Abstract

The generation of membrane curvature in intracellular traffic involves many proteins that can curve lipid bilayers. Among these, dynamin-like proteins were shown to deform membranes into tubules, and thus far are the only proteins known to mechanically drive membrane fission. Because dynamin forms a helical coat circling a membrane tubule, its polymerization is thought to be responsible for this membrane deformation. Here we show that the force generated by dynamin polymerization, 18 pN, is sufficient to deform membranes yet can still be counteracted by high membrane tension. Importantly, we observe that at low dynamin concentration, polymer nucleation strongly depends on membrane curvature. This suggests that dynamin may be precisely recruited to membrane buds’ necks because of their high curvature. To understand this curvature dependence, we developed a theory based on the competition between dynamin polymerization and membrane mechanical deformation. This curvature control of dynamin polymerization is predicted for a specific range of concentrations (∼0.1–10 μM), which corresponds to our measurements. More generally, we expect that any protein that binds or self-assembles onto membranes in a curvature-coupled way should behave in a qualitatively similar manner, but with its own specific range of concentration.

Keywords: force, nucleation, fission, endocytosis, dynamin-like proteins

Membrane remodeling is an essential task of proteins involved in membrane traffic (1, 2). Dynamin is a large GTPase that has been shown to polymerize into a helical collar at the neck of endocytic buds (3), where it subsequently plays a key role in the formation of endocytic vesicles through fission (4–8). This function is fundamental, as the knockout of the dynamin neuronal isoform leads to striking defects in synapse organization and results in a strong dysfunction of neuronal activity (9). The recruitment of dynamin to endocytic buds is thought to depend on the local synthesis of phosphatidylinositol(4,5)bisphosphate (PIP2), as dynamin has a PIP2 binding pleckstrin homology (PH) domain (10). Dynamin is recruited late in clathrin-coated vesicle formation, as seen by total internal reflection fluorescence (TIRF) microscopy (11–13). Because PIP2 is also responsible for the binding of clathrin coats, it is expected to be present at the clathrin bud from the beginning of its formation. Thus, another explanation was suggested: Proteins that interact with dynamin and possess a curvature-sensing Bin-Amphiphysin-Rvs (BAR) domain (such as endophilin and amphiphysin) were proposed to sense the high curvature of the neck and recruit dynamin (14). Because the curvature of the neck is increasing during clathrin-coated vesicle formation to finally reach the range needed for BAR recruitment, this could explain the arrival of dynamin at the very late stage of clathrin-coated vesicle formation. However, in solution, dynamin spontaneously associates into helices and rings (15) with an internal radius of ≈10 nm. Dynamin can also polymerize around preformed lipid nanorods of typically 10- to 15-nm radius containing PIP2 (16) and around microtubules, onto which it was first purified (17). Binding of dynamin to liposomes has been shown to depend on liposome size (18), and theoretical calculations suggest that dynamin could be recruited by curvature-driven long-range interactions between membrane-bound dimers of dynamin (19). Taken together, these observations may indicate that dynamin polymerizes preferentially along cylindrical structures with a radius close to its spontaneous radius of curvature.

Dynamin was one of the first proteins shown to tubulate protein-free charged liposomes (8). Because the final tubules are circled by dynamin helices (8, 20), it is thought that dynamin polymerization provides the energy needed to deform the liposome membranes into a highly curved tubular structure. Another explanation is that hydrophobic loops present in the PH domain of dynamin (18) could generate spontaneous curvature like the BAR domain structure (21), and that polymerization would just be required to stabilize the tubular shape. To discriminate between these hypotheses, forces and energies involved in polymerization have to be measured.

In this paper, we have measured the polymerization force of dynamin and confirmed that it primarily deforms membranes through a scaffolding mechanism, forcing the membrane to adopt a tubular shape. We also show that the nucleation of the dynamin polymer is controlled by membrane curvature at low concentration. We find that at 440 nM dynamin in solution, spontaneous polymerization of dynamin can be triggered on tubules with radii ranging between 10 and 30 nm, but not on larger tubules. This suggests that the increasing curvature at the neck of closing clathrin-coated pits could per se trigger the polymerization of dynamin. We also provide a mathematical description of this effect that predicts the assembly curvature dependence as a function of dynamin bulk concentration, and show that even if dynamin deforms membranes at high concentration, its polymerization can be controlled by membrane curvature at low concentration.

