Abstract

Pompe disease is a muscular dystrophy that results in respiratory insufficiency. We characterized the outcomes of targeted delivery of recombinant adeno-associated virus serotype 1 (rAAV2/1) vector to diaphragms of Pompe mice with varying stages of disease progression. We observed significant improvement in diaphragm contractile strength in mice treated at 3 months of age that is sustained at least for 1 year and enhanced contractile strength in mice treated at 9 and 21 months of age, measured 3 months post-treatment. Ventilatory parameters including tidal volume/inspiratory time ratio, minute ventilation/expired CO2 ratio, and peak inspiratory airflow were significantly improved in mice treated at 3 months and tested at 6 months. Despite early improvement, mice treated at 3 months and tested at 1 year had diminished normoxic ventilation, potentially due to attenuation of correction over time or progressive degeneration of nontargeted accessory tissues. However, for all rAAV2/1-treated mice (treated at 3, 9, and 21 months, assayed 3 months later; treated at 3 months, assayed at 1 year), minute ventilation and peak inspiratory flows were significantly improved during respiratory challenge. These results demonstrate that gel-mediated delivery of rAAV2/1 vectors can significantly augment ventilatory function at initial and late phases of disease in a model of muscular dystrophy.

Introduction

In many forms of muscular dystrophy, the progressive weakening and wasting of skeletal muscles, and in particular the respiratory muscles, leads to ventilatory insufficiency, which oftentimes results in the need for mechanical ventilation. Pompe disease (glycogen storage disease type II; acid maltase deficiency; MIM 232300) is one form of inherited muscular dystrophy and is caused by a lack of functional lysosomal acid α-glucosidase (GAA). GAA is responsible for the breakdown of lysosomal glycogen to monosaccharides. A deficiency of GAA results in the severe storage of glycogen in lysosomal compartments of striated muscle, ultimately leading to the disruption of contractile capabilities of the cell.1 There exists a continuum of Pompe disease that correlates with the levels of GAA enzyme activity and onset of clinical disease. In the infantile form, there is little to no residual GAA activity and those affected usually do not survive beyond 2 years of age as a result of cardiorespiratory failure. The juvenile and adult-onset forms of Pompe disease result from a partial deficiency of GAA and the primary consequence is ultimately respiratory failure.2,3,4,5,6

Recently, a recombinant GAA has been approved for use in an enzyme replacement therapy strategy for the treatment of Pompe disease. A biweekly infusion of the recombinant enzyme has been shown to improve survival in subjects with the infantile form of disease; however, many patients receiving enzyme replacement therapy eventually require assisted ventilation.7,8 Gene therapy provides an attractive alternative to the current mode of therapy, as it could provide continuous endogenous expression of the therapeutic protein directly within the affected tissues. We, and others, have shown the potential of recombinant adeno-associated virus (rAAV) vectors for the treatment of Pompe disease.9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17

AAVs are nonpathogenic parvoviruses that are being widely developed as potential human gene therapy vectors. To date, over 20 different clinical trials have been initiated using rAAV vectors. Although AAV2 was used as the basis for the first AAV-based gene therapy vector, >100 different isolates of AAV have since been identified, many of which have already been developed as pseudotyped gene therapy vectors in which the rAAV2-based vector genome is encapsidated in a different serotype capsid.18,19,20,21,22 Each serotype may confer differential cell type tropisms, which could be exploited for more targeted gene therapy applications. In these studies, we use an AAV1-based vector (rAAV2/1) (refs. 13,23,24).

Previously, we had developed a gel-based method of delivery for efficient and uniform transduction of the diaphragm muscle. Using the gel-mediated method of delivery of a therapeutic rAAV2/1 vector encoding for cytomegalovirus immediate-early promoter-driven human GAA (CMV-hGAA), we were able to achieve physiologic levels of GAA activity with concomitant clearance of glycogen in diaphragms of a mouse model of Pompe disease (Gaa−/−).11 In this study, we further evaluate the physiological consequences of the biochemical correction resulting from gel-mediated delivery of rAAV2/1-CMV-hGAA to diaphragms of adult Pompe mice, as it relates to ventilation during both eupneic conditions and respiratory challenge.

Results

Gel-mediated delivery of rAAV2/1 can result in efficient transduction of diaphragm and clearance of accumulated glycogen

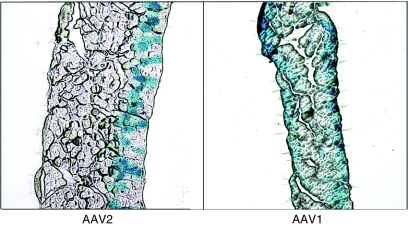

Substantial correction of the diaphragm in Pompe mice using rAAV has been challenging in the past using strategies such as systemic delivery or delivery to a peripheral muscle, a strategy that depends upon successful cross-correction of the diaphragm from secreted enzyme. In initial studies, adult Gaa−/− mice (n = 3) were administered 1 × 1012 vector genomes (vg) of rAAV2/1-CMV-hGAA via intravenous injection in the jugular vein. Ten weeks post-treatment, the treated mice had an average of only 9.6 ± 3.2% wild-type levels of diaphragm GAA activity (data not shown). In another study, adult Gaa−/− mice (n = 10) were injected with 7.5 × 1011 vg rAAV2/1-CMV-hGAA directly into the quadriceps femoris. Although the injected muscle had an average of 66 ± 42% of wild-type GAA enzyme activity, none of the treated animals showed any detectable GAA enzyme activity in the diaphragm (data not shown). These observations led to a novel strategy where direct gel-mediated delivery of rAAV to murine diaphragm lead to efficient transduction.11 As shown in Figure 1, further histological analysis of transduced diaphragms from mice administered 1 × 1011 vg rAAV encoding CMV promoter-driven β-galactosidase (lacZ) showed that not only could administration of rAAV2/1 lead to uniform transduction across the surface of the diaphragm on which the vector was applied, but that rAAV2/1 vector could transduce the entire thickness of the diaphragm tissue. In comparison, rAAV2 vectors could only transduce the first few layers of cells.

Figure 1.

AAV2/1 can transverse the entire diaphragm thickness. Recombinant AAV2/1 (AAV1) and AAV2 vectors encoding for cytomegalovirus promoter-driven lacZ were applied to the peritoneal side (right side in this figure) of the diaphragm of normal mice using the gel method of delivery. Six weeks postinfection, tissues were harvested and stained for lacZ expression by X-gal staining as described in Methods. AAV1 transgene is observed on both thoracic and peritoneal surfaces. AAV, adeno-associated virus.

