Summary

Red rice, a major agricultural weed, is phenotypically diverse and possesses traits that are similar to both wild and cultivated rice. The genetic resources available for rice make it possible to examine the molecular basis and evolution of traits characterizing this weed. Here, we assess the phenol reaction – a classical trait for distinguishing among cultivated rice varieties – in red rice at the phenotypic and molecular levels.

We phenotyped more than 100 US weed samples for the phenol reaction and sequenced the underlying Phr1 locus in a subset of samples. Data were analyzed in combination with previously published Phr1 data for cultivated rice.

Most weed accessions (96.3%) are positive for the phenol reaction, and samples with a negative response carry loss-of-function alleles that are rare or heretofore undocumented. One such allele may have evolved through mutational convergence of a 1-bp frameshift insertion. Haplotype sharing between red rice and US cultivars suggests occasional crop–weed hybridization.

Our discovery of previously undocumented nonfunctional phr1 alleles suggests that there are likely to be other loss-of-function mutations segregating in Oryza sativa around the world. Red rice may provide a useful study system for understanding the adaptive significance of Phr1 variation in agricultural settings.

Keywords: crop, weed hybridization, phenol reaction, Phr1, polyphenol oxidase, red rice (Oryza sativa), weedy crop relatives, weed evolution

Introduction

Weeds that are closely related to crops offer useful study systems for examining both weed evolution and the evolution of plants in human-mediated environments. This is particularly true when the genetic resources available for an economically important crop can be leveraged to unravel the genetic basis and evolutionary history of weed-adaptive traits. Such is the case for red rice (Oryza sativa), which infests rice fields around the world (Suh et al., 1997). Red rice is one of the most pervasive and destructive weeds of rice fields in the USA (Smith, 1988), which is one of the top five rice exporters in the world (Childs & Burdett, 2000). Estimates indicate that red rice in the USA causes crop losses exceeding $45 million annually (Gealy et al., 2002). The severe economic impact of red rice has resulted in considerable interest in the origin and evolution of this conspecific weed (Diarra et al., 1985; Vaughan et al., 2001; Londo & Schaal, 2007), yet questions remain about its evolutionary history and its relationship to cultivated and wild Oryza species.

In the USA, red rice is most prevalent in the southern Mississippi valley, which is the primary region of North American rice cultivation. The weed is phenotypically diverse, with strains varying widely in the degree to which they show characteristics typical of wild Oryza species (for example, tall stature, freely shattering grains, dark-pigmented hulls, long awns), or traits that are more crop-like (for example, short stature, reduced shattering, straw-colored hulls lacking awns) (Diarra et al., 1985; Noldin et al., 1999). Nearly all US red rice grains have proanthocyanidin-pigmented pericarps, a characteristic of wild Oryza species (and the source of the weed's common name). Unlike wild species, however, the weed is predominantly self-fertilizing, has an upright growth habit and persists solely in agricultural fields (Diarra et al., 1985; Noldin et al., 1999; Gealy et al., 2003). On the basis of the hull characteristics and their resemblance to cultivated or wild Oryza species, US red rice has been typically classified into two phenotypic categories: blackhull awned (BHA) and strawhull awnless (SH) strains.

The evolutionary origins of US red rice remain to be fully resolved. However, genome-wide assessments of neutral genetic variation have indicated a close relationship between US red rice and Asian crop varieties that have never been cultivated in North America. In particular, SH strains show close genetic similarity to indica cultivated rice varieties, and BHA strains show similarity to aus rice (a minor variety group related to indica) (Londo & Schaal, 2007; M. Reagon et al., Univ. Massachusetts, Amherst, unpublished). Cultivated rice in the southern USA, by contrast, is exclusively of the genetically distinct tropical japonica variety group (Mackill & McKenzie, 2003; Lu et al., 2005). As there are no wild Oryza species native to North America, these patterns suggest that red rice became established in the USA following accidental introductions of indica- and aus-like germplasm from Asia.

Although there has been substantial interest in the classification of US red rice strains as either wild- or crop-like (Noldin et al., 1999; Arrieta-Espinoza et al., 2005), little emphasis has been placed on examining the phenotypic variation within the weed as it relates to the traits used in describing cultivated rice varieties. Traditionally, two major variety groups or subspecies have been recognized within the crop: indica rice (including the related aus varieties) and japonica rice. These two variety groups are the result of two independent domestication events from the wild progenitor O. rufipogon (Londo et al., 2006; Caicedo et al., 2007), and are distinguishable at a suite of classical diagnostic traits, including: seedling resistance to KClO3, seedling survival in cold temperatures, grain apiculus hair length and phenol reaction (Oka, 1953, 1958; Oka & Chang, 1961; see also Morishima et al., 1992). The phenol reaction describes whether rice hulls and grains darken after exposure to a 1–2% aqueous phenol solution; japonica varieties show no color change (a negative response), whereas indica varieties and wild Oryza species take on a dark brown or black coloration as a result of polyphenol oxidase (PPO) activity (a positive response). Given the genetic similarity of red rice to indica (and aus) varieties, one might expect weed strains to show indica-like characteristics for the phenol reaction and the other classical diagnostic characters. However, the extent to which this is true, and the extent to which weed strains are variable for these traits, have not been examined systematically.

Recently, the gene underlying the phenol reaction has been cloned and characterized in O. sativa (Yu et al., 2008). The phenol-negative response characterizing japonica varieties was shown to be the result of three different loss-of-function mutations at the Phr1 locus, which encodes the PPO enzyme (a protein in the tyrosinase family). The majority of japonica lines sequenced to date contain an 18-bp deletion in exon 3 that results in a nonfunctional (phr1) allele; a minority have either a 29-bp deletion in exon 3 or a 1-bp insertion in exon 1, which also result in nonfunctional alleles and negative phenol reactions. Patterns of nucleotide variation at Phr1 are consistent with positive selection favoring the widespread 18-bp deletion allele in japonica rice (Yu et al., 2008). It has been suggested that this selection was imposed during domestication because a lack of PPO activity may prevent grain discoloration during storage (Yu et al., 2008). The reason why nonfunctional phr1 alleles were not also selectively favored in indica rice remains unclear; this could potentially reflect countervailing selection favoring PPO activity in the tropical and subtropical climates where indica varieties are grown, possibly associated with selection for enhanced disease resistance and/or seed dormancy (Yu et al., 2008).

