Abstract

Ca2+ is important for plant growth and development as a nutrient and a second messenger. However, the molecular nature and roles of Ca2+-permeable channels or transporters involved in Ca2+ uptake in roots are largely unknown. We recently identified a candidate for the Ca2+-permeable mechanosensitive channel in Arabidopsis (Arabidopsis thaliana), named MCA1. Here, we investigated the only paralog of MCA1 in Arabidopsis, MCA2. cDNA of MCA2 complemented a Ca2+ uptake deficiency in yeast cells lacking a Ca2+ channel composed of Mid1 and Cch1. Reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction analysis indicated that MCA2 was expressed in leaves, flowers, roots, siliques, and stems, and histochemical observation showed that an MCA2 promoter::GUS fusion reporter gene was universally expressed in 10-d-old seedlings with some exceptions: it was relatively highly expressed in vascular tissues and undetectable in the cap and the elongation zone of the primary root. mca2-null plants were normal in growth and morphology. In addition, the primary root of mca2-null seedlings was able to normally sense the hardness of agar medium, unlike that of mca1-null or mca1-null mca2-null seedlings, as revealed by the two-phase agar method. Ca2+ uptake activity was lower in the roots of mca2-null plants than those of wild-type plants. Finally, growth of mca1-null mca2-null plants was more retarded at a high concentration of Mg2+ added to medium compared with that of mca1-null and mca2-null single mutants and wild-type plants. These results suggest that the MCA2 protein has a distinct role in Ca2+ uptake in roots and an overlapping role with MCA1 in plant growth.

Calcium ion (Ca2+) is an essential element in plants, as in animals. In plants, Ca2+ is required for the formation of the cell wall as a determinant of structural rigidity (Jones and Lunt, 1967) and for the regulation of intracellular physiological events as a second messenger of extracellular stimuli, including chemical, physical, and mechanical stimuli (Fasano et al., 2002; Sanders et al., 2002; Braam, 2004). Thus, this ion is a crucial modulator of plant growth and development. In response to those stimuli, Ca2+ moves to the cytoplasm through Ca2+-permeable ion channels or transporters located in the plasma membrane or organellar membranes. Recent electrophysiological and bioinformatic analyses have found that there are several types of Ca2+-permeable ion channels in plants, including depolarization-gated, hyperpolarization-gated, ligand-gated, and mechanosensitive channels, although the structural entity and physiological functions of most are still obscure (Véry and Sentenac, 2002; White et al., 2002; Dutta and Robinson, 2004; Qi et al., 2004; Telewski, 2006).

Our recent study has identified a plasma membrane protein (named MCA1; locus name, At4g35920) involved in Ca2+ uptake in Arabidopsis (Arabidopsis thaliana; Nakagawa et al., 2007). Overexpression of MCA1 from a strong promoter increases Ca2+ uptake in roots and also enhances a rise in the cytoplasmic free Ca2+ concentration upon hypoosmotic shock. The primary root of mca1-null seedlings is unable to enter the lower, harder agar medium from the upper, softer one, suggesting that the mca1-null root cannot sense and/or respond to the hardness of the agar. In addition, heterologous expression of MCA1 markedly increases Ca2+ uptake in a yeast mutant lacking the high-affinity Ca2+ influx system composed of Mid1 and Cch1. Therefore, MCA1 is a potential component of the Ca2+-permeable mechanosensitive channel in Arabidopsis.

MCA2 (locus name, At2g17780) is the only paralog of MCA1 found in the Arabidopsis genome (Nakagawa et al., 2007). MCA2 is 72.7% identical and 89.4% similar to MCA1 in amino acid sequence. The two proteins share the same structural features: The N-terminal half has a region similar to the putative regulatory region of many rice (Oryza sativa) putative protein kinases, an EF-hand-like motif, and a coiled-coil motif. The C-terminal half possesses two to four putative transmembrane segments and a Cys-rich domain of unknown function, called the PLAC8 motif (Galaviz-Hernandez et al., 2003).

In this study, we made an mca2-null single mutant and an mca1-null mca2-null double mutant to investigate fundamental functions of MCA1 and MCA2 in terms of Ca2+ uptake, plant growth, and mechanosensing. We demonstrate that both mutants are defective in Ca2+ uptake from the roots, and the mca1-null mca2-null double mutant has a slow growth phenotype compared with the wild type. In addition, the growth of the double mutant is more sensitive to excess Mg2+. We also show that the primary root of the mca2-null mutant appears to be normal in sensing and/or responding to the hardness of agar medium. Since this phenotype contrasts with the phenotype of the mca1-null mutant previously reported (Nakagawa et al., 2007), we discuss possible similarities and differences in function between MCA1 and MCA2.

RESULTS

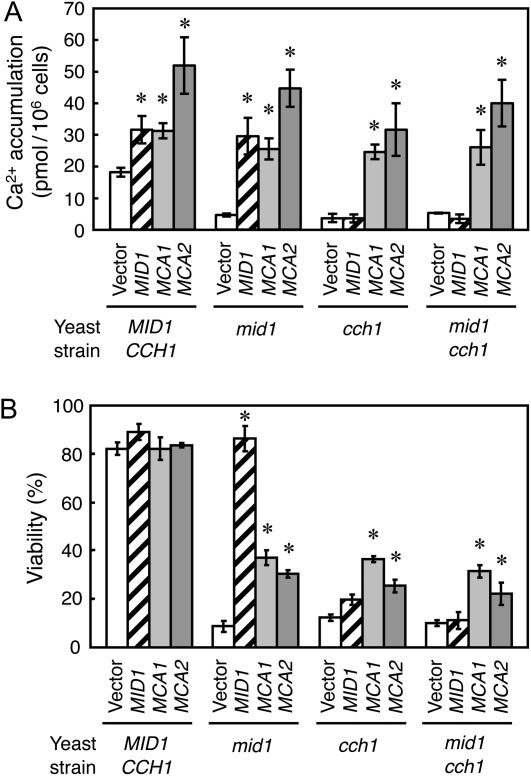

MCA2 Complements the Yeast mid1 Mutation

To test the functional similarity of MCA2 to MCA1, we employed functional complementation of the Saccharomyces cerevisiae mid1 mutant, which is defective in a putative Ca2+-permeable mechanosensitive channel component and thus dies upon exposure to mating pheromone (Iida et al., 1994; Kanzaki et al., 1999). The mid1 mutant was transformed with the yeast expression plasmid YEpTDHXho-MCA2 containing MCA2 cDNA placed under the control of the yeast TDH3 promoter. Quantitative assays showed that MCA2 complemented the low Ca2+ uptake activity of mid1 cells (Fig. 1A) and partially rescued the mid1 cells from mating pheromone-induced death (Fig. 1B).

Figure 1.

Function of MCA2 in yeast cells. A, MCA2 has the ability to increase Ca2+ accumulation even in the mid1 cch1 double mutant. MCA1 or MCA2 cDNA on a multicopy plasmid was expressed under the control of the TDH3 promoter in each yeast mutant (mid1, cch1, or mid1 cch1) as well as the parental strain (wild type). The yeast MID1 gene with its own promoter was also expressed from a multicopy plasmid, YEpMID1 (Nakagawa et al., 2007). Data are the mean ± sd for three independent experiments. *P < 0.05 versus the vector in each mutant. Note that the data for vector, MID1, and MCA1 are from our previous article (Nakagawa et al., 2007). B, MCA2 has the ability to increase viability after exposure to α -factor even in the mid1 cch1 double mutant. The yeast cells used in this experiment are the same as in A. Data are the mean ± sd for three independent experiments. *P < 0.05 versus the vector (control) in each mutant.

In S. cerevisiae, Mid1 coworks with Cch1 to function as the sole high-affinity Ca2+ influx system (Muller et al., 2001); therefore, MID1 cannot complement the cch1 single and the mid1 cch1 double mutants (Iida et al., 2004). By contrast, MCA1 can do so (Nakagawa et al., 2007). Figure 1, A and B, shows that MCA2 was also capable of complementing the low Ca2+ uptake activity and low viability phenotypes of the cch1 single and the mid1 cch1 double mutants. These results indicate that MCA2 functions as a Ca2+ influx system in yeast cells, independently of Mid1 and Cch1, just like MCA1.

Overlapping and Distinct Expression of MCA1 and MCA2

A reverse transcription PCR (RT-PCR) analysis showed MCA2 to be expressed in all the organs examined, including leaves, flowers, roots, siliques, and stems (Fig. 2A). The spatial pattern of MCA2 expression was examined with an MCA2 promoter::GUS fusion reporter gene construct (MCA2p::GUS). Figure 2B, i–k, shows that MCA2p::GUS was universally expressed in 10-d-old seedlings, with relatively high levels in vascular tissues and no expression in the root cap, promeristem, and adjacent elongation zone of the primary root. MCA2p::GUS was also expressed in mesophyll cells and vascular tissues of cotyledons and leaves. In addition, it was expressed at the center of rosettes in a region corresponding to the shoot apical meristem (Fig. 2B, l). A cross section of the primary root indicated that MCA2p::GUS was expressed in the stele and endodermis, but not in the cortex and epidermis (Fig. 2B, m). We noticed that the level of MCA2p::GUS expression was gradually lowered in cotyledons as they aged (Fig. 2B, i). In 22-d-old plants, MCA2p::GUS was expressed in leaves and roughly the upper half of the inflorescence, but not in petioles of rosette leaves (Fig. 2B, n–p). It was also expressed at the center of rosettes and the inflorescence.

