Abstract

Importance of the field

Xenobiotic receptors (XRs) play pivotal roles in regulating the expression of genes that determine the clearance and detoxification of xenobiotics, such as drugs and environmental chemicals. Recently, it has become increasingly evident that most XRs shuttle between the cytoplasm and nucleus, and activation of such receptors is directly associated with xenobiotic-induced nuclear import.

Areas covered in this review

The scope of this review covers research literature that discusses nuclear translocation and activation of XRs, as well as unpublished data generated from this laboratory. Specific emphasis is given to the constitutive androstane receptor (CAR), the pregnane X receptor, and the aryl hydrocarbon receptor.

What the readers will gain

A number of molecular chaperons presumably associated with cellular localization of XRs have been identified. Primary hepatocyte cultures have been established as a unique model retaining inactive CAR in the cytoplasm. Moreover, several splicing variants of human CAR exhibit altered cellular localization and chemical activation.

Take home message

Nuclear accumulation is an essential step in the activation of XRs. Although great strides have been made, much remains to be understood concerning the mechanisms underlying intracellular localization and trafficking of XRs, which involve both direct ligand-binding and indirect pathways.

Keywords: Xenobiotic receptors, translocation, activation, constitutive androstane receptor, pregnane X receptor, aryl hydrocarbon receptor

1. Introduction

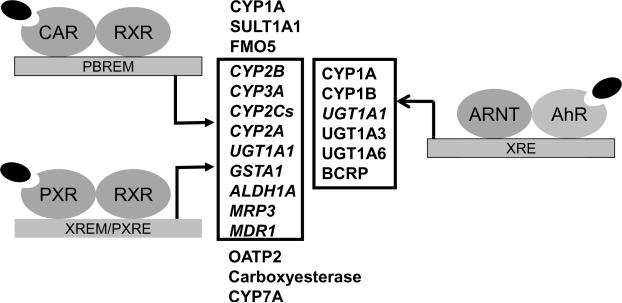

Nuclear receptors (NRs) are transcription factors that act as sensors of the extracellular and intracellular signals, and play crucial roles in the control of biological development, differentiation, metabolic homeostasis, and protection against xenobiotic-induced stresses. In humans, 48 members of NRs have been identified and divided into three classes based on their ligand binding specificities [1]. Endocrine receptors such as androgen receptor, estrogen receptor (ER), and glucocorticoid receptor (GR), are responsive to particular steroid hormones. The orphan receptors represent gene products with typical NR characteristic structure and sequence identity but have no endogenous ligand been identified, and quantitatively they account for the largest class in human NR superfamily. Recently, the physiological ligands for a number of orphan receptors have been identified. Accordingly, these receptors were classified into the third group NRs namely the adopted orphan receptors. Members of the classical endocrine receptors are capable of binding unique high-affinity endogenous ligands at nanomolar concentrations. In contrast, the members of the orphan NRs, lacking identifiable physiological high-affinity ligands, are activated by abundant but low-affinity lipophilic molecules with dissociation constants in the micromolar concentrations [2, 3]. Notably, a number of receptors exhibit promiscuous xenobiotic binding capability and function as sensors of toxic byproducts derived from endogenous and exogenous chemical breakdowns. Termed xenobiotic receptors (XRs), these receptors are capable of regulating the transcriptional activation of genes encoding Phase I and II drug-metabolizing enzymes (DMEs) as well as uptake and efflux transporters. Major XRs including constitutive androstane receptor (CAR, NR1I3), pregnane X receptor (PXR, NR1I2), and aryl hydrocarbon receptor (AhR), are expressed predominantly in the liver and intestines where their target genes are also located [4, 5]. Unlike CAR and PXR, which belong to typical NRs, AhR is a ligand-activated transcription factor of the basic helix-loop-helix (bHLH) protein of the PAS (Per-ARNT-Sim) family [6]. Coordinately, these XRs regulate a broad set of distinct and overlapping target genes, orchestrating a hepatoprotection system in response to harmful environmental stimuli (Fig. 1). XRs are nucleo-cytoplasmic shuttling proteins, and both subcellular compartmentalization and intracellular trafficking of XRs are crucial regulatory steps in executing their transcriptional functions. Without chemical stimulation, XRs are sequestered predominantly in the cytoplasmic compartment in vivo or in cultured primary hepatocytes, while accumulating in the nucleus in response to ligand binding or other activation signals [7–10]. This translocation process serves as the first essential step for the activation of all XRs.

Figure 1.

Distinct and overlapping target genes of CAR, PXR and AhR. Drug metabolizing related genes such as CYP2B, CYP3A, CYP2Cs, CYP2A, GSTA1, ALDH1A, MRP3, and MDR1 are shared targets for CAR and PXR; CYP1A is a shared target for CAR and AhR; SULT1A1 and FMO5 are specific targets for CAR; OATP2, Carboxyesterase, and CYP7A are specific targets for PXR; CYP1B, UGT1A3, UGT1A6, and BCRP are specific targets for AhR; while UGT1A1 is a target gene shared by all three XRs.

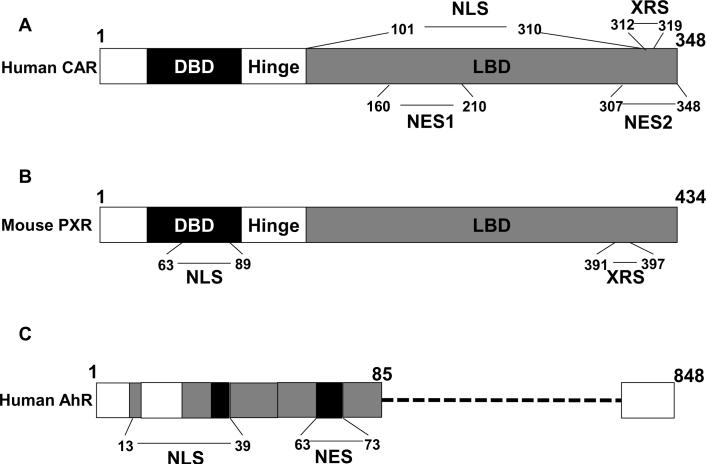

Similar to the classical nuclear hormone receptors, members of xenobiotic-activated NRs are structurally characterized by a highly variable N-terminal transactivation domain (AF-1), a DNA binding domain (DBD), a hinge region and a ligand binding domain (LBD) that includes the C-terminal transactivation domain (AF-2) [11, 12]. These receptors bind to specific response elements in the promoter of their target genes through the highly conserved DBD, while the less conserved LBD contains sequences mediating receptor nuclear localization, dimerization, and recruitment of coregulators [13, 14].

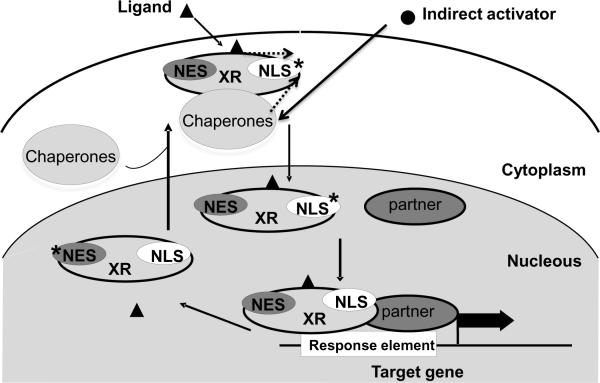

Upon interaction with a ligand or other activation signals, the activated receptors dissociate with the protein complex by which they were held in the cytoplasm and translocate to the nucleus. For most of the NRs, nucleo-cytoplasmic shuttling requires both the nuclear localization signal (NLS) and the nuclear export signal (NES) [15, 16]. Thus, the intracellular residence of NRs is determined by a functional balance between the NLS and NES (Fig. 2).

Figure 2.

Schematic model of nucleo-cytoplasmic shuttling of XRs. Intracellular residence of XR is determined by a balance between NLS and NES functions. NLS*: indicates the NLS signaling was activated after direct ligand binding or indirect dissociation of the receptor from its cytosolic chaperons, leading to the nuclear translocation; NES*: indicates the NES signaling was activated after nuclear localized XR dissociated with its ligand and heterodimeric partner, leading to the export of XR from the nucleus.

In this review, we focus on recent progress in understanding the mechanisms of intracellular localization and translocation of XRs. To restrict the scope of this review, specific emphasis has been given to the major XRs, CAR, PXR, and AhR. In so doing, we hope to highlight how environmental chemicals and drugs initiate the activation of these xenobiotic sensors by driving them into the nucleus.

2. Constitutive Androstane/Activated Receptor

As a result of screening a human liver library with degenerate oligonucleotide probes, the full-length cDNA of human CAR (hCAR, NR1I3) was cloned in 1994, and termed initially MB67 [17]. Soon thereafter, its rodent counterparts were cloned from mouse and rat [18, 19]. Nevertheless, the impact of CAR on xenobiotic metabolism was only appreciated when activation of CAR was linked to the induction of the CYP2B gene family by phenobarbital (PB) and PB-like inducers [20]. Belonging to the same subgroup of orphan NRs as the PXR, CAR expression occurs predominantly in the liver and intestine [4]. In the absence of ligand binding, CAR forms a heterodimer with the 9-cisretinoic acid receptor (RXR) and transactivates a set of genes containing putative retinoic acid response elements, thus the name CAR was originally defined as constitutive activated receptor [18]. The unique feature that CAR is constitutively activated in immortalized cell lines but not in liver in vivo or in the culture of primary hepatocytes has generated tremendous interest in identifying factors that retain the CAR at low basal activity in these physiologically relevant systems [8, 21]. Original ligands identified for CAR include the testosterone metabolites 5α-androstan-3α-ol (androstanol) and 5α-androst-16-en-3α-ol (androstenol) [22]. These compounds were classified as inverse agonists that switch off the constitutive activity of CAR in vitro by disrupting its interaction with the coactivator steroid receptor coactivator 1 (SRC-1) [22]. Accordingly, CAR was also referred to as constitutive androstane receptor. Subsequent studies have led to the discovery of two potent ligands: 4-bis[2-(3,5 dichloropyridyloxy)] benzene (TCPOBOP), as a direct agonist of mouse CAR (mCAR) capable of stabilizing the interaction between CAR and SRC-1 and derepressing the inhibitory effects of androstanes [22, 23]; and 6-(4-chlorophenyl)imidazo[2,1-beta][1,3]thiazole-5-carbaldehyde-O-(3,4-dichlorobenzyl) oxime (CITCO), as selective agonistic ligand for hCAR [24]. Nevertheless, as summarized in table 1, the majority of currently available CAR activators, such as PB, efavirenz, phenytoin, and carbamazepine, do not bind directly to the receptor rather they function through the mutedly defined indirect mechanisms [8, 10, 22–53]. The activation of CAR by indirect activators seems involving exclusively in the nuclear translocation of CAR via mechanisms yet to be fully elucidated.

