Abstract

The interactions of nitrogen monoxide (•NO; nitric oxide) with transition metal centers continue to be of great interest, in part due to their importance in biochemical processes. Here, we describe •NO(g) reductive coupling chemistry of possible relevance to that process (i.e., nitric oxide reductase (NOR) biochemistry) which occurs at the heme/Cu active site of cytochrome c oxidases (CcOs). In this report, heme/Cu/•NO(g) activity is studied using 1:1 ratios of heme and copper complex components, (F8)Fe (F8 = tetrakis(2,6-difluorophenyl)porphyrinate(2-)) and [(tmpa)CuI(MeCN)]+ (TMPA = tris(2-pyridylmethyl)amine). The starting point for heme chemistry is the mononitrosyl complex (F8)Fe(NO) (λmax = 399 (Soret), 541 nm in acetone). Variable temperature 1H- and 2H-NMR spectra reveal a broad peak at δ = 6.05 ppm (pyrrole) at RT, which gives rise to asymmetrically split pyrrole peaks at 9.12 and 8.54 ppm at −80°C. A new heme dinitrosyl species, (F8)Fe(NO)2, obtained by bubbling (F8)Fe(NO) with •NO(g) at −80 °C, could be reversibly formed, as monitored by UV-vis (λmax = 426 (Soret), 538 nm in acetone), EPR (silent), and NMR spectroscopies, i.e. the mono-NO complex was regenerated upon warming to RT. (F8)Fe(NO)2 reacts with [(tmpa)CuI(MeCN)]+ and two equiv of acid to give [(F8)FeIII]+, [(tmpa)CuII(solvent)]2+ and N2O(g), fitting the stoichiometric •NO(g) reductive coupling reaction: 2 •NO(g) + FeII + CuI + 2 H+ → N2O(g) + FeIII + CuII + H2O, equivalent to one enzyme turnover. Control reaction chemistry shows that both iron and copper centers are required for the NOR type chemistry observed, and that if acid is not present, half the •NO is trapped as a (F8)Fe(NO) complex, while the remaining nitrogen monoxide undergoes copper complex promoted disproportionation chemistry. As part of this study, [(F8)FeIII]SbF6 was synthesized and characterized by X-ray crystallography, along with EPR (77 K: g = 5.84 and 6.12 in CH2Cl2 and THF, respectively) and variable temperature NMR spectroscopies. These structural and physical properties suggest that at RT this complex consists of an admixture of high and intermediate spin states.

Introduction

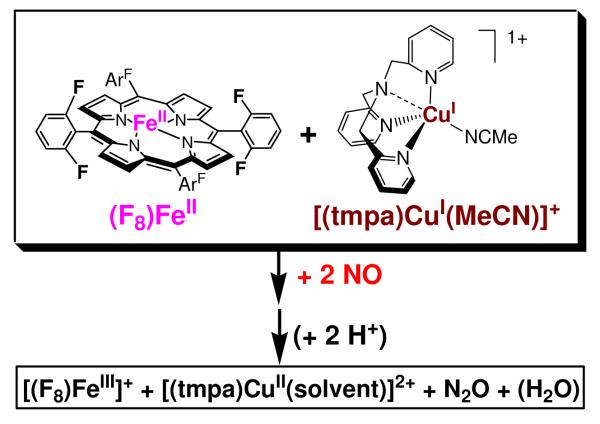

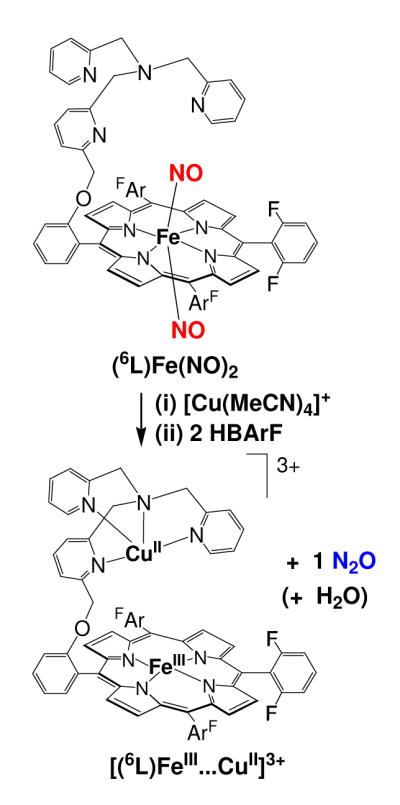

In this report, we describe the reductive coupling of two mole-equiv nitrogen monoxide (•NO(g); nitric oxide) to nitrous oxide (N2O(g)), 2 •NO(g) + 2 H+ + 2 e− → N2O(g) + H2O, mediated by a heme plus copper complex in the presence of acid. The particular compounds employed and the overall reaction discussed is shown in Scheme 1. This follows our previous paper1 on similar chemistry carried out by a binuclear heme/Cu assembly possessing a binucleating ligand. That was the first example of such chemistry with heme/Cu, modeling the heterobinuclear center present at the active site of cytochrome c oxidase (CcO).

Scheme 1.

In fact, bacterial •NO-reductases (NORs) effect this reductive coupling of •NO and these have a related active site, a heme with proximate non-heme iron metal center.2-4 Actually, these two enzyme classes are evolutionarily related.5,6 The heme/M (M = Fe or Cu) centers both possess a number of conserved histidines: one is a proximal ligand for the heme of the binuclear heme/M center (as in hemoglobin/myoglobin) and three other histidine imidazole donors bind to the so-called CuB (in CcOs) and FeB (in NORs). NORs are found in anaerobic denitrifiers which instead of using dioxygen to pass electrons obtained from metabolic processes, use nitrogen oxides. The following biochemical pathway comes into play: NO3 − → NO2 − → •NO → N2O → N2. 4,7 Each reaction step is catalyzed by metalloproteins.

In the penultimate step in the mitrochondrial electron-transport chain, CcOs catalyze the four-electron reduction of dioxygen to water; this couples to inner-membrane proton translocation and a proton/charge gradient which powers the subsequent synthesis of ATP.8-10 However, certain types of CcOs, such as ba3 and caa3 oxidases from Thermus thermophilus, cbb3 oxidase from Pseudomonas stutzeri and bo3 from Escherichia coli also carry out nitrogen monoxide reductive coupling, i.e., NOR chemistry,11 and this subject has recently received considerable attention from the biophysical and computational research communities.2,11-14 Lu and co-workers15 have investigated such chemistry coming from a designed/modified small protein (myoglobin) model system. Here, a CuB center was designed and integrated into a wild-type myoglobin leading to the formation of a protein with a binuclear heme/Cu center, which with an added external reductant was able to catalyze the •NO(g) to N2O conversion. Yet, we are far from having a sufficient understanding of the underlying metal/•NO(g) and metal ion mediated NO-NO coupling chemistry.

In addition, the interaction of •NO(g) with CcOs is of considerable importance.16-22 Nitrogen monoxide reversibly inhibits mitochondrial respiration by binding to the CcO metal centers, influencing the regulation of mitochondrial reactive oxygen species generation and preventing cytochrome c release. There are also literature discussions concerning the reaction of •NO(g) with CcO intermediates leading to its oxidation to nitrite;23 this process may be biologically important for the purpose of generating pools of the latter which may later be reduced back to NO (perhaps also by reduced CcO).18,24 The interplay of •NO and O2 chemistry at CcO metal centers, and the control of relative levels of •NO (and nitrite) and O2 (and rates of respiration) are biologically critical processes.

Thus, the reductive coupling of nitric oxide is of chemical and biological interest and the study of systems undergoing this chemistry is part of our larger research program in the investigation of small molecule gases (O2, NO, CO) and their interactions with heme/M (M = Fe or Cu) binuclear assemblies.1,10,25-27 As stated, here we report on a system employing heme/Cu complexes, in fact component heme and copper complexes along with the presence of acid which function together to facilitate the stoichiometric •NO(g) coupling reduction to N2O(g), Scheme 1. As part of the description and chemistry involved, we describe the generation and some of the physical properties of a new complex, a heme dinitrosyl species (F8)Fe(NO)2. Also, the X-ray structure and spectroscopic characterization of a new heme-iron(III) complex, [(F8)FeIII](SbF6) (F8 = tetrakis(2,6-difluorophenyl)porphyrinate(2-)) are reported.

Experimental Section

Materials and Methods

Unless otherwise stated, all solvents and chemicals used were of commercially available analytical grade. Nitrogen monoxide (•NO) gas was obtained from Matheson Gases and passed multiple times through a column containing KOH pellets and through an liquid N2 cooled trap to remove impurities. See also the Supporting Information of 28. The purified •NO(g) was passed into a Schlenk flask placed in liquid N2, to freeze. For use in reactions, this frozen gas was briefly warmed with the acetone/dry ice bath (−78 °C) and allowed to pass into an evacuated Schlenk flask (typically 50 mL) fitted with a septum. Addition of •NO(g) to metal complex solutions was effected by transfer via a three-way long syringe needle. Dinitrogen oxide (N2O) gas was purchased from Airgas as a custom mixture, at a concentration of 250 ppm, balanced with dinitrogen at 1 atm. Dichloromethane (CH2Cl2; DCM), acetonitrile (MeCN), methanol (MeOH) and pentane were used after passing through a 60-cm long column of activated alumina (Innovative Technologies, Inc.) under argon. Tetrahydrofuran (THF) and acetone were purified and dried by distillation from sodium/benzophenone ketyl. Preparation and handling of air sensitive compounds were performed under an argon atmosphere using standard Schlenk techniques or in an MBraun Labmaster 130 inert atmosphere (<1 ppm O2, <1 ppm H2O) drybox filled with nitrogen gas. Deoxygenation of solvents was effected by either repeated freeze/pump/thaw cycles or bubbling with argon for 30 - 45 minutes.

UV-Vis spectra were recorded on a Hewlett-Packard Model 8453A diode array spectrophotometer equipped with a two-window quartz H.S. Martin Dewar filled with cold MeOH (25 °C to −85 °C) maintained and controlled by a Neslab VLT-95 low temp circulator. Spectrophotometer cells used were made by Quark Glass with column and pressure/vacuum side stopcock and 1 cm path length. Electron paramagnetic resonance (EPR) spectra were recorded on a Bruker EMX spectrometer controlled with a Bruker ER 041 X G microwave bridge operating at X-band (~9.4 GHz). ESI mass spectra were acquired using a Finnigan LCQDeca ion-trap mass spectrometer equipped with an electrospray ionization source (Thermo Finnigan, San Jose, CA). The heated capillary temperature was 250 °C and the spray voltage was 5 kV. Gas chromatography analysis was performed on a Varian CP-3800 instrument equipped with a 1041 manual injector, electron conductivity detector, and a 25m 5Å molecular sieve capillary column. Ion chromatography analysis (ICA). was performed on a Dionex DX-120 Ion chromatograph, with an AS40 automated sampler, and an IonPac AS14 (4*250 mm) column. The eluent was 3.5 mM Na2CO3 along with 1.0 mM NaHCO3. See below for the procedure for generating a sample for ICA. Infrared spectra (IR) were recorded on a Bruker Vector 22 instrument controlled by OPUS-NT software at room temperature.

Low-Temperature NMR Spectroscopic Measurements

Multinuclear (1H and 2H) NMR spectroscopic measurements were performed at various temperatures under a N2 atmosphere. 1H-NMR spectra were measured on a Bruker 400 MHz spectrometer while 2H-NMR spectra were measured on a Varian Mercury 500 MHz spectrometer. Chemical shifts were reported as δ values relative to an internal standard of the deuterated solvent being used. Measurement of spectra for the mono- and dinitrosyl heme complexes were carried out in septum-capped NMR tubes, and •NO(g) was added via an air-tight syringe to −78 °C solutions.

X-ray Structure Determination

X-ray diffraction was performed at the facility at the chemistry department of Johns Hopkins University. The X-ray intensity data were measured on an Oxford Diffraction Xcalibur3 system equipped with a graphite monochromator and an Enhance (Mo) X-ray Source (λ = 0.71073Å) operated at 2 kW power (50 kV, 40 mA) and a CCD detector. The frames were integrated, scaled and corrected for absorption using the Oxford Diffraction CrysAlisPRO software package.

