Abstract

Liver metastases respond poorly to current therapy and remain a frequent cause of cancer-related mortality. We reported previously that tumor cells expressing a soluble form of the insulin-like growth factor-I receptor (sIGFIR) lost the ability to metastasize to the liver. Here, we sought to develop a novel therapeutic approach for prevention of hepatic metastasis based on sustained in vivo delivery of the soluble receptor by genetically engineered autologous bone marrow stromal cells. We found that when implanted into mice, these cells secreted high plasma levels of sIGFIR and inhibited experimental hepatic metastases of colon and lung carcinoma cells. In hepatic micrometastases, a reduction in intralesional angiogenesis and increased tumor cell apoptosis were observed. The results show that the soluble receptor acted as a decoy to abort insulin-like growth factor-I receptor (IGF-IR) functions during the early stages of metastasis and identify sustained sIGFIR delivery by cell-based vehicles as a potential approach for prevention of hepatic metastasis.

Introduction

The ability of cancer cells to metastasize remains the greatest challenge to the management of malignant disease. The liver is a major site of metastasis for some of the most prevalent human malignancies, particularly carcinomas of the gastrointestinal tract. At present, surgical resection is the only curative option for liver metastases but its success rate is partial, producing a 25–30% 5-year survival rate for cancers such as colorectal carcinoma.1 There is therefore a need for new therapeutic strategies that will improve cure rates for hepatic metastases.

The receptor for the type I insulin-like growth factor (IGF-IR) plays a critical role in malignant progression and has been identified as a determinant of the metastatic potential to several organ sites, particularly the lymph nodes and the liver.2,3,4,5,6,7,8 A recent study identified IGF-IR as a risk factor for liver metastasis in colorectal carcinoma patients.9 Clinical and experimental studies have collectively identified the IGF-IR as a target for anticancer therapy (reviewed in ref. 8) and several inhibitors including anti-IGF-IR antibodies and kinase inhibitors have advanced into clinical trials.7,8,10 As in the case of other receptor-targeted therapies (e.g., the epidermal growth factor receptor system), the clinical utility of IGF-IR inhibitors will ultimately be determined by parameters such as specificity, mechanism of target inhibition, pharmacokinetics, toxicity, bioavailability, and the ability of the targeted tumor cells to resist treatment through alternate survival pathway.11,12,13

The IGF-IR is synthesized as a polypeptide chain of 1,367 amino acids that is glycosylated and proteolytically cleaved into α- and β- subunits that dimerize to form a heterotetrameric receptor tyrosine kinase consisting of two 130–135 kda α- and two 90–95 kda β chains, with several α–α and α–β disulfide bridges.14 The ligand binding domain is on the extracellular α subunits. The β subunits consist each of an extracellular portion linked to the α subunit through disulfide bonds, a transmembrane domain and a cytoplasmic portion with a kinase domain and several critical tyrosines and serines involved in the transmission of ligand-induced signals.15,16,17 The IGF-IR ligands include three structurally homologous peptides, IGF-I and IGF-II and insulin, but the receptor binds IGF-I with the highest affinity.8,17 There is a high degree of homology between human and mouse IGF-I (97% overall homology) and IGF-IR (96% overall). Site directed mutagenesis used to map the IGF-I binding site identified seven amino acid residues critical for receptor binding that are fully conserved between the human and mouse IGF-I. There is also a 100% homology between the human and mouse ligand-binding domains of the receptors.17 This explains the ability of either ligand to stimulate the growth of mouse or human cells.18,19

An effective strategy for blocking the action of cellular receptor tyrosine kinases is the use of soluble variants that can bind ligand and reduce its bioavailability to the cognate receptor in a highly specific manner.20,21 This has recently been demonstrated with the VEGFR1/VEGFR2-Fc decoy receptor (the vascular endothelial growth factor [VEGF]-Trap) that is currently in clinical trials as an antiangiogenic, anticancer drug.22 The utility of decoy receptors for treatment of malignant disease can be optimized through the use of vehicles that can deliver therapeutically effective concentrations of the soluble receptor in a sustained manner into the tumor site. One promising strategy that is becoming a clinical reality is the utilization of autologous cells that have a regenerative capacity and can be genetically engineered to produce effective concentrations of the desired proteins.23,24 Bone marrow–derived mesenchymal stromal cells (MSCs)25 have been used to this end and have several advantages as delivery vehicles; they are abundant and available in humans of all age groups, can be harvested with minimal morbidity and discomfort, have a proliferative capacity, can be genetically engineered with reasonable efficiency, and are easy to reimplant in animal models without prior radiotherapy, chemotherapy, or immunosuppression (reviewed in refs. 26,27). MSCs have been validated as an efficient autologous cellular vehicle for the secretion of beneficial proteins in vivo28,29,30 and could become an effective tool for protein delivery in clinical practice, although the precise host conditioning that will be necessary to engraft these cells successfully in a clinical setting remains to be resolved (reviewed in refs. 27,31).

Previously, we reported that liver-metastasizing lung carcinoma cells genetically engineered to produce a 933-amino acid, soluble peptide spanning the entire extracellular domain of the IGF-IR (sIGFIR) lost all IGF-IR regulated functions and failed to produce liver metastases in a high proportion of mice, resulting in a markedly increased long term, disease-free survival.32 The objective of this study was to develop a strategy for sustained delivery of this decoy in vivo and test its efficacy as an antimetastatic agent in this setting.

Results

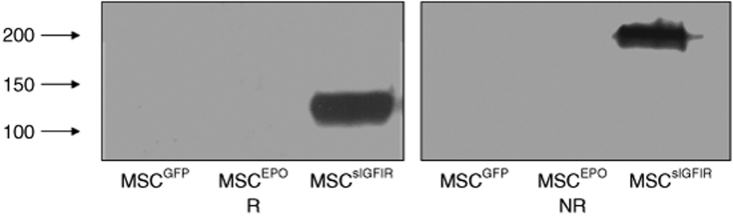

Genetically engineered autologous bone marrow stromal cells produce a soluble IGF-IR protein in vitro

To begin to evaluate the potential applications of a soluble IGF-IR decoy in a therapeutic setting, we genetically engineered autologous bone marrow stromal cells by transduction with retroviral particles expressing a complementary DNA fragment corresponding to the first 2,844 nucleotides of the human IGF-IR gene that encodes the sIGFIR peptide.32 This strategy was chosen with the objective of achieving a sustained in vivo production of the soluble peptide for the duration of the animal experiments. Western blotting performed with an antibody to the α subunit of the human IGF-IR revealed single bands corresponding to the α subunit (R, reducing conditions, Figure 1) or the truncated, soluble receptor tetramer (NR, nonreducing conditions; Figure 1) in serum-free conditioned medium harvested from these cells (MSCsIGFIR), but not from MSC transduced with control retroviral particles expressing either the green fluorescent protein (GFP) gene alone (MSCGFP) or a full-length erythropoietin complementary DNA (MSCEPO),33 (Figure 1), confirming that these cells expressed and secreted the decoy receptor in vitro, in a specific manner.

Figure 1.

