Abstract

Objective: To determine whether short term, oral low dose prednisolone (⩽15 mg daily) is superior to placebo and non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs in patients with rheumatoid arthritis.

Design: Meta-analysis of randomised trials of oral corticosteroids compared with placebo or a non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug.

Setting: Trials conducted anywhere in the world.

Subjects: Patients with rheumatoid arthritis.

Main outcome measures: Joint tenderness, pain, and grip strength. Outcomes measured on different scales were combined by using the standardised effect size (difference in effect divided by SD of the measurements).

Results: Ten studies were included in the meta-analysis. Prednisolone had a marked effect over placebo on joint tenderness (standardised effect size 1.31; 95% confidence interval 0.78 to 1.83), pain (1.75; 0.87 to 2.64), and grip strength (0.41; 0.13 to 0.69). Measured in the original units the differences were 12 (6 to 18) tender joints and 22 mm Hg (5 mm Hg to 40 mm Hg) for grip strength. Prednisolone also had a greater effect than non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs on joint tenderness (0.63; 0.11 to 1.16) and pain (1.25; 0.26 to 2.24), whereas the difference in grip strength was not significant (0.31; −0.02 to 0.64). Measured in the original units the differences were 9 (5 to 12) tender joints and 12 mm Hg (−6 mm Hg to 31 mm Hg). The risk of adverse effects during moderate and long term use seemed acceptable.

Conclusion: Prednisolone in low doses (⩽15 mg daily) may be used intermittently in patients with rheumatoid arthritis, particularly if the disease cannot be controlled by other means.

Key messages

Prednisolone in low doses—that is, no more than 15 mg daily—is highly effective in patients with rheumatoid arthritis

The risk of adverse effects is acceptable in short, moderate, or long term use

Oral low dose prednisolone may be used intermittently in patients with rheumatoid arthritis, particularly if the disease cannot be controlled by other means

Further short term placebo controlled trials to study the clinical effect of prednisolone or other oral corticosteroids are no longer necessary

Introduction

Corticosteroids were first shown to be effective in patients with rheumatoid arthritis in 1949 in an uncontrolled study.1 In 1959, a two year randomised trial showed that an initial dose of prednisolone 20 mg daily was significantly superior to aspirin 6 g daily.2 Important adverse effects were also noted, however, and the authors concluded that the highest acceptable dose for long term treatment was probably in the region of 10 mg daily.

Corticosteroids have received renewed interest in recent years because of their possible beneficial effect on radiological progression.3 Tendencies towards such an effect were noted both in the early trials and in a recent report.4

These findings are interesting, but oral corticosteroids are still being used mainly for their symptomatic effect—for example, for acute exacerbations of rheumatoid arthritis and as “bridge therapy” before slow acting drugs have taken effect.5 The effect of low doses has been variable, however, and was questioned as late as 1995 when the most recent trial of low dose steroids was published.6 We therefore performed a systematic review of randomised trials that compared corticosteroids, given at a dose equivalent to no more than 15 mg prednisolone daily, with placebo or with non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs. Our review is limited to the short term effect—that is, as recorded within the first weeks of treatment. In an analysis of the adverse effects of steroids, however, we also included long term trials and matched cohort studies.

Methods

All randomised studies that compared an oral corticosteroid with placebo or a non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug in patients with rheumatoid arthritis were eligible if they reported clinical outcomes within 1 month after the start of treatment. When there were data from several visits, the data that came closest to 1 week of treatment were used for the analyses. We excluded studies with high dose steroids (exceeding an equivalent of 15 mg prednisolone daily); studies of combination treatments—for instance, of a steroid and a non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug; and studies that used quasi-randomisation methods, such as allocation by date of admission or by toss of a coin (no such studies were actually found). The outcome variables were joint tenderness (usually Ritchie’s joint index), pain, and grip strength.

Medline was searched from 1966 onwards and most recently updated in September 1997. We used the Explode option (which searches for a broad term plus related narrower items) for “glucocorticoids” or “glucocorticoids, -synthetic” (for all subheadings) combined with Explode “arthritis-rheumatoid” (for all subheadings) and with “placebos” or “comparative study” in MeSH. The reference lists were scanned for additional trials, and an archive in possession of one of the authors was searched. As most of the retrieved trials were very old and the steroid drugs were non-proprietary ones authors and companies were not asked about possible unpublished studies. We did not handsearch journals for relevant trials as this work is already being organised by the Cochrane Collaboration for all medical journals, including specialist rheumatological journals. The results of these handsearches are made available in the Cochrane Controlled Trials Register in The Cochrane Library,7 which we searched with prednisolone and prednisone as text words combined with rheumatoid.

