Abstract

Interleukin (IL)-18 is a cytokine isolated as an important modulator of immune responses and subsequently shown to be pleiotropic. IL-18 and its receptors are expressed in the central nervous system (CNS) where they participate in neuroinflammatory/neurodegenerative processes but also influence homeostasis and behavior. Work on IL-18 null mice, the localization of the IL-18 receptor complex in neurons and the neuronal expression of decoy isoforms of the receptor subunits are beginning to reveal the complexity and the significance of the IL-18 system in the CNS. This review summarizes current knowledge on the central role of IL-18 in health and disease.

Introduction

Interleukin (IL)-18 was isolated in 1995 as a co-factor that, in synergism with IL-12, stimulated the production of gamma interferon (INF-γ) in Th1 cells [1]. Since then extensive in vitro and in vivo studies have identified IL-18 as an important link between innate and adaptive immune responses and a regulator of both cellular and humoral immunity [2-4]. Constitutively produced as an inactive precursor by several cell types IL-18 is secreted in its active form following maturation by caspase 1 in response to inflammatory and infectious stimuli. In addition to its effects on Th1 cells, IL-18 is a strong stimulator of the activity of natural killer cells alone or in combination with IL-15, and of CD8+ lymphocytes. Together with IL-2, IL-18 can also stimulate the production of IL-13 and of other Th2 cytokines. Thus, it is perhaps not surprising that IL-18 was found to be associated with or demonstrated to contribute to numerous inflammatory-associated disorders. These include infections, autoimmune diseases, rheumatoid arthritis, cancer, as well as metabolic syndrome and atherosclerosis [5-11].

IL-18 had not originally been expected to cross an intact blood brain barrier and its immunological effector cells are not normally found in the healthy brain. Yet, studies on the possible role of IL-18 in the central nervous system (CNS), initiated soon after its cloning, were prompted primarily by its similarities with IL-1, which was already demonstrated to have central action. It was soon found that IL-18 could be synthesized centrally and its receptor subunits were now demonstrated to be broadly expressed in neurons. When recombinant interleukin 18 became available it also became clear that IL-18 was active centrally. Work on mice null for IL-18 or its receptor subunit alpha is helping to decipher the action of this cytokine in the brain. Finally, the recent discovery of novel IL-18 receptor subunits in the brain has revealed the complexity of the IL-18 system and may lead to better understanding of both the similarities and opposing actions of IL-1 and IL-18. This review summarizes more than a decade of work aimed at understanding how the IL-18 system contributes to local central inflammatory processes or can influence neuronal function and behavior. A summary of the literature supporting the involvement of IL-18 in neurophysiological and neuropathological conditions is presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Representative neurophisiological and neurophatological conditions involving IL-18

| Condition | Species | Citation |

|---|---|---|

| Behavior | ||

| Sleep | Rat/Rabbit | [72] |

| Fever | Mouse | [73,162] |

| Feeding | Mouse | [10,11] |

| Learning and memory | Mouse | [77] |

| Rat | [48,74,75] | |

| Human | [108,111,163] | |

| Stress and HPA axis | ||

| Rat | [56,57,81] | |

| Rat/Mouse | [62] | |

| Holstein cattle | [80] | |

| Pig | [54,55] | |

| Human | [136] | |

| Neuroinflammation | ||

| Brain injury | ||

| Hypoxia-ischemia | Mouse | [67,84,164-167] |

| Rat | [67,168] | |

| Thromboembolic stroke | Mouse | [83] |

| Spinal cord injury | Rat | [87] |

| Focal brain ischemia | Rat | [86] |

| Stroke | Mouse | [59,85] |

| Human | [169] | |

| Nerve injury | Rat | [47] |

| Viral infection | Chicken | [170] |

| Human | [59,171] | |

| Autoimmune neurodegenerative disease | ||

| Multiple Sclerosis | Human | [95-99,101] |

| EAE | Mouse | [91,93,100] |

| Rat | [89,90,92,94] | |

| Neurodegenerative disease | ||

| Alzheimer's disease | Human | [50,106-109,111-114] |

| Parkinson's disease | Mouse | [117] |

| Neuropsychiatric disorders | ||

| Depression | Rat | [133] |

| Human | [136,137,139] | |

| Schizophrenia | Human | [134,135] |

| Other central actions | ||

| Excitotoxic damage | ||

| Ataxia | Mouse | [53] |

| Neurodegeneration | Mouse | [150] |

| Glioma | Rat | [156,157] |

| Mouse | [152-155] | |

Components of the IL-18 system

IL-18 is synthesized as an inactive 24-kDa precursor protein that is subsequently processed by caspase-1 into its mature secretable form, which has a molecular weight of 18 kDa [4,12-16]. Pro-IL-18 can also be processed into its active form by various extracellular enzymes including protease 3 (PR-3), serine protease, elastase and cathepsin G [17-19]. Only the mature peptide is reported to be biologically active.

The existence of a putative short isoform of IL-18 resulting from alternative splicing removing 57 bp/19 aa was first described in rat adrenal glands (IL-18α) [20] and subsequently in mouse spleens (IL-18s) [21]. Recombinant IL-18s did not display IL-18-like activity in stimulating INF-γ production when tested alone but appeared to have a modest synergistic action with IL-18. To this date this isoform has not been reported in the CNS.

The IL-18 receptor (IL-18R) belongs to the interleukin 1 receptor/Toll like receptor superfamily. It is comprised of two subunits, IL-18Rα (also known as IL-1Rrp1, IL-18R1 or IL-1R5) and IL-18Rβ (also termed IL-18RacP, IL-18RII or IL-1R7) both with three extracellular immunoglobuling-like domains and one intracellular Toll/IL-1 receptor (TIR) domain [22,23]. IL-18 is believed to bind directly only to IL-18Rα with signal transduction occurring after recruitment of IL-18Rβ to form a high-affinity heterotrimeric complex with IL-18Rα/IL-18 [23-25].

Isoforms of both IL-18Rα and IL-18Rβ were recently described in vivo in the CNS. They include a short transcript for IL-18Rα encoding for a receptor subunit lacking the TIR domain arbitrarily named IL-18Rα type II [26]. Since the TIR domain is required for signaling, IL-18Rα type II was proposed to be a decoy receptor, similar to the type II IL-1R [27]. In addition, a truncated form of IL-18Rβ comprising only one of the three immunoglobulin domains was described in rat and human tissues including the brain [28,29]. This form was proposed to act as a soluble negative regulator of IL-18 action by stabilizing IL-18 binding to IL-18Rα yet preventing signaling.

Another negative regulator of IL-18 action is the IL-18 binding protein (IL-18BP). Isolated as cytokine-binding molecules, this 38-kDa soluble protein displays some sequence homology with IL-18Rα [30-32]. IL-18BP binds selectively and with high affinity to mature IL-18, but not to pro-IL-18, preventing its interaction with IL-18Rα. Four human (18BPa-d) and two murine (IL-18BPc and d) IL-18BP isoforms have been described [33]. Of these human IL-18BPb and d lack the structural requirement to inhibit IL-18 action and their role remains to be determined [5].

A different member of the IL-1 family, IL-1F7, is also a negative regulator of IL-18 action. IL-1F7 is able to bind IL-18BP and the IL-18BP/IL-1F7 complex can interact with the IL-18Rβ chain preventing the formation of the funtional IL-18R complex [34]. Several human IL-1F7 splice variants (IL-1F7a-e) have been described [35-39] whereas no murine homologue of IL-1F7 has yet been found. Of these, IL-1F7b (also known as IL-1H, IL-1H4 and IL-1RP1) matured by caspase-1 is capable of binding IL-18Rα [37,40]. Yet, the IL-1F7/IL-18Rα complex failed to recruit IL-8Rβ and no direct agonistic nor antagonistic activity of IL-1F7b for IL-18R was described [37,40].

IL-18 signaling

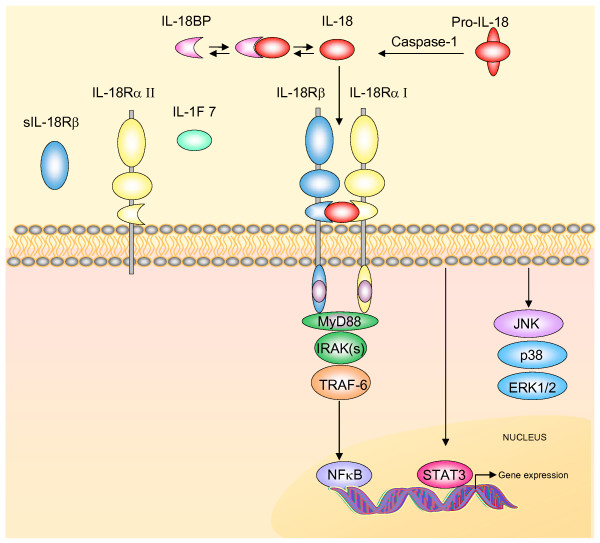

Canonical IL-18 action occurs via recruitment of the adaptor myeloid differentiation factor (MyD88). This event allows activation of the IL-1R-associated kinase (IRAK)/tumor necrosis factor receptor-associated factor 6 (TRAF6) pathway leading to nuclear translocation of the nuclear factor kappa beta (NF-κB) and subsequent modulation of gene transcription [4,5,41,42] (Fig 1).

Figure 1.