Syntheses

(F8)FeCl (F8 = tetrakis(2,6-difluorophenyl)porphyrinate(2-)),29 (F8-d8)FeCl,30 (F8)FeII,30 (F8-d8)FeII,30 (F8)Fe(NO),1 tris(2-pyridylmethyl)amine (TMPA),31 [(tmpa)CuI(MeCN)]PF6,31 [(tmpa)CuI(MeCN)]B(C6F5)4, 32 [CuI(MeCN)4]SbF6, 33 and [H(C2H5OC2H5)2][B(C6F5)4] (HBArF)34 were prepared from literature reports.

Synthesis of (THF)(F8)Fe(NO)

A solution of 75 mg (0.092 mmol) (F8)FeII in 5 mL THF was cooled to −78 °C using a dry ice/acetone bath. Under Ar, 20 mL •NO(g) at ~ 1 atm was added using a gas-tight syringe. The solution was stirred for 30 min and degassed heptane was added until a solid product precipitated. The brown-red solid obtained (60 mg, 77%) was filtered and dried under vacuum and then stored in the drybox. UV-Vis (λmax, nm): THF, 410 (Soret), 546. IR (cm−1) νNO = 1670 in THF. EPR spectrum, see Results and Discussion. Anal. Calcd. For {(THF)(F8)Fe(NO)•THF}; C52H36F8FeN5O3: C, 63.30; H, 3.68; N, 7.10. Found: C, 62.76; H, 3.60; N, 6.94.

Synthesis of [(F8)FeIII]SbF6

This synthesis is a modified version of that reported earlier for tetraphenylporphyrin.35 In a glove box filled with N2, (F8)FeCl (0.30 g, 0.354 mmol) and AgSbF6 (0.128 g, 0.373 mmol) were weighed and transferred to a Schlenk flask equipped with a stir bar. The solid materials were dissolved in 35 mL of freshly distilled THF and the solution was stirred at room temperature for 1 hour under reduced light. The reaction mixture was then filtered to remove AgCl. The filtrate was dried in vacuo, redissolved in 7 mL CH2Cl2, and precipitated twice with addition of 80 mL pentane, yielding a purple powder (250 mg, 83 %). UV-vis (λmax, nm): CH2Cl2, 328, 394 (Soret), 512; THF, 328, 394 (Soret), 510. IR (Nujol, cm−1) νSbF6 = 657 cm−1. EPR spectrum at 77 K: g = 5.84 (in DCM); g = 6.12 (in THF). ESI-MS: (812.5, (F8)Fe). 1H-NMR (CD2Cl2): δ 27.2 and 11.6 (8 pyrrole), 10.2 (4 para), 9.4 (8 meta); 1H-NMR (THF-d8): δ 54.7 and14.8 (8 pyrrole), 10.4 (4 para), 9.3 (8 meta). Anal. Calcd. For {(F8)FeSbF6•1.5CH2Cl2}; C45.5H23Cl3F14FeN4Sb: C, 46.48; H, 1.97; N, 4.75. Found: C, 46.38; H, 2.12; N, 4.66. Crystals, suitable for X-ray diffraction, were obtained by layering a concentrated tetrahyrdrofuran solution of [(F8)FeIII]SbF6 with pentane. The purple colored X-ray-quality crystals are formulated as [(F8)FeIII(THF)2]SbF6. See Results and Discussion for further information.

Synthesis of [(tmpa)CuII(MeCN)](ClO4)2

TMPA (1.51 g, 5.20 mmol) and Cu(ClO4)2•6H2O (1.93 g, 5.21 mmol) were dissolved in a total of 40 mL CH3CN and allowed to stir for 30 min whereupon a dark blue solution developed. Diethyl ether (90 mL) was added to give a crude precipitate. Recrystallization of this solid from CH3CN/ether and drying in vacuo gave a light blue powder in a yield of 86% (2.66 g). Anal. Calcd. for [(tmpa)CuII(MeCN)](ClO4)2; C20H21Cl2CuN5O8: C, 40.45; H, 3.56; N, 11.79. Found: C, 40.55; H, 3.53; N, 11.80. UV-vis (CH3CN, λmax, nm (ε, M−1cm−1 )): 255 (14700), 855 (254). EPR spectrum in acetone at 77 K (see Figure S1): g˔ = 2.22, gǁ = 2.02, A˔ = 105 G, Aǁ = 71 G.

Synthesis of [(tmpa)CuII(NO2)]PF6

To a 100 mL Schlenk flask equipped with a magnetic stir bar was added 200 mg [(tmpa)CuI(MeCN)]PF6 in degassed CH3CN/THF (50:50) under a N2 atmosphere. The reaction flask was incubated in an acetone/dry ice bath. Excess •NO(g) was bubbled through this solution and the reaction mixture was allowed to stir for 30 min, with the color turning from yellow to purple. The solution was warmed to RT with its color turning to green, and this was kept stirring for 2 hours. Solvents were removed under reduced pressure and then recrystallization of the green solid from CH3CN/ether gave a green microcrystalline solid (75%). IR (in DCM, cm−1) νas (NO2)= 1390, νas (NO2)= 1330. UV-vis (λmax, nm, in CH2Cl2): 301, 415 (see Figure S2). EPR spectrum in acetone at 77 K (see Figure S3): g˔ = 2.21, gǁ = 2.01, A˔ = 84 G, Aǁ = 80 G. Anal. Calcd. For [(tmpa)CuII(NO2)]PF6; C18H18CuF6N5O2P: C, 39.68; H, 3.33; N, 12.85. Found: C, 39.76; H, 3.50; N, 12.27. Nitrite (NO2−) was the only detectable ion in the green solid as determined using ion chromatographic analysis (ICA). See below for the procedure for generating a sample for ICA.

Synthesis of [(tmpa)CuI(MeCN)]SbF6

This synthesis followed a procedure similar to that reported earlier for [(tmpa)CuI(MeCN)4]PF6. 31 A solution of 200 mg (0.689 mmol) of TMPA ligand in 10 mL distilled CH3CN was added to 319 mg (0.689 mmol) of [Cu(CH3CN)4]SbF6 in a 100 mL Schlenk flask in the glove box; the solution was stirred for one hour. Afterwards, 75 mL diethyl ether was added to the bright orange solution until a slight cloudiness was observed to develop. The solution was filtered through a medium-porosity frit, and the compound obtained was recrystallized from CH3CN/ether. The precipitate formed was dried under vacuum leading to a yellow-orange solid (78%). 1H-NMR (CD3CN): δ 8.93 (br, 3H), 7.83 (m, 3 H), 7.50 (br, 6 H), ca. 4.3 (v br, 6 H), 2.01 (s, 3 H, CH3CN).

Synthesis of [(tmpa)CuII(NO2)]SbF6

To a 100 mL Schlenk flask equipped with magnetic stir bar was added 300 mg [(tmpa)CuI(MeCN)]SbF6 in degassed CH3CN/THF (50:50) under a N2 atmosphere. The reaction flask was then incubated in an acetone/dry ice bath and the solution bubbled with excess NO(g). The reaction mixture was allowed to stir for 30 min with the color turning from yellow to purple. Subsequently the closed system warmed to RT, now turning to green, and this solution was stirred at RT for 2 hours. Solvents were removed under reduced pressure and recrystallization of the resulting solid from CH3CN/ether gave a green microcrystalline solid [(tmpa)CuII(NO2)]SbF6 (70% yield). IR (in CH2Cl2, cm−1) νas(NO2)= 1390, νas (NO2)= 1330. Anal. Calcd. For [(tmpa)CuII(NO2)]SbF6; C18H18CuF6N5O2Sb: C, 34.01; H, 2.85; N, 11.02. Found: C, 33.72; H, 2.80; N, 10.58. UV-Vis (λmax, nm, in CH2Cl2): 301, 415. Nitrite (NO2 −) was the only ion detected following ion chromatography analysis on this green solid. See below for the procedure for generating a sample for ICA.

Generation of (F8)Fe(NO)2

A 5 mL distilled acetone solution of (F8)Fe(NO) (5×10−6 mol/L) was taken in a UV-Vis cuvette assembly under argon; it was cooled to −78 °C and an initial spectrum was recorded. Excess •NO(g) was bubbled through the cold solution using a three-way needle syringe, and the new spectrum (of (F8)Fe(NO)2) was recorded, λmax = 426 (Soret), 538 nm. Additional bubbling with •NO(g) did not change the spectrum further. This resulting species (F8)Fe(NO)2 released NO to form (F8)Fe(NO) upon warming to RT., and (F8)Fe(NO)2 was regenerated when cooling to −80 °C or re-adding more NO(g). The other protocol for (F8)Fe(NO)2 generation was bubbling excess •NO(g) into the reduced complex (F8)FeII at −80 °C, while (F8)FeNO was formed if •NO(g) reacted with (F8)FeII at RT. 1H-NMR (CD2Cl2): δ 9.13 and 8.93 (8 pyrrole), 7.84 (4 para), 7.45 (8 meta). EPR spectrum in acetone at 77 K: silent. The related deuterated complex, (F8-d8)Fe(NO)2, was generated in the similar manner, except starting with (F8-d8)Fe(NO). (F8-d8)Fe(NO) was synthesized from (F8-d8)FeII nitrosylation by bubbling •NO(g) through the (F8-d8)FeII solution (in CH2Cl2) and removal of excess •NO(g) and solvents to yield a purple solid.

Titration (F8)Fe(NO)2 with (F8)FeII

(F8)FeII (0.0019 g, 0.0023 mmol) was dissolved in 100 mL of deaerated THF inside the glove box. From the red solution, 10 mL was transferred into a Schlenk flask and and under an Ar atmosphere on the bench-top this was cooled to −78 °C and a spectrum recorded {λmax = 422 (Soret), 542 nm}. Afterwards excess •NO(g) was bubbled through this cold solution using a three-way long needle syringe, the resulting new spectrum of the orange product (F8)Fe(NO)2 was recorded, {λmax = 410 (Soret), 540 nm}. Additional bubbling with •NO(g) did not change the spectrum further. The cold mixture was then purged with an Ar flow for 1 minute, and the entire flask was evacuated and refilled with Ar three times to remove the excess •NO(g). There was no spectral change upon excess •NO(g) removal. Approximately one equivalent of (F8)FeII was added to the cold solution by transferring 10 mL of the cold (−78 °C) (F8)FeII stock solution in THF with a cannula technique. At − 78 °C, the spectrum indicated it was a mixture of mononitrosyl, dinitrosyl and (F8)FeII. However, upon warming to RT, only one product was present, (THF)(F8)Fe(NO), {λmax = 410 (Soret), 546 nm} (see Figure S4). Based on the known extinction coefficients for (THF)(F8)Fe(NO) {λmax = 410 nm (Soret), ε = 176,000 M−1cm−1; 546 nm, ε = 8,300 M−1cm−1}, the mononitrosyl species was formed in approximately 90 % yield based on the reaction, (F8)Fe(NO)2 + (F8)FeII → 2 (THF)(F8)Fe(NO) (in THF solution).

Reaction of (F8)Fe(NO)2 with [(tmpa)Cu(MeCN)]PF6 and acid

Complex (F8)Fe(NO) (0.050 g, 0.059 mmol) was dissolved in 10 mL distilled acetone in a 50 mL Schlenk flask and then cooled to −78°C using an acetone/dry-ice bath. Excess •NO(g) was bubbled through the orange cold solution using a three-way syringe, and then the excess •NO(g) was removed via vacuum/purge cycles. After stirring for 30 min, the orange solution was added to the pre-chilled [(tmpa)CuI(MeCN)]-[B(C6F5)4] in 10 mL acetone/MeCN (1:1) (0.064 mg, 0.060 mmol) solution via a two-way syringe needle. After stirring for 10 minutes, a 5 mL acetonitrile solution of [H(C2H5OC2H5)2][B(C6F5)4] (HBArF) (0.098 mg, 0.118 mmol) was added to the cold orange solution mixture. It turned to brown upon warming to RT. The solution was concentrated in vacuo, and addition of deoxygenated pentane led to a brown solid. UV-Vis (λmax, nm): CH2Cl2, 394(Soret), 512; 394(Soret), 511. IR (Nujol, cm−1): no related νNO observed. EPR spectrum in acetone (77 K): g = 6.12 (heme-FeIII); g˔ = 2.21, gǁ = 2.01, A˔ = 100 G, Aǁ = 68 G (CuII). ESI-MS in MeCN: (813, (F8)Fe + H; 853, (F8)Fe + MeCN; 871, (F8)Fe + H2O + MeCN; 353, (tmpa)Cu). A 10 mL CH2Cl2 solution of the brown solid product was mixed with 10 mL aqueous NaCl solution (400 uM), and stirred for half an hour. Ion chromatography analysis of this upper aqueous layer extract gave no indication for the presence of any nitrite ion (NO2 −).

