Abstract

Identification and annotation of mutated genes or proteins involved in oncogenesis and tumor progression are crucial for both cancer biology and clinical applications. We have developed a human Cancer Proteome Variation Database (CanProVar) by integrating information on protein sequence variations from various public resources, with a focus on cancer-related variations. We have also built a user-friendly interface for querying the database. The current version of CanProVar comprises 8,570 cancer-related variations in 2,921 proteins derived from existing genome variation databases and recently published large-scale cancer genome re-sequencing studies. It also includes 41,541 non-cancer specific variations in 30,322 proteins derived from the dbSNP database. CanProVar provides quick access to known cancer-related variations in protein sequences along with related cancer samples, relevant publications, data sources, and functional information such as Gene Ontology annotations for the proteins, protein domains in which the variation occurs, and protein interaction partners with cancer-related variations. CanProVar also helps reveal functional characteristics of cancer-related variations and proteins bearing these variations. Our analysis showed that cancer-related variations were enriched in certain protein domains. We also showed that proteins bearing cancer-related variations were more likely to interact with each other in the protein interaction network. CanProVar can be accessed from http://bioinfo.vanderbilt.edu/canprovar.

Keywords: cancer, database, web application, proteomics, mutation

Introduction

Cancer is a complex process that involves genetic alterations [Hoeijmakers, 2001]. Genomic sequence can be altered in small and large scales, and the alterations can fall in protein coding or non-coding regions. Variations in the coding regions that alter protein sequences can directly or indirectly affect protein stability, functionality, and its interactions with other proteins [Chasman and Adams, 2001; Wang and Moult, 2001]. These variations have the highest impact on phenotype and are more likely to cause disease [Cargill, et al., 1999; Fredman, et al., 2006; Ramensky, et al., 2002]. Therefore, identification and characterization of protein sequence-altering variations in human cancer are key steps to improving our understanding of tumorigenesis and progression, as well as cancer prevention, early diagnosis, and therapeutics [Engle, et al., 2006; Hoeijmakers, 2001].

Mutations causing inherited cancer syndromes increase the risk of cancers by orders of magnitude, such as a mutation in the neurofibromin gene that causes the type I neurofibromatosis [Trovo-Marqui and Tajara, 2006]. However, these mutations are relatively rare. In contrast, less dramatic inherited variations, i.e. polymorphisms, in a large number of genes influence cancer risk only slightly to moderately, but are highly prevalent. NCBI's dbSNP database provides the most comprehensive collection for both single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) and short deletion and insertion polymorphisms, which facilitates large-scale exploration of associations between diseases and variations. A wide variety of diseases, including both monogenic and complex diseases, have been linked to SNPs that affect protein functions through altering transcription factor binding sites, reducing protein solubility, and destabilizing protein structures etc. [Botstein and Risch, 2003; Chanock, 2001; Chasman and Adams, 2001; Karchin, et al., 2005]. These associations are documented in databases such as the Online Mendelian Inheritance in Man (OMIM) [Hamosh, et al., 2005], the HGVbase [Fredman, et al., 2002], the Human Gene Mutation Database [Stenson, et al., 2003], and the Human Proteome Initiative (HPI) database. Noticeably, HPI has comprehensively archived 21,945 variations related to human diseases including many complex diseases from more than 100,000 literature references (release 57.1) [Boeckmann, et al., 2003; Boeckmann, et al., 2005; O'Donovan, et al., 2001]. Applications such as SNPs3D [Wang and Moult, 2001], PolyDoms [Jegga, et al., 2007], and MedRefSNP [Rhee and Lee, 2009] have been created for searching disease candidate gene or SNPs by integrating data from dbSNP, OMIM and PubMed. Because many disease-causing SNPs remain unknown, databases and applications have also been developed to annotate or predict nonsynonymous SNPs (nsSNPs) that may alter protein structure and functionality and therefore change disease susceptibility [Dantzer, et al., 2005; Han, et al., 2006; Jegga, et al., 2007; Karchin, et al., 2005; Reumers, et al., 2005; Sunyaev, et al., 2001; Uzun, et al., 2007; Wang and Moult, 2001; Yip, et al., 2004].

Above described resources focus primarily on inheritable germline variations. Nevertheless, the majority of genetic alterations found in cancer cells are acquired by mutations in somatic cells. Large-scale studies have been carried out to identify somatic mutations related to epidemiological and clinical outcomes. Sjöblom et al. analyzed 13,023 well-annotated protein-coding genes in breast and colorectal cancers and identified 189 genes that accumulated mutations at significant frequencies [Sjoblom, et al., 2006]. Greenman et al. detected more than 1,000 somatic mutations in the coding exons of 518 protein kinase genes in 210 diverse human cancers [Greenman, et al., 2007]. Recently, the National Cancer Institute (NCI) and the National Human Genome Research Institute (NHGRI) have launched the Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) project to systematically explore the entire spectrum of genomic changes involved in human cancer using genome analysis technologies, including large-scale genome sequencing [TCGA, 2008]. Despite the increasing pace of data generation, efforts on compiling and organizing these data for useful exploitation are still limited [Olivier, et al., 2009]. One public resource that extensively compiles data on somatic gene alterations in cancers is the Catalogue of Somatic Mutations in Cancer (COSMIC, www.sanger.ac.uk/genetics/CGP/cosmic) [Bamford, et al., 2004]), which includes 722,718 somatic mutations in 4,773 genes in the latest version. Other cancer mutation databases focus on alterations in one or a few selected genes, such as the TP53 database (http://p53.free.fr).

Existing proteome variation databases differ in variation type (germline vs somatic), disease type (cancer vs non-cancer), and scale (genome scale vs selected genes). Obviously an integrated and well-annotated resource with a focus on the protein sequence-altering variations in human cancer is imperatively needed for the cancer research community. In this paper, we describe CanProVar, an integrated Human Cancer Proteome Variation Database that integrates both germline and somatic cancer-related variations (crVARs). CanProVar focuses on missense and nonsense variations as well as the deletion and insertion of single amino acid. Owing to its protein-centric nature, CanProVar can serve as a bridge between genomic data and proteomic studies. We demonstrate that this database can help reveal functional characteristics of crVARs and proteins bearing these variations, i.e. cancer-related proteins (crPROs).

Data sources and processing

We compiled crVAR data from six sources, including public databases HPI [O'Donovan, et al., 2001], COSMIC [Bamford, et al., 2004], OMIM [Hamosh, et al., 2005], and TCGA [TCGA, 2008], and data from two recently published large-scale cancer genome re-sequencing studies [Greenman, et al., 2007; Sjoblom, et al., 2006] (Table 1). Single amino acid variations in the HPI database (HPI-savar release 56.9) were downloaded from http://ca.expasy.org/cgi-bin/lists?humsavar.txt. Corresponding annotations were retrieved by parsing the web pages using a PERL script. crVARs were further selected from the downloaded data using keywords “cancer”, “tumor”, “carcinoma”, “malignant neoplasm”, “sarcoma”, “blastoma”, “lymphoma”, or “leukemia”. Cancer somatic mutation data in CGP-COSMIC (release version 41) and corresponding protein sequences were downloaded from ftp://ftp.sanger.ac.uk/pub/CGP/cosmic/. Protein sequence alteration data generated by the TCGA project were downloaded from http://tcga-data.nci.nih.gov/docs/somatic_mutations/tcga_mutations.html. Mutations in the OMIM database were downloaded from http://www.bioinf.org.uk/omim/. Data from the large-scale studies on crVARs in coding sequences were manually extracted from the original publications [Greenman, et al., 2007; Sjoblom, et al., 2006].