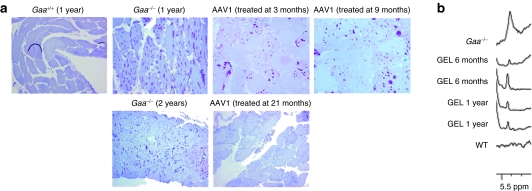

We next administered 1 × 1011 vg rAAV2/1-CMV-hGAA to diaphragms of adult 3-, 9-, and 21-month-old Gaa−/− mice using the gel delivery method. GAA enzyme activity was assessed 3 months post-treatment for each age group and in an additional cohort of mice treated at 3 months of age, diaphragmatic GAA activity was assessed at 9 months post-treatment. Similar to previous work, we saw an average of 85 ± 38.5% normal GAA activity in gel-treated diaphragms.11 No significant difference in GAA enzyme activity levels was seen with respect to age at treatment, or with time post-treatment as in the case of mice treated at 3 months of age and analyzed at 6 month (3 months post-treatment) and 1 year of age (9 months post-treatment), respectively. Diaphragmatic GAA activity was attributed to direct transduction of the diaphragm rather than uptake of secreted enzyme from other tissues as both liver and heart GAA activities from the treated animals were not significantly different (P > 0.05) than levels seen in untreated control tissues (Supplementary Figure S1). Furthermore real-time PCR showed an average of 6,228 ± 3,861 vg copies per µg DNA in diaphragms of treated animals whereas in liver and heart, vector genome copies were significantly lower (393 ± 387 copies and 73 ± 35 copies per µg DNA, respectively). In concordance with the GAA enzyme activity data, real-time reverse transcriptase-PCR analysis for transgene-specific transcripts showed undetectable levels of RNA in livers of treated animals whereas diaphragms had an average of >3.8 × 106 transcripts per µg RNA (Supplementary Figure S2). As shown in Figure 2a, periodic acid-Schiff staining of diaphragm tissue also revealed a reduction in the amount of stored glycogen in the tissue for all treated age groups. Proton magnetic resonance spectroscopy (1H-MRS) of perchloric extracts of isolated diaphragm tissues in mice treated at 3 months and assayed at 6 or 12 months of age further support these findings (Figure 2b; representative spectra) with 66 ± 16% (n = 4) and 58 ± 11% (n = 4) less glycogen content than untreated Gaa−/− mice.

Figure 2.

Gel-mediated delivery of AAV1-CMV-hGAA to diaphragms of Gaa−/− mice leads to clearance of accumulated glycogen. (a) Periodic acid-Schiff staining of diaphragms from a 1-year-old wild-type (Gaa+/+), 1- and 2-year-old Gaa−/−, 1-year-old Gaa−/− mice treated with AAV2/1 either at 3 or 9 months of age, and 2-year-old Gaa−/− mouse treated at 21 months of age. Purple staining is indicative of glycogen. (b) Perchloric acid extracts of diaphragm from untreated Gaa−/−, Gaa−/− mice treated at 3 months of age and assayed at 6 months (GEL 6 months) or 1 year of age (GEL 1 year), or C57BL6/129SvJ (WT) were analyzed by 1H-MRS for the presence of glycogen. AAV, adeno-associated virus; CMV, cytomegalovirus; WT, wild type.

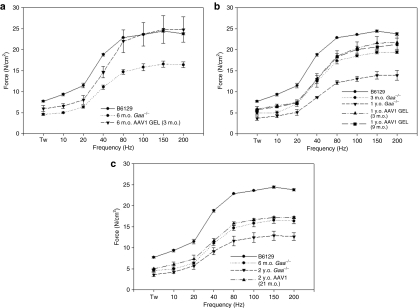

Diaphragm contractility is significantly improved after administration of rAAV2/1 vectors

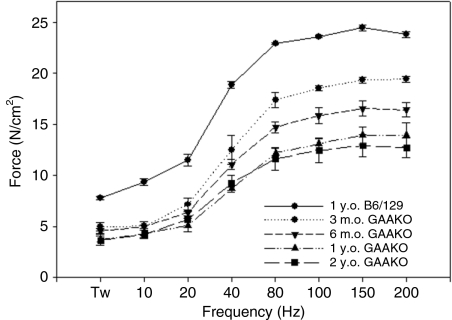

Similar to the Pompe patient population, Gaa−/− mice have a progressive weakening of diaphragm contractile strength correlating with duration of disease. As shown in Figure 3, isometric force–frequency relationships from diaphragm muscle isolated from untreated Gaa−/− mice (n = 3 for each group) show a significant decrease in contractile strength with age from 3 months to 2 years of age. After gel-mediated administration of rAAV2/1-CMV-hGAA to diaphragms of Gaa−/− mice, we see a significant improvement in the contractile strength in the diaphragm muscle as compared to age-matched untreated controls. For animals that were treated at 3 months of age, diaphragm contractile strength approached wild-type levels (peak force 24.43 ± 0.29 in 1-year-old mice) at 6 months (peak force of 24.83 ± 3.31 N/cm2) (Figure 4a) and was sustained out to 1 year (21.59 ± 1.59 N/cm2) of age (Figure 4b, closed triangles), as compared to age-matched untreated controls (peak force of 16.53 ± 0.74 and 13.94 ± 1.15 N/cm2 at 6 months and 1 year, respectively). In mice treated at 9 months (peak force of 21.28 ± 1.49 N/cm2, 3 months post-treatment) (Figure 4b, closed squares) and 21 months (peak force of 17.21 ± 0.29 N/cm2, 3 months post-treatment) (Figure 4c) of age, we still saw a significant improvement in contractile function of treated diaphragms, as compared to age-matched untreated controls (peak force of 12.71 ± 0.94 N/cm2 at 2 years of age).

Figure 3.

The mouse model of Pompe disease exhibits decreasing diaphragm contractile strength with age. Diaphragm was isolated from 3, 6, 12, and 24 month-old Gaa−/− mice and contractile strength was assessed by determining force–frequency relationships (n = 3 for each group). GAAKO, Gaa−/−. m.o., month(s) old; y.o., year(s) old.

Figure 4.

