Abstract

Wild-type p53-induced phosphatase (Wip1) is induced by p53 in response to stress, which results in the dephosphorylation of proteins (i.e. p38 MAPK, p53, and uracil DNA glycosylase) involved in DNA repair and cell cycle checkpoint pathways. p38 MAPK-p53 signaling is a unique way to induce Wip1 in response to stress. Here, we show that c-Jun directly binds to and activates the Wip1 promoter in response to UV irradiation. The binding of p53 to the promoter occurs earlier than that of c-Jun. In experiments, mutation of the p53 response element (p53RE) or c-Jun consensus sites reduced promoter activity in both non-stressed and stressed A549 cells. Overexpression of p53 significantly decreased Wip1 expression in HCT116 p53+/+ cells but increased it in HCT116 p53−/− cells. Adenovirus-mediated p53 overexpression greatly decreased JNK activity. Up-regulation of Wip1 via the p38 MAPK-p53 and JNK-c-Jun pathways is specific, as demonstrated by our findings that p38 MAPK and JNK inhibitors affected the expression of the Wip1 protein, whereas an ERK inhibitor did not. c-Jun activation occurred much more quickly, and to a greater extent, in A549-E6 cells than in A549 cells, with delayed but fully induced Wip1 expression. These data indicate that Wip1 is activated via both the JNK-c-Jun and p38 MAPK-p53 signaling pathways and that temporal induction of Wip1 depends largely on the balance between c-Jun and p53, which compete for JNK binding. Moreover, our results suggest that JNK-c-Jun-mediated Wip1 induction could serve as a major signaling pathway in human tumors in response to frequent p53 mutation.

Keywords: JNK, p38 MAPK, p53, PP2C, Protein Phosphatase, Wip1

Introduction

As a master cell regulator, p53 activates genes involved in DNA repair, cell cycle control, and apoptosis to mediate cellular responses to agents that cause stress and DNA damage (1, 2). Wild-type p53-induced phosphatase 1 (Wip1)2 is a recently identified member of the protein phosphatase type 2C and p53 target gene families (3, 4). Once induced by p53, Wip1 directly dephosphorylates checkpoint kinase 1 (Chk1), checkpoint kinase 2 (Chk2), p38 MAPK, uracil DNA glycosylase, ataxia-telangiectasia-mutated (ATM) kinase, mdm2, and p53, so that cells can return to normal after DNA repair (5–9).

The Wip1 gene is frequently amplified or overexpressed in human cancers, including ∼11% to 16% of breast cancers, 40% of ovarian clear cell adenocarcinomas, 40% of neuroblastomas, and 36% of pancreatic cancers, which rarely contain the p53 mutation (10–14). Overexpressed Wip1 promotes tumor growth by switching off major checkpoint kinases and p53; facilitates cell proliferation; and transforms primary fibroblasts together with Ras, Myc, and Neu (15). Wip1 can promote unrestricted entry into the cell cycle in response to DNA damage via dephosphorylation of ATM/ATR and p38 MAPK through a mechanism similar to that used by protein phosphatase 5 and protein phosphatase 1 (16–18). Wip1-null mouse embryonic fibroblast (MEF) cells exhibit increased expression of p53, p21, p16, and p19; severe proliferation defects; and vulnerability to replicative senescence (19, 20). Although the exact mechanism by which Wip1 controls the cell cycle is unknown, Wip1 likely plays a conserved role in the progression of the normal cell cycle in eukaryotic cells.

The search for a Wip1-specific chemical inhibitor has been undertaken by Belova et al. and Rayter et al. (21, 22). A major factor influencing the use of Wip1 as a therapeutic target is that loss of Wip1 promotes apoptosis in response to external stresses. Wip1−/− MEF cells exhibit increased caspase-3 and PARP cleavage and sustained activation of p38 MAPK and c-Jun N-terminal kinase (JNK), whereas wild-type MEF cells exhibit strong G2/M arrest upon etoposide treatment (23). Thus, p53 activation is necessary; however, the p53 downstream target, Wip1, should not be activated in cancer therapies.

Mitogen-activated protein kinases (MAPKs), including extracellular signal-regulated kinase (ERK), JNK, and p38 MAPK, are involved in cell proliferation, growth, and apoptosis (24, 25). During a search for p53-dependent, stress-activated proteins, the p38 MAPK-p53 pathway was the first system identified as mediating Wip1 induction (3). However, the exact mechanism by which p53 activates the Wip1 promoter has not been clearly determined. Very recently, Rossi et al. (26) identified a p53 response element (p53RE) within the Wip1 promoter. Han et al. (27) showed that Wip1 induction involves estrogen response elements in the Wip1 promoter when Wip1 is induced by the estrogen receptor α pathway, and that Wip1 facilitates cell cycle progression in a phosphatase activity-dependent manner. These findings indicate that Wip1 is regulated by multiple pathways.

In response to DNA damage, JNK is activated and translocated to the nucleus, where it phosphorylates c-Jun. Phosphorylated c-Jun forms a homodimer or a heterodimer with members of the activator protein-1 family, including JunD, activating transcription factor-2 (ATF-2) and ATF-3, which are also phosphorylated by JNK. This complex then transactivates a wide variety of proteins, including pro-apoptotic factors (28, 29). In non-stressed cells, JNK binds to p53 or c-Jun, resulting in their ubiquitination and subsequent degradation. Overexpression of c-Jun stabilizes p53 by squelching JNK because c-Jun competes with p53 for JNK binding (30–32). Conversely, JNK phosphorylates and activates the p53 and c-Jun proteins in stressed cells. Pre-expression of a temperature-sensitive p53 mutant inhibits UV-induced apoptosis via the association of p53 with JNK and the subsequent suppression of JNK signaling (30). In the present study, we report that Wip1 is regulated by the JNK-c-Jun pathway in addition to the p38 MAPK-p53 pathway. c-Jun directly binds to and activates the Wip1 promoter, which occurs later in time than p53 binding following DNA damage. In our experiments, Wip1 expression was greatly decreased by mutation of the p53 or c-Jun consensus binding sites. However, overexpression of p53 decreased Wip1 promoter activity via the p53-inhibited JNK-c-Jun pathway by competing with c-Jun for activation. c-Jun substitutes for p53 function in p53-deficient cells. Our results show that the JNK-c-Jun pathway can induce Wip1 expression in the absence of p53, and it does so perhaps more frequently than the p38 MAPK-p53 pathway because of the high (i.e. ∼50%) frequency of p53 mutation in human tumors.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Materials

The JNK inhibitor (SP600125) was obtained from Calbiochem (420119; La Jolla, CA). The ERK inhibitor (U0126) and the p38 MAPK inhibitor (SB202190) were purchased from Sigma (U120; S7067). All stock solutions were prepared in dimethyl sulfoxide. For siRNA experiments, c-Jun-specific siRNA and unrelated scrambled control siRNA were obtained from Santa Cruz Biotechnology (sc-44201; Santa Cruz, CA) and from Dharmacon Research (D-001210-01-05; Lafayette, CO), respectively.