Figure 2.

Expression of MCA2. A, RT-PCR of the MCA2 transcript. Total RNA was isolated from leaves, flowers, roots, siliques, and stems of wild-type Arabidopsis plants (5 to 6 weeks old) and subjected to RT-PCR. β -Tubulin mRNA was used for an internal control. B, Spatial patterns of MCA1 and MCA2 transcription as revealed by GUS staining. Ten-day-old (a–e and i–m) and 22-d-old (f–h and n–p) MCA1p::GUS and MCA2p::GUS plants are shown. a and i, A whole plant (an arrow indicates the extreme end of the primary root); b and j, a leaf (not a cotyledon); c and k, the tip of a primary root; d and l, a region corresponding to the shoot apical meristem; e and m, a cross section of a primary root, showing GUS activity in the stele and endodermis; f and n, an upper view of a 22-d-old plant; g and o, magnification of the base of the inflorescence shown in f and n, respectively; h and p, a side view of a 22-d-old plant. Note that two photographs were joined to make h. C, GFP fluorescence images of MCA2-GFP expressed in root cells. The top row represents intact roots of 6-d-old seedlings and the bottom row those treated for at least 10 min with 0.8 m mannitol to induce plasmolysis. The membrane marker proteins used are as follows: plasma membrane, a GFP fusion to the plasma membrane channel protein PIP2A expressed in line Q8; endoplasmic reticulum (ER) membrane, a GFP fusion to an endoplasmic reticulum membrane protein expressed in line Q4; vacuolar membrane, a GFP fusion to the vacuolar membrane channel protein δ -TIP expressed in line Q5 (Cutler et al., 2000); and cytoplasmic GFP.

MCA1p::GUS was found to be expressed with overlapping and distinct spatial expression patterns compared with MCA2p::GUS. Like MCA2p::GUS, in 10-d-old seedlings, MCA1p::GUS was expressed in vascular tissues of cotyledons, leaves, and the primary root and at the center of rosettes in a region corresponding to the shoot apical meristem (Fig. 2B, a–d). It was also expressed in the stele and endodermis, but not in the cortex and epidermis (Fig. 2B, e). In 22-d-old plants, MCA1p::GUS was expressed weakly in vascular tissues of leaves and at the center of rosettes and the inflorescence (Fig. 2B, f and g). No expression of both MCA1p::GUS and MCA2p::GUS was detected in the root hair (Fig. 2B, c and k).

Unlike MCA2p::GUS, MCA1p::GUS was expressed in the promeristem and adjacent elongation zone of the primary root (Fig. 2B, c). Notably, it was not expressed in the root cap, including the columella and peripheral cap. In addition, no expression of MCA1p::GUS was detected in mesophyll cells of leaves and cotyledons (Fig. 2B, a and b). In 22-d-old plants, MCA1p::GUS was expressed weakly at the lower part of the inflorescence (Fig. 2B, h). Three independent MCA2p::GUS transgenic lines showed very similar GUS expression patterns, and four independent MCA1p::GUS transgenic lines showed essentially the same GUS expression pattern, although the levels of GUS expression varied from line to line. Detailed results for mature plants will be published elsewhere.

We also examined subcellular localization of the MCA2-GFP fusion protein produced under the control of the 35S promoter of the Cauliflower mosaic virus (CaMV) by fluorescence microscopy. Figure 2C (top row) suggested that MCA2-GFP was present in the plasma membrane of root cells. This suggestion was strengthened by treatment with a high osmotic solution, 0.8 m mannitol, which induced plasmolysis (Fig. 2C, bottom row). Fluorescent images and behavior of MCA2-GFP before and after plasmolysis were similar to those of the plasma membrane marker protein PIP2A and different from those of marker proteins for the endoplasmic reticulum and the vacuole as well as those of cytoplasmic GFP, all of which were expressed under the control of the CaMV 35S promoter (Cutler et al., 2000). This result is consistent with a structural feature that MCA2 has at least two potential transmembrane segments (Nakagawa et al., 2007). We noted that a portion of the MCA2-GFP proteins remained on the cell wall after plasmolysis, suggesting that this protein might associate with a cell wall component.

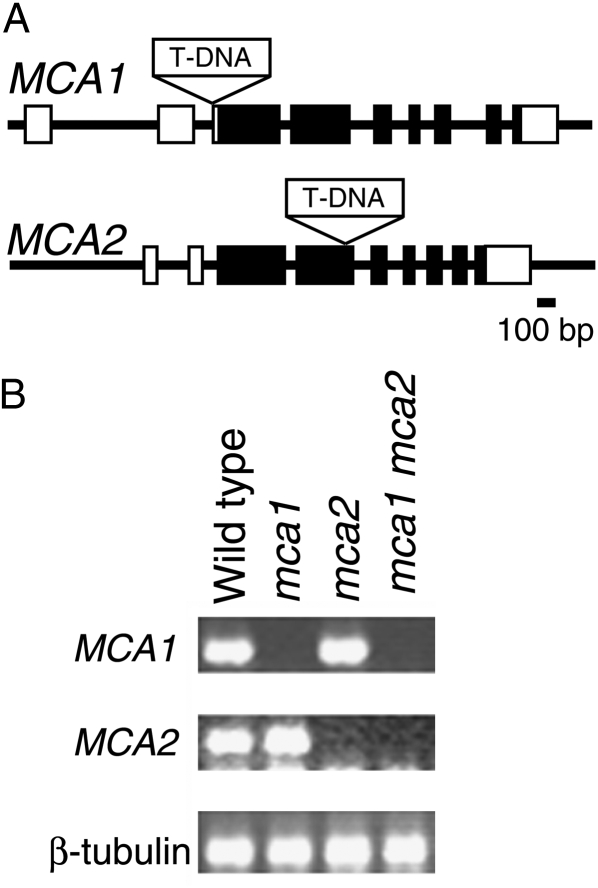

Basic Phenotypic Analysis of mca2-Null and MCA2-Overexpression Lines

To investigate the function of MCA2 in planta, we obtained the mca2-null mutant line SALK_129208 from the Arabidopsis Biological Resource Center. In this mutant line, T-DNA was inserted into the fourth exon of the MCA2 gene to disrupt the MCA2 open reading frame (Fig. 3A), resulting in no detectable production of the MCA2 transcript, as revealed by RT-PCR (Fig. 3B). To ensure that this mutation is a knockout, we compared the relative transcript levels of MCA2 in the mutant with wild-type transcript levels using quantitative real-time PCR with a primer set spanning from the fifth exon to the sixth exon. The result indicated that the levels of the MCA2 transcript were background levels in the mutant relative to the wild type (P < 0.05; Supplemental).

Figure 3.

Construction of the mca1-null mca2-null double mutant. A, Genomic organization of the MCA1 and MCA2 genes. Boxes represent exons, and their black areas show the open reading frame. The T-DNA is drawn to an arbitrary size. B, RT-PCR showing no detectable production of the MCA2 transcript in the mca2 and mca1-null mca2-null line. β -Tubulin mRNA is a control. RNA was purified from whole seedlings grown for 10 d.

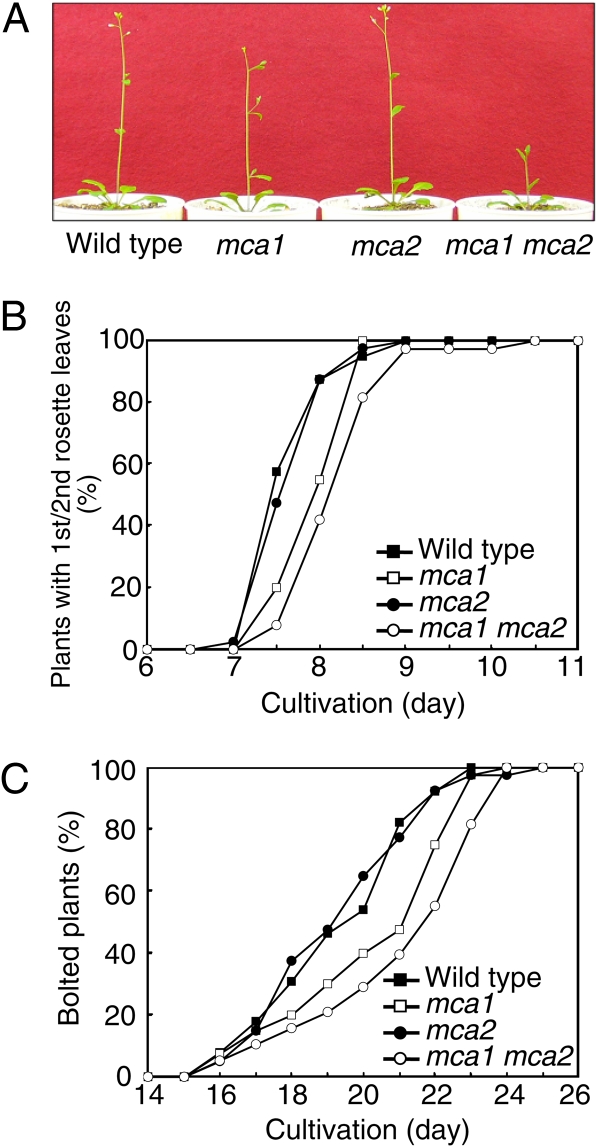

The mca2-null plants appeared to grow normally under the ordinary growth conditions we employed, like wild-type plants (Fig. 4A). Since MCA1 and MCA2 function similarly in yeast cells as described above and have the same structural features (Nakagawa et al., 2007), it is possible that the mca2-null mutation is complemented by the intrinsic MCA1 gene. We therefore constructed the mca1-null mca2-null double mutant by crossing the mca2-null mutant with the mca1-null mutant. RT-PCR revealed that neither the MCA1 nor MCA2 transcript was produced in the resulting double mutant (Fig. 3B). In addition, the quantitative real-time PCR described above indicated that the levels of the MCA1 and MCA2 transcripts were background levels in the double mutant relative to the wild type (P < 0.005 and P < 0.05, respectively; Supplemental).