Gas chromatography analysis of the head space of this reaction mixture reveals N2O(g) formed in a yield of 84% according to the stoichiometry, 2 •NO + 2 e− + 2 H+ → N2O(g) + H2O. Thus, the metal complex products of the reaction are [(F8)FeIII]+, [(tmpa)CuII(solvent)]2+, along with N2O(g). See Results and Discussion for further information or clarification.

Reaction of (F8)Fe(NO)2 with [(tmpa)Cu(MeCN)]PF6

Complex (F8)Fe(NO) (0.040 g, 0.047 mmol) was dissolved in 10 mL distilled acetone and then cooled to −78°C using an acetone/dry-ice bath. Excess •NO(g) was bubbled through the cold solution using a three-way syringe. After stirring for 30 min, the orange solution of (F8)Fe(NO)2 was added to a pre-cooled [(tmpa)CuI(MeCN)]PF6 (0.026 mg, 0.048 mmol) solution in 10 mL acetone/MeCN (1:1) via a two-way syringe needle, and the mixture was allowed to stir for 30 min. After warming to RT, the solution mixture kept stirring for 1 hour and then was concentrated in vacuum. Addition of 70 mL deoxygenated pentane precipitated the orange product solution as a mixture of purple and green solids. An EPR spectrum indicated that the product was mixture of (F8)Fe(NO) and CuII species, while an IR spectrum of this solid (Nujol mull) indicated one •NO molecule is still bound to the (F8)Fe fragment, νNO = 1684 cm−1. UV-Vis (λmax, nm): THF, 410 (Soret), 546; CH2Cl2, 400 (Soret), 540. To determine what other nitrogen oxide products formed, a series of stock solutions of synthetically-derived [(tmpa)Cu(NO2)]SbF6 (vide supra) were generated, mixing (30 min) 10 mL CH2Cl2 with 10 mL aqueous NaCl (160 μM). The upper aqueous layer extract was taken for nitrite ion analysis on the Dionex DX-120 Ion chromatograph (See above for the procedure for generating a sample for ICA, and then a calibration curved was formed. Afterward, the product mixture of the reaction of {20 mg (F8)Fe(NO)2 + 13 mg [(tmpa)CuI(MeCN)]PF6 (1:1 molar ratio} was analyzed for ion fractions via the same method. Via this nitrite analysis, [(tmpa)Cu(NO2)]PF6 was found to form in a yield of 95%, based on the reaction stoichiometry: 3 •NO + [(L)CuI]+ → N2O + [(L)CuII(NO2 −)]+. Thus, the metal complex products of the reaction are (F8)Fe(NO) plus a mixture of 1/3 [(tmpa)CuII(NO2)]PF6 and unreacted 2/3 [(tmpa)CuI(solvent)]+. Gas chromatography analysis of the head space of the original reaction mixture reveals N2O(g) formed in a yield of 88% according to this stoichiometry. See Results and Discussion for further information or clarification.

Results and Discussion

We previously reported on •NO(g) reductive coupling chemistry carried out by a binuclear heme/Cu assembly with binucleating ligand referred to as 6L; with formation of a heme-dinitrosyl complex (6L)Fe(NO)2, addition of a copper(I) ion source along with acid led to excellent yields of N2O(g) (Scheme 2).1 In that study, the use of a heterobinucleating ligand made sense in terms of synthetic strategy in carrying out such cooperative heme/Cu/small-molecule investigations. This would vastly increase the liklihood that this reductive coupling chemistry was not resulting from heme-heme or copper-copper reactions.

Scheme 2.

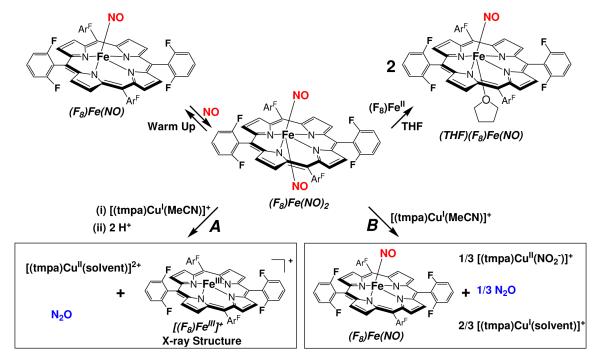

In fact, the use of component mixtures of heme and separate copper complexes has been previously very successful for our study of heme/Cu/O2 reactivity, leading to the generation and characterization of quite a large series of heme/Cu/O2 adducts, including those with 6L.10,25,36,37 Thus, here we chose to also apply that approach with respect to •NO(g) reductive coupling chemistry thus hopefully effected by a distinct heme together with a copper complex. Scheme 3 summarizes the chemical transformations described in this paper, and depicts all of the important individual complexes which have been characterized and will be discussed in this report.

Scheme 3.

As shown in Scheme 3, the mononitrosyl complex (F8)Fe(NO) reacted with •NO(g) to form the dinitrosyl species, (F8)Fe(NO)2, very similar in properties to the dinitrosyl complex generated in situ in the 6L system, (6L)Fe(NO)2 (Scheme 2).1 Once discovering that such complexes exist and can be generated in a stoichiometric manner (vida infra), we wished to take advantage of this fact that exactly two •NO molecules are present for each heme or heme/Cu assembly. This would as it turns out for the 6L binucleating system and also here, allow for a stoichiometric reaction, e.g., one synthetic model enzyme turnover,

| (eq 1). |

Exactly this reaction occurs when (F8)Fe(NO)2 is added to [(tmpa)CuI(MeCN)]+ in the presence of two equiv acid, the latter in the form of H(Et2O)2[B(C6F5)4]. The NOR type reaction occurs and the particular products obtained are [(F8)FeIII]+, [(tmpa)CuII(solvent)]2+, and N2O(g). However, when acid is absent, the reaction of (F8)Fe(NO)2 and [(tmpa)CuI(MeCN)]+ yields different products, and different •NO(g)/metal chemistry takes place (Scheme 3). Details are provided in the subsequent sections.

Mononitrosyl Complexes (F8)Fe(NO) and (THF)(F8)Fe(NO)

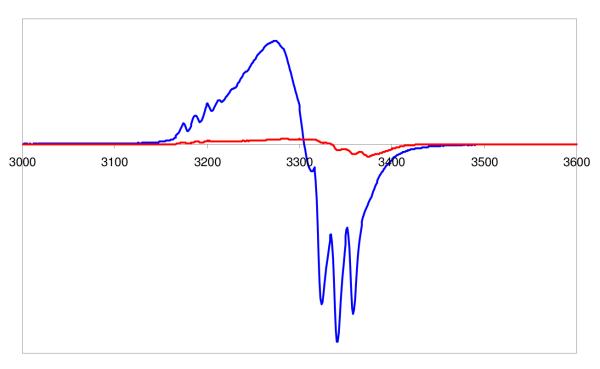

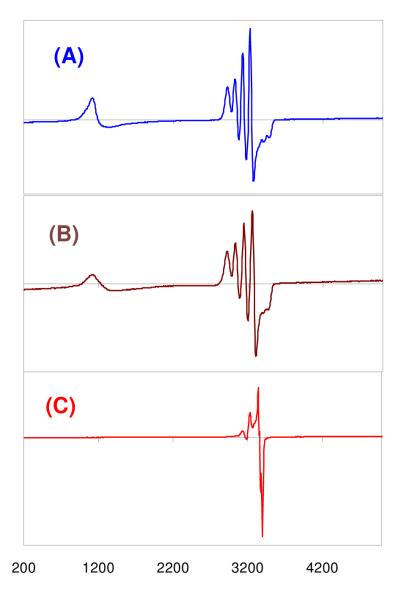

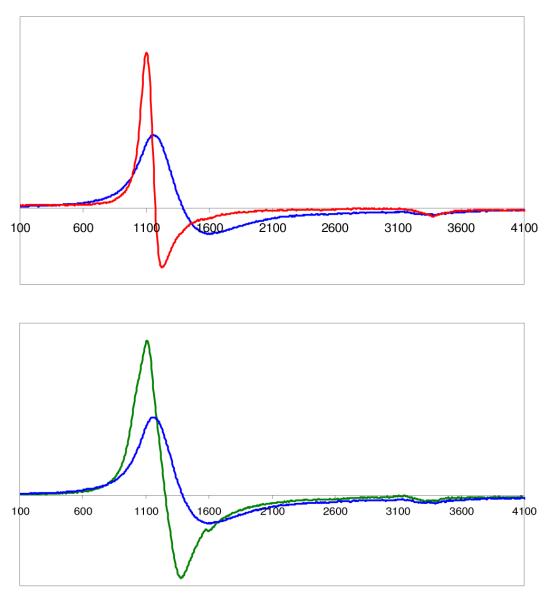

We recently1 reported on the synthesis and X-ray structure of (F8)Fe(NO), that formed via the reductive nitrosylation of (F8)FeIIICl. It can also be generated by bubbling •NO(g) through a (F8)FeII solution, i.e. (F8)FeII + NO → (F8)Fe(NO) (see Experimental Section). (F8)Fe(NO) is a stable complex as a solid and in solution, unreactive towards dioxygen. It displays a N–O stretching frequency at 1684 cm−1 (Nujol), 1691 cm−1 in CH2Cl2 solution and 1670 cm−1 in tetrahydrofuran (THF). It gives the expected classic rhombic EPR spectrum with three-line hyperfine splitting pattern due to unpaired electron interaction with 14N (I =1) of the nitrosyl ligand (g1 = 2.113, g2 = 2.078, g3 = 2.025), Figure 1.

Figure 1.

EPR Spectra of (F8)Fe(NO)2 (red) and (F8)FeNO (blue) at the same concentration in acetone, recorded at 77 K.

In the course of our studies with heme/Cu/O2 reactivity using (F8)FeII, we have explored the use of various solvents and found for example that acetone, THF and RCN (R = Me, Et) solvents bind the heme as axial ‘base’ ligands.30 THF is particularly strong compared to the others. In fact THF is found to bind quite strongly to (F8)Fe(NO), affording (THF)(F8)Fe(NO). We were able to isolate this six-coordinate nitrosyl complex, the first with an oxygen donor to be characterized by elemental analysis, IR, EPR, and UV-Vis spectroscopies. In Table 1, we compare IR, EPR, and UV-Vis parameters for (THF)(F8)Fe(NO), (F8)Fe(NO), various other (porphyrinate)Fe(NO) complexes and a previously described bis-THF adduct, (THF)2FeII.38

Table 1.

Comparisons of structural parameters for heme nitrosyl and related complexes.

| Complex | νNO (solvent), cm−1 | λmax (nm) | g value | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 5-coordinate | ||||

| g1=2.102, | ||||

| 1670 (KBr), | 405(Soret),537,606 | g2=2.064, | ||

| (TPP)Fe(NO) | 1678(CH2Cl2) | (CHCl3) | g3=2.010 | 39 |

| (TPPBr8)Fe(NO) | 1685(KBr) | --- | --- | 39 |

| (T2,6-Cl2PP)Fe(NO) | 1688 (KBr) | --- | --- | 39 |

| g1=2.113, | ||||

| g2=2.078, | ||||

| 1684 (Nujol) | 400(Soret), 541 | g3=2.025 | ||

| (F8)Fe(NO) | 1691 (CH2Cl2) | (CH2Cl2) | this work | |

| 6-coordinate | ||||

| (1-MeIm)(TPP)Fe(NO) | 1625 (KBr) | xxx | 39 | |

| (4-MePip)(TPP)Fe(NO) | 1653 (KBr) | --- | 39 | |

| (1-MeIm)( F8)Fe(NO) | 1624 (KBr) | --- | 40 | |

| g1=2.096, | ||||

| g2=2.050, | ||||

| (THF)(PPDME)Fe(NO) | --- | --- | g3=2.011 | 41,42 |

| g1=2.100, | ||||

| 1669 (THF); 1684 | 410 (Soret), 546 | g2=2.063, | ||

| (THF)(F8)Fe(NO) | (weak; due to (F8)Fe(NO) | (THF) | g3=2.011 | this work |

| 422 (Soret), 544 | ||||

| (THF)2(F8)Fe | --- | (THF) | silent | 38 |

| 426(Soret), 538 | ||||

| (F8)Fe(NO)2 | --- | (acetone) | silent | this work |

| 1696 | 416(Soret), 540 | |||

| (TmTP)Fe(NO)2 | (methylcyclohexane) | (methylcyclohexane) | --- | 43 |

| (TPP)Fe(NO)2 | 1695 (CHCl3) | --- | --- | 43 |

Abbreviations used: TPP = meso-tetraphenylporphyrin; TPPBr8 = octabromo-tetraphenylporphyrin; T2,6-Cl2PP = 2,6-difluorophenylporphyrin; 1-MeIm = 1-methylimidazole; 4-MePip = 4-methylpiperidine; PPDME = protoporphyrin IX dimethyl ester; TmTP = meso-tetra-m-tolyl-porphinato dianion.

