Abstract

The extracellular calcium-sensing receptor (CaSR) plays a major role in the maintenance of a physiological serum ionized calcium (Ca2+) concentration by regulating the circulating levels of parathyroid hormone. It was molecularly identified in 1993 by Brown et al. in the laboratory of Dr. Steven Hebert with an expression cloning strategy. Subsequent studies have demonstrated that the CaSR is highly expressed in the kidney, where it is capable of integrating signals deriving from the tubular fluid and/or the interstitial plasma. Additional studies elucidating inherited and acquired mutations in the CaSR gene, the existence of activating and inactivating autoantibodies, and genetic polymorphisms of the CaSR have greatly enhanced our understanding of the role of the CaSR in mineral ion metabolism. Allosteric modulators of the CaSR are the first drugs in their class to become available for clinical use and have been shown to treat successfully hyperparathyroidism secondary to advanced renal failure. In addition, preclinical and clinical studies suggest the possibility of using such compounds in various forms of hypercalcemic hyperparathyroidism, such as primary and lithium-induced hyperparathyroidism and that occurring after renal transplantation. This review addresses the role of the CaSR in kidney physiology and pathophysiology as well as current and in-the-pipeline treatments utilizing CaSR-based therapeutics.

Keywords: proximal tubule; thick ascending limb; distal convoluted tubule; collecting duct; 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3; parathyroid hormone; hypercalcemia; hypocalcemia; hypercalciuria; calcimimetic; hyperparathyroidism; inactivating mutation; activating mutation; polymorphism; familial hypocalciuric hypercalcemia; neonatal severe primary hyperparathyroidism; autosomal dominant hypoparathyroidism

the extracellular calcium (Cao2+)-sensing receptor (CaSR) (21) enables key tissues participating in Cao2+ homeostasis to closely monitor the blood calcium level. When it detects even minute perturbations in Cao2+ from its normal level, the CaSR directly or indirectly modulates various homeostatic tissues so as to normalize Cao2+. Key CaSR-expressing, homeostatic tissues include the parathyroid hormone (PTH)-secreting parathyroid glands, calcitonin (CT)-secreting thyroidal C cells, intestines, bone, and kidney (152). The last three determine how much Ca2+ moves into or out of the body (intestine and kidney, respectively) or how Ca2+ moves between the extracellular fluids (ECF) and bone. These Ca2+ fluxes are regulated by PTH and CT, as well as by 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3 [1,25(OH)2D3], whose renal synthesis is homeostatically regulated. Intrarenal distribution, targets, and effectors of the CaSR are described in Table 1.

Table 1.

Intrarenal distribution, targets, and effectors of the CaSR

| Region | Cellular Target | Biological Effects |

|---|---|---|

| PCT/PST | ↓PTH1R | ↓Pi transport |

| ↑1-Hydroxylase activity | ↑1,25(OH)2D3 synthesis | |

| ↑p38 MAPK | ↑VDR expression | |

| MTAL | ↑H+-K+-ATPase | ↑Urine acidification |

| ↓Calcitonin- and AVP-induced cAMP production | ↓NaCl/Ca2+/Mg2+ transport | |

| CTAL | ↓CLDN-16 | ↓Ca2+/Mg2+ transport |

| ↓NKCC2 | ↓NaCl/Ca2+/Mg2+ transport | |

| ↓ROMK | ↓NaCl/Ca2+/Mg2+ transport port | |

| ↓PTH-induced second messenger production | ↓Transcellular Ca2+ transport | |

| DCT/CNT | ↑TRPV5 | ↑Ca2+ reabsorption |

| CCD/OMCD | ↑H+-ATPase | ↑Urine acidification |

| OMCD/IMCD | ↓AVP-dependent AQP2 apical insertion | ↓Urine concentration |

| JG cells | ↓AC-V, renin gene expression | ↓Renin secretion |

CaSR, calcium-sensing receptor; PCT/PST, proximal convoluted/straight tubule; MTAL, medullary thick ascending limb (TAL); CTAL, cortical TAL; DCT/CNT, distal convoluted tubule/connecting segment; CCD, cortical collecting duct; OMCD/IMCD, outer/inner medullary collecting duct; JG, juxtaglomerular; PTH, parathyroid hormone; MAPK, mitogen-activated protein kinase; NKCC2, Na+-K+-2Cl− cotransporter 2; ROMK, renal outer medullary potassium K+ channel; TRPV5, transient receptor potential vanilloid 5; AQP2, aquaporin 2; AC-V, type V adenylate cyclase; 1,25(OH)2D3, 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3.

Over the past 10–15 years, there has been great progress in understanding the diverse roles of the CaSR in the kidney in health and disease, which is the focus of this article. We first briefly review key molecular and biochemical features of the CaSR, its binding partners and signaling pathways, and the regulation of its function and expression. Because of the key roles of CaSR-regulated PTH secretion in controlling renal function, the CaSR's role in the parathyroid gland is then addressed. A more detailed description of the CaSR's functions in the kidney follows, along with a description of the impact of inherited and acquired disorders of Cao2+ sensing as well as other common diseases of calcium metabolism on the CaSR and its regulation of renal function.

Structure and Function of CaSR

The CaSR belongs to family C of the G protein-coupled receptors; family C also includes the metabotropic glutamate receptors, GABAB receptors, receptors for taste and pheromones, and an amino acid- and divalent cation-sensing receptor called GPRC6A (16, 21). Although some evidence exists that GPRC6A is a second Cao2+-sensing receptor (123), this rapidly evolving topic is beyond the scope of this discussion. The extracellular domain (ECD) of the human CaSR comprises 612 amino acids and is followed by a 250 amino acid domain of 7 transmembrane helices (TMD) and finally by a carboxy terminal (C) tail of ∼200 amino acids (152). Molecular modeling based on the known structures of the ECDs of several metabotropic glutamate receptors (mGluRs) (88) strongly suggests that the CaSR's ECD exhibits a venus flytrap (VFT)-like motif—a bilobed structure with a crevice between the two lobes thought to contain a key binding site for Cao2+ (71, 144). The VFT is presumed to be open in the absence of agonist and to close upon binding Ca2+, thereby initiating conformational changes in the TMD and intracellular domains that initiate signal transduction.

During its biosynthesis, the CaSR is targeted to the endoplasmic reticulum by a signal peptide, where it dimerizes through intermolecular disulfide bonds involving cysteines 129 and 131 within each monomer (43, 124). The receptor is then extensively glycosylated in the Golgi apparatus before reaching the cell surface. The biologically active cell surface CaSR, upon binding Cao2+, activates the G proteins Gq/11, Gi, and G12/13, which stimulate phospholipase C (PLC) [thereby producing diacylglycerol and inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate (IP3) (the latter of which releases Ca2+ from intracellular stores)], inhibit adenylate cyclase, and activate Rho kinase, respectively (72). In addition to inhibiting adenylate cyclase via Gi, the CaSR can also lower cAMP indirectly by increasing intracellular Ca2+ (Cai2+), thereby reducing the activity of Ca2+-inhibitable adenylate cyclase or activating phosphodiesterase (52). In occasional cells, the CaSR activates Gs, the stimulatory G protein stimulating adenylate cyclase (99). The receptor regulates diverse other intracellular signaling systems, including mitogen-activated protein kinases (MAPKs) [e.g., extracellular signal-regulated kinase 1/2 (ERK1/2), p38 MAPK, and c-Jun NH2-terminal kinase (JNK)], phospholipases A2 and D, and the epidermal growth factor (EGF) receptor, a recently reviewed topic (72).

The CaSR undergoes little desensitization upon repeated exposure to agonist, at least in parathyroid cells. Its resistance to desensitization results, in part, from its binding to the large actin-binding scaffold protein filamin A and is presumably important to ensure the CaSR's persistent presence on the cell surface, thereby enabling it to continuously monitor Cao2+ (72). This interaction likely tethers the receptor to the actin-based cytoskeleton, in so doing rendering it less susceptible to agonist-induced internalization. Filamin A binds several MAPK components, and the binding of the CaSR to filamin A facilitates CaSR-mediated activation of ERK1/2 (6). In addition to the G proteins noted above and filamin A, caveolin-1 is another direct or indirect (e.g., by binding directly to filamin A and thence to the CaSR) binding partner of the CaSR (81). Caveolin-1 is a key component of caveolae, small flask-shaped invaginations of the cell surface that participate in a variety of cellular functions, prominent among which is serving as a cellular signaling center containing various signal transduction molecules (167). Other binding partners of the CaSR include the K+ channels Kir4.1 and Kir4.2, the receptor activity-modifying proteins (RAMP) RAMP-1 and RAMP-3, which facilitate the translocation of the nascent CaSR to the cell surface in some cells, and the E3 ubiquitin ligase dorfin, which could participate in regulating the proteasomal degradation of the CaSR (72).

Several factors upregulate expression of the CaSR gene, including Cao2+ (acting via the CaSR) (171) and calcimimetics (drugs activating the receptor by an allosteric mechanism—see below), vitamin D [through vitamin D response elements (VDRE) in the two promoters of the CaSR gene] (22), and the cytokines interleukin-1β (113) and interleukin-6 (23). Since the CaSR upregulates the VDR gene (97), there is the possibility of a synergistic interaction between VDR and the CaSR, whereby activation of the CaSR increases its own expression and that of the VDR; the latter could potentiate vitamin D action, thereby further increasing CaSR expression and action, and so forth.

