Abstract

Knowledge is quite limited about the extent and social correlates of marital fertility decline for the United States in the early part of the nineteenth century. Manuscripts from the New York State census of 1865 indicate a very slow decline in marital fertility during the initial decades of the nineteenth century and more rapid decline as the Civil War approached. Little evidence of fertility control within marriage is found for the very oldest women in the sample, but analysis of parity progression ratios indicates that some control had emerged by the midpoint of the nineteenth century. Fertility decline was most evident in the urban, more economically developed areas, but our data also indicate that the limited availability of agricultural land may have affected the transition. While a marital fertility transition occurred in nineteenth-century New York, many couples in various geographic areas and social strata continued to have quite high levels of fertility, indicating difficulties that were probably faced in controlling reproduction.

The U.S. fertility transition of the early nineteenth century constitutes an important, although somewhat unique, part of the general European transition. By 1800, the white population of the United States apparently had one of the highest fertility rates in the world, certainly in Europe and North America (Sanderson 1979). During the nineteenth century, a long-term decline in U.S. fertility occurred, although it was by no means continuously sustained (Smith 1987; Tolnay, Graham, and Guest 1982). Early and rapid decline was especially characteristic of the New England and Middle Atlantic states, including New York. In contrast, most of the European continental countries (except for France) did not undergo noticeable declines in fertility until the late 1800s (Coale and Watkins 1986).

The great bulk of the evidence for the early U.S. fertility decline is based on child-woman ratios, determined by comparing the number of census-enumerated populations of children in the earliest years of life with the number of women in the reproductive years. However, these ratios suffer from a number of problems as measures of fertility, including a virtually complete lack of consideration of the role of mortality in reducing the numbers of children who were actually born and the inability to study the patterns only for married women.

The present paper utilizes individual and household-level data from the manuscripts of the 1865 New York State census to investigate patterns of fertility for women over age 45 in seven counties that represent the social and economic diversity of the state. Particularly useful are the data on children ever born (parity), collected for adult women as part of the regular enumeration in June 1865. This census seems to have been the first regular enumeration in human history to have asked such a question.

Two major research questions guide the analysis. First, did women in New York in the early 1800s participate in a marital fertility decline that was consciously controlled? An important frame of reference is the study by Hacker (2003), who argued that the national fertility transition, at least until 1840, was only weakly related to changes in marital fertility patterns. Second, were variations in marital fertility related more strongly to “traditional” indicators of economic development, such as urbanization and prosperity, as opposed to indicators of agricultural development, such as the availability of farmland? Research in the tradition of the theory of the demographic transition (Mason 1997) has focused on economic development as causing sustained fertility declines, whereas research by several economists on the U.S. fertility decline in the nineteenth century has stressed shortages of available farmland as a major factor (Easterlin, Alter, and Condran 1978; Schapiro 1982).

We make no claim that New York is necessarily representative of the United States. But besides being diverse in population composition and settlement patterns, the state of New York was one of the more populous parts of the country; in 1860, 12.3% of the U.S. population in states and territories lived in New York. In addition, New York had a relatively steep decline in child-woman ratios in the early nineteenth century (Guest 1990), making it a useful place to ascertain whether marital fertility followed the same general decline.

RESEARCH ON THE U.S. FERTILITY TRANSITION

Studies of U.S. fertility in the nineteenth century have argued generally that the steep declines in child-woman ratios indicated a similar marital fertility decline through conscious control of fertility. Coale and Zelnik (1963), in the most prominent example, used census data on ages of women and children to argue for relatively continuous declines in marital fertility among whites during the pre–Civil War period. Yasuba (1962) also believed that declining marital fertility was quite important. However, he concluded that “marital customs” were important in the U.S. decline (1962:108–25), even though he was limited by the availability of high-quality data on marriage. Localized studies of marital fertility decline during early U.S. history primarily focused on the Northeast, where the greatest declines in child-woman ratios were occurring. Wells (1971) documented marital fertility decline among religious Quakers during the eighteenth century. Swedlund and Temkin-Greener (1978) found a marital fertility decline in parts of the Connecticut River Valley in the eighteenth and first half of the nineteenth century.

More recent studies have taken a more agnostic position on the importance of marital fertility decline in the early decades of the nineteenth century. In one paper, Sanderson (1979) emphasized the possible role of increasing age at marriage in explaining the U.S. fertility decline in the first part of the nineteenth century. In a population that practiced little conscious fertility control, increases in the age at marriage would reduce the length of the fecund period and reduce the average size of families. Hacker (2003) agreed with this argument, but also presented a more detailed critique of the notion that marital fertility declined much before 1840. Relying on his data and other studies, he suggested two major factors that could have explained relatively constant marital fertility in the face of decreasing child-woman ratios. First, the proportion of ever-married women could have decreased in the early nineteenth century, removing women from the pool of those who could have children. Second, life expectancy may have decreased, leading over time to higher infant mortality that would not be included in the normal calculation of child-woman ratios.

These papers are important because they suggest that the United States may not have been an unusual case but part of a general pattern within the continental and overseas European world. Although stimulating, both the Sanderson and Hacker papers must be considered somewhat conjectural because they have no actual data on fertility within marriage and they rely on data on marriage patterns and mortality that are subject to problems of reliability. Reliable U.S. national data on marriage and mortality were not collected in the early 1800s; they only gradually became available in the late 1800s and early 1900s, generally for specific states that were located disproportionately in the more urban parts of the United States, especially the Northeast.

Recently, Main (2006) investigated some of Hacker’s ideas by studying genealogies of several thousand couples who lived in southern New England in the seventeenth through nineteenth centuries. Consistent with his argument, she found an increase in the age of marriage for wives (roughly a year in the first half of the nineteenth century) and a noteworthy decline in survivorship to adulthood for children during the first half of the nineteenth century. At the same time, Main found that the total marital fertility rate and completed family size underwent a continuous linear decline for women married during the first half of the nineteenth century. Of course, genealogies are not necessarily representative of the general population, since couples with high fertility will have a high probability of being represented.

Other relevant research (Haines and Hacker 2006) analyzed county-level U.S. child-woman ratios for whites during the pre–Civil War period of the nineteenth century. Due to the availability of census data, they were somewhat limited in the number of independent variables they considered. Counties with a surplus of men relative to women had high ratios in the early decades of the nineteenth century. This is important because women tend to marry at young ages when a surplus of men exists. For 1850 and 1860, Haines and Hacker analyzed over counties measures of the proportion of married women in their reproductive years. Their data clearly suggest that counties with high proportions of married women had high fertility. Overall, they found that county measures of urbanization were the strongest correlates of variation in child-woman ratios across counties, but they could not discern whether the ratios varied primarily due to marriage patterns or fertility within marriage.