Genetically engineered bone marrow stromal cells produce a soluble IGF-IR. MSCs were cultured in serum-free medium for 24 hours, the conditioned media harvested and concentrated 30-fold. The concentrated proteins were separated on a 6% SDS–polyacrylamide gel under reducing (R) or nonreducing (NR) conditions using 80 µg protein per lane. Proteins were detected with a rabbit antibody to the α subunit of human IGF-IR followed by a peroxidase-conjugated donkey anti-rabbit IgG. Shown are the results of a representative western blot of four performed. Numbers on the left denote the positions of MW markers. The positions of the bands correspond to the α subunit (R) and the truncated soluble tetramer (NR). IGF-IR, insulin-like growth factor-I receptor.

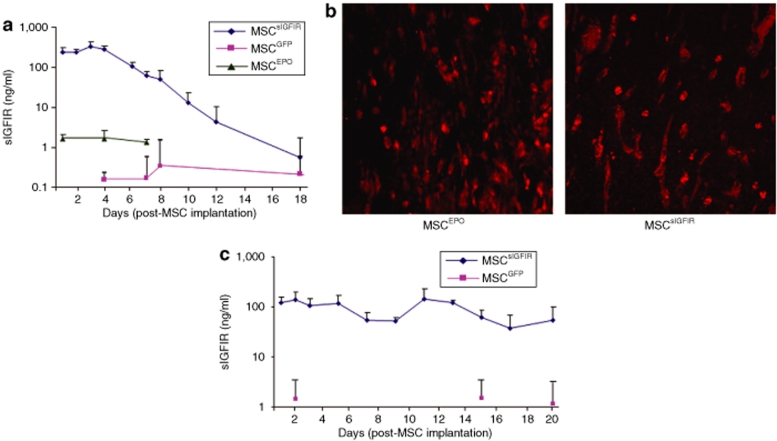

Genetically engineered autologous bone marrow stromal cells secrete plasma detectable levels of the soluble IGF-IR protein in vivo

To evaluate the ability of these cells to produce and secrete the soluble decoy in vivo, MSCsIGFIR and controls were embedded in a Matrigel matrix and implanted subcutaneously, as previously described.33 Blood samples were collected from the mice twice weekly and the plasma separated and analyzed for the presence of soluble hIGF-IR by the enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA). Within 24-hours postimplantation, soluble IGF-IR protein was detectable in the plasma of MSCsIGFIR-implanted mice while only low background levels of the peptide, similar to those seen in noninjected animals were detectable in plasma from MSCGFP or MSCEPO-implanted mice (Figure 2a). Plasma sIGFIR levels began to decline gradually 1 week after MSC implantation but remained significantly higher than control levels for at least 18 days (Figure 2a). Immunohistochemistry performed on sections of formalin fixed and paraffin-embedded Matrigel plugs that were removed from the mice 22 days postimplantation revealed the presence of GFP+ MSC in the Matrigel plugs (Figure 2b) and confirmed that these cells remained viable for this duration, as also observed previously.29 Interestingly, in athymic nude mice implanted with these cells, lower plasma levels of the soluble receptor ranging from 120 to 150 ng/ml were initially detected on days 1–3 postimplantation. However, protein production levels in these mice declined more slowly, remaining as high as 50 ng/ml on day 20 postimplantation (Figure 2c). These results confirmed the following: (i) the implanted MSC were able to secrete the decoy receptor in vivo, (ii) the protein could access the systemic circulation, and (iii) it remained at detectable levels for at least 3–4 weeks postimplantation. The results also suggested that host immunity may have been involved in regulating the level and duration of sIGFIR production by the stromal cells.

Figure 2.

Detection of circulating soluble IGF-IR in mice implanted with genetically engineered marrow stromal cells. Ten million MSCs were mixed with Matrigel and implanted subcutaneously into (a) syngeneic C57Bl/6 or (c) athymic mice. The mice were bled at several intervals postimplantation, the plasma separated and soluble IGF-IR levels measured using the ELISA. To avoid daily bleeding of the same mice, the animals were separated into groups that were bled twice weekly and the data for each time point pooled to generate the curve shown. Each value represents the mean (and SD) of a minimum of three (and up to 33) individual measurements performed on the indicated days. Blood samples collected from mice implanted with mock-transduced MSC (MSCGFP) or MSC producing erythropoietin (MSCEPO) were used as controls. Shown in b are representative confocal microscopy images taken of sections prepared from formalin fixed and paraffin-embedded Matrigel plugs containing the indicated cells that were removed 22 days following subcutaneous implantation. The sections were stained with a rabbit antibody to GFP followed by an Alexa Fluor 568 secondary antibody and imaged using confocal microscopy with a ×40 objective. ELISA, enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay; IGF-IR, insulin-like growth factor-I receptor.

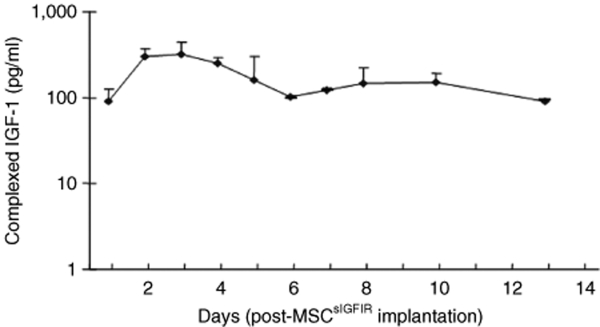

The soluble IGF-IR forms a complex with circulating mouse IGF-I

Decoy receptors can inhibit the biological activity of the cognate, membrane-bound receptors by binding ligand and decreasing its bioavailability.34 We evaluated therefore the presence of sIGFIR:IGF-I complexes in the circulation of MSCsIGFIR-implanted mice, using a combination ELISA. Complexes of the human sIGFIR and mouse IGF-I were detectable in the plasma as early as 24 hours post-MSCsIGFIR implantation. The level of sIGFIR-bound IGF-I increased for the first 3 days and then declined slowly, remaining at detectable levels for at least 2-weeks postimplantation (Figure 3) but no evidence of complex formation was seen in mice implanted with control MSC (data not shown). The total circulating IGF-I levels declined initially by up to 20% relative to controls (day 3) but recovered slowly returning to baseline levels by day 10 post-MSCsIGFIR implantation (Supplementary Figure S1). During this period, no overt deleterious effects of this treatment were evident, and blood analysis revealed no significant change in serum insulin or glucose levels in these mice as compared to controls (Supplementary Figure S2).

Figure 3.

The soluble IGF-IR forms a complex with circulating IGF-I. Plasma concentrations of sIGFIR-bound mouse IGF-I were semiquantified by ELISA. Pooled plasma samples obtained at each of the indicated time intervals were used for the analysis. Shown are the means (and SD) of values obtained from three different plasma pools, each derived from at least six mice. ELISA, enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay; IGF-IR, insulin-like growth factor-I receptor.