Figure 4.

Growth phenotypes. A, Growth of wild-type, mca1-null, mca2-null, and mca1-null mca2-null plants. Plants were grown for 20 d on MS medium and for an additional 5 d in soil under a 16-h-light/8-h-dark cycle at 22°C. Bolting of the mca1-null mca2-null mutant was retarded. B, Timing of the appearance of first and second rosette leaves. Thirty-eight to 40 plants were grown for the indicated times on MS medium under a 16-h-light/8-h-dark cycle at 22°C. Percentages of plants that had developed first and second rosette leaves are indicated. A result representative of three independent experiments is shown. In all three experiments, the appearance of first and second rosette leaves was retarded most severely in the mca1-null mca2-null mutant followed by the mca1-null mutant, although the absolute timing of leafing varied from experiment to experiment. C, Timing for bolting. Thirty-eight to 40 plants were grown for 14 d on MS medium and for additional days in soil under a 16-h-light/8-h-dark cycle at 22°C. Percentages of bolted plants are indicated. A result representative of three independent experiments is shown. In all three experiments, the timing of bolting was retarded most severely in the mca1-null mca2-null mutant followed by the mca1-null mutant, although the absolute timing of bolting varied from experiment to experiment.

We then performed phenotypic analyses of these mutant lines. Unlike the mca1-null and mca2-null single mutants, the mca1-null mca2-null double mutant showed an obvious growth defect (Fig. 4A). The timing of germination of the seeds of the double mutant appeared to be normal on Murashige and Skoog (MS) medium (data not shown). We thus investigated the timing of leafing and bolting. The results showed that the appearance of first and second rosette leaves of the mca1-null mca2-null double mutant was retarded by about half a day (Fig. 4B) and that the bolting of the mutant was retarded by about 2 d, compared with that of the wild type (Fig. 4C). The leafing and bolting of the mca1-null single mutant were also retarded, and the delays were reproducibly smaller than those of the double mutant. These delays were not observed in the mca2-null single mutant. Thus, it is possible that MCA1 might compensate for the function of MCA2 in the mca2-null mutant but not vice versa. To examine this possibility, we investigated using quantitative real-time PCR whether the transcript levels of MCA1 are elevated in the mca2-null mutant. The result showed that the levels were not elevated in this mutant (Supplemental). Likewise, the transcript levels of MCA2 were not elevated in the mca1-null mutant.

We also constructed Arabidopsis mutant lines (designated MCA2ox) that overexpress MCA2 cDNA under the control of the 35S promoter of CaMV. Quantitative real-time PCR experiments showed that the three MCA2ox lines we examined had significantly increased levels of the MCA2 transcript (Supplemental). This figure also showed that the levels of the MCA1 transcript were not increased in the three MCA2ox lines. Contrary to MCA1ox lines whose growth is severely retarded (Nakagawa et al., 2007), MCA2ox lines grew normally (data not shown). This result suggests a possible difference in function between MCA1 and MCA2 under conditions for their overexpression in planta. An alternative possibility would be a difference in the expression levels and patterns of MCA1 and MCA2 in the shoot of wild-type plants. The GUS-staining experiments described above showed that the levels of MCA1p::GUS expression were much lower than those of MCA2p:GUS expression and that tissues expressing MCA1p::GUS seemed limited compared with those expressing MCA2p::GUS (Fig. 2B, f, h, n, and p). Thus, overexpression of MCA1 under the control of the 35S promoter may have a greater impact on plant growth than that of MCA2.

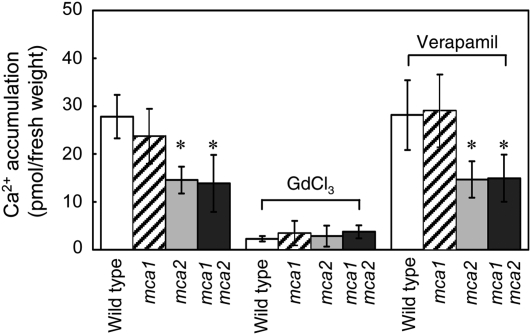

Ca2+ Uptake Is Defective in the Roots of Mature mca2-Null Plants

Since MCA2 has Ca2+ uptake activity when expressed in yeast cells (Fig. 1), we measured Ca2+ uptake in the intact roots of 5-week-old plants of various mutant lines using 45Ca2+. Figure 5 shows that Ca2+ uptake activity, which is sensitive to GdCl3 (a blocker for ion channels, including mechanosensitive channels) and resistant to verapamil (a voltage-gated Ca2+ channel blocker), was 46% and 50% lower in the mca2-null and mca1-null mca2-null mutant roots than wild-type ones, respectively. As already reported (Nakagawa et al., 2007), there was no significant difference in Ca2+ uptake activity between the mca1-null and wild-type roots (Fig. 5). Therefore, it is possible that the low Ca2+ uptake activity in the mca1-null mca2-null roots is ascribable to the disruption of the MCA2 gene only. In other words, MCA2, but not MCA1, functions as a major Ca2+ uptake protein in the roots under the experimental conditions we used.

Figure 5.

Ca2+ uptake activity of the roots of wild-type, mca1-null, mca2-null, and mca1-null mca2-null plants. Transgenic and wild-type plants were grown for 21 d on MS medium and for an additional 14 d in aerated hydroponics. Shoots were removed and roots were weighed and incubated for 20 min in an assay solution (2 mm KCl, 0.1 mm CaCl2, and 3 MBq/L 45CaCl2 [30 MBq/mmol]) in the absence and presence of 1 mm GdCl3, a blocker of mechanosensitive ion channels, or 20 μm verapamil, a blocker of voltage-gated Ca2+ channels. The roots were washed five times with a washing solution composed of 2 mm KCl, 0.1 mm CaCl2, and 1 mm LaCl3, and the radioactivity retained in the roots was counted in a liquid scintillation counter. Data are the mean ± sd for five independent experiments. *, P < 0.05 versus the wild type.

Sensing the Hardness of Agar Is Normal in the Primary Root of mca2-Null Seedlings

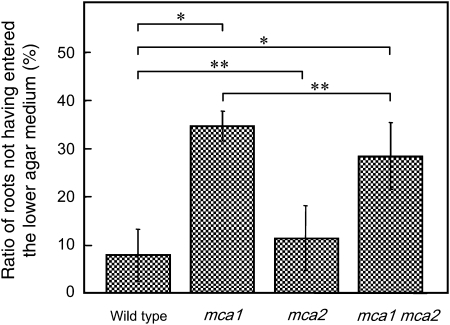

Since the primary root of the mca1-null seedlings is unable to sense and/or respond to the hardness of agar medium as revealed by the two-phase agar method (Nakagawa et al., 2007), we applied this method to the mca2-null seedlings. According to this method, seeds were sowed on the surface of the upper, softer (0.8%) agar medium made on the lower, harder (1.6%) agar medium and allowed to develop into seedlings for 9 d. As reported previously (Nakagawa et al., 2007), wild-type primary roots reached the interface of the two agar media in 5 to 7 d and then were capable of entering the lower, harder medium (Fig. 6). Essentially the same result was obtained with the mca2-null primary roots (Fig. 6). Therefore, MCA2 might not be responsible for sensing and/or responding to the hardness of agar in the primary root under our experimental conditions.

Figure 6.

Primary roots of mca1-null mca2-null plants, but not of mca2-null plants, fail to enter the lower, harder agar (1.6%) medium from the upper, softer agar (0.8%) medium. Seeds of transgenic and wild-type lines were sowed on the surface of the upper medium, incubated for 9 d, and photographed to examine the ability of the primary roots to enter the lower medium. The percentage of primary roots that had not entered the lower medium was calculated. Number of seedlings examined: wild type, n = 104; mca1-null, n = 91; mca2-null, n = 52; mca1-null mca2-null, n = 52. Data are the mean ± sd. *, P < 0.01; **, P > 0.05.

In contrast, the primary root of a significant population of the mca1-null mca2-null seedlings was unable to enter the lower, harder medium (Fig. 6). This result is phenotypically the same as that for the mca1-null seedlings (Nakagawa et al., 2007). Therefore, the phenotype of the double mutant might be ascribed to the disruption of the MCA1 gene only. The phenotypic difference between the mca1-null and mca2-null mutants may be related to a difference in spatial expression of the two genes in the tip of the primary root, as described above (see Discussion).