Decisions on which trials to include were taken independently by two observers based only on the methods sections of the trials; disagreements were resolved by discussion. Details on the nature and dose of treatments, number of randomised patients, the randomisation and blinding procedures, and exclusions after randomisation were noted. When an outcome was measured on the same scale in all trials we calculated the weighted mean difference as the summary estimate for the effect. As the outcomes were often measured on different scales, however, even when they referred to the same quality—for example, tender joints—we also calculated standardised effect measures.8 With this method the difference in effect between two treatments is divided by the standard deviation of the measurements. By that transformation the effect measures become dimensionless, and outcomes from trials which have used different scales may therefore often be combined. As an example, the tender joint count may be recorded either as the number of tender joints or as Ritchie’s index, in which each joint is scored on a scale from 0 to 3 for pain on firm palpation and the scores added. Often the two types of counts will give similar values, but if the patients have very severe disease Ritchie’s index may be higher. The standard deviation will then also be higher, however, and by dividing the counts with their standard deviations (for example, of the baseline measurements) the effect sizes will be of the same magnitude.

The random effects model9 was used if P<0.10 for the test of heterogeneity; otherwise a fixed effects analysis was performed. As data from crossover trials were reported in only summary form, as if they had been generated from a group comparative trial, we analysed them accordingly. We therefore assumed that no important carryover effects had occurred.

Results

Twenty eight randomised trials were initially identified, several of which had been published more than once. Eighteen trials were excluded for various reasons.2,4,5,10–31 Nine trials did not fulfil the inclusion criteria for the meta-analysis: five had studied combinations of drugs10,17–19,27,31; two used too high a dose2,20–23; in one, 4 mg methylprednisolone was given to all the patients in the placebo group28; and one concerned patients with juvenile rheumatoid arthritis (this trial found prednisolone to be significantly better than placebo).24

The other nine excluded studies were potentially eligible for the meta-analysis. However, one was a five way crossover trial with a grossly unbalanced design—for instance, placebo was given to 9, 13, 3, 6, and 6 patients during weeks 1, 2, 3, 4, and 5, respectively.12 Because of regression towards the mean we found it inappropriate to include this trial. Another trial was also unbalanced as the steroid group was kept mobile whereas the control group received bed rest and splints for the inflamed joints.25 Two trials were too poorly reported to be usable for the meta-analysis,15,16,26 and one reported only on joint size.29 Three of these four trials found prednisolone or prednisone to be significantly more effective than placebo; the fourth compared prednisolone and indomethacin and gave no numerical data but just reported that there was “no significant difference in response.”26 The four other excluded trials were long term studies that did not report short term data.4,5,11,13,14 We contacted the authors of these studies to make sure that no short term data had been recorded without being reported. This was confirmed in two cases4,11; we were unable to contact any of the authors of the other two studies or of the study that reported only joint size29 to ensure that no further variables had been recorded.

Ten studies were included in the meta-analysis (table 1).6,32–43 Most of the studies were quite old and rather small. In all but one35,36 the criteria of the American Rheumatism Association for classical or definite rheumatoid arthritis were fulfilled. Age, proportion of women, and duration of disease were reported in only half of the studies but they were typical for studies in rheumatoid arthritis: mean age was 55 years, two thirds were women, and the mean (range) duration of disease was 6 (2.1 to 9.6) years. As expected for patients enrolled in steroid trials the severity of the disease, expressed as number of tender joints or Ritchie’s tender joint index, was quite pronounced (see fig 1). Prednisolone was used in six trials and prednisone in four.6,32,34,40,41,43 As prednisone is equipotent with prednisolone and is a pro-drug of prednisolone we have used “prednisolone” as a general term throughout the paper. The doses were 2.5, 3.0, and 7.5 mg in one study each, 10 mg in three studies, and 15 mg in four. The median length of treatment was 1 week.

Table 1.

General characteristics of studies included in meta-analysis of low dose prednisolone in treatment of rheumatoid arthritis

| Study | Design | Study drugs

|

Length of treatment (days) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Prednisolone | Control | |||

| Berry 197433 | Crossover | 15 mg | Placebo | 7 |

| Boardman 196734* | Crossover | 7.5 mg | Placebo | 7 |

| Böhm 19673536 | Crossover | 2.5 mg | Placebo | 8 |

| Dick 197037 | Crossover | 10 mg | Placebo; ibuprofen 1200 mg; aspirin 4 g† | 7 |

| Gestel 1995632 | Parallel | 10 mg | Placebo | 7‡ |

| Jasani 196838 | Crossover | 15 mg | Placebo; ibuprofen 750 mg; aspirin 5 g† | 7 |

| Lee 197339 | Crossover | 15 mg | Placebo; aspirin 5 g | 7 |

| Lee 19734041 | Parallel | 15 mg | Placebo; aspirin 3.9 g | 14 |

| Lee 197442 | Crossover | 10 mg | Placebo; sodium salicylate 4 g | 7 |

| Stenberg 199243 | Crossover | 3 mg | Placebo | 5§ |

We included two patients in analysis (excluded by authors because of too little difference in joint size) by assuming that difference in grip strength was 0.

Average of ibuprofen and aspirin used in analysis.

One week data provided by authors.

Each flare treated for 5 days; three randomised patients who were excluded because of poor response to prednisolone in introductory test period included in analysis by assuming that difference between prednisolone and placebo was 0.