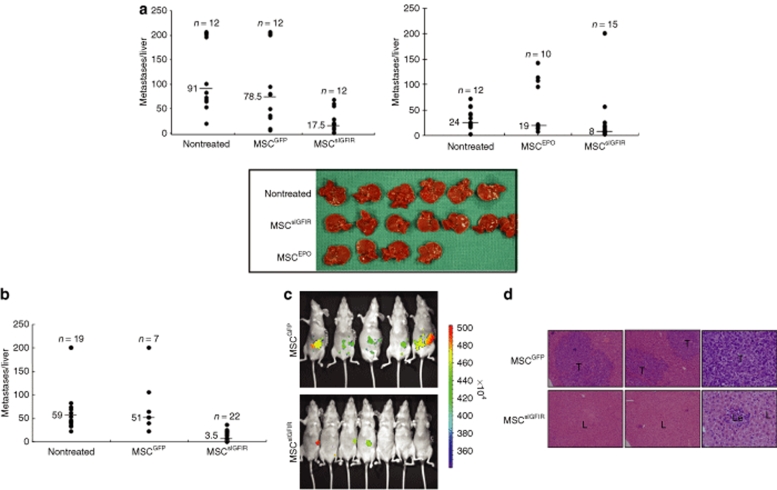

Bone marrow stromal cells secreting a soluble IGF-IR inhibit the development of experimental hepatic metastases

To analyze the effect of circulating sIGFIR and sIGFIR:IGF-I complexes on the ability of tumor cells to establish hepatic metastases, we first used the highly metastatic murine lung carcinoma H-59 cells. C57Bl/6 Mice were implanted with MSCsIGFIR or control MSC and injected 9–14 days later with 105 tumor cells via the intrasplenic/portal route to generate hepatic metastases. The time intervals between MSC implantation and tumor inoculation were selected based on a preliminary time-course analysis that revealed optimal effects during this period. In all mice implanted with MSCsIGFIR cells, we observed a marked reduction in the number of hepatic metastases. The results shown in Figure 4 demonstrate that in mice injected with H-59 cells 9 days following implantation of MSCsIGFIR cells, the median number of hepatic metastases declined by 78, 58, and 67–80%, respectively, relative to MSCGFP- and MSCEPO-implanted or untreated control mice, and this inhibitory effect was still apparent when tumor cells were inoculated 14 days post-MSC implantation, resulting in reductions of 93–95% in the median number of metastases, relative to control groups (Figure 4a,b). To compare the time-course of tumor development in mice implanted with MSCsIGFIR and control cells, we also implanted H-59 cells into athymic nude mice 9 days before the injection of GFP-tagged H-59 cells and tracked the appearance of a GFP signal in the liver using the Xenogen IVIS 200 system for noninvasive in vivo optical imaging. In all mice implanted with control MSC, a green fluorescence signal localized to the hepatic region could be detected by day 11 post-tumor injection. However, in mice implanted with MSCsIGFIR cells, evidence of hepatic tumors was first seen only on day 15 post-tumor inoculation (1/7 mice) and only 2/7 mice had a detectable GFP signal by day 18, when all the mice were killed (Figure 4c). Postmortem analysis confirmed that metastases in both groups were confined to the liver as no-extra-hepatic metastases were seen in either group. Analysis of hematoxylin and eosin stained paraffin sections derived from MSCsIGFIR-implanted mice did not reveal the presence of multiple micrometastases in these mice (Figure 4d) suggesting that tumor cells that were growth inhibited by this treatment did not persist in the liver as undetectable micrometastases.

Figure 4.

Bone marrow stromal cells producing a soluble IGF-IR inhibit experimental hepatic metastasis of H-59 cells. (a,b) Syngeneic female C57Bl/6 or (c,d) nude mice were implanted with 107 genetically engineered MSCsIGFIR or control MSC embedded in Matrigel. (a) Nine or (b) 14-days later, the mice were inoculated via the intrasplenic/portal route with 105 H-59 cells. Mice were euthanized and liver metastases enumerated 14 days post-tumor injection. Shown are the pooled data of (a-left) two and (a-right) three experiments, each performed using a different control MSC population, as shown. Representative livers from one of the experiments included in the right panel are shown (a-bottom panel). Shown in b are the pooled results of three experiments in which H-59 cells were injected 14 days post-MSC implantation and the mice euthanized 14–16 days later. Results of in vivo imaging performed with the IVIS 100 Xenogen system on day 15 post-tumor inoculation into nude mice are shown in c and representative hematoxylin and eosin stained sections obtained from formalin fixed and paraffin-embedded livers of these mice 18 days post-tumor inoculation and acquired with a ×4 (left and center panels) or ×40 (right panels) objective are shown in d. The P values as determined by the nonparametric Mann–Whitney test were (a-left) P < 0.001, (a-right) P < 0.005, and (b) P < 0.001 when MSCsIGFIR-treated mice were compared to each control group. L, liver; Le, leukocytes; T, tumor. IGF-IR, insulin-like growth factor-I receptor.

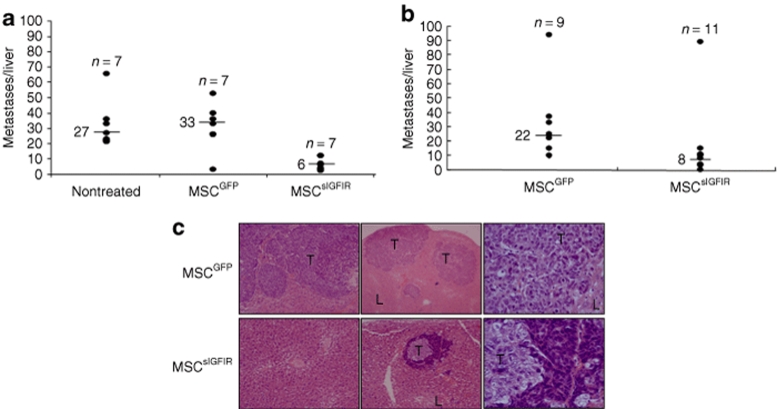

A similar inhibitory effect of MSCsIGFIR cells was seen following injection of 5 × 104 mouse colon carcinoma MC-38 (Figure 5a) or 2 × 105 human colon carcinoma KM12SM (Figure 5b,c) cells into syngeneic C57BL/6 and nude mice, respectively. These colon carcinoma lines were selected because they are highly and reproducibly metastatic to the liver. IGF-I dependency for liver metastasis was previously documented for colorectal carcinoma MC-38 cells35 and results of a preliminary reverse transcription-PCR analysis (data not shown) confirmed IGF-IR mRNA expression in KM12SM cells at levels comparable to those of H-59 and MC-38 cells. In MSCsIGFIR-implanted mice injected with these cells, the number of metastases declined by 78–82 (MC-38) and 64% (KM12SM) relative to the indicated control groups. There was no significant difference between the number of metastases that developed in MSCGFP (mock-treated) and nontreated mice in any of the experiments (Figures 4 and 5), suggesting that the implantation of MSC per se, did not have a deleterious (or stimulatory) effect on the development of hepatic metastases.

Figure 5.

