Abstract

Comprehensive dissection of protein functions entails more complicated manipulations than simply eliminating the protein of interest. Established knockdown technologies, such as RNA interference, antisense oligodeoxynucleotides, or ribozymes, are limited for specific applications such as modulating protein levels or specific targeting of a posttranslationally modified subpopulation. Here we show that the engineered Skp1, Cullin 1, and F-box-containing βTrCP substrate receptor ubiquitin-proteolytic system, designated protein knockout, could achieve not only total elimination but also rapid and systematic reduction of a given cellular protein. Stable expression of a single engineered βTrCP demonstrated simultaneous and sustained degradation of the entire retinoblastoma family proteins. Furthermore, the engineered βTrCP was capable of selecting hypo- but not hyperphosphorylated forms of retinoblastoma for degradation. The engineered βTrCP has been extensively modified to increase its specificity in substrate selection. This optimized protein-knockout system offers a powerful and versatile proteomic tool to dissect diverse functional properties of cellular proteins in somatic cells.

Understanding the function of a given cellular protein often requires alterations of its steady-state levels to examine the associated physiological consequences. Overexpression of the gene of interest has been extensively used to assess its functions. However, this method may generate gain-of-function phenotypes instead of revealing the genuine physiological properties. A number of approaches that aim at removing a cellular protein in somatic cells have been developed over the years, which include antisense deoxyoligonucleotides, ribozyme, and triple-helix DNA. Recently, RNA interference (RNAi) has been extensively used to block the biosynthesis through mRNA destruction and thus reduces the levels of a given cellular protein. All these technologies function at various levels of biosynthesis and rely on the endogenous protein degradation apparatus to remove the existing target protein. As a result, functional assessment of knockdown or knockout phenotype relies largely on the intrinsic stability of individual target proteins. The turnover rate of a given cellular protein also determines the kinetic rate of a knockdown and thus affects the analysis of primary (or immediate) versus secondary (or delayed) responses associated with the down-regulation of a specific target protein. Protein knockout is an efficient alternative approach, which involves specific engineering of the cellular ubiquitination machinery to directly remove specific proteins through accelerated proteolysis (1).

The specificity of a given ubiquitin-proteolytic pathway is conferred exclusively by the E3 ubiquitin–protein ligase (reviewed in ref. 2). One of the extensively characterized E3s is the multimeric SCFβTrCP complex, consisting of Skp1, Cullin 1, F-box-containing substrate receptor, βTrCP, and the RING domain protein Rbx1/Roc1/Hrt1 (3–7). The substrate receptor, βTrCP, is a modular protein with two distinct domains; the F-box that binds to Skp1 to connect to the core SCF complex, and the WD40 domain at the C terminus, which is exclusively responsible for substrate recruitment. This modular configuration of the F-box-containing substrate receptor bears a striking resemblance to that of transcriptional factors, which carry structurally and functionally separable DNA binding and transcriptional activation (or repression) domains. Remarkably, these two distinct classes of proteins operate similarly through regulated target recruitment (8).

Based on the modular nature of the F-box proteins, protein knockout was designed that introduces a protein–protein interaction module to the F-box-containing substrate receptors, and, thus, directing non-SCF substrates to the SCF machinery for ubiquitination and destruction (1). Similar modifications of the E6AP ubiquitin–protein ligase were also shown to promote ubiquitination of heterologous proteins (9). In addition, small synthetic ligands, designated Protacs, were designed to bridge the interaction of target protein with native βTrCP for destruction (10). In comparison to RNAi and antisense oligodeoxynucleotides, protein knockout is more effective in achieving complete eradication of target proteins. However, the use of the original chimeric F-box-containing ubiquitin–protein ligases was limited in its specificity for substrate selection. Furthermore, the application potential of the protein-knockout system has not been extensively explored. Here, we report an extensively refined protein knockout system with unique capabilities to dissect detailed functional properties of cellular proteins of interest in somatic cells.

Materials and Methods

Cell Lines, Plasmids, and Antibodies. C33A, U2OS, 293, 293T, and HeLa cells were cultured in DMEM containing 10% FBS, 100 units/ml penicillin, and 100 μg/ml streptomycin. The HL-60 promyelocytic leukemia cell line was a kind gift of Andrew Yen (Cornell University, Ithaca, NY) and was maintained in RPMI medium 1640 supplemented with 5% FCS. The pcDNA-F-TrCP, pcDNA-F-TrCP-E7N, and pcDNA-F-TrCP-E7N(ΔDLYC) plasmids have been described (1). FLAG-tagged βTrCP(m1)-E7N, which carries five amino acid substitutions (R285E, K365E, R474E, R521E, and R524E), was generated by using the QuikChange multisite-directed mutagenesis kit (Stratagene). F-TrCP-10GS-E7m, which carries the minimal retinoblastoma (RB)/p107/p130-binding domain derived from the E7 protein of the human papillomavirus type 16 (HPV16) and preceded by 10 copies of Gly-Ser (GS) repeats, was generated by PCR and cloned into pcDNA3 (Invitrogen). F-TrCP-E7N, F-TrCP(m1)-E7N and F-TrCP-E7N(ΔDLYC) were also cloned into the BamHI/NotI sites of the pBMN-GFP retroviral plasmid (Orbigen, San Diego). pBMN-GFP is a bicistronic retroviral vector that also expresses GFP from the Moloney murine leukemia virus long terminal repeat (LTR) and the internal ribosomal entry site. Antibodies against RB, p107, p130, cyclin A, cdk2, and IκB were purchased from Santa Cruz Biotechnology, FLAG (M2) was from Sigma, and hypophosphorylated and hyperphosphorylated RB were from BD Biosciences and Cell Signaling Technology (Beverly, MA), respectively. Indirect immunofluorescence assay was performed as described (11).