The sub-field of heme-nitrosyl complexes, synthetic or biological, is already very mature, although it continues to draw considerable interest, due to more recently described biological processes which utilize or process •NO and its oxidized and reduced derivatives. There are many spectroscopically and structurally characterized five-coordinate and six-coordinate heme-nitrosyl complexes, so-called {FeNO}7 derivatives, the value of seven derived from the six d-electrons (i.e., 3d6) of iron(II) plus the unpaired electron from •NO.44,45 It seems to be the case that there are only quite small differences in structural coordination parameters comparing complexes with different coordination numbers. However, IR spectra clearly suggest that with axial ‘base’ binding to a trans/sixth position of a heme-NO moiety, the N-O stretching frequency shifts to a lower value.46 For example, (TPP)Fe(NO) has a N–O stretch at 1670 cm−1, which shifts to 1653 and 1625 when 4-methylpiperidine (4-MePip) and 1-methylimidazole (1-MeIm) are axial bound, respectively (Table 1). In the case of (F8)Fe(NO) (ν(N-O) = 1684 cm−1), ν(N-O) decreases by only 15 cm−1 with THF binding but by 60 cm−1 with 1-MeIm binding.40 Thus, our data clearly shows that THF is a significant base, but much weaker than N-donor ligands such as 1-methylimidazole which has been reported40 to effect a much larger (60 cm−1) shift to lower frequency.

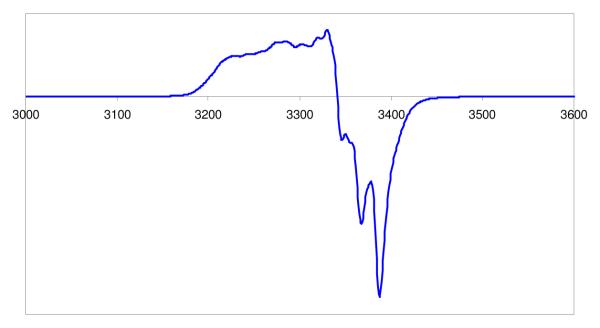

Another difference between five- and six-coordinated heme-NO species is their EPR spectroscopic behavior. Five-coordinated complexes always exhibit the triplet hyperfine as described above for (F8)Fe(NO).41,47 Depending on the sixth axial trans ligand, (L)(porpyrinate)Fe(NO) complexes reveal two different types of hyperfine splitting patterns. Most possess a nine-line pattern localized to the g2 or g3 region,41,48 due to the N hyperfine spitting of both the trans-N ligand and •NO, i.e. a triplet of triplets is observed. There are only a few six-coordinate complexes with O-donor trans ligands.41,42 (THF)(PPDME)Fe(NO) shows a three-line spectrum, but with smaller g-values than that of five-coordinated(PPDME)Fe(NO) (Table 1). It was suggested that this indicates electronic interaction of THF occurs though the lone pair electrons on the oxygen atom. Of course, this conclusion is readily observed from IR spectroscopic data on our own (THF)(F8)Fe(NO) complex (vide supra). Also, an EPR spectrum of this complex is nearly identical to that observed for (THF)(PPDME)Fe(NO), with a three line pattern with g-values (g1 = 2.100, g2 = 2.063, g3 = 2.011) altered somewhat from that seen for (F8)Fe(NO), see Figure 3 and Table 1.

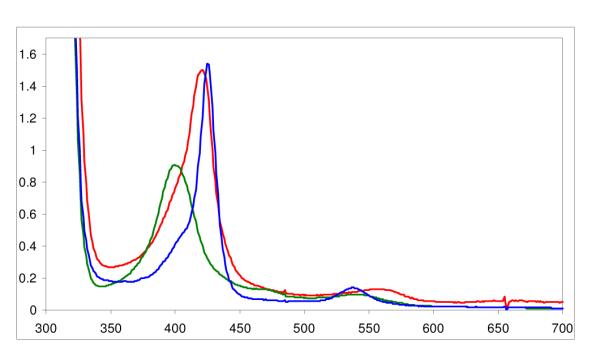

Figure 3.

UV-Vis Spectrum of (F8)Fe(NO)2 (blue, λmax= 426 (Soret), 538 nm) generated from (F8)FeII (red, λmax= 421 (Soret), 553 nm) in acetone at −80 °C. Upon warming the solution (in a closed cuvette glassware apparatus), the mononitrosyl species (F8)Fe(NO) reforms (green, λmax= 399 (Soret), 540 nm.

Dinitrosyl complex (F8)Fe(NO)2

This complex can be generated by bubbling excess •NO(g) through solutions of either (a) the (F8)FeII reduced compound or (b) the mononitrosyl complex (F8)Fe(NO) (See Experimental Section). For purposes of characterization and/or reactivity studies, excess •NO(g) was removed by application of vacuum/purge cycles. An EPR spectrum of such a sample of (F8)Fe(NO)2 in acetone (77 K) shows the compound to be EPR silent (Figure 1). This is consistent with it being diamagnetic, as might be expected by its formation from the radical species (F8)Fe(NO) (S = ½) by addition of another radical, •NO. As discussed below, NMR spectroscopic data are also consistent with the diamagnetism of (F8)Fe(NO)2.

| (eq. 1) |

In fact, the binding of •NO(g) to (F8)Fe(NO) is reversible, as can be monitored by EPR and UV-vis spectroscopies. Warming of an EPR sample of (F8)Fe(NO)2, removing gases in vacuo and refreezing and now recording an EPR spectrum leads to regeneration of most of the triplet EPR spectrum due to (F8)Fe(NO). A UV-vis spectrum of (F8)Fe(NO) shows absorptions at 399 (Soret) and 541 nm in acetone which change when excess NO(g) is bubbled through the cold solution forming (F8)Fe(NO)2 (Fig. 1). There is no obvious color change of reaction solution in either solvent. When (F8)Fe(NO)2 is warmed to RT, whether excess •NO(g) is present or not, (F8)Fe(NO) is reformed (eq. 1).

To further confirm the formulation of the dinitrosyl complex (F8)Fe(NO)2, we added one equiv of the reduced compound (F8)FeII to a low temperature solution of (F8)Fe(NO)2 from which excess •NO(g) had been removed via vacuum/purge cycles. There is some immediate transfer to give a mixture of mono- and dinitrosyl complexes, based on UV-Vis spectroscopy (Figure S4). However, warming to RT results in full formation of two equiv (F8)Fe(NO), thus the overall reaction proceeded as follows: (F8)Fe(NO)2 + (F8)FeII → 2 (F8)Fe(NO). Not only does this experiment demonstrate that our low temperature species is a dinitrosyl complex, i.e., possessing two NO molecules per iron, but that the second NO molecule binds much more weakly than the first and can be extracted by another heme molecule.

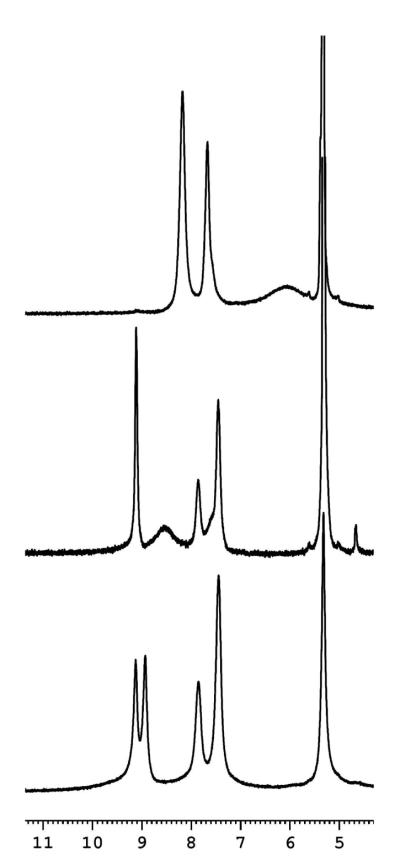

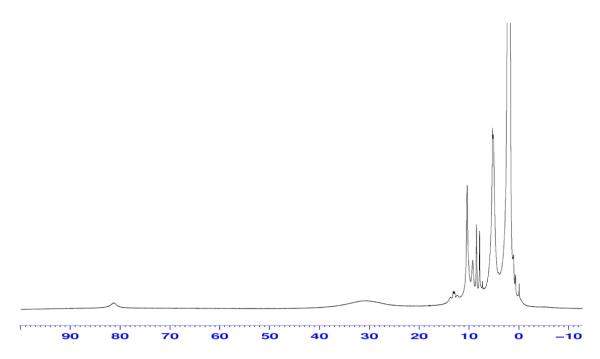

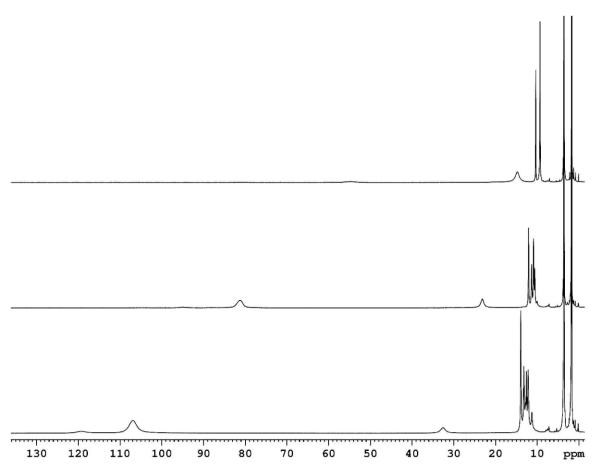

NMR Spectroscopy for the Heme-Nitrosyl Complexes

At RT, a 1H-NMR spectrum of (F8)Fe(NO) gives a broad pyrrole proton signal at 6.05 ppm (Table 2), consistent with is found for other heme mononitrosyl compounds (Table 2).40 Rather interesting temperature dependent behavior occurs, as is now described along with tentative interpretations. As shown in Figure 4 and Figure S5, 1H-NMR spectroscopic spectra of (F8)Fe(NO) were recorded at 20 °C, −20 °C, −40°C, −60 °C and −80 °C. At 20 °C, the pyrrole resonance is a broad peak, which may be due to the fast rotation of NO about the Fe-NO bond. When cooling to ~ −20 °C, a striking downfield shift occurs accompanying pyrrole splitting to one sharp peak at 9.12 ppm and one broad peak at 8.54 ppm, with integration found to be in a 1:7 ratio. With further cooling, the integration ratio of sharp peak versus broad peak increases to 2:6 (at −40 °C), 3:5 (at −60 °C) and 4:4 (at −80 °C). This trend is in accordance with a slowing of the NO rotation or even a “sitting” oxygen atom behavior. Especially at −80°C, four pyrrole protons were expected to be in the exactly same magnetic environment, and another four pyrrole protons stayed in a very similar environment, due to two equally occupied NO orientations at low temperature as Scheidt and coworkers49 suggested in the crystalline phase studies of (TPP)Fe(NO). The assignments of these peaks as pyrrole resonances was also confirmed by 2H-NMR spectroscopy employing a deuteriated heme complex, (F8-d8)Fe(NO) (see Figure S6).

Table 2.