Bone marrow stromal cells producing a soluble IGF-IR inhibit colon carcinoma metastasis. (a) Mice were inoculated with 5 × 104 MC-38 or (b) 106 KM12SM 14 days post-MSC implantation. Mice were euthanized and liver metastases enumerated (a) 18 or (b) 21 days post-tumor injection. Shown are the results of individual experiments using the indicated numbers of mice per group. Representative images of hematoxylin and eosin stained sections obtained from formalin fixed and paraffin embedded livers of KM12SM-injected nude mice (experiment depicted in b) using ×4 (left and center panels) or ×40 (right panels) objectives are shown in c. The P values were (a) P < 0.001 and (b) P < 0.01 when MSCSigfir-treated mice were compared to each of the control groups. L, liver; T, tumor. IGF-IR, insulin-like growth factor-I receptor.

Reduced angiogenesis and increased tumor-associated apoptosis during the early stages of liver colonization in mice producing a soluble IGF-IR

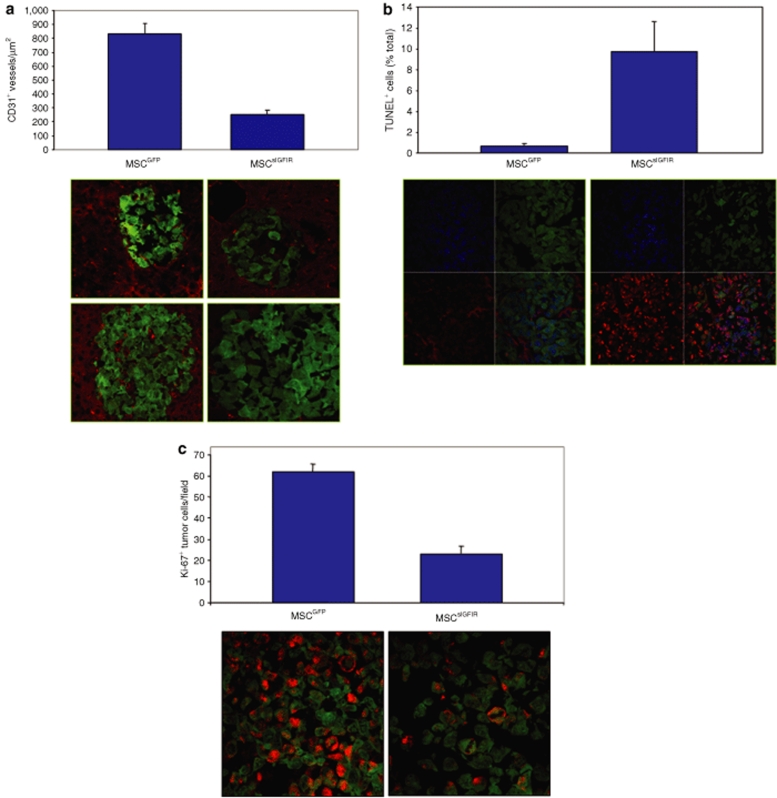

The IGF-IR is a survival factor and has also been implicated in tumor-induced angiogenesis through various mechanisms including the regulation of hypoxia-inducible factor HIF-1α and VEGF synthesis (reviewed extensively in ref. 8). Our in vivo imaging suggested that tumor growth in MSCsIGFIR-implanted mice, where it occurred, was significantly delayed and we therefore investigated the underlying mechanisms by comparing tumor-induced angiogenesis in treated and control mice, 6-days postinoculation of GFP+ H-59 cells. Cryostat sections of livers removed from tumor-inoculated mice were immunostained with an antibody to the endothelial marker CD31 and an Alexa Fluor 586 secondary antibody (for red signal); images were captured using a confocal microscope and microvessel density determined with the aid of an image analysis software. Results in Figure 6a show that the number of tumor-associated vessels declined by more than threefold in mice producing the soluble receptor relative to controls. In these mice, but not in control animals, micrometastases devoid of vascular structures were observed at this time (Figure 6a). Moreover, a terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase–mediated dUTP nick end–labeling assay revealed that the number of apoptotic tumor cells within these hepatic lesions increased 16-fold in sIGFIR producing, as compared to control mice (Figure 6b) and correspondingly, the number of proliferating cells, as revealed by staining with an anti-Ki67 antibody declined by 63% (Figure 6c). Taken together, these findings suggest that the soluble receptor could affect the growth of hepatic metastases, not only by a direct effect on the tumor cells, but also by reducing neovascularization leading to enhanced tumor cell death during the early stages of hepatic colonization.

Figure 6.

Reduced angiogenesis, increased apoptosis and decreased proliferation in micrometastases of mice implanted with MSCsIGFIR. Mice were implanted with MSC as described in the legend to Figure 4 and 105 GFP-tagged H-59 cells were injected 14 days later. Livers were obtained on day 6 post-tumor cell inoculation and processed for immunohistochemistry as described in Materials and Methods. Microvessels within micro-metastases were detected using a rat anti-CD31 antibody followed by an Alexa Fluor 568 goat anti-rat IgG. A total of six sections derived from three different livers were analyzed per group and five randomly selected fields were analyzed per section (for a total of 30 fields). CD31+ microvessels were counted, and the number of vessels per µm determined with the aid of the Zeiss LSM Image Browser software. Shown in a are means (and SE of the means) based on 30 individual images analyzed (top, P < 0.0001-two-tailed t-test) and two representative images/group acquired with a ×40 objective (bottom). Results of a TUNEL assay performed on sections derived from the same livers are shown in b. Following the TUNEL assay (as described in Materials and Methods), nuclei were DAPI stained and the numbers of TUNEL+ cells per total nuclei in each field were calculated using images acquired with a ×63 objective. Shown are means (and SE) of the proportions of TUNEL+ nuclei per total nuclei seen in 12 individual images (top, P = 0.0040, two-tailed t-test) and representative images showing GFP+ tumor cells (green), total nuclei (blue), and apoptotic cells (red) and the merged images for each group acquired with a ×63 objective (bottom). Proliferating cells within the micrometastases were detected using an antibody to Ki67. A total of six sections derived from three different livers were analyzed per group and two randomly selected fields were analyzed per section (for a total of 12 fields). Images for each of the 12 fields were acquired with a ×63 objective, the numbers of Ki67+ cells (red) and total GFP+ tumor cells per field were recorded and the percentages of Ki67 positive cells in each field were calculated. Shown in c are the mean proportions of Ki67+ cells recorded in 12 individual images (top, P = 0.0074, two-tailed t-test) and representative merged images of green and red fluorescence acquired with a ×63 objective (bottom). DAPI, 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole; TUNEL, terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase–mediated dUTP nick end–labeling.

