Abstract

The RNA-dependent RNA polymerase L protein of vesicular stomatitis virus, a prototype of nonsegmented negative-strand (NNS) RNA viruses, forms a covalent complex with a 5′-phosphorylated viral mRNA-start sequence (L-pRNA), a putative intermediate in the unconventional mRNA capping reaction catalyzed by the RNA:GDP polyribonucleotidyltransferase (PRNTase) activity. Here, we directly demonstrate that the purified L-pRNA complex transfers pRNA to GDP to produce the capped RNA (Gpp-pRNA), indicating that the complex is a bona fide intermediate in the RNA transfer reaction. To locate the active site of the PRNTase domain in the L protein, the covalent RNA attachment site was mapped. We found that the 5′-monophosphate end of the RNA is linked to the histidine residue at position 1,227 (H1227) of the L protein through a phosphoamide bond. Interestingly, H1227 is part of the histidine-arginine (HR) motif, which is conserved within the L proteins of the NNS RNA viruses including rabies, measles, Ebola, and Borna disease viruses. Mutagenesis analyses revealed that the HR motif is required for the PRNTase activity at the step of the enzyme-pRNA intermediate formation. Thus, our findings suggest that an ancient NNS RNA viral polymerase has acquired the PRNTase domain independently of the eukaryotic mRNA capping enzyme during evolution and PRNTase becomes a rational target for designing antiviral agents.

Keywords: nonsegmented negative-strand RNA virus, polyribonucleotidyltransferase, RNA-dependent RNA polymerase, L protein, mRNA modification

A structural hallmark of eukaryotic mRNA is the presence of the 5′-terminal cap structure [m7G(5′)ppp(5′)N-], in which 7-methylguanosine (m7G) is linked to the first nucleoside of mRNA through the inverted 5′-5′ triphosphate bridge. The cap structure is generated by a series of enzymatic reactions at an early stage of mRNA biogenesis and participates as a pivotal signal in various aspects of mRNA metabolism including translation and stability (1–3). In the conventional mRNA capping reaction for all known eukaryotes, some DNA viruses (e.g., vaccinia virus), and double-strand RNA viruses (e.g., reovirus), the cap core structure (Gp-ppN) is synthesized by the mRNA capping enzyme composed of RNA 5′-triphosphatase (RTPase) and GTP:RNA guanylyltransferase (GTase) (2, 3), as follows:

|

[1] |

|

[2] |

| [3] |

First, the γ-phosphate of 5′-triphosphorylated (ppp-) pre-mRNA is removed by RTPase to produce the 5′-diphosphorylated (pp-) RNA, which is in turn used as a guanylyl acceptor. GTase subsequently transfers a GMP moiety of GTP to the diphosphate end of pre-mRNA through a covalent enzyme-GMP intermediate (E-pG) to produce a Gp-ppN capped RNA.

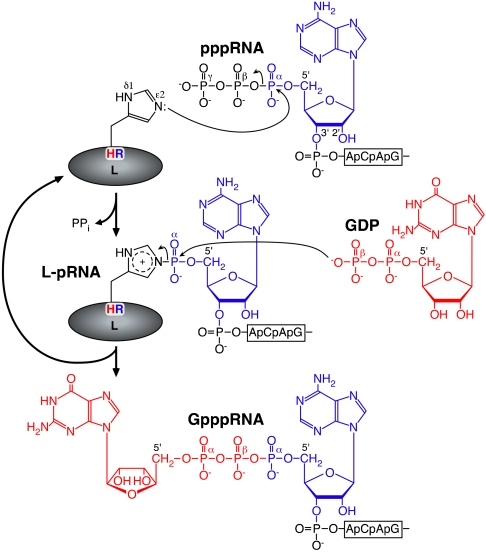

In direct contrast, we have recently shown that the multifunctional RNA-dependent RNA polymerase (RdRp) L protein (2,109 amino acids) of vesicular stomatitis virus (VSV), a prototype nonsegmented negative-strand (NNS) RNA virus belonging to the genus Vesiculovirus of the family Rhabdoviridae in the order Mononegavirales, carries out an unconventional mRNA capping mechanism that involves stepwise action of guanosine 5′-triphosphatase (GTPase) followed by RNA:GDP polyribonucleotidyltransferase (PRNTase) (4, 5), as proposed below:

| [4] |

|

[5] |

| [6] |

First, the GTPase activity of the VSV L protein hydrolyzes GTP to produce GDP, an RNA acceptor. Then, the PRNTase activity of the L protein specifically transfers a 5′-monophosphorylated (p-) RNA moiety of pppRNA with the conserved VSV mRNA-start sequence (AACAG) to GDP to yield a Gpp-pA capped RNA (4). Because the VSV L protein was found to form a covalent complex with the 5′-phosphate end of the RNA (L-pRNA complex) (4), the PRNTase domain in the VSV L protein was suggested to catalyze the formation of a phosphoanhydride bond between the β-phosphate of GDP and the 5′-terminal α-phosphate of the RNA through a putative covalent enzyme-pRNA intermediate (L-pRNA complex). However, no direct evidence was available that the covalent L-pRNA complex has an ability to transfer pRNA to GDP, and the identification of the amino acid residue within the active site of the PRNTase domain that is covalently linked to the RNA moiety remained unknown.