Research on the social and economic causes of the U.S. fertility transition has traditionally been somewhat detached from studies of the European transition, although they involved roughly similar time points and cultural groups. A central scholarly question has been why the United States had a fertility transition when it was still predominantly rural. More traditional demographic transition theory (Mason 1997) has viewed rural conditions as generally incompatible with fertility decline for a variety of reasons, including the relatively high economic utility of children in agricultural production and the difficulty of farm women in developing distinctive work roles that would provide clear alternatives to childbearing.

A number of studies have explained how a U.S. decline in marital fertility could have occurred in a largely rural society by emphasizing the increasing shortages of available farmland. (Easterlin et al. 1978; Forster and Tucker 1972; Leet 1976; Schapiro 1982; Yasuba 1962). As the nineteenth century progressed, farmland became scarcer and more expensive, especially in the older, longer settled portions of the United States. Thus, families are hypothesized to have experienced cost increases that led to fertility restriction. These included difficulties in providing endowments (especially land) to children when family size was large, and also problems among the younger generation in marshalling resources to afford marriage. Resulting delayed marriage would have restricted the time in the reproductive life cycle for childbearing.

Other research on the nineteenth-century U.S. fertility transition has, in fact, tried to demonstrate how urbanization itself could have influenced fertility decline in a rural society. Sundstrom and David (1988) explained declining fertility by the increase in employment opportunities for farm children resulting from the growth of urban areas and nonagricultural industries. Children lost much of their value to parents because they were decreasingly willing to wait through adulthood to provide old-age support and inherit the farm.

Others have emphasized additional factors, such as the growth of educational systems and economic prosperity, as important to understanding the U.S. fertility transition. Thus, Carter, Ransom, and Sutch (2004) agreed with Sundstrom and David’s preceding argument but also noted that other life cycle factors, such as increasing rates of school attendance, made children economically costly for farm parents (also see Guest 1981; Guest and Tolnay 1983). They rejected the target-bequest model implied by the land availability hypothesis.

Several studies used data from the New York state census to investigate historical fertility patterns. Guest (1990) analyzed the aggregate-level correlates of New York fertility for counties in 1865, using data reported in the state census on parity distributions of native and foreign-born ever-married women, regardless of age. The value of homes, undoubtedly an indicator of economic prosperity, was a striking negative correlate of progression ratios for both native and foreign-born women. Value of homes was strongly intercorrelated with county urbanization level, but urbanization had little independent influence on fertility when home value was controlled statistically. A major limitation of Guest’s study was his inability to control directly for the age structure of the women. Fertility patterns among older women, for instance, might be different from those among younger women. Similar findings about the importance of home value were reported by Bash (1963), who analyzed variation in child-woman ratios for townships throughout the state in 1855, 1865, and 1875.

Other studies of nineteenth-century fertility in New York about the time of the Civil War have focused more on variations among individual couples in specific localities; these include Stern’s (1987) study of Erie County, Ryan’s (1981) of Oneida County, and Bash’s (1955) of Madison County. Both Stern and Ryan argued that growing prosperity was associated with a breakdown in traditional communal or patriarchal families. Opportunities to achieve economic prosperity led families to emphasize the acquisition of goods and material possessions rather than having children, and to concentrate their wealth on enhancing the occupational and educational opportunities of a limited number of children. Large numbers of children simply contributed little directly to the family economy, and the family’s material prosperity was primarily enhanced by the efforts of the husband in a market-oriented economy. Consistent with this argument, both Stern and Bash found that women with husbands in professional and managerial occupations tended to have low fertility. Bash also reported that residents of valuable homes had low fertility.

This paper does not deal directly with the literature that emphasizes “ideational” factors as causes of fertility decline. In the foremost example of this in regard to the United States, Leasure (1982) argued that states with strong representation of “individualistic” religious denominations had unusually low fertility in the nineteenth century. In analyses not directly reported in this paper, we found that various efforts to relate fertility patterns at the individual level to the strength of various individualistic denominations at the town level led to little support for this argument.

SAMPLE AND METHODS

The present analysis will proceed from a 5% systematic sample of the 1865 census manuscripts that were available through county and town clerks for seven counties: Allegany, Dutchess, Montgomery, Rensselaer, Steuben, Tompkins, and Warren. These particular counties were selected to represent various regions of the state with different dates of settlement and varied economies. Using child-woman ratios, we found that changes in fertility for these seven counties closely tracked those for the state outside New York City. Nevertheless, our choice of counties was constrained by the fact that the complete original set of 1865 schedules, including those for New York City, were apparently destroyed accidentally in a fire in Albany in 1911 (Lainhart 1992:85–88).

Some of the characteristics of the seven counties are shown in Table 1. So, for example, Allegany is located in the far western part of the state, while Warren is located by the Adirondack Mountains in the northeastern portion of the state. Both Allegany and Warren counties were relatively newly settled (by New York standards) and had a high proportion of adult males as farmers, rather low urbanization, low home values, and lower fractions of agricultural land improved. In contrast, the longer-settled counties of Dutchess, Montgomery, and Rensselaer in the southeastern part of the state had much higher levels of urbanization, lower proportions of farmers among the adult male population, higher home values, and high proportions of total agricultural land improved. On the whole, Tompkins and close-by Steuben, in the central Finger Lakes region, represent intermediate cases between the other two groups of counties, although parts of Steuben sit in the plateau of the Allegany Mountains.

Table 1.

