Abstract

Assigning biologic function to the many sequenced but still uncharacterized genes remains the greatest obstacle confronting the human genome project. Differential gene expression profiling routinely detects uncharacterized genes aberrantly expressed in conditions such as cancer but cannot determine which genes are functionally involved in such complex phenotypes. Integrating gene expression profiling with specific modulation of gene expression in relevant disease models can identify complex biologic functions controlled by currently uncharacterized genes. Here, we used systemic gene transfer in tumor-bearing mice to identify novel antiinvasive and antimetastatic functions for Fkbp8, and subsequently for Fkbp1a. Fkbp8 is a previously uncharacterized member of the FK-506-binding protein (FKBP) gene family down-regulated in aggressive tumors. Antitumor effects produced by Fkbp1a gene expression are mediated by cellular pathways entirely distinct from those responsible for antitumor effects produced by Fkbp1a binding to its bacterially derived ligand, rapamycin. We then used gene expression profiling to identify syndecan 1 (Sdc1) and matrix metalloproteinase 9 (MMP9) as genes directly regulated by Fkbp1a and Fkbp8. FKBP gene expression coordinately induces the expression of the antiinvasive Sdc1 gene and suppresses the proinvasive MMP9 gene. Conversely, short interfering RNA-mediated suppression of Fkbp1a increases tumor cell invasion and MMP9 levels, while down-regulating Sdc1. Thus, syndecan 1 and MMP9 appear to mediate the antiinvasive and antimetastatic effects produced by FKBP gene expression. These studies show that uncharacterized genes differentially expressed in metastatic cancers can play important functional roles in the metastatic phenotype. Furthermore, identifying gene regulatory networks that function to control tumor progression may permit more accurate modeling of the complex molecular mechanisms of this disease.

FKBP12 (Fkbp1a), an extensively characterized member of the FK-506-binding protein (FKBP) family, is expressed ubiquitously in cells. It was originally identified as a cytosolic receptor for the immunosuppressant drugs, FK506 and rapamycin, and later shown to be involved in cell-cycle regulation and in intracellular calcium homeostasis (1–3). Binding of Fkbp1a to rapamycin through its FK506/rapamycin-binding/peptidylprolyl isomerase (PPIase) domain mediates the immunosuppressive and antitumor effects of rapamycin (1, 4). Rapamycin has previously been documented to exert significant antitumor effects against several different murine tumors, mediated by its ability to arrest tumor cells in G1 phase of the cell cycle and to reduce tumor angiogenesis (1, 4–8). CCI-779, a soluble ester analog of rapamycin, will need to be evaluated against several different tumor types in human clinical trials (5).

Conversely, FKBP-related 38-kDa protein (Fkbp8) has no identified function, but has been assigned to the FKBP family, based on its extensive amino acid homology to the FK-506/rapamycin-binding/PPIase domain of Fkbp1a (9). This protein also contains a three-unit tetratricopeptide repeat and a leucinezipper repeat, suggesting that it may form multimeric complexes with yet unidentified proteins. Fkbp8 was found to be highly expressed in various tissues including brain, kidney, liver, and testis, whereas moderate expression was observed in lung, spleen, heart, ovary (9, 10), and activated T cells (unpublished data). In contrast to Fkbp1a, Fkbp8 does not bind to FK506 or rapamycin, nor does it possess PPIase activity (9, 10). Fkbp8 has been shown to be selectively down-regulated in less differentiated, more aggressive Schwannoma tumor cell lines (10). In addition, we found the Fkbp8 gene to be down-regulated in a highly metastatic B16-F10-pLUC melanoma cell clone, when compared with either the parent cell line, or to the low metastatic B16-F10-p65-R clone (ref. 11 and data not shown). These findings suggested that FKBP protein(s) might play a role in cancer cell progression independent of rapamycin.

Experimental Procedures

Plasmid Construction and Purification. For detailed construction of the plasmids used, please refer to Supporting Experimental Procedures, which is published as supporting information on the PNAS web site.

In Vivo Gene Delivery and Analysis of Antitumor Activity. B16-F10 cells and 4T1 cells were freshly thawed and grown in 5% FBS in RPMI medium 1640 or 5% FBS in MEM media for 48 h, respectively. On day 0, groups of 10 6-week-old female C57BL/6 or BALB/C mice (Simonsen Laboratories, Gilroy, CA) were injected with 25,000 B16-F10 or 50,000 4T1 cells in 200 μl of culture media, respectively. Three days after tumor cell injection, each mouse was injected with 25 μg of plasmid DNA complexed to the pure DOTMA (N-[1-(2,3-dioleyloxy)-propyl]-N,N,N-trimethylammonium chloride) liposomes at a 1 μg DNA:24 nmol cationic lipid ratio (12). Mice were killed 25 days after tumor cell injection. For B16-F10-inoculated, C57BL/6 mice, the lungs were dissected out, weighed, and infused transtracheally with 5% neutral buffered formalin in 1× PBS. For 4T1-inoculated BALB/C mice, the lungs were processed as described (13). The number of black, B16-F10 pulmonary tumors, and counterstained 4T1 pulmonary tumors (white) were counted under a dissecting microscope by an individual blinded to the identity of the treatment groups. The potential statistical significance of differences was assessed by using an unpaired two-tailed Student t test.