Transfection and Retroviral Infection. Transient transfections of C33A cells were performed by calcium phosphate precipitation (Promega). One microgram of pCMV-CD19 was included in transient transfections, and transfected C33A cells were enriched by using the anti-CD19 immunomagnetic beads (1). To generate recombinant retroviruses, the pBMN-F-TrCP-E7N, pBMN-F-TrCP-E7N(ΔDLYC), or pBMN-GFP plasmids were transfected into 293T cells together with the SV-A-MLV-ENV and pEQ-PAM3(–E) plasmids carrying the amphotropic murine leukemia virus env gene and the gag/pol genes, respectively (12). The viral supernatant was harvested at 24, 48, and 72 h and was used for infection of the HL-60 cells to assess degradation of the RB family proteins. Fluorescence-activated cell sorter (FACS) analysis was carried out to isolate infected HL-60 cells, which was based on the expression of GFP from the recombinant retroviruses.

Results

Modulation of Cellular p107 Levels Through Controlled Proteolysis. We have previously shown that the endogenous p107, a member of the RB family of proteins, which is not a natural substrate of SCFβTrCP, can be eliminated in the C33A cervical carcinoma cells by the ectopic expression of a chimeric βTrCP ubiquitin–protein ligase (βTrCP-E7N) that carries a p107-binding peptide derived from the N-terminal 35-aa residues of the HPV oncoprotein, E7 (E7N) (1). However, the functions of many cellular proteins are dictated by their intracellular abundance, and not simply by their presence or absence. Thus far, there has not been a reliable method to precisely modulate the intracellular protein levels in mammalian cells.

We first investigated whether p107 levels could be systematically reduced through controlled expression of different amounts of βTrCP-E7N. The human C33A cervical carcinoma cells were infected with increasing doses of recombinant adenovirus carrying βTrCP-E7N or the control adenovirus for 24 h. Infection was 100%, even at the lowest dose [a multiplicity of infection (moi) of 10] used, as judged by the expression of GFP carried by the adenovirus in all recipient cells (data not shown). As shown in Fig. 1 (Upper), the endogenous p107 levels were systematically reduced to 78%, 25%, and 5% of the steady-state levels when C33A cells were transduced with recombinant βTrCP-E7N adenovirus at mois of 10, 35, and 80, but not the same doses of Ad1 control virus. Therefore, the engineered SCFβTrCP-BP offers a simple and reproducible means to reduce the overall amounts of target proteins at defined levels for assaying the dosage effects on biological activities.

Fig. 1.

Systematic reduction of the endogenous p107 by F-TrCP-E7N. C33A cells were infected with increasing doses of recombinant Ad-F-TrCP-E7N adenovirus for 48 h. The levels of endogenous p107, cyclin A, Cdk2, and β-actin (loading control) were detected by immunoblotting with the respective antibodies, and in comparison with the dose-dependent increase in the expression of F-TrCP-E7N. The percentages of p107 remaining in each adenovirus-infected cell were quantitated by densitometry scanning and are indicated.

P107 stably associates with cyclin A and Cdk2 through a high-affinity binding site in proliferating cells (13–15). To examine whether these p107-associated proteins are also subjected to targeted degradation by βTrCP-E7N, immunoblotting was performed in C33A cells infected by the Ad-F-TrCP-E7N virus. As shown in Fig. 1, the endogenous cyclin A and Cdk2 levels remained unaltered, whereas p107 was dramatically down-regulated. Furthermore, the levels of nontargeted β-actin were not affected by F-TrCP-E7N (Fig. 1). This result provided strong evidence that the engineered βTrCP-E7N ubiquitin–protein ligase specifically degrades targeted substrate p107, but not its associated proteins.

Selective Degradation of a Specific Posttranslationally Modified Subpopulation of Target Protein. Modification of a cellular protein at the posttranslational level, such as phosphorylation, is a fundamental means cells employ to regulate the function or to confer new activities of the protein. Experimental tools to dissect the function associated with a specific posttranslational modification event are currently limited. Because protein knockout operates at the posttranslational level that directly recognizes target proteins, one application is to engineer a specific E3 that is capable of selecting a subpopulation of posttranslationally modified proteins for degradation, instead of destroying the entire population.