Results

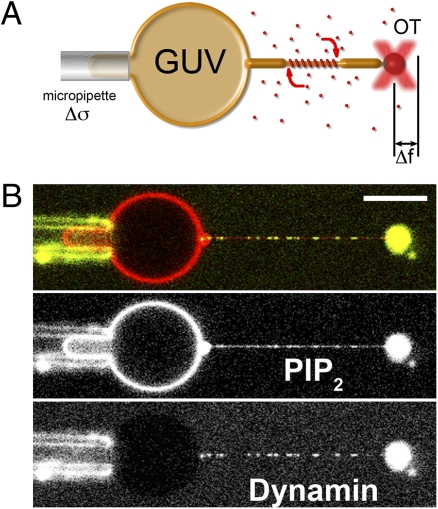

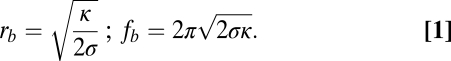

To measure the force applied by dynamin polymerization onto preformed membrane tubes with an initially imposed radius rb, we built a microscopy setup (22) that combines a micropipette used for the manipulation of giant unilamellar vesicles (GUVs) and optical tweezers (OT) to extract a membrane tube and measure the force fb to hold it (Fig. 1). The membrane tension σ of the GUV can be controlled by adjusting the aspiration pressure of the pipette (23). In the absence of proteins, the radius rb and the force fb are simply set by σ and κ, the bending rigidity of the membrane (23):

Fig. 1.

Experimental setup. (A) Schematic drawing of the experimental setup. A micropipette controls the GUV tension, Δσ, while optical tweezers are used to extract a membrane tube and measure the force needed to hold the tube (Δf) as dynamin (red) polymerizes along it. The distribution of dynamin is simultaneously measured via confocal imaging. (B) Typical dual-color image of a GUV labeled with GloPIP2 (red channel) and dynamin labeled with Alexa 488 (green channel). Inhomogeneities in the red channel are due to bleedthrough from the green channel to the red. (Scale bar, 10 μm.)

|

We thus control the radius through membrane tension and then measure the evolution of the tube force during dynamin polymerization. This also allows us to study directly the binding/nucleation of dynamin on a tube of a given radius. GUVs were formed from egg phosphatidylcholine (EPC) supplemented with 10% PIP2 (brain-purified; Avanti Polar Lipids) and 1% red fluorescent PIP2 (Echelon Biosciences). We selected EPC for its very low bending rigidity [ (24), with kB indicating Boltzmann's constant and T indicating room temperature], which allowed us to obtain very narrow tubes (Eq. 1). Incorporation of the highly charged PIP2 slightly increased the membrane bending rigidity

(24), with kB indicating Boltzmann's constant and T indicating room temperature], which allowed us to obtain very narrow tubes (Eq. 1). Incorporation of the highly charged PIP2 slightly increased the membrane bending rigidity  (Fig. S1).

(Fig. S1).

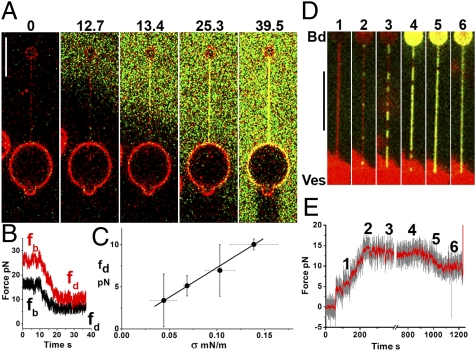

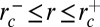

We first studied the effect of high dynamin concentrations (12 μM), exceeding the concentration required to spontaneously form tubes on low-tension membranes (6) (a few μM). After pulling a tube with the optical trap, a second pipette filled with dynamin [10–25% of which was Alexa-488-labeled (6)] was carefully positioned near the tube (see Materials and Methods). Dynamin rapidly entirely covered the tube (Fig. 2A and Movie S1). This dynamin coating stabilized the tube, as the tube did not fully retract when the OT was switched off, in stark contrast to the rapid retraction of a bare tube (Movie S2). The bead was still connected to the vesicle through the covered tubule (Fig. S2), showing that despite the absence of an external force, the dynamin coating preserved the membrane tube within it. This may indicate that the dynamin had not simply adsorbed onto the tube but rather had polymerized around it. After dynamin injection on the tube, we also observed a steep (3–20 s) drop in the tube force to a final value fd that was below fb (Fig. 2B). This provided us with a means of estimating the dynamin polymerization force: Assuming that dynamin is polymerized, we propose that, once the dynamin polymer fully covers the tube, it exerts a polymerization force P similar to a polymerizing microtubule against a membrane (25, 26). Experimentally, because the radii of dynamin-covered tubules have been reported to have a narrow dispersion (3, 8, 14, 20), we postulate that dynamin imposes a constant tube radius equal to rd, the internal radius of dynamin (SI Mathematical Modeling and ref. 27). The force of a membrane tube entirely covered by dynamin is given by (SI Mathematical Modeling)

Fig. 2.

