Abstract

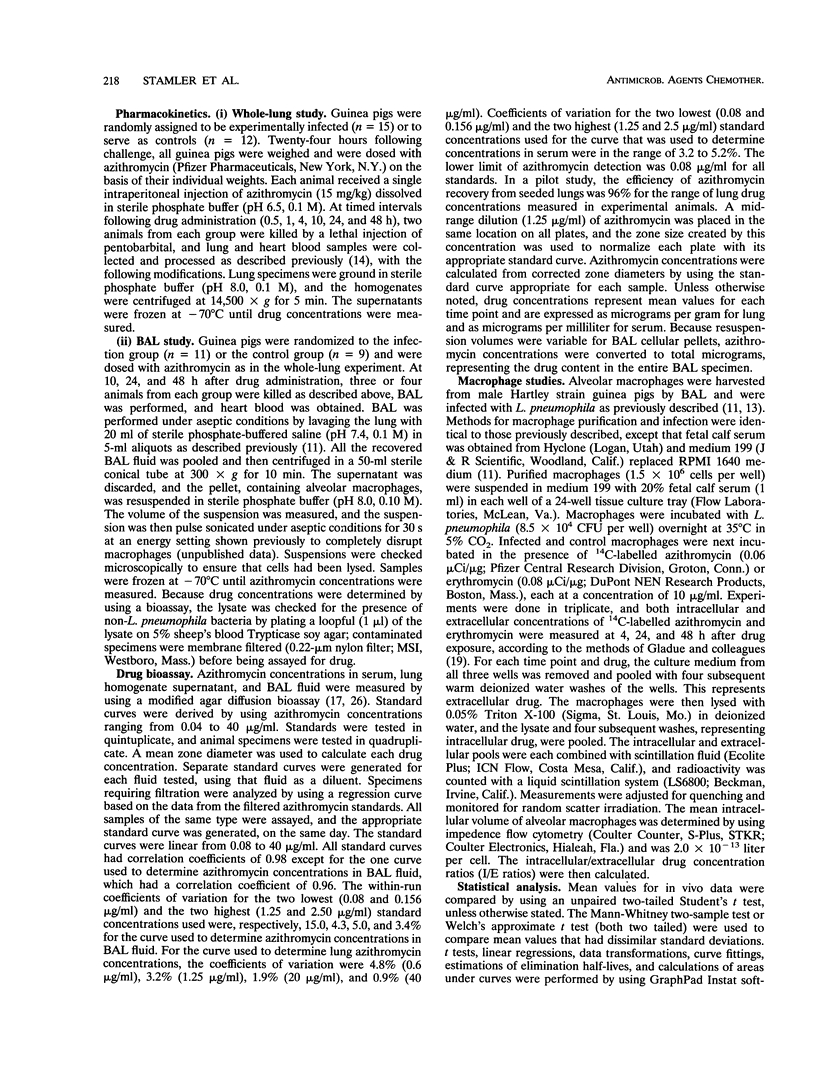

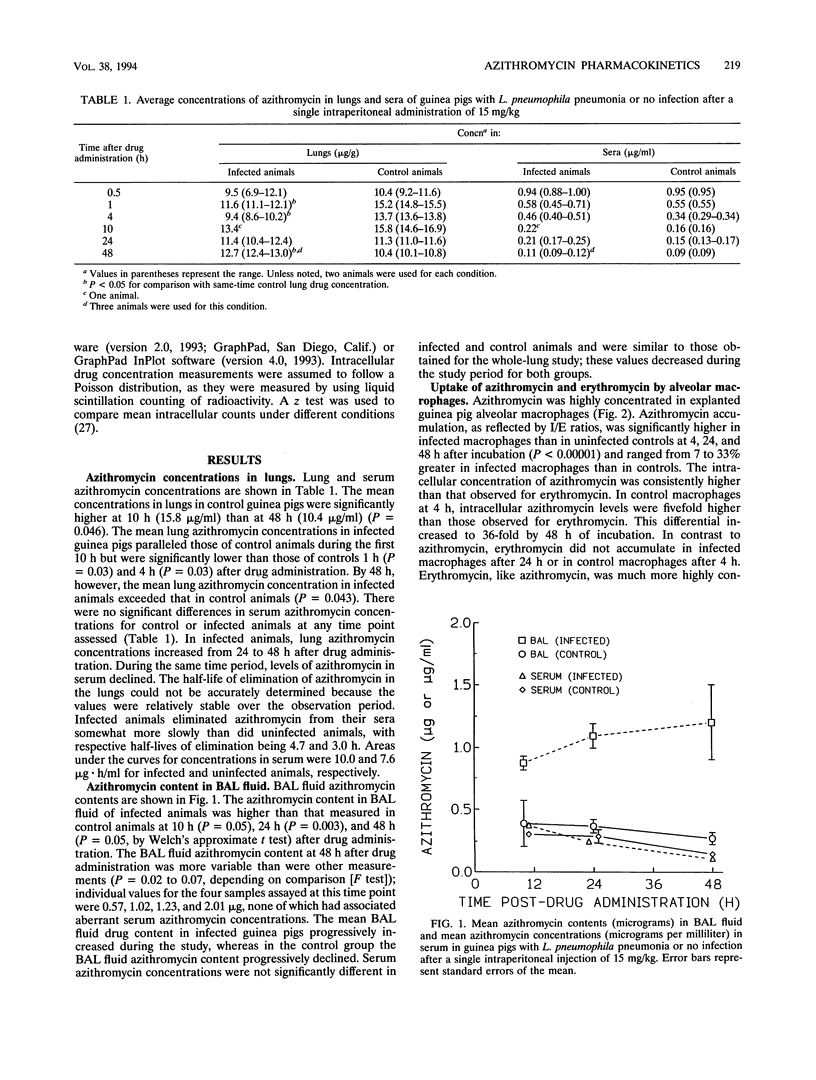

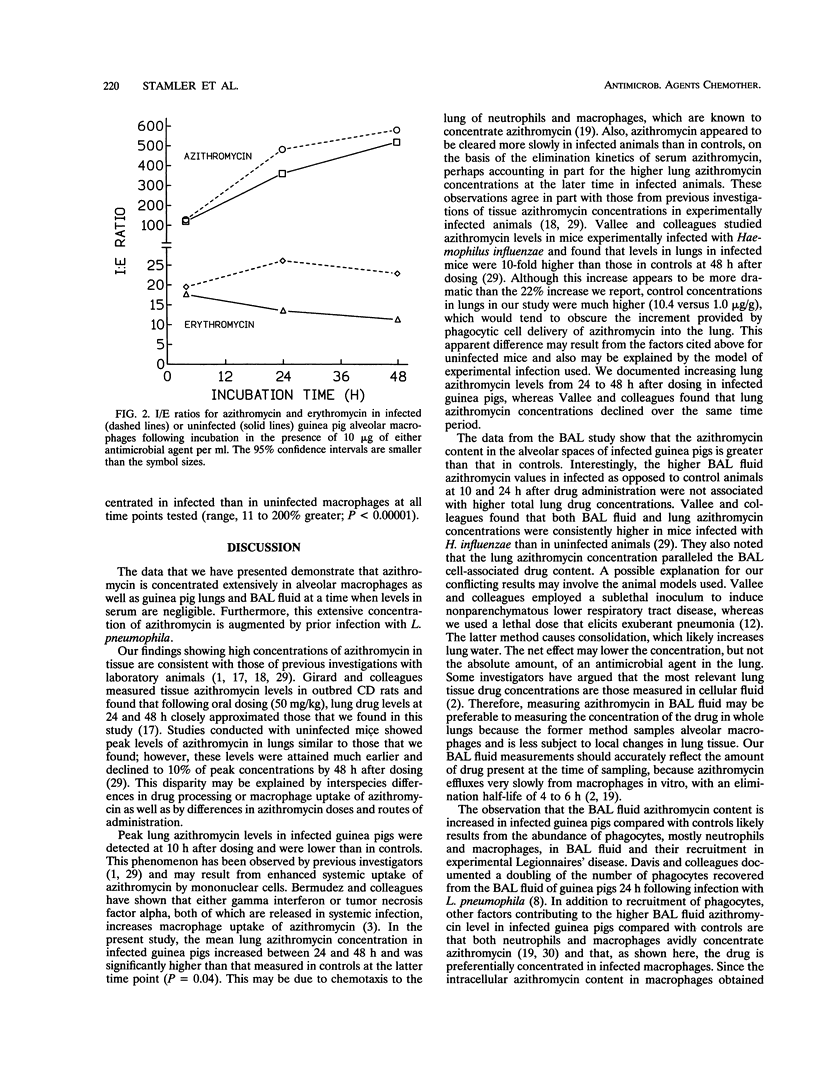

Azithromycin pharmacokinetics in Legionella pneumophila-infected and uninfected guinea pigs were assessed by measuring the drug concentration in whole lungs or the drug content in bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL) fluid in separate experiments. Azithromycin concentrations were measured by using a bioassay. The mean azithromycin content in the BAL fluid of infected guinea pigs was higher than that in controls at 10 h (0.87 versus 0.39 microgram; P = 0.05), 24 h (1.10 versus 0.37 microgram; P = 0.003), and 48 h (1.21 versus 0.28 microgram; P = 0.05) after a single intraperitoneal injection of drug (15 mg/kg). The mean peak lung azithromycin concentration was higher in control animals than in infected animals (15.8 versus 13.4 micrograms/ml). The mean lung azithromycin concentration in infected animals was significantly higher than that in controls 48 h after dosing (12.7 versus 10.4 micrograms/g; P = 0.04). There were no significant differences between infected and uninfected animals in serum azithromycin levels. Complementary experiments assessed intracellular/extracellular concentration ratios of azithromycin and erythromycin in L. pneumophila-infected and control guinea pig alveolar macrophages. Azithromycin was highly concentrated in alveolar macrophages, and the intracellular/extracellular concentration ratios for infected cells were significantly higher (P < 0.0001) than those observed in controls after 4 h (127 versus 119), 24 h (481 versus 361), and 48 h (582 versus 520) of incubation. Erythromycin was also preferentially concentrated in infected cells (P < 0.0001). AZ intracellular concentrations were at least fivefold higher than those measured for erythromycin, and this differential increased with incubation time. Thus, azithromycin recovery from BAL fluid, and from guinea pig lungs at the 48-h time point, was higher in the presence of experimental Legionnaires' disease. This likely results from recruitment of phagocytes, including macrophages, that have an enhanced capacity to highly concentrate the drug.

Full text

PDF

Selected References

These references are in PubMed. This may not be the complete list of references from this article.