Activators of CaSR other than Cao2+

Cao2+ is not the only CaSR agonist. A variety of divalent (e.g., Mg2+ and Sr2+) and trivalent (La3+ and Gd3+) cations activate the receptor, as do highly positively charged organic molecules, such as the polyamines (i.e., spermine), aminoglycoside antibiotics (e.g., neomycin), protamine, and polyarginine (21, 152). These polycationic agonists are termed type 1 agonists, and they activate the receptor even without extracellular Ca2+ being present. Type 2 agonists, in contrast, require the presence of some level of Cao2+, viz., in the millimolar range, to activate the CaSR (112). Type 2 agonists include various l-amino acids, especially aromatics, and allosteric activators of the receptor, the so-called calcimimetics (33, 112). One such calcimimetic, cinacalcet or Sensipar, is in wide clinical use for suppressing severe secondary hyperparathyroidism in patients receiving hemodialysis treatment for chronic kidney disease (CKD), as described in more detail below. The physiological significance of the CaSR's activation by amino acids is uncertain, but it occurs at physiologically relevant levels of the latter and may coordinate protein/amino acid and calcium metabolism (33). Calcimimetics bind to the CaSR's TMD, while amino acids bind to the ECD, likely close to one of the key binding sites for Cao2+ (71). Calcilytics, allosteric inhibitors of the CaSR, have also been developed (56); they bind at a site in the TMD that is thought to overlap with that for calcimimetics. While calcimimetics may stabilize the CaSR's active conformation, calcilytics likely do just the opposite, stabilizing its inactive conformation.

Role of CaSR in Parathyroid Glands

The CaSR controls three important aspects of parathyroid function relevant to the kidney: 1) PTH secretion, 2) PTH synthesis, and 3) parathyroid cellular proliferation (19). Individuals homozygous for inactivating CaSR mutations (126) and mice homozygous for targeted inactivation of the CaSR gene (68) have markedly elevated PTH levels and parathyroid hyperplasia despite their marked hypercalcemia. Therefore, the CaSR tonically inhibits both PTH secretion and parathyroid cellular proliferation. The CaSR also controls expression of the PTH gene by a posttranscriptional mechanism (92). The receptor may also indirectly inhibit parathyroid function by upregulating the VDR, as noted above, thereby potentiating the inhibitory actions of 1,25(OH)2D3 on parathyroid cellular proliferation and PTH gene expression (50).

CaSR and the Kidney

After the identification of the CaSR in bovine parathyroid in 1993, Hebert and Brown hypothesized the existence of a similar mechanism within the kidney. The idea stemmed from earlier work carried out in the late eighties by Takaichi and Kurokawa (see Refs. 20, 151). These authors demonstrated that, in isolated nephron segments, high ambient Ca2+ inhibits second messenger production evoked by the peptide hormones vasopressin, glucagon, PTH, and calcitonin in segments from the thick ascending limb (TAL) of Henle's loop. Because such an inhibition was pertussis toxin sensitive and was not dependent on extracellular Ca2+ influx, the authors hypothesized the existence of a Gi-linked “calcium receptor” similar to that proposed by Nemeth and Scarpa (110) in 1987 at the surface of bovine parathyroid cells. In addition, Brown and coworkers (40) had previously shown that, in normal human subjects in whom PTH is clamped, acute changes in serum Ca2+ concentrations affect Ca2+, Mg2+, and Na+ excretion. On the basis of these observations, Brown, Hebert, and coworkers hypothesized the existence of a renal CaSR. By the time the molecular cloning of the bovine parathyroid receptor became public knowledge (1993), further work by this group had already identified a cDNA encoding a rat kidney CaSR with homology cloning (137).

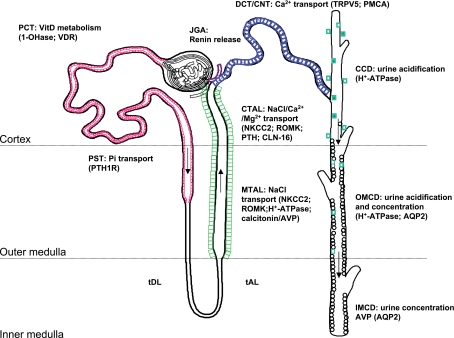

Studies carried out in the Hebert laboratory using in situ hybridization, RT-PCR of isolated nephron segments, and Northern blot analysis revealed, surprisingly, that receptor mRNA was present not only in the TAL but throughout the kidney and, specifically, in regions not known to play a role in Ca2+ metabolism (136). Thus the hypothesis of a role for the CaSR beyond the Cao2+ homeostatic system began to emerge and opened an entirely new field of research in CaSR biology. Subsequently, immunohistochemical studies using anti-CaSR polyclonal antibodies confirmed the widespread distribution of the CaSR along the nephron (135) and demonstrated another unique feature of this receptor: CaSR cellular polarization appeared to be segment specific (135). Indeed, the CaSR protein is luminal in the proximal tubule and collecting duct and basolateral in the TAL of Henle's loop (Fig. 1). While to date it is unclear how this region-specific cellular targeting is achieved, this unique distribution pattern suggested that the receptor is capable of detecting changes occurring both within the urinary space and in the interstitial plasma. Such a feature allows for an integration of multiple signals, permitting fast-acting and local “fine-tuning” of physiological processes without the necessity to evoke systemic changes in plasma composition. Studies performed over the past decade have clearly demonstrated that the CaSR plays an essential role in divalent cation homeostasis by modulating the actions of PTH in the kidney. However, more recent observations show that activation of the CaSR can directly affect many aspects of renal function. From studies using CaSR-knockout mice, isolated nephron segments, and kidney-derived cell lines, it is now apparent that CaSR plays a role in the renal control of 1) Ca/inorganic phosphate (Pi) homeostasis (7); 2) mono- and divalent cation transport (65); 3) urinary acidification (133); 4) urine concentration (133, 142); and 5) renin release (11, 96). While the indirect roles of the CaSR in regulating renal function have been extensively covered elsewhere (152), this review emphasizes direct effects of CaSR activation on renal function.

Fig. 1.

Intrarenal localization and roles of the calcium-sensing receptor (CaSR). Cellular polarity of the CaSR is apical [in the proximal tubule and outer/inner medullary collecting duct (OMCD/IMCD)] and basolateral [in the thick ascending limb (TAL) and, occasionally, in the cortical collecting duct (CCD)]. Species differences exist in the distal convoluted tubule (DCT)/connecting segment (CNT), where receptor expression can be detected apically and/or basolaterally/intracellularly. PCT/PST, proximal convoluted/straight tubule; tDL/tAL, thin discending/ascending limb; MTAL/CTAL, medullary/cortical thick ascending limb; JGA: juxtaglomerular apparatus; TRPV5, transient receptor potential vanilloid 5; PMCA, plasma membrane Ca2+-ATPase; VitD, vitamin D; VDR, vitamin D receptor; NKCC2, Na+-K+-2Cl− cotransporter 2; ROMK, renal outer medullary potassium K+ channel; PTH, parathyroid hormone; AQP2, aquaporin 2.

CaSR in proximal tubule.

The CaSR is present in the subapical region of proximal tubular cells (135), where it is involved in the regulation of PTH-mediated Pi excretion (7). Studies carried out in proximal tubule-derived cell lines also suggest that 1α-hydroxylase activity is inhibited in the presence of high Ca2+ (97). Recent studies carried out with a murine model in which the full-length CaSR has been ablated (and that expresses an exon 5-less splice variant, therefore representing a “hypomorph” in some tissues) have shown that CaSR dampens the response to 1,25(OH)2D3 independently of PTH actions (39). Thus CaSR exerts a tight control on circulating 1,25(OH)2D3 both at the level of its synthesis (in the proximal tubule) and in modulating its effects (specifically, on calcium reabsorption by the distal tubule, see below). Conversely, 1,25(OH)2D3 (22), PTH, and dietary phosphate modulate both CaSR gene and protein expression in the proximal tubule (138), suggesting the existence of a local feedback loop for the regulation of Cao2+ and Pi excretion independently of systemic changes in calciotropic hormones.

CaSR in TAL of Henle's loop.

About 20–25% of the filtered calcium is reabsorbed in the loop of Henle, largely by the cortical (CTAL) and, to a lesser extent, by the medullary (MTAL) thick ascending limb, through both transcellular and paracellular routes (65). The CaSR is expressed at the basolateral side of TAL cells, where it directly controls both paracellular and transcellular NaCl and divalent cation transport. Basolateral, but not urinary, increases in plasma Ca2+ (or Mg2+) concentrations diminish their own reabsorption (128). Indeed, in the TAL, the bulk of the divalent cation reabsorption proceeds through the paracellular pathway and is proportional to the transtubular electrochemical driving force (35). This, in turn, is heavily reliant on the rate and extent of Na+ reabsorption. Seminal work done in the Hebert laboratory (64, 65) has been instrumental in understanding the key molecular players involved in Na+, Cl−, and K+ transport by the TAL and the modulatory role played by the CaSR in this nephron segment. The apical Na+-K+-2Cl− cotransporter NKCC2 (SLC12A2) and the renal outer medullary potassium K+ (ROMK) channel (Kir1.1, Kcnj1) generate the “driving force” for paracellular cation transport (64). While NaCl reabsorption through NKCC2 is electroneutral (NKCC2 translocates 1 Na+, 1 K+, and 2 Cl− ions from the lumen into the cell), apical K+ represents the rate-limiting step of this process and K+ ions back-diffuse into the lumen through the ROMK channels (65). Na+ and Cl− accumulated inside the cell are then transported into the bloodstream through basolateral Na+-K+-ATPase and Cl− channels, respectively. Overall, these processes yield a net cellular reabsorption of NaCl and the generation of a lumen-positive transepithelial potential difference, which drives nonselective cation reabsorption (largely Ca2+ and Mg2+ but also Na+) through the paracellular route (65).