Dynamin polymerization force measurements. (A) Sequence of confocal images following the injection of fluorescent dynamin (green; 12 μM) in the vicinity of a tube pulled from a GUV (time in seconds). (B) Plot of tube-holding force versus time after injection of dynamin (t = 0) shown for two vesicles with different membrane tensions. Dynamin rapidly reduces the tube-holding force from its initial value, fb, to a lower final level, fd (see text). (C) Plot of fd versus membrane tension showing a linear dependence (11 GUVs). (D) Images of a nucleation/growth process occurring for a dynamin concentration of 440 nM. Following a few stepwise increases of aspiration pressure (1), dots of dynamin appear on the tube (2). With the aspiration then held constant, the dynamin clusters continue to grow (2–4) until full coverage is reached (5). (E) Plot of force (smoothed average, red; raw data, gray) versus time for the experiment presented in D. The force starts to drop when dynamin fully covers the tube (5). (Scale bars, 10 μm.)

where fd is the force of the dynamin-covered tube after the force drop. It reflects the competition between the polymerization force P and the propensity of the tube to retract (Eq. 1). It thus includes contributions of membrane bending rigidity (κ) and tension (σ).

fd is expected to be linear with membrane tension σ (Eq. 2). Thus, as high membrane tension results in high retraction force, it can counteract the polymerization force of dynamin (fd > 0). The linear dependence is observed experimentally (Fig. 2C), and a fit yields:

A new measurement of the inner radius of dynamin rd = 11.2 ± 0.3 nm, consistent with existing electron microscopy data (3, 8, 14, 20) confirming that dynamin imposes its radius on the membrane.

A measurement of the polymerization force for a 12 μM solution of dynamin: P = 18.1 ± 2.0 pN. The primary unit in assembled dynamin being a dimer (28), this force is generated by the addition of one helical turn (14 dimers) along its 13-nm pitch. It corresponds to a free-energy gain (polymerization energy) of 3.8 kBT per dimer added, which is lower than the tubulin polymerization free energy (5–10 kBT) (29) but higher than that of actin (∼0.5–1.5 kBT) (30).

To confirm that dynamin was polymerized and not simply adsorbed, and to better observe the process of tube coverage, we reduced the dynamin concentration by 30-fold. In the presence of dynamin at 440 nM in solution, small dynamin seeds appeared on the tube and their length steadily increased (Fig. 2D and Movie S3) at an average rate of 14 nm/s (Fig. S3). This nucleation/growth process of dynamin structures confirms a direct polymerization, because adsorption would yield a uniform distribution on the tube. Further confirmation came from fluorescence recovery after photobleaching (FRAP) experiments, as no recovery was observed after bleaching of the dynamin-coated tube (Fig. S4). However, although optically homogeneous, the polymer coat contains discontinuities, as also shown by FRAP (Fig. S5). Even if not detected by our imaging system, the rapid appearance of the seeds suggests that their nucleation is due to dynamin dimers already adsorbed on the membrane that rapidly cluster together on the tube. While these clusters grew, the tube force remained equal to fb (Fig. 2E, 2–4), but when full coverage was reached, the force dropped to fd (see Fig. 2E, 5–6). We note that, if adsorption of dynamin to the bare tube significantly affected its spontaneous curvature or bending modulus, we would expect f ≠ fb before full coverage is reached. Hence, our observations confirm that adsorption of dynamin to the bare tube has a negligible effect on the membrane, probably because surface concentration of nonpolymerized dynamin dimers is low, and that before full coating of the tube, the force is imposed by the noncoated sections of the tube. Rather, dynamin polymerization is needed to produce the force required to bend the membrane (SI Mathematical Modeling).