The IL-18 system. Active IL-18 is produced and secreted after proteolitic cleavage of the biological inactive precursor Pro-IL-18 by caspase-1. IL-18 action can be regulated by the IL-18 binding protein (IL18-BP) that binds IL-18 with high affinity and inhibits its function. Free IL-18 binds to a specific heterodimeric cell surface receptor, a member of the IL-1 receptor/Toll like receptor superfamily comprised of two subunits, IL-18Rα (here referred to as IL-18RαI) and IL-18Rβ, both with three extracellular Ig-like domains and one intracellular portion containing the Toll/IL-1R domain (TIR). Interaction of IL-18 with the IL-18Rα stabilizes its interaction with IL-18Rβ and with the adaptor protein MyD88 via the TIR domain. This initiates signal transduction by recruitment of the IL-1 receptor activating kinase (IRAK). IRAK autophosphorylates and dissociates from the receptor complex subsequently interacting with the TNFR-associated factor-6 (TRAF6) eventually leading to nuclear translocation of the nuclear factor κB (NF-κB). Engagement of the IL-18R complex can also activate STAT3 and the mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) p38, JNK and ERK. One truncated variant of IL-18Rα (IL-18RαII) lacking the intracellular TIR domain, and one soluble isoform of the IL-18Rβ (sIL-18Rβ) were demonstrated in vivo in the mouse brain and in the rat and human brain, respectively. These isoforms originating from differential splicing are proposed to be decoy receptors and possible negative regulators of IL-18 fuction. IL-1F7 is another proposed regulator of IL-18 action (see text for details).

IL-18 has also been reported to signal via the activation of the transcription factor tyk-2 [43], STAT3 [44] and NFATc4 [45]. In addition, a role for mitogen-activated protein kinases (MAPK) (i.e., extracellular signal-regulated kinase, ERK1/2 and p38), and phosphatidylinositol-3 kinase (Pi3K) in IL-18 signalling has been suggested [4,44-46].

While these data on peripheral cells were consolidated over a decade of work with the immune system, knowledge of the IL-18-dependent signaling in the CNS is only beginning to emerge. Activation of the IL-18R increased NF-κB phosphorylation and induced hypertrophy in astrocytes [47]. In the rat dentate gyrus, the functional effects of IL-18 were significantly attenuated by prior application of c-jun-n-terminal kinase (JNK) pathway, cyclooxygenase-2 (COX-2) and inducible nitric oxide synthase (iNOS) inhibitors, and a role for p38 MAPK was also suggested [48,49]. Moreover, human neuron-like differentiated SH-SY5Y neuroblastomas exhibited an IL-18-dependent increase in the levels of several kinases including p35, Cdk5, GSK-3beta, and Ser15-phosphorylated p53 [50].

IL-18 system in the CNS

IL-18 transcript was demonstrated by RT-PCR in a variety of brain regions including the hippocampus, the hypothalamus and the cerebral cortex [51,52]. In in vivo studies, IL-18 protein was demonstrated in the pituitary gland, ependymal cells, the neurons of the medial habenula (where its synthesis was elevated by stress), in Purkinje cells, and in astrocytes in the cerebellum [53-57]. In addition, it was demonstrated in vitro that microglia and astrocytes can produce IL-18 [58-61] and its level can be up-regulated following LPS stimulation [62] or treatment with INF-γ [63].

In the CNS, Northern blot analysis failed to detect the presence of IL-Rα [64] and IL-Rβ [65] soon after their cloning. The first evidence that IL-18R components are expressed in brain tissue was obtained by Wheeler and colleagues [52] which reported the constitutive expression of IL-18Rα, IL-18Rβ in the rat hypothalamus by RT-PCR. Subsequently, the mRNA expression of IL-18Rα, IL-18Rβ and the soluble form of the IL-18Rβ were detected in the hypothalamus, hippocampus, striatum and cortex and in cultured astrocytes, microglia and neurons [28]. More recently in vivo analysis showed that IL-18Rα mRNA and protein are constitutively expresseed in neurons throughout the brain [26,53,60,66]. Similar neuronal localization and distribution was found for IL-18Rβ (Alboni et al., unpublished data). At the same time it was demonstrated that the truncated decoy form of the IL-18Rα was expressed in neuronal cells with a pattern similar to that of its active counterpart [26]. Overall, IL-18R subunits had broad distribution across the brain with the highest level in the hypothalamus, hippocampus and amygdala. Finally, both IL-18 and IL-18R subunits are inducible and their CNS levels can be regulated. For instance, in the mouse hippocampus the levels of IL-18 and IL-18Rα increased after kainic acid (KA)-induced excitotoxicity, [60] whereas hypoxic-ischemic brain injury markedly increased IL-18 expression in mouse microglia [67]. In addition nerve injury induced IL-18 upregulation in rat spinal cord microglia possibly via p38 activation [47].

IL-18BP has been investigated and demonstrated in rodent brains, mixed glia and microglia by only one group using RT-PCR. Its distribution and action in the CNS remain to be investigated [52,68].

Information on central IL-1F7 is also limited to one study that demonstrated its presence in the human brain [37]. Investigating IL-1F7 in the CNS is also hampered by the fact that a mouse homologue has not been identified.

Behavior

The similarities between the IL-1 and the IL-18 systems suggested the possibility that like IL-1β, IL-18 may be one mediator of the behavior symptoms of sickness. These include fever, lethargy, hypophagia and cognitive alterations [69-71].

It was demonstrated that central intracerebroventricular (i.c.v.) injection of IL-18 in rabbits and rats increased non-rapid eye movement sleep as well as brain temperature [72]. The lethargic effects of IL-18 were also observed following intraperitoneal injection of IL-18, whereas, unlike IL-1β, peripheral administration did not induce fever [72,73]. Instead, pre-treatment with IL-18 reduced the pyrogenic effects of IL-1 suggesting the possibility of an antagonizing effect of these cytokines on fever [73].

Work on IL-18 null, and on IL-18BP overexpressing mice indicated that IL-18 is anorexigenic and can modulate feeding, but also energy homeostasis, influencing obesity and insulin resistance [10,11]. The mechanisms through which IL-18 exerts these effects are largely unknown but central action was proposed following the observation that i.c.v. injections of exogenous IL-18 induces sleep [72] and anorexia [11]. The recent demonstration that IL-18 functional and regulatory subunits of the IL-18R are expressed in several brain regions including the hippocampus, the hypothalamus and the cortex provided a molecular and cellular basis for the central action of IL-18 in modulating these functions [26].

Evidence for the role of IL-18 as modulator of neuronal functions includes studies on the hippocampal system, a structure that plays a major role in memory and in cognition. For instance, IL-18 reduces long term potentiation (LTP) in the rat dentate gyrus, possibly through the involvement of metabotropic glutamate receptors [48,49,74,75]. In particular, IL-18 had no effect on baseline synaptic transmission or paired pulse depression, but significantly depressed the amplitude of NMDA receptor-mediated field excitatory post synaptic potentials [75] providing evidence of a direct neuromodulatory role for IL-18 in synaptic plasticity. It is possible that IL-18 may act directly on the neurons of the dentate gyrus, moreover, its action may be regulated by the relative level of IL-18Rα type I and type II, both highly expressed in these cells [26]. Work on CA1 pyramidal neurons of mouse hippocampal slices demonstrated that IL-18 stimulated synaptically released glutamate and enhanced postsynaptic AMPA receptor responses, thereby facilitating basal hippocampal synaptic transmission without affecting LTP [76].

Recently an ex vivo study found that LPS-induced IL-18 elevation in the brain was unable to affect LTP in the CA1 hippocampal subregion [77]. However, when comparing wild-type and IL-18 KO mice, the same study demonstrated that IL-18 regulates fear memory and spatial learning. In particular, assessment of spatial learning and memory with the water maze test showed that compared to wild-type mice IL-18 KO mice exhibit prolonged acquisition latency and that this phenotype was rescued by i.c.v. injection of IL-18.

Stress and the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis

IL-18 occupies a peculiar role in stress response both centrally and peripherally. This subject was recently extensively reviewed and we briefly refer to it here only for those aspects relevant to understanding of the central actions of this cytokine [78].

In response to restraint stress, IL-18 null mice showed a markedly reduced morphological microglial activation in the thalamus, hypothalamus, hippocampus, substantia nigra and central gray area [62]. In addition, IL-18 expression was elevated by restraint stress in the neurons of the medial habenula [56]. Since the habenula is a potential site for the interaction of neuro-endocrine and immune functions, the possibility exists that IL-18 might mediate the communication between the CNS and the periphery. Indeed, there is a general agreement that IL-18 may regulate hypothalamic-pituitary axis activity, possibly mediating the stress response of the adrenal gland [20,78,79]. In this respect, stress has been shown to induce transient IL-18 mRNA elevation in rat pituitary cells where increase of the IL-18 mRNA level was observed also after adrenalectomy [57].

IL-18 is also produced in the neurohypophysis [20] as well as in the adenohypophysis where in situ hybridization combined with immunohistochemistry demonstrated its expression in corticotrope cells [57]. In addition, bovine somatotropes have been shown to produce IL-18 and IL-18Rα was co-localized with IL-18, or growth hormone, suggesting the possibility that IL-18 acts on somatotropes through the autocrine pathway [80]. However, IL-18 seems to also act at the hypothalamic level. Indeed, the application of IL-18 in rat hypothalamic explants decreases basal and KCl-stimulated corticotropin-releasing hormones (CRH), as well as CRH gene expression [81]. In particular, the cytokine did not modify basal PGE2 production but abolished production stimulated by IL-1β demonstrating that IL-18 possesses a profile of in vitro neuroendocrine activities opposed to, and even antagonizing, those of IL-1β. Recently, IL-18 was localized in the marginal cell layer of the bovine and porcine Rathke's pouch, that is assumed to embody a stem/progenitor cell compartment of the postnatal pituitary gland [54,55]. Interestingly, stimulation of a cloned anterior pituitary-derived cell line (from the bovine anterior pituitary gland) with IL-18 increased expression of mRNAs of a different cytokine suggesting the possibility that IL-18 may modulate not only the immuno-endocrine function of the pituitary cells but also their development [55].