The HPV16 E7 was found to selectively bind to the hypophosphorylated form of RB (16). We investigated whether the chimeric βTrCP-E7N ubiquitin–protein ligase could distinguish hypo- and hyperphosphorylated RB and select only the hypoform for degradation. The human U2OS osteosarcoma cells express both forms of RB that can be readily identified, based on their different electrophoretic mobility on SDS/PAGE (Fig. 2A, lane 1) (17). The identity of these two RB species was further verified by immunoblotting using antibodies specific for either hypo- or hyperphosphorylated forms of RB (Fig. 2A, lanes 2 and 3). U2OS cells were infected with the recombinant Ad-F-TrCP-E7N or the control Ad1 adenoviruses for 48 h, and the steady-state levels of RB-P and RB were analyzed simultaneously by Western blotting, using an anti-RB monoclonal antibody that recognizes both forms. Consistent with the preferential binding of E7N to hypophosphorylated RB, ectopic expression of F-TrCP-E7N resulted in the elimination of hypophosphorylated RB, whereas the hyperphosphorylated RB-P was left intact (Fig. 2B Upper, compare lanes 4–6 with lanes 1–3). This result highlights the capability of the engineered F-TrCP-E7N ubiquitin–protein ligase in selecting a specific subpopulation of RB for degradation, which was based on the status of certain posttranslational modification of the target protein.

Fig. 2.

Selective degradation of hypophosphorylated form of RB in U2OS cells. (A) U2OS cells contain both hypophosphorylated and hyperphosphorylated forms of RB. Immunoblotting was carried out to detect RB in U2OS cell extracts by using antibodies that recognize both RB forms (lane 1) (IF8, Santa Cruz Biotechnology), or specific for hypo- (lane 2) (G99–549, BD Biosciences) or hyperphosphorylated RB (lane 3) [(phospho-RB (Ser 807/811) polyclonal antibody, Cell Signaling]. (B) U2OS cells were infected with increasing doses (in μl) of Ad1-F-TrCP-E7N or control pAd1 adenoviruses for 48 h. Cell extracts were prepared and immunoblotted with antibodies against RB, p107, FLAG (M2), p21waf1, p27kip1, and β-actin.

Full-length HPV16 E7 could interact with the cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitors p21Waf1 and p27Kip1, but the binding domain was mapped to the C-terminal domain (residues 40–98), instead of the E7N fragment (residues 18–20). To further examine the specificity of F-TrCP-E7N, the same U2OS cell extracts were also probed with antibodies against p21Waf1 and p27Kip1. As seen in Fig. 2B (Middle), the steady-state levels of p21Waf1 and p27Kip1 remained unaltered. Taken together, the engineered F-TrCP-E7N demonstrated proteolytic specificity toward the RB family proteins, but not other cell-cycle regulators such as Cdk2, cyclin A, p21Waf1, and p27Kip1.

Structure-Based Mutagenesis to Generate a Highly Specific βTrCP-E7N Ubiquitin–Protein Ligase. The chimeric βTrCP-E7N is still capable of binding the endogenous βTrCP substrates, including IκB, β-catenin, and ATF4 (3–7). Overexpression of βTrCP-E7N might interfere with degradation of these native substrates. Conversely, binding of the endogenous substrate to βTrCP-E7N might interfere with the proper positioning of the intended substrate to accept ubiquitin from ubiquitin-conjugating enzyme, and therefore reduce the efficiency of targeted degradation (Fig. 3A Upper). Furthermore, βTrCP interacts with a pseudo substrate hnRNP-U, which tethers βTrCP and its derivatives in the nucleus and precludes their interaction with the substrates (21). By introducing specific mutations of the amino acid residues on βTrCP to eliminate its binding to β-catenin, IκB, or hnRNP-U, we anticipate to improve not only the specificity but also the availability of the engineered βTrCP-E7N to recruit the intended substrate (Fig. 3A Lower).

Fig. 3.

Structure-based mutagenesis of the substrate-binding residues on the engineeredβTrCP-E7N ubiquitin–protein ligase. (A) Schematic diagrams of the predicted SCFβTrCP-BP/IκB/target and SCFβTrCP(m1)-BP/target complexes. BP, binding peptide; T, target. (B) Three-dimensional model of the WD40 repeats of βTrCP. The five positively charged residues are cyan. (C) The modified F-TrCP(m1)-E7N ubiquitin–protein ligase cannot bind to IκB, but retains its interaction with p107. HeLa cells were transiently transfected with IκB, together with pcDNA3 (lane 1), F-TrCP (lane 2), F-TrCP-E7N (lane 3), and F-TrCP(m1)-E7N (lane 4), and treated with MG132 for2hand then with TNF-α for 15 min. Cell extracts were prepared for immunoprecipitation with the anti-FLAG (M2) antibody, and probed with either phosphorylated IκB antibody or anti-p107 polyclonal antibody. F-TrCP(m1)-E7N migrates as a doublet on SDS gels for reasons yet to be determined (lane 4). (D)Efficient degradation of p107 by F-TrCP(m1)-E7N in C33A cells. C33A cells transfected with the indicated plasmids and 1 μg of pCMV-CD19 were enriched by immunomagnetic selection, and levels of endogenous p107 were examined by immunoblotting. (E) Indirect immunofluorescence assay was carried out to detect endogenous p107 (Center) in response to transient transfection and expression of F-TrCP, F-TrCP-E7N, or F-TrCP(m1)-E7N (Left) in individual C33A cells (marked by arrows). Images of the same field of cells counterstained with 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI) were shown to identify the nuclei of both transfected (marked by arrows) and untransfected cells.

