Abstract

The main purpose of this study was to identify mitochondrial proteins that exhibit post-translational oxidative modifications during the aging process and to determine the resulting functional alterations. Proteins forming adducts with malondialdehyde (MDA), a product of lipid peroxidation, were identified by immunodetection in mitochondria isolated from heart and hind leg skeletal muscle of 6-, 16-, and 24-month-old mice. Aconitase, very long chain acyl coenzyme A dehydrogenase, ATP synthase, and α-ketoglutarate dehydrogenase were detected as putative targets of oxidative modification by MDA. Aconitase and ATP synthase from heart exhibited significant decreases in activity with age. Very long chain acyl coenzyme A dehydrogenase and α-ketoglutarate dehydrogenase activities were unaffected during aging in both heart and skeletal muscle. This suggests that the presence of a post-translational oxidative modification in a protein does not a priori reflect an alteration in activity. The biological consequences of an age-related decrease in aconitase and ATP synthase activities may contribute to the decline in mitochondrial bioenergetics evident during aging.

Keywords: ATP synthase, Aconitase, Aging, MDA oxidative modification, Mitochondria

The accumulation of molecular oxidative damage is suspected to be a major cause of cellular dysfunctions observed during the aging process [1] and is also a feature of age-related neurodegenerative disorders like Parkinson's [2] and Alzheimer's diseases [3,4]. The mitochondrion is a major producer and target of oxidative damage during aging. Indeed, the rate of mitochondrial superoxide/hydrogen peroxide production and the amount of oxidative damage to macromolecules such as proteins, lipids, and DNA have been shown to increase with age in a variety of species [5–7]. Post-translational oxidative modifications to proteins may play a fundamental role in the aging process because they have been shown to cause losses in structural and functional integrity and, in some cases, accelerated degradation [8,9].

A frequently observed post-translational oxidative modification is the addition of carbonyl groups to certain amino acid residues [10,11]. Protein carbonylation is an irreversible oxidative modification which tends to remain unrepaired, resulting in either removal of the protein by degradation or accumulation of the damaged or unfolded protein [11]. Reactive oxygen species (ROS), including superoxide anion, can react with unsaturated fatty acids in the lipid bilayer to generate a number of secondary products, including reactive dicarbonyl compounds like malondialdehyde (MDA). In aqueous solutions at pH 7.4, MDA principally exists as the low-reactive enolate anion. However, certain amino acid residues, such as lysine, histidine, tyrosine, arginine, and methionine, within proteins have been found to be particularly susceptible to modifications by MDA or a related condensation product [10].

While it was originally thought that oxidative damage to proteins during aging is random and ubiquitous [1], the majority of the proteins in tissue homogenates do not appear to be structurally or functionally altered during the aging process [12–15]. Nevertheless, several proteomic investigations have identified proteins involved in energy metabolism and production, stress resistance, and cellular structural integrity as targets of oxidative modification during aging [14–17]. However, the functional consequences of in vivo oxidatively damaged proteins have rarely been demonstrated or remain unclear. In fact, an oxidative modification to a protein may not necessarily correlate with any apparent functional consequence.

In the present study, mitochondrial proteins showing an MDA-induced post-translational modification have been identified and their age-related functional alterations analyzed. The rationale is that oxidized proteins, even those that do not appear to accumulate, may exhibit functional alterations with age. By assaying only mitochondrial proteins, targets of oxidation, which are obscured in whole cell homogenates, may be identified. Mitochondria from heart and skeletal muscle of relatively young (6 month), middle age (16 month), and old (24 month) mice were used, based on the obvious age-related decline in motor function apparent in mammals.

Materials and methods

Materials

All chemicals were obtained from Sigma (St. Louis, MO) unless otherwise stated. Electrophoresis supplies were purchased from Bio-Rad. Anti-malondialdehyde polyclonal, affinity-purified, antibodies were purchased from Academy Bio-Medical Company (Houston, TX).

Animals

Male C57BL/6N mice, aged 6, 16, and 24 months, were obtained from the National Institute on Aging—National Institutes of Health.