Correction of diaphragmatic contractile strength after gel-mediated delivery of AAV1-CMV-hGAA to diaphragm. (a) Three-month-old Gaa−/− mice were administered AAV1 vector and contractile strength was determined 3 months post-treatment (n = 3 for each group). (b) Three- or 9-month-old Gaa−/− mice were administered AAV2/1 vector and contractile strength was determined at 1 year of age (n = 3 for each group). (c) 21-month-old Gaa−/− mice were administered AAV1 vector and contractile strength was determined at 2 years of age (n = 3 for each group). AAV, adeno-associated virus; CMV, cytomegalovirus, m.o., month(s) old; y.o., year(s) old.

Ventilatory function is improved after administration of rAAV2/1 vectors to adult Pompe mice

Recently, we have characterized the ventilatory function in Gaa−/− mice and similar to the patient population, the mice also exhibit significantly attenuated ventilation.13,25 Using plethysmography, we are able to simultaneously measure multiple characteristics of ventilation in conscious, unrestrained mice. In this study, ventilation was measured under conditions of normoxia (FIO2: 0.21, FICO2: 0.00) and also during a hypercapnic respiratory challenge (FIO2: 0.93, FICO2: 0.07). The latter was used to assess the extended range of ventilatory capacity.

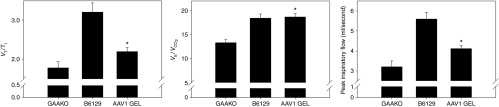

As shown in Figure 5, under normoxic baseline conditions, the mean inspiratory airflow rate (the ratio of tidal volume/inspiratory time (VT/TI; ml/second) (2.2 ± 0.1 versus 1.8 ± 0.2), the ratio of minute ventilation to expired CO2 (VE/VCO2) (18.7 ± 0.7 versus 13.3 ± 0.7), and peak inspiratory flow (ml/second) (4.1 ± 0.2 versus 3.2 ± 0.3) were all improved (P ≤ 0.05) in mice treated at 3 months of age and tested at 6 months as compared to untreated and age-matched control Gaa−/− mice. Normalization of ventilatory function in normoxic conditions was not sustained though, as none of the parameters were significantly different than control mice at 1 year of age (9 months post-treatment) (data not shown). Animals that were treated at 9 months and 21 months of age also did not show improved normoxic ventilation at 3 months post-treatment (data not shown). The cause for reduction in normoxic ventilation at 12 versus 6 months of age in animals that were treated at 3 months of age is not known. Although serial testing of diaphragm GAA activity in individual animals is not feasible, there was no significant difference (P > 0.1) in average diaphragm GAA activity between the two cohorts, suggesting that relative GAA activity was likely stable and did not drop at later time points. Terminal anti-hGAA antibodies were detectable in both cohorts; however, there were no significant differences in serum antibody levels. Animals treated at 3 months and assayed at 6 months of age had 14.7 ± 2-fold over background levels of serum antibodies and animals assayed at 1 year had 15.8 ± 0.9-fold over background levels. In addition, there was no evidence of infiltration in diaphragm tissue as determined by blinded independent review of hematoxylin and eosin stained tissues by the pathologist. Curiously, serum anti-hGAA levels in animals treated at 9 months and assayed at 1 year was 9.9 ± 6.7-fold over background and for animals treated at 21 months of age and assayed at 2 years was 3.8 ± 5.7-fold over background levels, and although not significant, the trend was that the older the animal was at the time of treatment, the lower the average antibody titer.

Figure 5.

Baseline respiration is significantly improved in AAV1-treated mice. Three-month-old Gaa−/− mice were treated with AAV1-CMV-hGAA via the gel method of delivery to diaphragm. Three months postinfection, respiratory function was assayed by awake, unrestrained, whole-body barometric plethysmography (n = 9). Age-matched untreated Gaa−/− (GAAKO) and wild-type C57BL6/129SvJ (B6129) mice were assayed as well, (n = 10 for each group). Baseline function was measured for 1 hour under normoxic conditions. VE/VCO2 represents ventilatory efficiency (the ratio of minute ventilation to expired CO2); VT/TI represents the mean inspiratory flow (ratio of tidal volume to inspiratory time).

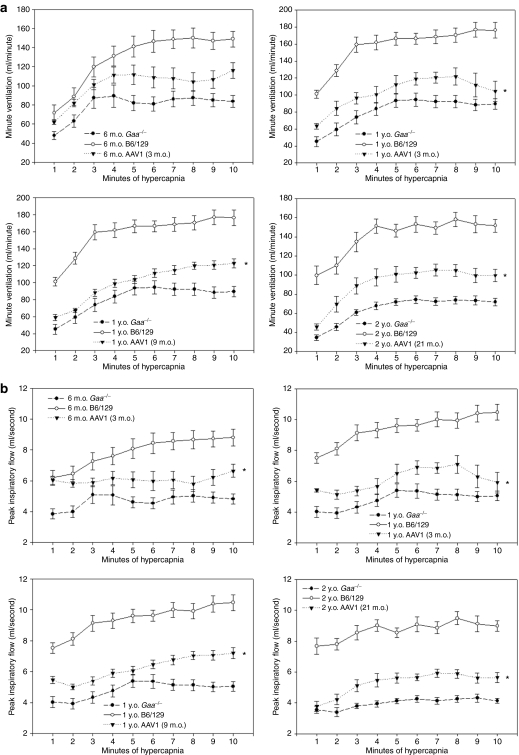

In contrast to the normoxic data, rAAV2/1-CMV-hGAA treatment resulted in a sustained improvement of breathing when assessed during a hypercapnic respiratory challenge. As shown in Figure 6, mice treated at 3 months and assayed at both 6 months and 1 year of age had hypercapnic minute ventilation (Figure 6a) and peak inspiratory flow (Figure 6b) values that were significantly increased over age-matched untreated control animals. Similar results were obtained in Gaa−/− mice treated at 9 or 21 months of age (Figure 6). No significant differences in ventilatory output measures were observed between male and female mice.

Figure 6.

Ventilatory function is significantly improved in rAAV2/1-treated mice. Ventilatory function was assayed by awake, unrestrained, whole-body barometric plethysmography. (a) Graphs show the minute ventilation response to hypercapnia over the 10-minute period of time in untreated Gaa−/− (n = 10), wild-type (n = 10), and rAAV2/1-treated Gaa−/− mice (n = 9 for mice treated at 3 months and assayed at 6 months; n = 4 for mice treated at 3 months and assayed at 1 year; n = 9 for mice treated at 9 months; n = 7 for mice treated at 21 months). (b) Graphs show the peak inspiratory flow response to hypercapnia over the 10-minute period of time in the same animals represented in a. m.o., month(s) old; y.o., year(s) old.