Discussion

MSCs are gaining acceptance as a therapeutic reagent, both as a source of pluripotent cells for tissue regeneration and cell replacement therapy and as a vehicle for in vivo delivery of therapeutic proteins.26,27,33,36 In recent years, progress has also been made in their adaptation and utilization for the delivery of anticancer drugs.27 Here, we used autologous bone marrow stromal cells to genetically engineer an implantable “reservoir” of a novel, secretable IGF-IR decoy for the purpose of blocking the growth of hepatic metastases. We show that the stromal cells survived within the implanted Matrigel matrix for several weeks and that during this period, therapeutically effective concentrations of the decoy were secreted into the circulation, resulting in marked reductions in the ability of three different highly metastatic tumor cell types to colonize the liver. We show that the failure to establish metastases was due to increased tumor apoptosis and reduced proliferation during the early stages of metastasis which could have resulted, at least in part, from a marked reduction in tumor-induced neovascularization. These effects were highly specific and were not observed in mice implanted with MSC expressing GFP or secreting erythropoietin.29

Of note is our observation that while plasma sIGFIR levels declined progressively in immunocompetent mice, they were more stable in athymic mice, remaining relatively high for the duration of the experiments. This suggests that the host immune response may have contributed to a more rapid elimination of the implanted cells in immunocompetent mice. This immune reactivity was likely directed at the GFP transgene because the MSC used in this study were syngeneic to the injected mice and MSCs are relatively nonimmunogenic.27,31 This is also supported by our observation (data not shown) that in GFP-transgenic mice,37 plasma levels of sIGFIR were similar to those observed in athymic mice and remained stable for at least 18 days post-MSCsIGFIR implantation. Taken together, these data suggest that the expression of the GFP reporter may have limited the in vivo longevity of the implanted MSC, as was also noted by others,38 and that the efficacy of MSC-based treatment may be further improved with the use of nontagged MSC, as is likely to be the case in the clinical setting. It is also noteworthy that no antibodies to IGF-IR were detectable by ELISA or western blotting in pooled sera from MSCsIGFIR-implanted mice (data not shown). This suggests that a humoral immune response to the soluble receptor itself was probably not contributing to host reactivity against the implanted stromal cells or to the antitumorigenic effect we observed.

We found that in MSCsIGFIR-implanted mice, circulating IGF-I levels initially declined by ~20% relative to controls, but returned to baseline levels within 10 days. Changes in serum IGF-I levels coincided with the appearance of sIGFIR:IGF-I complexes that were detectable only in these mice. Circulating decoy receptor:ligand complexes were also reported in mice injected repeatedly with a VEGF-Trap. In that study, complex formation was found to be indicative of therapeutic efficacy.34 Our results show that the soluble receptor secreted by the stromal cells was able to bind circulating ligand and suggest that the presence of sIGFIR:IGF-I complexes in the circulation may be more pertinent and a better indicator of a potential antitumorigenic effect than the total (bound and unbound) plasma concentrations of the ligand, before or during tumor growth.34 These results also suggest that in the clinical setting, a sustained delivery of the decoy receptor through a vehicle such as autologous bone marrow cells could offer an effective alternative to repeated administration of the purified protein.

Ligand-induced IGF-IR activation leads to transmission of prosurvival signals via PI-3K/Akt signaling and increased VEGF synthesis.8 We reported that tumor H-59 cells that produced the sIGFIR molecule lost IGF-I-induced signaling in vitro and as a result, VEGF-A and VEGF-C induction were blocked.32 Here, we observed that in MSCsIGFIR-implanted mice, some multicellular hepatic colonies that did not differ in size from those in control mice did initially form (as was seen on day 3, data not shown). However by day 6, as intratumoral neovascularization became evident in control mice, significantly less microvessels could be seen in hepatic colonies in the treatment group and, in parallel, there was a marked increase in the number of apoptotic, and a decrease in proliferating tumor cells in these micrometastases. This suggests that the reduction in the number of visible metastases in these mice was due not only to the loss of IGF-IR-mediated survival signals in cells entering the liver, but also to inhibition of tumor-induced angiogenesis, most likely through the suppression of VEGF production. This antiangiogenic effect may therefore have provided an additional inhibitory mechanism for tumor cells that initially escaped the direct growth inhibitory effects of circulating sIGFIR. Taken together, this suggests that in mice with MSC-derived circulating sIGFIR, the bioavailability of IGF-I in the immediate tumor microenvironment was reduced, mimicking the autocrine effects of tumor cell-produced sIGFIR.32 Of note also is our observation that serum insulin and glucose levels in the treated mice were not measurably different than those in the control group, suggesting that nonspecific effects on glucose metabolism in these mice did not play a role in the observed reduction in liver metastasis.

We also observed that the antimetastatic effect of the soluble receptor did not decline but rather increased with time (up to 14 days) following MSC implantation. This suggests that in addition to the direct effects on tumor cell growth, the sustained presence of sIGFIR:IGF-I complexes may also have impacted other, host-dependent factors that normally contribute to the formation of hepatic metastases such as the stromal and inflammatory reactions. Previously we have shown that tumor cells invading the liver initiate a host inflammatory response that promotes tumor cell arrest, intravasation, and metastasis.39,40,41 The IGF axis plays a role in host inflammation and immunity and can modulate cytokine signaling via several mechanisms including JAK/STAT activation.8,42,43 Changes in IGF-I bioavailability could therefore potentially have indirect effects on liver metastases by altering the host inflammatory response to invading tumor cells.

We have shown here that the IGF-IR decoy can prevent the growth of experimental metastases from three different carcinoma cell types. This is consistent with other reports including our own, that have identified IGF-I as a critical factor for liver metastasis8,10,19,35 and suggests that liver metastasizing malignancies may be particularly susceptible to therapeutic modalities that target the IGF axis, possibly due to the high IGF-I content in the liver.6,8,44 The present results identify the soluble IGF-IR as an effective and specific antimetastatic agent and provide a rationale for its further development for clinical use.

Materials and Methods

Cells. The origin, metastatic phenotype, and culture conditions of H-59—a subline of the Lewis lung carcinoma—were previously described.45 Murine MC-38 colon adenocarcinoma cells46 and human colorectal carcinoma KM12SM cells (a kind gift from I.J. Fidler, M.D. Anderson Cancer Institute, Houston, TX) were maintained as described elsewhere.46,47 Mouse bone marrow stromal cells were phenotyped and characterized as has been described in detail previously.48 These cells and GP2-293 cells (ClonTech, Mountain View, CA) were maintained in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (Invitrogen Canada, Burlington, Canada) with 10% fetal calf serum (Invitrogen Canada). All the cells were used within 2–4 weeks of cell recovery from frozen stocks.

Retroviral transduction of MSC. The construction of the pLTR-GFP-IGIR933 vector expressing a complementary DNA fragment corresponding to the first 2,844 nucleotides of the human IGF-IR RNA was described in detail previously.32 To produce retrovirus particles expressing sIGFIR, the GP2-293 cells (ClonTech) were cotransfected with 5 µg of the pLTR-IGIR933 vector that also encodes the GFP and 5 µg of pVSV-G (ClonTech) using lipofectamine (Invitrogen, Burlington, Canada), as per the manufacturer's instructions. After a 48–72 hours incubation, the medium was harvested, filtered, and added to semiconfluent MSC cultures in 60-mm culture dishes together with 4–8 µg/ml polybrene (Sigma-Aldrich, St Louis, MO). This transduction protocol was repeated several times until sIGFIR could be detected in the culture medium by western blotting. MSC transduced in the same manner with retroviral particles expressing the GFP complementary DNA only (MSCGFP) and, in some experiments, MSC engineered to produce erythropoietin (MSCEPO), as described elsewhere,29 were used as controls. Both MSCsIGFIR and MSCGFP cells were sorted using a FACSCalibur (Becton-Dickinson, Mississauga, Canada) to produce a GFP-enriched subpopulation in which >95% cells were highly fluorescent, as assessed by flow cytometry and these cells were used for all subsequent in vivo experiments.

