Abstract

Fast identification of protein structures that are similar to a specified query structure in the entire Protein Data Bank (PDB) is fundamental in structure and function prediction. We present FragBag: An ultrafast and accurate method for comparing protein structures. We describe a protein structure by the collection of its overlapping short contiguous backbone segments, and discretize this set using a library of fragments. Then, we succinctly represent the protein as a “bags-of-fragments”—a vector that counts the number of occurrences of each fragment—and measure the similarity between two structures by the similarity between their vectors. Our representation has two additional benefits: (i) it can be used to construct an inverted index, for implementing a fast structural search engine of the entire PDB, and (ii) one can specify a structure as a collection of substructures, without combining them into a single structure; this is valuable for structure prediction, when there are reliable predictions only of parts of the protein. We use receiver operating characteristic curve analysis to quantify the success of FragBag in identifying neighbor candidate sets in a dataset of over 2,900 structures. The gold standard is the set of neighbors found by six state of the art structural aligners. Our best FragBag library finds more accurate candidate sets than the three other filter methods: The SGM, PRIDE, and a method by Zotenko et al. More interestingly, FragBag performs on a par with the computationally expensive, yet highly trusted structural aligners STRUCTAL and CE.

Keywords: evaluation of structure search, fast structural search of Protein Data Bank, filter and refine, protein backbone fragments, protein structure search

Finding structural neighbors of a protein, i.e., proteins that share with it a sizable substructure, is an important yet persistently difficult, task. Such structural neighbors may hint at a protein’s function or evolutionary origin even without detectable sequence similarity, as structure is more conserved than sequence. Indeed, many methods for protein function (1, 2) and structure (3) prediction rely on finding such neighbors. Structural classifications such as SCOP (4) and CATH (5) identify some neighbors; however, there are many other neighbors, which although classified differently, are actually structurally similar and important for function and structure prediction (1, 6). Devising fast, accurate, yet comprehensive, structural search tools for the rapidly growing Protein Data Bank (PDB) remains an important challenge.

Structural alignment quantifies the similarity between two protein structures, by identifying two equally sized, geometrically similar substructures. Many structural alignment methods have been proposed over the past twenty years [e.g., STRUCTAL (7), CE (8), and SSM (9)]. Regardless of the way they quantify similarity and their search heuristics, one can define a common similarity score to assess the resulting alignments, and create a best-of-all method that gives the best alignment under that score (10). Unfortunately, aligning two structures is an expensive computation (10); thus, many structural alignment servers consider only a representative subset of the Protein Data Bank (PDB) (e.g. FATCAT (11) and CE). However, by using such sequence-nonredundant representative sets we risk excluding interesting structural variability (12). In any case, naively structurally aligning a query against the entire PDB, or structurally aligning all PDB structures against one another, is prohibitively expensive, as it requires O(n) or O(n2) computationally intensive comparisons.

To search the entire PDB efficiently, researchers devised the “filter and refine” paradigm (13). A filter method quickly sifts through a large set of structures, and selects a small candidate set to be structurally aligned by a more accurate, but computationally expensive, method. Filter methods gain their speed by representing structures abstractly—typically as vectors—and comparing these representations quickly. Such vector representations allow constructing an inverted index—a data structure that enables fast retrieval of neighbors, even in huge datasets [e.g. (14)]. PRIDE represents a structure by the histograms of diagonals in its internal distance matrix, and measures similarity between two structures by the similarity between their histograms (15). Choi et al. (16) represent a structure by a vector of frequencies of local features in its internal distance matrix, and measure similarity between two structures by the distance between their corresponding vectors. Inspired by knot theory, Rögen and Fain devised the Scaled Gauss Metric (SGM) method, which represents a structure by a vector of 30 global topological measures of its backbone (17). Zotenko et al. (18) represent a protein structure by a vector of the frequencies of patterns of secondary structure element (SSE) triplets. Several methods [e.g., (19), (20)] represent a structure as an ordered string of structural fragments, and sequence-align these strings to measure structural similarity; such representations are less suitable for constructing an inverted index.

To search in very large datasets, computer scientists often represent objects as “bag-of-words” (BOW)—unordered collections of local features. Web search engines use an inverted index of the BOW representation of the web. Each document and query is represented by the number of occurrences of its words (21). In Computer Vision, texture images are represented as BOW of local image features for texture recognition, object classification, and image and video retrieval [e.g., (22–23)]. In protein sequence analysis, Leslie and coworkers described protein sequences as a BOW of their k-mers for detecting remote homology (24).