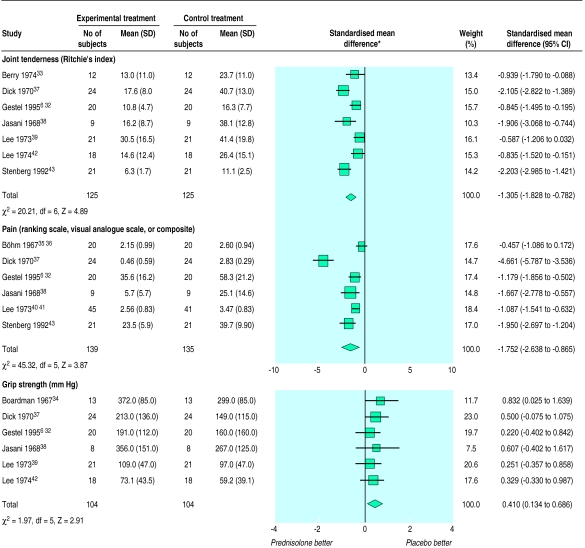

Figure 1.

Results of meta-analysis of low dose prednisolone versus placebo for control of rheumatoid arthritis, according to joint tenderness, pain, and grip strength. *If prednisolone is better than control standardised mean difference is negative for joint tenderness and pain but positive for grip strength. Random effects model was used for joint tenderness and pain, and fixed effects model for grip strength

The randomisation method was not described in any of the trial reports but details were obtained from the authors for one of the studies in which the treatment allocation seemed to have been adequately concealed.6,32 These authors also provided short term data from their long term trial. All studies were double blind apart from a single blind study in which the patients seemed to have been blinded.40,41 Eight of the studies were of a crossover design but only one of them reported having tested for sequence effects.43 Apart from one study43 the tender joint count was recorded as Ritchie’s index; pain was recorded on a ranking scale with 4 or 5 classes in two studies,35,36,40,41 on a visual analogue scale in two studies,6,32,33 and as a composite pain index in two studies.38,43

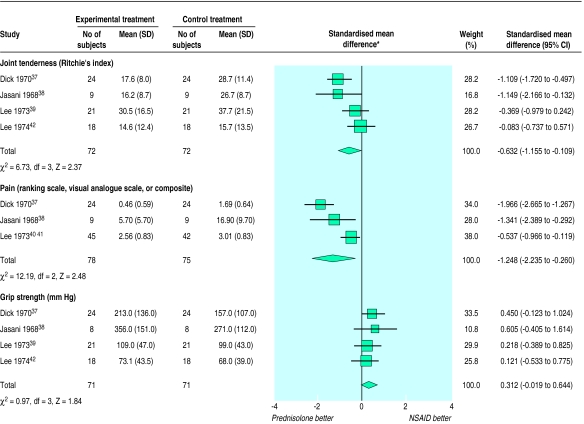

The results of the meta-analysis are shown in figures 1 and 2. It should be noted that if prednisolone is better than control, the standardised effect size is negative for joint tenderness and pain but positive for grip strength.

Figure 2.

Results of meta-analysis of low dose prednisolone versus non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) for control of rheumatoid arthritis, according to joint tenderness, pain, and grip strength. *If prednisolone is better than control standardised mean difference is negative for joint tenderness and pain but positive for grip strength. Random effects model was used for joint tenderness and pain, and fixed effects model for grip strength

Prednisolone had a clear effect over placebo on joint tenderness (standardised effect size −1.31; 95% confidence interval −1.83 to −0.78), pain (−1.75; −2.64 to −0.87), and grip strength (0.41; 0.13 to 0.69). Measured in the original units, in an analysis of the weighted mean difference the difference between prednisolone and placebo was 12 tender joints (95% confidence interval 6 to 18; test for heterogeneity χ2 46.42, df=6; P<0.00001). The effect on grip was always measured in mm Hg or in kPa. After conversion of kPa to mm Hg the superiority of prednisolone over placebo was 22 mm Hg (95% confidence interval 5 mm Hg to 40 mm Hg; test for heterogeneity χ2 5.47, df=5; P=0.36).

Prednisolone also had a greater effect than non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs on joint tenderness (−0.63; −1.16 to −0.11), pain (−1.25; −2.24 to −0.26), and grip strength, although the difference in grip strength was not significant (0.31; −0.02 to 0.64). Measured in the original units the difference between prednisolone and non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs was 9 tender joints (5 to 12; test for heterogeneity χ2 4.06, df=3; P=0.26). The effect on grip strength showed a non-significant superiority of prednisolone over non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs of 12 mm Hg (−6 mm Hg to 31 mm Hg; test for heterogeneity χ2 3.03, df=3; P=0.39).