The recent molecular characterization of the phenol reaction in cultivated rice provides an opportunity to assess this classical diagnostic character in populations of red rice. In this study, we survey the phenol response in US red rice strains; moreover, we directly examine the molecular genetic basis of phenol reaction variation in the weeds, and how this variation corresponds to Phr1 mutations previously characterized in the crop. Despite an a priori expectation that all US weed strains would possess indica-like functional Phr1 alleles, we instead found evidence of multiple loss-of-function alleles in the weed. This candidate gene-based analysis of the weed's phenotypic diversity provides a powerful complement to neutral genetic markers for assessing the origin of red rice and ongoing evolutionary dynamics.

Materials and Methods

Samples and phenotyping

Samples for phenotyping consisted of 108 red rice (Oryza sativa L.) accessions collected from throughout the southern US rice-growing region (Missouri, Arkansas, Louisiana and Texas) and spanning the morphological diversity present in the US weed, including SH and BHA types, intermediates between these weedy forms and samples that appeared to be crop–weed hybrids based on morphological assessment (Table S1, see Supporting Information). These samples were collected from rice fields, and then propagated in field plots at the US Department of Agriculture (USDA) Dale Bumpers National Rice Research Center, Stuttgart, AR, USA. All red rice samples were kindly provided by Dr David Gealy. Both cultivated rice and red rice are predominantly self-fertilizing, and weed strains were isolated by a minimum of 3 ft in field plots to minimize any possibility of accidental outcrossing; outcrossing rates for red rice are estimated to be less than 0.03%, even for plants growing immediately next to each other (D. Gealy, USDA, pers. comm.). Any morphological ‘offtypes’ in propagation field plots were rogued to further minimize any chance of including outcrossed genotypes in the sample set (D. Gealy, USDA, pers. comm.).

Grains, with hulls intact, were soaked in a 1.5% unbuffered aqueous phenol solution for 48 h, dried and then compared with untreated grains from the same samples to assess color change. One positive control (Rathuwee, an indica cultivar) and one negative control (Delitus, a tropical japonica cultivar grown in the USA) were included in all phenotyping. The Rathuwee sample was obtained from the International Rice Research Institute (IRRI) (IRGC accession #8952) and the Delitus sample was obtained from the USDA (CIor accession #1206). Any samples showing a negative response were phenotyped at least twice to verify the phenol reaction.

Molecular methods

A subset of the phenotyped red rice accessions (23 samples), including all samples with negative phenol reactions and one US crop variety (Delitus), was selected for sequencing of the Phr1 locus. DNA was extracted from glasshouse-grown material using a modified cetyltrimethylammonium bromide (CTAB) technique (see Methods S1 for a detailed description, Supporting Information).

Phr1 was amplified using a combination of the primer pairs ppo_001, ppo_002, ppo_102, ppo_103 and ppo_104. Primer pairs ppo_102, ppo_103 and ppo_104 are identical to published primers from Yu et al. (2008); the alternative names for these primers and the sequences for all primers are provided in Table S2 (see Supporting Information). PCRs were performed in volumes of 13 μl for ppo_001, ppo_002 and ppo_104 and in volumes of 25 μl for ppo_102 and ppo_103. All PCRs contained concentrations of 1 × GoTaq® Flexi Buffer (Promega), 2 mm MgCl2, 0.2 mm deoxynucleoside triphosphates (dNTPs) and 0.8 mm of each primer. Both volumes of PCR contained 2 ng of DNA; 13 μl reactions contained 0.0625 μl and 25 μl reactions contained 0.125 μl of GoTaq® Flexi DNA Polymerase (Promega). PCR cycling conditions varied by primer (see Methods S1 for detailed descriptions).

Sequencing reactions were performed in volumes of 10 μl containing 20–30 ng of PCR product per 1000 bp of fragment length. Fragments were sequenced using the same primers as used for amplification. Sequencing reactions contained concentrations of 0.32 μm primer, 80 mm Tris-HCl, 2 mm MgCl2 and 1.0 μl BigDye Terminator v3.1 (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA, USA). An initial denaturing cycle of 1 min at 94°C was followed by 25 cycles of 10 s at 96°C, 5 s at 50°C and 4 min at 60°C. Sequences were separated on an ABI 3130 capillary sequencer at the Washington University Biology Department core facility. GenBank accession numbers for the sequenced regions are GQ121703–GQ121726.

The complete or nearly complete sequence of Phr1 was obtained for the Delitus US crop cultivar and 14 of the red rice accessions. Nonspecific priming and amplification precluded the entire sequence from being obtained for the remaining nine samples, and so only 1891 bp of the 2345 bp sequence was obtained (consisting of exon 2, intron 2 and exon 3). The sequence from exon 2 to exon 3 alone was informative for the identification of two of the three previously documented loss-of-function mutations resulting in a negative phenol reaction, as both the 18-bp deletion [responsible for the majority of negative reactions in the study by Yu et al. (2008)] and the 29-bp deletion (the second most common loss-of-function mutation in that study) are located in exon 3.