Table 1.

List of identified CAR activators and deactivators

| Classification | Compounds | References |

|---|---|---|

| Human CAR activators | Phenobarbital | [25] |

| Chlorpromazine | [26] | |

| CITCO | [24] | |

| Phenotyin | [27] | |

| Acetaminophen | [28] | |

| 6,7-Dimethylesculetin | [29] | |

| Artemisinin | [30] | |

| Atorvastatin; Cerivastatin; Fluvastatin; Simvastatin | [31] | |

| Tri-p-methylphenyl phosphate;Triphenyl phosphate | [32] | |

| Efavirenz; Nevirapine; Carbamazepine | [33] | |

| Thiazolidin-4-ones; Sulfonamides | [34] | |

| Myclobutanil; Butylated hydroxyanisole; Diazepam | [10] | |

| Rodent CAR activators | TCPOBOP | [23] |

| Phenobarbital | [35] | |

| 17β-Estradiol; Estrone | [36] | |

| Chlorpromazine | [25] | |

| Acetaminophen | [37] | |

| 17α-Ethynyl-3,17β-estradiol | [38] | |

| Bilirubin | [39] | |

| Orphenadrine | [40] | |

| Phenotyin | [41] | |

| Meclizne | [28] | |

| Atorvastatin; Fluvastatin; Cerivastatin; Simvastatin | [31] | |

| Triphenyldioxane | [42] | |

| trans-Stilbene oxide | [43] | |

| Diallyl sulfide; Diallyl disulfide | [44] | |

| Oltipraz | [45] | |

| Perfluorodecanoic acid | [46] | |

| Human CAR deactivators | Clotrimazole | [47] |

| 17α-Ethynyl-3,17β-estradiol | [48] | |

| Meclizne | [28] | |

| PK11195 | [49] | |

| Rodent CAR deactivators | 5α-androstan-3α-ol; 5α-androst-16-en-3α-ol | [22] |

| Okadaic acid | [8] | |

| Progesterone; Testosterone | [36] | |

| KN-62 | [50] | |

| KN-93 | [51] | |

| Guggulsterone | [52] | |

| Wy-14643; Ciprofibrate | [53] |

2.1 Subcellular distribution and translocation of CAR

In contrast to other orphan NRs and AhR, CAR exhibits unique subcellular distribution and activation patterns between immortalized cell lines and physiologically relevant primary cells. In primary hepatocytes and intact liver in vivo, CAR resides in the cytoplasm under basal conditions and translocates to the nucleus after exposure to PB-type inducers [8]. Whereas in transformed cell lines, such cellular factors that held CAR in the cytoplasm are missing or malfunctioning, therefore CAR is constitutively nuclear-localized and activated in these cells even in the absence of chemical stimulation [8, 21, 53, 54]. This feature of CAR exhibits dramatic differences from other nuclear-translocational receptors, such as GR and AhR, where both are efficiently sequestered in the cytoplasm of hepatoma cell lines and translocated into the nucleus upon agonistic ligand binding [55, 56]. The key elements of cytoplasmic retention of GR and AhR reside in their capability to form functional protein complexes with molecular chaperons including heat shock protein 90 (Hsp90) and co-chaperons, such as immunophilin FK-binding proteins and hepatitis B virus protein X-associated protein 2 (XAP2) [57, 58].

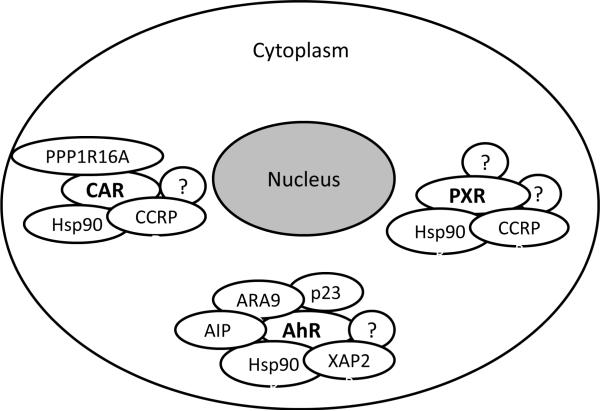

Recently, Negishi and colleagues have partially elucidated the components of the CAR cytoplasmic complex, which includes Hsp90, cytoplasmic CAR retention protein (CCRP), and a membrane-associated subunit of protein phosphatase 1β (PPP1R16A) [59–61] (Fig. 3). In HepG2 cells, overexpressed CCRP directly binds to the LBD of transfected mCAR and retains it in the cytoplasm via an indirect association between CAR and Hsp90 by forming the CAR-CCRP-Hsp90 complex [59]. Subsequent analysis using fluorescently tagged hCAR expressed in mouse liver demonstrated that nuclear localization of CAR is AF-2 independent, but requires an amino acid leucine-rich motif (LXXLXXL) within the C-terminal region termed the xenobiotic response sequence (XRS) (Fig. 4A) [54] [62]. An additional feature uncovered for CAR cellular translocation involves the membrane accumulation of CAR upon PB treatment, which concurs simultaneously with the predominant nuclear translocation [63]. Recently, direct interaction between CAR and the membrane-bound PPP1R16A as a subunit of protein phosphatase has been observed in vitro, these results raises the possibility of signaling components important in CAR activation located at the cell membrane, and CAR may exert a novel non-genomic action [60, 63]. Importing CAR to the nucleus, presumably dependent on the activity of the protein phosphatase 2A (PP2A), and pretreatment with PP2A inhibitor, okadaic acid (OA), blocked PB-induced CAR translocation in mouse primary hepatocyte cultures [8].

Figure 3.

Cytoplasmic complexes of CAR, PXR, and AhR. Hsp90, CCRP, and PPP1R16A are known chaperones for cytoplasmic CAR; Hsp90, a membrane-associated subunit of protein phosphatase 1β, XAP2, AhR-associated protein 9 (ARA9), and AhR-interacting protein (AIP) are known chaperones for cytoplasmic AhR; Hsp90 and CCRP are known chaperones for cytoplasmic PXR.

Figure 4.

Simplified sequence location of the nucleo-cytopkamic signals in CAR, PXR and AhR. The location of NLS, NES, and XRS are depicted for human CAR (A), mouse PXR (B), and human AhR (C). The diagrams were adopted from references 62, 106, and 143, respectively, with minor modification.

Additionally, several coactivators have been reported to modulate CAR activation by triggering CAR subnuclear targeting or nuclear translocation. The p160 transcription factor GR-interacting protein 1 (GRIP-1) was identified as an XRS-binding protein assisting in CAR nuclear accumulation [64]. Studies employing a mouse peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor binding protein (PBP) knockout model revealed that loss of PBP results in the abrogation of PB-induced CAR nuclear translocation, implicating the role of PBP in regulating CAR localization and activation [65]. Together, the unique characteristics of CAR in its cellular localization and nuclear translocation further heightened the complexities in our understanding of chemical-mediated activation of this receptor.

2.1.1 Species-specific characteristics

Although hCAR and its rodent orthologs share several common features and are all expressed predominantly in the liver and intestines, dramatic pharmacological distinction exists amongst these receptors. For instance, TCPOBOP, the most potent mCAR ligand identified to date, cannot bind or activate either rat or human CAR, androstanol represses mouse but not human CAR, and clotrimazole (CLZ) represses human but not mouse CAR [22, 47, 66]. In addition, progesterone and testosterone repress, while estradiol activates, mCAR but not hCAR [36]. This species-specific ligand profile relies on the sequence divergence in the LBDs of the rodents and human receptors. Comparison of the ligand binding pockets between mouse and human CAR revealed a key amino acid difference at position 350. Substitution of threonine 350 in mouse to methionine in human resulted in abolishment of mouse responsiveness to TCPOBOP and steroid hormones [67]. The species-specific differences of CAR activation were reflected also at the stage of nuclear translocation. In adenoviral-EYFP-tagged hCAR (Ad/EYFP-hCAR) infected human primary hepatocytes (HPHs), Wy-14,643 failed to reallocate hCAR to the nucleus of HPHs, in contrast with the observation made by Guo et al. in adenoviral-mCAR-infected mouse liver [10, 53]. Moreover, pretreatment with OA did not inhibit PB-mediated nuclear translocation of hCAR in HPHs, which differs from an early observation of mCAR in mouse primary hepatocytes [8]. These data indicate that other than ligand binding, indirect mechanisms may also contribute to the observed species difference of CAR activation.

