Abstract

Differential Methylation Hybridization (DMH) is a high-throughput DNA methylation screening tool that utilizes methylation-sensitive restriction enzymes to profile methylated fragments by hybridizing them to a CpG island microarray. This array contains probes spanning all the 27,800 islands annotated in the UCSC Genome Browser. Herein we describe a DMH protocol with clearly identified quality control points. In this manner, samples that are unlikely to provide good read-outs for differential methylation profiles between the test and the control samples will be identified and repeated with appropriate modifications. The step-by-step laboratory DMH protocol is described. In addition, we provide descriptions regarding DMH data analysis, including image quantification, background correction, and statistical procedures for both exploratory analysis and more formal inferences. Issues regarding quality control are addressed as well.

Keywords: DNA methylation, Differential Methylation Hybridization (DMH), CpG islands (CGI), microarray

1. Introduction

The epigenome of a cell is a combination of important heritable characteristics that coordinate with DNA sequence information to modulate gene transcriptions. There are two general classes of epigenetic modifications: one that alters the residues on DNA-associated proteins (histones) and the other adds methylation marks to the cytosine residues of CG dinucleotides. While the methylation state of DNA is often associated with particular types of histone modifications (1), this chapter focuses only on detecting DNA methylation in a genome wide approach termed Differential Methylation Hybridization (DMH).

In the human genome, the occurrence of CG-dinucleotides is infrequent. They usually occur in clusters known as CpG islands or CGIs. There are different ways to annotate CGIs. Classically, if stretches of DNA longer than 500 bp have a total C and G greater than 55%, and the observed CG sites divided by the expected CG sites are greater than 65% (2), this region is classified as a CGI. While the criteria for determining the presence of CGIs vary somewhat between research groups, it is of interest that 60–80% of the annotated islands occur around the promoter regions of known genes (3). In diseased states, such as cancer initiation and progression, DNA methylation in promoter CGIs is often associated with reduced expression or silencing of the genes involved (4). Although other histone modifications and the recruitment of key factors to the promoters are also involved in this process, DNA methylation analyses are well established and can be readily conducted on large cohorts of patient samples and even in archival material.

The study of DNA methylation can be subdivided into two key types: targeted and genome-wide analyses. In the targeted approach the goal is to survey the methylation status of a selected genomic region with high resolution and specificity. However, in a genome-wide approach the goal is to capture multiple genomic regions which harbor DNA methylation. In this chapter, in additional to the global DMH analysis (see figure 1), we will also discuss using a targeted approach, MassARRAY/EpiTyper 1.0, for validating global targets (see figure 2).

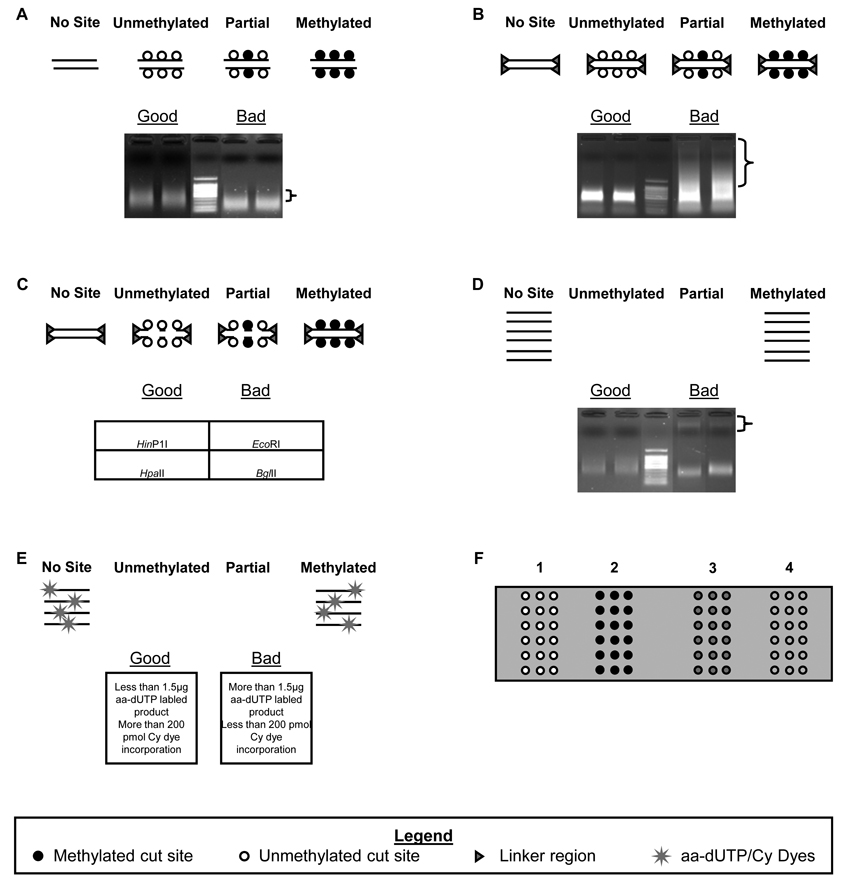

Figure 1.

DMH protocol outline. A DNA sonication: genomic DNA is fragmented to ~500–800 bp in length. Gel shows typical DNA smears of good and bad samples. B End blunting and linker ligation: sonicated DNA is end-repaired and used as a template for linker-adapters attachment. Gel shows a good sample (smear pattern similar to the sonicated DNA) and a bad sample (smear pattern has high MW masses that are not seen in the sonicated DNA). C Methylation Sensitive Restriction: The Linker ligated fragments are digested with any restriction enzyme which recognizes a sequence containing a CG di-nucleotide and is only able to digest the DNA if it lacks a methylated cytosine. D Linker-mediated PCR: The fragments which survive digestion are amplified using primers complimentary to the linker sequence. As depicted, fragments containing unmethylated or partially methylated sites will not be amplified. E Dye Labeling: Klenow fragments are used to incorporate amino-allyl dUTPs (aa-dUTPs) into the amplified fragments. These aa-dUTPs then serve as attachment sites for the Cy dyes. F Microarray Outcomes: After the test sample and control sample are mixed at equal concentrations, they are allowed to hybridize to the microarray potentially giving any of the following outcomes for each probe: 1 (pseudo-red) hypermethylation of test sample as compared to the control sample; 2 (pseudo-green) hypomethylation of test sample; 3 (pseudo-yellow) equal methylation of both samples; 4 (no signal above background) no hybridization to the probes can be caused by poor interaction between the probe and fragment, or fragments not seen because they are unmethylated and digested.