Microglia and neuroinflammation

Functional maturation and activation of IL-18 can occur in the brain under inflammatory conditions. Indeed, as extensively reviewed by Felderhoff-Mueser and colleagues [82], experimental and clinical studies suggest that binding of IL-18 occurs in several neuroinflammatory associated pathological conditions including microbial infections, focal cerebral ischemia, Wallerian degeneration and hypoxic-ischemic, hyperoxic and traumatic brain injuries (e.g., stroke). Further evidence comes from recent papers reporting an activation of IL-18 in the brain of mice that underwent thromboembolic stroke [83] or an increase of IL-18 levels after hypoxia-ischemia in the juvenile hippocampus of mice [84].

During CNS inflammation, the IL-18 system may have an important role in the activation and response of microglia and possibly infiltrating cells. As mentioned above, microglia cells can synthesize and respond to IL-18 [20,59-61]. IL-18 KO mice had impaired microglia activation with reduced expression of Ca2+-binding protein regulating phagocytic functions that resulted in reduced clearance of neurovirulent influenza A virus [85]. In the absence of infection IL-18 deficient mice also showed diminished stress-induced morphological microglial hypertrophy [62].

Interestingly, IL-1β is upregulated within 4 h of focal ischemia in rat brain, but IL-18 is upregulated much later, at time points associated with infiltration of peripheral immune cells, thus suggesting different roles for these interleukins in the regulation of glial functions [86]. In this respect, it was shown that mice infected with Japanese Encephalitis produce IL-18 and IL-1β from microglia and astroglia [59]. Both interleukins are capable of inducing pro-inflammatory cytokines and chemokines from human microglia and astroglia, although IL-18 seems to be more potent than IL-1β.

In the spinal cord, IL-18 seems to play a role in the innate inflammatory response. Indeed, moderate cervical contusive spinal cord injury induced processing of IL-18 in neurons of the rat spinal cord [87]. In addition, nerve injury induced a striking increase in IL-18 and IL-18R expression in the dorsal horn, and IL-18 and IL-18R were upregulated in hyperactive microglia and astrocytes, respectively [47,88]. Intrathecal injection of IL-18 induced behavioral, morphological, and biochemical changes similar to those observed after nerve injury [47], suggesting that IL-18-mediated microglia/astrocyte interactions in the spinal cord have a substantial role in the generation of tactile allodynia.

Autoimmune neurodegenerative disease

A pivotal role for IL-18, in the pathogenesis of autoimmune neurodegenerative disease has been proposed. High levels of IL-18 mRNA were found in the brain and the spinal cord of rats with experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis (EAE), an animal model of multiple sclerosis (MS) [89,90]. Elevated IL-18 transcript was found at the onset and throughout the course of the disease. A different study showed that IL-18 increases severity of EAE [91]. Moreover, it has been demonstrated that anti-IL-18 antibodies or targeted overexpression of IL-18BP in the CNS had preventive effects on the induction of EAE[90,92]. These observations suggested a role for IL-18 in MS, IL-18 KO mice were susceptible to EAE, whereas IL-18Rα KO mice or IL-18 KO mice treated with anti-IL-18Rα antibodies were not [93]. Thus, alternative IL-18Rα ligands with encephalitogenic properties may exist [93]. In EAE-susceptible Dark Agouti rats, the basal and post-immunization (day 5, 7 and 12) levels of IL-18Rα in lymph node cells were significantly higher than in the EAE-resistant Piebald Virol Glaxo rats [94].

In human, serum and cerebrospinal fluid levels of IL-18 are elevated in patients with MS [95-98] and IL-18 positive cells have been detected in demyelinating brain lesions from MS patients [99].

The pathological role of IL-18 in EAE is also supported by the up-regulation of caspase-1 (required to convert IL-18 precursor protein into its biologically active mature form) mRNA in the spinal cord of rats with EAE [89], and decreased disease severity in caspase-1 KO mice [100]. Finally, peripheral blood mononuclear cells from patients with MS have elevated caspase-1 mRNA levels [95,101].

In addition to a role in MS there is also evidence to support a function for IL-18 in the onset and progression of autoimmune CNS disease. For instance, infection of microglia lines with Theiler's murine encephalomyelitis virus (which causes the development of a chronic-progressive autoimmune demyelinating disease) significantly upregulates the expression of cytokines involved in innate immunity, including IL-18 [102].

Neurodegenerative disorders

Alzheimer's Disease (AD) is the most common type of human dementia. It is characterized clinically by a gradual but progressive decline in memory and pathologically by neuritic plaques, neuro-fibrillary tangles, and the loss of synapses and neurons [103]. Inflammatory processes were proposed to contribute to neurodegeneration in AD and extensive studies indicated that IL-1 is a pivotal cytokine in mediating direct neuronal loss and sustaining microglia activation leading to further cellular damage in AD [104]. Microglia-derived inflammatory cytokines can initiate nerve cell degeneration and enhance the plaque production typically found in AD [105]. Increasing evidence indicates that IL-18 may have a role in this scenario.

For instance, the levels of IL-18 transcript and protein were increased in the frontal lobe of AD patients compared to healthy age-matched controls. In these brains IL-18 was found in microglia, astrocytes and in neurons that co-localize with amyloid-β-plaques and with tau [106], suggesting that amyloid-β may induce the synthesis of IL-18, and IL-18 kinases involved in tau phosphorylation as a part of the amyloid-associated inflammatory reaction. Additionally, IL-18 can enhance protein levels of Cdk5/p35 and GSK-3β kinases, tau phosphorylation and cell cycle activators in neuron-like differentiated human SH-SY5Y neuroblastoma cells [50]. Thus, on a pathway leading to AD, IL-18 may have an impact on the hyperphosphorylation of tau but also on cell cycle related mechanisms. In the plasma, the levels of IL-18 were significantly elevated in patients with AD, vascular dementia, and mild cognitive impairment compared to the control group [107,108]. Interestingly, IL-18 levels were higher in AD-mild patients, were slightly lower in AD-moderate patients, whereas no significant difference was observed between AD-severe patients and non-demented age-matched subjects [109], suggesting a gradual decline of immune responsiveness in AD. Although other studies showed no differences in circulating IL-18 levels measured between AD patients (both mild cognitive impairment and severe AD patients) and controls [106,110,111], a significant increased production of IL-18 was obtained from stimulated blood mononuclear cells or macrophages of peripheral blood of AD patients [111,112]. Furthermore, a significant correlation between IL-18 peripheral production and cognitive decline was observed in AD patients. Overall, these data indicate that IL-18-related inflammatory pathways, are exacerbated in the peripheral blood of AD patients, and that this cytokine may indeed participate in pathogenic processes leading to dementia.

Genetic association studies reported that two functional polymorphisms (137G/C and -607C/A) in IL-18 promoter may increase the risk of developing sporadic late onset AD in the Han Chinese population [113]. An association between 137G/C and -607C/A polymorphisms and the susceptibility/clinical outcome of AD was also suggested in an Italian population [114], although these correlations remain controversial. Indeed, in another Italian population a lack of association between IL-18 gene promoter polymorphisms and onset of AD was reported, indicating that the association of IL-18 promoter polymorphisms with AD is not so strong, AD being a multifactorial disease [115]. Importantly, IL-18 promoter remains poorly characterized.

Finally, it has been hypothesized that increased production of IL-18 in the brain may lead to motor and cognitive dysfunctions, leading to the development of HIV-associated dementia. Thus, IL-18 concentrations in HIV-infected persons are likely to play an important role in the development and progression of the infection toward AIDS and associated clinical conditions [116].

In Parkinsonism, there is evidence of chronic inflammation in the substantia nigra and striatum. Activated microglia, producing proinflammatory cytokines, surround the degenerating dopaminergic neurons and may contribute to dopaminergic neuron loss. In an experimental model of Parkinson's disease that utilized injection of the dopaminergic specific neurotoxin MPTP the number of activated microglial cells in the substantia nigra pars compacta of IL-18 KO mice was reduced compared to wild-type [117], indicating the possibility that IL-18 may participate in microglial activation and dopaminergic neurodegeneration.

Neuropsychiatric disorders

Several groups found that depressed and schizophrenic patients have high circulating levels of pro-inflammatory cytokines [118-123]. Others reported that psychotic episodes often occur in conditions characterized by elevated levels of pro-inflammatory cytokines, for instance during inflammation or in patients suffering from immune diseases [124-127].

Other studies suggested that the correlation between inflammatory markers and psychiatric disorders may be more that merely associative, with inflammation actually contributing to mental disorders. Improvement in psychiatric symptoms has been recently reported in patients treated with anti-inflammatory drugs for other indications [128] and functional allelic variants of genes codifying for pro-inflammatory cytokines were associated with reduced responsiveness to antidepressant therapy [129,130]. It was also recently demonstrated that IL-6 plays a pivotal role in the pharmacological ketamine model of schizophrenia by modulating the NADPH-oxidase increase of superoxide affecting parvalbumin interneurons [131]. An interesting line of research is exploring the possibility that these actions may be developmental, with cytokines influencing early-life programming of brain functions [132].