Discussion

Our meta-analysis has shown that low dose prednisolone is not only highly effective but also significantly more effective than non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs. The point estimate for the difference in effect between prednisolone and non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs on grip strength was 12 mm Hg. It is interesting that the point estimate for the difference in effect between non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs and placebo was also found to be 12 mm Hg in an earlier meta-analysis.44 It was not surprising that the difference in effect on grip strength between prednisolone and non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs was not significant as this effect measure is considerably less sensitive to change than pain and joint tenderness.45

We used a random effects model for some of the analyses because of heterogeneity. Which model to use is a matter of dispute among statisticians, but the results were not too different if analysed with a fixed effects model, which gave standardised effect sizes for prednisolone versus placebo of −1.23 (−1.51 to −0.95) for joint tenderness and −1.35 (−1.63 to −1.08) for pain, and for prednisolone versus non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs of −0.61 (−0.95 to −0.27) for joint tenderness and −0.97 (−1.32 to −0.63) for pain.

Heterogeneity

It is always important to try to explain heterogeneity. Our attempts to do so, however, have been rather unsuccessful. As most of the studies were done more than 20 years ago an obvious reason for the heterogeneity could be that the earlier trials had overestimated the effect—for instance, because of insufficiently concealed randomisation methods.46 The methodological quality of the trials was acceptable in the whole time span of nearly 30 years, however, and it was, for example, similar to the quality of comparative non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug trials.47 In accordance with this there were no time trends for the differences in joint tenderness and pain between prednisolone and placebo. There was marginal heterogeneity (P=0.08) for the difference between prednisolone and non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs in joint tenderness, but the heterogeneity disappeared when the analysis was performed in the original units (P=0.26).

Blinding did not seem to have been important for heterogeneity. Only one trial was not double blind, and this trial did not yield larger effect estimates than the other trials. Small trials may exaggerate the effect because of publication bias.48,49 This possibility could not be studied as the trials were all rather small and contributed similar weights to the meta-analysis. The effect was so pronounced, however, that it would have been unreasonable to plan large trials; in this respect steroid trials resemble trials of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs that have also shown convincingly their superiority over placebo in small crossover trials.45 One would need to postulate that an unrealistically large number of unpublished trials existed that had shown no effect before the positive effect shown in our meta-analysis would become nullified.

An obvious cause for the heterogeneity could be varying degrees of concomitant treatment with additional non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs. Although sometimes stated in trial protocols, it may be difficult to ensure in practice that patients do not take additional drugs. As there was very sparse information on drug intake in the reports this possibility could not be evaluated. Another source could be the use of different measurement scales. Pain, for example, was measured on three different types of scale. They were all ranking scales, and we would therefore definitely have preferred to analyse pain with rank sum tests or as binary data after reduction of the level of measurement. The problem in analysing rank data with parametric methods is not only that they are often far from being normally distributed but also that we do not know the “distances” between the levels on the scale. As the original authors had used parametric statistics we decided to do so as well because our only other option was to discard the data.

Surprisingly, there was no clear relation between dose and effect despite the fact that the doses varied from 2.5 mg to 15 mg daily. It was not the aim of our review, however, to study dose-response relations, which are elucidated more reliably in studies where patients are randomised to different doses. A remarkable effect was seen in a study in which the average dose was only 3 mg daily but where the patients were allowed to start on 7.5 mg when they experienced flares of the arthritis and were advised to take nothing when they were well.43 This study suggests that it could be an advantage to take steroids intermittently, which would also diminish their adverse effects.

We could be criticised for including crossover trials for which we assumed but could not test that no important carryover effects had occurred. Our arguments for doing this were threefold. Firstly, it is not uncommon in statistical analyses to make necessary assumptions which cannot be properly tested in the data at hand—for example, in multiple regression analyses. Secondly, the problem with crossover trials is not only of a statistical nature, it also has an important ethical dimension. As crossover trials almost without exception are poorly reported and do not allow checks of the assumptions for this design,47 we would have to discard a vast amount of useful information in the literature in practically all areas of health care if we chose to behave as statistical purists. This would lead to much superfluous research being done, which is not in the best interest of patients or society. Thirdly, and most importantly, one would not expect carryover problems for drugs with relatively quick and reversible symptomatic effects such as steroids or non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. In fact in a meta-analysis of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs very similar results were obtained with the two trial designs.44 For these reasons we believe our approach is justified. Only two studies were of a group comparative design, and the heterogeneity we found could not be explained by type of design.

Included trials

The titles of the included trials were generally quite uninformative and some of the them were not easy to find as they were performed within experiments designed to study other factors. Several of the studies were retrieved from an archive in possession of one of the authors assembled during work on a thesis50 before the electronic data searches were performed. The authors of the most recent study in this topic6,32 had found only one of five trials comparing steroids with placebo in long term studies and none of the nine short term trials included in our review. These short term trials were described in 11 reports that were all indexed in Medline with the term for rheumatoid arthritis; in addition, all but one38 contained the terms for clinical trial or comparative study. Further, all nine trials were identifiable by using the search term “placebo*” and (“prednisone” or “prednisolone”). This illustrates the value of a systematic and careful search of the literature before starting new clinical trials, and funding bodies and ethical review committees should demand a systematic review of the relevant literature before approving of new clinical research.51

Recently, another meta-analysis of low dose corticosteroids (⩽15 mg prednisolone daily) in rheumatoid arthritis was published.52 This meta-analysis looked at moderate term effectiveness and focused on the outcome after 6 months; only two of the included trials were the same as in our meta-analysis.6,32,43 These authors also noted heterogeneity, but they did not explore possible reasons for it or show the individual results for each trial; they only showed the combined result for each outcome. The weighted mean difference between steroid and placebo was surprisingly small, corresponding to only 2.4 tender joints (four trials, 95% confidence interval 0.3 to 4.6), while the standardised effect size of 0.90 (−0.18 to 2.00), although not significant, was more comparable to the one we found.