Preparations of mitochondria from heart and skeletal muscle

Mice were killed by cervical dislocation and their tissues were quickly removed and placed in ice-cold antioxidant buffer containing 50 mM potassium phosphate buffer, pH 7.4, 2 mM EDTA, and 0.1 mM butylated hydroxytoluene. For each preparation, tissues from three mice were pooled, minced, and homogenized in 10 vol.(w/v) of isolation buffer (for heart, 0.3 M sucrose, 0.03 M nicotinamide, and 0.02 M EDTA, pH 7.4; for hind leg skeletal muscle, buffer 1 containing 0.12 M KCl, 2 mM MgCl2, 1 mM EGTA, 0.5 mg/mL BSA, and 20 mM Hepes, pH 7.4, and buffer 2 containing 0.3 M sucrose, 0.1 mM EGTA, and 2 mM Hepes, pH 7.4). Low- and high-speed differential centrifugations for mitochondrial isolation were, respectively, 700g for 10 min and 10,000g for 10 min for heart and 600g for 12 min and 17,000g for 12 min in buffer 1 and 1200g for 12 min and 12,000g for 12 min in buffer 2 for skeletal muscle. Mitochondria from all tissues were isolated within 1–2 h after tissue dissection. Mitochondria were resuspended in 0.25 M sucrose for heart and in buffer 2 for skeletal muscle and frozen at −80 °C. They were disrupted by four freeze–thaw cycles.

The protein content was measured using a bicinchoninic acid protein assay kit and BSA as a standard.

Immunodetection and quantitation of MDA-modified proteins

Following 10% SDS–PAGE, proteins were transferred to a PVDF membrane, which was then blocked with 5% milk in TBST (Tris-buffered saline containing Tween 20), washed, incubated overnight at 4 °C with anti-MDA antibodies (1:20,000), washed, incubated for 1.5 hours at 37 °C with secondary antibodies (1:100,000), washed, and visualized with the ECL Plus detection system (Amersham BioSciences). Ovalbumin modified with MDA was used as the positive control. Densitometry was performed using the VersaDoc Imaging system and Quantity One software (Bio-Rad).

Identification of MDA-modified proteins

The 80, 70, and 50 kDa mouse proteins shown in Fig. 1 were identified from rat heart tissue. 50 rat hearts were purchased from Pel-freez (Rogers, AK) and mitochondria were prepared as described above for mouse tissue. Matrix and membrane fractions were prepared by sonicating three times (each consisting of a 30 s pulse) at 1 min intervals, at 4 °C. The sonicated mitochondria were centrifuged at 8250g for 10 min to remove the unbroken organelles; the supernatant was recentrifuged at 80,000g for 45 min, and the resulting pellet was resuspended in 50 mM imidazole, pH 7.0, 50 mM NaCl, and 5 mM 6-amino-n-hexanoic acid, resonicated, and recentrifuged. The matrix fractions were combined and fractionated by chromatofocusing using MonoP PBE 94 media and Polybuffer 74 as the eluent (Amersham). Fractions were then assayed for MDA-modified proteins by immunodetection, as described above. Fractions containing the 80 kDa protein were further fractionated with a Phenomenex BioSep-SEC S3000 gel filtration column and rescreened.

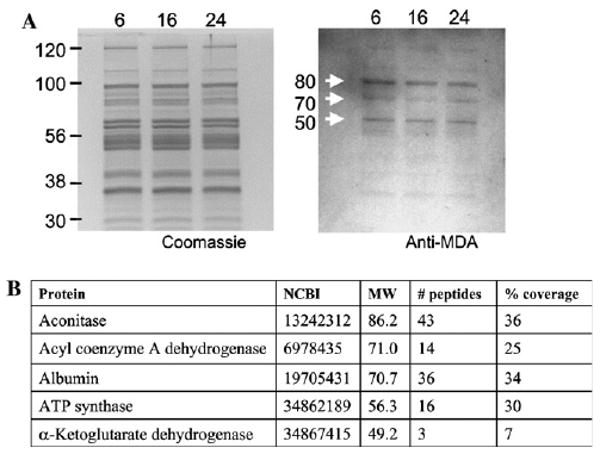

Fig. 1.