G1 Cell-Cycle Analysis Using Fluorescence-Activated Cell Sorting Analysis. For detailed procedures on analyzing percentage of cells in G1 cell cycle, please refer to Supporting Experimental Procedures.

Western Analysis. For detailed conditions used in Western analysis, please refer to Supporting Experimental Procedures.

Real-Time Quantitative PCR. Because the antibody against Fkbp8 is not available, expression levels were documented by real-time quantitative PCR. Detailed procedure is available in Supporting Experimental Procedures.

Measurement of IL-2 Production. For detailed protocol on IL-2 measurement after transfection or rapamycin treatment of Jurkat cells, please refer to Supporting Experimental Procedures.

RNA Interference (RNAi) Construction and Transfection. Fkbp1a RNAi was synthesized in vitro by using the Silencer short interfering RNA (siRNA) construction kit (Ambion, Austin, TX), per the manufacturer's instructions. The sense DNA oligo used in in vitro transcription was: 5′-AATAGGCATAGTCTGAGGAGACCTGTCTC-3′. A negative control RNAi sequence was designed by randomizing the above oligonucleotide sequence to obtain 5′-CCTGGGTAGTCTAAATAGAAGGTAGCCTC-3′ and the negative control RNAi was synthesized by following the same protocol as the Fkbp1a RNAi. A total of 25 nM RNAi was transfected by using siPORT lipid transfection reagent (Ambion) per the manufacturer's instructions.

In Vitro Invasion Assay. For detailed methods on assessing invasive potential of tumor cells in vitro, see Supporting Experimental Procedures.

Microarray Analysis. The cDNA microarray analysis was carried out by following protocols available at http://derisilab.ucsf.edu/microarray. For detailed protocol, see Supporting Experimental Procedures.

Results

Because FKBP genes are differentially expressed in aggressive tumors, we used systemic, cationic liposome:DNA complex (CLDC)-based gene transfer to assess the role of FKBP gene expression in regulating the progression of metastatic tumors in mice. Systemic CLDC-based gene transfer can produce biologically active levels of delivered gene products in a significant percentage of both tumor cells and normal cells present in the lungs of tumor-bearing mice (11, 12). The ability to transfect normal cells, as well as tumor cells, is important, because tumors metastasize not simply due to alterations of gene expression within tumor cells, but, rather, from the complex interplay of altered gene expression patterns within critical normal cell types and tumor cells (14, 15). Cationic liposomes were complexed to an Epstein–Barr virus-based expression plasmid that can express delivered genes at therapeutic levels for prolonged periods in immunocompetent mice (16).

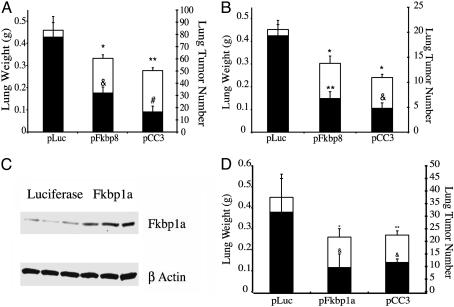

FKBP Gene Expression Reduces Tumor Progression Functions in Tumor-Bearing Mice. First, we i.v. injected groups of 10 C57BL/6 mice bearing murine B16-F10 melanoma tumors with CLDC containing a human cytomegalovirus-driven expression plasmid linked to either the human Fkbp8 cDNA, the human CC3 cDNA (a potent antitumor gene; refs. 12 and 17), or the luciferase cDNA (mock-treated controls). [Mock-treated and untreated tumor-bearing mice show comparable numbers of metastatic B16-F10 tumors (12).] Systemic delivery of the pFkbp8 or pCC3 plasmids each significantly reduced the metastatic progression of B16-F10 tumors in syngeneic C57BL/6 mice, as determined by both whole lung weights and total number of lung tumors (Fig. 1A). To ascertain whether Fkbp8 gene expression could also control the metastatic progression of 4T1 tumor cells, an aggressive mouse breast cancer line, we then i.v. injected CLDC containing the Fkbp8, CC3, or luciferase cDNAs into groups of 10 BALB/c mice bearing 4T1 mammary carcinoma tumors (12, 18). As seen with B16-F10 tumors, systemic delivery of the pFkbp8 or CC3 plasmids significantly reduced the metastatic progression of 4T1 tumors in syngeneic mice (Fig. 1B). Thus, the expression of Fkbp8, a previously uncharacterized gene, can play a significant functional role in controlling tumor metastasis.