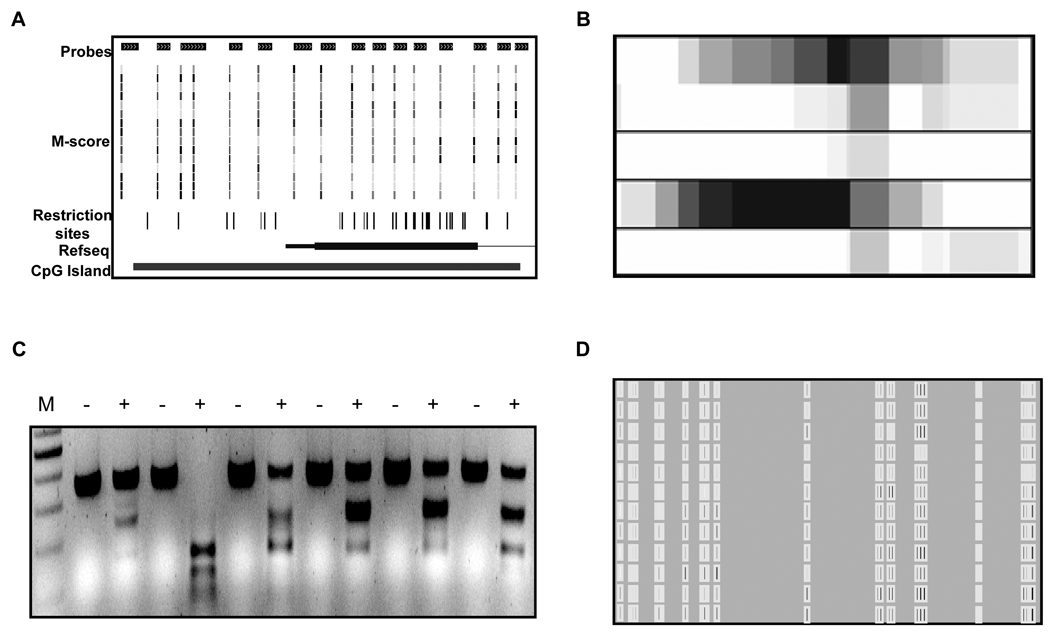

Figure 2.

DMH data validation. A Identifying the region: Bed files, which contain the M-score values generated from the microarray signals, are visualized using the UCSC genome browser. The advantage of using the genome browser is in the ease of determining associated genes and if any easily detectable patterns exist in the methylation of the probes. It is also useful to visualize the density of restriction enzymes which can be used for COBRA analysis. B Smudge plots: Smudge plot (when used in conjuncture with the genome browser) representing a visualization of the most methylated regions of all the test samples in the study. Primers for cobra analysis can then be generated for the regions showing the most methylation in DMH (also containing the necessary restriction sites for downstream validation). C COBRA analysis: Agarose gel showing qualitatively the methylation state of a series of samples. Lower molecular weight bands seen in the digested lanes (+), compared to the mock digested lanes (−), signify the methylation of the restriction site prior to the bisulfite conversion reaction. D Quantitative MassARRAY data: MassARRAY analysis gives quantitative methylation values listed as percentage methylated from 0% – 100%. These values for each CpG unit can be adjusted with the use of a standard curve and a large sample set to give more accurate readings (described in methods section). The figure represents the adjusted values with black being 100% methylated, and white being no methylation.

Modern systems-biology technologies have dramatically altered the research landscape of biology by introducing the dfficulties inherent in working with a high-dimensional data space where a single sample may be associated with tens of thousands of measurements. DMH-data are not free of these difficulties: a single array provides over 244 thousand data points associated with more than 20 thousand CGIs. On top of the difficulties inherent in high-dimensional data, the signal to noise ratio of the raw DMH data will decrease the sensitivity of standard statistical analysis methods and thus the data must be preprocessed appropriately in order to increase the signal to noise ratio. Our goal is not to provide a guide to DMH data analysis as this has been described before (5); we instead describe the theoretical motivation behind the varying preprocessing and analytical methods available and provide a framework for deciding the approach most suitable for a given scientific enquiry.

2. Materials

2.1. Genomic DNA Isolation

QIAamp DNA Mini Kit (Qiagen, Valencia, CA).

ND-1000 Spectrophotometer (NanoDrop Technologies, Wilmington, DE).

2.2. DNA Fragmentation

Bioruptor 200 (Diagenode SA., Liege, Belgium).

2.3. DMH Amplicon Preparation

100mM dNTPs ( Fisher Scientific).

3 U/µL T4 DNA Polymerase (New England Biolabs (NEB), Ipswich, MA).

Zymo DNA Clean & Concentrator-5 columns (Zymo Research Corp., Orange, CA).

Linker sequences: JW103 (5’-GAA TTC AGA TC-3’) and JW102 (5’-GCG GTG ACC CGG GAG ATC TGC ATT C-3’).

PEG-6000 (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO).

400 U/µL T4 Ligase (NEB).

2U/µL DeepVentR (exo-) DNA Polymerase (NEB).

Methylation-sensitive restriction endonucleases: 10U/µL HinP1I (restriction site: 5’-G↓CGC-3’, NEB); 10U/µL HpaII (restriction site: 5’-C↓CGG-3’, NEB).

2U/µL Deep Vent (exo-) DNA polymerase (NEB).

Aminoallyl-dUTP (Fermentas, Glen Burnie, MD).

BioPrime labeling kit (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA).

Sodium carbonate.

3M Sodium acetate buffer solution (Sigma-Aldrich).

Cy-Dye Post-labeling reactive dye (Amersham Health Inc., Princeton, NJ).