Western blot assay. Serum-free conditioned medium of the transduced MSC were concentrated 30-fold and the proteins loaded on a 6% polyacrylamide gel and separated by electrophoresis under nonreducing or reducing conditions. Immunoblotting was performed as we described previously32 using a rabbit polyclonal antibody to human IGF-IR (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA) diluted 1:200 and peroxidase-conjugated donkey anti-rabbit IgG (Cedarlane, Hornby, Canada) diluted 1:10,000. Protein bands were visualized using the enhanced chemiluminescence system (Roche, Basel, Switzerland).

ELISA. Plasma concentrations of sIGFIR were quantified using the human IGF-IR DuoSet ELISA Development Systems (R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN). The presence of circulating sIGFIR:IGF-I complexes was assessed and their plasma concentrations semiquantified by a combination ELISA using the mouse anti-IGF-IR antibody (R&D Systems) to coat a 96-well plate and capture the sIGFIR portion of the complexes and a biotinylated goat anti-mouse IGF-I antibody (R&D Systems) to detect sIGFIR-bound IGF-I. Bound IGF-I concentrations were calculated using a standard curve based on the use of the mouse IGF-I DuoSet ELISA Development Systems (R&D Systems), as per the manufacturer's instruction. In all the experiments, plasma obtained from control, untreated mice were used to establish baselines. In addition, MSCsIGFIR and MSCGFP conditioned media were used as positive and negative controls, respectively.

Radioimmunoassay and glucose measurements. Plasma IGF-I concentrations were measured by radioimmunoassay using a polyclonal human anti-IGF-I antibody with no cross-reactivity to IGF-II that has previously been validated in mice, as described in detail elsewhere.49 Known standards were placed in each run, and pooled mouse sera from 16-week-old C57Bl/6 mice were used as a second control for interassay variations. Serum insulin levels were determined using a commercial radioimmunoassay kit (Linco Research, St Charles, MO), as previously described and blood glucose was measured using a Glucometer Elite (Bayer, Elkhart, IN).50

Subcutaneous implantation of MSC. All animal experiments were conducted in accordance with the guidelines of the McGill University Animal Care committee. To initiate sustained in vivo production of sIGFIR, MSCsIGFIR (and MSCGFP as a control) were dispersed with a 0.2% trypsin–EDTA solution, centrifuged, and resuspended in RPMI medium. For each injection, 107 cells in 50 µl RPMI were mixed with 450 µl undiluted Matrigel (Becton-Dickinson) and the entire volume implanted by subcutaneous injection into the right flank, as described elsewhere.33 At body temperature, the Matrigel implant rapidly acquired a semisolid form and it remained in the animals for the duration of the experiments. To monitor circulating sIGFIR levels, blood samples were collected from the saphenous vein using heparinized microhematocrit tubes, and the plasma separated and tested by ELISA.

Experimental metastasis assay. Experimental liver metastases were generated by the injection of 5 × 104 (MC-38), 105 (H-59), or 106 (KM12SM) tumor cells via the intrasplenic/portal route,32 9–14 days following the implantation of the MSC in Matrigel. The number of tumor cells to be injected was determined based on preliminary dose–response analyses and selected to produce a quantifiable number of hepatic metastases within 14–21 days post-tumor inoculation, at which time the animals were killed. Visible metastases on the surfaces of the livers were enumerated immediately after their removal and before fixation with the aid of a stereomicroscope, as we have previously described.32 Some of the livers were fixed in 10% phosphate buffered formalin, paraffin-embedded, and 4-µm paraffin sections cut and stained with hematoxylin and eosin to visualize micrometastases. For some experiments, mice were inoculated with GFP-tagged H-59 cells and the development of hepatic metastases was monitored using live imaging.

In vivo optical imaging. Live optical imaging of fluorescent cells was performed at the McGill University Bone Center using the IVIS 13198, SI620EEV camera mounted in a light-tight specimen box (IVIS 100; Xenogen/Caliper Life Sciences, Hopkinton, MA) and the Living Image Version 2.50 analysis software (Caliper Life Sciences) was used for acquisition and quantification of signals. The mice were anesthetized, placed onto a warmed stage inside the light-tight box, and images captured for 5–10 seconds at medium or high binning, depending on the time interval following tumor inoculation. The fluorophore excitation and emission filter sets used were λexcitation = 445–490 nm and λemission = 515–575 nm. The fluorescence images shown are real-time unprocessed images. Fluorescent signals within the liver region were normalized to the background fluorescence taken over the same region from noninjected animals.

Detection of GFP+ MSC by immunohistochemistry. Sections (5 µm) were obtained from formalin fixed and paraffin-embedded Matrigel plugs implanted subcutaneously with MSCGFP or MSCsIGFIR cells. The sections were deparaffinized and immunostained with a rabbit anti-GFP antibody and an Alexa Fluor 568 goat anti-rabbit IgG (both from Molecular Probes, Invitrogen Canada), both used at a dilution of 1:200. Images were obtained using a Zeiss LSM 510 Meta confocal imaging station and the Zeiss LSM Image Browser (Carl Zeiss Canada, Toronto, Canada).

Terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase–mediated nick end–labeling assay. To measure the extent of apoptosis within micrometastatic lesions, the livers were removed and snap frozen 6 days postintrasplenic/portal injection of GFP-tagged H-59 cells and 8 µm cryostat sections prepared. Apoptotic cells were labeled by the terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase-mediated dUTP nick end-labeling assay, using the in situ cell death detection kit, TMR red (Roche Diagnostics, Laval, Quebec), according to the manufacturer's instructions. Nuclei were stained with 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole and the sections mounted with the ProLong Gold antifade reagent (Invitrogen), visualized with the LSM 510 Meta confocal microscope and images acquired and analyzed with the Zeiss LSM Image Browser program.

Microvessel density and Ki67 staining. To measure tumor-induced angiogenesis, the mice were inoculated with 105 tumor cells by the intrasplenic/portal route, killed 6 days later, and the livers perfused via the portal vein with a solution of 4% paraformaldehyde in phosphate-buffered saline, excised, and processed, as we previously described,32,39 before the preparation of 8 µm cryostat sections. To stain intralesional microvessels or proliferating tumor cells, the sections were incubated first in a blocking solution containing 0.1% bovine serum albumin, 5% goat serum, and 0.1% Triton X-100 in phosphate-buffered saline, and then with a rat anti-mouse CD31 antibody (BD Pharmingen, BD Biosciences, Mississauga, Canada) or a rabbit antibody to Ki67 (Abcam, Cambridge, MA), respectively, each used at a dilution of 1:200 for 18 hours at 4 °C. Sections were then incubated for 1 hour at room temperature with an Alexa Fluor 568 goat anti-rat or goat anti-rabbit IgG (Molecular Probes, Invitrogen), respectively, each used at a dilution of 1:200. The sections were mounted and analyzed as above. The number of CD31+ vessels/µm2 was determined with the aid of the Zeiss LSM Image Browser program. Sections immunostained with an anti-Ki67 antibody were counterstained with 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole as described32 and the proportion of proliferating cells was calculated.