Table 1. Data sources of CanProVar database.

| Data sources | Web link | crVARs* | remark |

|---|---|---|---|

| COSMIC | http://www.sanger.ac.uk/genetics/CGP/cosmic/ | 4,989 | Somatic |

| HPI | http://ca.expasy.org/sprot/hpi/ | 3,852 | Somatic and germline |

| TCGA | http://cancergenome.nih.gov/ | 329 | Somatic |

| OMIM | http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/omim/ | 264 | Mainly germline |

| Sjöblom et al.(2006) | http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/16959974 | 1,246 | Somatic |

| Greenman et al. (2007) | http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/17344846 | 465 | Somatic |

The number of cancer-related variations (crVARs) that were successfully mapped into Ensembl protein sequences.

One challenge in integrating data from different sources lies in the different identifiers used in individual data sources. We decided to use Ensembl protein ID as the protein identifier in CanProVar because the Ensembl database provides comprehensive mappings from Ensembl ID to IDs in other major databases. Moreover, Ensembl protein ID has been recommended as one of the standard gene identifiers by NCI's caBIG [Cimino, et al., 2009; von Eschenbach and Buetow, 2007]. To map crVARs from different sources onto Ensembl protein entries accurately, original protein sequences used in each data source were downloaded, including those from the SwissProt protein database (release 14.9) (http://www.uniprot.org/downloads), the Human CCDS protein database (ftp://ftp.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pub/CCDS/archive/Hs35.1/), and the RefSeq database (ftp://ftp.ncbi.nih.gov/refseq/H_sapiens/). To ensure data accuracy, we conservatively mapped all protein-coding variations onto Ensembl protein sequences in two steps. First, we mapped the protein IDs in external databases to Ensembl protein IDs based on the mapping tables provided by the Ensembl database. Next, we aligned mapped protein sequence pairs and eliminated those with different sequence length or those in which the variation annotation did not match the Ensembl protein sequence.

Validated human common SNPs in dbSNP version 129 were retrieved from BioMart [Smedley, et al., 2009]. We included only stop-gained, splice-site, and non-synonymous-coding SNPs for the construction of our database. Protein sequence variations derived from these SNPs are designated as non-cancer specific variations (ncsVARs) in the paper.

To facilitate the functional interpretation of the variations, information on genes, proteins, and protein interactions was also included in our database. Gene and protein attributes, including product description, gene name, chromosome location, Gene Ontology (GO) annotations, and identifier in external databases such as SwissProt, IPI, RefSeq, CDDS, and Entrez gene were downloaded from the Ensembl database (release 53) through the BioMart. GO slim annotations were downloaded from ftp://ftp.ebi.ac.uk/pub/databases/GO/goa/goslim/. Sequences and Pfam domains of Ensembl proteins were downloaded from the Ensembl FTP site: ftp://ftp.Ensembl.org/pub/current_mysql/homo_sapiens_core_53_36o/. Human protein interaction data were downloaded from seven databases including HPRD (v7; including HPRD_COMPLEX) [Keshava Prasad, et al., 2009], DIP [Xenarios, et al., 2002], MINT [Chatr-aryamontri, et al., 2007], MIPS [Mewes, et al., 2008], REACTOME [Matthews, et al., 2009] and INTACT [Kerrien, et al., 2007]. Downloaded data were further integrated to create a protein interaction network. Only literature-supported interactions were included in the network. The network was updated in June, 2008.

Database and web interface

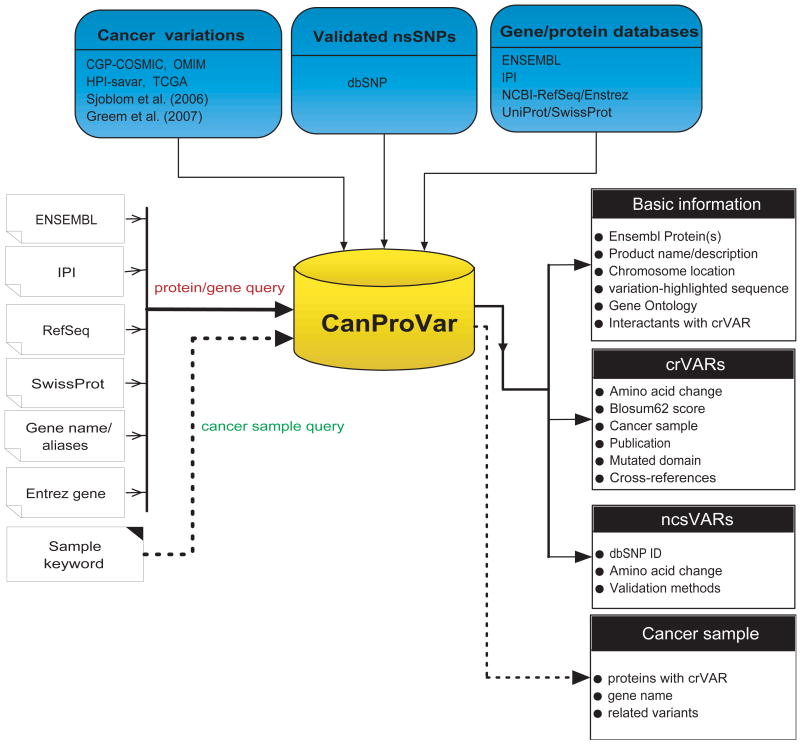

Fig. 1 shows the schematic overview of CanProVar, which includes two major components: a MySQL database for data storage and a web interface (http://bioinfo.vanderbilt.edu/canprovar) for querying and displaying the results.

Figure 1.