Discussion

Our method selectively targets diaphragm tissue via a physical delivery method. Other studies have also investigated the utility of viral gene therapy vectors to correct diaphragm in mouse models of muscular dystrophy. In contrast to our methods, these prior studies have used direct injection into mouse diaphragm with recombinant adenovirus or plasmid-based vectors.26,27,28 These studies demonstrated only short-term expression in diaphragm, presumably as a result of clearance of transduced tissue by immune response to the vector. Other more recent methods used to transduce mouse diaphragm have employed systemic (intravenous) delivery of vectors in which all skeletal and cardiac muscle in the body are simultaneously exposed to vector.12,29,30 Systemic delivery has the advantage of correcting multiple affected tissues by a simple single injection, however, systemic dissemination of vector has the potential of untoward effects as a result of exposure of vector and transgene expression in nontarget tissues and cells. In addition, depending on the biodistribution properties of each vector system, not all muscle groups are likely to be equally transduced. We have previously shown that systemic delivery of rAAV2/1-CMV-hGAA to Gaa−/− neonates results in ~40% wild-type levels of GAA expression in diaphragm at 1 year postinjection with improvement of in vivo ventilatory function and diaphragm muscle-specific force.13 In the Duchenne mouse model (mdx), Gregorevic et al. showed that systemic delivery of an AAV6 vector co-infused with a cocktail of vascular endothelial growth factor, mouse serum albumin, and heparin to adult mdx mice resulted in ~50% of diaphragm muscle fibers expressing dystrophin, 4 months postinjection, with improved resistance to contraction-induced injury; however, no improvements in specific force occurred.29 In this study, targeted gel-mediated delivery of AAV directly to affected diaphragm tissue in adult animals resulted in ~85% wild-type levels of GAA activity with concurrent improved in vivo ventilatory function and improvement of specific force generation.

Due to the physical nature of the mouse diaphragm (size and thickness), we utilized a gel-based method of vector delivery. Interestingly, we noted that rAAV2/1 vector could spread through the thickness of the diaphragm, whereas rAAV2 vector could only transduce the first few cell layers. The spread of vector may be attributed to the capsid conferring differential infection via cellular receptors and/or trafficking through the tissue via the process of transcytosis.31,32

In this work, we were able to achieve biochemical, histological, and physiologic correction of diaphragm in Pompe mice by direct administration of an rAAV2/1 vector encoding human GAA under control of the CMV promoter to the affected tissue. Other studies have suggested that use of a non-tissue-specific promoter, such as the CMV promoter, may result in adverse immune response to the vector and/or transgene product. Sun et al. investigated the direct injection of rAAV vectors to the gastrocnemius of Pompe mice using AAV2/6 pseudotyped vectors expressing GAA under control of the hybrid CMV enhancer-chicken β actin (CB) promoter. In that work, they showed low levels of GAA expression 6 weeks post-treatment and evidence of both humoral and cellular immune response. Replacement of the CB promoter with a more muscle-specific promoter resulted in increased levels of transgene expression and blunting of the cellular, but not humoral, immune response.15 Prior studies using intramuscular injection of CMV promoter–driven vector constructs in Pompe mice have been limited to adenovirus-based vectors delivered directly into gastrocnemius muscle. In adult animals, significant transduction and gene expression in the injected muscle was noted in short-term studies in adult mice, however, loss of expression or immune response was not investigated.33 Intramuscular delivery to 4-day-old animals resulted in sustained high levels of expression in the injected muscle, however, immaturity of the immune system may have contributed to the long-term expression.34

It is interesting to note that although we did see a humoral immune response as evidenced by the presence of terminal serum anti-GAA antibodies, review of treated diaphragm tissues did not reveal any evidence of infiltrates in diaphragm tissue. Although theoretical, it is possible that the diaphragm may be more immune privileged as compared to other targeted muscles such as the tibialis anterior or gastrocnemius. Studies by Fukuda et al. suggest that there exist differences in the processing of GAA in cardiac, diaphragm, and skeletal muscles.35 It is possible that differential processing of the transgene product and/or vector in these tissues may have contributed to the different outcomes. In addition, subtle differences between the AAV1-based vectors as compared to other AAV serotypes may have contributed to the sustained expression in the absence of inflammation. For example, although AAV1 and 6 differ by only six amino acids in the capsid region, biodistribution studies have shown that although there is overlap of expression patterns, that in vivo biodistribution and transgene expression is distinct between the two serotypes.22 Recently, Xin et al. showed that AAV1 transduced the dendritic cells less efficiently than serotypes 2, 5, 7, and 8 and work by Kelly et al. demonstrated that, depending on vector dose and level of transgene expression, intramuscular delivery of an AAV2/1 vector utilizing the ubiquitous CB promoter could result in immune tolerance.36,37 Numerous other studies in animal models of muscular dystrophy and inborn errors of metabolism have also demonstrated long-term correction using intramuscular delivery of rAAV1 vectors expressing transgenes under the control of CMV or CB promoters.23,24,37,38,39 Recently, Brantly et al., demonstrated long-term expression from intramuscular injection of an rAAV2/1 vector using the CB enhancer/promoter in human subjects in a phase I trial.41 Such differences in biodistribution, trafficking, transgene expression, processing and/or presentation, etc. may have played roles in the success of this diaphragm-targeted approach.

Although we did demonstrate substantial correction of diaphragm muscle strength and ventilatory function after gene therapy treatment, the levels of correction were lower as the age at treatment of the animal increased (3 months versus 9 or 21 months of age) or as the animals got older (treated at 3 months of age and assayed at 6 months versus 1 year of age), suggesting that as the disease progressed, although significant improvement could be achieved, correction was partial as function did not become completely normalized. These results are similar to recent findings by Ziegler et al., in which animals treated with a liver-specific rAAV2/8 vector at a younger age showed higher levels of functional correction than in animals treated at an older age.17 We do not believe that the attenuation in correction in ventilation as the animals got older was due to a lack of long-term correction. Although the presence of an immune response was not formally investigated throughout the course of this study, there was no significant difference in terminal serum anti-GAA antibodies between the two groups and no obvious signs of inflammation noted from histochemical analysis. Furthermore, as we did not see significant differences in enzyme activities from the treated animals assayed at 3 months versus at 9 months post-treatment, these results suggest that transgene expression remained stable long-term. It is quite probable, however, that not every muscle fiber in the diaphragm was corrected. This may be due in part to the potential overall reduction of corrected muscle fibers (especially in the animals treated at a younger age) or muscle fibers amenable for correction (in particular, in the older animals) as the disease progresses and the diaphragm is subjected to repeated use and possible irreversible damage from secondary changes. As such, uncorrected fibers may have undergone some level of progressive disease pathology over time. In addition, other accessory muscles such as intercostals as well as the heart and neural tissues were not targeted by this therapy and therefore were not very efficiently transduced, thus these tissues also likely suffered from disease progression. Therefore, it is likely that the degree of diaphragm correction could not compensate for the progressive dysfunction of the other components involved in respiration, resulting in attenuated ventilatory function over time.