Characteristics of Selected Counties, New York, 1865

| County | Total Population (1865) | % Urban | % Farmers | Average Home Value | % Illiterate Over Age 20 | % Agricultural Land Improved | Children Ever Born to Native, Ever-Married Women Aged 45+ | Children Ever Born to Native, Ever-Married Women Aged 30–44 | Children Aged 0–4 per 1,000 Women Aged 15–49 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Allegany | 40,285 | 7.62 | 62.08 | 0.42 | 1.00 | 54.25 | 6.1 | 3.4 | 451.1 |

| Dutchess | 65,192 | 50.17 | 27.72 | 1.52 | 3.30 | 78.31 | 5.4 | 3.9 | 420.4 |

| Montgomery | 31,447 | 69.51 | 32.08 | 1.11 | 3.10 | 83.02 | 5.9 | 3.6 | 438.3 |

| Rensselaer | 88,210 | 72.25 | 19.95 | 1.24 | 3.20 | 76.20 | 4.9 | 3.5 | 454.3 |

| Steuben | 66,192 | 27.66 | 50.94 | 0.55 | 3.30 | 55.44 | 6.3 | 3.5 | 483.4 |

| Tompkins | 30,696 | 35.09 | 42.84 | 0.74 | 1.30 | 74.36 | 5.2 | 3.0 | 355.4 |

| Warren | 21,128 | 36.08 | 50.08 | 0.44 | 3.60 | 41.62 | 6.5 | 4.3 | 543.8 |

| New York State | 3,831,777 | 62.99 | 27.92 | 1.85 | —a | 58.75 | —a | —a | 454.3 |

Notes: % urban uses the 1875 New York census definition; % farmers is farmers as a percentage of men aged 15–64; average home value is reported in thousands of dollars; % illiterate (cannot read and write), for native-born males over age 20, is estimated from a seven-county sample; and % agricultural land improved is (total improved agricultural land / total agricultural land) × 100.

Not available.

Source: New York State censuses, 1865 and 1875.

The sample contains 16,360 individuals in 3,325 households, representing 4.77% of the 343,150 individuals in these seven counties enumerated in the census of 1865. This is a bit less than the sampling fraction of 5% because of some missing and illegible manuscript pages and uninhabited dwellings that were encountered in the sampling procedure. The quality of enumeration in the census manuscripts appears to be very good. For instance, of the 923 women who were identified as over age 45, only 4.2% were missing data on children ever born.

Data on children ever born were reported on a column on the 1865 census manuscript page headed “Of how many children the parent?” The instructions to the enumerators stated the following: “This inquiry is to be made only of adult females and usually of wives or widows. It should, in all cases, include the number of living children the woman has borne, whether now living or dead and whether present or absent from the family. . .” (New York State 1867:lxvii; New York State 1877).

Concerns have been expressed (David and Sanderson 1987) about using unadjusted retrospective census data on children ever born to study historical changes in fertility across birth cohorts. In contrast, Shryock and Siegel (1971:512) reached more qualified conclusions on the basis of reviewing reports of children ever born by specific age cohorts over several U.S. censuses. They claimed that “[t]here is no definite evidence, however, that mortality is selective of the more fertile women.” Recently, Hurt, Ronsman, and Thomas (2006) reviewed previous studies that empirically investigated the relationship between parity and subsequent adult mortality for mothers. Patterns differed over the studies, but the authors concluded, “All effects seen were small and there were few statistically significant results” (2006:55).

A second potential problem is differential recall by age: older women are less likely to remember births than younger women. This potential problem would have the effect of understating the differences we have found by age cohort. Much of the concern about this issue is apparently based on observations of “nonnumerate” societies (Brass and Coale 1968:91), but the adult native-born population of New York in the nineteenth century was highly literate (although not necessarily highly educated), as Table 1 shows for the seven counties.

FERTILITY IN NEW YORK, 1865

Table 2 tabulates average parity by age of women for the total sample, for the foreign-born population, and for the rural and urban native populations. The women in the table are overwhelmingly white in racial identification. Parities are calculated for ever-married women (i.e., currently married, widowed, or divorced). Historical trends in fertility may be inferred by comparing age groups of women over age 45, since the biological ability to bear children is quite low after this age. The table shows both the chronological ages of the women as reported in the census and their (very) approximate years of birth as determined by subtracting their ages from 1865.

Table 2.

Average Parity by Age, Residence, Nativity, and Marital Status: Adult Women, Seven New York Counties, 1865

| Age | Birth Year | Total | Native | Urban Native | Rural Native | Foreign |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| All Women | ||||||

| 45–49 | 1816–1820 | 4.6 (383) | 4.2 (301) | 3.6 (113) | 4.6 (188) | 5.7 (82) |

| 50–54 | 1811–1815 | 4.9 (276) | 4.9 (217) | 3.8 (83) | 5.6 (134) | 4.9 (59) |

| 55–59 | 1806–1810 | 5.3 (229) | 5.2 (182) | 4.9 (61) | 5.4 (121) | 5.7 (47) |

| 60–64 | 1801–1805 | 5.7 (215) | 5.7 (171) | 4.8 (52) | 6.0 (119) | 5.8 (44) |

| 65–69 | 1796–1800 | 6.1 (108) | 6.2 (94) | 6.4 (35) | 6.1 (59) | 5.6 (14) |

| 70–74 | 1791–1795 | 6.1 (83) | 6.4 (67) | 5.8 (31) | 6.9 (36) | 4.8 (16) |

| 75–79 | 1786–1790 | 6.2 (63) | 6.7 (46) | 7.1 (13) | 6.5 (33) | 4.9 (17) |

| 80+ | pre-1786 | 6.9 (43) | 6.8 (36) | 7.2 (18) | 6.5 (18) | 7.0 (7) |

| Ever-Married Women | ||||||

| 45–49 | 1816–1820 | 4.9 (355) | 4.6 (277) | 4.1 (100) | 4.9 (177) | 6.0 (78) |

| 50–54 | 1811–1815 | 5.2 (258) | 5.3 (200) | 4.3 (74) | 5.9 (126) | 4.9 (58) |

| 55–59 | 1806–1810 | 5.7 (215) | 5.6 (168) | 5.5 (54) | 5.7 (114) | 5.7 (47) |

| 60–64 | 1801–1805 | 6.0 (202) | 6.1 (159) | 5.1 (49) | 6.5 (110) | 5.9 (43) |

| 65–69 | 1796–1800 | 6.6 (101) | 6.6 (89) | 6.8 (33) | 6.4 (56) | 6.5 (12) |

| 70–74 | 1791–1795 | 6.3 (80) | 6.6 (65) | 6.0 (30) | 7.1 (35) | 5.1 (15) |

| 75–79 | 1786–1790 | 6.5 (60) | 7.0 (44) | 7.1 (13) | 7.0 (31) | 5.2 (16) |

| 80+ | pre-1786 | 6.9 (43) | 6.8 (36) | 7.2 (18) | 6.5 (18) | 7.0 (7) |

Notes: The counties are: Allegany, Dutchess, Montgomery, Rensselaer, Steuben, Tompkins, and Warren. Figures in parentheses are numbers of women. Birth year is approximated by chronological age.

Source: Sample of census enumerators’ manuscripts.