2.4. Microarray Hybridization

2.4.1 Array hybridization

Hybridization chamber (Agilent Technology).

Hybridization oven (Agilent Technology).

Gasket slides (Agilent Technology).

Human Cot-1 DNA (Invitrogen).

Oligo aCGH/ChIP-chip Hybridization Kit (Agilent Techology).

Human CpG Island ChIP-on-chip Microarray Set (Agilent Technology).

2.4.2 Array washing

Slide rack.

Slide tank.

Rotating/rocking platform.

Stabilization and Drying Solution (Agilent Technology).

AccuGENE 20X SSPE buffer (Lonza, Rockford, ME).

Sarcosine (Fisher Scientific).

2.4.3 Array visualization

GenePix Pro 6.0 (Molecular Devices Corp., Sunnyvale, CA).

GenePix 4000B Microarray Scanner (Molecular Devices Corp.).

2.5. Target Validation

EZ DNA Methylation kit (Zymo Research, Orange, CA).

10x Amplitaq Gold polymerase, supplied with buffer and magnesium chloride solution (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA).

dNTPs.

DMSO.

Gene-specific primer pairs.

Methylation-sensitive restriction endonuclease.

3. Methods

3.1 Genomic DNA Isolation

A QIAamp DNA Mini Kit is used to obtain high quality genomic DNA as per the manufacturer’s direction.

As the ratio of DNA to linker is vital to achieving optimal linker ligation efficiency, it is important to determine the concentration of the genomic DNA after isolation. DNA concentration and purity can be obtained rapidly using ND-1000 Spectrophotometer.

A 0.7% agarose gel should be used to determine the quality of the isolated DNA (see Note 1).

3.2 DNA Fragmentation and Restriction

Reduction in genome complexity can be achieved by using restriction enzymes that do not cut at CG-rich regions. This includes enzymes such as MseI (T↓TAA), BfaI (C↓TAG), NlaIII (CATG↓), or Tsp509I (↓AATT). See Note 2 for more information.

An alternative approach to simplify the genome is to fragment DNA by sonication.

There are different types of sonicator and we provide our workflow below as a general guideline. As many different factors affect DNA fragmentation, tight control of all aspects is needed to reproducibly generate the desired fragment size.

Pre-cool the Bioruptor with an ice-water mixture, and remove all ice before initial sonication step. Add a predetermined amount of ice back to the Bioruptor to bring the water level to the appropriate height before the first cycle of sonication.

The Bioruptor is operated in a cyclic manner rather than continuously running. We have found that 8 on-off cycles of 30 seconds each yields DNA fragments with average 500 bp. Ice should be replaced after every 2 cycles, and both the water and ice should be replaced after 4 cycles to reduce fluctuation of water temperature.

Gel electrophoresis (2% agarose gel) is used to determine the fragment size following the sonication. If the fragmentation pattern does not match the desired pattern, additional sonciation cycles can be performed.

See Note 3 for additional information.

3.3 DNA Preparation and Amplification

- End repair 100–200 ng of sonicated DNA by adding the following:

- T4 DNA Polymerase (3 µL)

- 2mM dNTPs (4 µL)

- 10X BSA (2.5 µL)

- 10X NEB buffer#2 (5 µL)

- Enough water to reach a final volume of 50 µL

Incubate at 37° C for 2.5 hours. A Zymo DNA purification column is used to purify the product. Elute DNA with 29.5 µL water.

Linker adapters should be freshly prepared heating equal molar amounts of JW102 and JW103 oligonucleotides to 95–100° C for 5 min and allowing the mixture to cool to room temperature gradually. This is best accomplished by placing the tube of linkers in a beaker of boiling water for 5 minutes and then removing the beaker from the heat source, allowing the temperature to equilibrate to ambient temperature.

- All reagents are kept on ice while the reaction mixture is prepared. To the 29.5 µL of end-repaired DNA from Step 1 add the following to give a final volume of 40 µL:

- Annealed linker adapters (2.5 µL)

- 10 mM ATP (1 µL)

- 50% PEG-6000 (2.5 µL)

- 10X T4 Ligase buffer (4 µL)

- T4 ligase (0.5 µL)

For best control, a thermocycler is used to incubate the reaction mixture at 14° C for 2 hours.

- The efficiency of the linker-ligation is evaluated by performing a test PCR. 1 µL of ligation product is used as a template in a PCR reaction:

- 10 µM JW102 (0.2 µL)

- 10 mM dNTP (0.4 µL)

- 10X ThermoPol Buffer (2 µL)

- DeepVent DNA polymerase (0.4 µL)

- water (14 µL)

- Amplification conditions are as follows:

- 55° C for 2 min, 72° C for 5 min, 95° C for 2 min.

- 55° C for 30 sec and 72° C for 1 min (for 17 cycles).

- 55° C for 30 sec and 72° C for 10 min

Gel electrophoresis is used to visualize the efficiency of the ligation. After separation on a 1.5% agarose gel, one should evaluate smear patterns critically as follows: high MW smears/bands not previously seen after sonication are indicative of an over-ligated sample; an extremely faint smear or high MW band which barely migrates beyond the well is indicative of too much material being lost in the preceding clean-up steps. Either of these scenarios indicates a failed sample and requires restarting the DMH protocol from the linker ligation step by re-evaluating the concentration and the quality of the sonicated DNA.

If the ligation test PCR smear mimics the smear pattern of the post-sonication DNA, the sample passes this QC checkpoint and is ready to proceed to the next step. While there are many methylation-sensitive enzymes capable of interrogating the methylation status of the linker-ligated fragments, we currently use HpaII and HinP1I for this purpose. Two different enzymes are used to decrease the likelihood of incomplete digestion by any one enzyme and to reduce the possibility of false positive results. After sequential digestions, the product is purified with a Zymo column and eluted in 40 µL water.

- The purified restricted fragments will serve as templates for a final linker-mediated PCR. The PCR mix consists of an appropriate amount of template, typically 4 –10 µL restricted DNA is used. (See Note 4).