At present evidence linking IL-18 and psychiatric disorders are primarily associative. IL-18 mRNA expression is elevated in subordinate rat models with depression with respect to dominant rats [133]. A significant elevation of circulating plasma levels of IL-18 has been reported in subjects affected by schizophrenia and were normalized by pharmacological treatment with risperidone, a dopamine antagonist with antipsychotic activity [134,135]. Normalization was demonstrated also within 6 month of treatment with the antipsychotic clozepine [134] although the possibility that these effects could be due to clozepine's effects on leukocyte numbers cannot be excluded. The serum levels of IL-18 were also significantly higher in moderate-severe depression patients, further suggesting that the pathophysiology of depression is associated with an inflammatory response involving IL-18 [136,137]. Coincidentally, IL-18 is also elevated after stroke, a condition followed by emotional disorders [138-140].

The significance of these correlations with respect to the role of the IL-18 system to neurophsychiatric disease pathophysiology or manifestation remains to be determined. Caution should be taken particularly since peripheral IL-18 can be subject to neurogenic stimulation or stress [20,78,141-143]. It is thus difficult to determine whether IL-18 elevation contributes to these pathologies or whether it is a consequence of the disorders. Indeed, Kokai and colleagues suggest that IL-18 can be considered a psychologic stress-associated marker since they demonstrated that exposure to stressful events (i.e., panic attack in human, restraint stress in mice), the most important precipitating factor in depression, induces a prompt increase in the level of circulating IL-18 [136].

Regardless, elevated IL-18 levels have the potential to contribute to several of the symptoms associated with neuropsychiatric disorders. For instance, like other pro-inflammatory cytokines, IL-18 may participate in the control of the activity of the HPA axis reported to be dysregulated in depression [78,144-146]. IL-18 may antagonize glucocorticoid signalling via activation of NF-κB and p38 MAPK possibly disrupting glucocorticoid-dependent negative feedback on the HPA axis [147-149]. Finally, IL-18 can affect other hallmarks of depression impairing learning and memory by acting as an attenuator of long-term potentiation, and inducing lethargy and loss of appetite [11,72,74].

Other central actions of IL-18

Three groups investigated the action of IL-18 in rodents following administration of KA, an agonist of the kainate receptors inducing seizure, cerebellar ataxia and exitotoxic mediated neuronal loss [53,60,150]. In mouse hippocampus KA elevated IL-18 and IL-18R expression on microglial cells progressively 3 days after treatment [60]. The authors hypothesized that similar to what was observed peripherally in studies of the immune system, IL-18 may contribute to cellular damage. This hypothesis was partially supported by another group showing that the KA-induced hippocampal neurodegeneration was shown to be more severe in IL-18 KO mice compared to wild-type littermates [150]. Yet, in recombinant mice with the same pre-treatment, IL-18 aggravated both the clinical and pathological signs of neurodegeneration in a dose-dependent manner.

In the cerebellum, where KA was demonstrate to induce ataxia partially via elevation of IL-1β, exogenous IL-18 was protective and played a positive role in the recovery from kainate-induced ataxia [53]. Consistently, IL-18 KO and IL-18Rα KO mice show delay in recovery from kainate-induced ataxia. The antagonizing effects of IL-18 and IL-1β also observed in the peripheral effects of IL-1β on fever, [73] are intriguing particularly since these cytokines share many similarities including their signalling. Preliminary observations suggest that these effects may be explained by IL-1β and IL-18 targeting different cells or activating distinct signalling [53].

Some groups have investigated the possibility that IL-18 could be used against glioma, a common and highly aggressive type of brain tumor with poor long-term prognosis [151]. In this respect, IL-18 was investigated alone or in synergism with IL-12 or Fas, for its ability to induce INFγ and NO inducing a cytotoxic response against glioma cells [152]. Systemic or intracerebral administration of IL-18 inhibited the growth of inoculated glioma cells and prolonged the survival of mice with subcutaneous or brain tumors, respectively [153]. Antitumor activity against glioma was also found in mice treated with IL-18 and IL-12 via Semliki Forest virus [154,155] or with a combination of IL-18 and Fas [156]. Finally, encouraging data were also reported by overexpressing IL-18 in mesenchymal cells of rats [157].

Conclusions

Investigation on the presence of IL-18 in the CNS began soon after its discovery as a co-stimulator of INF-γ production in the immune system [1,20,158,159]. Initially IL-18 was investigated for its similarities with IL-1β as a possible mediator of sickness behavior and of local inflammatory reactions associated with neuronal damage. These actions were both demonstrated and IL-18 was shown to promote loss of appetite, sleep and inhibition of LTP, as well as to be produced by and active in microglial cells, and to possibly contribute to neurodegenerative diseases.

Yet, two observations suggest that IL-18 has a central role and function that may be unique and distinct from those of IL-1β or other cytokines. The first being the recognition that Il-18 and Il-1β, when their combined action was tested, may have antagonizing effects such as those occurring in fever and in kainate-induced cerebellar ataxia. The second was the finding that IL-18R is constitutively and broadly expressed in neuronal cells throughout the rodent brain. This finding opened the possibility of a direct action of IL-18 on neuronal functions particularly in all of the CNS disorders showed to be correlated to elevated cytokine levels.

Thus, the investigation of the central action of IL-18 may be considered in its infancy and the significance of the neuronal IL-18R complex and of its isoforms remains to be determined. Among the intriguing peculiarities of the central role of IL-18 is that despite the constitutive expression of the receptor, the regulation of IL-18 action appears to be regulated by the existence of truncated isoforms and by the fact that under normal physiological conditions IL-18 is not easily found in the CNS. Interestingly, the genes encoding for IL-18 and its receptors are subject to differential promoter usage and their transcription to differential splicing indicating that these molecules have the potential of being produced in a tissue/cell specific way in response to different stimuli [26,78]. It will be important to determine which physiological or pathological conditions modulate these molecules.

Also unexplored is the investigation of the possible role of IL-18 in CNS development suggested by work on microglial cultures from newborn mice and brain homogenates where IL-18 was preferentially expressed during early postnatal stages and subsequently downregulated, being virtually absent in the brains of adult mice [61]. Additionally, the activated microglia-derived cytokines, including IL-18, may either inhibit the neuronal differentiation or induce neuronal cell death in the rat neural progenitor cell culture, which are cells capable of giving rise to various neuronal and glial cell populations in the developing and adult CNS [160]. Finally, in adult rodents IL-18 is produced in ependymal cells [56] considered a primary source of neural stem cells in response to injury [161]. The possible role of IL-18 in their differentiation has also not been investigated.

Work on existing IL-18 and IL-18R null mice as well as the development of new experimental models including CNS specific null or overexpressor mice and the identification of suitable in vitro systems will determine the specificity of the central effects of IL-18 in health and disease.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors' contributions

SA and DC wrote the initial draft of the manuscript, SS and BC contributed to its final version. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Contributor Information

Silvia Alboni, Email: salboni@libero.it.

Davide Cervia, Email: d.cervia@unitus.it.

Shuei Sugama, Email: sugama@nms.ac.jp.

Bruno Conti, Email: bconti@scripps.edu.

Acknowledgements

Supported by The Ellison Medical Foundation and NIH HL088083 and grant-in-aid for Science Research from the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science, and Technology, Japan (20500359).