For cultivated rice, only the Delitus US crop sample was included initially in the sequenced samples. This sampling strategy was based on the assumption that the previous survey of Phr1 variation in japonica cultivars (Yu et al., 2008) would have documented most or all of the loss-of-function alleles in the genetically restricted tropical japonica variety group (Garris et al., 2005; Lu et al., 2005). However, the appearance of previously unidentified loss-of-function mutations in the US weed (see Results) prompted the inclusion of three additional US cultivars: Carolina Gold (PI 636345), Palmyra (CIor 9463) and CL121 (a Clearfield™ herbicide-resistant strain, closely related to Cocodrie). Fragment ppo_103, which spanned the known loss-of-function mutations in exon 3, was amplified and sequenced in these three additional cultivated rice samples.

Molecular data analysis

Sequence editing and alignment were performed using the PHRED, PHRAP and Polyphred programs (Deborah Nickerson, University of Washington, Seattle, WA, USA) and BioLign Version 4.0.6 (Tom Hall, North Carolina State University, Raleigh, NC, USA). The majority of individuals were homozygous, consistent with the predominantly selfing mating system that characterizes both weedy and domesticated rice; one sequence was heterozygous for a single 1-bp indel, and so alleles were phased manually by comparing forward and reverse sequences at variable sites. One of the two inferred haplotypes was selected randomly for inclusion in the population genetic dataset and the other was discarded because the germplasm had been generated via selfing in a controlled setting and the allele frequencies were not representative of natural populations. This dataset was combined with an additional 58 Phr1 sequences published by Yu et al. (2008) and downloaded from GenBank (accessions DQ532375–DQ532432), including eight indica, 14 japonica, 32 O. rufipogon/O. nivara and one each of O. alta, O. barthii, O. glaberrima and O. officinalis.

Nei's (1982) γST genetic distance between groups and net sequence divergence (Da) were calculated as measures of genetic differentiation for the Phr1 locus. Da controls for the amount of within-group sequence variation by subtracting the average within-group diversity from the total divergence between populations. Levels of nucleotide diversity per silent site (π) and Tajima's (1989) D statistic were calculated using DNAsp 4.50.1 (Rozas et al., 2003). These population genetic measures were calculated for several different groups or combinations of sequences to compensate for potentially unrepresentative sampling (for example, the fact that phenol-negative samples were sequenced preferentially), as follows. First, sequences from phenol-positive and phenol-negative samples were analyzed as separate groups. Second, for heterozygotes in the previously published dataset, analyses were performed with both sequences included and with one allele from each heterozygous individual randomly discarded (results were nearly the same for both calculations, and so, unless otherwise stated, results in the paper represent the latter treatment).

Neighbor-joining trees (Saitou & Nei, 1987) based on the 14 complete or nearly complete Phr1 sequences from red rice and the single fully sequenced US cultivar, combined with the sequences from GenBank, were generated using Phylip (Felsenstein, 1993) with bootstrap values calculated via 1000 replicates of the data.

Results

Four of the 108 accessions of US red rice (3.7%) showed a negative phenol reaction. The phenol-negative accessions were USDA samples RR20, RR97, RR98 and RR102, all of which are SH phenotypes (Table S1). The remaining 104 accessions (96.3%) showed at least a slight darkening after exposure to phenol solution, and so were considered to have a positive phenol reaction. Most of these samples showed a striking color change after exposure to phenol solution; fewer than 30 had a variable or weak reaction necessitating re-testing.

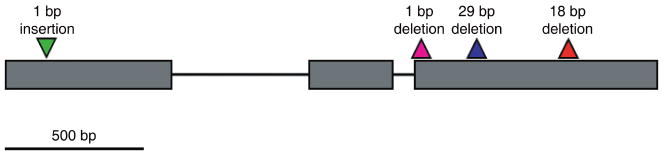

Complete or nearly complete Phr1 sequences (missing less than 65 bp of a total length of 2345 bp) were obtained for 14 of the 23 sequenced samples, and sequences of exon 2 to exon 3 (1891 bp) were obtained for the remaining nine accessions. Two of the four weed accessions with negative phenol reactions (RR20, RR97) contained the 1-bp insertion in Phr1 exon 1 that has been previously documented in one japonica cultivar (Yu et al., 2008) (Fig. 1). One phenol-negative accession (RR98) contained a heretofore undocumented 1-bp deletion in exon 3, which is predicted to result in a frameshift mutation and premature stop codons (Fig. 1); this accession contained no other mutations predicted to cause a frameshift or deletion of amino acids in the translated sequence. The fourth phenol-negative weed accession (RR102) did not contain any identifiable insertions or deletions, although only the final 1891 bp of the 2345-bp length could be successfully sequenced for this individual; thus, it is possible that there are one or more loss-of-function mutations in the unsequenced exon 1. The US cultivar Delitus, a tropical japonica variety, contained the previously identified 29-bp deletion. Of the US cultivars for which only a portion of exon 3 was sequenced, both Carolina Gold and Palmyra also contained the 29-bp deletion, whereas CL121 contained the previously undocumented 1-bp deletion observed in weed strain RR98.

Fig. 1.

Schematic diagram of sequenced regions of the Phr1 locus. Exons are shown as rectangles and introns are shown as connecting lines. Locations of insertions and deletions resulting in loss-of-function mutations are shown above the exons. The 1-bp deletion in exon 3 was newly documented in this study. Shading corresponds to the branches in Fig. 2. Distances are approximately to scale.

Analyses of previously published Phr1 sequences from cultivated rice and the wild progenitor O. rufipogon (Yu et al., 2008) indicated that total and silent site nucleotide diversities (π) were fairly high for the progenitor and for indica varieties compared with the genome-wide silent-site averages reported previously (Table 1). For example, the average genome-wide nucleotide diversity for O. rufipogon at silent sites has been reported to be 0.0052 (Caicedo et al., 2007), whereas at the Phr1 locus it is 0.011. In comparison, levels of Phr1 silent site nucleotide diversity in the japonica variety group or any set of alleles sharing a particular Phr1 loss-of-function mutation were much lower, ranging from 0.0051 (for japonica) to 0.0016 (for alleles with the 18-bp deletion). Levels of nucleotide diversity at the Phr1 locus in red rice accessions (using the 14 full-length sequences) were higher than in japonica varieties, but lower than both indica varieties and O. rufipogon. Tajima's D statistic was not statistically significant for any group of red rice alleles tested. The weed strains were least differentiated from O. rufipogon and indica, followed by japonica, based on both γST and Da (Table 2).

