Abstract

CFTR is a highly regulated apical chloride channel of epithelial cells that is mutated in cystic fibrosis (CF). In this study, we characterized the apical stability and intracellular trafficking of wild-type and mutant CFTR in its native environment, i.e., highly differentiated primary human airway epithelial (HAE) cultures. We labeled the apical pool of CFTR and subsequently visualized the protein in intracellular compartments. CFTR moved from the apical surface to endosomes and then efficiently recycled back to the surface. CFTR endocytosis occurred more slowly in polarized than in nonpolarized HAE cells or in a polarized epithelial cell line. The most common mutation in CF, ΔF508 CFTR, was rescued from endoplasmic reticulum retention by low-temperature incubation but transited from the apical membrane to endocytic compartments more rapidly and recycled less efficiently than wild-type CFTR. Incubation with small-molecule correctors resulted in ΔF508 CFTR at the apical membrane but did not restore apical stability. To stabilize the mutant protein at the apical membrane, we found that the dynamin inhibitor Dynasore and the cholesterol-extracting agent cyclodextrin dramatically reduced internalization of ΔF508, whereas the proteasomal inhibitor MG-132 completely blocked endocytosis of ΔF508. On examination of intrinsic properties of CFTR that may affect its apical stability, we found that N-linked oligosaccharides were not necessary for transport to the apical membrane but were required for efficient apical recycling and, therefore, influenced the turnover of surface CFTR. Thus apical stability of CFTR in its native environment is affected by properties of the protein and modulation of endocytic trafficking.

Keywords: cystic fibrosis, ΔF508, protein trafficking, turnover, polarized cells

cystic fibrosis (CF) is caused by mutations in the CFTR gene (34, 37). CFTR functions as a highly regulated, cAMP-activated chloride channel at the apical membrane of epithelial cells of airway, intestine, sweat duct, pancreas, kidney, testis, and other tissues (34, 37, 48, 49). Although CF affects a multitude of tissues, it is most severely manifested as airway disease (7, 48). The chloride channel CFTR has been shown to regulate several other transport proteins, such as the epithelial sodium channel. In CF, the defect in chloride secretion and consequent NaCl hyperabsorption lead to a depletion of airway surface liquid and a secondary breakdown of mucociliary clearance (3, 18). This results in bacterial infections, inflammation, damage to airway tissue, and impairment of lung function. Although major improvements in the care of CF patients have raised life expectancy, there is no cure for CF, and it remains the most common lethal genetic disease in the Caucasian population.

The epithelial membrane protein CFTR is core-glycosylated cotranslationally at the endoplasmic reticulum (ER), transported to the Golgi apparatus for complex glycosylation, and, finally, secreted to the apical surface. Early steps of CFTR biogenesis and degradation at the ER are regulated by complex networks of interactions with chaperones and cochaperones (1, 44). Multiple PDZ proteins that interact with the PDZ domain binding motif at the COOH terminus of CFTR tether the channel to scaffolding proteins in macromolecular complexes at the apical membrane (15). At the plasma membrane, CFTR is subjected to endocytosis (27, 32); however, the majority of internalized wild-type CFTR is recycled to the cell surface. Internalized CFTR resides in early and recycling endosomes, and a small amount is also transferred to late endosomes, multivesicular bodies, and lysosomes for degradation (12, 39).

The most common mutation in CF, ΔF508, causes misfolding and retention of the protein at the ER in its core-glycosylated immature form. Mutant CFTR is subsequently degraded by ER-associated degradation, with the consequence that no protein is transported to the cell surface (19, 33). Therefore, a potential therapeutic approach is to promote the transit of ΔF508 to the plasma membrane. ΔF508 is a temperature-sensitive mutation that can reach the plasma membrane by incubation at low temperature. The rescued protein, however, is thermally unstable and disappears from the cell surface much faster than the wild-type protein (12, 26, 38, 40). When expressed in various nonpolarized cell lines, wild-type CFTR has a half-life of ∼15 h and is efficiently recycled to the plasma membrane (29), whereas temperature-rescued ΔF508 CFTR turns over significantly faster and is directed to lysosomal degradation (12, 39).

In the past few years, high-throughput screening has identified several small-molecule corrector compounds that result in surface expression of some ΔF508 CFTR (30, 35, 41). Correctors with considerable rescue activity include the quinazoline derivative VRT-325 (24, 41) and the methylbithiazole analog Corr-4a (30). Since ΔF508 CFTR is a thermally unstable protein with shortened biochemical and functional half-lives (16, 38), corrector compounds are needed to restore folding, function, and stability of the protein. Unfortunately, limited information is available on the apical stability and endocytic fate of ΔF508 CFTR that has been rescued by small-molecule correctors.

It has been suggested that processing and intracellular trafficking of CFTR vary with cell type and are also affected by epithelial cell polarization (2, 29, 43). It is therefore important and physiologically relevant to study endocytic routing of wild-type and ΔF508 CFTR in highly differentiated primary human airway epithelial (HAE) cells from epithelia directly affected in CF. In nonpolarized heterologous expression systems, ΔF508 CFTR has been shown to be internalized, with an efficiency similar to that of wild-type CFTR, but is recycled less efficiently (39). In contrast, studies using a polarized airway epithelial cell line suggest that ΔF508 CFTR is internalized more rapidly than wild-type CFTR (40). Thus our objective was to perform detailed studies on apical stability, internalization, and recycling of CFTR in physiologically relevant HAE cultures that endogenously express CFTR (20). We therefore expressed wild-type and ΔF508 CFTR with extracellular epitope tags in well-differentiated HAE cultures, labeled the apical pool with an antibody recognizing the epitope tag, and monitored trafficking of the protein over time. Internalization of CFTR occurred more slowly in these cultures than in nonpolarized cells or in a polarized epithelial cell line. Similar to nonpolarized systems, there was a striking difference in apical stability between wild-type and mutant CFTR in this native environment. We further found that N-linked glycans of CFTR possess apical targeting information for the recycling of the protein. Most internalized wild-type CFTR returned to the apical membrane, whereas ΔF508 recycled only with low efficiency. Apical stability of ΔF508 CFTR was not dependent on rescue conditions, i.e., low-temperature or small-molecule correctors, but could be augmented by various approaches that diminished internalization of this mutant chloride channel from the cell surface. These results validate the potential for therapeutic strategies that aim to restore the apical stability of rescued mutant ΔF508 CFTR.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cell culture.

Primary HAE cells were obtained from human lung tissue, as previously described (5, 11), under a protocol approved by the University of North Carolina Medical School Institutional Review Board. Cells were seeded on collagen-coated Millicell CM inserts (Millipore, Bedford, MA) and maintained at an air-liquid interface for 40–45 days, which allowed the cells to become fully differentiated before they were infected by adenoviral vectors to express the CFTR variants. For studies on nonpolarized cells, primary HAE cells were seeded at low density on PureCol (Inamed, Fremont, CA)-coated glass-bottom dishes and grown for 2–4 days.

To allow maturation of the mutant CFTR protein, HAE cells expressing Extope-ΔF508 CFTR were grown at 27°C for 48 h. When ΔF508 CFTR was rescued by incubation at 27°C, wild-type CFTR-expressing cells were incubated at the same temperature.

Modification of extracellular loop 2 in Extope-CFTR.