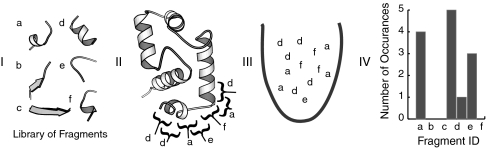

In FragBag we represent a protein structure as a BOW of backbone fragments, and use this representation to identify quickly good candidate sets of structural neighbors. Specifically, we represent a structure by a vector whose entries count the number of times each fragment approximates a segment in the protein backbone (Fig. 1), and measure similarity between two structures by the similarity between their corresponding vectors. In testing our approach, we consider 24 libraries of various sizes and fragment lengths, and use three BOW similarity measures (Euclidean, Cosine, and Histogram Intersection). We study how well different measures identify structural neighbors, relative to a stringent gold standard: The structural neighbors found by a best-of-six structural alignment method (10). We also test statistically whether BOW representations of structures within CATH categories are indeed similar to each other. We then compare the performance of our measure with that of other filter methods SGM, Zotenko et al. (18), and PRIDE, to BLAST sequence alignment (25), and to the structural alignment methods STRUCTAL, CE, and SSM.

Fig. 1.

FragBag representation of protein structure. (A) For illustration, we consider a library of 6 fragments. (B) Each (overlapping) contiguous segment in the backbone is associated with its most similar library fragment. (C) All fragments are collected to an unordered “bag.” (D) The structure is represented by a vector v, whose entries count the number of times each library fragment appeared in the bag. In this example, v = (4,0,0,5,1,3), implying fragment order (a, b, c, d, e, f).

Our best filter method outperforms other filter methods and BLAST. More importantly, it performs on a par with the computationally expensive structural aligners STRUCTAL and CE. In our tests, the ranking of the methods is insensitive to the threshold value defining structural neighbors. Comparing FragBag vectors is orders of magnitudes faster than structural alignment; it also is well suited for using in inverted indices. Thus, our method can be used to quickly identify good candidate sets of structural neighbors in the entire PDB.

Results

In FragBag, the bag-of-fragments that represents a protein structure is succinctly described by a vector of length N, the size of the fragment library. Fig. 1 illustrates how this vector is calculated from the α-Carbon coordinates of a protein. For each contiguous (and overlapping) k-residue segment along the protein backbone, we identify the library fragment of length k that fits it best in terms of rmsd after optimal superposition. Then, we count the number of times each library fragment was used, and describe the protein by a vector of these counts.

Comparing Filter Methods via Receiver Operating Characteristic (ROC) Curve Analysis.

We measure the accuracy of structural retrieval methods by how well they identify candidate sets of structural neighbors in a database, given a query structure. We consider a database of 2,928 sequence-nonredundant structures, and query it by each of its structures. The gold-standard answer includes neighbors found by a best-of-six structural aligner (using SSAP (26), STRUCTAL, DALI (27), LSQMAN (28), CE, and SSM); this expensive computation was done previously (10). Structural neighbors of the query are ones aligned to it with a structural alignment score [SAS; see Methods for definition (7)] below a threshold T (for T = 2 Å, 3.5 Å, and 5 Å). We use the area under the curve (AUC) of the ROC curves to measure how well each method identifies the structural neighbors of a query, and average the AUCs over all 2,928 queries. A higher AUC is better: A perfect imitator of the gold standard, which ranks the structural neighbors before all other proteins, will have an AUC of 1, whereas a random measure will have an AUC of 0.5.

Fig. 2 (Left) shows the average AUCs with respect to the three gold standards defined above (corresponding to the three values of T) for 24 libraries (with 20–600 fragments of length 5–12 residues). We consider three BOW similarity measures: Cosine, Histogram Intersection, and Euclidean distances. For comparison, the right panel shows the average AUCs of other methods: (i) a sequence-based method using BLAST’s E-value (25), (ii) the filter methods PRIDE, SGM, and that of Zotenko et al. (18), and (iii) the structure aligners STRUCTAL, CE, and SSM. We sort the alignments by their SAS scores, and for STRUCTAL and CE, also by their native scores. The average AUCs plotted in Fig. 2 are also available as supplementary material (Table S1). The ranking of the performance of different methods is generally independent of T, the threshold defining structural neighbors. Under the strictest definition, the neighbors of a protein are only structures that were aligned with an SAS score < 2 Å; under the most lax definition, the neighbors are the structures that were aligned with an SAS score < 5 Å. As expected, all methods perform better (i.e., achieve higher average AUCs) when the definition of structural neighbors is more strict, and less well when the definition includes more distant structures. Because structures with a SAS score < 5 Å are often the most meaningful neighbors, which are difficult to detect accurately, we are most interested in identifying methods that excel under this stringent test (see Discussion).