Here, we demonstrate that the purified L-pRNA complex indeed catalyzes the transfer of pRNA to GDP to generate the capped RNA. Furthermore, by biochemical and mass spectrometric analyses, we revealed that the histidine residue at position 1,227 (H1227) in the conserved HR motif of the VSV L protein is 'covalently linked to the 5′-monophosphate end of the RNA through a phosphoamide bond and, thus, is the active site amino acid of the PRNTase domain. By mutational analyses, we showed that the HR motif is essential for the PRNTase activity of the VSV L protein. Therefore, our findings provide direct evidence that a covalent RNA transfer enzyme is required for viral mRNA capping.

Results and Discussion

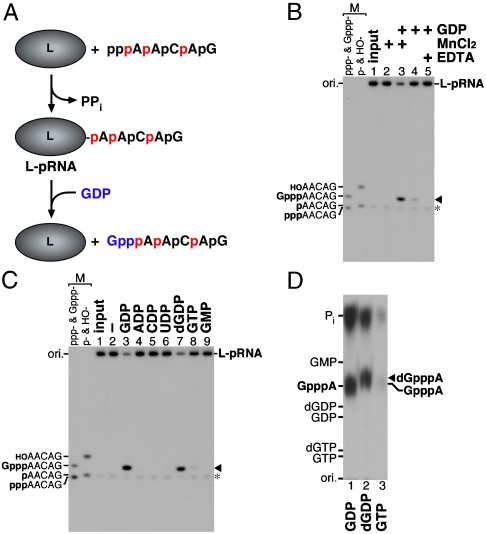

Demonstration of the RNA Transfer to GDP from the Native L-pRNA Complex.

To demonstrate the polyribonucleotidyl transfer reaction from the covalent L-pRNA complex (L-pAACAG, the putative enzyme-pRNA intermediate) to GDP (RNA acceptor), we purified the L-pRNA complex devoid of excess pppRNA substrate pppAACAG by chromatography using phosphocellulose resin (Fig. S1) and subjected the complex to RNA transfer reactions with GDP in the presence of a divalent metal ion (Mn2+), as depicted in Fig. 1A. The resulting capped RNA (Gpp-pAACAG) released from the L-pRNA complex was analyzed by urea-20% PAGE followed by autoradiography. As shown in Fig. 1B (lane 1), the input L-pRNA complex was detected at the origin of the gel. When the complex was incubated in the absence of GDP, the RNA covalently linked to the L protein was not released from the complex (lane 2). In contrast, when the complex was incubated in the presence of GDP, 56% of RNA (marked by the arrowhead) was released from the L-pRNA complex within 1 min (lane 3) and was identified as the capped RNA (Gpp-pAACAG) (see Fig. S2). In the absence of the divalent metal ion, 15% of RNA was released as the capped RNA from the L-pRNA complex with GDP (lane 4), but the RNA release with GDP was completely inhibited by EDTA, a divalent metal chelator (lane 5), suggesting that the RNA releasing activity is divalent metal-dependent and some Mn2+ ion presumably copurified with the L-pRNA complex. These results establish that the L-pRNA complex is a bona fide intermediate in the metal-dependent polyribonucleotidyl transfer reaction to produce the capped RNA. It should also be noted that the L-pRNA complex was copurified with a small amount of a free RNA (marked by the asterisk in Fig. 1B), which was identified as pAACAG (Fig. S1). However, the presence of the free pRNA in the L-pRNA fraction, in fact, did not matter, because it is completely inert as a substrate for the PRNTase reaction (4). To investigate the RNA acceptor specificity of VSV PRNTase, the purified L-pRNA complex was incubated with various nucleotides (Fig. 1C). No detectable amount of the RNA was released from the complex when incubated with ADP, CDP, or UDP (lanes 4–6), whereas the RNA was efficiently released from the complex with GDP (lane 3) as well as dGDP (lane 7). The RNA releasing activity of dGDP was 80% of the activity of GDP. A weak RNA releasing activity (14%) was noted for GTP (lane 8), whereas GMP had little activity (lane 9). The RNAs released with GDP (lane 3), dGDP (lane 7), and GTP (lane 8) were purified from the urea-gel, and digested with nuclease P1 and calf intestine alkaline phosphatase (CIAP). The cap structures resistant to nuclease P1 and CIAP were analyzed by polyethyleneimine (PEI)-cellulose TLC followed by autoradiography (Fig. 1D). The putative 2′-deoxyguanosine(5′)triphospho(5′)adenosine (dGpppA) cap structure (lane 2) was found to migrate slightly faster than the authentic GpppA cap structure (lane 1) on the PEI-cellulose TLC plate. The digest of the RNA released with GTP contained the GpppA cap structure (lane 3). However, efficiency of the formation of GpppA with GTP is 7-fold lower than that with GDP, suggesting that production of GDP from GTP with GTPase is a rate-limiting step of this reaction. Thus, it seems that the PRNTase domain of the VSV L protein specifically recognizes the guanine base and β-phosphate of GDP, and the 2′-hydroxyl group on ribose does not appear to contribute to RNA acceptor recognition with the PRNTase domain. The formation of dGpppA was not unexpected, because Schubert and Lazzarini (6) reported many years ago that dGTP could replace GTP in in vitro VSV mRNA synthesis with the formation of capped mRNA with dGpppA at the 5′-terminus. This property of the VSV L protein is in contrast to the eukaryotic GTase, which forms a putative enzyme-dGMP complex to a lesser extent (< 10% of the enzyme-GMP complex formation activity with GTP) (7), yet fails to transfer the dGMP moiety to ppRNA (8). Thus, it seems that VSV PRNTase and eukaryotic GTase have evolved independently during evolution, performing the essential capping of mRNAs by widely disparate mechanisms. It is interesting to note that dGTP is used as a guanylyl donor for RNA capping by vaccinia viral GTase (9).