Extope-CFTR is the term we use to designate CFTR with an externally accessible hemagglutinin (HA) epitope inserted into an extended, modified extracellular loop (EL) 2 that contains sequences from EL1 and EL4 to expose the epitope. The sequence of EL2 in Extope-CFTR is WELNTSYDPDNKGNTYPYDVPDYANSYAVIITSKEERS (for further details on the construction strategy see supplemental materials and methods in the online version of this article).

Viral infection.

HAE cultures were transduced with adenoviral vectors expressing CFTR variants with an HA epitope tag in EL2 (Extope-CFTR) (12). The N-glycosylation mutant has asparagine residues N894 and N900 replaced with aspartate (4). Viral infections were performed as described recently (5, 6), and experiments were carried out 30 h later.

Western blotting.

Cells were washed in ice-cold PBS and lysed with NP-40 lysis buffer (1% NP-40, 150 mM NaCl, 50 mM Tris, and 1 mM EGTA, pH 7.4) with protease inhibitors at a final concentration of 4 μg/ml leupeptin, 8 μg/ml aprotinin, 200 μg/ml Pefabloc, 484 μg/ml benzamidine, and 14 μg/ml E64. Cell lysates were centrifuged at 15,000 g at 4°C, and supernatants were collected. Cell lysates (25 μg) were loaded, separated on 7% SDS-polyacrylamide minigels, and then transferred to nitrocellulose. Blots were probed with anti-CFTR antibodies 596 and 570 (each diluted 1:1,000) or anti-HA antibody HA.11 (1:1,000 dilution) and then with IR Dye 800-goat anti-mouse IgG (1:15,000 dilution; Rockland Immunochemicals, Gilbertsville, PA) in Odyssey Blocking Buffer (LI-COR, Lincoln, NE) with 0.1% Tween 20. Protein bands were visualized using an Odyssey Infrared Imaging System (LI-COR).

Immunofluorescence microscopy.

To study CFTR endocytosis, Extope-CFTR was labeled at the cell surface of nonpolarized HAE cells and the apical surface of HAE cultures with anti-HA MAb HA.11 (1:100 dilution; Covance, Berkeley, CA), as we described previously (5, 12). For labeling of Extope-CFTR at the surface of nonpolarized HAE cells, cells were precooled for 10 min on ice, and cell surface Extope-CFTR was labeled with anti-HA MAb for 45 min at 4°C. Cells were then washed with cold PBS and reincubated at 37°C for indicated times. On ciliated, well-differentiated HAE cultures, apical Extope-CFTR was labeled with anti-HA MAb for 45 min at 27°C, unless indicated otherwise. Cells were then reincubated at 37°C for various times and frozen in Tissue-Tek optimal cutting temperature compound (OCT, Sakura Finetek, Torrance, CA), and frozen culture sections were prepared. Nonpolarized cells and culture sections were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde (PFA), permeabilized with 0.1% Triton X-100, and blocked in 10% goat serum in 1% BSA in PBS. Extope-CFTR was detected using Alexa Fluor 488-goat anti-mouse IgG conjugate (1:500 dilution; Molecular Probes, Eugene, OR). For nuclear staining, we applied TO-PRO-3 iodide (1:1,000 dilution). Cells were visualized using a Plan-Apochromat ×63/1.4 numerical aperture oil differential interference contrast objective on a confocal laser scanning microscope (model LSM 510, Zeiss). Excitation was at 488 nm using an argon laser with a BP505–530 emission filter or at 633 nm using a helium-neon laser with an LP650 emission filter. Differential interference contrast and fluorescence images were obtained simultaneously. The pinhole setting was 1 Airy unit.

For colocalization studies of endocytic Extope-CFTR with early endosomal antigen-1 (EEA-1) on frozen sections of HAE cells expressing wild-type CFTR, we labeled internalized Extope-CFTR as described above; then we applied rabbit anti-EEA-1 (Affinity BioReagents, Rockford, IL) antibodies (1:500 dilution) followed by Alexa Fluor 568-goat anti-mouse IgG (1:500 dilution; Molecular Probes) to detect EEA-1. To stain lysosmes, we applied LysoTracker Red (Molecular Probes) according to the instructions of the manufacturer. Excitation on the laser scanning microscope (model LSM 510, Zeiss) was at 543 nm using a helium-neon laser with an LP585 emission filter.

For colocalization studies of Extope-CFTR with basolateral markers, fixed frozen sections of HAE cells expressing wild-type or N-glycosylation mutant CFTR were washed in 1% SDS in potassium-free PBS twice for 5 min before blocking. Antibody TEFS-2 against the basolateral protein sodium-potassium-chloride cotransporter (NKCC) isoform 1 (1:1,000 dilution) was followed by Alexa Fluor 555-goat anti-mouse IgG (1:500 dilution; Molecular Probes). Excitation on laser scanning microscope (model LSM 510, Zeiss) was at 543 nm using a helium-neon laser with an LP585 emission filter.

Isotype-specific secondary antibodies were applied to costain the remaining endocytic CFTR, which had been labeled with HA.11 antibody at the apical cell surface 16 h before application of the secondary antibodies, and all CFTR pools. CFTR that had been labeled at the apical membrane 16 h earlier was detected with goat anti-mouse IgG1 conjugated to Alexa 568, whereas all CFTR pools were detected with anti-CFTR antibody 596 followed by goat anti-mouse IgG2b conjugated to Alexa 488. All confocal microscopy experiments were performed on HAE cultures from at least three different subjects.

On-Cell Western assay.

Primary HAE cells were seeded on collagen-coated Millicell CM inserts (12 mm diameter) and maintained at an air-liquid interface for 40–45 days, allowing the cells to become fully differentiated before they were infected with adenoviral vectors to express the CFTR variants. Apical Extope-CFTR was labeled with HA.11 for 45 min at 27°C, unless indicated otherwise. Cells were reincubated at 37°C for various times and then fixed with 4% PFA, but not permeabilized, blocked with 1% BSA and 10% goat serum in PBS, and stained with IR Dye 800-goat anti-mouse IgG (Rockland Immunochemicals). Fluorescence of wild-type and ΔF508 CFTR at the apical cell surface was quantified with the LI-COR Odyssey Infrared Imaging System. The plastic feet of Millicells, which suspend the membrane insert above the base of the media-containing dish, were removed, and membranes were placed directly on the LI-COR Odyssey Infrared Imaging Scanner and scanned with an excitation wavelength of 780 nm. The resolution was insufficient to resolve individual cells but allowed accurate measurements of changes in surface CFTR quantity between HAE cultures reincubated for different times. Resulting images demonstrated very low background noise, which is typical of infrared immunofluorescence due to reduced autofluorescence and scattering at this wavelength. Scans were quantified using Odyssey Infrared Imaging System Application Software version 3.0.16.

Recycling assay.

Extope-CFTR or ΔF508 was labeled with antibody 12CA5 overnight at 27°C and then left untreated, quickly washed with PBS (pH 3.5) to remove apically bound antibodies, or washed with PBS (pH 3.5) and chased for 5 min, 20 min, or 1 h at 37°C. CFTR that reappeared at the apical surface was quantified on fixed (4% PFA, 10 min) cultures by On-Cell Western assay with goat anti-mouse IgG-IR Dye 800 conjugate using the LI-COR Odyssey Infrared Imaging System. In addition, cultures were frozen after different chase times, and culture sections were fixed (4% PFA, 10 min), permeabilized (0.1% Triton X-100, 10 min), blocked (1% BSA, 10% goat serum in PBS), and stained (goat anti-mouse IgG-Alexa 488 conjugate) for visualization of intracellular redistribution of CFTR. Sections were mounted and examined by confocal immunofluorescence microscopy.