Development of the Primary Root Is Normal in mca2-Null Seedlings But Not in mca1-Null mca2-Null Seedlings

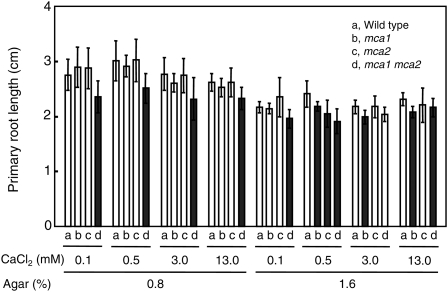

Although the two-phase agar method revealed no detectable difference in the phenotype of the primary root between mca2-null and wild-type seedlings, the primary root's development might still be affected. To examine this possibility, we measured the length of the primary root of the wild type and the null mutants grown at different concentrations of agar and CaCl2. Seeds were sown on MS medium containing 0.8% or 1.6% agar and 0.1, 0.5, 3.0, or 13.0 mm CaCl2 and incubated for 9 d. Note that ordinary MS medium contains 0.8% agar and 3.0 mm CaCl2. The primary roots were then taken out and laid softly on MS medium containing 1.6% agar to become straight for the measurement of length. This experiment was performed three times independently, and similar results were obtained. Figure 7 shows a representative result. As a whole, the primary roots of every line were slightly shorter in 1.6% agar medium than in 0.8% agar medium irrespective of CaCl2 concentration. In 0.8% agar medium, the primary root length of the mca1-null and mca2-null single mutants was essentially the same as that of the wild type regardless of the CaCl2 concentrations tested. However, the mca1-null mca2 null double mutant had a shorter primary root than the single mutants as well as the wild type. This phenotype was not effectively suppressed by a high concentration of CaCl2 (13 mm). Since 13 mm CaCl2 seemed to shorten slightly the primary root of the wild type grown in 0.8% agar medium (Fig. 7), CaCl2 at this concentration might have both positive and negative effects on the short root length phenotype of the mca1-null mca2 null double mutant. In 1.6% agar medium, similar results were observed for every line with some exceptions. For example, at 3.0 mm CaCl2, there was no significant difference in the length of the primary root between the mca1-null mca2-null double mutant and the wild type, although a small difference (P < 0.05, n = 15) was observed between the mca1-null single mutant and the wild type. The latter observation was inconsistent with that reported previously (Nakagawa et al., 2007). This inconsistency could be due to a measurement error because there was no significant difference between the mca1-null mutant and the mca1-null mca2-null mutant (P > 0.05, n = 15). Taken together, it is suggested that only the primary root of the double mutant has an obvious slow growth phenotype in most of the growth conditions we employed and that this phenotype is not rescued by a high concentration of CaCl2.

Figure 7.

Effect of the concentration of agar and CaCl2 on primary root growth. Seeds of transgenic and wild-type lines were sowed on MS medium containing 0.8% or 1.6% agar and 0.1, 0.5, 3.0, or 13.0 mm CaCl2 and incubated for 9 d. Seedlings were picked up, laid on another MS/1.6% agar medium, and photographed. Primary root length was measured with ImageJ software. The length is presented as the mean for 15 seedlings of each line with the sd. A result representative of three independent experiments is shown. a, Wild-type seedling; b, mca1-null seedling; c, mca2-null seedling; d, mca1-null mca2-null seedling. The black bar represents null lines whose primary root lengths are significantly shorter (P < 0.05) than those of the wild-type line under each incubation condition.

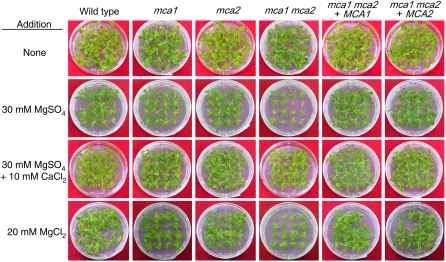

External Excess Mg2+ Retards the Growth of the mca1-Null mca2-Null Mutant

Since Ca2+ and Mg2+ compete for the same sites of absorption on the plant plasma membrane (Yermiyahu et al., 1994), it is possible that an increase in the Mg2+ concentration in medium negatively affects the growth of plants lacking either MCA1 or MCA2 or both. Figure 8 shows the effect of adding Mg2+ to the medium on the growth of those lines. The mca1-null mca2-null double mutant exhibited a severer growth defect when grown for 24 d on MS medium with 30 mm MgSO4 added, compared with that of the mca1-null and mca2-null single mutants and the wild type. This phenotype was partially alleviated by adding 10 mm CaCl2 to the medium containing 30 mm MgSO4. The mca1-null mca2-null double mutant also exhibited a severe growth defect when grown on MS medium with 20 mm MgCl2. This result suggests that the phenotype is due to excess Mg2+. Complementation of the mca1-null mca2-null double mutant with the extrinsic wild-type MCA1 or MCA2 gene confirmed that MCA1 and MCA2 are indeed responsible for this phenotype. The Mg2+-induced growth defect of the mca1-null and mca2-null single mutants was comparable to that of the wild type, indicating that MCA1 and MCA2 redundantly function under the high Mg2+ growth conditions we employed.

Figure 8.

Severe growth defect of the mca1-null mca2-null mutant grown on medium containing high Mg2+. Plants were grown for 24 d on MS medium under 16-h-light/8-h-dark conditions at 22°C and photographed. Note that the color tone of each sample varies delicately from photograph to photograph; thus, a difference in the color tones presented here is not a significant factor for the interpretation of the results. Also note that the retardation of growth in the mca1-null mca2-null mutant presented in Figure 4 is not obvious in the first row of Figure 8 showing the transgenic lines grown on MS medium with no additive because upper views are shown.

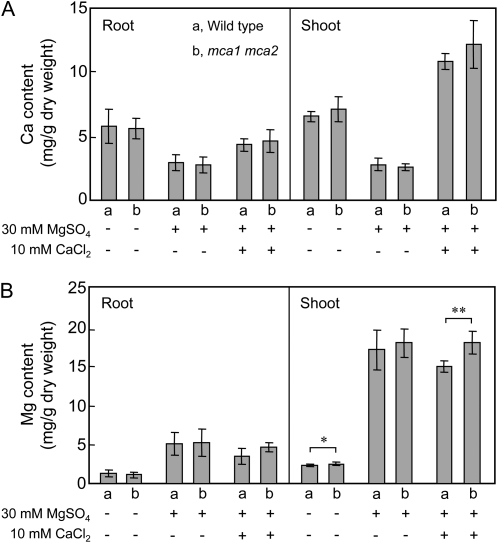

To test the possibility that the Mg2+-induced growth defect observed in mca1-null mca2-null double mutant is due to an inhibitory effect of Mg2+ on Ca2+ accumulation in plants, we measured the levels of Ca and Mg in the root and shoot of the wild type and mca1-null mca2-null plants grown for 24 to 26 d on MS medium with or without 30 mm MgSO4 (Fig. 9). In control MS medium to which MgSO4 was not supplemented, the Ca and Mg contents of the double mutant did not differ significantly from those of the wild type in both roots and shoots (P > 0.05, n = 3). When 30 mm MgSO4 was included in MS medium, the Ca content was decreased by approximately 50% in roots and 60% in shoots, whereas the Mg content was increased approximately 5-fold in roots and 7-fold in shoots. Notably, however, the degrees of the increase and decrease in both Ca and Mg contents were not significantly different between the mca1-null mca2-null and wild-type plants (P > 0.05, n = 3). When 10 mm CaCl2 was added to the MS/Mg medium, the Ca content was recovered nearly to the control level in roots and increased more than the control level in shoots, whereas the Mg content hardly changed. Again, the Ca content was not different between the mca1-null mca2-null and wild-type plants (P > 0.05, n = 3). These results indicate that while Mg2+ added to MS medium indeed lowers Ca2+ accumulation in plants, this effect influences equally both wild-type and mca1-null mca2-null plants. Therefore, the Ca content seems not to explain the Mg2+-induced growth defect observed in mca1-null mca2-null mutant.

Figure 9.

Ca and Mg accumulation in mca1-null mca2-null and wild-type plants. Plants were grown for 24 to 26 d under the conditions described in the legend to Figure 8, and roots and shoots were subjected to inductively coupled plasma atomic emission spectrometer analysis to determine the content of Ca (A) and Mg (B). a, Wild-type plants; b, mca1-null mca2-null plants. Data are the mean ± sd of three independent experiments. Note that there was no significant difference (P > 0.05) in the Ca and Mg contents between mca1-null mca2-null and wild-type plants, except for two cases (*P = 0.0207; **P = 0.0026).

DISCUSSION

MCA2 Mediates Ca2+ Uptake in Yeast

In this study, we have shown that the Arabidopsis MCA2 cDNA complements both the lethality and low Ca2+ uptake activity of the yeast mid1 mutant defective in a putative Ca2+-permeable mechanosensitive channel component (Fig. 1). In addition, MCA2 also complements the cch1 single mutant and the mid1 cch1 double mutant. Since this complementing activity of MCA2 is the same as that of MCA1 (Nakagawa et al., 2007), we conclude that MCA2 has the same function as MCA1 in yeast cells regarding Ca2+ uptake.