Adverse effects

It is not easy to get a clear picture of the adverse effects of low dose steroids. Five of our short term studies did not report on side effects; one study reported that no side effects occurred38; two patients on prednisone had “subjective reactions” in one study34; and one patient developed acute psychosis while on prednisone in one study.40,41 The two remaining studies were moderate term studies from which we extracted short term efficacy data.6,32,43 These studies did not report short term side effects but are included in the analysis of moderate or long term adverse effects below.

The meta-analysis of moderate term low dose steroid trials did not examine adverse effects at all.52 The information in the most recently conducted two year placebo controlled trial is also sparse4; the aim of this study was to assess the progression of radiological damage, but films were taken only of the hands not of the lumbar spine, which could have detected any compression fractures. We reviewed moderate and long term randomised trials that had compared low dose steroids with placebo or a non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug. We also identified cohort studies of rheumatoid arthritis that had compared patients treated with steroids with a matched, untreated control group. For this purpose we limited our broad search strategy to Explode “glucocorticoids, -synthetic” (adverse-effects) or Explode “glucocorticoids” (adverse-effects), combined with Explode “arthritis, -rheumatoid” (for all subheadings).

We found eight trials and two matched cohort studies (table 2). Spinal x ray photographs were taken of all patients in three of the trials; four fractures were detected in a total of 83 patients randomised to prednisolone and one in 75 patients randomised to placebo. In the five remaining trials, comprising a total of 193 patients taking prednisolone and 190 taking placebo or aspirin, only one fracture with prednisolone and one with placebo were reported. No cases of cataract were reported in the trials. One of the trials was highly atypical as the starting dose was 300 mg cortisone, equivalent to 60 mg prednisolone.20–22 Its high number of adverse effects may therefore not be representative.

Table 2.

Details of eight trials and two matched cohort studies used in meta-analysis of low dose prednisolone in treatment of rheumatoid arthritis

| Study | Equivalent dose of prednisolone | Length of treatment | No of patients taking steroids/ control | Reported major adverse effects (defined by authors) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Randomised trials v placebo | ||||

| Chamberlain 197611 | 3 or 5 mg | 2 years | 30/19 | Vertebral fracture in 1 v 1; no proved peptic ulcers |

| Harris 19835 | 5 mg | 6 months | 18/16 | Two fractures on steroid, no ocular changes; all patients subjected to lumbar spine films and ophthalmic examination |

| Stenberg 199243 | 3 mg | 3 months | 22/22 | None (only mild adverse effects, similar to placebo group) |

| Gestel 1995632 | 10 mg | 3 months | 20/20 | No fractures; all patients had lateral spine radiographs taken |

| Kirwan 19954 | 7.5 mg | 2 years | 61/67 | None (two cases of hypertension/weight gain on steroid, two with diabetes and hypertension, respectively, on placebo) |

| Randomised trials v aspirin | ||||

| Empire Rheumatism Council 195513 | 15 mg | 1 year* | 50/50 | Hypertension in 2 v 0 and indigestion in 1 v 5 caused drop out |

| Joint Committee 19542021 | 16 mg† | 2 years* | 30/32 | None (moon face or rubicundity in 11, depression in 5, euphoria in 4 v tinnitus in 11, deafness in 10, nausea, dyspepsia or anorexia in 13 reported in first year. Similar adverse effects in second year (one drop out on each drug, no fractures or cataract)) |

| Joint Committee 19592 | 10 mg‡ | 2 years* | 45/39 | Fractures in 2 v 1, psychosis in 2 v 0, ulcers in 3 v 0, infections in 4 v 3. All had spinal x rays. Several other complications described, most probably unrelated to trial drugs |

| Matched cohorts | ||||

| Saag 199453 | ⩽15 mg | >12 months | 112/112 | Survival type analysis; adverse events more common with steroid, see text |

| McDougall 199454 | 8 mg | 10 years | 122/122 | Fractures in 31 v 19, cataracts in 36 v 22, osteonecrosis in 5 v 2 |

Three year results not analysed because of too many drop outs,14 treatment not randomised,22 or too low adherence to randomised treatment.23

Average dose, all started with equivalent of 60 mg prednisolone.

Average dose, all started with 20 mg.