Drug treatments.

HAE cells expressing ΔF508 CFTR were grown at 37°C in the presence of the quinazoline compound VRT-325 and the bisaminomethylbithiazole compound Corr-4a (each at 10 μM) for 48 h and then labeled and chased at 37°C with the compounds. HAE cells expressing temperature-rescued ΔF508 were pretreated with Dynasore (80 μM) for 1 h or with MG-132 (10 μM) or methyl-β-cyclodextrin (10 mM) for 30 min at 27°C, labeled with anti-HA antibody in the presence of drug, and then chased for 5 h at 37°C in the presence of drug. Absence of methyl-β-cyclodextrin during the chase was also examined.

RESULTS

Internalization of CFTR is slower from the apical surface of primary HAE cultures than from the plasma membrane of nonpolarized cells.

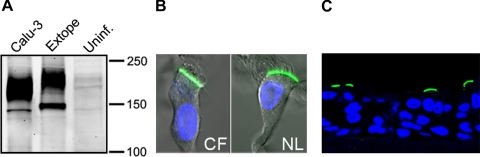

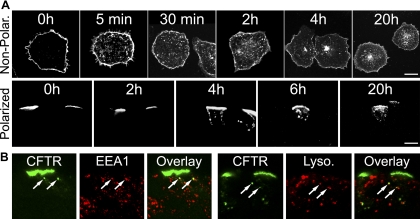

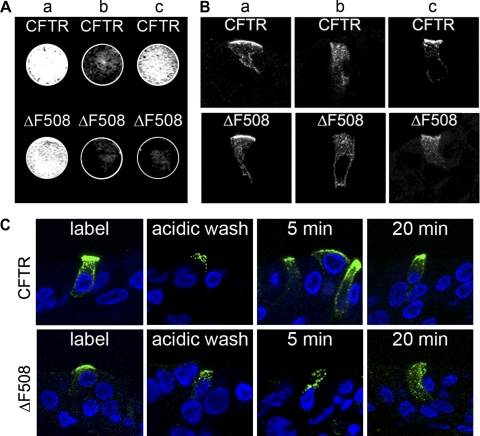

We first focused our studies on the internalization of wild-type CFTR from the apical membrane of highly differentiated primary HAE cultures. We employed adenoviral vectors with a CFTR construct containing an extracellular epitope tag (Extope-CFTR) (12) and transduced well-differentiated ciliated primary human airway (HAE) cultures (Fig. 1A). Immunostaining of virally expressed CFTR verified that the chloride channel was sorted correctly to the apical membrane independent of the genetic background (CF or normal) of the culture (Fig. 1B). We then labeled exclusively the apical pool of CFTR with an antibody recognizing the external tag on intact HAE cultures and visualized apical CFTR on frozen culture sections (Fig. 1C). Reincubation of cultures with CFTR labeled at the cell surface enabled the tracking of internalization and turnover of endocytosed CFTR over time, as we showed previously in nonpolarized cells (12). We found that internalization of CFTR occurred more slowly in differentiated primary HAE cultures than in nonpolarized cells (Fig. 2A). In well-differentiated HAE cells, CFTR did not appear in endocytic vesicles until 4 h after labeling; however, our confocal immunofluorescence experiments may not precisely resolve apical membrane vs. subapical vesicles. With use of this method for visualizing internalized CFTR in nonpolarized HAE cells, CFTR was detectable in endocytic vesicles as early as 5 min after labeling (Fig. 2A). In polarized and nonpolarized HAE cells, a considerable amount of the protein was still visible at the cell surface 20 h after labeling.

Fig. 1.

Expression of extracellularly epitope-tagged CFTR in highly differentiated human airway epithelial (HAE) cell cultures. A: fully differentiated primary HAE cultures were adenovirally transduced with Extope-CFTR (Extope), which is externally tagged, and lysates were analyzed by Western blotting with anti-CFTR MAb 596. Lysates from Calu-3 and HAE cultures that remained uninfected (Uninf) are shown as controls. B: Extope-CFTR was detected in primary HAE cultures from lungs from cystic fibrosis (CF) patients or normal (NL) subjects. Immunostaining was performed on isolated cells using MAb HA.11, which recognizes the extracellular hemagglutinin (HA) tag, followed by Alexa Fluor 488-goat anti-mouse IgG conjugate. Immunofluorescence is shown in overlay with differential interference contrast and nuclear staining by TO-PRO-3 iodide. C: Extope-CFTR was labeled at the apical surface of intact cultures with anti-HA antibody and detected on frozen culture sections using Alexa Fluor 488-goat anti-mouse IgG conjugate. Confocal immunofluorescence was performed on ≥3 different cultures derived from different subjects; 1 representative example is shown.

Fig. 2.

Internalization and subcellular localization of CFTR in HAE cultures. A: cell surface pools of Extope-CFTR were labeled with anti-HA MAb, and cells were reincubated for indicated times. Internalized pools of Extope-CFTR were detected with Alexa Fluor 488-goat anti-mouse IgG conjugate on nonpolarized fixed HAE cells (Non-Polar) and fixed frozen culture sections of highly differentiated HAE cells (Polarized). Scale bars, 10 μm. B: at 6 h in A, early endosomal antigen (EEA)-1 was coimmunostained with anti-rabbit antibodies and then with Alexa Fluor 568-goat anti-rabbit IgG, and lysosomes were stained with LysoTracker Red (Lyso). Arrows indicate Extope-CFTR-containing vesicles that colocalize with marker proteins. Confocal immunofluorescence was performed on ≥3 different cultures derived from different subjects; 1 representative example is shown.

Using an internalization assay based on cell surface biotinylation, we observed that CFTR internalization occurs faster in the polarized epithelial cell line, CFBE41o−, than in polarized primary HAE cultures (see supplemental Fig. S1). In polarized CFBE41o− cells, a large portion of CFTR was internalized after 5 min at 37°C; in primary HAE cultures, a significant amount of CFTR was not internalized until ≥4 h at 37°C, which is consistent with our microscopy data showing CFTR in endocytic vesicles 4 h after labeling.

As we and others showed previously, the internalized CFTR was first detected in association with EEA-1-containing early endosomes and transferrin-positive recycling compartments and, later, with lysosomal markers (12, 39). Colocalization of endocytic CFTR in differentiated HAE cultures revealed overlap with EEA-1-positive compartments and partial colocalization with lysosomal markers (Fig. 2B).

Low-temperature-rescued ΔF508 CFTR is unstable at the apical membrane of differentiated HAE cultures.

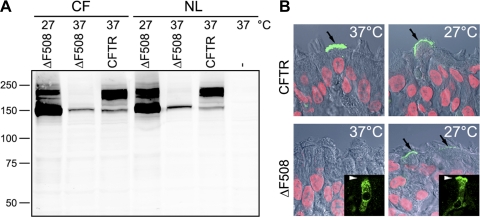

ΔF508 CFTR is a temperature-sensitive mutation that cannot mature conformationally at 37°C but can avoid ER quality control and proceed to the plasma membrane at 27°C (9). To rescue epitope-tagged ΔF508 CFTR by low temperature, we incubated transduced HAE cultures derived from normal or CF tissue for 48 h at 27°C (Fig. 3). Under these conditions, we observed formation of mature protein (Fig. 3A) and expression at the apical membrane in fully differentiated HAE cells (Fig. 3B). We found that the rescued ΔF508 CFTR transits from the apical membrane to the endocytic compartments much more rapidly than wild-type CFTR (Fig. 4). After 1 h, the mutant protein appeared in subapical vesicles, while the wild-type protein was restricted to the apical surface. By 4 h, ΔF508 CFTR was nearly undetectable at the apical membrane, while wild-type CFTR remained associated with the cell surface and began transferring to intracellular vesicles. The internalization of ΔF508 CFTR from the apical membrane did not differ in cells from homozygous ΔF508 patients and non-CF individuals, indicating that the different behavior reflected the genotype of the transduced CFTR and not that of the HAE cultures.