- 10X ThermoPol Buffer (20 µL)

- 10mM dNTP (4 µL)

- 10 µM JW102 (2 µL)

- DeepVent DNA polymerase (4 µL)

- enough water to bring the final volume to 200 µL

- This mixture is divided into 4 PCR tubes (50 µL per tube) for the actual amplification. Amplification conditions are as follows:

- 55° C for 2 min, 72° C for 5 min, 95° C for 2 min.

- 55° C for 30 sec and 72° C for 1 min (for 24 cycles).

- 55° C for 30 sec and 72° C for 10 min

A Qiaquick column is used to purify the combined PCR products. We typically see a yield of 0.8 to 1.5 µg DNA when eluting twice with 40 µL water. A 1.5% agarose gel should be used to assay the smear pattern of the PCR products. Again the pattern should mimic the initial smears.

3.4 Fluorescent Dye Labeling

We indirectly incorporate the fluorescent dyes (Cy 5 and Cy 3) into the PCR products through the coupling of the dye molecules to an intermediate moiety, aminoallyl dNTP. PCR products (600 ng each from test and control samples) diluted in 68 µL water are combined with BioPrime 2.5X random primers (60 µL) and denatured at 95° C for 5 min and placed on ice for 3 min.

- Once the mixture has cooled the following reagents are added, and the reaction is incubated at 37° C for 6 hr products

- 10X dNTP (2mM dATP, dCTP and dGTP, 0.35mM dTTP) (15 µL)

- 10mM aminoallyl-dUTP (4 µL)

- Klenow (40U/ul) (3 µL)

The reaction is purified using a Qiaquick column and eluting twice with 40µL water. We typically see a yield of between 6 – 10 µg of DNA. The products are then dried using a savant system and re-suspended in 3 µL of water.

The nature of the dyes requires that the fluorescent dye coupling step be carried out in the absence of direct fluorescent lighting. Before being combined with the test sample, 3 µL 0.1 M Na carbonate buffer (pH 9.0) is used to reconstitute the Cy 5 dye. The 3 µL of re-suspended sample should be added to the Cy 5 dye and should be mixed every 30 minutes for 3.5 hours. The Cy 3 dye is similarly reconstituted before the control sample DNA is added. The Cy 3 – control sample is only mixed for 1.5 hr as the incorporation of the Cy 3 dye is much more robust than the Cy 5 dye. It is important to stagger the starting time of these mixtures so they are ready at the same time. Add 100mM sodium acetate (pH5.2) mixed 1:1 with water (70 µL) to each reaction mixture at the end of the incubation period.

After purifying the dye mixtures with Qiaquick columns, labeled samples free of unincorporated dyes are eluted with 80 µL water.

The following absorbance readings should be obtained to determine the concentration of DNA and incorporation of each dye: DNA concentration (260nm), Cy3 incorporation (550nm), and Cy5 incorporation (650nm)

3.5 Microarray Hybridization and Washing

- Mix Cy5 and Cy3-labeled samples such that an equivalent amount of 300 pmol of each fluorescent dye is present in each hybridization mix together with the following reagents:

- Cot-1 DNA (20 µg)

- Agilent blocking buffer (50 µL)

- Agilent hybridization buffer (250 µL)

- Enough water to bring the total volume to 500 µL

Denature the resultant mix for 3 minutes at 95° C, and then incubate for 30 minutes at 40° C.

It is important that the hybridization equipment (hybridization chamber base, chamber top, clamp, chamber thumbscrew, hybridization gasket slide, and CpG island microarray) is assembled in a location close to the hybridization oven to permit an uninterrupted workflow.

Place the gasket slide in the chamber base and carefully add the labeled samples to the gasket slide. Place the microarray slide on the gasket slide with the printed side face down. Position the chamber top on top of the slide assembly, and use the chamber thumbscrew and clamp to seal the hybridization chamber. It is important that the chamber thumbscrew is only turned 90° past snug.

The entire chamber is then placed in a rotating hybridization oven set at 65° C for 16–20 hours rotating at a speed of 10.

In order to effectively eliminate un-hybridized or cross-hybridized probes from targets, the Agilent Stabilization and Drying Solution should be pre-warmed at 37° C. A 1-liter solution containing 299 mL 20X SSPE buffer and 1 mL of 5% sarcosine should be prepared freshly.

Disassemble the hybridization chamber and place the gasket slide in the 1 liter SSPE-sarcosine buffer which was freshly made. Carefully pry open the gasket slide and move the hybridized microarray directly into a slide rack sitting in the same buffer. Wash by allowing the rack to gently rock for 5 minutes.

Transfer the slide rack to a 1 liter solution containing 3 mL 20X SSPE buffer and wash for an additional 5 minutes. The slide rack is then moved to the pre-warmed Stabilization and Drying Solution and allow to gently rock for 1 minute.

Using a slow and controlled motion, pull the slide out of the Stabilization and Drying Solution and place in a light protected slide box. The dried microarray should be scanned immediately.

3.6 Image Quantification

The oligonucleotides (45–60 mers) designed to span human CpG islands are printed onto glass slides using Agilent's 60-mer SurePrint technology. As the SurePrint technology utilizes a non-contact inkjet approach to generate the targets, defects due to surface tension interactions and print-tip variability will be a non-issue in this platform.

The CpG Island microarray contains nearly 244K targets with 237,220 of these falling within 95bp of a CpG island. The remainder of the targets are designed for slide alignment, array quality assessment, or signal pre-processing.

The probes are uniformly distributed on the array within a 267 × 912 grid.

- Several scanners are available for capturing hybridized microarray signals. Scanners such as the Agilent DNA microarray scanner require little user input. The Axon scanner (GenePix Pro 6.0 software) requires user input to identify spot location and capture quantitative values for each spot on the array. Below are brief outlines regarding the operation of an Axon scanner:

- Although the program is fully automated, the scanning process should proceed with a set of pre-determination criteria to permit consistent scanned results.

- It is expected that only a small number of probes on the array should demonstrate differential signal between the Cy3 and Cy5 channel; therefore, the photo multiplier tube (PMT) settings are adjusted so that the overall distribution of the two channels is equivalent.