One of the cohort studies used a survival-type analysis and found a large difference in time to first adverse event, with a total of 92 events in the steroid group and 31 in the untreated group.53 The risk of fracture increased with increasing doses: odds ratio 32.3 (95% confidence interval 4.6 to 220) for >10-15 mg prednisolone daily, 4.5 (2.1 to 9.6) for 5-10 mg, and 1.9 (0.8 to 4.7) for less than 5 mg daily. The overall risks for first event were 3.9 (0.8 to 18.1) for fracture, 8.0 (1.0 to 64.0) for infection, and 3.3 (0.9 to 12.1) for gastrointestinal bleed or ulcer. This study also included patients who received oral steroid “pulses,” which do not necessarily lead to the same incidence and severity of adverse effects as continuous low dose treatment. The other cohort study followed two groups of 122 patients for 10 years54. Fractures were noted in 31 versus 19 patients, osteonecrosis in 5 versus 2, and cataracts in 36 versus 22 (table 2).

The main problem with studies of matched cohorts is of course that the two groups can never be completely comparable as patients treated with steroids must be expected to be more severely affected than those not treated. This fact may escape notice by traditional measures of morbidity or the difference may be significant for one54 or more53 indicators of severity of disease, as in the two cohort studies we reviewed. It is noteworthy, for example, that the first study found a similarly increased risk for fractures as for ulcers,53 though five meta-analyses of around 100 randomised trials of steroids in various diseases have shown either no increase in risk or, at most, a marginally increased risk of ulcers, which lacks clinical significance.55 Another meta-analysis of 71 randomised trials, which looked at the risk of infectious complications, showed no increase in risk in patients given less than 10 mg prednisolone daily, and the relative risk for a mean dose under 20 mg was only 1.3 (1.0 to 1.6), which contrasts with the eightfold increased risk in the cohort study.56 Although the confidence intervals were wide in the cohort study, this illustrates the well known dangers of non-randomised comparisons.

Other treatments for rheumatoid arthritis—that is, non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs and slow acting antirheumatic drugs—have important adverse effects, which may occasionally even be life threatening. We therefore suggest that short term prednisolone in low doses—that is, not exceeding 15 mg daily—may be used intermittently in patients with rheumatoid arthritis, particularly if they have flares in their disease that cannot be controlled by other means. This suggestion is in accordance with a recent detailed review of the adverse effects of low dose steroids.57 As prednisolone is highly effective, short term placebo controlled trials to study the clinical effect of low dose prednisolone or other oral corticosteroids are no longer necessary. If additional relevant trials are performed in future—for example, comparison of steroids with non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs—they will be included in the electronic version of this meta-analysis,58 which will be continuously updated.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful for the unpublished data provided by Anke van Gestel and Roland Laan.

Editorial by Dennison and Cooper

Footnotes

Funding: Danish Medical Research Council.

Conflict of interest: None.

References

- 1.Hench PS, Kendall EC, Slocumb CH, Polley HF. The effect of a hormone of the adrenal cortex (17-hydroxy-11-dehydrocorticosterone: compound E) and of pituitary adrenocorticotropic hormone on rheumatoid arthritis. Proc Staff Meet Mayo Clin. 1949;24:181–197. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Joint Committee of the Medical Research Council and Nuffield Foundation. A comparison of prednisolone with aspirin or other analgesics in the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis. Ann Rheum Dis. 1959;18:173–188. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Weiss MM. Corticosteroids in rheumatoid arthritis. Sem Arthritis Rheum. 1989;19:9–21. doi: 10.1016/0049-0172(89)90083-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kirwan JR the Arthritis and Rheumatism Council Low-dose Glucocorticoid Study Group. The effect of glucocorticoids on joint destruction in rheumatoid arthritis. N Engl J Med. 1995;333:142–146. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199507203330302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Harris ED, Emkey RD, Nicols JE, Newberg A. Low dose prednisone therapy in rheumatoid arthritis: a double blind study. J Rheumatol. 1983;10:713–721. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gestel AM van, Laan RFJM, Haagsma CJ, Putte LBA van de, Riel PLCM van. Oral steroids as bridge therapy in rheumatoid arthritis patients starting with parenteral gold. A randomized double-blind placebo-controlled trial. Br J Rheumatol 1995;34:347-51. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 7.The Cochrane Library [database on disk and CD ROM]. Cochrane Collaboration. Oxford: Update Software; 1996-. Updated quarterly.

- 8.Mulrow CD, Oxman AD. Cochrane Collaboration Handbook, 3rd ed (updated 9 December 1996). Available in The Cochrane Library [database on disk and CD ROM]. Cochrane Collaboration; Issue 4. Oxford: Update Software; 1997. Updated quarterly.

