 15% as the medically justified rate, we calculate that around 850 000 unnecessary caesarean sections were performed each year in the region (table 2).

Table 2.

Estimated annual number of caesarean sections and annual number of caesarean sections above 15% upper limit suggested by WHO for Latin American countries

| Countries | Rate of caesarean section (%) | Annual No of caesarean sections* | Annual No above 15% maximum |

|---|---|---|---|

| Colombia | 16.8 | 146 664 | 15 714 |

| Panama | 18.2 | 11 284 | 1 984 |

| Ecuador | 18.5 | 57 165 | 10 815 |

| Costa Rica | 20.8 | 18 096 | 5 046 |

| Venezuela | 21.0 | 120 120 | 34 320 |

| Uruguay | 21.9 | 11 826 | 3 726 |

| Cuba | 23.0 | 33 350 | 11 600 |

| Mexico | 24.1 | 561 120 | 212 752 |

| Argentina | 25.4 | 181 356 | 74 256 |

| Dominican Republic | 25.9 | 51 023 | 21 473 |

| Brazil | 27.1 | 869 910 | 388 410 |

| Chile | 40.0 | 116 800 | 73 000 |

| Total | 2 178 714 | 853 096 |

Based on annual mean number of births 1995-2000.

Discussion

We had difficulty estimating national rates of caesarean section as national figures were often not available and had to be calculated from different sources of data. Therefore, figures for some of the most populated Latin American countries (such as Brazil, Mexico, and Argentina) cannot be regarded as totally accurate but are the best possible estimates.

For these estimations, we adopted the most conservative approach. We assumed that all non-hospital deliveries were vaginal deliveries and included them in the denominator. When data from the private sector were missing, the national caesarean section rates were based on public hospitals rates, which are generally lower than rates in private hospitals. When multiple sources of caesarean section figures were available for one country (as in Argentina), the lowest figures were used to estimate the national rate.

In the countries where the national caesarean section rates had to be estimated from data from different institutions, estimates are inevitably inaccurate and subject to wide variability. The variability of the estimates calculated from multiple sources (Argentina) or sources with wide coverage (Brazil) was probably smaller than the variability of estimates calculated from only one source (Paraguay) or sources with less coverage.

Relation with socioeconomic indicators

We found a clear positive association between socioeconomic indicators and the proportion of caesarean sections, a finding that has been described in previously.1,6,20 Strong associations were found between the proportion of caesarean sections and the gross national product per capita, the number of doctors per 10 000 population, the proportion of urban population, and the proportion of institutional deliveries. Moreover, in all countries for which the information was available, the proportion of caesarean sections in private hospitals was higher than that in public or social security hospitals. Although higher caesarean section rates are positively related to higher income and social class, women with low income are at high obstetric risk. Women assisted in public hospitals are more likely to be single, less educated, adolescent, and to have a poorer history than women attending private hospitals.21 No medical justification exists for the finding that women with low obstetric risk, and presumably least likely to benefit from a caesarean section, had higher caesarean section rates.

When considering the implications of our findings the limitations of the ecological design must be remembered. In this type of study, the validity of the inferences depends on the ability to control for differences among countries in the joint distribution of confounders, including individual level variables.22 These data were not available for most countries. Despite the possible confounding effect of factors that were not controlled for, the associations we found suggest the need for further investigation into which factors related to the doctors' and women's decision making processes influence caesarean section rates.

Limiting caesarean sections

Using the limit of 15% set arbitrarily by the WHO in 1985 but still accepted by the scientific community,19 we calculated an excess of over 850 000 caesarean sections a year for Latin America. This figure represents an unnecessary increased risk for women and their babies. From the economic perspective, it is a burden to health systems that work with limited budgets. On the other hand, the low proportions of caesarean section observed in countries like Haiti, Guatemala, and Bolivia probably represent lack of appropriate medical care rather than ideal health care.

Although the epidemic of caesarean section in Latin America is not new,6 little action is taking place to reduce its use. This is partly because caesarean section is now culturally accepted as a normal way of giving birth.23 To be effective, actions to reduce caesarean section would need to involve public health authorities, medical associations, medical schools, doctors, midwives, nurses, the media, and the general population. Scientifically tested medical approaches to decrease caesarean section rates at hospital level are also much needed. A multicentre intervention study investigating the effect of obtaining a second medical opinion whenever a caesarean section is indicated is under way in six countries in the region and may indicate new ways to prevent the overuse of this potentially dangerous surgical procedure.