Fig. 2.

The average AUC of ROC curves of identifying structural neighbors. The AUC measures how well a ranking of structures imitates the ranking according to a gold standard; larger values correspond to more successful imitators, ranging from 0.5 (a random ranker) to 1 (a perfect imitator). We consider three definitions of structural neighbors, using SAS thresholds of 2 Å, 3.5 Å, and 5 Å. The left panels show the performance of libraries with fragments of 6–12 residues, and different number of fragments (value along the x-axis), and using the cosine (plus sign), Euclidean (circles), and Histogram Intersection (diamonds) distances. On the right we compare the best FragBag result (400(11) library and the cosine distance) to other methods: Sequence-based similarity measure in finely dashed black, filter methods in dashed black, and structure alignment methods in solid black. We see that the FragBag performs similarly to CE and STRUCTAL—two computationally expensive and well-trusted structural aligners.

FragBag’s best result is with the 400(11) library (400 fragments of length 11) and the cosine distance; the average AUCs are 0.89 (T = 2 Å), 0.77 (T = 3.5 Å), and 0.75 (T = 5 Å). The cosine distance performs best. When using cosine distance or the histogram intersection distance, larger libraries (which describe local structure variability in higher detail), typically perform better. From comparing libraries of fixed size (100, 200, or 400 fragments), we learn that when using cosine distance, libraries of longer fragments perform better; when using the histogram intersection or the Euclidean distances, the length of the fragment does not influence the results.

The ranking of the filter methods from most to least successful is (i) FragBag (using the 400(11) library and cosine distance), (ii) SGM, (iii) Zotenko et al.’s method (18), and (iv) PRIDE, which performs similarly to the sequence-based method. Among the structural aligners, the most successful is SSM, followed by STRUCTAL and CE.

Fig. 2 and Table 1 show that the best filter method, i.e., the FragBag representation mentioned above, performs on a par with CE and STRUCTAL, two computationally expensive and highly trusted structural aligners. For example, using the T = 5 Å threshold, FragBag has an average AUC of 0.75, which is similar to CE’s 0.74 using the native score, and 0.75 using SAS score; it is lower than STRUCTAL’s average AUC of 0.83 using the native score and 0.84 using SAS score. Using the T = 3.5 Å threshold, FragBag has an average AUC of 0.77, which is similar to STRUCTAL’s 0.77 using its native score and to CE’s 0.72 using SAS score. SSM outperforms FragBag at all three thresholds.

Table 1.

AUCs of ROC Curves Using Best-of-Six Gold Standard

| Method |

SAS Similarity Threshold (Å) |

Average value |

Rank |

Speed * |

||

| 2 |

3.5 |

5 |

||||

| SSM using SAS score | 0.94 | 0.90 | 0.89 | 0.910 | 1 | 13 [12] |

| Structal using SAS score | 0.90 | 0.81 | 0.84 | 0.850 | 2 | 39 [12] |

| Structal using native score | 0.87 | 0.77 | 0.83 | 0.823 | 3 | 39 [12] |

| CE using native score | 0.90 | 0.79 | 0.74 | 0.810 | 4 | 54 [12] |

| FragBag Cos distance (400,11) | 0.89 | 0.77 | 0.75 | 0.803 | 5 | Fast † |

| CE using SAS score | 0.84 | 0.72 | 0.75 | 0.770 | 6 | 54 [12] |

| FragBag histogram intersection (600,11) | 0.87 | 0.73 | 0.70 | 0.767 | 7 | Fast † |

| SGM | 0.86 | 0.71 | 0.68 | 0.750 | 8 | Fast † |

| FragBag Euclidean distance (40,6) | 0.86 | 0.71 | 0.64 | 0.737 | 9 | Fast † |

| Zotenko et al. (18) | 0.78 | 0.64 | 0.66 | 0.693 | 10 | Fast † |

| Sequence matching by BLAST e-value | 0.76 | 0.57 | 0.50 | 0.610 | 11 | Fast † |

| PRIDE | 0.72 | 0.54 | 0.51 | 0.590 | 12 | Fast † |

*Average CPU minutes per query.

†Essentially instantaneous after preprocessing (< 0.1 s).

Categories of CATH Proteins have BOW Descriptions that Are Different from Each Other In a Statistically Significant Way.

Next, we test statistically whether FragBag agrees with the CATH classification, at the Class Architecture (CA) and the Class, Architecture, and Topology (CAT) levels. In broad strokes, we expect FragBag representations of proteins in the same category to be more similar than those of proteins in different categories, and wish to verify that such similarity, if found, is not due to mere chance.