The yeast S. cerevisiae has only one high-affinity Ca2+ influx system, which is composed of Mid1 and Cch1 and becomes functional when cells are grown in low Ca2+ media, such as SD.Ca100 medium that contains 100 μm CaCl2 as the sole Ca2+ source (Muller et al., 2001). Since we have used the SD.Ca100 medium to measure the complementing activity of MCA2 in the mid1, cch1, and mid1 cch1 mutants, it is likely that MCA2 alone can constitute a Ca2+ influx system, independently of yeast Ca2+ influx systems. This interpretation is applicable to the function of MCA1 in yeast (Nakagawa et al., 2007). In this context, it is interesting to investigate whether the two proteins can form a homomultimeric complex. Our recent study using SDS-PAGE under nonreducing conditions has shown that both proteins expressed in yeast cells form a homodimer and homotetramer (M. Nakano, K. Iida, H. Nyunoya, and H. Iida, unpublished data). We have also obtained data showing that MCA2 is localized in the yeast plasma membrane (M. Nakano, K. Iida, H. Nyunoya, and H. Iida, unpublished data), and this result is consistent with the observation that MCA2-GFP is localized in the plasma membrane of Arabidopsis root cells (Fig. 2C). Since MCA1 is reported to be a plasma membrane protein in yeast and Arabidopsis (Nakagawa et al., 2007), it is concluded that both MCA1 and MCA2 mediate Ca2+ influx in the plasma membrane.

Relevance of the Spatial Pattern of MCA1 and MCA2 Expression to Calcium Nutrition

Our GUS staining experiments have suggested that in the primary root, both MCA1 and MCA2 are expressed in the stele and endodermis, but not in surrounding tissues, such as the cortex and epidermis (Fig. 2B). Considering this spatial expression pattern and a role for Ca2+ influx in the plasma membrane, it is possible that both proteins are involved in symplastic Ca2+ transport and/or the generation of a Ca2+ signal in endodermal and vascular cells.

In terms of calcium nutrition, do MCA1 and MCA2 have a role? The delivery of Ca2+ from the soil solution to the xylem is thought to be dependent on both apoplastic and symplastic pathways, although the relative magnitude of Ca2+ transport through the two pathways is unknown, and it is suggested that the Ca2+ influx system in the plasma membrane of endodermal cells plays a major role in symplastic Ca2+ transport (White, 2001; White and Broadley, 2003; Cholewa and Peterson, 2004; Hayter and Peterson, 2004). The cortex and epidermis contribute to apoplastic Ca2+ transport. Thus, it seems likely that the current notion for Ca2+ transport to the xylem meets the spatial expression and potential function of MCA1 and MCA2. However, our experiments on the determination of the Ca content are not consistent with this possibility. Namely, the Ca content was shown to be essentially the same between the mca1-null mca2-null and wild-type plants (Fig. 9), although the double mutant showed a slow growth phenotype (Fig. 4) and had a relatively short primary root (Fig. 7). In addition, although Ca2+ uptake activity of the mca2-null mutant is significantly lower than that of the wild type, this mutant does not show any defect regarding growth under our experimental conditions (Figs. 4, 7, and 8). Therefore, a possible role of MCA1 and MCA2 in calcium nutrition, if any, remains to be investigated with further studies.

Why do mca2-null roots have low Ca2+ uptake activity relative to wild-type roots, while mca1-null roots have a wild-type level of the activity? It is possible that deletion of the MCA2 gene results in the up-regulation of the MCA1 transcript. Our real-time PCR data, however, do not support this possibility because the amount of the MCA1 transcript in the mca2-null mutant was the same as that in the wild type (Supplemental). The second possibility is a difference in the spatial expression of MCA1 and MCA2 in the root. Our data with GUS staining, however, appears not to sustain this possibility too. Both MCA1p::GUS and MCA2p::GUS were found to be expressed throughout the root, except that while MCA1p::GUS was expressed in most regions of the root tip, MCA2p::GUS was not (Fig. 2B). It is reported that the root tip is not the only site of Ca2+ uptake (White, 2001; Cholewa and Peterson, 2004). Cholewa and Peterson (2004) found that the tip (apical 8 mm) of the onion adventitious root (maximum 160 mm long) did not translocate Ca2+ to the transpiration stream and explained that this would be due to a lack of mature xylem in the tip. Huang et al. (1993) reported that the tip (apical 5–15 mm) of wheat (Triticum aestivum) roots (80–93 mm long) contributed to only about 30% of total Ca2+ translocation to the shoot. The third possibility is a functional difference between MCA1 and MCA2 in cells of the root. Although the two proteins were suggested to have roughly similar levels of Ca2+ uptake activity when expressed in yeast cells (Fig. 1A), MCA2 might have a greater activity of Ca2+ uptake than MCA1 in cells of the root. Further studies are needed to test this possibility.

The delay of leafing and bolting seen in the mca1-null and mca1-null mca2-null mutants (Fig. 4) may be related to the expression of MCA1 at the center of rosettes in a region corresponding to the shoot apical meristem (Fig. 2B, d). In this region, MCA1p::GUS was suggested to be expressed more intensively than MCA2p::GUS (Fig. 2B, l). Since this region contains actively dividing cells to produce rosette leaves and the inflorescence, deletion of MCA1 could affect the timing of leafing and bolting severer than that of MCA2.

Relevance of the Spatial Pattern of MCA1 and MCA2 Expression to Ca2+ Signaling

Differential expression of MCA1p::GUS and MCA2p::GUS in the root apical meristem and adjacent elongation zone (Fig. 2B, c and k) appears to explain a phenotypic difference in the ability to enter the harder agar form the softer agar between the mca1-null and mca2-null roots (Fig. 6). Although the root cap, where MCA1p::GUS and MCA2p::GUS are not expressed, is reported to be a site for sensing touch stimuli (Darwin, 1880; Massa and Gilroy, 2003), the root elongation zone, where MCA1p::GUS, but not MCA2p::GUS, is expressed, could be a site for mechanosensing and/or mechanotransduction. It is shown that touch stimulation induces an increase in [Ca2+]cyt not only in the root cap but also in the root elongation zone in Arabidopsis (Legué et al., 1997). In addition, it is shown that the maize (Zea mays) primary root whose cap has been surgically removed still has an ability to curve away from a small piece of agar applied unilaterally to the decapped tip (Ishikawa and Evans, 1992). This negative curvature response is somewhat reinforced when Ca2+ is included in the agar. In addition, the same authors have shown that unilateral application of agar containing Ca2+ to the distal elongation zone or elongation zone induces positive curvature, and this response is not observed when plain agar is applied. Thus, it is of interest to investigate whether MCA1 takes part in touch sensing and signal transduction in the root apical meristem and/or the adjacent elongation zone.

In terms of Ca2+ signaling, the endodermis and pericycle of the root, where MCA1p::GUS and MCA2p::GUS are expressed, are thought to be important regions. It is suggested that endodermal and pericyclar cells may have a Ca2+ signaling system in response to drought and salt stress because these cells respond with an initial peak and a lower secondary rise in the cytosolic Ca2+ concentration (Kiegle et al., 2000). We are now studying the role of MCA1 and MCA2 in the salt stress response.

Recent molecular and electrophysiological studies have shown that Arabidopsis MSL9 and MSL10, homologs of the bacterial mechanosensitive channel MscS, are required for a mechanosensitive channel activity in the plasma membrane of root cells and permeable to Ca2+, though more permeable to Cl− than Ca2+ (Haswell et al., 2008). It is noteworthy that their expression patterns, especially those of MSL10, are similar to those of MCA1, as revealed by GUS-staining analysis. For example, both MCA1 and MSL10 are expressed in the root tip and throughout the vasculature of the root and leaf. msl9, msl10, and msl9 msl10 mutants and even the msl4 msl5 msl6 msl9 msl10 quintuple mutant showed no detectable phenotype upon osmotic, salt, mechanical, dehydration, or rehydration stress (Haswell et al., 2008), suggestive of the presence of a complementary mechanism. It is worth examining the possible genetic interaction between MSL and MCA.

Increased Sensitivity of mca1-Null mca2-Null Double Mutant to Excess Mg2+ Is Alleviated by Adding Ca2+

The mca1-null mca2-null mutation causes a severe growth defect on media supplemented with 30 mm MgSO4 or 20 mm MgCl2 (Fig. 8). Interestingly, this phenotype is opposite to that of the Arabidopsis cax1 mutant (Bradshaw, 2005). CAX1 is a high-capacity calcium-proton antiporter located on the tonoplast membrane. The cax1-null mutant shows tolerance to low Ca2+:Mg2+ratios, at which the growth of the mca1-null mca2-null mutant is slowed. The phenotype of the cax1 mutant is explained as follows: An absence of sequestration of cytosolic Ca2+ to the vacuole by CAX1 reduces Mg2+ toxicity. In this context, it is possible that the phenotype of the mca1-null mca2-null mutant is due to the deficiency of Ca2+ influx to the cytoplasm, resulting in low Ca2+:Mg2+ ratios there, thus causing Mg2+ toxicity.

The balance of Ca2+ and Mg2+ in soil is an important factor for plant growth. Plants cannot grow normally in soil with low Ca2+:Mg2+ ratios, which is thought to be a main reason for the growth defect in serpentine soils derived from the weathering of ultramafic rocks and characterized by the presence of excessive Mg, high levels of heavy metals, and low levels of important plant nutrients, including Ca. Studies of serpentine-tolerant and serpentine-intolerant plant species suggested that the adaptation to serpentine soils is mediated by unknown genetic elements (Brady et al., 2005; Asemaneh et al., 2007). To explore elements involved in tolerance to soil with low Ca2+:Mg2+ ratios, a genetic approach using Arabidopsis has been performed and has isolated the cax1 mutant described above (Bradshaw, 2005). The molecular identity of other elements is basically unknown. However, proteins involved in Ca2+ uptake, including MCA1 and MCA2, could be appropriate candidates for the elements.