The system architecture of CanProVar

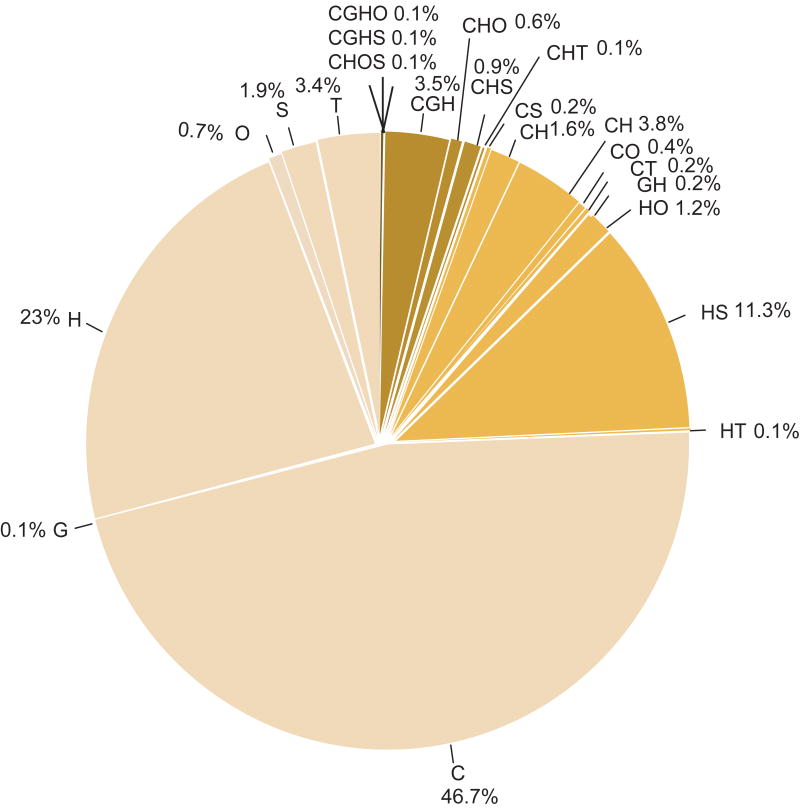

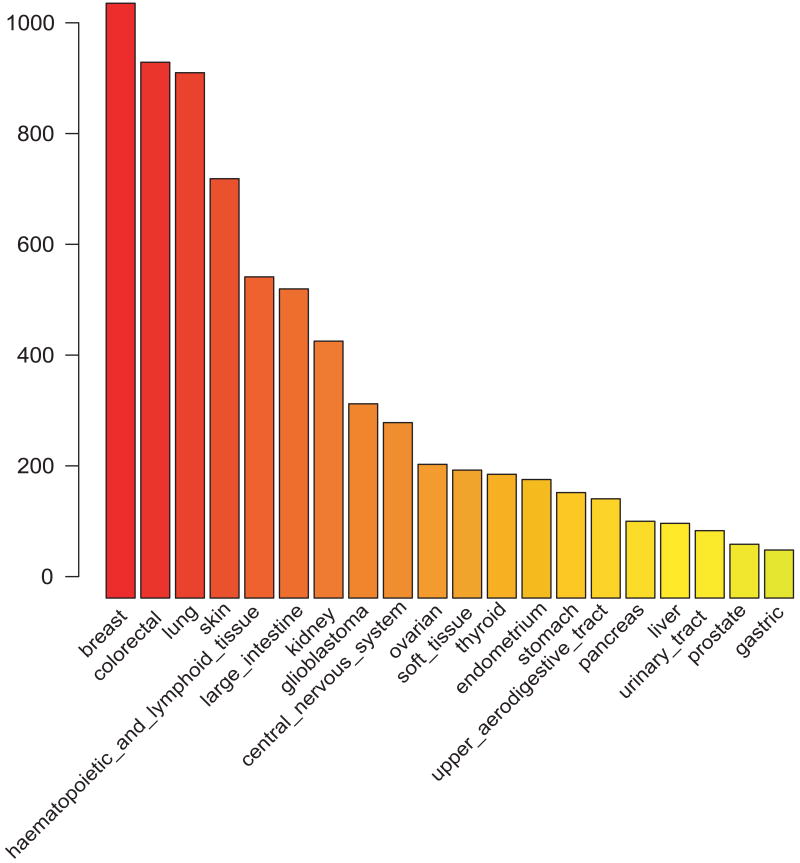

The current version of the CanProVar database contains 41,541 ncsVARs from 30,322 proteins and 8,570 crVARs from 2,921 proteins. On average, there are 2.5 crVARs /Mb in the human genome. Only 96 variations are in common between ncsVARs and crVARs. Following the name convention in dbSNP, each genomic sequence variation corresponding to a crVAR in CanProVar was given an identifier prefixed with “cs”. The proportion and frequencies of crVARs among different data sources are illustrated in Table 1 and Fig. 2. As shown in Fig. 2, less than one-fourth of the crVARs were reported in two or more sources, and none of them was shared by all six sources. Frequency statistics for tissue types in the current CanProVar database revealed that many more crVARs were identified in breast, colorectal, and lung cancers than other types of cancer (Fig. 3).

Figure 2.

Proportion of the CanProVar data from different data sources. The sources for cancer-related variations in the CanProVar database include databases COSMIC (C), OMIM (O), HPI (H), TCGA (T) and the publications from Greenman et al. (G) and Sjöblom et al. (S).

Figure 3.

Top 20 cancer types ranked by the amount of crVARs in CanProVar

The web interface was implemented in PHP. It allows protein- or sample-based queries (Fig. 1). In a protein-based query, the input to CanProVar can be protein identifiers in different databases including Ensembl, IPI, RefSeq, and Uniprot/SwissProt. Entrez gene ID and gene name/aliases can also be used for the query. As proteins in CanProVar are indexed by Ensembl protein ID, other IDs are first converted to Ensembl protein ID through a cross-reference table in the MySQL database. If a querying ID, like gene name, can be mapped to multiple Ensembl proteins, mapped proteins will be ranked by the number of crVARs and ncsVARs. The protein with the most variations will be selected for the primary output view, though links to alternative proteins are provided. To get comprehensive variation information for a given query ID, users are recommended to check all mapped Ensembl proteins individually.