Fig. 1.

An i.v. injection of CLDC containing either the human Fkbp8 or human Fkbp1a cDNAs produces significant antitumor effects against metastatic murine melanoma and mammary carcinoma lines grown in tumor-bearing mice. (A and B) Comparison of lung weights (□, left y axis) and number of lung tumors (▪, right y axis) in groups of 10 tumor-bearing C57BL/6 (A) or BALB/C mice (B), respectively, injected with luciferase pLuc (control), pFkbp8, or pCC3 plasmid DNA complexed to cationic liposomes. (A) *, P < 0.05 versus pLuc lung weight; **, P < 0.01 versus pLuc lung weight; &, P < 0.005 versus pLuc lung tumor number; #, P < 0.0005 versus pLuc lung tumor number. (B) *, P < 0.05 versus pLuc lung weight; **, P = 9.43E-06 versus pLuc lung tumor number; &, P = 3.24E-07 versus pLuc lung tumor number. (C) Western blot analysis of Fkbp1a protein levels in lung extracts (three from each treatment group) isolated 24-hour post i.v. injection of CLDC. (D) Comparison of lung weights (□, left y axis) and number of lung tumors (▪, right y axis) in pLuc-, pFkbp1a-, or pCC3-injected BALB/C mice. *, P < 0.01 versus pLuc lung weight; **, P < 0.05 versus pLuc lung weight; &, P < 0.05 versus pLuc lung tumor number. At least two independent experiments were carried out for each study, yielding comparable results.

Because systemic delivery of the Fkbp8 gene reduced the metastatic progression of two different highly aggressive mouse tumor cell types (Fig. 1 A and B), we then tested whether up-regulation of the human Fkbp1a gene, the best characterized member of the FKBP gene family, could produce similar anti-tumor progression effects in mice. Although Fkbp1a has been shown to mediate antitumor effects through binding to rapamycin, its immunosuppressive, bacterial-macrolide ligand, regulation of Fkbp1a gene expression per se has not previously been shown to alter the malignant phenotype. We first documented that CLDC-based systemic delivery of plasmid pFkbp1a increased Fkbp1a protein levels in the lungs of tumor-bearing mice, by using Western analysis (Fig. 1C). We then showed that CLDC-based systemic delivery of plasmid pFkbp1a significantly reduced the metastatic spread of 4T1 mammary carcinoma tumors in BALB/c mice (Fig. 1D). In addition, systemic CLDC-based delivery of pFkbp1a reduced the progression of B16-F10 melanoma metastases in C57BL/6 mice, as demonstrated by significant reductions of lung weights (P < 0.05) and of tumor numbers (P < 0.05; data not shown). Preliminary studies comparing the number of lung metastases after i.v. injection of B16-F10 melanoma cells, stably transfected with either Fkbp1a, Fkbp8, or luciferase were inconclusive, because overexpression of Fkbp1a or Fkbp8 was rapidly lost in tumor cells after their i.v. injection into mice (data not shown). Thus, we found that expression of either Fkbp8 or Fkbp1a, two quite different members of the FKBP gene family, can regulate metastatic progression in the absence of rapamycin. Because Fkbp8 does not bind rapamycin (9, 10), the antimetastatic effects produced by increased expression of the Fkbp8 appear independent of those mediated by Fkbp1a-rapamycin binding. Conversely, by using the same dose, schedule, and parenteral route of rapamycin administration that has previously been shown to produce antitumor effects in vivo (7), we found that rapamycin failed to significantly (P > 0.05 in all cases) reduce either the total lung weights or lung tumor numbers of B16-F10 or 4T1 tumors in mice (data not shown). Thus, unlike FKBP gene expression, rapamycin treatment is not significantly active against either 4T1 or B16-F10 tumors in mice.