It is also of interest to note that despite the significant difference in diaphragm muscle contractile strength between younger and older rAAV2/1-treated Gaa−/− mice (6, 12, 24 months; Figure 3), minute ventilation under hypercapnic respiratory challenge, as measured using plethysmography (Figure 6), showed no significant difference between the age groups and was significantly reduced as compared to wild-type control animals. Similarly, untreated Gaa−/− mice also showed no difference in minute ventilation between age groups, despite differences in contractile strength and disease progression.25 This finding highlights the fact that ventilation is the result of complex biomechanical and neurological processes and cannot necessarily be predicted by in vitro respiratory muscle assessment alone. Other factors such as neural control, intercostal muscle, and cardiac function, and even the mass of the heart within the chest cavity, also influence ventilation. It is possible that greater levels of correction of ventilatory function may be achieved by targeting other tissues involved in the interplay of ventilation, in addition to diaphragm, and may be achieved via other routes of delivery such as intrapleural administration, which may lead to intercostal muscle correction and the use of vectors capable of efficient neural transduction.

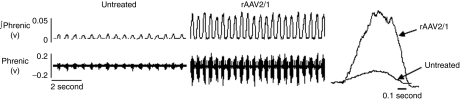

We and others have shown significant glycogen deposits in the central nervous system in both Pompe patients and the mouse model, suggesting the potential for impaired central nervous system function.17,25,42 In addition, we noted an apparent attenuation of efferent phrenic nerve activity in Gaa−/− mice with concomitant attenuation of respiratory function as compared to wild-type animals; however, the precise nature of neural involvement in Pompe disease is not yet clear.25 Anecdotally, we observed that direct administration of rAAV2/1 vector to the diaphragm of a 21-month-old Gaa−/− mouse resulted in much more robust efferent phrenic nerve activity in the treated animal at 2 years of age, as compared to an untreated control (Figure 7). Although such extracellularly recorded compound action potentials must be interpreted cautiously, this preliminary observation suggests that neural deficits in phrenic motor output may be targeted by rAAV-mediated gene therapy.25 Although due to the blood–brain barrier, uptake of secreted enzyme into the phrenic nerve is unlikely, it is possible that retrograde transport of the rAAV vector from the diaphragm to the phrenic axons and/or soma could confer some level of biochemical correction, in turn resulting in increased phrenic motor discharge.43,44 GAA activity and histologic analysis were not assessed in the phrenic nerve, and further studies aimed at understanding the effects of glycogen accumulation in the central nervous system and the possible role in disease pathology are warranted.

Figure 7.

Inspiratory phrenic nerve bursting in an rAAV2/1 treated mouse. Efferent phrenic nerve electrical activity was recorded in anesthetized mice (n = 1, each untreated and rAAV2/1-treated at 21 months and assayed at 2 years of age) using standard neurophysiology methods.25 The left and middle panels show inspiratory phrenic bursting during normoxic conditions in untreated and rAAV2/1 treated mice, respectively. In these panels, the bottom trace is the unprocessed phrenic neurogram, and the top trace is the “integrated” (∫) phrenic signal. The right panel provides an overlay plot comparing a single integrated inspiratory phrenic burst in an untreated versus rAAV2/1 treated mouse. The rAAV2/1 treated mouse had considerably more robust phrenic bursting compared to the untreated mouse. AAV, adeno-associated virus.

In this work, we demonstrate that specific correction of diaphragm can result in overall improvement in ventilatory function in a mouse model of metabolic muscular dystrophy. These studies may be more relevant to the older infantile-onset and juvenile/adult-onset patient populations, as respiratory complications become more predominant concerns in these patient populations.4,45,46 Although significant improvements in the ventilatory phenotype of Pompe mice were achieved, correction was not complete and was affected by the level of disease progression at the time of therapy, again highlighting the importance of early treatment of the disease. However, taken together, these results indicate that physiological correction of diaphragm function can be mediated by rAAV2/1-based gene therapy and that even older animals as old as 21 months of age (note that the average lifespan of a wild-type mouse is ~2 years of age) can benefit from targeted gene therapy.

Materials and Methods

Packaging and purification of rAAV2/1 vectors. The rAAV2 plasmid p43.2-GAA has been described previously.10,12 rAAV vector based on serotype 1 was produced using p43.2-GAA and was generated, purified, and titered at the University of Florida Powell Gene Therapy Center Vector Core Lab as previously described.21

In vivo delivery. All animal studies were performed in accordance with the guidelines of the University of Florida Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee. Three- (n = 13; 2 female, 11 male), 9- (n = 9; 3 female, 6 male), and 21-month-old (n = 7; all female) Gaa−/− (6neo/6neo) mice were administered 1 × 1011 vg rAAV2/1-CMV-hGAA directly to the diaphragm in a gel matrix as described previously.11,47 There were no cases of early mortality and all animals survived until the time of evaluation.