Cell Culture and Treatments

Lung carcinoma (A549) cells were grown in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (DMEM) (Invitrogen), whereas human colorectal carcinoma (HCT116 p53+/+ and HCT116 p53−/−) cells were cultured in RPMI 1640 (Invitrogen) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum, 50 μg/ml penicillin, and 100 μg/ml streptomycin. MEFs (c-Jun+/+ and c-Jun−/−) (33) were cultured in DMEM (Invitrogen) containing 2 mm Glutamax-1 and 1% MEM nonessential amino acid. For UV irradiation experiments, the culture medium was aspirated, exposed to 50 J/m2 UV-C light (XL1000; Spectronics Corporation, Westbury, NY), and immediately returned to the cultured cells.

Quantitative Real-time Reverse Transcription-PCR (qRT-PCR)

Total RNA was isolated using the NucleoSpin RNA II kit (740955; Macherey-Nagel, Düren, Germany). First-strand cDNA was synthesized from 1 μg of total RNA using the SuperScriptTM II enzyme (18064-014; Invitrogen). PCR amplification was performed using SYBR Green (S7563; Invitrogen) on a Bio-Rad iQ5 machine (Bio-Rad). The following primer set was used to amplify Wip1 (GenBankTM accession no. NM_003620.2): forward, 5′-GCCAGAACTTCCCAAGGAAAG-3′; reverse, 5′-GGTTCAGGTGACACCACAAATTC-3′, which produces a 230-bp amplicon. The amplification protocol consisted of an initial denaturation step at 95 °C for 5 min, followed by 25 cycles at 94 °C for 15 s, 60 °C for 30 s, and 72 °C for 30 s, followed by a final extension step at 72 °C for 7 min. A melting curve analysis was performed for each run to confirm the specificity of amplification and the lack of primer dimmers. Ct values were determined using Bio-Rad iQ5 2.0 Standard Edition Optical System Software V2.0.

Plasmid Construction

The 5′-flanking region of the human Wip1 promoter (accession no. RP11–634F5; spanning nucleotides −543 to +10, with numbering initiated at the position of the translation start site) was amplified using primers 5′-GGGCTCGAGTAAGAACGCTGGACTGAGCCAA-3′ (forward) and 5′-GGGAAGCTTGGCCGGCTGGCCGGGATCCC-3′ (reverse). The PCR products were digested with XhoI and HindIII and cloned into the pGL3-basic vector (Promega, Madison, WI) to obtain the Wip1–543-Luc construct. Two mutations for the p53 and c-Jun binding sites were introduced using the QuikChange mutagenesis kit II (210518; Stratagene, West Cedar Creek, TX) and the following primer pairs containing each mutation (consensus sites are underlined, and mutated sequences are in lowercase): Wip1-c-Jun-mut, 5′-GCCGAGTGACGTtgGCGGGGGAGAAC-3′ (sense) and 5′-GTTCTCCCCCGCcaACGTCACTCGGC-3′ (antisense); Wip1-p53-mut, 5′-GGCGCTCCGGCaCAaCTCTCGCGGAtAAcTCCAGACATCGCG-3′ (sense) and 5′-CGCGATGTCTGGAgTTaTCCGCGAGAGtTGtGCCGGAGCGCC-3′ (antisense).

Transfection and Luciferase Reporter Assays

Cell were seeded on 12-well plates and transfected in Opti-MEM (11058-021; Invitrogen) for 4 h in the presence of different expression plasmids, 0.5 μg of a p53RE-containing reporter plasmid (p53-induced Luc; Stratagene) or Wip1–543-Luc, 0.01 μg of a Renilla luciferase vector (Promega) using the Lipofectamine 2000 (11668-019; Invitrogen), or NeonTM Transfection System (MPK5000; Invitrogen). Between 18- and 24-h post-transfection, cells were exposed to UV irradiation (50 J/m2). Cells were harvested, and firefly luciferase activity was measured in three independent experiments. Data were normalized to Renilla luciferase activity.

Electrophoretic Mobility Shift Assay (EMSA)

Nuclear extracts were prepared from A549 cells as described by Han et al. (27). Eight micrograms of nuclear extracts were preincubated for 10 min at room temperature with 5× binding buffer (20% glycerol, 5 mm MgCl2, 2.5 mm EDTA, 250 mm NaCl, 50 mm Tris-HCl, pH 7.5, and 0.25 mg/ml poly(dI-dC). This was followed by a 30-min incubation in a 20-μl reaction solution containing 3 μl of 10,000 cpm of 32P-labeled probes complementary to the c-Jun-specific oligonucleotides of GTGACGTCAGC in the Wip1 promoter. Complexes were analyzed on 6% nondenaturing polyacrylamide gels. For supershift assays, phospho-c-Jun (Ser-73; 9164; Cell Signaling Technology, Beverly, MA), the binding reaction was incubated with antibodies for 2 h prior to the addition of the radiolabeled probes. For competition experiments, the nuclear extracts were preincubated for 10 min in the presence of 1-fold, 10-fold, or 100-fold excess of unlabeled double-stranded oligonucleotides as follows: wild-type c-Jun, 5′-AGAGAGCCGAGTGACGTCAGCGGGGGAGAA-3′; mutated c-Jun, 5′-AGAGAGCCGAGTGACGTtgGCGGGGGAGAA-3′ (c-Jun consensus sites are underlined, and mutated sites are in lowercase).