Our study demonstrated that the addition of 30 mm MgSO4 to MS medium decreased the Ca content by approximately half in roots and more than half in shoots (Fig. 9), suggesting that this decrease is associated with the slow growth of both mca1-null mca2-null and wild-type plants. This suggestion is supported by the observation that supplementation of CaCl2 to the Mg-rich medium remedied partially the Mg2+-induced severe growth defect of the double mutant. However, no significant difference in the Ca content was detected between the mca1-null mca2-null and wild-type plants, suggesting that the Mg2+-induced severe growth defect observed in the double mutant is not simply explained by the Ca content of plants. Since the majority of the total Ca2+ is bound to the cell wall and anionic macromolecules in the cell (Hirschi, 2004), free Ca2+ rather than bound Ca2+ would be related to the Mg2+-induced severe growth defect. We speculate that the intracellular free Ca2+ supplied through MCA1 and MCA2 from the bound Ca2+ and/or free Ca2+ included in medium could play an important role in plant growth and development.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Subcloning of MCA2 cDNA in a Yeast Expression Vector

MCA2 cDNA (locus name, At2g17780) with a BamHI site at each of the 5′- and 3′-ends was synthesized by PCR using the plasmid pBluescript SK− MCA2 as a template and the primers B-5′Bam (409F), 5′-GGGGATCCATGGCTAATTCATGGGATCAGTTAG-3′, and B3-3′SB (1659R), 5′-GGGTCGACGGATCCTTCATTCTTCCATAAACTGAGGTGTTGGTG-3′, where the BamHI site is underlined and the initiation and termination codons are boldfaced. The resulting product was cut with BamHI and inserted into the BamHI site of a YEplac181-based, multicopy expression vector, YEpTDHXho (Gietz and Sugino, 1988; Hashimoto et al., 2004), in which a cDNA of interest is transcribed under the control of the TDH3 promoter. The resulting plasmid was designated YEpTDHXho-MCA2.

Yeast Strains and Medium Used in This Study

The parental strain used was H207 (MATa his3- Δ1 leu2-3,112 trp1-289 ura3-52 sst1-2; Iida et al., 1994). The following mutant strains were derivatives of H207:H311 (MATa mid1- Δ5::HIS3; Tada et al., 2003), H317 (MATa cch1Δ ::HIS3; Iida et al., 2007), and H319 (MATa mid1- Δ5::HIS3 cch1Δ ::HIS3; Nakagawa et al., 2007). The low Ca2+ medium SD.Ca100 (Iida et al., 1990, 1994), which contains 100 μm CaCl2 as the Ca2+ source, was used in most of this study. The yeast strains were transformed with YEpTDHXho-MCA1 (Nakagawa et al., 2007) and YEpTDHXho-MCA2 by a method described previously (Mount et al., 1996).

Yeast Cell Viability Assay

Yeast cells were grown to the exponentially growing phase (2 × 106 cells/mL) in SD.Ca100 medium at 30°C and incubated with 6 μm α -factor for 8 h, after which viability was determined by the methylene blue method (Iida et al., 1990).

Ca2+ Accumulation in Yeast

The method of Iida et al. (1990) was followed. Yeast cells were grown to 2 × 106 cells/mL in SD.Ca100 medium at 30°C and incubated for 2 h with 185 kBq/mL 45CaCl2 (1.8 kBq/nmol). Samples (100 μ L) were filtered with Millipore filters presoaked with 5 mm CaCl2 and washed five times with the same solution. The radioactivity retained on each filter was counted as described previously (Iida et al., 1990).

Plant Growth Conditions

The Columbia-0 (Col-0) ecotype of Arabidopsis (Arabidopsis thaliana) and its isogenic, transgenic lines were used. Seeds were sterilized with 70% ethanol and 1% Antiformin and sown on MS medium composed of MS salts (Murashige and Skoog, 1962), 1 × Gamborg's vitamin solution (Sigma-Aldrich), 2.56 mm MES-KOH (pH 5.7), 1% Suc, and 0.8% agar. Additional CaCl2, MgSO4, and MgCl2 were added to the MS medium after autoclaving. In some experiments, plants were transferred to soil (Dio Chemicals) after bolting. Plants were grown under 16-h-light/8-h-dark conditions at 40 to 60 μm m−2 s−1 and 22°C.

Establishment of the mca2-Null Mutant and the mca1-Null mca2-Null Double Mutant

Arabidopsis seeds with a T-DNA inserted in the MCA2 gene (SALK_129208) were obtained from the Arabidopsis Biological Resource Center (Columbus, OH). Confirmation of the insertion was conducted by genomic PCR using a set of the T-DNA left border primer LBa1 (forward, 5′-TGGTTCACGTAGTGGGCCATCG-3′) and the MCA2-specific primer Ap1237 (reverse, 5′-GAGGTGTTGGTGGACTCATTTCCTTATTAC-3′) that binds to the ninth exon of the MCA2 gene. Then, the homozygous and heterozygous mca2 T-DNA insertion mutations were confirmed by genomic PCR using the MCA2-specific primer Ap1s (forward, 5′-ATGGCTAATTCATGGGATCAGTTAG-3′) that binds to the third exon of the MCA2 gene and Ap1237 (reverse; see above). The mca1-null line produced by the insertion was described previously (Nakagawa et al., 2007). To construct the mca1-null mca2-null double mutant, the mca1-null mutant was crossed with the mca2-null mutant, and the F1 generation was self-crossed to produce the F2 generation. The resulting plants were confirmed to be homozygous for the mca1-null mca2-null alleles by isolation of total RNA followed by RT-PCR. Total RNA was isolated from whole plants grown for 10 d on MS medium using the RNeasy plant mini kit (Qiagen). The primers for RT-PCR were as follows: for MCA1 mRNA, 5′-TGCTCCCTCTTTTAGTCAATTCTCG-3′(forward primer) and 5′-CCTGTTGGATGCTGCAGTGGCAATC-3′(reverse primer); for MCA2 mRNA, 5′-ATGGCTAATTCATGGGATCAGTTAG-3′(Ap1s) and 5′-GAGGTGTTGGTGGACTCATTTCCTTATTAC-3′(Ap1237); and for control β -tubulin mRNA, 5′-ATCCCACCGGACGTTACAAC-3′and 5′-TTCGTTGTCGAGGACCATGC-3′.

Isolation of Total RNA from Various Tissues for RT-PCR

Total RNA was isolated from various tissues of plants grown for 5 to 6 weeks using the RNeasy plant mini kit (Qiagen) or by the method described by Miyama and Tada (2008). Aliquots (1 μ g) of total RNA were subjected to cDNA synthesis using a reverse primer (5′-GAGGTGTTGGTGGACTCATTTCCTTATTAC-3′for MCA2 [Ap1237] and 5′-TTCGTTGTCGAGGACCATGC-3′for β -tubulin as a control) and a TaKaRa RNA PCR kit (AMV), version 3.0 (Takara Bio), according to the manufacturer's protocol. Then, using a specific primer set (5′-ATGGCTAATTCATGGGATCAGTTAG-3′[Ap1s] and 5′-GAGGTGTTGGTGGACTCATTTCCTTATTAC-3′for MCA2 [Ap1237]; 5′-ATCCCACCGGACGTTACAAC-3′and 5′-TTCGTTGTCGAGGACCATGC-3′for β -tubulin) and the synthesized cDNA as a template, PCR amplifications were performed using a TaKaRa RNA PCR kit (AMV), version 3.0, as follows: 35 cycles of 94°C for 1 min, 55°C for 1 min, and 72°C for 2 min.

Quantitative Real-Time PCR

Total RNA was purified from 5 to 10 plants grown for 13 d on MS medium using an RNeasy plant mini kit, treated with DNase I (Takara Bio), and used for cDNA synthesis with Superscript III reverse transcriptase (Invitrogen), random primer (Takara Bio), and oligo(dT)12-18 (Invitrogen). Quantitative real-time PCR was performed with the 7500 Fast Real-Time PCR system (Applied Biosystems). The PCR mixture consisted of a first-strand cDNA template, the SYBR GREEN PCR Master Mix (Applied Biosystems), and the following primers: for MCA1, 5′-AAGATTGCCACTGCAGCATCC-3′(forward primer) and 5′-ACGCCATTAGCTCATTACATGCTTC-3′(reverse primer); for MCA2, 5′-AAGATCATTGCAACACCGTGGA-3′and 5′-GTGTCTTCAAGCAAAGACAAGGTTC-3′; for EF1 α, 5′-TGAGCACGCTCTTCTTGCTTTCA-3′and 5′-GGTGGTGGCATCCATCTTGTTACA-3′; and for β -tubulin as a control, 5′-ACCACTCCTAGCTTTGGTGATCTG-3′and 5′-AGGTTCACTGCGAGCTTCCTCA-3′. In all cases, the expression of each transcript was corrected with that of β -tubulin measured in the same sample in parallel on the same plate.