Statistics. The nonparametric Mann–Whitney test was used to analyze all the metastasis data and the two-tailed Student t-test was used to analyze data from all other experiments.

SUPPLEMENTARY MATERIALFigure S1. Plasma levels of IGF-I were measured using an RIA.Figure S2. Serum insulin and glucose levels in the nonfasted state were measured between days 1 and 5 postimplantation of the indicated MSC.

Supplementary Material

Plasma levels of IGF-I were measured using an RIA.

Serum insulin and glucose levels in the nonfasted state were measured between days 1 and 5 postimplantation of the indicated MSC.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by grant MOP-77677 from the Canadian Institute for Health Research (P.B. and J.G.). Ni Wang was supported by a fellowship from the Cedars Foundation of the McGill University Health Center and Julia Burnier by a studentship from the McGill University Health Center Research Institute. We thank Peter Siegel and his staff for their help with in vivo optical imaging and Miguel Burnier and his staff for help with the histology.

REFERENCES

- Wei AC, Greig PD, Grant D, Taylor B, Langer B., and , Gallinger S. Survival after hepatic resection for colorectal metastases: a 10-year experience. Ann Surg Oncol. 2006;13:668–676. doi: 10.1245/ASO.2006.05.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Girnita A, All-Ericsson C, Economou MA, Aström K, Axelson M, Seregard S, et al. The insulin-like growth factor-I receptor inhibitor picropodophyllin causes tumor regression and attenuates mechanisms involved in invasion of uveal melanoma cells. Clin Cancer Res. 2006;12:1383–1391. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-05-1106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LeBedis C, Chen K, Fallavollita L, Boutros T., and , Brodt P. Peripheral lymph node stromal cells can promote growth and tumorigenicity of breast carcinoma cells through the release of IGF-I and EGF. Int J Cancer. 2002;100:2–8. doi: 10.1002/ijc.10481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Long L, Rubin R, Baserga R., and , Brodt P. Loss of the metastatic phenotype in murine carcinoma cells expressing an antisense RNA to the insulin-like growth factor receptor. Cancer Res. 1995;55:1006–1009. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Long L, Rubin R., and , Brodt P. Enhanced invasion and liver colonization by lung carcinoma cells overexpressing the type 1 insulin-like growth factor receptor. Exp Cell Res. 1998;238:116–121. doi: 10.1006/excr.1997.3814. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reinmuth N, Liu W, Fan F, Jung YD, Ahmad SA, Stoeltzing O, et al. Blockade of insulin-like growth factor I receptor function inhibits growth and angiogenesis of colon cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2002;8:3259–3269. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Donovan EA., and , Kummar S. Role of insulin-like growth factor-1R system in colorectal carcinogenesis. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol. 2008;66:91–98. doi: 10.1016/j.critrevonc.2007.09.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Samani AA, Yakar S, LeRoith D., and , Brodt P. The role of the IGF system in cancer growth and metastasis: overview and recent insights. Endocr Rev. 2007;28:20–47. doi: 10.1210/er.2006-0001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oshima T, Akaike M, Yoshihara K, Shiozawa M, Yamamoto N, Sato T, et al. Clinicopathological significance of the gene expression of matrix metalloproteinase-7, insulin-like growth factor-1, insulin-like growth factor-2 and insulin-like growth factor-1 receptor in patients with colorectal cancer: insulin-like growth factor-1 receptor gene expression is a useful predictor of liver metastasis from colorectal cancer. Oncol Rep. 2008;20:359–364. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sachdev D., and , Yee D. Disrupting insulin-like growth factor signaling as a potential cancer therapy. Mol Cancer Ther. 2007;6:1–12. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-06-0080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arora A., and , Scholar EM. Role of tyrosine kinase inhibitors in cancer therapy. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2005;315:971–979. doi: 10.1124/jpet.105.084145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jain RK, Duda DG, Clark JW., and , Loeffler JS. Lessons from phase III clinical trials on anti-VEGF therapy for cancer. Nat Clin Pract Oncol. 2006;3:24–40. doi: 10.1038/ncponc0403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weroha SJ., and , Haluska P. IGF-1 receptor inhibitors in clinical trials--early lessons. J Mammary Gland Biol Neoplasia. 2008;13:471–483. doi: 10.1007/s10911-008-9104-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ullrich A, Gray A, Tam AW, Yang-Feng T, Tsubokawa M, Collins C, et al. Insulin-like growth factor I receptor primary structure: comparison with insulin receptor suggests structural determinants that define functional specificity. EMBO J. 1986;5:2503–2512. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1986.tb04528.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garrett TP, McKern NM, Lou M, Frenkel MJ, Bentley JD, Lovrecz GO, et al. Crystal structure of the first three domains of the type-1 insulin-like growth factor receptor. Nature. 1998;394:395–399. doi: 10.1038/28668. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jansson M, Hallén D, Koho H, Andersson G, Berghard L, Heidrich J, et al. Characterization of ligand binding of a soluble human insulin-like growth factor I receptor variant suggests a ligand-induced conformational change. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:8189–8197. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.13.8189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Denley A, Cosgrove LJ, Booker GW, Wallace JC., and , Forbes BE. Molecular interactions of the IGF system. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev. 2005;16:421–439. doi: 10.1016/j.cytogfr.2005.04.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yakar S, Rosen CJ, Beamer WG, Ackert-Bicknell CL, Wu Y, Liu JL, et al. Circulating levels of IGF-1 directly regulate bone growth and density. J Clin Invest. 2002;110:771–781. doi: 10.1172/JCI15463. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bauer TW, Fan F, Liu W, Camp ER, Yang A, Somcio RJ, et al. Targeting of insulin-like growth factor-I receptor with a monoclonal antibody inhibits growth of hepatic metastases from human colon carcinoma in mice. Ann Surg Oncol. 2007;14:2838–2846. doi: 10.1245/s10434-007-9486-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Becker CM, Farnebo FA, Iordanescu I, Behonick DJ, Shih MC, Dunning P, et al. Gene therapy of prostate cancer with the soluble vascular endothelial growth factor receptor Flk1. Cancer Biol Ther. 2002;1:548–553. doi: 10.4161/cbt.1.5.176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trieu Y, Wen XY, Skinnider BF, Bray MR, Li Z, Claudio JO, et al. Soluble interleukin-13Ralpha2 decoy receptor inhibits Hodgkin's lymphoma growth in vitro and in vivo. Cancer Res. 2004;64:3271–3275. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.can-03-3764. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rudge JS, Thurston G, Davis S, Papadopoulos N, Gale N, Wiegand SJ, et al. VEGF trap as a novel antiangiogenic treatment currently in clinical trials for cancer and eye diseases, and VelociGene-based discovery of the next generation of angiogenesis targets. Cold Spring Harb Symp Quant Biol. 2005;70:411–418. doi: 10.1101/sqb.2005.70.052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buckley RH. Gene therapy for human SCID: dreams become reality. Nat Med. 2000;6:623–624. doi: 10.1038/76185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baksh D, Song L., and , Tuan RS. Adult mesenchymal stem cells: characterization, differentiation, and application in cell and gene therapy. J Cell Mol Med. 2004;8:301–316. doi: 10.1111/j.1582-4934.2004.tb00320.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horwitz EM, Le Blanc K, Dominici M, Mueller I, Slaper-Cortenbach I, Marini FC, et al. Clarification of the nomenclature for MSC: The International Society for Cellular Therapy position statement. Cytotherapy. 2005;7:393–395. doi: 10.1080/14653240500319234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horwitz EM. MSC: a coming of age in regenerative medicine. Cytotherapy. 2006;8:194–195. doi: 10.1080/14653240600758562. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumar S, Chanda D., and , Ponnazhagan S. Therapeutic potential of genetically modified mesenchymal stem cells. Gene Ther. 2008;15:711–715. doi: 10.1038/gt.2008.35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keating A, Guinn BA, Laraya P., and , Wang XH. Human marrow stromal cells electrotransfected with human FIX cDNA engraft in SCID mice and transcribe human Factor IX. Exp Hematol. 1996;24:1056. [Google Scholar]