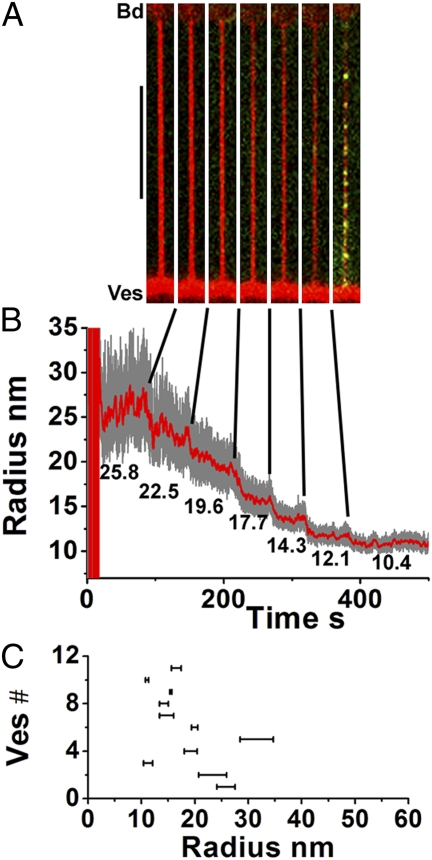

A second important observation is that, at a concentration of 440 nM, dynamin cannot polymerize on tubes that are too wide (i.e., large radii, 50–100 nm; Fig. 2D), and the nucleation of dynamin seeds requires the tube radius to be reduced through increasing the tension (Eq. 1). Only after a small enough radius was reached was polymerization suddenly triggered. Another striking fact is that dynamin was only seen on the tube and not on the GUV (see Fig. 1B). These observations suggest a strong dependence of dynamin polymerization on the curvature of the membrane. To characterize this dependence, we pulled tubes from GUVs held with low aspiration pressure. We then increased the membrane tension in discrete steps, thereby decreasing the tube radius. A typical experiment is shown in Fig. 3 A and B (see also Fig. 2 D and E and Movie S3), in which several stepwise increases of membrane tension were required before polymerization commenced. Once the radius was sufficiently small, several clusters of dynamin appeared within a few seconds (Fig. 3 A and B). For each experiment, tube radii were deduced from Eq. 1 to determine the bounds on the critical radius for dynamin polymerization. For each vesicle, the upper bound was the smallest radius before polymerization started, whereas the lower bound was the radius at which polymerization was observed. Figure 3C shows that the radius intervals for a population of 11 vesicles are spread between 10 and 35 nm, with an average value of 18.5 ± 6 nm. Therefore, we conclude that, at a concentration of 440 nM, dynamin is not able to polymerize on a membrane tube larger than approximately twice its internal diameter.

Fig. 3.

Curvature control of dynamin nucleation. Images of the membrane tube (A) (membrane, red; dynamin, green) following each stepwise reduction of tube radius (nm) as indicated in B. Polymerization of dynamin is only visible for the smallest tube radius. (Scale bar, 10 μm.) (C) Critical radius windows obtained from 11 vesicles.

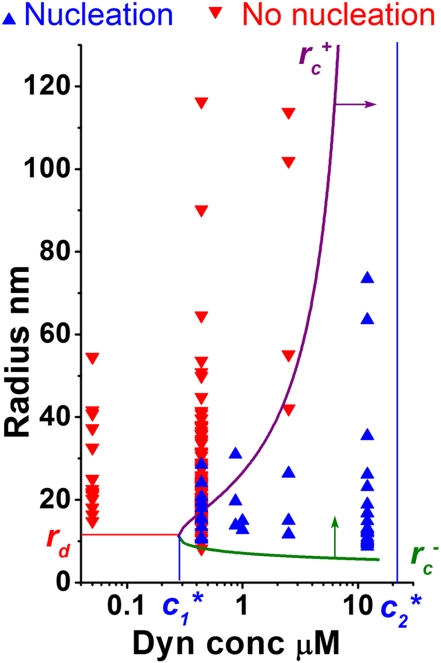

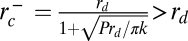

As dynamin has been described in the past as a curvature-inducing protein at high concentration, we wondered how this curvature-dependent nucleation of dynamin evolved with concentration. Strikingly, our observations suggest that the curvature-dependent nucleation of dynamin and its ability to deform membranes are not independent, as dynamin is still able to squeeze tubes under conditions where its nucleation is curvature-dependent (Fig. S6). To be able to squeeze the tube to 10 nm, dynamin polymerization onto the membrane should generate enough force to overcome the force needed to squeeze the tube more. Obviously, the force needed to squeeze a tube is dependent on its initial radius, large tubes requiring more force to be squeezed to 10 nm than smaller ones. On the other hand, dynamin polymerization force P depends only on bulk concentration, because it is equivalent to a chemical potential. By comparing these two forces, we have theoretically determined the conditions for dynamin nucleation in terms of concentration and tube radius (SI Mathematical Modeling and Fig. S7). We define conditions where nucleation occurs as values of concentration and radius for which dynamin polymerization force is higher than the force required to squeeze the tube. Here we always consider that dynamin is binding and polymerizing to a preformed tubule, and does not have to form the tubule. Our measurement of P made at 12 μM allows us to estimate P at any concentration (SI Mathematical Modeling), assuming that the dynamin solution is overall very diluted (much less than 1 M). We can then predict the existence of three regimes as a function of the concentration (Fig. 4):

Fig. 4.

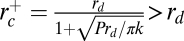

Phase diagram of dynamin nucleation as a function of tube radius and dynamin concentration. Experimental results are marked with triangles (red, inverted = no nucleation; blue, upright = nucleation). Boundaries of the region of dynamin nucleation, rc+ (purple line, arrow) and rc− (green line, arrow), were calculated for the theoretical model:  and

and  (SI Mathematical Modeling). Nucleation should not occur below the lower concentration, c1*. Above the higher concentration, c2*, nucleation should always occur, independent of membrane tube radius. rd corresponds to the internal radius of a dynamin-coated membrane tube.

(SI Mathematical Modeling). Nucleation should not occur below the lower concentration, c1*. Above the higher concentration, c2*, nucleation should always occur, independent of membrane tube radius. rd corresponds to the internal radius of a dynamin-coated membrane tube.