During hypercalcemia, activation of the basolateral CaSR inhibits ROMK channels (164), which contribute to the recycling of K+ into the lumen of the TAL (14). This action of hypercalcemia limits the rate of Na+-K+-2Cl− cotransport by reducing the availability of luminal K+. Thus the greater the hypercalcemia, the greater is the inhibition of ROMK and NKCC2 and the faster the dissipation of the lumen-positive transepithelial voltage. The end point result is that CaSR activation abrogates paracellular Na+, Ca2+, and Mg2+ transport, producing a “Bartter-like” phenotype (159). The signaling pathways underpinning the inhibitory effects of CaSR activation on NKCC2 and ROMK activities involve, at least in part, production of P-450 metabolites and/or of prostaglandins (66, 163, 164). In addition, Mg2+ is largely reabsorbed in the TAL (129), and mutations in claudin-16 (CLDN-16), an integral component of the tight junctional complex in this nephron segment, cause familial hypomagnesemia with hypercalciuria (146). Thus in the TAL CLDN-16 acts as the “gatekeeper” for paracellular Mg2+ transport. Recent studies have demonstrated that the CaSR agonists Ca2+, Mg2+, neomycin, and Gd3+ induce lysosomal translocation of CLN-16 in Madin-Darby canine kidney (MDCK) cells, a model for TAL/distal tubule, thus enhancing its degradation and further contributing to a reduction in Mg2+ transport (73).

In the MTAL water permeability is minimal because of the absence of luminal aquaporins, and water reabsorption does not follow paracellular divalent cation movements. The reduced permeability of this nephron segment would yield a rapid increase in basolateral NaCl and/or Ca2+/Mg2+ concentration, which could inhibit NKCC2, ROMK, and, possibly, CLN-16 (see above). However, an increase in ionic strength (as would occur in the event of increased transport of NaCl into the basolateral fluid) reduces CaSR affinity for Ca2+ (132), and allows for paracellular mono- and divalent cation movements to occur even in the face of a rise in basolateral Ca2+ concentration.

Furthermore, it is well established that the TAL is also involved in the active reabsorption of NH4+, both via NKCC2, where NH4+ can replace K+ on the cotransporter (3), and, as for other cations, through the transepithelial, potential difference (PD)-driven, paracellular route (84). Since CaSR affinity for Ca2+ and Mg2+ is also affected by pH (with alkalinization increasing it and acidification decreasing it) (131), in the TAL the receptor integrates signals deriving from an increase in basolateral Ca2+ concentration with the acid content of the medullary interstitium. While it is well established that acidification affects Ca2+ solubility and excretion, further work is necessary to elucidate the link between CaSR activation and urinary pH. In this nephron segment CaSR activation has also been reported to induce apical H+ secretion in mouse TAL (44). Whether modulation of CaSR function affects the reabsorption of NH4+ and/or of HCO3− through inhibition of the sodium/hydrogen exchangers NHE1/NHE3 (24, 54) and/or of the anion exchanger AE2 (130) is currently unknown.

Finally, in the CTAL PTH evokes transcellular calcium transport (48) . Studies carried out by Friedman and coworkers (49, 107) have demonstrated that CaSR activation with Gd3+ or neomycin inhibits PTH-stimulated apical Ca2+ entry, possibly through protein kinase A and C signaling. Basolateral Ca2+ exit is likely to occur through a Na+/Ca2+ exchanger (NCX) and the plasma membrane Ca2+-ATPase (PMCA). In purified membranes of MDCK cells expressing the CaSR, high Ca2+ suppresses PMCA activity (12). Together, these observations suggest that CaSR activation in the TAL controls both the apical and the basolateral components of transcellular Ca2+ movements. These concerted actions allow for an active, regulated reabsorption while minimizing the risks of intracellular Ca2+ overload.

CaSR in distal convoluted tubule.

The distal convoluted tubule (DCT) and connecting tubule (CNT) account for ∼15% of total Ca2+ reabsorbed by the kidney, and calcium reabsorption in these nephron segments is inversely related to Na+ transport. In DCT and CNT, the transepithelial PD is against Ca2+ reabsorption and the paracellular permeability of Ca2+ ions is very low (48). Ca2+ reabsorption is an active, transcellular process, which is regulated by PTH and 1,25(OH)2D3 (48, 69). Thus Ca2+ ions enter the apical membrane through the epithelial Ca2+ channel transient receptor potential vanilloid member 5 (TRPV5) and are shuttled toward the basolateral membrane by calbindin D28K (69). Ca2+ then leaves the cell via extrusion through the Na+/Ca2+ exchanger NCX1 and the plasma membrane Ca2+-ATPase PMCA1b (69). The CaSR is present on the basolateral cell surface and intracellularly in rat DCT (135); it is also expressed apically, in a punctuate pattern, in the human DCT (155). Using immunohistochemistry on frozen sections from human kidney tissue, Topala et al. (155) reported colocalization of CaSR with TRPV5 at the apical membrane and in subapical vesicles of DCT and CNT cells. In cell lines overexpressing TRPV5 (or TRPV6) and CaSR, receptor activation increased the activity of TRPV5, but not that of its close homolog TRPV6. Since Ca2+ and Na+ reabsorption are largely coupled in the TAL (see above), increasing Na+ wasting in the urine would enhance Ca2+ delivery to the DCT/CNT. The attendant increase in urinary Ca2+ would activate TRPV5 through stimulation of the CaSR in the DCT/CNT, resulting in an increase in luminal Ca2+ entry (155), and prevent excessive urinary Ca2+ loss in a setting of urinary Na+ wasting in the TAL. Basolateral Ca2+ exit appears to be mediated by NCX and PMCA. Available evidence suggests that at least one of these is controlled by the CaSR (see above). Thus it is likely that the CaSR controls apical Ca2+ influx (70, 155) and/or basolateral exit (70) in the DCT/CNT.

CaSR in collecting ducts.

Some rat (135) and human (Searchfield LE, Riccardi D, unpublished observations) type A intercalated cells of the cortical collecting ducts (CCD) express CaSR immunoreactivity apically, basolaterally, and intracellularly. Since hypercalcemia (and the attendant hypercalciuria) is a known cause for urine acidification, CaSR localization suggests that receptor activation could link between signals deriving from hypercalciuria, acidification, and increased diuresis. In a recent study carried out with the hypercalciuric TRPV5-knockout mouse model, homozygous ablation of TRPV5 yielded the expected hypercalciuria but no kidney stones (133). However, the mice exhibited a marked urinary acidification and increased urine flow. Furthermore, when TRPV5−/− mice were bred with mice lacking the B1 subunit of the H+-ATPase (hence producing a “double knockout”), they manifested severe nephrocalcinosis and died in the first 3 months of life, suggesting that acidification occurred as a compensatory mechanism to ensure adequate solubility of Ca2+ in the urine. Exposure of outer medullary collecting ducts dissected from TRPV5−/− mice to the CaSR agonists Ca2+ and neomycin promoted H+ secretion via H+-ATPase and aquaporin 2 (AQP2) downregulation (133), leading to acidification and polyuria. These effects of CaSR activation on acidification could not be seen in the “double-knockout” TRPV5−/−/B1−/− mice. Together, these experiments indicate that activation of the CaSR induces urine acidification and a reduction in water reabsorption, thereby allowing for urinary Ca2+ excretion to proceed in the presence of a reduced risk of kidney stone formation.

The effects of CaSR activation on urinary concentrating ability are even more obvious in the inner medullary collecting duct (IMCD). It is well established that hypercalcemia can lead to hypercalciuria, urinary concentrating defects, and polyuria, and the IMCD is the site that controls the final production of urine (17). This nephron segment is composed almost exclusively of principal cells, which express apical CaSR (142), where the receptor monitors urinary Ca2+ excretion. Immunohistochemical studies have demonstrated that, in this region, the CaSR colocalizes with the vasopressin-regulated AQP2 water channels (142), but not with AQP3 or 4, which are constitutively expressed at the basolateral membrane. Moreover, exposure of isolated IMCD to Cao2+ concentrations comparable to those seen during hypercalciuria blunts the vasopressin-mediated increase in osmotic water permeability, which is accomplished through apical insertion of endosomes containing AQP2 water channels (142). Furthermore, the authors demonstrated that apical IMCD endosomes contain AQP2, CaSR, and the signaling machinery necessary for apical insertion of this water channel. In addition, chronic hypercalcemia markedly downregulates the expression of APQ2 protein by a posttranscriptional mechanism (141). Subsequent observations made in collecting duct-derived cell lines endogenously expressing the CaSR have shown that these effects of high Ca2+ on AQP2 translocation could be ascribed to CaSR signaling (156). Thus hypercalcemia produces a diuretic-like effect in the TAL and also reduces urinary concentrating ability by acting on the CaSR in the IMCD (65). Disturbances of AQP2 trafficking produce nephrogenic diabetes insipidus, and patients with activating mutations in the CaSR gene can develop severe hypercalciuria with nephrolithiasis and nephrocalcinosis (121). Together, these observations suggest the possibility of using CaSR modulators to alter AQP2 targeting and/or CaSR sensing in patients with abnormal urinary concentrating ability (e.g., nephrogenic diabetes insipidus or cardiovascular disease) (108, 127) or in stone formers.