Table 1.

Average pairwise nucleotide diversity (π) for total sites and silent sites per 1000 bases at the Phr1 locus

| Phr1 locus | ||

|---|---|---|

| π (total) per kb | π (silent) per kb | |

| Oryza rufipogon (30) | 6.13 | 11.20 |

| All Oryza sativa (22) | 4.28 | 8.24 |

| indica (8) | 6.05 | 11.91 |

| positive (7) | 6.04 | 11.94 |

| japonica (15) | 2.80 | 5.05 |

| 1-bp insertion (3)1 | 2.05 | 2.98 |

| 18-bp deletion (15)1 | 1.21 | 1.63 |

| 29-bp deletion (6)1 | 1.27 | 2.22 |

| US weedy (14)2 | 2.99 | 6.33 |

| positive (19)3 | 2.93 | 5.81 |

| negative (4)3 | 1.52 | 3.17 |

Numbers in parentheses indicate the number of alleles included in the analysis.

All alleles showing this mutation, including Oryza rufipogon, O. sativa and weedy samples.

14 full-length sequences only.

Contains full-length and truncated sequences.

Table 2.

Percentage net sequence divergence (Da) between groups (above diagonal) and γST genetic distances between groups (below diagonal) for the Phr1 locus

| Oryza rufipogon | indica | japonica | US weedy | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Oryza rufipogon | 0.061 | 0.073 | 0.074 | |

| indica | 0.05723 | 0.089 | 0.123 | |

| japonica | 0.07764 | 0.15191 | 0.177 | |

| US weedy | 0.06852 | 0.13624 | 0.21742 |

The US weedy group contains all sequenced samples.

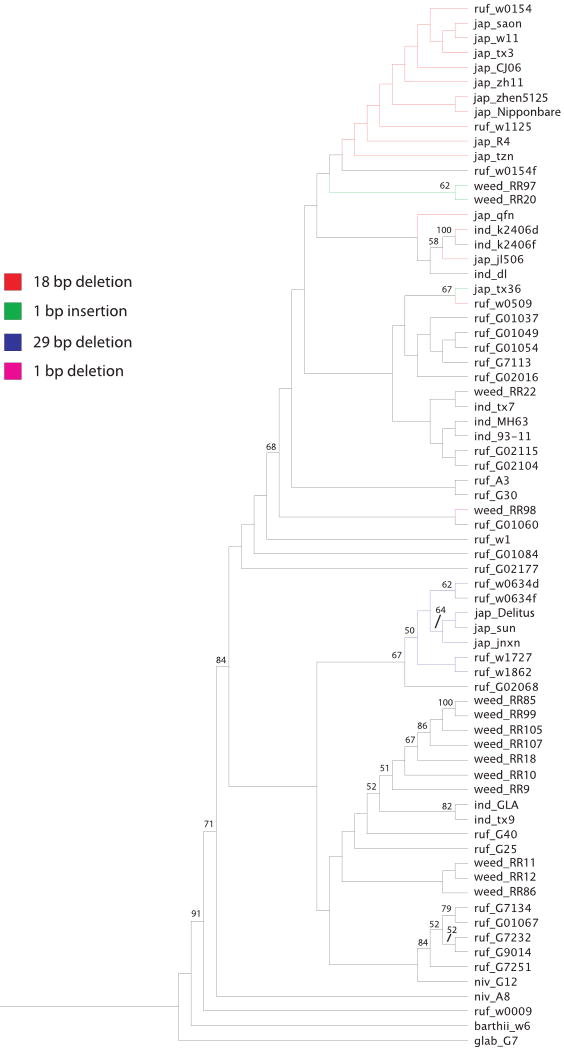

The neighbor-joining distance analysis reveals that sequences with the 29-bp deletion form one cluster and those with the 18-bp deletion and 1-bp insertion fall out within a separate cluster (Fig. 2); this pattern corresponds well with the previous analysis of Phr1 alleles in domesticated rice (Yu et al., 2008), with only minor differences in areas of poor bootstrap support. Bootstrap values were low in both the present and previous study, as would be expected for a relatively short locus in the context of closely related taxa. Of the 14 full-length red rice sequences included in the tree, three were phenol negative and the remaining 11 were phenol positive. Of the samples with positive phenol reactions, 10 fell out in the same large cluster containing indica cultivars and O. rufipogon accessions, and one (RR22) fell out in a separate cluster that also included indica and O. rufipogon samples. The relationships between these weed accessions and the other samples on the tree are generally consistent with previous results from genome-wide surveys of variation using neutral molecular markers (microsatellites and sequences); these studies indicate that US weed strains are closely related to indica cultivated varieties, aus cultivated varieties (a minor variety group related to indica) and/or the crop's wild progenitor O. rufipogon (Londo & Schaal, 2007; M. Reagon et al., Univ. Massachusetts, Amherst, unpublished).

Fig. 2.

Neighbor-joining tree for Phr1 haplotypes using the majority-rule, extended method of consensus tree construction. Bootstrap values indicate nodes with at least 50% support based on 1000 bootstrap replicates of the data. Alleles with loss-of-function mutations are shown in color according to the key; all other alleles are shown in black.