Fig. 3.

ΔF508 CFTR expressed in highly differentiated HAE cells is efficiently rescued by low temperature. A: CF and normal HAE cells were adenovirally transduced with wild-type Extope-CFTR (CFTR) or ΔF508 Extope-CFTR (ΔF508) or remained uninfected (−) and maintained at 27°C or 37°C, and lysates were analyzed by Western blotting. B: cell surface expression of Extope-CFTR variants was visualized in adenovirally transduced HAE cultures by labeling with anti-HA MAb on intact cultures. Immunofluorescence is shown after incubation with Alexa Fluor 488-goat anti-mouse IgG in overlay with differential interference contrast and nuclear staining by propidium iodide. Black arrows indicate apical CFTR. Insets show all cellular pools of ΔF508 CFTR labeled on permeabilized cells with anti-CFTR MAb 596. White arrowheads indicate apical membrane. Confocal immunofluorescence was performed on ≥3 different cultures derived from different subjects; 1 representative example is shown.

Fig. 4.

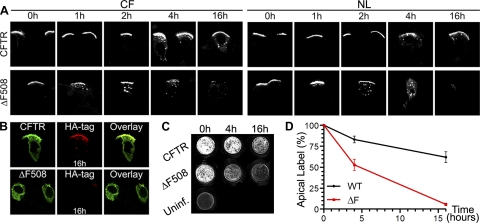

Rescued ΔF508 is less stable than wild-type CFTR at the apical membrane. A: temperature-rescued ΔF508 CFTR disappears faster from the apical membrane and is internalized more rapidly than wild-type CFTR. Extope variants of wild-type and temperature-rescued ΔF508 CFTR were labeled at the cell surface, and HAE cells [CF (ΔF508/ΔF508) and normal] were reincubated for indicated times. Frozen cell sections were prepared, fixed, permeabilized, and incubated with Alexa Fluor 488-goat anti-mouse IgG. Confocal immunofluorescence was performed on ≥3 different cultures derived from different subjects; 1 representative example is shown. B: temperature-rescued ΔF508 CFTR is less stable than wild-type CFTR and after 16 h is no longer detectable at the apical membrane or in endocytic compartments. Apical pools of CFTR were labeled, and cells were reincubated for 16 h. All CFTR pools (CFTR and ΔF508) and remaining CFTR that had been labeled 16 h before at the cell surface (HA-tag, 16h) were then costained using isotype-specific secondary antibodies. C: quantitative analysis of remaining amounts of wild-type and ΔF508 CFTR at the apical membrane by On-Cell Western assay. Apical CFTR was labeled, and HAE cultures were reincubated for indicated times, fixed, but not permeabilized, and stained with IR Dye 800-goat anti-mouse IgG. Remaining fluorescence was quantified with a LI-COR Odyssey Infrared Imaging System after different times on cultures from 7 different subjects; scan of 1 representative experiment is shown. D: quantitative analysis of On-Cell Western assays. Results of 7 independent experiments, each using an HAE culture derived from a different subject, were used to determine mean values for each time point. Error bars, SE. Difference between values for wild-type (WT) and ΔF508 CFTR (ΔF) was statistically significant at 4 h (P = 0.001 by unpaired t-test) and 16 h (P < 0.0001 by unpaired t-test).

To quantify the turnover of mutant and wild-type CFTR at the apical membrane, we performed a fluorescent cell surface (On-Cell Western) assay (Fig. 4C). CFTR was labeled with antibody at the apical surface, and the apical CFTR that remained after different chase times was then determined with a near-infrared fluorescent dye conjugated to secondary antibody using the LI-COR Odyssey Infrared Imaging System. Using this technique, we found that the half-life at the apical membrane was about four to five times shorter for temperature-rescued ΔF508 protein than wild-type CFTR, as determined by quantification of the remaining labeled surface pool over time (Fig. 4, C and D). Although more than half the amount of wild-type protein that had been labeled at the apical membrane was still detectable after 16 h, only ∼5% of mutant protein was detected after the same time period.

Wild-type CFTR recycles efficiently, whereas temperature-rescued ΔF508 CFTR is not able to return to the apical membrane.

We then investigated whether the instability of ΔF508 CFTR at the apical membrane was due to inefficient recycling of the protein back to the apical membrane. To study the recycling behavior of CFTR, apical and intracellular pools of CFTR were labeled by antibody added to the apical side of HAE cultures. Apically bound antibody was removed by a low-pH wash, resulting in label remaining exclusively on CFTR in endocytic vesicles (Fig. 5, Ab and Bb). The recycling of CFTR back to the apical membrane was then investigated by On-Cell Western assays using the LI-COR Odyssey Infrared Imaging System (Fig. 5A) and by confocal immunofluorescence (Fig. 5B). Most internalized wild-type CFTR returned efficiently to the apical membrane after 1 h at 37°C, whereas ΔF508 CFTR did not reach the apical surface and was primarily associated with intracellular vesicles that concentrated toward the subapical compartment (Fig. 5, A and B). A time course with shorter chase times (5 and 20 min) showed that a large proportion of wild-type CFTR transferred from intracellular endocytic compartments to the apical membrane after a 5-min chase (Fig. 5C), whereas the mutant CFTR protein localized exclusively to intracellular endocytic compartments after these chase times.

Fig. 5.

Wild-type CFTR recycles efficiently to the apical membrane, but rescued ΔF508 CFTR does not. A: quantification of CFTR reappearing at the apical surface using a LI-COR Odyssey Infrared Scanner. CFTR was labeled with MAb 12CA5 overnight at 27°C (a), and HAE cultures were rinsed briefly with acidic PBS (pH 3.5) on the apical side to remove apically bound MAbs (b) and chased (1 h, 37°C) after removal of apical label (c). HAE cultures were fixed, and CFTR reappearing at the apical surface was stained with goat anti-mouse IgG-IR Dye 800 conjugate. B: visualization of intracellular distribution of CFTR by confocal immunofluorescene microscopy. Intracellular CFTR was labeled and chased as described in A. At different time points, cultures were quickly frozen, and CFTR distribution was visualized with goat anti-mouse IgG-Alexa Fluor 488 conjugate. C: visualization of intracellular distribution of CFTR after shorter chase times by immunofluorescence micrsocopy. Intracellular CFTR was labeled as described in A. After 5 and 20 min of chase, cultures were quickly frozen, and CFTR distribution was visualized on frozen culture sections with goat anti-mouse IgG-Alexa Fluor 488 conjugate. Confocal immunofluorescence was performed on ≥3 different cultures derived from different subjects; 1 representative example is shown.