When running many statistical tests, as we do here (one for each pair of categories), the chances of getting at least one significant result is much higher than the chances of getting a significant result in a single test, even when there is no true underlying difference (the “multiple comparisons problem”). We control for this problem through the Bonferroni correction (29), and the false discovery rate (FDR) approach (30).

When using the Bonferroni correction, we adjust the required significance level of each test, so that the probability of falsely declaring at least one test as significant is the standard α = 0.05. Table 2 summarizes the results under the Bonferroni correction, across the 24 libraries. For example, there are 12 mainly-α CATH categories at the CAT level, and thus 12 × 11/2 = 66 category pairs; out of the 66 corresponding tests, 61 were significant at the adjusted significance level across all 24 libraries, hence the fraction 61/66 at the table’s first cell in the second row. The parenthesized figures in the table are the fraction of significant tests for the 400(11) library. The individual test results are available in Datasets S1 and S2.

Table 2.

Statistical analysis summary

| Analysis using Bonferroni correction *, † |

Analysis using FDR †, ‡ |

|||||

| Mainly α |

Mainly β |

Mixed α + β |

Mainly α |

Mainly β |

Mixed α + β |

|

| CA | 6/6 (6/6) | 31/36 (35/36) | 21/21 (21/21) | 6/6 (6/6) | 36/36 (36/36) | 21/21 (21/21) |

| CAT | 61/66 (65/66) | 76/78 (78/78) | 206/231 (225/231) | 65.5/66 (65/66) | 78/78 (78/78) | 230.2/231 (231/231) |

*Nonparenthesized values are the number of category pairs found different (at the Bonferroni-adjusted significant level) in all 24 libraries, divided by the total number of pairs; parenthesized values are the fraction of significant comparisons for the library of 400 fragments of length 11.

†In all cases, values close to 1 are desirable.

‡Nonparenthesized values are the fraction of comparisons declared significant in the FDR analysis, averaged across the 24 libraries; parenthesized figures are the fraction of the comparisons declared significant for the library of 400 fragments of length 11.

Using the FDR approach, we find which tests can be declared significant, while controlling the average fraction of the wrongly declared tests at some prechosen level; for details, see ref. 30. Table 2 lists the fraction of tests declared significant, averaged across the 24 libraries and under an FDR of 0.05; the parenthesized figures are the fraction of the tests declared significant for the 400(11) library.

The fractions reported in Table 2, all being very close to 1, strongly support the conclusion that the FragBag representation agrees with the CATH classification, both at the CA and the CAT level.

Comparison of FragBag Similarity Measure to rmsd on a Dataset of Structure Pairs Within Nuclear Magnetic Resonance (NMR) Ensembles.

Next, we study how well FragBag identifies similarity between structures that are only locally similar, i.e., have highly similar substructures that are connected differently. The ability to identify such local similarity may help in detecting similarity to a partially characterized structure, as needed in structure prediction. We consider pairs of structures within an NMR ensemble—a collection of structures that are consistent with the experimental constraints; these typically differ only at several flexible points along the backbone, and are thus locally similar. Our similarity criterion is defined by the threshold 0.35—the average FragBag cosine distance between structures with the same CAT classification (see Table 3). We use throughout this section the 400(11) library.

Table 3.

Average FragBag distances in datasets of varying structural similarity

| Dataset |

Histogram intersection distance* |

Euclidean (L2 norm) distance* |

Cosine distance* |

| Within NMR ensemble (rmsd ≤ 4 Å) | 0.25 ± 0.13 | 5.46 ± 2.46 | 0.17 ± 0.13 |

| Within NMR ensemble | 0.29 ± 0.15 | 5.96 ± 2.66 | 0.20 ± 0.16 |

| Same CATH classification | 0.52 ± 0.11 | 17.32 ± 8.33 | 0.34 ± 0.19 |

| Same CAT classification | 0.54 ± 0.11 | 21.14 ± 8.95 | 0.35 ± 0.19 |

| Same CA classification | 0.56 ± 0.15 | 23.75 ± 15.72 | 0.39 ± 0.24 |

| Same C classification | 0.56 ± 0.14 | 26.73 ± 16.34 | 0.46 ± 0.24 |

| Different C classification | 0.68 ± 0.18 | 30.56 ± 20.83 | 0.65 ± 0.27 |

*Using the library of 400 fragments of length 11.