References

- Okamura H, Tsutsi H, Komatsu T, Yutsudo M, Hakura A, Tanimoto T, Torigoe K, Okura T, Nukada Y, Hattori K. Cloning of a new cytokine that induces IFN-gamma production by T cells. Nature. 1995;378:88–91. doi: 10.1038/378088a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dinarello CA. IL-18: A TH1-inducing, proinflammatory cytokine and new member of the IL-1 family. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 1999;103:11–24. doi: 10.1016/S0091-6749(99)70518-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakanishi K, Yoshimoto T, Tsutsui H, Okamura H. Interleukin-18 is a unique cytokine that stimulates both Th1 and Th2 responses depending on its cytokine milieu. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev. 2001;12:53–72. doi: 10.1016/S1359-6101(00)00015-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arend WP, Palmer G, Gabay C. IL-1, IL-18, and IL-33 families of cytokines. Immunol Rev. 2008;223:20–38. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-065X.2008.00624.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boraschi D, Dinarello CA. IL-18 in autoimmunity: review. Eur Cytokine Netw. 2006;17:224–252. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park S, Cheon S, Cho D. The dual effects of interleukin-18 in tumor progression. Cell Mol Immunol. 2007;4:329–335. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dinarello CA. Interleukin-18 and the pathogenesis of inflammatory diseases. Semin Nephrol. 2007;27:98–114. doi: 10.1016/j.semnephrol.2006.09.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dinarello CA, Fantuzzi G. Interleukin-18 and host defense against infection. J Infect Dis. 2003;187(Suppl 2):S370–384. doi: 10.1086/374751. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kawakami K. Interleukin-18 and host defense against infectious pathogens. J Immunother. 2002;25(Suppl 1):S12–19. doi: 10.1097/00002371-200203001-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Netea MG, Joosten LA, Lewis E, Jensen DR, Voshol PJ, Kullberg BJ, Tack CJ, van Krieken H, Kim SH, Stalenhoef AF, Loo FA van de, Verschueren I, Pulawa L, Akira S, Eckel RH, Dinarello CA, Berg W van den, Meer JW van der. Deficiency of interleukin-18 in mice leads to hyperphagia, obesity and insulin resistance. Nat Med. 2006;12:650–656. doi: 10.1038/nm1415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zorrilla EP, Sanchez-Alavez M, Sugama S, Brennan M, Fernandez R, Bartfai T, Conti B. Interleukin-18 controls energy homeostasis by suppressing appetite and feed efficiency. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2007;104:11097–11102. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0611523104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Akita K, Ohtsuki T, Nukada Y, Tanimoto T, Namba M, Okura T, Takakura-Yamamoto R, Torigoe K, Gu Y, Su MS, Fujii M, Satoh-Itoh M, Yamamoto K, Kohno K, Ikeda M, Kurimoto M. Involvement of caspase-1 and caspase-3 in the production and processing of mature human interleukin 18 in monocytic THP.1 cells. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:26595–26603. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.42.26595. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fantuzzi G, Puren AJ, Harding MW, Livingston DJ, Dinarello CA. Interleukin-18 regulation of interferon gamma production and cell proliferation as shown in interleukin-1beta-converting enzyme (caspase-1)-deficient mice. Blood. 1998;91:2118–2125. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghayur T, Banerjee S, Hugunin M, Butler D, Herzog L, Carter A, Quintal L, Sekut L, Talanian R, Paskind M, Wong W, Kamen R, Tracey D, Allen H. Caspase-1 processes IFN-gamma-inducing factor and regulates LPS-induced IFN-gamma production. Nature. 1997;386:619–623. doi: 10.1038/386619a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gu Y, Kuida K, Tsutsui H, Ku G, Hsiao K, Fleming MA, Hayashi N, Higashino K, Okamura H, Nakanishi K. Activation of interferon-gamma inducing factor mediated by interleukin-1beta converting enzyme. Science. 1997;275:206–209. doi: 10.1126/science.275.5297.206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ushio S, Namba M, Okura T, Hattori K, Nukada Y, Akita K, Tanabe F, Konishi K, Micallef M, Fujii M. Cloning of the cDNA for human IFN-gamma-inducing factor, expression in Escherichia coli, and studies on the biologic activities of the protein. J Immunol. 1996;156:4274–4279. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fantuzzi G, Dinarello CA. Interleukin-18 and interleukin-1 beta: two cytokine substrates for ICE (caspase-1) J Clin Immunol. 1999;19:1–11. doi: 10.1023/A:1020506300324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gracie JA. Interleukin-18 as a potential target in inflammatory arthritis. Clin Exp Immunol. 2004;136:402–404. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2249.2004.02475.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sugawara S, Uehara A, Nochi T, Yamaguchi T, Ueda H, Sugiyama A, Hanzawa K, Kumagai K, Okamura H, Takada H. Neutrophil proteinase 3-mediated induction of bioactive IL-18 secretion by human oral epithelial cells. J Immunol. 2001;167:6568–6575. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.167.11.6568. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conti B, Jahng JW, Tinti C, Son JH, Joh TH. Induction of interferon-gamma inducing factor in the adrenal cortex. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:2035–2037. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.4.2035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang YJ, Wang ZY, Chen SH, Ge XR. Cloning and characterization of a new isoform of mouse interleukin-18. Acta Biochim Biophys Sin (Shanghai) 2005;37:826–834. doi: 10.1111/j.1745-7270.2005.00116.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O'Neill LA, Dinarello CA. The IL-1 receptor/toll-like receptor superfamily: crucial receptors for inflammation and host defense. Immunol Today. 2000;21:206–209. doi: 10.1016/S0167-5699(00)01611-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sims JE. IL-1 and IL-18 receptors, and their extended family. Curr Opin Immunol. 2002;14:117–122. doi: 10.1016/S0952-7915(01)00306-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sergi B, Penttila I. Interleukin 18 receptor. J Biol Regul Homeost Agents. 2004;18:55–61. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomassen E, Bird TA, Renshaw BR, Kennedy MK, Sims JE. Binding of interleukin-18 to the interleukin-1 receptor homologous receptor IL-1Rrp1 leads to activation of signaling pathways similar to those used by interleukin-1. J Interferon Cytokine Res. 1998;18:1077–1088. doi: 10.1089/jir.1998.18.1077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alboni S, Cervia D, Ross B, Montanari C, Gonzalez AS, Sanchez-Alavez M, Marcondes MC, De Vries D, Sugama S, Brunello N. Mapping of the full length and the truncated interleukin-18 receptor alpha in the mouse brain. J Neuroimmunol. 2009;214:43–54. doi: 10.1016/j.jneuroim.2009.06.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colotta F, Dower SK, Sims JE, Mantovani A. The type II 'decoy' receptor: a novel regulatory pathway for interleukin 1. Immunol Today. 1994;15:562–566. doi: 10.1016/0167-5699(94)90217-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andre R, Wheeler RD, Collins PD, Luheshi GN, Pickering-Brown S, Kimber I, Rothwell NJ, Pinteaux E. Identification of a truncated IL-18R beta mRNA: a putative regulator of IL-18 expressed in rat brain. J Neuroimmunol. 2003;145:40–45. doi: 10.1016/j.jneuroim.2003.09.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fiszer D, Rozwadowska N, Rychlewski L, Kosicki W, Kurpisz M. Identification of IL-18RAP mRNA truncated splice variants in human testis and the other human tissues. Cytokine. 2007;39:178–183. doi: 10.1016/j.cyto.2007.07.186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Im SH, Kim SH, Azam T, Venkatesh N, Dinarello CA, Fuchs S, Souroujon MC. Rat interleukin-18 binding protein: cloning, expression, and characterization. J Interferon Cytokine Res. 2002;22:321–328. doi: 10.1089/107999002753675749. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim SH, Azam T, Novick D, Yoon DY, Reznikov LL, Bufler P, Rubinstein M, Dinarello CA. Identification of amino acid residues critical for biological activity in human interleukin-18. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:10998–11003. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M108311200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Novick D, Kim SH, Fantuzzi G, Reznikov LL, Dinarello CA, Rubinstein M. Interleukin-18 binding protein: a novel modulator of the Th1 cytokine response. Immunity. 1999;10:127–136. doi: 10.1016/S1074-7613(00)80013-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim SH, Eisenstein M, Reznikov L, Fantuzzi G, Novick D, Rubinstein M, Dinarello CA. Structural requirements of six naturally occurring isoforms of the IL-18 binding protein to inhibit IL-18. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2000;97:1190–1195. doi: 10.1073/pnas.97.3.1190. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bufler P, Azam T, Gamboni-Robertson F, Reznikov LL, Kumar S, Dinarello CA, Kim SH. A complex of the IL-1 homologue IL-1F7b and IL-18-binding protein reduces IL-18 activity. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2002;99:13723–13728. doi: 10.1073/pnas.212519099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Busfield SJ, Comrack CA, Yu G, Chickering TW, Smutko JS, Zhou H, Leiby KR, Holmgren LM, Gearing DP, Pan Y. Identification and gene organization of three novel members of the IL-1 family on human chromosome 2. Genomics. 2000;66:213–216. doi: 10.1006/geno.2000.6184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumar S, McDonnell PC, Lehr R, Tierney L, Tzimas MN, Griswold DE, Capper EA, Tal-Singer R, Wells GI, Doyle ML, Young PR. Identification and initial characterization of four novel members of the interleukin-1 family. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:10308–10314. doi: 10.1074/jbc.275.14.10308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pan G, Risser P, Mao W, Baldwin DT, Zhong AW, Filvaroff E, Yansura D, Lewis L, Eigenbrot C, Henzel WJ, Vandlen R. IL-1H, an interleukin 1-related protein that binds IL-18 receptor/IL-1Rrp. Cytokine. 2001;13:1–7. doi: 10.1006/cyto.2000.0799. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith DE, Renshaw BR, Ketchem RR, Kubin M, Garka KE, Sims JE. Four new members expand the interleukin-1 superfamily. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:1169–1175. doi: 10.1074/jbc.275.2.1169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor SL, Renshaw BR, Garka KE, Smith DE, Sims JE. Genomic organization of the interleukin-1 locus. Genomics. 2002;79:726–733. doi: 10.1006/geno.2002.6752. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumar S, Hanning CR, Brigham-Burke MR, Rieman DJ, Lehr R, Khandekar S, Kirkpatrick RB, Scott GF, Lee JC, Lynch FJ. Interleukin-1F7B (IL-1H4/IL-1F7) is processed by caspase-1 and mature IL-1F7B binds to the IL-18 receptor but does not induce IFN-gamma production. Cytokine. 