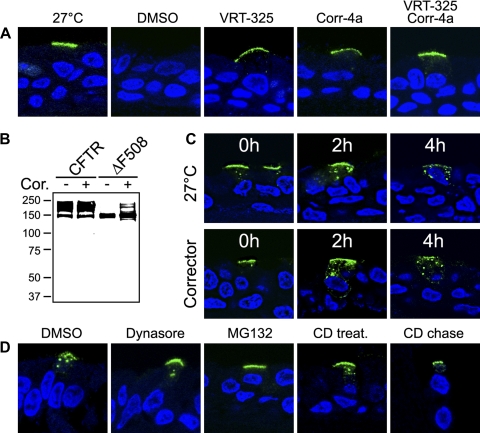

Treatment with corrector compounds results in apical localization of ΔF508 CFTR in differentiated HAE cultures but does not restore apical stability.

To rescue ΔF508 CFTR by means other than low temperature, we employed small-molecule correctors. We treated highly differentiated HAE cultures virally expressing ΔF508 CFTR with the quinazoline compound VRT-325 (24, 41) or the bisaminomethylbithiazole compound Corr-4a (30) for 48 h. Treatment of ΔF508 CFTR-expressing cultures with either corrector allowed detection of apical ΔF508 CFTR (Fig. 6A). Treatment with both correctors simultaneously further enhanced the amount of mutant protein that localized to the cell surface. Rescue of the mutant protein was also confirmed by the appearance of the complex glycosylated form by Western blotting (Fig. 6B). We labeled apical ΔF508 CFTR rescued by these compounds and compared the apical stability with low-temperature-rescued ΔF508 CFTR. We found that mutant protein that has been rescued by VRT-325 and Corr-4a was internalized from the apical membrane as rapidly as the low-temperature-rescued protein (Fig. 6C), suggesting that treatment with these compounds did not significantly increase the apical stability of ΔF508 CFTR.

Fig. 6.

Small-molecule correctors rescue apical expression, but not stability, of ΔF508 CFTR. A: apical expression of ΔF508 CFTR by rescue with correctors VRT-325 and Corr-4a. Cells were treated with vehicle (DMSO) or correctors for 48 h at 37°C and labeled with anti-HA antibody in the presence of DMSO or correctors. Temperature-rescued cells (27°C) were incubated for 48 h at 27°C. Correctors were used at 10 μM. Frozen sections were prepared, and apical CFTR was visualized by secondary Alexa 488 antibody conjugate. TO-PRO-3 was used to stain nuclei. Experiments were performed on ≥3 different HAE cultures; 1 representative example is shown. B: Western blot with lysates of HAE cells adenovirally expressing ΔF508 CFTR that were treated with VRT-325 and Corr-4a (Cor, 10 μM each) for 48 h show formation of complex glycosylated mature CFTR. C: apical stability is not restored by rescue with VRT-325 and Corr-4a. HAE cells virally expressing ΔF508 CFTR were grown at 27°C for 48 h without drug treatment or at 37°C with VRT-325 and Corr-4a (Corrector, 10 μM each) for 48 h. Apical ΔF508 CFTR was labeled for 1 h at 37°C and then chased for 0, 2, or 4 h at 37°C. Corrector compounds were present during the chase. After the chase periods, ΔF508 CFTR was visualized on frozen culture sections. D: inhibition of endocytosis augments apical stability of ΔF508 CFTR. HAE cells grown at 27°C were pretreated with drug or vehicle (DMSO) for 1 h (Dynasore, 80 μM) or 30 min [MG-132 at 10 μM or methyl-β-cyclodextrin (CD) at 10 mM], labeled with anti-HA antibody in the presence of drug or DMSO, and then chased for 5 h at 37°C in the presence of DMSO, Dynasore, MG-132, or CD (CD chase) or in the absence of CD (CD treat). Confocal immunofluorescence was performed on ≥3 different cultures derived from different subjects; 1 representative example is shown.

Remarkably, stabilization of temperature-rescued ΔF508 CFTR could be achieved with the following strategies: blocking endocytosis by Dynasore, inhibiting proteasomal degradation by MG-132, and extracting membrane cholesterol by methyl-β-cyclodextrin (Fig. 6D). Without drug treatment, ΔF508 CFTR was present in endocytic vesicles 5 h after labeling at the apical surface (DMSO). Dynasore, which has been shown to inhibit dynamin-dependent endocytosis by >90% (28), resulted in significant, but not complete, stabilization of the mutant protein at the apical membrane, whereas MG-132 led to a complete inhibition of internalization, as shown by lack of endocytosed ΔF508 CFTR. Methyl-β-cyclodextrin led to a partial arrest of internalization when cells were chased in methyl-β-cyclodextrin-free medium and resulted in the appearance of mutant protein at the apical membrane and in intracellular vesicles. Under these conditions, cells might be able to partially restore membrane cholesterol levels through cholesterol biosynthesis during the chase time. The presence of methyl-β-cyclodextrin during the chase caused a complete block of ΔF508 internalization but was accompanied by toxicity and morphological alterations of epithelial airway cultures (data not shown).

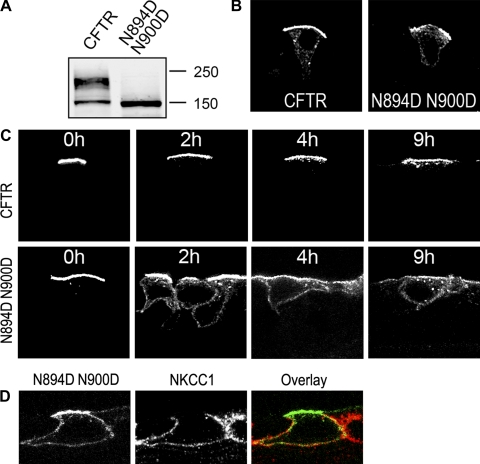

N-glycans are required for efficient apical recycling of CFTR.

CFTR has two N-linked oligosaccharide chains attached to EL4 but is transported to the apical membrane independently of its glycans (5) (Fig. 7B). CFTR with asparagine residues N894 and N900 replaced with aspartate remains unglycosylated (Fig. 7A). When we labeled this unglycosylated CFTR protein at the apical membrane of primary HAE cultures and followed the protein over time, we found that it was much more rapidly internalized than wild-type CFTR (Fig. 7C). Strikingly, after internalization, the unglycosylated CFTR was transferred to basolateral membrane compartments, where it colocalized with NKCC1 (Fig. 7D). Thus N-glycosyl chains seem to support proper recycling of CFTR to the apical membrane and contribute to the preservation of apical CFTR. Unglycosylated CFTR that was transferred to the basolateral membranes appears to have a short half-life, inasmuch as it did not accumulate at this location over time (Fig. 7C) and was also not found in abundant quantities at this compartment at steady state (Fig. 7B).

Fig. 7.

Nonglycosylated CFTR is less stable than wild-type CFTR and transfers to basolateral membrane compartments after internalization. A: Western blot of lysates of HAE cells adenovirally expressing CFTR N894D N900D, in which asparagine residues N894 and N900 are replaced with aspartate, confirmed lack of glycosylation. B: primary HAE cultures were adenovirally transduced to express wild-type CFTR and a nonglycosylated variant (N894D N900D) of CFTR. All intracellular CFTR pools were detected on frozen culture sections using MAb HA.11, which recognizes the HA tag, followed by Alexa 488-goat anti-mouse IgG conjugate. C: apical pools of CFTR were labeled with anti-HA MAb, and HAE cultures were reincubated for indicated times. Apical and internalized pools of CFTR were detected on frozen culture sections (HAE) with Alexa 488-goat anti-mouse IgG conjugate. Time course experiments were performed on 3 different HAE cultures; 1 representative example is shown. D: immunofluorescence labeling of sodium-potassium-chloride cotransporter isoform 1 (NKCC1) confirms that internalized CFTR N894D N900D is transported to basolateral compartments. HAE cultures were adenovirally transduced to express CFTR N894D N900D. Apical pools of this CFTR variant were labeled with anti-HA MAb, cultures were reincubated for 4 h, and apical and internalized pools of CFTR were detected with goat anti-mouse-Alexa 488 IgG conjugate. NKCC1 was stained with rabbit anti-NKCC1 antibody and anti-rabbit IgG-Alexa 555 conjugate. Confocal immunofluorescence was performed on ≥3 different cultures derived from different subjects; 1 representative example is shown.