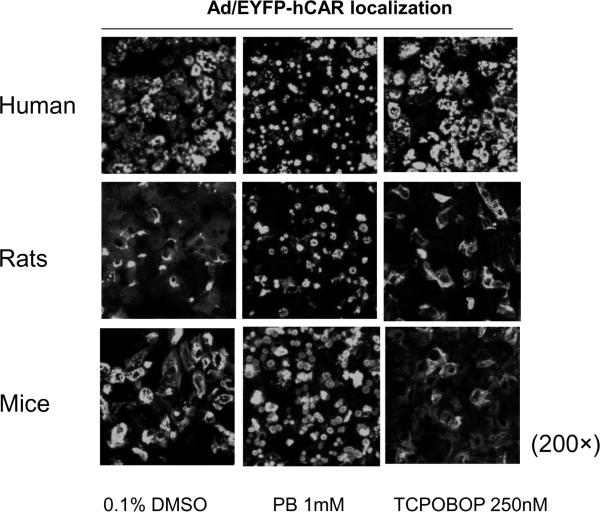

Generation of transgenic CAR-null mice especially the humanized CAR mice model has made it possible to specifically address the effects of this receptor on the regulation of its target gene in vivo. In CAR-null mice the potent induction of Cyp2b10 gene expression by PB and TCPOBOP was totally absent [35]. Similarly, in obese Zucker rats, which express extremely low levels of CAR, PB only moderately induced both CYP2B and CYP3A [68]. Given that xenobiotic induction of DMEs displays striking species specificity due to the species-dependent biochemical properties of NRs, a CAR humanized mouse line has also been generated. This line specifically expresses hCAR in the mCAR-null mice liver driven by the potent albumin promoter [37]. Using this model, meclizine, a widely used antiemetic has been established as both an agonist for mCAR and an inverse agonist for hCAR. In this report, although treatment with meclizine augmented the expression of CAR target genes in wild-type mice, both hCAR transactivation and the PB-induced expression of CAR target genes were inhibited by meclizine treatment in primary hepatocytes isolated from the liver of humanized CAR mice [28]. This fact concurs with the presumed notion that it is the nature of xenobiotic receptors rather than the cellular environment that controls the chemical specificity of DMEs induction among different species [69, 70]. Indeed, our recent data also demonstrated that Ad/EYFP-hCAR was translocated by PB but not TCPOBOP to the nucleus of infected human, rat and mouse hepatocytes (Fig. 5). Taken together, it is clear that significant similarity and distinction between hCAR and its rodent counterparts are contributed by a plethora of complicated factors, and fully appreciation of these differences awaits more diligent studies.

Figure 5.

Chemical-stimulated nuclear accumulation of hCAR in primary hepatocytes. Primary hepatocyte cultures prepared from human, rat and mouse livers were infected with Ad/EYFP-hCAR, then treated with PB (1 mM) or TCPOBOP (250 nM) for 24 hrs. Cellular localization of infected hCAR was visualized under confocal microscope.

2.1.2 Translocation of splice variants of human CAR

Besides species-specificities, coactivators and corepressors, genetic variations in the CAR gene may also account for its functional characteristics including cellular localization and nuclear translocation. To date, more than twenty unique hCAR splice variants have been identified, including different combinations of splicing such as deletions of exons 2, 4, 5, and 7, partial deletion of exon 9, and in frame insertion of 12 or 15 nucleotides from introns 6 or 7 [71–74]. Often these variant transcripts were generated by multiple splicing events in various combinations [73]. Interestingly, differential CAR variants yielded splicing proteins with alterations located in LBD, DBD, AF1, and AF2 domains, and some of them displayed tissue-specific expression and/or distinct pharmacological activation patterns [71, 73–76]. As such, it its evident that different variants of CAR may exhibit varied biological functions in vivo, and some of them are associated with diverse ligand specificities.

Although the functional significance of these CAR variants remains unknown in vivo, several splice variants exhibited reduced binding to CAR response elements, decreased gene transactivation potential, and altered cellular localization and translocation features in vitro [72–75]. Four splice variants that are abundantly expressed in the human liver have been characterized regarding their cellular localization in transfected primary hepatocytes. These splice variants include the SV1 and SV2 containing in-frame 12- and 15-bp insertions in the LBD of hCAR, respectively; the SV3 carrying both of the SV1 and SV2 insertions; and the SV4 with an in-frame 117-bp deletion between the insertion sites of SV1 and SV2 [75]. Once expressed in rat hepatocytes, these four variants were unable to localize to the nucleus after treatment with the hCAR activators PB and CITCO, which are in sharp contrast to the nature of the reference hCAR [75].

In an effort to understand the roles of naturally-occurring alternative splicing variants of hCAR, several studies indicate that one of these variants, the hCAR3 which contains an in-frame insertion of 5 amino acids (APYLT) in the highly conserved region of the LBD, also named SV2 as mentioned above, exhibited minimal basal but efficient ligand-induced activities in cell-based reporter assays [33, 75, 77]. Intriguingly, although CITCO treatment was incapable of facilitating hCAR3 nuclear translocation in COS1 cells, or rat primary hepatocytes [75, 77], it enhanced the recruitment of SRC-1 and GRIP-1 to the hCAR3 which already resides in the nucleus [77, 78]. The hCAR3 seems to exert a unique functional feature regarding the constitutive activity and cellular distribution.

To define the contribution of the 5 amino acid insertion on the functional transformation of hCAR3, a series of chimeric constructs containing various residues of the 5 amino acid insertion have been generated [78]. Functional evaluation demonstrated that retention of the alanine (A) residue alone, designated as hCAR1+A, appears sufficient to shift the constitutively activated hCAR (hCAR1) to the xenobiotic sensitive hCAR3. Furthermore, intracellular localization assays revealed that hCAR1+A exhibits nuclear translocation upon CITCO treatment in COS1 cells, which may represent an exciting new model for studying hCAR translocation in immortalized cell lines [78]. Notably, this alanine residue is not located to the leucine-rich XRS region which dictates nuclear translocation of CAR in response to PB in mouse liver [54]. However, since the XRS contains multiple amino acid residues responsible for inter- and intra-molecular interactions, it is possible that the alanine insertion may interact with specific amino acids within the XRS and affect the translocation of hCAR subsequently.

2.2 Activation of CAR

2.2.1 Direct activation of CAR

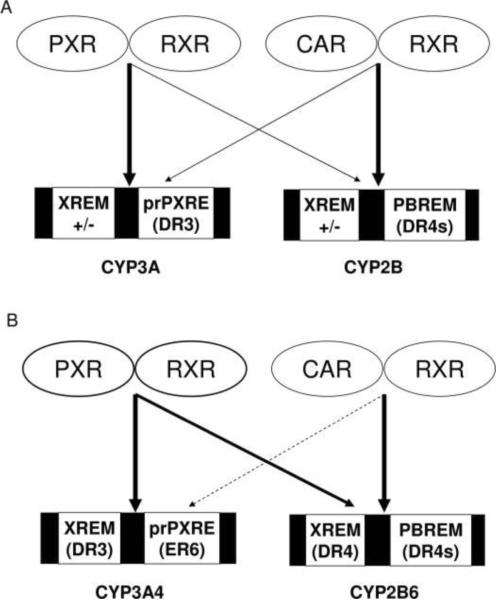

Compared with other NRs, the hallmark mechanisms of CAR activation lie in two different models: the direct ligand-binding, and the ligand-independent (indirect) pathway. Similar to other nuclear hormone receptors, CAR could be activated through direct ligand binding that alters both nuclear translocation and its interaction with coregulators. Using a combination of in vivo and in vitro approaches, Tzameli et al., identified TCPOBOP as the first potent and selective mCAR ligand, whereby TCPOBOP directly competed with the inhibitory effects of inverse agonist androstanol, stimulated coactivator interaction with the LBD of mCAR, and more importantly mutation of the ligand binding pocket blocked the stimulatory effects of TCPOBOP [23]. In contrast, attempts to define the role of hCAR activation have been proven to be difficult due largely to the significant overlap in the pharmacology of hCAR and human PXR (hPXR). Moreover, pharmacological concentrations of androstanes are inverse agonists of mouse but not human CAR [22, 79]. Previously identified hCAR ligands such as CLZ and 5β-pregnane-3,20-dione are also activators of hPXR [47, 80]. Notably, although the antagonistic nature of CLZ in vivo is yet to be verified, CLZ exhibits high binding affinity to hCAR in vitro [47]. Through in vitro and cell-based screening, the imidazothiazole derivative, CITCO was reported as the first selective hCAR agonist, which makes it possible for direct comparison of the overlapping and distinct target genes between hCAR and hPXR, as well as hCAR and mCAR [24]. Indeed, evaluation of selective hCAR and hPXR agonists in HPHs and other in vitro approaches, has led to the development of a model of asymmetrical cross-regulation of CYP2B6 and CYP3A4 by hCAR but not hPXR, in that hCAR exhibits preferential induction of CYP2B6 relative to CYP3A4 that differs from the presumed rodent model (Fig. 6) [81]. Interestingly, this selective role of hCAR on CYP2B6 over CYP3A4 may have clinical relevance with respect to the bioactivation of prodrugs. For example, cyclophosphamide (CPA), an antineoplastic alkylating agent, undergoes N-dechloroethylation to an inactive toxic metabolite exclusively by CYP3A4 and 4-hydroxylation to a therapeutically active metabolite primarily by CYP2B6 [82, 83]. Assuming that hCAR selectivity for CYP2B6 also occurs in vivo, concurrent administration of CPA with a selective hCAR activator should facilitate enhanced production of its beneficial metabolite without simultaneously increasing formation of its toxic metabolite. These expected effects provide the opportunity to develop therapeutic regimens that optimize beneficial versus undesired toxic effects of CPA in cancer treatment.

Figure 6.