For very low dynamin concentrations (c < c1* = 280 nM or P < 0), a tube should always remain uncoated, independent of its initial radius. Indeed, we have checked experimentally that at 50 nM, dynamin is unable to polymerize on the tubule, however small its radius (Fig. 4).

For intermediate dynamin concentrations (c1* = 280 nM < c < c2* = 12.6 μM or 0 < P < πκ/rd), we predict that dynamin can polymerize on tubes within a restricted range of radii:

(see Fig. 4), enclosing dynamin radius value

(see Fig. 4), enclosing dynamin radius value  . Thus, if the tube is too thin (

. Thus, if the tube is too thin ( ) or too thick (

) or too thick ( ), dynamin should not be able to polymerize. As shown in Fig. 4,

), dynamin should not be able to polymerize. As shown in Fig. 4,  increases rapidly for concentrations above c1*. From the expression of

increases rapidly for concentrations above c1*. From the expression of  (see legend of Fig. 4), it is possible to calculate the critical radii for any dynamin concentration, and in particular predict that rc+ (440 nM) = 20 nm. This is consistent with the critical radius measured independently above (Fig. 3C). Also, we observe that for 2.5 μM, dynamin spontaneously polymerizes onto tubules below 30–40 nm, suggesting that the critical radius is around 40 nm, consistent with the value predicted from the theory (see purple line in Fig. 4).

(see legend of Fig. 4), it is possible to calculate the critical radii for any dynamin concentration, and in particular predict that rc+ (440 nM) = 20 nm. This is consistent with the critical radius measured independently above (Fig. 3C). Also, we observe that for 2.5 μM, dynamin spontaneously polymerizes onto tubules below 30–40 nm, suggesting that the critical radius is around 40 nm, consistent with the value predicted from the theory (see purple line in Fig. 4).For high dynamin concentrations (c > c2* = 12.6 μM or πκ/rd < P), we predict that dynamin should polymerize on all membrane tubes that have a radius of curvature larger than rd, including membrane tubes of zero curvature.

Importantly, we describe here two regimes where dynamin behaves first as a curvature sensor (its nucleation being dependent on membrane curvature; see point ii), and a regime where dynamin behaves like a curvature generator (formation of coated tubes is independent of their curvature; see point iii).

Discussion

In the first set of experiments reported above at high dynamin concentration, we have shown that dynamin actually polymerizes on preformed tubes and have measured its polymerization force at this concentration (12 μM). A first consequence of our experiments is that dynamin polymerization under these conditions generates enough force to deform membranes at low tension (<10−6 N/m). Moreover, our experiments show that for membrane tensions superior to 10−5 N/m, fd > 0 (Fig. 2C). This means that for tensions that are in the range of typical cellular membrane tensions (∼10−5 N/m) (31), dynamin should not be able to deform membranes into tubules, as its polymerization force can be overcome by high membrane tension. This supports the idea that recruitment of proteins to the membrane can be controlled by tuning cellular membrane tension, and could explain how endocytosis is up-regulated when plasma membrane tension is reduced (32).

Our second set of data shows that dynamin nucleation is strongly dependent on membrane curvature at low concentrations. This may reflect the ability of curved dynamin oligomers to preferentially polymerize on curved areas of the membrane. Moreover, the curvature-dependent nucleation of dynamin is highly concentration-dependent. More generally, any protein that interacts with membranes in a curvature-coupled manner should have the same type of concentration-dependent behavior. It can be understood in terms of the interplay between membrane curvature and chemical equilibrium between membrane-bound and -unbound forms of the protein. At low concentration the protein is mostly unbound, but preferentially binds onto curved parts of the membrane. At high bulk concentration, chemical equilibrium is displaced toward the bound form, in turn forcing the membrane to curve, as a protein-coated membrane is more stable when curved. In previous studies, the abilities of proteins to sense membrane curvature or to curve membranes have sometimes been regarded as separate functions. Our study suggests that these two functions should be effective for any protein interacting with membranes in a curvature-coupled manner. Importantly, for each protein, a specific range of concentrations (given by its specific concentrations c1* and c2*) should exist, separating conditions where the protein acts more as a curvature sensor or more as a curvature inducer. We predict that the specific physico-chemistry of membrane-protein interactions that have been described to explain curvature-sensing versus curvature-inducing functions (33, 34) will have a strong influence on the (c1*, c2*) values. To discriminate the function of a protein in vivo, one must compare its physiological concentration with its specific critical concentrations c1* and c2*. For dynamin, we found that the concentration range thought to be physiological (4) lies between c1* (a few hundred nM) and c2* (a few tens μM) and, consequently, dynamin nucleation could be regulated by membrane curvature in vivo. Our findings suggest that dynamin could be recruited to the neck of closing clathrin-coated pits when their curvature is sufficiently high, and that its polymerization further constricts them to 10 nm. In vivo, dynamin appears at the clathrin-coated pits at the end of their formation (11–13), when the neck has a radius of ∼20 nm (35), close to the value of the critical radius (19 nm) we found for dynamin at 440 nM.