CaSR in juxtaglomerular apparatus.

A variety of stimuli trigger renin secretion by juxtaglomerular (JG) cells of the lamina media of the afferent arteriole (9), largely through production of intracellular cAMP (11). Recent evidence suggests that the CaSR is expressed in JG cells and that activation of the receptor decreases renin secretion by suppressing the activity of the Ca2+-inhibitable type V adenylate cyclase (AC-V) (115), and through stimulation of calcium/calmodulin-activated phosphodiesterases (114). Several earlier studies had shown that decreases in Cao2+ concentration produce large increases in basal and stimulated renin release (47). While significant changes in Ca2+ concentration in the renal cortical interstitium are unlikely under normal circumstances, other factors, such as an increase in the distal delivery of NaCl or sustained acidification, could affect renin production and/or secretion through modulation of CaSR function. This hypothesis is consistent with the phenotype of those patients affected by Bartter syndrome type V, who exhibit increased circulating levels of renin and aldosterone and normal to low blood pressure as a consequence of activating CaSR mutations (166).

Role of CaSR in Other Tissues Participating in Cao2+ Homeostasis

Additional tissues that participate in Cao2+ homeostasis are the thyroidal C cells and CaSR-expressing cells of the intestines, bone, lactating breast, and placenta. The CaSR in the C cell mediates a Cao2+-evoked, homeostatically appropriate stimulation of the hypocalcemic hormone CT (78), although CT's hypocalcemic action is much greater in some species (i.e., rodents) than in humans. A recent review by Hebert and Geibel (52) summarized the CaSR's various roles in the gastrointestinal tract. In the stomach, it stimulates gastric acid and gastrin secretion; in the small intestine, it enhances cholecystokinin release, which stimulates pancreatic enzyme secretion and gallbladder contraction. In the colon, it enhances differentiation of colonocytes (thereby reducing colonic neoplasia in some settings) (77) and inhibits fluid and electrolyte secretion, which could potentially serve as a treatment for diarrheal disease (52). The CaSR may also mediate known actions of Cao2+ to upregulate proteins participating in duodenal intestinal Ca2+ absorption in vivo (157), although the CaSR's involvement and the physiological relevance of these actions are uncertain.

The CaSR's presence and roles in bone cells have been controversial (for review, see Ref. 32). However, recent evidence strongly supports the receptor's expression in osteoclast precursors and mature osteoclasts as well as in preosteoblasts and osteoblasts. While the CaSR appears to serve a permissive role in osteoclastogenesis, high Cao2+ concentrations (5–20 mM) directly inhibit osteoclast activity and stimulate their apoptosis (106). How the receptor mediates both stimulatory and inhibitory effects on cells of the osteoclast lineage is uncertain. In osteoblasts, the CaSR is mitogenic for preosteoblasts, promotes cellular differentiation, and enhances bone formation in vitro and in vivo (26, 37). Thus high Cao2+ stimulates bone formation and inhibits bone resorption in a homeostatically appropriate manner. The CaSR participates in fetal Cao2+ homeostasis by regulating placental calcium transfer (86). Recent studies have also highlighted the CaSR's previously unrecognized roles in the lactating breast, where it both stimulates transport of Ca2+ into the milk and inhibits secretion of the bone-resorbing, Cao2+-elevating hormone PTH-related protein (PTHrP) when blood Ca2+ levels are sufficient to support elaboration of Ca2+-rich milk (158).

Role of CaSR in Integrating Cao2+ Homeostasis

The Cao2+ homeostatic system has three key components: 1) cells, tissues, and organs transporting Ca2+ into or out of the ECF [kidney, intestine and bone (and, in some stages of the life cycle, placenta and breast)]; 2) hormones regulating these fluxes [PTH, CT, PTHrP, and 1,25(OH)2D3]; and 3) Cao2+ sensors (principally the CaSR) controlling the production/secretion of those hormones or the Ca2+ fluxes themselves. During hypercalcemia, for example, high Cao2+ inhibits PTH secretion and 1,25(OH)2D3 synthesis and stimulates CT secretion. The increase in CT inhibits bone resorption. The increase in Cao2+ and the resultant decrease in PTH secretion, through their combined actions on osteoclasts and osteoblasts, promote net movement of Ca2+ into bone while also enhancing renal Ca2+ excretion by inhibiting distal tubular Ca2+ reabsorption (165). The reduction in 1,25(OH)2D3 decreases Ca2+ reabsorption in DCT, suppresses bone resorption by inhibiting 1,25(OH)2D3-stimulated, osteoblast-mediated bone resorption, and diminishes intestinal Ca2+ absorption. The resultant decrease in net Ca2+ release from bone, combined with reductions in intestinal absorption and renal tubular reabsorption of Ca2+, normalizes Cao2+. The homeostatic response to hypocalcemia involves largely opposite changes in the processes just described.

Inherited and Acquired Disorders Impacting Function of CaSR in Kidney

Table 2 describes conditions impacting the CaSR in the kidney.

Table 2.

Conditions impacting the CaSR in the kidney

| Type of Condition | Name | Biological Effects |

|---|---|---|

| 1. Genetic diseases with CaSR dysfunction in all CaSR-expressing tissues |

|

|

| 2. Polymorphisms in the CaSR gene* |

|

|

| 3. Acquired disorders with CaSR dysfunction in multiple tissues |

|

|

| 4. Primary renal dysfunction impacting the CaSR in the kidney | Renal insufficiency | Reduced CaSR expression‡ and hypocalciuria |

| 5. Modulation of CaSR by endogenous ligands | Hypercalcemia | Urinary concentrating defect, hypercalciuria, and ↓1,25(OH)2D3§ synthesis. |

FHH, familial hypocalciuric hypercalcemia; NHPT, neonatal hyperparathyroidism; NSHPT, neonatal severe primary hyperparathyroidism; ADH, autosomal dominant hypoparathyroidism; AHH, autoimmune hypocalciuric hypercalcemia; Cao2+, extracellular calcium; HPT, hyperparathyroidism; PHPT, primary HPT;

For additional examples of the impact of polymorphisms on CaSR function, see text.

Impact on renal calcium handling not known.

Level of expression determined in rats with experimental renal insufficiency, not known in human renal disease.

Decrease in 1,25(OH)2D3 probably results indirectly from CaSR inhibition of PTH secretion as well as through direct inhibition of 1-hydroxylase by CaSR in proximal tubule.

Familial hypocalciuric hypercalcemia.

Familial hypocalciuric hypercalcemia (FHH) is a benign, autosomal dominant form of hypercalcemia with characteristic abnormalities in the regulation of parathyroid and renal function by Cao2+ (91, 102). It is caused in most cases by heterozygous inactivating mutations of the CaSR gene, which resides on the long arm of chromosome 3 (3q13.3–q21) [also called hypocalciuric hypercalcemia, familial, type 1 (HHC1, 145980) in the Online Mendelian Inheritance in Man (OMIM)]. Missense mutations are most common, but nonsense, insertion, deletion, and splice site mutations also occur. Most families have their own unique mutation, and well over 100 such mutations have been described (see calcium-sensing receptor database at http://www.casrdb.mcgill.ca/). About 30% of FHH families do not have an identifiable mutation in the coding region of the CaSR or within RNA splice sites of the gene. Some probably harbor mutations in the CaSR gene's regulatory regions controlling its expression, although no such mutations have been discovered to date. Two families with clinical features similar to FHH showed linkage to the short (19p13.3) (HHC2, OMIM 145981) or long (19q13) arms of chromosome 19 (63, 95), respectively. FHH linked to chromosome 19q13 is called the Oklahoma variant (HHC3, OMIM 600740); this form of FHH exhibits overtly elevated PTH levels, and the biochemical abnormalities tend to worsen with time (95). Thus FHH is genetically heterogeneous.

FHH patients typically exhibit asymptomatic, mild-to-moderate, PTH-dependent hypercalcemia of ∼11 mg/dl (total calcium) and an inappropriately normal or even overtly low urinary Ca2+ excretion despite their hypercalcemia (91, 101, 102). Serum Mg2+ levels are often high-normal or mildly elevated, suggesting that the CaSR contributes to “setting” Mgo2+ as well as Cao2+ (150). Serum PTH is generally normal, although ∼15–20% of patients have elevated levels (62). Serum phosphate is usually normal or mildly decreased, and serum 1,25(OH)2D3 (89) and bone mineral density (BMD) are normal, although bone turnover markers may be mildly elevated (91). Because of its benign natural history and the prompt recurrence of hypercalcemia in patients with FHH following anything less than total parathyroidectomy, the standard of care is expectant follow-up without medical or surgical intervention. Only in rare FHH families does unusually severe neonatal hypercalcemia (see below) (8), pancreatitis (122), or hypercalciuria and overtly elevated serum PTH levels (25) dictate parathyroidectomy.

