Abstract

We have reported previously that there appears to be an intriguing sex-related functional asymmetry of the prefrontal cortices, especially the ventromedial sector, in regard to social conduct, emotional processing, and decision-making, whereby the right-sided sector is important in men but not women and the left-sided sector is important in women but not men. The amygdala is another structure that has been widely implicated in emotion processing and social decision-making, and the question arises as to whether the amygdala, in a manner akin to what has been observed for the prefrontal cortex, might have sex-related functional asymmetry in regard to social and emotional functions. A preliminary test of this question was carried out in the current study, where we used a case-matched lesion approach and contrasted a pair of men cases and a pair of women cases, where in each pair one patient had left amygdala damage and the other had right amygdala damage. We investigated the domains of social conduct, emotional processing and personality, and decision-making. The results provide support for the notion that there is sex-related functional asymmetry of the amygdala in regard to these functions— in the men pair, the patient with right-sided amygdala damage was impaired in these functions, and the patient with left-sided amygdala damage was not, whereas in the women pair, the opposite pattern obtained, with the left-sided woman being impaired and the right-sided woman being unimpaired. These data provide preliminary support for the notion that sex-related functional asymmetry of the amygdala may entail functions such as social conduct, emotional processing, and decision-making, a finding that in turn could reflect (as either a cause or effect) differences in the manner in which men and women apprehend, process, and execute emotion-related information.

INTRODUCTION

We recently presented evidence that there is a sex-related functional asymmetry in the manner in which the prefrontal cortex, and especially the ventromedial prefrontal sector (VMPC), subserves functions such as social conduct, emotional processing, and complex decision-making. Specifically, using a neuropsychological approach, we found that the right-hemisphere VMPC sector seems to be critical for such functions in men but not women, whereas the left-hemisphere VMPC sector seems to be critical for such functions in women but not men (Tranel et al., 2005). There are several sources of evidence that the amygdala, an emotion-related structure that is tightly interconnected with the VMPC, might also evince sex-related functional asymmetry vis-à-vis functions such as social/emotional processing and complex decision-making, and this proposition is the focus of the current report.

The amygdala has historically been strongly implicated in the neurobiology of emotion (Gallagher & Chibe, 1996; Kluver & Bucy, 1939; Meunier et al., 1999; Weiskrantz, 1956; Zola-Morgan et al., 1991), and an extensive corpus of research has established the amygdala as being critical for a variety of social and emotion-related processes. For example, the amygdala is important for the detection and recognition of emotional facial expressions (e.g., Adolphs, 2002, 2003; Anderson et al., 2003; Vuilleumier et al., 2001), for the processing of social information more generally (e.g., Hariri et al., 2002; Norris et al., 2004), and for the enhancement of memory by emotion (Buchanan & Adolphs, 2004; Buchanan et al., 2006; LaBar & Cabeza, 2006; LaBar & Phelps, 1998; McGaugh et al., 1996; Phelps, 2004).

There is also evidence that the amygdala is involved in decision-making. For example, Bechara et al. (1999) found that patients with bilateral amygdala damage had impaired performance on the Iowa Gambling Task, a complex laboratory decision-making task in which emotional processing plays a significant role. Other evidence has suggested that the amygdala is also important for certain aspects of social and emotional intelligence, as measured by the Emotional Quotient Inventory (Bar-On et al., 2003). It has also been shown that even unilateral amygdala damage can interfere with specific aspects of risky decision-making (Weller et al., in press), as measured by a risky decision-making task known as the “Cups” task (Levin & Hart, 2003). However, none of these studies addressed the issue of gender and brain asymmetry, as the relatively small number of cases in these studies precluded such investigations. It is important to note that the underlying mechanisms responsible for the observed decision-making deficits related to amygdala versus VMPC damage do not seem identical. We have suggested that the amygdala triggers non-conscious, automatic, involuntary, and obligatory affective (emotional) signals that are necessary for the functional “awakening” of the VMPC during decision-making, whereas the VMPC plays a role in the subsequent conscious deliberation and evaluation of options during decision-making (Weller et al., in press). Furthermore, preliminary evidence suggests that while the amygdala role is a necessary a priori step for the normal functional development of the VMPC, the VMPC can operate without an amygdala, if the amygdala-mediated signals had been previously experienced and encoded prior to the damage (Bechara et al., 2003). Perhaps at the process level, the amygdala is akin to the hippocampus with regard to affective (emotional) experiences, i.e., necessary for acquiring new emotional attributes (anterograde emotions), but not the retrieval of old emotional attributes (retrograde emotions).

As far as sex-related functional asymmetry of the amygdala is concerned, there is already some evidence that this might be the case for some functions. Take for instance the role of the amygdala in the process of enhancement of memory by emotion. It has been shown that amygdala activation during the encoding of emotionally arousing material correlates with subsequent memory for the material (e.g., Cahill et al., 1996; Canli et al., 1999, 2000; Hamann et al., 1999), and in men, this relationship is most robust for the right amygdala, whereas in women, the relationship is most robust for the left amygdala (Cahill et al., 2001, 2004; Canli & Gabrieli, 2004; Canli et al., 2002; Mackiewicz et al., 2006). Cahill (2003, 2006) has interpreted these findings to suggest that emotional arousal enhances memory in men via activation of the right amygdala, whereas emotional arousal enhances memory in women via activation of the left amygdala. Intriguingly, the basic story line in this evidence is compatible with the evidence for sex-related functional asymmetry of the VMPC—specifically, there is a right-sided predominance in men and a left-sided predominance in women.

The amygdala and VMPC systems are well connected anatomically (Bachevalier, 2000; Öngür & Price, 2000; Pitkänen, 2000), and the amygdala and orbital prefrontal cortex, in particular, have rich anatomical interconnections (Amaral et al., 1992; Carmichael & Price, 1995; Porrino et al., 1981). The amygdala and VMPC comprise two key anatomical substrates for social behavior, emotional processing, and complex decision-making. This invites the question as to whether sex-related functional asymmetry of the amygdala might be present for functions such as social/emotional processing and decision-making. The current study provides some preliminary evidence in this regard. Building on the background presented above, we tested the hypothesis that there is sex-related functional asymmetry of the amygdala in regard to social conduct, emotional processing, and decision-making, whereby the right amygdala is critical in men but not in women, and the left amygdala is critical in women but not in men. Accordingly, we predicted that: (a) Unilateral damage to the right amygdala will be associated with defects in social conduct, emotional processing, and decision-making in men but not in women. (b) Unilateral damage to the left amygdala will be associated with the opposite outcome, i.e., defects in women but not in men.

METHOD

Participants

The participants were four patients with unilateral amygdala damage caused by anterior temporal lobectomy for pharmacoresistant epilepsy. Two of the patients were men, one with a left amygdala lesion and one with a right amygdala lesion, and two of the patients were women, one with a left amygdala lesion and one with a right amygdale lesion. The four patients were drawn from the Patient Registry of the Division of Behavioral Neurology and Cognitive Neuroscience at the University of Iowa. Under the auspices of their enrollment in the Registry, the patients have been fully characterized neuroanatomically and neuropsychologically, according to standard protocols in our laboratory (Frank et al., 1997; Tranel, 2008). The participants completed the experimental procedures described below in the chronic epoch of recovery (see below), and a sufficient amount of time had passed since lesion onset to allow for changes in social and emotional processing to become manifest.

Focal unilateral amygdala damage is rare, and as a first approach to the predictions above, we utilized patients with anterior temporal lobe damage caused by surgical treatment for pharmacoresistant epilepsy. In the standard anterior temporal lobectomy (ATL) procedure at our institution (see Yucus & Tranel, in press, for additional details), the neurosurgeon initiates a corticectomy in the middle temporal gyrus, and carries the resection inferiorly to include the inferior temporal gyrus and anteriorly to include the temporal pole. The resection is then carried mesially until the collateral sulcus and temporal horn of the lateral ventricle are encountered. The resection is then carried more mesially to include variable extents of the amygdala and hippocampus. For the purposes of the current study, the ATL patients have the anatomical caveats that (1) the lesion is not restricted to the amygdala, and (2) amygdale damage may not affect the entire amygdala structure. With these cautions in mind, we attempted to carefully select a pair of men patients with left or right amygdala damage caused by ATL, and a pair of women patients with left or right amygdala damage caused by ATL, to investigate the predictions articulated above. Based on the neurosurgical operative reports and on post-operative structural MRI scans, we determined that all of the patients had at least partial structural damage to the amygdala on one side (and it is likely that the functional integrity of the affected amygdala is compromised even more extensively than the structural damage might imply, given that tissue in the surround of the amygdala—especially the parahippocampal gyrus—is often included in the surgical resection).