- Azoulay-Dupuis E., Vallée E., Bedos J. P., Muffat-Joly M., Pocidalo J. J. Prophylactic and therapeutic activities of azithromycin in a mouse model of pneumococcal pneumonia. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1991 Jun;35(6):1024–1028. doi: 10.1128/aac.35.6.1024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baldwin D. R., Honeybourne D., Wise R. Pulmonary disposition of antimicrobial agents: methodological considerations. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1992 Jun;36(6):1171–1175. doi: 10.1128/aac.36.6.1171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bermudez L. E., Inderlied C., Young L. S. Stimulation with cytokines enhances penetration of azithromycin into human macrophages. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1991 Dec;35(12):2625–2629. doi: 10.1128/aac.35.12.2625. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bright G. M., Nagel A. A., Bordner J., Desai K. A., Dibrino J. N., Nowakowska J., Vincent L., Watrous R. M., Sciavolino F. C., English A. R. Synthesis, in vitro and in vivo activity of novel 9-deoxo-9a-AZA-9a-homoerythromycin A derivatives; a new class of macrolide antibiotics, the azalides. J Antibiot (Tokyo) 1988 Aug;41(8):1029–1047. doi: 10.7164/antibiotics.41.1029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carlier M. B., Scorneaux B., Zenebergh A., Desnottes J. F., Tulkens P. M. Cellular uptake, localization and activity of fluoroquinolones in uninfected and infected macrophages. J Antimicrob Chemother. 1990 Oct;26 (Suppl B):27–39. doi: 10.1093/jac/26.suppl_b.27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carlier M. B., Zenebergh A., Tulkens P. M. Cellular uptake and subcellular distribution of roxithromycin and erythromycin in phagocytic cells. J Antimicrob Chemother. 1987 Nov;20 (Suppl B):47–56. doi: 10.1093/jac/20.suppl_b.47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cooper M. A., Nye K., Andrews J. M., Wise R. The pharmacokinetics and inflammatory fluid penetration of orally administered azithromycin. J Antimicrob Chemother. 1990 Oct;26(4):533–538. doi: 10.1093/jac/26.4.533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis G. S., Winn W. C., Jr, Gump D. W., Beaty H. N. The kinetics of early inflammatory events during experimental pneumonia due to Legionella pneumophila in guinea pigs. J Infect Dis. 1983 Nov;148(5):823–835. doi: 10.1093/infdis/148.5.823. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edelstein P. H., Beer K. B., DeBoynton E. D. Influence of growth temperature on virulence of Legionella pneumophila. Infect Immun. 1987 Nov;55(11):2701–2705. doi: 10.1128/iai.55.11.2701-2705.1987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edelstein P. H., Calarco K., Yasui V. K. Antimicrobial therapy of experimentally induced Legionnaires' disease in guinea pigs. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1984 Nov;130(5):849–856. doi: 10.1164/arrd.1984.130.5.849. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edelstein P. H., Edelstein M. A. WIN 57273 is bactericidal for Legionella pneumophila grown in alveolar macrophages. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1989 Dec;33(12):2132–2136. doi: 10.1128/aac.33.12.2132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edelstein P. H., Edelstein M. A., Weidenfeld J., Dorr M. B. In vitro activity of sparfloxacin (CI-978; AT-4140) for clinical Legionella isolates, pharmacokinetics in guinea pigs, and use to treat guinea pigs with L. pneumophila pneumonia. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1990 Nov;34(11):2122–2127. doi: 10.1128/aac.34.11.2122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fitzgeorge R. B., Featherstone A. S., Baskerville A. Efficacy of azithromycin in the treatment of guinea pigs infected with Legionella pneumophila by aerosol. J Antimicrob Chemother. 