Chromatin Immunoprecipitation (ChIP) Assay

Approximately 106 cells were placed onto 10-cm plates, exposed to UV irradiation and incubated for various times after cross-linking. ChIP assays were performed using c-Jun antibody (sc-44; Santa Cruz Biotechnology) or p53 antibody (05-224; Upstate, Charlottesville, VA). Immunoprecipitated DNA was analyzed by PCR using oligonucleotides spanning the c-Jun binding site, 5′-GGGGAAGCAAACTAGGAGATG-3′ (forward) and 5′-ACACAAATCAGGCGTTCTCC-3′ (reverse), and the p53 binding site, 5′-GGAGAACGCCTGATTTGTGT-3′ (forward) and 5′-GCCGGCCAACTATTGTTTAT-3′ (reverse). The GAPDH gene was used as an internal control using the following oligonucleotides: 5′-TACTAGCGGTTTTACGGGCG-3′ (forward) and 5′-TCGAACAGGAGGAGCAGAGAGCGA-3′ (reverse). IgG antibodies (12371B; Upstate) were used as a negative control.

Western Blot Analysis

Cells were lysed for 30 min at 4 °C using radioimmune precipitation assay lysis buffer (50 mm Tris-HCl, pH 8.0, 150 mm NaCl, 0.5 mm EDTA, 1 mm dithiothreitol, 0.1% SDS, and 1% Nonidet P-40) containing protease inhibitor mixture (BP-477; Boston BioProducts, Worcester, MA) and cleared by centrifugation at 13,000 rpm and 4 °C. Protein samples (30 μg or 50 μg) were electrophoretically separated on 8% to 12% SDS-PAGE gels and transferred onto polyvinylidene difluoride membranes. Blots were incubated in the presence of antibodies specific to Wip1 (AP8437b; ABGENT, San Diego, CA), p53 (05-224; Upstate), phospho-p53 (Ser-46; 2521; Cell Signaling Technology), JNK (06–748; Upstate), phospho-JNK (Thr-183/Tyr-185; 9251; Cell Signaling), c-Jun (sc-44; Santa Cruz Biotechnology), phospho-c-Jun (Ser-73; 9164; Cell Signaling Technology), p38 (clone 2F11; 05-454; Upstate), phospho-p38 (Thr-180/Tyr-182; 4631; Cell Signaling Technology), and β-actin (A5441; Sigma). Blots were developed using the SuperSignal West Pico Chemiluminescent Substrate (34080; Pierce). An image quantitation analysis was performed with Kodak Molecular Imaging Software Version 4.0 (no. 81906768; Kodak, Rochester, NY).

JNK Activity Assay

JNK assays were performed according to the protocol provided by Cell Signaling Technology. Protein lysates (300 μg of total protein) were mixed with beads containing 2 μg of c-Jun fusion protein (9811; Cell Signaling Technology) and incubated with gentle rocking at 4 °C for 16 h. The beads were washed twice with 500 μl of cell lysis buffer (9803; Cell Signaling Technology) and twice with 500 μl of kinase buffer (9302; Cell Signaling Technology). Kinase reactions were then performed in the presence of 200 μm ATP at 30 °C for 30 min. The phosphorylated c-Jun fusion protein was detected by immunoblot analysis using the phospho-c-Jun (Ser-73) antibody (9164; Cell Signaling Technology).

Statistics

Values represent means ± S.D. (n = 3 or 4). Comparisons between groups were analyzed using two-tailed Student's t tests. Statistical significance is shown by asterisks (*), indicating p < 0.05.

RESULTS

c-Jun Enhances Wip1 Expression in Response to UV Irradiation

Wip1 was initially identified as a p53-dependent stress-activated protein, but the p53 response site was not identified until very recently. Considering that Wip1 functions as a homeostatic regulator of DNA damage, we reasoned that Wip1 expression might be controlled by other stress-activating signals. We searched the regulatory region of the Wip1 gene using the Transcription Element Search System program (34) and identified the c-Jun consensus site between nucleotides −284 and −274 (GTGACGTCAGC), with numbering beginning from the position of the translation start site.

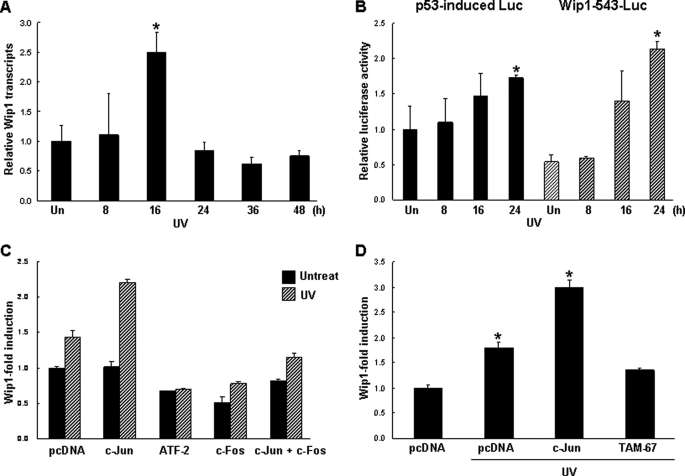

To determine whether c-Jun plays a role in Wip1 expression, we used qRT-PCR to examine Wip1 induction in response to UV irradiation, one of the major stresses that activates the JNK pathway. Wip1 transcripts slowly increased in A549 cells, reaching a maximum 16 h after irradiation and then rapidly decreased (Fig. 1A). Promoter activity in the presence of Wip1–543-Luc, which contains the 5′-flanking region of the human Wip1 promoter (spanning nucleotides −543 to +10), demonstrated that the induced luciferase activity was comparable with that of a known p53-induced gene (Fig. 1B). To examine the role of c-Jun in the regulation of Wip1, we analyzed Wip1 promoter activity following co-transfection of c-Jun, ATF-2, c-Fos, and the combination of c-Jun and c-Fos with the Wip1–543-Luc construct. Transcriptional Wip1 promoter activity increased significantly in cells transfected with c-Jun; in contrast, ATF-2, c-Fos, and the combination of c-Jun and c-Fos did not activate the Wip1 promoter (Fig. 1C). To confirm c-Jun-mediated Wip1 induction, we performed a luciferase assay following the transient expression of a c-Jun mutant expressing the DNA binding domain without the transactivation domain (TAM-67) (33). As shown in Fig. 1D, overexpression of the c-Jun mutant did not enhance Wip1 induction compared with wild-type c-Jun. Rather, the mutant lowered Wip1 promoter activity slightly relative to the control. Together, these data suggest that Wip1 is positively regulated by c-Jun.