Fig. 1.

RNA transfer from the purified L-pRNA complex to GDP. (A) The VSV L protein was incubated with pppAACAG labeled with [α-32P]AMP (32P shown in red) to generate the covalent L-pRNA complex. The purified L-pRNA complex was incubated with GDP (blue) to examine whether pRNA linked to the L protein is transferred to GDP to form the capped RNA. (B) The purified L-pRNA complex was incubated with GDP in the presence or absence of MnCl2 or EDTA, as indicated. The reaction mixtures were analyzed by urea-20% PAGE followed by autoradiography. Marker (M) lanes indicate the AACAG RNAs with different 5′-ends (ppp-, triphosphorylated; Gppp-, capped; p-, monophosphorylated; HO-, hydroxyl). Lane 1 indicates the input L-pRNA complex. The arrowhead and asterisk indicate the capped RNA (Gpp-pAACAG) and free pRNA, respectively. (C and D) The purified L-pRNA complex was incubated with the indicated nucleotide in the presence of MnCl2. The reaction mixtures were analyzed by urea-20% PAGE (C). RNAs released with GDP (lane 3), dGDP (lane 7), and GTP (lane 8) (indicated by the arrowhead) were purified from the gel and digested with nuclease P1 and CIAP. The digests were analyzed along with marker compounds by PEI-cellulose TLC (D). The positions of standard marker compounds, visualized under UV light at wavelength of 254 nm, are shown on the left. The position of the putative 2′-deoxyguanosine(5′)triphospho(5′)adenosine (dGpppA) cap structure is shown by the arrowhead.

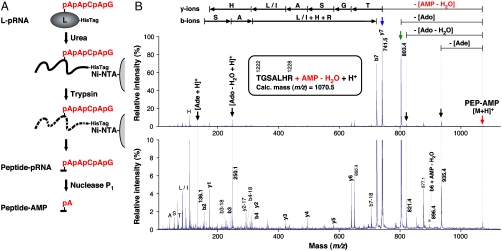

Localization of the Amino Acid Residue Covalently Linked to the RNA in the L Protein.

Our demonstration that the L-pRNA complex is the functional intermediate in the RNA transfer reaction prompted us to locate the covalent RNA attachment site within the active site of the PRNTase domain in the L protein. The His-tagged L-pRNA complex was purified with the nickel-nitrilotriacetic acid (Ni-NTA) agarose affinity resin under denaturing conditions and digested with trypsin while bound to the resin (Fig. 2A). The peptide-pRNA complex liberated from the resin was purified by urea-20% PAGE followed by chromatography using the DEAE Sephacel anion-exchange resin and characterized by enzymatic digestions (see Fig. S3A–E). Due to the difficulty in detecting highly acidic peptides, such as multiply phosphorylated peptides, by MALDI-TOF MS in a positive-ion mode (10), we removed four phosphate groups from the peptide-pRNA complex by digestion of the RNA chain with nuclease P1 (see Fig. S3C). The resulting peptide-AMP complex was purified using the Q-Sepharose resin followed by C18 ZipTip (see Fig. S3A and F). As shown in Fig. S3G, the AMP moiety appears to be attached to a basic amino acid in the peptide via an acid-labile phosphoamide bond. The purified peptide-AMP complex was analyzed by MALDI-TOF MS (see Fig. S4), and its singly charged ion ([M + H]+) at m/z 1070.6 was subjected to MS/MS analysis to deduce its amino acid sequence and the AMP attachment site in the peptide (Fig. 2B). The sequence of the peptide ion was found to be TGSA(L/I)HR, corresponding to residues 1,222–1,228 (TGSALHR) of the VSV L protein. However, because we detected only one signal of a putative peptide fragment ion linked to AMP [b6 (TGSALH) + AMP - H2O, observed mass = 896.4, calculated mass = 896.3; marked by the asterisk in Fig. 2B], probably due to the instability of the phosphoamide bond (11), the amino acid residue linked to AMP could not be precisely mapped. Even though the peptide contains four amino acid residues (T1222 , S1224, H1227, and R1228) that can serve as phosphate acceptors, we propose that the H1227 residue is covalently linked to AMP (pRNA), because the chemical nature (acid- and neutral hydroxylamine-lability and alkali-stability) of the covalent linkage (4) (Fig. S3G) is similar to that of phosphoamide bonds formed on basic amino acids (especially histidine), but not to that of phosphoester bonds formed on hydroxyamino acids (11). Furthermore, we confirmed that the R1228 residue could be enzymatically removed from the peptide-pRNA complex (Fig. S3E).

Fig. 2.

Localization of the covalent RNA attachment site in the L protein. (A) The His-tagged L-pRNA complex (pRNA shown in red) was denatured with urea and purified with Ni-NTA agarose. The denatured complex on the resin was digested with trypsin. The resulting peptide-pRNA complex was digested with nuclease P1 to generate the peptide-AMP complex. (B) The purified peptide-AMP complex was analyzed by MALDI-TOF MS (see Fig. S4) and its singly charged ion at m/z 1070.6 was subjected to MS/MS analysis. MS/MS spectra are given as differently expanded intensity axes (Upper and Lower panels). The parent ion ([M + H]+) is shown by the red arrow. Other vertical arrows indicate putative fragment ions that presumably lost adenine (Ade) (C5H5N5, 135.1 Da), anhydro-adenosine (Ado) (C10H11N5O3, 249.1 Da), Ado (C10H13N5O4, 267.1 Da), and anhydro-AMP (C10H12N5O6P1, 329.1 Da) from the parent ion and protonated Ade and anhydro-Ado ions ([Ade + H]+ and [Ado - H2O + H]+, respectively). The asterisk indicates the putative b6 ion linked to AMP (b6 + AMP - H2O). Deduced peptide fragment ions (b- and y-ions) lacking the AMP moiety and immonium ions are indicated above the signals. The horizontal arrows indicate an amino acid sequence [TGSA(L/I)HR] elucidated from the b- and y-ion series. The sequence corresponds to residues 1,222 to 1,228 of the VSV L protein. The calc. monoisotopic mass of the peptide-AMP complex ion is shown.