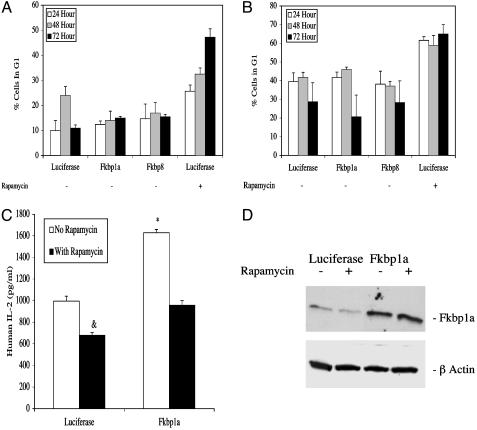

Cellular Pathways Mediating the Antitumor Effects of FKBP Gene Expression Are Distinct from Rapamycin-Induced Pathways. The final common mechanism through which the rapamycin:Fkbp1a complex produces its antiproliferative effects is by arresting tumor cells in G1 (1). Fluorescence-activated cell sorting analysis documented that rapamycin treatment (1 μM) of 4T1 mammary carcinoma (Fig. 2A) and B16-F10 melanoma cells (Fig. 2B) induced significant G1 arrest. The same levels of G1 cell-cycle arrest were achieved with lower doses of rapamycin (0.01 and 0.1 μM) (data not shown). In contrast, neither 4T1 nor B16-F10 cells transfected with, and documented to overexpress high levels of either Fkbp1a or Fkbp8 (Table 1), exhibited any evidence of G1 cell-cycle arrest (Fig. 2 A and B). Furthermore, [3H]thymidine uptake studies showed that 4T1 and B16-F10 cells overexpressing Fkbp1a or Fkbp8 remained in exponential growth, whereas rapamycin-treated cells were growth-arrested (data not shown). Thus, unlike Fkbp1a-rapamycin binding (1), overexpression of either Fkbp1a or Fkbp8 does not induce cell-cycle arrest in tumor cells.

Fig. 2.

Unlike rapamycin, neither Fkbp1a nor Fkbp8 overexpression arrests tumor cells in G1, nor does Fkbp1a overexpression suppress IL-2 production in activated Jurkat cells. Fluorescence-activated cell sorting analysis of transfected 4T1 (A) and B16-F10 (B) cells in G1 phase of cell cycle at 24, 48, and 72 h. Luciferase-transfected control cells treated with 1 μg/ml rapamycin are shown in the far right column. (C) IL-2 secretion in the media of transfected Jurkat cells in the presence or absence of 50 nM rapamycin. &, P = 6.89924E-07 versus luciferase control (no rapamycin); *, P = 5.13644E-09 versus luciferase control (no rapamycin). (D) Western blot analysis of Fkbp1a expression in transfected Jurkat cells in the presence or absence of rapamycin.

Table 1. Quantitation of Fkbp1a or Fkbp8 overexpression in transfected cells.

| Cell line | Genes transfected | Fkbp1a, mean CT* | Fkbp8, mean CT | β-actin, mean CT |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| B16 | Luciferase | 32.45 ± 0.13 | 36.69 ± 0.35 | 17.31 ± 0.30 |

| Fkbp1a | 19.02 ± 0.19 | ND | 17.24 ± 0.24 | |

| Fkbp8 | ND | 19.98 ± 0.10 | 17.07 ± 0.13 | |

| 4T1 | Luciferase | 26.28 ± 0.06 | 32.18 ± 0.48 | 17.48 ± 0.19 |

| Fkbp1a | 19.25 ± 0.03 | ND | 16.91 ± 0.08 | |

| Fkbp8 | ND | 19.28 ± 0.02 | 17.50 ± 0.09 |

CT values were expressed as the mean CT ± SE of the mean. CT, the threshold cycle number. ND, not determined. CT is the point at which the fluorescence signal rises above the base line fluorescence and begins to increase exponentially. The CT value is in logarithmic inverse relationship with the abundance of the transcripts, based on the assumption that CT values increase by ≈ 1 for each 2-fold dilution. Total RNA from the transfected cells were isolated and subjected to real-time PCR as described in Experimental Procedures. Using Fkbp1a and Fkbp8 primer sets, we determined the steady-state amounts of these transcripts present in the samples. We used β-actin as the endogenous reference to indicate similar amounts of total RNA were used in each reverse transcription and PCR

Fkbp1a was originally identified as the major cellular receptor mediating the potent suppression of T lymphocyte function produced by FK-506 or rapamycin treatment (1, 4). Therefore, we compared the effects on T lymphocyte function of Fkbp1a overexpression versus rapamycin treatment. Rapamycin treatment significantly reduced IL-2 secretion from Jurkat human T lymphocytes (Fig. 2C). In contrast, overexpression of Fkbp1a (Fig. 2D) significantly increased IL-2 secretion from Jurkat cells (Fig. 2C).

We attempted to identify the cellular mechanisms by which Fkbp1a gene expression produces its antitumor effects. FKBP gene expression does not alter tumor apoptosis or mitosis, because tumor cell apoptosis and proliferation in lung tumors obtained from B16-F10 tumor-bearing mice receiving systemic CLDC-Fkbp1a did not differ from control tumor-bearing mice (data not shown). Furthermore, there was no difference in tumor angiogenesis between tumor-bearing mice receiving systemic CLDC-Fkbp1a versus those receiving systemic CLDC-Luc (data not shown). Intravenous CLDC-based injection of genes with known antiangiogenic activities, including angiostatin and p53, each significantly reduced tumor angiogenesis in the same B16-F10 tumor model in which i.v. CLDC-based injection of the Fkbp1a gene failed to do so (12). Thus, neither tumor cell proliferation, apoptosis, nor tumor angiogenesis were altered by overexpression of Fkbp1a.

