Most peptic ulceration is due to chronic infection with Helicobacter pylori, and antibiotic treatments can generally cure both the infection and the ulceration.1 In previous decades, however, persistent peptic ulceration was often treated surgically either by vagotomy, which merely reduces symptoms, or by partial gastrectomy, which removes the ulcer and parts of the stomach likely to be infected with H pylori.2 There have been several surveys on the prevalence of persistent H pylori infection in patients who have undergone surgery for peptic ulceration, often many years previously. We present a systematic review of these surveys and compare the type of surgery with the likelihood of persistent H pylori infection.

Methods and results

We checked in databases, reference lists, and gastroenterology journals for any studies published before January 1997 that assessed H pylori infection after surgery for peptic ulceration. Studies were included if they provided information on the indication for surgery and the type of surgery. We tabulated the type of surgery, the mean interval between surgery and testing for H pylori (average 10 years), the method of testing for H pylori (mostly histology), the site and number of gastric biopsies, and the prevalence of infection. Among the 33 reports identified we excluded five: one included unrepresentative patients (Hepato Gastroenterol 1994;41:542-5), and four did not provide separate results for patients with peptic ulceration (Helicobacter 1996;1:270; Z Gastroenterol 1993;31:115-9) or patients who had had partial gastrectomy (Surg Gynecol Obstet 1993;176:594-8; Mat Med Pol 1994;88:13-6). From 28 publications, 36 studies were included. Prevalences from different studies were combined by direct summation of their numerators and denominators. The results from the small studies—that is, those with fewer than 20 patients—were combined in the figure and when displaying the results from separate studies and calculating standard χ2 tests of heterogeneity.

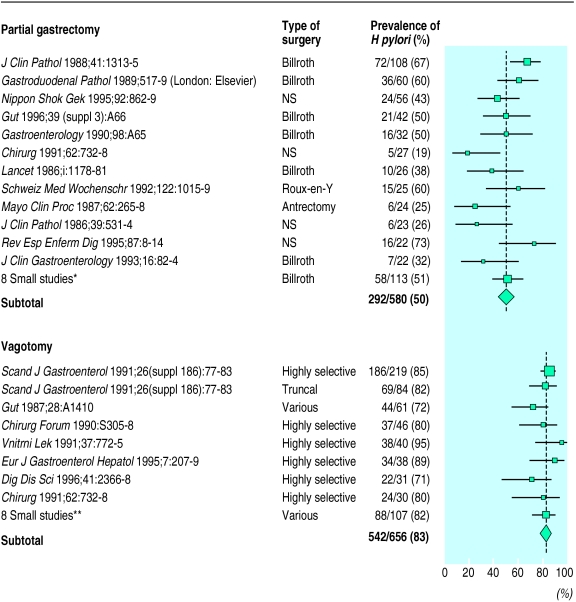

Among patients who had undergone vagotomy alone the prevalence of persistent H pylori infection was about 83% (542/656), whereas for partial gastrectomy it was only about 50% (292/580; figure). There were insufficient data to compare the prevalence of H pylori infection after particular types of partial gastrectomy—for example, Billroth v Roux-en-Y—or vagotomy—for example, highly selective v truncal. The heterogeneity within the two subtotals (χ212=47 and χ28=14) was much less extreme than the heterogeneity between the two subtotals (χ21=147, P<0.0001). Thus the difference in prevalence between the subtotals remained informative.

Comment

Other studies have shown that most patients with active peptic ulcers are infected with H pylori—about 95% of those with duodenal ulcer and 85% of those with gastric ulcer.3 The prevalence of H pylori in such patients remains high after vagotomy (83% (95% confidence interval 78% to 86%)) but falls to about 50% (45% to 56%) after partial gastrectomy. This difference cannot be explained by the methods used for testing for H pylori or for gastric tissue sampling as both were similar across studies, or by differences in reinfection rates postoperatively. Despite the inclusion of studies reported as abstracts or in languages other than English some publication bias may remain, although this should not alter the main conclusions. Remission of H pylori infection after partial gastrectomy may be due partly to the resection of distal gastric tissue, a usual site of infection, and partly to the bactericidal effects of prolonged bile acid reflux in surgical patients.4 Whatever the reason, this decrease represents one way surgery could contribute to the cure of peptic ulcer disease.

The main clinical implication of the persistently high prevalence of H pylori infection postoperatively is that patients who have undergone gastrectomy or particularly vagotomy should be reviewed and considered for antibiotic treatment that will cure their chronic infection.

Figure.

Prevalence of Helicobacter pylori after surgery for peptic ulcer: 36 studies. Size of black area proportional to number of patients. NS = not specified (*Dig Dis Sci 1991;36:1697; J Clin Gastroenterol 1993;16:82-4; Gastroenterology 1989;96:A247; Mat Med Pol 1994;88:9-12; Gastroenterology 1989;97:958-64; Ann Chir 1991;45:905-8; Gut 1989;30:1552-7; Pol Arch Med Wewn 1991;86:13-7. **Lancet 1986;1:1178-81; Gastroenterology 1989;97:958-64; Gastroduodenal pathology and Campylobacter pylori (London: Elsevier) 1989: 517-9, 525-7; Ann Chir 1991;45:905-8; Zentralbl Chir 1995;120:364-72; Gastroenterology 1990;98:A65; Mat Med Pol 1994;88:9-12)

Acknowledgments

Carsten Flohr, Sumiyo Iida, and Monika Jakubiecz helped with translations.

Footnotes

Funding: JD was supported by a Rhodes scholarship and a Balliol College senior scholarship.

Conflict of interest: None.

References

- 1.Goodwin CS, Mendall M, Northfield TC. Helicobacter pylori infection. Lancet. 1997;349:265–269. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(96)07023-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fineberg HV, Pearlman LA. Surgical treatment of peptic ulcer in the United States. Lancet. 1981;i:1305–1307. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(81)92471-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kuipers EJ, Thijs JC, Festen HPM. The prevalence of Helicobacter pylori in peptic ulcer disease. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 1995;9(suppl 2):59–69. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.O’Connor HJ, Wyatt JI, Ward DC, Dixon MF, Axon ATR, Dewar EP. Effect of duodenal ulcer surgery and enterogastric reflux on Campylobacter pyloridis. Lancet. 1986;i:1178–1181. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(86)92193-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]