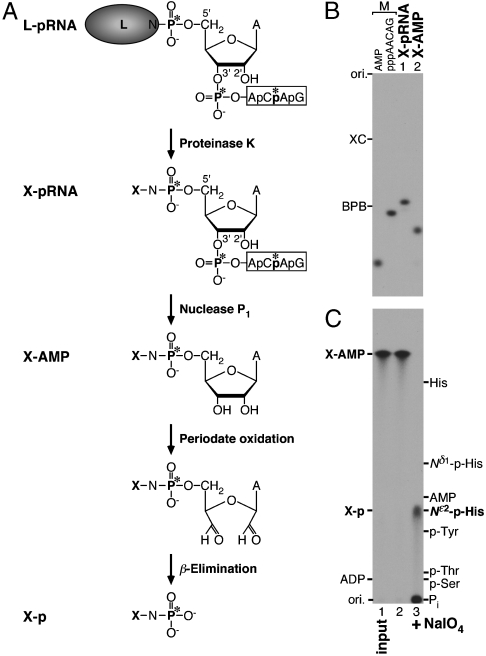

To directly demonstrate that a histidine residue is linked to the RNA, we identified a phosphoamino acid released from the L-pRNA complex following the scheme shown in Fig. 3A. First, the radioactive L-pRNA complex ( , asterisks indicate 32P) was digested with proteinase K to yield a single amino acid–pRNA complex (

, asterisks indicate 32P) was digested with proteinase K to yield a single amino acid–pRNA complex ( , X indicates an unknown amino acid). The purified X-pRNA complex (Fig. 3B, lane 1) was digested with nuclease P1 to generate an X-AMP complex (

, X indicates an unknown amino acid). The purified X-pRNA complex (Fig. 3B, lane 1) was digested with nuclease P1 to generate an X-AMP complex ( ). The purified X-AMP complex (Fig. 3B, lane 2) was subjected to periodate oxidation followed by alkaline β-elimination (12) to remove the adenosine moiety from the compound. The resulting phosphoamino acid (

). The purified X-AMP complex (Fig. 3B, lane 2) was subjected to periodate oxidation followed by alkaline β-elimination (12) to remove the adenosine moiety from the compound. The resulting phosphoamino acid ( ) was analyzed by reverse phase silica gel TLC with marker compounds including two isomers of phosphohistidine [Nδ1-phosphohistidine (1-phosphohistidine) and Nε2-phosphohistidine (3-phosphohistidine)] (Fig. 3C). When the X-AMP complex was incubated without sodium periodate, the compound was stable to the subsequent alkali treatment (lane 2). Treatment of the X-AMP containing 2′,3′-cis-diol on the ribose ring with sodium periodate followed by base elimination generated a 32P-labeled product comigrating with Nε2-phosphohistidine, but not with Nδ1-phosphohistidine, phosphoserine, phosphothreonine, phosphotyrosine, or AMP (lane 3), though a fraction of the product appeared to be further degraded into

) was analyzed by reverse phase silica gel TLC with marker compounds including two isomers of phosphohistidine [Nδ1-phosphohistidine (1-phosphohistidine) and Nε2-phosphohistidine (3-phosphohistidine)] (Fig. 3C). When the X-AMP complex was incubated without sodium periodate, the compound was stable to the subsequent alkali treatment (lane 2). Treatment of the X-AMP containing 2′,3′-cis-diol on the ribose ring with sodium periodate followed by base elimination generated a 32P-labeled product comigrating with Nε2-phosphohistidine, but not with Nδ1-phosphohistidine, phosphoserine, phosphothreonine, phosphotyrosine, or AMP (lane 3), though a fraction of the product appeared to be further degraded into  by hydrolysis. It is important to note that phosphoarginine was reported to migrate between phosphotyrosine and phosphothreonine under the same conditions (13). Thus, these results establish that histidine is the active site amino acid residue that is linked to the RNA through a phosphoamide bond.

by hydrolysis. It is important to note that phosphoarginine was reported to migrate between phosphotyrosine and phosphothreonine under the same conditions (13). Thus, these results establish that histidine is the active site amino acid residue that is linked to the RNA through a phosphoamide bond.

Fig. 3.

Analysis of the polyribonucleotidylated amino acid in the L protein. (A) The L-pRNA complex (asterisks indicate 32P) was digested with proteinase K to obtain a single amino acid (X)-pRNA complex. After removal of the RNA chain from the X-pRNA complex by nuclease P1 digestion, the resulting X-AMP complex was subjected to periodate oxidation followed by β-elimination to generate phosphoamino acid (X-p). (B) The X-pRNA and X-AMP complexes were analyzed by urea-20% PAGE followed by autoradiography. (C) The X-AMP complex was incubated with (lane 3) or without (lane 2) sodium periodate in an alkaline solution (pH 10.5) at room temperature. After adding an excess amount of ethylene glycol, the reaction mixtures were incubated at 50 °C. The reaction mixtures were analyzed by reverse phase silica gel TLC with marker compounds including phosphoserine (p-Ser), phosphothreonine (p-Thr), phosphotyrosine (p-Tyr), Nδ1-phosphohistidine (Nδ1-p-His), Nε2-phosphohistidine (Nε2-p-His), histidine (His), AMP, and ADP. Lane 1 indicates the input X-AMP complex.