The inappropriately normal (i.e., nonsuppressed) PTH level in FHH reflects a right shift in the set point for Cao2+-regulated PTH release (i.e., the level of Cao2+ half-maximally inhibiting PTH release) (5, 80). This “resetting” of parathyroid function contributes importantly to the pathogenesis of hypercalcemia in FHH (19). Not surprisingly, the parathyroid glands of patients with FHH either are normal or exhibit subtle hyperplasia (90, 153). How can a normal PTH level and near normal parathyroid mass in FHH sustain hypercalcemia? The answer likely lies in the “collaboration” between the alteration in Cao2+-regulated PTH release and the characteristically avid renal Ca2+ (and Mg2+) reabsorption described below. Consequently, less PTH is needed to maintain a given degree of hypercalcemia in FHH than in primary hyperparathyroidism (PHPT).

There is a substantial reduction in renal Ca2+ clearance in FHH, and the ratio of Ca2+ clearance to creatinine clearance, the most useful parameter of renal Ca2+ handling in this condition, is <0.01 in ∼80% of patients. About 80% of patients with PHPT, in contrast, have values >0.01 and commonly >0.02 (29, 101). Mg2+ clearance is reduced but to a lesser degree (∼30%) in FHH (101). Thus even with a degree of hypercalcemia comparable to mild to moderate PHPT and a lower PTH level than in the latter, FHH patients excrete less Ca2+ at any given level of serum Ca2+.

Attie et al. (4), in a now-classic study, investigated renal Ca2+ handling in hypoparathyroid FHH patients or hypoparathyroid control subjects at various serum Ca2+ concentrations. Because the FHH patients and control subjects were both hypoparathyroid, there were no confounding changes in parathyroid function during the study that could impact renal Ca2+ handling. There was a marked rightward and downward shift in the relationship between serum and urine Ca2+ (e.g., the set point for Cao2+-regulated renal Ca2+ excretion) in FHH patients. Of note, there was a decrease in not only the calciuric but also the natriuretic response to Ca2+ infusion in the hypoparathyroid FHH patients (4). This likely reflects reduced CaSR activity in the TAL and is consistent with the “signature” of linked cation handling in this nephron segment (e.g., Na+, Ca2+, and Mg2+) in CTAL described previously (65). Indeed, the loop diuretic ethacrynic acid, which inhibits the NKCC in the TAL, produced an exaggerated calciuric response in the FHH patients (4), suggesting the relevance of excessively avid Ca2+ reabsorption in TAL to the hypocalciuria in FHH.

Renal water handling is also altered in FHH. As noted above, raising luminal Cao2+ in the IMCD substantially inhibits vasopressin-stimulated water flow (141, 142), owing to activation of the apical CaSR. In a study comparing water handling in patients with FHH to those with PHPT, the latter showed an ∼20% reduction in their maximal urinary concentration during an 18- to 22-h dehydration test compared with FHH patients with a similar degree of hypercalcemia (103). This study illustrates “resistance” of the urinary concentrating mechanism, most likely in the IMCD, to hypercalcemia in FHH. A reduction in the CaSR-mediated, inhibitory action of hypercalcemia on NaCl reabsorption in MTAL in FHH patients may also contribute to their normal or near normal urinary concentrating ability despite their hypercalcemia (65).

Neonatal severe primary hyperparathyroidism.

Neonatal severe primary hyperparathyroidism (NSHPT) (OMIM 239200) typically presents in the first 6 months of life (57, 58, 104, 134), often in the immediate neonatal period, with severe, symptomatic, PTH-dependent hypercalcemia and the bony changes of severe hyperparathyroidism. Infants with NSHPT can also manifest polyuria, dehydration, hypotonia, and failure to thrive (38, 59, 104). The bone disease can produce multiple fractures of long bones, ribs (sometimes impairing respiration), and other sites (38). Total serum Ca2+ levels range from moderately elevated (e.g., ∼12–14 mg/dl) to as high as 25–30 mg/dl (19, 59, 85, 104). PTH levels are frequently 10-fold or more above the upper normal limit. NSHPT is most commonly caused by homozygous (58, 125, 126) or, rarely, compound heterozygous mutations in the CaSR gene (85) (in the latter, an infant inherits one inactivating CaSR mutation from one parent and a second from the other). There is relative or absolute hypocalciuria in NSHPT (30, 104), although Ca2+ excretion can be elevated in some cases, presumably owing to the markedly increased filtered load of Ca2+.

Early diagnosis is critical, as untreated NSHPT can have a fatal outcome or severe impairment of subsequent mental, skeletal, and somatic growth without parathyroidectomy to alleviate the hyperparathyroidism and hypercalcemia (30, 61). Total parathyroidectomy produces hypoparathyroidism; thus hypercalcemia in NSHPT is PTH dependent, and loss of Ca2+ receptors in tissues other than the parathyroid (e.g., kidney, C cell) is insufficient to sustain hypercalcemia. A potentially useful temporizing measure in a severely ill neonate with NSHPT is the use of a bisphosphonate such as pamidronate, which can lower serum Ca2+ concentration substantially and allow stabilization before surgery, if the latter is indicated (46, 162). Remission of hyperparathyroidism after parathyroidectomy produces rapid clinical improvement and healing of bony lesions within weeks to months; the prognosis thereafter is usually excellent (31, 61, 67, 148).

Some neonates have a substantially milder clinical presentation (61, 120), a condition termed neonatal hyperparathyroidism (NHPT) to emphasize this milder phenotype (19, 119). Infants with NHPT can harbor heterozygous inactivating CaSR mutations. In some cases a mutation exerting a dominant-negative action may produce NHPT rather than the benign FHH phenotype otherwise expected with heterozygous inactivating CaSR mutations (120). Over time, NHPT can revert to FHH with only routine medical follow-up (60, 61). Parathyroidectomy should be reserved for severely affected NHPT infants, in whom substantial hypercalcemia and/or hyperparathyroid bone disease persist despite intensive medical treatment. Such cases, however, are the exception rather than the rule.

The marked increases in circulating PTH level despite severe hypercalcemia in NSHPT demonstrate a severe defect in Cao2+-regulated PTH secretion, with potentially total or near total failure of suppression of secretion at high Cao2+ (67, 104). Two in vitro studies have addressed this point, utilizing parathyroid tissue from two cases of NSHPT undergoing parathyroidectomy. In the first case (100), Cao2+-regulated-PTH secretion from dispersed parathyroid cells revealed a set point of 2.5 mM, more than twice the normal value of 1 mM. In the second case, there was minimal suppressibility of PTH secretion at 2.0 mM Cao2+ (34).

There are also limited data on the relationship between serum and urinary Ca2+ concentrations in NSHPT. In the cases in which it has been measured, there can be relative or absolute hypocalciuria, or sometimes hypercalciuria, as noted above. Two patients with homozygous CaSR mutations escaped detection until adulthood (1, 28) and are particularly instructive. Both patients had serum Ca2+ of 15–17 mg/dl, hypermagnesemia (in one case; Ref. 1), overt hypophosphatemia, and a PTH level in the upper normal range in one case and frankly elevated in the other. There were decreases in the urinary calcium-to-creatinine clearance ratio comparable to FHH, and renal function was normal. The lack of the usual hypercalcemic renal complications in these cases suggests that several of the known effects of hypercalcemia on renal function, including hypercalciuria, impaired urinary concentrating capacity, and reduction in glomerular filtration rate (GFR) (in fact, FHH patients have a higher GFR than patients with PHPT) (101), can apparently be ascribed to the CaSR. The milder clinical presentation in these cases of “NSHPT” diagnosed in adulthood was likely due to mutant CaSRs with less functional impairment than is the norm in FHH (28).

The development of mice with targeted inactivation (“knockout” or KO) of the CaSR has provided useful models of FHH and NSHPT (68). The heterozygous CaSR KO mouse is a model of FHH, exhibiting mild hypercalcemia and elevations in PTH and relative hypocalciuria. This model provides strong evidence that a reduced complement of normal CaSRs can cause the Cao2+-resistance of FHH because, based on immunohistochemistry or Western blotting, the levels of the CaSR in parathyroid and kidney were both reduced ∼50% (68). Homozygous CaSR KO mice have an NSHPT phenotype, exhibiting severe hypercalcemia and hyperparathyroidism and dying within a few weeks of birth. The further use of these mice or those with conditional KO of the CaSR (26) in parathyroid and/or kidney will provide useful models to study the impact of reduced CaSR expression on the function of parathyroid and kidney (and other tissues) in vivo and in vitro.

Autosomal dominant hypoparathyroidism.

Patients with activating CaSR mutations have an often asymptomatic, autosomal dominant form of hypocalcemia/hypoparathyroidism (58, 67, 121). Some, however, manifest neuromuscular irritability, basal ganglia calcification, and seizures, complications observed in hypoparathyroidism of other causes (121). Patients with autosomal dominant hypoparathyroidism (ADH) (OMIM 601298) exhibit mild-moderate hypocalcemia, with low-normal or frankly subnormal PTH levels (119). Untreated ADH patients frequently have relative (i.e., inappropriately normal given their hypocalcemia) or absolute hypercalciuria (10, 121, 168). In several studies, urinary Ca2+ excretion in untreated ADH patients was about twice that in other forms of hypoparathyroidism (10, 121, 168). ADH, therefore, can be thought of as the mirror image of FHH, i.e., familial hypercalciuric hypocalcemia.