- 9.DerSimonian R, Laird N. Meta-analysis in clinical trials. Controlled Clin Trials 1986;7:177-88. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 10.Badia Flores J. Valoracion del GP-40705 en la artritis reumatoide. Prensa Med Mex. 1969;34:382–384. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chamberlain MA, Keenan J. The effect of low doses of prednisolone compared with placebo on function and on the hypothalamic pituitary adrenal axis in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Rheumatol Rehabil. 1976;15:17–23. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/15.1.17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Deodhar SD, Dick WC, Hodgkinson R, Buchanan WW. Measurement of clinical response to anti-inflammatory drug therapy in rheumatoid arthritis. Q J Med. 1973;166:387–401. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Empire Rheumatism Council. Multi-centre controlled trial comparing cortisone acetate and acetyl salicylic acid in the long-term treatment of rheumatoid arthritis. Ann Rheum Dis. 1955;14:353–363. doi: 10.1136/ard.14.4.353. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Empire Rheumatism Council. Multi-centre controlled trial comparing cortisone acetate and acetyl salicylic acid in the long-term treatment of rheumatoid arthritis. Ann Rheum Dis. 1957;16:277–289. doi: 10.1136/ard.16.3.277. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fearnley ME, Masheter HC. A controlled trial of flufenamic acid therapy in rheumatoid arthritis. Ann Phys Med. 1966;8:204–207. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/8.6.204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fearnley ME. An investigation of possible synergism between flufenamic acid and prednisone. Ann Phys Med 1966;suppl:109-10. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 17.Gum OB. A controlled study of two preparations, paramethasone, propoxyphene, and aspirin and propoxyphene and aspirin in the treatment of arthritis. Am J Med Sci. 1966;251:328–332. doi: 10.1097/00000441-196603000-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jick H, Pinals RS, Ullian R, Slone D, Muench H. Dexamethasone and dexamethasone-aspirin in the treatment of chronic rheumatoid arthritis. Lancet. 1965;ii:1203–1205. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(65)90632-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jick H, Slone D, Dinan B, Muench H. Evaluation of drug efficacy by a preference technic. N Engl J Med. 1966;275:1399–1403. doi: 10.1056/NEJM196612222752502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Joint Committee of the Medical Research Council and Nuffield Foundation. A comparison of cortisone and aspirin in the treatment of early cases of rheumatoid arthritis. BMJ. 1954;i:1223–1227. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Joint Committee of the Medical Research Council and Nuffield Foundation. A comparison of cortisone and aspirin in the treatment of early cases of rheumatoid arthritis. BMJ. 1955;ii:695–700. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Joint Committee of the Medical Research Council and Nuffield Foundation. Long-term results in early cases of rheumatoid arthritis treated with either cortisone or aspirin. BMJ. 1957;i:847–850. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Joint Committee of the Medical Research Council and Nuffield Foundation. Comparison of prednisolone with aspirin or other analgesics in the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis. Ann Rheum Dis. 1960;19:331–337. doi: 10.1136/ard.19.4.331. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kvien TK, Hoyeraal HM, Sandstad B. Assessment methods of disease activity in juvenile rheumatoid arthritis—evaluated in a prednisolone/placebo double-blind study. J Rheumatol. 1982;9:696–702. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Million R, Kellgren JH, Poole P, Jayson MIV. Long-term study of management of rheumatoid arthritis. Lancet. 1984;i:812–816. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(84)92270-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Murthy MHV, Rhymer AR, Wright V. Indomethacin or prednisolone at night in rheumatoid arthritis? Rheumatol Rehab. 1978;17:8–13. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/17.1.8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Siegmeth W, Herkner W. Erfahrungen mit einem neuen Kombinationspräparat (Realin) bei der Behandlung akuter rheumatischer Zustandsbilder. Wien Med Wochenschr. 1974;124:569–573. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Slonim RR, Kiem IM, Howell DS, Brown HE. Evaluation of drug responses in the patient severely afflicted with rheumatoid arthritis. J Florida Med Assoc. 1969;56:336–341. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Webb J, Downie WW, Dick WC, Lee P. Evaluation of digital joint circumference measurements in rheumatoid arthritis. Scand J Rheumatol. 1973;2:127–131. doi: 10.3109/03009747309098831. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.West HF. Rheumatoid arthritis. The relevance of clinical knowledge to research activities. Abstracts World Med. 1967;41:401–417. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Zuckner J, Uddin J, Ramsey RH. Adrenal-pituitary relationships with prolonged low dosage steroid therapy in rheumatoid arthritis. Missouri Med. 1969;66:649–658. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Laan RFJM, Riel PLCM van, Putte LBA van de, Erning LJTO van, Hof MA van’t, Lemmens JAM. Low-dose prednisone induces rapid reversible axial bone loss in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Ann Intern Med 1993;119:963-8. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 33.Berry H, Huskisson EC. Isotopic indices as a measure of inflammation in rheumatoid arthritis. Ann Rheum Dis. 1974;33:523–525. doi: 10.1136/ard.33.6.523. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Boardman PL, Dudley Hart F. Clinical measurement of the anti-inflammatory effects of salicylates in rheumatoid arthritis. BMJ. 1967;iv:264–268. doi: 10.1136/bmj.4.5574.264. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Böhm C. Zur medikamentosen Langzeittherapie der primarchronischen Polyarthritis. Med Welt. 1967;35:2047–2050. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Schoger GA. Zur beurteilung der Wirkung einer Kombination von Salicylaten und Prednisolon bei rheumatischen Erkrankungen. Arzneimittel-Forschung. 1968;18:758–760. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Dick WC, Nuki G, Whaley K, Deodhar S, Buchanan WW. Some aspects in the quantitation of inflammation in joints of patients suffering from rheumatoid arthritis. Rheumatol Phys Med 1970;suppl 10:40-7. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 38.Jasani MK, Downie WW, Samuels BM, Buchanan WW. Ibuprofen in rheumatoid arthritis. Ann Rheum Dis. 1968;27:457–462. doi: 10.1136/ard.27.5.457. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lee P, Jasani MK, Dick WC, Buchanan WW. Evaluation of a functional index in rheumatoid arthritis. Scand J Rheumatol. 1973;2:71–77. doi: 10.3109/03009747309098820. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lee P, Webb J, Anderson J, Buchanan WW. Method for assessing therapeutic potential of anti-inflammatory antirheumatic drugs in rheumatoid arthritis. BMJ. 1973;ii:685–688. doi: 10.1136/bmj.2.5868.685. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Lee P, Anderson JA, Miller J, Webb J, Buchanan WW. Evaluation of analgesic action and efficacy of antirheumatic drugs. J Rheumatol. 1976;3:283–294. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Lee P, Baxter A, Carson Dick W, Webb J. An assessment of grip strength measurement in rheumatoid arthritis. Scand J Rheumatol. 1974;3:17–23. doi: 10.3109/03009747409165124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Stenberg VI, Fiechtner JJ, Rice JR, Miller DR, Johnson LK. Endocrine control of inflammation: rheumatoid arthritis. Double-blind, crossover clinical trial. Int J Clin Pharm Res. 1992;12:11–18. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Gøtzsche PC. Meta-analysis of grip strength: most common, but superfluous variable in comparative NSAID trials. Dan Med Bull. 1989;36:493–495. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Gøtzsche PC. Sensitivity of effect variables in rheumatoid arthritis: a meta-analysis of 130 placebo controlled NSAID trials. J Clin Epidemiol. 1990;43:1313–1318. doi: 10.1016/0895-4356(90)90097-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Schulz KF, Chalmers I, Hayes RJ, Altman D. Empirical evidence of bias: dimensions of methodological quality associated with estimates of treatment effects in controlled trials. JAMA. 1995;273:408–412. doi: 10.1001/jama.273.5.408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Gøtzsche PC. Methodology and overt and hidden bias in reports of 196 double-blind trials of nonsteroidal, antiinflammatory drugs in rheumatoid arthritis. Controlled Clin Trials. 1989;10:31–56. doi: 10.1016/0197-2456(89)90017-2. (erratum:356). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Dickersin K, Min Y-I. NIH clinical trials and publication bias. Online J Curr Clin Trials 1993 Apr 28;Doc No 50. [PubMed]