1H-NMR spectroscopic resonance comparison: heme-Fe mono- and dinitrosyl complexes (CD2Cl2 at RT).

| Heme-Fe Complex | pyrrole-H (ppm) | meta-H (ppm) | para-H (ppm) | reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| (TPP)Fe(NO) | 5.95 | 8.25 | 7.45 | 40 |

| (TMP)Fe(NO) | 5.79 | 8.42/8.22 | --- | 40 |

| (F8)Fe(NO) | 6.00 | 8.17 | 7.65 | 40 |

| (OEP)Fe(NO) (a) | --- | 8.2 | 6.7 | 43 |

| (OEP)Fe(NO) 2(a) | 8.94 | 7.39 | 7.19 | 43 |

| (F8)Fe(NO) | 6.05 | 8.18 | 7.67 | this work |

| (F8)Fe(NO)(b) | 9.12/8.54 | 7.45 | 7.86 | this work |

| (F8)Fe(NO)2(b) | 9.13/8.93 | 7.45 | 7.85 | this work |

: spectra recorded in toluene-d7;

: spectra recorded at −80 °C.

Figure 4.

1H-NMR spectra recorded in CD2Cl2. Top - (F8)Fe(NO), RT. Middle - (F8)Fe(NO) at −80 °C. Bottom - of (F8)Fe(NO)2 at −80 °C. The peak at 5.32 ppm is CD2Cl2.

The 1H-NMR spectrum of what was thought to be (F8)Fe(NO)2, as recorded at −80 °C, presents what appears to be a symmetrically split signal for the pyrrole protons (Figure 4). However, the peak at 9.13 ppm overlaps exactly with that of the mono-nitrosyl species (F8)Fe(NO) indicating a mixture is present and that the 8.93 ppm signal can be assigned to the di-nitrosyl species. With warming to −60 °C and −40 °C, 1H-NMR spectra (Figure S7) indicate a mixture of (F8)Fe(NO)2 and (F8)Fe(NO) is present, but with less dinitrosyl complex present. The 8.93 ppm signal diminishes and shifts/broadens. At RT, the mononitrosyl complex fully reforms.50 These results indicate that under the conditions of the 1H-NMR experiment, with the concentrations of heme and amount of NO(g) that could be added to the sample tube, (F8)Fe(NO)2 is not fully formed. This is unlike what the situation appears to be in the separate UV-vis and EPR spectroscopy experiments (vide supra), where full formation is indicated.

A number of heme dinitrosyl complexes have been previously described and there has been increased interest in such species. In 1974, Wayland and coworkers51 suggested a dinitrosyl complex forms from the reversible coordination of •NO(g) to (TPP)Fe(NO) in toluene. The compound was suggested to be a (TPP)FeII(NO−)(NO+) species, i.e. with a linear FeII-NO+ unit and a bent FeII-NO− unit. In an electrochemical study in 1983, Kadish52 suggested the formation of (OEP)Fe(NO)2 (OEP = octaethylporphyrin) and (TPP)Fe(NO)2 occurs under •NO(g) pressure and that these could be electrochemically oxidized to cationic species. Ford43 pointed out that the optical spectrum for that TPP complex more resembled that of nitrosyl/nitrito complex. In 2000, Ford and coworkers43 described the dinitrosyl compounds Fe(TmTP)(NO)2 (TmTP = meso-tetra-m-tolyl-porphinato dianion) and Fe(TPP)(NO)2, using cryogenic conditions to stabilize the binding of a second NO; the adducts were characterized by UV-Vis, IR and NMR spectroscopies. Fe(TmTP)(NO) displays ν(N-O) = 1683 cm−1; Fe(TmTP)(NO)2 also possesses a single N–O stretch, ν(N-O) = 1696 cm−1.

In more biological situations, a trans-dinitrosyl species had been suggested to occur during (NO)FeIII hemoglobin autoreduction chemistry,53 while to explain •NO(g) dependent behavior during s-guanylate cyclase (sGC) activity, Ballou & Marletta54 at one point raised the possibility of such an entity forming. Since then, biophysical55,56 and theoretical studies57 on cyt. c’, bacterial class II cytochromes perhaps involved in •NO(g) detoxification, led to suggestions that its heme may bind two NO’s. As there are similarities between cyt. c’ and sGC (e.g., they both bind NO but not O2),57 the cyt. c’ researchers have supported the view that a Fe(NO)2 species may form as a transient intermediate in sGC.

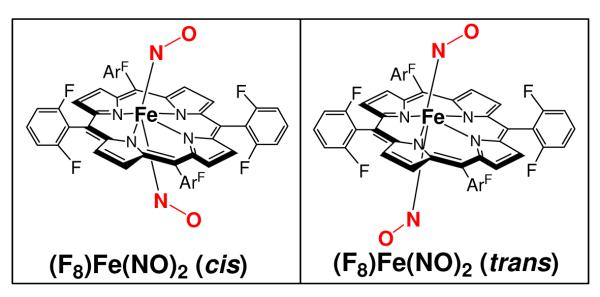

In fact, two computational studies58-60 carried out have led to a proposed heme dinitrosyl complex structure, both suggesting a lowest energy “trans-syn” conformation,59,60 what we refer to here as “cis” 58 conformation, Figure 5. Here, the nitrosyl ligands reside on opposite sides of the heme and the NO groups are bent over in the same direction. While Ford and coworkers43 only observed a single pyrrole resonance for Fe(TmTP)(NO)2, it is notable that here we observe two types of protons for (F8)Fe(NO)2 at −80 °C, Figure 4. However, these data still cannot differentiate between two possible structures, the “cis” versus the “trans” configuration (Figure 5).

Figure 5.

Two possible conformations (cis, trans) of the present (F8)Fe(NO)2 complex. Both have been suggested, but DFT calculations in 2003 from the groups of both Ford58 and Ghosh59,60 support the view that the cis-configuration would be the preferred structure in a porphyrinate-iron environment.

To summarize, we have observed here the reversible formation of (F8)Fe(NO)2 from •NO(g) reaction with (F8)Fe(NO), as deduced via UV-vis, EPR and NMR spectroscopic studies.61 Future investigations will be directed at understanding more about the electronic structure of (F8)Fe(NO)2 or analogues (such as studying Mössbauer spectroscopic properties), the detailed nature of the equilibrium between it and its mononitrosyl precursor and the reactivity of (F8)Fe(NO)2 with nucleophilic or electrophilic substrates. As mentioned above, the dinitrosyl complex has been very useful for us to carry out stoichiometric reactions where only two •NO(g) molecules are present for a heme plus copper complex reaction, as described below.

Reaction of (F8)Fe(NO)2 with [(tmpa)CuI(MeCN)]+ Plus Acid; •NO Reductive Coupling

With the presence of 2 equiv acid in the form of H(Et2O)2[B(C6F5)4] (HBArF), the reductive coupling of nitrogen monoxide was efficiently facilitated by this heme and copper complexes mixture of (F8)Fe(NO)2 and [(tmpa)CuI(MeCN)]+ (Scheme 3A), in the same stoichiometry as is known for CcOs:

| (eq. 2). |

Gas chromatography analysis (See Supporting Information, Figure S11) of the head space of the product mixture revealed a N2O(g) yield of 84%, based on eq. 2 and corresponding to the NOR stoichiometry of 2 NO + 2 H+ + 2 e− → N2O + H2O. This compares to the 80% yield of gaseous nitrous oxide obtained in the system with a binuclear heme/Cu complex of the 6L ligand (Scheme 2);1 both the binuclear complex and present component (heme + copper complex) system efficiently effect the NOR chemistry.

In order to rule out the possibility that only (F8)Fe(NO)2 itself mediates the •NO reductive coupling observed, its reaction with two equiv acid (HBArF) in a cold acetone solution was investigated. No UV-Vis change was observed at low temperature, and even following warming from −80 °C. The iron(II) nitrosyl complex (F8)Fe(NO) was produced as determined by UV-Vis, IR and EPR spectroscopic analysis; •NO(g) was released as detected by GC analysis. This control experiment indicates that only (F8)Fe(NO)2 and acid cannot facilitate NO reductive coupling, i.e. the copper complex [(tmpa)CuI(MeCN)]+ has a critical role in the NOR chemistry described here.

Identity of Products Formed

Different from the starting material employed, the orange colored dinitrosyl complex (F8)Fe(NO)2 forms a homogeneous brown solution upon addition of the copper(I) complex and acid (see Experimental Section). A UV-Vis spectrum of the product mixture has λmax = 394 (Soret), 512 nm (in THF, Table 3), which corresponds to what should be a heme-FeIII complex [(F8)FeIII]+ with B(C6F5)4− counter anion (see Experimental Section). In fact, these UV-vis properties perfectly match those of [(F8)FeIII]SbF6 which was independently synthesized (Table 3). To further determine the identity of the products of reaction (eq 2), an EPR spectrum was recorded following precipitation of solids from the reaction mixture in acetone/CH3CN and re-dissolution in acetone (Fig. 7A). It also confirms the presence of the heme-FeIII species (i.e., [(F8)FeIII]+) along with a CuII complex with trigonal bipyramidal (TBP) coordination geometry, possessing well-known (for TBP CuII) ‘reverse’ axial EPR spectral properties (g˔ > gǁ)62-64. In fact, this perfectly matches the known spectroscopic behavior of [(tmpa)CuII(MeCN)]2+ (See Experimental Section and Fig. 7B). To confirm that the heme and copper products were formed in equal amounts, as per Eq 2 and Scheme 3A, we generated and recorded an EPR spectrum of a made-up 1:1 (molar equiv) mixture of [(F8)FeIII]SbF6 and [(tmpa)CuII(MeCN)](ClO4)2, Figure 7B. This beautifully matches the spectrum recorded for the product mixture in the NO reductive coupling reaction (Figure 7A), (F8)FeIII (g = 6.10) and CuII (g˔ = 2.21, gǁ = 2.01, A˔ = 100 G, Aǁ = 68 G).

Table 3.

UV-Vis comparison of Relevant (F8)-Fe Complexes.

| Complex | THF (λmax ,nm) | Acetone (λmax ,nm) |

|---|---|---|

| (F8)Fe(NO) | 410(Soret), 546 | 399(Soret), 541 |

| (F8)Fe(NO)2 | 410(Soret), 540 | 426(Soret), 538 |

| [(F8)FeIII]SbF6 | 394(Soret), 510 | 404(Soret), 510, 568 |

|

Products of {(F8)Fe(NO)2 + (tmpa)Cu(MeCN)]+ + 2 H+} |

394(Soret), 510 | 404(Soret), 510, 568 |

|

Products of {(F8)Fe(NO)2 + (tmpa)Cu(MeCN)]+} |

410(Soret), 546 | 399(Soret), 541 |

Figure 7.

EPR spectra (acetone; 77K) of (A) the product mixture of the reaction: (F8)Fe(NO)2 + [(tmpa)CuI(MeCN)]+ + 2 H+ (blue) showing typical heme-FeIII complex and [(tmpa)CuI(solvent)]2+; (B), a made-up 1:1 mixture of [(F8)FeIII]SbF6 and [(tmpa)CuII (MeCN)](ClO4)2 (brown); (C) the product mixture obtained from reaction of (F8)Fe(NO)2 + [(tmpa)CuI(MeCN)]+ in the absence of acid (red), (F8)Fe(NO) + 1/3[(tmpa)CuII(NO2−)]+ + unreacted 2/3[(tmpa)CuI(solvent)]+; see Figure S8 for an expanded view of this spectrum. See text for further explanation.

To check on other possible products in the reaction mixture, we used the solid material obtained by adding pentane to the acetone/MeCN reaction mixture. An IR spectrum (Nujol mull)65 showed that there is no nitrosyl-heme species present, further corroborating the nature of the reaction; both NO molecules initially present as the (F8)Fe(NO)2 complex, are consumed, and N2O(g) is produced (vide supra). To check for the possibility that nitrite might have been generated and might have accounted for some product of •NO reactivity, we carried out ion chromatography analysis on an aqueous extract of the reaction mixture (see Experimental Section). However, no trace of nitrite could be detected. A room-temperature 1H-NMR spectrum of the products solution in CD3CN (Figure 11) showed it was a mixture of what appeared to be a high-spin heme-FeIII complex and also possessing paramagnetically shifted signals ascribed to the TMPA ligand on [(tmpa)CuII(MeCN)](ClO4)2 (as determined from the previously determined NMR properties of this complex).66 A more detailed description of the NMR spectroscopic and spin-state properties of this heme complex, [(F8)FeIII]SbF6, will be discussed below.

Figure 11.