1990 Jan;25 (Suppl A):101–108. doi: 10.1093/jac/25.suppl_a.101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foulds G., Shepard R. M., Johnson R. B. The pharmacokinetics of azithromycin in human serum and tissues. J Antimicrob Chemother. 1990 Jan;25 (Suppl A):73–82. doi: 10.1093/jac/25.suppl_a.73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Girard A. E., Girard D., English A. R., Gootz T. D., Cimochowski C. R., Faiella J. A., Haskell S. L., Retsema J. A. Pharmacokinetic and in vivo studies with azithromycin (CP-62,993), a new macrolide with an extended half-life and excellent tissue distribution. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1987 Dec;31(12):1948–1954. doi: 10.1128/aac.31.12.1948. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Girard A. E., Girard D., Retsema J. A. Correlation of the extravascular pharmacokinetics of azithromycin with in-vivo efficacy in models of localized infection. J Antimicrob Chemother. 1990 Jan;25 (Suppl A):61–71. doi: 10.1093/jac/25.suppl_a.61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gladue R. P., Bright G. M., Isaacson R. E., Newborg M. F. In vitro and in vivo uptake of azithromycin (CP-62,993) by phagocytic cells: possible mechanism of delivery and release at sites of infection. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1989 Mar;33(3):277–282. doi: 10.1128/aac.33.3.277. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kirst H. A., Sides G. D. New directions for macrolide antibiotics: structural modifications and in vitro activity. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1989 Sep;33(9):1413–1418. doi: 10.1128/aac.33.9.1413. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peters D. H., Friedel H. A., McTavish D. Azithromycin. A review of its antimicrobial activity, pharmacokinetic properties and clinical efficacy. Drugs. 1992 Nov;44(5):750–799. doi: 10.2165/00003495-199244050-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Retsema J., Girard A., Schelkly W., Manousos M., Anderson M., Bright G., Borovoy R., Brennan L., Mason R. Spectrum and mode of action of azithromycin (CP-62,993), a new 15-membered-ring macrolide with improved potency against gram-negative organisms. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1987 Dec;31(12):1939–1947. doi: 10.1128/aac.31.12.1939. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simon H. J., Yin E. J. Microbioassay of antimicrobial agents. Appl Microbiol. 1970 Apr;19(4):573–579. doi: 10.1128/am.19.4.573-579.1970. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steinman R. M., Brodie S. E., Cohn Z. A. Membrane flow during pinocytosis. A stereologic analysis. J Cell Biol. 1976 Mar;68(3):665–687. doi: 10.1083/jcb.68.3.665. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vallée E., Azoulay-Dupuis E., Pocidalo J. J., Bergogne-Bérézin E. Activity and local delivery of azithromycin in a mouse model of Haemophilus influenzae lung infection. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1992 Jul;36(7):1412–1417. doi: 10.1128/aac.36.7.1412. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wildfeuer A., Laufen H., Müller-Wening D., Haferkamp O. Interaction of azithromycin and human phagocytic cells. Uptake of the antibiotic and the effect on the survival of ingested bacteria in phagocytes. Arzneimittelforschung. 1989 Jul;39(7):755–758. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams J. D. Spectrum of activity of azithromycin. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 1991 Oct;10(10):813–820. doi: 10.1007/BF01975833. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Duve C., de Barsy T., Poole B., Trouet A., Tulkens P., Van Hoof F. Commentary. Lysosomotropic agents. Biochem Pharmacol. 1974 Sep 15;23(18):2495–2531. doi: 10.1016/0006-2952(74)90174-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]