The three phenol-negative weed samples included in the neighbor-joining analysis do not group with the weed samples showing a positive phenol reaction. Two of these accessions, both of which have a 1-bp insertion in exon 1 (RR20, RR97), group most closely with japonica and O. rufipogon samples carrying the common 18-bp deletion – they are not grouped with the japonica accession with the same 1-bp insertion (Tx36; see Fig. 2). This pattern potentially suggests an independent mutational origin of this 1-bp loss-of-function mutation in two separate haplotypes. The lack of clustering among haplotypes carrying the 1-bp insertion does not appear to be an artifact of low variation; the two weed samples differ from the Tx36 accession at seven nucleotide sites, where the total number of segregating sites in all of the weedy samples combined is only 20. The third sequenced phenol-negative weed accession on the tree (RR98) groups most closely with an O. rufipogon accession (from which it differs at only one site) and does not cluster closely with any other samples with negative phenol reactions. It is important to note that the sampling of red rice accessions for sequencing was not random, as phenol-negative plants were specifically targeted. Additional sequencing of both phenol-negative and phenol-positive weeds would be required to draw definitive conclusions about the overall haplotype relationships within red rice.

Discussion

Over one-half of the world's 12 most important crops have conspecific or closely related weeds (Ellstrand et al., 1999). These weeds present a unique problem for agricultural production, as their similarity to crops makes them especially difficult to detect and eradicate. However, conspecific weeds can also offer a fascinating study system for evolutionary biologists. In the red rice system, available genomic resources make it possible to unravel the genetic basis of traits that characterize the weedy form, which provides insights into weed evolution and also the relationships between weedy, domesticated and wild forms of rice. In this study, we have documented both the distribution of a classical diagnostic phenotype, the phenol reaction, and its molecular genetic basis in US red rice. In so doing, we have identified a new, nonfunctional phr1 allele that apparently contributes to the negative phenol reaction; we have further identified the potential for multiple mutational origins of a previously documented loss-of-function mutation.

The genetic basis of the phenol reaction

The phenol reaction is one of the hallmark traits that differentiate the two major variety groups of domesticated rice: japonica varieties are negative for the phenol reaction, whereas indica varieties (as well as wild Oryza species) are positive (Oka, 1953, 1958; Oka & Chang, 1961). Because genome-wide surveys of genetic variation of US red rice have shown that SH and BHA weeds are genetically similar to the indica variety group (or to the closely related aus varieties) (Londo & Schaal, 2007; Reagon et al., unpublished), one might predict that all US weed accessions would also be positive for the phenol reaction. Although this was true for the majority of the samples in our analysis (96.3%), four of the 108 samples (3.7%) were negative for the phenol reaction. There are two possibilities for the occurrence of a negative phenol reaction in these weedy accessions: loss-of-function mutations at Phr1 that have arisen de novo in red rice; or hybridization and introgression into the weed from phenol-negative cultivated varieties (japonica rice), a group that includes all US cultivars. Two lines of evidence suggest that the latter explanation is most likely. First, all four of these samples (RR20, RR97, RR98, RR102) were identified as putative crop–weed hybrids when they were initially collected, based on morphological characteristics (see Table S1). In addition, a genome-wide assessment of nucleotide variation has been performed on a sample of red rice accessions, including three of the four phenol-negative genotypes documented here (RR20, RR98, RR102); these accessions stand out in the analyses in showing genomic compositions indicating that they are likely to be crop–weed hybrids (Reagon et al., unpublished). Thus, it is very likely that the Phr1 haplotypes observed in these strains originated through introgression from US cultivated rice.

The rice grown in the southern USA is exclusively of the tropical japonica variety group, which comprises a relatively narrow gene pool within O. sativa (Lu et al., 2005). Nonetheless, even with very restricted sampling (four US cultivars in total), we observed two different Phr1 loss-of-function mutations in the crop (the 29-bp deletion and a previously undocumented 1-bp deletion in exon 3), neither of which is the common 18-bp loss-of-function mutation observed in the previous study by Yu et al. (2008). As noted by the authors of that study, their sampling scheme may not necessarily be representative of O. sativa samples worldwide; 89% of the phenol-negative cultivars examined in that study were collected in China, and the degree of genetic relatedness among these samples is unknown. Given our findings in the present study, it seems likely that there are as yet unidentified loss-of-function phr1 alleles segregating in japonica cultivars, in both the USA and around the world.

This inference that there are likely to be multiple loss-of-function alleles in the US crop is further bolstered by our finding of a novel haplotype within the phenol-negative US weed strains. As noted above, the weed strains are likely to have acquired the loss-of-function alleles primarily through crop–weed hybridization. Nonetheless, two of the four phenol-negative weed strains (RR20 and RR97) carry a Phr1 haplotype not yet documented in any crop varieties, in either the study by Yu et al. (2008) or in the present study. More extensive sampling of US cultivars could confirm whether this novel, weed-specific, loss-of-function haplotype is in fact shared with US crop varieties.

The haplotype in RR20 and RR97 is also interesting in that the putative causal mutation that it carries, a 1-bp frameshift insertion in exon 1, is shared with a previously reported but genetically distinct haplotype. This other haplotype, documented in a single japonica cultivar, Tx36 (Yu et al., 2008), differs from the weed-specific haplotype at seven nucleotide sites, and the two haplotypes are not grouped together on the neighbor-joining tree (Fig. 2). There are two potential explanations for the presence of the same loss-of-function mutation in these two genealogically distinct haplotypes. One possibility is that the same loss-of-function mutation has evolved twice independently in different genetic backgrounds. Alternatively, the 1-bp insertion could have evolved a single time, with subsequent intragenic recombination accounting for the presence of this mutation in genetically divergent haplotypes. Indeed, recombination was cited as a possible basis for the origin of the 1-bp insertion allele in Tx36, given its close relationship to haplotypes with the 18-bp deletion mutation (Yu et al., 2008). If the RR20 and RR97 alleles are the product of a recombination event, the fact that they are almost identical to other alleles in the dataset makes this difficult to detect. The Tx36 allele, however, is identical to O. rufipogon ruf_w0509 at positions 1–1284, downstream of which it does not perfectly match any haplotype in the dataset, although it differs from ruf_G01054 at only two sites for the rest of the sequence. Thus, Tx36 could be the product of recombination with one of the alleles in the dataset, followed by mutation; or it could have arisen via recombination with a potential ‘donor’ that has not been included in the present survey. Thorough, geographically extensive sampling of Phr1 alleles could potentially provide more information on the role of intragenic recombination in the origin of these haplotypes.