1H-NMR of the product mixture of the NOR reaction: {(F8)Fe(NO)2 + [(tmpa)CuI(MeCN)]+ + 2 H+} in CD3CN at RT.

Reaction of (F8)Fe(NO)2 with [(tmpa)CuI(MeCN)]+ in the Absence of Acid

Of course, the presence of protons is required in NORs to give turnover, see eq 1. In fact, we originally hypothesized that we may not need protons to effect •NO reductive coupling. In NOR’s, it is thought that a μ-oxo heme/non-heme diiron(III) complex forms following reductive coupling, as this has been detected by several groups.4,11,67-69 Perhaps the chemistry could proceed as follows:

Thus, we hypothesized that proton equivalents might not be necessary for the same chemistry to occur in heme-copper oxidases, since our research group has synthesized and published on a number of heme-FeIII-O-CuII complexes, including ones which are structurally characterized.29,70,71 So, perhaps the heme-iron and copper ions would facilitate •NO(g) coupling chemistry and also be Lewis acidic enough to force this reaction without protons, as,

However, this is not the case and as described above acid is required to effect •NO(g) coupling in the (F8)Fe(NO)2 + [(tmpa)CuI(MeCN)]+ system. In fact, when [(tmpa)CuI(MeCN)]+ is added to (F8)Fe(NO)2 without acid present, the products obtained are a mixture of heme-nitrosyl plus CuII-nitrite and unreacted CuI complexes, eq. 3 (and Scheme 3B).

| (eq. 3) |

A UV-Vis spectrum of a reaction mixture reveals bands associated with the presence of (F8)Fe(NO), only λmax (THF) = 410 (Soret), 546 nm; λmax {(acetone) = 399 (Soret), 541 nm} and IR spectroscopy gives νNO = 1684 cm−1.65 An EPR spectrum of the reaction product solution (Fig. 7C) indicates it is a mixture of typical (porphyrinate)FeII-NO and CuII species,72 consistent with our proposed course of reaction (eq. 3). Thus, without added acid, one of the two nitrogen monoxide molecules (per heme/Cu stoichiometric mixture) remains within a metal complex product, i.e. in the form of (F8)Fe(NO). Our expectation then was that any remaining •NO released may have undergone a copper complex mediated disproportionation reaction, giving nitrite and N2O(g) according to well established copper(I)/•NO(g) chemistry:4,45

| (eq. 4). |

In fact, this seems to be the case. GC analysis reveals that N2O(g) is produced in 88 % yield based on eq. 4. This is far less than should be or is produced by our NOR chemistry with acid present, Scheme 3A and eq. 2. In further support of the chemistry outlined here, ion chromatography analysis of an aqueous solution extract of the reaction mixture (see Experimental Section) indicates nitrite (NO2−) is present in the product mixture with a yield of 95%, according to eq. 4. In summary, without added acid, one of the two nitrogen monoxide molecules remains in the product, and the other •NO(g) molecule released is disproportionated to nitrite in the form of nitrito complex and N2O(g). Further evidence comes from control experiments, where we separately show that [(tmpa)CuI]+ is a complex which does facilitate nitrogen monoxide disproportionation, see below.

Reaction of [(tmpa)CuI(MeCN)]+ with •NO(g); Nitrogen Monoxide Disproportionation4,45

When excess •NO(g) is exposed to [(tmpa)CuI(MeCN)]+, the related nitrito complex [(tmpa)CuII(NO2)]+ is produced in excellent yield, as determined by elemental analysis, UV-Vis and EPR spectroscopies (Figures S2 and S3) and ion chromatography which was carried out to further confirm/identify nitrite anion (see Experimental Section). Nitrous oxide gas was also identified qualitatively (by GC); quantitative determination was made difficult by the conditions of excess •NO(g) required to obtain high yields of [(tmpa)CuII(NO2)]+. To summarize, [(tmpa)CuI(MeCN)]+ is capable of •NO(g) disproportionation chemistry and is likely the source of N2O(g) when [(tmpa)CuI(MeCN)]+ reacts with •NO(g), by itself (as described here), or in the reaction also with (F8)Fe(NO)2 present but without added acid (vide supra).

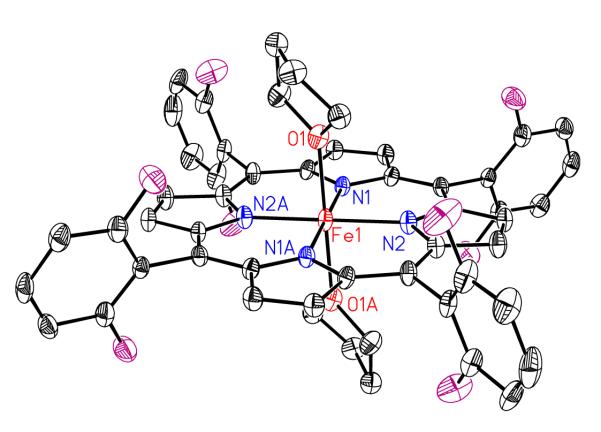

Structure, Spectroscopy and Spin-State Properties of [(F8)FeIII](SbF6)

As described above, [(F8)FeIII]+ (as the B(C6F5)4 salt) was formed in the NOR model system reacting (F8)Fe(NO)2 with [(tmpa)CuI(CH3CN)]+B(C6F5)4− in the presence of acid. And to help confirm its identity we separately synthesized [(F8)FeIII]SbF6 via a metathesis reaction of (F8)FeIIICl with AgSbF6 (see Experimental Section and Figure S9) and we compared UV-vis and EPR properties with those obtained in our NOR model reaction. However, a closer examination of the EPR and NMR properties of [(F8)FeIII]SbF6 indicates that the complex exists as a spin-state mixture of S = 3/2 and S = 5/2, with the ground state being mainly a high-spin state (S = 5/2). The following paragraphs detail this situation.

There is an extensive literature concerning spin-states which can occur with iron(III) porphyrinate complexes.48,73 High-spin, intermediate-spin or low-spin states which occur are dramatically influenced by the external ligand(s) bound to the heme. A variety of physical techniques can be applied to characterize and differentiate spin-state possibilities for heme-FeIII complexes, such as X-ray crystallography along with EPR and NMR spectroscopies. One of the principal structural features is the M–Nporphyrinate bond length, which increases as one goes from lower to higher spin states, i.e., (S = 1/2) < (S = 3/2) < (S = 5/2). Secondly, g values observed in EPR spectra become enlarged when the spin states are higher. Thirdly, 1H-NMR spectra exhibit notable downfield shifts of the pyrrole protons when the spin states change from low- to intermediate to high spin. Certain heme-FeIII complexes are known to possess an admixture (but not thermal equilibrium) of S = 3/2 and S = 5/2 species and these exhibit a range of physical properties.48,73

In fact, a good number of [(porphyrinate)FeIII]+ complexes, such as five-coordinated [(TPP)FeIII]ClO4, are known to be spin-admixed complexes,35 also see Table 4. Walker and co-workers74 have in fact previously studied [(F8)FeIII]ClO4; in CH2Cl2, this was shown to be an S = 3/2 and S = 5/2 spin admixture; the ground state was largely high-spin with the S = 3/2 state as the first excited state, based on EPR (4.2K) and NMR (CD2Cl2) spectroscopic properties. Here, we compare these properties with our own [(F8)FeIII]SbF6 in CH2Cl2. As we were able to obtain crystals and an X-ray structure of [(F8)FeIII(THF)2]SbF6 (vide infra), we also more carefully examined this six-coordinated species’ THF solution EPR (77K) and variable temperature NMR spectroscopic properties. As described below, we also find both [(F8)FeIII]SbF6 and [(F8)FeIII (THF)2]SbF6 complexes to be an S = 3/2 and S = 5/2 spin admixture.

Table 4.

Selected Fe-N bond distance, g values and 1H-NMR of heme-FeIII complexes.

| Heme-FeIIIComplex | Fe–N (Å) | g˔ value | pyrrole-H (δ, ppm) |

spin state | reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 5-coordinate | |||||

| (OEP)FeCl | 2.063 | 5.76(toluene) | 80.3(CDCl3) | h.s. (a) | 73,75,76 |

| (TPP)FeCl | 2.040 (9) 2.070 (9) |

5.66(toluene) | 80.8(toluene-d8) | h.s. | 75,77,78 |

| (F8)FeCl | 2.089(4) | 6.16(CH2Cl2) | 81.0(CDCl3) | h.s. | 29,30 |

| [(OEP)Fe](ClO4) | 1.994(10) | 5.83 (CH2Cl2) | --- | i.s. (b) | 79,80 |

| [(TPP)Fe](ClO4) | 2.001(5) | 4.72(CH2Cl2) 5.84(2- metTHF) |

−10 | h.s. + i.s. | 35,74 |

| [(F8)Fe](ClO4) | --- | 5.72(CH2Cl2) | ~15 | h.s. + i.s. | 74 |

| [(F8)Fe](SbF6) | --- | 5.84(CH2Cl2) | 27.2, 11.6 | h.s. + i.s. | this work |

| 6-coordinate | |||||

| [(OEP)Fe(DMSO)2]+ | 2.035(9) | --- | --- | h.s. | 81 |

| [(TPP)Fe(H2O)2]+ | 2.045(8) 2.029(5) |

~6(solid) | --- | h.s. | 82,83 |

| [(OEP)Fe(1-MeIm)2]+ | 2.004(2) | --- | --- | l.s. (c) | 81 |

| [(TPP)Fe(1-MeIm)2]+ | 1.982(3) | gz = 2.890, gy= 2.291, gx=1.554 |

--- | l.s. | 84 |

| [(OEP)Fe(THF)2]+ | 1.999(2) 1.978(12) |

4.68(CH2Cl2) | --- | i.s. | 85,86 |

| [(TPP)Fe(THF)2]+ (d) | 2.00(1) | --- | --- | i.s. | 87 |

| [(F8)Fe(THF)2](SbF6) | 2.027(3) | 6.12(THF) | 54.7, 14.8 | h.s + i.s. | this work |

: h.s. = high spin, S=5/2;

: i.s. = intermediate spin, S=3/2;

: l.s. = low spin, S=1/2;

: derived from a dinuclear heme-FeIII-CuII complex, [(TPP)Fe(THF)2]-{[(TPP)Fe(THF)][Cu(MNT)2]} •2THF (MNT = cis-1,2-dicyanoethylenedithiolate) OEP = octaethylporphine; TPP = meso-tetraphenylporphyrin; 2-metTHF = 2-methytetrahydrofuran; 1-MeIm = 1-methylimidazole; DMSO = dimethyl sulfoxide.

Recrystallization of isolated complex [(F8)FeIII]SbF6 out of THF/hexane provides a bis-THF complex, [(F8)FeIII (THF)2]SbF6 (see Experimental Section and Supporting Information); the structure is depicted in Figure 8. The average Fe–Nporphyrinate bond distance is 2.027 (3) Å, clearly in between those of known low-spin (avg. = ~1.99 Å) and high-spin six-coordinate derivatives (avg. > 2.04 Å). Also see Table 4 for these and other relevant comparisons. The value is also much shorter than that of the related 5-coordinated high-spin complex (F8)FeIIICl (Fe–Nporphyrinate = 2.089(4) Å) complex,30 the material used to synthesize [(F8)FeIII(THF)2]SbF6. In addition, the axial Fe-OTHF bond distance, 2.131 Å, is significantly longer than those observed for low-spin state complexes, but very similar to those of two other bis-THF complexes, [(TPP)Fe(THF)2]+ (Fe-O = 2.16 Å) and [(OEP)Fe(THF)2]+ (Fe-O = 2.187 Å) (Table 4). As stated, these compounds are known to possess intermediate-spin states. The possibility that [(F8)FeIII]SbF6 is not a quantum-admixed spin system, but rather possesses an intermediate-spin system, is ruled out by EPR and NMR spectroscopic information, as described below.

Figure 8.

ORTEP Diagram showing the cationic portion of of [(F8)FeIII(THF)2]SbF6. Also see Table 4 for structural parameters.