As Table 2 indicates, the declines in average parity among ever-married native-born women were substantial, from 7 for women aged 75–79 (i.e., born 1786–1790 and in their peak childbearing years during approximately 1806–1825) down to 4.6 children per woman aged 45–49 (i.e., born 1816–1820 and in their peak childbearing years about 1836–1855). Unfortunately, the sample sizes at the oldest ages for these subsamples are relatively small and thus subject to larger sampling errors. Nevertheless, the New York declines in the early 1800s are much more impressive than Hacker (2003) suggested for the nation. He reported that the “white birth rate was approximately 5% lower in 1860 than it was at the beginning of the nineteenth century” (2003:607).

At the same time, we need to recognize that the clearest differences in parity, especially among native ever-married women, occurred for the youngest women. For instance, the difference in parity between the native ever-married women born between 1801 and 1805 and those born between 1816 and 1820 is 1.5 children (6.1 – 4.6), whereas the difference between the native ever-married women born between 1796 and 1800 and those born before 1786 is 0.2 children (6.8 – 6.6). All the cohorts of native ever-married women through those who were born between 1801 and 1805 had an average of at least six children. The data thus provide support for Hacker’s (2003) point that fertility decline within marriage was quite slow in the earliest decades of the nineteenth century.

Fertility declines typically occur more rapidly among urban than rural populations (Mason 1997). In this study, our definition of urban in 1865 is taken from the New York State census of 1875 (New York State 1877:Xv, 9–13). It includes (a) all areas designated as cities; (b) all towns adjacent to cities; and (c) towns containing villages with more than 1,000 people. The 1875 definition of urban, as applied to the 1865 returns, was considered superior to the definition that was used in the original reports of the 1865 census.

Table 2 indicates striking declines in fertility among both urban and rural women, indicating a transition in both populations. Nevertheless, the data suggest that the transition spread differentially from the urban to the rural areas. The urban-rural differences are quite small among the four oldest cohorts of ever-married native women, but among the four youngest cohorts, the urban women have somewhat lower fertility than the rural women. Even though the fertility decline was selective of the younger urban women, their fertility levels were still quite high in 1865 (at least by the standards of the twenty-first century United States).

The patterns for the foreign-born women, disproportionately drawn from Ireland, Germany, and the United Kingdom, show little regular change in the age groups over 45. There are some problems of interpretation because the sample sizes in various age groups are quite small. However, the data are consistent with the conclusion that the fertility transition had not begun yet in most of the European countries.

Some of the chronological trends in fertility that we have identified could be due to factors other than the frequency of reproduction within marriage. Changes in nuptiality might be especially important, with an increasingly late age at marriage reducing the fecund reproductive period for couples. Unfortunately, the 1865 census did not ask a question on age at marriage (but did ask about marital status), so we cannot calculate the duration of marriage for individuals or age cohorts. Generally, populations have a strong positive relationship between late marriage and the percentage never marrying. Among the native-born women in Table 2, the very oldest do have lower proportions never marrying than the younger. One consequence is that the differences in fertility among all women are slightly greater than among ever-married women. But the age cohort differences in fertility between the youngest and oldest ever-married women are so large that only (unlikely) dramatic shifts in age at marriage could explain them.

Hacker (2003) also suggested that a decline in the number of live children ever born among married women in the early nineteenth century could occur due to increased miscarriages, still births, and decreased fecundity due to bad health. The New York data cannot be directly adjusted for these factors, but again, these seem unlikely to account for the major differences we have found.

PARITY DISTRIBUTION

Since the women in the sample reported the specific number of children ever born, it is valuable to use parity progression ratios to inspect patterns of childbearing in New York in the early and mid-nineteenth century relative to other populations. The average number of births among a group of women may obscure interesting information about the distribution of family sizes. Parity progression ratios measure the probability of having an additional birth (n + 1) once one has achieved n births (Feeney and Feng 1993).

There should be a natural tendency in any population for the progression ratios to decline slightly with the parity number, partly because women at high parities are, on average, older than women at low parities, and thus have lower fecundity. But parity progression ratios should show little decline with parity in populations over age 45 that do not practice conscious birth control, primarily because couples make little effort to stop childbearing at any socially acceptable number before reaching the end of the fertile reproductive period. While high parity progression ratios are consistent with low fertility control, they do not indicate whether the children are desired. Nevertheless, survey studies in the last part of the twentieth century show a clear tendency for American women of high parity to report a high number of births that were not desired or occurred at the “wrong time” in the parents’ life cycle (Bumpass and Westoff 1970).

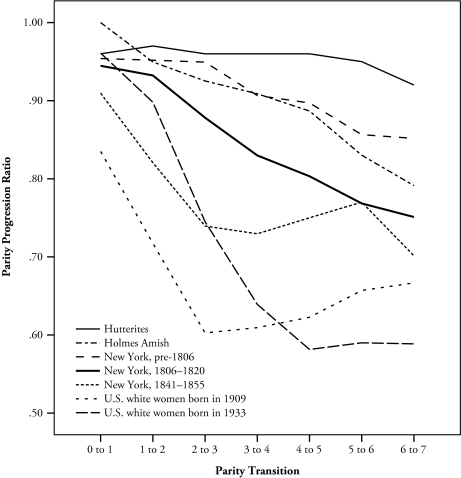

Figure 1 shows the pattern of parity progression ratios for two North American populations that are believed to exert only minimal control over their fertility. One set of ratios is reported by Eaton and Mayer (1953; Sheps 1965) for the well-known Hutterite population over the age of 45 in 1950. These women had a median number of 10.4 children, are believed to have exerted virtually no conscious control over their fertility, and have parity progression ratios that show only a mild decline with parity. The other set of ratios is based on data for Old Order Amish women over age 45 in 1964 in Holmes County, Ohio. As the authors Cross and McKusick noted (1970:100), “[d]elayed marriage is the only detectable means of family limitation.” We have arbitrarily set the progression ratio to the first birth as 1.0 because the data source does not permit exact calculation, although it is clear from the materials that the ratio is actually slightly lower. The Amish parity progression ratios are quite similar to the Hutterite pattern but show slightly more decline, a pattern that may be due primarily to the later age of marriage of women and to possibly poorer fecundity due to health, but may also indicate some very slight degree of conscious fertility control.

Figure 1.

Parity Progression Ratios for Historical Populations

Certainly, the oldest New York women should have parity progression ratios that are similar to the Hutterites and Amish, partly because fertility levels were so high. Moreover, adult men and women in the pre–Civil War period did not have access to the easy-to-use and effective contraceptive techniques that have become important in the past few decades.