Immunodetection and identification of MDA-modified proteins in heart and skeletal muscle mitochondria from mice of different ages. (A) Heart mitochondrial proteins from 6-, 16-, and 24-month-old mice were separated by SDS–PAGE, transferred to PVDF, and probed with antibodies against MDA. Left panel, proteins stained with Coomassie blue. Right panel, blot probed with anti-MDA antibodies. (B) Identification of proteins putatively modified by MDA. NCBI refers to the accession number; MW, molecular weight.

In-gel tryptic digest, analysis of tryptic peptide sequence tags by tandem mass spectrometry, and protein identification were performed by the Proteomics Core Facility at the University of Southern California School of Pharmacy. Protein spots from SDS–PAGE corresponding to MDA-modified proteins were excised from the gel using biopsy punches (Acuderm). Coomassie blue stained bands were destained, reduced with dithiothreitol, and alkylated with iodoacetamide to decrease peptide retention in the gel after digestion and extraction, followed by in-gel tryptic digestion at 37 °C overnight using trypsin which had been reductively methylated to reduce autolysis [18] (Promega). Following an ammonium carbonate (100 mM) wash, the digestion products were extracted from the gel with a 5% formic acid/50% acetonitrile solution, which was evaporated using an APD SpeedVac (ThermoSavant). The dried tryptic digest samples were resuspended in 10 μL of 60% formic acid.

Chromatographic separation of the tryptic peptides was achieved using a ThermoFinnigan Surveyor MS-Pump in conjunction with a BioBasic-18 100 mm × 0.18 mm reverse phase capillary column (ThermoFinnigan). Mass analysis was done using a ThermoFinnigan LCQ Deca XP Plus ion trap mass spectrometer equipped with a nanospray ion source (ThermoFinnigan) employing a 4.5 cm long metal needle (Hamilton, 950-00954) using data-dependent acquisition mode. Electrical contact and voltage application to the probe tip took place via the nanoprobe assembly. Spray voltage of the mass spectrometer was set to 2.9 kV and the heated capillary temperature was 190 °C. The column equilibrated for 5 min at 1.5 μL/min with 95% A, 5% B (A, 0.1% formic acid in water; B, 0.1% formic acid in acetonitrile) prior to sample injection. A linear gradient was initiated 5 min after sample injection, ramping to 35% A, 65% B after 50 min and 20% A, 80% B after 60 min.

Protein identifications were accomplished using the MS/MS search software Mascot (Matrix Science) with confirmatory or complementary analyses using TurboSequest, as implemented in the Bioworks Browser 3.2, build 41 (ThermoFinnigan) and Sonar ms/ms (Genomics Solutions). Carbamidomethyl modification was designated as fixed (due to iodoacetamide based alkylation prior to tryptic digestion) in the Mascot search and variable modifications included methionine, histidine or tryptophan oxidation. NCBI rat genome database server complemented with the NCBI non-redundant protein database was used for searching.

Enzyme assays

All enzyme assays were conducted at 30 °C. Aconitase activity was assayed by measuring the formation of aconitate from isocitrate in a reaction mixture containing 90 mM Tris, pH 8.0, 20 mM isocitrate, and 60–100 μg of protein for skeletal muscle mitochondria or 10–25 μg of heart mitochondrial protein [19]. α-Ketoglutarate dehydrogenase complex activity was measured by the addition of mitochondrial protein, 80–110 μg for skeletal muscle or 25–65 μg for heart, to assay mixtures consisting of 50 mM potassium phosphate, pH 7.4, 0.1 mM coenzyme A, 0.2 mM thiamine pyrophosphate, 1 mM NAD+, 0.5 mM EDTA, 5 mM MgCl2, 40 μM rotenone, 0.1% Triton X-100, and 2.5 mM α-ketoglutarate [20]. Very long chain acyl coenzyme A dehydrogenase (VLCAD) activity was measured by adding 60–100 μg of skeletal muscle mitochondrial protein or 15–35 μg protein from heart mitochondria to a mixture of 100 mM potassium phosphate, pH 7.6, 0.1% Triton X-100, 20 μM palmitoyl CoA, 2 mM N-ethylmaleimide, 0.45 mM potassium cyanide, 28 μM dichlorophenol–indolphenol (DCIP), and 0.65 mM phenylmethosulfate (PMS) [21]. ATP synthase was assayed in an assay mixture consisting of 50 mM Hepes, pH 8.0, 5 mM MgSO4, 0.35 mM NADH, 250 mM sucrose, 2.5 mM phosphoenolpyruvate, 50 μg pyruvate kinase, 50 μg lactate dehydrogenase, 2 μg antimycin A, 40 μM rotenone, 2 mM potassium cyanide, 15–30 μg of skeletal muscle mitochondrial protein or 7–12 μg of heart mitochondrial protein, in the absence or presence of 3 μg oligomycin. The reaction was initiated by the addition of 2.5 mM ATP [22]. Mitochondrial ATP synthase activity was determined as the oligomycin-sensitive activity.