Experimental Measurement

In addition to basic neuropsychological assessment, the patients were measured in three domains of functioning: social conduct, emotional processing and personality, and decision-making. The specific instruments and methods used to measure aspects of each area are described briefly below. The approach is the same as that used previously for similar assessment of VMPC patients (Tranel et al., 2002, 2005).

Social conduct

For the domain of social conduct, we included measurements of social status, employment status, and interpersonal functioning, with the goal being to determine whether the patient had experienced a post-lesion change in overall social functioning. Structured rating scales were completed by clinical neuropsychologists who were naïve as to the purposes of the current study. These ratings, along with information obtained from family members and close friends of the patient, were used to quantify changes in social conduct in each patient. Specifically, for Social Status, change was defined as an alteration in the patient’s financial security or in peers’ judgment of the patient’s social attainment. For Employment Status, change was defined as an alteration in the patient’s procurement or level of occupation (e.g., inability to sustain gainful employment). For Interpersonal Functioning, change was defined as an alteration in the patient’s ability to sustain normal social relationships with significant others, family, and friends.

Emotional processing and personality

To quantify emotional processing and personality, we utilized the Beck Depression Inventory-II (BDI-II), Beck Anxiety Inventory (BAI), Minnesota Multiphasic Personality Inventory-2 (MMPI-2), and Iowa Rating Scales of Personality Change (Iowa Rating Scales). The BDI-II, BAI, and MMPI-2 are standard clinical measures for mood, psychopathology, and personality. The Iowa Rating Scales provide a quantitative measurement of changes in emotional functioning, mood, and personality that can occur as a consequence of brain injury. The Iowa Rating Scales are completed by a collateral, namely, a person who has had extensive contact with the patient both before and after their brain damage (e.g., spouse, parent). The collateral rates the patient on aspects of emotional functioning, behavioral control, social and interpersonal behavior, real-world decision-making, and insight. For each of these characteristics, the collateral rates the current level of the characteristic, and the degree to which the characteristic has changed from before to after the patient’s brain damage. This information is then used to assess whether the patient has evidence of acquired personality problems, including the following specific manifestations: (1) general dampening of emotional experience; (2) poorly modulated emotional reactions; (3) disturbances in social decision-making; (4) disturbances in goal-directed behavior; (5) lack of insight into the post-morbid changes. (More detailed information on this scoring system is provided in Anderson et al. (2006); Barrash et al. (2000); and Tranel et al. (2007).) A clinical neuropsychologist naïve to the objectives of this study rated each patient on the severity of acquired personality changes, using a 1-2-3 scale where 1 = mild, 2 = moderate, and 3 = severe.

Decision-making

The Iowa Gambling Task (IGT; Bechara et al., 1994) was used to measure complex decision-making. The IGT was designed to factor in reward, punishment, and uncertainty, so as to provide an analog to complex real-world decision-making, and it has been extensively researched in this regard (e.g., Bechara et al., 2000). Briefly, the IGT has four decks of cards, some of which are “advantageous” because they lead to winning (money) in the long run, and some of which are “disadvantageous” because they lead to losing in the long run. For the current study, we obtained behavioral data (the number of card picks from the “advantageous” and “disadvantageous” decks) and psychophysiological data (anticipatory skin conductance responses (SCRs) generated immediately before each card selection, during the time the participant is deciding which deck to choose from). These data were used to classify the IGT performance of each participant as “impaired” or “normal,” following previous methods (Bechara et al., 2000; Tranel et al., 2005). Specifically, impaired meant that the participant (i) selected significantly more cards from disadvantageous decks than from advantageous ones, and (ii) failed to generate anticipatory SCRs to the disadvantageous decks; normal meant that the participant (i) selected significantly more cards from advantageous decks than from disadvantageous ones, and (ii) generated anticipatory SCRs to the disadvantageous decks. Performance on the IGT was further quantified by calculating for each patient a summary score, specifically, the number of cards picked from the advantageous decks minus the number of cards picked from the disadvantageous decks. In this calculation, a positive net outcome indicates more advantageous selections, and a negative net outcome indicates more disadvantageous selections).

Neuroanatomical Data Quantification and Analysis

The patients had undergone anterior temporal lobectomies, which yielded some degree of damage to the amygdala on one side. We utilized the neurosurgical operative reports to ascertain whether the amygdala had been included in the resection (it was in all four patients). Also, the four patients had post-operative magnetic resonance (MR) scans obtained in a 1.5 Tesla General Electric scanner or a 3.0 Tesla Siemens scanner with an SPg sequence, in thin (1.5 mm) contiguous T1 weighted coronal slices. The lesions evident in these structural studies were inspected to determine extent of amygdale damage.

RESULTS

Demographical and Neuropsychological Variables

Demographic data for the case pairs are presented in Table 1. The pairs were well-matched on most of the parameters. The patients are all middle-aged (at time of testing), high-school educated or slightly higher, and fully right-handed. According to standard demarcations used in epilepsy research (e.g., Saykin et al., 1989; Stafiniak et al., 1990), none of the patients had “early onset” epilepsy (where issues of functional reorganization tend to be more salient, e.g., Griffin & Tranel, 2007), and 3 of the 4 cases had seizure onset in adolescence or early adulthood. All of the patients were two or more years post-lesion onset at the time of the current experimental procedures, and thus were in the chronic phase of recovery where the neuropsychological and neuroanatomical profiles are stable.

Table 1.

Demographic Data for the Case-Matched Pairs

| Participant | Sex | Lesion Side | Age at testing | Age at seizure onset | Education (years) | Handedness1 | Chronicity2 (years) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2250 | Male | Left | 48 | 14 | 12 | +100 | 7 |

| 2713 | Male | Right | 52 | 7 | 14 | +100 | 6 |

| 3310 | Female | Left | 51 | 22 | 12 | +100 | 2 |

| 2897 | Female | Right | 51 | 19 | 12 | +100 | 5 |

Handedness was assessed with the modified Geschwind-Oldfield Handedness Questionnaire, which yields quotients ranging from full right-handedness (+100) to full left-handedness (−100).

Chronicity is the time between lesion onset (lobectomy) and participation in the current experimental procedures.

Neuropsychological data are summarized in Table 2. The Table presents data for basic cognitive domains such as intellect (Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale-III), memory (Auditory-Verbal Learning Test, Visual Retention Test), language (Token Test, Controlled Oral Word Association, Boston Naming Test), perception (Facial Discrimination Test), and decision-making (Wisconsin Card Sorting Test). The patients were well matched in terms of general intellectual functioning, and all had Full Scale IQ scores in the average range. Detailed reviews of the neuropsychological profiles of the various patients are presented in the case summaries below; here, the main point to make is that the case pairs did not have major cognitive differences that would confound interpretation of the experimental measures of social conduct, emotional/personality functioning, and complex decision-making.

Table 2.

Neuropsychological Data for the Case-Matched Pairs

| INDEX/TEST | 2250 (M/L) | 2713 (M/R) | 3310 (F/L) | 2897 (F/R) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| WAIS-III VIQ | 89 | 96 | 93 | 100 |

| WAIS-III PIQ | 104 | 102 | 94 | 84 |

| WAIS-III FSIQ | 95 | 99 | 94 | 93 |

| AVLT: Trial 5 | 11 | 14 | 6 | 9 |

| AVLT: 30-minute recall | 6 | 10 | 5 | 7 |

| AVLT: 30-minute recognition | 26 | 29 | 26 | 28 |

| Visual Retention Test: Correct | 9 | 8 | 7 | 6 |

| Visual Retention Test: Errors | 2 | 4 | 6 | 10 |

| Token Test | 44 | 44 | 38 | 44 |

| COWA | 42 | 53 | 21 | 40 |

| Boston Naming Test | 50 | 55 | 43 | 54 |

| Facial Discrimination | 47 | 47 | 50 | 39 |

| WCST: Perseverative Errors | 5 | 12 | 28 | 7 |

| WCST: Failure to Maintain Set | 0 | 2 | 4 | 0 |

| WCST: Categories Completed | 6 | 4 | 2 | 6 |

WAIS-III VIQ = Verbal IQ; WAIS-III PIQ = Performance IQ; WAIS-III FSIQ = Full Scale IQ (all from the Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale-III). AVLT is the Auditory-Verbal Learning Test, a 15-item word list learning test. Raw scores are presented, with Trial 5 = #/15, 30-minute recall = #/15, and 30-minute recognition = #/30. The Visual Retention Test requires reproduction of geometric designs from memory; raw scores for # correct (10 maximum) and # errors (no maximum) are presented. The Token Test, from the Multilingual Aphasia Examination, is a measure of aural comprehension; raw scores (44 maximum) are presented. COWA is the Controlled Oral Word Association test, a measure of word generation to letters (raw scores are presented). The Boston Naming Test is a 60-item test of visual confrontation naming (raw scores are presented). Facial Discrimination is the Facial Recognition Test of Benton et al. (1983), and is a measure of visuoperceptual discrimination and matching of unfamiliar faces (raw scores are presented; the maximum is 54). WCST is the Wisconsin Card Sorting Test, a conventional neuropsychological measure of reasoning and decision-making; scores for the number of perseverative errors (no limit), number of failures to maintain set (no limit), and number of categories completed (maximum = 6) are presented. Scores that are below expectations are bolded.