We use the dataset of 230 NMR ensembles that was constructed in the PRIDE study (15). The set includes 54,465 pairs, 43,246 of which have rmsd ≤ 4 Å (1bqv, 1bmy, 1e01, and 1dlx were replaced by their newer versions). Fig. 3 shows the FragBag cosine distance vs. rmsd, and the marginal distributions of the two distances. The vast majority of pairs are identified as very similar by FragBag: 91% have cosine distance below 0.35, showing that FragBag indeed identifies similarity between locally similar structures. We see similar results using Histogram intersection and Euclidean distance (Fig. S1).

Fig. 3.

Cosine intersection distance vs. rmsd in structure pairs within NMR ensembles. The dataset has 230 NMR ensembles with 43,246 pairs having rmsd ≤ 4 Å (15). FragBag identifies the vast majority (91%) of the pairs in this set as very similar (cosine distance below 0.35—the average distance in pairs of the same CAT classification, marked in dashed pink).

For comparison, Table 3 lists the means and standard deviations of the FragBag distances between structure pairs at different levels of structural similarity. The most similar pairs are those within NMR ensembles: We consider all pairs and only those with rmsd ≤ 4 Å. We also consider pairs in the set of 2,928 CATH domains that have the same CATH, CAT, CA, and C classification, as well as all pairs. As expected, the average distance grows as the sets become more structurally diverse, under all three distances.

Discussion

A Fast Filter that Performs On a Par with Structural Alignment Methods.

FragBag can quickly identify structural neighbor candidates for a structure query, and performs as well as some highly trusted, computationally expensive structural alignment methods. Our results with FragBag’s 400(11) library are as accurate as CE’s, and almost as accurate as STRUCTAL’s. This is impressive, as CE and STRUCTAL are among the most accurate structural alignment methods (10). As expected, structural neighbors are generally identified best by structural aligners, less well by filters, and least well by sequence alignment. Our results are robust—we see similar ranking of methods using different definitions for structural neighbors of a protein. An attractive feature of abstract representations of protein structure such as FragBag (and other filter methods) is that one can store the vectors representing all PDB proteins in an inverted index—a data structure designed for fast retrieval of neighbors.

Evaluation Protocol.

Retrieving structural neighbors of a query protein from the entire PDB is a challenge. We cannot deduce the structural neighbors solely from SCOP or CATH, because crossfold similarities—proteins that are geometrically similar, yet classified differently—are very common (10, 31). Kihara and Skolnick (31) noted that crossfold similarities among small proteins (< 100 residues), are abundant even at CATH’s C level. Crossfold similarities are particularly important to identify, when predicting structure and function (1, 6). Recent Critical Assessment of Techniques for Protein Structure Prediction (CASP) experiments show that the most successful structure prediction methods construct their predictions from substructures that are not, in general, from proteins classified in the same fold [e.g. (3, 32, 33)]. Friedberg and Godzik (34) showed that crossfold similarities correlate well with the functional similarity of proteins populating the folds, and Petrey and Honig (6) showed examples of functional similarity among differently classified proteins. Nevertheless, proteins classified in the same CATH category (at the CA or CAT levels) are truly similar, and we expect their FragBag representations to be similar as well. Because there are many CA and CAT categories, each populated with many proteins, we used statistical theory to test and confirm this.

Any gold standard must meet the challenge: Because a filter method needs to identify structural neighbors of a query, the gold standard must be all identified neighbors. Here, we find these neighbors using the expensive computation of a best-of-six structural aligner. Namely, we identify a structure as a neighbor if any of the six methods finds in both a sizable substructure that can be superimposed with a low rmsd. Such a neighbor is selected regardless of its CATH classification, and could well belong to a category other than that of the query protein. Had we relied on a classification, similar structures would have been marked as nonneighbors, and the ROC curve analysis would have effectively penalized filter methods that correctly identify them.

Because structural similarity that is due to sequence similarity is easy to identify, we use datasets of nonredundant sequences. This ensures that we have eliminated trivial pairs in our evaluation protocol. Note that when the structural neighbors are defined with the T = 2 Å, 3.5 Å thresholds, sequence alignment does better than random (AUC > 0.5); indeed, when there are only few structural neighbors (e.g., only the query), even a trivial sequence alignment method will perform well, because it ranks the query as most similar to itself. This phenomenon will have a greater impact on the average AUC when the number of structural neighbors is small (lower T). Thus, the average AUC of the sequence alignment method acts as a lower bound, indicating the difficulty of the task.

Although not the main focus of this study, our results provide another evaluation of the performance of STRUCTAL, CE, and SSM, and show that SSM is the top performer. SSM compares structures in two stages. (i) A fast estimation of structural similarity by matching the SSE graphs of the structures. This step calculates two estimates of the percent SSE match, and the user can specify their allowed maximal values; the SSM server does not provide a combined value of these estimates that can be used to rank structure pairs. (ii) An expensive and accurate alignment of the Cαs of the two structures. Here, we use the SAS of the alignments found by SSM after the second stage.