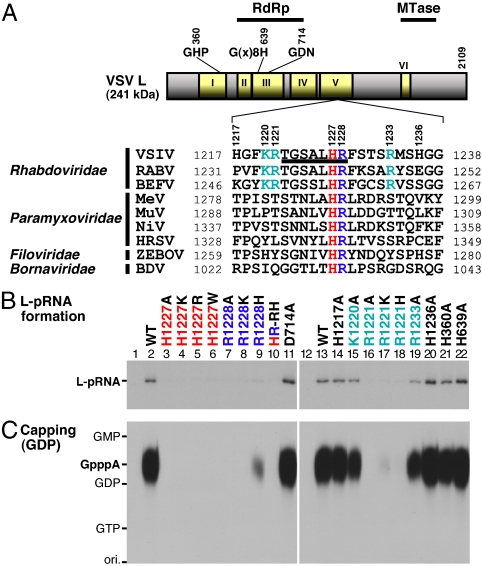

The HR Motif in the L Protein is Required for the PRNTase Activity at the Step of the Enzyme-pRNA Intermediate Formation.

The L proteins of the NNS RNA viruses contain six conserved amino acid sequence blocks I–VI (14) (Fig. 4A). The N-terminal part of the L protein including the block III and the C-terminal part including the block VI are suggested to fold into the putative RdRp and cap methyltransferase (MTase) domains, respectively (14–18). The block III contains a putative divalent metal ion coordination motif (GDN) that is essential for RNA synthesis of VSV (19). The TGSALHR sequence of the tryptic VSV L peptide (residues 1,222–1,228) including the covalent RNA attachment site (H1227) is located in the block V of the VSV L protein and is completely conserved in the L proteins of known 9 vesiculoviruses such as Chandipura virus and 11 lyssaviruses such as rabies virus belonging to the Rhabdoviridae family (see Fig. S5). Furthermore, amino acid sequence alignment of the L proteins of 86 NNS RNA viruses (40 paramyxoviruses, 38 rhabdoviruses, 6 filoviruses, and 2 bornaviruses) revealed that the histidine-arginine (HR) sequence is strikingly conserved at similar positions in the blocks V of the NNS RNA viral L proteins, except for the L proteins of four known novirhabdoviruses containing similar histidine-lysine (HK) sequences (Fig. S5). Fig. 4A shows local amino acid sequences of selected NNS RNA viral L proteins that surround the HR motif. To analyze the role of the HR motif in RNA capping, the H1227 and R1228 residues were altered individually to different amino acids and the HR sequence was inverted to generate the HR-RH mutant (see Fig. S6A, lanes 2–9). In addition, we introduced a mutation into the conserved D714 residue in the GDN active site motif of RdRp to examine its role in RNA capping (Fig. S6A, lanes 10). First, we measured the enzyme-pRNA intermediate (L-pRNA complex) formation activities of these mutants (Fig. 4B, lanes 1–11). Replacement of H1227 (the RNA attachment site) with alanine, other basic amino acids, or tryptophan dramatically impaired the L-pRNA complex formation activity to background levels (lanes 3–6), suggesting that only histidine can act as a nucleophile among basic amino acids to form the enzyme-pRNA intermediate. As in the case of the H1227 mutations, the R1228A and R1228K mutations also strongly decreased the L-pRNA complex formation activities, suggesting that the R1228 exerts some effect on the H1227-RNA intermediate formation. Interestingly, the R1228H mutant was found to exhibit a weak complex formation activity [15% of the wild-type (WT) activity] (lane 9), whereas the HR-RH mutant was inert (lane 10), indicating that the proper orientation of the H and R residues is essential for the activity. On the other hand, the D714A mutant showed a strong L-pRNA complex formation activity, demonstrating that the RdRp active site is not involved in the enzyme-pRNA intermediate formation. To gain further insight into the effects of mutations on the L-pRNA complex formation, we introduced mutations into basic amino acid residues in the vicinity of the HR motif and other histidine residues conserved among the NNS RNA viral L proteins (see Fig. S6A, lanes 12–20). As expected, alterations of the H1217 and H1236 residues, nonconserved histidine residues, to alanine did not have any negative effects on the L-pRNA complex formation (Fig. 4B, lanes 14 and 20). On the other hand, within the K1220, R1221, and R1233 residues, which are conserved only in the L proteins of vesiculoviruses (e.g., VSV, Chandipura virus), lyssaviruses (e.g., rabies virus), and ephemerovirus (bovine ephemeral fever virus) belonging to the Rhabdoviridae family (Fig. S5), only the R1221 residue was found to be important for the L-pRNA complex formation (lanes 16–18), suggesting that the R1221 residue is required for some step of the complex formation, e,g., recognition of the rhabdovirus-specific mRNA-start sequence (5′-AACA-). The H360 (in the GHP motif) and H639 [in the G(x)8H motif] residues that are conserved histidine residues located in the blocks I and III, respectively, were not required for the L-pRNA complex formation (lanes 21 and 22).

Fig. 4.