Model of cross-talk between PXR and CAR in the regulation of CYP2B and CYP3A genes. A: PXR and CAR cross-talk in rodent animals; B: Asymmetric cross-talk between PXR and CAR in humans. (Adopted from reference 81)

Given the unique nature of CAR activation, in vitro ligand-binding assays only offer limited value in identifying CAR activators. Actually, the majority of the compounds identified in an in vitro binding assay using CLZ as probe were unable to induce CYP2B6 expression in HPHs [24]. Furthermore, the X-ray crystal structure analysis revealed that CAR contains a single-turn helix X that restricts the conformational freedom of the C-terminal AF2 helix in the active position without ligand binding, while the CITCO-bound hCAR simply maintains the constitutively active apo-CAR conformation [84]. Together, these data support that agonist-mediated activation of hCAR relies primarily on its ability to translocate CAR into the nucleus.

2.2.2 Indirect activation of CAR

Activation of CAR through the ligand-independent pathway represents a unique feature that differentiates this receptor from the typical endocrine receptors. PB, the prototypical inducer of CYP2B gene in multiple species, does not bind to either mouse or human CAR, but stimulates translocation of both receptors to the nucleus [8, 10, 23, 47]. To date, the majority of identified CAR activators actually activate the receptor through PB-like indirect mechanisms [23, 47, 85, 86]. With the intrinsic activation of CAR upon translocation to the nucleus, additional ligand-dependent activation seems redundant to this receptor at times. Accordingly, understanding the mechanism of PB-mediated CAR translocation has been one of the major focuses in deciphering CAR activation.

Initial evidence regarding the mechanism of PB-triggered CAR translocation comes from the observation that PB-mediated nuclear translocation of mCAR and induction of Cyp2b10 gene was repressed in mouse primary hepatocyte cultures by the pretreatment of OA, the prototypical inhibitor of PP2A, suggesting that dephosphorylation might be involved in the indirect activation of CAR [8]. This early postulation was further supported by diligent work from Dr. Negishi and coworkers, in that the LBD located Ser-202 of mCAR was identified as a key phosphorylation site [87]. Mutation of Ser-202 to aspartic acid compartmentalized CAR in the cytoplasm of HepG2 cells irresponsive to PB. Moreover, Ser-202-phosphorylated CAR was only detected in the cytoplasm of transfected HepG2 cells using an antibody against a peptide containing phosphorylated Ser-202 [87]. These data revealed the critical roles of Ser-202 dephosphorylation in CAR nuclear translocation. On the other hand, whether Ser-202 was dephosphorylated by PP2A or other signaling molecules is not known. Recently, several reports have discussed a novel role of AMP-activating protein kinase (AMPK) signaling in PB- vs. CITCO-mediated induction of CYP2B6 [88, 89]. Nevertheless, the effects of CAR in these processes are largely unanswered yet.

Although the mechanisms underlying PB-mediated CAR translocation have not been well understood thus far, the unique nature of CAR localization and translocation in primary hepatocytes provides an attractive model for in vitro identification of PB-like activators of CAR in a potentially high-throughput manner. One of the drawbacks of utilizing primary hepatocyte cultures, however, is the quiescent nature of these cells in vitro in which the efficiency of chemical-based transfection was extremely low. To circumvent this shortcoming, Li et al. generated an Ad/EYFP-hCAR construct that infects HPHs with high efficiency and yet maintains hCAR distribution features in a physiologically relevant fashion [10]. Through evaluating 22 compounds in this experimental system, significant correlations have been observed between the chemical-mediated nuclear accumulation of Ad/EYFP-hCAR in HPHs and hCAR activation/target gene induction [10].

On the other hand, it is worth mentioning that translocation alone is not always sufficient for the activation of CAR. Recently, several lines of evidence support nuclear activation as a distinct step in CAR-mediated gene regulation. First, CAR-mediated activation of reporter genes is maintained in HepG2 cells despite OA pretreatment. Since CAR is localized constitutively in the nucleus in HepG2 cells, this observation suggests that OA inhibits translocation but not nuclear activation. Secondly, pretreatment of primary mouse hepatocytes with calcium/calmodulin-dependent kinase (CaMK) inhibitors repressed PB- and TCPOBOP-associated Cyp2b10 induction and reporter gene activation, without affecting CAR nuclear accumulation [50, 90]. These compounds also inhibited mCAR-mediated expression of Cyp2b10-PBREM reporter gene in HepG2 cells, where CAR constitutively resides in the nucleus. Thirdly, TCPOBOP induced translocation of hCAR in CAR-null mice but was incapable of activating a Cyp2b10-PBREM reporter gene [91]. These results argue against constitutive activation of nuclear localized CAR, and that nuclear activation represents one of the two required steps for target gene activation.

2. 2. 3 Deactivation of CAR

Intriguingly, the initial efforts in searching CAR agonists had ended up with the identification of androstane derivatives, androstanol and androstenol, as inverse agonists of mCAR [22]. Structural and functional analysis revealed that binding of androstanol to the LBD of CAR destroys actively positioned AF2 helix that is necessary for the coactivator interaction but opens up regions for accommodating the corepressor interaction [92]. Notably, these androstane derivatives compete with the known agonist TCPOBOP in cell-based CAR activation and coactivator recruitment experiments, but stimulate mCAR nuclear translocation [53], indicating the deactivation of CAR could happen at different stages of CAR activation. Thus, it is possible that different chemicals rely upon dissimilar mechanisms to deactivate the otherwise constitutively activated CAR. For instance, OA represses PB induction of CYP2B at the stage of CAR translocation, whereas it exerts synergistic inductive effects with TCPOBOP in stable cell lines constitutively expressing mCAR in the nucleus [93]. In contrast, specific CaMK inhibitors, such as KN-62, inhibit nuclear mCAR activation without affecting the nuclear translocation mechanisms [50], although there is no evidence to show whether KN-62 could directly bind to CAR.

Unlike classical NRs that are ligand activated or deactivated, studying CAR deactivation was more complicated due largely to the fact that CAR activity could be affected by both ligand-dependent and -independent pathways at multiple stages. Additionally, in vitro investigation of CAR function was affected also by the nature of cell lines to be used. CLZ was reported as the first hCAR deactivator based on cell-based reporter assay in CV-1 cells [47]. Nevertheless, the antagonistic nature of CLZ has been challenged by several subsequent studies using different cell lines, where CLZ exhibited deactivation [24, 47, 94], no effects [95], to activation of hCAR in a cell line-specific fashion [48, 96]. In another report, Huang et al. defined the widely used antiemetic meclizine as an inverse agonist for hCAR with significant agonistic effects on mCAR, indicating a single compound can induce opposite xenobiotic responses via orthologous receptors in rodents and humans [28]. More recently, PK11195, a typical peripheral benzodiazepine receptor ligand, has been identified as a selective and potent inhibitor of hCAR [49]. Compared with CLZ, which achieved the maximal deactivation of hCAR by approximately 50% of the constitutive levels in CV-1 and HepG2 cells, PK11195 inhibits the activity of hCAR by 85% in HepG2 cells [49]. Moreover, this potent inhibitory effect of PK11195 was also observed in multiple cell lines, establishing this compound as a reliable and potent hCAR deactivator. Because PK11195 has been commonly used as a diagnostic reagent in clinics, it may provide a valuable chemical tool for studying the antagonistic nature of hCAR in vivo, and help define the role of hCAR in the clinical setting.

3. Pregnane X Receptor

PXR, also named steroid X receptor (SXR) or pregnane-activated receptor (PAR), is the closest relative to the above described CAR, as they are both members of the NR1I family [97–99]. Predominantly expressed in the liver, PXR represents one of the most promiscuous receptors among the entire NR superfamily, and can be activated by a structurally diverse collection of chemicals, including both xenobiotics and endogenous chemicals [5, 100, 101]. Xenobiotic-mediated activation of PXR is associated with the induction of many target genes including major DMEs, drug transporters, and molecules governing energy homeostasis [5, 102]. Like many other orphan NRs, activation of PXR is a ligand-dependent process, requiring proper interaction with multiple coregulators, such as the SRC-1, or co-repressors, the nuclear receptor co-repressor 2 (NCoR2/SMRT) [103, 104]. PXR also shares many target genes with CAR through overlapping and distinct mechanisms, including subcellular localization and dynamic movement, which has not been extensively investigated for this receptor.

3.1 Subcellular distribution and translocation of PXR

In contrast to CAR, investigation of the cellular localization of PXR was overlooked due partly to the presumed notion that PXR persistently resides in the nucleus. The first evidence of PXR translocation came from studies in mouse liver, indicating that mouse PXR (mPXR) was predominantly localized in the cytoplasm of hepatocytes prior to activation and accumulated in the nucleus following treatment with PCN [9, 105]. Subsequent analysis in the same study, led to the identification of a typical bipartite NLS located in the DBD (66–92) of mPXR, which differs from the leucine-rich XRS of CAR located near the C-terminal within the LBD (Fig. 4B) [106]. Disruption of the NLS in the DBD shifted its distribution pattern from nucleus to both cytoplasm and nucleus [9]. Interestingly, in a separate study, Squires et al. discovered that an XRS located in the C-terminal also exists in mPXR, and site-directed mutagenesis experiments revealed that both the NLS and XRS are required for mPXR nuclear trafficking [106]. Furthermore, an mPXR-CCRP-Hsp90 complex was identified in the cytoplasm of transfected HepG2 cells as well as in mouse liver in vivo. Although both overexpression and knockdown of CCRP could alter the cellular localization of mPXR, the interaction of mPXR and CCRP does not control the nuclear translocation of mPXR in response to PCN treatment, indicating that additional factors were involved in triggering drug related mPXR translocation [106]. Most recently, Staudinger and colleagues have systematically studied the potential phosphorylation sites in the hPXR protein, and revealed that mutation of the Thr408 residual resulted in mixed distribution of hPXR between both cytoplasm and nucleus, and the mutant fails to concentrate to the nucleus after RIF treatment in CV-1 cells [107].