When [(F8)FeIII]SbF6, lacking any THF, is dissolved in CH2Cl2 and the EPR spectrum recorded at 77 K, a g = 5.84 feature is observed (Figure 9). This lies in the range expected for admixed-spin state complexes (g = 4.2 to 6) and not typical for high- (g = ~ 6.2) or low-spin complexes (g = ~ 3.5 or < 3.4).73 Our g = 5.84 signal also well matches that observed for [(F8)FeIII]ClO4(g = 5.72, 4.2 K).74 In addition, this EPR spectrum of [(F8)FeIII]SbF6 in frozen CH2Cl2 is much broader than that of the typical high-spin complex (F8)FeIIICl (Fig. 9). The broadening has been suggested to be due to a quantum admixed feature.88 In the strongly coordinating solvent THF, the 77 K EPR spectrum of [(F8)FeIII (THF)2]SbF6 indicates the complex is mostly or all high-spin, based on the observed g = 6.12 (Fig. 9). In another words, and according to the criterion put forth by Walker and coworkers89 along with Maltempo and Moss,90 g˔ = 6(a5/2)2 + 4(b3/2)2 {where (a5/2)2 and (b3/2)2 are the coefficients of the high-spin and intermediate-spin states, respectively} and thus the EPR data suggest that high-spin state (S =5/2) is the ground state for both [(F8)FeIII]SbF6 and [(F8)FeIII (THF)2]SbF6, while the latter is almost completely at this state.

Figure 9.

(Top): EPR spectra in CH2Cl2 at 77 K of [(F8)FeIII]SbF6 (blue, g˔ = 5.84) and (F8)FeIIICl (red, g˔ = 6.16); (Bottom): EPR spectra of [(F8)FeIII]SbF6 in two solvents at 77 K, possessing g˔ = 5.84 in CH2Cl2 (blue) and g˔ = 6.12 in THF (green) at 77 K.

Further, the 1H-NMR spectrum of [(F8)FeIII]SbF6 and the position of the pyrrole proton resonances indicates the complex to be in a mixed-spin state at RT in CD2Cl2, Figure S10. Two pyrrole resonances are observed at δpyrrole = 27.2 and 11.6 ppm, both typical for intermediate-spin complexes. These shift downfield when the temperature decreases but still lie in the intermediatespin state range. [(F8)FeIII]ClO4 exhibits δpyrrole = ~15 ppm at RT).74 In THF-d8, signals for both high-spin (δpyrrole = 54.7 at RT) and intermediate spin (δpyrrole = 14.8 at RT) are observed at all temperatures (Figure 10). However, a greater fraction of high-spin [(F8)FeIII(THF)2]SbF6 species is present at reduced temperatures, δpyrrole (high-spin) = 54.7 ppm at RT, shifting to 107 ppm at −80°C which is in the high-spin chemical shift region.

Figure 10.

1H-NMR spectra of [(F8)FeIII(THF)2]SbF6 in THF-d8 at various temperature: 20°C, −40°C, and −80°C from top to bottom.

To summarize, the 1H-NMR spectra are consistent with EPR spectroscopic and X-ray structural parameters, i.e. the ground states of both [(F8)FeIII]SbF6 and [(F8)FeIII(THF)2]SbF6 are high spin (S =5/2), while [(F8)FeIII]SbF6 has a larger intermediate-spin fraction (S =3/2) with increasing temperature. As mentioned earlier, a 1H-NMR spectrum of the product mixture of {(F8)Fe(NO)2 + [(tmpa)CuI(MeCN)]+ + 2 H+} in CD3CN (Figure 11) might suggest a high-spin [heme-FeIII]B(C6F5)4 (vide supra) product is formed, which seems inconsistent with the data just described for the synthetically derived [(F8)FeIII]SbF6 (Figure S10) or [(F8)FeIII(THF)2]SbF6 species. While considering the controlling role of exogenous ligands on the spin states of six-coordinate heme-FeIII complexes, it is likely that either a water molecule (produced from the NOR type reaction), or acetonitrile or acetone (from the reaction solvents) binds to (F8)FeIII and this results in it being mostly in a high-spin state.

Summary/Conclusions: Implications for NORs

In this report, we have described heme/Cu complex components (in a 1:1 mixture) facilitating •NO(g) reduction to N2O(g), analogous to one enzyme turnover of nitrogen monoxide reactivity with certain CcOs. The overall results are not greatly altered from those obtained by instead using a binuclear (6L)-heme/Cu complex (Scheme 2).1 Heme-FeII, CuI, and acid are all required to trigger the reaction. The dinitrosyl complex (F8)Fe(NO)2, provides exactly two equiv •NO per heme-and-copper moiety, allowing us to monitor a stoichiometric reaction. The dinitrosyl complex has been characterized by variable- temperature NMR and UV-vis, as well as EPR spectroscopies. DFT calculations by Ghosh59,60 and Ford58 suggest that heme dinitrosyl complexes possess a so-called “cis” conformation, which is in accordance with the 1H-NMR spectroscopic data we observe for (F8)Fe(NO)2. In addition to the five-coordinate (F8)Fe(NO) complex previously reported, a new six-coordinate complex with THF as the axial base, (THF)(F8)Fe(NO), was synthesized and characterized by UV-vis, EPR and IR spectroscopies. Also, [(F8)FeIII]SbF6, a new variation on previously well known complexes, was synthesized to help us identify the product of the heme/Cu/•NO(g) chemistry described here, and this has been determined to exist in solution as an admixture of high- and intermediate-spin states.

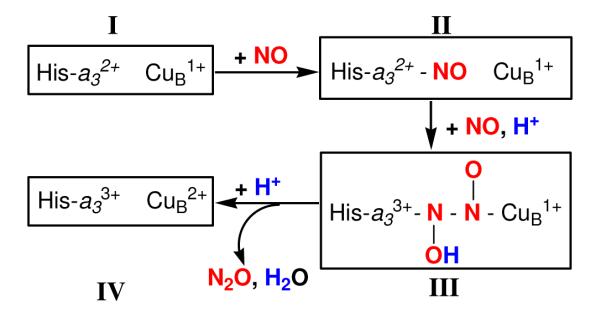

Concerning heme/Cu •NO(g) reductive coupling (bio)chemistry, recent biophysical studies and DFT calculations from Varotsis, Kitagawa, Ohta and coworkers2,13,91,92 have led to the suggestion of what is referred to as a trans mechanism (Scheme 4). This was adopted based on their biophysical and DFT studies, with reference to the literature on heme/non-heme diiron containing NORs (see Introduction). Rate limiting addition of •NO(g) and a proton to heme-nitrosyl complex II leads to a “N2O2H” intermediate which possesses a N–N bond; note that reduced CuBI is proposed to be present in this species. The oxidized and protonated hyponitrite (deprotonated hyponitrite is N2O22−, so III would possess a protonated N2O2− moiety, Scheme 4)) is proposed to be N-bound to both the metal ions. These researchers assert direct detection of intermediates II and III via resonance Raman spectroscopic interrogation,2,13,91 however the latter hyponitrite complex was generated by adding excess •NO(g) to an oxidized (FeIII…CuII) form of the enzyme, and may be one-electron oxidized from intermediate III. Finally, it is suggested that further protonation leads to N2O generation, Scheme 4.

Scheme 4.

In the light of this proposed enzyme mechanism (Scheme 4), we suggest possible steps in the chemistry described in the present report. A likely first step in the reaction would be the attack of the copper(I) complex ([(tmpa)CuI(MeCN)]+) on the nitrogen monoxide ligand in (F8)Fe(NO)2; an analogous step probably also occurs when N2O is produced from the (6L)-heme/Cu system (Scheme 2). This may release one •NO(g) molecule which now attacks a binuclear heme-FeII-(NO)-CuI species to give something like intermediate III (Scheme 4), i.e., a hyponitrite type species. Protonation, electron-transfer from Cu+ of the (tmpa)CuI moiety and N–O cleavage could give N2O(g) and water, and in our case the heme-FeIII and CuII complexes observed. We suggest that there are other possibilities that should be considered here and for other synthetic systems to be studied in the future, or even for the enzymes, see below.

The likelihood of N-N coupling occurring from a Fe–N-O…O-N–Cu species would seem to us to be problematic. Moënne-Loccoz12 has recently suggested transient binding of NO to the copper ion may occur as either an O-bound (η1-O) or a side-on (η2-NO) complex, as supported by FTIR and resonance Raman spectroscopic studies. Such a situation could lead to a geometry or juxtaposition of the two NO moieties so as to greatly facilitate N-N formation. Further, Moënne-Loccoz12 suggests the hyponitrite moiety is O-bond to both heme and copper ion metal centers, contrary to what is suggested by Scheme 4. Related to this hypothesis, Richter-Addo and coworkers93 recently isolated a stable hyponitrite-bridged diiron(III) complex (OEP)Fe-(trans-− ON=NO−)-Fe(OEP). An X-ray structure revealed hyponitrite dianion O,O’-ligation. Protonation of this species led to Fe-O and O-N bond cleavage and release of N2O(g).

Thus, more efforts are needed to investigate the catalytic mechanism of this •NO(g) reductive coupling chemistry in CcOs. For this present system or analogue synthetic systems we design in the future, investigations will be directed toward a number of goals. We wish to find or stabilize a possible hyponitrite or other intermediate(s) that may form, and deduce details of the coordination chemistry involved. What is the role of iron vs. copper in NO binding and stabilization of a hyponitrite intermediate via O- or N-ligation? Does electron-transfer to two NO molecules occur from both metals together to give ligated N2O22− or a protonated derivative? Or is the process step-wise, one-electron at a time, as suggested in Scheme 4? What is the role and timing of proton addition? How does an axial base (proximal histidine to heme Fe) function during the whole process; note that we did not have a strong ‘base’ for the heme in the present system, nor for that based on the 6L heterobinuclear complex reported earlier.1 For the proteins, Varotsis and co-workers suggest initial •NO(g) binding to the ferrous heme leads to Fe-Nhistidine cleavage to give a five-coordinate heme-nitrosyl.11,91,94,95 And of course, there are many basic questions to probe in heme/copper (or heme/non-heme diiron) model systems concerning N-N bond formation and N-O cleavage. We look forward to a rich coordination chemistry of these binuclear heme/M systems and nitrogen oxide species.

Synopsis.

With significant chemical interest and biological relevance, we have investigated •NO(g) reductive coupling employing heterodinuclear heme/Cu components, (F8)Fe(NO)2 and [(tmpa)CuI(MeCN)]+. Together and with added acid, N2O(g) is produced, along with [(F8)FeIII]+ and [(tmpa)CuII(solvent)]2+. In the absence of acid, the course of reaction very different. The dinitrosyl complex (F8)Fe(NO)2 has been characterized by various spectroscopic methods; the binding of NO(g) to (F8)Fe(NO) is reversible. In addition, the spin state properties of [(F8)FeIII]+ have been deduced.

Supplementary Material

Figure 2.

EPR spectrum of (THF)(F8)Fe(NO) recorded at 77 K in THF with g1 = 2.102, g2 = 2.064, g3 = 2.010. It is essentially identical to the spectrum of (THF)(PPDME)Fe(NO), reported by Yoshimura.42

Acknowledgement

This work was supported by a grant from the National Institutes of Health (K.D.K., GM 60353).

Footnotes

Supporting Information. X-ray structure CIF file; UV-vis, EPR, and NMR spectroscopic details. This material is available free of charge via the Internet at http://pubs.acs.org.