ADH is caused by heterozygous [or, in one case, homozygous (94)] activating mutations of the CaSR that increase the receptor's sensitivity to Cao2+ rather than, with rare exceptions, producing constitutive activation. Thus the Cao2+ homeostatic system is “reset,” including CaSR-regulated PTH secretion, which exhibits a decrease in set point, to maintain and defend a subnormal serum Ca2+ level. Conceptually, one would anticipate a leftward shift in the relationship between Cao2+ and urinary Ca2+ excretion in ADH analogous to the reduced parathyroid set point. As noted above, some studies have found a higher level of urinary Ca2+ excretion in untreated ADH cases than in other types of hypoparathyroidism (121, 168). In contrast, Yamamoto et al. (169) also reported greater urinary Ca2+ excretion rate in untreated ADH patients than in other hypoparathyroid subjects but found that the relationship between the serum Ca2+ and urinary Ca2+/creatinine during treatment did not differ between the two groups. It remains to be seen whether this observation will be replicated in other studies investigating Cao2+ sensing by the kidney in ADH.

Patients with ADH are prone to encounter renal complications during treatment with Ca2+ and vitamin D analogs aimed at increasing serum Ca2+ concentration toward normal (121), although there are no studies formally documenting this difference between ADH patients and other hypoparathyroid patients. These complications include nephrolithiasis, nephrocalcinosis, and reversible or, in some cases, irreversible renal impairment (118). One study (118) described four affected ADH patients who developed long-term, apparently irreversible decreases in renal function, with creatinine clearances of 30 ml/min or less during treatment with calcium and vitamin D supplementation. The renal complications developing during treatment of ADH may occur when serum Ca2+ concentration has been elevated close to or to within the lower range of normal but not higher. Treatment with Ca2+ supplements and 1,25(OH)2D3 should only be used in symptomatic ADH patients; the goal is to elevate the serum Ca2+ just to the level that alleviates symptoms (93). Renal Ca2+ excretion should be carefully monitored to minimize the risk of renal complications. If raising serum Ca2+ to the level at which symptoms are alleviated cannot be achieved without frank hypercalciuria (generally 4 mg·kg−1·24 h−1), coadministration of a hypocalciuric agent, such as a thiazide diuretic or injectable PTH administered once or twice daily, may be needed (168).

Bartter syndrome with activating CaSR mutations.

Several patients have been reported with activating CaSR mutations and features of Bartter syndrome (a syndrome referred to as Bartter syndrome, type V) (159, 166). In addition to the typical features of ADH, these patients also exhibited hypokalemia with renal K+ wasting, hyperreninemia, and hyperaldosteronemia. These patients’ mutant CaSRs exhibited markedly left-shifted Ca2+ concentration-response curves. It was postulated that these unusually active mutant CaSRs inhibited paracellular reabsorption of Na+, Ca2+, and Mg2+ in TAL. Activation of the CaSR in typical ADH only enhances urinary calcium and magnesium excretion. However, with the Bartter variant, there is also apparently sufficient volume depletion to cause hyperreninemia, hyperaldosteronism, and resultant renal K+ loss.

Inactivating and Activating Autoantibodies to CaSR

About a dozen patients have been described with inactivating (83, 98, 116) or activating (79, 82) autoantibodies directed at the CaSR. Inactivating antibodies cause autoimmune hypocalciuric hypercalcemia (AHH). These patients have PTH-dependent hypercalcemia in the setting of other autoimmune conditions (e.g., Hashimoto thyroiditis) and, in most reported cases, exhibit hypocalciuria; all harbor anti-CaSR antibodies detected by various immunologic tests (e.g., ELISA, Western blot, etc.). In one study of four AHH patients, the anti-CaSR antibodies blunted CaSR-mediated activation of PLC and MAPK activity at physiological levels of Cao2+ (83). As expected for an inactivating antibody, PTH release from parathyroid cells incubated with patient sera was higher at any given level of Ca2+ relative to cells incubated with control sera. In another AHH patient, the anti-CaSR antibodies unexpectedly potentiated high Cao2+-evoked PLC activity (i.e., had CaSR activating properties) but blunted MAPK activation (98), suggesting differential coupling of the antibody-bound receptor to these two signaling pathways. In some of the cases described to date, the autoantibodies likely interact with the CaSR in the kidney, thereby producing relative or absolute hypocalciuria despite hypercalcemia, as in FHH (83, 116). Thus inactivating antibodies can produce a clinical and biochemical picture similar to that caused by inactivating mutations in FHH. A small percentage (6.7%) of patients with PHPT harbored anti-CaSR antibodies in one study (27); the functional properties of these antibodies were not examined.

Anti-parathyroid antibodies and, more recently, anti-CaSR antibodies have been identified in patients with autoimmune or idiopathic hypoparathyroidism (for review, see Ref. 18). However, the functional properties of the anti-CaSR antibodies have been studied in only a few cases. Four patients to date have been shown to have antibodies that activate the CaSR with methods similar to those used to characterize inactivating antibodies (79, 82). These antibodies suppressed PTH secretion in vitro in association with activation of ERK1/2 and PLC, but the activity of these antibodies on the kidney, if any, is unknown.

Impact of Acquired Forms of Hypercalcemia on CaSR

Two common biochemical abnormalities involving the kidney in hypercalcemic patients are hypercalciuria and impaired urinary concentrating ability (17, 65). In hypercalcemic patients, activation of the renal CaSR by hypercalcemia will reduce tubular reabsorption of Ca2+ in the TAL (65, 165). The resultant hypercalciuria is more marked in patients with etiologies of hypercalcemia leading to suppressed PTH than in those with hyperparathyroidism, since PTH stimulates Ca2+ reabsorption (this action is shared by PTHrP, but, nevertheless, patients with PTHrP-mediated hypercalcemia tend to have marked hypercalciuria) (149). Severe and prolonged hypercalcemia can eventually lead to nephrolithiasis, nephrocalcinosis, and renal impairment (17), but it is difficult to predict who will develop these complications and when. Hypercalcemia would also be expected to inhibit salt reabsorption in MTAL, thereby “washing out” the hypertonic medullary interstitium (65). The reduction in the countercurrent gradient, combined with the inhibitory effect of the CaSR on vasopressin-stimulated water reabsorption in the IMCD (142), will impair urinary concentrating ability. While diminished urinary concentrating capacity is a “classic” hypercalcemic complication, its true prevalence is uncertain. Impaired reabsorption of NaCl in the TAL combined with anorexia, nausea, and defective urinary concentrating ability likely all participate in varying measure in the volume depletion seen in some severely hypercalcemic patients. Whether other actions of hypercalcemia on the kidney, such as reduced GFR and renal blood flow (41), are CaSR mediated is unknown, although FHH patients have a higher GFR than comparably hypercalcemic patients with PHPT, suggesting a mediatory role of the CaSR in regulating GFR (103).

CaSR in Kidney in Renal Disease

Kidney disease alters the expression and function of the CaSR (and VDR) in the parathyroid, which, along with other factors, leads to secondary (and sometimes tertiary) hyperparathyroidism (55). This leads to deranged mineral ion and skeletal homeostasis and resultant morbidity, mortality, and expense to the health care system. The availability of calcimimetics that suppress secondary hyperparathyroidism in patients with stage 5 CKD (i.e., requiring dialysis) has provided a new addition to the therapeutic armamentarium in this setting (13, 36). The literature on this rapidly moving subject is large and has been reviewed in detail elsewhere (36, 55).

There has been little in the way of systematic study of the CaSR in the kidney in renal diseases and associated changes in CaSR-regulated renal function. A study utilizing experimentally induced renal failure in rats reported reduced renal CaSR expression but did not describe where the decrease took place (105). Reduced CaSR expression might contribute to the reduced renal calcium excretion in renal insufficiency as a result of a decrease in CaSR-evoked renal Ca2+ excretion.

Impact of CaSR Polymorphisms on the Kidney

Several studies have examined the possible impact of single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) in the CaSR on Cao2+ homeostasis and related systems, i.e., blood pressure. Several are relevant to renal function in health and disease. For example, one study found that CaSR SNPs and related haplotypes (a haplotype in this setting is a sequence of SNPs on a single strand of DNA) were a determinant of the normal range of serum Ca2+ concentration in the population (143). This normal range is greater that that measured in any given individual. Indeed, certain haplotypes of SNPs at positions 986, 990, and 1011 in the CaSR's C tail were significantly associated with higher or lower serum ionized Ca2+ concentration within the normal range, and accounted for 17% of the variation in the normal range (143). In some cases, other groups have had discordant results with regard to the A986S polymorphism (15), perhaps because of small sample size or populations with differing frequencies of the SNPs. Clearly additional studies with larger sample sizes in well-characterized populations are needed.