Enzymes were assayed in four independent preparations of heart and skeletal muscle mitochondria, each consisting of tissues pooled from three animals with three or more replicate measurements per preparation. All rates were linear with respect to enzyme concentration for the amount of protein added. Data are presented as averages ± standard error of the mean (SEM).

Results

Determination of MDA-modified proteins at different ages

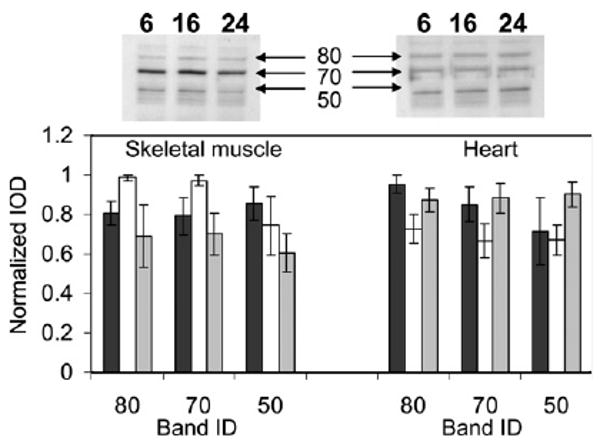

MDA-modified proteins were detected in heart and skeletal muscle mitochondria from mice of three different ages by immunostaining with anti-MDA antibodies. Three major bands, corresponding to approximately 80, 70, and 50 kDa, were evident in mice at each of the three ages, 6, 16, and 24 months (Fig. 1A). The MDA content of the protein bands was quantitated by densitometry, which showed no statistically significant, age-related differences in heart or skeletal muscle (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

Quantitation of bands immunodetected with antibodies to MDA. Top panel shows representative blots for skeletal muscle (left) and heart (right) mitochondrial proteins. The bottom panel shows the integrated optical density of the MDA-modified bands for 6- (black), 16- (white), and 24- (gray)-month-old mice. Data represent averages ± standard deviations of four independent mitochondrial preparations, each consisting of tissue pooled from three mice.

Identification of mitochondrial targets of MDA modification

To determine which mitochondrial proteins corresponded to the 80, 70, and 50 kDa targets of MDA modification in vivo (Fig. 1), pooled rat heart mitochondria were used because of the larger quantities available from rat compared to mice. Mitochondrial matrix fractions were resolved by SDS–PAGE, and MDA-modified proteins were detected with anti-MDA antibodies. The corresponding protein bands were subjected to trypsin digest and mass spectrometry analysis, and were identified as mitochondrial aconitase in the 80 kDa band, very long chain acyl coenzyme A dehydrogenase and rat albumin in the 70 kDa band, and the β-polypeptide of the mitochondrial F1 complex of ATP synthase and the E2 component of α-ketoglutarate dehydrogenase complex in the 50 kDa band. Rat albumin was likely present as a blood contaminant from the rat heart.

Determination of enzyme activity

The enzymatic activities of the proteins identified in the MDA-positive bands were determined in heart and skeletal muscle mitochondrial preparations from 6-, 16-, and 24-month-old mice. The rationale was that there may be an age-related alteration in maximal activity, even though there was no age-dependent change in MDA content in the bands.