2002;18:61–71. doi: 10.1006/cyto.2002.0873. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dinarello CA. Interleukin-18, a proinflammatory cytokine. Eur Cytokine Netw. 2000;11:483–486. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gracie JA, Robertson SE, McInnes IB. Interleukin-18. J Leukoc Biol. 2003;73:213–224. doi: 10.1189/jlb.0602313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shimoda K, Tsutsui H, Aoki K, Kato K, Matsuda T, Numata A, Takase K, Yamamoto T, Nukina H, Hoshino T. Partial impairment of interleukin-12 (IL-12) and IL-18 signaling in Tyk2-deficient mice. Blood. 2002;99:2094–2099. doi: 10.1182/blood.V99.6.2094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kalina U, Kauschat D, Koyama N, Nuernberger H, Ballas K, Koschmieder S, Bug G, Hofmann WK, Hoelzer D, Ottmann OG. IL-18 activates STAT3 in the natural killer cell line 92, augments cytotoxic activity, and mediates IFN-gamma production by the stress kinase p38 and by the extracellular regulated kinases p44erk-1 and p42erk-21. J Immunol. 2000;165:1307–1313. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.165.3.1307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chandrasekar B, Patel DN, Mummidi S, Kim JW, Clark RA, Valente AJ. Interleukin-18 suppresses adiponectin expression in 3T3-L1 adipocytes via a novel signal transduction pathway involving ERK1/2-dependent NFATc4 phosphorylation. J Biol Chem. 2008;283:4200–4209. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M708142200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fortin CF, Ear T, McDonald PP. Autocrine role of endogenous interleukin-18 on inflammatory cytokine generation by human neutrophils. Faseb J. 2009;23:194–203. doi: 10.1096/fj.08-110213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miyoshi K, Obata K, Kondo T, Okamura H, Noguchi K. Interleukin-18-mediated microglia/astrocyte interaction in the spinal cord enhances neuropathic pain processing after nerve injury. J Neurosci. 2008;28:12775–12787. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3512-08.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cumiskey D, Pickering M, O'Connor JJ. Interleukin-18 mediated inhibition of LTP in the rat dentate gyrus is attenuated in the presence of mGluR antagonists. Neurosci Lett. 2007;412:206–210. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2006.11.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Curran BP, Murray HJ, O'Connor JJ. A role for c-Jun N-terminal kinase in the inhibition of long-term potentiation by interleukin-1beta and long-term depression in the rat dentate gyrus in vitro. Neuroscience. 2003;118:347–357. doi: 10.1016/S0306-4522(02)00941-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ojala JO, Sutinen EM, Salminen A, Pirttila T. Interleukin-18 increases expression of kinases involved in tau phosphorylation in SH-SY5Y neuroblastoma cells. J Neuroimmunol. 2008;205:86–93. doi: 10.1016/j.jneuroim.2008.09.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Culhane AC, Hall MD, Rothwell NJ, Luheshi GN. Cloning of rat brain interleukin-18 cDNA. Mol Psychiatry. 1998;3:362–366. doi: 10.1038/sj.mp.4000389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wheeler RD, Culhane AC, Hall MD, Pickering-Brown S, Rothwell NJ, Luheshi GN. Detection of the interleukin 18 family in rat brain by RT-PCR. Brain Res Mol Brain Res. 2000;77:290–293. doi: 10.1016/S0169-328X(00)00069-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andoh T, Kishi H, Motoki K, Nakanishi K, Kuraishi Y, Muraguchi A. Protective effect of IL-18 on kainate- and IL-1 beta-induced cerebellar ataxia in mice. J Immunol. 2008;180:2322–2328. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.180.4.2322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nagai Y, Ogasawara H, Taketa Y, Aso H, Kanaya T, Miyake M, Watanabe K, Ohwada S, Muneta Y, Yamaguchi T. Expression of inflammatory-related factors in porcine anterior pituitary-derived cell line. Vet Immunol Immunopathol. 2008;124:201–208. doi: 10.1016/j.vetimm.2008.03.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nagai Y, Ogasawara H, Taketa Y, Aso H, Tanaka S, Kanaya T, Watanabe K, Ohwada S, Muneta Y, Yamaguchi T. Bovine anterior pituitary progenitor cell line expresses interleukin (IL)-18 and IL-18 receptor. J Neuroendocrinol. 2008;20:1233–1241. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2826.2008.01779.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sugama S, Cho BP, Baker H, Joh TH, Lucero J, Conti B. Neurons of the superior nucleus of the medial habenula and ependymal cells express IL-18 in rat CNS. Brain Res. 2002;958:1–9. doi: 10.1016/S0006-8993(02)03363-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang N, Sugama S, Conti B, Teramoto A, Shibasaki T. Interleukin-18 mRNA expression in the rat pituitary gland. J Neuroimmunol. 2006;173:117–125. doi: 10.1016/j.jneuroim.2005.12.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conti B, Park LC, Calingasan NY, Kim Y, Kim H, Bae Y, Gibson GE, Joh TH. Cultures of astrocytes and microglia express interleukin 18. Brain Res Mol Brain Res. 1999;67:46–52. doi: 10.1016/S0169-328X(99)00034-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Das S, Mishra MK, Ghosh J, Basu A. Japanese Encephalitis Virus infection induces IL-18 and IL-1beta in microglia and astrocytes: correlation with in vitro cytokine responsiveness of glial cells and subsequent neuronal death. J Neuroimmunol. 2008;195:60–72. doi: 10.1016/j.jneuroim.2008.01.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jeon GS, Park SK, Park SW, Kim DW, Chung CK, Cho SS. Glial expression of interleukin-18 and its receptor after excitotoxic damage in the mouse hippocampus. Neurochem Res. 2008;33:179–184. doi: 10.1007/s11064-007-9434-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prinz M, Hanisch UK. Murine microglial cells produce and respond to interleukin-18. J Neurochem. 1999;72:2215–2218. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.1999.0722215.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sugama S, Fujita M, Hashimoto M, Conti B. Stress induced morphological microglial activation in the rodent brain: involvement of interleukin-18. Neuroscience. 2007;146:1388–1399. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2007.02.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suk K, Yeou Kim S, Kim H. Regulation of IL-18 production by IFN gamma and PGE2 in mouse microglial cells: involvement of NF-kB pathway in the regulatory processes. Immunol Lett. 2001;77:79–85. doi: 10.1016/S0165-2478(01)00209-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parnet P, Garka KE, Bonnert TP, Dower SK, Sims JE. IL-1Rrp is a novel receptor-like molecule similar to the type I interleukin-1 receptor and its homologues T1/ST2 and IL-1R AcP. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:3967–3970. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.10.5777. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Born TL, Thomassen E, Bird TA, Sims JE. Cloning of a novel receptor subunit, AcPL, required for interleukin-18 signaling. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:29445–29450. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.45.29445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Otsuki M, Kusumoto K, Murakami Y, Kanayama M, Takeuchi S, Takahashi S. Expression of interleukin-18 receptor mRNA in the mouse endometrium. J Reprod Dev. 2007;53:59–68. doi: 10.1262/jrd.18036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hedtjarn M, Leverin AL, Eriksson K, Blomgren K, Mallard C, Hagberg H. Interleukin-18 involvement in hypoxic-ischemic brain injury. J Neurosci. 2002;22:5910–5919. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.22-14-05910.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wheeler RD, Brough D, Le Feuvre RA, Takeda K, Iwakura Y, Luheshi GN, Rothwell NJ. Interleukin-18 induces expression and release of cytokines from murine glial cells: interactions with interleukin-1 beta. J Neurochem. 2003;85:1412–1420. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.2003.01787.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dantzer R, Bluthe RM, Gheusi G, Cremona S, Laye S, Parnet P, Kelley KW. Molecular basis of sickness behavior. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1998;856:132–138. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1998.tb08321.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dantzer R, Kelley KW. Twenty years of research on cytokine-induced sickness behavior. Brain Behav Immun. 2007;21:153–160. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2006.09.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dantzer R, O'Connor JC, Freund GG, Johnson RW, Kelley KW. From inflammation to sickness and depression: when the immune system subjugates the brain. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2008;9:46–56. doi: 10.1038/nrn2297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kubota T, Fang J, Brown RA, Krueger JM. Interleukin-18 promotes sleep in rabbits and rats. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2001;281:R828–838. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.2001.281.3.R828. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gatti S, Beck J, Fantuzzi G, Bartfai T, Dinarello CA. Effect of interleukin-18 on mouse core body temperature. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2002;282:R702–709. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00393.2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cumiskey D, Curran BP, Herron CE, O'Connor JJ. A role for inflammatory mediators in the IL-18 mediated attenuation of LTP in the rat dentate gyrus. Neuropharmacology. 2007;52:1616–1623. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2007.03.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Curran B, O'Connor JJ. The pro-inflammatory cytokine interleukin-18 impairs long-term potentiation and NMDA receptor-mediated transmission in the rat hippocampus in vitro. Neuroscience. 2001;108:83–90. doi: 10.1016/S0306-4522(01)00405-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kanno T, Nagata T, Yamamoto S, Okamura H, Nishizaki T. Interleukin-18 stimulates synaptically released glutamate and enhances postsynaptic AMPA receptor responses in the CA1 region of mouse hippocampal slices. Brain Res. 2004;1012:190–193. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2004.03.065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yaguchi T, Nagata T, Yang D, Nishizaki T. Interleukin-18 regulates motor activity, anxiety and spatial learning without affecting synaptic plasticity. Behav Brain Res. 2010;206:47–51. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2009.08.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sugama S, Conti B. Interleukin-18 and stress. Brain Res Rev. 2008;58:85–95. doi: 10.1016/j.brainresrev.2007.11.