The other previously undocumented loss-of-function haplotype detected in this study contains a 1-bp frameshift deletion within exon 3 (Fig. 1). We observed this haplotype in the phenol-negative weed accession RR98 and in the US crop cultivar CL121. It is interesting to note that CL121 is a herbicide-resistant cultivar. Herbicide-resistant rice varieties have been grown in the USA since the early 2000s, and the cultivation of these varieties is now the primary means of combating red rice infestations. Because the acquisition of herbicide resistance would be under very strong positive selection in red rice populations, genetic introgression from herbicide-resistant cultivars into weeds would be expected to be especially strongly favored. The Phr1 locus and the locus contributing to herbicide resistance in CL121 are on different chromosomes, however, so that physical linkage to herbicide resistance is not a probable explanation for the presence of nonfunctional phr1 alleles in the weed.

Origin and evolution of US red rice

Patterns of genetic differentiation at the Phr1 locus are similar to those at neutral loci, in that the weed is least differentiated from O. rufipogon and indica varieties and most differentiated from japonica varieties (Table 2) (Londo & Schaal, 2007; Reagon et al., unpublished). This pattern corresponds with the current hypothesis that the SH weed is derived either directly from indica cultivated varieties or from hybrid derivatives of crop-by-wild crosses. In addition, as discussed above, there are signs of gene flow between the weed and the US crop despite genome-wide differentiation between the weed and japonica cultivars (Langevin et al., 1990; Gealy et al., 2002; Londo & Schaal, 2007; Shivrain et al., 2007; Reagon et al., unpublished). The potential for gene flow from crops into related weeds is of great interest for management purposes (Langevin et al., 1990; Whitton et al., 1997; Gealy et al., 2002, 2003; Ellstrand, 2003; Chen et al., 2004; Messeguer et al., 2004; Lu & Snow, 2005; Morrell et al., 2005; Campbell et al., 2006; Shivrain et al., 2007; Warwick et al., 2008), and so information on the frequency and persistence of crop alleles in the weed is useful in this context, as well as for understanding the potential for adaptive introgression in this system.

The level of nucleotide diversity at the Phr1 locus is high compared with genome-wide silent site averages. For example, the average silent site diversity for japonica based on genome-wide averages is 0.00147 (Caicedo et al., 2007), whereas at the Phr1 locus, it is 0.00505. It is only when the alleles with the 18-bp deletion [which were probably under positive selection during domestication; Yu et al. (2008)] are considered as an independent group that levels of nucleotide diversity fall to close to the genome-wide average at 0.00163. For the weed strains, Phr1 silent site nucleotide diversity is higher than for japonica cultivated varieties, with levels at 0.00633 for silent sites, although this value is still lower than the silent site nucleotide diversity in indica varieties, where it is 0.0119 (Table 1). One might expect the US weed to have higher diversity than the japonica crop variety at the Phr1 locus, given evidence of positive selection on Phr1 in the japonica cultivated variety group. However, genome-wide nucleotide diversity assessments indicate that the US weed has likely undergone a severe genetic bottleneck with its introduction into the USA, resulting in levels of diversity equal to or lower than that found in domesticated rice (M. Reagon et al., Univ. Massachusetts, Amherst, unpublished).

The evolution of Phr1 in agricultural environments

Red rice provides a complementary system to cultivated rice for understanding the potential adaptive significance of Phr1 variation in agricultural settings. For cultivated rice, Phr1 sequence variation shows patterns consistent with selection by humans for multiple loss-of-function mutations in the japonica variety group; this has been proposed to reflect selection during domestication for grains that do not become discolored by PPO activity during long-term storage (Yu et al., 2008). The absence of nonfunctional phr1 alleles in indica rice has been proposed to potentially reflect countervailing selection for PPO-associated disease resistance and/or enhanced seed dormancy (preventing premature seed germination) in the tropical and subtropical climates in which indica varieties are grown (Yu et al., 2008; see also Thipyapong et al., 1995; Li & Steffens, 2002). For the case of red rice, the US weed strains are nearly, but not entirely, fixed for functional Phr1 alleles. Two different explanations could account for this pattern.

One possibility is that PPO activity is of no selective value in the US agricultural setting, but that the energetic costs to PPO production are small and loss-of-function mutations have not spread in the weed because of the relatively short time available for the appearance of new mutations or widespread introgression from the crop. The fact that US cultivars (all tropical japonica) grow successfully without PPO activity suggests that the climate of the southern USA does not strongly favor functional Phr1 alleles. However, all of the phenol-negative weed strains detected here are probable recent crop–weed hybrids (Table S1; M. Reagon et al., Univ. Massachusetts, Amherst, unpublished), which suggests that nonfunctional phr1 alleles may not be able to persist over multiple generations in the North American weed populations.

An alternative explanation is that PPO activity in North American agricultural settings is a specifically weed-adaptive trait. Among the traits most strongly favored in weed populations is seed dormancy. Although the genetic basis of seed dormancy in Oryza is not fully understood, it is clear that dormancy is controlled by covering tissues (Gu et al., 2005), including either the hull or the pericarp, both of which are sites of Phr1 expression (Yu et al., 2008). Therefore, it is possible that Phr1 plays some role in enforcing seed dormancy, in which case there may be selection to maintain a functional allele in the weed. Additional information from other weedy rice populations around the world will provide opportunities to examine whether a functional Phr1 allele is necessary in some environments but not others.