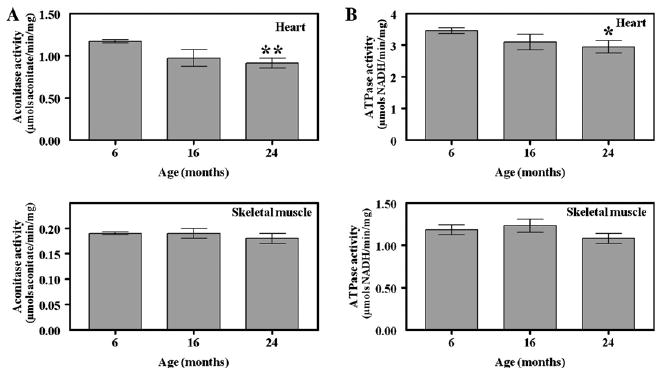

The catalytic activities of aconitase and ATP synthase were significantly altered with age in heart mitochondria. Aconitase exhibited the most significant age-related decrease in activity in the heart, approximately 20% (Fig. 3A). The maximal activity of aconitase in 16-month-old (0.97 ± 0.05 μmol aconitate/min/mg protein) and 24-month-old (0.92 ± 0.02 μmol/min/mg protein) mice was consistently lower than that from 6-month-old (1.16 ± 0.01 μmol aconitate/min/mg protein) mice. ATP synthase activity from heart also decreased significantly with age (Fig. 3B). ATP synthase activity from 24-month-old mice (2.9 ± 0.2 μmol NADH/min/mg protein) was approximately 18% lower compared to 6-month-old animals (3.4 ± 0.1 μmol NADH/min/mg). Activities of aconitase and ATP synthase in skeletal muscle were not altered with age (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3.

Aconitase and ATP synthase activities in heart and skeletal muscle mitochondria from mice of different ages. Maximal activities of aconitase (A) and ATP synthase (B) in 6-, 16-, and 24-month-old mice were determined by at least triplicate assays of four independent preparations of heart and skeletal muscle mitochondria, as described in Materials and methods. Statistically significant alterations are indicated by an asterisk, **p < 0.001, *p < 0.05 for old vs. young, based on a t test: two-sample, assuming equal variance.

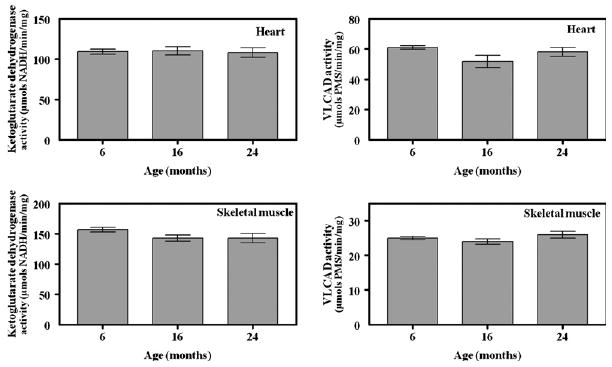

Very long chain acyl coenzyme A dehydrogenase and α-ketoglutarate dehydrogenase activities displayed no age-related change in activity in heart or skeletal muscle (Fig. 4).

Fig. 4.

α-Ketoglutarate dehydrogenase and very long chain acyl coenzyme A dehydrogenase activities in heart and skeletal muscle mitochondria from mice of different ages. Maximal activities for α-ketoglutarate dehydrogenase (A) and very long chain acyl coenzyme A dehydrogenase (B) in 6-, 16-, and 24-month-old mice were determined by at least triplicate assays of four independent preparations of heart and skeletal muscle mitochondria, as described in Materials and methods.

Discussion

This study shows that mitochondrial aconitase and ATP synthase are likely targets of MDA modification with an age-related decrease in activity in the mouse heart. It is also shown here that oxidative damage to proteins is selective and the targets are similar in both the heart and skeletal muscle, but the presence of an MDA modification does not directly confer an alteration in function. Aconitase, very long chain acyl coenzyme A dehydrogenase (VLCAD), the β-polypeptide of the mitochondrial F1 complex of ATP synthase, and the E2 component of α-ketoglutarate dehydrogenase complex were identified in protein bands showing the presence of an MDA modification in both heart and skeletal muscle mitochondria from mice of three different ages. While the amount of MDA-modified proteins did not appear to change during aging, aconitase and ATP synthase exhibited an age-related decrease in activity in heart whereas VLCAD and α-ketoglutarate dehydrogenase activities remained unchanged.