Social Conduct, Emotional Processing, and Decision-Making

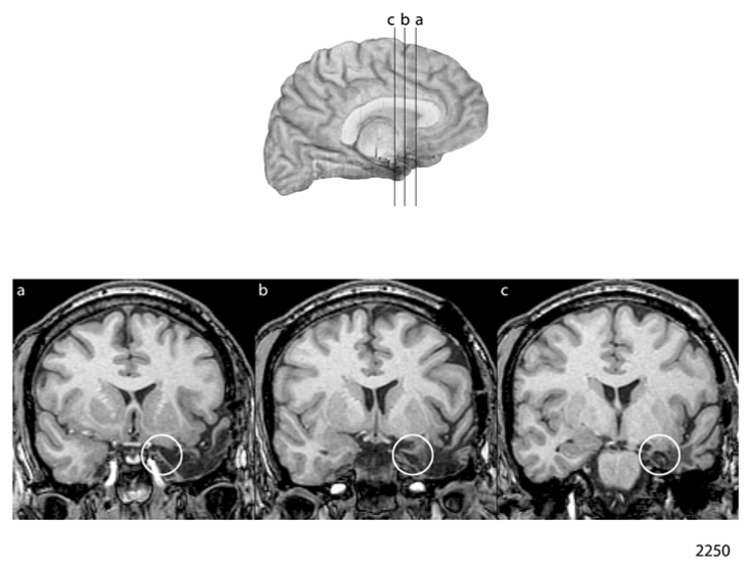

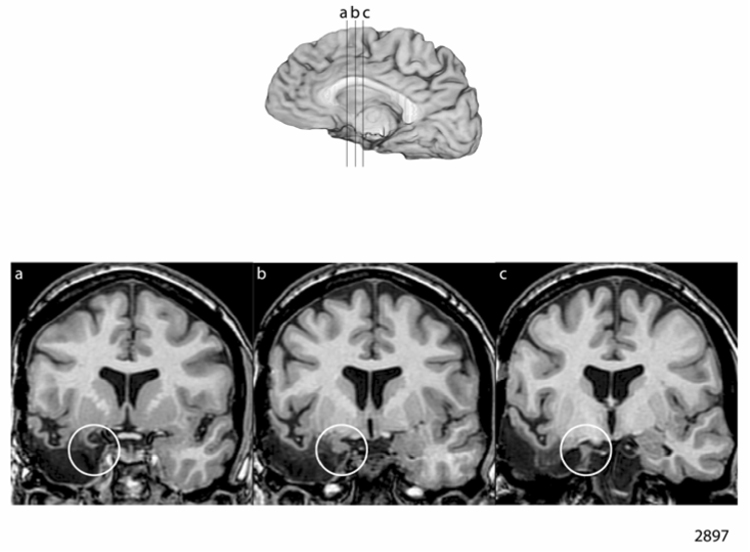

Data for the four participants for the outcomes regarding social conduct, emotional functioning and personality, and complex decision-making, are provided in Table 3 and Table 4. The results and case comparisons are presented descriptively, commensurate with the nature of the measurements (statistical tests were not applied, due to the nature of the measurements and the small number of participants). Lesion information is presented in Figure 1 and Figure 2.

Table 3.

Social Conduct

| Participant (Sex/Hemisphere) | Social Status | Employment Status | Interpersonal Functioning | Overall Change (magnitude) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2250 (M/L) | 1 | 1 | 1 | No |

| 2713 (M/R) | 3 | 3 | 3 | Yes (severe) |

| 3310 (F/L) | 3 | 3 | 3 | Yes (severe) |

| 2897 (F/R) | 1 | 1 | 1 | No |

The extent of change or impairment in aspects of social conduct was rated on a three-point scale, with 1 = no change or impairment, 2 = moderate change or impairment, 3 = severe change or impairment. Overall Change was based on the overall impression derived from the three domains of Social Status, Employment Status, and Interpersonal Functioning, as judged by a clinical neuropsychologist who was naïve as to the hypotheses of the current study.

Table 4.

Emotional Functioning, Personality, and the Iowa Gambling Task

| Participant (Sex/Hemisphere) | BDI-II1 | BAI2 | MMPI-23 | Acquired Personality Problems4 | Iowa Gambling Task5 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2250 (M/L) | 8 | 2 | 0(74)-2(70) | No | Normal (+36) |

| 2713 (M/R) | 10 | 3 | (none; L = 74) | Yes (3) | Impaired (−18) |

| 3310 (F/L) | 30 | 42 | 8(97)-7(84)-2(83) | Yes (3) | Impaired (−8) |

| 2897 (F/R) | 0 | 0 | 2(79)-7(73)-6(70) | No | Normal (+22) |

BDI-II = Beck Depression Inventory-II. Raw scores are provided, and scores greater than 10 indicate significant depressive symptomatology.

BAI = Beck Anxiety Inventory. Raw scores are provided, and scores greater than 10 indicate significant anxiety symptomatology.

MMPI-2 = Minnesota Multiphasic Personality Inventory-2. Clinical scales with significant elevations (i.e., T-scores above 65) are indicated, with the T-scores in parentheses (the highest three significant elevations are presented).

Acquired Personality Problems refer to whether or not the participant had acquired problems in personality functioning, as derived from data on the Iowa Rating Scales of Personality Change. The numbers in parentheses denote degree of severity, where 1 = mild, 2 = moderate, and 3 = severe.

Performance on the Iowa Gambling Task was classified as normal or impaired using standard criteria. The numbers in parentheses denote the actual level of performance (advantageous choices minus disadvantageous choices), and positive numbers indicate good performance and negative numbers indicate bad performance.

Figure 1.

Figure 1a and 1b: Neuroanatomical Results in the Men Case-Matched Pair

a. Lesion depiction in case 2250, man with left-sided amygdala damage

b. Lesion depiction in case 2713, man with right-sided amygdala damage

Figure 2.

Figure 2a and 2b: Neuroanatomical Results in the Women Case-Matched Pair

a. Lesion depiction in case 3310, woman with left-sided amygdala damage

b. Lesion depiction in case 2897, woman with right-sided amygdala damage

Overall, the data in Table 3 regarding Social Conduct indicate that in the men pair, the left-sided case (2250) did not develop significant changes in social status, employment status, or interpersonal functioning, whereas the right-sided case (2713) evidenced severe changes and impairments in these domains. In the women pair, the left-sided case (3310) had severe changes and impairments in social status, employment status, and interpersonal functioning, whereas the right-sided case (2897) did not evidence such changes or impairments. The same general pattern was evident for the outcomes on emotional functioning, personality, and complex decision-making (the Iowa Gambling Task) reported in Table 4. Specifically, in the men pair, the left-sided case (2250) did not develop major changes or impairments in these domains, whereas the right-sided case (2713) did show significant changes and impairments. In the women pair, the left-sided case (3310) developed severe changes and impairments in emotional functioning, personality, and complex decision-making, but the right-sided case (2897) did not.

We turn now to a brief case description for each of the four patients, to supplement the data in Table 3 and Table 4 and give a more complete flavor of the post-lesion status of the patients in the key domains of social conduct, emotional processing and personality, and complex decision-making.

Case Descriptions

Man with left amygdala damage (case 2250)

This patient is a 48-year-old, fully right-handed man who completed a high school education and then worked as a farmer. He developed medically-intractable epilepsy at age 14, and eventually underwent a left anterior temporal lobectomy at age 37 (at another institution), which included resection of the amygdala and part of hippocampus (per the operative report). However, he continued to have seizures following the operation, and at age 41 he underwent a second operation at our institution in which additional left medial temporal structures were removed, including more of the hippocampus. Following this operation, his seizures completely ceased, and he has been able to taper off all anticonvulsant medication. He has never smoked or abused alcohol or drugs. He had no premorbid history of treatment for depression, anxiety, or other psychological maladies.