FIGURE 1.

c-Jun binds to and activates the Wip1 promoter in A549 cells. A, Wip1 mRNA transcripts were analyzed via qRT-PCR after UV irradiation (50 J/m2) for the indicated times. Data indicate the level of Wip1 transcripts relative to a control gene, GAPDH. The mean of three experiments is shown in each column, and bars correspond with the S.D. B, cells were transfected with the Wip1 reporter plasmid Wip1–543-Luc or the p53RE-containing reporter plasmid (p53-induced Luc, as a control), together with a Renilla luciferase vector. After 8, 16, or 24 h of UV irradiation, luciferase activity was measured and normalized to control Renilla luciferase units. C, Wip1–543-Luc constructs were co-transfected with the control plasmid, ATF-2, c-Jun, or a combination of c-Jun and c-Fos. After 48 h of UV irradiation, Wip1 promoter activity was determined as described in B. D, cells were co-transfected with Wip1–543-Luc and the control plasmid, c-Jun, or a transactivation domain-deficient c-Jun mutant (TAM-67) and subjected to UV irradiation. After 48 h, cell extracts were assayed for luciferase activity. The mean of three experiments is shown in each column, and bars correspond with the S.D. *, p < 0.05, according to a two-tailed Student's t test.

c-Jun Binds Directly to the Wip1 Promoter

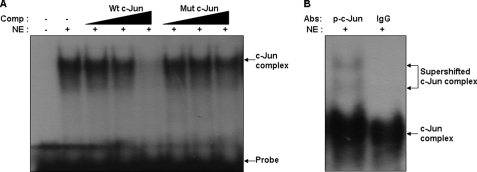

To further examine the role of c-Jun at the Wip1 promoter, we performed EMSA using nuclear lysates prepared from UV-irradiated A549 cells. This was done to assess the association of c-Jun with synthetic oligonucleotides containing the c-Jun consensus site. We identified a shifted band (shown in Fig. 2A). The shifted band was reduced or completely eliminated by the addition of a 1-fold, 10-fold, or 100-fold molar excess of the same unlabeled c-Jun consensus DNA (Fig. 2A, lane 5). In contrast, mutated oligonucleotides were unable to out-compete the complexes (Fig. 2A, lane 8). The shifted complex was supershifted by the addition of an anti-c-Jun phosphorylation-specific antibody (Fig. 2B).

FIGURE 2.

c-Jun binds to the Wip1 promoter after UV irradiation in vitro. A, EMSA was performed using a 32P-labeled wild-type oligonucleotide containing the c-Jun binding site on the Wip1 promoter. The EMSA was performed using A549 nuclear extracts (NEs) prepared after 6 h of UV irradiation (50 J/m2). Competition assays were performed using 1-fold, 10-fold, and 100-fold molar excesses of cold wild-type (wt) or mutant (mt) oligonucleotides. B, for supershift assays, phospho-c-Jun (Ser-73) or control IgG antibodies (1 μg) were preincubated with the nuclear extracts.

c-Jun and p53 Compete to Interact with the Wip1 Promoter

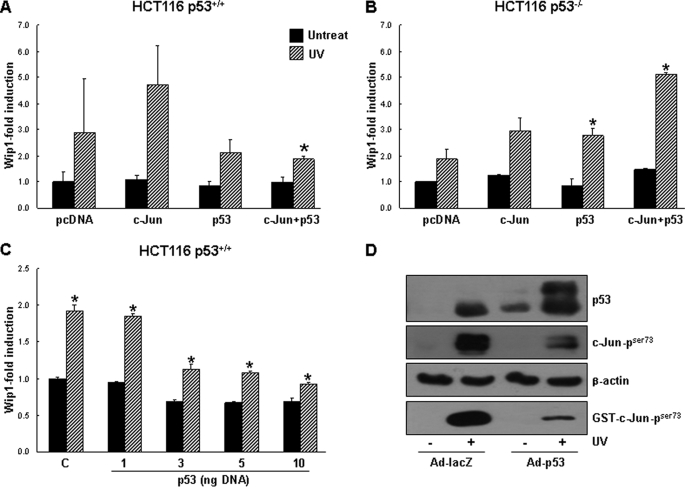

JNK phosphorylates and activates p53 and c-Jun in response to UV-induced damage (35–37). To examine the roles of c-Jun and p53 in the regulation of Wip1, we transfected c-Jun and p53, both individually and together, into HCT116 cells and assayed the cells for Wip1 induction. Unexpectedly, the results showed that c-Jun overexpression significantly increased Wip1 promoter activity, whereas p53 decreased Wip1 promoter activity slightly relative to basal- and UV-activated levels. The co-transfection of c-Jun and p53 resulted in a 3-fold reduction in Wip1–543-Luc activity compared with transfection of c-Jun alone (Fig. 3A). Next we performed the same experiments on HCT116 p53−/− cells. We found that p53 and c-Jun each enhanced Wip1 induction and that the combination of p53 and c-Jun synergistically up-regulated Wip1 promoter activity (Fig. 3B). To explore this discrepancy, we transfected HCT116 cells with increasing levels of p53-expressing plasmids. As shown in Fig. 3C, p53 overexpression inhibited Wip1 promoter activity in a dose-dependent manner. Based on the data, we hypothesized that the different cellular responses might be attributable to competition between p53 and c-Jun for JNK binding. We further tested the effects of p53 overexpression on the JNK-c-Jun pathway using p53-encoding adenoviruses in HCT116 p53+/+ cells. Solid-phase kinase assays of Ad-lacZ-infected controls cells revealed that endogenous c-Jun and GST-c-Jun were increasingly phosphorylated in response to UV irradiation; however, in Ad-p53-infected cells, the phosphorylation of c-Jun proteins had markedly decreased (Fig. 3D). These observations suggest that both c-Jun and p53 up-regulate Wip1 expression and that predominant p53 activity leads to an overall reduction in Wip1 expression due to the inhibition of c-Jun.

FIGURE 3.

p53 overexpression inhibits the Wip1 promoter. A and B, HCT116 p53+/+ and HCT116 p53−/− cells were transfected with Wip1–543-Luc having plasmids encoding c-Jun, p53, or a combination of the two proteins for 24 h. Cells were then exposed to UV irradiation (50 J/m2). Luciferase activity was measured after 48 h. C, HCT116 p53+/+ cells were co-transfected with Wip1–543-Luc and the indicated amount of a p53-encoding plasmid for 24 h. The total amount of transfected DNA was normalized to that of an empty plasmid. After 48 h of UV irradiation, luciferase activity was measured. The mean of three experiments is shown in each column, and bars correspond with the S.D. *, p < 0.05. D, HCT116 p53+/+ cells were infected with a control adenovirus encoding LacZ or an adenovirus encoding p53 at an MOI of 50 for 8 h and then exposed to UV irradiation. Then 16 h later, the cells were subjected to in vitro kinase assays with GST-c-Jun and immunoblot analysis using antibodies specific to p53 and phospho-c-Jun (Ser-73).