One study (Brodie 1994:136–203) discussed the often fugitive information about control of reproduction in the nineteenth century. Abortion was available, but was not sanctioned positively. Condoms were available, but the materials of construction (such as leather sheaths) were not conducive to sexual pleasure; in addition, the use of condoms was often stigmatized because they were identified with “immoral” sexual behavior, such as prostitution (Brodie 1994:206–207; Tone 2001:48–49). For most couples, a high degree of sexual self-control was probably required to guarantee that women would bear not more than two or three children. Common means of reproductive control probably included abstinence, withdrawal, and douching.

Two sets of ratios are shown in Figure 1 for native ever-married women in the sample of the seven New York counties, for women aged 45–59 in 1865 and women over 60 in 1865. Women over 60 would have typically borne children at least 20 years earlier, before 1845. Although ratios were calculated for more detailed age groups, we present these two because the sample sizes became unacceptably small with more age-specific groups. The two sets of ratios in Figure 1 capture the major differences between the age cohorts.

The pattern for married women over 60 (born approximately before 1806) is strikingly similar to the Amish pattern, suggesting little (but perhaps some) conscious fertility control. The over-60 pattern has less overlap with the Hutterites, who almost certainly practiced virtually no conscious fertility control. Because age at marriage data for these older New York women are unavailable, we cannot assess the role of age at marriage in the progression ratios. Nevertheless, the singulate mean age of marriage (Hajnal 1953) among native-born New York women in the reproductive ages, according to the 1865 census data, was about 23.6, compared with a reported age of 22.6 for all wives among the Holmes County Amish (Cross and McKusick 1970).

In contrast, the pattern for New York women aged 45–59 (born approximately between 1806 and 1820) suggests the emergence of birth control. They diverge more significantly than the oldest New York women from the patterns of the low-control Hutterite and Amish populations. This divergence is small at the lower parities, indicating that almost all women were still bearing at least some children and that the “modern” family of fewer than 3 children was quite unusual. But the divergence is more evident at the highest parities, suggesting that significant proportions of New York women aged 45–59 in 1865 were targeting a smaller family size and trying to control their fertility.

Nevertheless, in this sample of New York women aged 45–59 in 1865, the probability of another birth was still greater than 75% at each of the reported parities, indicating little consensus on a specific family size target and implying (probably) low levels of conscious fertility control. In other words, these New York women were quite heterogeneous, compared with contemporary women, in the levels of reproduction. Although a significant number were making serious efforts to control their fertility, a significant number were also making few efforts in this direction. In addition, there was little evidence of a consensus “stopping point” for reproduction. Researchers (David and Sanderson 1987b; Ryder 1969) have noted the gradual emergence of a two- to three-child family norm among American women in the very late 1800s and the twentieth century, but no one previously has had the data to demonstrate the lack of a norm for somewhat earlier periods.

Although the data suggest only moderate evidence of stopping behavior among the younger native women in New York, their differences from the older women did lead to a clear divergence in the presence of very large families. Of the ever-married women over age 60 in 1865, some 51.4% reported having at least seven children; of the ever-married women aged 45–59, only 30.1% reported having this many children. In contrast, they differed only slightly in the presence of a very small family of 0 or 1 child (over age 60, 17.5%; ages 45–59, 14.5%).

Further evidence on the emergence of birth control and restricted family size is evident when we compare in Figure 1 the New York women aged 45–59 in 1865 with the 288 ever-married, native-born women aged 45–59 (living in the same seven counties) who appeared in the two public-use samples of the 1900 census (Graham 1980; Ruggles et al. 2004). In 1865, these women were unmarried children or young adult women (either unmarried or recently married).

While the pattern for the women aged 45–59 in 1900 (born approximately between 1841 and 1855) does not form a smooth curve (possibly due to the sample size), it has a peculiar shape that is echoed to some degree by later populations in the figure. In particular, parity progression ratios decline steeply at the lowest parities, but then tend to level out. This suggests that a significantly higher share of these New York women were effectively achieving replacement or below-replacement fertility by the late 1800s, but high proportions of other couples were still apparently making few efforts in this direction and continued to have a high probability of additional births at high parities. One cannot know whether the emergence of extremely small and moderate-sized families was due to changing family size desires; but it is noteworthy, as others have pointed out (Knodel and van de Walle 1979), that the late two decades of the 1800s were marked in European society by the active publicizing of birth control techniques, the development of the diaphragm, and improved manufacturing of condoms.

The emerging nature of family formation in the twentieth century is further indicated by Ryder’s (1969:102) estimates of parity progression ratios for U.S. white women who were born in 1909 and 1933, years that reflect, respectively, the low fertility that occurred during the great Depression and the high fertility that occurred in the post–World War II baby boom. In form, both these curves are similar to that identified for New York native-born women in the 1900 public-use samples. The curves decline steeply at the lowest parities, but then level off or even increase at the higher parities. Again, the data suggest that American women in these cohorts were a combination of active controllers and passive controllers. The curve for the 1909 Ryder cohort is very similar in shape to the curve for the older New York native-born women in the 1900 public-use samples, but at slightly lower levels of fertility. Consistent with our knowledge of the baby boom, the 1933 birth cohort actually has higher probabilities of another birth at the low parities than the 1909 birth cohort, but the progression probabilities continue to decline at the higher parities. In other words, as others have pointed out, much of the baby boom was due to a decline in the proportion of 0 and 1 parity women. Very large families continued to decline in importance.

VARIATIONS IN FERTILITY

Of particular interest is the question of whether New York women responded in their fertility behavior to different aspects of the social structural situation in which they lived. As previously suggested, the causal importance of the transition from an agricultural economy to an urban, industrial economy deserves attention. An associated idea holds that the development of materialism and economic prosperity led certain groups, especially in high socioeconomic positions, to restrict their fertility to emphasize opportunities for themselves or their children. Alternatively, early explanations (Easterlin et al. 1978; Schapiro 1982) of the U.S. fertility transition emphasized the importance of the agricultural sector in understanding the decline of fertility, placing particular emphasis on the declining availability of inexpensive agricultural land.

To test for these possible explanations of fertility behavior, we focus on native-born wives between the ages of 45 and 59 in the 1865 census manuscripts, who report themselves as married only once, are listed along with their spouse, and reside in the first-listed family in the dwelling. We exclude women in the cities of Poughkeepsie and Troy because they were so urban that the agricultural variables have no meaning. Previous analysis demonstrated that this age group of women, in comparison with the women who were even older, showed some clear evidence of active fertility control, albeit limited. In addition, they completed childbearing more recently than the older group of women and, therefore, are more likely to be living in the environments where they bore their children.