Searching with Partially Defined Queries for Protein Structure Prediction.

Importantly, FragBag can search the entire PDB for neighbors of a query structure that is only partially characterized. Such a search is useful for structure prediction, as prediction methods often predict only the structure of parts of a protein, and finding a composition of these parts in the PDB may hint at how these parts should be combined into a complete structure. In FragBag, the missing information has a minor impact. The union of the bags-of-fragments of the parts differs from the true bag-of-fragments only by the few fragments in the connecting regions. Similarly, two structures that are flexible variants (i.e., differ only at a hinge point) will have similar FragBag representations.

Future Directions.

We hope to improve FragBag using a similarity measure that weights the fragments differently, and possibly ignores some; BOWs weighting schemes were successfully used in other areas of Computer Science. Currently, each representation is based on one library, and all its fragments are weighted equally. Once we have a weighting scheme, we can combine libraries and trust the weights to select all significant fragments.

We also plan to construct a FragBag-based inverted index for the entire PDB; as noted above, this index will allow quickly identifying small candidate sets of structural neighbors of a protein. The candidate sets will also include structures that are flexible variants of the query, potentially revealing new connections in protein structure space. Finally, this index may be used to answer partially characterized queries, to the benefit of the structure prediction community.

Methods

We consider 24 libraries with 20–600 fragments of 5–12 residues, constructed in a previous study (35). There, we clustered the fragments of the Cα traces of 200 accurately determined structures, and formed a library by taking a representative from each cluster.

ROC Curve Analysis with Structural Alignments Gold Standard.

We use a set of 2,928 sequence-diverse CATH v.2.4 domains and their all-against-all structural alignments; the set was constructed for a previous comparison study of structural aligners (10). Two 7-residue long structures (1pspA1, 1pspB1) were removed because they are shorter than some fragments. All structures were structurally aligned to all others by six alignment methods (SSAP, STRUCTAL, DALI, LSQMAN, CE, and SSM) and their SAS scores were recorded, where SAS = 100 × rmsd/(alignment length). Our gold standard is based on the best alignment found by these six methods in terms of the SAS score. The sequences of every pair of structures in this set differ significantly (FASTA E-value > 10-4).

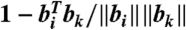

A FragBag description of a protein is a row vector; its length, N, is the size of the library used. The vector describing the ith protein is bi = (bi(1),bi(2),…,bi(N)), where bi(j) is the number of times fragment j is the best local approximation of a segment in the ith protein.

We consider three distance metrics between two vectors, bi and bk: (i) cosine distance,  , (ii) histogram intersection distance,

, (ii) histogram intersection distance,  , where

, where  , and (iii) Euclidean (L2) distance, ‖bi - bk‖.

, and (iii) Euclidean (L2) distance, ‖bi - bk‖.

Statistical Analysis.

We now describe what data were used in the statistical analysis, how these data are summarized in matrix form, and the details of the statistical analysis.

Raw Data.

We use the 8,871 domains in the S35 family level in CATH 3.2.0. Because the classification at the C level is based on secondary structure, we focus on the CA and CAT levels, and run the tests separately on different C classes. To improve the statistical power of the tests, we use only categories with at least 30 structures. When partitioning the dataset to categories at the CA level, there are 4 categories (with at least 30 structures) in the mainly-α class (totaling 2,077 structures out of 2,078); 9 in the mainly-β class (1,968 out of 2,062); and 7 in the mixed α + β class (4,507 out of 4,558). There was only one category in the few-secondary-structure class, so this class was omitted. When partitioning at the CAT level, there are 12 categories in the mainly-α class (totaling 1,013 structures); 13 in the mainly-β class (1,396 structures); and 22 in the mixed α + β class (2,681 structures).

Data in Matrix Form.

Consider a library of N fragments, and, say, the CA-level classification of the M = 1968 mainly-β proteins into Q = 9 categories. The FragBag representations of these M proteins is initially summarized in an M × N matrix B, whose (i,j)-th entry is bi(j). The matrix B is partitioned rowwise into Q blocks corresponding to the Q categories, and we denote by Mq the number of rows of the qth block. When considering CATH’s CAT level, mainly-α proteins, or mixed α + β proteins, M, Q, and B, as well as the partition of B, change accordingly.

Omnibus Test.