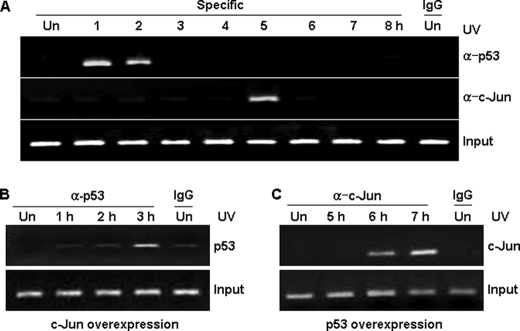

p53 and c-Jun Bind to the Wip1 Promoter in a Time-dependent Manner

To investigate the hypothesis that p53 and c-Jun compete to activate the Wip1 promoter, we performed a ChIP assay on UV-irradiated A549 cells. Note that c-Jun and p53 bound to the promoter in a time-dependent manner: p53 bound to the Wip1 promoter within 1 h, whereas the interaction between c-Jun and the Wip1 promoter reached a peak 5 h after irradiation (Fig. 4A). c-Jun overexpression resulted in a delay of 1 to 3 h in p53 binding time; conversely, p53 overexpression delayed c-Jun binding time (Fig. 4, B and C). These data suggest that Wip1 is sequentially activated by two pulses, the first is by immediate p53 activation, and the second is by c-Jun, and that overexpression of either p53 or c-Jun inhibits the activity of the other protein.

FIGURE 4.

c-Jun and p53 regulate Wip1 expression in a time-dependent manner. A, ChIP analysis of p53 and c-Jun binding to the Wip1 promoter was performed in A549 cells. After exposure to UV irradiation for the indicated times, cells were prepared for ChIP with p53, c-Jun, or control IgG antibodies. B and C, A549 cells were transiently transfected with vectors encoding c-Jun or p53 for 24 h, then exposed to UV irradiation (50 J/m2). Cells were processed for ChIP with p53 or c-Jun antibodies after the exposure to UV irradiation for the indicated times.

c-Jun and p53 Binding Activity Is Essential for Wip1 Induction

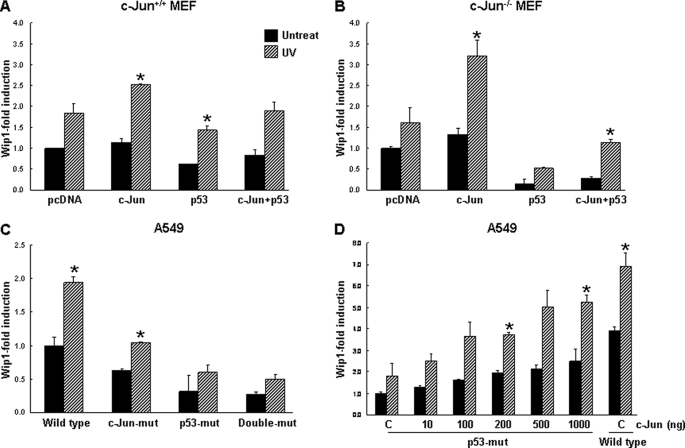

To investigate whether Wip1 is induced in the absence of c-Jun, we measured Wip1 promoter activity in c-Jun+/+ and c-Jun−/− MEF cells. Wip1 was induced in response to UV without endogenous c-Jun, but enhanced by c-Jun transient expression and inhibited by p53 overexpression, in c-Jun+/+ MEF cells. This was clearer in c-Jun−/− cells: Wip1 promoter activity was increased up to ∼2.2-fold by the transfection of c-Jun and was completely blocked by p53 overexpression (Fig. 5, A and B). To further determine the contribution of p53 and c-Jun to Wip1 induction, we mutated the c-Jun and p53RE sites and assessed the effects in A549 cells. Mutation of the p53RE and c-Jun consensus sites markedly reduced Wip1–543-Luc activity, by ∼70 and 50%, respectively. Double deletion of the c-Jun and p53RE consensus sites further reduced Wip1-luciferase activity by ∼78% (Fig. 5C). Next we assessed whether c-Jun rescues Wip1 expression in p53RE-mutated Wip1 promoter. p53RE-mutated promoter activity was enhanced together with an increase in c-Jun and reached ∼80% of the wild-type Wip1 promoter activity (Fig. 5D). These results suggest that although both p53 and c-Jun binding sites are required for full Wip1 promoter activity, c-Jun can substitute for p53 in p53-deficient cells.

FIGURE 5.

c-Jun can substitute for p53 function in Wip1 expression. A and B, embryo fibroblasts of c-Jun+/+ and c-Jun−/− were transfected with Wip1–543-Luc encoding plasmids of c-Jun, p53, or a combination of the two proteins for 24 h. Fibroblasts were then exposed to UV irradiation (50 J/m2). Luciferase activity was measured after 48 h. C, A549 cells were transfected for 24 h with Wip1–543-Luc, Wip1-c-Jun-mut (i.e. containing a mutated c-Jun binding site), Wip1-p53-mut (i.e. containing a mutated p53RE binding site), or double-mut (i.e. containing mutated c-Jun and p53 RE binding sites) and then exposed to UV irradiation. After 48 h, luciferase assays were performed. D, A549 cells were transfected with Wip1-p53-mut with increasing amounts of c-Jun-encoding plasmids (10, 100, 200, 500, and 1000 ng) or Wip1–543-Luc as a control and then assayed as described in C. The mean of three experiments is shown in each column, and bars correspond with the S.D. *, p < 0.05.