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sekiyama A, Ueda H, Kashiwamura S, Nishida K, Kawai K, Teshima-kondo S, Rokutan K, Okamura H. IL-18; a cytokine translates a stress into medical science. J Med Invest. 2005;52(Suppl):236–239. doi: 10.2152/jmi.52.236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nagai Y, Nochi T, Watanabe K, Aso H, Kitazawa H, Matsuzaki M, Ohwada S, Yamaguchi T. Localization of interleukin-18 and its receptor in somatotrophs of the bovine anterior pituitary gland. Cell Tissue Res. 2005;322:455–462. doi: 10.1007/s00441-005-0016-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tringali G, Pozzoli G, Vairano M, Mores N, Preziosi P, Navarra P. Interleukin-18 displays effects opposite to those of interleukin-1 in the regulation of neuroendocrine stress axis. J Neuroimmunol. 2005;160:61–67. doi: 10.1016/j.jneuroim.2004.10.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Felderhoff-Mueser U, Schmidt OI, Oberholzer A, Buhrer C, Stahel PF. IL-18: a key player in neuroinflammation and neurodegeneration? Trends Neurosci. 2005;28:487–493. doi: 10.1016/j.tins.2005.06.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Abulafia DP, de Rivero Vaccari JP, Lozano JD, Lotocki G, Keane RW, Dietrich WD. Inhibition of the inflammasome complex reduces the inflammatory response after thromboembolic stroke in mice. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2009;29:534–544. doi: 10.1038/jcbfm.2008.143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qiu L, Zhu C, Wang X, Xu F, Eriksson PS, Nilsson M, Cooper-Kuhn CM, Kuhn HG, Blomgren K. Less neurogenesis and inflammation in the immature than in the juvenile brain after cerebral hypoxia-ischemia. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2007;27:785–794. doi: 10.1038/sj.jcbfm.9600385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mori I, Hossain MJ, Takeda K, Okamura H, Imai Y, Kohsaka S, Kimura Y. Impaired microglial activation in the brain of IL-18-gene-disrupted mice after neurovirulent influenza A virus infection. Virology. 2001;287:163–170. doi: 10.1006/viro.2001.1029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jander S, Schroeter M, Stoll G. Interleukin-18 expression after focal ischemia of the rat brain: association with the late-stage inflammatory response. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2002;22:62–70. doi: 10.1097/00004647-200201000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Rivero Vaccari JP, Lotocki G, Marcillo AE, Dietrich WD, Keane RW. A molecular platform in neurons regulates inflammation after spinal cord injury. J Neurosci. 2008;28:3404–3414. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0157-08.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xie WR, Deng H, Li H, Bowen TL, Strong JA, Zhang JM. Robust increase of cutaneous sensitivity, cytokine production and sympathetic sprouting in rats with localized inflammatory irritation of the spinal ganglia. Neuroscience. 2006;142:809–822. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2006.06.045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jander S, Stoll G. Differential induction of interleukin-12, interleukin-18, and interleukin-1beta converting enzyme mRNA in experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis of the Lewis rat. J Neuroimmunol. 1998;91:93–99. doi: 10.1016/S0165-5728(98)00162-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wildbaum G, Youssef S, Grabie N, Karin N. Neutralizing antibodies to IFN-gamma-inducing factor prevent experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis. J Immunol. 1998;161:6368–6374. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shi FD, Takeda K, Akira S, Sarvetnick N, Ljunggren HG. IL-18 directs autoreactive T cells and promotes autodestruction in the central nervous system via induction of IFN-gamma by NK cells. J Immunol. 2000;165:3099–3104. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.165.6.3099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schif-Zuck S, Westermann J, Netzer N, Zohar Y, Meiron M, Wildbaum G, Karin N. Targeted overexpression of IL-18 binding protein at the central nervous system overrides flexibility in functional polarization of antigen-specific Th2 cells. J Immunol. 2005;174:4307–4315. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.174.7.4307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gutcher I, Urich E, Wolter K, Prinz M, Becher B. Interleukin 18-independent engagement of interleukin 18 receptor-alpha is required for autoimmune inflammation. Nat Immunol. 2006;7:946–953. doi: 10.1038/ni1377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thessen Hedreul M, Gillett A, Olsson T, Jagodic M, Harris RA. Characterization of Multiple Sclerosis candidate gene expression kinetics in rat experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis. J Neuroimmunol. 2009;210:30–39. doi: 10.1016/j.jneuroim.2009.02.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang WX, Huang P, Hillert J. Increased expression of caspase-1 and interleukin-18 in peripheral blood mononuclear cells in patients with multiple sclerosis. Mult Scler. 2004;10:482–487. doi: 10.1191/1352458504ms1071oa. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karni A, Koldzic DN, Bharanidharan P, Khoury SJ, Weiner HL. IL-18 is linked to raised IFN-gamma in multiple sclerosis and is induced by activated CD4(+) T cells via CD40-CD40 ligand interactions. J Neuroimmunol. 2002;125:134–140. doi: 10.1016/S0165-5728(02)00018-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Losy J, Niezgoda A. IL-18 in patients with multiple sclerosis. Acta Neurol Scand. 2001;104:171–173. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0404.2001.00356.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nicoletti F, Di Marco R, Mangano K, Patti F, Reggio E, Nicoletti A, Bendtzen K, Reggio A. Increased serum levels of interleukin-18 in patients with multiple sclerosis. Neurology. 2001;57:342–344. doi: 10.1212/wnl.57.2.342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balashov KE, Rottman JB, Weiner HL, Hancock WW. CCR5(+) and CXCR3(+) T cells are increased in multiple sclerosis and their ligands MIP-1alpha and IP-10 are expressed in demyelinating brain lesions. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1999;96:6873–6878. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.12.6873. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Furlan R, Martino G, Galbiati F, Poliani PL, Smiroldo S, Bergami A, Desina G, Comi G, Flavell R, Su MS, Adorini L. Caspase-1 regulates the inflammatory process leading to autoimmune demyelination. J Immunol. 1999;163:2403–2409. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Furlan R, Filippi M, Bergami A, Rocca MA, Martinelli V, Poliani PL, Grimaldi LM, Desina G, Comi G, Martino G. Peripheral levels of caspase-1 mRNA correlate with disease activity in patients with multiple sclerosis; a preliminary study. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 1999;67:785–788. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.67.6.785. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olson JK, Girvin AM, Miller SD. Direct activation of innate and antigen-presenting functions of microglia following infection with Theiler's virus. J Virol. 2001;75:9780–9789. doi: 10.1128/JVI.75.20.9780-9789.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caselli RJ, Beach TG, Yaari R, Reiman EM. Alzheimer's disease a century later. J Clin Psychiatry. 2006;67:1784–1800. doi: 10.4088/JCP.v67n1118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Griffin WS. Inflammation and neurodegenerative diseases. Am J Clin Nutr. 2006;83:470S–474S. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/83.2.470S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aarli JA. Role of cytokines in neurological disorders. Curr Med Chem. 2003;10:1931–1937. doi: 10.2174/0929867033456918. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ojala J, Alafuzoff I, Herukka SK, van Groen T, Tanila H, Pirttila T. Expression of interleukin-18 is increased in the brains of Alzheimer's disease patients. Neurobiol Aging. 2009;30:198–209. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2007.06.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malaguarnera L, Motta M, Di Rosa M, Anzaldi M, Malaguarnera M. Interleukin-18 and transforming growth factor-beta 1 plasma levels in Alzheimer's disease and vascular dementia. Neuropathology. 2006;26:307–312. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1789.2006.00701.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ozturk C, Ozge A, Yalin OO, Yilmaz IA, Delialioglu N, Yildiz C, Tesdelen B, Kudiaki C. The diagnostic role of serum inflammatory and soluble proteins on dementia subtypes: correlation with cognitive and functional decline. Behav Neurol. 2007;18:207–215. doi: 10.1155/2007/432190. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Motta M, Imbesi R, Di Rosa M, Stivala F, Malaguarnera L. Altered plasma cytokine levels in Alzheimer's disease: correlation with the disease progression. Immunol Lett. 2007;114:46–51. doi: 10.1016/j.imlet.2007.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lindberg C, Chromek M, Ahrengart L, Brauner A, Schultzberg M, Garlind A. Soluble interleukin-1 receptor type II, IL-18 and caspase-1 in mild cognitive impairment and severe Alzheimer's disease. Neurochem Int. 2005;46:551–557. doi: 10.1016/j.neuint.2005.01.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bossu P, Ciaramella A, Salani F, Bizzoni F, Varsi E, Di Iulio F, Giubilei F, Gianni W, Trequattrini A, Moro ML. Interleukin-18 produced by peripheral blood cells is increased in Alzheimer's disease and correlates with cognitive impairment. Brain Behav Immun. 2008;22:487–492. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2007.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Di Rosa M, Dell'Ombra N, Zambito AM, Malaguarnera M, Nicoletti F, Malaguarnera L. Chitotriosidase and inflammatory mediator levels in Alzheimer's disease and cerebrovascular dementia. Eur J Neurosci. 2006;23:2648–2656. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2006.04780.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu JT, Tan L, Song JH, Sun YP, Chen W, Miao D, Tian Y. Interleukin-18 promoter polymorphisms and risk of late onset Alzheimer's disease. Brain Res. 2009;1253:169–175. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2008.11.083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bossu P, Ciaramella A, Moro ML, Bellincampi L, Bernardini S, Federici G, Trequattrini A, Macciardi F, Spoletini I, Di Iulio F. Interleukin 18 gene polymorphisms predict risk and outcome of Alzheimer's disease. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2007;78:807–811. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.2006.103242. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Segat L, Milanese M, Arosio B, Vergani C, Crovella S. Lack of association between Interleukin-18 gene promoter polymorphisms and onset of Alzheimer's disease. Neurobiol Aging. 