- Eliopoulos N, Crosato M., and , Galipeau J. High-level erythropoietin production from genetically engineered bone marrow stroma implanted in non-myeloablated, immunocompetent mice. Blood. 2000;96:802a. [Google Scholar]

- Stagg J, Wu JH, Bouganim N., and , Galipeau J. Granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor and interleukin-2 fusion cDNA for cancer gene immunotherapy. Cancer Res. 2004;64:8795–8799. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-1776. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stagg J., and , Galipeau J. Immune plasticity of bone marrow-derived mesenchymal stromal cells. Handb Exp Pharmacol. 2007. pp. 45–66. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Samani AA, Chevet E, Fallavollita L, Galipeau J., and , Brodt P. Loss of tumorigenicity and metastatic potential in carcinoma cells expressing the extracellular domain of the type 1 insulin-like growth factor receptor. Cancer Res. 2004;64:3380–3385. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-03-3780. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eliopoulos N, Al-Khaldi A, Crosato M, Lachapelle K., and , Galipeau J. A neovascularized organoid derived from retrovirally engineered bone marrow stroma leads to prolonged in vivo systemic delivery of erythropoietin in nonmyeloablated, immunocompetent mice. Gene Ther. 2003;10:478–489. doi: 10.1038/sj.gt.3301919. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rudge JS, Holash J, Hylton D, Russell M, Jiang S, Leidich R, et al. Inaugural Article: VEGF Trap complex formation measures production rates of VEGF, providing a biomarker for predicting efficacious angiogenic blockade. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2007;104:18363–18370. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0708865104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu Y, Yakar S, Zhao L, Hennighausen L., and , LeRoith D. Circulating insulin-like growth factor-I levels regulate colon cancer growth and metastasis. Cancer Res. 2002;62:1030–1035. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horwitz EM, Gordon PL, Koo WK, Marx JC, Neel MD, McNall RY, et al. Isolated allogeneic bone marrow-derived mesenchymal cells engraft and stimulate growth in children with osteogenesis imperfecta: Implications for cell therapy of bone. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2002;99:8932–8937. doi: 10.1073/pnas.132252399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tuason MC, Rastikerdar A, Kuhlmann T, Goujet-Zalc C, Zalc B, Dib S, et al. Separate proteolipid protein/DM20 enhancers serve different lineages and stages of development. J Neurosci. 2008;28:6895–6903. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4579-07.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stripecke R, Carmen Villacres M, Skelton D, Satake N, Halene S., and , Kohn D. Immune response to green fluorescent protein: implications for gene therapy. Gene Ther. 1999;6:1305–1312. doi: 10.1038/sj.gt.3300951. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Auguste P, Fallavollita L, Wang N, Burnier J, Bikfalvi A., and , Brodt P. The host inflammatory response promotes liver metastasis by increasing tumor cell arrest and extravasation. Am J Pathol. 2007;170:1781–1792. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2007.060886. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khatib AM, Auguste P, Fallavollita L, Wang N, Samani A, Kontogiannea M, et al. Characterization of the host proinflammatory response to tumor cells during the initial stages of liver metastasis. Am J Pathol. 2005;167:749–759. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)62048-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khatib AM, Fallavollita L, Wancewicz EV, Monia BP., and , Brodt P. Inhibition of hepatic endothelial E-selectin expression by C-raf antisense oligonucleotides blocks colorectal carcinoma liver metastasis. Cancer Res. 2002;62:5393–5398. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelley KW, Weigent DA., and , Kooijman R. Protein hormones and immunity. Brain Behav Immun. 2007;21:384–392. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2006.11.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prueitt RL, Boersma BJ, Howe TM, Goodman JE, Thomas DD, Ying L, et al. Inflammation and IGF-I activate the Akt pathway in breast cancer. Int J Cancer. 2007;120:796–805. doi: 10.1002/ijc.22336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reinmuth N, Fan F, Liu W, Parikh AA, Stoeltzing O, Jung YD, et al. Impact of insulin-like growth factor receptor-I function on angiogenesis, growth, and metastasis of colon cancer. Lab Invest. 2002;82:1377–1389. doi: 10.1097/01.lab.0000032411.41603.c2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brodt P. Characterization of two highly metastatic variants of Lewis lung carcinoma with different organ specificities. Cancer Res. 1986;46:2442–2448. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yakar S, Nunez NP, Pennisi P, Brodt P, Sun H, Fallavollita L, et al. Increased tumor growth in mice with diet-induced obesity: impact of ovarian hormones. Endocrinology. 2006;147:5826–5834. doi: 10.1210/en.2006-0311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kitadai Y, Sasaki T, Kuwai T, Nakamura T, Bucana CD., and , Fidler IJ. Targeting the expression of platelet-derived growth factor receptor by reactive stroma inhibits growth and metastasis of human colon carcinoma. Am J Pathol. 2006;169:2054–2065. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2006.060653. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campeau PM, Rafei M, François M, Birman E, Forner KA., and , Galipeau J. Mesenchymal stromal cells engineered to express erythropoietin induce anti-erythropoietin antibodies and anemia in allorecipients. Mol Ther. 2009;17:369–372. doi: 10.1038/mt.2008.270. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yakar S, Bouxsein ML, Canalis E, Sun H, Glatt V, Gundberg C, et al. The ternary IGF complex influences postnatal bone acquisition and the skeletal response to intermittent parathyroid hormone. J Endocrinol. 2006;189:289–299. doi: 10.1677/joe.1.06657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pennisi P, Gavrilova O, Setser-Portas J, Jou W, Santopietro S, Clemmons D, et al. Recombinant human insulin-like growth factor-I treatment inhibits gluconeogenesis in a transgenic mouse model of type 2 diabetes mellitus. Endocrinology. 2006;147:2619–2630. doi: 10.1210/en.2005-1556. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Plasma levels of IGF-I were measured using an RIA.

Serum insulin and glucose levels in the nonfasted state were measured between days 1 and 5 postimplantation of the indicated MSC.