We have evaluated the patient extensively since his second operation, and he returns to the laboratory on a regular basis to participate in our experiments. He has a mild, stable defect in verbal memory, and a defect in word retrieval for proper names, but virtually no other impairments in cognitive or behavioral functioning. He did report a mild “sense of depression” immediately following the second surgery, but this was transient and did not develop into a significant problem. He remains employed in the same capacity as before the surgeries, as a farmer, and has maintained normal performance in this occupation. In our evaluations, the patient has been cooperative, cheerful, and free of notable behavioral or emotional manifestations. He has presented on a few occasions with mild depression, invariably situational in nature (e.g., related to long hours of work due to seasonal demands, such as during the calving season), and he complains on occasion of being “lonely,” but he is generally cheerful and upbeat. He has never required antidepressant medication or counseling. His neuropsychological test performance (Table 2) is notable for a mild verbal memory defect. He does not have any major defects in speech or language, although he does have a mild word retrieval defect (slightly impaired performance on the Boston Naming Test). He has impaired naming of famous faces and landmarks (impaired proper naming), consistent with left anterior temporal damage (cf. Yucus & Tranel, in press). He performed very well (at ceiling) on the Wisconsin Card Sorting Test. He does typically report some ongoing unhappiness associated with his cognitive weaknesses, more specifically, frustration with his inability to “hang on to” new verbal information.

In terms of the other measurements relevant to the current study, the patient was rated on the Social Conduct domain (Table 3) as having “no change,” and more specifically, he does not have postmorbid changes in social status, employment status, or interpersonal functioning. As noted, his occupational status as a farmer has remained constant. He maintains the same (small) circle of friends and social activities that he enjoyed prior to his surgeries. In the emotional realm, the patient did not score in the clinical range on either the Beck Depression Inventory-II or the Beck Anxiety Inventory. He did produce a mildly elevated MMPI-2 profile, with clinical elevations on the social introversion and depression scales, but the elevations were only slightly above the normal range. There is no evidence of acquired personality problems, and on the Iowa Rating Scales of Personality change, a long-time friend rated him as not significantly changed on all characteristics. The patient produced an excellent performance on the Iowa Gambling Task. His overall net score was highly positive (+36), indicating a strong preference for the advantageous decks, and during the latter 3 trial blocks (trials 41 through 100) he picked almost exclusively from the advantageous decks. Also, he showed normal anticipatory skin conductance responses to the disadvantageous decks during the game.

The amygdala lesion for 2250 is depicted in Figure 1a. It can be seen that the amygdala is partially destroyed on the left, and the little remaining amygdala tissue does not appear to have any meaningful connectivity judging from the adjacent damage to the parahippocampal gyrus. This outcome is consistent with the surgical reports, and in particular, the report from the first surgery (from the Mayo Clinic) that indicated that the amygdala was removed.

To summarize, this man with left amygdala damage had no significant impairments in social conduct, emotional processing and personality, or complex decision-making.

Man with right amygdala damage (case 2713)

This patient is a 52-year-old, fully right-handed man who completed high school and then two years of community college. He worked for many years as a drill sergeant in the Army, and was promoted to administrative work within his unit. He then worked as an independent contractor. He had a long, stable marriage, and he and his wife raised 5 children. They also brought several foster children into their home. He had no pre-surgical history of treatment for depression or other psychological problems. He smoked cigarettes for many years (and eventually quit); he did not abuse alcohol or drugs. The patient underwent a right anterior temporal lobectomy (including amygdalohippocampectomy) at age 46 for pharmacoresistant epilepsy.

Following surgery, the patient was seizure free, and he was able to taper off of anticonvulsant medication. His cognitive functioning was well preserved, aside from a minor weakness in visual memory (not evident in neuropsychological testing). However, he developed notable changes in personality and emotional processing, marked especially by emotional lability and irritability. His wife, in particular, reported that he was much more irritable and emotional. He lost his temper easily, e.g., when dealing with his children, he would “yell all the time” at his kids. He was emotionally labile and developed a proclivity to overreact emotionally to minor events in his life. He cried easily. He would remain irritated for days, often following minor provocations. His wife also reported that he had increased anxiety. The patient concurred with these observations. We observed the patient to have significantly increased irritability as well—he seemed very “grumpy” during our testing, and was quite irritable with the examiner (e.g., when given feedback about incorrect responses, he would become angry and upset). In addition, he demonstrated significant impulsivity and some perseverative tendencies during neuropsychological testing, which were different from the pre-surgical epoch. Some of these changes were evident in the formal neuropsychological tests—e.g., he had an impaired performance on the Wisconsin Card Sorting Test, as he completed only 4 of the 6 category sorts and had 12 perseverative errors and 2 failures to maintain set (see Table 2).

The patient did not return to his job as an independent contractor following the surgery. He developed significant problems with depression, in addition to the aforementioned problems with anxiety and emotional lability, and was started on antidepressant medication (which helped). He attempted some odd jobs, e.g., as a cook in a nursing home. Due to the patient’s emotional lability and irritability, he and his wife decided to stop having foster children in their home, and they have never returned to this activity. On the various measurements pertinent to the current study, the patient was rated as having an overall severe change in Social Conduct, with marked change/impairment in social status, employment status, and interpersonal functioning. He had mild depression on the Beck Depression Inventory-II and non-significant anxiety symptomatology on the Beck Anxiety Inventory. On the MMPI-2, he generated a “defensive” response profile, endorsing a large number of items that probe common foibles and weaknesses that are typically acknowledged by most individuals (this produces an elevated score on the “L” scale, and precludes strict interpretation of the clinical scales, which were not elevated). The patient was rated (by his wife) as having significant acquired personality problems and changes on the Iowa Rating Scales of Personality Change. Specifically, the wife indicated that he had significantly more (worse) perseveration, depression, moodiness, lack of planning, poor judgment, social inappropriateness, impatience, and indecisiveness. Finally, on the Iowa Gambling Task, the patient had an impaired performance, with a preference for disadvantageous choices during the game that led to an overall loss (net score of −18). He also failed to develop anticipatory skin conductance responses to the disadvantageous card decks, and this defect was especially pronounced during the latter part of the task (trials 61 to 100).

The amygdala lesion for 2713 is depicted in Figure 1b. The amygdala is substantially damaged on the right. The surgical report indicated that the amygdala was included in the resection, along with the hippocampus.

In summary, this man with a right amygdala lesion developed severe impairments in social conduct, emotional processing and personality, and complex decision-making. The most prominent changes included emotional dysregulation, with emotional lability and irritability, as well as depression and anxiety.

Woman with left amygdala damage (case 3310)

This patient is a 51-year-old, fully right-handed woman who completed a high school education. She is married, and worked for many years as a secretary (mainly a scheduler) for a local manufacturer; she held this job up until the time of her surgical procedure (temporal lobectomy). She smoked cigarettes for many years before quitting, and did not use alcohol or drugs. She had no history of treatment for depression or other psychological difficulties prior to the surgery. She developed a seizure disorder at age 22, which was treated successfully with medications for a number of years; however, her seizures eventually became medication-refractory. She underwent a left anterior temporal lobectomy (including amygdalohippocampectomy) at age 49. Following the surgery, her seizures were much improved, but she was not completely seizure-free and she was maintained on anticonvulsant medication (the medications, Trileptal and Keppra, were the same as before surgery, but at lower doses).

After the temporal lobectomy, the patient developed prominent difficulties in emotional functioning and personality, marked especially by emotional lability, irritability (a “short fuse”), depression, and anxiety. She attempted to return to her job, but was not able to perform her former duties and was terminated. She has not been able to secure gainful employment since her operation, and she applied for (and was eventually awarded) social security disability. She began experiencing major depression and anxiety symptoms, and was referred to a psychiatrist who diagnosed her with Anxiety Disorder (Not Otherwise Specified), and put her on Celexa for “emotional incontinence.” Our observations were similar: during neuropsychological testing, the patient exhibited disinhibition (e.g., profanity during testing) and inappropriate humor. She was irritable at times, but then would suddenly become inexplicably euthymic. She demonstrated impulsivity and perseveration. These problems were evident on formal testing, too—for example, on the Wisconsin Card Sorting Test she accomplished only 2 correct sorts, and she made 28 perseverative errors and had 4 failures to maintain set (see Table 2).