GUS Assay of MCA1p::GUS and MCA2p::GUS Transgenic Plants

The DNA fragment of the MCA1 promoter region was prepared with PCR by synthesizing the 5′-noncoding region spanning −3.0 to 0 kb from the 5′-end of the first exon using Arabidopsis (Col-0) genomic DNA as a template and the following primers: forward primer (RF4B14-81934), 5′-AACGTACTGGATTATTAATTGAGTG-3′; reverse primer (BmFF4B14-78800), 5′-CGGGATCCGGAGCTCAAGAGCCCCC-3′, where the underline indicates the BamHI site. The MCA1 promoter region synthesized, which contains the intrinsic HindIII site near the forward primer, was inserted between the HindIII and BamHI sites of the GUS expression vector pBI121 (CLONTECH).

The DNA fragment of the MCA2 promoter region was prepared with PCR by synthesizing the 5′-noncoding region spanning −1.5 to 0 kb from the initiation codon of the MCA2 gene using Arabidopsis (Col-0) genomic DNA as a template and the following primers: forward primer (pA2″pro1), 5′-GGAAGCTTGGAGGGAAGCAGTTTATAATG-3′, where the underline indicates the HindIII site; reverse primer (pA2″pro2), 5′-GGTCTAGACTCTTCCTAACCAAAAACAGC-3′, where the underline indicates the XbaI site. The MCA2 promoter region synthesized was inserted between the HindIII and XbaI sites of the promoterless GUS expression vector pBI101 (CLONTECH).

The resulting plasmid containing either the MCA1p::GUS or MCA2p::GUS fusion construct was introduced into Escherichia coli DH5 α and then transferred from it to Agrobacterium tumefaciens GV3101 containing pMP90 via triparental mating with a helper E. coli strain containing the mobilization plasmid pRK2013 as described previously (Valvekens et al., 1988; Benfey et al., 1993). Arabidopsis plants (Col-0) were transformed by the vacuum infiltration method (Bechtold et al., 1993; Bechtold and Pelletier, 1998). T2 and T3 transgenic Arabidopsis plants were grown at 22°C under a 16-h-light/8-h-dark cycle for experiments. Histochemical localization of GUS activity in situ was performed as follows. Samples were fixed for 1 h with 90% acetone in Eppendorf tubes placed on ice and washed four times with 100 mm sodium phosphate buffer, pH 7.0. The samples were then incubated for 6 h at 37°C in 1 mL of X-Gluc buffer (0.5 mg/mL 5-bromo-4-chloro-3-indolyl glucuronidase [CLONTECH], 100 mm sodium phosphate buffer, pH 7.0, 0.5 mm potassium ferrocyanide, and 0.5 mm potassium ferricyanide) and then cleaned and fixed by rinsing for 1 h each with 50%, 70%, 90%, and 100% (v/v) ethanol successively. The fixed samples were stored in 100% ethanol before being photographed under a stereomicroscope (Leica MZ125) or a differential interference contrast microscope (Olympus BX50).

Observation of Subcellular Localization of MCA2-GFP in Root Cells

To generate transgenic plants expressing MCA2-GFP, the coding region of the MCA2 cDNA was amplified by PCR using primers 5′-TGGATCCATGGCTAATTCATGGGATCAG-3′and 5′-TGGATCCTTCTTCCATAAACTGAGGTG-3′, where the BamHI site was underlined. After treatment with BamHI, the product was inserted into the BamHI site of the pBE2113 vector (Mitsuhara et al., 1996) so that the MCA2 sequence would be fused in frame to the 5′-end of the GFP gene and the resulting MCA2-GFP fusion gene would be driven by the CaMV 35S promoter. The transformation plasmid was introduced into Agrobacterium to transform wild-type Arabidopsis (Col-0) plants. T3 seeds were used for GFP fluorescence imaging.

GFP fluorescence images were observed using a confocal fluorescence microscope equipped with a Nikon TE 300 in conjunction with Micro Radiance (Bio-Rad). Nikon Plan Apo 60 × /1.40 oil was used as an objective lens. Images were processed using Adobe Photoshop Element 6.0 (Adobe Systems). The Arabidopsis GFP T-DNA tag lines Q4, Q5, and Q8 donated by D. Ehrhardt, S. Cutler, and C. Somerville (Cutler et al., 2000) were obtained from the Arabidopsis Biological Resource Center.

Measurement of Primary Root Length

Seeds were sterilized, chilled for 3 d at 4°C in the dark, and sown on MS medium. Seedlings were grown under 16-h-light/8-h-dark conditions for 9 d at 22°C. To measure the length of the primary root, 15 seedlings were laid and straightened softly on another MS/1.6% agar medium and photographed as digital data. Root length was measured with ImageJ software (http://rsb.info.nih.gov/ij/), and the average and sd of the samples were determined.

Complementation of the mca1-Null mca2-Null Mutation

For complementation by the MCA1 gene, the T-DNA clone pGreenII0229-MCA1-MS (Nakagawa et al., 2007) was used for plant transformation. For complementation by the MCA2 gene, the T-DNA clone pGreenII0229-MCA2 was constructed. A DNA fragment harboring the MCA2 gene was amplified from Arabidopsis Col-0 genomic DNA by PCR using pfu DNA polymerase (Stratagene). The primers used for the PCR have a BamHI site at their 5′terminus. Their sequences are 5′-CGGGATCCTCAAGTGTTTCTTATGAAGATG-3′and 5′-CGGGATCCATATCTCTTAGTTCTATTAGAC-3′. The amplified fragment was ligated into the BamHI site of the T-DNA vector pGreenII0229. pGreenII0229-MCA2 and the helper plasmid pSOUP (Hellens et al., 2000) were coelectroporated into Agrobacterium GV3101 containing pMP90 and used to transform Arabidopsis mca1-null mca2-null plants by the floral dipping method (Desfeux et al., 2000). Transgenic plants were selected on MS medium, 10 μm Basta, and 100 μ g/mL Carbenicillin. Successful construction of a complementation line was confirmed by genomic PCR using a vector-specific primer for MCA1 complementation (5′-TGAATTGTAATACGACTCACTATAG-3′), an MCA1-specific primer (5′-TCGAACTTCAGCGGTCGCAGGAGCA-3′), a vector-specific primer for MCA2;complementation (5′-TGGTTCACGTAGTGGGCCATCGG-3′), and MCA2-specific primer (5′-GAGGTGTTGGTGGACTCATTTCCTTATTAC-3′). T3 homozygous lines were used to examine mca1-null mca2-null phenotypes.

Ca2+ Uptake in Intact Arabidopsis Roots

Ca2+ uptake was measured according to the method described by Nakagawa et al. (2007). Briefly, plants were grown for 21 d on standard MS medium containing 0.8% agar and for an additional 14 d in aerated hydroponics according to Demidchik et al. (2002). Shoots were removed from the plants, and roots were weighed, incubated for 20 min in an assay solution (2 mm KCl, 0.1 mm CaCl2, and 3 MBq/L 45CaCl2 [30 MBq/mmol; Perkin-Elmer, catalog no. NEZ013]) in the absence or presence of 1 mm GdCl3 or 20 μm verapamil, and then washed five times with a 45CaCl2-free solution containing 2 mm KCl, 0.1 mm CaCl2, and 1 mm LaCl3 to remove 45Ca2+ from the cell wall. Radioactivity retained in the roots was measured with a liquid scintillation counter.

Determination of Ca and Mg Contents in Roots and Shoots

Approximately 10 plants grown for 24 to 26 d on MS medium or that containing 30 mm MgSO4 with or without 10 mm CaCl2 were separated into roots and shoots (approximately 0.1 g wet weight each). The samples were washed in water deionized with Milli-Q Plus (Millipore) and dried for 16 h at 92°C in 25-mL Teflon vessels (Isis). The dried samples were weighed with a Mettler analytical balance (model AE163) and incubated for 3 h at 120°C in 2.3 mL of HNO3 (Wako Pure Chemical Industries) to be fully dissolved. The dissolved samples were filled up to 100 mL with Milli-Q water, and Ca and Mg contents of aliquots (approximately 10 mL or less) were determined with an inductively coupled plasma atomic emission spectrometer (model SPS 1200A; Seiko Instruments).

Two-Phase Agar Method

The method described by Nakagawa et al. (2007) was strictly followed.

Statistical Analysis

Statistical significance was determined using an unpaired Student's t test, with a maximum P value of < 0.05 required for significance.

Sequence data from this article can be found in the GenBank/EMBL/DDBJ data libraries under accession numbers AB196960 for MCA1 and AB196961 for MCA2.

Supplemental Data

The following materials are available in the online version of this article.

Supplemental Figure S1. The levels of the MCA1 and MCA2 transcripts in various MCA1 and MCA2 mutants.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Akitoshi Iwamoto for advice on histochemical techniques, Dr. Masayoshi Maeshima for critical reading of the manuscript and valuable comments, Dr. Shuji Ninomiya for advice on the determination of Ca and Mg contents, Drs. Masahiro Sokabe, Hitoshi Tatsumi, and Kazuyuki Kuchitsu for helpful discussions, Dr. Hiroshi Nyunoya for encouragement, and Ms. Yumiko Higashi for secretarial assistance.