Compared to mPXR, limited data are available regarding the cellular localization and translocation of hPXR in a more physiologically relevant system; often these data are contradictory with that of mPXR, dictating the species-specific nature of this receptor. Previous studies in Hela, COS1 and HepG2 cells demonstrated that hPXR is localized majorly in the nucleus regardless of ligand activation [9, 108, 109]. Immunostaining experiments using HPHs also revealed predominant hPXR expression in nuclear extracts after treatment with either vehicle or rifampicin (unpublished data). Notably, overexpression of CCRP has no effects on the nuclear localized hPXR in transfected COS1 cells [106]. Nonetheless, it is important to note that regardless of whether PXR requires nuclear translocation before activation, it is clear that the receptor displays low basal activity inside the nucleus and requires direct agonist binding to exert its transcriptional activity [80, 99].

3.2 Activation of PXR

Without ligand binding, PXR acts as a gene silencer by constantly interacting with corepressors such as the silencing mediator of retinoid and thyroid receptors (SMRT) and the nuclear receptor co-repressor (NcoR) [5, 103, 110, 111]. Conversely, upon agonistic ligand binding, PXR experiences conformational changes and facilitates the recruitment of coactivators such as SRC-1, GRIP-1, PBP, and peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma coactivator-1α [13, 80, 99, 112, 113]. Interestingly, one study demonstrated that PXR differentially regulates its target genes, CYP3A4, and MDR1, in a ligand-specific manner based on differential recruitment of coactivators [114]. The ability of coactivators to direct PXR to one promoter over the other may have implications for tissue-specific gene regulation by PXR.

The extensive ligand promiscuity of PXR stems in the unique structure of its LBD. Crystallographic analysis revealed that the LBD of PXR forms a large (1280–1600 Ǻ) and flexible spherical ligand-binding packet [115, 116]. Notably, the LBD of PXR contains an extended β-sheet with five strands instead of the usual two found in other NRs, which leads to a flexible loop having the potential to expand and contract to accommodate ligands of different sizes [14, 116, 117]. The ability to accommodate ligands of different sizes and shapes results also from unique hydrogen bonding interactions in the ligand-binding cavity. Overall, these unique features of PXR provide the flexibility for the binding of ligands with different sizes, and also allow small ligands to bind multiple orientations, simultaneously.

Another nature of PXR activation comes with its capacity of interacting with diverse promoters of target genes. In the nucleus, PXR functions as a heterotetramer with RXR [118], and binds to a wide variety of response elements from different genes characterized as DR3, DR4, ER6, or ER8 motifs [79, 98, 119–121]. As such, PXR involves the transcriptional regulation of multiple CYPs, UGTs, SULTs, GSTs, certain uptake and efflux transporters, as well as aldehyde dehydrogenases and aminolevulinate synthase [5, 122, 123].

In contrast to the positive modulators, a number of antagonistic ligands of PXR have been identified with varying specificity and potency [110, 124–130]. ET-743, a marine-derived compound from the ascidian Ecetinascidia, was first reported as an effective antagonist of hPXR [125]. However, treatment of HPHs with ET-743 has resulted in repression of both PXR target and non-target genes (unpublished data). Zhou et al., recently, discovered that sulforaphane (SFN), a bioactive phytochemical found in broccoli, exhibits antagonistic features with relatively low toxicity [127]. In HPH cultures, SFN efficiently antagonizes the inductive response of rifamipicin but not that of CITCO [49, 127]. More recently, another naturally occurring compound, coumestrol was characterized also as an antagonist of hPXR [126]. Unexpectedly, mammalian two-hybrid assays showed that coumestrol was able to antagonize the recruitment of coactivators even in the PXR with mutant ligand binding cavity, indicating coumestrol may deactivate PXR at a site distinct from the putative ligand binding packet. Additionally, this study also revealed that hPXR is predominantly expressed in the nucleus of untreated humanized PXR mice, and coumestrol treatment has no significant effects on the localization of hPXR [126].

4. Aryl Hydrocarbon Receptor

AhR is a ligand-activated transcription factor of the bHLH protein of the PAS family [6]. Although it does not belong to the nuclear receptor superfamily, AhR shares many comparable characteristics with CAR and PXR as xenobiotic sensors, and mediates the toxicity of a large number of halogenated aromatic hydrocarbons and polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons, such as 2,3,7,8-tetrachlorodibenzo-p-dioxin (TCDD) and 3-methylcholanthrene, as well as clinically used drugs and endogenous chemicals such as omeprazole and bilirubin, respectively [131, 132]. In addition to the mounting list of AhR activators, the target genes of this receptor which influence xenobiotic metabolism/detoxification have also expanded from the oxidative phase I, CYP1A1, CYP1A2, and CYP1B1 to the conjugative phase II, UGT1A1, UGT1A3/1A4, UGT1A6 and, to the efflux transporter BCRP [133–139]. Similar to several xenobiotic NR family members, activation of AhR typically involves: 1) ligand-dependent nuclear translocation, 2) binding of cognate responsive elements in the promoter region of target genes; and 3) interaction with nuclear-localized coactivator and corepressors [135].

4.1 Subcellular distribution and translocation of AhR

In the cytoplasm, AhR forms a protein complex with a dimer of the Hsp90, an immunophilin-related protein, XAP2, and p23 [57, 140]. Unlike CAR and PXR, unliganded AhR was found in the cytoplasm of nearly all immortalized cell lines, indicating that the essential protein partners contained in the AhR complex are well reserved in all transformed cells. Once bound with its ligand, AhR dissociates from this cytoplasmic complex and moves into the nucleus, and turns on its target genes thereafter. Structural analysis revealed that AhR contains two characteristic structural domains: the bHLH domain which functions as a dimerization interface, and the PAS domain in the N-terminal half of the molecule [141]. The PAS domain was designated as a common region found in Drosophila Per, human aryl hydrocarbon nuclear translocator (ARNT) and Drosophila Sim, and functions as a multifunctional domain interactive with ligands, Hsp90, and ARNT [142]. Notably, AhR possesses both the functional NLS and a NES which coordinates the trafficking of AhR between the cytoplasm and nucleus (Fig. 4C) [143].

Treatment of cells with agonistic ligand of AhR such as TCDD initiates a sequence of molecular events with nuclear translocation as the first essential step for the activation of this receptor [7]. Although ligand-binding represents the major route of AhR activation, ligand-independent pathways seems also to be an alternative mechanism. Several studies reported that omeprazole translocates AhR and induces the expression of CYP1A1, the prototypical AhR target gene, without direct binding to the receptor [132, 144, 145]. Furthermore, several tyrosine kinase or casein kinase inhibitors such as genistein and daidzein inhibit omeprazole-mediated AhR activation and CYP1A1 induction, but not the TCDD-related AhR signaling [144]. Although the exact mechanism awaits further investigation, these results indicate that certain phosphorylation pathways are unique for indirect activators only.

It is interesting to note that cellular localization and activation of AhR requires appropriate cell-cell interaction in vitro. At subconfluent cell density or in suspension cultures, disruption of cell-cell contacts resulted in AhR nuclear import and activation [146]. For instance, CYP1A1 was automatically induced in suspension culture of Hepa-1 cells to the extent similar to that of TCDD treated monolayers [147]. Notably, Cho et al. reported that α-naphthoflavone, a typical antagonist of AhR inhibits TCDD, but not cell density-mediated activation of this receptor [148]. Taken together, these observations suggest that translocation of AhR involves both direct ligand binding and ligand-independent pathways through distinctive mechanisms.

4.2 Activation of AhR

The induction profiles of xenobiotic metabolism and transport are remarkably associated with XRs, such as CAR, PXR, and AhR. Although CAR and PXR share the regulation of a broad set of drug-metabolizing genes via cross-talk, AhR controls a distinct battery of genes in the same category with less overlapping (Fig. 1). On the other hand, AhR shares a number of common target genes with the Nrf2- a critical XR for electrophiles and oxidative stress [149]. Upon translocating to nucleus, AhR forms a heterodimer with the closely related ARNT and binds to the AhR-binding xenobiotic responsive elements (XREs) that have been identified in the promoter region of its target genes. To date, consensus XREs have been recognized from the promoters of CYP1A1, CYP1A2, CYP2A8, CYP19, UGT1A1, UGT1A3, UGT1A4, and UGT1A6 in varied copy numbers [134–138, 150, 151]. Remarkably, UGT1A1 can be induced by the activation of CAR, PXR, or AhR through a 290 bp module located around −3 kb of the UGT1A1 promoter, containing responsive elements for all three XRs [120, 138, 152]. In another study, Gerbal-Chaloin et al. reported that activation of PXR in HPHs converted omeprazole-sulphide, an antagonist of AhR, into omeprazole, a well known activator of AhR [153]. This fact raises the question of whether there is coordination or crosstalk between AhR and CAR/PXR in xenobiotic regulation. Indeed, activation of AhR has been shown to induce the expression of CAR in both primary hepatocytes and mice in vivo, and this induction was abrogated in AhR null mice [154]. Additionally, AhR also interacts with a number of NRs, such as the ERα, COUP-TFI, and estrogen-related receptor α [155].