Aconitase, the citric acid cycle enzyme responsible for the interconversion of isocitrate to citrate, is known to be highly susceptible to oxidative damage [23–26] and exhibited the largest age-related decrease in activity with age (Fig. 3A). Rat heart mitochondrial aconitase has also been shown to be a target of the post-translational modification, 3-nitrotyrosine, in vivo during the normal aging process [15] and carbonylation in vitro following treatment with H2O2 [26]. Exposure to superoxide and hydrogen peroxide can oxidize the [4Fe–4S]2+ cluster of aconitase, but it was suggested that aconitase is more likely inactivated by a post-translational modification since the amount of [4Fe–4S]2+ cluster oxidation does not reflect the magnitude of enzyme inactivation [26]. Interestingly, superoxide and hydrogen peroxide did not appear to directly inhibit aconitase, instead required a membrane component responsive to peroxide [26]. It is tempting to suggest that this membrane component may be polyunsaturated fatty acids, but the membrane-sensitive inactivation of aconitase was abolished after heating the membrane component to 100 °C for 3 min [26], implying the role of a protein instead of a fatty acid. Notwithstanding, a decrease in aconitase activity is likely to affect the overall efficiency of the citric acid cycle by altering the amounts of the products of the downstream reactions in the cycle. In addition, an accumulation of citrate, an activator of fatty acid synthesis, may result from a decrease in aconitase activity.

ATP synthase, or complex V in the mitochondrial electron transport chain, also exhibited a decrease in activity with age in the mouse heart (Fig. 3B) and was identified as a putative target of oxidative modification, as shown here (Fig. 1, 50 kDa band) and in other studies [15–17]. The activity of ATP synthase has previously been shown to decrease with age in rat heart mitochondria [27,28]. Since this protein is responsible for the synthesis of ATP via oxidative phosphorylation, an age-related decrease in activity may be relevant to the decline in mitochondrial function observed with age, in particular the decrease in stamina, characteristic of aged animals.

Very long chain acyl coenzyme A dehydrogenase (VLCAD) and the E2 component of α-ketoglutarate dehydrogenase complex were also identified in protein bands positive for MDA modification (Fig. 1, 70 and 50 kDa bands, respectively) in both heart and skeletal muscle, albeit there was no apparent age-related alteration in activity in either tissue. Located in the mitochondrial matrix, α-ketoglutarate dehydrogenase complex catalyzes the irreversible oxidative decarboxylation of α-ketoglutarate in the citric acid cycle. The E2 core of α-ketoglutarate dehydrogenase is an oligomeric dihydrolipoamide succinyltransferase. While this enzyme has not been identified in previous proteomic studies identifying targets of oxidative modification, α-ketoglutarate dehydrogenase has been shown to be reversibly inactivated in rat heart mitochondria, likely by enzymatic glutathionylation and deglutathionylation [29]. VLCAD is a flavoprotein which catalyzes the initial step of mitochondrial fatty acid β-oxidation for very long chain fatty acids. This enzyme has not previously been identified as a putative target of oxidative modification, but is the basis of a genetic disorder of fatty acid metabolism, VLCAD deficiency, which can result in cardiac disease and death. Results from this study suggest that there is neither an age-related accumulation of modified protein nor alteration in activity for either enzyme.

It can be reasoned that an understanding of the mechanisms by which oxidative stress affects the aging process would be greatly facilitated by the identification of the protein targets of oxidative damage. However, as shown here, oxidative damage to proteins, though selective and even affecting the same proteins in different tissues, does not, a priori, reflect a corresponding alteration in function. Although four functionally important mitochondrial enzymes were identified as putative targets of modification by MDA, there was no apparent age-related accumulation of the modified proteins. However, there was an age-related decrease in activity for two of the enzymes. Although a few studies have successfully correlated an in vivo age-associated increase in oxidative damage with a decrease in activity for specific proteins [12,13,30,31], in most proteomic investigations, the functional consequences of the oxidative modifications were not assayed. Thus, any suggestions that the presence of an oxidative modification implies a functional consequence may be premature. Functional assays need to be performed to better define the molecular mechanisms linking oxidative stress to aging.