The impact of CaSR SNPs on parameters related to renal function/dysfunction has also been studied. Having two glycine residues at position 990, instead of the more common alanine, has been associated with 1) lower PTH levels in hemodialysis patients (170), 2) hypercalciuria (161), and 3) greater suppressibility of PTH during induced hypercalcemia in hemodialysis patients (172). In another study, there was a greater risk of stone disease in patients with PHPT and the ACG haplotype at positions 986, 990, and 1011 (160). Some associations of SNPs with traits relevant to the kidney have involved noncoding SNPs (those present in introns or the promoter of the CaSR gene), perhaps by modifying receptor expression. In African Americans in the Indianapolis area, three SNPs were associated with systolic blood pressure and with urinary calcium excretion (75). These same investigators observed an interaction between CaSR, the CLCNKB (the basolateral chloride channel in the thick limb), and NKCC genes that contributed to variation in diastolic blood pressure, perhaps through changes in sodium and/or calcium transport in the TAL (76). These results indicate that the SNPs within the CaSR and other genes with which it interacts in the kidney could be a fruitful avenue of investigation. The availability of very large databases, with ∼1,000,000 SNPs for genomewide association studies (GWAS) should be very helpful in this regard.

CaSR-Based Therapeutics: Renal Implications

The development of allosteric CaSR activators (“calcimimetics”) (112) and antagonists (“calcilytics”) (56) has enabled novel, CaSR-based therapy of disorders of calcium homeostasis. Cinacalcet hydrochloride (also known as Sensipar) was approved in 2004 by the FDA for treating severe secondary hyperparathyroidism in stage 5 kidney disease (13) as well as parathyroid cancer (145). Studies in experimental animals have suggested that administration of a calcimimetic in uremic animals reduces some of the long-term complications of this condition, including progression of renal impairment, atherosclerosis (74), and, in combination with vitamin D treatment, mortality (140). Studies are currently in progress in humans assessing the efficacy of the drug in decreasing cardiovascular disease and mortality. The drug also effectively lowers serum calcium concentration in mild primary hyperparathyroidism, but it has not received FDA approval for this indication, although it is approved for use in PHPT in Europe (117). The drug has been utilized in several other, “off-label” uses. Some may end up simply as “orphan” applications in very limited patient populations. Others may represent significant advances that will improve patient care in certain clinical settings. The drug has been used to control hypercalcemia/hyperparathyroidism in patients with renal insufficiency, other than in stage 5. One application is the use of the drug to treat hyperparathyroidism in CKD before dialysis. Although cinacalcet lowers PTH in this setting (45), it also modestly lowers serum calcium and increases serum phosphate. The utility of the drug in this setting is currently unclear. A potentially valuable application is in the treatment of PTH-dependent hypercalcemia following renal transplantation (87). Cinacalcet restores normocalcemia in ∼80% of such patients, with few adverse effects, except for occasional hypercalciuria (42) and mild, generally reversible, reductions in graft function in some patients.

Cinacalcet has been administered to patients with lithium-induced hyperparathyroidism (147), which is a form of PHPT. Although clinical experience with this application is very limited, correction of hypercalcemia has been observed. A drop in serum calcium has been observed in FHH after administration of cinacalcet (154), which is not unexpected since most mutant CaSRs are responsive to the drug. However, this application may be limited to rare FHH patients in whom lowering an unusually elevated PTH or serum calcium level or treatment of a potential complication, such as pancreatitis, is desirable, since the vast majority of FHH patients should simply be followed medically.

Cinacalcet has also been used in a limited number of patients with X-linked hypophosphatemia (2) or oncogenic osteomalacia (53), both of which have hypophosphatemia mediated by an excess of the phosphaturic hormone FGF-23. In this setting oral phosphate administration in four daily doses can induce secondary hyperparathyroidism, which aggravates the phosphate wasting owing to the phosphaturic action of PTH. In some cases, this secondary hyperparathyroidism progresses to hypercalcemic, “tertiary” hyperparathyroidism (139). The utility of the drug in this setting is to suppress this iatrogenic hyperparathyroidism, particularly when administered with 1,25(OH)2D3. Finally, in animal models of polycystic kidney disease, administration of a calcimimetic inhibits late-stage cyst growth, suggesting a possible use of the drug in human polycystic kidney disease (51). A striking feature of the use of cinacalcet to date is the lack of evidence of activation of the CaSR in other organs outside of the parathyroid, with the exception of the hypercalciuria in some patients receiving the drug after renal transplant, which could represent a direct effect on the CaSR in CTAL.

Cao2+ receptor antagonists, so-called calcilytics, are also in development and are presently in clinical trials. The inhibitory action of the calcilytic on the CaSR has the consequence that a higher than normal level of Cao2+ is required to suppress PTH levels (56, 111). That is, the CaSR reads normocalcemia as hypocalcemia and secretes a pulse of PTH. When exogenous PTH is injected once daily, it exerts an anabolic action on the skeleton, and it is the most effective anabolic drug available for treating osteoporosis (109). Clinical trials are investigating whether once- or twice-daily oral administration of a calcilytic has a similar therapeutic effect by releasing a pulse of endogenous PTH. It is also conceivable that a longer-acting calcilytic could be used in the treatment of ADH or ADH with Bartter features. Right-shifting the activation of the mutant CaSR by extracellular Ca2+ could produce a more normal set point for Cao2+-regulated PTH release and urinary Ca2+ excretion in this setting. An analogous approach to treating hypercalciuric renal stones would be the use of a calcilytic with some specificty for the kidney, so as to induce “FHH of the kidney,” thereby reducing urinary calcium excretion without stimulating PTH release.

Conclusions and Future Directions

Recent evidence suggests that the kidney CaSR directly regulates a variety of aspects of renal fluid and electrolyte handling, urinary acidification, and blood pressure control. In addition, there are a number of inherited and acquired conditions in which the level of expression and/or function of the CaSR are altered, thereby directly or indirectly impacting the function of the kidney. Current CaSR therapeutics (e.g., calcimimetics) on the market are proving very effective at modulating receptor function in patients with primary and secondary hyperparathyroidism. Future studies will need to investigate the application of these drugs to other conditions with abnormal Cao2+ sensing by the parathyroid as well as whether it is possible to develop CaSR therapeutics with some specificity for the kidney, thereby enabling modulation of abnormal renal Cao2+ sensing.

GRANTS

D. Riccardi thanks the Biotechnology and Biological Sciences Research Council (BBSRC; grant no. BB/D01591X) for funding her work and the members of her laboratory for stimulating discussions. E. M. Brown thanks the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases for current grant support (DK-078331).

DISCLOSURES

D. Riccardi received a grant from Amgen. E. M. Brown has a financial interest in the calcimimetic cinacalcet.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This article celebrates the life and the scientific achievements of our friend, the late Dr. Steven Hebert. Other articles in this series include Gamba G. The thiazide-sensitive Na+-Cl− cotransporter: molecular biology, functional properties, and regulation by WNKs. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 297: F838–F848, 2009 and Welling PA, Ho K. A comprehensive guide to the ROMK potassium channel: form and function in health and disease. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 297: F849–F863, 2009.

REFERENCES

- 1.Aida K, Koishi S, Inoue M, Nakazato M, Tawata M, Onaya T. Familial hypocalciuric hypercalcemia associated with mutation in the human Ca2+-sensing receptor gene. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 80: 2594–2598, 1995 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Alon US, Levy-Olomucki R, Moore WV, Stubbs J, Liu S, Quarles LD. Calcimimetics as an adjuvant treatment for familial hypophosphatemic rickets. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 3: 658–664, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Amlal H, Paillard M, Bichara M. Cl−-dependent NH4+ transport mechanisms in medullary thick ascending limb cells. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 267: C1607–C1615, 1994 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Attie MF, Gill J, Jr, Stock JL, Spiegel AM, Downs RW, Jr, Levine MA, Marx SJ. Urinary calcium excretion in familial hypocalciuric hypercalcemia. Persistence of relative hypocalciuria after induction of hypoparathyroidism. J Clin Invest 72: 667–676, 1983 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Auwerx J, Demedts M, Bouillon R. Altered parathyroid set point to calcium in familial hypocalciuric hypercalcaemia. Acta Endocrinologica (Copenh) 106: 215–218, 1984 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Awata H, Huang C, Handlogten ME, Miller RT. Interaction of the calcium-sensing receptor and filamin, a potential scaffolding protein. J Biol Chem 276: 34871–34879, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ba J, Brown D, Friedman PA. Calcium-sensing receptor regulation of PTH-inhibitable proximal tubule phosphate transport. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 285: F1233–F1243, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bai M, Pearce SH, Kifor O, Trivedi S, Stauffer UG, Thakker RV, Brown EM, Steinmann B. In vivo and in vitro characterization of neonatal hyperparathyroidism resulting from a de novo, heterozygous mutation in the Ca2+-sensing receptor gene: normal maternal calcium homeostasis as a cause of secondary hyperparathyroidism in familial benign hypocalciuric hypercalcemia. J Clin Invest 99: 88–96, 1997 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Barajas L. Anatomy of the juxtaglomerular apparatus. Am J Physiol Renal Fluid Electrolyte Physiol 237: F333–F343, 1979 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Baron J, Winer KK, Yanovski JA, Cunningham AW, Laue L, Zimmerman D, Cutler GB., Jr Mutations in the Ca2+-sensing receptor gene cause autosomal dominant and sporadic hypoparathyroidism. Hum Mol Genet 5: 601–606, 1996 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Beierwaltes WH. The role of calcium in the regulation of renin secretion. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 298: F1–F11, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Blankenship KA, Williams JJ, Lawrence MS, McLeish KR, Dean WL, Arthur JM. The calcium-sensing receptor regulates calcium absorption in MDCK cells by inhibition of PMCA. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 280: F815–F822, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Block GA, Martin KJ, de Francisco AL, Turner SA, Avram MM, Suranyi MG, Hercz G, Cunningham J, Abu-Alfa AK, Messa P, Coyne DW, Locatelli F, Cohen RM, Evenepoel P, Moe SM, Fournier A, Braun J, McCary LC, Zani VJ, Olson KA, Drüeke TB, Goodman WG. Cinacalcet for secondary hyperparathyroidism in patients receiving hemodialysis. N Engl J Med 350: 1516–1525, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Boim MA, Ho K, Shuck ME, Bienkowski MJ, Block JH, Slightom JL, Yang Y, Brenner BM, Hebert SC. ROMK inwardly rectifying ATP-sensitive K+ channel. II. Cloning and distribution of alternative forms. Am J Physiol Renal Fluid Electrolyte Physiol 268: F1132–F1140, 1995 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bollerslev J, Wilson SG, Dick IM, Devine A, Dhaliwal SS, Prince RL. Calcium-sensing receptor gene polymorphism A986S does not predict serum calcium level, bone mineral density, calcaneal ultrasound indices, or fracture rate in a large cohort of elderly women. Calcif Tissue Int 74: 12–17, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Brauner-Osborne H, Wellendorph P, Jensen AA. Structure, pharmacology and therapeutic prospects of family C G-protein coupled receptors. Curr Drug Targets 8: 169–184, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bringhurst FR, Demay MB, Kronenberg HM. Hormones and disorders of mineral metabolism. In: Williams's Textbook of Endocrinology (9th ed.), edited by Wilson JD, Foster DW, Kronenberg HM, Larsen PR. Philadelphia: Saunders, 1998, p. 1155–1209 [Google Scholar]