The substrate-binding domain of βTrCP contains seven WD40 repeats in the C-terminal region, which fold into the typical seven-bladed β-propeller structure conserved among WD40 proteins (3–7). Because the overall integrity of the β-propeller structure of WD40 proteins is critical for their functions, standard deletion mutagenesis approach will likely induce gross structural alterations, and, thus, is not applicable for defining substrate-binding sites on βTrCP. However, the known crystal structure of WD40 proteins can be exploited to identify surface residues involved in binding βTrCP substrates. A structure-based mutagenesis approach was designed to identify and mutate five positively charged residues (R285, K365, R474, R521, and R524), predicted to reside on the top surface of the WD40 β-propeller, which are involved in binding to WD40-associated proteins (Fig. 3B) (22). This approach was detailed in Supporting Methods, which is published as supporting information on the PNAS web site. Also, see Fig. 6, which is published as supporting information on the PNAS web site. Furthermore, substitutions of these Lys/Arg residues will not likely alter the overall βTrCP structure.

By using the QuikChange multisite-directed mutagenesis kit (Stratagene), we have simultaneously mutated these residues to Glu. This FLAG-tagged compound mutant, designated F-TrCP(m1)-E7N, was tested for its binding to both the endogenous (IκB) and the intended (p107) knockout targets. HeLa cells were transiently transfected with F-TrCP(m1)-E7N or F-TrCP-E7N, and their interactions with IκB and p107 were determined by coimmunoprecipitation. F-TrCP-E7N and F-TrCP exhibited similar affinities to the phosphorylated IκB protein, whereas the compound m1 mutations abolished F-TrCP(m1)-E7N binding (Fig. 3C Middle). In contrast, similar levels of p107 were detected in the immunocomplexes of F-TrCP-E7N or F-TrCP(m1)-E7N (Fig. 3C Lower), indicating that the engineered F-TrCP(m1)-E7N ubiquitin–protein ligase is fully functional in recruiting the intended cellular targets. These results are in agreement with the structural predictions in Fig. 3B, and further define the amino acid residues on βTrCP critical for endogenous substrate recognition.

The engineered F-TrCP(m1)-E7N was further analyzed for its potency in degrading endogenous p107. C33A cells were cotransfected with F-TrCP, F-TrCP-E7N, or F-TrCP(m1)-E7N, together with a CD19 expression plasmid. Forty-eight hours after transfection, cells were harvested and enriched for those receiving the transfected plasmids by using the immunomagnetic beads conjugated to the anti-CD19 monoclonal antibody. Endogenous p107 levels were subsequently determined by immunoblotting. As shown in Fig. 3D, ectopic expression of F-TrCP(m1)-E7N resulted in a 95% reduction of endogenous p107 levels, whereas an 82% down-regulation of p107 was observed for F-TrCP-E7N (Fig. 3D Upper, compare lanes 4 and 3). Furthermore, expression of F-TrCP(m1)-E7N had no observable effect on tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-α induced degradation of IκB by the native SCFβTrCP, or on destruction of p27kip1 by the SCFSkp2 ubiquitin–protein ligases (data not shown). Therefore, ectopic expression of the engineered F-TrCP(m1)-E7N does not interfere with the overall SCF ubiquitination activity by squelching the core SCF components (Skp1, CUL-1, and Rbx1/Roc1) shared by the endogenous F-box proteins.

Targeted p107 degradation was further assessed in individual C33A cells by indirect immunofluorescence assay. Consistently, p107 was largely eradicated in C33A cells expressing F-TrCP-E7N or F-TrCP(m1)-E7N, but not F-TrCP alone (Fig. 3E). Collectively, these results indicate that by eliminating the binding sites of the endogenous βTrCP substrates, the engineered F-TrCP(m1)-E7N ubiquitin–protein ligase demonstrated increased specificity and robust proteolytic activity toward the intended target.