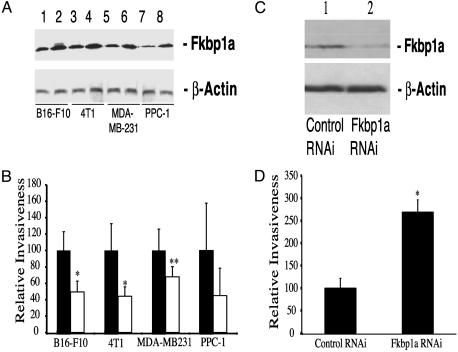

FKBP Gene Expression Reduces Tumor Cell Invasion. We then assessed whether Fkbp1a overexpression altered the ability of B16-F10 melanoma cells, 4T1 cells, human MDA-MB-231 mammary carcinoma cells, or human PPC-1 prostate cancer cells to invade the extracellular matrix (ECM). Overexpression of Fkbp1a (Fig. 3A) reduced tumor cell invasion into matrigel by ≥50% for B16-F10, 4T1, and PPC-1 cells, and by >35% for MDA-MB-231 cells (Fig. 3B). Fkbp8 overexpression inhibited invasion (P < 0.01) into matrigel at a level comparable to that produced by Fkbp1a (data not shown). Conversely, biologically active concentrations of rapamycin (0.01–1 μg/ml; ref. 7) failed to inhibit tumor cell invasion (data not shown). We then used anti-Fkbp1a-specific siRNA oligonucleotides to assess the effects of suppressing Fkbp1a gene expression on tumor invasion. The anti-Fkbp1a, but not the control siRNA, substantially reduced Fkbp1a protein levels (Fig. 3C). RNAi-mediated suppression of Fkbp1a in B16-F10 tumor cells increased their ability to invade into matrigel by 2.5-fold (P < 0.0001; Fig. 3D). Taken together, our results show that increasing Fkbp1a gene expression reduces tumor cell invasion, while suppressing Fkbp1a enhances invasion.

Fig. 3.

Increased expression of Fkbp1a or Fkbp8, but not rapamycin treatment, reduces tumor invasiveness.(A) Western blot analysis of Fkbp1a overexpression in each transfected cancer cell line. Lanes 1, 3, 5, and 7 show luciferase-transfected cells, and lanes 2, 4, 6, and 8 show Fkbp1a-transfected cells. (B) Boyden chamber invasion assay showing B16-F10, 4T1, MDA-MB231, and PPC-1 cells transfected with luciferase control (▪) or Fkbp1a (□) plasmid DNA. Data are presented as relative invasiveness, where the respective controls are set as 100% (▪). *, P < 0.05 versus luciferase control; **, P = 0.06 versus luciferase control. (C) Western blot analysis of Fkbp1a protein levels in RNAi-transfected B16-F10 cells. Lane 1, control RNAi-transfected; lane 2, Fkbp1a-targeting RNAi-transfected. (D) Boyden chamber invasion assay with B16-F10 cells transfected with control RNAi and Fkbp1a-targeting RNAi. *, P < 0.0001 versus control RNAi.

FKBP Genes Regulate a Network of Adhesion/Invasion-Related Genes. We then performed cDNA microarray analysis to characterize genes differentially expressed in B16-F10 cells by rapamycin treatment versus Fkbp1a overexpression. These studies revealed that the two interventions produced widely divergent patterns of gene expression (P = 0.1E-62; data not shown), which was consistent with the distinct antitumor pathways they mediate. We then used this analysis to identify specific genes regulated by Fkbp8 and Fkbp1a in tumor cells. Because FKBP genes reduce tumor cell invasion (Fig. 3A), we identified strongly FKBP-regulated genes that were also known to play important functional roles in cellular invasion. Syndecan 1 (Sdc1) mRNA was consistently up-regulated 4–5 fold in B16-F10 cells by either Fkbp8 or Fkbp1a gene expression, but not by rapamycin treatment (data not shown). Sdc1 protein levels were coordinately increased in Fkbp1a-transfected B16-F10 cells, whereas anti-Fkbp1a RNAi significantly reduced Sdc1 protein levels (Fig. 4A). Sdc1 blocks tumor cell invasion directly, by increasing cell adhesion to ECM (19, 20), and by inhibiting the expression of matrix metalloproteinase 9 (MMP9), which degrades ECM substrates (21, 22).

Fig. 4.