The Roles Played by p38 MAPK and JNK at the Wip1 Promoter Are Specific for UV Stress

Although p38 MAPK-p53 was the first reported pathway of Wip1 induction, signaling by other MAPKs, ERK1/2, and JNK plays a role in the induction of activator protein-1, cell proliferation, and apoptosis. For example, c-Jun is activated by JNK alone, whereas ATF2 is activated by the combination of p38 MAPK and c-Jun (38). We therefore examined the specificity of JNK-c-Jun-mediated Wip1 induction in response to UV irradiation. A549 cells were transfected with Wip1–543-Luc and treated with the JNK inhibitor SP600125, the ERK inhibitor U0126, or the p38 MAPK inhibitor SB202190. Results revealed that SP600125 and SB202190 reduced Wip1 promoter activity 2-fold, whereas U0126 did not interfere with Wip1 expression (Fig. 6A). To further confirm these findings at the level of protein expression, we measured JNK and p38 MAPK expression via Western blot analysis. As expected, pretreatment with the JNK and p38 MAPK inhibitors for 1 h decreased Wip1 protein expression, whereas the ERK inhibitor had no effect on the level of Wip1 protein. Note that the JNK inhibitor SP600125 also decreased p53 phosphorylation (Fig. 6B). Finally, we used siRNA to assess the role of c-Jun in the regulation of Wip1 expression. Cells transfected with c-Jun siRNA showed significantly decreased Wip1 expression compared with control siRNA-transfected cells (Fig. 6C).

FIGURE 6.

MAPKs specifically activate Wip1 expression. A, A549 cells were transfected with Wip1–543-Luc and then pretreated for 1 h with the JNK-specific inhibitor SP600125 (20 μm), the ERK-specific inhibitor U0126 (10 μm), or the p38-specific inhibitor SB202190 (20 μm). After 48 h of UV irradiation, cell extracts were assayed for luciferase activity. The mean of three experiments is shown in each column, and bars correspond with the S.D. *, p < 0.05. B, A549 cells were pretreated with MAPK inhibitors as described in A and then exposed to UV irradiation. After 48 h, total cell lysates were prepared and subjected to immunoblotting assays using p53, phospho-p53 (Ser-43), c-Jun, phospho-c-Jun (Ser-73), and Wip1 antibodies. β-Actin was used as the loading control. C, A549 cells were transfected with either c-Jun siRNA or control siRNA for 48 h and exposed to UV irradiation. The cells were cultured for 24 h and subjected to immunoblotting assays using antibodies specific to c-Jun, phospho-c-Jun (Ser-73), Wip1, and β-actin. β-Actin was used as a loading control.

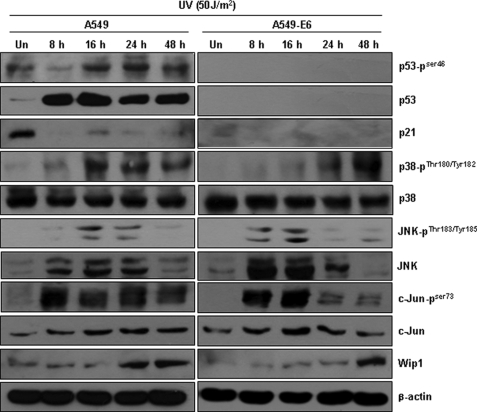

Wip1 Induction Is Delayed in the Absence of p53

To determine whether p53 or JNK is the major inducer of Wip1 in response to UV irradiation, we examined JNK pathway activation and Wip1 protein expression in A549 (p53 wild-type) and A549-E6 (p53 non-function) cells. As shown in Fig. 7, the p53 and JNK pathways were activated concomitantly 8 h after irradiation. However, JNK activation and subsequent c-Jun activation occurred earlier and to a greater extent in A549-E6 cells than in A549 cells. Wip1 induction was noticeably delayed but ultimately reached a similar level as that attained in A549 cells. These results imply that although c-Jun and p53 compete to up-regulate Wip1 induction, complete inhibition of p53 may allow for ample Wip1 expression via full induction by the JNK-c-Jun pathway. Thus, JNK appears to compensate for p53.

FIGURE 7.

Wip1 is induced in both A549 (p53+/+) and A549-E6 (p53-null phenotype) cells. A549 (left) and A549-E6 (right) cells were exposed to UV irradiation (50 J/m2) and harvested at the times indicated. Western blot analysis was performed using specific antibodies against phosphorylated JNK, c-Jun, p38, p21, and Wip1. Expression of β-actin is shown as a loading control.

DISCUSSION

Ever since Wip1 was identified as a p53-regulated gene, p38 MAPK-p53 signaling has been regarded as a unique way to induce Wip1 in response to stress (3). Here we report that c-Jun directly binds to the Wip1 promoter in response to UV irradiation and up-regulates promoter activity via the JNK-c-Jun pathway, through a mechanism similar to that used by p53. The p38 MAPK-p53 and JNK-c-Jun pathways appear to compete to activate Wip1. The two pathways activate the Wip1 promoter in a time-dependent manner: p53 binds immediately to the promoter and induces it, whereas c-Jun interacts with the promoter later. Overexpression of either p53 or c-Jun delays activity of the other protein. Note that overexpression of p53 decreases the level of Wip1, whereas complete depletion of p53 only delays Wip1 expression. This is ultimately the same as what occurs in normal cells.

In non-stressed cells, JNK targets the ubiquitination and subsequent degradation of bound proteins such as c-Jun, JunB, and ATF-2 (38). In addition, JNK forms a complex with and degrades p53 (37). In normal cells, the JNK-p53 and Mdm2-p53 complexes preferentially form during the G0/G1 and S/G2/M phases, respectively, of the cell cycle (37, 40). However, in stressed cells, JNK phosphorylates and activates associated c-Jun, ATF-2, and p53 proteins and enhances their transcriptional regulation of stress-responsive genes (41, 42). Our results show that Wip1 is regulated by both the p38 MAPK-p53 and JNK-c-Jun pathways in response to UV irradiation. Given these data, it is reasonable to hypothesize that co-transient overexpression of c-Jun and p53 synergistically activates the Wip1 promoter. However, we found that Wip1 promoter activity was significantly reduced by the transient overexpression of p53 alone, or that of p53 and c-Jun, in HCT116 p53+/+ cells (Fig. 3). Wip1 promoter activity seems to be inversely correlated with p53 levels in stressed and unstressed cells. Furthermore, we found that JNK-mediated c-Jun activation markedly decreased in response to the overexpression of p53. Previous studies have described the modulation of the JNK pathway by p53 and downstream target p21 proteins, as p53 and p21 form a ternary complex with JNK and nonenzymatically inhibit JNK activity (43). Basal levels of JNK1 activity are at least 3-fold lower in cells expressing both p53 and p21 than in p21-null cells. We believe that p53 competes with c-Jun for JNK binding after UV irradiation and that abundant levels of p53 interfere with the role of JNK in c-Jun-mediated Wip1 induction. In line with this supposition, Wip1 promoter activity was further increased by transfection of p53 alone and by co-transfection of c-Jun and p53 in HCT116 p53−/− cells but not in HCT116 p53+/+ cells (Fig. 3). Thus, both the c-Jun and p53 proteins play a role in Wip1 induction. However, the balance between the two proteins is critical to achieving maximal Wip1 promoter activity.