In summary, aconitase, very long chain acyl coenzyme A dehydrogenase, the β-polypeptide of the mitochondrial F1 complex of ATP synthase, and the E2 component of α-ketoglutarate dehydrogenase complex were identified as putative targets of MDA modification in heart and skeletal muscle mitochondria. However, only aconitase and ATP synthase exhibited an age-associated decrease in activity while α-ketoglutarate dehydrogenase and acyl coenzyme A dehydrogenase activities remained unaffected. This suggests that the presence of a post-translational oxidative modification to a protein does not necessarily reflect an alteration in activity. The biological consequences of an age-related decrease in aconitase and ATP synthase may contribute to the decline in mitochondrial bioenergetics evident during aging.

Acknowledgments

This work was funded by Grant R01 AG13563 from National Institute on Aging—National Institutes of Health. Protein identifications were performed at the Proteomics Core Facility at the University of Southern California School of Pharmacy. The authors thank Kathleen Rice for technical assistance.

Footnotes

Abbreviations: OAA, oxaloacetate; PMS, phenylmethosulfate; DCIP, dichlorophenol–indolphenol; ROS, reactive oxygen species; MDA, malondialdehyde; VLCAD, very long chain acyl coenzyme A dehydrogenase.

References

- 1.Harman D. The aging process. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1981;78:7124–7128. doi: 10.1073/pnas.78.11.7124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Koutsilieri E, Scheller C, Grunblatt E, Nara K, Li J, Riederer P. Free radicals in Parkinson's disease. J Neurol. 2002;249:1–5. doi: 10.1007/s00415-002-1201-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Butterfield DA. Amyloid beta-peptide (1-42)-induced oxidative stress and neurotoxicity: implications for neurodegeneration in Alzheimer's disease brain. A review, Free Radic Res. 2002;36:1307–1313. doi: 10.1080/1071576021000049890. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Perry G, Castellani RJ, Hirai K, Smith MA. Reactive oxygen species mediate cellular damage in Alzheimer disease. J Alzheimers Dis. 1998;1:45–55. doi: 10.3233/jad-1998-1103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Stadtman ER. Protein oxidation and aging. Science. 1992;257:1220–1224. doi: 10.1126/science.1355616. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sohal RS, Weindruch R. Oxidative stress, caloric restriction, and aging. Science. 1996;273:59–63. doi: 10.1126/science.273.5271.59. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Beckman KB, Ames BN. The free radical theory of aging matures. Physiol Rev. 1998;78:547–581. doi: 10.1152/physrev.1998.78.2.547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rivett AJ, Levine RL. Enhanced proteolytic susceptibility of oxidized proteins. Biochem Soc Trans. 1987;15:816–818. doi: 10.1042/bst0150816. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Davies KJ. Protein damage and degradation by oxygen radicals. I. General aspects. J Biol Chem. 1987;262:9895–9901. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Esterbauer H, Schaur RJ, Zollner H. Chemistry and biochemistry of 4-hydroxynonenal, malonaldehyde and related aldehydes. Free Radic Biol Med. 1991;11:81–128. doi: 10.1016/0891-5849(91)90192-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Berlett BS, Stadtman ER. Protein oxidation in aging, disease, and oxidative stress. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:20313–20316. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.33.20313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Yan LJ, Levine RL, Sohal RS. Oxidative damage during aging targets mitochondrial aconitase. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1997;94:11168–11172. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.21.11168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Yan LJ, Sohal RS. Mitochondrial adenine nucleotide translocase is modified oxidatively during aging. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998;95:12896–12901. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.22.12896. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kanski J, Alterman MA, Schoneich C. Proteomic identification of age-dependent protein nitration in rat skeletal muscle. Free Radic Biol Med. 2003;35:1229–1239. doi: 10.1016/s0891-5849(03)00500-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kanski J, Behring A, Pelling J, Schoneich C. Proteomic identification of 3-nitrotyrosine-containing rat cardiac proteins: effects of biological aging. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2005;288:H371–H381. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.01030.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Schutt F, Bergmann M, Holz FG, Kopitz J. Proteins modified by malondialdehyde, 4-hydroxynonenal, or advanced glycation end products in lipofuscin of human retinal pigment epithelium. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2003;44:3663–3668. doi: 10.1167/iovs.03-0172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Reverter-Branchat G, Cabiscol E, Tamarit J, Ros J. Oxidative damage to specific proteins in replicative and chronological-aged Saccharomyces cerevisiae: common targets and prevention by calorie restriction. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:31983–31989. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M404849200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Shevchenko A, Wilm M, Vorm O, Mann M. Mass spectrometric sequencing of proteins silver-stained polyacrylamide gels. Anal Chem. 1996;68:850–858. doi: 10.1021/ac950914h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Henson CP, Cleland WW. Purification and kinetic studies of beef liver cytoplasmic aconitase. J Biol Chem. 1967;242:3833–3838. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Robinson JB, Jr, Brent LG, Sumegi B, Srere PA. An enzymatic approach to the Krebs tricarboxylic acid cycle. In: Darley-Usmar VM, Rickwood D, Wilson MT, editors. Mitochondria: A Practical Approach. IRL Press; Washington, DC: 1987. pp. 153–169. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Davidson B, Schulz H. Separation, properties, and regulation of acyl coenzyme A dehydrogenases from bovine heat and liver. Arch Biochem Biophys. 1982;213:155–162. doi: 10.1016/0003-9861(82)90450-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ragan CI, Wilson MT, Darley-Usmar VM, Lowe PN. Subfractionation of mitochondria and isolation of the proteins of oxidative phosphorylation. In: Darley-Usmar VM, Rickwood D, Wilson MT, editors. Mitochondria: A Practical Approach. IRL Press; Washington, DC: 1987. pp. 79–112. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Verniquet F, Gaillard J, Neuburger M, Douce R. Rapid inactivation of plant aconitase by hydrogen peroxide. Biochem J. 1991;276:643–648. doi: 10.1042/bj2760643. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gardner PR, Costantino G, Szabo C, Salzman AL. Nitric oxide sensitivity of the aconitases. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:25071–25076. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.40.25071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Vasquez-Vivar J, Kalyanaraman B, Kennedy MC. Mitochondrial aconitase is a source of hydroxyl radical. An electron spin resonance investigation. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:14064–14069. doi: 10.1074/jbc.275.19.14064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bulteau AL, Ikeda-Saito M, Szweda LI. Redox-dependent modulation of aconitase activity in intact mitochondria. Biochemistry. 2003;42:14846–14855. doi: 10.1021/bi0353979. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Guerrieri F, Capozza G, Kalous M, Zanotti F, Drahota Z, Papa S. Age-dependent changes in the mitochondrial F(0)F(1) ATP synthase. Arch Gerontol Geriatr. 1992;14:299–308. doi: 10.1016/0167-4943(92)90029-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Davies SM, Poljak A, Duncan MW, Smythe GA, Murphy MP. Measurements of protein carbonyls, ortho- and meta-tyrosine and oxidative phosphorylation complex activity in mitochondria from young and old rats. Free Radic Biol Med. 2001;31:181–190. doi: 10.1016/s0891-5849(01)00576-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Nulton-Persson AC, Starke DW, Mieyal JJ, Szweda LI. Reversible inactivation of alpha-ketoglutarate dehydrogenase in response to alterations in the mitochondrial glutathione status. Biochemistry. 2003;42:4235–4242. doi: 10.1021/bi027370f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Viner RI, Ferrington DA, Williams TD, Bigelow DJ, Schoneich C. Protein modification during biological aging: selective tyrosine nitration of the SERCA2a isoform of the sarcoplasmic reticulum Ca2+-ATPase in skeletal muscle. Biochem J. 1999;340:657–669. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Das N, Levine RL, Orr WC, Sohal RS. Selectivity of protein oxidative damage during aging in Drosophila melanogaster. Biochem J. 2001;360:209–216. doi: 10.1042/0264-6021:3600209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]