The HR motif in the L protein is required for the PRNTase activity. (A) A schematic structure of the VSV L protein is shown with six amino acid sequence blocks (I–VI) conserved in the NNS RNA viral L proteins. The positions of the putative RNA-dependent RNA polymerase (RdRp) and cap methyltransferase (MTase) domains are indicated on the top. The local sequence containing the covalent RNA attachment site (H1227) of the VSV L protein is aligned with those of representative NNS RNA viral L proteins (see Fig. S5). The sequence of the tryptic peptide linked to the RNA (Fig. 2) is underlined. The conserved H and R residues are shown in red and blue, respectively. Basic amino acid residues conserved only in the L proteins of rhabdoviruses are shown in cyan. VSIV, vesicular stomatitis Indiana virus; RABV, rabies virus; BEFV, bovine ephemeral fever virus; MeV, measles virus; MuV, mumps virus; NiV, Nipah virus; HRSV, human respiratory syncytial virus; ZEBOV, Zaire ebolavirus; BDV, Borna disease virus. (B) The WT and mutant L proteins (see Fig. S6A) were incubated with 32P-labeled pppAACAG. The resulting L-pRNA complex was analyzed by SDS-7.5% PAGE followed by autoradiography. Lanes 1 and 12 indicate no L protein. (C) The WT and mutant L proteins (see panel B) were subjected to the capping reactions with pppAACAG and [α-32P]GDP as substrates. CIAP and nuclease P1-resistant products were analyzed by PEI-cellulose TLC followed by autoradiography. Lanes 1 and 12 indicate no L protein. The positions of standard marker compounds are shown on the left.

To examine the effects of mutations on the PRNTase activity of the L protein, we performed the capping assay with [α-32P]GDP and pppAACAG. After the reaction, nuclease P1 and CIAP-resistant cap structures were analyzed by PEI-cellulose TLC followed by autoradiography. The WT L protein produced the Gpp-pA cap structure (Fig. 4C, lanes 2 and 13), whereas the H1227 and R1228 mutants failed to form the cap structures (lanes 3–10), except for the R1228H mutant that showed approximately 9% of the WT activity (lane 9). The D714A mutant efficiently produced the cap structures (lane 11), demonstrating that the RdRp active site is not required for the capping reaction. The R1221A and R1221H mutants were inactive (lanes 16 and 18), whereas the R1221K mutant showed 2% of the WT activity (lane 17) and the other mutants retained capping activities (lanes 14, 15, 19–22). We also measured the capping activity of the mutants with [α-32P]GTP, instead of [α-32P]GDP, as the substrate and confirmed that the H1227, R1228, and R1221 residues are required for the capping activity (Fig. S6B). All of these results are consistent with the formation of the L-pRNA complex by the mutants (Fig. 4B), indicating that the H1227, R1228, and R1221 mutants are deficient in the PRNTase activities presumably at the step of the L-pRNA complex formation. Interestingly, all mutants showed GTPase activities almost uniformly (see Fig. S6C), indicating that the HR motif and R1221 are not involved in the GTPase activity of the L protein. Thus, the active sites of the PRNTase and the GTPase are separately located in the L protein.

Li et al. (20) recently performed alanine scanning mutagenesis of amino acid residues conserved in the block V of the VSV L protein, and identified the G1154, T1157, H1227, and R1228 residues as amino acid residues required for the formation of a tobacco acid pyrophosphatase-sensitive cap-like structure in VSV transcripts as well as capping of pppAACAG oligo-RNA in vitro. The defects of the G1154A, T1157A, H1227A, and R1228A mutants in the formation of the cap-like structure were thought to be due to defects in an RTPase activity (20), which seems unlikely because that RTPase produces a dead-end substrate for the unconventional mRNA capping enzyme of VSV (4). Our mutational analyses clearly demonstrate that the H1227 and R1228 residues are essential for the PRNTase activity at the step of the covalent enzyme-pRNA intermediate formation, but not for the GTPase activity (Fig. 4 and Fig. S6). The precise roles of the G1154 and T1157 residues in the capping reaction, if any, remain unknown. Interestingly, Liuzzi et al. (21) have recently found that small molecule inhibitors against cotranscriptional mRNA capping by the L protein of human respiratory syncytial virus (Paramyxoviridae) prevent virus replication in vivo, and mutant viruses resistant to the inhibitors carry mutant L proteins with amino acid substitutions in the vicinity of the HR motif within the block V. Thus, the block V of the NNS RNA viral L protein appears to be involved in mRNA capping, although the exact boundary of the putative PRNTase domain remains unknown.

Mechanism of the RNA Transfer Reaction Catalyzed by the PRNTase Domain of the VSV L Protein.

Finally, based on our results, we now propose the chemical reactions during the RNA transfer by the VSV L protein (Fig. 5). An electron lone pair formed on the Nε2 position of the catalytic histidine probably attacks the α-phosphorus in the 5′-triphosphate end of the RNA, resulting in the formation of the covalent enzyme-(histidyl-Nε2)-pRNA intermediate (L-pRNA complex) with the concomitant release of PPi. At the second step, a nucleophilic attack by the β-phosphoryl group of GDP on the 5′-terminal α-phosphorus of the RNA linked to the L protein via the phosphoamide bond results in the release of the capped RNA (Gpp-pRNA) from the L protein. Thus, the polyribonucleotidyl transfer reaction with PRNTase involves a series of chemical bond transformations: phosphoanhydride (pp-pRNA) → phosphoamide (L-pRNA) → phosphoanhydride (Gpp-pRNA). This pathway is same as that of mRNA guanylylation catalyzed by GTase of the conventional mRNA capping enzyme, except that the enzyme uses a catalytic lysine within the conserved KxDG motif to transfer the GMP moiety of GTP to the 5′-diphosphate end of RNA via the enzyme-(lysyl-Nε)-GMP intermediate (22). Consistent with the reaction mechanism of the L-pRNA complex formation, we found that pRNA is transferred from the L-pRNA complex to PPi, but not to Pi, to regenerate pppRNA (Fig. S7), indicating that the formation of the L-pRNA complex is reversible. Covalent enzyme-substrate intermediates with phosphoamide bonds on histidine residues are found in several cellular nucleotide transferases and hydrolases (12, 23–25). These enzymes use nucleophilic histidine residues within distinct active site motifs to attack on phosphorus atoms in their target molecules. Therefore, a common catalytic mechanism is thought to be employed by these enzymes. In these enzymes, PRNTase represents the only example of an enzyme capable of transferring a polyribonucleotidyl group to a substrate using a catalytic histidine residue. Elucidation of the molecular mechanisms of the capping reactions catalyzed by the other NNS RNA viral L proteins carrying similar HR motifs will provide further evidence that the PRNTase domains have evolved independently from the cellular mRNA capping enzyme and may offer a rational target for designing specific antiviral agents.