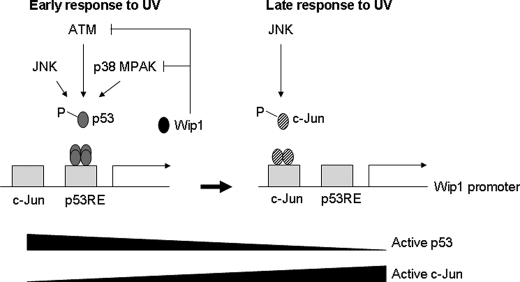

The c-Jun and p53 proteins exhibit different efficacies with regard to Wip1 expression. A Wip1 promoter containing the p53RE mutation had significantly decreased activity, similar to that of a promoter containing mutations in both the p53RE and c-Jun consensus sequences (Fig. 5C). However, experiments with JNK and p38 MAPK inhibitors did not reveal significant differences in Wip1 promoter activity or the amount of Wip1 protein induced by either pathway (Fig. 6, A and B). Therefore, it is difficult to postulate that the p38 MAPK-p53 pathway is a more potent Wip1 inducer than the JNK-c-Jun pathway. Furthermore, we noticed that the overall amount of p53 protein increased abruptly after UV irradiation, whereas the level of c-Jun seemed to remain consistently low (Fig. 6B). These results raise an important question as to the initial pathway by which UV irradiation induces Wip1 expression. The p53 upstream mediators ATM, Chk2, p38 MPAK, and JNK rapidly activate p53 in response to DNA damage. p53 then activates target genes and induces the negative feedback proteins of Mdm2 and Wip1. We observed that p53 binds to the Wip1 promoter earlier than c-Jun in response to DNA damage, and persistent p53 activation inhibits c-Jun binding activity and Wip1 promoter activity (Figs. 3 and 4). Wip1 induction occurs earlier than Mdm2 activation,3 and a depletion of Wip1 with Wip1 RNAi leads to an increase in p53 and Mdm2 levels following γ-irradiation (39). Based on these results, we propose a model for c-Jun-mediated activation of the Wip1 gene (Fig. 8). Shortly after DNA damage occurs, Wip1 is induced by the p38 MAPK-p53 pathway. Later, the JNK-c-Jun pathway substitutes for p53 in activating Wip1, probably in response to the degradation of p53 via Mdm2 binding.

FIGURE 8.

Proposed model for the temporal regulation of the Wip1 promoter by the p38 MAPK-p53 and JNK-c-Jun pathways. After UV irradiation, p53 is immediately activated by various kinases and then induces the Wip1 promoter. Later, p53 is dephosphorylated or inactivated by negative regulators such as Mdm2 and Wip1, and the JNK-c-Jun pathway thus ultimately becomes the major activator of the Wip1 promoter.

JNK activates apoptotic signaling via the up-regulation of pro-apoptotic genes or via the direct modulation of mitochondrial pro- and anti-apoptotic proteins, whereas p53 exerts cytoprotective effects against apoptosis. Pre-expression of functional tsp53V143A protects cells against UV-induced apoptosis by blocking JNK activity. When this happens, p53 preferentially transactivates genes implicated in growth arrest and DNA repair (e.g. p21, GADD45, DDB2, and PCNA) (30). In fact, cells lacking c-Jun undergo extended cell cycle arrest but resist apoptosis. Wip1 abrogates apoptosis in response to various stresses and DNA-damaging agents by dephosphorylating stress-activated kinases (i.e. p38, p53, ATM, Chk1, Chk2, and Mdm2). Recently, Xia and colleagues (23) reported that Wip1 inhibits the MKK4-JNK-c-Jun pathway via the dephosphorylation of MKK4. It would be interesting to investigate the effects of Wip1 overexpression on cellular response to apoptosis or cell cycle arrest in different cellular contexts (e.g. p53−/− or c-Jun−/−).

We are the first to report that Wip1 is up-regulated by the JNK-c-Jun pathway as well as by the p38 MAPK-p53 pathway. The two pathways compete to activate the Wip1 promoter, and they are inhibited via expression of the Wip1 protein. As the pathways execute somewhat different cellular responses with regard to cell cycle arrest and apoptosis in response to UV irradiation, the ultimate fate of the cell appears to depend on which pathway is blocked by Wip1 in Wip1-amplified or -overexpressed tumors. Our results broaden understand of the role of Wip1 as an oncogenic negative regulator in stress-activated apoptosis in human tumors with and without functional p53.

This work was supported by Grants 2007-E00111 and 2009-0081016 from the National Research Foundation of Korea and the Korean government. This research was also supported by Grant A062254 from the Korea Health 21 R&D Project, Ministry of Health, Welfare and Family Affairs, Republic of Korea.

J. Choi, unpublished data.

- Wip

- wild-type p53-induced phosphatase

- JNK

- c-Jun N-terminal kinase

- MAPK

- mitogen-activated protein kinase

- ERK

- extracellular signal-regulated kinase

- EMSA

- electrophoretic mobility shift assay

- GST

- glutathione S-transferase

- MOI

- multiplicity of infection.