DISCUSSION

To conduct our studies in a physiologically relevant system, we examined endocytic routing and apical stability of wild-type and ΔF508 CFTR in highly differentiated primary HAE cells. Interestingly, CFTR internalization was slower in ciliated, highly polarized HAE cultures than in nonpolarized HAE cells (Fig. 2). The epithelial cell line CFBE41o− has commonly been used as a model system for CFTR trafficking. We applied cell surface biotinylation-based endocytosis studies to compare internalization of CFTR in primary differentiated HAE cultures and polarized CFBE41o− cells (see supplemental Fig. S1). These results demonstrated significantly slower internalization of CFTR in HAE than CFBE41o− cells. The majority of our trafficking studies of CFTR in primary HAE cells were conducted using confocal immunofluorescence microscopy. However, a small, but significant, amount of CFTR internalized in primary HAE cells was revealed at earlier times in our cell surface biotinylation assays than in our confocal immunofluorescence studies. This may be due to confocal microscopy not allowing for the detection of very small amounts of internalized CFTR. Therefore, to complement our confocal immunofluorescence microscopy studies that visualized redistribution of apically labeled CFTR over time, we quantified the amounts of CFTR remaining at the apical surface over time by On-Cell Western assays. Both techniques clearly demonstrated a drastic decrease in the apical stability of temperature-rescued ΔF508 CFTR compared with the wild-type protein in primary HAE cultures (Fig. 4). The accelerated appearance of mutant CFTR in endocytic vesicles is consistent with the increase in apical turnover of ΔF508 CFTR shown in other studies (40, 42). When recycling from endocytic vesicles back to the apical membrane was visualized, most of the internalized wild-type CFTR returned to the apical membrane, whereas ΔF508 recycled only with extremely low efficiency and resided mainly in intracellular and subapical vesicles. This is consistent with observations of Sharma et al. (39), obtained using nonpolarized cells, which suggested that internalized ΔF508 CFTR is inefficiently recycled (39).

Recently, small-molecule corrector compounds that result in surface expression of a portion of ΔF508 CFTR have been identified (30, 35, 41). Corrector compounds facilitate ER exit and cell surface expression of the mutant protein, whereas potentiator compounds increase the channel activity of ΔF508 CFTR channels that are already present at the cell membrane. Most corrector compounds cause only a modest increase in the maturation of CFTR-processing mutants, such that the yield of mature protein is usually ≤10% of that of wild-type CFTR. We found that simultaneous application of VRT-325 and Corr-4a increased the apical expression of ΔF508 CFTR relative to the amount of apical expression as a result of application of each corrector individually. This is in accordance with studies on nonpolarized cells, where the combination of different corrector compounds, i.e., VRT-325 together with Corr-2b or Corr-4a, appears to have an additive effect on ΔF508 rescue (45). The mechanism by which these correctors rescue ΔF508 CFTR from ER retention is not completely clear. Corrector compounds may promote ΔF508 CFTR folding or protect misfolded CFTR from ER-associated degradation by allowing it to bypass quality-control systems. Recent studies suggest that certain corrector compounds, e.g., VRT-325 and Corr-4a, might bind to mutant CFTR directly during its processing (46) and may facilitate domain folding and assembly at the ER (14, 23, 25, 47). The ΔF508 deletion results in a thermally unstable protein (16, 38), and the functional and biochemical half-lives of the rescued mutant protein are greatly shortened. Therefore, ideal corrector compounds need to stabilize the protein at the cell surface as well as restore folding and function. It is important to note that proper folding and subsequent stability of CFTR mutants are not always strictly coupled (10). Van Goor et al. (41) indicated that VRT-325 may increase the residence time of ΔF508 CFTR at the apical surface of CF HAE cells compared with the low-temperature-rescued mutant protein. In our studies, the two corrector compounds, VRT-325 and Corr-4a, did cause apical expression of ΔF508 CFTR in primary HAE cultures but did not restore normal stability of the mutant protein at the cell surface (Fig. 6). Apical ΔF508 that had been rescued by VRT-325 and Corr-4a was internalized and transferred to endocytic compartments as rapidly as the low-temperature-rescued protein. Although endocytic turnover of temperature-rescued ΔF508 CFTR has been characterized to some extent (12, 39), much less information is available on the endocytic fate of ΔF508 CFTR rescued by small-molecule correctors. Varga et al. (42) recently showed that the half-life of temperature-rescued ΔF508 CFTR is slightly increased in the presence of correctors, VRT-325 and Corr-4a, but remained significantly shorter than in wild-type cells. However, in those studies, ΔF508 CFTR protein was rescued by low-temperature incubation, rather than by correctors, and was subsequently exposed to corrector compounds. Although the internalization rate of temperature-rescued ΔF508 CFTR was significantly reduced (6-fold) in the presence of correctors, the surface half-life was only slightly increased (2-fold). A possible explanation for this observation is that the recycling of the mutant protein remained impaired, even in the presence of the applied correctors. Future studies will elucidate whether corrector compounds other than VRT-325 and Corr-4a may restore the apical stability of ΔF508 CFTR to wild-type levels. If this is not observed using individual compounds, simultaneous application of different compounds may be required to restore folding and stability at the apical membrane.

To augment the apical stability of ΔF508 CFTR, we explored different means to inhibit the rapid internalization of the mutant protein from the apical membrane. The small molecule, Dynasore, a noncompetitive inhibitor of dynamin GTPase activity, slowed ΔF508 CFTR internalization significantly but did not block it completely (Fig. 6D). Dynamin is essential for clathrin-dependent coated vesicle formation, and, upon its inhibition, dynamin-dependent endocytosis in cells can be blocked by >90% (28). We observed complete inhibition of CFTR endocytosis from the apical membrane of primary human HAE cells by MG-132, an inhibitor of the proteasomal proteases (Fig. 6D). We and others previously observed that the half-life of ΔF508 CFTR at the cell surface of polarized and nonpolarized cell lines is increased by inhibition of proteasomal degradation (12, 21). The detailed mechanism of this process is not clearly established. However, ubiquitinylation of ΔF508 CFTR has been implicated in its targeting to lysosomal degradation (39); therefore, it appears possible that a secondary reduction of free ubiquitin due to inhibition of proteosomal protease activity may be responsible for the blockage in internalization of mutant CFTR. We have also observed that methyl-β-cyclodextrin, which effectively extracts cholesterol from cell membranes, inhibited the rapid internalization of rescued ΔF508 CFTR. Relative to untreated cells, treatment with methyl-β-cyclodextrin led to a partial arrest of internalization when cells were chased in drug-free medium after CD treatment. Addition of methyl-β-cyclodextrin during the chase period caused a total block of ΔF508 internalization (Fig. 6D), which may indicate that the cells are able to partially restore cholesterol levels by cholesterol biosynthesis during the chase if methyl-β-cyclodextrin is absent. It is tempting to speculate that increased intracellular cholesterol pools that have been reported in cells expressing ΔF508 CFTR (13, 22, 50, 51) might contribute to the rapid turnover of the mutant protein. However, in our studies, we did not observe a significant difference in the turnover of virally expressed wild-type or ΔF508 CFTR in CF HAE cultures (ΔF508/ΔF508) or normal HAE cultures. This indicates that although the endocytic stability of CFTR is severely affected by the ΔF508 mutation in the protein, it does not seem to be influenced by the genotype of the culture expressing the protein.