- 49.Stern JM, Simes RJ. Publication bias: evidence of delayed publication in a cohort study of clinical research projects. BMJ. 1997;315:640–645. doi: 10.1136/bmj.315.7109.640. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Gøtzsche PC. Bias in double-blind trials (thesis) Dan Med Bull. 1990;37:329–336. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Savulescu J, Chalmers I, Blunt J. Are research ethics committees behaving unethically? Some suggestions for improving performance and accountability. BMJ. 1996;313:1390–1393. doi: 10.1136/bmj.313.7069.1390. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Saag KG, Criswell LA, Sems KM, Nettleman MD, Kolluri S. Low-dose corticosteroids in rheumatoid arthritis. A meta-analysis of their moderate-term effectiveness. Arthritis Rheum. 1996;39:1818–1825. doi: 10.1002/art.1780391107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Saag KG, Koehnke R, Caldwell JR, Brasington R, Burmeister LF, Zimmerman B, et al. Low dose long-term corticosteroid therapy in rheumatoid arthritis: an analysis of serious adverse events. Am J Med. 1994;96:115–123. doi: 10.1016/0002-9343(94)90131-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.McDougall R, Sibley J, Haga M, Russell A. Outcome in patients with rheumatoid arthritis receiving prednisone compared to matched controls. J Rheumatol. 1994;21:1207–1213. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Gøtzsche PC. Steroids and peptic ulcer: an end to the controversy [editorial]? J Intern Med. 1994;236:599–601. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2796.1994.tb00853.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Stuck AE, Minder CE, Frey FJ. Risk of infectious complications in patients taking glucocorticosteroids. Rev Infect Dis. 1989;11:954–963. doi: 10.1093/clinids/11.6.954. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Caldwell JR, Furst DE. The efficacy and safety of low-dose corticosteroids for rheumatoid arthritis. Sem Arthritis Rheum. 1991;21:1–11. doi: 10.1016/0049-0172(91)90051-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Gøtzsche PC, Johansen HK. Short-term low-dose corticosteroids vs placebo and nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs in rheumatoid arthritis. In: Tugwell P, Brooks P, Wells G, de Bie R, Bosi-Ferraz M, Gillespie W, eds. Musculoskeletal module. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. The Cochrane Library. Cochrane Collaboration; Issue 4. Oxford: Update Software; 1997. Updated quarterly.