The patient had significant changes in her interpersonal functioning, and stopped participating in activities that she used to enjoy with friends. On the formal measures pertinent to the current study, the patient was rated as having a severe overall change in Social Conduct, with severe change/impairment in social status, employment status, and interpersonal functioning. She had severely elevated scores on the Beck Depression Inventory-II and the Beck Anxiety Inventory. Her MMPI-2 profile was markedly abnormal, with severe elevations on several clinical scales including measures of anxiety, depression, and unusual thinking. On the Iowa Rating Scales of Personality Change, her husband reported that following surgery, she has significantly more (worse) lack of initiative, perseveration, depression, moodiness, lack of stamina, lack of persistence, lack of planning, poor judgment, social inappropriateness, dependency, impatience, and indecisiveness. The patient had an impaired performance on the Iowa Gambling Task (IGT), choosing more frequently from the disadvantageous decks and garnering an overall losing score (net score of −8); she also failed to develop anticipatory skin conductance responses to the disadvantageous decks. Her IGT performance was in fact similar to what we have observed in patients with ventromedial prefrontal dysfunction, as she began by selecting more from the disadvantageous decks, switched over to prefer slightly the advantageous decks by the middle of the game, and then switched back to the disadvantageous decks during the latter part of the game (cf. Bechara et al., 2000).

In keeping with her left anterior temporal lobe damage, this patient also manifested defects in verbal memory and some aspects of language (especially naming) following her anterior temporal lobectomy (see Table 2). She had mildly impaired performances on verbal memory tests, including the Auditory-Verbal Learning Test. Her speech was fluent, but she had word finding difficulties and mild defects in aural comprehension (on the Token Test); however, her ability to comprehend conversational speech and test instructions was intact. Visual confrontation naming was impaired (a common finding in patients with left anterior temporal damage), and in particular, she had very impaired retrieval of proper names (cf. Yucus & Tranel, in press). In the context of the current report, it is important to underscore that these language and verbal memory defects, whilst contributing to the patient’s overall cognitive morbidity, do not account for or explain fully her problems in the domains of social conduct, emotional processing/personality, and decision-making. In fact, the patient had some pre-surgical defects in word finding and verbal memory (especially the latter), but lacked pre-surgical impairments in the social conduct/emotional processing domains (and was successfully employed), which supports the conclusion that language and verbal memory problems do not account for the social conduct and emotional processing defects that developed post-surgically.

The amygdala lesion for 3310 is depicted in Figure 2a. There is partial damage to the amygdala on the left. The remaining amygdala tissue likely has little functional connectivity, judging from the adjacent damage to the parahippocampal gyrus. The surgical report for this patient indicated that an amygdalohippocampectomy was performed.

To summarize, this woman with left amygdala damage developed severe impairments in social conduct, emotional processing and personality, and complex decision-making. Changes in emotional regulation were especially prominent, and she had marked emotional lability and irritability. Anxiety and depression were also prominent post-surgical manifestations.

The changes in this woman were reminiscent of those we observed in the man with a right-sided amygdala lesion reported immediately above (2713)—in both patients, the most prominent manifestations were poor emotional regulation, pronounced emotional lability, and irritability, as well as anxiety and depression. Emotional lability and emotional dysregulation are manifestations that frequently dominate the picture in patients with ventromedial prefrontal lesions (e.g., Anderson et al., 2006; Barrash et al., 2000; Koenigs & Tranel, 2007), and the parallels here are intriguing.

Woman with right amygdala damage (case 2897)

This patient is a 51-year-old, fully right-handed woman with a high school education. She has worked for many years for the government, as a weapons parts buyer for an arsenal that manufactures war weapons. She developed seizures at age 19, with no known cause, and took anticonvulsant medication which helped control her seizures. However, the seizures worsened, and she eventually underwent a right anterior temporal lobectomy (at another institution) at the age of 42. Following the operation, she reported improvements in concentration, memory, and sleep, and there were no adverse effects on her cognitive functioning per neuropsychological assessment. She also did not evidence any significant behavioral or emotional changes. However, her seizures continued, and remained refractory to medications, and she underwent a second right anterior temporal lobectomy at our institution at age 46. This operation targeted additional temporal structures, including the amygdala, but spared the hippocampus. The patient did not have a premorbid history of treatment for psychiatric problems, although she had lifelong characteristics of low self-confidence and being a “worrier.” She smoked cigarettes for many years before quitting about a decade prior to her first temporal lobectomy. She did not abuse alcohol or drugs. She was married for many years, but there were significant marital problems that dated back to before her first surgery and continued afterwards. She eventually was formally divorced at age 48, approximately two years after the second operation; however, this dissolution had been several years in the making and did not appear to be related to either of the temporal lobectomy procedures.

Following the second temporal lobectomy, the patient had considerable improvement in her seizure disorder, although she did not achieve seizure-free status and she has continued to take medication (Keppra). She did not evidence any post-morbid changes in social conduct, emotional processing, or personality. She continued to work full-time at her job, without difficulty, and she has received regular performance appraisals that have never noted any concerns or problems with the quality of her work. In fact, there was a dramatic increase in her job demands following the attacks on the US in 2001, which occurred almost exactly a month after her operation, and she was able to cope with these changes successfully (the arsenal at which she works underwent a rapid expansion that increased the workforce and workflow by orders of magnitude after 9/11/01). The patient complained of some mild problems with “losing things,” but she otherwise functioned normally in her everyday life and did not have notable behavioral or psychological manifestations.

Our assessment documented the largely intact status of the patient’s postmorbid functioning. She had mild defects in visuospatial memory and visuoperceptual discrimination (e.g., as evidenced by defects on the Visual Retention Test and Facial Discrimination Test, see Table 2), but otherwise did not have deficits on neuropsychological assessment. She performed very well on the Wisconsin Card Sorting Test, achieving all 6 category sorts with very few perseverative errors and no failures to maintain set. On the formal measures pertinent to the current investigation, the patient was rated as having no change in Social Conduct, with no changes/impairments in social status, occupational functioning, or interpersonal functioning. She continued to engage the same social activities as she had prior to her second surgery, and her interpersonal relationships remained intact (outside of the expected rearrangements associated with her divorce). She did not report depression or anxiety on the Beck Depression Inventory-II and Beck Anxiety Inventory, respectively. Her MMPI-2 profile was mildly elevated, with evidence of low self confidence and self-criticalness (interpreted by the clinical neuropsychologist as longstanding traits). She did not have acquired personality problems per ratings from the Iowa Rating Scales of Personality Change (completed by a friend), and she performed very well on the Iowa Gambling Task, with a net positive score (+22) and normal anticipatory skin conductance responses.

The amygdala lesion for 2897 is depicted in Figure 2b. It can be seen that the amygdala is substantially damaged on the right, and the little remaining amygdala tissue likely has no meaningful connectivity judging from the adjacent damage to the parahippocampal gyrus. The surgical report from the first surgery (from the Mayo Clinic) indicated that the amygdala had been resected.

To summarize, this woman with right amygdala damage had no significant impairments in social conduct, emotional processing and personality, or complex decision-making.

DISCUSSION

We used a case-matched lesion approach to explore the question of whether there might be sex-related functional asymmetry of the amygdala with respect to functions such as social conduct, emotional processing and personality, and complex decision-making. The results provide preliminary support for this notion. In a matched pair of men participants, the man with right-sided amygdala damage developed major defects in social conduct, emotional processing and personality, and decision-making, whereas the man with left-sided amygdala damage did not. In a matched pair of women participants, the opposite pattern obtained: the woman with left-sided amygdala damage developed defects in social conduct, emotional processing and personality, and decision-making, whereas the woman with right-sided amygdala damage did not. These results have an interesting parallel with recent findings in patients with unilateral ventromedial prefrontal cortex (VMPC) lesions (Tranel et al., 2005), where not only did we observe sex-related functional asymmetry of the VMPC, but the direction—men right, women left—was also the same. The VMPC and amygdala are two key components of the main neural machinery that subserves functions such as social conduct, emotional processing, and complex decision-making (cf. Craig, 2002; Damasio, 1994, 1999), and it is intriguing that the evidence so far seems to indicate similar sex-related functional asymmetry of these structures.