Our analysis proceeds by specifying three types of individual/household effects that might affect fertility behavior. Table 3 shows how these variables are related to fertility in models that include all the predictors.

Table 3.

Regressions With Children Ever Born as the Dependent Variable: Seven New York Counties, 1865

| Independent Variables | Mean | SD | Pearson r Coefficient | Partial Beta Coefficient | Unstandardized Beta Coefficient |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Family Level | |||||

| Constant | 2.984 | ||||

| Wife’s age | 50.7 | 4.3 | .098* | 0.095 | 0.067* |

| Husband’s occupation | |||||

| White collar | 0.092 | 0.289 | −.089* | −0.084 | −0.877 |

| Craftsman/foreman | 0.130 | 0.336 | .029 | −0.010 | −0.092 |

| Other blue collar | 0.065 | 0.247 | .029 | −0.012 | −0.149 |

| Agricultural | 0.617 | 0.487 | −.015 | −0.101 | −0.625 |

| Other responses | 0.096 | 0.295 | —a | —a | —a |

| Value of dwelling ($00’s) | |||||

| $0–$499 | 0.376 | 0.485 | .126** | −0.011 | −0.066 |

| $500–$999 | 0.246 | 0.431 | .007 | −0.071 | −0.494 |

| $1,000–$1,499 | 0.101 | 0.301 | −.088* | −0.123 | −1.227* |

| More than $1,500 | 0.148 | 0.355 | −.139** | −0.155 | −1.313* |

| No value reported | 0.130 | 0.336 | —a | —a | —a |

| Town Level | |||||

| % improved agricultural land | 0.679 | 0.171 | −.146** | −0.140 | −2.480* |

| Average value of farm acres | 43.7 | 28.1 | −.081† | 0.051 | 0.005 |

| Log of dwelling value | 6.40 | 0.62 | −.098* | 0.043 | 0.211 |

| Urban residence | 0.253 | 0.453 | −.111** | −0.091 | −0.634 |

| Mean, Dependent Variable | 5.188 | ||||

| SD, Dependent Variable | 3.015 | ||||

| N | 447 | ||||

| Adjusted R2 | 0.070 | ||||

| F Ratio | 2.52** | ||||

Not included.

p < .10;

p < .05;

p < .01

First, a basic demographic effect involves the age of the women, which will have obvious, important effects on fertility. A second set of effects emphasizes the possible importance of socioeconomic position of the family as measured by the reported value of the dwelling and the occupational position of the husband. Value of dwellings is based on four dummy variable categories that represent the diversity of responses from low to high; a fifth category is included for cases in which the value was not reported (13.0% of the sample). Husband’s occupation is divided into five categories, using the occupational coding scheme of the 1950 U.S. census. White collar includes professional, managerial, clerical, and sales; skilled blue collar includes skilled manual workers (craftsmen and foremen). The two other occupational categories are other blue-collar workers (operatives, service and household, and laborer) and agricultural (farming). To these categories, we add an “other” category (9.6% of the sample) that includes unclassifiable and non-occupational responses (e.g., student, landlord, retired, gentleman).

A third set of effects considers the roles of community economic development and agricultural systems in explaining fertility variation. In the 1865 state census, a wealth of data were reported for the over 900 towns of the state, which are geographic parts of counties, containing at most a few thousand residents. While many township political, social, and geographical characteristics are reported, we focus on four characteristics that seem to have had a high a priori validity in relationship to previous theorizing and research. One measure of economic development, broadly defined, is the natural logarithm of the average dwelling value. Another useful variable is urbanization level. We measure it as the percentage of the 1865 population that lives in urban places, according to the definition of urban in 1875 as applied to the 1865 population. Two measures of agricultural character are used: the proportion of all farmland that is “improved” and the average value in dollars of an acre of farmland.

Unfortunately, our analysis does not include specific measures of educational attainment for the women, their husbands, or their communities. The census manuscripts reported literacy, but the native population was overwhelmingly able to read and write in 1865. Data on educational attainment and the nature of school systems were available in 1865 for counties but not for towns.

In Table 3, the first two columns indicate the means and standard deviations of the variables, with the values for the dummy variables stated as proportions of the sample. The third column indicates the zero-order correlation coefficient or the standardized regression effect of the variable on fertility when no statistical controls are introduced for other predictive variables. The fourth column shows the standardized partial regression effect (beta) of the variable when all the other independent variables are statistically controlled. The value in the fourth column will be lower than that in the third column to the degree that a variable’s intercorrelation with other variables helps explain its relationship with fertility. The last column presents the unstandardized partial regression effect of the variable, or how a one-unit change raises or lowers the number of predicted children born. In the case of dummy variables, the unstandardized regression coefficients indicate the level of fertility for persons with those characteristics relative to the omitted categories, which are persons with no reports in the cases of housing value and occupation.

Several of the zero-order correlation coefficients are statistically significant at the .05 level, using a one-tailed F test, although the coefficients are low by most conventional absolute standards. The low coefficients might be expected, given that, as Figure 1 shows, only a low degree of fertility control had emerged among the youngest native ever-married women.

Of particular interest is the fact that the improved land variable is the strongest correlate of individual-level variation in children ever born. In addition, slightly lower negative (but statistically significant at the .05 level) correlations are found for the average community value of dwelling and location in an urban community.

The correlations also indicate that, as anticipated, older women have more children ever born than younger women. In addition, household-level occupational and dwelling value indicators are statistically significant. Wives of white-collar workers have lower fertility than wives of the craftsmen/foremen and other blue-collar workers. Note, nevertheless, the low fertility of agricultural workers. Wives who live in the two most valuable categories of dwellings have lower fertility than those who live in dwellings where the value is low or not reported.

When the predictor variables are included in a multiple regression equation, only one community-level variable (the proportion of improved agricultural land) remains statistically significant at the .05 level. Marital fertility is lower in communities with high proportions of improved land, but the monetary value of agricultural land has essentially no relationship to fertility. In addition, both the community-level value of dwelling and urbanization are no longer statistically significant predictors. However, the negative partial effects of living in an urban community are noteworthy. The unstandardized partial regression coefficient indicates that, even with controls for other variables, urban women averaged 0.63 fewer children than rural women.