5. Conclusion

The works discussed above demonstrate that nuclear translocation is an essential but not sufficient step for xenobiotic receptor-mediated induction of their target genes. The mechanisms of translocating XRs to the nucleus include prototypical ligand-binding (direct), ligand-independent phosphorylation/dephosphorylation (indirect), as well as cell density-related pathways. To date, a number of co-chaperone partners and signaling molecules associated with cytoplasmic retention of xenobiotic receptors have been uncovered. In particular, CCRP, and PPP1R16A are identified as novel partners bridging Hsp90 and CAR and controlling the subcellular distribution of CAR. Unlike PXR and AhR, CAR exhibits a unique nature of cellular localization and translocation between immortalized cells and primary cultured hepatocytes, in that CAR is sequestered in the cytoplasm of primary hepatocytes before activation and displays chemical responses and nuclear translocation only in this physiologically relevant cell system. Instead of the typical NLS, CAR utilizes a C-terminal located XRS maintaining its shuttling between the nucleus and cytoplasm. Compared to AhR and CAR, our understanding of the mechanisms regarding PXR localization/translocation is limited, particularly in respect to hPXR. Given that PXR, CAR and AhR are considered promiscuous xenobiotic sensors that translate chemical activation into coordinated metabolism, uptake, and transport processes, fully understanding the mechanism of xenobiotic receptor translocation and activation has become an intense focus of academic research efforts and may lead to enhanced prediction of drug interactions and xenobiotic-induced hepatotoxicity.

6. Expert opinion

Owing to the unique feature of CAR activation, previous identification of CAR activators in vitro, particularly in a high throughput manner, has been difficult. As a result, the numbers of CAR activators discovered up till now are relatively trivial (Table 1). To date, in vitro ligand binding assays using CLZ as a probe only offer limited value in CAR activation, due largely to the indirect activation nature of this receptor. As a matter of fact, most CAR activators identified thus far are PB-like indirect activators, emphasizing the pivotal role of nuclear translocation in the activation of CAR. Recently, Ad/EYFP-hCAR infected HPHs have been utilized as a model for discerning the association between nuclear translocation and activation of hCAR [10]. Although promising correlation of hCAR nuclear translocation with its activation has been achieved, the obviously limited accessibility of HPHs may hinder the application of this model. Alternatively, the chimeric hCAR1+A generated by Chen et al. appears responsive to a series of known hCAR activators with heightened sensitivity to both direct and indirect activators compared with hCAR3 [78]. Upon further evaluation of the chemical specificities in activation of hCAR1+A versus the reference hCAR1, this chimeric construct may represent a chemical-responsive format of hCAR for in vitro drug screening. Given the caveat that CAR exhibits unique cellular localization/translocation, direct/indirect activation, and obvious species-specific differences, more comprehensive and diligent studies are required for fully understanding the mechanisms of CAR activation.

Unlike CAR, activation of PXR relies solely on its ligand binding. Therefore, cellular localization and translocation of PXR has received little attention in the field of toxicology and pharmacology thus far. Although lack of certain cellular factors in immortalized cell lines results in automatic nuclear accumulation of transfected PXR, and hPXR seems localized predominantly within the nucleus even in the primary hepatocytes, PXR remains inactivate without ligand stimulation, independent of its localization inside or outside of the nucleus. Notably, as a xenobiotic receptor, AhR belongs to the bHLH protein of the PAS family. Xenobiotic-mediated activation of AhR also requires nuclear translocation as the initial step. Interestingly, AhR exhibits cytoplasmic localization in almost all tested cells, while nuclear translocation of this receptor could be initiated by direct or indirect pathways, reflecting similarity to the feature of CAR. Different from both CAR and PXR, AhR exhibits a high degree of evolutionary conservation among different species, suggesting that AhR plays critical roles in physiological homeostasis besides its function in toxicology and pharmacology. Overall, these three XRs orchestrate a drug metabolism/detoxification system by governing the expression of an overlapping and compensatory set of target genes. We hope that this communication will provide applicable insights into the roles of xenobiotic-driven nuclear translocation in the activation of these receptors.

Highlights Box.

-

Introduction

XRs regulate a broad set of distinct and overlapping target genes, orchestrating a defensive system in response to harmful environments.

-

Constitutive Androstane/Activated Receptor

Activation of CAR involves both direct and indirect pathways, while cytosolic retention of CAR was missing in all immortalized cell lines.

-

Pregnane X Receptor

Regardless of the localization of PXR in cytoplasm or nucleus, agonistic ligand-binding is required for the activation of this receptor.

-

Aryl Hydrocarbon Receptor

Activation of AhR is mediated through direct ligand-binding, indirect activator stimulation, or cell-cell interaction related signaling.

-

Conclusion

Nuclear accumulation is an essential but non-sufficient step for the activation of xenobiotic receptors such as CAR, PXR, and AhR.

-

Expert Opinion

The unique features of XR activation provide both opportunity and challenge for a better understanding of their pleiotropic roles in pharmacology and toxicology.

Acknowledgments

This research is supported by NIH grant DK061652.

Footnotes

Declaration of interest The authors declare no conflict of interest and have received no payment in preparation of this manuscript.

Bibliography

Papers of special note have been highlighted as either of interest (•) or of considerable interest (••) to readers.

- 1.Sonoda J, Pei L, Evans RM. Nuclear receptors: decoding metabolic disease. FEBS Lett. 2008;582(1):2–9. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2007.11.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Tzameli I, Moore DD. Role reversal: new insights from new ligands for the xenobiotic receptor CAR. Trends Endocrinol Metab. 2001;12(1):7–10. doi: 10.1016/s1043-2760(00)00332-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Nagy L, Schwabe JW. Mechanism of the nuclear receptor molecular switch. Trends Biochem Sci. 2004;29(6):317–24. doi: 10.1016/j.tibs.2004.04.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Petrick JS, Klaassen CD. Importance of hepatic induction of constitutive androstane receptor and other transcription factors that regulate xenobiotic metabolism and transport. Drug Metab Dispos. 2007;35(10):1806–15. doi: 10.1124/dmd.107.015974. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.di Masi A, Marinis ED, Ascenzi P, et al. Nuclear receptors CAR and PXR: Molecular, functional, and biomedical aspects. Mol Aspects Med. 2009;30(5):297–343. doi: 10.1016/j.mam.2009.04.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; • A recent comprehensive review of PXR and CAR structure, function and human diseases.

- 6.Burbach KM, Poland A, Bradfield CA. Cloning of the Ah-receptor cDNA reveals a distinctive ligand-activated transcription factor. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1992;89(17):8185–9. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.17.8185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ikuta T, Eguchi H, Tachibana T, et al. Nuclear localization and export signals of the human aryl hydrocarbon receptor. J Biol Chem. 1998;273(5):2895–904. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.5.2895. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kawamoto T, Sueyoshi T, Zelko I, et al. Phenobarbital-responsive nuclear translocation of the receptor CAR in induction of the CYP2B gene. Mol Cell Biol. 1999;19(9):6318–22. doi: 10.1128/mcb.19.9.6318. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; •• The first report of CAR translocation induced by activator.

- 9.Kawana K, Ikuta T, Kobayashi Y, et al. Molecular mechanism of nuclear translocation of an orphan nuclear receptor, SXR. Mol Pharmacol. 2003;63(3):524–31. doi: 10.1124/mol.63.3.524. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Li H, Chen T, Cottrell J, et al. Nuclear translocation of Ad/EYFP-hCAR: a novel tool for screening human CAR activators in human primary hepatocytes. Drug Metab Dispos. 2009 doi: 10.1124/dmd.108.026005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; • A novel tool for screening human CAR activators.

- 11.Mohan R, Heyman RA. Orphan nuclear receptor modulators. Curr Top Med Chem. 2003;3(14):1637–47. doi: 10.2174/1568026033451709. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Olefsky JM. Nuclear receptor minireview series. J Biol Chem. 2001;276(40):36863–4. doi: 10.1074/jbc.R100047200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Orans J, Teotico DG, Redinbo MR. The nuclear xenobiotic receptor pregnane X receptor: recent insights and new challenges. Mol Endocrinol. 2005;19(12):2891–900. doi: 10.1210/me.2005-0156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Watkins RE, Maglich JM, Moore LB, et al. 2.1 A crystal structure of human PXR in complex with the St. John's wort compound hyperforin. Biochemistry. 2003;42(6):1430–8. doi: 10.1021/bi0268753. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fischer U, Huber J, Boelens WC, et al. The HIV-1 Rev activation domain is a nuclear export signal that accesses an export pathway used by specific cellular RNAs. Cell. 1995;82(3):475–83. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90436-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kaffman A, O'Shea EK. Regulation of nuclear localization: a key to a door. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol. 1999;15:291–339. doi: 10.1146/annurev.cellbio.15.1.291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Baes M, Gulick T, Choi HS, et al. A new orphan member of the nuclear hormone receptor superfamily that interacts with a subset of retinoic acid response elements. Mol Cell Biol. 1994;14(3):1544–52. doi: 10.1128/mcb.14.3.1544. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; • Human CAR as a new orphan nuclear receptor was cloned.

- 18.Choi HS, Chung M, Tzameli I, et al. Differential transactivation by two isoforms of the orphan nuclear hormone receptor CAR. J Biol Chem. 1997;272(38):23565–71. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.38.23565. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Yoshinari K, Sueyoshi T, Moore R, et al. Nuclear receptor CAR as a regulatory factor for the sexually dimorphic induction of CYB2B1 gene by phenobarbital in rat livers. Mol Pharmacol. 2001;59(2):278–84. doi: 10.1124/mol.59.2.278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Honkakoski P, Zelko I, Sueyoshi T, et al. The nuclear orphan receptor CAR-retinoid X receptor heterodimer activates the phenobarbital-responsive enhancer module of the CYP2B gene. Mol Cell Biol. 1998;18(10):5652–8. doi: 10.1128/mcb.18.10.5652. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; • The first paper links the activation of CAR to the induction of drug-metabolizing enzymes.