- These adjustments are implemented manually by the operator:

- To reduce signal bleaching by repeat exposure to the scanning laser, we suggest the pre-scanning process should be confined to the top 25% of the array with continual fine adjustment of the PMT settings to arrive at intensity histogram plots depicting an overall balanced distribution of the two channels.

- The full scan will be performed with the adjusted PMT levels.

- Because the microarray pre-scan is performed on a small section of the microarray, the choice of PMT settings may be too intense resulting in signal saturations for either or both channels when the entire array is scanned. The objective is to generate scanned signals that span the entire dynamic range without resulting in signal saturation on the spots with high level of hybridization.

- The dynamic range of the scanner is between 0 to 216 units. Thus, if the PMT settings are too high, quantitative values for probes with high intensity may be compromised because their signal is greater than the maximal scanning threshold.

- GenePix Pro 6.0 software will automatically determine spot size and location as well as signal intensity for the Cy3 channel, the Cy5 channels and the background. The algorithm for determining spot location and size is highly accurate but not perfect. For example, dye blobs located close to target print sites would be reported as the hybridization signals. Therefore, it is important for the operator to scroll through the gridded microarray image to manually flag mis-calls described above.

3.7 Background Correction

- Signal intensity for a given probe is due to fluorescent signals from labeled DNA probes (true complementary hybridization to the DNA targets) as well as various background signals such as:

- Fluorescent signals from DNA probes that cross-hybridize non-specifically to the arrayed targets.

- Incomplete removal of labeled DNA cross-reacting with the slide matrices during the washing step.

The scanning software provides an intensity value for background signal that is the summation of fluorescent intensities from microarray substrate, labeled DNA that cross-reacts with the substrate and not the considered probe target, labeled DNA fragments that bled over from neighboring probes, and the occasional dye blobs.

The negative control probes provide a means for assessing the level of non-specific binding occurring on the array or within the neighborhood of a given probe.

- There is no consensus within the microarray community with regards to the appropriate strategy for correcting for background noise. In our experience, background correction will introduce noise even as it corrects for background signals between and within experiments. Therefore, computational scientists have to work with biologists to arrive at a balanced approach for data pre-processing. Points to consider:

- If the objective is to identify differentially methylated probes from many similarly methylated but noisy probes, then the need to control for noise outweighs the need for background correction. A simple approach in this scenario will be the removal of probes with signal below background from further analysis.

- If the objective is to evaluate methylation differences between probes of interest, then an accurate signal intensity is needed and appropriate background corrections should be applied to probe intensities prior to comparison. One approach to correct for both cross-hybridization and substrate bleed-through would be to subtract a weighted average of the local background signal and the signals obtained from negative controls situated close to the probe of interest.

3.8 Quality Control

The CpG Island array has approximately 5,000 control probes dispersed evenly across the entire hybridization surface. These probes are designed for: image orientation, quality assessment of sample hybridization, measurement of background signals, and data normalization. See Table 1 for detailed description of the control probes.

- Negative controls

- Arabidopsis control spots can be used for spike-in experiments or can be used as negative control spots.

- In the event when Arabidopsis fragments were not used as spike-in, we should see low signal intensities in the Arabidopsis control and the structural control spots.

- Probes with signal near or below the negative controls cannot be estimated reliably (even if signal is greater than local background)

- Positive controls

- Many of the positive control probes are printed multiple times across the slide. These positive controls are determined empirically to be present in high abundance in many sample types.

- Some of the positive probes are from genomic regions (a.k.a. gene desert regions) known to contain few methyl-sensitive restriction cut sites.

- To gain some perspectives regarding the spatial variabilities in each hybridization experiment, one can track the signal variations of each type of positive controls that are arrayed multiple times across the slide. We expect to see these probes having similar signal intensities across the array.

Table 1.

Description of control probes

| Name | Count | Purpose | Description |

|---|---|---|---|

| BrightCorner (HsCGHBrightCorner) |

1 seq. rep. 14x | Used for slide orientation |

Endogenous sequence with predicted high signal |

| DarkCorner | 1 seq. rep. 35x | Used for slide orientation |

Probe forms a hairpin and does not hybridize with sample |

| Structural negative (NegativeControl) |

1 seq. rep. 675x | Measure of local background signal |

Probe forms a hairpin and does not hybridize with sample |

| Biological negatives. (eg. NC1_00000002) |

98 seq. rep. 6 x 1 seq. rep. 108x |

Measure of cross- hybridization |

Random sequence that do not hybridize well to any sample |

| Reserve negatives. (eg. SM_01) |

12 seq. rep. 40x | ||

| Biological positives (PC_00000004) |

1 seq. rep. 480x | Positive control | Endogenous sequence with predicted high signal |

| Deletion stringency probes(eg. DCP_008001.0) |

50 seq. rep. 2x | Positive control as well as assessment of mismatch effect |

See * below |

| Intensity curve probes (e.g. LACC:SRN_800001, LACC:Intensity3, LACC:GD13C_10_1) |

3564 seq. rep. 1 x 20 seq. rep. 12x |

Signal normalization | Predicted to span the signal space using in-house models |

10 probes, predicted to perform well by in silico analysis, are chosen randomly from a tiling database. In addition, four variants of these probes are printed on the array: a 1-bp deletion; a 3-bp deletion; a 5-bp deletion; and a 7-bp deletion. Deleted bases are chosen at random from the center of the probe sequence. The number after the “.” indicates the number of bases deleted (e.g., DCP_008001.0 and DCP_008001.3 are from the same parent sequence and have 0- and 3-bp deletions, respectively).

3.9 Data Preprocessing

3.9.1. Data cleaning

Most image quantification programs flag spots that do not pass internal QC criteria; these spots should be removed from subsequent analysis.

- Flagging probes that fall below pre-determined thresholds for potential dismissal:

- Threshold for signal to noise ratio

- Threshold for the percent of foreground pixels with signal larger than background

- Threshold for the summarized signal

- Determining thresholds:

- Criterion for threshold determination should be customized.

- The expected distribution should be derived from the actual distribution of relevant parameters across the chips.