2008;31:162–164. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2008.03.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iannello A, Samarani S, Debbeche O, Tremblay C, Toma E, Boulassel MR, Routy JP, Ahmad A. Role of interleukin-18 in the development and pathogenesis of AIDS. AIDS Rev. 2009;11:115–125. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sugama S, Wirz SA, Barr AM, Conti B, Bartfai T, Shibasaki T. Interleukin-18 null mice show diminished microglial activation and reduced dopaminergic neuron loss following acute 1-methyl-4-phenyl-1,2,3,6-tetrahydropyridine treatment. Neuroscience. 2004;128:451–458. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2004.07.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corcos M, Guilbaud O, Hjalmarsson L, Chambry J, Jeammet P. Cytokines and depression: an analogic approach. Biomed Pharmacother. 2002;56:105–110. doi: 10.1016/S0753-3322(01)00156-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dinan TG. Inflammatory markers in depression. Curr Opin Psychiatry. 2009;22:32–36. doi: 10.1097/YCO.0b013e328315a561. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ganguli R, Yang Z, Shurin G, Chengappa KN, Brar JS, Gubbi AV, Rabin BS. Serum interleukin-6 concentration in schizophrenia: elevation associated with duration of illness. Psychiatry Res. 1994;51:1–10. doi: 10.1016/0165-1781(94)90042-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Licinio J, Wong ML. The role of inflammatory mediators in the biology of major depression: central nervous system cytokines modulate the biological substrate of depressive symptoms, regulate stress-responsive systems, and contribute to neurotoxicity and neuroprotection. Mol Psychiatry. 1999;4:317–327. doi: 10.1038/sj.mp.4000586. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Myint AM, Kim YK. Cytokine-serotonin interaction through IDO: a neurodegeneration hypothesis of depression. Med Hypotheses. 2003;61:519–525. doi: 10.1016/S0306-9877(03)00207-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saetre P, Emilsson L, Axelsson E, Kreuger J, Lindholm E, Jazin E. Inflammation-related genes up-regulated in schizophrenia brains. BMC Psychiatry. 2007;7:46. doi: 10.1186/1471-244X-7-46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Appels A, Bar FW, Bar J, Bruggeman C, de Baets M. Inflammation, depressive symptomtology, and coronary artery disease. Psychosom Med. 2000;62:601–605. doi: 10.1097/00006842-200009000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eisner MD, Katz PP, Lactao G, Iribarren C. Impact of depressive symptoms on adult asthma outcomes. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2005;94:566–574. doi: 10.1016/S1081-1206(10)61135-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muller N, Gizycki-Nienhaus B, Gunther W, Meurer M. Depression as a cerebral manifestation of scleroderma: immunological findings in serum and cerebrospinal fluid. Biol Psychiatry. 1992;31:1151–1156. doi: 10.1016/0006-3223(92)90160-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O'Reilly RL, Singh SM. Retroviruses and schizophrenia revisited. Am J Med Genet. 1996;67:19–24. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1096-8628(19960216)67:1<19::AID-AJMG3>3.0.CO;2-N. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muller N, Strassnig M, Schwarz MJ, Ulmschneider M, Riedel M. COX-2 inhibitors as adjunctive therapy in schizophrenia. Expert Opin Investig Drugs. 2004;13:1033–1044. doi: 10.1517/13543784.13.8.1033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu YW, Chen TJ, Hong CJ, Chen HM, Tsai SJ. Association study of the interleukin-1 beta (C-511T) genetic polymorphism with major depressive disorder, associated symptomatology, and antidepressant response. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2003;28:1182–1185. doi: 10.1038/sj.npp.1300172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jun TY, Pae CU, Hoon H, Chae JH, Bahk WM, Kim KS, Serretti A. Possible association between -G308A tumour necrosis factor-alpha gene polymorphism and major depressive disorder in the Korean population. Psychiatr Genet. 2003;13:179–181. doi: 10.1097/00041444-200309000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Behrens MM, Ali SS, Dugan LL. Interleukin-6 mediates the increase in NADPH-oxidase in the ketamine model of schizophrenia. J Neurosci. 2008;28:13957–13966. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4457-08.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bilbo SD, Schwarz JM. Early-life programming of later-life brain and behavior: a critical role for the immune system. Front Behav Neurosci. 2009;3:14. doi: 10.3389/neuro.08.014.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kroes RA, Panksepp J, Burgdorf J, Otto NJ, Moskal JR. Modeling depression: social dominance-submission gene expression patterns in rat neocortex. Neuroscience. 2006;137:37–49. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2005.08.076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu LX, Guo SQ, Chen W, Li Q, Cheng J, Guo JH. [Effect of clozapine and risperidone on serum cytokine levels in patients with first-episode paranoid schizophrenia] Di Yi Jun Yi Da Xue Xue Bao. 2004;24:1251–1254. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tanaka KF, Shintani F, Fujii Y, Yagi G, Asai M. Serum interleukin-18 levels are elevated in schizophrenia. Psychiatry Res. 2000;96:75–80. doi: 10.1016/S0165-1781(00)00196-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kokai M, Kashiwamura S, Okamura H, Ohara K, Morita Y. Plasma interleukin-18 levels in patients with psychiatric disorders. J Immunother. 2002;25(Suppl 1):S68–71. doi: 10.1097/00002371-200203001-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Merendino RA, Di Rosa AE, Di Pasquale G, Minciullo PL, Mangraviti C, Costantino A, Ruello A, Gangemi S. Interleukin-18 and CD30 serum levels in patients with moderate-severe depression. Mediators Inflamm. 2002;11:265–267. doi: 10.1080/096293502900000131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spalletta G, Bossu P, Ciaramella A, Bria P, Caltagirone C, Robinson RG. The etiology of poststroke depression: a review of the literature and a new hypothesis involving inflammatory cytokines. Mol Psychiatry. 2006;11:984–991. doi: 10.1038/sj.mp.4001879. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bossu P, Salani F, Cacciari C, Picchetto L, Cao M, Bizzoni F, Rasura M, Caltagirone C, Robinson RG, Orzi F, Spalletta G. Disease outcome, alexithymia and depression are differently associated with serum IL-18 levels in acute stroke. Curr Neurovasc Res. 2009;6:163–170. doi: 10.2174/156720209788970036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fang J, Cheng Q. Etiological mechanisms of post-stroke depression: a review. Neurol Res. 2009;31:904–909. doi: 10.1179/174313209X385752. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sugama S, Kim Y, Baker H, Tinti C, Kim H, Joh TH, Conti B. Tissue-specific expression of rat IL-18 gene and response to adrenocorticotropic hormone treatment. J Immunol. 2000;165:6287–6292. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.165.11.6287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sugama S, Wang N, Shimokawa N, Koibuchi N, Fujita M, Hashimoto M, Dhabhar FS, Conti B. The adrenal gland is a source of stress-induced circulating IL-18. J Neuroimmunol. 2006;172:59–65. doi: 10.1016/j.jneuroim.2005.11.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sekiyama A, Ueda H, Kashiwamura S, Nishida K, Yamaguchi S, Sasaki H, Kuwano Y, Kawai K, Teshima-Kondo S, Rokutan K, Okamura H. A role of the adrenal gland in stress-induced up-regulation of cytokines in plasma. J Neuroimmunol. 2006;171:38–44. doi: 10.1016/j.jneuroim.2005.09.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maes M, Bosmans E, Meltzer HY, Scharpe S, Suy E. Interleukin-1 beta: a putative mediator of HPA axis hyperactivity in major depression? Am J Psychiatry. 1993;150:1189–1193. doi: 10.1176/ajp.150.8.1189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maes M, Scharpe S, Meltzer HY, Bosmans E, Suy E, Calabrese J, Cosyns P. Relationships between interleukin-6 activity, acute phase proteins, and function of the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis in severe depression. Psychiatry Res. 1993;49:11–27. doi: 10.1016/0165-1781(93)90027-E. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pariante CM, Pearce BD, Pisell TL, Sanchez CI, Po C, Su C, Miller AH. The proinflammatory cytokine, interleukin-1alpha, reduces glucocorticoid receptor translocation and function. Endocrinology. 1999;140:4359–4366. doi: 10.1210/en.140.9.4359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKay LI, Cidlowski JA. Molecular control of immune/inflammatory responses: interactions between nuclear factor-kappa B and steroid receptor-signaling pathways. Endocr Rev. 1999;20:435–459. doi: 10.1210/er.20.4.435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang X, Wu H, Miller AH. Interleukin 1alpha (IL-1alpha) induced activation of p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase inhibits glucocorticoid receptor function. Mol Psychiatry. 2004;9:65–75. doi: 10.1038/sj.mp.4001339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pariante CM, Lightman SL. The HPA axis in major depression: classical theories and new developments. Trends Neurosci. 2008;31:464–468. doi: 10.1016/j.tins.2008.06.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang XM, Duan RS, Chen Z, Quezada HC, Mix E, Winblad B, Zhu J. IL-18 deficiency aggravates kainic acid-induced hippocampal neurodegeneration in C57BL/6 mice due to an overcompensation by IL-12. Exp Neurol. 2007;205:64–73. doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2007.01.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sarin H. Recent progress towards development of effective systemic chemotherapy for the treatment of malignant brain tumors. J Transl Med. 2009;7:77. doi: 10.1186/1479-5876-7-77. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kito T, Kuroda E, Yokota A, Yamashita U. Cytotoxicity in glioma cells due to interleukin-12 and interleukin-18-stimulated macrophages mediated by interferon-gamma-regulated nitric oxide. J Neurosurg. 2003;98:385–392. doi: 10.3171/jns.2003.98.2.0385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kikuchi T, Akasaki Y, Joki T, Abe T, Kurimoto M, Ohno T. Antitumor activity of interleukin-18 on mouse glioma cells. J Immunother. 2000;23:184–189. doi: 10.1097/00002371-200003000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamanaka R, Tsuchiya N, Yajima N, Honma J, Hasegawa H, Tanaka R, Ramsey J, Blaese RM, Xanthopoulos KG. Induction of an antitumor immunological response by an intratumoral injection of dendritic cells pulsed with genetically engineered Semliki Forest virus to produce interleukin-18 combined with the systemic administration of interleukin-12. J Neurosurg. 2003;99:746–753. doi: 10.3171/jns.2003.99.4.0746. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]