Materials and Methods

Materials.

Egg L-α-phosphatidylcholine (EPC), 1,2-distearoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphoethanolamine-N-[biotinyl(polyethyleneglycol)2000] [DSPE-PEG(2000)biotin] and brain L-α-phosphatidylinositol(4,5)bisphosphate [PtdIns(4,5)P2] were obtained from Avanti Polar Lipids. Red fluorescent GloPIPs BODIPY TMR-PtdIns(4,5)P2-C16 (GloPIP2) was obtained from Echelon Biosciences.

Giant Unilamellar Vesicles.

Giant unilamellar vesicles were formed using a slightly adapted version of the electroformation method (36, 37). A mixture of 30 μL CHCl3, 2.25 μL EPC (10 mg/mL), 1 μL PtdIns(4,5)P2 (5 mg/mL), 1 μL of GloPIP2 (0.25 mg/mL), and 0.4 μL DSPE-PEG(2000)biotin (10−2 mg/mL) was made. This mixture was vortexed, heated to 50 °C, and spread on two indium titanium oxide (ITO)-coated glass slides with a Hamilton syringe in an oven at 50 °C to prevent demixing of the lipids and ensure a homogeneous distribution of PIP2. The lipid deposits were further dried by leaving the slides 1 h at 50 °C. Next, a growth chamber was built using the ITO slides, which were separated by Teflon spacers and sealed with Vitrex wax (37). The chamber was then filled with a sucrose solution at 213 mOsm, osmotically equilibrated with the experimental GTPase buffer [20 mM Hepes (pH 7.4), 100 mM NaCl, 1 mM MgCl2]. An AC field (10 Hz, 1.1 V) was then applied for 2 h while keeping the chamber at 50 °C.

Dynamin Purification.

Dynamin was purified from rat brains using the GST-tagged SH3 domain of rat amphiphysin 1 as an affinity ligand as previously described (6, 16). Briefly, six brains were homogenized with a 60-mL dounce in buffer A [20 mM Hepes (pH 7.4), 150 mM NaCl, 1 mM EGTA, 1 mM DTT, 1% Triton X-100] and centrifuged at 40 krpm in a Ti70 rotor (Beckman), and the supernatant was incubated for 2 h with glutathione beads to which 3–5 mg of SH3 domain of amphiphysin was attached. Next, the beads were batch-washed several times. Elution was done with high salt [20 mM Hepes (pH 7.4), 1.2 M NaCl, 1 mM MgCl2]. Unlabeled dynamin was dialyzed against storage buffer [20 mM Hepes (pH 7.4), 100 mM NaCl, 1 mM MgCl2], concentrated using Amicon devices (50 kDa CO), aliquoted, flash-frozen in liquid N2, and stored at −80 °C.

To fluorescently label dynamin, we dialyzed dynamin against PBS, 50% glycerol. The labeling reaction was conducted using standard procedures (Alexa-488 protein-labeling kit from Invitrogen). Fluorescently labeled protein was further dialyzed (2–3 h) against storage buffer, concentrated, aliquoted, flash-frozen in liquid N2, and stored at −80 °C.

Experimental Setup.

The setup was based on a commercial Nikon TE2000 inverted microscope modified with the optional stage riser (Nikon) to create an extra port (22). The confocal head was the eC1 confocal system (Nikon) with two laser lines (λ = 488 nm; λ = 543 nm).

The micropipette technique has already been described (38), and was used for setting GUV tension. Pipette manipulation was achieved with a homemade micromanipulator clamped on the microscope. In our experiments, a micropipette of about 3- to 4 μm diameter at the tip was connected to a mobile water reservoir, which allowed control of the membrane tension of the GUV from 5.10−6 to 2.10−4 N·m−1.

To create a single, non-moving optical trap, light from an ytterbium fiber laser (1070 nm, 5 W, continuous wave; IPG GmBH) was injected into a 100×/1.3 NA oil immersion objective (Nikon) using a heat-reflecting mirror (λc = 900 nm; Melles Griot). The x-y-z position of the trap was set with external optics in a configuration similar to that in ref. 24. The position of the polystyrene bead in the trap was recorded and analyzed off-line using custom-made video-tracking software (Konstantin Zeldovitch, Paris, France) with a temporal resolution of 40 ms and a subpixel spatial resolution of 35 nm. The trap stiffness was calibrated using the Stokes drag force method (39). The stiffness of the tweezers was found to be 450 ± 30 pN·nm−1·W−1.