Fig. 5.

A proposed model of the polyribonucleotidyl transfer reaction catalyzed by the unconventional mRNA capping enzyme L protein. For detail, see text.

Materials and Methods

RNA Transfer Reaction from the Purified L-pRNA Complex.

pppAACAG labeled with [α-32P]AMP (3.3 - 3.7 × 104 cpm/pmol) was synthesized by T7 RNA polymerase from a newly developed synthetic DNA template (see Fig. S8), as described in SI Materials and Methods. The L-pRNA complex was generated by incubation of the recombinant carboxyl-terminal octahistidine tagged VSV L protein with 32P-labeled pppAACAG, and purified by chromatography using the phosphocellulose (PC) P11 resin (Whatman), as described in SI Materials and Methods. An aliquot of the PC bound fraction containing 0.09 pmol of the L-pRNA complex was incubated in 10 µL of the VSV capping buffer [25 mM 2-morpholinoethanesulfonic acid–NaOH (pH 5.8 at 30 °C), 2 mM DTT, 5% (vol/vol) glycerol] in the presence of 0.5 mM MnCl2 and 0.25 µM GDP (Fig. 1) or 5 µM NaPPi (Fig. S7) at 30 °C for 1 min. The reaction was stopped by adding 10 µL of the stopping solution (96% formamide, 10 mM EDTA, 0.01% Bromophenol Blue, 0.01% xylene cyanol FF). Samples were subsequently analyzed by urea-20% PAGE followed by autoradiography. The capped RNA released from the L-pRNA complex was isolated and characterized, as described in SI Materials and Methods (see Fig. S2).

MALDI-TOF MS Analysis of the Peptide-AMP Complex.

The covalent peptide-AMP complex was generated by digestion of the L-pRNA complex with trypsin followed by nuclease P1, and purified, as detailed in SI Materials and Methods. The peptide-AMP complex (0.6 pmol) was dissolved in 1 µL of a matrix solution [5 mg/mL α-cyano-4-hydroxycinnamic acid (Sigma-Aldrich), 0.1% TFA, 50% acetonitrile], and spotted onto a MALDI target plate. The Applied Biosystems 4800 Proteomics Analyzer equipped with a 200 Hz Nd:YAG laser (355 nm) and TOF/TOF optics was employed for MS analyses in the reflector positive-ion mode. MS/MS spectra were obtained at a collision energy of 1 kV without the presence of gas. Data were analyzed using the Data Explorer software (Applied Biosystems).

Phosphoamino Acid Analysis.

The covalent amino acid (X)-[α-32P]AMP complex was produced by digestion of the L-pRNA complex with proteinase K followed by nuclease P1, and purified as described in SI Materials and Methods. The X-AMP (40 fmol, 400 cpm) was incubated with or without 0.5 mM sodium periodate in 4 µL of 50 mM sodium carbonate buffer (pH 10.5 at 25 °C) for 30 min in the dark at room temperature. The oxidation reaction was stopped by adding 0.5 µL of 20 mM ethylene glycol. The reaction mixture was incubated at 50 °C for 1 h to generate a 32P-labeled phosphoamino acid (X-p). The product was spotted along with marker compounds (see SI Materials and Methods, Fig. S9) on a reverse phase silica gel TLC plate (RP-18 F254s, EMD Chemicals), and developed with a solvent mixture consisting of ethanol, 28% ammonium hydroxide, H2O (72:10:9, vol:vol), as described by Tan et al. (13). Nucleotides on the TLC plate were detected under UV light at wavelength of 254 nm. Amino acid standards were visualized by spraying the TLC plate with 0.5% ninhydrin (Acros Organics). 32P-labeled compounds were detected by autoradiography.

Cap-Forming Assays.

The enzyme-pRNA complex formation assay (4) and RNA capping assay (4, 5) were performed as described in SI Materials and Methods.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments.

We thank Dr. John W. Crabb (Cole Eye Institute, Cleveland Clinic) for his assistance in the mass spectrometric experiments. This work was supported by a grant from the National Institutes of Health (AI26585, to A.K.B.).

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

This article is a PNAS Direct Submission.

See Commentary on page 3283.