Figure.

Correlation between the gross national product per capita (£) and caesarean section rates in 18 Latin American countries (rs=0.746)

Acknowledgments

We thank all focal points of the health promotion and protection division and all country representatives of the Pan American Health Organisation for sending information about caesarean section rates. We also thank Arachu Castro for providing useful information.

Footnotes

Funding: Latin American Centre for Perinatology, Pan American Health Organisation, World Health Organisation.

Competing interests: None declared.

References

- 1.Shearer E. Cesarean section: medical benefits and costs. Soc Sci Med. 1993;37:1223–1231. doi: 10.1016/0277-9536(93)90334-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.National Institute of Child Health and Human Development. Cesarean childbirth. Report of a consensus Development Conference. Bethesda, MD: NIH; 1981. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wolfe S. Unnecessary cesarean sections: curing a national epidemic. Public Citizen Health Research Group. 1994;10:1–7. [Google Scholar]

- 4.What is the right number of caesarean sections? Lancet. 1997;349:815. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(97)21012-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Faúndes A, Cecatti JG. Which policy for caesarean sections in Brazil? An analysis of trends and consequences. Health Policy Plan. 1993;8:33–42. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Barros FC, Vaughan JP, Victora CG, Huttly SRA. Epidemic of caesarean sections in Brazil. Lancet. 1991;338:167–169. doi: 10.1016/0140-6736(91)90149-j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Murray SF, Serani Pradenas F. Cesarean birth trends in Chile, 1986 to 1994. Birth. 1997;24:258–263. doi: 10.1111/j.1523-536x.1997.tb00600.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Flamm BL, Berwick DM, Kabcenell A. Reducing cesarean section rates safely: lessons from a “breakthrough series” collaborative. Birth. 1998;25:117–124. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-536x.1998.00117.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Notzon FC, Cnattingius S, Bergsjö P, Cole S, Taffel S, Irgens L, et al. Cesarean section delivery in the 1980s: international comparison by indication. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1994;170:495–504. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9378(94)70217-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Rates of cesarean delivery—United States, 1993. MMWR. 1995;44:303–307. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wilkinson C, McIlwaine G, Boulton-Jones C, Cole S. Is a rising caesarean section rate inevitable? Br J Obstet Gynaecol. 1998;105:45–52. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0528.1998.tb09349.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ballacci F, Medda E, Pinnelli A, Spinelli A. Cesarean delivery in Italy: a European record. Epidemiol Prev. 1996;20:105–106. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Macro International. Demographic health surveys. measure DHS+ www.macroint.com/dhs. (Accessed 16 December, 1998.)

- 14.Belitzky R. El nacimiento por cesárea en instituciones latinoamericanas. Montevideo: Centro Latinoamericano de Perinatología y Desarrollo Humano (Pan American Health Organisation); 1988. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pan American Health Organisation. Health situation in the Americas. Basic indicators 1997. Washington, DC: PAHO; 1997. (PAHO/HDP/HDA/97.02.) [Google Scholar]

- 16.Pan American Health Organisation. Health situation in the Americas. Basic indicators 1998. Epidemiol Bull. 1998;19:10–11. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Safe Motherhood. Maternal health around the world. Facts and figures. safemotherhood.org/init_facts.htm. (Accessed 9 June 1999.)

- 18.World Health Organisation. Appropriate technology for birth. Lancet. 1985;ii:436–437. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.US Department of Health and Human Services, Public Health Service. Healthy people 2000: national health promotion and disease prevention objectives. Washington, DC: DHHS; 1991. (PHS 91-50212.) [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gould JB, Davey B, Stafford RS. Socioeconomic differences in rates of cesarean section. N Engl J Med. 1989;321:233–239. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198907273210406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Belizán JM, Farnot U, Carroli G, Al-Mazrou Y. Antenatal care in developing countries. Paediatr Perinat Epidemiol. 1998;12(suppl 2):1–3. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-3016.12.s2.4.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Morgenstern H. Ecologic studies. In: Rothman KJ, Greenland S, editors. Modern epidemiology. Philadelphia: Lippincott-Raven; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 23.De Mello E, Souza C. C-sections as ideal births: the cultural constructions of beneficence and patients' rights in Brazil. Camb Q Health Ethics. 1994;3:358–366. doi: 10.1017/s096318010000517x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]