The partial regression coefficients for the family-level occupational and dwelling value variables are generally consistent with the thesis that the economically successful had the lowest fertility. Tests of statistical significance must be interpreted carefully because all the dummy variables are compared with the omitted category, which represents households with no reported values. While none of the occupational dummy variables are statistically significant at the .05 level, wives of white-collar workers have the lowest fertility levels. Women who live in the cheapest dwellings have higher fertility levels than women who live in more valuable sites. Thus, women in the least valuable dwellings are predicted to have 1.247 more children than those in the most valuable homes (−0.066 – (−1.313)).

The results provide a mixed message about the relative importance of the agricultural system as opposed to “modern” economic development in reducing fertility. Certainly, the documented effect in Table 3 of the improved land variable deserves recognition. Previous research (Guest 1990) on 1865 aggregate-level variations in children ever born across New York counties downplayed the role of variations in the availability of farmland, except through the mechanism of delayed marriage. Unfortunately, the data in this paper do not permit us to make very reasonable estimates for these older women of their ages at marriage. We also should point out that a high proportion of the towns with very low proportions of improved land were found in Steuben County (partially in the Allegheny Mountains) and Warren County (located in the Adirondacks). Many of these towns were geographically isolated and not closely linked to the most “modern” parts of New York at the time.

The findings of previous research about the role of community-level dwelling value in understanding variations in fertility are only marginally supported in this research. The dwelling values of the individual women relate to their fertility in the way that we anticipated. While community-level dwelling value is clearly related in our sample to variations in marital fertility, however, its effect is quite small when we control for other variables, especially the degree of improved agricultural land. This result may partially reflect a statistical artifact. The zero-order correlations of community-level dwelling value and improved land with individual fertility variations are similar, and the two community variables are clearly related to each other. In such a situation, according to some analysts (e.g., Gordon 1968), it may be difficult to pick statistically the better predictor relative to the other one.

DISCUSSION

Examination of these microdemographic data from the 1865 census of the state of New York confirms significant fertility decline within marriage in early nineteenth-century America, independent of the same trends that are suggested by census child-woman ratios. These results are more general geographically than those provided by Bash (1955). Because New York had close cultural-social-economic ties with the New England states, this New York paper arguably captures a real trend in marital fertility that occurred in a large segment of the U.S. population living in the most established and economically developed parts of the country.

Although our data are primarily limited to retrospective reports, we find that New York–native married women in the reproductive ages in the first part of the nineteenth century had high probabilities (over 60%) of bearing at least seven children, whereas only about 20% of the women completing childbearing at the time of the Civil War had as many as seven children. These estimates for cohorts may be affected by various selective factors—survivorship of mothers by parity, the proportions of still births among pregnancy, fecundity of mothers, recall of older women, and changes in marriage patterns—but the differences are too great to attribute primarily to these factors.

Yet, our results are also compatible with Hacker’s (2003) argument that little significant marital fertility decline occurred before 1840. Changes in marital fertility among the oldest age groups of women bearing children in the initial decades of the nineteenth century were very small. In addition, clear evidence of fertility control occurred only for women born (approximately) after 1806. This means that many of these women would have, in fact, entered the “busy” stage of their reproductive lifetimes during the 1830s and 1840s. Unfortunately, we cannot directly compare our results with his “timing” patterns because the age cohorts in our sample could have had their births over a wide range of years in the early 1800s.

The data on the younger cohorts provide evidence in support of both major positions on how social structure affected the U.S. decline in marital fertility. The strongest single correlate of marital fertility in the multivariate analysis was the proportion of improved land, but the price of purchasing an acre of farmland had virtually no relationship to fertility behavior. Especially at the household level, indicators of occupational status and home wealth are useful for distinguishing high and low fertility patterns, but admittedly, the differences are not very large. In addition, areal differences by levels of urbanization and housing value are unimpressive. For instance, the multivariate analysis showed that women in urban areas averaged only 0.63 fewer children than women in rural areas.

The nineteenth-century New York transition appears to be far different from the spectacular declines reported for countries such as Japan and Taiwan in the post–World War II period (Feeney 1991; Feeney and Feng 1993). In our New York sample, the development of a “modern” fertility pattern occurred quite gradually and involved only limited segments of the reproductive women in short periods of time. But in countries such as Japan and Taiwan, the decline (once begun) occurred dramatically and quickly. Cohorts of women significantly altered their fertility behavior within one or two decades so that families of several children virtually disappeared and few women were having more than three or four children. There is extensive debate on why such countries experienced such rapid changes; it appears, however, that the availability of effective, accessible contraception, such as the intrauterine device (IUD), was quite important, almost certainly in conjunction with the general process of national social and economic development.

The existence of slow marital fertility decline within the context of New York’s rapid economic and commercial development has some implications for the well-known debate about whether fertility transitions in the nineteenth century reflected adjustment to social structural conditions or the diffusion of information on how to control births (Knodel and van de Walle 1979). Our data suggest that social structure was important, but there was a partial or incomplete response by many couples in the areas that should have been conducive to fertility decline, perhaps because the means to achieve fertility control were not very effective.

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to thank the research assistants who did the original data entry in 1975 and 1976.

Footnotes

The original data collection from the New York State census of 1865 was funded by the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (Grant RO1-HD07599).

REFERENCES

- Bash WH. “Differential Fertility in Madison County, New York, 1865”. Milbank Memorial Fund Quarterly. 1955;33:161–86. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bash WH. “Changing Birth Rates in Developing America: New York State, 1840–1875”. Milbank Memorial Fund Quarterly. 1963;41:161–82. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brass W, Coale AJ. “Methods of Analysis and Estimation.”. In: Brass W, editor. The Demography of Tropical Africa. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press; 1968. pp. 88–150. [Google Scholar]

- Brodie JF. Contraception and Abortion in 19th-Century America. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Bumpass L, Westoff CF. “Unwanted Births and U.S. Population Growth”. Family Planning Perspectives. 1970;2:9–11. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carter SM, Ransom RL, Sutch R. “Family Matters: The Life-Cycle Transition and the Antebellum American Fertility Decline.”. In: Guinnane TW, Sundstrom W, Whatley W, editors. History Matters: Essays on Economic Growth, Technology, and Demographic Change. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press; 2004. pp. 271–327. [Google Scholar]

- Coale AJ, Watkins SC. The Decline of Fertility in Europe. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press; 1986. [Google Scholar]

- Coale AJ, Zelnik M. New Estimates of Fertility and Population in the United States; A Study of Annual White Births From 1855 to 1960 and of Completeness of Enumeration in the Censuses From 1880 to 1960. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press; 1963. [Google Scholar]