Conclusions

This investigation of the phenotypic and molecular genetic variation of a classical diagnostic trait in US red rice provides information about the relationship of the US weed to possible progenitors and the occurrence of gene flow between the US weed and the crop. In addition, this study demonstrates how the study of conspecific weeds can contribute to our understanding of crop evolution. In the case of US red rice, documenting Phr1 allelic variation in the weed has led to the discovery of a new loss-of-function allele in domesticated rice and the possible independent origin of a previously documented mutation. More broadly, red rice provides a system independent from selectively bred crops for understanding the evolution of Phr1 functionality in agricultural settings. Conspecific crop weeds represent an under-utilized resource available for the evaluation of the phenotypic and molecular evolution of plants in human-mediated environments.

Supplementary Material

Methods S1 Details of protocols for DNA extraction, PCR cycling conditions and amplicon purification.

Table S1 Accession numbers, hull colors or cultivar names, species names, variety groups, phenol reaction responses, origins and probable hybrid status (based on morphology) or release dates for accessions used in this study

Table S2 Primer sequences used to amplify and sequence the Phr1 locus

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr David Gealy (USDA) for providing the red rice samples used in this study. This manuscript was improved by the helpful comments of the Olsen laboratory group, J. L. Strasburg and two anonymous reviewers. This study was supported by a National Science Foundation PGRP award (DBI-0638820) to K.M.O. B.L.G. was supported by a National Institutes of Health Ruth L. Kirschstein Postdoctoral Fellowship (1F32GM082165). K.J.S. was supported by a Summer Undergraduate Research Fellowship funded by an Undergraduate Biological Sciences Education Program grant from the Howard Hughes Medical Institute to Washington University in St. Louis.

Footnotes

Supporting Information: Additional supporting information may be found in the online version of this article.

Please note: Wiley-Blackwell are not responsible for the content or functionality of any supporting information supplied by the authors. Any queries (other than missing material) should be directed to the New Phytologist Central Office.

References

- Arrieta-Espinoza G, Sánchez E, Vargas S, Lobo J, Quesada T, Espinoza AM. The weedy rice complex in Costa Rica. I. Morphological study of relationships between commercial rice varieties, wild Oryza relatives and weedy types. Genetic Resources and Crop Evolution. 2005;52:575–587. [Google Scholar]

- Caicedo A, Williamson S, Hernandez RD, Boyko A, Fledel-Alon A, York T, Polato N, Olsen K, Nielsen R, McCouch SR, et al. Genome-wide patterns of nucleotide polymorphism in domesticated rice. PLoS Genetics. 2007;3:e163. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.0030163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campbell LG, Snow AA, Ridley CE. Weed evolution after crop gene introgression: greater survival and fecundity of hybrids in a new environment. Ecology Letters. 2006;9:1198–1209. doi: 10.1111/j.1461-0248.2006.00974.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen LJ, Lee DS, Song ZP, Suh HS, Lu BR. Gene flow from cultivated rice (Oryza sativa) to its weedy and wild relatives. Annals of Botany. 2004;93:67–73. doi: 10.1093/aob/mch006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Childs N, Burdett A. Rice situation and outlook: the U.S. rice export market. Economic Research Service/USDA. 2000:48–54. November 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Diarra A, Smith RJ, Jr, Talbert RE. Growth and morphological characteristics of red rice (Oryza sativa) biotypes. Weed Science. 1985;33:310–314. [Google Scholar]

- Ellstrand NC. Dangerous liaisons? When cultivated plants mate with their wild relatives. Baltimore, MA, USA: Johns Hopkins University Press; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Ellstrand NC, Prentice HC, Hancock JF. Gene flow and introgression from domesticated plants into their wild relatives. Annual Review of Ecology and Systematics. 1999;30:539–563. [Google Scholar]

- Felsenstein J. PHYLIP (Phylogeny Inference Package) version 3.5c. Department of Genetics, University of Washington; Seattle, WA, USA: 1993. Distributed by the author. [Google Scholar]

- Garris AJ, Tai TH, Coburn J, Kresovich S, McCouch S. Genetic structure and diversity in Oryza sativa L. Genetics. 2005;169:1631–1638. doi: 10.1534/genetics.104.035642. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gealy DR, Mitten DH, Rutger JN. Gene flow between red rice (Oryza sativa) and herbicide-resistant rice (O. sativa): implications for weed management. Weed Technology. 2003;17:627–645. [Google Scholar]

- Gealy DR, Tai TH, Sneller CH. Identification of red rice, rice, and hybrid populations using microsatellite markers. Weed Science. 2002;50:333–339. [Google Scholar]

- Gu XY, Kianian SF, Foley ME. Seed dormancy imposed by covering tissues interrelates to shattering and seed morphological characteristics in weedy rice. Crop Science. 2005;45:948–955. [Google Scholar]

- Langevin SA, Clay K, Grace JB. The incidence and effects of hybridization between cultivated rice and its related weed red rice (Oryza sativa L.) Evolution. 1990;44:1000–1008. doi: 10.1111/j.1558-5646.1990.tb03820.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li L, Steffens J. Overexpression of polyphenol oxidase in transgenic tomato plants results in enhanced bacterial disease resistance. Planta. 2002;215:239–247. doi: 10.1007/s00425-002-0750-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Londo JP, Chiang YC, Hung KH, Chiang TY, Schaal BA. Phylogeography of Asian wild rice, Oryza rufipogon, reveals multiple independent domestication of cultivated rice Oryza sativa. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, USA. 2006;103:9578–9583. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0603152103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Londo JP, Schaal BA. Origins and population genetics of weedy red rice in the USA. Molecular Ecology. 2007;16:4523–4535. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-294X.2007.03489.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu BR, Snow AA. Gene flow from genetically modified rice and its environmental consequences. BioScience. 2005;55:669–678. [Google Scholar]