- Determine what ‘normal’ values should be and discard or down-weight probes whose signal is significantly outside of the ‘norm’.

Composite scores may also be useful (6)

- If it is desirable to have values for every probe, missing values may be imputed by a number of standard approaches:

- K-nearest neighbor (7)

- Single value decomposition (2)

- Probe neighbor average

- The array is designed to tile CpG islands; hence, a probe with missing value will often be flanked by probes with signal above the established threshold. The average or median of a probe’s ‘neighbors’ can be used to impute the missing value.

3.9.2. Data transformation

The differences between the two samples/channels are often reported as ratios. The compression of ratios between 0 and 1 may be problematic for downstream data analysis.

Log2 transformation is often used to transform signal intensities prior to expressing them as fold changes. It is important to note that raw values below 2−16 ~ 0.00001 are not considered and that the raw ratios below 1 are mapped to values between −16 and 0.

- Notations used for log2 transformation are as follows:

- M is denoted as the log-ratio as M is the pneumonic for “Minus” whereby log2(Cy5/Cy3) is equivalent to log2(Cy5) − log2(Cy3).

- A is denoted as the log-average as A is the pneumonic for "Add” whereby A=0.5*(log2(Cy5) + log2(Cy3))

3.9.3. Intra-slide normalization adjustment for non-biological differences between the two channels

-

1)M′ = (M – L)/S

-

3)A spatial plot of the M values can often reveal the need for intra-slide normalization as well as which normalization procedure to employ.

- MA-plots are 2-dimensional scatter plots, plotting the relationship between M and A.

- There should be no discernable pattern relating M to A.

- The expected value of M is zero and thus the plot should be centered at zero.

- Plotting M-values:

- Convert the quantitative values of M into a color intensity. Two common approaches are as follows:

- Set color value to be green for values below −15, red for values above 15, and a continuous color gradient for values in between. This color scheme is useful for detecting if dye abundance is correlated with spatial location.

- Set color value to be blue for the probe with the lowest M value, yellow for the probe with the largest M value, and a continuous color gradient for values in between. This color scheme is useful for detecting a correlation between relative ranking of M-values and spot location.

- Plot the colors for each probe on a 2-dimensional plot where the x–y coordinate is associated with the location of the probe on the array.

- The resultant plot should have no discernable pattern.

3.9.4. Inter-slide normalization adjusts for non-biological effects between arrays

M-values should be scaled so that they have the same median-deviation across arrays.

- Quantile normalization (14):

- A transformation that brings the mean (median) intensity of all the arrays to the same level.

- If a common reference sample has been labeled with one of the florescent dyes, e.g., Cy3, then quantile normalization should be applied to this channel. The method for adjusting the other channel depends on the intra-slide normalization conducted, but should be adjusted in a manner to not alter the normalized log-ratio within the studied array.

- If a reference sample is not used, then one can use quantile normalization to transform the M values.

3.9.5. Adjustments for probe composition and target region effects

3.10 Data Analysis

3.10.1. Exploratory analysis (i.e., clustering)

This approach is most useful for uncovering possible relationships among different samples within a study.

- Data reduction:

- Most clustering methods will be overwhelmed by the noise in the data if the entire data set is used. To circumvent that:

- A probe flagged in any chip should be removed from consideration.

- Only probes with high variance across arrays should be considered, as probes with lower variance will not have the power necessary to distinguish between traits.

- Do not pre-select probes that distinguish between treatments as this will bias your analysis.

- Metrics

- Most clustering procedures require the operator to select a distance function between the observed data points. Different metrics will likely produce different clusters.

- Euclidean (L2) (17)

- Very common and easy to understand, though hard to interpret in the setting of high-dimensional probe intensity data.

- Manhattan (L1)(18)

- Also common and easy to understand but difficult to interpret.

- One minus absolute correlation (19)

- Highly correlated points will be closer than uncorrelated points.

- Mutual information (MI) (20)

- The MI between two random variables X and Y is given by:

where pi and pj is the probability that X = xi and Y = yi, respectively. - The values for p can be estimated from the data.

- MI is a generalized measure of correlation since the distance is zero if and only if X and Y are statistically independent.

3.10.2. Detecting regions of significantly differentiated methylation

- A direct approach is to utilize threshold value to make a call of significance (e.g. probes with M values (i.e., log ratio) above 1 or below −1 are differentially methylated).

- One of the drawbacks for such a method is the inability to assess the methylation calls statistically. This method also cannot incorporate information derived from neighboring probes (an expected trend of co-methylation in nearby genomic regions).

- M-score (5):

- A simple kernel smoothing function termed M-score is used to integrate probe-level information within a sliding window to portray regional methylation events.

- As an example, the M-score of each probe with respect to other probes within 1-kb region of the genome (500-bp upstream and 500-bp downstream) is calculated as follows:

- Probes are ranked according to their normalized log ratios.

- An arbitrary cutoff, n, is set (e.g., the top and bottom 25th percentile).

- M-score = (# probe log upper nth – #probe log lower nth)/ total probes in 1-kb window)

- Parametric tests for discovering differential methylation.

- Significance analysis of Microarrays (SAM) (23)

- A method that scores each probe intensity with respect to the change in intensity relative to the standard deviation of repeated measurements.

- Significance of probes with score greater than a threshold is determined via a permutation test.

- Non parametric tests for discovering differential methylation.

- Wilcoxon signed-rank (24)

- Alternative to the T-test for discovering loci that individually differentiate between two groups.

- Estimation of p-values assumes symmetry of distribution (may not be supported by the data)

- Permutation tests

- Often times the data will not satisfy the theoretical hypothesis for a given statistical test. Permutation tests will allow one to estimate the empirical distribution of the test.

- Choose a test statistic.

- Compute the test.

- Permute labels on samples at random and repeat steps ii and iii above.

- Compute the number of cases in which the test statistic from the random sample is less than the test statistic from the real data.

- False discovery rates and post-hoc p-values correction:

- For a given DMH experiment, large numbers of comparisons are made resulting in a high probability for false positives. Therefore, the resultant p-values should be adjusted to correct for multiple testing.