Regulation of Sdc1 and MMP9 serves as potential molecular mechanism of the antiinvasion effects produced by the FKBP proteins. (A) Regulation of Sdc1 and MMP9 by the level of Fkbp1a protein in transfected B16-F10 cells. Lane 1, no rapamycin treatment; lane 2, 1 μg/ml rapamycin treatment; lane 3, pLuc control-transfected; lane 4, pFkbp1a-transfected; lane 5, control RNAi-transfected; lane 6, Fkbp1a-targeting RNAi-transfected. Arrow indicates Fkbp1a protein with 5′HA tag. (B) Regulation of MMP9 by FKBP proteins. B16-F10-pooled populations of clones stably overexpressing Fkbp1a or Fkbp8 were compared with cells stably transduced with vector control for MMP9 protein expression. Lane 1, vector control pooled population; lane 2, Fkbp1a overexpressing pooled population; lane 3, Fkbp8 overexpressing pooled population.

B16-F10 cells overexpressing Fkbp1a demonstrated significantly reduced MMP9 protein levels, whereas RNAi-mediated suppression of Fkbp1a significantly increased MMP9 (Fig. 4A). We further confirmed FKBP mediated up-regulation of Sdc1 mRNA levels (Table 2) and down-regulation of MMP9 by stably overexpressing Fkbp1a or Fkbp8 in B16-F10 cells (Fig. 4B). Blocking MMP9 gene expression significantly reduces the metastatic spread of B16 melanoma tumors in mice (23). Several observations support the hypothesis that Fkbp8- or Fkbp1a-induced antitumor effects are mediated by inhibition of tumor cell invasion. The lack of effect on tumor apoptosis, mitosis, or angiogenesis in mice successfully treated with Fkbp1a or Fkbp8 gene transfer provides indirect evidence. Furthermore, the induction of Sdc1 and suppression of MMP9 by FKBP gene expression further supports the hypothesis that the antitumor effects produced are mediated, at least in part, by suppressing tumor invasion.

Table 2. Quantitation of Sdc1 up-regulation in B16-F10 cells stably overexpressing Fkbp1a or Fkbp8 genes.

| B16-F10 stable pool | Genes transfected | Fkbp1a, mean CT* | Fkbp8, mean CT | β-Actin, mean CT | Sdc1, mean CT | Folds up-regulation of Sdc1† |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Vector | None | 32.5 ± 0.13 | 36.7 ± 0.35 | 18.3 ± c1.14 | 25.5 ± 0.11 | 1.0 |

| Fkbp1a | Fkbp1a | 19.0 ± 0.19 | ND | 18.9 ± 0.24 | 24.7 ± 0.20 | 2.6 |

| Fkbp8 | Fkbp8 | ND | 20.0 ± 0.10 | 19.1 ± 0.13 | 25.3 ± 0.29 | 2.0 |

CT values were expressed as the mean CT ± SEM

Sdc1 up-regulation was calculated as 2ΔΔCT. ΔΔCT values were calculated as ΔCT of Vector-ΔCT of Fkbp1a or Fkbp8. ΔCT of each pool sample was calculated as Sdc1 Mean CT-β-actin mean CT of each respective sample

Discussion

Gene expression profiling studies have shown that large numbers of genes, including (i) genes known to be functionally involved in the malignant phenotype, (ii) genes with known biologic activities not previously linked to cancer, and (iii) genes with no identified function, are all aberrantly expressed in cancer (24). However, it has been difficult to determine which of these aberrantly expressed genes, particularly those with no currently identified function, actually control the metastatic spread of cancer. We combined gene expression profiling with the systemic transfer of selected cDNA microarray-identified genes to assign antimetastatic function to Fkbp8, a previously uncharacterized member of the FKBP gene family that is down-regulated in aggressive tumors. In contrast to the well characterized Fkbp1a gene, Fkbp8 neither possesses PPIase activity nor binds rapamycin (9, 10). However, based on Fkbp8's partial sequence homology with Fkbp1a, we used this same approach to show that Fkbp1a gene expression can also inhibit metastatic progression. Furthermore, antitumor activities produced by FKBP gene expression are mediated by mechanisms distinct from those induced by Fkbp1a-rapamycin binding.

Specifically, antitumor effects produced by Fkbp1a binding to rapamycin occur through the induction of cell-cycle arrest (25) and/or the inhibition of tumor angiogenesis (7), and can be associated with potent T cell-mediated immunosuppression, depending on the dosing schedule of rapamycin used (26). Conversely, antitumor effects produced by Fkbp1a gene expression appear unrelated to cell cycle or angiogenic regulation, are mediated, at least in part, by the inhibition of invasion-related pathways, and are associated with stimulation of T cell function. Binding of FAP48, a Fkbp1a-interacting protein, to Fkbp1a, also increases IL-2 production (27), documenting Fkbp1a-mediated T cell stimulation. Finally, whereas a single systemic injection of CLDC containing either the Fkbp1a or Fkbp8 gene significantly reduces the metastatic progression of 4T1 or B16-F10 tumors in mice, high-dose i.p. injections of rapamycin administered daily for 18 days failed to significantly reduce the progression of either 4T1 or B16-F10 tumors. Thus, FKBP gene expression and Fkbp1a-rapamycin binding appear to act by different pathways in tumor-bearing mice as well.