Following the usual statistical practice, we first run a single omnibus test (29) to check whether there is at least one pair of categories whose proteins’ FragBag representations are different from each other in a statistically significant way; only after such a difference is found, we compare all possible pairs of categories (post hoc analysis). The data is multivariate, as each FragBag vector consists of N observations, yet it certainly cannot be assumed to be normally distributed. Thus, we use a nonparametric permutation test, adapted from (36).

We now construct a statistic w that captures the overall dissimilarity between vectors belonging to different categories; large values of w support rejecting the null hypothesis, according to which the partition into blocks carries no information with respect to the classification. We first standardize B’s columns by dividing each column by its standard deviation (36). Let Bq be the Mq × N submatrix of (the standardized) B, constituting the qth block, and let  be the N-vector whose entries are the means of the columns of Bq. For two distinct blocks, q and r, we define

be the N-vector whose entries are the means of the columns of Bq. For two distinct blocks, q and r, we define  , where the maximum is taken over the N differences (in absolute values) between the entries of the two vectors. The omnibus test statistic is

, where the maximum is taken over the N differences (in absolute values) between the entries of the two vectors. The omnibus test statistic is  .

.

Being a permutation test, the omnibus test’s p-value is P(W≥w), where W is a similarly computed score under a random permutation of B’s rows. Because the number of permutations is too large to enumerate, we resort to estimating the p-value in a Monte Carlo fashion, by drawing 1000 random permutations of B’s rows, and observing the proportion of the permutations achieving a statistic higher than w. The omnibus test results were all significant, for comparisons both at the CA and CAT levels, for all 24 libraries, and for each of the three CATH classes (p < 0.001 in all cases).

Post Hoc Analysis, Bonferroni Correction, and FDR.

Once the omnibus test results were found significant, we test the data for a more stringent alternative hypothesis, according to which any two blocks are different from each other (rather than testing for the existence of at least one pair of different blocks, as the omnibus test does). To do so, we run the above test separately for each of the K = Q(Q - 1)/2 pairs of blocks. When comparing blocks q and r, the matrix B is of dimension (Mq + Mr) × N, and as only two blocks are considered, this comparison’s statistic reduces to w = Δqr. The result is a collection of K p-values, corresponding to the K pairwise comparisons. When using the Bonferroni correction, we declare as significant only the comparisons in which the p-value is below 0.05/K. When using the FDR approach, we follow (30).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments.

We thank our anonymous reviewers for their helpful comments. This research was supported by the Marie Curie IRG Grant 224774.