- Bonferroni and other similar methods

- Too conservative due to correlation of test statistics (26).

- Westfall-Young correction (27)

- Baysian approaches

3.11 Target Validation

Regions of the genome which are determined to be differentially methylated by M-score (uploaded as a .bed file) are visualized on the UCSC genome browser (http://genome.ucsc.edu) to determine the potential interest or importance of the region. Promoter CpG islands near tumor suppressor genes, transcription factors, or genes shown to be methylated in other tumor types are validated using a qualitative followed by a quantitative method.

Non-degenerate primers are designed against the bisulfite-converted DNA sequence to amplify the region in or around the probes identified as being differentially methylated in DMH analysis. It is important that the amplified region should contain at least one restriction site for an enzyme which has a CG-dinucleotide in its recognition site (e.g., BstUI) as this site will be preserved in a methylated allele thereby providing restricted fragment(s) as a read-out of the hypermethylation status. As bisulfite-converted DNA will be used, it is important to adjust the PCR primers so that the amplified regions will be between 350 to 500 bp for optimal analysis of fresh-frozen samples and 100 to 150 bp for archival materials. If longer regions are desired, multiple primer sets can be designed to extend the interrogation area.

Samples of interest are bisulfite converted using the EZ DNA Methylation kit following the manufacturer instructions. We, however, elect to elute the purified products with 2 X 50 µL of water and allow a 5-minutes incubation period before each spinning. The bisulfite-converted DNA will be used as templates in COBRA (Combined Bisulfite Restriction Analysis) assay.

- Using 2 µL of the bisulfite-converted DNA as templates, the following PCR reagents are added:

- 10x Amplitaq Gold buffer (2 µL)

- 25 mM magnesium chloride (2.4 µL)

- 2.5 µM dNTP mix (2 µL)

- 10 µM Forward Reverse primer (0.4 µL each)

- DMSO (0.2 µL)

- Water (10.4 µL)

- Amplitaq Gold polymerase (0.2 µL)

- PCR conditions will vary according to the optimal annealing temperature of the primers being used, but a typical amplification program is as follows:

- 95° C for 10 min.

- 95° C for 30 sec, 58–62° C for 30 sec, and 72° C for 1 min (for 45 cycles).

- 72° C for 10 min

- Half of the PCR products (10 µL) is moved to a new tube containing the following reagents for COBRA digestion:

- Appropriate restriction enzyme (5 units)

- Matched restriction enzyme buffer (2 µL)

- Enough water to bring the total volume to 20 µL.

To minimize potential agarose gel artifacts, 8 µL water, and 2 µL restriction buffer should be added to the remaining 10 µL of PCR product. Both tubes are then incubated at the appropriate temperature for 1 hour, and samples from both tubes will be run out side-by-side on a 1.5% agarose gel.

Presence of MW band(s) corresponding to the size of restricted fragment(s) in the restricted product lane is indicative of hypermethylation in the interrogated region as sodium bisulfite will abrogate any potential restriction sites if the CG sites are unmethylated. COBRA assay is a reliable and qualitative test to validate DMH results.

Often times, DMH analysis is performed on a subset of samples to identify regions of interest to be followed up in a large cohort of samples to derive statistical power. In this scenario, we will modify the COBRA primers to meet the specifications of MassARRAY assay (Sequenom, Inc.) to obtain quantitative methylation status of large number of samples in the region of interest.

While the MassARRAY assay is quantitatively accurate to within 5%, PCR amplification of bisulfite-converted DNA can introduce bias into the reaction by preferentially amplifying methylated or unmethylated species. In order to detect and correct for this potential bias, we use an artificial standard curve generated by combining 100% methylated DNA (CpGenome Universal Methyalted DNA from Chemicon) and human blood DNA (isolated from whole blood using a standard QIAamp DNA Mini Kit). See Note 5.

According to the manufacturer’s guideline, 5’ modifications to the COBRA primers are added: forward primer modification, AGGAAGAGAG; reverse primer, CAGTAATACGACTCACTATAGGGAGAAGGCT.

The PCR conditions used in the COBRA assay are used to amplify the samples and standard curve samples. Experience tells us that the addition of the 5’ modifications does not significantly influence the PCR efficiency, but it is important that 5 µL of PCR product be examined on a 1.5% agarose gel to verify the presence of a dominant band of the predicted size. Neither an additional band having a much lower intensity than the expected product, nor unused primer bands interfere with the MassARRAY assay. Samples which fail this criterion can be re-amplified before being submitted for MassARRAY analysis. If any of the standard curve samples fail to meet this criterion, it must be re-amplified.

5 µL of PCR product is loaded into a 384 or 96 well plate for submission to a core facility. It is important to check with the core facility you will be submitting your samples to for specifics on how they wish to have the samples submitted.

When the data are returned to you, the excel worksheet that contains a listing of the individual CG units methylation levels can be used to transform the data into less biased results. The standard curve samples can be used to perform a standard linear regression for each CG unit and the resultant regression curve used to perform a linear transformation on all samples (including standards). As human blood DNA does show some level of methylation at some CpG sites, it is possible that percentages of greater than 100 or less than 0 can be reported at this point.

If negative values or values greater than 100 are created, a second linear transformation is performed. The second linear transformation requires setting the smallest value detected for each CG unit to zero, and setting the highest value detected to 1. Together the two linear transformations account for PCR bias (the first linear transformation), and allow for values that make sense in a biological context (the second linear transformation).

Footnotes

Between 60 and 80ng of the DNA loaded on the gel should be of a single high molecular weight band, with absence of smears (signifying DNA degradation) and a low weight bands (signifying RNA contamination).

| Enzyme | Mean length of digested product |

Median length of digested product |

|---|---|---|

| MseI | 158 | 81 |

| BfaI | 387 | 246 |

| NlaIII | 219 | 136 |

| Tsp509I | 140 | 77 |

It is of primary importance that the sonicated product be as uniform across samples as possible so as to minimize experimental variance between samples. Any samples which are unable to conform to one another should be restarted to ensure the highest quality of the results.