Minimal Binding Domain as Targeting Peptide for Efficient Substrate Recruitment. To achieve high specificity of substrate recruitment and to minimize nonspecific targeting of other cellular proteins, we tested whether the minimal p107/RB interaction domain of E7N (designated E7m), which encompasses residues 21–29 of E7 spanning the LXCXE motif (23), could achieve efficient binding and degradation of p107. A chimeric ubiquitin–protein ligase was constructed in which βTrCP and E7m were covalently linked together by a flexible 20-aa spacer comprised of 10 copies of Gly-Ser repeats (designated 10GS). The F-TrCP-E7N or F-TrCP-10GS-E7m were transiently transfected into C33A cells, and their binding to the endogenous p107 was assessed by immunoprecipitation in extracts prepared after treatment with the proteasome inhibitor MG132 to inhibit degradation as a consequence of this interaction. As shown in Fig. 4A (lanes 2 and 3), F-TrCP-10GS-E7m had slightly increased affinity to p107 than that of the original F-TrCP-E7N. The F-TrCP-E7N and F-TrCP-10GS-E7m were further evaluated for their efficiency in p107 degradation by transient transfection in C33A cells as in Fig. 3D. As shown in Fig. 4B, F-TrCP-E7N and F-TrCP-10GS-E7m induced up to 92% and 95% down-regulation of p107, indicating that the engineered βTrCP carrying the minimal p107-binding domain functions as efficiently as the original F-TrCP-E7N in degrading target proteins.

Fig. 4.

The minimal p107-binding domain of E7 is sufficient to recruit p107 for targeted destruction. (A) The engineered F-TrCP-10GS-E7m ubiquitin–protein ligase efficiently binds to p107. C33A cells transiently transfected with the indicated plasmids were treated with the proteasome inhibitor MG132 for 2 h. Cell extracts were prepared for immunoprecipitation with the anti-FLAG antibody, and were probed with antibodies against FLAG or p107. (B) Degradation of the endogenous p107 by the engineered F-TrCP-E7m. C33A cells were transiently transfected with the indicated plasmids (in μg) and 1 μg of pCMV-CD19. Transfected cells were enriched by immunomagnetic bead selection, and the steady-state levels of p107, F-TrCP fusions, and β-actin (loading control) were determined by immunoblotting using antibodies against p107, FLAG, and β-actin. The experiment was repeated four times, and the amount of p107 remaining was measured by PhosphorImager analysis. Endogenous β-actin levels were also measured as an internal loading control.

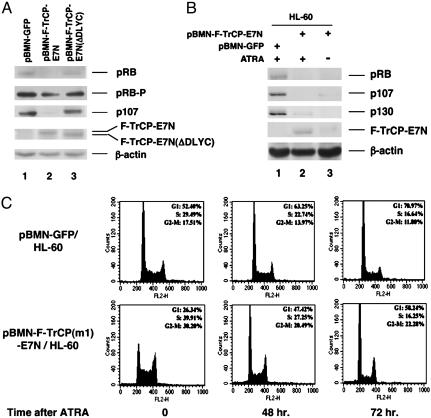

Retroviral-Mediated Delivery of the Engineered βTrCP for Sustained Degradation of Endogenous Targets. We next examined whether the engineered ubiquitin–protein ligases could be stably expressed to achieve sustained degradation of the intended target. The HL-60 promyelocytic leukemia cells were transduced with the recombinant retroviruses expressing PBMN-GFP, F-TrCP(m1)-E7N, or the control F-TrCP-E7N(ΔDLYC), in which the RB/p107-binding site was deleted (1). Infected cells with chromosomally integrated chimeric F-TrCP transgenes were isolated by FACS sorting, based on the expression of GFP from the viruses, and degradation of the endogenous p107 was assessed from infected HL-60 cells either immediately after infection (Fig. 5A), or after 3 months of culturing in growth medium (Fig. 5B). Furthermore, because two other members of the RB family proteins, RB and p130, are also expressed in HL-60 cells, we examined whether a single F-TrCP-E7N can simultaneously target degradation of the entire RB family of proteins that interact with the same LXCXE motif of E7N. Ectopic expression of retrovirally transduced F-TrCP-E7N induced dramatic down-regulation of the hypophosphorylated form of RB, as well as p107 (Fig. 5A) and p130 (data not shown) in HL-60 cells, either immediately after infection and FACS sorting (Fig. 5A), or 3 months after infection and continuous culturing (Fig. 5B, lane 3). In contrast, stable expression of F-TrCP-E7N(ΔDLYC) in HL-60 cells had no effect on altering p107, RB (Fig. 5A, lane 3), and p130 levels (data not shown). Consistent with the observation that F-TrCP-E7N preferentially degrades hypophosphorylated RB in U2OS cells (Fig. 2), reduction of hyperphosphorylated RB species by stable expression of F-TrCP-E7N was less pronounced, compared with that of the hypophosphorylated form in HL-60 cells (Fig. 5A, compare lane 2 of pRB and pRB-P).

Fig. 5.

Retroviral-mediated delivery of the engineered F-TrCP-E7N ubiquitin–protein ligase for targeted degradation of RB family proteins in the HL-60 cells. (A) HL-60 cells infected with the indicated recombinant retroviruses were isolated by FACS, and the steady state levels of RB, p107, F-TrCP-E7N, and F-TrCP-E7N(ΔDLYC) were determined by immunoblotting using the respective antibodies. β-Actin levels were also determined as a specificity and internal loading control. RB and RB-P denote hypo- and hyperphosphorylated RB. (B) Infected and FACS-sorted HL-60 cells were cultured for 3 months, and either untreated (lane 3) or treated with 1 μM of ATRA for 72 h (lane 2). Endogenous RB, p107, and p130 were determined in response to the expression of F-TrCP-E7N by immunoblotting. (C) FACS analysis to determine the DNA contents of the live HL-60 cells infected by control or pBMN-F-TrCP(m1)-E7N retroviruses under normal growth conditions and in response to ATRA-induced growth arrest.