The current findings are from a small number of patients, and they need to be replicated in more cases. Nonetheless, a strength of our approach is that nonspecific factors such as having a neurological disease, having a brain lesion, taking neurological medications, and going through brain surgery, can be dismissed with some confidence, since for each of the “affected” patients (the right-sided man and the left-sided woman), there was a matched patient who had the same nonspecific factors, but who did not experience post-lesion changes. This lends credence to our inference—viz., that the changes in the affected patients are primary consequences of amygdala damage, and not secondary effects of nonspecific factors such as having an acquired brain lesion. It is also worth commenting that although the patients we studied had different occupations with different demands, we find it highly unlikely that this would account for our findings. The left-sided man had responsibilities as a farmer that were as complex as those of the right-sided man who had worked as an independent contractor. And the right-sided woman who worked in a weapons arsenal had a job that was arguably more demanding than that of the left-sided woman who had worked as a secretary/scheduler, and yet it was the left-sided woman who had a post-lesion demise of her occupational status (whilst the right-sided woman continued to perform well in her job following her amygdale damage).

A steadily growing body of research has pointed to sex-related functional asymmetry of the amygdala. For example, as summarized in the Introduction, studies of how the amygdala modulates the influence of emotion on memory have consistently shown that the right amygdala is important in men, whereas the left amygdala is important in women (see Cahill, 2006, for review). Sex-related differences in amygdale responsiveness to emotional facial expressions have also been found (e.g., Killgore & Yurgelun-Todd, 2001; Williams et al., 2005). Structurally, there is also evidence for sexual dimorphism of amygdala (e.g., Goldstein et al., 2001), possibly more so than for many other brain structures (e.g., Mechelli et al., 2005). Much remains to be learned about sex differences and the amygdala, from both functional and structural perspectives, but as Cahill (2006) has emphasized, even the evidence available so far is sufficient to underscore the importance of taking sex and hemisphere into account when studying brain-behavior relationships concerning the amygdala. The current findings put a further stamp on this message.

One question that can be raised in this context is why such sex-related differences have not been noticed or reported more prominently in previous literature, if indeed they exist. We would offer a couple of explanations. One is the simple fact that sex-related differences have been veritably taboo in much of neuroscience research: investigators have ignored, dismissed, and otherwise side-stepped issues of sex differences, perhaps because such differences often complicate the picture (and require grant-writers to double their sample sizes). In a related vein, sex differences are topically unpopular: they have prompted strident debates in the literature, where one can find the entire gamut of opinion ranging from staunch supporters to those who flatly deny that any such differences exist. It is not surprising that many authors have chosen to avoid drawing fire by simply going around this battleground. Another explanation is that researchers have not paid attention to such differences, even when they may be right there in the data. For example, in our perusal of the literature on sex-related functional asymmetry of prefrontal structures (Tranel et al., 2005), we turned up an impressive number of studies and cases where sex-related differences appeared obvious and even compelling, but the researchers had hardly commented—or had not commented at all—on such differences in their data. In retrospect, we found a surprising number of studies where the gender of the participants, when considered anew from the perspective of sex differences, suddenly could be seen to explain many of the findings, including ones that had seem incongruent on first pass (e.g., Manes et al., 2002; see Tranel et al., 2005 for discussion). This is not to say that sex-related differences will turn out to be a major source of variance in many topics in cognitive and affective neuroscience, but we would at minimum like to echo the recommendations of Cahill (e.g., 2006) that such differences should at least be explored and properly acknowledged.

Another important question pertains to the “why and how” of sex-related differences (another issue that authors routinely skirt). A comprehensive discussion of this issue is well beyond the scope of the current article, but we would like to offer a few thoughts, albeit while acknowledging that we are speculating here and further research is critical to put empirical teeth into these ideas. There is, to begin with, the incontrovertible fact that women bear children and men do not. This biological reality surely has implications for the neurobiology of social and emotional processing, and could prompt sex-related differences in the manner in which men and women apprehend, process, and execute emotional information and solve social problems. As another perspective, consider the fact that mothering and fathering usually do not entail identical sets of parenting activities. For example, de Morneffe (2007), in her book Maternal Desire, has commented on aspects of mothering that are beyond the realm of experience of fathers simply because of biological realities.

Moving closer back to neuroscience, numerous studies have described gender-related differences in the lateralization of various cognitive functions. More specifically, women tend to engage more left-lateralized language and emotion processing, whereas men often tend toward right-lateralized visuospatial processing (e.g., Allen & Gorski, 1991; Azim, Mobbs, Jo, Menon, & Reiss, 2005; Frings et al., 2006; Gray, 1992; Nowicka & Fersten, 2001), although some studies have shown more mixed results (e.g., Hall, Witelson, Szechtman, & Nahmias, 2004; Koch et al., 2007). Furthermore, there is evidence that there are sex differences in the ways in which the two hemispheres are connected and communicate with each other (Allen & Gorski, 1991; Nowicka & Fersten, 2001), and more specifically, women have been credited with dominance in verbal-based approaches (Shaywitz et al., 1995; Vikingstad, George, Johnson, & Cao, 2000) and with reportedly larger volumes of Broca’s area (Harasty, Double, Halliday, Kril, & McRitchie, 1997) and adjacent dorsolateral prefrontal cortex (Schlaepfer et al., 1995). Thus, men and women tend to diverge even at levels of basic neural processing and structure. We speculate that there is an evolutionary advantage for women to have their emotional processes more tied to their verbal systems, since, for example, caring, teaching, and responding to the needs of offspring would rely heavily on verbal means. On the other hand, it may be more advantageous for men to have their emotional processes tied to visuospatial systems, since evolutionarily speaking, survival skills such as hunting and food procurement would depend heavily on such nonverbal processes. Perhaps this can help explain why emotional systems are skewed to the left hemisphere in women, and to the right hemisphere in men. Given the evidence that neural systems supporting decision-making and social functioning overlap with neural systems subserving emotions (e.g., Bar-On, Tranel, Denburg, & Bechara, 2003), this would also explain why the decision-making and social functioning capacities of women are more dependent on the left hemisphere, whereas those in men are more dependent on the right hemisphere.

Taking a step back from our data, it is interesting to situate our study in the broader context of the burgeoning literature on how the amygdala relates to functions such as social behavior, emotional processing, and higher-order decision-making. For example, Hessl et al. (2007) found that men with the fragile X premutation had reduced amygdala responsiveness and impaired fear potentiated startle responses to fearful faces, as well as reduced skin conductance responses to stressful social encounters, and the authors suggested that amygdala dysfunction could be at the root of the social cognition deficits that typify children and adults with fragile X premutation. Another interesting study was reported recently by Glahn and colleagues (2007), who found that behaviorally disinhibited temperament was common in individuals with a positive family history of alcoholism, and may be associated with amygdala hyporesponsiveness and a failure to avoid risky decisions. The authors went on to suggest that this proclivity—and the amygdala dysfunction that underpins it—could increase an individual’s vulnerability to alcohol abuse (Glahn et al., 2007). This latter point brings us to an important link to some of our own thinking about how amygdala (dys)function may play an important role in alcohol and drug abuse. A full discussion of this idea is beyond the scope of the current report, but we would like to say a few words about this link, because we have focused prominently on the amygdala (and VMPC) in our conceptualization of substance abuse being especially a disorder of decision-making caused by “myopia for the future.”

It has been shown that autonomic responses to large sums of monetary gains or losses depend on the integrity of the amygdala (Bechara et al., 1999). It has also been shown that the brain can encode the value of various options on a common scale (e.g., Montague & Berns, 2002), suggesting that there may be a common neural “currency” that encodes the value of different options, whether they be money or food, sex, or other basic rewards. Similarly, drugs may acquire powerful affective and emotional properties. In addicts, fast, automatic and exaggerated autonomic responses are triggered by cues related to the substance they abuse, similar to the effects of monetary gains (Bechara, 2005). In this context, the current findings may have important implications for the understanding of the neurobiology of drug and alcohol abuse (cf. Bechara, 2005), especially insofar as the amygdala is concerned.

Before concluding, it is important to acknowledge some limitations of the current study. As already mentioned, the anatomical status of the participants is an approximation to the desired lesion preparation: while all patients had documented unilateral amygdala damage, the damage was not restricted to the amygdala, and it was not complete in all cases (although the functional status of remaining amygdala tissue is questionable). This is a limitation, and it will be important to conduct similar investigations in participants with more focal and circumscribed unilateral amygdale damage (although such patients are very rare). In a related vein, there is evidence that the temporal pole per se (at least on the right side) might play a significant role in social and emotional processing, especially face processing and “theory of mind” abilities (see review by Olson, Plotzker, & Ezzyat, 2007; see also Thompson et al., 2003; Gorno-Tempini et al., 2004; Zahn et al., 2007). Although many of the relevant patients in these studies have “lesions” caused by degenerative disease conditions (e.g., temporal-variant frontotemporal dementia, Thompson et al., 2003), which prompts caution in ascribing too much anatomical weight to these findings, it could be that the temporal pole does play a role in social-emotional processing. To the extent that the patients in our study have temporal pole damage as part of their ATL, this is a caveat in our interpretation of the cognitive-behavioral outcomes being attributable to the amygdala; again, further studies with patients who have damage restricted to the amygdala will be important to tease this apart.