References

- Asemaneh T, Ghaderian SM, Baker AJM. (2007) Responses to Mg/Ca balance in an Iranian serpentine endemic plant, Cleome heratensis (Capparaceae) and a related non-serpentine species, C. foliolosa. Plant Soil 293: 49–59 [Google Scholar]

- Bechtold N, Ellis J, Pelletier G. (1993) In planta Agrobacterium mediated gene transfer by infiltration of adult Arabidopsis thaliana plants. CR Acad Sci III, Sci Vie 316: 1194–1199 [Google Scholar]

- Bechtold N, Pelletier G. (1998) In planta Agrobacterium-mediated transformation of adult Arabidopsis thaliana plants by vacuum infiltration. Methods Mol Biol 82: 259–266 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benfey PN, Linstead PJ, Roberts K, Schiefelbein JW, Hauser MT, Aeschbacher RA. (1993) Root development in Arabidopsis: four mutants with dramatically altered root morphogenesis. Development 119: 57–70 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Braam J. (2004) In touch: plant responses to mechanical stimuli. New Phytol 165: 373–389 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bradshaw HD., Jr (2005) Mutations in CAX1 produce phenotypes characteristic of plants tolerant to serpentine soils. New Phytol 167: 81–88 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brady KU, Kruckeberg AR, Bradshaw HD., Jr (2005) Evolutionary ecology of plant adaptation to serpentine soils. Annu Rev Ecol Evol Syst 36: 243–266 [Google Scholar]

- Cholewa E, Peterson CA. (2004) Evidence for symplastic involvement in the radial movement of calcium in onion roots. Plant Physiol 134: 1793–1802 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cutler SR, Ehrhardt DW, Griffitts JS, Somerville CR. (2000) Random GFP:cDNA fusions enable visualization of subcellular structures in cells of Arabidopsis at a high frequency. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 97: 3718–3723 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Darwin C. (1880) The Power of Movement in Plants. John Murray, London [Google Scholar]

- Demidchik V, Bowen HC, Maathuis FJM, Shabala SN, Tester MA, White PJ, Davies JM. (2002) Arabidopsis thaliana root non-selective cation channels mediate calcium uptake and are involved in growth. Plant J 32: 799–808 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Desfeux C, Clough SJ, Bent AF. (2000) Female reproductive tissues are the primary target of Agrobacterium-mediated transformation by the Arabidopsis floral-dip method. Plant Physiol 123: 895–904 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dutta R, Robinson KR. (2004) Identification and characterization of stretch-activated ion channels in pollen protoplasts. Plant Physiol 135: 1398–1406 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fasano JM, Massa GD, Gilroy S. (2002) Ionic signaling in plant responses to gravity and touch. J Plant Growth Regul 21: 71–88 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galaviz-Hernandez C, Stagg C, de Ridder G, Tanaka TS, Ko MS, Schlessinger D, Nagaraja R. (2003) Plac8 and Plac9, novel placental-enriched genes identified through microarray analysis. Gene 309: 81–89 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gietz RD, Sugino A. (1988) New yeast-Escherichia coli shuttle vectors constructed with in vitro mutagenized yeast genes lacking six-base pair restriction sites. Gene 74: 527–534 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hashimoto K, Saito M, Matsuoka H, Iida K, Iida H. (2004) Functional analysis of a rice putative voltage-dependent Ca2+ channel, OsTPC1, expressed in yeast cells lacking its homologous gene CCH1. Plant Cell Physiol 45: 496–500 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haswell ES, Peyronnet R, Barbier-Brygoo H, Meyerowitz EM, Frachisse JM. (2008) Two MscS homologs provide mechanosensitive channel activities in the Arabidopsis root. Curr Biol 18: 730–734 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayter ML, Peterson CA. (2004) Can Ca2+ fluxes to the root xylem be sustained by Ca2+-ATPase in exodermal and endodermal plasma membrane?. Plant Physiol 136: 4318–4325 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hellens RP, Edwards EA, Leyland NR, Bean S, Mullineaux PM. (2000) pGreen: a versatile and flexible binary Ti vector for Agrobacterium-mediated plant transformation. Plant Mol Biol 42: 819–832 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirschi KD. (2004) The calcium conundrum. Both versatile nutrient and specific signal. Plant Physiol 136: 2438–2442 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang JW, Grunes DL, Kochian LV. (1993) Aluminum effects on calcium (45Ca2+ translocation in aluminum-tolerant and aluminum-sensitive wheat (Triticum aestivum L.) cultivars: differential responses of the root apex verus mature root regions. Plant Physiol 102: 85–93 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iida H, Nakamura H, Ono T, Okumura MS, Anraku Y. (1994) MID1, a novel Saccharomyces cerevisiae gene encoding a plasma membrane protein, is required for Ca2+ influx and mating. Mol Cell Biol 14: 8259–8271 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iida H, Yagawa Y, Anraku Y. (1990) Essential role for induced Ca2+ influx followed by [Ca2+]i rise in maintaining viability of yeast cells late in the mating pheromone response pathway. A study of [Ca2+]i in single Saccharomyces cerevisiae cells with imaging of fura-2. J Biol Chem 265: 13391–13399 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iida K, Tada T, Iida H. (2004) Molecular cloning in yeast by in vivo homologous recombination of the putative α 1 subunit of the voltage-gated calcium channel. FEBS Lett 576: 291–296 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iida K, Teng J, Tada T, Saka A, Tamai M, Izumi-Nakaseko H, Adachi-Akahane S, Iida H. (2007) Essential, completely conserved glycine residue in the domain III S2-S3 linker of voltage-gated calcium channel α 1 subunits in yeast and mammals. J Biol Chem 282: 25659–25667 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ishikawa H, Evans ML. (1992) Induction of curvature in maize roots by calcium or by thigmostimulation. Plant Physiol 100: 762–768 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones RGW, Lunt OR. (1967) The function of calcium in plants. Bot Rev 33: 407–426 [Google Scholar]

- Kanzaki M, Nagasawa M, Kojima I, Sato C, Naruse K, Sokabe M, Iida H. (1999) Molecular identification of a eukaryotic, stretch-activated nonselective cation channel. Science 285: 882–886 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kiegle E, Moore CA, Haseloff J, Tester MA, Knight MR. (2000) Cell-type-specific calcium responses to drought, salt and cold in the Arabidopsis root. Plant J 23: 267–278 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Legué V, Blancaflor E, Wymer C, Perbal G, Fantin D, Gilroy S. (1997) Cytosolic free Ca2+ in Arabidopsis roots changes in response to touch but not gravity. Plant Physiol 114: 789–800 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Massa GD, Gilroy S. (2003) Touch modulates gravity sensing to regulate the growth of primary roots of Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant J 33: 435–445 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mitsuhara I, Ugaki M, Hirochika H, Ohshima M, Murakami T, Gotoh Y, Katayose Y, Nakamura S, Honkura R, Nishimiya S, et al. (1996) Efficient promoter cassettes for enhanced expression of foreign genes in dicotyledonous and monocotyledonous plants. Plant Cell Physiol 37: 49–59 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miyama M, Tada Y. (2008) Transcriptional and physiological study of the response of Burma mangrove (Bruguiera gymnorhiza) to salt and osmotic stress. Plant Mol Biol 68: 119–129 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mount RC, Jordan BE, Hadfield C. (1996) Transformation of lithium-treated yeast cells and the selection of auxotrophic and dominant markers. Evans IH, , Yeast Protocols: Methods in Cell and Molecular Biology. Humana Press, Totowa, NJ, pp 139–145 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muller EM, Locke EG, Cunningham KW. (2001) Differential regulation of two Ca2+ influx systems by pheromone signaling in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Genetics 159: 1527–1538 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murashige T, Skoog F. (1962) A revised medium for rapid growth and bioassays with tobacco tissue cultures. Physiol Plant 15: 473–497 [Google Scholar]

- Nakagawa Y, Katagiri T, Shinozaki K, Qi Z, Tatsumi H, Furuichi T, Kishigami A, Sokabe M, Kojima I, Sato S, et al. (2007) Arabidopsis plasma membrane protein crucial for Ca2+ influx and touch sensing in roots. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 104: 3639–3644 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qi Z, Kishigami A, Nakagawa Y, Iida H, Sokabe M. (2004) A mechanosensitive anion channel in Arabidopsis thaliana mesophyll cells. Plant Cell Physiol 45: 1704–1708 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanders D, Pelloux J, Brownlee C, Harper JF. (2002) Calcium at the crossroads of signaling. Plant Cell 14: S401–S417 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tada T, Ohmori M, Iida H. (2003) Molecular dissection of the hydrophobic segments H3 and H4 of the yeast Ca2+ channel component Mid1. J Biol Chem 278: 9647–9654 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Telewski FW. (2006) A unified hypothesis of mechanoperception in plants. Am J Bot 93: 1466–1476 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Valvekens D, Montagu MV, Lijsebettens MV. (1988) Agrobacterium tumefaciens-mediated transformation of Arabidopsis thaliana root explants by using kanamycin selection. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 85: 5536–5540 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Véry AA, Sentenac H. (2002) Cation channels in the Arabidopsis plasma membrane. Trends Plant Sci 7: 168–175 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- White PJ. (2001) The pathway of calcium movement to the xylem. J Exp Bot 52: 891–899 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- White PJ, Bowen HC, Demidchik V, Nichols C, Davies JM. (2002) Genes for calcium-permeable channels in the plasma membrane of plant root cells. Biochim Biophys Acta 1564: 299–309 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- White PJ, Broadley MR. (2003) Calcium in plants. Ann Bot (Lond) 92: 487–511 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yermiyahu U, Nir S, Ben-Hayyim G, Kafkafi U. (1994) Quantitative competition of calcium with sodium or magnesium for sorption sites on plasma membrane vesicles of melon (Cucumis melo L.) root cells. J Membr Biol 138: 55–63 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]