On treatment with all-trans retinoic acid (ATRA), HL-60 cells exit cell cycle and undergo terminal differentiation. An accumulation of hypophosphorylated RB was observed, which was previously reported to contribute to ATRA-induced growth arrest, whereas the hyperphosphorylated RB was not detectable (24, 25). To examine whether the SCFβTrCP machinery can also be harnessed during cell-cycle exit, HL-60 cells stably expressing F-TrCP-E7N or F-TrCP(m1)-E7N were treated with 1 μM ATRA for 72 h, and degradation of the RB family proteins were evaluated. HL-60 cells stably expressing F-TrCP-E7N resulted in 95%, 98%, and 85% decrease of RB, p107, and p130 levels respectively, compared with cells infected with the control pBMN-GFP virus (Fig. 5B, lane 2). Because ATRA also activates transcription of genes under the control of Moloney murine leukemia virus LTR of pBMN-GFP (26), the increased expression of F-TrCP-E7N on ATRA treatment likely further contributed to the efficient down-regulation of p107, p130, and hypophosphorylated RB (Fig. 5B).

The effect of the RB family proteins on normal cell-cycle progression has been examined in mouse embryo fibroblasts with disruptions in RB, p107, and p130 genes, and found to be unresponsive to signals that induce G1 arrest, such as growth factor withdraw or DNA damage (27, 28). However, the collective effects of the RB family members in tumor cell proliferation have not been studied, due to the lack of efficient reverse genetic tools. The stable HL-60 cells expressing F-TrCP(m1)-E7N from this study allowed us to assess how tumor cells deficient for all three RB family proteins responded to G1-arrest signals. In exponentially growing HL-60 cells expressing F-TrCP(m1)-E7N that induced constitutive degradation of the RB family proteins, a marked acceleration of cell-cycle progression was observed in comparison with those infected by the control pBMN-GFP virus (Fig. 5C Left). This result is consistent with the impaired control of G1–S transitions observed in RB–/–, p107–/–, and p130–/– triple knockout mouse embryo fibroblasts (27, 28).

ATRA treatment inhibited G1-to-S-phase transition in HL-60 cells infected by the control pBMN-GFP (Fig. 5C) or F-TrCP-E7N(ΔDLYC) virus (data not shown), which is consistent with what was reported for uninfected HL-60 cells (Fig. 5C) (24). An initial delay in G1–S transition was also observed in pBMN-F-TrCP(m1)-E7N/HL-60 cells at 48 h after ATRA. However, a complete G1 arrest could not be achieved at the later stage (72–96 h) and cells continued the course of cell-cycle progression (Fig. 5C). In contrast, the control pBMN-GFP/HL-60 cells were all blocked in G1 between 72 and 96 h. These observations suggest that F-TrCP(m1)-E7N-mediated degradation of RB family members impairs a late ATRA-response event necessary for completion of growth arrest, whereas the early attenuation of G1–S progression was largely unaffected. Furthermore, a dramatic reduction in cell numbers was observed between 72 and 96 h post-ATRA treatment due to massive cell death during ATRA-induced cell-cycle exit and differentiation (29). Strikingly, HL-60 cells expressing F-TrCP(m1)-E7N exhibited an average increase of 2- to 3-fold in the subG1 populations compared with that of the control virus infected HL-60 cells (data not shown), which is consistent with the increased cell death in RB–/–, p107–/–, and p130–/– triple knockout mouse embryonic fibroblast cells under growth-inhibitory conditions (28). Collectively, constitutive expression of F-TrCP(m1)-E7N induced down-regulation of the entire RB family proteins, which leads to an inhibition of growth arrest and an increase in cell death on ATRA treatment.

ATRA-induced G1 arrest involves the coordinated regulation of multiple cellular signals/components that negatively control the cell cycle (reviewed in ref. 30). Dimberg et al. (31) reported that ATRA triggers a sequence of events in myeloid cells involving an early increase in p21waf1 expression, stabilization of p27kip1, and, later, dephosphorylation of RB at the onset of G1 arrest. Because βTrCP(m1)-E7N only degrades RB family members and has no effect on the stability of p21waf1 and p27kip1, it is likely that only the late, RB-dependent ATRA response is affected, which is consistent with the resistance of pBMN-F-TrCP(m1)-E7N/HL-60 cells to complete G1 arrestat72–96 h (Fig. 5C). The observed early growth inhibition by ATRA at 48 h (Fig. 5C) could be attributed, at least in part, to the up-regulation of p21waf1 and p27kip1, whose stability is not affected by constitutive F-TrCP(m1)-E7N expression (Figs. 2 and 5).