Histological analysis. Segments of untreated and rAAV-lacZ-treated diaphragm were fixed for 15 minutes in 2% paraformaldehyde followed by X-gal staining by standard methods. Stained tissue was then embedded in paraffin and sectioned. Sectioned tissue did not undergo any other processing and was visualized using a Zeiss Axioskop light microscope. For histological glycogen content analysis, untreated and rAAV1-CMV-hGAA-treated diaphragm were fixed overnight in 2% glutaraldehyde in phosphate-buffered saline, embedded in epon, sectioned, and stained with periodic acid-Schiff by standard methods.3,13,47

Vector pharmacology. Real-time DNA PCR was performed by the University of Florida NGVL Toxicology Core as follows. One microgram of extracted genomic DNA was used in all quantitative PCRs; reaction conditions followed those recommended by PerkinElmer/Applied Biosystems (Foster City, CA) and included 50 cycles of 94 °C for 40 second, 37 °C for 2 minutes, 55 °C for 4 minutes, and 68 °C for 30 seconds. Primer pairs were designed to the cytomegalovirus enhancer/promoter and standard curves were established by spike-in concentrations of a plasmid DNA identical to the plasmid used in making the vector. DNA samples were assayed in triplicate. The third replicate was spiked with plasmid DNA at a ratio of 100 copies/µg of genomic DNA. The sample was considered negative if <100 copies/µg were present. When <1 µg of genomic DNA was analyzed to avoid PCR inhibitors co-purifying with DNA in the extracted tissue, the spike-in copy number was reduced proportionally to maintain the 100 copies/µg DNA ratio. An n = 3 for each treatment cohort was analyzed and data were reported as AAV genome copies per µg total genomic DNA ± SD.

Real-time reverse transcriptase-PCR was performed by the University of Florida NGVL Toxicology Core as follows. Total RNA was extracted from frozen tissues by the RNeasy Mini Kit. Briefly, 100 ng of extracted total RNA was used in all quantitative PCRs; reaction conditions followed those recommended by PerkinElmer/Applied Biosystems TaqMan One-Step RT-PCR Master Mix and included one cycle at 48 °C for 10 minutes, then one cycle at 95 °C for 10 minutes, then 40 cycles at 95 °C for 15 seconds and 60 °C for 1 minute. Primer pairs were designed to the GAA messenger RNA and standard curves were established by spike-in concentrations of a plasmid DNA identical to the plasmid used in making the vector. RNA samples were assayed in triplicate when possible. The third replicate was spiked with plasmid RNA at a ratio of 100 copies/µg of genomic DNA. An n = 3 for each treatment cohort was analyzed and data were reported as AAV genome copies per µg total RNA ± SD.

GAA enzyme activity and determination of serum anti-hGAA antibodies were performed as previously described.9,10,12,13 Quantitation of glycogen content was assessed on perchloric acid extracted diaphragm tissue samples using proton magnetic resonance spectroscopy (1H-MRS) on a 500 MHz Bruker DRX Spectrometer at the University of Florida AMRIS Facility, as previously described.13 All spectra were normalized to an external TSP-d4 standard.

Unpaired t-test and unpaired t-test with Welch's correction were used for analysis of the aforementioned assays, with statistical significance considered if P < 0.05.

Assessment of contractile and ventilatory function. Isometric force–frequency relationships were analyzed to assess diaphragm contractile force as described previously (n = 3, for each group).13,14

Ventilatory function was assayed using barometric whole-body plethysmography. Unanesthetized, unrestrained C57BL6/129SvJ (n = 10), Gaa−/− (n = 10), and rAAV2/1-treated Gaa−/− mice are placed in a clear plexiglass chamber (Buxco, Wilmington, NC).13,25,48,49 Chamber airflow, pressure, temperature, and humidity are continuously monitored and parameters such as frequency, minute ventilation, tidal volume, and peak inspiratory flow are measured and analyzed using the method by Drorbaugh and Fenn and recorded using BioSystem XA software (Buxco). Baseline measurements are taken under conditions of normoxia (FIO2: 0.21, FICO2: 0.00) for a period of 1 hour followed by a 10-minute exposure to hypercapnia (FIO2: 0.93, FICO2: 0.07). Statistical analysis for contractile and ventilatory function tests was performed as described previously.25

Efferent phrenic nerve recordings. Mice were anesthetized with 2–3% isoflurane, trachea canulated, and connected to a ventilator (model SAR-830/AP; CWE, Ardmore, PA). Ventilator settings were manipulated to produce partial pressures of arterial CO2 between 45 and 55 mm Hg. A jugular catheter was implanted and used to transition the mice from isoflurane to urethane (1.0–1.6g/kg) anesthesia. A carotid arterial catheter was inserted to enable blood pressure measurements (Ohmeda P10-EZ; Ohmeda, Murray Hill, NJ) and withdrawal of 0.15-ml samples for measuring arterial PCO2 (I-Stat; Abbott Point of Care, East Windsor, NJ). Mice were vagotomized bilaterally and paralyzed (pancuronium bromide; 2.5 mg/kg, i.v.). The right phrenic nerve was isolated and placed on a bipolar tungsten wire electrode. Nerve electrical activities were amplified (2,000×) and filtered (100–10,000 Hz, model BMA 400; CWE). When monitoring spontaneous inspiratory activity in the phrenic neurogram, the amplified signal was full-wave rectified and smoothed with a time constant of 100 ms, digitized and recorded on a computer using Spike2 software (Cambridge Electronic Design, Cambridge, UK). The amplifier gain settings and signal processing methods were identical in all experimental animals. The 30-second before each blood draw were analyzed for the mean phrenic inspiratory burst amplitude from these digitized records.25,49

SUPPLEMENTARY MATERIALFigure S1. Targeted delivery of the transgene is restricted to the diaphragm using a gel-mediated application.Figure S2. Correction is attributed to direct transduction of diaphragm tissue and not cross-correction.

Supplementary Material

Targeted delivery of the transgene is restricted to the diaphragm using a gel-mediated application.

Correction is attributed to direct transduction of diaphragm tissue and not cross-correction.

Acknowledgments

We gratefully acknowledge the University of Florida Powell Gene Therapy Center Vector Core Laboratory, which produced some of the rAAV vectors used in this study, the University of Florida Powell Gene Therapy NGVL Toxicology Core Center for nucleic acid analysis, and the University of Florida Molecular Pathology and Immunology Core for assistance in histologic analysis. This work was supported by grants from the National Institutes of Health (NHLBI P01 HL59412-06, NIDDK P01 DK58327-03, 1R01HD052682-01A1, NHLBI-1F32HL095282-01A1 (D.J.F.)) and the American Heart Association National Center (C.M.). B.J.B., The Johns Hopkins University, and the University of Florida could be entitled to patent royalties for inventions described in this article.