The actual amount of DNA is determined empirically as the sample methylation status and the fragment size will alter this amount. It is important that the 4–10 µl of DNA correspond to between 0.8 and 1.5 µg of DNA. Too little DNA and there is a risk that there will not be enough for downstream steps, yet too much and there is a risk of bias if the reaction reaches a plateau.

A six point standard curve (0%, 20%, 40%, 60%, 80%, and 100% methylated) is created by bisulfite-converting 500 ng of the 100% methylated DNA and blood DNA mixed together at the appropriate concentrations using the EZ DNA Methylation Kit from Zymo Research. By mixing the DNA prior to bisulfite-conversion it is also possible to detect differences in bisulfite-conversion efficiencies.

References

- 1.Fuks F. DNA methylation and histone modifications: teaming up to silence genes. Current Opinions Genetics Development. 2005;15:490–495. doi: 10.1016/j.gde.2005.08.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Takai D, Jones PA. Comprehensive Analysis of CpG Islands in Human Chromosomes 21 and 22. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 2002;99:3740–3745. doi: 10.1073/pnas.052410099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Davuluri RV, Grosse I, Zhang MQ. Computational identification of promoters and first exons in the human genome. Nature Genetics. 2001;29:412–417. doi: 10.1038/ng780. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jones PA, Baylin SB. The epigenomics of cancer. Cell. 2007;128:683–692. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.01.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Yan P, Potter D, Deatherage D, Lin S, Huang TH-M. Differential Methylation Hybridization: profiling DNA methylation in a high-density CpG island microarray. Methods in Mol Biol, DNA Methylation Protocols. (2nd edition) 2008 doi: 10.1007/978-1-59745-522-0_8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fare TL, Coffey EM, Dai H, He YD, Kessler DA, Kilian KA, Koch JE, LeProust E, Marton MJ, Meyer MR, Stoughton RB, Tokiwa GY, Wang Y. Effects of Atmospheric Ozone on Microarray Data Quality. Anal. Chem., ASAP Article. 2003 doi: 10.1021/ac034241b. 10.1021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Troyanskaya O, Cantor M, Sherlock G, Brown P, Hastie T, Tibshirani R, Botstein D, Altman RB. Missing value estimation methods for DNA microarrays. Bioinformatics. 2001;17(6):520–525. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/17.6.520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Smyth GK, Yang Y-H, Speed TP. Statistical issues in microarray data analysis. Methods in Molecular Biology. 2003;224:111–136. doi: 10.1385/1-59259-364-X:111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wolfinger RD, Gibson G, Wolfinger ED, Bennett L, Hamadeh H, Bushel P, Afshari C, Paules RS. Assessing gene significance from cDNA microarray expression data via mixed models. Journal of Computational Biology. 2001;8:625–637. doi: 10.1089/106652701753307520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Yang YH, Dudoit S, Luu P, Speed TP. Normalization for cDNA microarray data. In: Bittner ML, Chen Y, Dorsel AN, Dougherty ER, editors. Microarrays: Optical Technologies and Informatics; Proceedings of SPIE.2001. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Finkelstein DB, Gollub J, Ewing R, Sterky F, Somerville S, Cherry JM. Iterative linear regression by sector. In: Lin SM, Johnson KF, editors. Methods of Microarray Data Analysis. Papers from CAMDA 2000. Kluwer Academic; 2001. pp. 57–68. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kepler TB, Crosby L, Morgan KT. Santa Fe Institute Working Paper. New Mexico: Santa Fe; 2001. Normalization and analysis of DNA microarray data by self-consistency and local regression. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dean N, Raftery AE. Normal Uniform Mixture Differential Gene Expression Detection for cDNA Microarrays. BMC Bioinformatics. 2005;6:173. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-6-173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bolstad BM, Irizarry RA, Astrand M, Speed TP. A Comparison of Normalization Methods for High Density Oligonucleotide Array Data Based on Bias and Variance. Bioinformatics. 2003;19(2):185–193. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/19.2.185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wu Z, Irizarry RA, Gentleman R, Murillo FM, Spencer F. A model based background adjustment for oligonucleotide expression arrays. J Am Stat Assoc. 2004;99:909–918. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Johnson WE, Li W, Meyer CA, Gottardo R, Carroll JS, Brown M, Liu XS. Model-based analysis of tiling-arrays for ChIP-chip. PNAS. 2006;103(33):12457–12462. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0601180103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.D'haeseleer P, Liang S, Somogyi R. Genetic network inference: from co-expression clustering to reverse engineering. Bioinformatics. 2000;16:707–726. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/16.8.707. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kaufman L, Rousseeuw PJ. Finding Groups in Data: An Introduction to Cluster Analysis. New York: Wiley; 1990. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Eisen MB, Spellman PT, Brown PO, Botstein D. Cluster analysis and display of genome wide expression patterns. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences USA. 1998;95:14863–14868. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.25.14863. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Priness I, Maimon O, Ben-Galcorresponding I. Evaluation of gene-expression clustering via mutual information distance measure. BMC Bioinformatics. 2007;8:111. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-8-111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Snedecor GW, Cochran WG. Statistical Methods. Eighth Edition. Iowa State University Press; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lindman HR. Analysis of variance in complex experimental designs. San Francisco: W. H. Freeman & Co; 1974. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Tusher VG, Tibshirani R, Chu G. Significance analysis of microarrays applied to the ionizing radiation response. PNAS. 2001;98:5116–5121. doi: 10.1073/pnas.091062498. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wilcoxon F. Individual comparisons by ranking methods. Biometrics. 1945;1:80–83. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zheng M, Barrera LO, Ren B, Wu YN. ChIP-chip: Data, Model, and Analysis. Biometrics. 2007;63:787–796. doi: 10.1111/j.1541-0420.2007.00768.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Cao H, Kane D, Narasimhan S, Sunshine M, Bussey K, Kim S, Shankavaram UT, Zeeberg B, Weinstein J. Microarray Data Analysis. http://discover.nci.nih.gov/microarrayAnalysis/Statistical.Tests.jsp.

- 27.Westfall PH, Young SS. Resampling-based Multiple Testing. New York: Wiley; 1993. [Google Scholar]