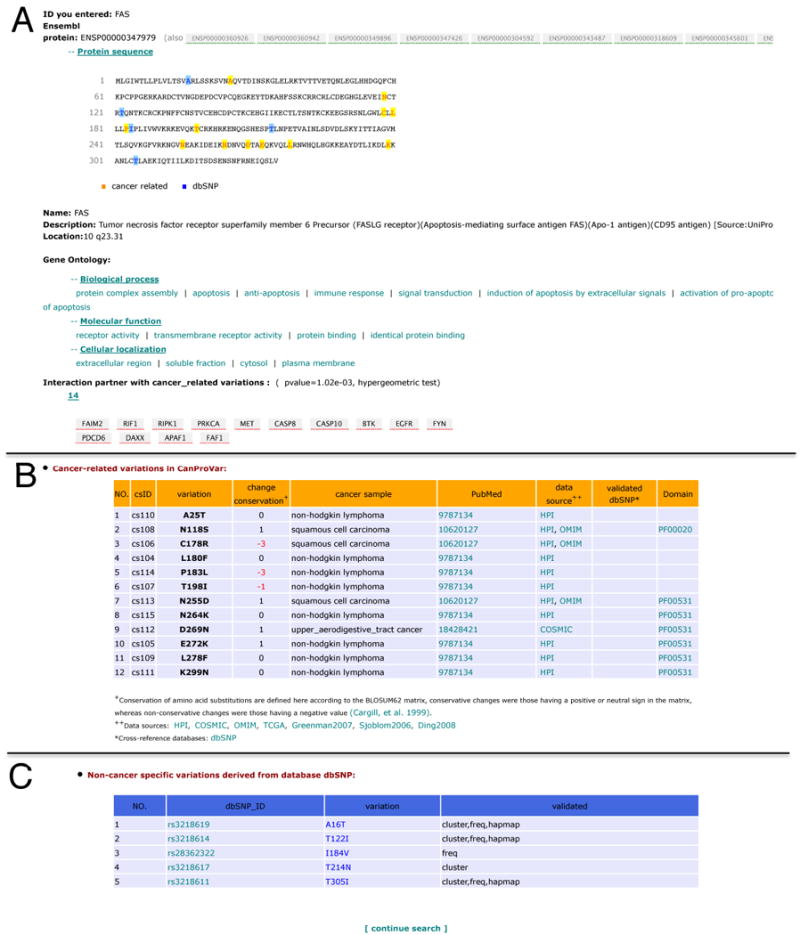

The output for a protein-based query includes three sections (Fig. 4). The first section provides basic information for the ID used for the query, including corresponding Ensembl protein ID(s), product name and description, chromosome location, variation-highlighted sequence, GO annotations, and the interaction partners with crVARs (Fig. 4A). The second section provides information on crVARs including individual cancer-related amino acid variations, related tumor or cell line samples, relevant publications, data sources, variation-containing domains, as well as cross-references to dbSNP if the variation is also reported in dbSNP (Fig. 4B). To provide preliminary information on the potential functional effect of an amino acid substitution, a BLOSUM62 score is given for each alteration. Amino acid substitutions with scores >=0 are classified as conservative and tolerated [Cargill, et al., 1999]. Substitutions with negative scores are classified as nonconservative ones. These substitutions are observed less frequently than expected by chance and are predicted as deleterious [Cargill, et al., 1999]. A hypertext link to the original database record is also provided if the information for an individual crVAR is available. The last section lists validated nsSNPs in the dbSNP database, with the dbSNP ID, amino acid alternation, and the validation method(s) (Fig. 4C). Cross-links to other resources such as GO, PubMed, Pfam, dbSNP are also available on the output page. Protein sequences with variation information can be downloaded from http://bioinfo.vanderbilt.edu/canprovar.

Figure 4.

Output view for a protein/gene-based query in CanProVar. The output view for a protein/gene-based query in CanProVar includes three sections: (A) basic information for the protein corresponded to the queried ID, (B) information on the cancer related variations, and (C) validated nsSNPs in the dbSNP database.

In a sample-based query, users can search the descriptions of cancer samples for specific terms such as “lung cancer” or “liver cancer”. CanProVar will identify all samples related to the search term and then report all proteins with crVARs detected in the samples. For instance, if a user wants to retrieve mutated proteins in breast cancer, a query in CanProVar using the term “breast cancer” will generate a report with 926 crPROs and their breast cancer-related variations.

Functional characteristics of known crVARs and crPROs

Biological processes and functions

crPROs in the database were classified based on their biological process and molecular function annotations according to the third annotation level of the slim GO. These crPROs take roles in various biological processes (Supp. Figure S1A), mainly including regulation of biological process, metabolism, response to stimulus, cell differentiation, and cellular physiological process. The most prominent function of the crPROs is protein binding (Supp. Figure S1B). Other major activities of crPROs include transferase activity, hydrolase activity, transcription factor activity, and receptor activity. Alterations in proteins with these functions have been widely reported in cancer studies [Baldwin, 2001; Baxter, et al., 2002; Clevenger, 2004; Feng, et al., 2009; Hengstler, et al., 1998; McIlwain, et al., 2006; Muller, et al., 2001]. As an example, mutations in the β-catenin (CTNNB1)-binding region of protein APC impair its tumor suppressor function by activating the downstream β-catenin-Tcf signaling in colorectal cancer [Morin, et al., 1997]. As another example, in prostate cancer cell lines, missense mutations in human protein PLXNB1 (Plexin-B1) hinder Rac and R-Ras binding and result in an increase in cell motility, invasion, adhesion, and lamellipodia extension [Wong, et al., 2007].

Chromosomal distribution

It has been reported that nsSNPs distribute non-randomly over human genes or the whole genome [Cargill, et al., 1999; Halushka, et al., 1999; Koboldt, et al., 2006; Ramensky, et al., 2002]. Therefore, we investigated the chromosome distribution of the crVARs in CanProVar. As shown in Supp. Figure S2, crVARs are present on all human chromosomes except for chromosome Y. crVARs distribute unequally over the genome, and cytogenetic bands with high-density of crVARs are highlighted in Supp. Figure S2.

The density of crVARs in crPROs is also highly varied, ranging from 1 to 331. Most crPROs also have ncsVARs, but correlation between the number of crVARs and that of ncsVARs is very weak, with a Pearson's correlation coefficient of 0.08. Interestingly, in the crPROs, crVARs outnumber ncsVARs (p = 2.2e-16, Wilcoxon signed-rank test) even though the number of crVARs is far less than that of the ncsVARs in the whole human proteome. An extreme example is the TP53 sequence in which 331 out of the 393 residues have crVARs while there are only 4 ncsVARs. Clustering of crVARs in crPROs might imply that instability of the cancer genomes affects whole coding regions of cancer genes rather than few specific positions.

Protein domains

Domains are basic evolutionary and functional units of proteins and most proteins have more than one domain [Fong, et al., 2007]. We showed that crVARs were not evenly distributed across human proteins and the whole genome. Here we further tested whether crVARs were enriched in certain protein domains. Specifically, we used the hypergeometric test to analyze whether a selected domain was enriched with crVARs (relative to non-crVARs), with respect to the expected fraction of crVARs in all protein domains. The p values generated by the hypergeometric test were further adjusted using the Benjamini and Hochberg correction [Benjamini and Hochberg, 1995] to account for multiple comparisons.

As listed in Table 2, twelve protein domains showed significant enrichment of crVARs (adjusted p value<0.01). These domains might represent functional units that are critical in tumorigenesis and tumor development. Therefore, we further tested whether these domains were over-represented in crPROs compared with the whole human proteome using the hypergeometric test followed by the Benjamini and Hochberg correction. As shown in Table 2, three of the crVAR-enriched domains were significantly over-represented in crPROs (adjusted p value < 0.01), including the Menin domain, the tyrosine kinase domain, and the SH2 domain. Menin is a well-known tumor suppressor whose loss of function causes cancer [Yokoyama and Cleary, 2008]. The protein kinase domain has been reported as the most common domain encoded by cancer genes [Futreal, et al., 2004]. Moreover, tyrosine kinase and SH2 domains function respectively as “writers” and “readers” of phospho-tyrosine modifications in phospho-tyrosine signaling, which is essential for cell–cell communication, mediating hormone, growth factor, immune, and adhesion-based signaling [Pincus, et al., 2008]. The activity and mutation of kinases in phospho-tyrosine signaling has been widely linked to diagnose and therapy of cancers [Blume-Jensen and Hunter, 2001; Dowell and Minna, 2005; Rikova, et al., 2007; Weinstein, 2002]. As an example, the cancer drug Gefitinib selectively inhibits the epidermal growth factor receptor's (EGFR) tyrosine kinase domain, while mutations in the tyrosine kinase domain have been found in multiple studies to significantly change the clinical response of cancer patients to the drug [Chou, et al., 2005; Paez, et al., 2004; Pao, et al., 2004].