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/cgi/content/full/0913083107/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Banerjee AK. 5′-terminal cap structure in eucaryotic messenger ribonucleic acids. Microbiol Rev. 1980;44:175–205. doi: 10.1128/mr.44.2.175-205.1980. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Furuichi Y, Shatkin AJ. Viral and cellular mRNA capping: Past and prospects. Adv Virus Res. 2000;55:135–184. doi: 10.1016/S0065-3527(00)55003-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Shuman S. Structure, mechanism, and evolution of the mRNA capping apparatus. Prog Nucleic Acid Res Mol Biol. 2001;66:1–40. doi: 10.1016/s0079-6603(00)66025-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ogino T, Banerjee AK. Unconventional mechanism of mRNA capping by the RNA-dependent RNA polymerase of vesicular stomatitis virus. Mol Cell. 2007;25:85–97. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2006.11.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ogino T, Banerjee AK. Formation of guanosine(5′)tetraphospho(5′)adenosine cap structure by an unconventional mRNA capping enzyme of vesicular stomatitis virus. J Virol. 2008;82:7729–7734. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00326-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Schubert M, Lazzarini RA. In vitro transcription of vesicular stomatitis virus. Incorporation of deoxyguanosine and deoxycytidine, and formation of deoxyguanosine caps. J Biol Chem. 257:2968–2973. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Venkatesan S, Moss B. Eukaryotic mRNA capping enzyme-guanylate covalent intermediate. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1982;79:340–344. doi: 10.1073/pnas.79.2.340. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Venkatesan S, Moss B. Donor and acceptor specificities of HeLa cell mRNA guanylyltransferase. J Biol Chem. 1980;255:2835–2842. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Martin SA, Moss B. mRNA guanylyltransferase and mRNA (guanine-7-)-methyltransferase from vaccinia virions. Donor and acceptor substrate specificites. J Biol Chem. 251:7313–7321. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Liao PC, Leykam J, Andrews PC, Gage DA, Allison J. An approach to locate phosphorylation sites in a phosphoprotein: Mass mapping by combining specific enzymatic degradation with matrix-assisted laser desorption/ionization mass spectrometry. Anal Biochem. 1994;219:9–20. doi: 10.1006/abio.1994.1224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sickmann A, Meyer HE. Phosphoamino acid analysis. Proteomics. 2001;1:200–206. doi: 10.1002/1615-9861(200102)1:2<200::AID-PROT200>3.0.CO;2-V. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Yang SL, Frey PA. Nucleophile in the active site of Escherichia coli galactose-1-phosphate uridylyltransferase: Degradation of the uridylyl-enzyme intermediate to N3-phosphohistidine. Biochemistry. 1979;18:2980–2984. doi: 10.1021/bi00581a011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tan E, Lin Zu X, Yeoh GC, Besant PG, Attwood PV. Detection of histidine kinases via a filter-based assay and reverse-phase thin-layer chromatographic phosphoamino acid analysis. Anal Biochem. 2003;323:122–126. doi: 10.1016/j.ab.2003.08.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Poch O, Blumberg BM, Bougueleret L, Tordo N. Sequence comparison of five polymerases (L proteins) of unsegmented negative-strand RNA viruses: Theoretical assignment of functional domains. J Gen Virol. 1990;71:1153–1162. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-71-5-1153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bujnicki JM, Rychlewski L. In silico identification, structure prediction and phylogenetic analysis of the 2′-O-ribose (cap 1) methyltransferase domain in the large structural protein of ssRNA negative-strand viruses. Protein Eng. 2002;15:101–108. doi: 10.1093/protein/15.2.101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Grdzelishvili VZ, et al. A single amino acid change in the L-polymerase protein of vesicular stomatitis virus completely abolishes viral mRNA cap methylation. J Virol. 2005;79:7327–7337. doi: 10.1128/JVI.79.12.7327-7337.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Li J, Fontaine-Rodriguez EC, Whelan SP. Amino acid residues within conserved domain VI of the vesicular stomatitis virus large polymerase protein essential for mRNA cap methyltransferase activity. J Virol. 2005;79:13373–13384. doi: 10.1128/JVI.79.21.13373-13384.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ogino T, Kobayashi M, Iwama M, Mizumoto K. Sendai virus RNA-dependent RNA polymerase L protein catalyzes cap methylation of virus-specific mRNA. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:4429–4435. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M411167200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sleat DE, Banerjee AK. Transcriptional activity and mutational analysis of recombinant vesicular stomatitis virus RNA polymerase. J Virol. 1993;67:1334–1339. doi: 10.1128/jvi.67.3.1334-1339.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Li J, Rahmeh A, Morelli M, Whelan SP. A conserved motif in region v of the large polymerase proteins of nonsegmented negative-sense RNA viruses that is essential for mRNA capping. J Virol. 2008;82:775–784. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02107-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Liuzzi M, et al. Inhibitors of respiratory syncytial virus replication target cotranscriptional mRNA guanylylation by viral RNA-dependent RNA polymerase. J Virol. 2005;79:13105–13115. doi: 10.1128/JVI.79.20.13105-13115.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Shuman S, Lima CD. The polynucleotide ligase and RNA capping enzyme superfamily of covalent nucleotidyltransferases. Curr Opin Struct Biol. 2004;14:757–764. doi: 10.1016/j.sbi.2004.10.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Brenner C. Hint, Fhit, and GalT: Function, structure, evolution, and mechanism of three branches of the histidine triad superfamily of nucleotide hydrolases and transferases. Biochemistry. 2002;41:9003–9014. doi: 10.1021/bi025942q. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Billy E, Hess D, Hofsteenge J, Filipowicz W. Characterization of the adenylation site in the RNA 3′-terminal phosphate cyclase from Escherichia coli. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:34955–34960. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.49.34955. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Interthal H, Chen HJ, Champoux JJ. Human Tdp1 cleaves a broad spectrum of substrates, including phosphoamide linkages. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:36518–36528. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M508898200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.