Bright field imaging was done using a fluorescence illumination arm as an imaging port. To do so, the fluorescence filter cube was replaced by a heat-reflecting mirror (λc = 750 nm; PGO GmBH Iserlohn) and a convergent lens was added to the fluorescence excitation path to project the field diaphragm plane on a video camera. The video signal was then digitized using Labview-based custom software. To avoid overlap between bright field and confocal data, only near-infrared light was used for bright field illumination. This was achieved by inserting a bandpass filter (750–900 nm; visible light absorbing RG9 Schott glass) in front of the bright field illumination halogen lamp of the microscope.

Sample Preparation.

Three to four microliters of streptavidin-coated polystyrene beads of 3.2-μm diameter diluted 20 times (Spherotech) were mixed with 200 μL GTPase buffer and 2–5 μL of GUVs taken directly from the growth chamber. In experiments with dynamin in bulk, unlabeled dynamin and fluorescent dynamin (10–20% mol/mol) were added to this solution to obtain the appropriate concentration. This solution was inserted into the sample chamber which was previously incubated with 4 mg/mL casein in GTPase buffer for 5 min.

In experiments in which a second micropipette was used for local dynamin injection, a 10- to 12 μm-wide pipette was filled with 3–5 μL dynamin solution by capillary. Then, the dynamin solution was pushed toward the tip of the pipette by connecting it to an Eppendorf Femtojet microinjector and applying high pressure (100–300 mPa). Once the solution reached the tip, the pressure was reduced to its minimum (15 mPa) and the pipette was inserted into the chamber. The pipette was kept at a continuous flow, and the pipette was moved into the observation field to perform local injections of dynamin.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank J. Heuvingh, K. Carvalho, and C. Picart for constructive exchanges on PIP2 reconstitution, G. Toombes for a critical reading of the manuscript, and B. Goud, J.F. Joanny, and J. Prost for stimulating discussions. This work was supported by the European Commission (NoE SoftComp and Specific Targeted Research Projects Active Biomics) (P.B.), Institut Curie (PIC Physique du Vivant) (P.B. and P.N.), Centre National de la Recherche Scientifique (“Interface Physique Chimie Biologie: Soutien à la Prise de Risque”) (A.R.), Agence Nationale de la Recherche (Young Investigator Program, JC08_317536) (A.R.), and Human Frontier Science Program Career Development Award 0061/2008 (A.R.). Our lab belongs to the French research consortium “CellTiss.” G.K. was supported by EU (Active Biomics) and a European Molecular Biology Organization long-term postdoctoral fellowship.

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

*This Direct Submission article had a prearranged editor.