Table 2. Protein domain with significant enrichment of cancer-related variations.

| No | Pfam | Name | Function | crVARs | p value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | PF00870 | P53 | DNA binding, transcription factor activity | 1,024 | 2.06E-71 |

| 2 | PF00782 | DSPc | protein tyrosine/serine/threonine phosphatase activity | 240 | 2.63E-27 |

| 3 | PF01847 | VHL | protein ubiquitination | 213 | 3.25E-26 |

| 4 | PF00071 | Ras | 250 | 3.19E-25 | |

| 5 | PF02460 | Patched | hedgehog receptor activity | 155 | 1.13E-23 |

| 6 | PF08477 | Miro | GTP binding, small GTPase mediated signal transduction | 237 | 1.32E-23 |

| 7 | PF03166* | MH2 | regulation of transcription, DNA-dependent | 135 | 2.34E-20 |

| 8 | PF07710 | P53_tetramer | zinc ion binding, transcription factor activity, negative regulation of cell growth | 76 | 1.27E-10 |

| 9 | PF05053* | Menin | 162 | 1.21E-06 | |

| 10 | PF07714* | Pkinase_Tyr | protein-tyrosine kinase activity, ATP binding | 588 | 1.16E-05 |

| 11 | PF00023 | Ank | 45 | 1.79E-03 | |

| 12 | PF00853 | Runt | DNA binding, transcription factor activity | 32 | 2.03E-03 |

Pfam domains that are significantly over-represented in the proteins with cancer-related variations (crVARs).

Protein interactions

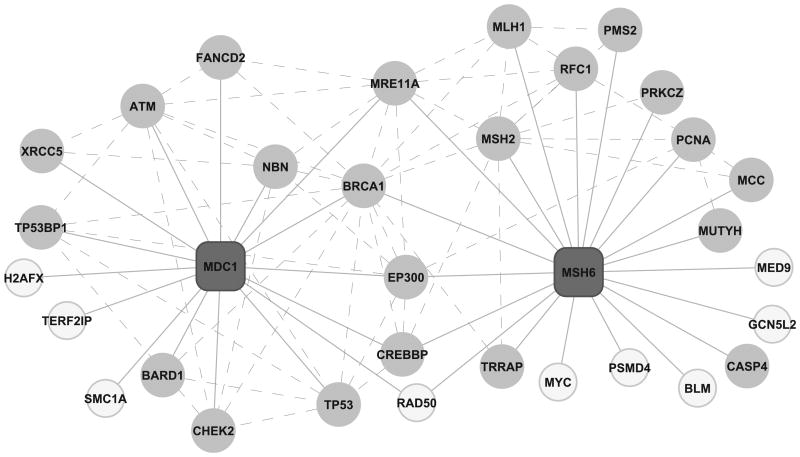

Most biological functions arise from interactions among proteins [Hartwell, et al., 1999]. Adding and breaking of connections is increasingly recognized as a regulatory motif for orchestrating signaling pathways in time and space [Kolch, 2000]. This regulatory motif has also been found in cancer networks. For example, mutations in either MSH6 or its interaction partners MSH2 and MLH1 increase the risk of double primary cancers of the colorectum and the endometrium [Cederquist, et al., 2004; Charames, et al., 2000]. Misssense mutations of either PIK3CA or its interaction partner EGFR have been associated with tumorigenesis [Di Nicolantonio, et al., 2008]. Moreover, human cancer cells carrying both EGFR and PIK3CA mutations strikingly abrogated the sensitization to cancer drugs such as gefitinib and erlotinib compared to those with EGFR mutation alone [Di Nicolantonio, et al., 2008]. These observations imply that specific interaction patterns or network characteristics of crPRO interactions might play important roles in the regulation of oncogenesis and the drug response of the tumors. Using an integrated protein interaction network with 10,349 proteins and 56,679 interactions, we analyzed the neighborhood of the crPROs to gain a global understanding of the characteristics of crPRO interactions. Specifically, for each crPRO, we used the hypergeometric test to evaluate the enrichment of crPROs among the direct neighbors of the crPRO, compared to the expected fraction of crPROs in all proteins in the network. Many proteins showed significant p values. As shown in Fig. 5, 12 out of the 16 neighbors of MDC1 (p = 1.25e-7 in the hypergeometric test) and 14 out of the 20 neighbors of MSH6 have cancer-related mutations (p=4.34e-8 in the hypergeometric test). To evaluate the overall enrichment of crPROs among the neighbors of all crPROs, we compared the enrichment p values for all crPROs to those for equal numbers of randomly sampled proteins using the Wilcoxon rank sum test. A p value of 9.72e-11 in the Wilcoxon rank sum test suggested that crPROs prefer to interact with other crPROs. Information on the crPRO neighbors of each crPRO is provided in CanProVar.

Figure 5.

Protein interaction partners of the cancer-related proteins MSH6 and MDC1. MSH6 and MDC1 are colored in dark grey. Their interaction partners are colored in light grey if they have cancer-related variations or white otherwise. Solid lines represent interactions between MSH6/MDC1 and their neighbors while dash lines represent interactions between two MSH6- or MDC1-neighbors that have cancer-related variations.

Discussion

Potential usage of CanProVar

CanProVar integrates information from existing genome variation databases and recent publications from large-scale cancer genome re-sequencing projects. It also provides a user-friendly interface for querying the database. Using CanProVar, researchers can get quick access to known cancer-related variations in protein sequences along with the cancer samples, relevant publications, data sources and other information such as variation-bearing domains, GO annotation, and interacting partners with crVARs.

Proteomics has become a promising avenue for better understanding of disease biology as well as the identification of disease biomarkers and therapeutic targets [Hondermarck, 2003]. CanProVar can serve as a useful tool for the identification of cancer-causative mutation or cancer-biomarker in human proteome, the exploration of mutant peptide-based vaccine for cancers [Toubaji, et al., 2008; Tsuruma, et al., 2005], the interpretation of differential peptide expression in shotgun proteomics that are possibly caused by sequence variations, and the explanation of unexpected observations in pull-down experiments for defining protein complexes. As an example, pull-down experiments in human tumor samples demonstrated that interactions between the oncoprotein MDM2 and the ribosomal protein L11 can be disrupted by missense mutations in MDM2, which help retain MDM2's full p53-suppressive function while escaping inhibition by L11 [Lindstrom, et al., 2007]. As another example, shotgun proteomics data analysis usually relies on database search and adding protein mutation information into the database can help identify mutated proteins [Schandorff, et al., 2007; Xi, et al., 2009].

Data quality and coverage

The dbSNP database defines any single nucleotide polymorphism as a SNP regardless of its allelic frequency. Although only validated nsSNPs of dbSNP were considered in CanProVar, allelic frequencies for most of the single amino acid alterations are not available. CanProVar includes both germline and somatic crVARs from all six data sources (Table 1). As shown in Figure 3, crVARs were found in most types of cancer cancers. The frequencies in breast, colorectal and lung cancer were much higher than in other types of cancers. Because the current knowledge on crVARs is far from being complete, it is unclear whether these frequency differences are related to the different mechanisms among the cancers or simply due to the unbalance of studies on different types of cancers.