Finally, there are caveats concerning the fact that the patients we studied had longstanding seizure disorders and were on anticonvulsant medications. As discussed earlier, none of our patients had early-onset seizures (by definition, prior to age 5), where the chances of functional reorganization are greatest (e.g., Griffin & Tranel, 2007), and it also seems quite clear that the entirety of our patients’ social, emotional, and decision-making defects cannot be accounted for on the basis of comorbidity in other cognitive functions. Nonetheless, we cannot rule out the possibility that some degree of amygdale dysfunction in our patients preceded the temporal lobectomy operation, and it is even possible that the underlying pathology of the amygdala and/or tissue in the surround could have dated back to earlier in the patients’ lives, perhaps even adolescence or childhood. Studies of patients with adult-onset amygdala damage and no history of seizures or potential earlier pathology will be important to resolve this issue.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We thank Ken Manzel for help in the collection and preparation of the data, and Ruth Henson and Kathy Jones for help in scheduling the subjects. Joel Bruss and the Grabowski Computational Neuroimaging Laboratory provided expert assistance with the preparation of the figures. We also thank Drs. Robert Levenson and Howard Rosen for comments on earlier drafts of this article. This work was supported by NIDA R01 DA022549 and NINDS P01 NS19632.

References

- Adolphs R. Recognizing emotion from facial expressions: psychological and neurological mechanisms. Behavioral and Cognitive Neuroscience Reviews. 2002;1:21–61. doi: 10.1177/1534582302001001003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adolphs R. Cognitive neuroscience of human social behavior. Nature Reviews Neuroscience. 2003;4:165–178. doi: 10.1038/nrn1056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allen LS, Gorski RA. Sexual dimorphism of the anterior commissure and massa intermedia of the human brain. Journal of Comparative Neurology. 1991;312:97–104. doi: 10.1002/cne.903120108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amaral DG, Price JL, Pitkänen A, Carmichael ST. Anatomical organization of the primate amygdaloid complex. In: Aggleton JP, editor. The amygdala: Neuropsychological aspects of emotion, memory, and mental dysfunction. New York: Wiley-Liss; 1992. pp. 1–66. [Google Scholar]

- Anderson AK, Christoff K, Panitz D, De Rosa E, Gabrieli JD. Neural correlates of the automatic processing of threat facial signals. Journal of Neuroscience. 2003;23:5627–5633. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.23-13-05627.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anderson SW, Barrash J, Bechara A, Tranel D. Impairments of emotion and real-world complex behavior following childhood- or adult-onset damage to ventromedial prefrontal cortex. Journal of the International Neuropsychological Society. 2006;12:224–235. doi: 10.1017/S1355617706060346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Azim E, Mobbs D, Jo B, Menon V, Reiss AL. Sex differences in brain activiation elicited by humor. PNAS. 2005;102:16496–16501. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0408456102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bachevalier J. The amygdala, social behavior, and autism. In: Aggleton JP, editor. The amygdala: A functional analysis. 2nd edition. New York: Oxford University Press; 2000. pp. 509–543. [Google Scholar]

- Bar-On R, Tranel D, Denburg NL, Bechara A. Exploring the neurological substrate of emotional and social intelligence. Brain. 2003;126:1790–1800. doi: 10.1093/brain/awg177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barrash J, Tranel D, Anderson SW. Acquired personality disturbances associated with bilateral damage to the ventromedial prefrontal region. Developmental Neuropsychology. 2000;18:355–381. doi: 10.1207/S1532694205Barrash. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bechara A. Disturbances of emotion regulation after focal brain lesions. International Review of Neurobiology. 2004;62:159–193. doi: 10.1016/S0074-7742(04)62006-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bechara A. Decision making, impulse control and loss of willpower to resist drugs: a neurocognitive perspective. Nature Neuroscience. 2005;8:1458–1463. doi: 10.1038/nn1584. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bechara A, Damasio H, Damasio A. The role of the amygdala in decision-making. In: Shinnick-Gallagher P, Pitkanen A, Shekhar A, Cahill L, editors. The amygdala in brain function: Basic and clinical approaches. Vol. 985. New York: Annals of the New York Academy of Science; 2003. pp. 356–369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bechara A, Damasio H, Damasio AR, Lee GP. Different contribution of the human amygdala and ventromedial prefrontal cortex to decision making. Journal of Neuroscience. 1999;19:5473–5481. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.19-13-05473.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bechara A, Tranel D, Damasio H. Characterization of the decision-making deficit of patients with ventromedial prefrontal cortex lesions. Brain. 2000;123:2189–2202. doi: 10.1093/brain/123.11.2189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buchanan TW, Adolphs R. The neuroanatomy of emotional memory in humans. In: Reisberg D, Hertel P, editors. Memory and Emotion. New York: Oxford University Press; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Buchanan TW, Tranel D, Adolphs R. Memories for emotional autobiographical events following unilateral damage to medial temporal lobe. Brain. 2006;129:115–127. doi: 10.1093/brain/awh672. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buchel C, Morris J, Dolan RJ, Friston KJ. Brain systems mediating aversive conditioning: an event-related fMRI study. Neuron. 1998;20:947–957. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80476-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cahill L. Sex-related influences on the neurobiology of emotionally influenced memory. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences. 2003;985:163–173. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2003.tb07080.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cahill L. Why sex matters for neuroscience. Nature Reviews Neuroscience. 2006;7:477–484. doi: 10.1038/nrn1909. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cahill L, Gorski L, Belcher A, Huynh Q. The influence of sex versus sex-related traits on long-term memory for gist and detail from an emotional story. Consciousness and Cognition. 2004;13:391–400. doi: 10.1016/j.concog.2003.11.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cahill L, Haier R, Fallon J, Alkire M, Tang C, Keator D, Wu J, McGaugh JL. Amygdala activity at encoding correlated with long-term, free recall of emotional information. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 1996;93:8016–8021. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.15.8016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cahill L, Haier RJ, White NS, Fallon J, Kilpatrick L, Lawrence C, Potkin SG, Alkire MT. Sex-related difference in amygdala activity during emotionally influenced memory storage. Neurobiology of Learning and Memory. 2001;75:1–9. doi: 10.1006/nlme.2000.3999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cahill L, Uncapher M, Kilpatrick L, Alkire M, Turner J. Sex-related hemispheric lateralization of amygdala function in emotionally influenced memory: An fMRI investigation. Learning & Memory. 2004;11:261–266. doi: 10.1101/lm.70504. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Canli T, Desmond JE, Zhao Z, Gabrieli JDE. Sex differences in the neural basis of emotional memories. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 2002;99:10789–10794. doi: 10.1073/pnas.162356599. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Canli T, Gabrieli J. Imaging gender differences in sexual arousal. Nature Neuroscience. 2004;7:325–326. doi: 10.1038/nn0404-325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Canli T, Zhao Z, Brewer J, Gabrieli J, Cahill L. Event-related activation in the human amygdala associates with later memory for individual emotional experience. Journal of Neuroscience. 2000;20:RC99. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.20-19-j0004.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Canli T, Zhao Z, Desmond J, Glover G, Gabrieli J. fMRI identifies a network of structures correlated with retention of positive and negative emotional memory. Psychobiology. 1999;27:441–452. [Google Scholar]

- Carmichael ST, Price JL. Limbic connections of the orbital and medial prefrontal cortex in macaque monkeys. Journal of Comparative Neurology. 1995;363:615–641. doi: 10.1002/cne.903630408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Craig AD. How do you feel? Interoception: the sense of the physiological condition of the body. Nature Reviews Neuroscience. 2002;3:655–666. doi: 10.1038/nrn894. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Damasio AR. Descartes’ error: Emotion, reason, and the human brain. New York: Grosset/Putnam; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Damasio AR. The feeling of what happens. New York: Harcourt Brace & Company; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Damasio H. The lesion method in cognitive neuroscience. In: Boller F, Grafman J, editors. Handbook of neuropsychology. 2nd Edition. Vol. 1. Amsterdam: Elsevier; 2000. pp. 77–102. [Google Scholar]