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/cgi/content/full/0913734107/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Antonny B. Membrane deformation by protein coats. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 2006;18:386–394. doi: 10.1016/j.ceb.2006.06.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Zimmerberg J, Kozlov MM. How proteins produce cellular membrane curvature. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2006;7:9–19. doi: 10.1038/nrm1784. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Takei K, McPherson PS, Schmid SL, De Camilli P. Tubular membrane invaginations coated by dynamin rings are induced by GTP-γ S in nerve terminals. Nature. 1995;374:186–190. doi: 10.1038/374186a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pucadyil TJ, Schmid SL. Real-time visualization of dynamin-catalyzed membrane fission and vesicle release. Cell. 2008;135:1263–1275. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.11.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bashkirov PV, et al. GTPase cycle of dynamin is coupled to membrane squeeze and release, leading to spontaneous fission. Cell. 2008;135:1276–1286. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.11.028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Roux A, Uyhazi K, Frost A, De Camilli P. GTP-dependent twisting of dynamin implicates constriction and tension in membrane fission. Nature. 2006;441:528–531. doi: 10.1038/nature04718. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Praefcke GJ, McMahon HT. The dynamin superfamily: Universal membrane tubulation and fission molecules? Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2004;5:133–147. doi: 10.1038/nrm1313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sweitzer SM, Hinshaw JE. Dynamin undergoes a GTP-dependent conformational change causing vesiculation. Cell. 1998;93:1021–1029. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81207-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ferguson SM, et al. A selective activity-dependent requirement for dynamin 1 in synaptic vesicle endocytosis. Science. 2007;316:570–574. doi: 10.1126/science.1140621. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Salim K, et al. Distinct specificity in the recognition of phosphoinositides by the pleckstrin homology domains of dynamin and Bruton's tyrosine kinase. EMBO J. 1996;15:6241–6250. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ehrlich M, et al. Endocytosis by random initiation and stabilization of clathrin-coated pits. Cell. 2004;118:591–605. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2004.08.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Merrifield CJ, Feldman ME, Wan L, Almers W. Imaging actin and dynamin recruitment during invagination of single clathrin-coated pits. Nat Cell Biol. 2002;4:691–698. doi: 10.1038/ncb837. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rappoport JZ, Heyman KP, Kemal S, Simon SM. Dynamics of dynamin during clathrin mediated endocytosis in PC12 cells. PLoS One. 2008;3:e2416. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0002416. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Takei K, Slepnev VI, Haucke V, De Camilli P. Functional partnership between amphiphysin and dynamin in clathrin-mediated endocytosis. Nat Cell Biol. 1999;1:33–39. doi: 10.1038/9004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hinshaw JE, Schmid SL. Dynamin self-assembles into rings suggesting a mechanism for coated vesicle budding. Nature. 1995;374:190–192. doi: 10.1038/374190a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Stowell MH, Marks B, Wigge P, McMahon HT. Nucleotide-dependent conformational changes in dynamin: Evidence for a mechanochemical molecular spring. Nat Cell Biol. 1999;1:27–32. doi: 10.1038/8997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Shpetner HS, Vallee RB. Identification of dynamin, a novel mechanochemical enzyme that mediates interactions between microtubules. Cell. 1989;59:421–432. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(89)90027-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ramachandran R, Schmid SL. Real-time detection reveals that effectors couple dynamin's GTP-dependent conformational changes to the membrane. EMBO J. 2008;27:27–37. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7601961. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Fournier JB, Dommersnes PG, Galatola P. Dynamin recruitment by clathrin coats: A physical step? C R Biol. 2003;326:467–476. doi: 10.1016/s1631-0691(03)00096-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Danino D, Moon KH, Hinshaw JE. Rapid constriction of lipid bilayers by the mechanochemical enzyme dynamin. J Struct Biol. 2004;147:259–267. doi: 10.1016/j.jsb.2004.04.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Farsad K, et al. Generation of high curvature membranes mediated by direct endophilin bilayer interactions. J Cell Biol. 2001;155:193–200. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200107075. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sorre B, et al. Curvature-driven lipid sorting needs proximity to a demixing point and is aided by proteins. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2009;106:5622–5626. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0811243106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Derényi I, Jülicher F, Prost J. Formation and interaction of membrane tubes. Phys Rev Lett. 2002;88:238101. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.88.238101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Cuvelier D, Derényi I, Bassereau P, Nassoy P. Coalescence of membrane tethers: Experiments, theory, and applications. Biophys J. 2005;88:2714–2726. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.104.056473. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Daniels DR, Turner MS. Spicules and the effect of rigid rods on enclosing membrane tubes. Phys Rev Lett. 2005;95:238101. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.95.238101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Fygenson D, Marko J, Libchaber A. Mechanics of microtubule-based membrane extension. Phys Rev Lett. 1997;79:4497–4500. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lenz M, Prost J, Joanny JF. Mechanochemical action of the dynamin protein. Phys Rev E Stat Nonlin Soft Matter Phys. 2008;78:011911. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevE.78.011911. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mears JA, Ray P, Hinshaw JE. A corkscrew model for dynamin constriction. Structure. 2007;15:1190–1202. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2007.08.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Dogterom M, Kerssemakers JW, Romet-Lemonne G, Janson ME. Force generation by dynamic microtubules. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 2005;17:67–74. doi: 10.1016/j.ceb.2004.12.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Footer MJ, Kerssemakers JW, Theriot JA, Dogterom M. Direct measurement of force generation by actin filament polymerization using an optical trap. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2007;104:2181–2186. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0607052104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Raucher D, Sheetz MP. Characteristics of a membrane reservoir buffering membrane tension. Biophys J. 1999;77:1992–2002. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(99)77040-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Dai J, Ting-Beall HP, Sheetz MP. The secretion-coupled endocytosis correlates with membrane tension changes in RBL 2H3 cells. J Gen Physiol. 1997;110:1–10. doi: 10.1085/jgp.110.1.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Peter BJ, et al. BAR domains as sensors of membrane curvature: The amphiphysin BAR structure. Science. 2004;303:495–499. doi: 10.1126/science.1092586. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Drin G, et al. A general amphipathic α-helical motif for sensing membrane curvature. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2007;14:138–146. doi: 10.1038/nsmb1194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Newton AJ, Kirchhausen T, Murthy VN. Inhibition of dynamin completely blocks compensatory synaptic vesicle endocytosis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2006;103:17955–17960. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0606212103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Angelova MI, Soléau S, Méléard P, Faucon JF, Bothorel P. Preparation of giant vesicles by external AC electric fields. Kinetics and applications. Prog Colloid Polym Sci. 1992;89:127–131. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Carvalho K, Ramos L, Roy C, Picart C. Giant unilamellar vesicles containing phosphatidylinositol(4,5)bisphosphate: Characterization and functionality. Biophys J. 2008;95:4348–4360. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.107.126912. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Needham D, Evans E. Structure and mechanical properties of giant lipid (DMPC) vesicle bilayers from 20°C below to 10°C above the liquid crystal-crystalline phase transition at 24°C. Biochemistry. 1988;27:8261–8269. doi: 10.1021/bi00421a041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Neuman KC, Block SM. Optical trapping. Rev Sci Instrum. 2004;75:2787–2809. doi: 10.1063/1.1785844. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.