- Lu H, Redus MA, Coburn JR, Rutger JN, McCouch SR, Tai TH. Population structure and breeding patterns of 145 U.S. rice cultivars based on SSR marker analysis. Crop Science. 2005;45:66–76. [Google Scholar]

- Mackill DJ, McKenzie KS. Origin and characteristics of U.S. rice cultivars. In: Smith CW, editor. Rice: origin, history, technology, and production. Hoboken, NJ, USA: John Wiley & Sons, Inc.; 2003. pp. 87–100. [Google Scholar]

- Messeguer J, Marfà V, Català MM, Guiderdoni E, Melé E. A field study of pollen-mediated gene flow from Mediterranean GM rice to conventional rice and the red rice weed. Molecular Breeding. 2004;13:103–112. [Google Scholar]

- Morishima H, Sano Y, Oka HI. Evolutionary studies in cultivated rice and its wild relatives. In: Futuyma DJ, Antonovics J, editors. Oxford surveys in evolutionary biology: Volume 8. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press; 1992. pp. 135–184. [Google Scholar]

- Morrell PL, Williams-Coplin TD, Lattu AL, Bowers JE, Chandler JM, Paterson AH. Crop-to-weed introgression has impacted allelic composition of johnsongrass populations with and without recent exposure to cultivated sorghum. Molecular Ecology. 2005;14:2143–2154. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-294X.2005.02579.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nei M. Evolution of human races at the gene level. In: Bonne-Tamir B, Cohen T, Goodman RM, editors. Human genetics, part A: The unfolding genome. New York, NY, USA: Alan R Liss Press; 1982. pp. 167–181. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Noldin JA, Chandler JM, McCauley GN. Red rice (Oryza sativa) biology. I. Characterization of red rice ecotypes. Weed Technology. 1999;13:12–18. [Google Scholar]

- Oka HI. Phylogenetic differentiation of the cultivated rice plant. 1. Variations in respective characteristics and their combinations in rice cultivars. Japanese Journal of Breeding. 1953;3:33–43. [Google Scholar]

- Oka HI. Intervarietal variation and classification of cultivated rice. Indian Journal of Genetics & Plant Breeding. 1958;18:79–89. [Google Scholar]

- Oka HI, Chang WT. Hybrid swarms between wild and cultivated rice species, Oryza perennis and O. sativa. Evolution. 1961;15:418–430. [Google Scholar]

- Rozas J, Sanchez-DelBarrio JC, Messeguer X, Rozas R. DnaSP, DNA polymorphism analyses by the coalescent and other methods. Bioinformatics. 2003;19:2496–2497. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btg359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saitou N, Nei M. The neighbor-joining method: a new method for reconstructing phylogenetic trees. Molecular Biology and Evolution. 1987;4:406–426. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.molbev.a040454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shivrain VK, Burgos NR, Anders MM, Rajguru SN, Moore J, Sales MA. Gene flow between Clearfield(tm) rice and red rice. Crop Protection. 2007;26:349–356. [Google Scholar]

- Smith RJ., Jr Weed thresholds in Southern U.S. rice, Oryza sativa. Weed Technology. 1988;2:232–241. [Google Scholar]

- Suh HS, Sato YI, Morishima H. Genetic characterization of weedy rice (Oryza sativa L.) based on morpho-physiology, isozymes and RAPD markers. Theoretical and Applied Genetics. 1997;94:316–321. [Google Scholar]

- Sweeney MT, Thomson MJ, Cho YG, Park YJ, Williamson SH, Bustamante CD, McCouch SR. Global dissemination of a single mutation conferring white pericarp in rice. PLoS Genetics. 2007;3:e133. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.0030133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sweeney MT, Thomson MJ, Pfeil BE, McCouch S. Caught red-handed: Rc encodes a basic helix–loop–helix protein conditioning red pericarp in rice. Plant Cell. 2006;18:283–294. doi: 10.1105/tpc.105.038430. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tajima F. Statistical method for testing the neutral mutation hypothesis by DNA polymorphism. Genetics. 1989;123:585–595. doi: 10.1093/genetics/123.3.585. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thipyapong P, Hunt MD, Steffens JC. Systemic wound induction of potato (Solanum tuberosum) polyphenol oxidase. Phytochemistry. 1995;40:673–676. [Google Scholar]

- Vaughan LK, Ottis BV, Prazak-Havey AM, Bormans CA, Sneller C, Chandler JM, Park WD. Is all red rice found in commercial rice really Oryza sativa? Weed Science. 2001;49:468–476. [Google Scholar]

- Warwick SI, Legere A, Simard MJ, James T. Do escaped transgenes persist in nature? The case of an herbicide resistance transgene in a weedy Brassica rapa population. Molecular Ecology. 2008;17:1387–1395. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-294X.2007.03567.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whitton J, Wolf DE, Arias DM, Snow AA, Rieseberg LH. The persistence of cultivar alleles in wild populations of sunflowers five generations after hybridization. Theoretical and Applied Genetics. 1997;95:33–40. [Google Scholar]

- Yu Y, Tang T, Qian Q, Wang Y, Yan M, Zeng D, Han B, Wu CI, Shi S, Li J. Independent losses of function in a polyphenol oxidase in rice: differentiation in grain discoloration between subspecies and the role of positive selection under domestication. Plant Cell. 2008;20:2946–2959. doi: 10.1105/tpc.108.060426. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Methods S1 Details of protocols for DNA extraction, PCR cycling conditions and amplicon purification.

Table S1 Accession numbers, hull colors or cultivar names, species names, variety groups, phenol reaction responses, origins and probable hybrid status (based on morphology) or release dates for accessions used in this study

Table S2 Primer sequences used to amplify and sequence the Phr1 locus