Only approximately 25% of crVARs were supported by two or more data sources. The small overlap among the data sources suggests the incompleteness of individual sources. On the other hand, because each data source might give considerable false positives, caution needs to be taken with variations supported by only one data source. Ongoing large-scale cancer genome projects, such as the Cancer Genome Project (CGP) of the Sanger Institute and The TCGA project of the NCI and NHGRI could rapidly increase the variation coverage[TCGA, 2008]. We will continuously update the CanProVar database to ensure that we have the most accurate, complete, and up-to-date information available.

Annotation and nomenclature standard

Correct interpretation of the cancer-specific variation patterns requires accurate information on the variations, the method of detection, and the tumor sample. Moreover, for seamless integration of data from various data sources, standard nomenclature is critical. Currently, data standardization is not enforced in individual databases. For instance, some databases use “brain cancer” while others use “glioblastoma”. As CanProVar is based on the original data sources with limited manual curation, certain redundancies and ambiguities are inevitable. Recently, the Minimum Information about Somatic Mutation (MIASM) criteria was proposed to standardize the annotations and nomenclature for data related to somatic mutations in human cancers [Olivier, et al., 2009]. NCI's caBIG also proposed data standards for cancer biomedical informatics [Cimino, et al., 2009]. In the future, we will follow this data standard in data source selection and data reporting.

Interpretation of the characteristics of crVARs and crPROs

Based on the current data in CanProVar, we found that crVARs distributed unevenly on chromosomes and across different cancer types. Moreover, crVARs were likely to cluster in the crPROs and were statistically enriched in certain protein domains. However, special caution needs to be taken in interpreting these results because of the potential bias associated with the current data. For example, known cancer genes and hotspot regions were sequenced more often than unknown ones in some of our data sources. In addition, some cancer types were studied more often than others. Better understanding of these observations will be possible with the availability of more unbiased data from large-scale cancer genome projects.

We also found that crPROs tended to interact with each other in a protein interaction network. It is unclear whether these patterns exist in specific cancer genomes or appear individually in different cancer samples. It is also unclear whether the observed pattern is partially due to the incompleteness of the current protein interaction network because known cancer genes are more likely to be chosen for protein interaction studies. We believe that data collected on individuals from large populations and the improvement on the completeness of human protein interaction network will provide insight into these interesting and important questions.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health (NIH)/National Cancer Institute (NCI) through grant R01 CA126218 and the NIH/National Institute of General Medical Sciences (NIGMS) through grant R01 GM088822. We acknowledge Dr Dave Tabb for useful comments on this manuscript.

Footnotes

Supporting Information for this preprint is available from the Human Mutation editorial office upon request (humu@wiley.com)

References

- Baldwin AS. Control of oncogenesis and cancer therapy resistance by the transcription factor NF-kappaB. J Clin Invest. 2001;107(3):241–6. doi: 10.1172/JCI11991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bamford S, Dawson E, Forbes S, Clements J, Pettett R, Dogan A, Flanagan A, Teague J, Futreal PA, Stratton MR, et al. The COSMIC (Catalogue of Somatic Mutations in Cancer) database and website. Br J Cancer. 2004;91(2):355–8. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6601894. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baxter SW, Choong DY, Campbell IG. Microsomal epoxide hydrolase polymorphism and susceptibility to ovarian cancer. Cancer Lett. 2002;177(1):75–81. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3835(01)00782-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benjamini Y, Hochberg Y. Controlling the false discovery rate: a practical and powerful approach to multiple testing. J Royal Statist Soc B. 1995;57(1):289–300. [Google Scholar]