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/cgi/content/full/0914097107/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Kolodny R, Petrey D, Honig B. Protein structure comparison: Implications for the nature of “fold space,” and structure and function prediction. Curr Opin Struct Biol. 2006;16(3):393–398. doi: 10.1016/j.sbi.2006.04.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Watson JD, Laskowski RA, Thornton JM. Predicting protein function from sequence and structural data. Curr Opin Struct Biol. 2005;15(3):275–284. doi: 10.1016/j.sbi.2005.04.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zhang Y. Progress and challenges in protein structure prediction. Curr Opin Struct Biol. 2008;18(3):342–348. doi: 10.1016/j.sbi.2008.02.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Murzin AG, Brenner SE, Hubbard T, Chothia C. SCOP: A structural classification of proteins database for the investigation of sequences and structures. J Mol Biol. 1995;247(4):536–540. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1995.0159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pearl FM, et al. The CATH database: An extended protein family resource for structural and functional genomics. Nucleic Acids Res. 2003;31(1):452–455. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkg062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Petrey D, Honig B. Is protein classification necessary? Toward alternative approaches to function annotation. Curr Opin Struct Biol. 2009;19(3):363–368. doi: 10.1016/j.sbi.2009.02.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Subbiah S, Laurents DV, Levitt M. Structural similarity of DNA-binding domains of bacteriophage repressors and the globin core. Curr Biol. 1993;3(3):141–148. doi: 10.1016/0960-9822(93)90255-m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Shindyalov IN, Bourne PE. Protein structure alignment by incremental combinatorial extension (CE) of the optimal path. Protein Eng. 1998;11(9):739–747. doi: 10.1093/protein/11.9.739. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Krissinel E, Henrick K. Secondary-structure matching (SSM), a new tool for fast protein structure alignment in three dimensions. Acta Crystallogr D. 2004;60:2256–2268. doi: 10.1107/S0907444904026460. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kolodny R, Koehl P, Levitt M. Comprehensive Evaluation of Protein Structure Alignment Methods: Scoring by Geometric Measures. J Mol Biol. 2005;346(4):1173–1188. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2004.12.032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Li Z, Ye Y, Godzik A. Flexible structural neighborhood—a database of protein structural similarities and alignments. Nucleic Acids Res. 2006;34:D277–D280. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkj124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kosloff M, Kolodny R. Sequence-similar, structure-dissimilar protein pairs in the PDB. Proteins. 2008;71(2):891–902. doi: 10.1002/prot.21770. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Aung Z, Tan KL. Rapid retrieval of protein structures from databases. Drug Discov Today. 2007;12(17–18):732–739. doi: 10.1016/j.drudis.2007.07.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Aung Z, Tan KL. Rapid 3D protein structure database searching using information retrieval techniques. Bioinformatics. 2004;20(7):1045–1052. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bth036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Carugo O, Pongor S. Protein fold similarity estimated by a probabilistic approach based on C(alpha)-C(alpha) distance comparison. J Mol Biol. 2002;315(4):887–898. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.2001.5250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Choi IG, Kwon J, Kim SH. Local feature frequency profile: A method to measure structural similarity in proteins. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2004;101(11):3797–3802. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0308656100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rögen P, Fain B. Automatic classification of protein structure by using Gauss integrals. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2003;100(1):119–124. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2636460100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zotenko E, O’Leary DP, Przytycka TM. Secondary structure spatial conformation footprint: A novel method for fast protein structure comparison and classification. BMC Struct Biol. 2006;6:12. doi: 10.1186/1472-6807-6-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Friedberg I, et al. Using an alignment of fragment strings for comparing protein structures. Bioinformatics. 2007;23(2):e219–224. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btl310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Tung CH, Huang JW, Yang JM. Kappa-alpha plot derived structural alphabet and BLOSUM-like substitution matrix for rapid search of protein structure database. Genome Biol. 2007;8(3):R31. doi: 10.1186/gb-2007-8-3-r31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Manning CD, Raghavan P, Schütze H. Introduction to Information Retrieval. Cambridge: Cambridge Univ Press; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Puzicha J, Buhmann JM, Rubner Y, Tomasi C. Empirical evaluation of dissimilarity measures for color and texture; The Proceedings of the Seventh IEEE International Conference on Computer Vision, 1999; 1999. p. 1165. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Fei-Fei L, Pietro P. A Bayesian Hierarchical Model for Learning Natural Scene Categories; Proceedings of the 2005 IEEE Computer Society Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR’05) - Volume 2 - Volume 02; IEEE Computer Society; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Melvin I, et al. SVM-Fold: A tool for discriminative multi-class protein fold and superfamily recognition. BMC Bioinformatics. 2007;8(Suppl 4):S2. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-8-S4-S2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Tatusova TA, Madden TL. BLAST 2 Sequences, a new tool for comparing protein and nucleotide sequences. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 1999;174(2):247–250. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.1999.tb13575.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Taylor WR, Orengo CA. Protein structure alignment. J Mol Biol. 1989;208(1):1–22. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(89)90084-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Holm L, Sander C. Protein structure comparison by alignment of distance matrices. J Mol Biol. 1993;233(1):123–138. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1993.1489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kleywegt GJ. Use of non-crystallographic symmetry in protein structure refinement. Acta Crystallogr., Sect. D: Biol. Crystallogr. 1996;52:842–857. doi: 10.1107/S0907444995016477. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Miller RGJ. Simultaneous Statistical Inference. 2nd edition. New York: Springer; 1981. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Benjamini Y, Hochberg Y. Controlling the false discovery rate: A practical and powerful approach to multiple testing. J R Statist Soc B. 1995;57(1):289–300. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kihara D, Skolnick J. The PDB is a Covering Set of Small Protein Structures. J Mol Biol. 2003;334(4):793–802. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2003.10.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Moult J, et al. Critical assessment of methods of protein structure prediction-Round VII. Proteins. 2007;69(Suppl 8):3–9. doi: 10.1002/prot.21767. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Zhang Y, Arakaki AK, Skolnick J. TASSER: An automated method for the prediction of protein tertiary structures in CASP6. Proteins: Structure, Function, and Bioinformatics. 2005;9999(9999) doi: 10.1002/prot.20724. NA. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Friedberg I, Godzik A. Fragnostic: Walking through protein structure space. Nucleic Acids Res. 2005;33(suppl 2):W249–251. doi: 10.1093/nar/gki363. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kolodny R, Koehl P, Guibas L, Levitt M. Small libraries of protein fragments model native protein structures accurately. J Mol Biol. 2002;323(2):297–307. doi: 10.1016/s0022-2836(02)00942-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Good P. Permutation Tests. 2nd ed. New York: Springer; 2000. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.