Discussion

The engineered proteolysis system demonstrated rapid elimination, as well as systematic reduction of endogenous cellular proteins (such as p107). This latter property is due to the fact that the engineered βTrCP ubiquitin–protein ligases are likely functioning in a stoichiometric, but not catalytic manner. It is possible to control the engineered proteolytic activity by precisely modulating the expression levels of the engineered βTrCP, and this can be achieved through infection with different doses of recombinant adenoviruses. This fine-tuning property of the protein-knockout system offers a simple and reproducible means to study gene dosage effects in greater detail than a simple knockout or knockdown approach, and is especially valuable for studying essential proteins whose elimination is detrimental to cell growth or survival. Furthermore, the rapid kinetic rate of targeted proteolysis allows for functional evaluation as early as 8–12 h (see Fig. 7, which is published as supporting information on the PNAS web site), similar or even faster than what can be achieved by an inducible gene expression system. Thus, the protein-knockout approach allows rapid and controlled down-regulation of cellular proteins, which opens up avenues for detailed functional assessment of cellular proteins.

A second feature of the protein-knockout system is its ability to identify a specific subpopulation of cellular protein for destruction (Figs. 2 and 5A). Remarkably, the endogenous βTrCP itself has evolved the similar capability to recruit only the substrates that are Ser/Thr-phosphorylated for destruction, while leaving the unphosphorylated subpopulation intact (4). Because the protein knockout system operates at the posttranslational level, it offers a tool to delineate the functional consequences associated with specific posttranslational modifications. In this regard, other knockout or knockdown technologies that function through blocking protein synthesis, such as RNAi or antisense oligodeoxynucleotides, cannot make such distinctions.

The versatility of the protein knockout system is further highlighted by the observation that a single chimeric ubiquitin–protein ligase could simultaneously target degradation of multiple members of a protein family (Fig. 5). This feature offers a simple method to study a specific biological activity conferred by multiple protein family members that share redundant functions. In the event that individual family members need to be singled out to evaluate its contributions to a specific biological activity, targeting peptides against unique regions of the individual substrates should be used. Alternatively, single-chain antibody Fv fragment against a specific family member can be used as binding peptides with exquisite substrate specificity.

To facilitate the application of the protein-knockout system, several improvements have been made to increase the specificity of the engineered ubiquitin–protein ligases. They include (i) elimination of the binding sites for the endogenous βTrCP substrates; (ii) the use of minimal-binding domain as the targeting peptide; and (iii) stable expression of the engineered βTrCP for sustained degradation of the target of interest by using retroviral based vectors. Furthermore, the engineered βTrCP-E7N was shown to specifically target degradation of p107, but not cellular proteins that associate with p107, such as cyclin A and Cdk2. Based on the crystal structure of the SCFβTrCP complex (32), it is conceivable that p107 is likely positioned correctly between βTrCP-E7N and the ubiquitin-conjugating enzyme to accept ubiquitin transfer, whereas cyclin A and Cdk2 are either improperly positioned or misoriented, and, thus, incapable of receiving ubiquitin.

General applications of the protein-knockout system depend on the availability of specific targeting peptides for recruiting the desired substrate. The genome-wide screening of protein–protein interactions by the yeast two-hybrid assays is anticipated to add tremendous information to the current efforts to delineate protein complexes in the proteome, and further provide candidate targeting peptides for the protein-knockout vectors. Alternatively, targeting peptides can be obtained from screening the phage display or random peptide aptamer-based yeast two-hybrid libraries. Combined with RNAi, antisense, ribozyme, and other technologies, it is possible to achieve a comprehensive analysis of the functions of specific cellular proteins in somatic cells and in animals.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank A. Schenkel, N. Lue, and J. Miller for critical reading of the manuscript; P. Howley for the generous support of this work in its initial stages and for helpful comments; A. Yew for HL-60 cells; Z. Ronai and H. Habelhah for technical advice; T. He and B. Vogelstein for the pAdEasy adenoviral system; and X. Lu for technical assistance. P. Z. was a recipient of the Kimmel Scholar Award from the Sidney Kimmel Foundation for Cancer Research (Philadelphia). This work was supported by National Institutes of Health Grant 1R21-CA92792-01 (to P.Z.); the Academic Medicine Development Company Foundation; the Mary Kay Ash Charitable Foundation; the Speaker's Fund from the New York Academy of Medicine; the Dorothy Rodbell Cohen Foundation for Sarcoma Research; and the Susan G. Komen Foundation for Breast Cancer Research (P.Z.)

This paper was submitted directly (Track II) to the PNAS office.

Abbreviations: ATRA, all-trans retinoic acid; RB, retinoblastoma; RNAi, RNA interference; SCF, Skp1, Cullin 1, and F-box-containing substrate receptor; FACS, fluorescence-activated cell sorter.

Note Added in Proof. While this paper was under revision, Wu et al. (32) published the crystal structure of the βTrCP-phosphorylated β-catenin complex. Remarkably, R285, R474, and R521, which we mutated in βTrCP(m1), were shown to be in direct contrast with β-catenin.