- de Morneffe D. Maternal desire: On children, love, and the inner life. New York: Little, Brown Book Group; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Everitt BJ, Parkinson J, Olmstead M, Arroyo M, Robledo, Robbins T. Associative processes in addiction and reward: the role of amygdala and ventral striatal subsystems. In Advancing from the ventral striatum to the extended amygdala. In: McGinty JF, editor. Annals of the New York Academy of Science. Vol. 877. 1999. pp. 412–438. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frank RJ, Damasio H, Grabowski TJ. Brainvox: An interactive, multimodal, visualization and analysis system for neuroanatomical imaging. NeuroImage. 1997;5:13–30. doi: 10.1006/nimg.1996.0250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frings L, Wagner K, Unterrainer J, Spreer J, Halsband U, Schultze-Bonhage A. Gender-related differences in lateralization of hippocampal activation and cognitive strategy. NeuroReport. 2006;17:417–421. doi: 10.1097/01.wnr.0000203623.02082.e3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gallagher M, Chiba AA. The amygdala and emotion. Current Opinion in Neurobiology. 1996;6:221–227. doi: 10.1016/s0959-4388(96)80076-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garavan H, Pankiewicz J, Bloom A, Cho J-K, Sperry L, Ross TJ, Salmeron BJ, Risinger R, Kelley D, Stein EA. Cue-induced cocaine craving: Neuroanatomical specificity for drug users and drug stimuli. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2000;157:1789–1798. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.157.11.1789. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glahn DC, Lovallo WR, Fox PT. Reduced amygdala activation in young adults at high risk of alcoholism: Studies from the Oklahoma Family Health Patterns project. Biological Psychiatry. 2007;61:1306–1309. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2006.09.041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldstein JM, Seidman LJ, Horton NJ, Makris N, Kennedy DN, Caviness VS, Faraone SV, Tsuang MT. Normal sexual dimorphism of the adult human brain assessed by in vivo magnetic resonance imaging. Cerebral Cortex. 2001;11:490–497. doi: 10.1093/cercor/11.6.490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gorno-Tempini ML, Rankin KP, Woolley JD, Rosen HJ, Phengrasamy L, Miller BL. Cognitive and behavioral profile in a case of right anterior temporal lobe neurodegeneration. Cortex. 2004;40:631–644. doi: 10.1016/s0010-9452(08)70159-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gray J. Men are from Mars, women are from Venus. New York: Thorsons/Harper Collins; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Greenberg DL, Rice HJ, Cooper JJ, Cabeza R, Rubin DC, LaBar KS. Co-activation of the amygdala, hippocampus and inferior frontal gyrus during autobiographical memory retrieval. Neuropsychologia. 2005;43:659–674. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropsychologia.2004.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Griffin SL, Tranel D. Age of onset, functional reorganization, and neuropsychological outcome in temporal lobectomy. Journal of Clinical and Experimental Neuropsychology. 2007;29:13–24. doi: 10.1080/13803390500263568. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hall GBC, Witelson SF, Szechtman H, Nahmias C. Sex differences in functional activation patterns revealed by increased emotion processing demands. NeuroReport. 2004;15:219–223. doi: 10.1097/00001756-200402090-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamann S, Ely T, Grafton S, Kilts C. Amygdala activity related to enhanced memory for pleasant and aversive stimuli. Nature Neuroscience. 1999;2:289–293. doi: 10.1038/6404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harasty J, Double KL, Halliday GM, Kril JJ, McRitchie DA. Language-associated cortical regions are proportionally larger in the female brain. Archives of Neurology. 1997;54:171–176. doi: 10.1001/archneur.1997.00550140045011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hariri AR, Tessitore A, Mattay VS, Fera F, Weinberger DR. The amygdala response to emotional stimuli: a comparison of faces and scenes. NeuroImage. 2002;17:317–323. doi: 10.1006/nimg.2002.1179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hessl D, Rivera S, Koldewyn K, Cordeiro L, Adams J, Tassone F, Hagerman PJ, Hagerman RJ. Amgydala dysfunction in men with the fragile X premutation. Brain. 2007;130:404–416. doi: 10.1093/brain/awl338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hill D, Pond DA, Mitchell W, Falconer MA. Personality changes following temporal lobectomy for epilepsy. Journal of Mental Science. 1957;100:18–27. doi: 10.1192/bjp.103.430.18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Killgore W, Yurgelun-Todd D. Sex differences in amygdala activation during the perception of facial affect. Neuroreport. 2001;12:2543–2547. doi: 10.1097/00001756-200108080-00050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kluver H, Bucy PC. Preliminary analysis of functions of the temporal lobes in monkey. Archives of Neurology and Psychiatry. 1939;42:979–1000. [Google Scholar]

- Koch K, Pauly K, Kellermann T, Seiferth NY, Reske M, Backes V, Stocker T, Shah NJ, Amunts K, Kircher T, Schneider F, Habel U. Gender differences in the cognitive control of emotion: An fMRI study. Neuropsychologia. 2007;45:2744–2754. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropsychologia.2007.04.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koenigs M, Tranel D. Irrational economic decision-making after ventromedial prefrontal damage: Evidence from the Ultimatum Game. Journal of Neuroscience. 2007;27:951–956. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4606-06.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LaBar KS, Cabeza R. Cognitive neuroscience of emotional memory. Nature Reviews Neuroscience. 2006;7:54–64. doi: 10.1038/nrn1825. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LaBar KS, Phelps EA. Arousal-mediated memory consolidation: Role of the medial temporal lobe in humans. Psychological Science. 1998;9:490–493. [Google Scholar]

- Levin IP, Hart SS. Risk preferences in young children: Early evidence of individual differences in reaction to potential gains and losses. Journal of Behavioral Decision Making. 2003;16:397–413. [Google Scholar]

- Mackiewicz KL, Sarinopoulos I, Cleven KL, Nitschke JB. The effect of anticipation and the specificity of sex differences for amygdala and hippocampus function in emotional memory. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences USA. 2006;103:14200–14205. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0601648103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manes F, Sahakian B, Clark L, Rogers R, Antoun N, Aitken M, Robbins T. Decision-making processes following damage to the prefrontal cortex. Brain. 2002;125:624–639. doi: 10.1093/brain/awf049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGaugh JL, Cahill L, Roozendaal B. Involvement of the amygdala in memory storage: interaction with other brain systems. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences USA. 1996;93:13508–13514. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.24.13508. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mechelli A, Friston KJ, Frackowiak RS, Price CJ. Structural covariance in the human cortex. Journal of Neuroscience. 2005;25:8303–8310. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0357-05.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meunier M, Bachevalier J, Murray EA, Malkova L, Mishkin M. Effects of aspiration versus neurotoxic lesions of the amygdala on emotional responses in monkeys. European Journal of Neuroscience. 1999;11:4403–4418. doi: 10.1046/j.1460-9568.1999.00854.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Montague PR, Berns GS. Neural economics and the biological substrates of valuation. Neuron. 2002;36:265–284. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(02)00974-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Montague PR, Hyman SE, Cohen JD. Computational roles for dopamine in behavioural control. Nature. 2004;431:760–767. doi: 10.1038/nature03015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Norris CJ, Chen EE, Zhu DC, Small SL, Cacioppo JT. The interaction of social and emotional processes in the brain. Journal of Cognitive Neurosciences. 2004;16:1818–1829. doi: 10.1162/0898929042947847. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nowicka A, Fersten E. Sex-related differences in interhemispheric transmission time in the human brain. Neuroreport. 2001;12:4171–4175. doi: 10.1097/00001756-200112210-00061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olson IR, Plotzker A, Ezzyat Y. The enigmatic temporal pole: A review of findings on social and emotional processing. Brain. 2007;130:1718–1731. doi: 10.1093/brain/awm052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Öngür D, Price JL. The organization of networks within the orbital and medial prefrontal cortex of rats, monkeys and humans. Cerebral Cortex. 2000;10:206–219. doi: 10.1093/cercor/10.3.206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phelps EA. Human emotion and memory: interactions of the amygdala and hippocampal complex. Current Opinion in Neurobiology. 2004;14:198–202. doi: 10.1016/j.conb.2004.03.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pitkänen A. Connectivity of the rat amygdaloid complex. In: Aggleton JP, editor. The amygdala: A functional analysis. 2nd edition. New York: Oxford University Press; 2000. pp. 31–115. [Google Scholar]

- Porrino LJ, Crane AM, Goldman-Rakic PS. Direct and indirect pathways from the amygdala to the frontal lobe in rhesus monkeys. Journal of Comparative Neurology. 1981;198:121–136. doi: 10.1002/cne.901980111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]