Although a number of specific genes and cellular pathways regulated by binding of Fkbp1a to rapamycin have already been identified, the downstream effects of Fkbp1a gene expression are largely uncharacterized. We initially found that Fkbp8, a member of the FKBP gene family, was significantly down-regulated by ribozyme-based suppression of NF-κB expression in a melanoma tumor cell line. Because targeting NF-κB expression significantly decreased the metastatic spread of this tumor (11), we then investigated whether overexpressing the Fkbp8 gene or the Fkbp1a gene in mice bearing this tumor line altered its metastatic progression. We found that overexpressing either Fkbp8 or the Fkbp1a significantly reduced the progression of B16-F10, as well as of 4T1 tumors in mice (Fig. 1). Overall these results indicate that the regulation of FKBP gene expression can play a significant role in mediating tumor progression in vivo.

We then used expression profiling to identify Sdc1 and MMP9 as FKBP-regulated genes that may mediate the antiinvasive effects produced by Fkbp8 or Fkbp1a gene expression. Fkbp1a gene expression strongly up-regulates Sdc1, down-regulates MMP9, and decreases tumor invasion, whereas RNAi-mediated suppression of Fkbp1a significantly down-regulates Sdc1, up-regulates MMP9, and increases tumor invasion. Sdc1, as well as MMP9, have each been shown to be functionally involved in regulating tumor invasion and tumor metastasis (28, 29). Specifically, targeted disruption of the MMP9 gene has been documented to reduce the metastatic spread of B16 melanoma tumors, as well as other cancers in MMP9 knockout mice (23). Furthermore, increased levels of Sdc1 expression in tumor biopsies is associated with a favorable prognosis in a variety of different human cancers (30–32), whereas the loss of Sdc1 expression is associated with increased aggressiveness and metastases in a number of human cancers (30, 33, 34). Therefore, the coordinate up-regulation of Sdc1 and down-regulation of MMP9 produced by Fkbp8 or Fkbp1a gene expression may play significant roles in mediating their antiinvasive and antimetastatic effects.

Aberrant expression in aggressive tumors led us to identify antimetastatic and antiinvasive effects for Fkbp8, a gene with no previously identified function (9), and subsequently for Fkbp1a. FKBP gene expression concurrently induces Sdc1 and suppresses MMP9, suggesting that a complex network of adhesion and matrix-remodeling-related genes mediate the abilities of FKBP genes to control tumor invasion and metastasis. Genome-wide expression profiling studies have revealed the genetic determinants of tumor metastasis to be extremely complex. The identification of gene regulatory networks that function to control tumor metastasis may permit more accurate modeling of the complex molecular mechanisms of this disease.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Drs. Nick Lemoine and Martin Matzuk for helpful comments, and Drs. Christina Jamieson and Caroline Mrejen of the Mouse Microarray Consortium at the University of California, San Francisco, for their support on microarray experiments. This work was supported by funds from the California Pacific Medical Center Research Institute, National Institutes of Health-R01 Grant CA 82575 (to R.J.D.), California Breast Cancer Research Program Grant 8WB-0614 (to R.J.D.), and funds from the Human Frontier of Sciences Program.

This paper was submitted directly (Track II) to the PNAS office.

Abbreviations: FKBP, FK-506-binding protein; RNAi, RNA interference; CLDC, cationic liposome:DNA complex; Sdc1, syndecan 1; MM9, matrix metalloproteinase 9.