- 21.Kanno Y, Suzuki M, Nakahama T, et al. Characterization of nuclear localization signals and cytoplasmic retention region in the nuclear receptor CAR. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2005;1745(2):215–22. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2005.06.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Forman BM, Tzameli I, Choi HS, et al. Androstane metabolites bind to and deactivate the nuclear receptor CAR-beta. Nature. 1998;395(6702):612–5. doi: 10.1038/26996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; • Identification of the reverse agonist of CAR.

- 23.Tzameli I, Pissios P, Schuetz EG, et al. The xenobiotic compound 1,4-bis[2-(3,5-dichloropyridyloxy)]benzene is an agonist ligand for the nuclear receptor CAR. Mol Cell Biol. 2000;20(9):2951–8. doi: 10.1128/mcb.20.9.2951-2958.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; • The first report of TCPOBOP as the selective mouse CAR ligand.

- 24.Maglich JM, Parks DJ, Moore LB, et al. Identification of a novel human constitutive androstane receptor (CAR) agonist and its use in the identification of CAR target genes. J Biol Chem. 2003;278(19):17277–83. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M300138200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; • Identification of CITCO as a specific human CAR ligand.

- 25.Wei P, Zhang J, Dowhan DH, et al. Specific and overlapping functions of the nuclear hormone receptors CAR and PXR in xenobiotic response. Pharmacogenomics J. 2002;2(2):117–26. doi: 10.1038/sj.tpj.6500087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sueyoshi T, Moore R, Pascussi JM, et al. Direct expression of fluorescent protein-tagged nuclear receptor CAR in mouse liver. Methods Enzymol. 2002;357:205–13. doi: 10.1016/s0076-6879(02)57680-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wang H, Faucette S, Moore R, et al. Human constitutive androstane receptor mediates induction of CYP2B6 gene expression by phenytoin. J Biol Chem. 2004;279(28):29295–301. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M400580200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Huang W, Zhang J, Wei P, et al. Meclizine is an agonist ligand for mouse constitutive androstane receptor (CAR) and an inverse agonist for human CAR. Mol Endocrinol. 2004;18(10):2402–8. doi: 10.1210/me.2004-0046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Huang W, Zhang J, Moore DD. A traditional herbal medicine enhances bilirubin clearance by activating the nuclear receptor CAR. J Clin Invest. 2004;113(1):137–43. doi: 10.1172/JCI200418385. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Burk O, Arnold KA, Nussler AK, et al. Antimalarial artemisinin drugs induce cytochrome P450 and MDR1 expression by activation of xenosensors pregnane X receptor and constitutive androstane receptor. Mol Pharmacol. 2005;67(6):1954–65. doi: 10.1124/mol.104.009019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kobayashi K, Yamanaka Y, Iwazaki N, et al. Identification of HMG-CoA reductase inhibitors as activators for human, mouse and rat constitutive androstane receptor. Drug Metab Dispos. 2005;33(7):924–9. doi: 10.1124/dmd.104.002741. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Jyrkkarinne J, Windshugel B, Makinen J, et al. Amino acids important for ligand specificity of the human constitutive androstane receptor. J Biol Chem. 2005;280(7):5960–71. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M411241200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Faucette SR, Zhang TC, Moore R, et al. Relative activation of human pregnane X receptor versus constitutive androstane receptor defines distinct classes of CYP2B6 and CYP3A4 inducers. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2007;320(1):72–80. doi: 10.1124/jpet.106.112136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kublbeck J, Jyrkkarinne J, Poso A, et al. Discovery of substituted sulfonamides and thiazolidin-4-one derivatives as agonists of human constitutive androstane receptor. Biochem Pharmacol. 2008;76(10):1288–97. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2008.08.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wei P, Zhang J, Egan-Hafley M, et al. The nuclear receptor CAR mediates specific xenobiotic induction of drug metabolism. Nature. 2000;407(6806):920–3. doi: 10.1038/35038112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kawamoto T, Kakizaki S, Yoshinari K, et al. Estrogen activation of the nuclear orphan receptor CAR (constitutive active receptor) in induction of the mouse Cyp2b10 gene. Mol Endocrinol. 2000;14(11):1897–905. doi: 10.1210/mend.14.11.0547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Zhang J, Huang W, Chua SS, et al. Modulation of acetaminophen-induced hepatotoxicity by the xenobiotic receptor CAR. Science. 2002;298(5592):422–4. doi: 10.1126/science.1073502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Makinen J, Reinisalo M, Niemi K, et al. Dual action of oestrogens on the mouse constitutive androstane receptor. Biochem J. 2003;376(Pt 2):465–72. doi: 10.1042/BJ20030553. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Huang W, Zhang J, Chua SS, et al. Induction of bilirubin clearance by the constitutive androstane receptor (CAR) Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003;100(7):4156–61. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0630614100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Murray M, Fiala-Beer E, Sutton D. Upregulation of cytochromes P450 2B in rat liver by orphenadrine. Br J Pharmacol. 2003;139(4):787–96. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0705305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Jackson JP, Ferguson SS, Moore R, et al. The constitutive active/androstane receptor regulates phenytoin induction of Cyp2c29. Mol Pharmacol. 2004;65(6):1397–404. doi: 10.1124/mol.65.6.1397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Pustylnyak VO, Gulyaeva LF, Lyakhovich VV. CAR expression and inducibility of CYP2B genes in liver of rats treated with PB-like inducers. Toxicology. 2005;216(2–3):147–53. doi: 10.1016/j.tox.2005.08.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Slitt AL, Cherrington NJ, Fisher CD, et al. Induction of genes for metabolism and transport by trans-stilbene oxide in livers of Sprague-Dawley and Wistar-Kyoto rats. Drug Metab Dispos. 2006;34(7):1190–7. doi: 10.1124/dmd.105.007542. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Fisher CD, Augustine LM, Maher JM, et al. Induction of drug-metabolizing enzymes by garlic and allyl sulfide compounds via activation of constitutive androstane receptor and nuclear factor E2-related factor 2. Drug Metab Dispos. 2007;35(6):995–1000. doi: 10.1124/dmd.106.014340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Merrell MD, Jackson JP, Augustine LM, et al. The Nrf2 activator oltipraz also activates the constitutive androstane receptor. Drug Metab Dispos. 2008;36(8):1716–21. doi: 10.1124/dmd.108.020867. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Cheng X, Klaassen CD. Perfluorocarboxylic acids induce cytochrome P450 enzymes in mouse liver through activation of PPAR-alpha and CAR transcription factors. Toxicol Sci. 2008;106(1):29–36. doi: 10.1093/toxsci/kfn147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Moore LB, Parks DJ, Jones SA, et al. Orphan nuclear receptors constitutive androstane receptor and pregnane X receptor share xenobiotic and steroid ligands. J Biol Chem. 2000;275(20):15122–7. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M001215200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Jyrkkarinne J, Makinen J, Gynther J, et al. Molecular determinants of steroid inhibition for the mouse constitutive androstane receptor. J Med Chem. 2003;46(22):4687–95. doi: 10.1021/jm030861t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Li L, Chen T, Stanton JD, et al. The peripheral benzodiazepine receptor ligand 1-(2-chlorophenyl-methylpropyl)-3-isoquinoline-carboxamide is a novel antagonist of human constitutive androstane receptor. Mol Pharmacol. 2008;74(2):443–53. doi: 10.1124/mol.108.046656. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; • Identification of a potent antagonist of human CAR.

- 50.Marc N, Galisteo M, Lagadic-Gossmann D, et al. Regulation of phenobarbital induction of the cytochrome P450 2b9/10 genes in primary mouse hepatocyte culture. Involvement of calcium- and cAMP-dependent pathways. Eur J Biochem. 2000;267(4):963–70. doi: 10.1046/j.1432-1327.2000.01083.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Kakizaki S, Yamamoto Y, Ueda A, et al. Phenobarbital induction of drug/steroidmetabolizing enzymes and nuclear receptor CAR. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2003;1619(3):239–42. doi: 10.1016/s0304-4165(02)00482-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Ding X, Staudinger JL. The ratio of constitutive androstane receptor to pregnane X receptor determines the activity of guggulsterone against the Cyp2b10 promoter. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2005;314(1):120–7. doi: 10.1124/jpet.105.085225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Guo D, Sarkar J, Suino-Powell K, et al. Induction of nuclear translocation of constitutive androstane receptor by peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor alpha synthetic ligands in mouse liver. J Biol Chem. 2007;282(50):36766–76. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M707183200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Zelko I, Sueyoshi T, Kawamoto T, et al. The peptide near the C terminus regulates receptor CAR nuclear translocation induced by xenochemicals in mouse liver. Mol Cell Biol. 2001;21(8):2838–46. doi: 10.1128/MCB.21.8.2838-2846.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Hache RJ, Tse R, Reich T, et al. Nucleocytoplasmic trafficking of steroid-free glucocorticoid receptor. J Biol Chem. 1999;274(3):1432–9. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.3.1432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Rowlands JC, Gustafsson JA. Aryl hydrocarbon receptor-mediated signal transduction. Crit Rev Toxicol. 1997;27(2):109–34. doi: 10.3109/10408449709021615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Kazlauskas A, Sundstrom S, Poellinger L, et al. The hsp90 chaperone complex regulates intracellular localization of the dioxin receptor. Mol Cell Biol. 2001;21(7):2594–607. doi: 10.1128/MCB.21.7.2594-2607.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Tai PK, Albers MW, Chang H, et al. Association of a 59-kilodalton immunophilin with the glucocorticoid receptor complex. Science. 1992;256(5061):1315–8. doi: 10.1126/science.1376003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Kobayashi K, Sueyoshi T, Inoue K, et al. Cytoplasmic accumulation of the nuclear receptor CAR by a tetratricopeptide repeat protein in HepG2 cells. Mol Pharmacol. 2003;64(5):1069–75. doi: 10.1124/mol.64.5.1069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; •• This paper demonstrated CCRP as a cytoplasmic chaperon protein of CAR.