References

- 1.Zhou, P., Bogacki, R., McReynolds, L. & Howley, P. M. (2000) Mol. Cell 6, 751–756. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hershko, A. & Ciechanover, A. (1998) Annu. Rev. Biochem. 67, 425–479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Yaron, A., Hatzubai, A., Davis, M., Lavon, I., Amit, S., Manning, A. M., Andersen, J. S., Mann, M., Mercurio, F. & Ben-Neriah, Y. (1998) Nature 396, 590–594. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Winston, J. T., Strack, P., Beer-Romero, P., Chu, C. Y., Elledge, S. J. & Harper, J. W. (1999) Genes. Dev. 13, 270–283. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tan, P., Fuchs, S. Y., Chen, A., Wu, K., Gomez, C., Ronai, Z. & Pan, Z. Q. (1999) Mol. Cell 3, 527–533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Latres, E., Chiaur, D. S. & Pagano, M. (1999) Oncogene 18, 849–854. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lassot, I., Segeral, E., Berlioz-Torrent, C., Durand, H., Groussin, L., Hai, T., Benarous, R. & Margottin-Goguet, F. (2001) Mol. Cell. Biol. 21, 2192–2202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ptashne, M. & Gann, A. (2002) Genes and Signals (Cold Spring Harbor Lab. Press, Plainview, NY).

- 9.Colas, P., Cohen, B., Ko Ferrigno, P., Silver, P. A. & Brent, R. (2000) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 97, 13720–13725. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sakamoto, K. M., Kim, K. B., Kumagai, A., Mercurio, F., Crews, C. M. & Deshaies, R. J. (2001) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 98, 8554–8559. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chen, X., Zhang, Y., Douglas, L. & Zhou, P. (2001) J. Biol. Chem. 276, 48175–48182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Persons, D. A., Mehaffey, M. G., Kaleko, M., Nienhuis, A. W. & Vanin, E. F. (1998) Blood Cells Mol. Dis. 24, 167–182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ewen, M. E., Faha, B., Harlow, E. & Livingston, D. M. (1992) Science 255, 85–87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Faha, B., Ewen, M. E., Tsai, L. H., Livingston, D. M. & Harlow, E. (1992) Science 255, 87–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lees, E., Faha, B., Dulic, V., Reed, S. I. & Harlow, E. (1992) Genes Dev. 6, 1874–1885. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dyson, N., Guida, P., Munger, K. & Harlow, E. (1992) J. Virol. 66, 6893–6902. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Xiao, Z. X., Ginsberg, D., Ewen, M. & Livingston, D. M. (1996) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 93, 4633–4637. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Funk, J. O., Waga, S., Harry, J. B., Espling, E., Stillman, B. & Galloway, D. A. (1997) Genes Dev. 11, 2090–2100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Helt, A. M., Funk, J. O. & Galloway, D. A. (2002) J. Virol. 76, 10559–10568. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zerfass-Thome, K., Zwerschke, W., Mannhardt, B., Tindle, R., Botz, J. W. & Jansen-Durr, P. (1996) Oncogene 13, 2323–2330. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Davis, M., Hatzubai, A., Andersen, J. S., Ben-Shushan, E., Fisher, G. Z., Yaron, A., Bauskin, A., Mercurio, F., Mann, M. & Ben-Neriah, Y. (2002) Genes Dev. 16, 439–451. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sprague, E. R., Redd, M. J., Johnson, A. D. & Wolberger, C. (2000) EMBO J. 19, 3016–3027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lee, J. O., Russo, A. A. & Pavletich, N. P. (1998) Nature 391, 859–865. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mihara, K., Cao, X. R., Yen, A., Chandler, S., Driscoll, B., Murphree, A. L., T'Ang, A. & Fung, Y. K. (1989) Science 246, 1300–1303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Yen, A., Placanica, L., Bloom, S. & Varvayanis, S. (2001) J. Virol. 75, 5302–5314. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Collins, S. J. (1988) J. Virol. 62, 4349–4352. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sage, J., Mulligan, G. J., Attardi, L. D., Miller, A., Chen, S., Williams, B., Theodorou, E. & Jacks, T. (2000) Genes Dev. 14, 3037–3050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Dannenberg, J. H., van Rossum, A., Schuijff, L. & te Riele, H. (2000) Genes Dev. 14, 3051–3064. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bobichon, H., Mayer, P., Carpentier, Y. & Desoize, B. (1998) Int. J. Oncol. 12, 649–653. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lawson, N. D. & Berliner, N. (1999) Exp. Hematol. (Charlottesville, Va) 27, 1355–1367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Dimberg, A., Bahram, F., Karlberg, I., Larsson, L. G., Nilsson, K. & Oberg, F. (2002) Blood 99, 2199–2206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wu, G., Xu, G., Schulman, B. A., Jeffrey, P. D., Harper, J. W. & Pavletich, N. P. (2003) Mol. Cell 11, 1445–1456. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.