References

- 1.Hidalgo, M. & Rowinsky, E. K. (2000) Oncogene 19, 6680-6686. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Liu, J., Farmer, J. D., Jr., Lane, W. S., Friedman, J., Weissman, I. & Schreiber, S. L. (1991) Cell 66, 807-815. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Shou, W., Aghdasi, B., Armstrong, D. L., Guo, Q., Bao, S., Charng, M. J., Mathews, L. M., Schneider, M. D., Hamilton, S. L. & Matzuk, M. M. (1998) Nature 391, 489-492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sehgal, S. N. (1995) Ther. Drug Monit. 17, 660-665. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Elit, L. (2002) Curr. Opin. Investig. Drugs 3, 1249-1253. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mita, M. M., Mita, A. & Rowinsky, E. K. (2003) Clin. Breast Cancer 4, 126-137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Guba, M., von Breitenbuch, P., Steinbauer, M., Koehl, G., Flegel, S., Hornung, M., Bruns, C. J., Zuelke, C., Farkas, S., Anthuber, M., et al. (2002) Nat. Med. 8, 128-135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Luan, F. L., Ding, R., Sharma, V. K., Chon, W. J., Lagman, M. & Suthanthiran, M. (2003) Kidney Int. 63, 917-926. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lam, E., Martin, M. & Wiederrecht, G. (1995) Gene 160, 297-302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pedersen, K. M., Finsen, B., Celis, J. E. & Jensen, N. A. (1999) Electrophoresis 20, 249-255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kashani-Sabet, M., Liu, Y., Fong, S., Desprez, P. Y., Liu, S., Tu, G., Nosrati, M., Handumrongkul, C., Liggitt, D., Thor, A. D. & Debs, R. J. (2002) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 99, 3878-3883. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Liu, Y., Thor, A., Shtivelman, E., Cao, Y., Tu, G., Heath, T. D. & Debs, R. J. (1999) J. Biol. Chem. 274, 13338-13344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wexler, H. (1966) J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 36, 641-645. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Berns, A. (2001) Nature 410, 1043-1044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bissell, M. J. & Radisky, D. (2001) Nat. Rev. Cancer 1, 46-54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tu, G., Kirchmaier, A. L., Liggitt, D., Liu, Y., Liu, S., Yu, W. H., Heath, T. D., Thor, A. & Debs, R. J. (2000) J. Biol. Chem. 275, 30408-30416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Shtivelman, E. (1997) Oncogene 14, 2167-2173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lin, P., Buxton, J. A., Acheson, A., Radziejewski, C., Maisonpierre, P. C., Yancopoulos, G. D., Channon, K. M., Hale, L. P., Dewhirst, M. W., George, S. E. & Peters, K. G. (1998) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 95, 8829-8834. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Liebersbach, B. F. & Sanderson, R. D. (1994) J. Biol. Chem. 269, 20013-20019. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Liu, W., Litwack, E. D., Stanley, M. J., Langford, J. K., Lander, A. D. & Sanderson, R. D. (1998) J. Biol. Chem. 273, 22825-22832. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Stetler-Stevenson, W. G., Aznavoorian, S. & Liotta, L. A. (1993) Annu. Rev. Cell Biol. 9, 541-573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.MacDougall, J. R., Bani, M. R., Lin, Y., Rak, J. & Kerbel, R. S. (1995) Cancer Res. 55, 4174-4181. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Itoh, T., Tanioka, M., Matsuda, H., Nishimoto, H., Yoshioka, T., Suzuki, R. & Uehira, M. (1999) Clin. Exp. Metastasis 17, 177-181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Perou, C. M., Jeffrey, S. S., van de Rijn, M., Rees, C. A., Eisen, M. B., Ross, D. T., Pergamenschikov, A., Williams, C. F., Zhu, S. X., Lee, J. C., et al. (1999) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 96, 9212-9217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Aghdasi, B., Ye, K., Resnick, A., Huang, A., Ha, H. C., Guo, X., Dawson, T. M., Dawson, V. L. & Snyder, S. H. (2001) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 98, 2425-2430. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Saunders, R. N., Metcalfe, M. S. & Nicholson, M. L. (2001) Kidney Int. 59, 3-16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Krummrei, U., Baulieu, E.-E. & Chambraud, B. (2003) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 100, 2444-2449. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Benassi, M. S., Gamberi, G., Magagnoli, G., Molendini, L., Ragazzini, P., Merli, M., Chiesa, F., Balladelli, A., Manfrini, M., Bertoni, F., et al. (2001) Ann. Oncol. 12, 75-80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Langford, J. K. & Sanderson, R. D. (2001) Methods Mol. Biol. 171, 495-503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Anttonen, A., Heikkila, P., Kajanti, M., Jalkanen, M. & Joensuu, H. (2001) Lung Cancer 32, 297-305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Numa, F., Hirabayashi, K., Kawasaki, K., Sakaguchi, Y., Sugino, N., Suehiro, Y., Suminami, Y., Hirakawa, H., Umayahara, K., Nawata, S., et al. (2002) Int. J. Oncol. 20, 39-43. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wiksten, J. P., Lundin, J., Nordling, S., Kokkola, A. & Haglund, C. (2000) Anticancer Res. 20, 4905-4907. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Fujiya, M., Watari, J., Ashida, T., Honda, M., Tanabe, H., Fujiki, T., Saitoh, Y. & Kohgo, Y. (2001) Jpn. J. Cancer Res. 92, 1074-1081. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wiksten, J. P., Lundin, J., Nordling, S., Lundin, M., Kokkola, A., von Boguslawski, K. & Haglund, C. (2001) Int. J. Cancer 95, 1-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.