- 18.Brown EM. Anti-parathyroid and anti-calcium sensing receptor antibodies in autoimmune hypoparathyroidism. Endocrinol Metab Clin North Am 38: 437–445, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Brown EM. Clinical lessons from the calcium-sensing receptor. Nat Clin Pract Endocrinol Metab 3: 122–133, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Brown EM. Extracellular Ca2+ sensing, regulation of parathyroid cell function, and role of Ca2+ and other ions as extracellular (first) messengers. Physiol Rev 71: 371–411, 1991 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Brown EM, Gamba G, Riccardi D, Lombardi M, Butters R, Kifor O, Sun A, Hediger MA, Lytton J, Hebert SC. Cloning and characterization of an extracellular Ca2+-sensing receptor from bovine parathyroid. Nature 366: 575–580, 1993 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Canaff L, Hendy GN. Human calcium-sensing receptor gene. Vitamin D response elements in promoters P1 and P2 confer transcriptional responsiveness to 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D. J Biol Chem 277: 30337–30350, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Canaff L, Zhou X, Hendy GN. The proinflammatory cytokine, interleukin-6, up-regulates calcium-sensing receptor gene transcription via Stat1/3 and Sp1/3. J Biol Chem 283: 13586–13600, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Capasso G, Rizzo M, Pica A, Di Maio FS, Moe OW, Alpern RJ, De Santo NG. Bicarbonate reabsorption and NHE-3 expression: abundance and activity are increased in Henle's loop of remnant rats. Kidney Int 62: 2126–2135, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Carling T, Szabo E, Bai M, Ridefelt P, Westin G, Gustavsson P, Trivedi S, Hellman P, Brown EM, Dahl N, Rastad J. Familial hypercalcemia and hypercalciuria caused by a novel mutation in the cytoplasmic tail of the calcium receptor. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 85: 2042–2047, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Chang W, Tu C, Chen TH, Bikle D, Shoback D. The extracellular calcium-sensing receptor (CaSR) is a critical modulator of skeletal development. Sci Signal 1: ra1, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Charrie A, Chikh K, Peix JL, Berger N, Decaussin M, Veber S, Bienvenu J, Lifante JC, Fabien N. Calcium-sensing receptor autoantibodies in primary hyperparathyroidism. Clin Chim Acta 406: 94–97, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Chikatsu N, Fukumoto S, Suzawa M, Tanaka Y, Takeuchi Y, Takeda S, Tamura Y, Matsumoto T, Fujita T. An adult patient with severe hypercalcaemia and hypocalciuria due to a novel homozygous inactivating mutation of calcium-sensing receptor. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf) 50: 537–543, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Christensen SE, Nissen PH, Vestergaard P, Heickendorff L, Brixen K, Mosekilde L. Discriminative power of three indices of renal calcium excretion for the distinction between familial hypocalciuric hypercalcaemia and primary hyperparathyroidism: a follow-up study on methods. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf) 69: 713–720, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Cole DE, Janicic N, Salisbury SR, Hendy GN. Neonatal severe hyperparathyroidism, secondary hyperparathyroidism, and familial hypocalciuric hypercalcemia: multiple different phenotypes associated with an inactivating Alu insertion mutation of the calcium- sensing receptor gene. Am J Med Genet 71: 202–210, 1997. [Erratum. Am J Med Genet 72: October 17, 1997, p. 251–252.] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Cole DE, Quamme GA. Inherited disorders of renal magnesium handling. J Am Soc Nephrol 11: 1937–1947, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Collins MT, Skarulis MC, Bilezikian JP, Silverberg SJ, Spiegel AM, Marx SJ. Treatment of hypercalcemia secondary to parathyroid carcinoma with a novel calcimimetic agent. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 83: 1083–1088, 1998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Conigrave AD, Mun HC, Brennan SC. Physiological significance of l-amino acid sensing by extracellular Ca2+-sensing receptors. Biochem Soc Trans 35: 1195–1198, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Cooper L, Wertheimer J, Levey R, Brown E, Leboff M, Wilkinson R, Anast CS. Severe primary hyperparathyroidism in a neonate with two hypercalcemic parents: management with parathyroidectomy and heterotopic autotransplantation. Pediatrics 78: 263–268, 1986 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Di Stefano A, Wittner M, Nitschke R, Braitsch R, Greger R, Bailly C, Amiel C, Roinel N, de Rouffignac C. Effects of parathyroid hormone and calcitonin on Na+, Cl−, K+, Mg2+, and Ca2+ transport in cortical and medullary thick ascending limbs of mouse kidney. Pflügers Arch 417: 161–167, 1990 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Drueke TB, Ritz E. Treatment of secondary hyperparathyroidism in CKD patients with cinacalcet and/or vitamin D derivatives. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 4: 234–241, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Dvorak MM, Siddiqua A, Ward DT, Carter DH, Dallas SL, Nemeth EF, Riccardi D. Physiological changes in extracellular calcium concentration directly control osteoblast function in the absence of calciotropic hormones. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 101: 5140–5145, 2004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Eftekhari F, Yousefzadeh D. Primary infantile hyperparathyroidism: clinical, laboratory, and radiographic features in 21 cases. Skeletal Radiol 8: 201–208, 1982 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Egbuna O, Quinn S, Kantham L, Butters R, Pang J, Pollak M, Goltzman D, Brown E. The full-length calcium-sensing receptor dampens the calcemic response to 1alpha,25(OH)2 vitamin D3 in vivo independent of parathyroid hormone. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 297: F720–F728, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.el-Hajj Fuleihan G, Seifter J, Scott J, Brown EM. Calcium-regulated renal calcium handling in healthy men: relationship to sodium handling. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 83: 2366–2372, 1998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Epstein F. Calcium and the kidney. Am J Med 45: 700–713, 1968 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Esposito L, Rostaing L, Gennero I, Mehrenberger M, Durand D, Kamar N. Hypercalciuria induced by a high dose of cinacalcet in a renal-transplant recipient. Clin Nephrol 68: 245–248, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Fan GF, Ray K, Zhao XM, Goldsmith PK, Spiegel AM. Mutational analysis of the cysteines in the extracellular domain of the human Ca2+ receptor: effects on cell surface expression, dimerization and signal transduction. FEBS Lett 436: 353–356, 1998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Farajov EI, Morimoto T, Aslanova UF, Kumagai N, Sugawara N, Kondo Y. Calcium-sensing receptor stimulates luminal K+-dependent H+ excretion in medullary thick ascending limbs of Henle's loop of mouse kidney. Tohoku J Exp Med 216: 7–15, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Fournier A, Shahapuni I, Harbouche L, Monge M. Calcimimetics for predialysis patients? Am J Kidney Dis 47: 196–107, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Fox L, Sadowsky J, Pringle KP, Kidd A, Murdoch J, Cole DE, Wiltshire E. Neonatal hyperparathyroidism and pamidronate therapy in an extremely premature infant. Pediatrics 120: e1350–e1354, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Fray JC, Park CS, Valentine AN. Calcium and the control of renin secretion. Endocr Rev 8: 53–93, 1987 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Friedman PA. Calcium transport in the kidney. Curr Opin Nephrol Hypertens 8: 589–595, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Friedman PA, Coutermarsh BA, Kennedy SM, Gesek FA. Parathyroid hormone stimulation of calcium transport is mediated by dual signaling mechanisms involving protein kinase A and protein kinase C. Endocrinology 137: 13–20, 1996 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]