A fundamental property of polarized epithelial cells is the asymmetric distribution of membrane proteins on distinct plasma membrane domains. The sorting of apical and basolateral proteins is regulated by intrinsic sorting signals, such as amino acid sequence motifs and carbohydrate or lipid moieties of the individual proteins (8, 36). Specific sorting machineries have been described in the trans-Golgi network and endosomes, which recognize these signals and direct proteins to specific apical or basolateral transport pathways (17, 36). Although most studies have elucidated polarized sorting of secretory proteins at the trans-Golgi network, less information is available on endosomal sorting in the recycling pathway.

We demonstrated recently in primary HAE cells that secretion of CFTR to the apical membrane is independent of its glycosylation state (5). Intriguingly, unglycosylated CFTR is destabilized at the apical surface and sorted to the basolateral membrane after internalization from the apical membrane. Our observations suggest that N-glycans promote apical recycling. Similarly, it has recently been reported that the N-glycans facilitate the apical recycling of other glycoproteins, such as the sialomucin endolyn (31).

In conclusion, this study characterized the endocytic trafficking of wild-type and rescued ΔF508 CFTR in their native environment. Our results suggest that, in primary HAE cultures, overexpressed apical wild-type and rescued mutant CFTR are differently recognized by a post-ER quality-control system. Although the externally epitope-tagged CFTR proteins that were used in our studies have been shown to behave similarly to the untagged CFTR protein (12), we cannot rule out the possibility that native interactions that may occur at the site of epitope insertion in vivo could be disrupted in the Extope construct. Furthermore, the viral vectors that we have applied in this study might result in undesired functional changes, and overexpression of CFTR might affect its intracellular trafficking. Thus it is essential to extend these studies to examine endocytic turnover of endogenous CFTR in HAE cultures.

Although our studies demonstrate that apical ΔF508 CFTR can be stabilized by blocking dynamin-dependent endocytosis, inhibiting proteasomal degradation, and extracting membrane cholesterol, these approaches may lack potential as therapeutics in CF. It is therefore crucial to elucidate novel strategies to increase the apical stability of ΔF508 CFTR. Pharmacological therapies that promote transfer of mutant CFTR to the apical membrane combined with approaches to increase its stability at this location may substantially augment the surface density of mutant CFTR and, thereby, alleviate symptoms in CF patients.

GRANTS

This work was supported by Cystic Fibrosis Foundation Grants GENTZS07G0, RDP R026-CR07, and R026-CR037, National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases Molecular Therapy Core Center Grant P30 DK-065988, and National Institutes of Health Grants R01 HL-080561, P50 HL-60280, and R01 DK-051870.

DISCLOSURES

No conflicts of interest are declared by the author(s).

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We are grateful to the members of the Cystic Fibrosis Center Tissue Culture Core for providing primary HAE cells, Tim Donovan for maintaining cultures, Kim Burns for histological services, Rodney Gilmore and Bonnie Olsen (Molecular Biology Core) for constructing adenoviral vectors, Michael Chua and Neal Kramarcy for assisting with confocal microscopy, Xiu-bao Chang for designing and assembling the Extope-CFTR cloning strategy, and Andrei Aleksandrov and Tim Jensen for assisting with statistical analysis. We thank Bob Bridges and Cystic Fibrosis Foundation Therapeutics for providing the corrector compounds VRT-325 and Corr-4a, Henry E. Pelish for synthesizing and the Kirchhausen laboratory for distributing Dynasore, J. P. Clancy for providing CFBE41o− cells expressing CFTR, and Christian Lytle for providing anti-NKCC antibody.