- Cross HE, McKusick VA. “Amish Demography”. Social Biology. 1970;17:83–101. doi: 10.1080/19485565.1970.9987850. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- David PA, Sanderson WC. “The Emergence of a Two-Child Norm Among American Birth-Controllers”. Population and Development Review. 1987;13:1–41. [Google Scholar]

- Easterlin RS, Alter G, Condran G. “Farms and Farm Families in Old and New Areas: The Northern States in 1860.”. In: Hareven TK, Vinovskis M, editors. Family and Population in Nineteenth-Century America. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press; 1978. pp. 22–84. [Google Scholar]

- Eaton JW, Mayer AJ. “The Social Biology of Very High Fertility Among the Hutterites: The Demography of a Unique Population”. Human Biology. 1953;25:205–64. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feeney G. “Fertility Decline in Taiwan: A Study Using Parity Progression Ratios”. Demography. 1991;28:467–79. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feeney G, Feng W. “Parity Progression and Birth Intervals in China: The Influence of Policy in Hastening Fertility Decline”. Population and Development Review. 1993;19:61–101. [Google Scholar]

- Forster C, Tucker GSL. Economic Opportunity and White American Fertility Ratios: 1800–1860. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press; 1972. [Google Scholar]

- Gordon RA. “Issues in Multiple Regression”. American Journal of Sociology. 1968;73:592–616. [Google Scholar]

- Graham SN. 1900 Public Use Sample: User’s Handbook. Seattle, WA: Center for Studies in Demography and Ecology; 1980. [Google Scholar]

- Guest AM. “Social Structure and U.S. Inter-State Fertility Differentials in 1900”. Demography. 1981;18:465–86. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guest AM. “What Can We Learn About Fertility Transitions from the New York State Census of 1865?”. Journal of Family History. 1990;15:49–69. doi: 10.1177/036319909001500103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guest AM, Tolnay S. “Children’s Roles and Fertility: Late Nineteenth-Century United States”. Social Science History. 1983;7:355–380. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hacker JD. “Rethinking the ‘Early’ Decline of Marital Fertility in the United States”. Demography. 2003;40:605–20. doi: 10.1353/dem.2003.0035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haines MR, Hacker D.2006“The Puzzle of the Antebellum Fertility Decline in the United States: New Evidence and Reconsideration” Working Paper 12571 National Bureau of Economic Research, Cambridge, MA.

- Hajnal J. “Age at Marriage and Proportions Marrying”. Population Studies. 1953;7:111–36. doi: 10.1080/00324728.1971.10405799. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hurt LS, Ronsman C, Thomas SL. The Effect of Number of Births on Women’s Mortality: Systematic Review of Evidence for Women Who Have Completed Their Childbearing.”. Population Studies. 2006;60:55–71. doi: 10.1080/00324720500436011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knodel J, van de Walle E. “Lessons From the Past: Policy Implications of Historical Fertility Studies”. Population and Development Review. 1979;5:217–45. [Google Scholar]

- Lainhart AS. State Census Records. Baltimore, MD: The Genealogical Publishing Co.; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Leasure JW. “La Baisse de la Fecondite aux Etats-Unis de 1800 a 1860” [The decline of fertility in the United States from 1800 to 1860] Population. 1982;37:607–22. [Google Scholar]

- Leet DR. “The Determinants of the Fertility Transition in Antebellum Ohio”. The Journal of Economic History. 1976;36:359–78. [Google Scholar]

- Main GL. “Rocking the Cradle: Downsizing the New England Family”. Journal of Interdisciplinary History. 2006;37:35–58. [Google Scholar]

- Mason KO. “Explaining Fertility Transitions”. Demography. 1997;34:443–54. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- New York State. Census of the State of New York for 1875. Albany: Weed, Parsons and Company; 1877. [Google Scholar]

- New York State. Census of the State of New York for 1865. Albany: Charles van Berthuysen & Sons; 1867. [Google Scholar]

- Ruggles S, Sobek M, Alexander T, Fitch CA, Goeken R, Hall PK, King M, Ronnander C. Integrated Public Use Microdata Series: Version 3.0 [Machine-readable database] Minneapolis, MN: Minnesota Population Center; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Ryan MP. Cradle of the Middle Class: The Family in Oneida County, New York, 1790–1865. New York: Cambridge University Press; 1981. [Google Scholar]

- Ryder NB. “The Emergence of a Modern Fertility Pattern: United States, 1917–66”. In: Behrman SS, Corsa L, Freedman R, editors. Fertility and Family Planning: A World View. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press; 1969. pp. 99–123. [Google Scholar]

- Sanderson WC. “Quantitative Aspects of Marriage, Fertility and Family Limitation in Nineteenth Century America: Another Application of the Coale Specification”. Demography. 1979;16:339–58. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schapiro MO. “Land Availability and Fertility in the United States, 1760–1870”. Journal of Economic History. 1982;42:577–600. doi: 10.1017/s0022050700027960. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sheps M. “An Analysis of Reproductive Pattern in an American Isolate”. Population Studies. 1965;19:65–80. [Google Scholar]

- Shryock H, Siegel J. The Methods and Materials of Demography. Washington, DC: U.S. Government Printing Office; 1971. [Google Scholar]

- Smith DS. “‘Early’ Fertility Decline in America: A Problem in Family History”. Journal of Family History. 1987;12:73–84. doi: 10.1177/036319908701200105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stern MJ. Society and Family Strategy: Erie County. New York, 1850–1920. Albany, NY: SUNY Press; 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Sundstrom WA, David PA. “Old-Age Security Motives, Labor Markets, and Farm Family Fertility in Antebellum America”. Explorations in Economic History. 1988;25:164–97. [Google Scholar]

- Swedlund AC, Temkin-Greener H. “Fertility Transition in the Connecticut Valley, 1740–1850.”. Population Studies. 1978;32:27–41. doi: 10.1080/00324728.1978.10412790. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tolnay SE, Graham SN, Guest AM. “Own-Child Estimates of U.S. White Fertility, 1886–99”. Historical Methods. 1982;15:127–38. doi: 10.1080/01615440.1982.10594087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tone A. Devices and Desires: A History of Contraception in America. New York: Hill and Wang; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Wells RV. “Family Size and Fertility Control in Eighteenth-Century America: A Study of Quaker Families”. Population Studies. 1971;46:85–102. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yasuba Y. Birth Rates of the White Population of the United States. 1800–1860: An Economic Analysis. Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins University Press; 1962. [Google Scholar]