REFERENCES

- 1.Levine A. J., Hu W., Feng Z. (2006) Cell Death Differ. 13, 1027–1036 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Levine A. J. (1997) Cell 88, 323–331 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fiscella M., Zhang H., Fan S., Sakaguchi K., Shen S., Mercer W. E., Vande Woude G. F., O'Connor P. M., Appella E. (1997) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 94, 6048–6053 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Choi J., Appella E., Donehower L. A. (2000) Genomics 64, 298–306 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lu X., Nannenga B., Donehower L. A. (2005) Genes Dev. 19, 1162–1174 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lu X., Bocangel D., Nannenga B., Yamaguchi H., Appella E., Donehower L. A. (2004) Mol. Cell 15, 621–634 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fujimoto H., Onishi N., Kato N., Takekawa M., Xu X. Z., Kosugi A., Kondo T., Imamura M., Oishi I., Yoda A., Minami Y. (2006) Cell Death Differ. 13, 1170–1180 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Takekawa M., Adachi M., Nakahata A., Nakayama I., Itoh F., Tsukuda H., Taya Y., Imai K. (2000) EMBO J. 19, 6517–6526 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lu X., Ma O., Nguyen T. A., Jones S. N., Oren M., Donehower L. A. (2007) Cancer Cell 12, 342–354 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Li J., Yang Y., Peng Y., Austin R. J., van Eyndhoven W. G., Nguyen K. C., Gabriele T., McCurrach M. E., Marks J. R., Hoey T., Lowe S. W., Powers S. (2002) Nat. Genet. 31, 133–134 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hirasawa A., Saito-Ohara F., Inoue J., Aoki D., Susumu N., Yokoyama T., Nozawa S., Inazawa J., Imoto I. (2003) Clin. Cancer Res. 9, 1995–2004 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Yu E., Ahn Y. S., Jang S. J., Kim M. J., Yoon H. S., Gong G., Choi J. (2007) Breast Cancer Res. Treat. 101, 269–278 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Saito-Ohara F., Imoto I., Inoue J., Hosoi H., Nakagawara A., Sugimoto T., Inazawa J. (2003) Cancer Res. 63, 1876–1883 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Loukopoulos P., Shibata T., Katoh H., Kokubu A., Sakamoto M., Yamazaki K., Kosuge T., Kanai Y., Hosoda F., Imoto I., Ohki M., Inazawa J., Hirohashi S. (2007) Cancer Sci. 98, 392–400 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bulavin D. V., Demidov O. N., Saito S., Kauraniemi P., Phillips C., Amundson S. A., Ambrosino C., Sauter G., Nebreda A. R., Anderson C. W., Kallioniemi A., Fornace A. J., Jr., Appella E. (2002) Nat. Genet. 31, 210–215 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wechsler T., Chen B. P., Harper R., Morotomi-Yano K., Huang B. C., Meek K., Cleaver J. E., Chen D. J., Wabl M. (2004) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 101, 1247–1252 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ali A., Zhang J., Bao S., Liu I., Otterness D., Dean N. M., Abraham R. T., Wang X. F. (2004) Genes Dev. 18, 249–254 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.den Elzen N. R., O'Connell M. J. (2004) EMBO J. 23, 908–918 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Choi J., Nannenga B., Demidov O. N., Bulavin D. V., Cooney A., Brayton C., Zhang Y., Mbawuike I. N., Bradley A., Appella E., Donehower L. A. (2002) Mol. Cell. Biol. 22, 1094–1105 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bulavin D. V., Phillips C., Nannenga B., Timofeev O., Donehower L. A., Anderson C. W., Appella E., Fornace A. J., Jr. (2004) Nat. Genet. 36, 343–350 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Belova G. I., Demidov O. N., Fornace A. J., Jr., Bulavin D. V. (2005) Cancer Biol. Ther. 4, 1154–1158 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rayter S., Elliott R., Travers J., Rowlands M. G., Richardson T. B., Boxall K., Jones K., Linardopoulos S., Workman P., Aherne W., Lord C. J., Ashworth A. (2008) Oncogene 27, 1036–1044 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Xia Y., Ongusaha P., Lee S. W., Liou Y. C. (2009) J. Biol. Chem. 284, 17428–17437 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Junttila M. R., Li S. P., Westermarck J. (2008) FASEB J. 22, 954–965 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Johnson G. L., Lapadat R. (2002) Science 298, 1911–1912 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rossi M., Demidov O. N., Anderson C. W., Appella E., Mazur S. J. (2008) Nucleic Acids Res. 36, 7168–7180 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Han H. S., Yu E., Song J. Y., Park J. Y., Jang S. J., Choi J. (2009) Mol. Cancer Res. 7, 713–723 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Dhanasekaran D. N., Reddy E. P. (2008) Oncogene 27, 6245–6251 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Shaulian E., Karin M. (2001) Oncogene 20, 2390–2400 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lo P. K., Huang S. Z., Chen H. C., Wang F. F. (2004) Cancer Res. 64, 8736–8745 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Shaulian E., Schreiber M., Piu F., Beeche M., Wagner E. F., Karin M. (2000) Cell 103, 897–907 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Shklyaev S. S., Namba H., Sautin Y., Namba H., Sautin Y., Mitsutake N., Nagayama Y., Ishikawa N., Ito K., Zeki K., Yamashita S. (2001) Anticancer Res. 21, 2569–2575 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Toh W. H., Siddique M. M., Boominathan L., Lin K. W., Sabapathy K. (2004) J. Biol. Chem. 279, 44713–44722 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Heinemeyer T., Wingender E., Reuter I., Hermjakob H., Kel A. E., Kel O. V., Ignatieva E. V., Ananko E. A., Podkolodnaya O. A., Kolpakov F. A., Podkolodny N. L., Kolchanov N. A. (1998) Nucleic Acids Res. 26, 362–367 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Gong X., Wang M., Tashiro S., Onodera S., Ikejima T. (2006) Exp. Mol. Med. 38, 428–434 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Buschmann T., Adler V., Matusevich E., Fuchs S. Y., Ronai Z. (2000) Cancer Res. 60, 896–900 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Fuchs S. Y., Adler V., Buschmann T., Yin Z., Wu X., Jones S. N., Ronai Z. (1998) Genes Dev. 12, 2658–2663 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Fuchs S. Y., Xie B., Adler V., Fried V. A., Davis R. J., Ronai Z. (1997) J. Biol. Chem. 272, 32163–32168 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Batchelor E., Mock C. S., Bhan I., Loewer A., Lahav G. (2008) Mol. Cell 30, 277–289 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Schreiber M., Kolbus A., Piu F., Szabowski A., Möhle-Steinlein U., Tian J., Karin M., Angel P., Wagner E. F. (1999) Genes Dev. 13, 607–619 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Buschmann T., Potapova O., Bar-Shira A., Ivanov V. N., Fuchs S. Y., Henderson S., Fried V. A., Minamoto T., Alarcon-Vargas D., Pincus M. R., Gaarde W. A., Holbrook N. J., Shiloh Y., Ronai Z. (2001) Mol. Cell. Biol. 21, 2743–2754 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Dérijard B., Hibi M., Wu I. H., Barrett T., Su B., Deng T., Karin M., Davis R. J. (1994) Cell 76, 1025–1037 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Xue Y., Ramaswamy N. T., Hong X., Pelling J. C. (2003) Mol. Carcinog. 36, 38–44 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]