REFERENCES

- 1.Amaral MD. CFTR and chaperones: processing and degradation. J Mol Neurosci 23: 41–48, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ameen N, Silvis M, Bradbury NA. Endocytic trafficking of CFTR in health and disease. J Cyst Fibros 6: 1–14, 2007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Boucher RC. Airway surface dehydration in cystic fibrosis: pathogenesis and therapy. Annu Rev Med 58: 157–170, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chang XB, Hou YX, Jensen T, Riordan JR. Mapping of the cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator membrane topology by glycosylation site insertion. J Biol Chem 269: 18572–18575, 1994 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chang XB, Mengos A, Hou YX, Cui L, Jensen TJ, Aleksandrov A, Riordan JR, Gentzsch M. Role of N-linked oligosaccharides in the biosynthetic processing of the cystic fibrosis membrane conductance regulator. J Cell Sci 121: 2814–2823, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Coyne CB, Kelly MM, Boucher RC, Johnson LG. Enhanced epithelial gene transfer by modulation of tight junctions with sodium caprate. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol 23: 602–609, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Davis PB. Cystic fibrosis since 1938. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 173: 475–482, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Delacour D, Jacob R. Apical protein transport. Cell Mol Life Sci 63: 2491–2505, 2006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Denning GM, Anderson MP, Amara JF, Marshall J, Smith AE, Welsh MJ. Processing of mutant cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator is temperature-sensitive. Nature 358: 761–764, 1992 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Du K, Sharma M, Lukacs GL. The ΔF508 cystic fibrosis mutation impairs domain-domain interactions and arrests post-translational folding of CFTR. Nat Struct Mol Biol 12: 17–25, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fulcher ML, Gabriel S, Burns KA, Yankaskas JR, Randell SH. Well-differentiated human airway epithelial cell cultures. Methods Mol Med 107: 183–206, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gentzsch M, Chang XB, Cui L, Wu Y, Ozols VV, Choudhury A, Pagano RE, Riordan JR. Endocytic trafficking routes of wild type and ΔF508 cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator. Mol Biol Cell 15: 2684–2696, 2004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gentzsch M, Choudhury A, Chang XB, Pagano RE, Riordan JR. Misassembled mutant ΔF508 CFTR in the distal secretory pathway alters cellular lipid trafficking. J Cell Sci 120: 447–455, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Grove DE, Rosser MF, Ren HY, Naren AP, Cyr DM. Mechanisms for rescue of correctable folding defects in CFTR DeltaF508. Mol Biol Cell 20: 4059–4069, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Guggino WB, Stanton BA. New insights into cystic fibrosis: molecular switches that regulate CFTR. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 7: 426–436, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hegedus T, Aleksandrov A, Cui L, Gentzsch M, Chang XB, Riordan JR. F508del CFTR with two altered RXR motifs escapes from ER quality control but its channel activity is thermally sensitive. Biochim Biophys Acta 1758: 565–572, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ikonen E, Simons K. Protein and lipid sorting from the trans-Golgi network to the plasma membrane in polarized cells. Semin Cell Dev Biol 9: 503–509, 1998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Knowles MR, Boucher RC. Mucus clearance as a primary innate defense mechanism for mammalian airways. J Clin Invest 109: 571–577, 2002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kopito RR. Biosynthesis and degradation of CFTR. Physiol Rev 79: S167–S173, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kreda SM, Mall M, Mengos A, Rochelle L, Yankaskas J, Riordan JR, Boucher RC. Characterization of wild-type and ΔF508 cystic fibrosis transmembrane regulator in human respiratory epithelia. Mol Biol Cell 16: 2154–2167, 2005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kwon SH, Pollard H, Guggino WB. Knockdown of NHERF1 enhances degradation of temperature rescued ΔF508 CFTR from the cell surface of human airway cells. Cell Physiol Biochem 20: 763–772, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lim CH, Bijvelds MJ, Nigg A, Schoonderwoerd K, Houtsmuller AB, de Jonge HR, Tilly BC. Cholesterol depletion and genistein as tools to promote F508delCFTR retention at the plasma membrane. Cell Physiol Biochem 20: 473–482, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Loo TW, Bartlett MC, Clarke DM. Correctors promote folding of the CFTR in the endoplasmic reticulum. Biochem J 413: 29–36, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Loo TW, Bartlett MC, Clarke DM. Rescue of ΔF508 and other misprocessed CFTR mutants by a novel quinazoline compound. Mol Pharm 2: 407–413, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Loo TW, Bartlett MC, Wang Y, Clarke DM. The chemical chaperone CFcor-325 repairs folding defects in the transmembrane domains of CFTR-processing mutants. Biochem J 395: 537–542, 2006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lukacs GL, Chang XB, Bear C, Kartner N, Mohamed A, Riordan JR, Grinstein S. The ΔF508 mutation decreases the stability of cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator in the plasma membrane. Determination of functional half-lives on transfected cells. J Biol Chem 268: 21592–21598, 1993 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lukacs GL, Segal G, Kartner N, Grinstein S, Zhang F. Constitutive internalization of cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator occurs via clathrin-dependent endocytosis and is regulated by protein phosphorylation. Biochem J 328: 353–361, 1997 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Macia E, Ehrlich M, Massol R, Boucrot E, Brunner C, Kirchhausen T. Dynasore, a cell-permeable inhibitor of dynamin. Dev Cell 10: 839–850, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Okiyoneda T, Lukacs GL. Cell surface dynamics of CFTR: the ins and outs. Biochim Biophys Acta 1773: 476–479, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Pedemonte N, Lukacs GL, Du K, Caci E, Zegarra-Moran O, Galietta LJ, Verkman AS. Small-molecule correctors of defective ΔF508-CFTR cellular processing identified by high-throughput screening. J Clin Invest 115: 2564–2571, 2005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Potter BA, Weixel KM, Bruns JR, Ihrke G, Weisz OA. N-glycans mediate apical recycling of the sialomucin endolyn in polarized MDCK cells. Traffic 7: 146–154, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Prince LS, Workman RB, Jr, Marchase RB. Rapid endocytosis of the cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator chloride channel. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 91: 5192–5196, 1994 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Riordan JR. Cystic fibrosis as a disease of misprocessing of the cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator glycoprotein. Am J Hum Genet 64: 1499–1504, 1999 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Riordan JR, Rommens JM, Kerem B, Alon N, Rozmahel R, Grzelczak Z, Zielenski J, Lok S, Plavsic N, Chou JL, et al. Identification of the cystic fibrosis gene: cloning and characterization of complementary DNA. Science 245: 1066–1073, 1989 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Robert R, Carlile GW, Pavel C, Liu N, Anjos SM, Liao J, Luo Y, Zhang D, Thomas DY, Hanrahan JW. Structural analog of sildenafil identified as a novel corrector of the F508del-CFTR trafficking defect. Mol Pharmacol 73: 478–489, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Rodriguez-Boulan E, Kreitzer G, Musch A. Organization of vesicular trafficking in epithelia. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 6: 233–247, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Rommens JM, Iannuzzi MC, Kerem BS, Drumm ML, Melmer G, Dean M, Rozmahel R, Cole JL, Kennedy D, Hidaka N, Zsiga M, Buchwald M, Riordan JR, Tsui LC, Collins F. Identification of the cystic fibrosis gene: chromosome walking and jumping. Science 245: 1059–1065, 1989 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sharma M, Benharouga M, Hu W, Lukacs GL. Conformational and temperature-sensitive stability defects of the ΔF508 cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator in post-endoplasmic reticulum compartments. J Biol Chem 276: 8942–8950, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Sharma M, Pampinella F, Nemes C, Benharouga M, So J, Du K, Bache KG, Papsin B, Zerangue N, Stenmark H, Lukacs GL. Misfolding diverts CFTR from recycling to degradation: quality control at early endosomes. J Cell Biol 164: 923–933, 2004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Swiatecka-Urban A, Brown A, Moreau-Marquis S, Renuka J, Coutermarsh B, Barnaby R, Karlson KH, Flotte TR, Fukuda M, Langford GM, Stanton BA. The short apical membrane half-life of rescued ΔF508-cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator (CFTR) results from accelerated endocytosis of ΔF508-CFTR in polarized human airway epithelial cells. J Biol Chem 280: 36762–36772, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Van Goor F, Straley KS, Cao D, Gonzalez J, Hadida S, Hazlewood A, Joubran J, Knapp T, Makings LR, Miller M, Neuberger T, Olson E, Panchenko V, Rader J, Singh A, Stack JH, Tung R, Grootenhuis PD, Negulescu P. Rescue of ΔF508-CFTR trafficking and gating in human cystic fibrosis airway primary cultures by small molecules. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 290: L1117–L1130, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Varga K, Goldstein RF, Jurkuvenaite A, Chen L, Matalon S, Sorscher EJ, Bebok Z, Collawn JF. Enhanced cell-surface stability of rescued ΔF508 cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator (CFTR) by pharmacological chaperones. Biochem J 410: 555–564, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Varga K, Jurkuvenaite A, Wakefield J, Hong JS, Guimbellot JS, Venglarik CJ, Niraj A, Mazur M, Sorscher EJ, Collawn JF, Bebok Z. Efficient intracellular processing of the endogenous cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator in epithelial cell lines. J Biol Chem 279: 22578–22584, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Wang X, Venable J, LaPointe P, Hutt DM, Koulov AV, Coppinger J, Gurkan C, Kellner W, Matteson J, Plutner H, Riordan JR, Kelly JW, Yates JR, 3rd, Balch WE. Hsp90 cochaperone Aha1 downregulation rescues misfolding of CFTR in cystic fibrosis. Cell 127: 803–815, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Wang Y, Loo TW, Bartlett MC, Clarke DM. Additive effect of multiple pharmacological chaperones on maturation of CFTR processing mutants. Biochem J 406: 257–263, 2007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Wang Y, Loo TW, Bartlett MC, Clarke DM. Correctors promote maturation of cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator (CFTR)-processing mutants by binding to the protein. J Biol Chem 282: 33247–33251, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Wang Y, Loo TW, Bartlett MC, Clarke DM. Modulating the folding of P-glycoprotein and cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator truncation mutants with pharmacological chaperones. Mol Pharmacol 71: 751–758, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Welsh MJ, Fick RB. Cystic fibrosis. J Clin Invest 80: 1523–1526, 1987 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Welsh MJ, Smith AE. Molecular mechanisms of CFTR chloride channel dysfunction in cystic fibrosis. Cell 73: 1251–1254, 1993 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.White NM, Corey DA, Kelley TJ. Mechanistic similarities between cultured cell models of cystic fibrosis and Niemann-Pick type C. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol 31: 538–543, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.White NM, Jiang D, Burgess JD, Bederman IR, Previs SF, Kelley TJ. Altered cholesterol homeostasis in cultured and in vivo models of cystic fibrosis. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 292: L476–L486, 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.