References

- (1).Wang J, Schopfer MP, Sarjeant AAN, Karlin KD. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2009;131:450–451. doi: 10.1021/ja8084324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (2).Pinakoulaki E, Varotsis C. J. Inorg. Biochem. 2008;102:1277–1287. doi: 10.1016/j.jinorgbio.2008.01.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (3).Moënne-Loccoz P. Natural Product Reports. 2007;24:610–620. doi: 10.1039/b604194a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (4).Wasser IM, de Vries S, Moënne-Loccoz P, Schröder I, Karlin KD. Chem. Rev. 2002;102:1201–1234. doi: 10.1021/cr0006627. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (5).Saraste M, Castresana J. FEBS Letters. 1994;341:1–4. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(94)80228-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (6).van der Oost J, de Boer APN, de Gier J-WL, Zumft WG, Stouthamer AH, van Spanning RJM. FEMS Microbiol. Letters. 1994;121:1–10. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.1994.tb07067.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (7).Averill BA. Chem. Rev. 1996;96:2951–2964. doi: 10.1021/cr950056p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (8).Ferguson-Miller S, Babcock GT. Chem. Rev. 1996;96:2889–2907. doi: 10.1021/cr950051s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (9).Collman JP, Boulatov R, Sunderland CJ, Fu L. Chem. Rev. 2004;104:561–588. doi: 10.1021/cr0206059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (10).Kim E, Chufán EE, Kamaraj K, Karlin KD. Chem. Rev. 2004;104:1077–1133. doi: 10.1021/cr0206162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (11).Zumft WG. J. Inorg. Biochem. 2005;99:194–215. doi: 10.1016/j.jinorgbio.2004.09.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (12).Hayashi T, Lin MT, Ganesan K, Chen Y, Fee JA, Gennis RB, Moënne-Loccoz P. Biochemistry. 2009;48:883–890. doi: 10.1021/bi801915r. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (13).Varotsis C, Ohta T, Kitagawa T, Soulimane T, Pinakoulaki E. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2007;46:2210–2214. doi: 10.1002/anie.200602963. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (14).Blomberg LM, Blomberg MRA, Siegbahn PEM. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 2006;1757:31–46. doi: 10.1016/j.bbabio.2005.11.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (15).Zhao X, Yeung N, Russell BS, Garner DK, Lu Y. J. Am Chem. Soc. 2006;128:6766–6767. doi: 10.1021/ja058822p. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (16).Cooper CE, Brown GC. J. Bioenerg. Biomembr. 2008;40:533–539. doi: 10.1007/s10863-008-9166-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (17).Cooper CE, Giulivi C. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2007;292:C1993–2003. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00310.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (18).Benamar A, Rolletschek H, Borisjuk L, Avelange-Macherel M-H, Curien G, Mostefai HA, Andriantsitohaina R, Macherel D. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA) - Bioenergetics. 2008;1777:1268–1275. doi: 10.1016/j.bbabio.2008.06.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (19).Antunes F, Boveris A, Cadenas E. Antioxidants & Redox Signaling. 2007;9:1569–1580. doi: 10.1089/ars.2007.1677. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (20).Mason MG, Nicholls P, Wilson MT, Cooper CE. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2006;103:708–713. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0506562103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (21).Brunori M, Giuffre A, Forte E, Mastronicola D, Barone MC, Sarti P. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 2004;1655:365. doi: 10.1016/j.bbabio.2003.06.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (22).Brudvig GW, Stevens TH, Chan SI. Biochemistry. 1980;19:5275–5285. doi: 10.1021/bi00564a020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (23).Cooper CE, Mason MG, Nicholls P. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA) - Bioenergetics. 2008;1777:867–876. doi: 10.1016/j.bbabio.2008.03.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (24).Castello PR, Woo DK, Ball K, Wojcik J, Liu L, Poyton RO. Proc. Nat. Acad. Sci. 2008;105:8203–8208. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0709461105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (25).Chufan EE, Mondal B, Gandhi T, Kim E, Rubie ND, Moenne-Loccoz P, Karlin KD. Inorg. Chem. 2007;46:6382–6394. doi: 10.1021/ic700363k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (26).Wasser IM, Huang HW, Moenne-Loccoz P, Karlin KD. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2005;127:3310–3320. doi: 10.1021/ja0458773. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (27).Schopfer MP, Mondal B, Lee D-H, Sarjeant AAN, Karlin KD. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2009;131:11304–11305. doi: 10.1021/ja904832j. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (28).Schopfer MP, Mondal B, Lee D-H, Sarjeant AAN, Karlin KD. J. Am Chem. Soc. 2009 doi: 10.1021/ja904832j. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (29).Karlin KD, Nanthakumar A, Fox S, Murthy NN, Ravi N, Huynh BH, Orosz RD, Day EP. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1994;116:4753–4763. [Google Scholar]

- (30).Ghiladi RA, Kretzer RM, Guzei I, Rheingold AL, Neuhold Y-M, Hatwell KR, Zuberbühler AD, Karlin KD. Inorg. Chem. 2001;40:5754–5767. doi: 10.1021/ic0105866. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (31).Tyeklár Z, Jacobson RR, Wei N, Murthy NN, Zubieta J, Karlin KD. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1993;115:2677–2689. [Google Scholar]

- (32).Zhang CX, Liang H-C, Kim E.-i., Shearer J, Helton ME, Kim E, Kaderli S, Incarvito CD, Zuberbühler AD, Rheingold AL, Karlin KD. J. Am Chem. Soc. 2003;125:634–635. doi: 10.1021/ja028779v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (33).Kubas GJ. Inorg. Synth. 1990;28:68–70. [Google Scholar]

- (34).Jutzi P, Muller C, Stammler A, Stammler HG. Organometallics. 2000;19:1442–1444. [Google Scholar]

- (35).Reed CA, Mashiko T, Bentley SP, Kastner ME, Scheidt WR, Spartalian K, Lang G. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1979;101:2948–2958. [Google Scholar]

- (36).Chufán EE, Puiu SC, Karlin KD. Acc. Chem. Res. 2007;40:563–572. doi: 10.1021/ar700031t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (37).Ghiladi RA, Ju TD, Lee D-H, Moënne-Loccoz P, Kaderli S, Neuhold Y-M, Zuberbühler AD, Woods AS, Cotter RJ, Karlin KD. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1999;121:9885–9886. [Google Scholar]

- (38).Thompson DW, Kretzer RM, Lebeau EL, Scaltrito DV, Ghiladi RA, Lam K-C, Rheingold AL, Karlin KD, Meyer GJ. Inorg, Chem. 2003;42:5211–5218. doi: 10.1021/ic026307b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (39).Wyllie GRA, Scheidt WR. Chem. Rev. 2002;102:1067–1089. doi: 10.1021/cr000080p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (40).Praneeth VKK, Nather C, Peters G, Lehnert N. Inorg. Chem. 2006;45:2795–2811. doi: 10.1021/ic050865j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (41).Cheng L, Richter-Addo GB. Binding and Activation of Nitric Oxide by Metalloporphyrins and Heme. In: Kadish KM, Simith KM, Guilard R, editors. Porphyrin Handbook. Vol. 4. Academic Press; San Diego, CA: 2000. pp. 219–291.pp. 4 Chapter 33. Chapter 33, pp. 219-291. [Google Scholar]

- (42).Yoshimura T. Inorg. Chim. Acta. 1982;57:99–105. [Google Scholar]

- (43).Lorkovic I, Ford PC. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2000;122:6516–6517. [Google Scholar]

- (44).Enemark JH, Feltham RD. Coord. Chem. Rev. 1974;13:339–406. [Google Scholar]

- (45).Lee D-H, Mondal B, Karlin KD. NO and N2O Binding and Reduction. In: Tolman WB, editor. Activation of Small Molecules: Organometallic and Bioinorganic Perspectives. Wiley-VCH; New York: 2006. pp. 43–79. [Google Scholar]

- (46).As is well understood, the sixth ligand provides additional electron density to the iron ion, which leads to enhanced backbonding to the π*(NO) orbital thus weakening the N–O bond and lowering ν(N-O).

- (47).Ford PC, Lorkovic IM. Chem. Rev. 2002;102:993–1017. doi: 10.1021/cr0000271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (48).Walker FA, Simonis U. Iron Porphyrin Chemistry. In: King RB, editor. Encyclopedia of Inorganic Chemistry. Second Edition Vol. IV. John Wiley & Sons Ltd.; 2005. pp. 2390–2521. [Google Scholar]

- (49).Silvernail NJ, Olmstead MM, Noll BC, Scheidt WR. Inorg. Chem. 2009;48:971–977. doi: 10.1021/ic801617q. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (50).1H-NMR spectra of (F8)Fe(NO)2 and (F8)Fe(NO) in acetone-d6 are also given in the Supporting Information.

- (51).Wayland BB, Olson LW. J. Am Chem. Soc. 1974;96:6037–6041. doi: 10.1021/ja00826a013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (52).Lancon D, Kadish KM. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1983;105:5610–5617. [Google Scholar]

- (53).Addison AW, Stephanos J. J. Biochemistry. 1986;25:4104–4113. doi: 10.1021/bi00362a018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (54).Zhao Y, Brandish PE, Ballou DP, Marletta MA. Proc. Nat. Acad. Sci. 1999;96:14753–14758. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.26.14753. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (55).Lawson DM, Stevenson CEM, Andrew CR, Eady RR. Embo J. 2000;19:5661–5671. doi: 10.1093/emboj/19.21.5661. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (56).Pixton DA, Petersen CA, Franke A, van Eldik R, Garton EM, Andrew CR. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2009;131:4846–4853. doi: 10.1021/ja809587q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (57).Marti MA, Capece L, Crespo A, Doctorovich F, Estrin DA. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2005;127:7721–7728. doi: 10.1021/ja042870c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (58).Patterson JC, Lorkovic IM, Ford PC. Inorg. Chem. 2003;42:4902–4908. doi: 10.1021/ic034079v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (59).Conradie J, Wondimagegn T, Ghosh A. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2003;125:4968–4969. doi: 10.1021/ja021439p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (60).Ghosh A. Acc. Chem. Res. 2005;38:943–954. doi: 10.1021/ar050121+. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (61).We have thus far been unable to obtain low-temperature infrared spectroscopic data for this complex.

- (62).Maiti D, Lee D-H, Narducci Sarjeant AA, Pau MYM, Solomon EI, Gaoutchenova K, Sundermeyer J, Karlin KD. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2008;130:6700–6701. doi: 10.1021/ja801540e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (63).Lucchese B, Humphreys KJ, Lee D-H, Incarvito CD, Sommer RD, Rheingold AL, Karlin KD. Inorg. Chem. 2004;43:5987–5998. doi: 10.1021/ic0497477. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (64).Karlin KD, Hayes JC, Shi J, Hutchinson JP, Zubieta J. Inorg. Chem. 1982;21:4106–4108. [Google Scholar]

- (65).data not shown

- (66).Nanthakumar A, Fox S, Murthy NN, Karlin KD. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1997;119:3898–3906. [Google Scholar]

- (67).Pinakoulaki E, Gemeinhardt S, Saraste M, Varotsis C. J. Biol. Chem. 2002;277:23407–23413. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M201913200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (68).Moënne-Loccoz P, Richter O-MH, Huang H.-w., Wasser IM, Ghiladi RA, Karlin KD, de Vries S. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2000;122:9344–9345. [Google Scholar]

- (69).Field SJ, Prior L, Roldan MD, Cheesman MR, Thomson AJ, Spiro S, Butt JN, Watmough NJ, Richardson DJ. J. Biol. Chem. 2002;277:20146–20150. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M112202200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (70).Ju TD, Ghiladi RA, Lee D-H, van Strijdonck GPF, Woods AS, Cotter RJ, Young J, V. G, Karlin KD. Inorg. Chem. 1999;38:2244–2245. [Google Scholar]

- (71).Kim E, Helton ME, Wasser IM, Karlin KD, Lu S, Huang H.-w., Moënne-Loccoz P, Incarvito CD, Rheingold AL, Honecker M, Kaderli S, Zuberbühler AD. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2003;100:3623–3628. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0737180100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (72).The amount of Cu(II) complex present should be at a level of 1/3 of the amount of heme-nitrosyl complex present, thus the g = 2.0 to 2.2 region of Fig. 7C is dominated by the heme-nitrosyl complex signal

- (73).Scheidt WR. Porphyrin Handbook. 2000;3:49–112. [Google Scholar]

- (74).Nesset MJM, Cai S, Shokhireva TK, Shokhirev NV, Jacobson SE, Jayaraj K, Gold A, Walker FA. Inorg. Chem. 2000;39:532–540. doi: 10.1021/ic9907866. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (75).Balch AL, Lamar GN, Latosgrazynski L, Renner MW. Inorg. Chem. 1985;24:2432–2436. [Google Scholar]

- (76).Whitlock HW, Hanauer R, Oester MY, Bower BK. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1969;91:7485. [Google Scholar]

- (77).Scheidt WR, Finnegan MG. Acta Crystallographica Section C-Crystal Structure Communications. 1989;45:1214–1216. doi: 10.1107/s0108270189000715. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (78).Hoard JL, Cohen GH, Glick MD. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1967;89:1992. [Google Scholar]

- (79).Dolphin DH, Sams JR, Tsin TB. Inorg. Chem. 1977;16:711–713. [Google Scholar]

- (80).Masuda H, Taga T, Osaki K, Sugimoto H, Yoshida Z, Ogoshi H. Inorg. Chem. 1980;19:950–955. [Google Scholar]