- Blume-Jensen P, Hunter T. Oncogenic kinase signalling. Nature. 2001;411(6835):355–65. doi: 10.1038/35077225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boeckmann B, Bairoch A, Apweiler R, Blatter MC, Estreicher A, Gasteiger E, Martin MJ, Michoud K, O'Donovan C, Phan I, et al. The SWISS-PROT protein knowledgebase and its supplement TrEMBL in 2003. Nucleic Acids Res. 2003;31(1):365–70. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkg095. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boeckmann B, Blatter MC, Famiglietti L, Hinz U, Lane L, Roechert B, Bairoch A. Protein variety and functional diversity: Swiss-Prot annotation in its biological context. C R Biol. 2005;328(10-11):882–99. doi: 10.1016/j.crvi.2005.06.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Botstein D, Risch N. Discovering genotypes underlying human phenotypes: past successes for mendelian disease, future approaches for complex disease. Nat Genet. 2003;33(Suppl):228–37. doi: 10.1038/ng1090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cargill M, Altshuler D, Ireland J, Sklar P, Ardlie K, Patil N, Shaw N, Lane CR, Lim EP, Kalyanaraman N, et al. Characterization of single-nucleotide polymorphisms in coding regions of human genes. Nat Genet. 1999;22(3):231–8. doi: 10.1038/10290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cederquist K, Emanuelsson M, Goransson I, Holinski-Feder E, Muller-Koch Y, Golovleva I, Gronberg H. Mutation analysis of the MLH1, MSH2 and MSH6 genes in patients with double primary cancers of the colorectum and the endometrium: a population-based study in northern Sweden. Int J Cancer. 2004;109(3):370–6. doi: 10.1002/ijc.11718. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chanock S. Candidate genes and single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) in the study of human disease. Dis Markers. 2001;17(2):89–98. doi: 10.1155/2001/858760. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Charames GS, Millar AL, Pal T, Narod S, Bapat B. Do MSH6 mutations contribute to double primary cancers of the colorectum and endometrium? Hum Genet. 2000;107(6):623–9. doi: 10.1007/s004390000417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chasman D, Adams RM. Predicting the functional consequences of non-synonymous single nucleotide polymorphisms: structure-based assessment of amino acid variation. J Mol Biol. 2001;307(2):683–706. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.2001.4510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chatr-aryamontri A, Ceol A, Palazzi LM, Nardelli G, Schneider MV, Castagnoli L, Cesareni G. MINT: the Molecular INTeraction database. Nucleic Acids Res. 2007;35(Database issue):D572–4. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkl950. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chou TY, Chiu CH, Li LH, Hsiao CY, Tzen CY, Chang KT, Chen YM, Perng RP, Tsai SF, Tsai CM. Mutation in the tyrosine kinase domain of epidermal growth factor receptor is a predictive and prognostic factor for gefitinib treatment in patients with non-small cell lung cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2005;11(10):3750–7. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-04-1981. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cimino JJ, Hayamizu TF, Bodenreider O, Davis B, Stafford GA, Ringwald M. The caBIG terminology review process. J Biomed Inform. 2009;42(3):571–80. doi: 10.1016/j.jbi.2008.12.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clevenger CV. Roles and regulation of stat family transcription factors in human breast cancer. Am J Pathol. 2004;165(5):1449–60. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)63403-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dantzer J, Moad C, Heiland R, Mooney S. MutDB services: interactive structural analysis of mutation data. Nucleic Acids Res. 2005;33(Web Server issue):W311–4. doi: 10.1093/nar/gki404. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Di Nicolantonio F, Arena S, Gallicchio M, Zecchin D, Martini M, Flonta SE, Stella GM, Lamba S, Cancelliere C, Russo M, et al. Replacement of normal with mutant alleles in the genome of normal human cells unveils mutation-specific drug responses. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105(52):20864–9. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0808757105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dowell JE, Minna JD. Chasing mutations in the epidermal growth factor in lung cancer. N Engl J Med. 2005;352(8):830–2. doi: 10.1056/NEJMe058033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Engle LJ, Simpson CL, Landers JE. Using high-throughput SNP technologies to study cancer. Oncogene. 2006;25(11):1594–601. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1209368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feng LY, Ou ZL, Wu FY, Shen ZZ, Shao ZM. Involvement of a novel chemokine decoy receptor CCX-CKR in breast cancer growth, metastasis and patient survival. Clin Cancer Res. 2009;15(9):2962–70. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-08-2495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fong JH, Geer LY, Panchenko AR, Bryant SH. Modeling the evolution of protein domain architectures using maximum parsimony. J Mol Biol. 2007;366(1):307–15. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2006.11.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fredman D, Sawyer SL, Stromqvist L, Mottagui-Tabar S, Kidd KK, Wahlestedt C, Chanock SJ, Brookes AJ. Nonsynonymous SNPs: validation characteristics, derived allele frequency patterns, and suggestive evidence for natural selection. Hum Mutat. 2006;27(2):173–86. doi: 10.1002/humu.20289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fredman D, Siegfried M, Yuan YP, Bork P, Lehvaslaiho H, Brookes AJ. HGVbase: a human sequence variation database emphasizing data quality and a broad spectrum of data sources. Nucleic Acids Res. 2002;30(1):387–91. doi: 10.1093/nar/30.1.387. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Futreal PA, Coin L, Marshall M, Down T, Hubbard T, Wooster R, Rahman N, Stratton MR. A census of human cancer genes. Nat Rev Cancer. 2004;4(3):177–83. doi: 10.1038/nrc1299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greenman C, Stephens P, Smith R, Dalgliesh GL, Hunter C, Bignell G, Davies H, Teague J, Butler A, Stevens C, et al. Patterns of somatic mutation in human cancer genomes. Nature. 2007;446(7132):153–8. doi: 10.1038/nature05610. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Halushka MK, Fan JB, Bentley K, Hsie L, Shen N, Weder A, Cooper R, Lipshutz R, Chakravarti A. Patterns of single-nucleotide polymorphisms in candidate genes for blood-pressure homeostasis. Nat Genet. 1999;22(3):239–47. doi: 10.1038/10297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamosh A, Scott AF, Amberger JS, Bocchini CA, McKusick VA. Online Mendelian Inheritance in Man (OMIM), a knowledgebase of human genes and genetic disorders. Nucleic Acids Res. 2005;33(Database issue):D514–7. doi: 10.1093/nar/gki033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Han A, Kang HJ, Cho Y, Lee S, Kim YJ, Gong S. SNP@Domain: a web resource of single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) within protein domain structures and sequences. Nucleic Acids Res. 2006;34(Web Server issue):W642–4. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkl323. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hartwell LH, Hopfield JJ, Leibler S, Murray AW. From molecular to modular cell biology. Nature. 1999;402(6761 Suppl):C47–52. doi: 10.1038/35011540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hengstler JG, Arand M, Herrero ME, Oesch F. Polymorphisms of N-acetyltransferases, glutathione S-transferases, microsomal epoxide hydrolase and sulfotransferases: influence on cancer susceptibility. Recent Results Cancer Res. 1998;154:47–85. doi: 10.1007/978-3-642-46870-4_4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoeijmakers JH. Genome maintenance mechanisms for preventing cancer. Nature. 2001;411(6835):366–74. doi: 10.1038/35077232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hondermarck H. Breast cancer: when proteomics challenges biological complexity. Mol Cell Proteomics. 2003;2(5):281–91. doi: 10.1074/mcp.R300003-MCP200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jegga AG, Gowrisankar S, Chen J, Aronow BJ. PolyDoms: a whole genome database for the identification of non-synonymous coding SNPs with the potential to impact disease. Nucleic Acids Res. 2007;35(Database issue):D700–6. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkl826. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karchin R, Diekhans M, Kelly L, Thomas DJ, Pieper U, Eswar N, Haussler D, Sali A. LS-SNP: large-scale annotation of coding non-synonymous SNPs based on multiple information sources. Bioinformatics. 2005;21(12):2814–20. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bti442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kerrien S, Alam-Faruque Y, Aranda B, Bancarz I, Bridge A, Derow C, Dimmer E, Feuermann M, Friedrichsen A, Huntley R, et al. IntAct--open source resource for molecular interaction data. Nucleic Acids Res. 2007;35(Database issue):D561–5. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkl958. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keshava Prasad TS, Goel R, Kandasamy K, Keerthikumar S, Kumar S, Mathivanan S, Telikicherla D, Raju R, Shafreen B, Venugopal A, et al. Human Protein Reference Database--2009 update. Nucleic Acids Res. 2009;37(Database issue):D767–72. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkn892. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koboldt DC, Miller RD, Kwok PY. Distribution of human SNPs and its effect on high-throughput genotyping. Hum Mutat. 2006;27(3):249–54. doi: 10.1002/humu.20286. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kolch W. Meaningful relationships: the regulation of the Ras/Raf/MEK/ERK pathway by protein interactions. Biochem J. 2000;351(Pt 2):289–305. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lindstrom MS, Jin A, Deisenroth C, White Wolf G, Zhang Y. Cancer-associated mutations in the MDM2 zinc finger domain disrupt ribosomal protein interaction and attenuate MDM2-induced p53 degradation. Mol Cell Biol. 2007;27(3):1056–68. doi: 10.1128/MCB.01307-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matthews L, Gopinath G, Gillespie M, Caudy M, Croft D, de Bono B, Garapati P, Hemish J, Hermjakob H, Jassal B, et al. Reactome knowledgebase of human biological pathways and processes. Nucleic Acids Res. 2009;37(Database issue):D619–22. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkn863. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McIlwain CC, Townsend DM, Tew KD. Glutathione S-transferase polymorphisms: cancer incidence and therapy. Oncogene. 2006;25(11):1639–48. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1209373. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mewes HW, Dietmann S, Frishman D, Gregory R, Mannhaupt G, Mayer KF, Munsterkotter M, Ruepp A, Spannagl M, Stumpflen V, et al. MIPS: analysis and annotation of genome information in 2007. Nucleic Acids Res. 2008;36(Database issue):D196–201. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkm980. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morin PJ, Sparks AB, Korinek V, Barker N, Clevers H, Vogelstein B, Kinzler KW. Activation of beta-catenin-Tcf signaling in colon cancer by mutations in beta-catenin or APC. Science. 1997;275(5307):1787–90. doi: 10.1126/science.275.5307.1787. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muller A, Homey B, Soto H, Ge N, Catron D, Buchanan ME, McClanahan T, Murphy E, Yuan W, Wagner SN, et al. Involvement of chemokine receptors in breast cancer metastasis. Nature. 2001;410(6824):50–6. doi: 10.1038/35065016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O'Donovan C, Apweiler R, Bairoch A. The human proteomics initiative (HPI) Trends Biotechnol. 2001;19(5):178–81. doi: 10.1016/s0167-7799(01)01598-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olivier M, Petitjean A, Teague J, Forbes S, Dunnick JK, den Dunnen JT, Langerod A, Wilkinson JM, Vihinen M, Cotton RG, et al. Somatic mutation databases as tools for molecular epidemiology and molecular pathology of cancer: proposed guidelines for improving data collection, distribution, and integration. Hum Mutat. 2009;30(3):275–82. doi: 10.1002/humu.20832. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paez JG, Janne PA, Lee JC, Tracy S, Greulich H, Gabriel S, Herman P, Kaye FJ, Lindeman N, Boggon TJ, et al. EGFR mutations in lung cancer: correlation with clinical response to gefitinib therapy. Science. 2004;304(5676):1497–500. doi: 10.1126/science.1099314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pao W, Miller V, Zakowski M, Doherty J, Politi K, Sarkaria I, Singh B, Heelan R, Rusch V, Fulton L, et al. EGF receptor gene mutations are common in lung cancers from “never smokers” and are associated with sensitivity of tumors to gefitinib and erlotinib. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004;101(36):13306–11. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0405220101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pincus D, Letunic I, Bork P, Lim WA. Evolution of the phospho-tyrosine signaling machinery in premetazoan lineages. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105(28):9680–4. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0803161105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramensky V, Bork P, Sunyaev S. Human non-synonymous SNPs: server and survey. Nucleic Acids Res. 2002;30(17):3894–900. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkf493. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reumers J, Schymkowitz J, Ferkinghoff-Borg J, Stricher F, Serrano L, Rousseau F. SNPeffect: a database mapping molecular phenotypic effects of human non-synonymous coding SNPs. Nucleic Acids Res. 2005;33(Database issue):D527–32. doi: 10.1093/nar/gki086. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rhee H, Lee JS. MedRefSNP: a database of medically investigated SNPs. Hum Mutat. 2009;30(3):E460–6. doi: 10.1002/humu.20914. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rikova K, Guo A, Zeng Q, Possemato A, Yu J, Haack H, Nardone J, Lee K, Reeves C, Li Y, et al. Global survey of phosphotyrosine signaling identifies oncogenic kinases in lung cancer. Cell. 2007;131(6):1190–203. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.11.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schandorff S, Olsen JV, Bunkenborg J, Blagoev B, Zhang Y, Andersen JS, Mann M. A mass spectrometry-friendly database for cSNP identification. Nat Methods. 2007;4(6):465–6. doi: 10.1038/nmeth0607-465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sjoblom T, Jones S, Wood LD, Parsons DW, Lin J, Barber TD, Mandelker D, Leary RJ, Ptak J, Silliman N, et al. The consensus coding sequences of human breast and colorectal cancers. Science. 2006;314(5797):268–74. doi: 10.1126/science.1133427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smedley D, Haider S, Ballester B, Holland R, London D, Thorisson G, Kasprzyk A. BioMart--biological queries made easy. BMC Genomics. 2009;10:22. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-10-22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stenson PD, Ball EV, Mort M, Phillips AD, Shiel JA, Thomas NS, Abeysinghe S, Krawczak M, Cooper DN. Human Gene Mutation Database (HGMD): 2003 update. Hum Mutat. 2003;21(6):577–81. doi: 10.1002/humu.10212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sunyaev S, Ramensky V, Koch I, Lathe W, 3rd, Kondrashov AS, Bork P. Prediction of deleterious human alleles. Hum Mol Genet. 2001;10(6):591–7. doi: 10.1093/hmg/10.6.591. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- TCGA CGARN. Comprehensive genomic characterization defines human glioblastoma genes and core pathways. Nature. 2008;455(7216):1061–8. doi: 10.1038/nature07385. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Toubaji A, Achtar M, Provenzano M, Herrin VE, Behrens R, Hamilton M, Bernstein S, Venzon D, Gause B, Marincola F, et al. Pilot study of mutant ras peptide-based vaccine as an adjuvant treatment in pancreatic and colorectal cancers. Cancer Immunol Immunother. 2008;57(9):1413–20. doi: 10.1007/s00262-008-0477-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trovo-Marqui AB, Tajara EH. Neurofibromin: a general outlook. Clin Genet. 2006;70(1):1–13. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-0004.2006.00639.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsuruma T, Hata F, Furuhata T, Ohmura T, Katsuramaki T, Yamaguchi K, Kimura Y, Torigoe T, Sato N, Hirata K. Peptide-based vaccination for colorectal cancer. Expert Opin Biol Ther. 2005;5(6):799–807. doi: 10.1517/14712598.5.6.799. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uzun A, Leslin CM, Abyzov A, Ilyin V. Structure SNP (StSNP): a web server for mapping and modeling nsSNPs on protein structures with linkage to metabolic pathways. Nucleic Acids Res. 2007;35(Web Server issue):W384–92. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkm232. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- von Eschenbach AC, Buetow K. Cancer Informatics Vision: caBIG. Cancer Inform. 2007;2:22–4. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Z, Moult J. SNPs, protein structure, and disease. Hum Mutat. 2001;17(4):263–70. doi: 10.1002/humu.22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weinstein IB. Cancer. Addiction to oncogenes--the Achilles heal of cancer. Science. 2002;297(5578):63–4. doi: 10.1126/science.1073096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wong OG, Nitkunan T, Oinuma I, Zhou C, Blanc V, Brown RS, Bott SR, Nariculam J, Box G, Munson P, et al. Plexin-B1 mutations in prostate cancer. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104(48):19040–5. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0702544104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xenarios I, Salwinski L, Duan XJ, Higney P, Kim SM, Eisenberg D. DIP, the Database of Interacting Proteins: a research tool for studying cellular networks of protein interactions. Nucleic Acids Res. 2002;30(1):303–5. doi: 10.1093/nar/30.1.303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xi H, Park J, Ding G, Lee YH, Li Y. SysPIMP: the web-based systematical platform for identifying human disease-related mutated sequences from mass spectrometry. Nucleic Acids Res. 2009;37(Database issue):D913–20. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkn848. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yip YL, Scheib H, Diemand AV, Gattiker A, Famiglietti LM, Gasteiger E, Bairoch A. The Swiss-Prot variant page and the ModSNP database: a resource for sequence and structure information on human protein variants. Hum Mutat. 2004;23(5):464–70. doi: 10.1002/humu.20021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yokoyama A, Cleary ML. Menin critically links MLL proteins with LEDGF on cancer-associated target genes. Cancer Cell. 2008;14(1):36–46. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2008.05.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.