In Britain it is a criminal offence to drive if the driver's measured ethanol concentration exceeds 35 μg per 100 ml in breath or 80 mg per 100 ml in blood. Those found guilty are disqualified from driving unless they can give a special reason why this should not happen.1 Most commonly, a defendant claims a friend has “laced” a drink by adding spirits, so that he or she has unwittingly consumed an amount of ethanol sufficient to raise the blood ethanol concentration above the limit.2,3 Doctors are sometimes asked in court whether a defendant would have known that a drink has been laced. We conducted an experiment to discover whether volunteers were able to tell that vodka had been added to a drink.

Subjects, methods, and results

We recruited healthy volunteers who gave written informed consent. The west Birmingham research ethics committee approved the study. Two venues were chosen, one at the summer ball of the medical students' society (142 subjects) and the other at an “awayday” held by Birmingham University's department of public health and epidemiology (47 subjects). Different volumes of vodka (0 ml, 12.5 ml, 25 ml, 50 ml, and 75 ml) were made up to 200 ml with orange juice, giving ethanol concentrations of 0 g, 2.0 g, 4.0 g, 7.9 g, and 11.9 g per 100 ml (% weight/volume). Different volumes of vodka (0 ml, 20 ml, 35 ml, 50 ml, and 70 ml) were made up to 200 ml with lager, giving ethanol concentrations of 2.7 g, 5.9 g, 8.2 g, 10.6 g, and 13.7 g per 100 ml (% weight/volume). We guessed that at least eight volunteers in each group were required to give acceptable statistical power.

A table of random numbers was used to allocate one of the five concentrations of drink to sequentially numbered beakers.4 Volunteers took a beaker, tasted the mixture (or drank it entirely), and answered a supervised questionnaire recording their sex and age, the number of units they usually drank, smoking habit, beaker number, and their response, “yes” or “no,” to the question “is this drink pure?”Results for lager and orange juice were analysed by multivariate logistic regression (spss version 8) to establish the probability of identifying a laced drink correctly as a function of the amount of ethanol added.

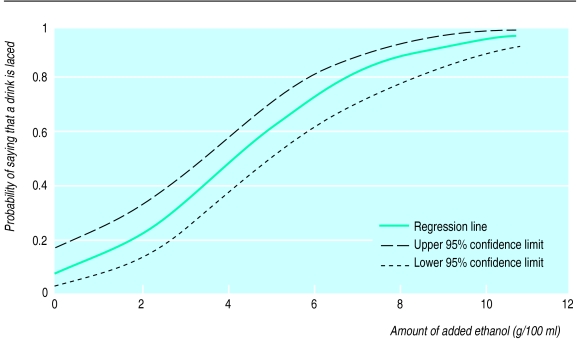

A total of 142 subjects attended the medical school ball, of whom 108 (76%) took part in the study, together with six of the researchers. At the awayday, 39 of 47 (83%) subjects contributed, together with two domestic staff. The only variable that significantly affected the probability of detecting a laced drink was the amount of ethanol added (figure).

Correction for smoking status (not shown) made a slight but significant difference with improved discrimination (but only 11 subjects smoked). Cor- rection for sex, age, type of drink (orange juice or lager), drinking habit, or venue made no significant difference.

Comment

Volunteers were poor at discriminating between laced and non-laced drinks even when large amounts of alcohol (the equivalent of 3-4 measures of spirit per pint) were added. It is unlikely that those convicted of drunken driving would be better able to discriminate in the pub than our volunteers.

In a small study of 25 students whose sensitivity was dulled with mouthwash, about 50% of subjects identified ethanol being present in a mixture of approximately 5 g/100 ml in tonic water.5

We estimate that 50% of subjects would be able to detect that a drink is laced when 4.1 g (95% confidence interval 3.2 g to 5.0 g) of ethanol is added.

Figure.

Probability of saying that a drink is laced against the amount of ethanol added, all results combined

Acknowledgments

We thank L Younger, R Blackshaw, A Buchan, and P Watkinson for helping with the trials.

Footnotes

Funding: None.

Competing interests: None declared.

References

- 1.Ley NJ. Drink driving law and practice. London: Sweet and Maxwell; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Jones AW. Top ten defence challenges among drinking drivers in Sweden. Med Sci Law. 1991;31:229–238. doi: 10.1177/002580249103100307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Denny RC. The use of breath and blood alcohol values in evaluating “hip flask” defences. N Law J. 1986;26 September:923–924. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Armitage P, Berry G. Statistical methods in medical research. Oxford: Blackwell Scientific Publications; 1971. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Marlatt GA, Demming B, Reid JB. Loss of control drinking in alcoholics: an experimental analogue. J Abnorm Psychol. 1973;81:233–241. doi: 10.1037/h0034532. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]