- 60.Sueyoshi T, Moore R, Sugatani J, et al. PPP1R16A, the membrane subunit of protein phosphatase 1beta, signals nuclear translocation of the nuclear receptor constitutive active/androstane receptor. Mol Pharmacol. 2008;73(4):1113–21. doi: 10.1124/mol.107.042960. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Yoshinari K, Kobayashi K, Moore R, et al. Identification of the nuclear receptor CAR:HSP90 complex in mouse liver and recruitment of protein phosphatase 2A in response to phenobarbital. FEBS Lett. 2003;548(1–3):17–20. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(03)00720-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Kanno Y, Suzuki M, Miyazaki Y, et al. Difference in nucleocytoplasmic shuttling sequences of rat and human constitutive active/androstane receptor. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2007;1773(6):934–44. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2007.03.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Koike C, Moore R, Negishi M. Localization of the nuclear receptor CAR at the cell membrane of mouse liver. FEBS Lett. 2005;579(30):6733–6. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2005.10.070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Min G, Kemper JK, Kemper B. Glucocorticoid receptor-interacting protein 1 mediates ligand-independent nuclear translocation and activation of constitutive androstane receptor in vivo. J Biol Chem. 2002;277(29):26356–63. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M200051200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Guo D, Sarkar J, Ahmed MR, et al. Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor (PPAR)-binding protein (PBP) but not PPAR-interacting protein (PRIP) is required for nuclear translocation of constitutive androstane receptor in mouse liver. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2006;347(2):485–95. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2006.06.129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Moore LB, Maglich JM, McKee DD, et al. Pregnane X receptor (PXR), constitutive androstane receptor (CAR), and benzoate X receptor (BXR) define three pharmacologically distinct classes of nuclear receptors. Mol Endocrinol. 2002;16(5):977–86. doi: 10.1210/mend.16.5.0828. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Ueda A, Hamadeh HK, Webb HK, et al. Diverse roles of the nuclear orphan receptor CAR in regulating hepatic genes in response to phenobarbital. Mol Pharmacol. 2002;61(1):1–6. doi: 10.1124/mol.61.1.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Xiong H, Yoshinari K, Brouwer KL, et al. Role of constitutive androstane receptor in the in vivo induction of Mrp3 and CYP2B1/2 by phenobarbital. Drug Metab Dispos. 2002;30(8):918–23. doi: 10.1124/dmd.30.8.918. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Xie W, Barwick JL, Downes M, et al. Humanized xenobiotic response in mice expressing nuclear receptor SXR. Nature. 2000;406(6794):435–9. doi: 10.1038/35019116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; • The first report of humanized PXR mice.

- 70.Barwick JL, Quattrochi LC, Mills AS, et al. Trans-species gene transfer for analysis of glucocorticoid-inducible transcriptional activation of transiently expressed human CYP3A4 and rabbit CYP3A6 in primary cultures of adult rat and rabbit hepatocytes. Mol Pharmacol. 1996;50(1):10–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Arnold KA, Eichelbaum M, Burk O. Alternative splicing affects the function and tissue-specific expression of the human constitutive androstane receptor. Nucl Recept. 2004;2(1):1. doi: 10.1186/1478-1336-2-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Auerbach SS, Ramsden R, Stoner MA, et al. Alternatively spliced isoforms of the human constitutive androstane receptor. Nucleic Acids Res. 2003;31(12):3194–207. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkg419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Lamba JK, Lamba V, Yasuda K, et al. Expression of constitutive androstane receptor splice variants in human tissues and their functional consequences. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2004;311(2):811–21. doi: 10.1124/jpet.104.069310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Savkur RS, Wu Y, Bramlett KS, et al. Alternative splicing within the ligand binding domain of the human constitutive androstane receptor. Mol Genet Metab. 2003;80(1–2):216–26. doi: 10.1016/j.ymgme.2003.08.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Jinno H, Tanaka-Kagawa T, Hanioka N, et al. Identification of novel alternative splice variants of human constitutive androstane receptor and characterization of their expression in the liver. Mol Pharmacol. 2004;65(3):496–502. doi: 10.1124/mol.65.3.496. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.DeKeyser JG, Stagliano MC, Auerbach SS, et al. Di(2-ethylhexyl) phthalate is a highly potent agonist for the human constitutive androstane receptor splice variant CAR2. Mol Pharmacol. 2009;75(5):1005–13. doi: 10.1124/mol.108.053702. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Auerbach SS, Stoner MA, Su S, et al. Retinoid X receptor-alpha-dependent transactivation by a naturally occurring structural variant of human constitutive androstane receptor (NR1I3) Mol Pharmacol. 2005;68(5):1239–53. doi: 10.1124/mol.105.013417. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Chen T, Tompkins LM, Li L, et al. A single amino acid controls the functional switch of human constitutive androstane receptor (CAR) 1 to the xenobiotic-sensitive splicing variant CAR3. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2010;332(1):106–15. doi: 10.1124/jpet.109.159210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Xie W, Barwick JL, Simon CM, et al. Reciprocal activation of xenobiotic response genes by nuclear receptors SXR/PXR and CAR. Genes Dev. 2000;14(23):3014–23. doi: 10.1101/gad.846800. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Lehmann JM, McKee DD, Watson MA, et al. The human orphan nuclear receptor PXR is activated by compounds that regulate CYP3A4 gene expression and cause drug interactions. J Clin Invest. 1998;102(5):1016–23. doi: 10.1172/JCI3703. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Faucette SR, Sueyoshi T, Smith CM, et al. Differential regulation of hepatic CYP2B6 and CYP3A4 genes by constitutive androstane receptor but not pregnane X receptor. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2006;317(3):1200–9. doi: 10.1124/jpet.105.098160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Roy P, Yu LJ, Crespi CL, et al. Development of a substrate-activity based approach to identify the major human liver P-450 catalysts of cyclophosphamide and ifosfamide activation based on cDNA-expressed activities and liver microsomal P-450 profiles. Drug Metab Dispos. 1999;27(6):655–66. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Schwartz PS, Chen CS, Waxman DJ. Sustained P450 expression and prodrug activation in bolus cyclophosphamide-treated cultured tumor cells. Impact of prodrug schedule on P450 gene-directed enzyme prodrug therapy. Cancer Gene Ther. 2003;10(8):571–82. doi: 10.1038/sj.cgt.7700601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Xu RX, Lambert MH, Wisely BB, et al. A structural basis for constitutive activity in the human CAR/RXRalpha heterodimer. Mol Cell. 2004;16(6):919–28. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2004.11.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Sueyoshi T, Negishi M. Phenobarbital response elements of cytochrome P450 genes and nuclear receptors. Annu Rev Pharmacol Toxicol. 2001;41:123–43. doi: 10.1146/annurev.pharmtox.41.1.123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Kodama S, Negishi M. Phenobarbital confers its diverse effects by activating the orphan nuclear receptor car. Drug Metab Rev. 2006;38(1–2):75–87. doi: 10.1080/03602530600569851. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Hosseinpour F, Moore R, Negishi M, et al. Serine 202 regulates the nuclear translocation of constitutive active/androstane receptor. Mol Pharmacol. 2006;69(4):1095–102. doi: 10.1124/mol.105.019505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Rencurel F, Foretz M, Kaufmann MR, et al. Stimulation of AMP-activated protein kinase is essential for the induction of drug metabolizing enzymes by phenobarbital in human and mouse liver. Mol Pharmacol. 2006;70(6):1925–34. doi: 10.1124/mol.106.029421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Rencurel F, Stenhouse A, Hawley SA, et al. AMP-activated protein kinase mediates phenobarbital induction of CYP2B gene expression in hepatocytes and a newly derived human hepatoma cell line. J Biol Chem. 2005;280(6):4367–73. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M412711200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Zelko I, Negishi M. Phenobarbital-elicited activation of nuclear receptor CAR in induction of cytochrome P450 genes. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2000;277(1):1–6. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.2000.3557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Honkakoski P, Sueyoshi T, Negishi M. Drug-activated nuclear receptors CAR and PXR. Ann Med. 2003;35(3):172–82. doi: 10.1080/07853890310008224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Suino K, Peng L, Reynolds R, et al. The nuclear xenobiotic receptor CAR: structural determinants of constitutive activation and heterodimerization. Mol Cell. 2004;16(6):893–905. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2004.11.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Swales K, Kakizaki S, Yamamoto Y, et al. Novel CAR-mediated mechanism for synergistic activation of two distinct elements within the human cytochrome P450 2B6 gene in HepG2 cells. J Biol Chem. 2005;280(5):3458–66. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M411318200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Lempiainen H, Molnar F, Macias Gonzalez M, et al. Antagonist- and inverse agonist-driven interactions of the vitamin D receptor and the constitutive androstane receptor with corepressor protein. Mol Endocrinol. 2005;19(9):2258–72. doi: 10.1210/me.2004-0534. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Toell A, Kroncke KD, Kleinert H, et al. Orphan nuclear receptor binding site in the human inducible nitric oxide synthase promoter mediates responsiveness to steroid and xenobiotic ligands. J Cell Biochem. 2002;85(1):72–82. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Simonsson US, Lindell M, Raffalli-Mathieu F, et al. In vivo and mechanistic evidence of nuclear receptor CAR induction by artemisinin. Eur J Clin Invest. 2006;36(9):647–53. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2362.2006.01700.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Bertilsson G, Heidrich J, Svensson K, et al. Identification of a human nuclear receptor defines a new signaling pathway for CYP3A induction. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1998;95(21):12208–13. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.21.12208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]