REFERENCES

- Hirschhorn R., and , Reuser AJJ.2001Glycogen storage disease type II: acid α-glucosidase (acid maltase) deficiencyIn: Scriver CR, Beaudet A, Sly WS, Valle D (eds). The Metabolic and Molecular Bases of Inherited Disease McGraw-Hill: New York, pp 3389–3420 [Google Scholar]

- Baudhuin P, Hers HG., and , Loeb H. An electron microscopic and biochemical study of type II glycogenosis. Lab Invest. 1964;13:1139–1152. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kessler PD, Podsakoff GM, Chen X, McQuiston SA, Colosi PC, Matelis LA, et al. Gene delivery to skeletal muscle results in sustained expression and systemic delivery of a therapeutic protein. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93:14082–14087. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.24.14082. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hagemans ML, van Schie SP, Janssens AC, van Doorn PA, Reuser AJ., and , van der Ploeg AT. Fatigue: an important feature of late-onset Pompe disease. J Neurol. 2007;254:941–945. doi: 10.1007/s00415-006-0434-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raben N, Plotz P., and , Byrne BJ. Acid α-glucosidase deficiency (glycogenosis type II, Pompe disease. Curr Mol Med. 2002;2:145–166. doi: 10.2174/1566524024605789. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reuser AJ, Kroos MA, Hermans MM, Bijvoet AG, Verbeet MP, Van Diggelen OP, et al. Glycogenosis type II (acid maltase deficiency) Muscle Nerve. 1995;3:S61–S69. doi: 10.1002/mus.880181414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kishnani PS, Corzo D, Nicolino M, Byrne B, Mandel H, Hwu WL, et al. Recombinant human acid α-glucosidase: major clinical benefits in infantile-onset Pompe disease. Neurology. 2007;68:99–109. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000251268.41188.04. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lachmann RH. α-Glucosidase (CHO) (Genzyme) Curr Opin Investig Drugs. 2004;5:1101–1110. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cresawn KO, Fraites TJ, Wasserfall C, Atkinson M, Lewis M, Porvasnik S, et al. Impact of humoral immune response on distribution and efficacy of recombinant adeno-associated virus-derived acid α-glucosidase in a model of glycogen storage disease type II. Hum Gene Ther. 2005;16:68–80. doi: 10.1089/hum.2005.16.68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fraites TJ Jr, Schleissing MR, Shanely RA, Walter GA, Cloutier DA, Zolotukhin I, et al. Correction of the enzymatic and functional deficits in a model of Pompe disease using adeno-associated virus vectors. Mol Ther. 2002;5(5 Pt 1):571–578. doi: 10.1006/mthe.2002.0580. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mah C, Fraites TJ Jr, Cresawn KO, Zolotukhin I, Lewis MA., and , Byrne BJ. A new method for recombinant adeno-associated virus vector delivery to murine diaphragm. Mol Ther. 2004;9:458–463. doi: 10.1016/j.ymthe.2004.01.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mah C, Cresawn KO, Fraites TJ Jr, Pacak CA, Lewis MA, Zolotukhin I, et al. Sustained correction of glycogen storage disease type II using adeno-associated virus serotype 1 vectors. Gene Ther. 2005;12:1405–1409. doi: 10.1038/sj.gt.3302550. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mah C, Pacak CA, Cresawn KO, Deruisseau LR, Germain S, Lewis MA, et al. Physiological correction of Pompe disease by systemic delivery of adeno-associated virus serotype 1 vectors. Mol Ther. 2007;15:501–507. doi: 10.1038/sj.mt.6300100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rucker M, Fraites TJ Jr, Porvasnik SL, Lewis MA, Zolotukhin I, Cloutier DA, et al. Rescue of enzyme deficiency in embryonic diaphragm in a mouse model of metabolic myopathy: Pompe disease. Development. 2004;131:3007–3019. doi: 10.1242/dev.01169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun B, Zhang H, Franco LM, Brown T, Bird A, Schneider A, et al. Correction of glycogen storage disease type II by an adeno-associated virus vector containing a muscle-specific promoter. Mol Ther. 2005;11:889–898. doi: 10.1016/j.ymthe.2005.01.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun B, Young SP, Li P, Di C, Brown T, Salva MZ, et al. Correction of multiple striated muscles in murine pompe disease through adeno-associated virus-mediated gene therapy. Mol Ther. 2008;16:1366–1371. doi: 10.1038/mt.2008.133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ziegler RJ, Bercury SD, Fidler J, Zhao MA, Foley J, Taksir TV, et al. Ability of adeno-associated virus serotype 8-mediated hepatic expression of acid α-glucosidase to correct the biochemical and motor function deficits of presymptomatic and symptomatic Pompe mice. Hum Gene Ther. 2008;19:609–621. doi: 10.1089/hum.2008.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berns KI., and , Giraud C. Biology of adeno-associated virus. Curr Top Microbiol Immunol. 1996;218:1–23. doi: 10.1007/978-3-642-80207-2_1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gao G, Vandenberghe LH., and , Wilson JM. New recombinant serotypes of AAV vectors. Curr Gene Ther. 2005;5:285–297. doi: 10.2174/1566523054065057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rutledge EA, Halbert CL., and , Russell DW. Infectious clones and vectors derived from adeno-associated virus (AAV) serotypes other than AAV type 2. J Virol. 1998;72:309–319. doi: 10.1128/jvi.72.1.309-319.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zolotukhin S, Potter M, Zolotukhin I, Sakai Y, Loiler S, Fraites TJ, Jr, et al. Production and purification of serotype 1, 2, and 5 recombinant adeno-associated viral vectors. Methods. 2002;28:158–167. doi: 10.1016/s1046-2023(02)00220-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zincarelli C, Soltys S, Rengo G., and , Rabinowitz JE. Analysis of AAV serotypes 1-9 mediated gene expression and tropism in mice after systemic injection. Mol Ther. 2008;16:1073–1080. doi: 10.1038/mt.2008.76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chao H, Monahan PE, Liu Y, Samulski RJ., and , Walsh CE. Sustained and complete phenotype correction of hemophilia B mice following intramuscular injection of AAV1 serotype vectors. Mol Ther. 2001;4:217–222. doi: 10.1006/mthe.2001.0449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xiao W, Chirmule N, Berta SC, McCullough B, Gao G., and , Wilson JM. Gene therapy vectors based on adeno-associated virus type 1. J Virol. 1999;73:3994–4003. doi: 10.1128/jvi.73.5.3994-4003.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeRuisseau LR, Fuller DD, Qiu K, DeRuisseau KC, Donnelly WH Jr, Mah C, et al. Neural deficits contribute to respiratory insufficiency in Pompe disease. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2009;106:9419–9424. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0902534106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petrof BJ, Acsadi G, Jani A, Massie B, Bourdon J, Matusiewicz N, et al. Efficiency and functional consequences of adenovirus-mediated in vivo gene transfer to normal and dystrophic (mdx) mouse diaphragm. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 1995;13:508–517. doi: 10.1165/ajrcmb.13.5.7576685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petrof BJ, Acsadi G, Bourdon J, Matusiewicz N., and , Yang L. Phenotypic and immunologic factors affecting plasmid-mediated in vivo gene transfer to rat diaphragm. Am J Physiol. 1996;270(6 Pt 1):L1023–L1030. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.1996.270.6.L1023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang L, Lochmuller H, Luo J, Massie B, Nalbantoglu J, Karpati G, et al. Adenovirus-mediated dystrophin minigene transfer improves muscle strength in adult dystrophic (MDX) mice. Gene Ther. 1998;5:369–379. doi: 10.1038/sj.gt.3300600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gregorevic P, Blankinship MJ, Allen JM, Crawford RW, Meuse L, Miller DG, et al. Systemic delivery of genes to striated muscles using adeno-associated viral vectors. Nat Med. 2004;10:828–834. doi: 10.1038/nm1085. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koppanati BM, Li J, Xiao X., and , Clemens PR. Systemic delivery of AAV8 in utero results in gene expression in diaphragm and limb muscle: treatment implications for muscle disorders. Gene Ther. 2009;16:1130–1137. doi: 10.1038/gt.2009.71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu Z, Miller E, Agbandje-McKenna M., and , Samulski RJ. α2,3 and α2,6 N-linked sialic acids facilitate efficient binding and transduction by adeno-associated virus types 1 and 6. J Virol. 2006;80:9093–9103. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00895-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yan Z, Lei-Butters DC, Liu X, Zhang Y, Zhang L, Luo M, et al. Unique biologic properties of recombinant AAV1 transduction in polarized human airway epithelia. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:29684–29692. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M604099200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ding E, Hu H, Hodges BL, Migone F, Serra D, Xu F, et al. Efficacy of gene therapy for a prototypical lysosomal storage disease (GSD-II) is critically dependent on vector dose, transgene promoter, and the tissues targeted for vector transduction. Mol Ther. 2002;5:436–446. doi: 10.1006/mthe.2002.0563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin-Touaux E, Puech JP, Château D, Emiliani C, Kremer EJ, Raben N, et al. Muscle as a putative producer of acid α-glucosidase for glycogenosis type II gene therapy. Hum Mol Genet. 2002;11:1637–1645. doi: 10.1093/hmg/11.14.1637. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fukuda T, Roberts A, Plotz PH., and , Raben N. Acid α-glucosidase deficiency (Pompe disease) Curr Neurol Neurosci Rep. 2007;7:71–77. doi: 10.1007/s11910-007-0024-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelly ME, Zhuo J, Bharadwaj AS., and , Chao H. Induction of immune tolerance to FIX following muscular AAV gene transfer is AAV-dose/FIX-level dependent. Mol Ther. 2009;17:857–863. doi: 10.1038/mt.2009.25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xin KQ, Mizukami H, Urabe M, Toda Y, Shinoda K, Yoshida A, et al. Induction of robust immune responses against human immunodeficiency virus is supported by the inherent tropism of adeno-associated virus type 5 for dendritic cells. J Virol. 2006;80:11899–11910. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00890-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petry H, Brooks A, Orme A, Wang P, Liu P, Xie J, et al. Effect of viral dose on neutralizing antibody response and transgene expression after AAV1 vector re administration in mice. Gene Ther. 2008;15:54–60. doi: 10.1038/sj.gt.3303037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodino-Klapac LR, Lee JS, Mulligan RC, Clark KR., and , Mendell JR. Lack of toxicity of α-sarcoglycan overexpression supports clinical gene transfer trial in LGMD2D. Neurology. 2008;71:240–247. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000306309.85301.e2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang B, Li J, Qiao C, Chen C, Hu P, Zhu X, et al. A canine minidystrophin is functional and therapeutic in mdx mice. Gene Ther. 2008;15:1099–1106. doi: 10.1038/gt.2008.70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brantly ML, Chulay JD, Wang L, Mueller C, Humphries M, Spencer LT, et al. Sustained transgene expression despite T lymphocyte responses in a clinical trial of rAAV1-AAT gene therapy. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2009;106:16363–16368. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0904514106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gambetti P, DiMauro S., and , Baker L. Nervous system in Pompe's disease. Ultrastructure and biochemistry. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol. 1971;30:412–430. doi: 10.1097/00005072-197107000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foust KD, Poirier A, Pacak CA, Mandel RJ., and , Flotte TR. Neonatal intraperitoneal or intravenous injections of recombinant adeno-associated virus type 8 transduce dorsal root ganglia and lower motor neurons. Hum Gene Ther. 2008;19:61–70. doi: 10.1089/hum.2007.093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hollis ER 2nd, Kadoya K, Hirsch M, Samulski RJ., and , Tuszynski MH. Efficient retrograde neuronal transduction utilizing self-complementary AAV1. Mol Ther. 2008;16:296–301. doi: 10.1038/sj.mt.6300367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mellies U, Stehling F, Dohna-Schwake C, Ragette R, Teschler H., and , Voit T. Respiratory failure in Pompe disease: treatment with noninvasive ventilation. Neurology. 2005;64:1465–1467. doi: 10.1212/01.WNL.0000158682.85052.C0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pellegrini N, Laforet P, Orlikowski D, Pellegrini M, Caillaud C, Eymard B, et al. Respiratory insufficiency and limb muscle weakness in adults with Pompe's disease. Eur Respir J. 2005;26:1024–1031. doi: 10.1183/09031936.05.00020005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raben N, Nagaraju K, Lee E, Kessler P, Byrne B, Lee L, et al. Targeted disruption of the acid α-glucosidase gene in mice causes an illness with critical features of both infantile and adult human glycogen storage disease type II. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:19086–19092. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.30.19086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeLorme MP., and , Moss OR. Pulmonary function assessment by whole-body plethysmography in restrained versus unrestrained mice. J Pharmacol Toxicol Methods. 2002;47:1–10. doi: 10.1016/s1056-8719(02)00191-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drorbaugh JE., and , Fenn WO. A barometric method for measuring ventilation in newborn infants. Pediatrics. 1955;16:81–87. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Targeted delivery of the transgene is restricted to the diaphragm using a gel-mediated application.

Correction is attributed to direct transduction of diaphragm tissue and not cross-correction.